Abstract

Purpose

To describe trends in the aggressiveness of end-of-life (EOL) cancer care in a universal health care system in Ontario, Canada, between 1993 and 2004, and to compare with findings reported in the United States.

Methods

A population-based, retrospective, cohort study that used administrative data linked to registry data. Aggressiveness of EOL care was defined as the occurrence of at least one of the following indicators: last dose of chemotherapy received within 14 days of death; more than one emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; more than one hospitalization within 30 days of death; or at least one intensive care unit (ICU) admission within 30 days of death.

Results

Among 227,161 patients, 22.4% experienced at least one incident of potentially aggressive EOL cancer care. Multivariable analyses showed that with each successive year, patients were significantly more likely to encounter some aggressive intervention (odds ratio, 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.02). Multiple emergency department (ED) visits, ICU admissions, and chemotherapy use increased significantly over time, whereas multiple hospital admissions declined (P < .05). Patients were more likely to receive aggressive EOL care if they were men, were younger, lived in rural regions, had a higher level of comorbidity, or had breast, lung, or hematologic malignancies. Chemotherapy and ICU utilization were lower in Ontario than in the United States.

Conclusion

Aggressiveness of cancer care near the EOL is increasing over time in Ontario, Canada, although overall rates were lower than in the United States. Health system characteristics and patient or physician cultural factors may play a role in the observed differences.

INTRODUCTION

Despite advances in early detection, treatment, and survival, cancer remains a leading cause of death in most developed countries. The disease accounts for nearly 30% of all deaths in Canada1 and approximately one quarter of all deaths in the United States.2 With the number of deaths from cancer and other chronic diseases expected to increase as a result of a growing and aging population, the inevitable need for quality end-of-life care has become increasingly important.3 A number of measures of the quality of end-of-life care that can be evaluated by using administrative data have been developed and reported previously.4–6 These assess processes, such as overuse of chemotherapy; underuse of hospice care; and outcomes of frequent emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (possibly indicating misuse of aggressive intervention) near the end of life. Evaluation of these measures in Medicare claims for 28,777 patients older than age 65 years who died of cancer in the 1990s found steadily increasing use of aggressive care during that decade.5 Proposed reasons for this observation have included increasing technology available near the end of life, uneven availability of hospice and palliative care services, and financial incentives that exist in the United States to continue providing treatment when it is medically futile. Previous Canadian studies have also shown that a significant proportion of patients with cancer have indicators of poor quality end-of-life care, although they did not assess how this has changed over time.7–9 In Canada's universal health care system, the palliative care system is also a patchwork of services that varies interprovincially and regionally within provinces,3,10 although financial incentives for treatment may be significantly less. Patient and physician cultural factors may also result in different practice patterns between Canada and the United States.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the aggressiveness of end-of-life cancer care in Ontario, Canada, over a similar time frame. A secondary outcome was to compare patterns with those observed in the United States.

METHODS

Study Design and Cohort Selection

This is a population-based, retrospective study of a decedent cohort of all patients who died as a result of any cancer type in Ontario, Canada, between January 1, 1993, and December 31, 2004. We excluded patient cases if they did not have a valid provincial health insurance number; if they died within 30 days after the cancer diagnosis, and if they were younger than 20 years of age at death.

Data Sources

We used the Ontario Cancer Registry (OCR) to identify index cases of patients with a cancer cause of death. The OCR is a population-based cancer registry and is approximately 95% complete when all cancer diagnoses are considered.11,12 Index cases from the OCR were linked by using encrypted provincial health card numbers to the following data sources: the Ontario Health Insurance Plan claims database, which contains information on billing claims for physicians' services provided to Ontario residents; the Discharge Abstract Database,13 which contains diagnostic and procedure information on all discharges from acute care facilities for residents of Ontario; the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System,14 which captures information on patient visits to hospital and community-based ambulatory care, including day surgery, outpatient clinics, and emergency departments; the Registered Person's Database,15 which provides basic demographic information for anyone who has ever received an Ontario health card number; and the Statistics Canada 2006 census profile, which was used to obtain proxy measures of patient socioeconomic status. US data for comparison were derived from a previously published analysis.4

Main Outcome Measure

We created a composite measure of aggressive end-of-life care, which was defined as the occurrence of at least one of the following indicators: received the last dose of chemotherapy within 14 days of death; had more than one emergency department (ED) visit within 30 days of death; had more than one hospitalization within 30 days of death; or had at least one ICU admission within 30 days of death. These indicators were measured as described elsewhere.5 Data sources and definitions are provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only). In the uncommon instances that patients paid out-of-pocket or with private insurance for cancer drugs not paid for by the provincial insurance program or on a clinical trial, treatment would still be captured through physician fee codes for treatment administration.

