This study reviews a case of a large cystic anorectal teratoma successfully treated with a combined laparoscopic abdomino-paracoccygeal resection.

Keywords: Sacrococcygeal teratoma, Anorectal teratoma, Laparoscopic excision, Abdomino-paracoccygeal

Abstract

Sacrococcygeal teratoma rarely presents in adulthood (reported incidence of 1:87 000). It is more common in females. Adult anorectal teratoma is a rare variant of sacrococcygeal teratoma. The majority of tumors spare the sacrococcygeal bone. The size and location of the tumor within the pelvis dictates whether it is approached surgically through a transabdominal, posterior, or a combined approach. We present in this article the case of a young woman with a large cystic anorectal teratoma treated successfully with a combined laparoscopic abdomino-paracoccygeal resection.

INTRODUCTION

Teratoma is a germ cell tumor that presents in a cystic or solid form, with either benign or malignant histology. Extragonadal lesions can involve the sacrococcygeal, retroperitoneal, or mediastinal region.1 With recent advances in prenatal imaging, the majority of patients are diagnosed in the neonatal period, but some patients become symptomatic in adulthood. Most lesions are diagnosed incidentally on imaging. Anorectal teratoma is a rare variant of sacrococcygeal teratoma and typically spares the coccyx and sacral bones.1–3 Clinical diagnosis may be delayed due to the relative rarity of this condition and the vagueness of the symptoms. Various surgical techniques have been used in the past to excise these rare tumors. The abdominal, posterior (perineal, para-anal, transsacral, transcoccygeal, paracoccygeal), or combined abdominal and posterior approaches are required, depending on the location of the lesion. Traditionally, these techniques have been used in an open fashion with a paucity of data on minimally invasive approaches. This report describes the case of an adult woman with a large cystic anorectal teratoma treated successfully by a combined laparoscopic abdomino-paracoccygeal resection.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old woman was referred for evaluation of a pelvic cystic mass. At age 11, the patient had transanal drainage of a presumed presacral abscess. She did well until age 24 when she presented with right-sided pelvic pain radiating down her lower extremities. An extensive workup was performed including colonoscopy, barium enema, computed tomography (CT) of the abdominopelvic cavity, CT myelogram, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the pelvis and lumbosacral spine. A large cystic mass with an air-fluid level was noted in the presacral area and occupied the width of the pelvis displacing the rectum and uterus anteriorly (Figure 1). The superior aspect of the mass was just caudal to the sacral promontory, and its inferior margin extended down to the anorectal region. Barium enema demonstrated a fistulous communication between the posterior aspect of the anorectal junction and the mass. MRI and CT myelogram did not reveal a communication with the spine. Colonoscopy showed extrinsic compression of the rectum without any intraluminal abnormality. Over the ensuing 2 years, the patient was evaluated by various specialists at outside hospitals, including gynecologic, neurosurgical, and colorectal surgery specialists. She received various recommendations including observation, transanal drainage, percutaneous drainage, and excision of the mass. She remained symptomatic with pain and intermittent fever and chills for which she received pain medication and antibiotics. Eventually, she was referred to our tertiary center for a higher level of care. The patient was advised to undergo a combined abdominal and posterior resection of the tumor because of her symptoms. A mechanical bowel preparation was administered the day before surgery.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography demonstrates the presacral mass (large arrow) with air-fluid level displacing rectum and uterus anteriorly.

