Abstract

Interactions between fibronectin and tenascin-C within the extracellular matrix provide specific environmental cues that dictate tissue structure and cell function. The major binding site for fibronectin lies within the fibronectin type III-like repeats (TNfn) of tenascin-C. Here, we systematically screened TNfn domains for their ability to bind to both soluble and fibrillar fibronectin. All TNfn domains containing the TNfn3 module interact with soluble fibronectin. However, TNfn domains bind differentially to fibrillar fibronectin. This distinct binding pattern is dictated by the fibrillar conformation of FN. TNfn1–3, but not TNfn3–5, binds to immature fibronectin fibrils, and additional TNfn domains are required for binding to mature fibrils. Multiple binding sites for distinct regions of fibronectin exist within tenascin-C. TNfn domains comprise a binding site for the N-terminal 70-kDa domain of fibronectin that is freely available and a binding site for the central binding domain of fibronectin that is cryptic in full-length tenascin-C. The 70-kDa and central binding domain regions are key for fibronectin matrix assembly; accordingly, binding of several TNfn domains to these regions inhibits fibronectin fibrillogenesis. These data highlight the complexity of protein-protein binding, the importance of protein conformation on these interactions, and the implications for the physiological assembly of complex three-dimensional matrices.

Keywords: Extracellular Matrix, Fibronectin, Protein Assembly, Protein-Protein Interactions, Tenascin

Introduction

The precise organization of molecules within the complex, three-dimensional extracellular matrix (ECM)2 both defines the physical properties of individual tissues and is a key determinant of cell behavior. Fibronectin (FN) and tenascin-C (TN-C) are secreted glycoproteins that interact within ECM networks to regulate cell morphology, adhesion, migration, and proliferation (1–4). Interactions between these proteins also impact tissue structure by controlling the assembly, maintenance, and turnover of the ECM at the cell surface (2, 5, 6).

FN exists in a number of different forms; cellular FN, ubiquitously synthesized by a wide variety of cells, is assembled into a three-dimensional fibrillar matrix at the cell surface, and plasma FN, synthesized by hepatocytes, circulates in the blood as a soluble dimer (7). Tenascin-C exhibits a tightly restricted expression pattern, spatially and temporally coinciding with fibronectin fibril assembly (5, 8–10). Many independent studies have demonstrated that purified or recombinant TN-C binds directly to purified soluble plasma FN in vitro (1, 11–16). TN-C also binds to FN fibrils in vivo in Pleurodeles waltl spawnings (17) and co-localizes with fibrillar FN matrices assembled by numerous cell types in culture, for example, myogenic cells (18), embryonic fibroblasts (12), and calvarial osteoblasts (19).

Both FN and TN-C are large multimodular proteins composed of distinct functional domains. TN-C comprises an N-terminal association domain, a series of 14.5 epidermal growth factor-like repeats (EGF-L), a series of FN type III-like repeats (TNfn), and a C-terminal fibrinogen-like globe. Binding of TN-C to both soluble, plasma FN and cellular, fibrillar FN is mediated specifically via the TNfn; the N-terminal association domain, EGF-L, and fibrinogen-like globe domains bind to neither form of FN (6, 13). Within these repeats of TN-C, TNfn3 by itself can compete with full-length TN-C for binding to soluble, plasma FN in glycerol sedimentation assays or ELISAs. However, TNfn3–5 was a more effective competitor than TNfn3 alone, whereas TNfn6–8 did not compete. Increasingly larger domains containing the TNfn3–5 module (TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8) exhibited no further inhibition over TNfn3–5 alone (13). Surface plasmon resonance studies also demonstrated that only recombinant proteins containing TNfn3–5 domains (TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8) were able to bind to FN fragments, whereas TNfn6–8 did not. Moreover, TNfn3–5 bound to FN fragments with relatively high affinity, whereas TNfn3 bound only weakly (20). These data indicate the presence of a binding site for soluble, plasma FN within TNfn3 and suggest that neighboring modules 4–5 are required for optimal interactions.

However, not all of the TNfn domains have been analyzed in binding studies. In addition, very little is known about the nature of the interaction of TN-C with cellular, fibrillar FN. Although binding is mediated by contiguously presented modules within the TNfn1–8 domain (13), it is not known specifically which modules within TNfn1–8 are required. Moreover, the binding sites within fibrillar FN for TNfn domains have not been identified. Thus we aimed to more fully understand the interactions between fibronectin and TNfn domains by defining the location of binding site(s) within TNfn domains for fibrillar FN and identifying binding sites within fibrillar FN for TNfn domains. We also determined the effect of TNfn domains on FN matrix assembly into a three-dimensional fibrillar network.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Expression and Purification

Fig. 1 depicts all the proteins and protein domains used in this study. Recombinant full-length human TN-C and TNfn domains TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, TNfn1–8, TNfn5–7, and TNfn6–8 were purified and expressed as described previously (6, 21, 22). Where stated, recombinant TN-C and TNfn domains were fluorescently labeled with an Alexa Fluor 488 dye, and labeling efficiency was determined following the manufacturer's instructions (Molecular Probes, Invitrogen).

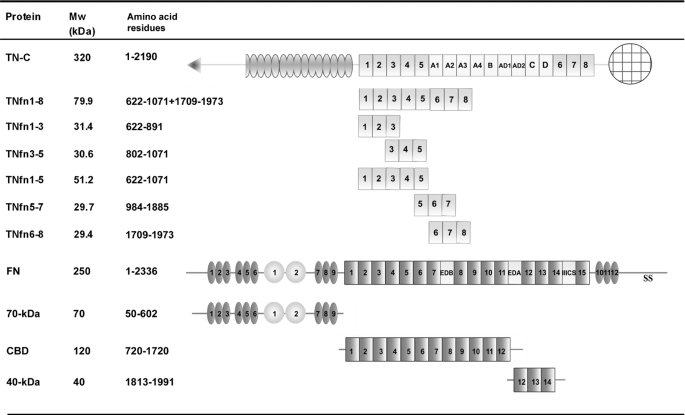

FIGURE 1.

Schematic of TN-C, TNfn domains, and FN and FN fragments. TN-C is composed of an N-terminal association domain (triangle), EGF-L repeats (ovals), conserved TNfn (numbers within light gray boxes), alternatively spliced TNfn (letters within white boxes), and a C-terminal fibrinogen-like globe domain (patterned circle). FN is composed of a series of FNI repeats (numbers within dark gray ovals), FNII repeats (numbers within circles), conserved FNIII repeats (numbers within dark gray boxes), and alternatively spliced FNIII repeats (letters within light gray boxes). Mw (kDa) indicates molecular size in kDa.