Variable Definitions

Patient demographics.

Differences in aggressiveness of care were examined across patient sex, age, income, and region of residence. Median income by dissemination area was used from the Statistics Canada 2006 Census and was linked to patient postal code from the Registered Person's Database to assign neighborhood income quintile per patient. We used city, postal code, and dissemination area of patient residence to derive Local Health Integration Network designation16 and rural residence. Patients were assigned rural residence if they lived in communities that had a population size of ≤ 10,000.

Disease characteristics.

We examined disease characteristics, such as duration of disease, comorbidity, and cancer type. Duration was calculated as the interval in years between the date of cancer diagnosis and death. The International Classification of Disease, ninth revision (ICD9) codes were used to identify type of cancer death. These were classified as breast (ICD9-174), lung (ICD9-162), colorectal (ICD9-153 and -154), prostate (ICD9-185), and hematologic (ICD9-196 and -200 to -208). Remaining cancer types were grouped into a category of other. Patient comorbidity was calculated by using the Deyo adaptation17 of the Charlson comorbidity index measure,18 which was computed from inpatient diagnoses in the last 6 months of life.

Statistical Analysis

We examined baseline descriptive characteristics of patients who experienced at least one indicator of aggressive care versus those who did not experience any aggressive intervention between 1993 and 2004. Significant differences between the two groups were compared by using t tests for continuous variables and χ2 analyses for categoric variables (P < .05).

Rates for each indicator of aggressive end-of-life care were computed per year from 1993 to 2004. The linear regression trend test was used to determine significance of trends over time. We compared these rates to those we have previously observed by using the same methods in US Medicare patients living in the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) regions who died as a result of cancer between 1993 and 1999. For comparisons with the US data, analyses were restricted to patients who were 65 years of age or older at death during the same time period. We computed crude rates only, to be comparable to the United States. When we subsequently standardized our analyses by age and sex to the 1993 Ontario cohort, the standardized and crude rates were similar as a result of the aging population (data not shown).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis was used to predict the likelihood of experiencing any aggressive care. In the logistic model, we adjusted for known determinants including age at death, sex, cancer type, income, Charlson score, duration of disease, urban or rural residence, and health region as defined by the Local Health Integration Network.4,5,7 We also conducted a multivariate trend test to determine whether time trends were significant by adding year of death to this model. All analyses were performed with SAS 9.1.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Baseline Characteristics

Between 1993 and 2004, there were 272,791 patients who had a cancer cause of death in Ontario, Canada. After excluding patients who did not have a valid health card number (n = 11,275), who died within 30 days after cancer diagnosis (n = 32,728), and who were younger than 20 years of age at death (n = 1,627), the study cohort included a total of 227,161 patients. Among the study cohort, 22.4% experienced at least one indicator of aggressive end-of-life care. Table 1compares characteristics of patients who did and did not experience any aggressive cancer care at the end of life. Appendix Table A2 (online only) compares the demographic profiles and disease characteristics of the US and Canadian cohorts among patients age 65 years or older, finding no meaningful differences except for slightly higher comorbidity and rural residence in Ontario.

Table 1.

Baseline Demographic and Clinical Characteristics of Ontario Patients Who Had a Cancer Cause of Death Between 1993 and 2004

| Characteristic | Patients Not Experiencing Any Aggressive Care (n = 176,381) | Patients Experiencing Any Aggressive Care (n = 50,780) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 70.6 | 66.6 | < .01 |

