Abstract

Mucin 1 (MUC1) is a heterodimeric protein that is overexpressed in diverse human carcinomas. The oncogenic function of the MUC1 C-terminal subunit (MUC1-C) subunit is dependent on the formation of dimers through its cytoplasmic domain; however, it is not known whether MUC1-C can be targeted with small-molecule inhibitors. In the present work, an assay using the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain (MUC1-CD) was established to screen small-molecule libraries for compounds that block its dimerization. Using this approach, the flavone apigenin was identified as an inhibitor of MUC1-CD dimerization in vitro and in cells. By contrast, the structurally related flavone baicalein was ineffective in blocking the formation of MUC1-CD dimers. In concert with these results, apigenin, and not baicalein, blocked the localization of MUC1-C to the nucleus. MUC1-C activates MUC1 gene expression in an autoinductive loop, and apigenin, but not baicalein, treatment was associated with down-regulation of MUC1 mRNA levels and MUC1-C protein. The results also demonstrate that apigenin-induced suppression of MUC1-C expression is associated with apoptotic cell death and loss of clonogenic survival. These findings represent the first demonstration that the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain is a target for the development of small-molecule inhibitors.

Introduction

Mucin 1 (MUC1) is a heterodimeric protein that is aberrantly expressed by diverse human carcinomas and certain hematological malignancies (Kufe, 2009). The overexpression of MUC1, as found in human cancers, is associated with the induction of anchorage-independent growth and tumorigenicity (Li et al., 2003). Based on these findings, MUC1 has emerged as an attractive target for the development of anticancer agents. However, the identification of drugs that block MUC1 has been limited by the lack of sufficient information regarding how MUC1 contributes to the growth and survival of malignant cells. In this regard, the MUC1 protein is translated by a single mRNA and then undergoes autocleavage into two subunits that in turn form a heterodimer (Kufe, 2009). The MUC1 N-terminal subunit is the mucin component of the heterodimer that contains the characteristic glycosylated tandem repeats and is expressed on the cell surface in a complex with the MUC1 C-terminal transmembrane subunit (MUC1-C) (Kufe, 2009). Much of the early work on targeting MUC1 focused the MUC1 N-subunit, which is shed from the cell surface. However, subsequent studies have shown that MUC1-C is the oncogenic subunit of the heterodimer and a potential target for drug development (Kufe, 2009). In this context, MUC1-C associates with receptor tyrosine kinases, such as the epidermal growth factor receptor, at the cell membrane (Ramasamy et al., 2007). Moreover, the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain is subject to phosphorylation by receptor tyrosine kinases c-Src and c-Abl and interacts with effectors, such as β-catenin, that have been linked to transformation (Kufe, 2009). The demonstration that overexpression of the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain is sufficient to induce transformation provided support for the concept that targeting this region could block its oncogenic function (Huang et al., 2005).

The overexpression of MUC1 in carcinoma cells is associated with the accumulation of MUC1-C in the cytoplasm (Kufe et al., 1984; Perey et al., 1992; Croce et al., 2003). MUC1-C is also targeted to the nucleus by an importin β-dependent mechanism (Leng et al., 2007). Of importance to targeting the function of this subunit, the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain contains a CQC motif that is necessary for the formation of dimers and thereby the interaction with importin β (Leng et al., 2007). In the nucleus, MUC1-C associates with p53, TCF4/β-catenin, nuclear factor-κB p65, and signal transducers and activators of transcription on their target gene promoters and contributes to the regulation of gene expression, including induction of the MUC1 gene itself in autoinductive loops (Huang et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2005; Ahmad et al., 2009; Khodarev et al., 2010; Ahmad et al., 2011). In this way, MUC1-C activates specific gene families involved in oncogenesis, angiogenesis, and extracellular remodeling that predict significant decreases in the survival of patients with breast and lung cancer (Khodarev et al., 2009; Pitroda et al., 2009; MacDermed et al., 2010). Based on these results, cell-penetrating peptides were developed to block MUC1-C dimerization at the CQC motif and thereby its localization to the nucleus (Raina et al., 2009). Significantly, inhibition of MUC1-C with these peptides was associated with the death of human breast cancer cells growing in vitro and as tumor xenografts in nude mice (Raina et al., 2009). Human prostate cancer cells also responded to blocking MUC1-C dimerization with inhibition of growth and survival (Joshi et al., 2009). In addition, the specificity of this approach for blocking MUC1-C was supported by the absence of an effect of the inhibitor on prostate cancer cells that are null for MUC1 expression (Joshi et al., 2009). These findings suggested that small molecules might be identified that block MUC1-C dimerization and its oncogenic function.

