Abstract

The prion protein (PrP) is best known for its association with prion diseases. However, a controversial new role for PrP in Alzheimer disease (AD) has recently emerged. In vitro studies and mouse models of AD suggest that PrP may be involved in AD pathogenesis through a highly specific interaction with amyloid-β (Aβ42) oligomers. Immobilized recombinant human PrP (huPrP) also exhibited high affinity and specificity for Aβ42 oligomers. Here we report the novel finding that aggregated forms of huPrP and Aβ42 are co-purified from AD brain extracts. Moreover, an anti-PrP antibody and an agent that specifically binds to insoluble PrP (iPrP) co-precipitate insoluble Aβ from human AD brain. Finally, using peptide membrane arrays of 99 13-mer peptides that span the entire sequence of mature huPrP, two distinct types of Aβ binding sites on huPrP are identified in vitro. One specifically binds to Aβ42 and the other binds to both Aβ42 and Aβ40. Notably, Aβ42-specific binding sites are localized predominantly in the octapeptide repeat region, whereas sites that bind both Aβ40 and Aβ42 are mainly in the extreme N-terminal or C-terminal domains of PrP. Our study suggests that iPrP is the major PrP species that interacts with insoluble Aβ42 in vivo. Although this work indicated the interaction of Aβ42 with huPrP in the AD brain, the pathophysiological relevance of the iPrP/Aβ42 interaction remains to be established.

Keywords: Alzheimers Disease, Amyloid, Brain, Peptide Arrays, Prions, Gene 5 Protein, Prion diseases, Immunoprecipitation

Introduction

Alzheimer disease (AD)2 is the leading cause of dementia in the elderly and the most common neurodegenerative disorder. The underlying pathology in AD seems to be associated with the accumulation of soluble and insoluble aggregated species of the amyloid-β (Aβ) peptide in the brain (1). However, the mechanisms underlying Aβ deposition and neurotoxicity remain poorly understood. The cellular prion protein (PrPC) is a glycoprotein highly expressed in the brain, and best known for its association with prion diseases. These are unique neurodegenerative disorders with an infectious, sporadic or genetic etiology, and which are characterized by deposition of misfolded, pathological PrP (PrPSc) in the brain (2). Interestingly, a recent interpretation of early and newer observations suggests that PrPC may play a role in the pathogenesis of AD (3). Epidemiological studies suggest that the Met/Val polymorphism at residue 129 in PrP modulates the number of Aβ deposits (4). Also, pathological evidence indicates that PrP deposits often accompany Aβ plaques in AD (5–7). Moreover, transgenic mice expressing mutant amyloid precursor protein (APP) and overexpressing hamster PrPC present an exacerbated Aβ plaque burden (8). The circumstantial evidence of an association between PrP and Aβ was greatly strengthened by the recent finding that PrP was the protein that most strongly supported the binding of cells to soluble Aβ42 oligomers in a screen of 225,000 murine clones (9). The authors also showed that although Aβ42 oligomers suppressed long-term potentiation (LTP) in CA1 hippocampal neurons in mouse brain slices, LTP inhibition did not occur in brain slices from mice lacking the PrP gene (Prnp−/−) (9). Moreover, deleting the N-terminal region of murine PrP (PrP32–106) or blocking that region with specific antibodies against PrP93–109 significantly reduced LTP inhibition (9). In a genetic AD model where the Aβ plaque burden resulted from APP and presenilin 1 (APPswe/PS1ΔE9) transgenes, the elimination of PrP (Prnp−/−) rescued the impairment of spatial learning and memory (10). This evidence led the authors to conclude that PrP mediates Aβ neurotoxicity through direct binding to toxic Aβ species (3).

However, conflicting results raise questions about the pathophysiological relevance of the PrP/Aβ interaction. For instance, overexpression of PrPC inhibited β-secretase cleavage of APP and the consequent production of Aβ, whereas Aβ production was increased in PrP-deficient cells and the PrP knock-out mouse brain (11). The most robust evidence against the presumed key role of PrPC in Aβ-dependent LTP mediation and memory impairment comes from new observations reported independently by three research groups (12–14). Using different approaches, the three groups assessed the effect of removing Prnp, and all concluded that absence of PrP did not affect memory impairment induced by Aβ42 oligomers. First, injection of Aβ42 oligomers into the brain of mice resulted in long-term memory impairment regardless of the presence of PrP (12). Moreover, neither elimination nor overexpression of PrP affected LTP dysfunction caused by Aβ accumulation in a different mouse model of AD (APPKM670/671NL/PS1L166P) (13). Finally, viral expression of mutant APP in hippocampal slices induced LTP inhibition in control and Prnp−/− mice brains (14). Thus, despite disagreement over the role of PrP in AD (15), the specific binding of Aβ42 oligomers to mouse PrP (moPrP) was confirmed in these studies.

Because there are 20 amino acid differences between the mature mouse and human PrP (huPrP), these studies did not address the question of whether huPrP interacts with Aβ42. In particular, the moPrP93–109 sequence that reportedly binds Aβ42 oligomers contains three different amino acids with respect to huPrP94–110. However, another recent paper addressed this question by immobilizing recombinant huPrP to a sensor chip to determine binding to Aβ42 (16). This study confirmed the binding of huPrP to Aβ42 and the role of the N-terminal domain in this interaction, thus reproducing the binding results obtained with moPrP.

Now that several studies have confirmed the binding of murine and human PrP to Aβ42, the next question is whether this interaction also occurs in the human brain in vivo and whether differential binding occurs in AD and control brains. In our study, using gel filtration, we found that aggregated forms of huPrP and Aβ were co-purified in AD brains. Also, Aβ was co-immunoprecipitated with huPrP in brain homogenates from AD patients. Moreover, we observed that insoluble forms of PrP and Aβ were co-captured by a single-stranded DNA-binding protein called gene 5 protein (g5p). The g5p molecule specifically captures various PrPSc species in prion-infected brains, as well as an insoluble PrP conformer (called iPrP) in uninfected brains (17, 18). Using a peptide membrane array, we identified distinct Aβ42 and Aβ40 binding sites on huPrP. Most Aβ42-specific binding is clustered in the unfolded N-terminal domain, especially in the octapeptide repeat region, an observation that confirms previous reports (9, 12, 16). Two additional Aβ42-specific binding sites were observed on the middle and C-terminal PrP domains, respectively. Our study demonstrates that the interaction of huPrP and Aβ is found exclusively in the AD brain, and that this interaction principally involves insoluble forms of huPrP and Aβ.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents and Antibodies

Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) was purchased from Sigma. Amino-PEG cellulose membranes and Fmoc (N-(9-fluorenyl)methoxycarbonyl)-derivatives were obtained from Intavis (San Marcos, CA). Reagents for enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL Plus) were obtained from Amersham Biosciences, Inc. Magnetic beads (Dynabeads M-280, tosylactivated) were from Dynal Co. (Oslo, Norway). The anti-PrP antibodies used included specific monoclonal antibodies 3F4 (19, 20) and 6D11 from Signet Laboratories, Inc. (Dedham, MA), and a polyclonal antibody against the N-terminal domain of PrP (PrP23–40) called Anti-N (21). The anti-Aβ monoclonal antibodies, including 6E10 (reactive to residues 6–9 of human Aβ) and 4G8 (reactive to residues 17–24 of human Aβ), were obtained from Signet (Signet Laboratories, Dedham, MA). The two synthetic Aβ40 and Aβ42 peptides were purchased from Sigma.

Brain Tissues

Following protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board of Case Western Reserve University (Cleveland, OH), frontal cortex was collected at autopsy and stored at −80 °C for this study. The postmortem interval of these brain tissues was between 1 and 24 h. Cases of clinically and pathologically diagnosed AD (n = 5, ages 83.4 ± 2.7 between 80 and 87 years) and normal controls (n = 5, ages 73.6 ± 16.7 between 51 and 92 years) were used. Gray matter was dissected out and homogenized as described below. Also, transgenic mice expressing human APP, carrying both the Swedish (K670N, M671L) and Indiana (V717F) mutations (22, 23), were euthanized with pentobarbital following the university-approved animal protocol. The brains from mice aged between 2 and 18 months either expressing APP (n = 5) or wild type (n = 9) were dissected and immediately stored at −80 °C.

