Abstract

Purpose

To identify whether a history of cancer is associated with specific geriatric syndromes in older patients.

Patients and Methods

Using the 2003 Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, we analyzed a national sample of 12,480 community-based elders. Differences in prevalence of geriatric syndromes between those with and without cancer were estimated. Multivariable logistic regressions were used to evaluate whether cancer was independently associated with geriatric syndromes.

Results

Two thousand three hundred forty-nine (18%) reported a history of cancer. Among those with cancer, 60.3% reported one or more geriatric syndromes as compared with 53.2% of those without cancer (P < .001). Those with cancer overall had a statistically significantly higher prevalence of hearing trouble, urinary incontinence, falls, depression, and osteoporosis than those without cancer. Adjusting for possible confounders, those with a history of cancer were more likely to experience depression (adjusted odds ratio [OR], 1.15; 95% CI, 1.02 to 1.30; P = .023), falls (adjusted OR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.04 to 1.32; P = .010), osteoporosis (adjusted OR, 1.21; 95% CI, 1.06 to 1.38; P = .004), hearing trouble (adjusted OR, 1.28; 95% CI, 1.08 to 1.52; P = .005), and urinary incontinence (adjusted OR, 1.42; 95% CI, 1.20 to 1.69; P < .001). Analysis of specific cancer subtypes showed that lung cancer was associated with vision, hearing, and eating trouble; prostate cancer was associated with incontinence and falls; cervical/uterine cancer was associated with falls and osteoporosis; and colon cancer was associated with depression and osteoporosis.

Conclusion

Elderly patients with cancer experience a higher prevalence of geriatric syndromes than those without cancer. Prospective studies that establish the causal relationships between cancer and geriatric syndromes are necessary.

INTRODUCTION

As the average age of the population continues to rise, we will see a dramatic increase in the numbers of elderly persons living with and surviving cancer. During the next 10 years, 70% of patients with cancer will be older than 65 years of age.1 The association of a cancer history with adverse health outcomes in the elderly population is important to assess to provide these patients with comprehensive care.

Geriatric syndromes are clinical conditions that are highly prevalent in older adults, especially in those who are vulnerable or frail, and cannot be attributed to a specific disease category. Tinetti et al2 have further defined geriatric syndromes as “accumulated effects of impairment” that make the elderly “vulnerable to situational challenges.” Common geriatric syndromes include vision and hearing problems, urinary incontinence, falls, depression, dementia, osteoporosis, and poor nutrition. Geriatric syndromes predict greater likelihood of hospitalization, increased costs of health care, and increased overall mortality.3–5 Although previous studies have illustrated the need for recognition of geriatric syndromes in patients with cancer,6,7 the independent association of a cancer history with specific geriatric syndromes has not yet been described.

In this study, we used information from the Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey (MCBS) to better elucidate the relationship between cancer and geriatric syndromes in elderly patients. Our research team previously described a high prevalence of vulnerability and frailty in elderly patients with cancer compared with those without cancer.8 This study extends our previous work by examining the independent association of cancer, and specific types of cancer, with the likelihood of having specific geriatric syndromes.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Data Source

The methods, including data source and study sample, used for this analysis are described in greater detail in our previous work.8 Our data were derived from the 2003 MCBS, a nationally representative and randomly sampled survey conducted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. The survey was performed using a computer-assisted interview with the beneficiary or a proxy (12% of collected interviews).9 Interview participants were encouraged to have the medical records of beneficiaries present to assist with accuracy. Information on beneficiary demographics, socioeconomic status, and indicators of health and functioning was retrieved from the Access to Care files collected in the initial fall interviews of beneficiaries.

Study Sample

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services obtained the sample of respondents from the Medicare enrollment file. The population older than age 85 years is oversampled. Aside from this exception, MCBS respondents were sampled from the Medicare enrollment file to be representative of the Medicare population by age group. A stratified multistage area probability sample design was used to select the sample, and response rates are consistently greater than 80%.9

We restricted the analysis to include only those participants who were community-based Medicare beneficiaries age 65 years or older (N = 12,480). Positive cancer history was found in 18.8% (n = 2,349) of these beneficiaries. History of cancer was considered positive if the patient responded yes to the following question: “Has a doctor ever told you that you had any kind of cancer, malignancy, or tumor other than skin cancer?”

Study Variables

Dependent variables were dichotomous, indicating either the presence or absence of eight common geriatric syndromes: vision problems, auditory problems, nutrition problems, incontinence, falls, memory problems, depression, and osteoporosis.4 Syndrome status was determined by patient responses to the MCBS interview. The definitions reflect the current literature on geriatric syndromes.4,6,7

Geriatric syndromes were captured within the MCBS as yes/no or ordinal responses (severity of symptom). For the ordinal variables, only respondents reporting the most severe symptoms known to be associated with adverse outcomes were included as having the syndromes.4,6,7,10 Individuals were classified as having sight problems if they responded that they either had “a lot of trouble seeing” or had “no usable vision.” Auditory trouble was defined as “a lot of trouble hearing” or “deaf.” Patients were considered to have nutrition problems if they reported having trouble eating solids. Incontinence was defined as having lost control of urine at least once or more per week in the past 12 months. The presence of a syndrome of falls was defined as at least one fall in the past 12 months. Respondents were considered to have dementia if their physicians told them that they had this diagnosis. Individuals were classified as having memory loss if they reported that memory loss interfered with daily activities. Dementia and memory loss were included as one variable. Patients classified as having depression reported feeling “sad, blue, or depressed” some, most, or all of the time. Osteoporosis was defined as having a recent history of hip fracture or a physician describing their bones as “soft or fragile.”

