Abstract

Mutations within MYO7A can lead to recessive and dominant forms of inherited hearing loss. We previously identified a large pedigree (referred to as the HL2 family) with hearing loss that first impacts the low and mid frequencies segregating a dominant MYO7A mutation in exon 17 at DNA residue G2164C. The MYO7AG2164C mutation predicts a nonconservative glycine-to-arginine (G722R) amino acid substitution at a highly conserved glycine residue. The degree of low and mid frequency hearing loss varies markedly in the family, suggesting the presence of a genetic modifier that either rescues or exacerbates the primary MYO7AG2164C mutation. Here we describe a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) T/C at position −4128 in the wild-type MYO7A promoter allele that sorts with the degree of hearing loss severity in the pedigree. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis indicates that the SNP differentially regulates the binding of the YY1 transcription factor with the T−4128 allele creating an YY1 binding site. Immunocytochemistry demonstrates that Yy1 is expressed in hair cell nuclei within the cochlea. Given that Myo7a is also expressed in cochlear hair cells, Yy1 shows the appropriate localization to regulate Myo7a transcription within the inner ear. YY1 appears to be acting as a transcriptional repressor as the MYO7A promoter allele containing the T−4128 SNP drives 41 and 46% less reporter gene expression compared with the C−4128 SNP in the ARPE-19 and HeLa cell lines, respectively. The T−4128 SNP may be contributing to the severe hearing loss phenotype in the HL2 pedigree by reducing expression of the wild-type MYO7A allele.

Keywords: Gene Expression, General Transcription Factors, Genetic Diseases, Genetic Polymorphism, Human Genetics, Transcription Regulation, Transcription Repressor, Auditory

Introduction

Large human pedigrees segregating monogenic syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing loss have led to the discovery of >50 genes harboring mutations underlying the sensory deficient within the pedigree (see the Hereditary Hearing Loss homepage on the Internet). Mutations within myosin VIIA (MYO7A)2 can lead to both syndromic and nonsyndromic hearing impairment in humans. MYO7A is expressed in the retina, testis, lung, kidney, and inner and outer hair cells of the cochlea (2). In hair cells, MYO7A is found in the actin-rich stereocila bundles, cuticular plate, pericuticular necklace, and cell body (3). MYO7A is also expressed in both type I and type II hair cells of the semicircular canals and utricle (3).

Syndromic MYO7A mutations are inherited in a recessive fashion, leading to a diagnosis of Usher type 1B (USH1B), a disease characterized by profound, congenital, sensorineural deafness with progressive retinitis pigmentosa leading to visual loss and vestibular areflexia. Nonsyndromic MYO7A mutations can be inherited in either a recessive (DFNB2, the 2nd autosomal recessive deafness locus identified) or dominant (DFNA11, the 11th autosomal dominant deafness locus identified) manner. Five DFNA11 mutations have been characterized: p.delA886-K887-K888 in a Japanese pedigree (4); p.G772R in an American pedigree (5); N458I in a Dutch pedigree (6); p.R853C in a German pedigree (7); and p.A230V in an Italian pedigree (8).

We previously mapped the large hearing-impaired DFNA11 American pedigree (referred to as HL2, for hearing loss family 2) to the long arm of chromosome 11 in band 13.5. A MYO7A mutation in exon 17 at DNA residue G2164C was discovered in the HL2 family. The MYO7AG2164C alteration leads to a predicted nonconservative glycine-to-arginine (G772R) amino acid substitution at a highly conserved glycine residue (5). The MYO7AG2164C mutation is unique as it was the first alteration in MYO7A associated with the uncommon clinical finding of progressive low frequency hearing loss (5). We previously showed that the degree of low and mid frequency hearing loss within the HL2 family varies markedly (Fig. 1), suggesting the presence of a genetic modifier that either rescues or exacerbates the primary MYO7AG2164C mutation (5). The extent of hearing loss variation in the HL2 pedigree within and between family generations supports the prediction that the putative genetic modifier is a sequence variation commonly found in the general Caucasian population (9). One simple yet elegant mechanism to generate clinical variation within a pedigree segregating a dominant disease would be a single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) within the wild-type promoter allele that acts in trans either to increase or to decrease expression of the wild-type allele, which is brought into the family by marry-in spouses that are not related genetically to the family members segregating the dominant mutation.

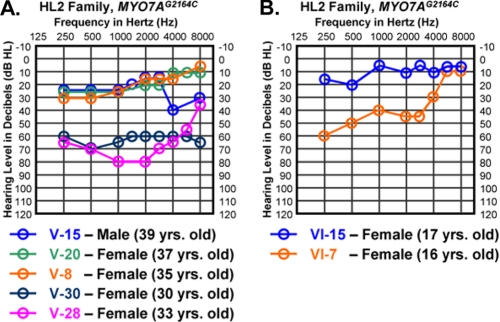

FIGURE 1.

Variation in clinical severity between similarly aged HL2 family members. A, three MYO7AG2164C individuals with mild hearing loss versus two MYO7AG2164C individuals with more severe hearing loss in the low and mid frequency ranges. All five individuals are between the ages of 30 and 39 years old. B, two MYO7AG2164C teenage females showed marked differences in low and mid frequency auditory thresholds. Auditory thresholds are shown for the right ears only. Responses between the right and left ears were symmetrical. Frequency in hertz (Hz) is plotted on the x axis and hearing level in decibels (dB HL) on the y axis.

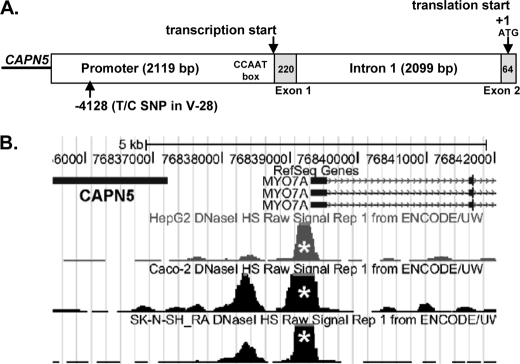

The genomic structure 5′ of the MYO7A ATG translational start is shown in Fig. 2. The CAPN5 gene is located upstream of MYO7A with the CAPN5 3′ end separated from MYO7A exon 1 by 2119 bp. The untranslated MYO7A exon 1 (220 bp) is followed by intron 1 (2099 bp) and MYO7A exon 2 (64 bp) containing the ATG start. 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends assays using cDNA derived from the mouse vestibular system suggest that MYO7A RNA transcription initiates at exon 1 (10). Functional DNase I hypersensitivity data from ENCODE (11) (ENCyclpedia Of DNA Elements) support transcription initiation in this region (Fig. 2B, white asterisks). Although a consensus TATA box is not found, a consensus CCAAT box as predicted by MatInspector is located just 5′ of exon 1.