Preparation of Gene 5 Protein (g5p)

The recombinant g5p was isolated from Escherichia coli, transformed with an Ff gene 5-containing plasmid, and purified using DNA-cellulose affinity plus Sephadex G75 sizing columns, as described (24). The purity was >99% as determined by quantitation of Coomassie Blue-stained bands on SDS-PAGE.

Preparation of Brain Homogenates

10% (w/v) brain homogenates were prepared as described previously (17). When required, brain homogenates were centrifuged at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C to collect supernatants (S1). To prepare soluble (S2) and insoluble (P2) fractions, S1 was further centrifuged at 35,000 rpm (100,000 × g) for 1 h at 4 °C in an SW55 rotor (Beckman Coulter, Fullerton, CA).

Size Exclusion Chromatography

Size exclusion chromatography, also called gel filtration, was performed as described previously (17). In brief, Superdex 200 HR beads (GE Healthcare) in a 1 × 30-cm column were used to determine the oligomeric state of PrP and Aβ molecules. Chromatography was performed in an FPLC (fast protein liquid chromatography) system (GE Healthcare) at a flow rate of 250 μl/min, and fractions of 250 μl each were collected. Supernatant prepared by centrifugation of 20% brain homogenate at 1,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C was incubated with an equal volume of 2% Sarcosyl for 30 min on ice. A 200-μl sample of each was injected into the column for each size exclusion run. The molecular mass of the various PrP and Aβ species recovered in different FPLC fractions was evaluated according to a calibration curve generated with gel filtration of the molecular mass markers (Sigma) including dextran blue (2,000 kDa), thyroglobulin (669 kDa), apoferritin (443 kDa), β-amylase (200 kDa), alcohol dehydrogenase (150 kDa), albumin (66 kDa), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa). These standards were loaded independently at the concentrations recommended by Sigma in 200-μl sample volumes.

Determination of Binding Sites by Peptide Membrane Arrays

The general method for preparing multiple overlapping peptides bound to cellulose membranes has been described in detail previously (25). The PrP peptide membrane array contained 99 overlapping 13-mer peptides spanning the entire sequence of the mature full-length human PrP23–231; each successive peptide was shifted by 2 amino acids from the previous one from the N to C terminus of PrP. The arrays were synthesized in 9 lines, with 12 spots in each line except the last line with only 3 spots. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in TBST (150 mm NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6) at 37 °C for 2 h; the huPrP peptide membrane was incubated with Aβ40 or Aβ42 at the designated concentrations in TBS-T for 3 h, and then incubated with 4G8, an anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody, at 1:3,000 in 3% skim milk for 2 h at 37 °C. The membrane was washed with TBST and then incubated at 37 °C with 1:4,000 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG for 1 h. After a final wash, the membrane was treated with the ECL Western blotting detection reagent (Amersham Biosciences), and the signal was detected using a Bio-Rad Fluorescent Imager. The control experiments included the membranes only probed with the secondary antibody, HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG, omitting the 4G8 antibody or membranes probed with 4G8 antibody followed by the secondary antibody in the absence of Aβ incubation.

Specific Capture or Co-immunoprecipitation of PrP and Aβ by g5p or 3F4

The g5p molecule or anti-PrP antibody 3F4 was conjugated to 7 × 108 tosyl-activated magnetic beads in 1 ml of PBS at 37 °C for 20 h. The specific capture or immunoprecipitation of PrP or Aβ by g5p or 3F4 was performed as described (17, 26) by incubating S1, S2, or P2 fractions with conjugated beads.

Negative Staining and Electron Microscopy

Aβ40 or Aβ42 in PBS was adsorbed onto carbon films supported on Formvar membrane-coated nickel grids. The excess buffered protein solution was removed, and negatively stained with 2% uranyl acetate. Grids were then washed by touching the buffer and the excess buffer was immediately blotted using Whatman filter paper. Grids were then air-dried and kept at room temperature. Negatively stained specimens were observed by a JEOL 1200EX electron microscope (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) with 80 kV of electron acceleration voltage.

Western Blot Analysis

After determining the protein concentrations of each sample, equal amounts of samples were resolved on 15% Tris-HCl Criterion pre-cast gels (Bio-Rad) at 150 V for ∼80 min. The proteins on the gels were transferred to PVDF for 2 h at 70 V. The membranes were incubated for 2 h at room temperature with primary antibodies 3F4 (1:40,000), 6D11 (1:6,000), anti-N (1:6,000), 4G8 (1:3,000), or 6E10 (1:3,000) for probing the PrP molecule, or Aβ. Following incubation with HRP-conjugated sheep anti-mouse IgG at 1:3,000 or goat anti-rabbit IgG at 1:3,000, the PrP, or Aβ bands or spots were visualized on Kodak film using ECL Plus, in accordance with the manufacturer's protocol.

RESULTS

Co-elution of Aggregated PrP and Aβ from Brain of AD Mice

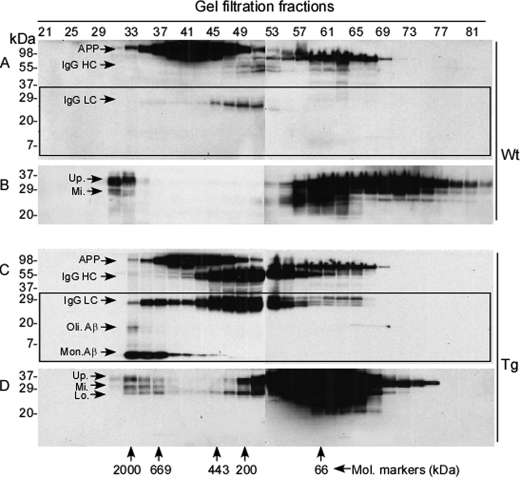

We have previously shown that the brains of uninfected humans and animals accumulate small amounts of various insoluble PrP oligomers and aggregates in addition to the dominant monomeric PrPC species by gel filtration (17). We denoted these newly identified PrP conformers insoluble PrP species (iPrP), suggesting a possibility that they may be precursors or partners in prion diseases or other protein aggregation disorders. PrP deposits have been observed histologically around the amyloid plaques in AD brains (5–7), raising the possibility that unique isoforms of PrP physically interact with Aβ in vivo. To determine whether PrP aggregates interact with Aβ in vivo and which specific PrP conformers are involved in this interaction, we performed gel filtration with brain homogenates from the AD transgenic mouse model that expresses human APP carrying both the Swedish and Indiana mutations, resulting in high levels of Aβ accumulation upon aging (22, 23). A series of gel filtration fractions were collected according to molecular mass of the proteins. Then we determined the presence of PrP and Aβ in each fraction by Western blot analysis. As expected, no monomeric or oligomeric Aβ species were detected in the brain homogenates prepared from wild type mice around fraction 30 that contains large aggregates (Fig. 1A, highlighted by rectangle) or 2-month-old APP transgenic mice (not shown) in addition to APP migrating at ∼110 kDa and nonspecific heavy (HC) and light (LC) chains of IgG. However, these mice accumulated high molecular mass PrP moieties with molecular mass ranging from 669 to 2,000 kDa (fractions 33 to 37), indicating the presence of iPrP (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

Size distribution of PrP and Aβ from brains of APP transgenic mice. Brain homogenates from 18-month-old wild type or APP transgenic mice were subjected to gel filtration prior to Western blot analysis with antibody against either Aβ (6E10, panels A and C) or PrP (6D11, panels B and D). PrP and Aβ were examined in the fractions between 21 and 81. Panels A and B represent brain samples from wild type mice, whereas panels C and D represent brain samples from APP transgenic mice. Western blotting of Aβ probed with 6E10 shows that the wild type mice do not accumulate Aβ aggregates (A), whereas APP transgenic mice produce Aβ aggregates (C) in the same fractions as PrP aggregates (D). Western blotting of PrP detected with 6D11 shows that both wild type and APP transgenic mice generate large PrP aggregates (fractions 31–37) (B and D). In addition to monomeric (Mon.) and oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species, APP (>98 kDa), the heavy chain (HC, ∼50–55 kDa), and light chain (LC, ∼22–25 kDa) of IgG were also detected in the blots probed with 6E10 (A and C). The rectangles in blots A and C are used to highlight the blot area where monomeric and oligomeric Aβ bands migrate. IgG LC might be present in the PrP bands in the blots probed with 6D11 (B and D). In comparison to wild type mice, more IgG HC and LC were detected in APP transgenic mice. Up., PrP upper band; Mi., PrP middle band; and Lo., PrP lower band.