Independent Variables

Self-reported history of cancer and specific type of cancer were the main independent variables of interest. An “other” category was created, which included those cancers with small sample sizes and those the type of which was not specified by the respondent. Additional beneficiary-level covariates included age, sex, race/ethnicity, region, marital status, body mass index, income, insurance status, and education. Chronic medical conditions such as self-reported histories of heart disease, pulmonary disease, and neurologic diseases were also assessed similarly to other research using the MCBS.11,12 Although comorbidity severity was not available, the chronic diseases were selected because of their high prevalence in older adults and measurable impact on mortality and disability.13 Similar to previous research, comorbidity was included in the models as a categorical variable according to the number of comorbid conditions (0, 1, 2, > 3).6,8,13 Table 1 lists the variables included in the comorbidity count. Cancer was excluded from the comorbidity score.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Elderly Medicare Beneficiaries

| Characteristic | Cancer (n = 2,349) |

No Cancer (n = 10,131) |

P† | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %* | No. | %* | ||

| Age, years | < .001 | ||||

| Mean | 76.19 | 75.18 | |||

| 65-69 | 388 | 19.1 | 2,283 | 26.2 | |

| 70-74 | 484 | 25.2 | 2,235 | 25.9 | |

| 75-79 | 556 | 25.3 | 2,086 | 21.5 | |

| 80-84 | 528 | 18.2 | 1,932 | 15.0 | |

| ≥ 85 | 393 | 12.3 | 1,595 | 11.3 | |

| Sex | .8186 | ||||

| Male | 1,017 | 43.3 | 4,365 | 43.0 | |

| Female | 1,332 | 56.7 | 5,766 | 57.0 | |

| BMI (mean) | 26.74 | 26.65 | .6542 | ||

| Race | < .001 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 1,994 | 84.4 | 8,098 | 79.7 | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 162 | 7.4 | 799 | 7.9 | |

| Hispanic | 112 | 4.6 | 789 | 7.9 | |

| Other | 81 | 3.6 | 445 | 4.6 | |

| Marital status | .4025 | ||||

| Married | 1,269 | 56.3 | 5,356 | 55.3 | |

| Other | 1,080 | 43.7 | 4,775 | 44.7 | |

| Income, $ | .0834 | ||||

| < 25,000 | 1,331 | 54.7 | 6,023 | 56.9 | |

| 25,000-50,000 | 749 | 33.2 | 3,101 | 32.4 | |

| > 50,000 | 269 | 12.1 | 1,007 | 10.7 | |

| Education | < .001 | ||||

| < 9th grade | 297 | 11.5 | 1,631 | 14.8 | |

| 9th grade to high school diploma | 1,075 | 45.9 | 4,567 | 45.1 | |

| Some college | 514 | 22.5 | 2,094 | 21.0 | |

| Associate degree and above | 463 | 20.1 | 1,839 | 19.1 | |

| Comorbidity | |||||

| Hypertension | 1,485 | 63.0 | 6,044 | 58.5 | < .001 |

| Coronary artery disease | 539 | 22.0 | 2,132 | 19.92 | .0504 |

| Congestive heart failure | 226 | 8.7 | 711 | 6.3 | < .001 |

| Valvular heart disease | 245 | 9.9 | 934 | 8.8 | .0745 |

| Arrhythmia | 561 | 23.1 | 2,102 | 19.7 | < .001 |

| Other heart condition | 261 | 10.7 | 1,018 | 9.6 | .1415 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 334 | 13.8 | 1,327 | 12.3 | .0580 |

| Arthritis | 1,494 | 62.2 | 5,996 | 57.6 | < .001 |

| Mental disorder‡ | 358 | 15.6 | 1278 | 12.4 | < .001 |

| Parkinson's disease | 30 | 1.1 | 154 | 1.4 | .3103 |

| Emphysema/asthma/COPD | 399 | 16.7 | 1,376 | 13.4 | < .001 |

| Diabetes | 501 | 21.2 | 2000 | 19.8 | .2331 |

| No. of comorbidities | < .001 | ||||

| 0 | 164 | 7.4 | 1,034 | 11.1 | |

| 1 | 393 | 17.9 | 2,032 | 21.1 | |

| 2 | 566 | 24.2 | 2,342 | 23.2 | |

| ≥ 3 | 1,226 | 50.5 | 4,723 | 44.5 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Weighted prevalence.

χ2 tests.

Excluding depression.

Statistical Analysis

The goal of our analyses was to assess the independent association of a prior cancer diagnosis, and common cancer subtypes, with specific geriatric syndromes.

Baseline differences in demographics between the noncancer and cancer groups were evaluated using χ2 tests. We then compared the weighted prevalence of older patients with and without cancer reporting geriatric syndromes. Unadjusted differences in the prevalence of specific geriatric syndromes between those with and without a history of cancer were computed. We assessed the statistical significance of these differences using the χ2 test of proportions.

Multivariable logistic regressions were utilized to determine the independent association of a history of cancer with each geriatric syndrome. Each model controlled for age, body mass index, sex, race and ethnicity, region, education, marital status, insurance status, income, and comorbidity. Each geriatric syndrome was examined as an outcome in separate models. Separate models were generated that included only the cancer-specific subtypes. We also generated separate models that included comorbidity as a continuous variable and each comorbid condition to evaluate whether specific conditions (as listed in Table 1) confound the association between a cancer history and specific geriatric syndromes. Adjusted odds ratios and their 95% CIs indicate the independent association of each variable with the likelihood of the outcome, controlling for the effects of all other variables in the model. In addition, the odds ratio estimates were converted to relative risks to better capture the magnitude of the association between cancer and geriatric syndromes.14 We used the c-statistic, which makes use of receiver operator characteristic curve analysis, to evaluate the logistic regression models.

Because the MCBS uses a stratified multistage sampling scheme and oversamples certain population groups, each person has an unequal probability of being included in the survey. To obtain nationally representative population estimates, we conducted the analyses with SAS survey procedures (version 9.13; SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and used the MCBS cross-sectional weight to adjust for the complex multistage sample design and nonresponses. The institutional review board of the University of Rochester approved these analyses with exempt status.