| SD | 12.5 | 12.9 | |

| % female | 48.2 | 42.1 | < .01 |

| Mean Charlson score, per point | 0.51 | 0.72 | < .01 |

| SD | 0.95 | 1.12 | |

| Mean duration of disease, years | 3.06 | 2.81 | < .01 |

| SD | 4.6 | 4.4 | |

| Cancer type, % | < .01 | ||

| Breast | 9.2 | 8.9 | |

| Colorectal | 11.2 | 9.3 | |

| Hematologic | 8.0 | 14.5 | |

| Lung | 23.7 | 25.2 | |

| Prostate | 40.8 | 36.9 | |

| Other | 7.0 | 5.2 | |

| Income quintile, % | < .01 | ||

| 1 (lowest) | 21.5 | 21.3 | |

| 2 | 21.5 | 21.7 | |

| 3 | 19.8 | 20.2 | |

| 4 | 18.1 | 18.5 | |

| 5 | 18.3 | 17.7 | |

| % in rural residence | 15.6 | 18.9 | < .01 |

| Region, % | < .01 | ||

| a | 6.1 | 6.4 | |

| b | 9.0 | 8.0 | |

| c | 5.0 | 4.6 | |

| d | 13.7 | 12.0 | |

| e | 3.2 | 4.3 | |

| f | 5.8 | 6.1 | |

| g | 9.8 | 8.8 | |

| h | 9.2 | 10.7 | |

| i | 10.9 | 11.8 | |

| j | 5.4 | 4.5 | |

| k | 9.7 | 8.8 | |

| l | 3.5 | 4.4 | |

| m | 6.0 | 7.4 | |

| n | 2.4 | 2.2 |

NOTE. Missing observations from income (n = 1,834) and region (n = 367) are excluded.

Abbreviation: SD, standard deviation.

Indicators of Aggressive Care Over Time

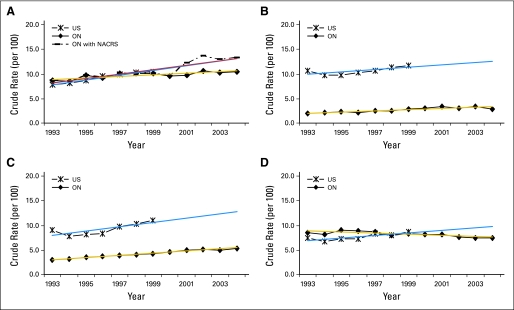

Figure 1 depicts trends over time in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life among Ontario and US Medicare patients age 65 years or older. In Ontario, upward trends were observed for ED visits (8.60% to 10.53%), chemotherapy use (2.02% to 2.88%), and ICU admissions (3.06% to 5.39%), although the rate of hospital admissions slightly decreased (8.5% to 7.5%) between 1993 and 2004. Tests for trend showed that changes over time were significant for all indicators of aggressive care near the end of life (P < .01). Utilization of chemotherapy and ICU near the end of life were lower in Ontario than in the United States.

Fig 1.

Trends in end-of-life care in Ontario (ON) compared with the United States (US). (A) Emergency department visits; (B) chemotherapy; (C) intensive care unit admissions; (D) hospitalizations. NACRS, National Ambulatory Care Reporting System.

Predictors of Aggressive Care

In multivariable logistic analyses, we found a significant trend toward more aggressive care with each successive year (odds ratio [OR], 1.01; 95% CI, 1.01 to 1.02). We also found that age, sex, geographic region, and rurality were significant independent predictors of the likelihood of having one or more indicators of aggressive care after adjustment for other explanatory variables (Table 2). Increasing age decreased the odds of experiencing an indicator of aggressive care (OR, 0.97 for each increasing year; 95% CI, 0.97 to 0.98). Men were more likely to experience aggressive care (OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.25 to 1.31), as were rural-dwelling patients (OR, 1.34, 95% CI, 1.30 to 1.38). Cancer type and comorbidity score also played a significant role in predicting aggressive care. As examples, patients with hematologic malignancies were 85% more likely to be hospitalized in the last month of life than patients with prostate cancer. Patients with breast cancer were 88% more likely to receive chemotherapy in the last 2 weeks of life than patients with colorectal cancer (P < .001).

Table 2.

