Abstract

The productive program of human papillomaviruses occurs in differentiated squamous keratinocytes. We have previously shown that HPV-18 DNA amplification initiates in spinous cells in organotypic cultures of primary human keratinocytes during prolonged G2 phase, as signified by abundant cytoplasmic cyclin B1 (Wang, H. K., Duffy, A. A., Broker, T. R., and Chow, L. T. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 181–194). In this study, we demonstrated that the E7 protein, which induces S phase reentry in suprabasal cells by destabilizing the p130 pocket protein (Genovese, N. J., Banerjee, N. S., Broker, T. R., and Chow, L. T. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 4862–4873), also elicited extensive G2 responses. Western blots and indirect immunofluorescence assays were used to probe for host proteins known to control G2/M progression. E7 expression induced cytoplasmic accumulation of cyclin B1 and cdc2 in the suprabasal cells. The elevated cdc2 had inactivating phosphorylation on Thr14 or Tyr15, and possibly both, due to an increase in the responsible Wee1 and Myt1 kinases. In cells that harbored cytoplasmic cyclin B1 or cdc2, there was also an accumulation of the phosphatase-inactive cdc25C phosphorylated on Ser216, unable to activate cdc2. Moreover, E7 expression induced elevated expression of phosphorylated ATM (Ser1981) and the downstream phosphorylated Chk1, Chk2, and JNKs, kinases known to inactivate cdc25C. Similar results were observed in primary human keratinocyte raft cultures in which the productive program of HPV-18 took place. Collectively, this study has revealed the mechanisms by which E7 induces prolonged G2 phase in the differentiated cells following S phase induction.

Keywords: CDK (Cyclin-dependent Kinase), Checkpoint Control, Cyclins, Epithelium, Papilloma Viruses, ATM, E7, G2, Human Papillomavirus, cdc25C

Introduction

Human papillomaviruses (HPV)2 are small double-stranded DNA tumor viruses of considerable medical importance. They infect epithelial tissues, causing benign hyperproliferative lesions. More than 120 HPV genotypes have been cloned from patient specimens. The mucosotropic HPVs are broadly grouped into high-risk (HR) or low-risk (LR) types (1). Persistent infections of the cervix, penis, anus, and the oropharyngeal epithelium by HR HPV-16, HPV-18, and related types can at a low frequency progress into high grade dysplasias and cancers. Infections by LR HPV types 6 and 11 cause 90% of benign genital warts and all the laryngeal papillomas, and these infections rarely progress to cancers. For both HR and LR HPVs, infection initiates in basal epithelial keratinocytes through wounding and is established during healing, whereas the viral productive program is tightly linked to squamous differentiation (for a review, see Ref. 2). Because the differentiated spinous cells would normally have withdrawn from the cell cycle and viral DNA replication is dependent on the host DNA replication machinery, the roles of the viral E6 and E7 oncoproteins are to reestablish a milieu in the differentiated keratinocytes supportive for viral DNA amplification. Briefly, E7 proteins of HR and LR HPV types promote S phase reentry in the differentiated strata (3, 4). They do so by destabilizing p130, a pRB related pocket protein, which prevents S phase reentry by the differentiated cells (5, 6). The mechanisms by which E6 enables efficient viral DNA amplification are not yet understood.

The viral life cycle has recently been recapitulated with high efficiency in organotypic (raft) cultures of primary human keratinocytes (PHKs) grown at the liquid medium-air interface. In these PHKs, HPV-18 genomic plasmids were efficiently generated in vivo by Cre-loxP-mediated excision recombination from a transfer vector (7). As in patient specimens, the double-stranded HPV genomic plasmid is maintained at low copy numbers in the basal keratinocytes, and extensive amplification occurs in the mid and upper spinous strata. Moreover, viral DNA initiates amplification in G2-arrested cells, following host DNA replication, as revealed by the accumulation of highly elevated cytoplasmic cyclin B1 protein (7). As the viral DNA amplifies, the E7 activity progressively diminishes and eventually ceases in the upper strata; keratinocytes then exit the cell cycle, as evidenced by the gradual reappearance of p130 and disappearance of the proliferating cell nuclear antigen, a protein induced by E7. Being an E2F-responsive gene, cyclin B1 disappears when E7 activity ceases. These cells then transit to the late phase of infection and express the capsid proteins for progeny virion morphogenesis. Here, we show that E7 alone is necessary and sufficient to induce prolonged G2 following S phase reentry in differentiated keratinocytes of raft cultures and have investigated the mechanisms that mediate this arrest.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

The retroviral constructs expressing wild type HPV-18 E7 (18E7) and E7 mutations (C27S, ΔDLLC, E35Q,E36Q,E37Q, and S32Q,S33Q) have been described (3, 6, 8, 9). In these vectors, E7 is expressed from the HPV-18 enhancer-promoter located in the upstream regulatory region, whereas the neomycin resistance gene is driven by the SV40 promoter. The pNeo-loxP HPV-18 plasmid has been described (7). The nls-Cre expression vector pCAGGS was a gift from Hardouin and Nagy (10).

Retrovirus Production, Infection of PHKs, and Raft Culturing

PHKs were isolated from neonatal foreskin as described (11). Early passage (P0/P1) cells were used for retroviral infection. Briefly, Bosc23 cells (ATCC, CRL-11270) and GP+envAm-12 (ATCC, CRL-9641) cells were used for ecotropic and amphotropic retrovirus production, respectively (12). Amphotropic retroviruses were then used to infect PHKs and selected with 250 μg/ml of geneticin (Invitrogen) or 1.5 μg/ml of puromycin for 2 days. After a recovery for 2 more days, the bulk of the surviving cells were placed on a dermal equivalent comprised of rat tail type 1 collagen with embedded murine 3T3 J2 fibroblasts. Organotypic cultures were developed upon culturing the assembly at the liquid medium-air interface for 10 days (12). For the 6–12 h immediately prior to harvest, BrdU was added to the medium at 50 μg/ml to label replicating host chromosomal DNA.

PHK Raft Cultures Containing Amplifying HPV-18 Genomic Plasmids

Transfection of pNeo-loxP HPV-18 and pCAGGS (encoding nls-Cre) into early passages of PHKs has been described (7). Transfected PHKs were selected with G418 (100 μg/ml) for 4 days. After a 1- or 2-day recovery, the cells were cultured as organotypic rafts for 10–14 days. BrdU was added to the medium at 50 μg/ml for 12 h immediately prior to harvest. Ten day old cultures were harvested for Western blots. Ten-, 12-, or 14-day-old cultures were used for in situ assays.