Full-length, plasma FN was isolated from human plasma as described previously (23). Soluble cellular FN was obtained by the collection of conditioned medium from NIH3T3 fibroblasts cultured in serum-free DMEM. Medium was concentrated, and FN concentration was determined by dot blotting. The Bio-Dot® SF microfiltration apparatus (Bio-Rad) was used following the manufacturer's instructions. For the standard curve, known concentrations of plasma FN were diluted in TN buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 8.0, and 150 mm NaCl). Samples were applied under suction to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was then removed and incubated in 5% BSA at room temperature for 1 h. The membrane was then probed with anti-FN antibody (F3648, Sigma; 0.7 μg/ml) in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature and secondary alkaline-phosphatase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (S3731, Promega; 1:5000) in 1% BSA for 1 h at room temperature. Bands were visualized with Western blue substrate (Promega), and intensities were determined with Phoretix software (1D version 2003.02, Nonlinear Dynamics). The total pmol of FN present in each sample was then determined by comparing band intensities with the FN standard curve and normalized to the control value.

The 120-kDa central binding domain (CBD; F1904) and 40-kDa domain (HepII; F1903) α-chymotryptic FN fragments were purchased from Chemicon (Millipore). The recombinant human 70-kDa domain (70-kDa) of FN was provided by Jean Schwarzbauer (Princeton University, NJ) (24).

Direct and Competition Solid Phase Binding Assay

To analyze the direct binding of purified plasma FN, soluble cellular FN, and individual FN domains to TN-C and TN-C domains, solid phase binding assays were performed as described previously (6). Briefly, ELISA plates were coated with 78 nm TNfn domains overnight at 4 °C. After washing, increasing concentrations of soluble plasma FN, soluble cellular FN, or FN fragments were applied to ELISA plates and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C. Binding was detected with anti-FN antibody (F3648, Sigma) and secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody.

The immobilization of TNfn domains to ELISA plates was confirmed by Western blotting supernatants decanted from plates after immobilization. Quantification of TNfn domain binding by ELISA using the anti-His4 tag antibody (34670) (Qiagen) or antibodies recognizing specific domains of tenascin-C (MAB1911 and MAB1918) (Millipore) revealed that each TNfn domain bound equally well.

For competition solid phase binding assays, 25 μg/ml human plasma FN was diluted in TBS containing 1 mm CaCl2 and 1 mm MgCl2 and applied to 96-well EIA/RIA flat-bottomed ELISA plates overnight at 4 °C. 0.1 μm TN-C and TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, and TNfn3–5 were preincubated with increasing concentrations of 70-kDa and CBD for 1 h at 37 °C before applying to ELISA plates and incubating for a further 1 h at 37 °C. Binding was detected with MAB1911 (Millipore) and secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody.

Binding to Cellular or Plasma Fibrillar FN

Analysis of the binding of TNfn domains to a mature, fibrillar, endogenously synthesized cellular FN matrix assembled by NIH3T3 fibroblasts was performed as described previously (6). Briefly, cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105/ml and cultured for 24 h before incubation with 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn domains for a further 1, 4, or 8 h. Where stated, TNfn domains were preincubated for 30 min at 37 °C with increasing concentrations of FN domains (70-kDa or CBD) before addition to the matrix.

To analyze binding of TNfn domains to a fibrillar plasma FN matrix, CHOα5 cells, which synthesize no endogenous cellular FN, were used (provided by Jean Schwarzbauer). Cells were plated at a density of 4 × 105/ml for 2 h before the addition of 50 μg/ml human plasma FN and cultured for 22 h (as described by Refs. 25 and 26) before incubating with 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn domains for a further 8 h.

Cells were fixed, stained using the anti-fibronectin antibody (F3648, Sigma; 3.5 μg/ml), and mounted. High magnification images (×60 and ×100 oil lenses, Nikon) were captured by confocal microscopy (Ultraview Nipkow scanning disc Nikon TE2000-U confocal microscope and Hamamatsu A3472-07 camera) and processed with Volocity® three-dimensional imaging software (PerkinElmer Life Sciences).

To assess TNfn domain binding to FN during matrix assembly, NIH3T3 cells were plated at 4 × 105/ml and cultured for 2 h before the addition of 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn domains. Cells were incubated for a further 2, 4, 8, or 22 h, at which time points the FN matrix was stained and images were taken as above.

Assessment of FN Matrix Assembly

NIH3T3 fibroblasts were plated at a density of 4 × 105/ml for 2 h before the addition of 1.0, 0.1, or 0.01 μm TNfn domains directly to the medium. Cells were then further incubated for up to 22 h before immunofluorescence or DOC solubility assays were carried out as described below.

Immunofluorescence

Cells were fixed and stained for FN as described previously (6). To visualize nuclei, cells were permeabilized with in 0.2% Triton X-100 (VWR International) for 10 min at room temperature before incubating with DAPI (Sigma; 1:300) for 30 min at 37 °C. Controls were stained in the absence of primary antibody to demonstrate no background binding by the secondary antibody. Cell density was assessed by phase microscopy and DAPI nuclear staining, and only areas with equivalent cell densities were imaged. Images were taken by confocal microscopy as described above. Fluorescence pixel intensity was quantified as described previously (6). A one-way analysis of variance (non-parametric) analysis was applied to the data using the Dunnett's post test (*, p < 0.05, **, p < 0.01).

DOC Solubility Assay

The amount of FN assembled into a DOC-insoluble matrix was carried out as described previously (6). Briefly, after washing with PBS, NIH3T3 fibroblasts were lysed with 200 μl of DOC lysis buffer (2% (w/v) DOC, 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm protease inhibitor, 2 mm iodoacetic acid, 2 mm N-ethylmaleimide). Cell lysate was passaged through a 26-gauge hypodermic needle before spinning at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet containing DOC-insoluble material was resolubilized in 25 μl of SDS-containing buffer (1% (w/v) SDS, 25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 2 mm EDTA, 2 mm protease inhibitor, 2 mm iodoacetic acid, 2 mm N-ethylmaleimide) and heated at 100 °C for 5 min.

For Western blotting, protein concentration was determined, and 6 μg of DOC-insoluble material was resolved on 6% polyacrylamide gels, which were Western blotted and probed with an anti-FN antibody (F3648, Sigma; 0.7 μg/ml) and secondary HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (NA9340V, Amersham Biosciences; 1:5000). Bands were visualized with ECL substrate (Amersham Biosciences). To ensure that the same amount of protein was loaded onto each gel, the detergent-soluble fraction was resolved and probed with an anti-tubulin antibody (Sigma, TS8328; 1:5000) and secondary HRP-conjugated anti-mouse antibody (NA9310V, Amersham Biosciences; 1:5000). Bands were scanned, and band intensities quantified with Phoretix 2D software (Nonlinear Dynamics Ltd.).