The present work was performed to determine whether the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain is also a target for small-molecule inhibitors. Accordingly, an in vitro MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain (MUC1-CD) dimerization assay was developed to screen small-molecule libraries. Using this approach, apigenin, a plant flavone with preventative and therapeutic anticancer activity (Patel et al., 2007), was identified as an inhibitor of MUC1-CD dimerization in vitro. The results demonstrate that apigenin, but not the related flavone baicalein, 1) blocks the formation of MUC1-CD dimers in cells, 2) down-regulates MUC1 expression, consistent with the disruption of autoinduction of the MUC1 gene, and 3) induces MUC1-dependent cell death.

Materials and Methods

Small-Molecule Screening Assay.

Purified recombinant MUC1-CD dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was added to each well of a microtiter plate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). After an overnight incubation, 1% bovine serum albumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was added to each well for 1 h, and then the wells were washed with PBS. Small-molecule libraries were provided by the Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology (ICCB)-Longwood, Harvard Medical School Screening Facility (http://iccb.med.harvard.edu/screening compound_libraries/index.htm). Compounds were added to individual wells at a concentration of 100 μM. Purified MUC1-CD labeled with biotin using the EZ-Link Biotinylation kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was then added, followed by the sequential addition of streptavidin-HRP (Sigma-Aldrich) and 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) peroxidase substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Absorbency at 562 nm was measured by EnVision (PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Waltham, MA).

Cell Culture.

Human MCF-7 breast cancer cells and 293 cells were grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone Laboratories, Logan, UT), 4.5g/l glucose, l-glutamine, and sodium pyruvate. Human MCF-10A breast epithelial cells were grown in mammary epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza Baltimore, Baltimore, MD). Human HCC1937 and BT474 breast tumor cells were grown in RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum, glucose, glutamine, and sodium pyruvate. Cells were treated with apigenin and baicalein (both from Sigma-Aldrich) dissolved in 100% DMSO. Cell proliferation was assessed using a colorimetric assay with Cell Proliferation Assay kit (Promega, Madison, WI).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting.

Whole-cell and nuclear lysates were prepared as described previously (Leng et al., 2007). Lysates from 293 cells transfected to expressed GFP-MUC1-CD and Flag-MUC1-CD (Raina et al., 2009) were immunoprecipitated with anti-Flag (Sigma-Aldrich). Immunoblot analysis of the precipitates, cell lysates, and purified proteins was performed with anti-MUC1-C (Thermo Fisher Scientific), anti-GFP (Abcam Inc., Cambridge, MA), anti-Flag, anti-β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich), and anti-caspase-9 (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA). Immune complexes were detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and enhanced chemiluminescence (GE Healthcare, Chalfont St. Giles, Buckinghamshire, UK).

Assessment of Cell Membrane Integrity.

Cells were harvested, washed with PBS, incubated with 1 μg/ml propidium iodide/PBS for 5 min at room temperature, and then monitored by flow cytometry as described previously (Raina et al., 2009).

Quantitative Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction.

Total RNA was extracted with RNeasy (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA). cDNA was synthesized with the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative polymerase chain reactions were performed in TaqMan Universal PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using MUC1 primers (assay ID Hs00159357_m1; Applied Biosystems).

Colony Formation Assays.

Cells were plated at 1000 or 5000 cells/6-cm dish. After 2 weeks, the cells were fixed (3:1 methanol/acetic acid), rinsed, and stained with 0.4% crystal violet. Images were acquired using an Axioplan 2 imaging microscope equipped with a digital camera and processed with SPOT software (SPOT Imaging Solutions, Sterling Heights, MI).

Results

Screening for Compounds that Inhibit MUC1-CD Dimerization.

The 72-amino acid MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain (MUC1-CD) contains cysteine residues at positions 1 and 3 that are necessary for its dimerization (Fig. 1A) (Leng et al., 2007; Kufe, 2009). To develop an assay for identifying inhibitors of MUC1-CD dimerization, 96-well plates were first coated with purified MUC1-CD (Fig. 1B). Biotinylated MUC1-CD was then added to the wells, and its interaction with bound MUC1-CD was detected with streptavidin-HRP (Fig. 1B). Quantitation of the signals was determined with EnVision (Fig. 1B). Using this approach, six libraries containing more than 5000 compounds were screened for molecules that block the formation of MUC1-CD dimers (Fig. 1C). Initial screens were performed in the presence of compounds at a concentration of 100 μM. Compounds that inhibited dimerization by more than 50% were selected for further evaluation. Using these criteria, the percentage of positive compounds ranged from ∼1% to nearly 4% depending on the library (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Identification of MUC1-CD dimerization inhibitors in a small-molecule screen. A, schematic representation of the MUC1-C subunit with the 58-amino acid (aa) extracellular domain (ECD), the 28-aa transmembrane domain (TD), and the 72-aa cytoplasmic domain (CD). The sequence of MUC1-CD is included with highlighting of the CQC dimerization motif. B, the assay for identification of MUC1-CD dimerization inhibitors is depicted with the following steps: 1) coating of MUC1-CD onto a microplate, 2) adding soluble biotinylated MUC1-C and 100 μM compound, and 3) addition of streptavidin-HRP and then peroxide with conversion by HRP to a blue color. The signal as measured by EnVision is proportional to the amount of bound biotin-labeled MUC1-CD. C. The number of compounds ( ) screened from the indicated libraries is shown with the percentage of positive hits (■) as determined by more than 50% inhibition of MUC1-CD dimerization.

