Abstract

Activation of the MYC oncoprotein is among the most ubiquitous events in human cancer. MYC functions in part as a sequence-specific regulator of transcription. Although early searches for direct downstream target genes that explain MYC’s potent biological activity were met with enthusiasm, the postgenomic decade has brought the realization that MYC regulates the transcription of not just a manageably small handful of target genes but instead up to 15% of all active loci. As the dust has begun to settle, two important concepts have emerged that reignite hope that understanding MYC’s downstream targets might still prove valuable for defining critical nodes for therapeutic intervention in cancer patients. First, it is now clear that MYC target genes are not a random sampling of the cellular transcriptome but instead fall into specific, critical biochemical pathways such as metabolism, chromatin structure, and protein translation. In retrospect, we should not have been surprised to discover that MYC rewires cell physiology in a manner designed to provide the tumor cell with greater biosynthetic properties. However, the specific details that have emerged from these studies are likely to guide the development of new clinical tools and strategies. This raises the second concept that instills renewed optimism regarding MYC target genes. It is now clear that not all MYC target genes are of equal functional relevance. Thus, it may be possible to discern, from among the thousands of potential MYC target genes, those whose inhibition will truly debilitate the tumor cell. In short, targeting the targets may ultimately be a realistic approach after all.

Keywords: MYC, metabolism, chromatin, CAD, pyrimidine, target genes

Introduction

As discussed elsewhere in this issue, the myc oncogene was originally discovered as the cellular homolog of the transforming gene from an avian retrovirus.1-3 Not long thereafter, myc was found to be translocated from 8q24 to one of the immunoglobulin gene loci, in 100% of Burkitt’s lymphoma cases.4 Identical translocation events are common in AIDS-related lymphomas.5-7 Subsequently, studies showed that more common types of human cancer, such as those of the lung, breast, ovary, and prostate, had amplification of the myc gene, often to a level of 100 copies per cell.8-13 A third mechanism of myc overexpression in human cancer was defined when it was shown that mutations in the wnt signaling pathway lead to increased transcription of myc.14 Whether by translocation, amplification, or wnt/APC/β-catenin pathway mutation, nearly all forms of human cancer overexpress some member of the myc family, which includes two other oncoproteins in humans, L-MYC and N-MYC.15-18 These proteins are primarily overexpressed in small cell lung cancer and neuroblastoma, respectively. Both in vitro and in vivo evidence conclusively demonstrates that myc overexpression confers a major proliferative advantage on tumor cells,19,20 and estimates suggest that MYC overexpression contributes to as many as 70% of human tumors.21,22

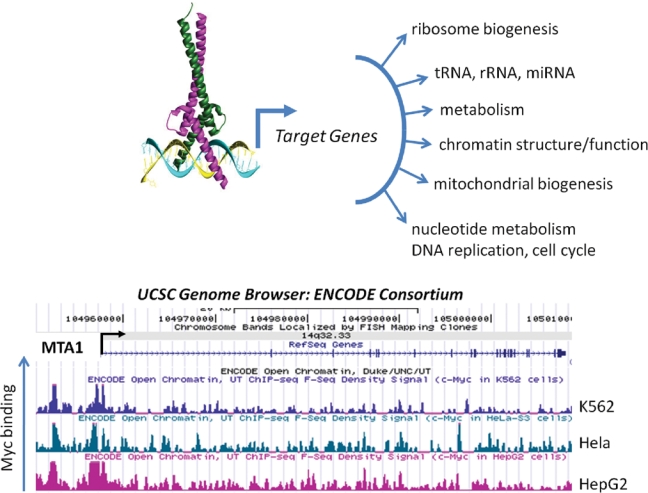

Shortly after its discovery, the MYC protein was shown to be primarily localized to the nucleus, and a role in regulating gene transcription was suspected.23,24 Over the next decade, it was found that MYC is a sequence-specific transcription factor, which binds DNA only when dimerized with its obligate partner MAX.25-28 For both MYC and MAX, DNA binding is mediated by a region rich in basic amino acids, and dimerization is mediated by adjacent helix-loop-helix (HLH) and leucine zipper (LZ) motifs in the carboxy terminus. MYC/MAX dimers bind with highest affinity to the subset of E-boxes containing the sequence CACGTG (Fig. 1).29,30 The amino terminus of MYC comprises a loosely defined transactivation domain, whereas MAX lacks a transactivation domain.31 Within the MYC transactivation domain are several motifs that may provide generic transactivation potential. These motifs include an acidic “blob,” a glutamine-rich region, and a poly-proline domain. Somewhat surprisingly, these motifs are not essential to MYC’s ability to transform mammalian cells.32,33 In contrast, another amino terminal motif in MYC, termed MbII (amino acids 129-145), is strictly required for transformation and most other known functions of MYC (i.e., apoptosis, Sphase induction, blocking differentiation, etc.). MbII is one of several domains that have been conserved in the amino terminus of MYC family proteins throughout evolution.34 Although MbII bears no homology to known transactivation motifs, it is critical for MYC function at least in part because it mediates recruitment of several cofactor complexes.35-39 These cofactors function to regulate the chromatin configuration at MYC target gene loci. Very recent studies suggest that MYC plays a significant role in regulating the release of paused RNA PolII molecules at many target genes.40 Evidence for this model had actually been generated many years prior by empirical studies at the target gene CAD.41,42 So, although MYC clearly plays nontranscriptional roles in the cell, as discussed elsewhere in this issue, much of its function appears to rely on its role as a sequence-specific, DNA binding transcriptional activator. Implicit in this conclusion is the premise that understanding the specific downstream loci regulated by MYC should provide insight into how MYC mediates its potent biological activities.

