The authors report on 2 patients who had small bowel obstruction secondary to phytobezoars following Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.

Keywords: Phytobezoar, Gastric bypass

Abstract

Bowel obstruction is a known complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. It can be caused by adhesions, internal hernia, incarcerated ventral hernia, or intussusception. Sometimes the underlying cause may be unusual. These 2 case reports describe patients who underwent laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and whose postoperative courses were complicated by small-bowel obstruction due to phytobezoars in the ileum, distal to the jejunojejunal anastomosis. We reviewed the literature by using PubMed and Medline for causes, pathogenesis, classifications, diagnosis, and management.

INTRODUCTION

With the increasing frequency of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), we expect to be called upon more often to deal with the complications of this procedures. One of the most common presenting symptoms of a delayed postoperative complication of RYGB is epigastric, colicky abdominal pain. Bowel obstruction should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. Bezoars are one of the unusual underlying causes of bowel obstruction after bypass surgery. They can be classified according to their origins as phytobezoar (undigested fruit or vegetable fibers), trichobezoar (hair), lactobezoar (undigested milk), pharmacobezoar (medications), or miscellaneous.

Phytobezoars are the most common form.1 We present 2 cases of phytobezoars complicating laparoscopic gastric bypass. Phytobezoar formation after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass is a previously mentioned complication.2 It has been previously described in the gastric pouch2,3 at the gastrojejunostomy site2 due to a permanent suture that eroded into the lumen at the level of the anastomosis.4 Phytobezoars were also seen in the proximal pouch after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding.5

Phytobezoars represent the most common foreign bodies of the gastrointestinal tract. More than one-half of the patients who develop phytobezoars (57%) had previous gastric surgery. Small-bowel obstruction is usually the most common complication.6

CASE REPORT ONE

A 57-year-old man with a history of morbid obesity, BMI of 44, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea, and ventral hernia due to previous open cholecystectomy underwent laparoscopic gastric bypass 2 years prior to presentation. His surgery was complicated by a small-bowel obstruction 1 year later that was managed by laparoscopic enterolysis and repair of the incisional hernia with mesh. Six months later, he underwent laparoscopic incisional hernia repair due to recurrence of his hernia. On this presentation, he came to the emergency room with a 1-day history of abdominal pain accompanied by nausea and multiple episodes of bilious vomiting. His pain was in the periumbilical area, nonradiating, 7/10 in severity. His abdomen was soft, not distended, with epigastric and periumbilical tenderness and high-pitched bowel sounds. CT scan of the abdomen showed dilatation of the gastric pouch and the remnant stomach, multiple dilated jejunal loops with air fluid levels, and a mottled intraluminal mass in the ileal lumen. The distal ileum and colon appeared decompressed. The patient was taken to the operating room where he underwent exploratory laparotomy. A clear transition point was identified in the proximal ileum. On exploration, all the anastomoses were found to be patent. Inspection of the dilated segment revealed impacted intraluminal contents from the point of obstruction proximally to the previously created jejunojejunostomy. A longitudinal enterotomy was made over the point of obstruction, and a copious amount of solidified food contents (phytobezoar) with peanut shells was evacuated. The surgical enterotomy was then closed in a transverse fashion. The patient tolerated the procedure well and had an uncomplicated postoperative recovery. He tolerated food on his second postoperative day and was discharged home 5 days after surgery.