RESULTS

A personal history of nonskin cancer was reported by 2,349 (18.8%) of the 12,480 respondents to the MCBS (noncancer group: n = 10,131). The weighted unadjusted demographics and clinical characteristics of the cancer and noncancer groups are listed in Table 1. Compared with those without a cancer history, respondents with a cancer history were statistically significantly older (P < .001), more likely to be non-Hispanic white (P < .001), and more likely to have higher education (P < .001). A statistically significantly higher proportion of patients with cancer had three or more comorbid conditions compared with those without a cancer history (P < .001). The most prevalent three cancer diagnoses among elderly patients with cancer were breast (4.72%), prostate (4.11%), and colon (2.43%) cancers (Table 2).

Table 2.

Cancer Prevalence and Population Estimates

| Cancer Site (n = 2,349) | No. | Prevalence |

US Population Estimate (millions)* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| %* | SE | |||

| Lung | 119 | 0.99 | 0.09 | 0.31 |

| Colon | 328 | 2.43 | 0.14 | 0.77 |

| Breast | 601 | 4.72 | 0.21 | 1.49 |

| Cervical/uterine | 273 | 2.17 | 0.14 | 0.68 |

| Prostate | 525 | 4.11 | 0.20 | 1.30 |

| Bladder | 121 | 0.91 | 0.10 | 0.29 |

| Ovarian | 84 | 0.68 | 0.07 | 0.21 |

| Other† | 604 | 4.84 | 0.23 | 1.53 |

| Total | 2,349 | 18.45 | 0.39 | 5.82 |

Prevalence and US population estimates are based on weighting algorithm provided by Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey.

Includes cancers with small sample size or no specification provided.

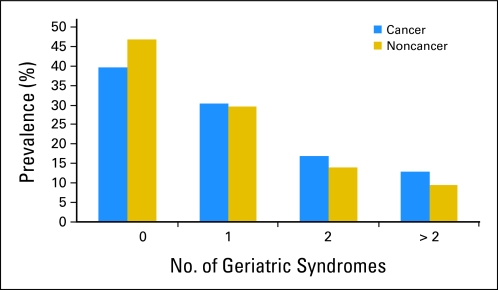

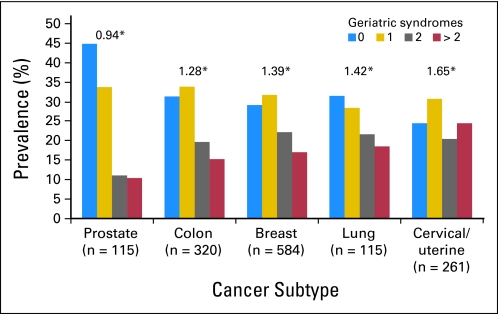

Figures 1 and 2 depict the proportions of patients with cancer with specific numbers of geriatric syndromes. The mean number of geriatric syndromes reported by beneficiaries with a cancer history was 1.16 compared with 0.98 for those without a cancer history (P < .001). Among those with cancer, 60.3% had a prevalence of one or more geriatric syndromes as compared with 53.2% of those without cancer (P < .001). The weighted prevalence of respondents with a cancer history reporting more than two geriatric syndromes was 12.9% compared with 9.6% of those without cancer. Geriatric syndromes were less frequently reported by among persons with prostate cancer and most prevalent among those with cervix/uterine cancer.

Fig 1.

Prevalence of geriatric syndromes (weighted prevalence, χ2 tests; P < .001).

Fig 2.

Prevalence of geriatric syndromes by cancer subtypes. (*) Mean number of geriatric syndromes.

In unadjusted analyses, the cancer group had a statistically significantly higher prevalence of five of eight geriatric syndromes: trouble hearing (cancer group, 7.81%; noncancer group, 6.05%; P < .001), incontinence (cancer group, 15.57%; noncancer group, 11.10%; P < .001), osteoporosis (cancer group, 24.33%; noncancer group, 19.84%; P < .001), depression (cancer group, 26.10%; noncancer group, 23.80%; P = .0157), and falls (cancer group, 26.37%; noncancer group, 21.91%; P < .001; Table 3).

Table 3.

Prevalence of Individual Geriatric Syndromes*

| Syndrome | Cancer (n = 2,349) |

No Cancer (n = 10,131) |

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Sight trouble | 187 | 7.37 | 706 | 6.17 | .0585 |

| Hearing trouble | 205 | 7.81 | 682 | 6.05 | < .001 |

| Eating problem | 277 | 11.24 | 1,102 | 10.38 | .1970 |

| Memory loss/dementia | 288 | 11.55 | 1,190 | 10.56 | .1773 |

| Incontinence | 375 | 15.57 | 1,220 | 11.10 | < .001 |

| Osteoporosis | 593 | 24.33 | 2,103 | 19.84 | < .001 |

| Depression | 614 | 26.10 | 2,481 | 23.80 | .039 |

| Falls | 643 | 26.37 | 2,318 | 21.91 | <.001 |

Weighted prevalence, χ2 tests.

We used multivariable regression analyses to evaluate the independent association of a cancer history with each of the eight geriatric syndromes (Table 4). The c-statistics for the models used to evaluate the association of overall cancer with each geriatric syndrome ranged from 0.628 to 0.768, indicating good model prediction of the dichotomous outcomes. After adjustment for known potential clinical and demographic confounders, a cancer diagnosis remained statistically significantly associated with depression, falls, osteoporosis, hearing trouble, and incontinence. Odds ratios ranged from 1.15 for depression to 1.42 for urinary incontinence. The associations identified between a cancer history and specific geriatric syndromes did not significantly change with different strategies of comorbidity adjustment.

Table 4.