Figure 1.

Myc regulates targets genes with diverse functions. Myc-Max is depicted bound to an E-box (CACGTG) to recruit factors for the transcription of target genes, which are involved in many cellular processes. The bottom figure illustrates the binding of Myc to the MTA1 gene as determined by chromatin immunoprecipitation and direct sequence (ChIP-seq); the ENCODE Consortium F-Seq Density data were obtained from the UCSC Genome Browser. The peak heights represent intensity of Myc binding in 3 human cancer cell lines: K562, Hela, and HepG2.

It is worth noting that MYC functions not only as an activator of transcription but in some settings as a repressor.43-45 Transcriptional repression by MYC is distinct from MYC-mediated activation in that it does not typically require E-box elements in the repressed targets.46 Instead, in the few cases where it has been mapped, MYC represses targets through distinct promoter sequence motifs, including initiator elements (INR), SP1 sites, and others.44,47-49 MYC is recruited to these sites indirectly via interaction with DNA binding proteins such as MIZ-1 and NF-Y.48-51 Unlike transcriptional activation, the molecular mechanism by which MYC represses transcription remains elusive. Interestingly, the MbII domain is essential for both transcriptional activation and repression by MYC,52,53 and it remains entirely untested whether the known cofactors recruited via the MbII domain play a role in MYC-mediated repression, as they do in MYC-mediated activation.

The Search for MYC Target Genes

After more than a quarter century, the search for genes that are regulated by MYC has yielded a wealth of candidates that include mRNA, tRNA, rRNA, and miRNA (Fig. 1). Initially, dozens of downstream targets of MYC were identified by empirical methods and candidate-based approaches. These tactics were ultimately supplemented with early methods for unbiased mRNA expression analysis such as differential display and serial analysis of gene expression (SAGE). A small number of functional screens have also been conducted, in hopes of identifying downstream targets of MYC that can compensate for at least some of the activity lost when MYC activity is reduced. Over the past decade, the MYC target gene cascade has become exponentially complex, with genome-wide microarray-based screens adding several thousand potential MYC target genes to the growing list.54-66 (This number may be artificially high because most microarray screens do not formally distinguish between direct and indirect targets of MYC.67) Typically, unbiased approaches to expression profiling have found that among MYC’s transcriptional targets, two-thirds are activated and the remaining third repressed.

With the advent of robust chromatin immunoprecipitation methods (ChIP-chip, ChIP-PET, and ChIP-seq), we know not only which genes display altered expression when MYC activity is modulated but also which genomic loci are physically occupied by MYC. With some dependence on the cell type, MYC localizes to several thousand sites in the human genome, perhaps occupying up to 15% of all promoters. In embryonic stem cells, roughly 33% of all active genes have MYC bound within 1 kb of their transcriptional start site.40,68,69 Somewhat remarkably, a number of studies have found that a significant fraction of the loci occupied by MYC lack obvious DNA elements that resemble the CACGTG subset of E-boxes thought to be preferred by MYC/MAX heterodimers.

When expression profiling and genomic localization studies are overlaid, a preliminary set of direct MYC target genes can be defined. However, this also raises the issue of what level of evidence is required to formally prove an individual gene is a direct target of MYC. There are clearly many sites in the genome of a given cell where MYC binds without an obvious effect on transcription of adjacent genes.67 Does formal proof of a role for MYC require that the MYC binding site be eliminated or mutated in the endogenous locus and an effect on transcription documented? In a transcriptional version of Koch’s third postulate, should restoration of MYC activity be tested by mutating the site to allow recruitment of a MYC protein fused to a heterologous DNA binding domain?

Although the issue of what constitutes a direct target is of considerable importance when exploring biochemical mechanisms of transcriptional regulation by MYC, it is worth keeping in mind that for understanding MYC’s biological activities, the distinction between primary and secondary/tertiary targets is largely irrelevant. Any gene whose transcription is altered in response to changes in MYC activity, no matter how far downstream in the cascade, can have an important role in implementing the changes in cellular physiology that MYC controls.

The broad conceptual framework that has emerged from this quarter-century pursuit is that MYC is a master regulator of important biological pathways, such as protein translation, chromatin structure, and intermediate metabolism. The coordinate regulation of a pathway is typically accomplished both by MYC’s ability to regulate the transcription of individual loci encoding final effector proteins and by MYC’s ability to simultaneously regulate transcription of genes encoding global regulators of specific pathways. Three examples of these MYC-driven target gene cascades (chromatin structure, intermediate metabolism, and protein translation) are discussed below.

Coordinate Regulation of Multiple Target Genes within Specific Cellular Pathways by MYC

MYC Targets Involved in Chromatin Structure

MYC activation induces genome-wide changes in the epigenetic landscape of the cell, including changes in patterns of histone posttranslational modifications.70 Furthermore, MYC alters the pattern of histone localization, for example, triggering the localized deposition of the H2AX isoform.71 In addition to regulating changes in histone modifications and localization, MYC can regulate DNA methylation patterns via its recruitment of the methyltransferase DNMT3a.72

Thus far, it has been difficult to distinguish the extent of MYC’s broad effects on chromatin structure that are a direct result of its recruitment of chromatin-modifying cofactor complexes to its thousands of target genes versus a broader, indirect role in controlling chromatin structure. It is, however, clear that at least some of the observed changes in chromatin structure are controlled via MYC’s ability to modulate the transcription of specific target genes encoding critical epigenetic regulators.