CASE REPORT TWO

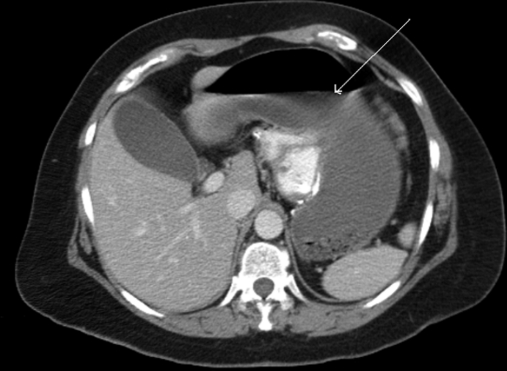

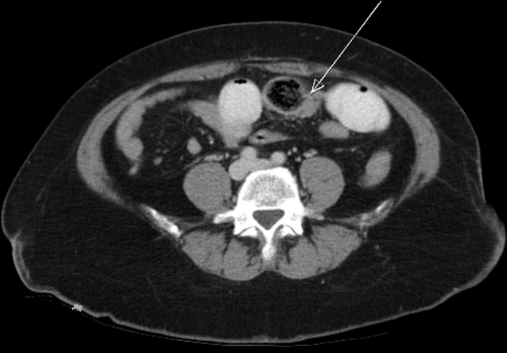

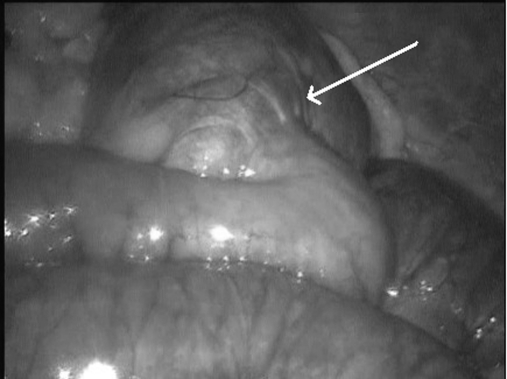

A 46-year-old woman with a past medical history of hypertension and morbid obesity who underwent laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass 3 years prior to the emergency room presentation came in with moderate to severe abdominal pain primarily in the epigastric region, associated with several episodes of bilious vomiting. She did not have fever, chills, or diarrhea. Her last bowel movement was one day before presentation. An abdominal CT scan showed obstruction in the distal jejunum/proximal ileum with a clear transitional point and short intraluminal mottled mass, in addition to dilatation of the Roux loop and gastric pouch (Figure 1). She was taken to the operating room for laparoscopic exploration. The stomach was noted to be distended along with the jejunal loops including the jejunojejunostomy. A solid obstructing intraluminal mass was found 80cm from the jejunojejunal anastomosis with collapsed bowel distal to it. A longitudinal enterotomy was performed. The bezoar, which consisted of partially digested vegetable matter and meat fibers, was then gently milked out of the small-bowel lumen (Figure 2). The enterotomy was then closed transversely in 2 layers (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Computed tomographic scan of the abdomen. Arrow pointing to the intraluminal mottled mass. Also seen dilated and collapsed small bowel loops.

Figure 2.

Laparoscopic extraction of phytobezoar. One arrow points to the phytobezoar after removal from the lumen. One arrow points to the enterotomy site.

Figure 3.

Laparoscopic closure of the enterotomy site in 2 layers.

Upon inspection, all the anastomoses from the previous bypass surgery were patent. The patient tolerated the procedure well without complications. She tolerated food on postoperative day one, and she was discharged home on the third day after surgery. The patient is currently being followed at the clinic with no complaints and continuous dietary counseling.

DISCUSSION

Several articles have described small-bowel obstruction after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass both as early and late complications. Small-bowel obstruction after gastric bypass can be caused by adhesions, internal hernia, incarcerated ventral hernia, or intussusception7; phytobezoar is one of the unusual underlying causes. The properties of the ingested materials and the degree of gastric dysfunction are the major contributors to the formation of phytobezoars.8 They can be composed of indigestible vegetable material, hair, or more unusual materials, and they can be classified according to their composition.9,10

In the literature, there are many theories about the pathogenesis of phytobezoar. After gastric surgery, it can be due to delayed gastric emptying that results in alterations in acid and mucus secretions. Accelerated gastric emptying can also predispose one to phytobezoars, because it allows the passage of large-diameter solid matter from the stomach into the small intestine. Vagotomy can decrease gastric acid secretions, leading to more viscous stomach contents that can result in gastric or intestinal phytobezoars. In addition, it can happen because of insufficient mastication when the patient is unable to chew properly. Dietary factors include an excessive consumption of persimmons, mangos, bananas, oranges, coconuts, cherries, tomatoes, and other foods. Also they can be caused by degenerative motor complex neuropathy, such as in diabetes. Phytobezoars can also occur in cases of anastomotic stricture after gastric and bowel surgery.2,13,15

The diagnosis is often made as an incidental finding during gastroscopy or exploration.2 Both of our patients were diagnosed with bowel obstruction on CT scan, but the definitive diagnosis of phytobezoar was made during exploration. Some articles suggest CT imaging is a useful method for making the diagnosis of bezoar associated with small-bowel obstruction.11 Zissin et al,12 upon reviewing CT scan findings in 6 patients with intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoar, found an ovoid intraluminal mass of a mottled appearance, at the transition zone between dilated and collapsed small-bowel loops. These were the CT findings in both of our patients. A high index of suspicion is needed for the diagnosis of phytobezoar-induced bowel obstruction in gastric bypass patients.