Associations Between Cancer and Cancer Subtypes With Geriatric Syndromes Among Medicare Beneficiaries*

| Geriatric Syndrome | Cancer/Subtype | Adjusted OR* | 95% CI | P | Relative Risk | C-Statistics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence | Any cancer | 1.42 | 1.20 to 1.69 | < .001 | 1.36 | 0.720 |

| Prostate | 3.61 | 2.57 to 5.10 | .001 | 2.49 | 0.723 | |

| Other | 1.29 | 1.01 to 1.66 | .048 | 1.24 | 0.733 | |

| Trouble hearing | Any cancer | 1.28 | 1.08 to 1.52 | .005 | 1.26 | 0.704 |

| Lung | 2.01 | 1.05 to 3.87 | .043 | 1.81 | 0.710 | |

| Other | 1.50 | 1.09 to 2.05 | .012 | 1.45 | 0.707 | |

| Osteoporosis | Any cancer | 1.21 | 1.06 to 1.38 | .004 | 1.16 | 0.768 |

| Prostate | 0.66 | 0.44 to 1.00 | .047 | 0.67 | 0.767 | |

| Cervical/uterine | 1.47 | 1.09 to 1.97 | .012 | 1.24 | 0.761 | |

| Colon | 1.39 | 1.02 to 1.91 | .039 | 1.26 | 0.762 | |

| Depression | Any cancer | 1.15 | 1.02 to 1.30 | .023 | 1.12 | 0.655 |

| Colon | 1.44 | 1.09 to 1.90 | .010 | 1.28 | 0.656 | |

| Other | 1.28 | 1.05 to 1.57 | .014 | 1.19 | 0.656 | |

| Falls | Any cancer | 1.17 | 1.04 to 1.32 | .010 | 1.13 | 0.628 |

| Prostate | 1.25 | 1.01 to 1.57 | .049 | 1.18 | 0.630 | |

| Cervical/uterine | 1.46 | 1.10 to 1.92 | .008 | 1.27 | 0.629 | |

| Trouble eating | Any cancer | 1.12 | 0.97 to 1.29 | NS | 1.11 | 0.676 |

| Lung | 1.78 | 1.11 to 2.86 | .017 | 1.60 | 0.676 | |

| Prostate | 0.61 | 0.42 to 0.89 | .010 | 0.63 | 0.679 | |

| Other | 1.75 | 1.38 to 2.22 | .001 | 1.57 | 0.677 | |

| Trouble seeing | Any cancer | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.36 | NS | 1.10 | 0.713 |

| Lung | 2.01 | 1.05 to 3.87 | .036 | 1.81 | 0.724 | |

| Other | 1.51 | 1.06 to 2.14 | .022 | 1.44 | 0.721 | |

| Memory loss | Any cancer | 1.08 | 0.93 to 1.26 | NS | 1.07 | 0.712 |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; NS, not significant.

Analyses are weighted; controlled for age, body mass index, sex, race, ethnicity, region, insurance, education, income, and comorbidity. Results for cancer subtypes were generated in distinct models, with each geriatric syndrome as an outcome variable.

Table 4 summarizes the associations of individual cancer subtypes with each geriatric syndrome. A diagnosis of lung or “other” cancer subtype was independently associated with trouble seeing, trouble hearing, and difficulties with eating. A diagnosis of cervix/uterine or prostate cancer was associated with falls. A diagnosis of cervix/uterine or colon cancer was associated with osteoporosis. A diagnosis of colon or “other” cancer subtype was associated with depression. A diagnosis of prostate cancer was associated with lower odds of having trouble eating or being diagnosed, by patient report, with osteoporosis. Details on the full regression models are provided in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

DISCUSSION

In a nationally representative sample, older adults with a previous cancer diagnosis had a higher prevalence of geriatric syndromes than those without a previous cancer diagnosis. After adjustment for known potential clinical and demographic confounders, a cancer diagnosis remained statistically significantly associated with depression, falls, osteoporosis, hearing trouble, and incontinence. In our analyses, relative risk estimates show that a cancer diagnosis independently increased the probability of experiencing these outcomes compared with no cancer diagnosis by 13% to 36%, depending on the outcome. To our knowledge, this research is the first to establish that a history of cancer is independently associated with specific geriatric syndromes.

Geriatric syndromes represent common yet serious conditions for older persons and are associated with adverse outcomes and quality of life. The etiology of geriatric syndromes is typically multifactorial, and shared risk factors include older age, cognitive impairment, functional impairment, and impaired mobility.5 As a group, geriatric syndromes are known to increase risk for hospitalization and mortality, and each individual geriatric syndrome has been shown to increase risk for functional decline and death in older adults.5,10,15 This study reveals that older adults with a history of cancer have an even higher likelihood of having specific geriatric syndromes than those without a history of cancer, which may put them at a higher risk for further morbidity and mortality.

Geriatric syndromes often coexist with other diseases. Our study demonstrated that comorbidities and geriatric syndromes are more prevalent in patients with cancer than in those without cancer. An analysis from the Health and Retirement Study showed that two geriatric syndromes (falls and urinary incontinence) often co-occur with chronic conditions, such as heart disease and diabetes mellitus.16 Our study results showing that geriatric syndromes coexist with cancer are consistent with previous research.6,7,17,18 Koroukian et al6 found that a clinically significant geriatric syndrome was found in 35% of patients with newly diagnosed breast cancer, 45% of patients with colon cancer, and 51% of patients with prostate cancer within the Ohio Cancer Incidence Surveillance System. Flood et al7 showed that geriatric syndromes were highly prevalent in acutely ill hospitalized patients with cancer. In these studies, it is unclear whether a history of cancer or other comorbidities were associated with the increased prevalence of geriatric syndromes in older persons.

In our study, the prevalence of specific geriatric syndromes in older patients with cancer ranged from 7% for poor vision to more than 26% for depression and falls. Fifty percent of community-dwelling older adults in the Health and Retirement Study had one or more geriatric syndrome, which is comparable to the prevalence found in our noncancer group.19 Studies of screening for specific geriatric syndromes in elderly cancer cohorts have demonstrated a similarly high prevalence of these conditions. For example, the prevalence of depression in elderly patients with cancer ranges from 17% to 25%.20 The higher prevalence of geriatric syndromes in older patients with cancer could be a result of the interactions between symptoms of cancer, adverse effects of treatment, and underlying vulnerability. For example, older patients with prostate cancer receiving hormonal therapy have a high prevalence of physical performance problems, falls, and osteoporosis.18,21,22 More research is required to evaluate the impact of cancer symptoms and treatment complications on age-related conditions.

