Abstract

Growth and remodeling of lymphatic vasculature occur during development and during various pathologic states. A major stimulus for this process is the unique lymphatic vascular endothelial growth factor-C (VEGF-C). Other endothelial growth factors, such as fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) or VEGF-A, may also contribute. Heparan sulfate is a linear sulfated polysaccharide that facilitates binding and action of some vascular growth factors such as FGF-2 and VEGF-A. However, a direct role for heparan sulfate in lymphatic endothelial growth and sprouting responses, including those mediated by VEGF-C, remains to be examined. We demonstrate that VEGF-C binds to heparan sulfate purified from primary lymphatic endothelia, and activation of lymphatic endothelial Erk1/2 in response to VEGF-C is reduced by interference with heparin or pretreatment of cells with heparinase, which destroys heparan sulfate. Such treatment also inhibited phosphorylation of the major VEGF-C receptor VEGFR-3 upon VEGF-C stimulation. Silencing lymphatic heparan sulfate chain biosynthesis inhibited VEGF-C-mediated Erk1/2 activation and abrogated VEGFR-3 receptor-dependent binding of VEGF-C to the lymphatic endothelial surface. These findings prompted targeting of lymphatic N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-1 (Ndst1), a major sulfate-modifying heparan sulfate biosynthetic enzyme. VEGF-C-mediated Erk1/2 phosphorylation was inhibited in Ndst1-silenced lymphatic endothelia, and scratch-assay responses to VEGF-C and FGF-2 were reduced in Ndst1-deficient cells. In addition, lymphatic Ndst1 deficiency abrogated cell-based growth and proliferation responses to VEGF-C. In other studies, lymphatic endothelia cultured ex vivo from Ndst1 gene-targeted mice demonstrated reduced VEGF-C- and FGF-2-mediated sprouting in collagen matrix. Lymphatic heparan sulfate may represent a novel molecular target for therapeutic intervention.

Keywords: Cell Surface Receptor, Endothelium, Growth Factors, Heparan Sulfate, Heparin-binding Protein

Introduction

Lymphatic vasculature mediates a variety of highly dynamic processes such as lymphangiogenesis (lymphatic vessel sprouting), transport of immune or neoplastic cells, and lymphatic endothelial hyper- or hypoplasia associated with lymphedema (1). In cancer, pathologic lymphangiogenesis in the tumor and regional lymph nodes increases lymphatic vascular conduit that contributes to nodal metastasis (2). Major effectors of pathologic lymphangiogenesis include the unique lymphatic vascular endothelial growth factor VEGF-C, and in some cases a homologue VEGF-D (1, 3), where binding of growth factor to the lymphatic endothelial receptor VEGFR-3 results in activation of lymphatic growth, survival, and migratory signaling (4, 5). These growth factors may also interact with VEGFR-2 and VEGFR-2/3 heterodimers (6, 7). The full-length VEGF-C protein interacts with VEGFR-3, although post-proteolytic processing of N- and C-terminal propeptides results in a mature form of the molecule with some affinity for VEGFR-2 in addition to affinity for VEGFR-3. Developmental lymphangiogenesis also depends on VEGF-C (1). In some cases, the angiogenic factors fibroblast growth factor-2 (FGF-2) as well as VEGF-A also contribute to lymphatic growth and remodeling through interactions with their cognate receptors FGFR and VEGFR-2 on lymphatic endothelium (8, 9). However, VEGF-C (and in some cases VEGF-D) binding and signaling via VEGFR-3 appears to function as the major lymphatic growth stimulus in most clinical states or in vivo models of pathologic lymphangiogenesis (reviewed in Refs. 1, 10).