FIGURE 2.

The 5′ MYO7A promoter area is represented from the 3′ end of the CAPN5 gene through exon 2 in MYO7A. A, the CAPN5 gene is located upstream of MYO7A with the CAPN5 3′ end separated from MYO7A exon 1 by 2119 bp. The untranslated MYO7A exon 1 (220 bp, light gray box) is followed by intron 1 (2099 bp) and MYO7A exon 2 (64 bp, light gray box) containing the ATG start (shown as +1). The Myo7a transcription initiation site within the inner ear is shown 5′ of exon 1 with a CCAAT box designated in the figure. B, an image captured from ENCODE indicates robust DNase I sensitivity near the transcription initiation site in the HepG2, Caco-2, and SK-N-SH RA cell lines.

In this report, we investigate a SNP within the wild-type promoter allele of MYO7A in the HL2 pedigree that segregates with the mild versus more severe hearing impairment in the HL2 family members. The T/C SNP at position −4128 in the MYO7A promoter (Fig. 2) creates a YY1 transcription factor binding site that leads to differential binding of YY1. We also demonstrate for the first time that YY1 is expressed in the cochlea within the inner and outer hair cells, in the same cells where MYO7A is also expressed giving YY1 appropriate cellular localization to regulate MYO7A transcription. Reporter gene assays indicate that the T/C SNP can modulate the level of gene expression. Therefore, the YY1 binding site at T−4128 in the wild-type MYO7A promoter allele serves as a strong candidate to modulate clinical variability within the HL2 pedigree.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

MYO7A Promoter Sequence Analysis

The 4502-bp MYO7A 5′ region containing the promoter, exon 1, intron 1, and exon 2 were PCR-amplified from genomic DNA with the primers in Table 1. The PCR and purification parameters were performed as noted previously (12). Each overlapping PCR product spanned ∼450 bp and was sequenced using the amplification primer. Sequencing was conducted using the BigDye Terminator v3.1 Cycle Sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Electropherograms were analyzed using the CodonCode Aligner software package (CodonCode Corporation, Dedman, MA).

TABLE 1.

PCR Primers to amplify MYO7A 5′ region

| Primers | Primer sequences | Annealing temperature |

|---|---|---|

| ° C | ||

| 1f/1r | 5′-ccaggcaggtaaggatcagg-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-catgcacagatcagggagtagg-3′ | ||

| 2f/2r | 5′-aaacgagcagcgagaacaaag-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-gagaggtgggcaggttatgg-3′ | ||

| 3f/3r | 5′-ctcgctttcttcatgggactg-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-caccgctgggaagtgacc-3′ | ||

| 4f/4r | 5′-ggcatcctggggtcttcc-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-acacccacccttgcctctg-3′ | ||

| 5f/5r | 5′-gcaaagtttctggatgattacgg-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-aaggtctgggtgcggtga-3′ | ||

| 6f/6r | 5′-cacagccagagacagacc-3′ | 66 |

| 5′-agaggctctagaggtagc-3′ | ||

| 7f/7r | 5′-gcaggtggcagctgtacc-3′ | 64 |

| 5′-ctcccatttcacagatgg-3′ | ||

| 8f/8r | 5′-ccaggggaatagacatgc-3′ | 62 |

| 5′-ctgaactagtctggatgc-3′ | ||

| 9f/9r | 5′-cctcatggctcatgctgg-3′ | 67 |

| 5′-cagggtaagggtcagtcc-3′ | ||

| 10f/10r | 5′-caaggcaatgtctcagacc-3′ | 65 |

| 5′-ctgaaacctctcaagagc-3′ | ||

| 11f/11r | 5′-tgcattcagcagcacagc-3′ | 66 |

| 5′-gaggtgggaacactgacc-3′ |

PCR Expression

To amplify YY1 from the mouse cochlea and chicken basilar papilla cDNA the following PCR primer pairs were employed at 60 °C and 55 °C, respectively: mouse/human, 5′-cagagtccacgtctgtgc-3′ and 5′-caggttagttgactgagc-3′; chicken, 5′-gctgcacaaagatgttcagg-3′ and 5′-gaaaaacgctttccacatcc-3′. PCR and sequencing reaction parameters were as described above.

Nuclear Cell Extract

Nuclear cell extract containing YY1 protein was isolated from the ARPE-19 cell line (catalog number CRL-2302; American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA). ARPE-19 is a spontaneously arising retinal pigment epithelia cell line derived from the normal eyes of a 19-year-old male (13). We demonstrated by RT-PCR that YY1 is expressed in the ARPE-19 human cell line using the mouse/human YY1 PCR primer pair described above. The ARPE-19 cell line was grown until 80% confluent and then harvested using the NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagent System (catalog number 78833; Pierce). Protein concentration was determined using a BCA Protein Assay Reagent kit (catalog number 23227; Pierce).

Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

The EMSA was performed using the LightShift Chemiluminescent EMSA protocol (catalog number 21048; Pierce) with 2 μg of ARPE-19 nuclear extract/20-μl reaction, which was incubated on ice for 20 min. For the supershift assay, 2 μg of antibody was added to the reaction mixture prior to the addition of biotin-labeled target DNA and incubated on ice for 90 min. The following YY1 antibodies were employed: YY1 (C-20) × (rabbit polyclonal); YY1 (H-414) × (rabbit polyclonal); and YY1 (H-10) × (mouse monoclonal). The reaction mixtures were separated by electrophoresis on 5% polyacrylamide gels overnight at 30 volts at 4 °C. DNA-protein complexes were transferred to Biodyne B nylon membranes (catalog number 77016; Pierce), cross-linked at 120 mJ/cm2, and visualized using a Chemiluminescent Nucleic Acid Detection Module (catalog number 89880; Pierce). The double-stranded DNA targets were generated by boiling the appropriate oligonucleotide pairs for 5 min in 1 liter of water followed by slow cooling to room temperature. All oligonucleotides were HPLC-purified following synthesis, and subsets of the oligonucleotides were 3′-labeled with biotin (Integrated DNA Technologies, San Diego, CA). The following oligonucleotides and their complement were used to create double-stranded DNA targets: canonical YY1 site, 5′-ccgataagacgCCATtttaagtcctacgtca-3′ (14); T−4128 SNP on minus strand, 5′-tcagggagtaggCCATctctaacccagcagg-3′; and C−4128 SNP on minus strand, 5′-tcagggagtaggCCGTctctaacccagcagg-3′.