Because of the smaller sample size, associations between cancer subtypes and specific geriatric syndromes can be considered hypothesis generating and should be confirmed in further prospective research. These associations may be related to specific symptoms from cancer, stage of disease, or complications from treatment. Stage of cancer influences nutrition in older patients with cancer. Incontinence is a known adverse effect of prostate cancer treatment. Hearing difficulties in patients with lung cancer could be a result of cisplatin chemotherapy. Other relationships found may be related to interaction of aging and cancer, sex, or other underlying demographic factors. Older women with gynecologic cancers and patients with lung cancer had the highest numbers of geriatric syndromes, which may be related to length of survivorship or adverse health behaviors linked to the cancer diagnosis (eg, smoking, low physical activity). A diagnosis of prostate cancer seemed protective against osteoporosis, despite knowledge that hormonal therapy leads to osteoporosis. It may be that osteoporosis is under-recognized in this population, or patients with prostate cancer were not told or do not remember being told of this underlying condition.

There is little information at this time regarding the impact of geriatric syndromes on cancer decision making and outcomes. A study by Koroukian et al23 showed that presence of geriatric syndromes was associated with a lower likelihood of undergoing surgery and adjuvant chemotherapy. Individuals with two or more geriatric syndromes had an estimated disease-specific mortality and overall mortality more than double those of individuals with no geriatric syndromes. Currently, the presence or absence of geriatric syndromes is not currently captured within cancer clinical trials and not routinely captured within administrative datasets. Future research should incorporate assessment of geriatric syndromes prospectively to evaluate the relationships between these common but serious conditions and efficacy and toxicity of cancer treatment.

The presence of geriatric syndromes can be a clinical manifestation of vulnerability and frailty, which are now being recognized as important to assess in geriatric oncology patients.24–27 Our previous research found that a cancer history was independently associated with frailty, for the most part resulting from high prevalence of geriatric syndromes.8 A multidimensional comprehensive geriatric assessment includes a compilation of reliable and valid tools that can assess geriatric syndromes.15 According to National Cancer Comprehensive Network guidelines, a comprehensive geriatric assessment should be a key part of the treatment approach for vulnerable and frail older patients with cancer.24,25,28

There are limitations that should be considered when interpreting these findings. Our cancer sample was heterogeneous and included any persons with a reported diagnosis of cancer. We did not have information on date of diagnosis of cancer, cancer stage, or treatment. The sample thus likely included patients at all stages of disease, from long-term survivors to those receiving active treatment for metastatic disease. Because this is a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine causality in the associations of a cancer history with geriatric syndromes. Therefore, this study cannot determine whether the associations of cancer with specific geriatric outcomes are a function of survivorship (ie, previous cancer predisposes to geriatric syndromes later in life) or active ongoing treatment. Although the prevalence of geriatric syndromes was high, some syndromes like delirium, failure to thrive, and self neglect were not captured within the MCBS. Although we adjusted for comorbidity, there is still the possibility that an unmeasured effect of comorbid conditions has confounded our association between a cancer history and geriatric syndromes. Because we were restricted to the questions asked on the MCBS and self-reporting, our comorbidity and geriatric syndrome lists have not been previously validated. Self-reporting, however, has been shown to reliably identify comorbidity in other settings.29,30

Despite the above limitations, this study establishes the increased baseline prevalence of geriatric syndromes in elders with a history of cancer that have been associated with adverse health outcomes, such as mortality, in the more general geriatric population. These conditions are most prevalent in the older population and thus pose distinct challenges for clinicians caring for this population. Interventions that target geriatric syndromes in patients with cancer may help to improve quality of life and therapeutic outcomes. Care guidelines, rather than considering one condition at a time, should be developed to address comprehensive and coordinated management of co-occurring conditions such as cancer and geriatric syndromes.

Appendix

Table A1.

Association Between Cancer Diagnosis and Geriatric Syndromes Among Medicare Beneficiaries (N = 12,480)

| Factor | Trouble Seeing |

Trouble Hearing |

Trouble Eating |

Incontinence |

Falls |

Osteoporosis |

Memory Loss |

Depression |

||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Age, years | 1.06 | 1.05 to 1.08 | < .001 | 1.07 | 1.05 to 1.08 | < .001 | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | < .001 | 1.05 | 1.04 to 1.06 | < .001 | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | < .001 | 1.03 | 1.02 to 1.04 | < .001 | 1.07 | 1.06 to 1.08 | < .001 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.00 | .345 |

| BMI | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | .306 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 1.01 | .161 | 0.99 | 0.98 to 1.01 | .303 | 1.05 | 1.04 to 1.06 | < .001 | 1.02 | 1.01 to 1.03 | .001 | 0.96 | 0.94 to 0.97 | < .001 | 0.98 | 0.97 to 1.00 | .009 | 1.00 | 0.99 to 1.02 | .852 |

| Female | 1.16 | 0.97 to 1.40 | .107 | 0.49 | 0.41 to 0.59 | < .001 | 0.90 | 0.77 to 1.05 | .174 | 2.75 | 2.32 to 3.26 | < .001 | 1.12 | 1.00 to 1.03 | .042 | 8.28 | 7.27 to 9.42 | < .001 | 0.85 | 0.74 to 0.98 | .022 | 1.56 | 1.41 to 1.72 | < .001 |

| Race other than white | 0.83 | 0.61 to 1.12 | .224 | 0.70 | 0.52 to 0.97 | .029 | 1.52 | 1.22 to 1.90 | .002 | 0.86 | 0.68 to 1.07 | .172 | 0.60 | 0.51 to 0.71 | < .001 | 0.45 | 0.36 to 0.56 | < .001 | 1.00 | 0.81 to 1.22 | .973 | 0.85 | 0.73 to 1.00 | .054 |