We next analyzed the brain homogenates from 18-month-old APP transgenic mice, which are known to contain amyloid pathology in the brain (22, 23). Consistent with this expectation, we detected monomeric and oligomeric Aβ species in fractions 33–37 that contain aggregates with molecular masses between 669 and 2,000 kDa (Fig. 1C, highlighted by rectangle), indicating the presence of fibrillar complexes. The monomeric and oligomeric Aβ species detected by Western blotting might be derived from larger Aβ aggregates denatured during sample preparation for Western blotting. As before, there were APP and nonspecific bands including IgG HC and LC above ∼22 kDa (Fig. 1C). The Aβ aggregates are most likely comprised of Aβ42. Interestingly, PrP aggregates were eluted in the same fractions (33–37) (Fig. 1D). Because these mice do not have a prion disease, the Aβ42 aggregates eluted with iPrP (Fig. 1, C and D), suggesting that iPrP may form a complex with Aβ42 aggregates in the brains of APP transgenic mice. Alternatively, iPrP and Aβ42 aggregates may have the same molecular mass without physical interaction. The bands above ∼22 kDa mainly included APP, IgG HC, and IgG LC. These bands were frequently observed in animal samples and immunoprecipitates. Because these bands are not relevant to the current study, we focused on bands below IgG LC in most of the following figures to avoid distraction from our main interest, the complex of Aβ with PrP.

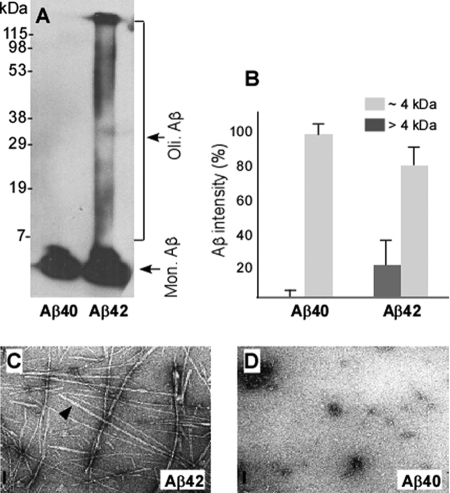

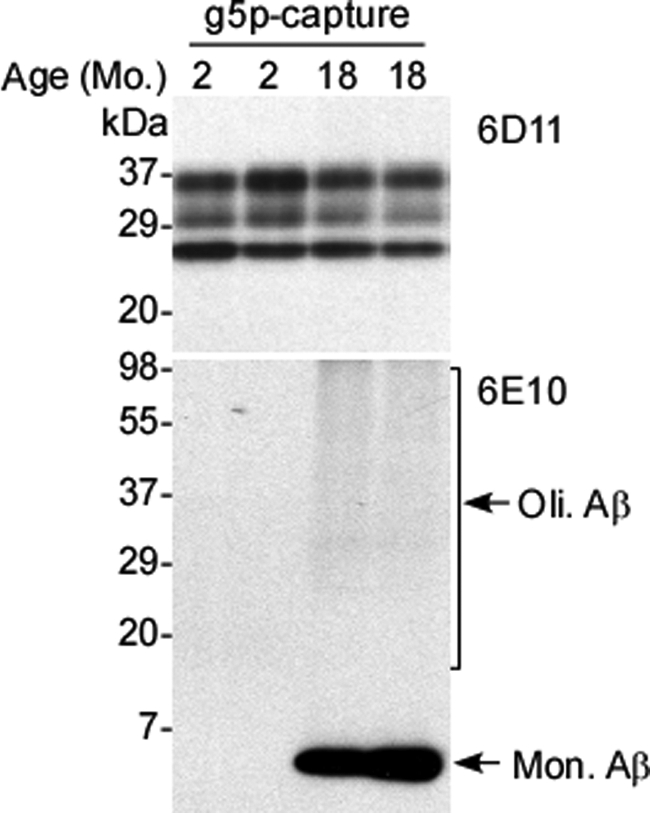

Co-capture of iPrP and Aβ in Mice

To determine whether iPrP and Aβ aggregates form complexes in vivo, we next conducted capture of iPrP by g5p in brain extracts from APP transgenic mice. The iPrP species associates with g5p and are captured by g5p-conjugated magnetic beads (17). If iPrP and Aβ form complexes in vivo, Aβ should be captured together with iPrP by g5p. The g5p capture was performed with brain extracts from APP transgenic mice prior to Western blotting. Blots were probed with anti-PrP or anti-Aβ antibody. The iPrP species were easily identified in both young (2-month-old) and old (18-month-old) APP transgenic mice (Fig. 2, top). Additionally, a single intense band migrating at ∼4 kDa, corresponding to monomeric (Mon.) Aβ, and a faint smear migrating above 20 kDa, corresponding to oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species, were also co-captured from brain extracts of aged but not young mice, consistent with the expected dynamics of Aβ42 accumulation (Fig. 2, bottom). Because an excess of Aβ42 over Aβ40 is observed in aged APP transgenic mice (22), the Aβ co-captured by g5p along with iPrP in the aged APP transgenic mice could be Aβ42 instead of Aβ40.

FIGURE 2.

Co-capture of iPrP and Aβ from AD mouse brains. Co-capture of iPrP and Aβ was conducted with brain homogenates from two 2-month-old and two 18-month-old APP transgenic mice. PrP was probed with 6D11 and was detectable in both young and old mice (upper panel). Monomeric (Mon.) and oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species were probed with 6E10 and were detectable only in older mice (lower panel).

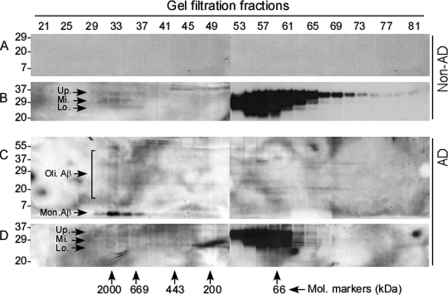

Co-elution of iPrP and Aβ in Human AD Brains

Because of our findings in the brain of the APP transgenic mouse model of AD, we decided to confirm these findings in the brains of AD patients using gel filtration. First, we analyzed PrP and Aβ in brain homogenates from non-AD controls. As shown previously (17), brains from individuals free of prion infection accumulate iPrP (Fig. 3B). As expected, these brains did not contain Aβ aggregates (Fig. 3A). In contrast, monomeric and oligomeric Aβ species were detected in brain samples of AD patients in those fractions that contained large protein aggregates including iPrP (fractions 33–37) (Fig. 3, C and D). Because Aβ aggregates were only detected in AD, but not in non-AD brains, the co-purified Aβ could be Aβ42 rather than Aβ40. Thus, as in the AD mouse model, PrP and Aβ42 aggregates may form complexes in the human AD brain.

FIGURE 3.

Size distribution of PrP and Aβ from brains of AD patients. Brain homogenates from normal controls and AD patients were subjected to gel filtration. Monomeric (Mon.) and oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species were detected with 6E10 in the gel fractions 33–37 containing aggregates ranging from 2,000 to 669 kDa, which were observed only in the AD brain samples (A and C). Western blotting of PrP probed with 6D11 exhibits the presence of PrP aggregates from both control and AD brains in the same 33–37 fractions (B and D) that also contained Aβ aggregates (C). Up., PrP upper band; Mi., PrP middle band; and Lo., PrP lower band.