It is now recognized that the interactions of some endothelial growth factors with their receptors on vascular endothelium are modulated by proteoglycans (11, 12). In neoplasia, heparan sulfate proteoglycans modulate angiogenesis through their ability to serve as co-receptors and matrix scaffolds for various soluble effectors, including VEGF-A, FGF-2, and platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), among others (11, 13). By virtue of unique sulfate modifications presented along heparan sulfate chains, such growth factors may cluster with cognate receptors in a way that facilitates ternary signaling complex formation. Whether and how lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate might mediate the direct actions of growth factors, including VEGF-C on the lymphatic cell surface has not been reported. One study has identified a pro-lymphangiogenic role for heparanase in tumor specimens, wherein overexpression of heparanase by tumor cells was associated with elevated VEGF-C expression and stimulation of tumor xenograft lymphangiogenesis in a mouse model (14). Although expression of the enzyme by tumor cells promotes expression of VEGF-C, it is also recognized that heparanase expression might contribute to the matrix release of multiple pro-lymphangiogenic growth factors that interact with heparan sulfate in extracellular matrix. Nevertheless, the importance of heparan sulfate on the lymphatic endothelial surface in mediating direct interactions with VEGF-C, and downstream lymphatic endothelial cell activation, remains to be examined.

In this study, we examine the role of lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate in mediating VEGF-C binding, growth activation, and migration as well as sprouting behavior by lymphatic endothelial cells. We demonstrate that heparan sulfate expressed by primary lymphatic endothelium binds to VEGF-C, and we present evidence that competitively interfering with lymphatic heparan sulfate using heparinoids or altering its presence on the cell surface, through enzymatic destruction or siRNA-mediated silencing of heparan sulfate chain biosynthesis, inhibits receptor-dependent VEGF-C binding and reduces Erk1/2-mediated growth activation. Unique sulfate modifications of the glycan appear to be critical for appropriate growth and sprouting responses to VEGF-C. Sulfation of nascent heparan sulfate initiates by the action of the enzyme N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-1 (Ndst-1) (reviewed in Ref. 15). We demonstrate that targeting Ndst1 in primary lymphatic endothelial cells results in reduced Erk1/2-mediated growth activation and altered lymphatic growth and proliferation responses to VEGF-C. These findings are complemented by the demonstration that genetic deletion of lymphatic endothelial Ndst1 results in reduced lymphatic sprouting in response to the same growth factors in collagen matrix.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Reagents

The following antibodies were used: for flow cytometry antibodies, Syrian hamster anti-mouse podoplanin (RDI Research Diagnostics) and rabbit anti-mouse LYVE-1 (Millipore); for immunofluorescence antibody, rabbit anti-human Prox-1 (Abcam); for proximity ligation assay antibodies, mouse anti-human VEGF-C (Angio-Proteomie) and rabbit anti-human VEGFR-3 (Reliatech); for Western blotting antibodies, rabbit anti-human antibodies against total as well as phosphorylated (Thr202/Tyr204) forms of Erk1/2 (Cell Signaling) and anti-human VEGFR-3 (Cell Signaling); for immunoprecipitation, anti-VEGFR-3 (anti-Flt4 clone, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and anti-phosphotyrosine (PY-20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibodies were used for immunoblotting. For growth factors, recombinant human FGF-2 (Invitrogen), human epidermal growth factor (EGF; R&D Systems), human VEGF-C (mature sequence, amino acids Thr103–Arg227, His10 C-terminal tag (R&D Systems) or amino acids Thr103–Arg227, His6-tagged at N/C termini (Biovision) were used. For all primary human lymphatic endothelial cell-based assays requiring VEGF-C stimulation, the R&D Systems product was used. Recombinant mouse VEGF-C (amino acids Thr99–Arg223, His6-tagged at N/C termini (Biovision)) was also used in binding assays. Biologic activity of the latter has been published previously (16). For heparin species, unfractionated commercial heparin (from porcine intestinal mucosa) was obtained from Scientific Protein Laboratories (SPL); and N-desulfated, 2-O-desulfated, and 6-O-desulfated heparins were obtained from Neoparin. Heparinase (heparin lyases I–III) was from IBEX. For siRNA, specific duplex sequences for siRNA targeting Ndst1, XylT2, or VEGFR-3 as well as scrambled duplex RNA (used as a control) were purchased from IDT Technologies.

Cells and Cell Lines

Primary human lung lymphatic endothelial cells (Lonza) were passaged less than 3 weeks from receipt, prior to cryo-storage. Cells were grown in EBM-2 medium (Lonza) in a 5% CO2-humidified incubator at 37 °C (standard culture) and were characterized by cell-surface CD31 and podoplanin expression. They were confirmed highly pure (>99%) at the third passage by immunofluorescence using Prox1 antibodies. For some studies, primary lymphatic endothelia were isolated from experimental oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions generated in mice using published methods (17).

Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting of Lymphatic Endothelial Cells

For fluorescence labeling, cells were harvested from culture (Accutase; Innovative Cell Technologies) and labeled with antibodies against podoplanin (1:200) or LYVE-1 (1:50) and appropriate fluorescent secondary antibodies prior to FACS (FACSCalibur; BD Biosciences).

Binding of Growth Factors to Lymphatic Heparan Sulfate

Primary LEC3 were labeled for 48 h with 37 μCi/ml H235SO4 (655 Ci/mmol; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in reduced sulfate Ham's F-12 medium (containing 10% dialyzed, filter-sterilized FBS). Purification of [35S]heparan sulfate from cultured cells was carried out as described previously (18). Binding of growth factor to purified [35S]heparan sulfate was tested using a nitrocellulose filter binding assay (19). For any given assay (in triplicate), 0.5 μg of growth factor was added to 10,000 cpm of purified [35S]heparan sulfate in 0.2 ml of PBS. After 10 min of incubation, the mixture was passed over a nitrocellulose membrane filter using a dot blot (Bio-Rad) and washed twice with 0.2 ml of PBS. Membrane dots were cut into scintillation tubes containing 1 ml of HS elution buffer (1 m NaCl, 25 mm sodium acetate, pH 6.0) and counted by liquid scintillation. Protein binding (membrane-bound cpm/μg protein) was normalized to that of FGF-2. Binding was also carried out in the presence of heparin (0.1 mg/ml). Other controls included binding to either the non-heparin-binding growth factor EGF (0.5 μg per incubation) or to BSA (1.0 μg per incubation).

Heparin Affinity Chromatography

Following preparation of spin columns (Bio-Rad) with bed volumes of 100 μl of heparin-Sepharose (GE Healthcare), columns were equilibrated in 0.15 m NaCl wash buffer. Growth factor (2 μg) was then added to each column in 100 μl of wash buffer. Successive step elutions (200 μl each) of increasing [NaCl] were then applied. Samples (10 μl) from each elution were then prepared in SDS sample buffer (5×; Thermo-Finnigan) with 5% β-mercaptoethanol, boiled, and applied to a 12% SDS-PAGE Tris-HCl gel for electrophoresis. Gels were silver-stained and photographed.

Mice and Induction of Lymphatic Proliferation Lesions

Ndst-1 mutants bearing genotype Ndst1f/fTekCre+ were generated by crossing Ndst-1 conditional mutants (Ndst-1f/f) with mice expressing Cre under control of the Tek promoter as published previously (20). Mutants were extensively backcrossed onto C57Bl/6. For some studies, LEC from oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions were isolated as published previously (17). Mice were housed in AAALAC-approved vivaria following institutional IACUC standards, maintained on a 12-h light-dark cycle, weaned at 3–4 weeks age, and fed water/standard chow ad libitum.

PCR Analysis of Ndst1 Inactivation in Lymphatic Endothelia Isolated from Mutant Mice

Quantitative PCR on genomic DNA was performed using primers flanking the downstream loxP recombination site of the Ndst1 floxed construct, as published previously (11), using lymphatic endothelia harvested from oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions (n = 3 mice per group). To determine deletion efficiency in lymphatic endothelia isolated from Ndst1f/fTekCre+ mutants, cycle threshold (Ct) values from duplicate assays were used to determine the quantity of loxP DNA amplified from Cre+ mutant versus Cre− floxed-control genomic DNA samples. Ct values from triplicate assays were used to calculate fold expression relative to GAPDH expression in the same sample. This analysis showed that LEC isolated from Ndst1f/fTekCre+ mutant mice underwent ∼75% deletion of the loxP-flanked allele of Ndst1.