| Hispanic | 0.94 | 0.56 to 1.56 | .804 | 1.84 | 0.81 to 4.24 | .147 | 1.32 | 0.88 to 1.97 | .183 | 0.76 | 0.51 to 1.15 | .192 | 0.93 | 0.62 to 1.40 | .742 | 0.52 | 0.31 to 0.87 | .013 | 1.53 | 0.99 to 2.37 | .056 | 0.99 | 0.74 to 1.34 | .961 |

| Region(reference, Northeast) | < .001 | .011 | < .001 | < .001 | .153 | .001 | < .001 | .293 | ||||||||||||||||

| Midwest | 1.55 | 1.19 to 2.02 | .001 | 1.04 | 0.79 to 1.38 | .770 | 1.18 | 0.92 to 1.51 | .198 | 1.77 | 1.36 to 2.32 | < .001 | 1.04 | 0.88 to 1.23 | .635 | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.07 | .214 | 1.25 | 1.00 to 1.56 | .055 | 1.03 | 0.86 to 1.23 | .769 |

| South | 1.69 | 1.30 to 2.19 | < .001 | 1.25 | 0.95 to 1.66 | .113 | 1.18 | 0.93 to 1.48 | .168 | 1.43 | 1.08 to 1.89 | .013 | 1.09 | 0.93 to 1.27 | .299 | 1.02 | 0.85 to 1.21 | .840 | 1.51 | 1.20 to 1.91 | .001 | 1.11 | 0.96 to 1.30 | .172 |

| West | 1.87 | 1.45 to 2.42 | < .001 | 1.51 | 1.15 to 1.98 | .003 | 1.69 | 1.34 to 2.14 | < .001 | 1.82 | 1.40 to 2.36 | < .001 | 1.22 | 1.03 to 1.44 | .019 | 0.91 | 0.73 to 1.13 | .397 | 1.69 | 1.35 to 2.11 | < .001 | 1.04 | 0.88 to 1.22 | .676 |

| Puerto Rico | 2.72 | 1.36 to 5.45 | .005 | 1.10 | 0.64 to 1.88 | .729 | 1.33 | 0.96 to 1.86 | .091 | 2.71 | 1.95 to 3.75 | < .001 | 1.02 | 0.81 to 1.29 | .849 | 1.53 | 1.17 to 2.00 | .002 | 1.89 | 1.34 to 2.65 | .001 | 1.42 | 0.98 to 2.05 | .065 |

| Nonmetropolitan | 0.84 | 0.69 to 1.03 | .101 | 1.23 | 1.02 to 1.51 | .032 | 1.01 | 0.83 to 1.23 | .914 | 1.11 | 0.91 to 1.35 | .310 | 1.15 | 1.00 to 1.31 | .048 | 0.97 | 0.83 to 1.12 | .667 | 1.09 | 0.88 to 1.36 | .424 | 0.98 | 0.84 to 1.14 | .784 |

| Medicaid | 1.52 | 1.19 to 1.94 | .004 | 1.51 | 1.13 to 2.03 | .015 | 1.94 | 1.57 to 2.40 | < .001 | 1.47 | 1.22 to 1.79 | < .001 | 1.31 | 1.10 to 1.55 | .006 | 0.89 | 0.73 to 1.09 | .270 | 1.68 | 1.36 to 2.07 | < .001 | 1.40 | 1.21 to 1.61 | < .001 |

| Education, years(reference, no school) | .010 | .012 | .002 | .001 | .070 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 0-8 | 0.85 | 0.49 to 1.45 | .545 | 1.19 | 0.66 to 2.15 | .561 | 0.76 | 0.53 to 1.09 | .138 | 0.89 | 0.59 to 1.34 | .574 | 0.91 | 0.61 to 1.37 | .657 | 2.26 | 1.36 to 3.75 | .002 | 0.73 | 0.50 to 1.07 | .101 | 0.90 | 0.63 to 1.30 | .577 |

| 9-12 | 0.61 | 0.34 to 1.10 | .098 | 1.00 | 0.54 to 1.84 | .996 | 0.55 | 0.38 to 0.81 | .003 | 0.65 | 0.42 to 1.03 | .065 | 0.82 | 0.53 to 1.25 | .351 | 2.55 | 1.53 to 4.23 | .001 | 0.46 | 0.31 to 0.67 | < .001 | 0.68 | 0.47 to 0.99 | .042 |

| 13-15 | 0.69 | 0.38 to 0.99 | .046 | 0.86 | 0.45 to 1.66 | .648 | 0.68 | 0.46 to 1.00 | .051 | 0.89 | 0.56 to 1.42 | .621 | 0.93 | 0.60 to 1.44 | .749 | 2.90 | 1.73 to 4.86 | < .001 | 0.49 | 0.33 to 0.75 | .001 | 0.59 | 0.41 to 0.85 | .004 |

| > 15 | 0.56 | 0.32 to 0.99 | .046 | 0.78 | 0.41 to 1.49 | .454 | 0.57 | 0.38 to 0.86 | .007 | 0.75 | 0.47 to 1.21 | .235 | 0.99 | 0.65 to 1.53 | .977 | 2.81 | 1.70 to 4.65 | < .001 | 0.47 | 0.30 to 0.71 | .001 | 0.53 | 0.37 to 0.77 | < .001 |

| Not married | 0.93 | 0.78 to 1.11 | .427 | 0.89 | 0.74 to 1.06 | .189 | 1.04 | 0.90 to 1.19 | .604 | 0.87 | 0.76 to 1.00 | .050 | 1.08 | 0.97 to 1.22 | .169 | 1.03 | 0.91 to 1.16 | .646 | 1.00 | 0.86 to 1.16 | .955 | 1.23 | 1.09 to 1.38 | < .001 |