For dot blotting, the total FN in DOC-insoluble material was determined by dot blotting as described above. DOC-insoluble samples were diluted in TN buffer to ensure that samples were within the linear range.

RESULTS

Soluble Fibronectin Interacts with Tenascin-C Domains Possessing the TNfn3 Module

Domains TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8 of TN-C have been shown to bind to soluble FN, whereas TNfn6–8 did not bind (13, 20). However, neither study examined domains TNfn1–3 or TNfn5–7. We synthesized a panel of overlapping TNfn domains spanning the entire length of TNfn1–8 (TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn5–7, and TNfn6–8) (Fig. 1) and systematically screened these together with TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–5 for binding to soluble, plasma FN. Using solid phase binding assays, the interaction of increasing concentrations of purified human plasma FN with immobilized TNfn domains was assessed. Consistent with published data, TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, and TNfn3–5 bound to FN in a specific and saturable manner, and TNfn6–8 showed minimal binding. We also report for the first time that TNfn1–3 was able to bind to FN but that TNfn5–7 was not. These data also demonstrate that TNfn1–3 and TNfn1–5 exhibit increased binding to soluble FN when compared with TNfn3–5 and TNfn1–8 (Fig. 2).

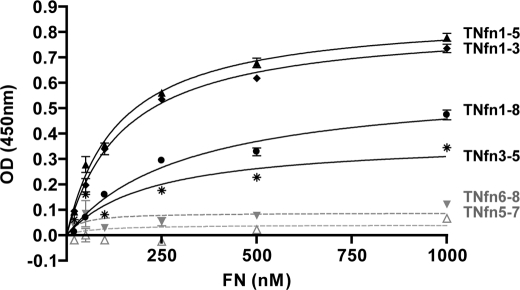

FIGURE 2.

TNfn domains containing TNfn3 can bind to soluble plasma FN. Solid phase binding assays demonstrating the interaction of increasing concentrations of soluble human plasma FN with 78 nm immobilized TNfn domains are shown: TNfn1–8 (solid line with filled circles), TNfn1–3 (solid line with filled diamonds), TNfn3–5 (solid line with stars), TNfn1–5 (solid line with filled triangles), TNfn5–7 (dashed line with open triangles), and TNfn6–8 (dashed line with inverted gray triangles). Data are representative of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate (± S.E.).

We also performed the reverse binding assays to determine the interaction of increasing concentrations of soluble TNfn domains with FN-coated plates to preclude the possibility that TNfn5–7 and TNfn6–8 may be immobilized in a manner that masks any FN binding sites. Here, as above, we found that TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8 bound to FN, but TNfn5–7 and TNfn6–8 did not (data not shown).

Tenascin-C Contains Multiple Binding Sites for Distinct Domains of Soluble Fibronectin

The binding sites in soluble FN for TNfn domains were mapped using individual domains of FN: the N-terminal 70-kDa and the CBD (Fig. 1). In direct solid phase binding assays, TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, TNfn1–3, and TNfn3–5 bound in a specific and saturable manner to both 70-kDa and CBD. Each protein bound equally well to 70-kDa and CBD with the exception of TNfn1–8, which showed reduced binding to CBD (Fig. 3, A and B). TNfn6–8, included as a negative control, exhibited no binding to either FN fragment (Fig. 3, A and B). We were unable to determine the interactions of the 40-kDa (HepII) domain of FN with TNfn domains because this FN fragment exhibited high nonspecific binding in our hands (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

TNfn domains containing TNfn3 can bind to the 70-kDa domain and CBD of FN, but these FN domains can only partially compete with TNfn3 binding to soluble plasma FN. A and B, solid phase binding assays showing the interaction of increasing concentrations (conc) of 70-kDa and CBD with 78 nm immobilized TNfn domains: TNfn1–8 (solid line with circles), TNfn1–3 (solid line with filled diamonds), TNfn3–5 (solid line with stars), TNfn1–5 (solid line with filled triangles), and TNfn6–8 (dashed line with gray inverted triangles). Data are representative of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate (± S.E.). OD, optical density. C–E, competition solid phase binding assays to determine the effect of preincubating increasing concentrations of 70-kDa (solid line with filled circles), CBD (solid line with open circles), or TNfn6–8 (solid line with Xs) on the interaction of 0.1 μm TNfn3–5 (C), TNfn1–5 (D), or TNfn1–8 (E) with 25 μg/ml immobilized plasma FN; FN domains (FN-f) were preincubated with TN-C and TN-C domains for 1 h at 37 °C. Binding of TN-C or TNfn domains to immobilized plasma FN was detected with an anti-TNfn1–3 antibody (MAB1911) and secondary HRP-conjugated antibody. Results were normalized to 100% FN binding levels. Data are representative of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate (± S.E.). F and G, binding curves were plotted on a log scale to directly compare the competitive effect of increasing concentrations of the FN domains on TNfn3–5 (solid line with stars), TNfn1–5 (solid line with filled triangles), TNfn1–8 (solid line with filled circles), and full-length TN-C (solid line with filled squares) binding to 25 μg/ml immobilized FN. Data are representative of two independent experiments each performed in triplicate (± S.E.).

FN fragments were also used in competition binding assays. TNfn domains were preincubated with increasing concentrations of 70-kDa or CBD before assessing binding to immobilized FN. Incubation with 50-fold molar excess of 70-kDa partially inhibited TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8 binding to FN by 64, 69, and 46%, respectively (Fig. 3, C, D, E, and F). Incubation with 50-fold molar excess of CBD also partially inhibited binding of TNfn3–5 and TNfn1–5 by 66 and 63%, respectively, and inhibited TNfn1–8 binding to FN by 39% (Fig. 3, C, D, E, and G). To confirm that inhibition was not due to the presence of high protein concentrations sterically hindering protein-protein interactions with full-length FN, excess TNfn6–8 was preincubated with TNfn1–5 and did not interfere with TNfn1–5 binding to immobilized FN (Fig. 3D). The antibody used to detect TNfn domains in this assay did not recognize TNfn1–3 (data not shown), so this domain had to be excluded from these studies. We and others have previously demonstrated that full-length TN-C binds to FN (6, 11–16). Here we show that this interaction is inhibited by competition with 70-kDa but not with CBD (Fig. 3, F and G).