Multivariable Logistic Regression Analysis Predicting Aggressive Care

| Any Aggressive Care |

||

|---|---|---|

| Factor | OR | 95% CI |

| Year of death | 1.01 | 1.01 to 1.02 |

| Age, years | 0.97 | 0.97 to 0.98 |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 1.28 | 1.25 to 1.31 |

| Female | 1.00 | — |

| Charlson score, per point | 1.25 | 1.24 to 1.26 |

| Duration of disease, years | 1.00 | 1.00 to 1.00 |

| Cancer type | ||

| Breast | 1.22 | 1.17 to 1.27 |

| Colorectal | 1.00 | 0.96 to 1.03 |

| Hematologic | 2.01 | 1.94 to 2.08 |

| Lung | 1.16 | 1.13 to 1.19 |

| Prostate | 0.89 | 0.85 to 0.93 |

| Other | 1.00 | — |

| Income quintile | ||

| 1 (lowest) | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.06 |

| 2 | 1.03 | 1.00 to 1.07 |

| 3 | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.08 |

| 4 | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.06 |

| 5 | 1.00 | — |

| Rural | ||

| Yes | 1.34 | 1.30 to 1.38 |

| No | 1.00 | — |

| Region | ||

| a | 1.08 | 1.03 to 1.14 |

| b | 0.89 | 0.84 to 0.93 |

| c | 0.94 | 0.89 to 1.00 |

| d | 0.95 | 0.91 to 0.99 |

| e | 1.35 | 1.27 to 1.43 |

| f | 1.11 | 1.05 to 1.17 |

| g | 1.27 | 1.21 to 1.33 |

| h | 1.13 | 1.08 to 1.18 |

| i | 0.82 | 0.77 to 0.87 |

| j | 0.92 | 0.88 to 0.96 |

| k | 1.22 | 1.15 to 1.30 |

| l | 1.18 | 1.12 to 1.24 |

| m | 0.93 | 0.86 to 1.00 |

| n | 1.00 | — |

Abbreviation: OR, odds ratio.

DISCUSSION

Our study shows that 22.4% of Ontario residents who died as a result of cancer between 1993 and 2004 experienced some form of potentially aggressive care near the end of life. With each successive year, patients had a 1% increased risk of encountering some aggressive intervention at the end of life. Notably, patients were significantly more likely to receive chemotherapy and to have frequent ED visits and ICU admissions. The rate of multiple hospital admissions, however, declined over this time. This may be in large part due to health system restructuring and cost constraints across Canada during the 1980s and 1990s, which led to hospital closures and a rapid decline in hospital beds for inpatient utilization. Effectively, this shifted hospital and financial resources from inpatient settings to ambulatory clinics over time.19 Although the observed changes in the measures are small from year to year, the trends are steady and become important over time.

A growing body of literature suggests that the use of palliative care is associated with improved quality of life and a reduced likelihood of aggressive care.9,20 In Ontario, however, a comprehensive provincial palliative care delivery program does not exist.10 The overall trend toward increasing intensity of end-of-life care is likely attributable, in large part, to the downstream effects of this patchwork of palliative services to manage the growing number of cancer diagnoses and deaths.

Similar to other studies that have evaluated the intensity of end-of-life cancer care, we also found that patient factors, such as younger age, male sex, region of residence, and rurality, as well as disease characteristics, such as cancer type and comorbidity score, were significant independent predictors of aggressive end-of-life care.4,5,7 The geographic variation observed is likely attributable to variations in care patterns caused by differences in care protocols and access to available palliative care resources.10

The overall intensity of end-of-life cancer care in Ontario, Canada, appears to be lower than in the US SEER Medicare regions. Although we were unable to test any hypothesized reasons for this difference with the data available, potential explanations include health system factors, patient preferences, and provider practice patterns. For example, financial incentives exist in the United States that may induce some practitioners to continue providing anticancer treatment, whereas, in Ontario, multiple lines of chemotherapy are not always paid for by the provincial insurance system. In these instances, it might have to come out of a cancer center's pharmacy budget or the patient may have to pay out of pocket or with private insurance, causing a disincentive to undergo such treatment. The Canadian health care system does not allow the same degree of overuse for chemotherapy as is seen in the United States by simply not paying for some of this care. Even with weaker incentives for treatment, however, the use of aggressive care in Ontario is still increasing over time.