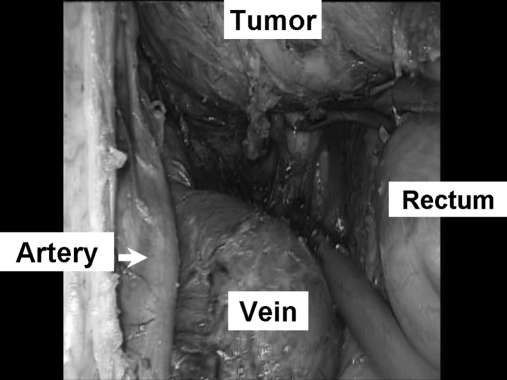

The operation was conducted with the patient in the lithotomy position. The peritoneal cavity was insufflated through an 11-mm supraumbilical trocar. Three 11-mm trocars were placed in the right mid, right lower, and left lower abdomen. A bulky uterus was suspended to the anterior abdominal wall by using a 3.0 Nylon suture. The rectum was mobilized off the presacral tumor by carrying the dissection posterior to the mesorectal envelop. The dissection was initiated from the left lateral side initially and completed from the right side. Once the presacral tumor was exposed, it was carefully lifted off the sacral area. The left common iliac artery, vein, hypogastric nerve trunk, and left ureter were visually identified and kept out of harm's way (Figure 2). The transabdominal dissection was carried all the way down to the pelvic floor completely freeing the mass from surrounding structures, except the anorectal junction. A 19 French Blake drain was placed in the presacral area through the right lower quadrant trocar. All trocars were removed and wounds closed. The patient was repositioned into the prone jackknife position. A transverse incision was made over the anococcygeal ligament, just inferior to the coccyx. The anococcygeal ligament was divided along with a portion of the posterior levator muscles. The presacral space was entered to join the abdominal dissection. The mass was freed from its remaining rectal, vaginal, and pelvic floor attachments. The coccyx was left in situ. The fistulous communication site was identified and excised with the mass (Figure 3). The defect in the rectal wall was closed with absorbable interrupted sutures. The wound was submerged with saline, and the rectum was insufflated transanally without evidence of air leak. The wound was closed in multiple layers with absorbable sutures. Histologic evaluation revealed a benign cystic teratoma lined by squamous and columnar epithelium with some nerve tissue and serous glands.

Figure 2.

Intraoperative laparoscopic view of the presacral mass separated from rectum and dissected off the left common iliac artery and vein.

Figure 3.

Gross specimen of the cystic teratoma.

The patient had an uneventful recovery. Two months postoperatively, she became pregnant, carried her pregnancy to full term, and delivered a healthy infant through a Cesarian delivery. She remains well one year following her pelvic operation.

DISCUSSION

Sacrococcygeal teratomas occur of 1 in 30 000 to 1 in 40 000 live births4 and 1 in 87 000 adults with a 10:1 female predominance.1,5–9 Anorectal teratomas are a rare variant of sacrococcygeal teratomas and are usually located in the retrorectal space without involvement of the sacrococcygeal bone.1–3 They arise embryologically from multipotent cells in Hensen's node and enlarge within the rectal wall. Cases involving the rectal lumen and presenting as intraluminal polypoid lesions have been previously reported.10,11 Histologically, anorectal teratomas are similar to sacrococcygeal teratomas, being comprised of tissue from all 3 embryonic germ layers. They are classified into 1 of 3 groups: (1) benign, containing well-differentiated tissue; (2) immature, without malignant features; and (3) malignant. Benign teratomas are more likely to be cystic, while malignant teratomas tend to be solid. Malignancy usually arises from a single germ line and generally from embryonic tissue. Most sacrococcygeal teratomas presenting in adulthood are often benign and felt to have been undiagnosed since infancy. When diagnosed, patients with presacral tumors are often advised to undergo excision either because of the presence of symptoms or due to the risk of malignancy. Drainage of a symptomatic cystic mass is not curative. Biopsy or aspiration of the lesion is rarely helpful in making a diagnosis. Seeding of the biopsy tract is a risk in case of malignancy. Unlike teratomas diagnosed in infancy, which can be externally visible, adult teratomas are often intrapelvic and not appreciated externally.5 The most common presentation of an adult with anorectal teratoma is a palpable posterior rectal mass found incidentally on digital examination.12 Symptomatic patients can present with a chronically draining fistula, rectal pain, tenesmus, or change in bowel habits, such as diarrhea or constipation. The patient reported in this report presented initially with symptoms during her adolescence. She subsequently developed recurrent symptoms as an adult. It is unclear whether the anorectal fistula was related to the teratoma or as a result of the prior transanal drainage. Cross-sectional imaging with CT, MRI, or both CT and MRI, is helpful in making the diagnosis to differentiate teratoma from other conditions such an anterior meningocele. Cross-sectional imaging provides information on the size, location, extent of the tumor, and invasion if present.13,14 When surgical excision is undertaken, complete excision of the tumor is advisable to minimize recurrence. Excision of the coccyx and a portion of the sacrum is needed when bony involvement is present. The tumor size and anatomical location dictate the type of surgical approach.12,14–17 An anterior abdominal approach is typically used for high lesions without sacral involvement and provides improved visualization of the ureters, rectum, and iliac vessels, and provides good exposure for complete eradication of the tumor. A posterior approach is preferred for small tumors located in the lower portion of the pelvis. Larger tumors often require a combined approach to access both the upper and lower pelvis. Traditionally, the abdomen is accessed through a midline open incision. Recent reports have documented that some presacral tumors diagnosed in infancy or adolescence can be safely excised laparoscopically.7,18,19 To date, 3 adult patients with presacral tumors have been successfully treated laparoscopically.6,8,9 with one approached via a combined laparoscopic abdominal and perineal dissection.9 Despite the limited amount of data, it is clear that some patients with presacral tumors can be approached laparoscopically. This article supports that idea that a combined laparoscopic abdominal-paracoccygeal approach is technically feasible and safe.