Immunocytochemistry

Brains and temporal bones were collected from 8-week-old CBA/CaJ mice that were deeply anesthetized and perfused intracardially with cold 4% paraformaldehyde in 0.1 m phosphate buffer (PBS), pH 7.4. Brains were dissected from the skulls. An intralabyrinthine perfusion of fixative was performed on the temporal bone. The brain and temporal bone tissue was fixed for 2 h in 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature on a tissue rotator. The tissue was rinsed for 5 minutes three times in PBS. The temporal bone was decalcified for 15 min in RDO (catalog number RDO-01; Apex Engineering, Aurora, IL) at room temperature on a rotator followed by 3 × 5 min rinses in PBS. Brain and temporal bone/cochlear tissue was then cyroprotected in successive overnight changes of increasing sucrose concentrations (brain, 10%, 20%, 30%; cochlea, 10%, 12%, 15%), embedded in OCT (catalog number 25608-930; VWR, Pittsburgh, PA), quick frozen in liquid nitrogen-chilled heptane, sectioned at 14 μm by cryostat (Leica CM1850), and collected on StarFrost Adhesive slides (catalog number 7255/90°; Mercedes Medical, Sarasota, FL). Prior to immunocytochemistry, the tissue sections were incubated with pepsin at 1 g/250 ml in 0.2 n HCL (catalog number S3002; Dako North America, Carpinteria, CA) for 4–7 min at 37 °C to retrieve the YY1 antigen. Following antigen retrieval the sections underwent the following procedures. The sections were rinsed 3 × 10 min in PBS; incubated for 10 min with 0.1% saponin (catalog number S4521; Sigma-Aldrich) in PTW (0.1% Tween 20 in PBS); rinsed 3 × 10 min in PTW; blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% normal goat serum (catalog number S-1000, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), 0.03% saponin in PBT (0.1%Triton X-100, 2 mg/ml BSA in PBS); rinsed 3 ×10 min in PTW; and reacted with anti-YY1 C-20 × (1:2000) in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. On day 2, the slides were rinsed 1 × 10 min in PTW, blocked for 1 h at room temperature in 5% normal goat serum, reacted with the 2° goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 568 antibody (1:300, catalog number A-11011; Invitrogen) in blocking buffer for 2 h. If only reacting with the YY1 antibody, the slides proceeded to the DAPI nuclear stain as described below. In some cases, we also reacted the slides with a mouse monoclonal against parvalbumin (1:500 dilution) as an inner and outer hair cell-specific cytoplasmic marker (15, 16). A Myo7a antibody was not utilized as a hair cell marker for the double-immunolabeling studies because the well characterized and commercially available Myo7a antibodies are rabbit polyclonals as is the YY1 C-20 antibody, therefore not allowing the use of species-specific secondary antibodies. The anti-parvalbumin antibody (catalog number P3088; Sigma-Aldrich) was used with the M.O.M. kit (catalog number BMK-2202; Vector Laboratories) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Following overnight incubation with anti-parvalbumin at 4 °C, the slides were rinsed 3 × 10 min in PTW, blocked for 5 min at room temperature in 5% normal goat serum, reacted with the 2° goat anti-mouse Alexa Fluor 488 antibody (1:300, catalog number S-11001; Invitrogen) in blocking buffer for 2 h. The slides were then rinsed 3 × 10 min in PTW, incubated with 1 μg/ml DAPI (catalog number D9542; Sigma-Aldrich) diluted 1:100 in PBS for 30 min, rinsed 3 × 10 min in PTW, mounted with Fluoromount-G (catalog number 0100-01; Southern Biotech, Birmingham, AL), and coverslipped (24 × 55 mm, catalog number 48393241; VWR). To capture confocal images of the sections we used an Olympus FV-1000 microscope as described previously (15). Files were imported into ImageJ and/or Adobe Photoshop for processing and analysis.

Luciferase Reporter Constructs

T−4128 SNP Construct

The unlinked MYO7A promoter region (−4496 to +1 ATG) containing the YY1 site was PCR-amplified from the genomic DNA of female V-28 using the Elongase Enzyme Mix (10480-010; Invitrogen). Two sets of overlapping PCR primers were employed: first set, forward 5′-agtcatctcgagtcctgtgtccctctgtcc-3′ and reverse 5′-aagcccagtcccaggagcaagtggctgtgg with touch down PCR from 62 to 57 °C; second set, forward 5′-ggagtcatggacttgagctacc-3′ and reverse 5′-agaggtgggaacactgacctgc-3′ with touch down PCR from 60 to 55 °C. The PCR products were subcloned using the TOPO XL PCR Cloning kit (4700-10; Invitrogen) and sequenced to separate the wild-type unlinked allele from the mutant linked allele and to select for fragments without DNA polymerase-induced errors. The correct unlinked products were fused at an XbaI restriction endonuclease site (see Fig. 7A) and cloned into the pGL3-Basic vector (E1751; Promega) at a 5′ XhoI site and 3′ NcoI site within the MYO7A ATG start placing the MYO7A promoter sequence upstream of the firefly luciferase coding sequence.

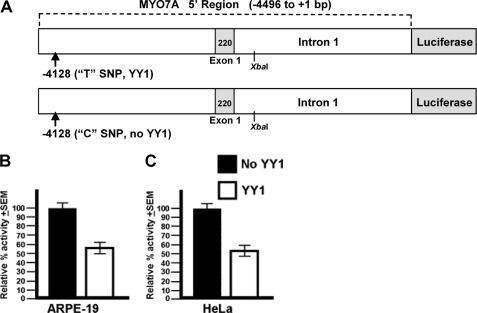

FIGURE 7.

T−4128 SNP decreases reporter gene expression. Expression of the YY1 and non-YY1 MYO7A promoter constructs in two different human cell types is shown. 100% activity in each cell line was arbitrarily set to the normalized luciferase activity from the non-YY1 C−4128 construct. A, in the ARPE-19 cell line the construct containing the T−4128 SNP, which creates the YY1 binding site, decreases luciferase expression by 41% compared with the construct containing the C−4128 SNP (p = 0.036). B, in the HeLa cell line the construct containing the T−4128 SNP decreases luciferase expression by 46% compared with the construct containing the C−4128 SNP (p = 0.008).