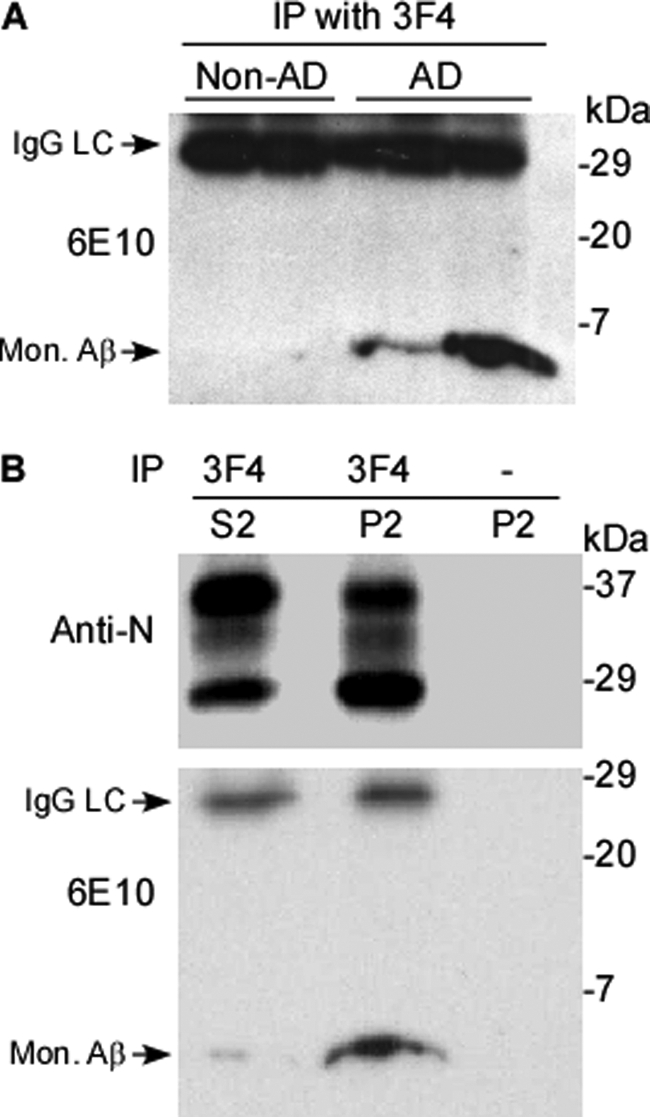

Aβ Co-immunoprecipitates with HuPrP

After co-elution of PrP and Aβ42 aggregates from human AD brains, we next asked whether huPrP binds to Aβ in AD brains by performing a co-immunoprecipitation assay. This method has been widely used to determine whether in vivo binding occurs between the protein of interest and other protein(s). To perform co-immunoprecipitation assays, control and AD brain homogenates were incubated with the 3F4 anti-PrP monoclonal antibody conjugated to beads and the subsequently eluted proteins were analyzed on Western blots probed with the anti-Aβ monoclonal antibody 6E10. The 3F4 immunoprecipitates contained Aβ in two AD cases, but no signal appeared in two non-AD control cases (Fig. 4A). Thus, Aβ is associated with huPrP aggregates only in AD patients, suggesting that certain Aβ conformers typical of AD preferentially bind to PrP. Because AD brains are characterized by increases in Aβ42, again the Aβ conformer co-immunoprecipitated with PrP is most likely Aβ42. Our finding using a peptide membrane array that affinity of Aβ42 for PrP was higher than that of Aβ40 further supports this possibility.

FIGURE 4.

Co-immunoprecipitation of PrP and Aβ by 3F4 from AD brains. A, preparations were obtained by immunoprecipitation with 3F4 from P2 fractions of two non-AD controls and two AD cases. Aβ was detected by Western blotting probed with 6E10 only in AD samples. B, preparations immunoprecipitated by 3F4 from S2 and P2 fractions from AD brains were probed with an antibody against the N terminus of PrP (Anti-N, upper panel) or anti-Aβ antibody 6E10 (lower panel). Most Aβ was detected in P2, whereas only a small amount was present in S2. No signal was observed in P2 incubated with empty beads conjugated with no 3F4 antibody. The nonspecific LC of IgG was also detected in the 6E10 blots migrating at ∼29 kDa.

It has been demonstrated that there are soluble and insoluble forms of PrP and Aβ in human brains (1, 17). To more precisely define whether specific Aβ isoforms are associated with specific PrP conformers, total AD brain homogenates (S1) were further separated into detergent-soluble (S2) and detergent-insoluble (P2) fractions by ultracentrifugation. The S2 and P2 fractions were immunoprecipitated using 3F4-conjugated beads prior to Western blotting with 6E10 and anti-N. As expected, huPrP was immunoprecipitated from both S2 and P2 (Fig. 4B, upper panel). Consistent with our previous observations (17), the insoluble PrP recovered in P2 displayed a dominant unglycosylated PrP band, whereas soluble PrP recovered in S2 exhibited a dominant diglycosylated PrP band. In contrast to PrP, Aβ was mainly detected in P2, although a faint band was detected in S2, accounting for ∼5% of the total Aβ recovered (Fig. 4B, lower panel). As a control, beads free of antibody did not precipitate PrP or Aβ (Fig. 4B). Therefore, more than 95% Aβ was recovered in the insoluble fraction where it mainly interacted with PrP isoforms with the molecular signature of iPrP. The remaining 5% Aβ was soluble and interacted with soluble PrPC. The co-immunoprecipitation of PrP and Aβ observed in both insoluble and soluble fractions indicates that the association between PrP and Aβ is specific.

Co-capture of iPrP and Aβ42 in Human Brains

The finding that iPrP and Aβ42 were co-captured by g5p from the brains of APP transgenic mice suggested that the insoluble moieties of huPrP and Aβ were the major species contributing to the complexes in vivo. To confirm this specific binding in the human brain homogenates, we performed g5p capture of iPrP. As expected, g5p captured huPrP isoforms that were predominantly unglycosylated (Fig. 5A, upper panel), consistent with the glycoform ratio of iPrP (17). In the preparation captured by g5p from brain homogenates of AD patients, we also detected a band migrating at ∼4 kDa corresponding to Aβ42 on Western blots probed with 6E10 (Fig. 5A, lower panel). In addition, a smear was also detected above 4 kDa, suggesting that Aβ42 oligomers may be captured by g5p. Neither PrP nor Aβ were detected in the preparations captured by the beads free of g5p (Fig. 5A). Therefore, Aβ42 indeed binds insoluble PrP in the brains of AD patients.

FIGURE 5.

Co-capture of iPrP and Aβ by g5p from AD brains. A, brain homogenates from AD patients were captured by magnetic beads with (+) or without (−) g5p prior to Western blotting with 3F4 (upper panel) or 6E10 (lower panel). Three PrP bands were detected by 3F4 with the electrophoretic profile of iPrP (dominant unglycosylated PrP). A band migrating at ∼4 kDa and smear bands between 7 and 110 kDa were detected by the 6E10 antibody corresponding to monomeric (Mon.) and oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species, respectively (lower panel). PrP and Aβ were not detected in the preparations captured by the beads conjugated with no g5p. B, S1, S2, and P2 fractions from non-AD and AD brains were subjected to g5p capture prior to Western blotting with 6E10. Monomeric (Mon.) and oligomeric (Oli.) Aβ species were captured by g5p in S1 and P2, but not in S2 of AD brain samples. In contrast, no Aβ was captured in non-AD brain samples. C, capture of synthetic Aβ42 spiked in PrP-free lysis buffer (LB) by g5p. Different amounts of synthetic Aβ42 spiked in lysis buffer were captured by g5p prior to Western blotting with 6E10. Synthetic Aβ42 (40 ng) directly loaded onto the gel was used to as a control (−). No Aβ was captured by g5p up to 80 ng of Aβ42. D, different amounts of synthetic Aβ42 spiked in PrP-containing brain homogenates (BH) of wild type mice were captured by g5p prior to Western blotting with 6E10. Aβ was detected in the samples captured by g5p containing 20 ng of Aβ42 or higher.

It is well known that Aβ42 is prone to form soluble oligomers and insoluble aggregates (1). We next assessed whether the Aβ42 captured by g5p was soluble or insoluble by fractionation of the AD brain homogenates as detailed above. The S1, S2, and P2 fractions were incubated with g5p for capture of iPrP prior to Western blotting with 6E10. As expected, no Aβ42 was detected in either fraction in non-AD control samples (Fig. 5B). In contrast, Aβ42 was detected in S1 and P2 in the AD brain extracts, but was virtually undetectable in S2 (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the Aβ species that bind iPrP are present mainly in the detergent-insoluble fraction.