Antibodies

BrdU was detected with mouse monoclonal anti-BrdU (1:100 dilution, catalog number NA20, Calbiochem, Merck) or sheep polyclonal biotinylated anti-BrdU (1:150, Ab 2284–125, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) antibodies. The antibodies against cdc2 (catalog number 9116B, mouse monoclonal), rabbit polyclonal antibodies against phospho-cdc2 Thr14 (catalog number 2543), phospho-cdc2 Thr161 (catalog number 9114), phospho-histone 3 Ser10 (catalog number 9701), Wee1 (catalog number 4936), Myt1 (catalog number 4282), phospho-Myt1 Ser83 (catalog number 4281), phospho-ATR Ser428 (catalog number 2853), Chk1 (catalog number 2345), phospho-Chk1 Ser345 (catalog number 2341), Chk2 (catalog number 2662), and phospho-Chk2 Thr68 (catalog number 2661) were all purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Beverly, MA). Rabbit monoclonal antibodies to phospho-cdc2 Tyr15 (catalog number 2543) and phospho-cdc25C Ser216 (catalog number 4901B) were also purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Rabbit monoclonal antibodies against cyclin B1 (catalog number 1495), ATM (catalog number 1549), and phospho-ATM Ser1981 (catalog number 2152) were obtained from Epitomics (Burlingame, CA). For Western blot analysis, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. The anti-HPV-18 E7 goat polyclonal (catalog number sc-1590), anti-JNK (catalog number sc-7345), and HRP-conjugated anti-goat secondary antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Phosphorylated JNK was detected by Anti-ACTIVE JNK (Promega Corp., V7931). For simplicity, “phospho” is indicated by “p” in the article.

Indirect Immunofluorescence and DNA Fluorescence in Situ Hybridization

Epithelial raft cultures were fixed in 10% buffered formalin, paraffin-embedded, and cut into 4-μm thin sections. After graded hydration, the tissue sections were subjected to antigen retrieval by heating at 98 °C for 10–15 min in 10 mm sodium citrate (pH 6.0). They were probed with primary antibodies for multiplexed antigen detection using tyramide-conjugated fluorophores. The specimens were treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide between each antibody probing to quench endogenous HRP and previous HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies. Primary antibodies were applied overnight at 4 °C and then probed with a 1:200 dilution of HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (G21040, Invitrogen) or anti-rabbit IgG (G21234, Invitrogen) for 1 h at room temperature. Bound secondary antibody was detected by treating with tyramide-FITC (NEL701A001KT), tyramide-Cy3 (NEL704A001KT), or tyramide-Cy5 (NEL705A001KT) as per the manufacturer's instructions (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Following protein antigen detection, DNA fluorescence in situ hybridization to detect HPV-18 genomic plasmid DNA was performed as described (7, 13). Briefly, tissue sections were heated to denature the DNA, treated with RNase A (100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37 °C, and then incubated overnight at 37 °C with biotinylated, nick-translated HPV-18 DNA probes. Following several washings in SSC, hybridized probes were detected by tyramide-FITC or tyramide-Cy3 (PerkinElmer Life Sciences). Slides were mounted with DAPI-containing mounting medium (H1200, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Images were captured with an Olympus AX70 microscope using Axiovision image capture software and processed with Adobe Photoshop CS2.

Western Blots

Lysates of raft tissues were prepared as described (5) with minor changes, using mammalian cell lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 100 mm NaCl, 10 mm NaF, 0.5% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with 2 mm DTT, 1 mm Na3VO4, protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma catalog number P8340), freshly added 1 mm PMSF, and phosphatase inhibitor mixture (PhosStop, Roche Applied Science). Lysates were briefly sonicated before clearing debris by high speed centrifugation at 4 °C. Total protein of 300 μg from each lysate was resolved using 12% SDS-PAGE, blotted on nitrocellulose membranes, and probed overnight with primary antibodies at 4 °C. Bound antibody was detected by enhanced chemiluminescence (ECL, GE Healthcare) after probing with HRP-labeled secondary antibody. Lysates of subconfluent submerged cultures of asynchronized HeLa cells and subconfluent HeLa cells treated with hydroxyurea (50 nm, 24 h) or nocodazole (50 microgram/ml) were used as references for the detection of HPV-18 E7 or various host proteins.

RESULTS

HPV-18 E7 Protein Induces Cytoplasmic Cyclin B1 Accumulation in Differentiated Strata of PHK Raft Cultures

PHKs were retrovirally transduced with the empty vector-only virus, the HR HPV-18 E7 (18E7), or mutations therein, each under control of the HPV-18 enhancer-promoter contained in the upstream regulatory region. The transduced cells were developed into organotypic raft cultures. Bromodeoxyuracil (BrdU) incorporation over the final 6–12 h before harvesting marked cells recently in S phase. Thin sections of formalin-fixed and paraffin-embedded raft cultures were simultaneously probed for cyclin B1 and BrdU by using indirect immunofluorescence microscopy (Fig. 1A, upper panels).

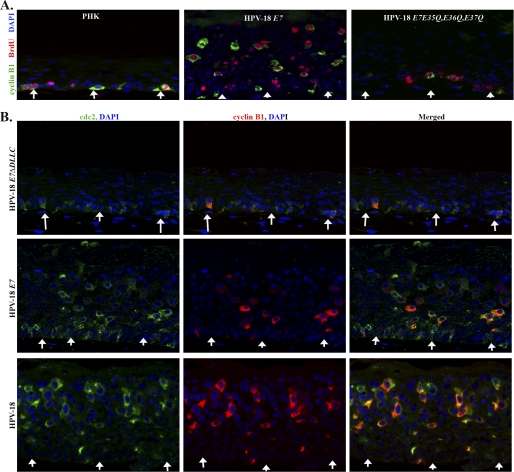

FIGURE 1.

HPV-18 E7 and genomic HPV-18 plasmid induce elevated expression of cyclin B1 and cdc2 in the differentiated strata of PHK raft cultures. A, double indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was performed to detect cyclin B1 (green) and BrdU (red) in organotypic raft cultures of PHK (left panel), HPV-18 E7 wild type (middle panel), and HPV-18 E7E35Q,E36Q,E37Q (right panel). B, cdc2 (green) and cyclin B1 (red) in raft cultures of HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC (upper row), the wild type HPV-18 E7 (middle row), and HPV-18 genomic plasmid-containing raft cultures (lower row). ΔDLLC and E35Q,E36Q,E37Q are mutations of HPV-18 E7 lacking the pocket protein binding site or CKII motif, respectively. In this figure and Figs. 3 and 5, images were captured at ×20 magnification and arrowheads indicate the basal layer of the epithelia. All the raft cultures shown here are 10 days old.