A major strength of this study is that it is a population-based cohort that included information on all patients and hospitals in Ontario by using data that are continuously collected on patients of all ages. Research has shown that the indicators of aggressive end-of-life cancer care used in this study are fully measurable with Ontario administrative data.21 In addition, the quality of the Ontario Cancer Registry is high with respect to case ascertainment and vital status.11,22 There are some limitations in this study to consider, though. First, although we strove to operationalize the measures as closely as possible, the data sources in the United States and Canada are different and use different coding systems, which may introduce variability between them and reduce comparability. For example, the US measures included a definition of hospice patients not comparable to the Ontario context. Still, the similarities in observations are striking. Our study was conducted by using administrative health data with a retrospective, cohort design. As is the case with any study relying on administrative health care data, the data sources used were not collected for health research purposes. As such, we were unable to capture other potential determinants of aggressive end-of-life care in patients with cancer, such as patient preferences, treatment setting, availability and use of palliative and other supportive care services, and provider factors.4,5,7

We have described predictors and trends in aggressive end-of-life care in a decedent cohort of patients in Ontario, Canada, and have provided comparisons with similar data from the United States. In both countries, the aggressiveness of end-of-life care is increasing over time. In Canada, the United States, and other countries, efforts are underway to optimize the quality and outcomes of end-of-life care by integrating palliative services into a comprehensive cancer care plan.23,24 Indeed, health planners around the world face similar challenges despite differences in models of health system delivery and reimbursement. For example, the need for better symptom control to prevent avoidable admissions, improved continuity of care, better patient education to manage expectations, and earlier incorporation of palliative care have been acknowledged by researchers and health planners in both Ontario and the United States.9,24–26 There are important opportunities to learn from each other, particularly from cancer centers or regional cancer programs that have successfully integrated palliative care. We must ensure that appropriate resources are available for palliation and align incentives to optimize their utilization.

Appendix

Table A1.

Indicator Definitions and Data Sources

| Quality Indicator | Numerator | Denominator |

|---|---|---|

| Last dose of chemotherapy within 14 days of death | No. of patients with OHIP fee codes G281, G339, G345, G381, or G359 within 14 days of death* | No. of patients with any cancer cause of death† |

| Frequency of ED visits17 | No. of patients with more than one ED visit within 30 days before death. More than one ED visit was defined as visits occurring more than 24 hours apart‡§ | No. of patients with any cancer cause of death† |

| More than one hospitalization in the last month of life | No. of patients with more than one acute care hospital admission within 30 days before death‖ | No. of patients with any cancer cause of death† |

| ICU days near the end of life18 | No. of patients with OHIP fee codes G400, G401, G402, G405, G406, G407, G557, G558, or G559 within 30 days before death* | No. of patients with any cancer cause of death† |

Abbreviations: OHIP, Ontario Health Insurance Plan; ED, emergency department; ICU, intensive care unit.

From OHIP data.

From Ontario Cancer Registry data.

From OHIP and National Ambulatory Care Reporting System data.

Because ambulatory care data from National Ambulatory Care Reporting System became available from 2002 onward, we calculated the ED visits indicator with OHIP records alone and with OHIP records plus National Ambulatory Care Reporting System records combined.

From Discharge Abstract Database data.

Table A2.

Descriptive Characteristics of Study Patients Who Had a Cancer Cause of Death at Age 65 Years or Older in Ontario From 1993 to 2004 and in US SEER-Medicare Regions From 1991 to 2000

| Characteristic | Ontario(n = 184,242) | United States(n = 215,484) |

|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years | 76.7 | 77.6 |

| SD | 7.4 | 7.5 |

| Mean age at diagnosis, years | 73.9 | 75.4 |

| SD | 8.3 | 8.0 |

| % female | 46.0 | 49.5 |

| Mean Charlson score | 0.64 | 0.43 |

| SD | 1.04 | 0.94 |

| Mean duration of disease, years | 2.8 | 2.3 |

| SD | 4.7 | 3.4 |

| Cancer type, % | ||

| Colorectal | 11.1 | 12.0 |

| Lung | 24.5 | 25.8 |

| Breast | 6.8 | 7.0 |

| Prostate | 7.8 | 9.4 |

| Hematologic | 9.7 | 10.1 |

| Other | 40.1 | 35.7 |

| Income quintile, % | ||

| 1 (lowest) | 22.4 | 21.4 |

| 2 | 22.3 | 19.6 |

| 3 | 20.0 | 19.7 |

| 4 | 17.6 | 19.7 |

| 5 | 17.8 | 19.6 |

| Rural residence, % | ||

| Yes | 16.6 | 9.8 |

Abbreviations: SEER, Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results; SD, standard deviation.