To determine whether Aβ capture by g5p is through direct binding of g5p to Aβ or through interaction between g5p and PrP, we conducted g5p capture of synthetic Aβ42 that was spiked either in PrP-free lysis buffer or in the PrP-containing wild type mouse brain homogenate. When spiked in lysis buffer, Aβ42 was not captured even up to 80 ng of Aβ42 (Fig. 5C). In contrast, when spiked in the PrP-containing brain homogenate, Aβ42 was captured even as low as 20 ng of Aβ42 (Fig. 5D). These results indicated that g5p does not bind to Aβ42 directly. As a result, Aβ capture by g5p most likely results from the PrP-Aβ42 complex formed in the AD brain.

Identification of Aβ42 and Aβ40 Binding Sites on HuPrP

The above results clearly indicate that Aβ42 binds to huPrP in the AD brain. To further dissect the Aβ binding sites on huPrP, we designed and synthesized a peptide membrane array containing 99 13-mer peptides that span the complete mature sequence of huPrP. Membrane-bound peptide arrays have been used previously to identify Tau-Aβ interaction sites (27). Using this method, we determined the Aβ42 binding sites on human PrP in vitro. In addition, as a control, we also determined Aβ40 binding sites on huPrP, to distinguish oligomer- from monomer-specific binding domains; Aβ42 has been demonstrated to have a greater tendency to form oligomers than Aβ40.

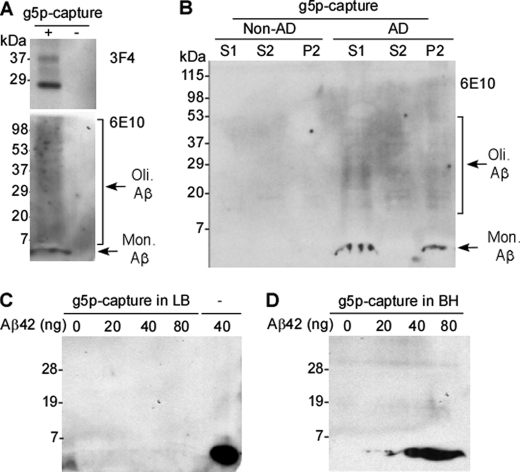

Prior to performing binding assays, we characterized the physicochemical and morphological properties of the Aβ42 and Aβ40 preparations used in peptide membrane arrays. To do this, both samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with the 6E10 antibody. Whereas Aβ40 produced a single band migrating at ∼4 kDa, the Aβ42 preparation exhibited not only a band migrating at ∼4 kDa, but also a ladder containing multiple bands migrating above 4 kDa, a sign of oligomers and higher aggregates (Fig. 6A). By densitometric analysis, we analyzed the amount of Aβ42 that migrated above 4 kDa on the Western blots. The oligomeric forms of Aβ42 accounted for ∼20% of total Aβ42, whereas polymeric Aβ40 was virtually undetectable by Western blotting (<1%) (Fig. 6B). These samples were also examined by electron microscopy. Negatively stained samples of Aβ42 exhibited a mixture of small and mature fibrils 19 nm in diameter (Fig. 6C). In contrast, no fibrils were detected in the Aβ40 sample; there were some amorphous structures (Fig. 6D). Thus, the Aβ42 preparation contained a mixture of aggregates of different lengths that appear consistent with the pathological accumulation of Aβ42 in the brain, whereas Aβ40 showed poor aggregation under the same condition.

FIGURE 6.

Physicochemical and morphological features of the synthetic Aβ42 and Aβ40 used for peptide membrane arrays. A, the synthetic Aβ42 and Aβ40 peptides dissolved in PBS were subjected to SDS-PAGE and detected by Western blotting with 6E10. In the Aβ42 preparation, a dominant band migrating at ∼4 kDa corresponding to monomeric (Mon.) Aβ42 and smear bands migrating >4 kDa corresponding to Aβ42 oligomers (Oli.) were detected. In contrast, only a dominant band migrating at ∼4 kDa corresponding to Aβ40 was detected in the Aβ40 preparation. B, quantitative analysis of the Aβ peptide bands on three Western blots at ∼4 or >4 kDa up to 115 kDa by densitometric analysis. Approximately 20% of Aβ42 formed polymers, whereas virtually no polymeric Aβ40 was detectable by Western blotting (<1%). C and D, electron micrographs of negatively stained images of Aβ42 (C) exhibit mature fibrils 19 nm in diameter (arrow head) in different lengths, whereas Aβ40 (D) shows less organized structure. Scale bar, 100 nm.