) screened from the indicated libraries is shown with the percentage of positive hits (■) as determined by more than 50% inhibition of MUC1-CD dimerization.

Identification of Apigenin as an Inhibitor of MUC1-CD Dimerization.

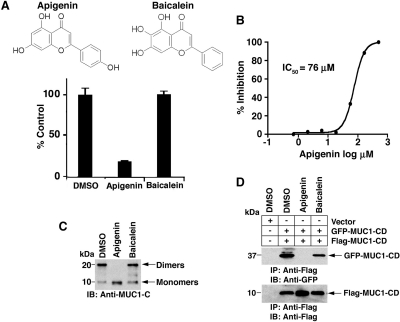

Based on the screening results, we identified the flavone apigenin (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) as one candidate inhibitor (Fig. 2A). Compared with vehicle (DMSO), 100 μM apigenin inhibited MUC1-CD dimerization by approximately 80% (Fig. 2A). By contrast, the structurally related flavone baicalein (5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone) had little, if any, effect (Fig. 2A). Analysis of apigenin over a range of concentrations further demonstrated 50% inhibition (IC50) of MUC1-CD dimerization at 76 μM (Fig. 2B). To extend these observations, studies of MUC1-CD dimerization were performed using soluble unbound protein. Previous work showed that the 10-kDa MUC1-CD monomer forms 20-kDa dimers in solution (Raina et al., 2009). As detected by immunoblot analysis, the formation of MUC1-CD dimers was completely blocked by apigenin, whereas baicalein had little effect (Fig. 2C). Transfection of cells with GFP-MUC1-CD and Flag-MUC1-CD has also been used to assess the formation of MUC1-CD dimers in coimmunoprecipitation assays (Raina et al., 2009). In this regard, immunoblot analysis of anti-Flag precipitates with anti-GFP readily detected MUC1-CD dimerization in the absence of treatment (Fig. 2D). Moreover, the formation of MUC1-CD dimers was completely blocked by apigenin, but not baicalein, treatment (Fig. 2D). These findings indicated that apigenin functions as an inhibitor of MUC1-CD dimerization in vitro and in cells.

Fig. 2.

Apigenin is an inhibitor of MUC1-CD dimerization in vitro and in cells. A, structures of apigenin and baicalein. Using the in vitro screening assay, dimerization of MUC1-CD was assessed in the presence of 100 μM apigenin or 100 μM baicalein each dissolved in 0.1% DMSO. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as a percentage of control dimerization in the presence of DMSO alone. B, MUC1-CD dimerization was assessed in the presence of the indicated concentrations of apigenin in the in vitro screening assay. The results are expressed as the percentage of inhibition with a calculated IC50 of 76 μM. C, soluble MUC1-CD was incubated in the presence of 1% DMSO, 1 mM apigenin, or 1 mM baicalein for 1 h at room temperature. Monomers and dimers were assessed by electrophoresis in a nonreducing gel and immunoblotting with anti-MUC1-C. D, 293 cells were transiently transfected to express an empty vector or GFP-MUC1-CD and Flag-MUC1-CD. At 6 h after transfection, the cells were left untreated and were treated with 75 μM apigenin or baicalein for 3 days. Whole-cell lysates were precipitated with anti-Flag, and the precipitates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies.

Effects of Apigenin on MUC1 Expression in MCF-10A Mammary Epithelial Cells.