CONCLUSION

Anorectal teratoma is a rare variant of sacrococcygeal teratoma and affects females more frequently than males. The size and location of the tumor within the pelvis dictates whether it is approached surgically through a transabdominal, posterior, or combined approach. Our case illustrates that when a transabdominal approach is necessary it can be safely and successfully done laparoscopically, even for a large lesion. Such an approach can offer the patient all the potential benefits of minimally invasive surgery.

References:

- 1. Chwalinski M, Nowacki MP, Nasierowska-Guttmejer A. Anorectal teratoma in an adult woman. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2001;16(6):398–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Jona JZ. Congenital anorectal teratoma: report of a case. J Pediatr Surg. 1996;31(5):709–710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Russell P. Carcinoma complicating a benign teratoma of the rectum: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1973;17:550–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Head HD, Gerstein JD, Muir RW. Presacral teratoma in the adult. Am Surg. 1975;41(4):240–248 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Miles RM, Stewart GS. Sacrococcygeal teratomas in adult. Ann Surg. 1974;179(5):676–683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cho SH, Hong SC, Lee JH, et al. Total laparoscopic resection of primary large retroperitoneal teratoma resembling an ovarian tumor in an adult. J Minim Invas Gyn. 2008;15(3):384–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y, Xu H, Li Y, et al. Laparoscopic resection of presacral teratomas. J Minim Invas Gyn. 2008;15(5):649–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Takeda A, Manabe S, Hosono S, Nakamu H. A case of a mature cystic teratoma of the uterosacral ligament successfully treated by laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Invas Gyn. 2005;12(1):34–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Senthilkumar R, Madankumar MV, Annapoorni S. Laparoscopic and perineal excision of an infected “dumb-bell” shaped retrorectal epidermoid cyst. J Laparoendosc Adv S. 2008;18(1):88–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Green JB, Timmcke AE, Mitchell WT. Endoscopic resection of primary rectal teratoma. Am J Surg. 1993;59:270–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Takayo Y, Shimamoto C, Hazama K, et al. Primary rectal teratoma: EUS features and review of the literature. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;51:353–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jao SW, Beart RW, Spencer RJ, et al. Retrorectal tumors. Mayo Clinic experience, 1960-1979. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(9):644–652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Johnson AR, Ros RR, Hjermstad MM. Tailgut cyst: diagnosis with CT and sonography. AJR. 1986;147(6):1309–1311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Bohm B, Milsom JW, Fazio VW, et al. Our approach to the management of congenital presacral tumors in adults. Int J Colorectal Dis. 1993;8(3):134–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Localio SA, Eng K, Ranson JH. Abdominosacral approach for retrorectal tumors. Ann Surg. 1980;191(5):555–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Abel ME, Nelson R, Prasad ML, et al. Parasacrococcygeal approach for the resection of retrorectal developmental cysts. Dis Colon Rectum. 1985;28(11):855–858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Stewart RJ, Humphreys WG, Parks TJ. The presentation and management of presacral tumours. Br J Surg. 1986;73(2):153–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee KH, Tam YH, Chan KW, Cheung S, Sihoe J, Yeung CK. Laparoscopic-assisted excision of sacrococcygeal teratoma in children. J Laparoendosc Adv S. 2008;18(2):296–301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bax NM, van der Zee DC. The laparoscopic approach to sacrococcygeal teratomas. Surg Endosc. 2004;18(1):128–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]