An example of direct MYC targets that encode global chromatin regulators comes from the Eisenman group’s finding that MYC-induced, genome-wide changes in histone acetylation patterns result partly from transcriptional activation of the gene encoding one of the major cellular histone acetyltransferases, hGCN5.70 Further evidence that MYC regulates chromatin structure on a broad scale comes from identification of the insulator protein CTCF as a direct MYC target.73 Induction of CTCF allows MYC to alter the transcriptional output of vast areas of the genome by blocking the spread of facultative heterochromatin. A third, direct MYC target gene encoding a broad regulator of chromatin structure is MTA1 (see Fig. 1 for Myc binding to MTA1).39 Biological assays demonstrated that MTA1 induction is essential for invasive growth in MYC-transformed cells. At the biochemical level, MTA1 is an essential regulatory subunit of the transcriptional co-repressor complex termed NURD (for nucleosomal remodeling and deacetylase complex).74 As the name suggests, the NURD complex has two enzymatic activities that modulate chromatin structure, one that remodels or alters the positioning of nucleosomes within chromatin and another that catalyzes the removal of acetyl groups from specific lysines within histones. This deacetylase activity is generally correlated with decreased transcriptional output of genes in the vicinity.75,76 A summary of the examples discussed above supports the conclusion that, via control of transcription of the loci encoding hGCN5, CTCF, MTA1, and potentially other chromatin regulators, MYC exerts broad effects on the overall chromatin structure of the eukaryotic cell.

MYC Target Genes Control Broad Aspects of Intermediate Metabolism

Transformed cells have specific alterations in cellular metabolism.77 The importance of this observation, first made in the early 20th century by Otto Warburg, has gained heightened appreciation in recent years as molecular mechanisms for these metabolic differences have come to light. In brief, Warburg’s discovery (which was recognized by the 1931 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine) suggests that cancer cells produce energy largely via glycolysis rather than the more efficient process of oxidative phosphorylation.78,79 This preference for glycolysis occurs even when cancer cells are exposed to sufficient oxygen levels to allow oxidative phosphorylation. Given the ubiquitous overexpression of MYC in human cancer, a role for MYC in the Warburg effect seemed reasonable. Experimental evidence supporting this hypothesis came from the discovery that lactate dehydrogenase–A (LDH-A) is a direct MYC target.80,81 In fact, induction of LDH-A is required for MYC-mediated transformation, a criterion that has been satisfied for only a handful of MYC’s many targets. This enzyme, which is overexpressed in many cancers, converts pyruvate to lactate, thereby shunting it away from oxidative phosphorylation and toward glycolysis. The groundbreaking identification of LDH-A as an essential target of MYC set the stage for the numerous links that have been made between MYC target genes and metabolism over the subsequent decade (Fig. 1). Examples of these are discussed below.

Mitochondria are critical organelles for both energy production and the biosynthesis of macromolecules. As cancer cells generally divide more rapidly than their normal counterparts, they have heightened biosynthetic requirements. Furthermore, duplication of the mitochondria must increase with increased mitotic rates to keep pace with the dilution brought about by the rapid creation of progeny cells. Thus, it is not surprising that MYC has been linked to increased rates of mitochondrial biogenesis (Fig. 1),82,83 primarily via activation of target genes encoding (a) master regulators of mitochondrial pathways and (b) specific effector proteins imported into the mitochondria.

Among the master regulators of mitochondrial function, biosynthesis and metabolism that are encoded by direct MYC target genes are NRF1, PGC-1β, and TFAM.82-85 NFR1 encodes a transcription factor that was originally identified based on its ability to regulate transcription of the cytochrome C gene.86 Subsequent studies showed that cytochrome C was just one example among hundreds of nuclear genes regulated by NRF1 whose products are then imported into the mitochondria or otherwise important for mitochondrial function (reviewed in Scarpulla87). In fact, a recent ChIP-chip analysis showed that NRF1 binds the promoters of nearly 700 nuclear genes, with most of these encoding mitochondria-associated proteins.88 The link between NRF1, MYC, and cytochrome C is relatively complex, with the binding site for NFR1 in the cytochrome C locus containing a cryptic E-box that is also bound by MYC/MAX heterodimers in vivo.85 Through this shared binding site, NRF1 and MYC coordinate increased cytochrome C transcription. A similar collaboration between NRF1 and MYC mechanism takes place at other NRF1 targets, including cox5b and cox6A1,85 and likely occurs at many NRF1 target genes. Like most transcriptional activators, NRF1 is unable to increase expression of its mitochondria-associated target genes on its own. Instead, it requires the transcriptional cofactor PGC-1β, which is recruited to NRF1 target genes via a direct interaction between the two proteins.89,90 Presumably as a means of capitalizing on heightened NRF1 expression to increase mitochondrial biogenesis, MYC directly binds and activates transcription of the locus encoding PGC-1β.83 As alluded to above, NRF1 itself is encoded by a direct MYC target gene,84 and thus MYC impinges on this pathway at multiple points to achieve dynamically modulated mitochondrial biogenesis.