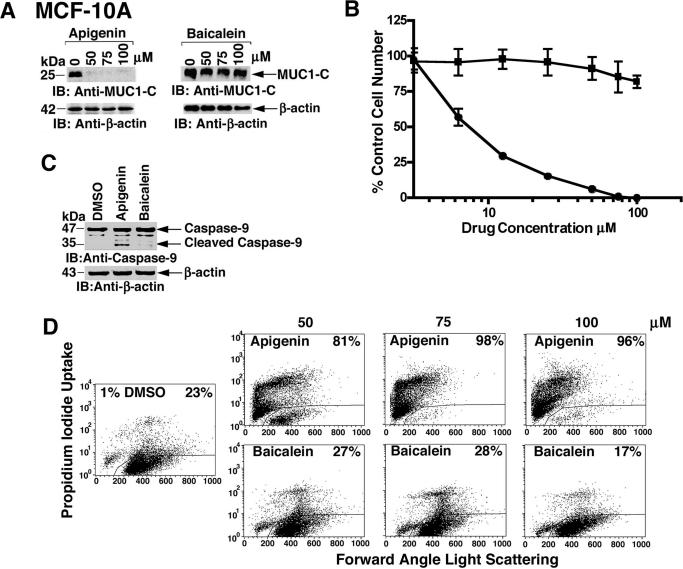

MUC1-C localizes to the nucleus by a mechanism dependent on its dimerization and thereby promotes the induction of the MUC1 gene in an autocatalytic loop (Leng et al., 2007; Ahmad et al., 2009). Accordingly, studies were performed to assess the effects of apigenin on localization of MUC1-C to the nucleus. Treatment of immortalized MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells with 50 to 100 μM apigenin was associated with the complete down-regulation of MUC1-C levels (Fig. 3A). By contrast, baicalein had no apparent effect on MUC1-C expression (Fig. 3A). Apigenin also decreased MCF-10A cell number, whereas baicalein was substantially less effective (Fig. 3B). MUC1-C protects against the induction of cell death (Yin and Kufe, 2003; Ren et al., 2004; Yin et al., 2007, 2009). In this context, treatment of MCF-10A cells with apigenin, and not baicalein, was also associated with caspase-9 cleavage (Fig. 3C) and loss of cell membrane integrity as determined by propidium iodide uptake (Fig. 3D), consistent with the induction of apoptotic cell death.

Fig. 3.

Apigenin, but not baicalein, down-regulates MUC1 in MCF-10A cells. A, MCF-10A cells were treated with the indicated concentrations of apigenin and baicalein for 3 days, washed, and then treated for an additional 3 days. Lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. B, MCF-10A cells were treated with the indicated concentrations apigenin (●) and baicalein (■) for 3 days. Viable cell number was determined by the MTS assay. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as the percentage of control growth in the presence of DMSO. C, MCF-10A cells were treated with DMSO, 75 μM apigenin, or 75 μM baicalein for 3 days. Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. D, MCF-10A cells were treated with DMSO, 75 μM apigenin, or 75 μM baicalein for 3 days, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells with loss of cell membrane integrity is shown.

Apigenin, but Not Baicalein, Down-Regulates MUC1 in MCF-7 Breast Cancer Cells.

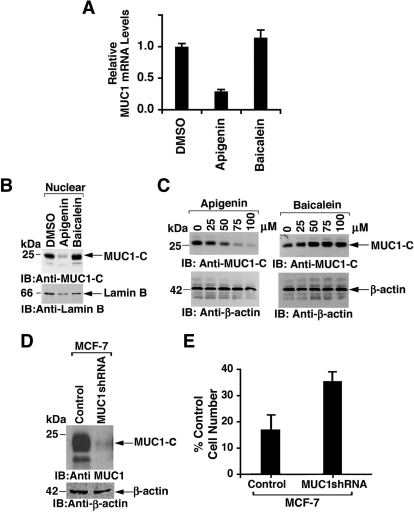

In MCF-7 cells, treatment with apigenin was associated with down-regulation of MUC1 mRNA levels, whereas baicalein had no apparent effect compared with control (Fig. 4A). In concert with these results, apigenin and not baicalein decreased the expression of the MUC1-C protein in the nucleus (Fig. 4B) and in whole-cell lysates (Fig. 4C). To assess MUC1-dependent effects of apigenin, the MCF-7 cells were transduced with an empty lentiviral vector or one expressing an MUC1 shRNA that was associated with a substantial decrease in MUC1-C levels (Fig. 4D). Silencing MUC1 partially decreased sensitivity of the MCF-7 cells to apigenin-induced decreases in cell number, consistent in part with an MUC1-dependent effect (Fig. 4E).

Fig. 4.

Apigenin suppresses MUC1 expression in MCF-7 cells. A, MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO, 75 μM apigenin, or 75 μM baicalein for 3 days. Total RNA was assayed for MUC1 mRNA levels by quantitative reverse-transcription polymerase chain reaction. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as relative MUC1 mRNA levels compared with that obtained in cells treated with DMSO. B and C, MCF-7 cells were treated with the 75 μM (B) or the indicated concentrations (C) of apigenin and baicalein for 3 days. Nuclear (B) and whole-cell lysates (C) were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. D, lysates from MCF-7 cells infected to stably express a control lentivirus and one with a MUC1 short hairpin RNA were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. E, the indicated MCF-7 cells were treated with 75 μM apigenin for 3 days. Viable cell number was determined by the MTS assay. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as the percentage of control cell number in the presence of DMSO.