High cytoplasmic cyclin B1 signals were observed in about 50% of the BrdU-positive cells in the differentiated strata of the E7 cultures (Fig. 1A, middle panel). Cells that were BrdU-positive but cyclin B1-negative might not have progressed to late S phase when cyclin B1 is known to be synthesized (14). Cells positive for cyclin B1 but negative for BrdU could be those that had long exit the S phase. In addition, there was a population of differentiated cells that were negative for both, representing those that did not reenter S phase; this failure has been attributable to the inactivation of cyclin E/cdk2 by p27kip1 or p21cip1 (see Ref. 15 and references therein). We also tested raft cultures transduced with E7E35Q,E36Q,E37Q. Unable to bind and phosphorylated by CKII, this mutant form of 18E7 does not destabilize p130 to a sufficient extent to enable S phase reentry (6, 9). In these cultures, BrdU and cyclin B1 signals were restricted to the basal cells (Fig. 1A, right panel), as in normal PHK raft cultures (Fig. 1A, left panel). This phenotype was also observed in PHK raft cultures transduced with an empty retrovirus or E7 with a mutation or a deletion in the pocket protein binding motif (C27S, ΔDLLC) (data not shown, but see Figs. 1B and 4D). Thus, the ability of 18E7 to induce high levels of cytoplasmic cyclin B1 in suprabasal cells is dependent on its ability to induce S phase reentry. Because the suprabasal cyclin B1 signals in the 18E7 raft cultures were significantly elevated relative to those in the cycling basal cells, we suggest that the differentiated cells had a protracted G2 phase. In the experiments described below, we examined the mechanisms responsible for this phenotype using raft cultures of PHKs transduced with 18E7 or in productive PHK raft cultures harboring HPV-18 genomic plasmids. We will call these cultures collectively “HPV raft cultures,” whereas raft cultures of PHKs transduced with empty retrovirus or untransduced PHKs as “control raft cultures.”

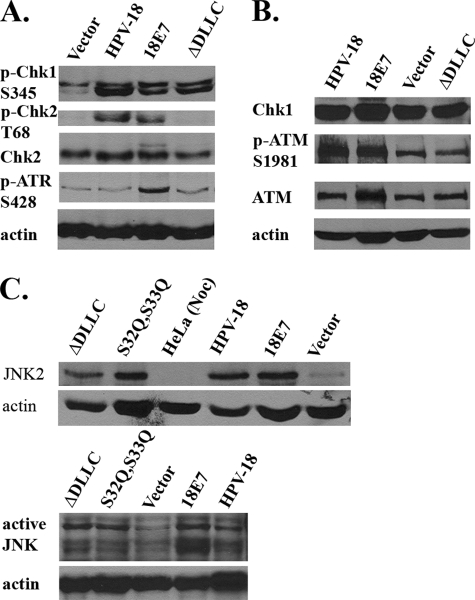

FIGURE 4.

HPV-18 E7 and genomic HPV-18 plasmid activate kinases responsible for cdc25C phosphorylation on Ser216. Immunoblot analysis of (A) p-ATR Ser428, p-Chk1 Ser345, total Chk2, and p-Chk2 Thr68 and (B) ATM, p-ATM Ser1981, total Chk1 from lysates of raft cultures harboring empty vector (Vector), HPV-18 genomic plasmid, or expressing HPV-18 E7 (18E7) or HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC (ΔDLLC) mutation; C, JNK2 and phosphorylated JNKs in raft cultures harboring the vector-only (Vector), HPV-18 E7 (18E7), E7ΔDLLC (ΔDLLC), E7S32Q,E33Q (S32Q,S33Q), or HPV-18 genomic plasmids. HeLa(Noc) denotes lysates from nocodazole-treated HeLa as negative control for JNK2.

HPV-18 E7 Induces Cytoplasmic cdc2 in the Differentiated Cells

Typically, cyclin B1 is retained in the cytoplasm during S/G2. G2/M transition requires the activation and nuclear import of the cyclin B1-cdc2 complex. To investigate the cause for the 18E7-induced prolonged G2, we probed raft culture sections for synthesis and localization patterns of cdc2 relative to cyclin B1 by indirect immunofluorescence. In raft cultures expressing E7ΔDLLC (Fig. 1B, top row), a weak cdc2 signal co-localized with a weak cyclin B1 in some basal cells. The signals were detected either in the nucleus or cytoplasm, as expected of cycling cells. No signals were detected in suprabasal cells. Similar expression patterns for cyclin B1 and cdc2 were detected in control raft cultures (data not shown). In contrast, the wild type HPV-18 E7 induced not only cytoplasmic cyclin B1 in spinous cells, it also induced cytoplasmic cdc2 (Fig. 1B, middle row). About 50–60% cdc2-positive suprabasal cells were also positive for cyclin B1, whereas all cyclin B1-positive cells were positive for cytoplasmic cdc2. Only about 10% of cyclin B1-positive cells had the signal detected in the nucleus, whereas only 2.4% had both cyclin B1 and cdc2 in the nucleus. Because S phase reentry is necessary for suprabasal cyclin B1 and cdc2 accumulation (Fig. 1, A, right panel, and B, top row), cells positive for cyclin B1 or cdc2 were recently in S phase. Simultaneous probing for BrdU and cdc2 showed that this was indeed the case (data not shown).

Raft cultures of HPV-18 genomic plasmid-containing PHKs, in which a productive program was taking place, were also positive for cytoplasmic cdc2, in addition to cyclin B1 in a subset of differentiated strata (Fig. 1B, lower row). As with E7 raft cultures, all cyclin B1-positive cells were also positive for cytoplasmic cdc2, while about 80% of cdc2-positive cells had colocalizing cyclin B1. Only 1% cyclin B1-positive cells exhibited a nuclear or pan-cellular signal, but none showed nuclear colocalization of cyclin B1 and cdc2. As with cyclin B1, in either HPV raft culture, the levels of cdc2, when detected, were much higher than those in the basal cycling cells, suggesting a prolonged G2 phase during which both cyclin B1 and cdc2 accumulated in the cytoplasm.

HPV-18 E7 Induces Inhibitory Phosphorylation of cdc2 in PHK Raft Cultures

In addition to the requirement for cyclin B1, the activity of cdc2 is controlled by kinases and phosphatases (16–18). Cdc2 has many potential phosphorylation sites, among which three have been characterized in detail. Kinase-active cdc2 is phosphorylated on Thr161 but not on Thr14 and Tyr15. During interphase, cdc2 is phosphorylated by CAK/cdk7 on Thr161 but is rendered inactive by Myt1- and Wee1-mediated phosphorylation on Thr14, Tyr15, or both. To promote G2-M transition, the kinase function of cdc2 is activated by protein phosphatases cdc25B and –C, which removes inhibitory phosphorylations. The multiple cdc2 isoforms can be detected by phospho-specific antibodies (Refs. 19–21 and references therein). To assess whether cdc2 might be inactivated by hyperphosphorylation, we examined cdc2 in raft culture lysates by immunoblotting with antibodies to the total cdc2 and those specific for various phosphorylated cdc2 (p-cdc2).