Together these data indicate that TN-C interacts with more than one domain within FN. 70-kDa can bind to TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, TNfn1–8, and full-length TN-C, and the CBD can bind to TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, and TNfn1–5 but shows reduced interaction with the larger TNfn1–8 domain and full-length TN-C. The absence of complete inhibition of binding of TNfn domains to FN by either 70-kDa or CBD also indicates that multiple fibronectin binding sites exist within TNfn domains.

The TNfn3 Module Is Not Sufficient for Binding to Fibrillar Fibronectin

Having examined the interaction of the TNfn domains of tenascin-C with soluble plasma FN, we next investigated the binding of these domains to fibrillar FN. TNfn domains were fluorescently labeled and incubated with NIH3T3 fibroblasts. These cells elaborate a FN matrix at the cell surface (Fig. 4 (−)) but do not synthesize endogenous TN-C (13).3 Cells were cultured in the presence of 0.1 μm of each TNfn domain over time up to 24 h and any localization to the fibrillar FN matrix followed by immunofluorescent microscopy.

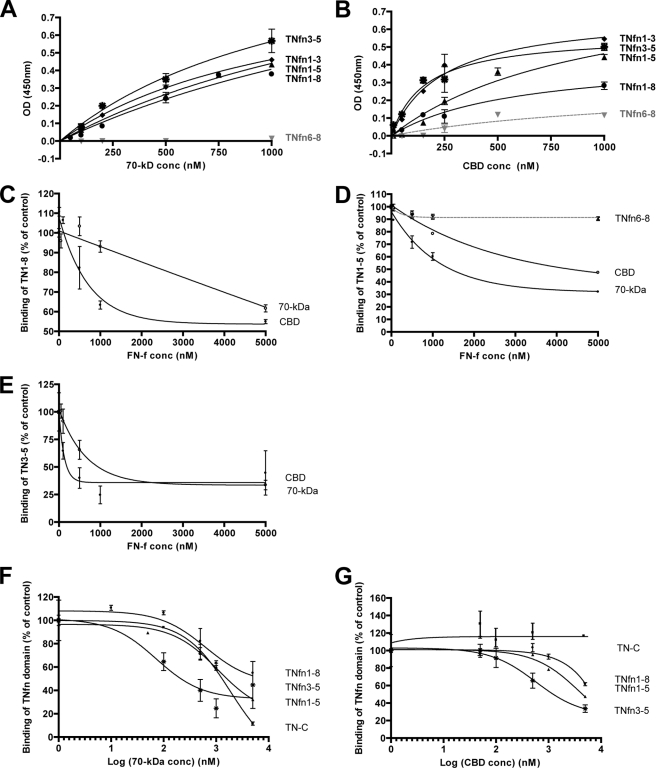

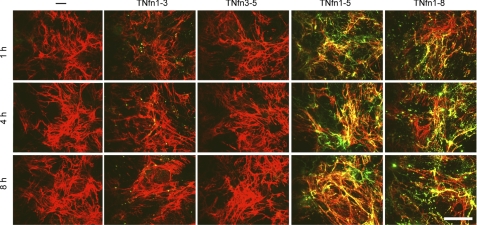

FIGURE 4.

TNfn domains demonstrate differential patterns of localization during cellular FN fibril assembly. Immunofluorescent staining demonstrating the localization of 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8 when compared with NIH3T3 cells cultured in the absence of recombinant protein (−) is shown. Cells were plated for 2 h (0 h) before the addition of Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TN-C or TNfn domains and incubated for a further 2, 4, 8, and 22 h before fixing and staining with an anti-FN antibody (F3648); Bar, 25 μm. Magnified images (Zoom) depict clearer images of the FN fibrillar structure (control and TNfn3–5 after a 22-h incubation) and co-localization of fluorescent TNfn1–3 (after a 4-h incubation) and TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 (after a 22-h incubation). Bar, 25 μm.

TNfn1–3 bound to the developing FN matrix after a 2-h incubation with the cells (not shown), exhibiting punctate co-localization with FN fibrils as well as some FN-independent staining. This interaction peaked at 4 h but was reduced by 8 and 22 h (Fig. 4 (TNfn1–3)). In contrast, TNfn3–5 exhibited no binding to fibrillar FN at any time point (Fig. 4 (TNfn3–5)). Likewise, neither TNfn5–7 nor TNfn6–8 bound to fibrillar FN, nor did full-length TN-C (not shown), as described previously (13). TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 both bound to the FN matrix early in the assembly process; punctate localization along thin FN fibrils was observed after a 2-h incubation with the cells and increased as the fibrils developed over time (Fig. 4 (TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–5)). These domains showed different co-localization patterns. TNfn1–5 was distributed continuously along the length of the FN fibrils, whereas TNfn1–8 exhibited a more disrupted fibrillar co-localization pattern. FN-independent TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 staining was also observed, with TNfn1–8 showing a more punctate staining pattern, whereas TNfn1–5 highlighted more fibrillar structures. These data demonstrate that domains TNfn1–3, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8 can bind to fibrillar FN in addition to soluble FN. In contrast, whereas TNfn 3–5 can bind to soluble FN, it does not bind to fibrillar FN.

Mapping TNfn Binding Sites within the Fibrillar Fibronectin Matrix

To further investigate the interaction of TNfn domains with FN fibrils, NIH3T3 cells were cultured for 24 h to allow the assembly of a complex, mature FN matrix on the cell surface before the addition of fluorescently labeled TNfn domains and further incubation for 1, 4, or 8 h. TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 exhibited increasing binding to the FN fibrils within the assembled matrix over time. Again, TNfn1–5 showed a more continuous co-localization along the mature FN fibrils, whereas TNfn1–8 showed more punctate co-localization (Fig. 5). TNfn1–5 also stained FN-independent fibrillar structures (Fig. 5). TNfn1–3 exhibited little co-localization to the FN fibrils, even after an 8-h culture with a mature FN matrix (Fig. 5). TNfn3–5 (Fig. 5) and TNfn5–7 and TNfn6–8 (not shown) also did not bind to fibrillar FN. These data further highlight the differences in the ability of TNfn domains to bind FN. Although TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–3 all bind to immature FN fibrils formed during the early stages of fibrillogenesis, TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 can also bind to mature fibrils, whereas TNfn1–3 cannot.

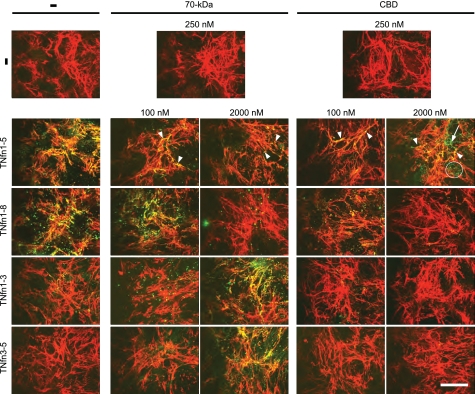

FIGURE 5.

TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 co-localize to an endogenous cellular fibrillar FN matrix. Immunofluorescent staining of a mature FN matrix assembled by NIH3T3 cells for 24 h and then cultured for a further 1, 4, or 8 h in the absence (−) or presence of 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn1–8, TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, TNfn5–7, or TNfn6–8 is shown. Bar, 25 μm.

To determine which domains of fibrillar FN can bind to TNfn domains, the 70-kDa and CBD fragments were preincubated with TNfn domains before incubation with a fibrillar FN matrix. Preincubation of TNfn1–8 with equimolar concentrations of 70-kDa had no effect on TNfn1–8 binding to the FN matrix, but incubation with 20-fold excess 70-kDa ablated TNfn1–8 co-localization to FN fibrils. Preincubation of TNfn1–8 with equimolar CBD reduced TNfn1–8 binding to the FN matrix, with complete inhibition observed in the presence of 20-fold excess CBD (Fig. 6). Preincubation of TNfn1–5 with equimolar or excess concentrations of either 70-kDa or CBD partially inhibited TNfn1–5 binding to FN fibrils (Fig. 6). Preincubation of TNfn1–3 or TNfn3–5 with CBD had no effect on the localization of these domains; however, preincubation of excess 70-kDa resulted in the recruitment of both domains to the FN matrix, where they bound in a continuous pattern along the length of the fibrils (Fig. 6).

FIGURE 6.

TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–5 bind to 70-kDa and CBD within cellular, fibrillar FN, whereas TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 bind only to cellular, fibrillar FN in the presence of excess 70-kDa. Immunofluorescent staining of a mature FN matrix assembled for 24 h by NIH3T3 cells and then cultured for a further 1 h in the absence (−) or presence of 100 nm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn1–8, TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, or TNfn1–5 without (−) or with preincubation for 1 h with equimolar (100 nm) or excess (2000 nm) concentrations of FN domains 70-kDa or CBD is shown. To confirm that the FN domains had no effect on the structure of the mature FN matrix, 250 nm 70-kDa and CBD were incubated with the mature matrix alone for 1 h (−). Bar, 25 μm. Arrowheads denote co-localization of TNfn and FN; arrow denotes fibrillar TNfn staining.

Together these data demonstrate that TNfn1–8 can interact with multiple binding sites within FN fibrils, including 70-kDa and CBD, but that this domain may only bind to one of these sites at a time. Similarly, multiple binding sites exist and are accessible within the 70-kDa and CBDs for TNfn1–5 binding, but in contrast, TNfn1–5 can bind to multiple FN binding sites at the same time. These results also suggest that binding sites for TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 present in soluble FN are not exposed in the three-dimensional fibrillar structure of the FN matrix but that TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 can be recruited to the fibrillar FN via interactions with 70-kDa, which itself can bind to FN.

The Fibrillar Organization of FN Dictates TNfn Domain Interactions

The isoforms of FN present in plasma are different from cellular forms of FN; plasma FN does not possess the extra domain B (EDB) or extra domain A (EDA) alternatively spliced domains, and only one subunit of the FN dimer possesses an IIICS (variable) domain (27–29). Hence, we wanted to determine whether the differential binding of TNfn domains to cellular FN fibrils when compared with immobilized soluble plasma FN was due to the presence of alternatively spliced FN modules or mediated by the different structural organization of each type of FN.

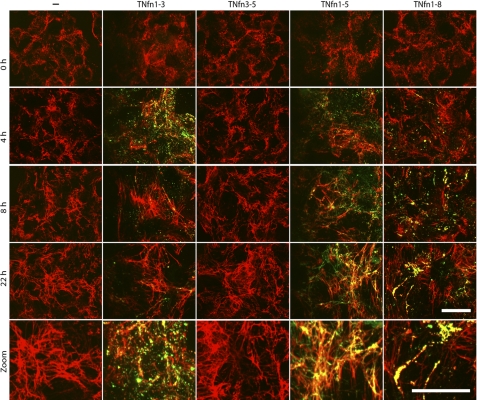

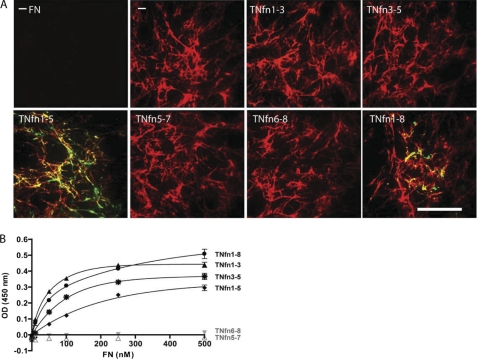

To determine whether TNfn domains can interact with three-dimensional fibrillar plasma FN as well as three-dimensional fibrillar cellular FN, CHOα5 cells were used that do not synthesize, secrete, or assemble endogenous FN (25) (Fig. 7A (−-FN)) but can assemble an FN matrix in the presence of exogenously supplied plasma FN (25, 26) (Fig. 7A (−). Fluorescently labeled TNfn domains were incubated with CHOα5 cells after they had been allowed to assemble a fibrillar plasma FN matrix. TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 interacted with fibrillar plasma FN assembled by CHOα5 cells (Fig. 7A) in a similar manner to fibrillar cellular FN assembled by NIH3T3 fibroblasts (Fig. 5). TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn5–7, and TNfn6–8 did not bind to a mature plasma fibrillar matrix (Fig. 7A) as observed for a mature cellular fibrillar FN (Fig. 5).

FIGURE 7.

TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 can co-localize to a fibrillar plasma FN matrix, and domains containing TNfn3 can bind to soluble cellular FN. A, immunofluorescent staining of a plasma FN matrix assembled by CHOα5 cells supplied with 50 μg/ml human plasma FN for 24 h with a further 8-h culture in the absence (−) or presence of 0.1 μm Alexa Fluor 488-labeled TNfn1–8, TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, TNfn5–7, or TNfn6–8. In the absence of exogenously supplied human plasma FN, no FN matrix is assembled by these cells (−FN). Bar, 50 μm. B, solid phase binding assays showing the interaction of increasing concentrations of soluble cellular FN with 78 nm immobilized TNfn domains: TNfn1–8 (solid line with filled circles), TNfn1–3 (solid line with filled diamonds), TNfn3–5 (solid line with stars), TNfn1–5 (solid line with filled triangles), TNfn5–7 (dashed line with open triangles), and TNfn6–8 (dashed line with inverted gray triangles). Data are shown as an average of triplicate repeats (± S.E.). OD, optical density.