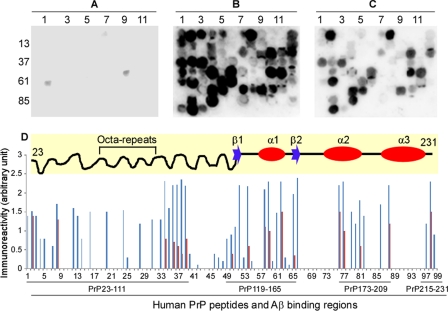

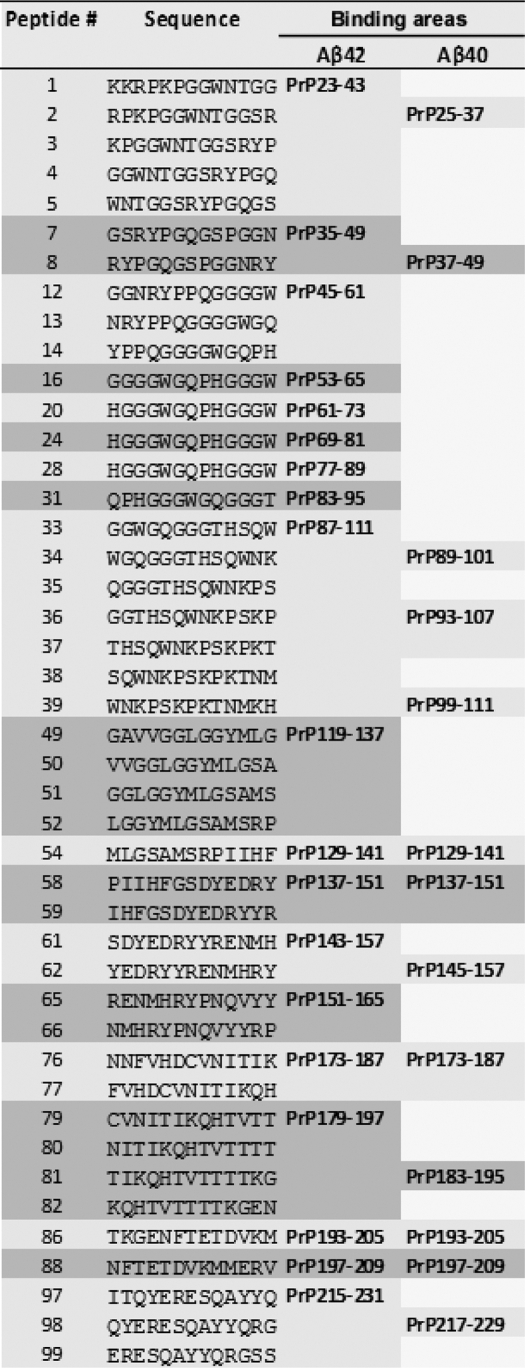

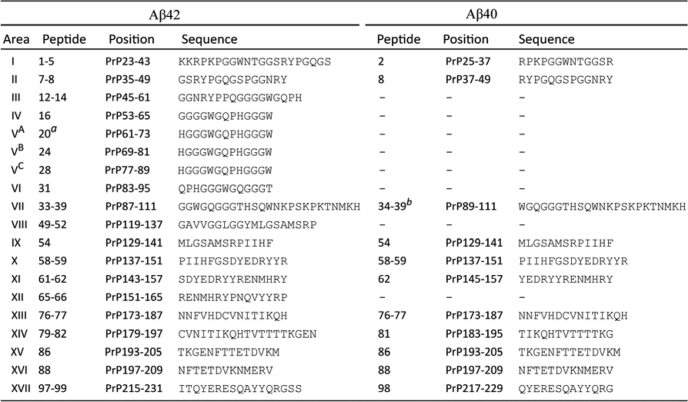

Before incubating the membrane array with Aβ40 and Aβ42, we performed a control with BSA (no Aβ, Fig. 7A) or without the 4G8 anti-Aβ antibody (not shown). These experiments showed no reactivity (Fig. 7A), indicating the specificity of the assay. In the binding assays for Aβ42, 44 huPrP 13-mers exhibited strong immunoreactivity with 4G8 (Fig. 7B and Tables 1 and 2). These interactions were highly reproducible in triplicate assays (Fig. 7D). The 44 Aβ42 binding peptides were distributed in 17 PrP regions, mainly clustered in the unfolded N-terminal domain, including huPrP23–111 (binding areas 1–7) (Fig. 7B and Tables 1 and 2). Other clusters of binding peptides were located in PrP119–165, PrP173–209, and PrP215–231 (Fig. 7D and Tables 1 and 2). The PrP119–165 region contains the two β-strands and α-helix 1 (28) (Fig. 7D, the diagram in the top panel). PrP173–209 and PrP215–231 are mainly localized in α-helix 2 and α-helix 3, including the loop between the two α-helices (Fig. 7D, top panel, and Tables 1 and 2) (28). As an internal control for the sensitivity and specificity of the binding array, three peptides (numbers 20, 24, and 28) of identical sequence located in the octapeptide repeats (HGGGWGQPHGGGW) demonstrated consistent immunoreactivity with Aβ42 (Fig. 7B and Tables 1 and 2). In contrast, four peptides (numbers 17, 21, 25, and 29) of identical sequence (GGWGQPHGGGWGQ) and three other peptides (numbers 19, 23, and 27) of identical sequence (QPHGGGWGQPHGG), also located in the octapeptide repeats, exhibited no immunoreactivity (Fig. 7B and Tables 1 and 2). These results further increased our confidence in the specificity of peptide arrays.

FIGURE 7.

PrP binding of synthetic Aβ42 and Aβ40 binding on 13-mer huPrP peptide membrane arrays. A–C, Aβ reactivity with huPrP peptides. Ninety-nine 13-mer PrP peptides, spanning the entire mature huPrP sequence (residues 23–231), were synthesized on the cellulose membranes. Immunoreactivity of 99 PrP peptides was probed with 4G8 after incubation with BSA (A), Aβ42 (B), and Aβ40 (C). BSA was used as a negative control. D, relative immunoreactivity of each huPrP 13-mer from 3 independent experiments. Aβ42 is shown in blue and Aβ40 in red. Upper panel, diagram of the NMR-derived secondary huPrP structure (28). According to the NMR study of recombinant huPrP, PrP contains an unstructured N-terminal domain from residues 23 to 124 (a wavy line) and a folded C-terminal domain extending from residues 125–228 (a straight line). The two β-strands are shown as blue arrows, located from residues 128–131 and 161–163. The three α-helices are shown as red ovals, located from residues 144–154, 173–194, to 200–218. The octapeptide repeats are indicated.

TABLE 1.

Sequences of PrP peptides reacting with Aβ42 or Aβ40

TABLE 2.

Binding areas of Aβ42 and Aβ40 on human PrP

a Peptides 20, 24, and 28 have the same sequence and exhibited similar reactivity with Aβ42.

b Peptides 34, 36–37, and 39 but not peptides 35 and 38 exhibited reactivity with Aβ40 between PrP residues 89 and 111.

Compared with Aβ42, Aβ40 reacted with fewer huPrP peptides (17 versus 11) and exhibited weaker signals with the positives (Fig. 7, B and C, and Tables 1 and 2). Five Aβ42 binding areas (huPrP129–141, 137–151, 173–187, 193–205, and 197–209) exhibited reactivity with both Aβ peptides albeit at lower intensity with Aβ40 than with Aβ42. The two Aβ peptides exhibited immunoreactivity with six PrP regions that had a slight variation in amino acid sequences between Aβ42 and Aβ40. However, six Aβ42 binding areas, localized mostly in the N-terminal unstructured domain, had no reactivity with Aβ40 (huPrP45–61, 53–65, 61–73, 83–95, 119–137, and 151–165) (Fig. 7, B and C, and Tables 1 and 2), suggesting that the N-terminal PrP binding domain is highly Aβ42-specific. The two types of Aβ42 binding sites on PrP may result from the unique conformation of its oligomeric state.

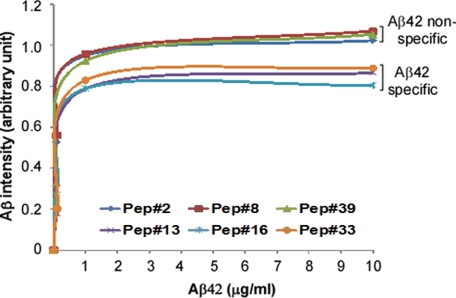

We compared the binding affinity of Aβ42-specific (only reacting with Aβ42) and nonspecific (reacting with both Aβ42 and Aβ40) PrP peptides. Using synthetic Aβ42 at 0, 0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 μg/ml on the peptide membrane arrays, we examined the Aβ binding affinities of three Aβ42-specific PrP peptides, including peptides 13 (PrP47–59), 16 (PrP53–65), and 33 (PrP87–99); as well as three Aβ42 nonspecific peptides, including peptides 2 (PrP25–37), 8 (PrP37–49), and 39 (PrP99–111) from the N-terminal domain of PrP. The intensity of Aβ42 binding at different concentrations to PrP peptides was quantified by densitometric analysis. The resulting binding affinity curves were a function of the affinity of huPrP peptides for Aβ42 (Fig. 8). Based on the curves, the Kd50 value (Aβ42 concentration at the half-maximal binding) was calculated for each PrP peptide. Notably, the mean Kd50 of Aβ42-specific PrP peptides was significantly greater than that of Aβ-nonspecific peptides (0.287 versus 0.083 μg/ml, p = 0.0062 < 0.01) (Fig. 8), indicating that the affinity of Aβ42 for its specific PrP binding areas was lower than that of Aβ42 for its nonspecific binding areas.

FIGURE 8.

PrP binding affinity of synthetic Aβ42 for huPrP peptides. The binding affinity of synthetic Aβ42 for three Aβ42-specific (reacting with Aβ42 only including peptides 13, 16, and 33) and three Aβ42 nonspecific (reacting with both Aβ42 and Aβ40 including peptides 2, 8, and 39) PrP peptides at the N-terminal domain was measured by peptide membrane arrays. The intensity of Aβ42 at 0, 0.1, 1.0, and 10.0 μg/ml bound to PrP peptides were quantified by densitometric analysis. The binding affinity curves were a function of the affinity of huPrP peptides for Aβ42. The Kd50 value for each PrP peptide was calculated based on the curves. The mean Kd50 of Aβ42-specific PrP peptides is significantly greater than that of Aβ42-nonspecific PrP peptides (0.287 versus 0.083 μg/ml, p = 0.0062 < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

The remarkable hypothesis that PrPC may act as a receptor for Aβ42 and play a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD has triggered great interest in the fields of Alzheimer and prion diseases while raising high hopes for finding a cure for AD (3, 9). The evidence supporting this new hypothesis is based on two fundamental observations: the direct binding of Aβ42 to PrP and the potential pathophysiological role of PrP in Aβ42 neurotoxicity in different AD models. Several groups have independently confirmed the binding of Aβ42 to PrP, leaving no question as to the high specificity of this interaction (9, 12, 16). On the other hand, the pathophysiological role of PrP in Aβ42 pathobiology seems more controversial (15, 29). Three independent studies failed to replicate such a role for PrP in various AD models using Prnp−/− mice (12–14). These conflicting results may be largely attributable to differences in experimental conditions, including AD models and outcomes for Aβ42 neurotoxicity (LTP, spatial memory, object recognition). Moreover, the use of Prnp−/− animals can lead to confounding effects, including compensatory changes where other protein(s) may replace the function of PrPC. Indeed, Laurén and co-workers (9) observed that PrPC was not the only cell-surface molecule that binds to Aβ42 oligomers because it accounted for only ∼50% of Aβ42 binding. Thus, animals lacking PrP might not be the best models for assessing the role of PrP in the pathophysiology of Aβ42. Our assumption is supported by the recent study of Wisniewski and co-workers (30) who observed that the antibody-based interruption of the binding of PrP to Aβ42 by intraperitoneal injection of the 6D11 antibody improved behavior and memory in an AD animal model, which is consistent with our own preliminary data.3 These last two studies agree with the observation by Laurén and co-workers (9) that the binding site of Aβ42 is the 6D11 antibody epitope (murine PrP 93–109). Conceivably, interference of Aβ42 binding to PrP may represent not only a more appropriate method to assess the role of PrP in the pathogenesis of AD, but also a therapeutic strategy for AD.