HeLa cells are cervical carcinoma cells that actively express HPV-18 E6 and E7 genes. As references, we used lysates from asynchronous HeLa cultures and HeLa cells enriched in the G1/S phase with hydroxyurea or in M phase after treatment with nocodazole. FACS analysis verified the effects of the treatments (Fig. 2A). Using Western blots, we first confirmed expression of the HPV-18 E7 protein in HeLa cells (Fig. 2B) and HPV raft cultures. E7 was detected in all except the control raft cultures. The presence of E7 correlated with elevated cyclin B1 and cdc2 relative to the control lysates (Fig. 2, B and D). Because of the many additional potential phosphorylation sites and the close migration rates of the bands, we are not able to determine with absolute certainty how the cdc2 protein in each band was phosphorylated. We shall call the fastest band reactive with phospho-specific cdc2 antibodies hypophosphorylated, being phosphorylated on at least one of the three well characterized substrates, whereas the slower bands represented hyperphosphorylation on at least two or perhaps all three known substrates.

FIGURE 2.

HPV-18 E7 and genomic HPV-18 plasmid dysregulate cell cycle regulatory proteins favoring a G2 phase milieu. A, FACS analysis of HeLa cells without any treatment or treated with hydroxyurea (HU) to enrich cells in S phase or with nocodazole (Noc), which enrich cells in M. B–E, Western blot analysis of lysates from asynchronous (AS) HeLa, hydroxyurea-treated HeLa, vector-transduced raft culture (Vector), HPV-18 E7-expressing raft culture (18E7), PHK raft culture containing amplifying HPV-18 genomic plasmids (HPV-18), PHK control raft culture (PHK), and Noc-treated HeLa. B, immunoblots showing steady state levels of HPV-18 E7, cyclin B1, p-cdc2 Thr14, and p-cdc2 Thr161. C, steady state expression levels of p-cdc2 Tyr15 and p-cdc2 Thr161. D, steady state expression levels of cdc2 and phospho-histone Ser10 (p-H3S10). E, steady state expression level of Wee1. F, steady state expression level of unphosphorylated Myt1 (upper panel) and phosphorylated Myt1 (middle panel). B–D and F represent 4 different gels. C and E are from the same gel. The blot represented in panel B was probed, stripped, and reprobed with different antibodies. Actin was used as a protein loading control.

The lysates of the two HPV raft cultures gave virtually identical results with regard to the various p-cdc2 isoforms (Fig. 2, B–D). Relative to the two control raft cultures, the steady state levels of hyperphosphorylated and hypophosphorylated cdc2 isoforms were elevated. The p-cdc2 Thr14-reactive isoforms were, however, distinct in that there was a higher relative abundance in the fastest moving hypophosphorylated isoform, relative to all other lysates (Fig. 2B). Antibodies to p-cdc2 Thr161 detected two weak bands in the HPV raft cultures (Fig. 2B). The isoforms reactive with the p-cdc2 Tyr15 antibody were similar to asynchronous HeLa cells and hydroxyurea-treated HeLa cells (Fig. 2C). Importantly, none of the p-cdc2 isoforms detected in the HPV raft cultures resembled those present in nocodazole-treated HeLa cells that exhibited weak p-cdc2 Thr14 and p-cdc2 Tyr15 bands but a strong unique p-cdc2 Thr161 band (Fig. 2, B and C). These patterns of cdc2 phosphorylation in nocodazole-treated HeLa cells agree with the report that, during mitosis, p-cdc2 Thr161 predominates (19). These results indicate that a significant fraction of cdc2 up-regulated by E7 is hyperphosphorylated on Thr14, Tyr15, and Thr161. Even the hypophosphorylated isoform bore inhibitory phosphorylation on Thr14 (Fig. 2B).

HPV-18 E7 Up-regulates Myt1 and Wee1 Expression in the PHK Raft Cultures

Inhibitory phosphorylation of cdc2 on Tyr15 is carried out by Wee1 in the nucleus (22). Western blot analysis revealed elevated Wee1 expression in the 18E7 raft cultures relative to all three HeLa cell extracts, whereas the control raft cultures had no signal. The HPV-18 genome-containing raft cultures had a signal comparable with the asynchronous HeLa cells (Fig. 2E). Myt1 is a dual specificity cytoplasmic membrane-associated kinase that phosphorylates cdc2 on Thr14 and Tyr15 residues, with a greater preference for Thr14 (20, 21, 23, 24). The Myt1 level was elevated in both HPV raft cultures relative to the PHK control raft culture (Fig. 2F, upper panel). As expected, the Myt1 level was very low in nocodazole-treated HeLa. During mitosis, Myt1 activity is inhibited when it is hyperphosphorylated by several kinases, such as cdc2, AKT, p90 RSK, and Plk1 (25–27). Immunoprobing with p-Myt1 Ser83-specific antibody detected a strong slower migrating band in nocodazole-treated HeLa cells. This band intensity was very low in the control and E7 raft cultures but undetectable in the HPV-18 raft cultures (Fig. 2F, middle panel). This inability to detect high p-Myt1 Ser83 in HPV raft cultures is in agreement with the absence or near absence of histone 3 phosphorylated on Ser10 (p-H3 Ser10), a marker of mitotic cells, in the HPV raft cultures (Fig. 2D). Collectively, the elevated active Wee1 or Myt1 in HPV raft cultures could then cause inhibitory phosphorylation on cdc2.

HPV-18 E7 Induces Cytoplasmic Accumulation of p-cdc25C Ser216 in Differentiated Strata

During the G2 to M transition, cdc2 is dephosphorylated on Thr14 and Tyr15 by cdc25B in the cytoplasm and cdc25C in the nucleus, thereby activating the cdc2-cyclin B complex to trigger mitosis (28–32). The cdc25C phosphatase is inactivated by phosphorylation on Ser216 (p-cdc25C Ser216); binding to the 14-3-3 protein then results in its export from the nucleus and retention in the cytoplasm (33–35).