Both mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation require the increased expression of more than a thousand nuclear-encoded proteins that are imported into the mitochondria.91 However, mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation are also strictly dependent on the transcription of the 13 polypeptides encoded by the 16.6-kb mitochondrial genome.87,92 To efficiently control mitochondrial biogenesis, MYC must be able to control transcription of mitochondrial-encoded genes. MYC itself does not appear to function as a transcriptional regulator of the mitochondrial genome. Instead, MYC directly binds and increases the expression of the critical mitochondrial transcription factor TFAM.82 (Like cytochrome C, cox5b, and cox6A1, the TFAM locus is a direct transcriptional target of both NRF1 and MYC.85,93) The upregulation of TFAM by MYC provides at least part of the explanation for how MYC coordinates the increase in mitochondrial-encoded polypeptides (and tRNA and rRNA), with its broad upregulation on the hundreds of nuclear genes encoding mitochondrial components.

The ability of MYC to activate transcription of the genes encoding these central regulators of mitochondrial biogenesis and function is accompanied by MYC’s direct regulation of many of the nuclear-encoded mitochondrial components.82 This model is supported by a number of genome-wide expression studies that have identified a high proportion of these genes among MYC targets. For example, one landmark study that demonstrated MYC’s role in mitochondrial genome replication and biogenesis identified 281 mitochondrial ontology genes by expression profiling among a total of 2,679 MYC responsive genes.82 More recently, a study that combined expression profiling and ChIP-chip analysis to identify 1,469 direct MYC targets found 107 of these to encode proteins linked to mitochondrial biogenesis.84

Other MYC Target Genes Encoding Metabolic Regulators

Human cells have a much higher requirement for glutamine than for other amino acids, and cancer cells with high MYC activity undergo apoptosis if deprived of glutamine, presumably because they have become addicted to glutamine as an energy source.94 A molecular explanation for this effect came when a series of studies showed that MYC coordinately regulates the expression of genes encoding many of the proteins involved in glutamine uptake and metabolism.95,96 As true for many of the other MYC-regulated pathways, its control of glutamine metabolism is exerted at multiple steps in the process and via multiple mechanisms.

As an important first step, MYC binds and activates transcription of the loci encoding the two high-affinity glutamine importers ASCT2 and SN2.96 Inside the cell, glutamine enters the mitochondria, where it is converted by mitochondrial glutaminase (GLS) to glutamate and subsequently consumed for adenosine triphosphate (ATP) generation or for biosynthetic processes. MYC upregulates GLS expression, but not by a direct mechanism. Instead, MYC represses the transcription of 2 miRNAs, mir-23a and mir-23b, which normally target the GLS transcript.95 By decreasing these miRNAs, MYC increases GLS expression and further facilitates glutaminolysis.

Possibly related to MYC’s control of glutamine metabolism, MYC also controls the transcription of the genes encoding many of the enzymes involved in nucleotide biosynthesis.97 (Glutamine is a critical substrate for the first step in both the purine and pyrimidine synthesis pathways.) Similar to its increase in mitochondrial biogenesis, MYC’s ability to increase nucleotide pools is consistent with its role as a driver of the cell cycle (Fig. 1). Also similar, MYC controls transcription of many of the critical players in the pathway.

The CAD gene (for carbamoyl phosphate synthetase 2, aspartate transcarbamylase, dihydroorotase) encodes the first 3 rate-limiting enzymes in the pyrimidine biosynthesis pathway and, as expected, is critical for providing building blocks for increased nucleic acid synthesis in highly mitotic cells. By mapping promoter elements that confer cell cycle responsiveness to CAD transcription, an essential E-box was identified that binds MYC.98 A series of careful studies followed this initial observation, ultimately placing CAD among the best characterized of all MYC target genes.41,42,99,100 More recent studies have identified a number of other critical enzymes in the nucleotide biosynthesis pathways that are encoded by MYC targets. In one example, the thymidylate synthase (TS), inosine monophosphate dehydrogenase 2 (IMPDH2), and phosphoribosyl pyrophosphate synthetase 2 (PRPS2) genes were all demonstrated to be direct MYC targets.101 Somewhat remarkably, the simultaneous overexpression of these genes partially rescued the cell cycle defect caused when MYC was inhibited. A related study found gene encoding nucleotide synthesis enzymes highly enriched among loci directly bound by MYC.102 Functional studies were then conducted showing that IMPDH1 and IMPDH2 were specifically important as direct downstream effectors of MYC cell cycle promoting activity. Within this pathway, a screen for genes that could functionally rescue part of the proliferative defect observed in MYC-null cells led to the identification of serine hydroxymethyltransferase as a direct MYC target.103 This gene encodes a mitochondrial enzyme important for nucleotide synthesis and for other metabolic processes.

A final but highly noteworthy example of a MYC target gene encoding a critical regulator of nucleic acid function is that encoding ornithine decarboxylase (ODC). Like CAD, ODC was identified as a direct MYC target as a result of regulatory element mapping that implicated a critical E-box in the first intron of ODC.104 Subsequent studies led to the accumulation of convincing data that the induction of ODC gene transcription is an essential event in MYC-driven tumorigenesis.105,106 Functionally, ODC catalyzes an important step in polyamine biosynthesis. Polyamines, although not essential for the synthesis of nucleic acids, are required for stabilizing newly synthesized DNA and preventing genotoxic damage. These activities are of course consistent with the role of MYC in driving genome replication and mitosis.