C−4128 SNP Construct

To create the non-YY1 reporter construct the T at −4128 was changed to a C using the QuikChange II Site-directed Mutagenesis protocol (200523; Stratagene).

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection Assays

HeLa cells (CCL-2; ATCC) were grown in DMEM (11995; Invitrogen). ARPE-19 cells were grown in DMEM:F12 medium (11330032; Invitrogen). Both media were supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% ampicillin/streptomycin. Cell lines were maintained in a 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Twenty-four hours prior to transfection, cells were plated on 24-well plates (4 × 104/well). Samples (100 ng) of the T−4128 or C−4128 SNP experimental construct were transfected in triplicate wells with FuGENE HD Transfection Reagent (04-709-705-001; Roche Applied Science). The pRL-TK plasmid (1 ng/well, E2241; Promega) was used to normalize the transfection efficiency. Cells were harvested 40–48 h after transfection, and the reporter gene expression was analyzed using the Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (E1960; Promega) in a luminometer (Lumat LB9507; BERTHOLD Technologies). Basal activity from the promoterless pGL3-basic vector was subtracted from the normalized activity of the experimental constructs. Triplicate data from at least three independent transfections were collected for each construct in both cell lines. The mean for each triplicate data set was utilized for a statistical comparison with Student's t test.

RESULTS

YY1 Transcription Factor Binding Site Predicted in Severe Hearing Loss

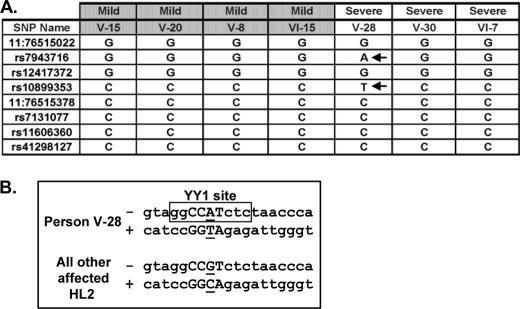

To characterize promoter SNPs that may be influencing expression of MYO7A in the HL2 family, we analyzed the 2119-bp promoter sequence in the seven HL2 family members showing marked differences in hearing loss severity. We constructed haplotypes across the 2119-bp region for the seven individuals, who all shared one haplotype in common representing the affected linked haplotype carrying the MYO7AG2164C mutation. For the wild-type MYO7AG2164 allele in these seven individuals, we found two different haplotypes across the 2119-bp area. All of the mildly affected MYO7AG2164C individuals V-8, V-15, V-20, and VI-15 carry the same haplotype (Fig. 3A). The more severely affected individual female V-28 carries a unique haplotype created by two DNA variants at SNPs rs7943716 and rs10899353. The MatInspector and FuncPred programs predict that SNP rs7943716 has no functional consequence, whereas the T/C SNP rs10899353 at position −4128 (Fig. 2A) would result in gain of a multifunctional YY1 (Yin and Yang) transcription factor binding site in person V-28 (Fig. 3B). In the HapMap CEU population, SNP rs10899353 was genotyped in 113 individuals with identification of the following genotype frequencies: C/C = 0.796, T/C = 0.204, T/T = 0.0. CEU stands for Utah residents with Northern and Western European ancestry from the CEPH collection. More severely affected individuals V-30 and VI-7 carry the same promoter haplotype as the mildly affected individuals across the promoter (Fig. 3A), but their unlinked haplotype diverges from that of individuals V-15, V-20, V-8, and VI-15 3′ within intron 1 (data not shown).

FIGURE 3.

An YY1 transcription factor binding site is created by a T/C SNP at position −4128 in the MYO7A promoter. A, the wild-type haplotype in mild versus more severely affected HL2 individuals was constructed across the 2119-bp MYO7A promoter. Eight known SNPs are included as references points. A unique haplotype in individual V-28 is created by SNPs rs7943716 and rs10899353 (designated with arrows). The rs10899353 is predicted to create an YY1 transcription factor binding site. B, the YY1 consensus DNA recognition sequence in person V-28 is boxed with the core DNA binding residues shown in capital letters. The rs10899353 SNP is underlined. The DNA strand is designated with a minus or plus sign.

YY1 Binds Differentially to the MYO7A Promoter SNP T/C−4128

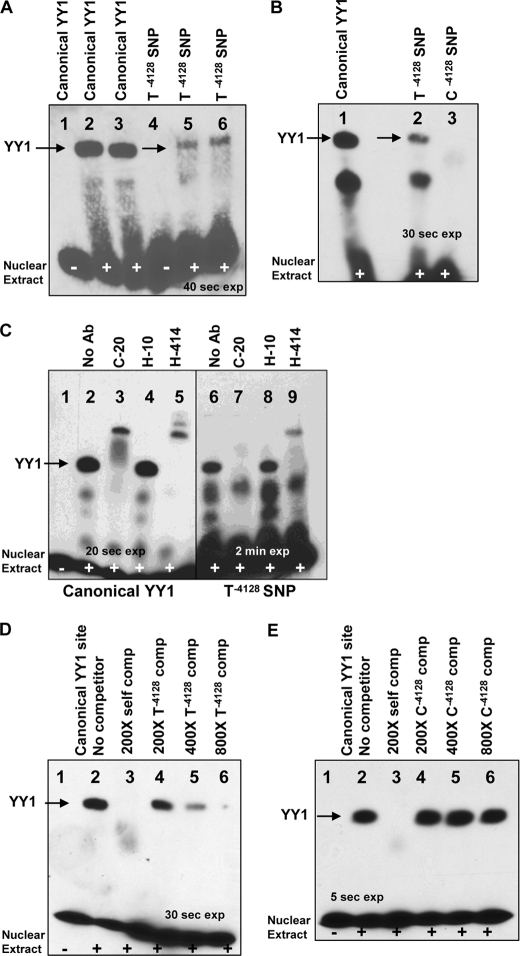

To determine whether the YY1 protein binding site predicted by MatInspector in female V-28 was functional, we performed an EMSA. As a positive control, we created a 31-bp DNA double-stranded target end-labeled with biotin containing a canonical YY1 binding site (14) which demonstrated a shift when reacted with the ARPE-19 nuclear extract (Fig. 4A, lanes 2 and 3). With this positive control in hand, a 31-bp DNA target was created containing the putative YY1 binding site in female V-28 (referred to as T−4128 SNP). The T−4128 DNA target demonstrated shifted bands similar to those seen with the canonical YY1 binding site (Fig. 4A, lanes 5 and 6) suggesting that the putative YY1 binding site gained by female V-28 is functional. We next wanted to determine whether the T/C SNP at MYO7A position −4128 controls differential binding of YY1. A 31-bp DNA target identical to the T−4128 target except for the C SNP at position −4128 was created (referred to as C−4128 SNP) and reacted with ARPE-19 nuclear extract. The C−4128 DNA target did not show the YY1-shifted product seen with the canonical YY1 and T−4128 targets (Fig. 4B). These findings suggest that the T/C SNP at MYO7A position −4128 controls differential binding of YY1.