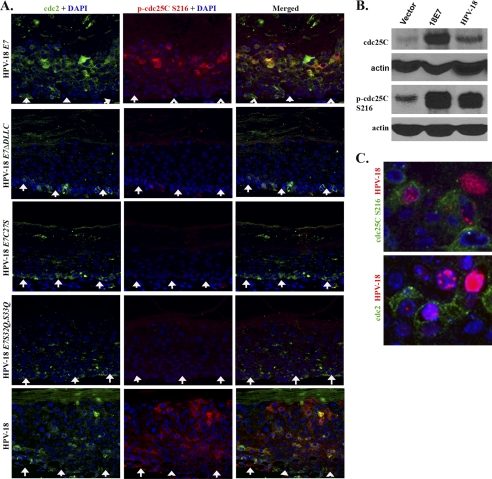

Indirect double immunofluorescence analysis revealed an induction of cytoplasmic p-cdc25C Ser216 in a significant subset of differentiated cells in E7-expressing raft cultures and the signals often colocalized with cdc2 (Fig. 3A, top row) or BrdU (data not shown), indicating that the cells were currently or recently in S phase. In contrast, there was no signal in differentiated strata of raft cultures expressing HPV-18 E7 proteins, which have inactivating mutations in the pocket protein binding domain (ΔDLLC, C27S) or in CKII substrates (S32Q,S33Q). Only some basal cells have weak signals. As before (Fig. 1B), cdc2 was detected only in the basal layer of cycling cells in HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC raft cultures. However, increasingly more frequent suprabasal cells were additionally positive for cytoplasmic cdc2 in cultures expressing E7C27S and E7S32Q,S33Q (Fig. 3A, compare bottom second, third, and fourth rows). We have previously reported that HPV-18 E7 mutations in the CKII domain are less efficient in p130 degradation than the wild type (6). The present observation is consistent with the notion that this mutation still maintains a low level of activity even though it was unable to induce S phase reentry in the differentiated keratinocytes. As with HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC, weak signals of cdc2 and p-cdc25C Ser216 were observed in some basal cells in control PHK or in vector-only raft cultures (data not shown). In HPV-18 genome-containing raft cultures, suprabasal p-cdc25C Ser216 invariably colocalized with cdc2 (Fig. 3A, bottom row). Signals for p-cdc25C Ser216 in basal cells were weak in HPV raft cultures.

FIGURE 3.

HPV-18 E7 and genomic HPV-18 plasmid induce changes in the expression and phosphorylation status of the cdc25C phosphatase. A, indirect immunofluorescence microscopy was used to detect the expression and localization of p-cdc25C Ser216 (red) relative to cdc2 (green) in raft cultures of HPV-18 E7, HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC, HPV-18 E7C27S, HPV-18 E7S32Q,S33Q, and HPV-18 genomic plasmids. B, immunoblot analysis were performed on lysates from vector-only PHK raft cultures, HPV-18 E7-expressing raft cultures, and HPV-18 raft cultures to assess total cdc25C and the phosphorylated cdc25C Ser216. C, simultaneous indirect immunofluorescence and HPV-18 DNA fluorescent in situ hybridization to detect HPV-18 DNA amplification (red) relative to p-cdc25C Ser216 (green) or cdc2 (green). E7C27S is mutated in the pocket protein binding motif, whereas S32Q,S33Q is mutated in the CKII substrates. Raft cultures in A and B are 10 days old and raft culture in C is 12 days old.

Western blot analysis revealed elevated levels of total cdc25C in HPV raft cultures relative to the vector-only transduced raft cultures (Fig. 3B). A higher expression of cdc25C was detected in 18E7 raft cultures relative to the HPV-18 raft cultures. However, the levels of the inactive p-cdc25C Ser216 were robustly elevated in both HPV raft cultures compared with vector-transduced cultures (Fig. 3B). The high levels of cytoplasmic p-cdc25C Ser216 would then account for the abundance of hyperphosphorylated, kinase-inactive cdc2 and the absence or near absence of p-H3 Ser10 in the HPV raft cultures (Fig. 2D).

We next examined the HPV-18 genome-containing PHK raft cultures for the expression of p-cdc25C Ser216 with respect to HPV plasmid amplification. In the differentiated strata, cytoplasmic p-cdc25C Ser216 was detected in cells with relatively weak viral DNA signals, whereas cells with high HPV-18 DNA were negative for p-cdc25C Ser216 (Fig. 3C). A similar observation was made while detecting cdc2 and HPV-18 genomic plasmids (Fig. 3D). We have shown previously that, upon extensive HPV-18 genome amplification, the E7 activity diminishes and ultimately extinguishes (7). The present data indicate that, in cells with high viral DNA, the induction of cdc2 and p-cdc25C Ser216 is also shut off.

HPV18 E7 Induces Phosphorylation of Chk1, Chk2, and JNK in Raft Cultures

DNA tumor virus infection induces DNA damage responses (DDR), resulting in ATM-, ATR-mediated phosphorylation and activation of Chk1 and Chk2 (36–41). Previously, HPV-16 E7 has also been reported to induce phosphorylated ATM and apoptosis in human fibroblasts (42). These kinases can inactivate cdc25C via phosphorylation on Ser216 (35, 43). To examine these possibilities, we performed immunoblot analysis on raft culture lysates. The results revealed elevated levels of p-Chk1 Ser345 and p-Chk2 Thr68 in HPV cultures, relative to cultures transduced with the empty vector (Fig. 4A), whereas there was no significant difference in total Chk1 (Fig. 4B) or Chk2 (Fig. 4A) levels among the cultures. Unexpectedly, in cultures transduced with HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC, there was an elevated p-Chk1 Ser345, whereas there was no increase in the total Chk1, the total Chk2, or the p-Chk2 Thr68 relative to the vector transduced cultures (Fig. 4, A and B).

Activated JNK has also been implicated in the inactivating phosphorylation of cdc25C on Ser168 in G2 or induction of the G2/M checkpoint upon DNA damage (44). We detected, relative to the vector-transduced raft cultures, an elevated level of a ∼54 kDa protein in HPV raft cultures using an anti-JNK 1–3 specific antibody (Fig. 4C). Based on molecular mass, this band most likely represents JNK2. Interestingly, the induction was observed with mutated forms of E7 as well. The S32Q,S33Q mutant form was as effective as the wild type, whereas the ΔDLLC mutation was much less so. This distinction between the two mutant forms might be attributable to the observation that mutation in the CKII recognition or target sequence of E7 reduces but does not abolish its ability to bind and destabilize p130, whereas the ΔDLLC mutation has a highly attenuated ability to target p130 (6). A phospho-JNK specific antibody detected elevated levels of multiple bands, possibly representing phosphorylated forms of multiple JNK proteins (between 50 and 60 kDa) in each of raft cultures expressing the E7 protein, either wild type or mutations (Fig. 4C).