MYC Target Genes Encode Molecules Central to Protein Synthesis

Studies of both the Drosophila and mammalian MYC proteins indicate that they play a role in cell growth and not simply in cell cycle progression.107-110 An increase in cell mass is known to be a prerequisite for progression through mitosis, so that growth and cell cycle control are in fact linked in many settings.111 Accumulation of cell mass is controlled by a number of critical processes, including translation efficiency. Recently, genes involved in various aspects of translation have been identified as MYC targets through expression profiling screens.54-60,112,113 Prior to this, empirical studies defined translation elongation factors and the protein chaperone HSP70 as proteins encoded by MYC target genes.112,114 The control of cell mass accumulation by MYC discussed above is also regulated in part by MYC via its role in the transcription of ribosomal RNA, ribosomal protein encoding genes, and tRNA. This is achieved by direct interactions between MYC and RNA PolI and PolIII complexes (reviewed in Oskarsson and Trumpp115). Finally, MYC also regulates the transcription of genes encoding proteins important for ribosome assembly (Fig. 1).116 Similar to the paradigm established for MYC’s control of energy metabolism, MYC controls the accumulation of protein mass within the cell by a multifocal approach that relies on regulation of the efficiency of translation, the assembly of ribosomes, and the control of protein conformation.

Conclusions

MYC controls the transcription of hundreds and perhaps thousands of mRNA, miRNA, rRNA, and tRNA loci. As a further complication, there has not been significant success in defining MYC targets whose transcription is activated across a broad set of cell lineages. The observation that many of MYC target genes are cell lineage specific has been difficult to reconcile with MYC’s nearly universal ability to drive cell cycle progression and even malignant transformation in most cell lineages. However, as discussed recently by others,117 many investigators hold out hope that critical downstream targets of MYC can be fished out from this current list of thousands, to provide nodes in the MYC pathway that are amenable to therapeutic targeting in human cancer. Although well-characterized MYC target genes encoding enzymes such as ODC, CAD, or LDH-A might seem like obvious candidates, their importance in all rapidly dividing cells may result in their inhibition having similar side effects as current therapeutics that indiscriminately target both normal and tumor cells based only on their high mitotic index. The first important steps in the process of defining additional, essential candidates for targeting have begun in many labs,38,103,118 where the functional requirement for individual MYC target genes is being used as a criterion for further analysis. MYC targets such as SHMT, MTA1, and IMPDH are among those that have emerged from these studies, and they clearly deserve our heightened attention.

In addition to the examples of MYC target genes controlling chromatin structure, intermediate metabolism, and protein translation, MYC controls groups of target genes involved directly in cell cycle regulation and other critical cellular processes, thus extending the paradigm of MYC’s preference for regulating many individual nodes in an individual cellular pathway. Finding the most sensitive of these nodes may ultimately affect the design of novel therapeutics.

Acknowledgments

I regret that practical reasons restrict me from referring to many of the important contributions that have been made by my colleagues to our understanding of the MYC target gene pathway.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the NIH: CA090465 (S.B.M.) and CA098172 (S.B.M.). In addition, this work was partially supported by funds from the Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement Program, Pennsylvania Department of Health.