Footnotes

Supported by the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research through funding provided by the Government of Ontario and by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care; and by Grant No. CA 91753-02 from the National Cancer Institute.

The opinions, results, and conclusions reported in this article are those of the authors and are independent from the funding sources. No endorsement by Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, the Government of Ontario, or Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care is intended or should be inferred.

Presented at the Institute on Innovations in Palliative Care in Toronto, Ontario, in May 2009.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Thi H. Ho, Refik Saskin, Craig C. Earle

Financial support: Craig C. Earle

Data analysis and interpretation: Thi H. Ho, Lisa Barbera, Refik Saskin, Hong Lu, Bridget A. Neville, Craig C. Earle

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Statistics Canada: Leading causes of death in Canada, 2010. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2006. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2010;58:1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Canadian Cancer Society's Steering Committee: Canadian Cancer Statistics: 2010. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Canadian Cancer Society; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Earle CC, Landrum MB, Souza JM, et al. Aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life: Is it a quality-of-care issue? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:3860–3866. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.15.8253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Earle CC, Neville BA, Landrum MB, et al. Trends in the aggressiveness of cancer care near the end of life. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:315–321. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Earle CC, Park ER, Lai B, et al. Identifying potential indicators of the quality of end-of-life cancer care from administrative data. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1133–1138. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barbera L, Paszat L, Chartier C. Indicators of poor quality end-of-life cancer care in Ontario. J Palliat Care. 2006;22:12–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbera L, Paszat L, Qiu F. End-of-life care in lung cancer patients in Ontario: Aggressiveness of care in the population and a description of hospital admissions. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2008;35:267–274. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barbera L, Taylor C, Dudgeon D. Why do patients with cancer visit the emergency department near the end of life? CMAJ. 2010;182:563–568. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cancer Care Ontario: Improving the Quality of Palliative Care Services for Cancer Patients in Ontario. Toronto, Canada: Cancer Care Ontario; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robles SC, Marrett LD, Clarke EA, et al. An application of capture-recapture methods to the estimation of completeness of cancer registration. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:495–501. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90052-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Clarke EA, Marrett LD, Kreiger N. Cancer registration in Ontario: A computer approach. IARC Sci Publ. 1991;95:246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Richards J, Brown A, Hofman C. The data quality study of the Canadian Discharge Abstract Database: Proceedings of Statistics Canada Symposium. Ottawa, Canada: Statistics Canada; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI): CIHI Data Quality Study of Ontario Emergency Department Visits for 2004-2005. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Iron K, Zagorski BM, Sykora K, et al. Living and Dying in Ontario: An Opportunity for Improved Health Information—ICES Investigative Report. Toronto, Canada: Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ontario's Local Health Integration Networks: Queens Printer for Ontario. 2006. http://www.lhins.on.ca.

- 17.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45:613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: Development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40:373–383. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(87)90171-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Canadian Institute for Health Information: Hospital Trends in Canada: Results of a Project to Create a Historical Series of Statistical and Financial Data for Canadian Hospitals Over Twenty-Seven Years. Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Temel JS, Greer JA, Muzikansky A, et al. Early palliative care for patients with metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:733–742. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1000678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grunfeld E, Lethbridge L, Dewar R, et al. Towards using administrative databases to measure population-based indicators of quality of end-of-life care: Testing the methodology. Palliat Med. 2006;20:769–777. doi: 10.1177/0269216306072553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holowaty EJ, Moravan V, Lee G, et al. A Reabstraction Study to Estimate the Completeness and Accuracy of Data Elements in the Ontario Cancer Registry. A Report to Health Canada. Toronto, Canada: Ontario Cancer Registry; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cancer Care Ontario: Provincial Palliative Care Integration Project (PPCIP) Executive Summary. Toronto, Canada: Cancer Care Ontario; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferris FD, Bruera E, Cherny N, et al. Palliative cancer care a decade later: Accomplishments, the need, next steps—From the American Society of Clinical Oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3052–3058. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burge F, Lawson B, Johnston G. Family physician continuity of care and emergency department use in end-of-life cancer care. Med Care. 2003;41:992–1001. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200308000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sharma G, Freeman J, Zhang D, et al. Continuity of care and intensive care unit use at the end of life. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:81–86. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2008.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]