FIGURE 4.

EMSA of YY1 binding to MYO7A T−4128 SNP. The differential binding of YY1 to the MYO7A promoter SNPs T−4128 and C−4128 was analyzed by EMSA. A, canonical YY1 versus T−4128 SNP is shown. Lane 1 contains the canonical unshifted YY1 binding target without ARPE-19 nuclear extract. Lanes 2 and 3 contain the canonical YY1 binding target reacted with the ARPE-19 nuclear extract and demonstrate a shift. Lane 4 contains the T−4128 SNP target DNA without extract. Lanes 5 and 6 contain the T−4128 SNP target DNA with extract and demonstrate a shift similar to the canonical YY1 target. B, T−4128 versus C−4128 SNP is shown. Lanes 1 and 2 show similar shifts with lane 1 containing the canonical YY1 target and lane 2 containing the T−4128 SNP target DNA. Lane 3 contains the C−4128 SNP target and does not show a shift. C, supershift assay is shown using three different YY1 antibodies. Lanes 1–5 utilized the canonical YY1 binding target and demonstrate supershifts with the two polyclonal YY1 antibodies C-20, and H-414. Lanes 6–9 utilized the T−4128 binding target and demonstrate a supershift with H-414. The C-20 antibody does not lead to a supershift but abolishes the YY1 shift. D, T −4128 SNP target DNA can compete with binding to the canonical YY1 target. The canonical YY1 target is used in lanes 1–6. Lanes 3 utilized a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled canonical YY1 target. Lanes 4–6 utilized a 200-, 400-, or 800-fold molar excess of the unlabeled T−4128 target site. E, the C−4128 SNP target DNA cannot compete with binding to the canonical YY1 target. The canonical YY1 target is used in lanes 1–6. Lanes 3 utilized a 200-fold molar excess of unlabeled canonical YY1 target. Lanes 4–6 utilized a 200-, 400-, or 800-fold molar excess of the unlabeled C−4128 target site.

To address further the authenticity of the YY1 binding site in V-28, we performed a supershift EMSA assay. Three different YY1 antibodies were utilized in the EMSA reaction mixture with either the canonical YY1 or the T−4128 target. With the canonical YY1 target, a supershift was seen with both the C-20 and H-414 polyclonal antibodies but not with the H-10 monoclonal antibody (Fig. 4C, lanes 1–5). With the T−4128 target (Fig. 4C, lanes 6–9), a supershift was seen with the H-414 antibody (lane 9). The C-20 antibody did not result in a supershift when added to the reaction mixture containing the T−4128 target, but did prevent the regular YY1 shift from occurring (lane 7), suggesting that the C-20 antibody bound YY1 in the ARPE-19 nuclear extract preventing the T−4128 target from accessing its normal binding site. As for the canonical YY1 target, the H-10 antibody had no impact on the T−4128 target when added to the reaction mixture. The supershift results indicate that the shifted band seen with both the canonical YY1 and T−4128 target indeed represents YY1 protein.

To support the specificity of the T−4128 target further, we performed cross-competition experiments. In the first cross-competition experiment the T−4128 DNA target was used to compete with the canonical YY1 target (Fig. 4D). As expected, unlabeled canonical YY1 DNA target was able to out-compete itself at a 200-fold molar excess (Fig. 4D, lane 3). Next, the unlabeled T−4128 DNA was used in an effort to compete with the canonical YY1 DNA target. As the concentration of the unlabeled T−4128 DNA target increased from 200-, 400-, to an 800-fold molar excess the T−4128 DNA target was able to compete increasingly with the canonical YY1 DNA target. However, as shown in Fig. 4E, the unlabeled C−4128 DNA target at 200-, 400-, and an 800-fold molar excess is not able to compete with the canonical YY1 DNA target for YY1 binding.

YY1 Is Expressed in Cochlear Hair Cells

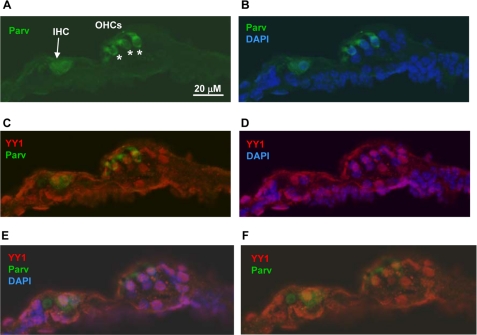

We amplified Yy1 from the mouse cochlear and the chicken basilar papilla by RT-PCR. In both cases a clean and robust PCR product was clearly visible on an ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel. The product was purified and sequenced to ensure that the PCR product represented the expected mouse or chicken Yy1 cDNA sequence. Although the mouse cochlear cDNA preparation contains a number of cell types in addition to hair cells, the tissue dissected from the chicken basilar papilla contains primarily hair cells and support cells (17). Given these positive results, we next characterized the localization of Yy1 in the mouse cochlea by immunocytochemistry after first optimizing experimental conditions on mouse brain sections (data not shown) as Yy1 is known to be strongly expressed in the rodent hippocampus (18). As shown in a basal turn from the organ of Corti, Yy1 is expressed in both the inner and outer hair cell nuclei as shown by DAPI nuclear counterstain, in addition to several support cell types such as Hensen and Deiter cells (Fig. 5B and E). Yy1 is also expressed in the adjacent nonsensory epithelium such as sulcus cells and the spiral ganglion (Fig. 5, A, C, and D). To confirm localization of Yy1 to the inner and outer hair cell nuclei, cochlear sections were double-immunolabeled with Yy1 and parvalbumin, a cytoplasmic marker of inner and outer hair cells (15, 16), and the nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Fig. 6 shows hair cells from a turn at the extreme apex of the cochlea (see lower magnification in supplemental Fig. S1). The plane of section in this slide allowed clear visualization of both the inner and outer hair cell nuclei (Fig. 6). Yy1 localization is readily apparent in the nuclei of both the inner and outer hair cells (Fig. 6, C–F). Previous studies have shown that Myo7a is expressed in the inner and outer hair cells (2, 3). This study demonstrates that Yy1 is expressed in the same cell types as Myo7a and that YY1 binds MYO7A promoter sequence, making YY1 a strong candidate to regulate MYO7A expression in the cochlea.