The binding of secreted, non-fibrillar cellular FN to TNfn domains was also assessed by solid phase binding. Cellular FN in serum-free conditioned medium was collected from NIH3T3 fibroblasts. Increasing concentrations of cellular FN showed specific and saturable binding to immobilized TNfn1–3, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–8, but not TNfn5–7 or TNfn6–8 (Fig. 7B), similar to binding observed with soluble plasma FN (Fig. 2). These data indicate that the differential binding patterns of TNfn3-containing TN-C domains to FN in its fibrillar form versus its immobilized soluble form are not due to the presence of different isoforms of FN but rather due to the different physical structures of FN.

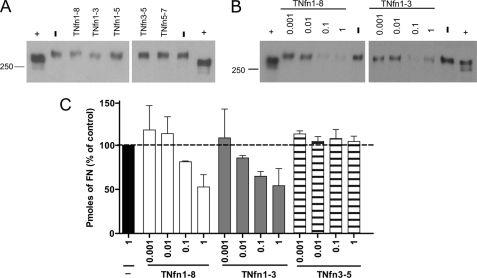

TNfn1–3 and TNfn1–8 Can Inhibit Fibronectin Matrix Assembly

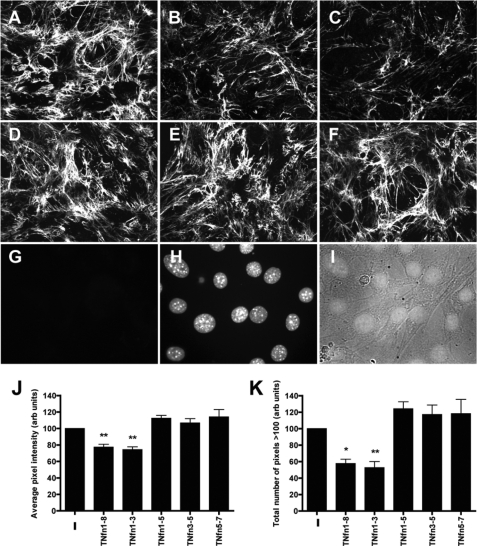

FN matrix assembly is a stepwise process whereby soluble, compact FN binds to the cell surface and induces cytoskeletal changes and integrin clustering, resulting in the unfolding of the FN into an extended conformation that can then interact with further FN molecules (30). The ability of TNfn domains to interact with FN via 70-kDa and the CBD, regions that are vital in mediating FN-FN intermolecular interactions or FN-cell receptor interactions, respectively, during matrix assembly, implies that TNfn domains may also affect FN fibrillogenesis. We have previously shown that TNfn1–8 can inhibit FN matrix assembly (6). Here, we wanted to establish whether binding of FN fibrils by TNfn domains confers the ability to interfere with FN matrix assembly. We examined the effect of TNfn domains that can bind both to soluble and to fibrillar FN (TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, and TNfn1–3) or TNfn domains that bind only to soluble FN (TNfn3–5) on FN matrix assembly. TNfn5–7 was included as a negative control not able to bind to any form of FN tested. When compared with cells cultured in the absence of TNfn domains (Fig. 8A), TNfn1–8 (Fig. 8B) and TNfn1–3 (Fig. 8C) caused a reduction in FN matrix complexity, density, and fibril length and thickness. In contrast, TNfn3–5 (Fig. 8D), TNfn1–5 (Fig. 8E), and TNfn5–7 (Fig. 8F) had no effect on FN matrix deposited by these cells. Quantification of fluorescence demonstrated that the fibrillar thickness (average pixel intensity; Fig. 8J) and fibrillar density (total number of pixels above threshold pixel intensity of 100; Fig. 8K) were significantly reduced after culture of cells with TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–3 but not in the presence of TNfn1–5, Tnfn3–5, and TNfn5–7.

FIGURE 8.

TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–3 inhibit FN matrix assembly. A–I, immunofluorescent staining showing the effect of 0.1 μm TNfn1–8 (B), TNfn1–3 (C), TNfn3–5 (D), TNFn1–5 (E), and TNfn5–7 (F) on FN matrix assembly when compared with NIH3T3 cells in the absence of recombinant protein (A). Cells were plated for 2 h before the addition of the TNfn domains and incubated for a further 22 h before fixing and staining with an anti-FN antibody (F3648). As a background control, cells were fixed and stained without primary antibody (G). Immunofluorescence images were taken from regions of similar cell densities as confirmed by DAPI staining (H) and phase microscopy (I) of the cell nuclei. J and K, quantification of immunofluorescence images to determine the average pixel intensity and total pixel intensities above a background threshold value. Three random fields of view from three independent experiments were quantified and normalized to controls cultured in the absence of recombinant protein (−). Data are shown as the mean ± S.E. (*, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01). arb units, arbitrary units.

As FN is assembled, it becomes incorporated into the three-dimensional complex matrix on the cell surface, which is detergent-insoluble (31). Culture of cells with TNfn1–3 and TNfn1–8 resulted in a loss of FN incorporated into the DOC-insoluble matrix, whereas TNfn3–5, TNfn1–5, and TNfn5–7 had no effect (Fig. 9A). This effect was shown to be dose-dependent by both Western blotting and dot blotting of the DOC-insoluble material (Fig. 9, B and C) when compared with and normalized to the controls (−). Together these data demonstrate that TNfn domains TNfn1–3 and TNfn1–8 specifically inhibit the assembly of FN into a fibrillar matrix on the cell surface of fibroblasts.

FIGURE 9.

TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–3 reduce the level of fibronectin assembled into the DOC-insoluble matrix. A and B, Western blots showing FN levels in detergent (DOC)-insoluble material isolated from NIH3T3 cells cultured for 24 h in the presence of 0.1 μm TNfn1–8, TNfn1–3, TNfn1–5, TNfn3–5, or TNfn5–7 (A) or increasing concentrations of TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–3 (B) or in the absence of recombinant protein (−). Human plasma FN was included as a positive control (+). Blots shown are representative of results from three independent experiments. Molecular mass markers are in kDa. C, DOC-insoluble material isolated from cells cultured for 24 h in the presence of increasing concentrations of TNfn1–8, TNfn1–3, or TNfn3–5 or in the absence of recombinant protein (−) was dot blotted, and the total pmol of FN present in the samples was determined by comparing band intensities with a standard curve of known FN concentrations. Blots shown are representative of results from three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

The ordered interaction of molecules within the ECM creates an amazingly diverse range of physical structures. ECM networks also deliver specific environmental signals to resident cells to regulate their behavior. Here, we examined the interaction of the ubiquitously expressed FN with TN-C, a key modulator of cell response to FN.