The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Sheiness D, Fanshier L, Bishop JM. Identification of nucleotide sequences which may encode the oncogenic capacity of avian retrovirus MC29. J Virol. 1978;28:600-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sheiness D, Bishop JM. DNA and RNA from uninfected vertebrate cells contain nucleotide sequences related to the putative transforming gene of avian myelocytomatosis virus. J Virol. 1979;31:514-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Sheiness DK, Hughes SH, Varmus HE, Stubblefield E, Bishop JM. The vertebrate homolog of the putative transforming gene of avian myelocytomatosis virus: characteristics of the DNA locus and its RNA transcript. Virology. 1980;105:415-24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dalla-Favera R, Bregni M, Erikson J, Patterson D, Gallo RC, Croce CM. Human c-myc onc gene is located on the region of chromosome 8 that is translocated in Burkitts lymphoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:7824-7827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Subar M, Neri A, Inghirami G, et al. Frequent c-myc oncogene activation and infrequent presence of Epstein-Barr virus genome in AIDS-associated lymphoma. Blood. 1988;72:667-671 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shiramizu B, McGrath MS. Molecular pathogenesis of AIDS-associated non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1991;5:323-30 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Beral V, Peterman T, Berkelman R, Jaffe H. AIDS-associated non-Hodgkins lymphoma. Lancet. 1991;337:805-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Little CD, Nau MM, Carney DN, Gazdar AF, Minna JD. Amplification and expression of the c-myc oncogene in human lung cancer cell lines. Nature (Lond). 1983;306:194-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Munzel P, Marx D, Kochel H, Schauer A, Bock KW. Genomic alterations of the c-myc protooncogene in relation to the overexpression of c-erbB2 and Ki-67 in human breast and cervix carcinomas. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1991;117:603-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pinion SB, Kennedy JH, Miller RW, MacLean AB. Oncogene expression in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive cancer of cervix. Lancet. 1991;337:819-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Aoyama C, Peters J, Senadheera S, Liu P, Shimada H. Uterine cervical dysplasia and cancer: identification of c-myc status by quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Diagn Mol Pathol. 1998;7:324-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bieche I, Lidereau R. Genetic alterations in breast cancer. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1995;14:227-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Berns EM, Klijn JG, Smid M, et al. TP53 and MYC gene alterations independently predict poor prognosis in breast cancer patients. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;16:170-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Amati B, Alevizopoulos K, Vlach J. Myc and the cell cycle. Frontiers Biosci. 1998;3:250-68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nau MM, Brooks BJ, Battery J, et al. L-myc: a new myc-related gene amplified and expressed in human small cell lung cancer. Nature (Lond). 1985;318:69-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Schwab M, Alitalo K, Klempnauer KH, et al. Amplified DNA with limited homology to myc cellular oncogene is shared by human neuroblastoma cell lines and a neuroblastoma tumor. Nature (Lond). 1983;305:245-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kohl NE, Kanda N, Schreck RR, et al. Transposition and amplification of oncogene-related sequences in human neuroblastomas. Cell. 1983;35:359-67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Brodeur GM, Seeger RC, Schwab M, Varmus HE, Bishop JM. Amplification of N-Myc in untreated human neuroblastomas correlates with advanced disease stage. Science. 1984;224:1121-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Adams JM, Harris AW, Pinkert CA, et al. The c-myc oncogene driven by immunoglobulin enhancers induces lymphoid malignancy in transgenic mice. Nature. 1985;318:533-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Land H, Parada LF, Weinberg RA. Tumorigenic conversion of primary embryo fibroblasts requires at least two cooperating oncogenes. Nature. 1983;304:596-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dang CV. c-Myc target genes involved in cell growth, apoptosis, and metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nesbit CE, Tersak JM, Prochownik EV. MYC oncogenes and human neoplastic disease. Oncogene. 1999;18:3004-16 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hann SR, Eisenman RN. Proteins encoded by the human c-myc oncogene: differential expression in neoplastic cells. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:2486-97 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Eisenman RN, Tachibana CY, Abrams HD, Hann SR. V-myc- and c-myc-encoded proteins are associated with the nuclear matrix. Mol Cell Biol. 1985;5:114-26 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Max: a helix-loop-helix zipper protein that forms a sequence-specific DNA-binding complex with Myc. Science. 1991;251:1211-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Blackwood EM, Kretzner L, Eisenman RN. Myc and Max function as a nucleoprotein complex. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1992;2:227-35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Blackwood EM, Luscher B, Eisenman RN. Myc and max associate in-vivo. Genes Dev. 1992;6:71-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Prendergast GC, Ziff EB. Methylation-sensitive sequence-specific DNA binding by the c-Myc basic region. Science. 1991;251:186-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Blackwell TK, Huang J, Ma A, et al. Binding of myc proteins to canonical and noncanonical DNA sequences. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:5216-24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Prendergast GC, Lawa D, Ziff EB. Association of Myn, the murine homolog of Max, with c-Myc stimulates methylation-sensitive DNA binding and Ras cotransformation. Cell. 1991;65:395-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kato GJ, Barrett J, Villa-Garcia M, Dang CV. An amino-terminal c-Myc domain required for neoplastic transformation activates transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:5914-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sarid J, Halazonetis TD, Murphy W, Leder P. Evolutionarily conserved regions of the human c-myc protein can be uncoupled from transforming activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:170-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Stone J, DeLange T, Ramsay G, et al. Definition of regions in human c-myc that are involved in transformation and nuclear localization. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1697-709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Gallant P, Shiio Y, Cheng PF, Parkhurst SM, Eisenman RN. Myc and Max homologs in Drosophila. Science. 1996;274:1523-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Kim SY, Herbst A, Tworkowski KA, Salghetti SE, Tansey WP. Skp2 regulates Myc protein stability and activity. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1177-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. von der Lehr N, Johansson S, Wu S, et al. The F-box protein Skp2 participates in c-Myc proteosomal degradation and acts as a cofactor for c-Myc-regulated transcription. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1189-200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McMahon SB, Van Buskirk HA, Dugan KA, Copeland TD, Cole MD. The novel ATM-related protein TRRAP is an essential cofactor for the c-Myc and E2F oncoproteins. Cell. 1998;94:363-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhang XY, Desalle LM, McMahon SB. Identification of novel targets of MYC whose transcription requires the essential MbII fomain. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:238-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang XY, DeSalle LM, Patel JH, et al. Metastasis-associated protein 1 (MTA1) is an essential downstream effector of the c-MYC oncoprotein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13968-73 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Rahl PB, Lin CY, Seila AC, et al. Young, c-Myc regulates transcriptional pause release. Cell. 2010;141:432-45 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Eberhardy SR, Farnham PJ. c-Myc mediates activation of the cad promoter via a post-RNA polymerase II recruitment mechanism. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:48562-71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Eberhardy SR, Farnham PJ. Myc recruits P-TEFb to mediate the final step in the transcriptional activation of the cad promoter. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:40156-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Kretzner L, Blackwood EM, Eisenman RN. Transcriptional activities of the Myc and Max proteins in mammalian cells. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1992;182:435-43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lee LA, Dolde C, Barrett J, Wu CS, Dang CV. A link between c-Myc-mediated transcriptional repression and neoplastic transformation. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1687-95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Patel JH, McMahon SB. BCL2 is a downstream effector of MIZ-1 essential for blocking c-MYC-induced apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5-13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Wanzel M, Herold S, Eilers M. Transcriptional repression by Myc. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:146-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gartel AL, Shchors K. Mechanisms of c-myc-mediated transcriptional repression of growth arrest genes. Exp Cell Res. 2003;283:17-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Staller P, Peukert K, Kiermaier A, et al. Repression of p15INK4b expression by Myc through association with Miz-1. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:392-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Seoane J, Pouponnot C, Staller P, Schader M, Eilers M, Massague J. TGFbeta influences Myc, Miz-1 and Smad to control the CDK inhibitor p15INK4b. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:400-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Izumi H, Molander C, Penn LZ, Ishisaki A, Kohno K, Funa K. Mechanism for the transcriptional repression by c-Myc on PDGF beta-receptor. J Cell Sci. 2001;114(pt 8):1533-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Patel JH, McMahon SB. Targeting of MIZ-1 is essential for MYC mediated apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:3283-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Penn LJZ, Brooks MW, Laufer EM, et al. Domains of human c-Myc protein required for autosuppression and cooperation with ras oncogenes are overlapping. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:4961-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Li LH, Nerlov C, Prendergast G, MacGregor D, Ziff EB. c-Myc represses transcription in vivo by a novel mechanism dependent on the initiator element and Myc box II. EMBO J. 1994;13:4070-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Guo QM, Malek RL, Kim S, et al. Identification of c-myc responsive genes using rat cDNA microarray. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5922-8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Schuhmacher M, Kohlhuber F, Holzel M, et al. The transcriptional program of a human B cell line in response to Myc. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:397-406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Neiman PE, Ruddell A, Jasoni C, et al. Analysis of gene expression during myc oncogene-induced lymphomagenesis in the bursa of Fabricius. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:6378-83 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Nesbit CE, Tersak JM, Grove LE, Drzal A, Choi H, Prochownik EV. Genetic dissection of c-myc apoptotic pathways. Oncogene. 2000;19:3200-12 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Coller HA, Grandori C, Tamayo P, et al. Expression analysis with oligonucleotide microarrays reveals that MYC regulates genes involved in growth, cell cycle, signaling, and adhesion. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:3260-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Kim S, Zeller K, Dang CV, Sandgren EP, Lee LA. A strategy to identify differentially expressed genes using representational difference analysis and cDNA arrays. Anal Biochem. 2001;288:141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Boon K, Caron HN, van Asperen R, et al. N-myc enhances the expression of a large set of genes functioning in ribosome biogenesis and protein synthesis. Embo J. 2001;20:1383-93 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. O’Connell BC, Cheung AF, Simkevich CP, et al. A large scale genetic analysis of c-Myc-regulated gene expression patterns. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:12563-73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Schuldiner O, Shor S, Benvenisty N. A computerized database-scan to identify c-MYC targets. Gene. 2002;292:91-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Louro ID, Bailey EC, Li X, et al. Comparative gene expression profile analysis of GLI and c-MYC in an epithelial model of malignant transformation. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5867-73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Watson JD, Oster SK, Shago M, Khosravi F, Penn LZ. Identifying genes regulated in a Myc-dependent manner. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:36921-30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Menssen A, Hermeking H. Characterization of the c-MYC-regulated transcriptome by SAGE: identification and analysis of c-MYC target genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:6274-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Yu Q, He M, Lee NH, Liu ET. Identification of Myc-mediated death response pathways by microarray analysis. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:13059-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Patel JH, Loboda AP, Showe MK, Showe LC, McMahon SB. Analysis of genomic targets reveals complex functions of MYC. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4:562-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Kidder BL, Yang J, Palmer S. Stat3 and c-Myc genome-wide promoter occupancy in embryonic stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Chen X, Xu H, Yuan P, et al. Integration of external signaling pathways with the core transcriptional network in embryonic stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:1106-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Knoepfler PS, Zhang XY, Cheng PF, Gafken PR, McMahon SB, Eisenman RN. Myc influences global chromatin structure. Embo J. 2006;25:2723-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Martinato F, Cesaroni M, Amati B, Guccione E. Analysis of Myc-induced histone modifications on target chromatin. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Brenner C, Deplus R, Didelot C, et al. Myc represses transcription through recruitment of DNA methyltransferase corepressor. Embo J. 2005;24:336-46 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Chau CM, Zhang XY, McMahon SB, Lieberman PM. Regulation of Epstein-Barr virus latency type by the chromatin boundary factor CTCF. J Virol. 2006;80:5723-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Xue Y, Wong J, Moreno GT, Young MK, Cote J, Wang W. NURD, a novel complex with both ATP-dependent chromatin-remodeling and histone deacetylase activities. Mol Cell. 1998;2:851-61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Lachner M, O’Carroll D, Rea S, Mechtler K, Jenuwein T. Methylation of histone H3 lysine 9 creates a binding site for HP1 proteins. Nature. 2001;410:116-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Mazumdar A, Wang RA, Mishra SK, et al. Transcriptional repression of oestrogen receptor by metastasis-associated protein 1 corepressor. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:30-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. DeBerardinis RJ, Lum JJ, Hatzivassiliou G, Thompson CB. The biology of cancer: metabolic reprogramming fuels cell growth and proliferation. Cell Metab. 2008;7:11-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Warburg O. On the origin of cancer cells. Science. 1956;123:309-14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Warburg O. On respiratory impairment in cancer cells. Science. 