Post-transcriptional Silencing of Heparan Sulfate Biosynthetic Enzymes

Near confluent primary human LEC were transfected with 20 nm siRNA targeting either xylosyltransferase-2 (siXylT2) or the heparan sulfate N-sulfating enzyme Ndst1 (siNdst1). Transfection of duplex-scrambled RNA (siDS) was used as a control. Transfections were carried out using Trifectin (IDT Technologies) following the manufacturer's recommendations. For some studies, VEGFR-3 siRNA was used as an additional control. PBS-rinsed cells were exposed to transfection complex in Opti-MEM (Invitrogen) for 6 h. Cells were then allowed to recover overnight in normal fully supplemented growth medium prior to assays.

Cell Viability Assays

Primary human LEC were seeded onto 96-well plates and serum-starved overnight. Cells were then treated with EBM-2 medium containing 2% FBS with or without 300 ng/ml VEGF-C (R&D Systems) for 24 h. At base line and at 24 h, cell viability for each well (proportional to the viable cell mass) was measured using the CellTiter-Blue assay (Promega) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Relative responses were determined by measuring the absorbance at A570 corrected to the value for a reagent-only blank well. Measurements for each condition were carried out in quadruplicate.

Proximity Ligation Assays

Primary human LEC, following transfection with control (duplex-scrambled RNA) versus XylT2 siRNA, were cytospun onto slides, air-dried, and cooled to 4 °C. Recombinant human VEGF-C was added to the slides (1 μg/ml) in PBS and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Slides were rinsed with PBS, fixed for 10 min in ice-cold methanol, and washed in ultrapure water. Some slides were not exposed to exogenous VEGF-C (to detect endogenous ligand). Slides were blocked 1 h in 1% BSA/TTBS (0.1% Tween 20/Tris-buffered saline) at room temperature. Anti-human VEGF-C and VEGFR-3 antibodies (1:100) were added to the slides in 1% BSA/TTBS and incubated in a humidified slide chamber overnight at 4 °C. For proximity ligation assay (PLA; Olink), anti-mouse (−) and anti-rabbit (+) probes were then applied, and labeling was completed following the manufacturer's instructions. Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) fluorescence-mounted slides (DAPI nuclear stain) were imaged and photographed (Nikon Eclipse-80i microscope; 40× objective) at room temperature. Mean field signal intensities (n = 5/sample; pixel intensities indexed to cell number) were determined using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health).

Compositional Analysis of Lymphatic Heparan Sulfate

Purification of heparan sulfate from cultured LEC was carried out as described previously (18) and subjected to enzymatic depolymerization with 2 milliunits each of heparin lyases I–III (IBEX) overnight at 37 °C in 50 μl of digest buffer (40 mm ammonium acetate and 3.3 mm calcium acetate, pH 7). Heparan sulfate disaccharide analysis was carried out by quantitative liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry (21). Briefly, samples were dried down, and [12C6]aniline (15 μl, 165 μmol) and 15 μl of 1 m NaCNBH3 (Sigma) freshly prepared in dimethyl sulfoxide/acetic acid (7:3, v/v) were added to each sample. Aniline labeling of disaccharide reducing ends was carried out at 37 °C for 16 h, and products were dried down. Derivatized disaccharide residues were separated on a C18 reversed phase column (0.21 × 15 cm; Thermo-Scientific) with ion pairing agent (dibutylamine, Sigma) (22). Eluted ions of interest were monitored in negative ion mode on an LTQ Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo-Finnigan). Capillary temperature and spray voltage were kept at 150 °C and 4.0 kV, respectively. Accumulative extracted ion current was computed, and data were analyzed using Qual Browser software (Thermo-Finnigan). Quantitative compositional analysis of heparan sulfate disaccharides was carried out by comparing with known amounts of corresponding standards differentially labeled with [13C6]aniline, which were added to each sample prior to LC/MS.

Lymphatic Sprouting in Collagen

LEC were mixed into type I collagen (3 mg/ml; Pur-Col) on ice, plated (96-well format) at a concentration of 20,000 cells/50 μl of liquid collagen/well, and allowed to solidify (5% CO2 37 °C humidified incubator). DMEM containing 5% FBS with either FGF-2 (30 ng/ml) or recombinant mouse VEGF-C (100 ng/ml) was used to cover wells containing collagen-embedded LEC. Sprouting was quantified at 72 h by measuring net endothelial process lengths/well (in triplicate) using a phase-contrast inverted microscope (Olympus; 5× objective) and eyepiece graticule. Responses were normalized to basal (no growth factor) response.