HPV-18 Raft Cultures Have Elevated Phosphorylated ATM Ser1981

We next examined the levels of ATM and ATR, as Chk1 and Chk2 are phosphorylated by these kinases. Phosphorylated ATM also activates JNK, independent of Chk1/2 phosphorylation (45). Elevated total ATR (data not shown) and phosphorylated ATR (p-ATR Ser428) (Fig. 4A) were detected in the immunoblot analysis of HPV-18 E7 raft cultures, but not in HPV-18 raft cultures, when compared with control raft cultures transduced with vector-only or E7ΔDLLC. Interestingly, relative to the two above mentioned reference cultures, HPV-18 E7 induced both total ATM and p-ATM Ser1981, whereas the HPV-18 raft cultures elevated the p-ATM Ser1981, but there was little effect on the total ATM (Fig. 4B).

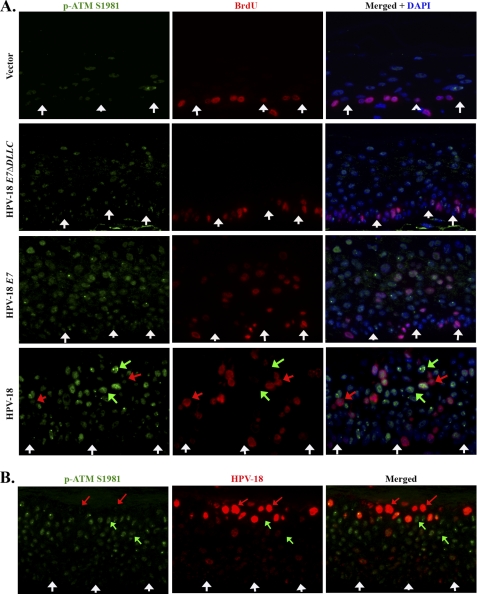

To corroborate these Western blots, we examined p-ATM Ser1981 along with BrdU incorporation in raft cultures by indirect immunofluorescence. There was a low level of nuclear phospho-ATM Ser1981 in some differentiated cells in the vector-only control raft cultures (Fig. 5A, upper row). Even though Western blot did not reveal a clearly discernable elevation in p-ATM Ser1981 in E7ΔDLLC expressing raft cultures, immunofluorescence revealed an increase in the number of weakly positive cells (Fig. 5A, second row). In both E7 and HPV-18 raft cultures, p-ATM Ser1981 was detected in the majority of cells throughout the entire cultures, including basal cells, and the signals were also strong in many of the cells (Fig. 5A, bottom two rows). Because of the diffuse presence of p-ATM, most BrdU-positive cells were also positive for p-ATM, but some cells with strong BrdU signals had low or barely detectable p-ATM (for example, see Fig. 5A, red arrows in last row). Conversely, many strong p-ATM containing cells did not show concomitant S phase reentry (Fig. 5A, green arrows in last row). Thus, the elevation of p-ATM appeared to be a general cellular response to HPV E7 expression, but was not necessarily associated with S phase reentry.

FIGURE 5.

A, indirect immunofluorescent detection of p-ATM Ser1981 (green) and S phase reentry (BrdU incorporation, red) in vector-only transduced PHK raft culture (top row), HPV-18 E7ΔDLLC mutation-expressing raft culture (second row), HPV-18 E7-expressing raft culture (third row), and HPV-18 plasmid containing raft culture (fourth row). In the last row, the red arrow indicates the high BrdU and low p-ATM Ser1981, whereas the green arrow points to high p-ATM Ser1981 but low or no BrdU incorporation. B, p-ATM Ser1981 expression relative to HPV-18 plasmid amplification was revealed by combined indirect immunofluorescence and HPV-18 DNA fluorescent in situ hybridization. Red arrow indicate high HPV-18 DNA and low or no p-ATM Ser1981, whereas the green arrow points to the high p-ATM Ser1981 but low or no HPV-18 plasmid. Raft cultures in A are 10 days old and raft culture in B is 12 days old.

We also probed for the relative distribution of p-ATM Ser1981 and HPV-18 viral DNA (Fig. 5B). As before, p-ATM Ser1981 was diffusely detected, whereas high copies of viral DNA was primarily observed in the more superficial strata. In fact, many of these latter cells were negative for p-ATM Ser1981.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we demonstrate that HPV-18 E7 expression alone creates a cellular milieu consistent with a prolonged G2 phase after it has induced S phase reentry in differentiated cells of PHK raft cultures. Western blots and indirect immunofluorescence of HPV-18 E7 raft cultures revealed the following. 1) cdc2 and cyclin B1 were elevated and localized to the cytoplasm (Fig. 1). 2) The cdc2 phosphorylation signature of HPV-18 E7-expressing raft cultures is that of kinase-inactive isoforms, resembling more closely to those present in hydroxyurea-treated HeLa cells unable to enter mitosis than to cells arrested in mitosis with nocodazole (Fig. 2). Specifically, cdc2 was phosphorylated on Tyr15, Thr14, and significantly less so on Thr161 in HPV raft cultures. Even the hypophosphorylated cdc2 was phosphorylated on Thr14. In contrast, in nocodazole-treated HeLa cells, p-cdc2 Thr161 is the predominant form (Fig. 2). 3) There was elevated expression of Wee1 and Myt1, kinases that inactivated cdc2 by phosphorylation on Thr14 and Tyr15 (Fig. 2). Also, there was undetectable or very low amounts of the kinase inactive p-Myt1, which was present at high levels in nocodazole-treated HeLa cells (Fig. 2). These results are consistent with our previous findings from Affymatrix microarray analysis that transcription of CDC2, CYCLIN B1, and Wee1 was elevated by 3–6-fold in HPV-18 E6/E7 raft cultures (46). 4) The total phosphatase cdc25C and the inactive form with phosphorylated Ser216 were elevated by HPV-18 E7. Moreover, the inactive form was sequestered in the cytoplasm in cells that were also positive for cdc2 or cyclin B1 (Fig. 3). 5) The levels of activated Chk1, Chk2, and JNKs, which are known to phosphorylate and inactivate cdc25C, were elevated relative to control raft cultures (Fig. 4). 6) Finally, HPV-18 E7 induced elevated p-ATR and p-ATM (Fig. 4), which can phosphorylate and activate Chk1, Chk2, and JNKs (45). Interestingly, even the mutated HPV-18 E7 proteins that are unable to promote S phase reentry (6, 9) induced p-Chk1, p-JNK (Fig. 4), and to a much lesser extent, p-ATM (Fig. 5A). These E7 activities might be independent of pocket protein binding and destabilization.

Thus, HPV-18 E7 orchestrates, in the suprabasal differentiated cells, a wide range of biochemical changes responsible for the inactivating phosphorylation of cdc2 on Thr14 and Tyr15 by elevated Wee1 and Myt1 as well as the inactivating phosphorylation of the induced cdc25C by Chk1, Chk2, JNK, and ATM kinases that are also activated by HPV-18 E7. The cascade of events then leads to the cytoplasmic accumulation of the kinase-inactive cdc2-cyclin B1 complex (Fig. 1) and phosphatase-inactive p-cdc25C Ser216, characteristics of cells arrested in G2 by UV irradiation (47, 48). Consistent with an inactive cyclin B1-cdc2 complex, the mitotic marker protein, histone 3 phosphorylated on Ser10 was very low or below detection in HPV raft cultures (Fig. 2D). Indeed, we observe very few mitotic figures in the HPV-18 E7 raft cultures. Moreover, many of the differentiated cells in H18 E7 raft cultures had an enlarged nucleus or appeared multinucleated, consistent with an aberrant G2-M transition (8).