| Income, $(reference,< 25,000) | .055 | .312 | < .001 | .215 | .543 | .657 | .227 | < .001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 25,000-50,000 | 0.82 | 0.67 to 1.01 | .066 | 0.90 | 0.74 to 1.09 | .272 | 0.72 | 0.61 to 0.84 | < .001 | 0.88 | 0.73 to 1.06 | .088 | 0.98 | 0.87 to 1.11 | .303 | 1.08 | 0.96 to 1.22 | .219 | 0.91 | 0.77 to 1.07 | .273 | 0.75 | 0.67 to 0.86 | < .001 |

| > 50,000 | 0.70 | 0.50 to 0.98 | .040 | 0.80 | 0.57 to 1.10 | .170 | 0.63 | 0.48 to 0.84 | .002 | 0.85 | 0.64 to 1.14 | .269 | 0.90 | 0.76 to 1.09 | .166 | 1.07 | 0.85 to 1.34 | .573 | 0.74 | 0.53 to 1.03 | .090 | 0.65 | 0.52 to 0.79 | < .001 |

| Cancer | 1.11 | 0.90 to 1.36 | .322 | 1.28 | 1.08 to 1.52 | .005 | 1.12 | 0.97 to 1.29 | .115 | 1.42 | 1.20 to 1.69 | < .001 | 1.17 | 1.04 to 1.32 | .010 | 1.21 | 1.06 to 1.38 | .004 | 1.08 | 0.93 to 1.26 | .313 | 1.15 | 1.02 to 1.30 | .023 |

| No. of comorbidities(reference, 0) | < .001 | .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||||||||

| 1 | 1.71 | 1.31 to 2.22 | < .001 | 1.19 | 0.88 to 1.61 | .253 | 1.01 | 0.83 to 1.23 | .923 | 1.44 | 1.15 to 1.80 | .016 | 1.20 | 1.02 to 1.40 | .027 | 1.12 | 0.96 to 1.32 | .160 | 1.10 | 0.86 to 1.39 | .446 | 1.07 | 0.91 to 1.22 | .391 |

| 2 | 2.00 | 1.49 to 2.68 | < .001 | 1.47 | 1.09 to 1.98 | .011 | 1.38 | 1.12 to 1.70 | .003 | 1.52 | 1.18 to 1.96 | < .001 | 1.45 | 1.24 to 1.69 | < .001 | 1.33 | 1.12 to 1.58 | .001 | 1.50 | 1.19 to 1.89 | .001 | 1.14 | 0.97 to 1.34 | .125 |

| > 2 | 3.77 | 2.88 to 4.94 | < .001 | 2.16 | 1.65 to 2.83 | < .001 | 1.91 | 1.56 to 2.33 | < .001 | 2.57 | 2.04 to 3.23 | < .001 | 2.11 | 1.83 to 2.44 | < .001 | 1.99 | 1.67 to 2.36 | < .001 | 2.45 | 2.01 to 2.98 | < .001 | 1.94 | 1.69 to 2.23 | < .001 |

| C-statistic | 0.713 | 0.704 | 0.676 | 0.720 | 0.628 | 0.768 | 0.712 | 0.655 | ||||||||||||||||

| Cancer subtype | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Breast | 1.04 | 0.72 to 1.51 | .840 | 1.32 | 0.92 to 1.91 | .137 | 0.90 | 0.65 to 1.23 | .497 | 1.10 | 0.82 to 1.48 | .906 | 1.22 | 0.98 to 1.51 | .071 | 1.12 | 0.92 to 1.37 | .262 | 1.07 | 0.79 to 1.43 | .677 | 1.01 | 0.81 to 1.25 | .827 |

| Lung | 2.01 | 1.05 to 3.87 | .036 | 2.01 | 1.02 to 3.96 | .043 | 1.78 | 1.11 to 2.86 | .017 | 1.47 | 0.76 to 2.84 | .256 | 1.18 | 0.73 to 1.92 | .501 | 1.11 | 0.65 to 1.91 | .694 | 1.13 | 0.64 to 2.01 | .676 | 1.49 | 0.94 to 2.36 | .088 |

| Prostate | 0.81 | 0.52 to 1.25 | .335 | 1.01 | 0.75 to 1.37 | .950 | 0.61 | 0.42 to 0.89 | .01 | 3.61 | 2.57 to 5.10 | < .001 | 1.25 | 1.01 to 1.57 | .049 | 0.66 | 0.44 to 1.00 | .047 | 1.08 | 0.80 to 1.47 | .615 | 1.11 | 0.84 to 1.46 | .489 |

| Cervical/uterine | 1.13 | 0.70 to 1.81 | .623 | 1.57 | 0.91 to 2.71 | .108 | 1.15 | 0.81 to 1.63 | .452 | 1.27 | 0.91 to 1.75 | .155 | 1.46 | 1.10 to 1.92 | .008 | 1.47 | 1.09 to 1.97 | .012 | 0.94 | 0.61 to 1.45 | .789 | 1.23 | 0.94 to 1.62 | .127 |

| Colon | 1.06 | 0.67 to 1.67 | .802 | 1.00 | 0.65 to 1.53 | .988 | 1.20 | 0.83 to 1.72 | .334 | 1.07 | 0.76 to 1.51 | .450 | 0.95 | 0.71 to 1.28 | .731 | 1.39 | 1.02 to 1.91 | .039 | 0.84 | 0.59 to 1.22 | .363 | 1.44 | 1.09 to 1.90 | .010 |

| Other | 1.51 | 1.06 to 2.14 | .022 | 1.50 | 1.09 to 2.05 | .012 | 1.75 | 1.38 to 2.22 | .001 | 1.29 | 1.01 to 1.66 | .048 | 1.09 | 0.86 to 1.36 | .485 | 1.18 | 0.94 to 1.48 | .148 | 1.21 | 0.93 to 1.58 | .153 | 1.28 | 1.05 to 1.57 | .014 |

NOTE. Association of covariates with each geriatric syndrome was derived from main model that included “cancer” as main variable. Cancer subtype was included in separate models that adjusted for each covariates noted in table.

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; BMI, body mass index.