FIGURE 5.

Yy1 is expressed in mouse cochlea. Confocal images of cross-sections through a basal cochlear turn are shown. Sections were treated with pepsin for 7 min to retrieve antigen. A–C, YY1 expression in red. A, YY1 expression in the cochlea. The limbus, sulcus cells, and spiral ganglion are designated as reference points. The white box outline delineates the organ of Corti shown at a higher magnification in B. B, organ of Corti region. An Inner hair cell (IHC), outer hair cell (OHC), and tunnel of Corti are designated. C, confocal image showing YY1 expression in the spiral ganglion. D and E, confocal images showing red YY1 nuclear labeling overlaid with blue DAPI nuclear staining. Scale bars, 20 or 50 μm.

FIGURE 6.

Yy1 is expressed in hair cell nuclei. Confocal images of cross-sections through an extreme apical cochlear turn. Sections were treated with pepsin for 3 min to retrieve antigen. A, parvalbumin labeling (green). Inner hair cell (IHC) is designated by an arrow, outer hair cells (OHCs) are designated by asterisks. B, parvalbumin (green) and DAPI (blue). C, parvalbumin (green) and YY1 (red). D, YY1 (red) and DAPI (blue). E and F, confocal Z scan images enhancing visualization of the IHC nucleus. E, parvalbumin (green), YY1 (red), and DAPI (blue). F, parvalbumin (green) and YY1 (red). Scale bar, 20 μm.

YY1 Binding Site in MYO7A Promoter Down-regulates Reporter Gene Expression

To determine whether the T/C SNP at −4128 within the MYO7A promoter can modulate gene expression, we created two different luciferase constructs identical in sequence except for position −4128 (Fig. 7A). In the ARPE-19 cell line the T−4128 construct containing the YY1 binding site showed 41% less expression than the C−4128 construct lacking the YY1 site (Fig. 7B). In the HeLa cell line the T−4128 construct demonstrated 46% less expression than the C−4128 construct (Fig. 7C). These findings suggest that the T−4128 YY1 site within the MYO7A promoter can act as a transcriptional repressor in two different human cell lines.

DISCUSSION

We have found a MYO7AG2164C person (V-28) severely affected by hearing loss in the low and mid frequency ranges compared with other MYO7AG2164C affected family members. Person V-28 carries a unique wild-type MYO7A promoter haplotype created by a T/C SNP at position −4128 that predicts the gain of an YY1 transcription factor binding site on the T−4128 wild-type allele. The EMSA results demonstrate that the YY1 binding site is functional and authentic. The supershift EMSA results with the canonical YY1 and T−4128 DNA target from person V-28 indicate that both of these double-stranded DNA targets are binding YY1 in the ARPE-19 nuclear extract. Experiments utilizing the labeled C−4128 DNA target in the shift experiment and the unlabeled C−4128 DNA target in the cross-competition study very strongly support that the T/C SNP at position −4128 in the MYO7A promoter controls differential binding of the YY1 transcription factor. If YY1 is binding to the MYO7A promoter and regulating expression of MYO7A in the cochlea, YY1 must be expressed in hair cells where MYO7A has previously been localized. The immunocytochemistry studies indicate that YY1 is expressed in several cell types within the cochlea including the nuclei of inner and outer hair cells. The reporter gene assays indicate that the YY1 T−4128 SNP is acting as a transcriptional repressor in the human ARPE-19 and HeLa cell lines.

In addition to the possibility that YY1 is regulating MYO7A expression within the hair cells, YY1 may also be impacting other genes in the auditory system as several genes regulated by YY1 in the nervous system (Bace1, Glast1, Nrp1, Otx2, plp, REST, Snail) (19) are also expressed in the cochlea (20–24, 26). According to the NEIBank Data base, YY1 is present in the human cochlea and may therefore be involved in modulating other types of hearing loss.

The YY1 protein can act as a transcriptional activator or repressor (19). Our hypothesis is that a MYO7A promoter carrying the T−4128 SNP and YY1 binding site will drive less expression of MYO7A within the hair cells than a MYO7A promoter carrying the C−4128 SNP and no YY1 binding site. Using a similar approach Masotti et al. demonstrated by EMSA that a SNP in the TCOF1 promoter that altered YY1 binding resulting in a 38% change in promoter activity (27). The YY1-altering SNP carried on the wild-type TCOF1 allele is considered a trans-candidate to explain the high clinical variability in autosomal dominant Treacher-Collin syndrome patients, analogous to the mechanism we suspect may be contributing to clinical variability in hearing impaired HL2 MYO7AG2164C individuals.

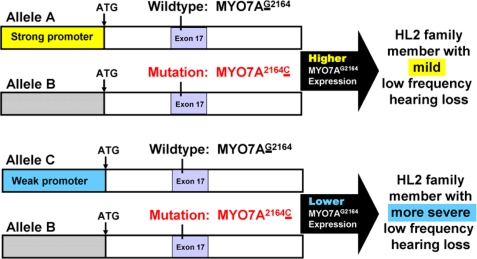

Our ability to pursue YY1 as a possible auditory genetic modifier is based on the size of the HL2 pedigree and clinical hearing loss variation within the family. All members of the HL2 pedigree affected by genetically based hearing loss share the MYO7AG2164C alteration within exon 17. We also know from previous linkage analysis that all of these hearing-impaired HL2 individuals share the same DNA surrounding the mutation including the promoter that drives expression of the mutated MYO7AG2164C allele (labeled as allele B in Fig. 8). Therefore, the mutated MYO7A allele B is held in common within affected HL2 family members. When searching for DNA variations that may impact expression of MYO7A, we can focus on the wild-type MYO7A allele that is brought into the HL2 family by marry-in spouses that are not related genetically to the HL2 family members. This process places the mutated MYO7A allele B across from a variety of different wild-type MYO7A alleles (for example allele A and C in Fig. 8 which are in trans with allele B). When sequencing a DNA sample from an affected HL2 individual, both the mutated and wild-type MYO7A allele are present. Given that the mutated allele B is held in common by these HL2 individuals, we can easily distinguish by phase analysis between DNA sequence contributing to the mutated versus wild-type allele, allowing us to focus on wild-type MYO7A promoter DNA variants introduced into the HL2 family by marriage. The ability to conduct phase analysis and to have the mutated MYO7A allele B held in common within the HL2 family is one of the powerful aspects contributed to this study due to the large HL2 pedigree size. Other studies trying to collect and interpret similar data to look at trans-allelic interactions are limited by their ability to establish phase and by not having the mutated allele identical within the study.