The above observations are biologically relevant as most of them are also made with PHK raft cultures that harbor the HPV-18 genome undergoing productive amplification. There are only two exceptions: the absence of p-ATR up-regulation (Fig. 4) and a very low level of Myt1 induction (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, the hyperphosphorylation patterns of cdc2 were identical to those present in HPV-18 E7 raft cultures (Fig. 2). These data support and provide an explanation to our previous report that it is during this window of a prolonged G2 phase that HPV DNA amplification takes place (7).

Some of the differences between the two HPV raft cultures might be attributable to the reduction and eventual loss of E7 activity in HPV-18 containing cultures in the mid and upper spinous cells upon viral DNA amplification (7). This loss of E7 activity is reflected in the reappearance of nuclear p130 and the loss of nuclear cyclin A and proliferating cell nuclear antigen and cytoplasmic cyclin B1, as well as the absence of BrdU incorporation in these cells (7). Consistent with these earlier observations, in this study, we also observed a reduction or loss of cdc2, p-cdc25C Ser216, and p-ATM Ser1981 in cells with high viral DNA content (Figs. 3 and 5).

We have also examined a functionally inducible LR HPV-11 E7 fused to the ligand binding domain of the estrogen receptor (ER) (4) and found that it too induced cytoplasmic cyclin B1 in differentiated keratinocytes in PHK raft cultures (supplemental Fig. S1). We infer that the induction of prolonged G2 in differentiated cells is a property shared by both HR and LR HPV E7 to facilitate viral DNA amplification.

HPV-18 containing raft cultures also experienced prolonged G2, but had a more consistent colocalization of cdc2 with cyclin B1 or p-cdc25C Ser216 than HPV-E7 raft cultures (Fig. 4). It is possible that the viral E1∧E4 protein may have played a role. E1∧E4 is encoded by a spliced mRNA consisting of the first 5 amino acid codons of E1 fused to the E4 open reading frame. It is an abundant cytoplasmic protein and often colocalizes with the viral major capsid protein (49, 50). A number of reports concluded that in submerged cultures of cell lines, ectopically expressed E1∧E4 of several HPV types can sequester cyclin B1/Cdc2 to the cytokeratin filaments, causing G2 arrest (for a review, see Ref. 51) and that Wee1 plays a role (52 and references therein). Our recent data showed that viral DNA amplification was initiated in cells with elevated cytoplasmic cyclin B1, the accumulation of which, however, preceded the appearance of the E1∧E4 protein by some 2 or more days (50). Furthermore, the upper spinous cells with high copies of amplified viral DNA were negative for cyclin B1 but were strongly positive for the E1∧E4 protein. Consequently, the cyclin B1 and E1∧E4 proteins rarely colocalize. This temporal and spatial relationship concerning cytoplasmic cyclin B1 induction, viral DNA amplification, and E1∧E4 accumulation are inconsistent with a major causative role of the E1∧E4 protein in the prolonged G2 phase in the raft cultures, in agreement with a recent report (52). Our present study demonstrates that E7 alone can trigger a milieu characteristic of a G2 phase by inducing inhibitory phosphorylation on cdc2 and cdc25C. However, we cannot rule out that a low level of E1∧E4 not previously detected in our study did assist E7 in prolonging G2. This E1∧E4 effect could then be instrumental in further reducing a p-H3 Ser10 to an undetectable level in the HPV-18 containing raft cultures (Fig. 2).

Interestingly, a number of other viruses also induce G2 arrest. In particular, the Vpr protein of HIV type 1 and p30 protein of HTLV-1 do so by inducing inhibitory phosphorylation of cdc25C (53–55). This has been attributed to the activation of ATM/ATR- and Chk1/Chk2-dependent pathways. Replication of SV40, mouse polyomaviruses, and minute virus of canines also benefits by activation of DDR (56–60). The activation of DDR mediated by ATM, Chk2, and Chk1 have been reported in HPV-31 containing human keratinocytes induced to differentiate by Ca2+ in submerged cultures, but the viral protein responsible was not identified (38). In the present work we show that HPV-18 E7 alone can elicit DDR-like responses in raft cultures of human keratinocytes characterized by the activation of ATM, ATR, Chk1, Chk2, and JNKs, leading to inactivation of cdc25C. Our observations agree with Rogoff et al. (42) who reported that 16E7 induces DDR in fibroblasts. However, unlike their studies, there were no apoptotic cells in our HPV raft cultures (7). In summary, in addition to E7-induced DDR, our study has uncovered additional mechanisms involving the dysregulation of cyclin B1, cdc2, Myt1, Wee1, and cdc25C by the E7 protein.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the nurses in the University of Alabama Newborn Well-Baby Nursery for collecting neonatal foreskins following voluntary circumcision. We thank Dr. Nicholas Genovese for sharing previously characterized raft cultures expressing HPV-11 E7-ER presented in supplemental Fig. S1.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant CA83679.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Fig. S1.

- HPV

- human papillomavirus

- PHK

- primary human keratinocytes

- ATM

- ataxia telangiecstasia-mutated kinase

- ATR

- ataxia telangiecstasia and Rad3-related kinase

- Chk

- checkpoint kinase

- DDR

- DNA damage response

- HR

- high-risk

- LR

- low-risk

- CKII

- casein kinase II

- p-H3 Ser10

- histone 3 phosphorylated on Ser10

- p-cdc25C Ser216

- cdc25C phosphatase inactivated by phosphorylation on Ser216.