SDS-PAGE and Western Blotting

Human LEC were seeded at equal density and grown to near confluence. After incubation in serum-free DMEM ± heparinase (heparin lyases I–III; 2.5 IU/ml) for 4.5 h and washing, cells were exposed to recombinant human VEGF-C (100 ng/ml), FGF-2 (10 ng/ml), or EGF (100 ng/ml) for 15 min. In separate experiments examining the effects of heparinoids, stimulation was carried out in the presence/absence of either unmodified commercial heparin or N-desulfated, 2-O-desulfated, or 6-O-desulfated heparins at the indicated concentrations. Media were removed, and samples were collected in lysis buffer (containing 50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 0.15 m NaCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm CaCl2, 1 mm EDTA, 1 μl/ml protease inhibitors (Sigma), 1 mm PMSF, 0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 1% sodium deoxycholate, and 1 mm sodium orthovanadate), followed by freezing at −80 °C. Thawed samples were separated by electrophoresis in 4–15% gradient gels and electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes probed with antibodies to phospho-Erk1/2 (p44/42). Bound antibody was detected using peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit antibody (Bio-Rad) and SuperSignal chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce) for HRP detection. Separate Western blots were carried out using polyclonal antibodies against total Erk1/2. In some studies, the phospho-Erk1/2 response to VEGF-C was examined in serum-starved siXylT2- or siNdst1-transfected cells versus control-transfected (scrambled-duplex RNA) cells. Bands were quantified on a densitometer (Bio-Rad GS800).

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting

Primary human lung LEC were grown to 80–90% confluence, washed with PBS, and serum-starved for 4.5 h using DMEM ± 2.5 milliunits/ml heparinase (heparin lyases I–III). After washing, cells were treated for 10 min with 100 ng/ml recombinant human VEGF-C. In separate studies examining the effect of heparin, stimulation was carried out in the presence of unmodified heparin (at 10 μg/ml, a dose that was sufficient to inhibit Erk1/2 phosphorylation). Cells were then lysed with 1× Cell Lysis Buffer (Cell Signaling) supplemented with protease inhibitor mixture (Sigma), phosphatase inhibitors (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and PMSF. Cleared lysates were added to Protein-G (Invitrogen) magnetic beads labeled with antibody against human VEGFR-3. The mixture was incubated overnight on a rotor wheel at 4 °C. Protein-bead complexes were washed three times, and Laemmli sample buffer was added. Samples were boiled for 5 min with bead removal from lysates, followed by cooling on ice for 5 min. Proteins were separated on a 7.5% Tris-HCl gel (Bio-Rad), transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, and incubated overnight with mouse anti-human PY-20 (1:1000) to detect phosphorylated VEGFR-3. Biotin anti-mouse (1:1000) and streptavidin-HRP 1:10,000 (Jackson ImmunoResearch) were used to detect PY-20-labeled protein. Total VEGFR-3 in original lysates was determined by Western blotting.

Scratch Assays

Primary LEC targeted with either siXylT2 or siNdst1 (or siDS as a control) were grown to confluence in 24-well plates. Following starvation in serum-free EBM-2 medium (Lonza) for 5 h, cell monolayers were scratched across the full well diameter (p200 pipette tip). Unsupplemented EBM-2 medium containing 2% FBS ± VEGF-C (300 ng/ml; R&D Systems) was then added followed by incubation for 48 h in standard culture. For some assays, 0.5 μg/ml mitomycin-C (Sigma) was added to the media during the 48-h period. Scratch images were taken at 0, 24, and 48 h (Nikon Eclipse 80i microscope; 4× objective), with quantification carried out using ImageJ software. Percent filling of scratch zones for each well was determined at 24 and 48 h (calculated by dividing scratch area occupied by cells by the total scratch area at time 0). The assay was also carried out for stimulation by FGF-2 (300 ng/ml). Assays were carried out in triplicate.