1956;124:269-70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Shim H, Dolde C, Lewis BC, et al. c-Myc transactivation of LDH-A: implications for tumor metabolism and growth. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:6658-63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Lewis BC, Prescott JE, Campbell SE, et al. Tumor induction by the c-Myc target genes rcl and lactate dehydrogenase A. Cancer Res. 2000;60:6178-83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Li F, Wang Y, Zeller KI, et al. Myc stimulates nuclearly encoded mitochondrial genes and mitochondrial biogenesis. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:6225-34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Zhang H, Gao P, Fukuda R, et al. HIF-1 inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis and cellular respiration in VHL-deficient renal cell carcinoma by repression of C-MYC activity. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:407-20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Kim J, Lee JH, Iyer VR. Global identification of Myc target genes reveals its direct role in mitochondrial biogenesis and its E-box usage in vivo. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Morrish F, Giedt C, Hockenbery D. c-MYC apoptotic function is mediated by NRF-1 target genes. Genes Dev. 2003;17:240-55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Virbasius CA, Virbasius JV, Scarpulla RC. NRF-1, an activator involved in nuclear-mitochondrial interactions, utilizes a new DNA-binding domain conserved in a family of developmental regulators. Genes Dev. 1993;7:2431-45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Scarpulla RC. Transcriptional paradigms in mammalian mitochondrial biogenesis and function. Physiol Rev. 2008;88:611-38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Cam H, Balciunaite E, Blais A, et al. A common set of gene regulatory networks links metabolism and growth inhibition. Mol Cell. 2004;16:399-411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Lin J, Handschin C, Spiegelman BM. Metabolic control through the PGC-1 family of transcription coactivators. Cell Metab. 2005;1:361-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Lin J, Puigserver P, Donovan J, Tarr P, Spiegelman BM. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1beta (PGC-1beta), a novel PGC-1-related transcription coactivator associated with host cell factor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:1645-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Bonawitz ND, Clayton DA, Shadel GS. Initiation and beyond: multiple functions of the human mitochondrial transcription machinery. Mol Cell. 2006;24:813-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Scarpulla RC. Nuclear control of respiratory gene expression in mammalian cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;97:673-83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Piantadosi CA, Suliman HB. Mitochondrial transcription factor A induction by redox activation of nuclear respiratory factor 1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:324-33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Dang CV. Rethinking the Warburg effect with Myc micromanaging glutamine metabolism. Cancer Res. 2010;70:859-62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Gao P, Tchernyshyov I, Chang TC, et al. c-Myc suppression of miR-23a/b enhances mitochondrial glutaminase expression and glutamine metabolism. Nature. 2009;458:762-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Wise DR, DeBerardinis RJ, Mancuso A, et al. Myc regulates a transcriptional program that stimulates mitochondrial glutaminolysis and leads to glutamine addiction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:18782-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. McMahon SB. Control of nucleotide biosynthesis by the MYC oncoprotein. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2275-6 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Miltenberger RJ, Sukow KA, Farnham PJ. An E-box-mediated increase in cad transcription at the G1/S-phase boundary is suppressed by inhibitory c-Myc mutants. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:2527-35 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Boyd KE, Farnham PJ. Myc versus USF: discrimination at the cad gene is determined by core promoter elements. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:2529-37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Eberhardy SR, D’Cunha CA, Farnham PJ. Direct examination of histone acetylation on Myc target genes using chromatin immunoprecipitation. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:33798-805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Mannava SV, Grachtchouk LJ, Wheeler M, et al. Direct role of nucleotide metabolism in C-MYC-dependent proliferation of melanoma cells. Cell Cycle. 2008;7:2392-400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Liu YC, Li F, Handler J, et al. Global regulation of nucleotide biosynthetic genes by c-Myc. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Nikiforov MA, Chandriani S, O’Connell B, et al. A functional screen for Myc-responsive genes reveals serine hydroxymethyltransferase, a major source of the one-carbon unit for cell metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:5793-800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Bello-Fernandez C, Packham G, Cleveland JL. The ornithine decarboxylase gene is a transcriptional target of c-Myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:7804-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Nilsson JA, Keller TA, Baudino C, et al. Targeting ornithine decarboxylase in Myc-induced lymphomagenesis prevents tumor formation. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:433-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Packham G, Cleveland JL. Ornithine decarboxylase is a mediator of c-Myc-induced apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:5741-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Iritani BM, Eisenman RN. c-Myc enhances protein synthesis and cell size during B lymphocyte development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:13180-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Johnston LA, Prober DA, Edgar BA, Eisenman RN, Gallant P. Drosophila myc regulates cellular growth during development. Cell. 1999;98:779-90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Schuhmacher M, Staege MS, Pajic A, et al. Control of cell growth by c-Myc in the absence of cell division. Curr Biol. 1999;9:1255-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Mateyak MK, Obaya AJ, Adachi S, Sedivy JM. Phenotypes of c-Myc-deficient rat fibroblasts isolated by targeted homologous recombination. Cell Growth Differ. 1997;8:1039-48 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Conlon I, Raff M. Size control in animal development. Cell. 1999;96:235-44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Jones RM, Branda J, Johnston KA, et al. An essential E box in the promoter of the gene encoding the mRNA cap-binding protein (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) is a target for activation by c-myc. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4754-64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Rosenwald IB, Rhoads DB, Callanan LD, Isselbacher KJ, Schmidt EV. Increased expression of eukaryotic translation initiation factors eIF-4E and eIF-2 alpha in response to growth induction by c-myc. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6175-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Kingston RE, Baldwin AS, Jr, Sharp PA. Regulation of heat shock protein 70 gene expression by c-myc. Nature. 1984;312:280-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Oskarsson T, Trumpp A. The Myc trilogy: lord of RNA polymerases. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:215-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Greasley PJ, Bonnard C, Amati B. Myc induces the nucleolin and BN51 genes: possible implications in ribosome biogenesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:446-53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Freie BW, Eisenman RN. Ratcheting Myc. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:425-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Chandriani S, Frengen E, Cowling VH, et al. A core MYC gene expression signature is prominent in basal-like breast cancer but only partially overlaps the core serum response. PLoS ONE. 2009;4:e6693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]