REFERENCES

- 1. de Villiers E. M., Fauquet C., Broker T. R., Bernard H. U., zur Hausen H. (2004) Virology 324, 17–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chow L. T., Broker T. R., Steinberg B. M. (2010) APMIS 118, 422–449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Cheng S., Schmidt-Grimminger D. C., Murant T., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (1995) Genes Dev. 9, 2335–2349 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Banerjee N. S., Genovese N. J., Noya F., Chien W. M., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2006) J. Virol. 80, 6517–6524 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Zhang B., Chen W., Roman A. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 437–442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Genovese N. J., Banerjee N. S., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 4862–4873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang H. K., Duffy A. A., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2009) Genes Dev. 23, 181–194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chien W. M., Noya F., Benedict-Hamilton H. M., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2002) J. Virol. 76, 2964–2972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chien W. M., Parker J. N., Schmidt-Grimminger D. C., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2000) Cell Growth Differ. 11, 425–435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Hardouin N., Nagy A. (2000) Genesis 26, 245–252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wilson J. L., Dollard S. C., Chow L. T., Broker T. R. (1992) Cell Growth Differ. 3, 471–483 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Banerjee N. S., Chow L. T., Broker T. R. (2005) Methods Mol. Med. 119, 187–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Van Tine B. A., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2005) Methods Mol. Biol. 292, 215–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pines J., Hunter T. (1991) J. Cell Biol. 115, 1–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Noya F., Chien W. M., Broker T. R., Chow L. T. (2001) J. Virol. 75, 6121–6134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taylor W. R., DePrimo S. E., Agarwal A., Agarwal M. L., Schönthal A. H., Katula K. S., Stark G. R. (1999) Mol. Biol. Cell 10, 3607–3622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Toyoshima F., Moriguchi T., Wada A., Fukuda M., Nishida E. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 2728–2735 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Solomon M. J., Lee T., Kirschner M. W. (1992) Mol. Biol. Cell 3, 13–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Atherton-Fessler S., Liu F., Gabrielli B., Lee M. S., Peng C. Y., Piwnica-Worms H. (1994) Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 989–1001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu F., Stanton J. J., Wu Z., Piwnica-Worms H. (1997) Mol. Cell. Biol. 17, 571–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liu F., Rothblum-Oviatt C., Ryan C. E., Piwnica-Worms H. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5113–5123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Parker L. L., Piwnica-Worms H. (1992) Science 257, 1955–1957 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mueller P. R., Coleman T. R., Kumagai A., Dunphy W. G. (1995) Science 270, 86–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kornbluth S., Sebastian B., Hunter T., Newport J. (1994) Mol. Biol. Cell 5, 273–282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Booher R. N., Holman P. S., Fattaey A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 22300–22306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Palmer A., Gavin A. C., Nebreda A. R. (1998) EMBO J. 17, 5037–5047 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nakajima H., Toyoshima-Morimoto F., Taniguchi E., Nishida E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 25277–25280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Coleman T. R., Dunphy W. G. (1994) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 6, 877–882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dunphy W. G., Kumagai A. (1991) Cell 67, 189–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Karlsson C., Katich S., Hagting A., Hoffmann I., Pines J. (1999) J. Cell Biol. 146, 573–584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Strausfeld U., Fernandez A., Capony J. P., Girard F., Lautredou N., Derancourt J., Labbe J. C., Lamb N. J. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 5989–6000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Strausfeld U., Labbé J. C., Fesquet D., Cavadore J. C., Picard A., Sadhu K., Russell P., Dorée M. (1991) Nature 351, 242–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dalal S. N., Schweitzer C. M., Gan J., DeCaprio J. A. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 4465–4479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Peng C. Y., Graves P. R., Thoma R. S., Wu Z., Shaw A. S., Piwnica-Worms H. (1997) Science 277, 1501–1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Peng C. Y., Graves P. R., Ogg S., Thoma R. S., Byrnes M. J., 3rd, Wu Z., Stephenson M. T., Piwnica-Worms H. (1998) Cell Growth Differ. 9, 197–208 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kudoh A., Daikoku T., Sugaya Y., Isomura H., Fujita M., Kiyono T., Nishiyama Y., Tsurumi T. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 104–115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Lilley C. E., Carson C. T., Muotri A. R., Gage F. H., Weitzman M. D. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5844–5849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moody C. A., Laimins L. A. (2010) Nat. Rev. Cancer 10, 550–560 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Stracker T. H., Carson C. T., Weitzman M. D. (2002) Nature 418, 348–352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shirata N., Kudoh A., Daikoku T., Tatsumi Y., Fujita M., Kiyono T., Sugaya Y., Isomura H., Ishizaki K., Tsurumi T. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30336–30341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhao X., Madden-Fuentes R. J., Lou B. X., Pipas J. M., Gerhardt J., Rigell C. J., Fanning E. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 5316–5328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rogoff H. A., Pickering M. T., Frame F. M., Debatis M. E., Sanchez Y., Jones S., Kowalik T. F. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 2968–2977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Sanchez Y., Wong C., Thoma R. S., Richman R., Wu Z., Piwnica-Worms H., Elledge S. J. (1997) Science 277, 1497–1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Gutierrez G. J., Tsuji T., Cross J. V., Davis R. J., Templeton D. J., Jiang W., Ronai Z. A. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 14217–14228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Wang Z., Wang M., Kar S., Carr B. I. (2009) J. Cell Physiol. 221, 213–220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Garner-Hamrick P. A., Fostel J. M., Chien W. M., Banerjee N. S., Chow L. T., Broker T. R., Fisher C. (2004) J. Virol. 78, 9041–9050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Herzinger T., Funk J. O., Hillmer K., Eick D., Wolf D. A., Kind P. (1995) Oncogene 11, 2151–2156 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Gabrielli B. G., Clark J. M., McCormack A. K., Ellem K. A. (1997) Oncogene 15, 749–758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Doorbar J., Foo C., Coleman N., Medcalf L., Hartley O., Prospero T., Napthine S., Sterling J., Winter G., Griffin H. (1997) Virology 238, 40–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Chow L. T., Duffy A. A., Wang H. K., Broker T. R. (2009) Cell Cycle 8, 1319–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Davy C., Doorbar J. (2007) Virology 368, 219–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Knight G. L., Pugh A. C., Yates E., Bell I., Wilson V., Moody C. A., Laimins L. A., Roberts S. (2011) Virology 412, 196–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Datta A., Silverman L., Phipps A. J., Hiraragi H., Ratner L., Lairmore M. D. (2007) Retrovirology 4, 49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Kino T., Gragerov A., Valentin A., Tsopanomihalou M., Ilyina-Gragerova G., Erwin-Cohen R., Chrousos G. P., Pavlakis G. N. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 2780–2787 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Yoshizuka N., Yoshizuka-Chadani Y., Krishnan V., Zeichner S. L. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 11366–11381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Dahl J., You J., Benjamin T. L. (2005) J. Virol. 79, 13007–13017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Shi Y., Dodson G. E., Shaikh S., Rundell K., Tibbetts R. S. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 40195–40200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Hein J., Boichuk S., Wu J., Cheng Y., Freire R., Jat P. S., Roberts T. M., Gjoerup O. V. (2009) J. Virol. 83, 117–127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boichuk S., Hu L., Hein J., Gjoerup O. V. (2010) J. Virol. 84, 8007–8020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Luo Y., Chen A. Y., Qiu J. (2011) J. Virol. 85, 133–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.