Yet, despite these promising findings, very little evidence emerged to demonstrate the relevance of these observations to humans. The motivation for our study was precisely to provide such evidence, specifically evidence for the binding of Aβ42 to PrP in the human brain. We present seven novel observations. First, large PrP and Aβ particles are recovered in the same gel filtration fractions from AD brains of patients. Second, over 95% of Aβ co-immunoprecipitated by 3F4 from AD brain samples is insoluble, whereas less than 5% of Aβ is soluble. Third, Aβ is co-captured with iPrP by g5p from AD brains, in a PrP-dependent format. Fourth, there are six Aβ42-specific binding regions on huPrP. Fifth, four of six Aβ42-specific binding areas are localized in the octapeptide repeat region of the unfolded N-terminal domain, whereas only one is located in the folded C-terminal domain between residues 151 and 165. The other Aβ42-specific binding area is located between the unfolded N- and folded C-terminal domains (residues 119 to 137). Sixth, compared with its nonspecific binding PrP areas, the affinity of Aβ42 for its specific binding area is significantly lower. Finally, the oligomeric state or conformation of Aβ42 and Aβ40 may determine the affinity of the two Aβ peptides for huPrP. Cumulatively, these findings indicate that Aβ42 may bind to huPrP in the AD brain and that there are two types of Aβ binding sites on huPrP: the oligomer- (Aβ42-specific) and monomer-specific (Aβ42-nonspecific) binding sites. Furthermore, our findings carry important implications regarding the pathophysiological consequences of Aβ/PrP interaction.

Our study with 13-mer peptides confirmed the high affinity of Aβ42 for different binding domains on huPrP. Moreover, the Aβ42 preparation we used contained a mixture of monomers, oligomers, and fibrils, of which, oligomers and fibrils may have a much higher ability to interact with huPrP than the Aβ40 preparation that contained mainly monomers but not oligomers and fibrils (Figs. 7 and 8). Based on the different affinity of huPrP peptides for the two Aβ peptides with distinct oligomeric states, the huPrP domains can be grouped into two types of Aβ binding sites (Tables 1 and 2). The first group specifically binds to Aβ42, which may be oligomer-specific. These binding sites are mainly distributed in the N-terminal unstructured region. For instance, four of six Aβ42-specific binding sites (binding areas III through VI) are localized in the octapeptide repeat region of the unstructured N-terminal domain (Tables 1 and 2), including sites identified by Laurén and co-workers (9). In particular, the HGGGWGQPHGGGW peptide, which is repeated three times in the octapeptide domain, revealed strong binding activity to Aβ42. The octapeptide domain (residues 51–91) is comprised of four octapeptides and one nonapeptide. This domain contains at least four copper binding sites and may be involved in copper metabolism and transport to synapses as well as cellular defense mechanisms against oxidative stress (31–34). It is possible that the binding of Aβ42 to this domain interrupts the physiological interaction of PrP with copper, resulting in disturbed neuronal communication. In contrast to the observations of Laurén and co-workers (9), we also identified two additional Aβ42-specific binding sites. One (binding area VIII) was detected in the conjunction area (PrP119–137) between the N-terminal unfolded and the C-terminal folded domains (Tables 1 and 2). The other (binding area XII) is localized in the folded C-terminal domain. This second group binds indiscriminately to both Aβ42 and Aβ40, which may be monomer-specific and are mainly localized in the extremely N-terminal domain and C-terminal folded domain. The lower affinity of Aβ42 for the octapeptide repeat domain suggests that the PrP physiological function may also be affected when Aβ42 is significantly increased in AD.

However, these Aβ binding sites on huPrP identified in vitro may not faithfully reflect the behavior of brain-derived PrP; therefore, this observation should be established and validated by in vivo studies, especially given that the glycosylation and folding of the C-terminal region of PrP may affect the corresponding binding sites. Nevertheless, the results obtained with short synthetic peptides might still be relevant given the presence of several endogenously truncated PrP fragments in vivo including N1, N2, C1, and C2 (21, 35, 36). It would be interesting to determine whether these endogenous small PrP fragments participate in interactions with Aβ42 in vivo. Moreover, the identified broadest PrP area to which both Aβ42 and Aβ40 bind including peptides 34–39 (Tables 1 and 2 and Fig. 7) contains the binding site identified by two previous independent studies using different methods (9, 16), indicating that this PrP area may be the key Aβ42 binding site. In addition, identification of the Aβ42 binding areas on huPrP may be significant for the development of new therapeutic strategies for AD. For instance, the intracerebral application of small PrP peptides may inhibit interaction between PrP and Aβ42, thereby preventing Aβ42 neurotoxicity.

PrP is a structurally dynamic protein, existing in chameleon-like conformations (37, 38), and the diverse conformations of recombinant PrP may represent an intrinsic molecular spectrum of PrPC in vivo (39). Remarkably, small amounts of insoluble PrP oligomers and polymers are also observed in uninfected human and animal brains (17). These newly identified PrP conformers, which we termed iPrP, account for ∼5–25% of total PrP, including full-length and N-terminal truncated forms. The insoluble PrP can bind to g5p, a single-stranded DNA-binding protein that specifically binds to PrPSc or PrPSc-like conformers (17, 18), suggesting that iPrP possesses a conformation different from that of PrPC but similar to that of PrPSc. However, the physiological or pathophysiological role of iPrP is currently unclear.

Because of the specific or direct binding of Aβ42 to PrP indicated by previous studies (9, 12, 16), as well as our peptide membrane array and co-immunoprecipitation of soluble PrP and Aβ here, it is conceivable that PrP and Aβ42 may bind directly to each other within insoluble complexes. Therefore, it is most likely that the iPrP is the PrP conformer that interacts with the amyloid plaques in vivo. Our finding that Aβ42 binds to iPrP suggests that iPrP plays a role in the fibrillization of Aβ42. In fact, it has been consistently observed that PrP deposits are observed around or throughout Aβ plaques in AD brains (5–7). Interestingly, insoluble PrPSc aggregates also seem to interact with Aβ42 in vivo (40). Soto and co-workers (40) recently reported that an increase in the efficiency of Aβ42 aggregation in vitro was dependent on PrPSc dosage. Similarly, AD mice developed a strikingly higher load of cerebral amyloid plaques that appeared much faster in prion-infected than in uninfected mice. Thus, iPrP (the PrPSc-like forms identified in uninfected human brains) may facilitate fibrillization of Aβ42 in AD. Indeed, synergistic interactions between amyloidogenic proteins associated with neurodegeneration have been demonstrated to promote each others fibrillization, amyloid deposition, and formation of filamentous inclusions in transgenic mice (8, 41). Because this is the case, the possibility must be considered that a significant increase in the total number of Aβ plaques observed in bigenic mice overexpressing PrP (8) might result from an increase in the formation of iPrP. Moreover, because iPrP interacts with insoluble Aβ42, whereas soluble PrPC binds soluble Aβ42 in vivo, it is possible that distinct PrP conformers binding to different Aβ42 species thereby function either as receptors for soluble Aβ42 oligomers or as modulators of insoluble Aβ42 deposition. This hypothesis could be tested by intracerebrally injecting anti-PrP antibodies against either soluble or insoluble PrP species in AD animal models.

The insoluble PrP may also be involved in memory and cognitive processes. It is worth noting that the involvement of protein polymerization in long-term memory has been documented in the last few years. For instance, a neuronal isoform of the cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein, which plays a role in long-term memory by activating translationally dormant mRNA to regulate protein synthesis at the synapse, has been reported to exhibit self-perpetuating prion-like properties in sensory neurons and in yeast (42–44). These studies suggest that prion-like conformational changes may constitute a key event in the maintenance of structural synaptic changes required for long-term memory by acting as molecular “switches” (45, 46). It was proposed that the impact of a putative PrP conformation, rather than the pathological PrPSc, on memory in healthy humans is associated with physiologically occurring conformational changes (47–49). However, whether these changes in the accumulation of iPrP and their ability to seed Aβ42 are responsible for memory impairment remains to be investigated.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful to Dr. Pierluigi Gambetti for helpful comments.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01NS062787 (to W.-Q. Z.), grants from the Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease Foundation (to W.-Q. Z.), Alliance BioSecure (to W.-Q. Z.), the University Center on Aging and Health with the support of the McGregor Foundation and the President's Discretionary Fund (Case Western Reserve University) (to W.-Q. Z.), and the Pacific Alzheimer Research Foundation (to J.-P. G. and P. L. M.).