FIGURE 8.

MYO7A strong and weak promoter hypothesis. Alleles A and C represent wild-type alleles introduced into the HL2 family by marry-in spouses. Allele B represents the mutated MYO7A2164C allele carried by all hearing impaired HL2 family members. A strong wild-type MYO7A promoter allele A may drive a higher level of MYO7A expression than a weak wild-type MYO7A promoter allele C partially rescuing the impact of the mutated MYO7A allele B.

Our hypothesis is that certain DNA variants within the MYO7A promoter can create a strong (allele A) versus a relatively weak promoter (allele C) leading to increased or decreased levels of MYO7A expression, respectively. A strong wild-type MYO7A promoter allele (allele A) may drive a higher level of MYO7A expression partially rescuing the impact of the mutated MYO7A allele (allele B) leading to mild low frequency hearing loss. On the other hand, a weak wild-type MYO7A promoter allele (allele C) may result in a lower level of MYO7A expression exacerbating the impact of the mutated MYO7A allele (allele B) leading to more severe low frequency hearing loss. Our experimental findings are consistent with this model. To our knowledge, this study represents the first potential example of a trans-allelic genetic modifier of dominantly inherited hearing loss that may serve as a parsimonious model for modifiers impacting the clinical variation of dominantly inherited diseases in general.

The hair cell is sensitive to the level of Myo7a expression. In mice, recessively inherited Myo7a mutations were discovered at the shaker-1 (sh1) locus (1). An allelic sh1 series indicates that the less Myo7a protein expressed, the more severe the sh1 phenotype (25).

Analysis of the YY1 T−4128 MYO7A promoter SNP could be extended to other DFNA11 families as well as DFNB2 and USH1B pedigrees to determine whether the SNP is concordant with clinical variation. Large pedigrees such as the HL2 family may allow for detection of candidate modifying SNPs but may not provide enough statistical power to conduct an association analysis within the family as is the case with the HL2 pedigree where only one person in the family has the YY1 site on their wild-type allele. However, population-based association studies may be able to determine whether the YY1 T−4128 MYO7A promoter SNP is contributing to resistance or susceptibility to environmental acoustical trauma or aging. The YY1 T−4128 MYO7A promoter SNP may act only in concert with a frank mutation in the MYO7A gene or may have more widespread implications for the auditory system by reducing MYO7A expression within the cochlea.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Elizabeth Oesterle, John Redell, and Bruce Tempel for comments on this project. We also thank Dr. Jenny Stone, Robin Gibson, and Claire Walker for the chicken basilar papilla and mouse cochlear cDNA. We are indebted to Dr. Edith Wang for the use of her luminometer and advice regarding the luciferase assay. We are grateful to the HL2 family for their cooperation throughout this study.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants DC04945 (to V. A. S.) and P30 DC04661 (to the V. M. Bloedel Core). This work was also supported by a grant from the V. M. Bloedel Hearing Research Center (to V. A. S.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- MYO7A

- myosin VIIA

- EMSA

- electrophoretic mobility shift assay

- HL2

- hearing loss family 2

- SNP

- single nucleotide polymorphism.