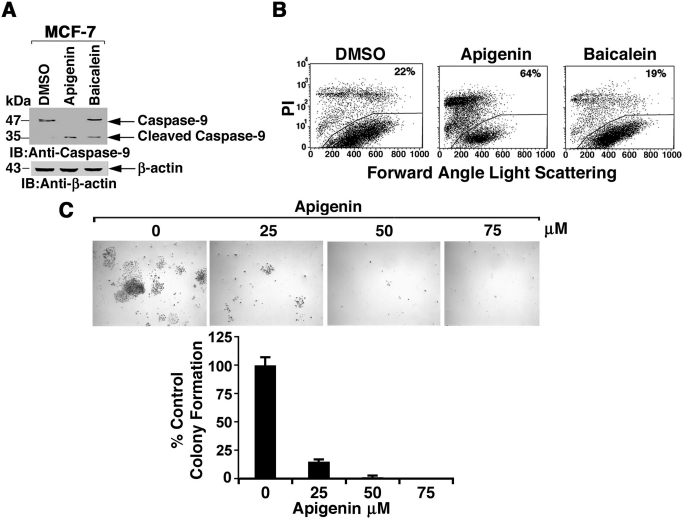

Down-regulation of MUC1-C expression in MCF-7 cells is associated with a loss of viability (Jin et al., 2010). By extension, apigenin treatment was associated with cleavage of caspase-9 (Fig. 5A) and loss of cell membrane integrity (Fig. 5B). To assess the effects on survival, MCF-7 cells were treated with apigenin and then analyzed for colony formation (Fig. 5C). In concert with the loss of cell membrane integrity, treatment with 25 μM apigenin was associated with a substantial decrease in colonies and complete loss of survival at higher concentrations (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

Apigenin inhibits MCF-7 clonogenic survival. A, MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO, 75 μM apigenin, or 75 μM baicalein for 3 days. Lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. B, MCF-7 cells were treated with DMSO, 75 μM apigenin, or 75 μM baicalein for 3 days, stained with propidium iodide, and analyzed by flow cytometry. The percentage of cells with loss of cell membrane integrity is included. C, MCF-7 cells were plated at a density of 1000 cells/6-cm dish. At 24 h after seeding, DMSO or apigenin at concentrations of 25, 50, and 75 μM was added to the medium. After 2 weeks, colonies were stained with crystal violet. The results (mean ± S.D. of 3 determinations) are expressed as the percentage of control colony formation in the presence of DMSO.

MUC1-Dependent Effects of Apigenin on Survival of HCC1937 and BT474 Breast Cancer Cells.

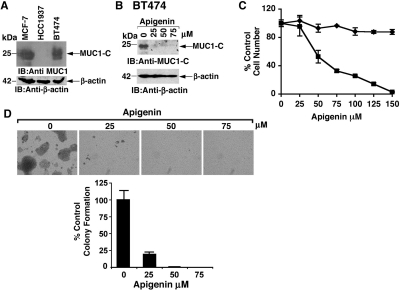

Other studies were performed with HCC1937 breast cancer cells that have low to undetectable MUC1-C levels and BT474 breast cancer cells that express MUC1-C at levels comparable with those in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 6A). As found in MCF-7 cells, treatment of BT474 cells with apigenin was associated with down-regulation of MUC1-C expression (Fig. 6B). In addition, apigenin treatment of BT474 cells, but not HCC1937 cells, was associated with loss of viability (Fig. 6C). Treatment of BT474 cells was also associated with concentration-dependent decreases in clonogenic survival (Fig. 6D). These findings and those obtained with MCF-10A and MCF-7 cells indicated that apigenin down-regulates MUC1-C expression in association with apigenin-induced loss of viability.

Fig. 6.

Effects of apigenin on breast cancer cells without and with endogenous MUC1 expression. A, lysates from human MCF-7, HCC1937, and BT474 cells were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. B, BT474 cells were treated with indicated concentrations of apigenin and baicalein for 3 days, washed, and then treated for an additional 3 days. Lysates were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. C. BT474 (■) and HCC1937 (♦) cells were treated with apigenin for 3 days. Viable cell numbers were determined by MTS assay. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as the percentage of control growth in the presence of DMSO. D, BT474 cells were plated at a density of 5000 cells/6-cm dish. At 24 h after seeding, apigenin at concentrations of 25, 50, and 75 μM was added to the medium. After 2 weeks, colonies were stained with crystal violet. The results (mean ± S.D. of three determinations) are expressed as the percentage of control colony formation.

Discussion

Identification of Small-Molecule MUC1-CD Dimerization Inhibitors.