We identified novel domains of TN-C that interact with FN and showed that these domains exhibit different binding to three-dimensional fibrillar FN matrices than to soluble, non-fibrillar forms of FN. TNfn1–8, TNfn1–5, TNfn1–3, and TNfn3–5 interacted with immobilized soluble plasma FN, but TNfn5–7 and TNfn6–8 did not. This is consistent with data showing TNfn3 to be the only consensus module present in all FN binding TNfn domains in the subset of TNfn modules hitherto analyzed (TNfn1–5, TNfn3–5, TNfn1–8, and TNfn6–8) (13, 20). In contrast, despite binding to soluble FN, TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 did not bind to mature cellular, fibrillar FN, although TNfn1–3 did co-localize with immature, developing fibrils early in fibrillogenesis. The larger domains, TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–5, bound to newly synthesized FN fibrils in addition to a mature FN matrix.

These data may suggest the presence of binding sites for TN-C in plasma FN that are not available in cellular FN. The modular content of each form of FN may determine its binding capabilities. Plasma FN lacks three alternatively spliced repeats: EDA, EDB, and the variable (IIICS) region, that are present in cellular FN (7). The absence of these domains may reveal cryptic TN-C binding sites by modulating plasma FN conformation. The inclusion of EDB has been shown to alter the angle of the interdomain interface between the neighboring FNIII7-FNIII8 modules (32). In addition, neighboring FN type III domains affect both the exposure of loop sequences at module interfaces (33) and the mobility and torsional constraints of interdomain regions (34). However, here we show that TNfn domains TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 showed similar co-localization patterns to three-dimensional matrices of plasma FN as those observed with cellular FN matrices. Similarly, TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 did not localize to the fibrillar organization of plasma FN. This suggests that the different isoforms of FN are not affecting the TNfn domain localization to fibrils. Furthermore, soluble (non-fibrillar) cellular FN and plasma FN could bind to all TNfn3-containing domains in solid phase binding assays, suggesting that the different isoforms of FN do not affect TNfn binding, but rather, it is the presentation and supramolecular organization of FN that may be dictating TNfn binding site availability.

Cellular FN that is assembled into higher order fibrils exhibits a conformation quite distinct to that adopted by FN adsorbed to a planar surface. Immobilization often confers conformations on ECM proteins that obscure or expose binding sites (35, 36). For example, extensive TN-C-FN interactions occur in glycerol gradients (13), where the extended conformation of FN favors TN-C binding (37). Conversely, FN binds poorly to TN-C immobilized on ELISA plates, whereas TN-C binds significantly to immobilized FN (11–13, 15). Thus the ability of TNfn3–5, for example, to interact with immobilized FN but not fibrillar FN may be explained by the exposure of specific binding sites upon protein adsorption to an ELISA plate, which are masked in the three-dimensional fibrillar assembly.

The assembly of FN into a three-dimensional network has also been shown to mediate changes in binding site availability. Many studies demonstrate the exposure of cryptic FN binding sites during fibril formation. FN interaction with cell surface receptors mediates unfolding of the type III modules. This exposes charged residues usually buried within the β barrel fold of the module and enables their interaction with neighboring FN molecules. As fibrils grow, further intermolecular binding sites are unmasked that allow fibril elongation and cross-linking (38–43). Thus FN conformation within immature FN fibrils differs from that in a mature matrix, and these dynamic conformational changes may also conceal or reveal TN-C binding sites as the matrix develops. TNfn1–3 may only be able to bind to specific FN binding sites exposed during the assembly process and not within the mature matrix, whereas binding sites for TNfn1–5 and TNfn1–8 may be accessible or exposed even when FN is assembled into a three-dimensional fibrillar structure.

The specific modular content of TNfn domains is also key in regulating interactions with FN. Although TNfn1–5 bound well to mature fibrillar FN, smaller modules TNfn1–3 and TNfn3–5 exhibited no binding. These data suggest that cooperativity between individual TNfn domains promotes interactions with a three-dimensional FN matrix. TNfn3 alone has been shown to bind to soluble FN; however, the presence of TNfn4–5 increases the affinity of this interaction (20). This synergy may be mediated in a number of different ways. A single FN binding site in TNfn3 may be improved by the presence of neighboring domains, either by their direct involvement in binding or indirectly via optimization of domain conformation. Alternatively, additional and distinct FN binding sites may exist in each individual TNfn domain.

The ability of non-contiguous charged sequences or contribution of multiple weak binding sites to combine to form strong binding has been previously demonstrated for interactions of heparin within TNfn4–5 (44, 45). Similarly, heparin binding by FN, which has been mapped to the FNIII13 module, also depends on the cooperation of multiple discontinuous resides within a “cationic cradle” structure (44). We found that TNfn domains bind to both the 70-kDa domain and the CBD within FN. We also found that multiple binding sites for FN domains exist throughout the TN-C molecule; incomplete inhibition of TNfn1–5 binding to FN by competition with either 70-kDa or CBD indicates that TNfn1–5 can interact with both regions of FN simultaneously. These data support the hypothesis that multiple FN binding sites exist in TNfn domains; however, further systematic analysis of individual TNfn modules is required to definitively prove or refute this theory.

In addition to promoting FN binding, our data suggest that the presence or absence of neighboring TNfn modules can also negatively affect FN binding. TNfn1–8 exhibited poorer binding to both soluble and fibrillar FN than TNfn1–5, suggesting that modules TNfn6–8 block FN binding. Indeed, we found that some of the FN binding sites are cryptic in full-length TN-C. The 70-kDa binding site was freely available in full-length TN-C and all TNfn domains studied, whereas the CBD binding site was obscured in TNfn1–8 and full-length TN-C. Complete inhibition of TNfn1–8 binding to FN fibrils by competition with 70-kDa and CBD also indicates that, unlike TNfn1–5, TNfn1–8 cannot bind to both sites simultaneously. The distinct patterns of fibril binding of TNfn1–5 (continuous along fibril length) and TNfn1–8 (discontinuous, punctate) may result from these differences in binding site availability. Together these data indicate that TNfn6–8 and other domains of TN-C increasingly obscure FN binding sites that are exposed in TNfn1–5. This is consistent with reports that larger TN-C isoforms comprising all of the alternatively spliced repeats exhibit lower affinity for soluble FN when compared with smaller TN-C isoforms (12, 13).