W.-Q. Zou, G. Casadesus, and H.-G. Lee, unpublished data.

- AD

- Alzheimer disease

- PrPC

- cellular prion protein

- PrPSc

- pathological, scrapie isoform of prion protein

- Aβ

- amyloid β peptide

- g5p

- Fd gene 5 protein

- APP

- amyloid precursor protein

- iPrP

- insoluble PrP

- HC

- heavy chain

- LC

- light chain

- LTP

- long-term potentiation.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hardy J., Selkoe D. J. (2002) Science 297, 353–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Prusiner S. B. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95, 13363–13383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gunther E. C., Strittmatter S. M. (2010) J. Mol. Med. 88, 331–338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Berr C., Helbecque N., Sazdovitch V., Mohr M., Amant C., Amouyel P., Alpérovitch A., Hauw J. J. (2003) Acta Neuropathol. 106, 71–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Esiri M. M., Carter J., Ironside J. W. (2000) Neuropathol. Appl. Neurobiol. 26, 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrer I., Blanco R., Carmona M., Puig B., Ribera R., Rey M. J., Ribalta T. (2001) Acta Neuropathol. 101, 49–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Kovacs G. G., Zerbi P., Voigtländer T., Strohschneider M., Trabattoni G., Hainfellner J. A., Budka H. (2002) Neurosci. Lett. 329, 269–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Schwarze-Eicker K., Keyvani K., Görtz N., Westaway D., Sachser N., Paulus W. (2005) Neurobiol. Aging 26, 1177–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Laurén J., Gimbel D. A., Nygaard H. B., Gilbert J. W., Strittmatter S. M. (2009) Nature 457, 1128–1132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Gimbel D. A., Nygaard H. B., Coffey E. E., Gunther E. C., Laurén J., Gimbel Z. A., Strittmatter S. M. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 6367–6374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Parkin E. T., Watt N. T., Hussain I., Eckman E. A., Eckman C. B., Manson J. C., Baybutt H. N., Turner A. J., Hooper N. M. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 11062–11067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balducci C., Beeg M., Stravalaci M., Bastone A., Sclip A., Biasini E., Tapella L., Colombo L., Manzoni C., Borsello T., Chiesa R., Gobbi M., Salmona M., Forloni G. (2010) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 2295–2300 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Calella A. M., Farinelli M., Nuvolone M., Mirante O., Moos R., Falsig J., Mansuy I. M., Aguzzi A. (2010) EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 306–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kessels H. W., Nguyen L. N., Nabavi S., Malinow R. (2010) Nature 466, E3–4; discussion E4–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Ledford H. (2010) Nature 466, 1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chen S., Yadav S. P., Surewicz W. K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 26377–26383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Yuan J., Xiao X., McGeehan J., Dong Z., Cali I., Fujioka H., Kong Q., Kneale G., Gambetti P., Zou W. Q. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34848–34858 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zou W. Q., Zheng J., Gray D. M., Gambetti P., Chen S. G. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 1380–1385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kascsak R. J., Rubenstein R., Merz P. A., Tonna-DeMasi M., Fersko R., Carp R. I., Wisniewski H. M., Diringer H. (1987) J. Virol. 61, 3688–3693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Zou W. Q., Langeveld J., Xiao X., Chen S., McGeer P. L., Yuan J., Payne M. C., Kang H. E., McGeehan J., Sy M. S., Greenspan N. S., Kaplan D., Wang G. X., Parchi P., Hoover E., Kneale G., Telling G., Surewicz W. K., Kong Q., Guo J. P. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13874–13884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen S. G., Teplow D. B., Parchi P., Teller J. K., Gambetti P., Autilio-Gambetti L. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 19173–19180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chishti M. A., Yang D. S., Janus C., Phinney A. L., Horne P., Pearson J., Strome R., Zuker N., Loukides J., French J., Turner S., Lozza G., Grilli M., Kunicki S., Morissette C., Paquette J., Gervais F., Bergeron C., Fraser P. E., Carlson G. A., George-Hyslop P. S., Westaway D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 21562–21570 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dudal S., Krzywkowski P., Paquette J., Morissette C., Lacombe D., Tremblay P., Gervais F. (2004) Neurobiol. Aging 25, 861–871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Oliver A. W., Bogdarina I., Schroeder E., Taylor I. A., Kneale G. G. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 301, 575–584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo J. P., Petric M., Campbell W., McGeer P. L. (2004) Virology 324, 251–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Yuan J., Dong Z., Guo J. P., McGeehan J., Xiao X., Wang J., Cali I., McGeer P. L., Cashman N. R., Bessen R., Surewicz W. K., Kneale G., Petersen R. B., Gambetti P., Zou W. Q. (2008) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 65, 631–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Guo J. P., Arai T., Miklossy J., McGeer P. L. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 1953–1958 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Zahn R., Liu A., Lührs T., Riek R., von Schroetter C., López García F., Billeter M., Calzolai L., Wider G., Wüthrich K. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 145–150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Benilova I., De Strooper B. (2010) EMBO Mol. Med. 2, 289–290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chung E., Ji Y., Sun Y., Kascsak R. J., Kascsak R. B., Mehta P. D., Strittmatter S. M., Wisniewski T. (2010) BMC Neurosci. 11, 130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Brown D. R., Qin K., Herms J. W., Madlung A., Manson J., Strome R., Fraser P. E., Kruck T., von Bohlen A., Schulz-Schaeffer W., Giese A., Westaway D., Kretzschmar H. (1997) Nature 390, 684–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brown D. R., Schulz-Schaeffer W. J., Schmidt B., Kretzschmar H. A. (1997) Exp. Neurol. 146, 104–112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Del Bo R., Scarlato M., Ghezzi S., Martinelli-Boneschi F., Fenoglio C., Galimberti G., Galbiati S., Virgilio R., Galimberti D., Ferrarese C., Scarpini E., Bresolin N., Comi G. P. (2006) Neurobiol. Aging 27, 770.e1–770.e5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Westergard L., Christensen H. M., Harris D. A. (2007) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1772, 629–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Jiménez-Huete A., Lievens P. M., Vidal R., Piccardo P., Ghetti B., Tagliavini F., Frangione B., Prelli F. (1998) Am. J. Pathol. 153, 1561–1572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mangé A., Béranger F., Peoc'h K., Onodera T., Frobert Y., Lehmann S. (2004) Biol. Cell 96, 125–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zou W. Q., Gambetti P. (2007) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64, 3266–3270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Collinge J., Clarke A. R. (2007) Science 318, 930–936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Zhang H., Stockel J., Mehlhorn I., Groth D., Baldwin M. A., Prusiner S. B., James T. L., Cohen F. E. (1997) Biochemistry 36, 3543–3553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Morales R., Estrada L. D., Diaz-Espinoza R., Morales-Scheihing D., Jara M. C., Castilla J., Soto C. (2010) J. Neurosci. 30, 4528–4535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Giasson B. I., Lee V. M., Trojanowski J. Q. (2003) Neuromol. Med. 4, 49–58 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Si K., Choi Y. B., White-Grindley E., Majumdar A., Kandel E. R. (2010) Cell 140, 421–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Si K., Giustetto M., Etkin A., Hsu R., Janisiewicz A. M., Miniaci M. C., Kim J. H., Zhu H., Kandel E. R. (2003) Cell 115, 893–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Si K., Lindquist S., Kandel E. R. (2003) Cell 115, 879–891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Shorter J., Lindquist S. (2005) Nat. Rev. Genet. 6, 435–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Kandel E. R. (2009) J. Neurosci. 29, 12748–12756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Tompa P., Friedrich P. (1998) Neuroscience 86, 1037–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Papassotiropoulos A., Wollmer M. A., Aguzzi A., Hock C., Nitsch R. M., de Quervain D. J. (2005) Hum. Mol. Genet. 14, 2241–2246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Legname G., Nguyen H. O., Peretz D., Cohen F. E., DeArmond S. J., Prusiner S. B. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 19105–19110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]