The oncogenic MUC1-C transmembrane subunit forms dimers that are mediated by a CQC motif in its cytoplasmic domain and are necessary for its nuclear localization (Leng et al., 2007). In turn, nuclear MUC1-C interacts with certain transcription factors on promoters of their target genes (Kufe, 2009) and activates gene signatures associated with tumorigenesis that are predictive of poor survival in patients with breast and lung cancer (Khodarev et al., 2009; Pitroda et al., 2009; MacDermed et al., 2010). In addition, expression of the MUC1-C subunit that is defective for dimerization blocks tumorigenicity of human cancer cells, indicating a dominant-negative effect of disabled MUC1-C monomers (Leng et al., 2007). These findings provided support for the development of a screen to identify small-molecule inhibitors of MUC1-C dimerization as an approach to block its oncogenic function. In that line of reasoning, a plate-based assay was developed to screen compounds in selected known bioactives (ICCB3, NINDS2, Prestwick1, Microsource1; BIOMOL Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, PA) and natural product extract (NCDDG8, MMV6) libraries available through the ICCB-Longwood, Harvard Medical School Screening Facility. As scored by over 50% inhibition of MUC1-CD dimerization, the percentage of positive hits was lowest (1%) in the BIOMOL ICCB3 library of known bioactives and highest (>3%) in the MMV6 fungal extract library. The BIOMOL ICCB3 library includes diverse classes of compounds, including ion-channel blockers, second-messenger modulators, kinase inhibitors, gene regulation agents, and other well-characterized compounds that disrupt cell pathways. Positive hits were further characterized over a range of concentrations to confirm results in the initial screen and to define an IC50. Among other compounds of interest, we selected the naturally occurring plant flavone apigenin as one candidate for further study based in part on its known anticancer properties (Shukla and Gupta, 2010). Apigenin is an orally bioavailable compound in animals and humans that has also been widely studied for its anti-inflammatory properties and as a cancer chemopreventive agent (Meyer et al., 2006; Shukla and Gupta, 2010). In addition, apigenin is well tolerated in animal tumor models and has little if any toxicity to normal bone marrow cells in vivo or in vitro (Kim et al., 2007; Siddique and Afzal, 2009; Shukla and Gupta, 2010; Silvan et al., 2010). To our knowledge, there has been no evidence for involvement of apigenin in the regulation of MUC1 expression or signaling.

Apigenin Blocks MUC1-C Dimerization and Signaling.

The effects of apigenin on MUC1-CD dimerization observed in the plate-based assay were confirmed using soluble MUC1-CD and in 293 cells expressing Flag- and GFP-tagged MUC1-CD. To address the issue of specificity, we compared the inhibition of MUC1-CD dimerization by apigenin with that obtained with the highly related flavone baicalein that also has three hydroxyl groups, but at positions 5, 6, and 7 rather than at 4′, 5, and 7 in apigenin. In addition, like apigenin, baicalein has anticancer activity (Taniguchi et al., 2008). Surprisingly, however, unlike apigenin, baicalein had little if any effect on MUC1-CD dimerization, indicating that positioning of the hydroxyls is of importance for inhibition. Nuclear localization of MUC1-C was also blocked by apigenin, but not baicalein, consistent with the requirement of MUC1-C dimerization for interaction with importin β and localization to the nucleus (Leng et al., 2007). In concert with these results, inhibition of MUC1-C dimerization with a cell-penetrating peptide that blocks the CQC motif in the cytoplasmic domain also decreased localization of MUC1-C to the nucleus (Raina et al., 2009). As noted above, the oncogenic function of MUC1-C relates, at least in part, to its induction of gene signatures that confer tumorigenesis, angiogenesis, and extracellular matrix remodeling (Khodarev et al., 2009; Pitroda et al., 2009; MacDermed DM et al., 2010). Moreover, MUC1-C interacts with nuclear factor p65 and STAT1/3 on the MUC1 promoter that, in turn, autoinduces activation of MUC1 expression (Ahmad et al., 2009, 2011; Khodarev et al., 2010). In this way, blocking MUC1-C dimerization and nuclear localization with apigenin would be expected to decrease MUC1 expression at the mRNA and protein levels. Indeed, apigenin treatment was associated with down-regulation of MUC1-C protein expression. These findings do not exclude the possibility that apigenin, which can affect diverse pathways (Shukla and Gupta, 2010), suppresses MUC1 expression by other mechanisms unrelated to blocking MUC1-C dimerization. Nonetheless, the apigenin-induced inhibition of MUC1-C dimerization and nuclear localization is consistent at least in large part with the observed down-regulation of MUC1 expression.

Effects of Blocking MUC1-C Dimerization.