Cell Cycle Analysis

Culture-harvested siRNA-targeted LEC were serum-starved overnight, followed by treatment with EBM-2 medium containing 2% FBS ± VEGF-C (300 ng/ml; R&D Systems) for 24 h. Cells were then fixed in 70% ethanol at −20 °C for 2 h, washed with PBS, and stained with propidium iodide solution (0.1% Triton X-100, 0.2 mg/ml RNase A, and 20 μg/ml propidium iodide in PBS). Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry to measure cell DNA content, with G1, S, and G2 cytometry data fit to the Watson Pragmatic mathematical model (23) using FlowJo (Tree Star, Inc.) software.

Statistics

Mean values (normalized densitometry signal intensities, % gap-filling in scratch assays, or normalized sprouting responses) were compared using Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

VEGF-C Binds to Heparan Sulfate Isolated from Lymphatic Endothelium

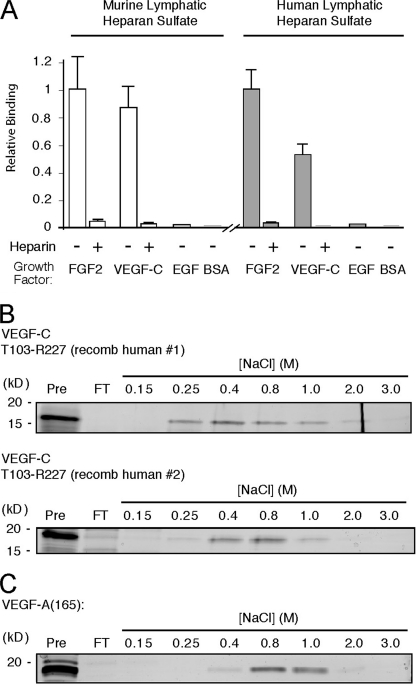

Primary LEC were isolated from experimental oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions in mice following the method of Mancardi et al. (17). Cells expressed the major heparan sulfate chain-polymerizing enzymes as well as two of the four Ndst-sulfating enzymes expressed in mammals (supplemental Fig. S1 and Table 1) (24). To purify lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate, cultured LEC were radiolabeled with Na2[35S]O4, and the [35S]glycosaminoglycan fraction was isolated. Depolymerization of the chains with heparin lyases and chondroitinase ABC showed that the cells made ∼67% heparan sulfate and ∼33% chondroitin sulfate. Recombinant mouse VEGF-C bound to purified [35S]heparan sulfate (Fig. 1A) as measured by a nitrocellulose filter binding assay (19). The extent of binding was comparable with that of FGF-2 (as a control), with binding abrogated by addition of nonradiolabeled heparin. Binding to epidermal growth factor (EGF), a non-heparin binding growth factor, or to BSA was negligible. Comparable results were obtained using recombinant human VEGF-C and [35S]heparan sulfate isolated from human primary LEC (Fig. 1A, right panel). Binding for each factor, quantified as membrane-bound cpm/μg of protein, was normalized to that of FGF-2. (As a reference, for 10,000 cpm of human lymphatic [35S]heparan sulfate incubated with 0.5 μg of FGF-2, membrane-bound radioactivity was 5420 ± 780 cpm, the average of four experiments.) Binding of the same preparation of recombinant VEGF-C to commercial heparin was carried out by heparin-Sepharose affinity chromatography. The protein bound to the resin, and eluted between 0.4 and 0.8 m NaCl (Fig. 1B, top panel). This was similar to the NaCl concentration required for elution of a recombinant preparation of the same protein from a distinct manufacturer (Fig. 1B, bottom panel) and somewhat below the concentration required for elution of VEGF165 (0.8–1.0 m), a known heparin-binding VEGF-A splice variant (Fig. 1C). The majority of FGF-2 (run as a control) was captured in the 2 m NaCl elution fraction (data not shown), consistent with previous findings (25).

FIGURE 1.