Finally, we observed that TNfn1–8 and TNfn1–3 specifically inhibited FN matrix assembly. Binding of both these domains to immature FN fibrils may block key FN-cell receptor interactions and intermolecular FN-FN interactions early in FN fibrillogenesis. Conversely, the ability of TNfn1–5 to bind to different domains within FN simultaneously suggests that it may be able to interact with neighboring FN fibrils to cross-link the matrix without adversely affecting fibrillogenesis. Lack of binding to fibrillar FN by TNfn3–5 would explain why this domain did not inhibit FN matrix assembly, despite being able to bind to plasma FN.

These data highlight the complexity of multimodular protein-protein interactions within multifaceted ECMs and reveal the importance of domain composition and conformation on binding site availability. Further deciphering how the constituents of the three-dimensional ECM interact with each other is essential to understanding the influence the ECM exerts on cellular processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Hideaki Nagase for advice and discussions of this work. We also thank Jean Schwarzbauer (Princeton University, NJ) for supplying the 70-kDa FN domain and CHOα5 cells, Gertraud Orend (INSERM, Strasbourg, France) for providing the TN-C construct, and Annette Trébaul and Emma Chan for assistance with protein purification.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

W. S. To and K. S. Midwood, unpublished observations.

- ECM

- extracellular matrix

- FN

- fibronectin

- TNfn

- fibronectin type III-like repeat(s)

- CBD

- central binding domain

- TN-C

- tenascin-C

- EGF-L

- epidermal growth factor-like repeat(s)

- DOC

- deoxycholate

- ED

- extra domain.

REFERENCES

- 1. Ghert M. A., Qi W. N., Erickson H. P., Block J. A., Scully S. P. (2001) Cell Struct. Funct. 26, 179–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Midwood K. S., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell. 13, 3601–3613 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Orend G., Huang W., Olayioye M. A., Hynes N. E., Chiquet-Ehrismann R. (2003) Oncogene 22, 3917–3926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wenk M. B., Midwood K. S., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2000) J. Cell Biol. 150, 913–920 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ramos D. M., Chen B., Regezi J., Zardi L., Pytela R. (1998) Int. J. Cancer 75, 680–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. To W. S., Midwood K. S. (2010) Matrix Biol. 29, 573–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pankov R., Yamada K. M. (2002) J. Cell. Sci. 115, 3861–3863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kusubata M., Hirota A., Ebihara T., Kuwaba K., Matsubara Y., Sasaki T., Kusakabe M., Tsukada T., Irie S., Koyama Y. (1999) J. Invest Dermatol. 113, 906–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Latijnhouwers M. A., Bergers M., Van Bergen B. H., Spruijt K. I., Andriessen M. P., Schalkwijk J. (1996) J. Pathol. 178, 30–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Whitby D. J., Ferguson M. W. (1991) Development 112, 651–668 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Kalla P., Pearson C. A., Beck K., Chiquet M. (1988) Cell 53, 383–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chiquet-Ehrismann R., Matsuoka Y., Hofer U., Spring J., Bernasconi C., Chiquet M. (1991) Cell. Regul. 2, 927–938 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chung C. Y., Zardi L., Erickson H. P. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 29012–29017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chung C. Y., Erickson H. P. (1997) J. Cell. Sci. 110, 1413–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Hoffman S., Edelman G. M. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 84, 2523–2527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lightner V. A., Erickson H. P. (1990) J. Cell. Sci. 95, 263–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Riou J. F., Shi D. L., Chiquet M., Boucaut J. C. (1990) Dev. Biol. 137, 305–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chiquet M., Fambrough D. M. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 98, 1926–1936 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kii I., Nishiyama T., Li M., Matsumoto K., Saito M., Amizuka N., Kudo A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2028–2039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Erickson H. P. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 28132–28135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lange K., Kammerer M., Hegi M. E., Grotegut S., Dittmann A., Huang W., Fluri E., Yip G. W., Götte M., Ruiz C., Orend G. (2007) Cancer. Res. 67, 6163–6173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Midwood K., Sacre S., Piccinini A. M., Inglis J., Trebaul A., Chan E., Drexler S., Sofat N., Kashiwagi M., Orend G., Brennan F., Foxwell B. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 774–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Atha D. H. (1990) Biochem. J. 272, 605–611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Schwarzbauer J. E. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 113, 1463–1473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Sechler J. L., Takada Y., Schwarzbauer J. E. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 134, 573–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Sechler J. L., Rao H., Cumiskey A. M., Vega-Colón I., Smith M. S., Murata T., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2001) J. Cell Biol. 154, 1081–1088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Magnusson M. K., Mosher D. F. (1998) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 18, 1363–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tressel T., McCarthy J. B., Calaycay J., Lee T. D., Legesse K., Shively J. E., Pande H. (1991) Biochem. J. 274, 731–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilson C. L., Schwarzbauer J. E. (1992) J. Cell Biol. 119, 923–933 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mao Y., Schwarzbauer J. E. (2005) Matrix Biol. 24, 389–399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. McKeown-Longo P. J., Mosher D. F. (1983) J. Cell Biol. 97, 466–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bencharit S., Cui C. B., Siddiqui A., Howard-Williams E. L., Sondek J., Zuobi-Hasona K., Aukhil I. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 367, 303–309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Spitzfaden C., Grant R. P., Mardon H. J., Campbell I. D. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 265, 565–579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Altroff H., Schlinkert R., van der Walle C. F., Bernini A., Campbell I. D., Werner J. M., Mardon H. J. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 55995–56003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Narasimhan C., Lai C. S. (1989) Biochemistry 28, 5041–5046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ugarova T. P., Zamarron C., Veklich Y., Bowditch R. D., Ginsberg M. H., Weisel J. W., Plow E. F. (1995) Biochemistry 34, 4457–4466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Rocco M., Carson M., Hantgan R., McDonagh J., Hermans J. (1983) J. Biol. Chem. 258, 14545–14549 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chen Y., Wu Y., Cai J. (2007) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 361, 391–397 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Craig D., Krammer A., Schulten K., Vogel V. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 5590–5595 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gao M., Craig D., Lequin O., Campbell I. D., Vogel V., Schulten K. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 14784–14789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hocking D. C., Smith R. K., McKeown-Longo P. J. (1996) J. Cell Biol. 133, 431–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Ingham K. C., Brew S. A., Huff S., Litvinovich S. V. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 1718–1724 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Morla A., Zhang Z., Ruoslahti E. (1994) Nature 367, 193–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Busby T. F., Argraves W. S., Brew S. A., Pechik I., Gilliland G. L., Ingham K. C. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 18558–18562 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Jang J. H., Hwang J. H., Chung C. P., Choung P. H. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 25562–25566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]