Studies with a cell-penetrating peptide drug that binds to the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain at the CQC motif have demonstrated that blocking MUC1-C dimerization is associated with inhibition of breast cancer cell growth and survival (Raina et al., 2009). Moreover, the MUC1-C dimerization peptide inhibitor was ineffective against MUC1-negative carcinoma cells (Joshi et al., 2009), supporting selectivity of this agent. In the present studies, apigenin-induced inhibition of MUC1-C dimerization in MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells was associated with apoptotic cell death. Treatment of MUC1-positive MCF-7 and BT474 breast cancer cells with apigenin was also associated with the loss of clonogenic survival, consistent with the effects of the effects of the peptide inhibitor of MUC1-C dimerization. In MCF-7 cells, apigenin has been shown to target ERα-dependent signaling (Long et al., 2008). In this regard, MUC1-C interacts with ERα and promotes ERα-dependent gene expression (Wei et al., 2006). Thus, the inhibitory effects of apigenin on MUC1-C dimerization and nuclear localization could contribute to disruption of ERα signaling. Other studies have reported that apigenin induces apoptosis of breast cancer cells by inhibiting the PI3K→Akt pathway and down-regulating ErbB2 expression (Way et al., 2004, 2005; Lee et al., 2008). MUC1-C contributes to activation of the PI3K→Akt pathway (Raina et al., 2004) and interacts with the ErbB2 signaling pathway (Ren et al., 2006). These observations and those in the present work invoke the possibility that apigenin-induced inhibition of MUC1-C dimerization may be responsible, at least in part, for the observed effects of this agent on breast cancer cells. Nonetheless, apigenin has been linked to the disruption of diverse pathways in breast and other types of carcinoma cells that are not formally attributable to loss of MUC1-C function. In that line of reasoning, the present findings that apigenin, and not baicalein, blocks dimerization of the MUC1-C cytoplasmic domain indicate that MUC1-C is likely a “druggable” target for the development of more specific small-molecule inhibitors of its oncogenic function. Overexpression of MUC1-C, as found in human carcinomas, blocks apoptosis in the response to DNA damage (Ren et al., 2004). Therefore, small-molecule inhibitors of MUC1-C function may be effective in combination with genotoxic anticancer agents. Moreover, treatment with MUC1-C peptide inhibitors in preclinical models has indicated that targeting this oncoprotein has been associated with limited toxicity (Raina et al., 2009). Studies are therefore underway using computer-based design of small molecules to identify agents that are more potent and selective than apigenin in inhibiting dimerization of the MUC1-C subunit.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health National Cancer Institute [Grants CA097098, CA42808].

D.K. holds equity in Genus Oncology and is a consultant to the company.

Article, publication date, and citation information can be found at http://molpharm.aspetjournals.org.

doi:10.1124/mol.110.070797.

- MUC1

- mucin 1

- MUC1-C

- mucin 1 C-terminal subunit

- MUC1-CD

- mucin 1 cytoplasmic domain

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- HRP

- horseradish peroxidase

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- GFP

- green fluorescent protein

- ERα

- estrogen receptor-α

- MTS

- 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxyphenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium, inner salt

- PI3K

- PI3K, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- ICCB

- Institute of Chemistry and Cell Biology.

Authorship Contributions

Participated in research design: Zhou, Rajabi, and Kufe.

Conducted experiments: Zhou and Rajabi.

Performed data analysis: Zhou and Rajabi.

Wrote or contributed to the writing of the manuscript: Zhou, Rajabi, and Kufe.

Other: Kufe acquired funding for the research.