Footnotes

Supported in part by a Hartford Health Outcomes Research Scholars Award and the University of Rochester Clinical and Translational Science Institute KL2 (S.G.M.) and by Grant No. 1K07CA120025 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD (K.M.).

Presented as part of Innovative Research in Aging and Cancer at the 45th Annual Meeting of the American Society of Clinical Oncology, May 29-June 2, 2009, Orlando, FL.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

The author(s) indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Supriya G. Mohile

Financial support: Supriya G. Mohile

Administrative support: Supriya G. Mohile

Provision of study materials or patients: Supriya G. Mohile

Collection and assembly of data: Supriya G. Mohile, Lin Fan

Data analysis and interpretation: Supriya G. Mohile, Lin Fan, Erin Reeve, Pascal Jean-Pierre, Karen Mustian, Luke Peppone, Michelle Janelsins, Gary Morrow, William Hall, William Dale

Manuscript writing: Supriya G. Mohile, Lin Fan, Erin Reeve, Pascal Jean-Pierre, Karen Mustian, Luke Peppone, Michelle Janelsins, Gary Morrow, William Hall, William Dale

Final approval of manuscript: Supriya G. Mohile, Lin Fan, Erin Reeve, Pascal Jean-Pierre, Karen Mustian, Luke Peppone, Michelle Janelsins, Gary Morrow, William Hall, William Dale

REFERENCES

- 1.Balducci L. Epidemiology of cancer and aging. J Oncol Manag. 2005;14:47–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tinetti ME, Inouye SK, Gill TM, et al. Shared risk factors for falls, incontinence, and functional dependence: Unifying the approach to geriatric syndromes. JAMA. 1995;273:1348–1353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fried LP, Bandeen-Roche K, Kasper JD, et al. Association of comorbidity with disability in older women: The Women's Health and Aging Study. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:27–37. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00124-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Naeim A, Reuben D. Geriatric syndromes and assessment in older cancer patients. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:1567–1577. 1580; discussion 1581, 1586, 1591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inouye SK, Studenski S, Tinetti ME, et al. Geriatric syndromes: Clinical, research, and policy implications of a core geriatric concept. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:780–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01156.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koroukian SM, Murray P, Madigan E. Comorbidity, disability, and geriatric syndromes in elderly cancer patients receiving home health care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2304–2310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flood KL, Carroll MB, Le CV, et al. Geriatric syndromes in elderly patients admitted to an oncology-acute care for elders unit. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2298–2303. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mohile SG, Xian Y, Dale W, et al. Association of a cancer diagnosis with vulnerability and frailty in older Medicare beneficiaries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1206–1215. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Medicare Current Beneficiary Survey, Access to Care 2003. http://www.cms.gov/mcbs.

- 10.Anpalahan M, Gibson SJ. Geriatric syndromes as predictors of adverse outcomes of hospitalization. Intern Med J. 2008;38:16–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2007.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Federman AD, Adams AS, Ross-Degnan D, et al. Supplemental insurance and use of effective cardiovascular drugs among elderly medicare beneficiaries with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2001;286:1732–1739. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.14.1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wolff JL, Boult C, Boyd C, et al. Newly reported chronic conditions and onset of functional dependency. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:851–855. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Boyd CM, Weiss CO, Halter J, et al. Framework for evaluating disease severity measures in older adults with comorbidity. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62:286–295. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. JAMA. 1998;280:1690–1691. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.19.1690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodin MB, Mohile SG. A practical approach to geriatric assessment in oncology. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1936–1944. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.2954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee PG, Cigolle C, Blaum C. The co-occurrence of chronic diseases and geriatric syndromes: The health and retirement study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:511–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02150.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stafford RS, Cyr PL. The impact of cancer on the physical function of the elderly and their utilization of health care. Cancer. 1997;80:1973–1980. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19971115)80:10<1973::aid-cncr15>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohile SG, Bylow K, Dale W, et al. A pilot study of the vulnerable elders survey-13 compared with the comprehensive geriatric assessment for identifying disability in older patients with prostate cancer who receive androgen ablation. Cancer. 2007;109:802–810. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cigolle CT, Langa KM, Kabeto MU, et al. Geriatric conditions and disability: The Health and Retirement Study. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147:156–164. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-3-200708070-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nelson CJ, Cho C, Berk AR, et al. Are gold standard depression measures appropriate for use in geriatric cancer patients? A systematic evaluation of self-report depression instruments used with geriatric, cancer, and geriatric cancer samples. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:348–356. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.23.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bylow K, Dale W, Mustian K, et al. Falls and physical performance deficits in older patients with prostate cancer undergoing androgen deprivation therapy. Urology. 2008;72:422–427. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2008.03.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alibhai SM, Breunis H, Timilshina N, et al. Impact of androgen deprivation therapy on physical function and quality of life in men with nonmetastatic prostate cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:5030–5037. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.8742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koroukian SM, Xu F, Bakaki PM, et al. Comorbidities, functional limitations, and geriatric syndromes in relation to treatment and survival patterns among elders with colorectal cancer. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2010;65:322–329. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Extermann M, Aapro M, Bernabei R, et al. Use of comprehensive geriatric assessment in older cancer patients: Recommendations from the task force on CGA of the International Society of Geriatric Oncology (SIOG) Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2005;55:241–252. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2005.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Balducci L, Cohen HJ, Engstrom PF, et al. Senior adult oncology clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2005;3:572–590. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2005.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of the frail person with advanced cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2000;33:143–148. doi: 10.1016/s1040-8428(99)00063-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saliba D, Elliott M, Rubenstein LZ, et al. The Vulnerable Elders Survey: A tool for identifying vulnerable older people in the community. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1691–1699. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Balducci L, Extermann M. Management of cancer in the older person: A practical approach. Oncologist. 2000;5:224–237. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-3-224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, et al. Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions: Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA. 1989;262:907–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chaudhry S, Jin L, Meltzer D. Use of a self-report-generated Charlson Comorbidity Index for predicting mortality. Med Care. 2005;43:607–615. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000163658.65008.ec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]