Because of the change in GI anatomy, these patients may not present with typical signs and symptoms of bowel obstruction. Upper GI series, CT scan, and diagnostic laparoscopy should be used liberally in diagnosis and management. Epidemiological data show that 2% to 3% of small-bowel obstructions are caused by phytobezoars.13 The removal of the phytobezoar does not alleviate the underlying problem. The reported recurrence rate for gastric bezoar is 14%.14 A number of surgical, endoscopic, and pharmacologic treatments for bezoars have been proposed with differing results.15 Many articles report gastric phytobezoar removal by the endoscopic technique.16 Our patients had jejunal/ileal phytobezoars that were not amenable to endoscopic intervention. Surgical management of small-bowel bezoars include fragmentation and flushing into the cecum, enterotomy, and removal of the bezoars. Bowel resection is rarely indicated and should be reserved for cases of intestinal necrosis or if the bezoar is intimately encrusted to the intestinal wall.13

In our 2 cases, we opened the small bowel. The enterotomy was closed transversely. Resection was not necessary because the bowel segment was viable without signs of necrosis. Various studies have reported laparoscopic management of intestinal obstructions with the improvement of laparoscopic skills.15 However, gentle manipulation of the intestines should be done to avoid damage to the distended bowel. There is also an increased risk of intestinal injury caused by the trocars. The open technique to place the first port is recommended over the Veress needle technique for all patients with intestinal obstruction.17 In our first patient, a laparoscopic approach was attempted, but because of the massive adhesions from previous surgeries, we converted to laparotomy. In the second patient, the laparoscopic approach was a feasible method for the management of her bezoar-induced intestinal obstruction.

Nutritional counseling in the postoperative care of gastric bypass patients is very crucial to prevent serious complications that may arise from dietary indiscretions. Patients should be encouraged to increase the intake of fluids and to chew food carefully. Psychiatric evaluation should also be considered.3 Surgical techniques that may prevent phytobezoar formation include the use of absorbable sutures for creating the anastomosis and reducing tension and ischemia at the anastomosis sites.2

CONCLUSION

Bezoar-induced small-bowel obstruction after laparoscopic gastric bypass is uncommon and remains a diagnostic and management dilemma. However, it should always be suspected in patients after gastric bypass, because they are considered high-risk patients due to the previous gastric surgery and their nutritional habits. Early diagnosis and surgical exploration in suspected cases is the key to a successful outcome. In select patients, the laparoscopic approach is a feasible method in the management of bezoar-induced intestinal obstruction when performed by an experienced laparoscopic surgeon. Phytobezoars may be avoided by proper surgical technique and adequate nutritional counseling.

References:

- 1. Teicher EJ, Cesanek PB, Dangleben D. Small-bowel obstruction caused by phytobezoar. Am Surg. 2008;74(2):136–137 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Pinto D, Carrodeguas L, Soto F, et al. Gastric bezoar after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2006;16(3):365–368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ionescu AM, Rogers AM, Pauli EM, Shope TR. An unusual suspect: coconut bezoar after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2008;18(6):756–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Pratt JS, Van Noord M, Christison-Lagay E. The tethered bezoar as a delayed complication of laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a case report. J Gastrointest Surg. 2007;11(5):690–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Parameswaran R, Ferrando J, Sigurdsson A. Gastric bezoar complicating laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding with band slippage. Obes Surg. 2006;16(12):1683–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Koulas SG, Zikos N, Charalampous C, Christodoulou K, Sakkas L, Katsamakis N. Management of gastrointestinal bezoars: an analysis of 23 cases. Int Surg. 2008;93(2):95–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rogula T, Yenumula PR, Schauer PR. A complication of Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: intestinal obstruction. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(11):1914–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Robles R, Parrilla C, Escamilla J, et al. Gastrointestinal bezoars. Br J Surg 1994;81:1000–1001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. White NB, Gibbs KE, Goodwin A, et al. Gastric bezoar complicating laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, and review of literature. Obes Surg 2003;13:948–950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kamal I, Thomson J, Paquette DM. The hazards of vinyl glove ingestion in the mentally retarded patient with pica: new implications for surgical management. Can J Surg 1999;42:201–204 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ulusan S, Koc Z, Torer N. Small bowel obstructions secondary to bezoars. Ulus Travma Acil Cerrahi Derg. 2007;13(3):217–221 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Zissin R, Osadchy A, Gutman V, Rathaus V, Shapiro-Feinberg M, Gayer G. CT findings in patients with small bowel obstruction due to phytobezoar. Emerg Radiol. 2004;10(4):197–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bedioui H, Daghfous A, Ayadi M, et al. A report of 15 cases of small-bowel obstruction secondary to phytobezoars: predisposing factors and diagnostic difficulties. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 2008; 32 (6-7): 596–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Krausz MM, Moriel EZ, Ayalon A, et al. Surgical aspects of gastrointestinal phytobezoar treatment. Am J Surg. 1986;152:526–530 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. De Menezes Ettinger JE, Silva Reis JM, de Souza EL, et al. Laparoscopic management of intestinal obstruction due to phytobezoar. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg. 2007;11(1):168–171 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Blam ME, Lichtenstein GR. A new endoscopic technique for the removal of gastric phytobezoars. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:404–408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Ganpathi IS, Cheah WK. Laparoscopic-assisted management of small bowel Obstruction Due to Phytobezoar. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2005;15:30–32 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]