REFERENCES

- 1. Gibson F., Walsh J., Mburu P., Varela A., Brown K. A., Antonio M., Beisel K. W., Steel K. P., Brown S. D. M. (1995) Nature 374, 62–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Hasson T., Heintzelman M. B., Santos-Sacchi J., Corey D. P., Mooseker M. S. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 9815–9819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hasson T., Gillespie P. G., Garcia J. A., MacDonald R. B., Zhao Y., Yee A. G., Mooseker M. S., Corey D. P. (1997) J. Cell Biol. 137, 1287–1307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Tamagawa Y., Kitamura K., Ishida T., Nishizawa M., Liu X. Z., Walsh J., Steel K. P., Brown S. D. (2000) Adv. Otorhinolaryngol. 56, 103–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Street V. A., Kallman J. C., Kiemele K. L. (2004) J. Med. Genet. 41, e62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Luijendijk M. W., Van Wijk E., Bischoff A. M., Krieger E., Huygen P. L., Pennings R. J., Brunner H. G., Cremers C. W., Cremers F. P., Kremer H. (2004) Hum. Genet. 115, 149–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bolz H., Bolz S. S., Schade G., Kothe C., Mohrmann G., Hess M., Gal A. (2004) Hum. Mutat. 24, 274–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Di Leva F., D'Adamo P., Cubellis M. V., D'Eustacchio A., Errichiello M., Saulino C., Auletta G., Giannini P., Donaudy F., Ciccodicola A., Gasparini P., Franzè A., Marciano E. (2006) Audiol. Neurootol. 11, 157–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kallman J. C., Phillips J. O., Bramhall N. F., Kelly J. P., Street V. A. (2008) Otol. Neurotol. 29, 860–867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boëda B., Weil D., Petit C. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10, 1581–1589 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Birney E., Stamatoyannopoulos J. A., Dutta A., Guigó R., Gingeras T. R., Margulies E. H., Weng Z., Snyder M., Dermitzakis E. T., Thurman R. E., Kuehn M. S., Taylor C. M., Neph S., Koch C. M., Asthana S., Malhotra A., Adzhubei I., Greenbaum J. A., Andrews R. M., Flicek P., Boyle P. J., Cao H., Carter N. P., Clelland G. K., Davis S., Day N., Dhami P., Dillon S. C., Dorschner M. O., Fiegler H., Giresi P. G., Goldy J., Hawrylycz M., Haydock A., Humbert R., James K. D., Johnson B. E., Johnson E. M., Frum T. T., Rosenzweig E. R., Karnani N., Lee K., Lefebvre G. C., Navas P. A., Neri F., Parker S. C., Sabo P. J., Sandstrom R., Shafer A., Vetrie D., Weaver M., Wilcox S., Yu M., Collins F. S., Dekker J., Lieb J. D., Tullius T. D., Crawford G. E., Sunyaev S., Noble W. S., Dunham I., Denoeud F., Reymond A., Kapranov P., Rozowsky J., Zheng D., Castelo R., Frankish A., Harrow J., Ghosh S., Sandelin A., Hofacker I. L., Baertsch R., Keefe D., Dike S., Cheng J., Hirsch H. A., Sekinger E. A., Lagarde J., Abril J. F., Shahab A., Flamm C., Fried C., Hackermüller J., Hertel J., Lindemeyer M., Missal K., Tanzer A., Washietl S., Korbel J., Emanuelsson O., Pedersen J. S., Holroyd N., Taylor R., Swarbreck D., Matthews N., Dickson M. C., Thomas D. J., Weirauch M. T., Gilbert J., Drenkow J., Bell I., Zhao X., Srinivasan K. G., Sung W. K., Ooi H. S., Chiu K. P., Foissac S., Alioto T., Brent M., Pachter L., Tress M. L., Valencia A., Choo S. W., Choo C. Y., Ucla C., Manzano C., Wyss C., Cheung E., Clark T. G., Brown J. B., Ganesh M., Patel S., Tammana H., Chrast J., Henrichsen C. N., Kai C., Kawai J., Nagalakshmi U., Wu J., Lian Z., Lian J., Newburger P., Zhang X., Bickel P., Mattick J. S., Carninci P., Hayashizaki Y., Weissman S., Hubbard T., Myers R. M., Rogers J., Stadler P. F., Lowe T. M., Wei C. L., Ruan Y., Struhl K., Gerstein M., Antonarakis S. E., Fu Y., Green E. D., Karaöz U., Siepel A., Taylor J., Liefer L. A., Wetterstrand K. A., Good P. J., Feingold E. A., Guyer M. S., Cooper G. M., Asimenos G., Dewey C. N., Hou M., Nikolaev S., Montoya-Burgos J. I., Löytynoja A., Whelan S., Pardi F., Massingham T., Huang H., Zhang N. R., Holmes I., Mullikin J. C., Ureta-Vidal A., Paten B., Seringhaus M., Church D., Rosenbloom K., Kent W. J., Stone E. A., Batzoglou S., Goldman N., Hardison R. C., Haussler D., Miller W., Sidow A., Trinklein N. D., Zhang Z. D., Barrera L., Stuart R., King D. C., Ameur A., Enroth S., Bieda M. C., Kim J., Bhinge A. A., Jiang N., Liu J., Yao F., Vega V. B., Lee C. W., Ng P., Shahab A., Yang A., Moqtaderi Z., Zhu Z., Xu X., Squazzo S., Oberley M. J., Inman D., Singer M. A., Richmond T. A., Munn K. J., Rada-Iglesias A., Wallerman O., Komorowski J., Fowler J. C., Couttet P., Bruce A. W., Dovey O. M., Ellis P. D., Langford C. F., Nix D. A., Euskirchen G., Hartman S., Urban A. E., Kraus P., Van Calcar S., Heintzman N., Kim T. H., Wang K., Qu C., Hon G., Luna R., Glass C. K., Rosenfeld M. G., Aldred S. F., Cooper S. J., Halees A., Lin J. M., Shulha H. P., Zhang X., Xu M., Haidar J. N., Yu Y., Ruan Y., Iyer V. R., Green R. D., Wadelius C., Farnham P. J., Ren B., Harte R. A., Hinrichs A. S., Trumbower H., Clawson H., Hillman-Jackson J., Zweig A. S., Smith K., Thakkapallayil A., Barber G., Kuhn R. M., Karolchik D., Armengol L., Bird C. P., de Bakker P. I., Kern A. D., Lopez-Bigas N., Martin J. D., Stranger B. E., Woodroffe A., Davydov E., Dimas A., Eyras E., Hallgrímsdóttir I. B., Huppert J., Zody M. C., Abecasis G. R., Estivill X., Bouffard G. G., Guan X., Hansen N. F., Idol J. R., Maduro V. V., Maskeri B., McDowell J. C., Park M., Thomas P. J., Young A. C., Blakesley R. W., Muzny D. M., Sodergren E., Wheeler D. A., Worley K. C., Jiang H., Weinstock G. M., Gibbs R. A., Graves T., Fulton R., Mardis E. R., Wilson R. K., Clamp M., Cuff J., Gnerre S., Jaffe D. B., Chang J. L., Lindblad-Toh K., Lander E. S., Koriabine M., Nefedov M., Osoegawa K., Yoshinaga Y., Zhu B., de Jong P. J. (2007) Nature 447, 799–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Street V. A., Robinson L. C., Erford S. K., Tempel B. L. (1995) Genomics 29, 123–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dunn K. C., Aotaki-Keen A. E., Putkey F. R., Hjelmeland L. M. (1996) Exp. Eye. Res. 62, 155–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hyde-DeRuyscher R. P., Jennings E., Shenk T. (1995) Nucleic Acids Res. 23, 4457–4465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Oesterle E. C., Campbell S., Taylor R. R., Forge A., Hume C. R. (2008) J. Assoc. Res. Otolaryngol. 9, 65–89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sage C., Ventéo S., Jeromin A., Roder J., Dechesne C. J. (2000) Hear. Res. 150, 70–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Daudet N., Gibson R., Shang J., Bernard A., Lewis J., Stone J. (2009) Dev. Biol. 326, 86–100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Rylski M., Amborska R., Zybura K., Konopacki F. A., Wilczynski G. M., Kaczmarek L. (2008) Neurochem. Res. 33, 2556–2564 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. He Y., Casaccia-Bonnefil P. (2008) J. Neurochem. 106, 1493–1502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jin Z. H., Kikuchi T., Tanaka K., Kobayashi T. (2003) Tohoku J. Exp. Med. 200, 137–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Knipper M., Bandtlow C., Gestwa L., Köpschall I., Rohbock K., Wiechers B., Zenner H. P., Zimmermann U. (1998) Development 125, 3709–3718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lu Z., Corwin J. T. (2008) Dev. Neurobiol. 68, 1059–1075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Martinez-Monedero R., Luo L., Edge A. (2006) Association for Research in Otolaryngology Midwinter Meeting, Baltimore, Maryland, February 5–6, 2006, pp. 285–286, Abstract no. 846, Association for Research in Otolaryngology, Mt. Royal, NJ [Google Scholar]

- 24. Miyazaki H., Kobayashi T., Nakamura H., Funahashi J. (2006) Dev. Growth. Differ. 48, 429–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hasson T., Walsh J., Cable J., Mooseker M. S., Brown S. D., Steel K. P. (1997) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 37, 127–138 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberson D. W., Alosi J. A., Mercola M., Cotanche D. A. (2002) Hear. Res. 172, 62–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Masotti C., Armelin-Correa L. M., Splendore A., Lin C. J., Barbosa A., Sogayar M. C., Passos-Bueno M. R. (2005) Gene 359, 44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.