References

- Ahmad R, Raina D, Joshi MD, Kawano T, Ren J, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2009) MUC1-C oncoprotein functions as a direct activator of the nuclear factor-kappaB p65 transcription factor. Cancer Res 69:7013–7021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad R, Rajabi H, Kosugi M, Joshi MD, Alam M, Vasir B, Kawano T, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2011) MUC1-C oncoprotein promotes STAT3 activation in an autoinductive regulatory loop. Sci Signal 4:ra9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Croce MV, Isla-Larrain MT, Rua CE, Rabassa ME, Gendler SJ, Segal-Eiras A. (2003) Patterns of MUC1 tissue expression defined by an anti-MUC1 cytoplasmic tail monoclonal antibody in breast cancer. J Histochem Cytochem 51:781–788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Chen D, Liu D, Yin L, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2005) MUC1 oncoprotein blocks glycogen synthase kinase 3beta-mediated phosphorylation and degradation of beta-catenin. Cancer Res 65:10413–10422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin C, Rajabi H, Kufe D. (2010) miR-1226 targets expression of the mucin 1 oncoprotein and induces cell death. Int J Oncol 37:61–69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi MD, Ahmad R, Yin L, Raina D, Rajabi H, Bubley G, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2009) MUC1 oncoprotein is a druggable target in human prostate cancer cells. Mol Cancer Ther 8:3056–3065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodarev N, Ahmad R, Rajabi H, Pitroda S, Kufe T, McClary C, Joshi MD, MacDermed D, Weichselbaum R, Kufe D. (2010) Cooperativity of the MUC1 oncoprotein and STAT1 pathway in poor prognosis human breast cancer. Oncogene 29:920–929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khodarev NN, Pitroda SP, Beckett MA, MacDermed DM, Huang L, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. (2009) MUC1-induced transcriptional programs associated with tumorigenesis predict outcome in breast and lung cancer. Cancer Res 69:2833–2837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JS, Eom JI, Cheong JW, Choi AJ, Lee JK, Yang WI, Min YH. (2007) Protein kinase CK2alpha as an unfavorable prognostic marker and novel therapeutic target in acute myeloid leukemia. Clin Cancer Res 13:1019–1028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufe DW. (2009) Mucins in cancer: function, prognosis and therapy. Nat Rev Cancer 9:874–885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kufe D, Inghirami G, Abe M, Hayes D, Justi-Wheeler H, Schlom J. (1984) Differential reactivity of a novel monoclonal antibody (DF3) with human malignant versus benign breast tumors. Hybridoma 3:223–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee WJ, Chen WK, Wang CJ, Lin WL, Tseng TH. (2008) Apigenin inhibits HGF-promoted invasive growth and metastasis involving blocking PI3K/Akt pathway and beta 4 integrin function in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 226:178–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leng Y, Cao C, Ren J, Huang L, Chen D, Ito M, Kufe D. (2007) Nuclear import of the MUC1-C oncoprotein is mediated by nucleoporin Nup62. J Biol Chem 282:19321–19330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Liu D, Chen D, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2003) Human DF3/MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein functions as an oncogene. Oncogene 22:6107–6110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long X, Fan M, Bigsby RM, Nephew KP. (2008) Apigenin inhibits antiestrogen-resistant breast cancer cell growth through estrogen receptor-alpha-dependent and estrogen receptor-alpha-independent mechanisms. Mol Cancer Ther 7:2096–2108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDermed DM, Khodarev NN, Pitroda SP, Edwards DC, Pelizzari CA, Huang L, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. (2010) MUC1-associated proliferation signature predicts outcomes in lung adenocarcinoma patients. BMC Medical Genomics 3:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer H, Bolarinwa A, Wolfram G, Linseisen J. (2006) Bioavailability of apigenin from apiin-rich parsley in humans. Ann Nutr Metab 50:167–172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel D, Shukla S, Gupta S. (2007) Apigenin and cancer chemoprevention: progress, potential and promise (review). Int J Oncol 30:233–245 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perey L, Hayes DF, Maimonis P, Abe M, O'Hara C, Kufe DW. (1992) Tumor selective reactivity of a monoclonal antibody prepared against a recombinant peptide derived from the DF3 human breast carcinoma-associated antigen. Cancer Res 52:2563–3568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitroda SP, Khodarev NN, Beckett MA, Kufe DW, Weichselbaum RR. (2009) MUC1-induced alterations in a lipid metabolic gene network predict response of human breast cancers to tamoxifen treatment. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5837–5841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina D, Ahmad R, Joshi MD, Yin L, Wu Z, Kawano T, Vasir B, Avigan D, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2009) Direct targeting of the mucin 1 oncoprotein blocks survival and tumorigenicity of human breast carcinoma cells. Cancer Res 69:5133–5141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raina D, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2004) The MUC1 oncoprotein activates the anti-apoptotic phosphoinositide 3-kinase/Akt and Bcl-xL pathways in rat 3Y1 fibroblasts. J Biol Chem 279:20607–20612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy S, Duraisamy S, Barbashov S, Kawano T, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2007) The MUC1 and galectin-3 oncoproteins function in a microRNA-dependent regulatory loop. Mol Cell 27:992–1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Agata N, Chen D, Li Y, Yu WH, Huang L, Raina D, Chen W, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2004) Human MUC1 carcinoma-associated protein confers resistance to genotoxic anticancer agents. Cancer Cell 5:163–175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren J, Bharti A, Raina D, Chen W, Ahmad R, Kufe D. (2006) MUC1 oncoprotein is targeted to mitochondria by heregulin-induced activation of c-Src and the molecular chaperone HSP90. Oncogene 25:20–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla S, Gupta S. (2010) Apigenin: a promising molecule for cancer prevention. Pharm Res 27:962–978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siddique YH, Afzal M. (2009) Antigenotoxic effect of apigenin against mitomycin C induced genotoxic damage in mice bone marrow cells. Food Chem Toxicol 47:536–539 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvan S, Manoharan S, Baskaran N, Singh AK. (2010) Apigenin: a potent antigenotoxic and anticlastogenic agent. Biomed Pharmacother doi:10/1016/j.biopha.2010.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi H, Yoshida T, Horinaka M, Yasuda T, Goda AE, Konishi M, Wakada M, Kataoka K, Yoshikawa T, Sakai T. (2008) Baicalein overcomes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand resistance via two different cell-specific pathways in cancer cells but not in normal cells. Cancer Res 68:8918–8927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way TD, Kao MC, Lin JK. (2004) Apigenin induces apoptosis through proteasomal degradation of HER2/neu in HER2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells via the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt-dependent pathway. J Biol Chem 279:4479–4489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Way TD, Kao MC, Lin JK. (2005) Degradation of HER2/neu by apigenin induces apoptosis through cytochrome c release and caspase-3 activation in HER2/neu-overexpressing breast cancer cells. FEBS Lett 579:145–152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Xu H, Kufe D. (2005) Human MUC1 oncoprotein regulates p53-responsive gene transcription in the genotoxic stress response. Cancer Cell 7:167–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Xu H, Kufe D. (2006) MUC1 oncoprotein stabilizes and activates estrogen receptor alpha. Mol Cell 21:295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2007) Mucin 1 oncoprotein blocks hypoxia-inducible factor 1alpha activation in a survival response to hypoxia. J Biol Chem 282:257–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin L, Kharbanda S, Kufe D. (2009) MUC1 oncoprotein promotes autophagy in a survival response to glucose deprivation. Int J Oncol 34:1691–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]