VEGF-C binds to lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate. A, oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions were induced in wild type mice, and cultured lymphatic endothelial cells from lesions were radiolabeled with 35SO4. [35S]Heparan sulfate from the cells was purified and incubated with recombinant mouse VEGF-C (mature, fully processed 125-amino acid sequence, described under “Experimental Procedures”), followed by passage over nitrocellulose membrane filters. Membrane-bound complexes of [35S]heparan sulfate and protein collected on the filters were quantified and plotted relative to that of FGF-2 (open bars, left). Binding was also tested in the presence of heparin as a competitor. Controls included binding to EGF and BSA. The same experiment was carried out using recombinant human VEGF-C (mature, fully processed 125-amino acid sequence, described under “Experimental Procedures”) and [35S]heparan sulfate from primary human lung lymphatic endothelial cells (filled bars, right; p = 0.01 for FGF-2 versus VEGF-C; average of four experiments). B, to assess binding of the same recombinant human VEGF-C protein (designated recomb human #1) to commercial heparin, affinity chromatography using heparin-Sepharose columns was carried out. Fractions collected over the indicated NaCl step concentration range were run on SDS-PAGE with silver staining to reveal the protein elution profile. The level to which native protein migrates on the gel is shown at left (Pre column sample in 1st lane with kDa range as indicated); column flow-through (FT) is shown in 2nd lane; and elution profile (subsequent lanes) is shown to the right. For comparison, heparin affinity chromatography was carried out for another commercial recombinant human VEGF-C preparation (mature, fully processed 125-amino acid sequence, recomb human #2, shown below). C, binding of recombinant human VEGF-A (VEGF165) was also examined.

Interestingly, in separate binding studies, [35S]heparan sulfate purified from primary human (dermal) vascular endothelial cells was also able to bind VEGF-C; however, the degree of binding was significantly lower than that supported by [35S]heparan sulfate purified from primary human lymphatic endothelia (36% versus 53%, normalized to the binding of FGF-2 (p = 0.02, mean of four experiments; data not shown)). As a reference, binding of FGF-2 to human LEC [35S]heparan sulfate (4520 ± 650 cpm/μg protein) was comparable with the binding of FGF-2 to human (dermal) vascular endothelial cells [35S]heparan sulfate (4560 ± 1030 cpm/μg protein). Lymphatic endothelium may thus biosynthesize heparan sulfate that binds to VEGF-C to a greater degree than that from nonlymphatic (i.e. vascular) endothelium.

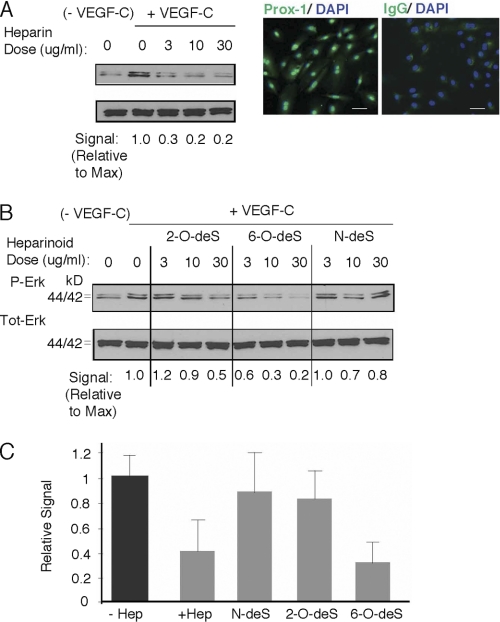

Heparin and Specific Sulfate-modified Heparinoids Interfere with Erk1/2 Activation in Response to VEGF-C

Stimulation of serum-starved primary human lung LEC with VEGF-C resulted in phosphorylation of Erk1/2, whereas stimulation in the presence of commercial heparin (as a potential soluble competitor) resulted in dose-dependent inhibition (Fig. 2A). Interestingly, degree of inhibition was sensitive to modifying the sulfation state of the competing heparin species. Removal of N-sulfate groups from glucosamine residues or 2-O-sulfate groups on iduronic acid residues reduced potency of inhibition, whereas 6-O-desulfation did not, and quantification of responses showed that heparin and 6-O-desulfated heparin had similar inhibitory potency (Fig. 2, B and C). These findings support the hypothesis that VEGF-C may interact with heparan sulfate on lymphatic endothelial cells and that the interaction depends on N- and 2-O-sulfate groups on heparan sulfate chains, rather than 6-O-sulfate groups.

FIGURE 2.

VEGF-C-mediated Erk1/2 activation in lymphatic endothelium is inhibited by the presence of heparin, with unique responses in the presence of sulfate-modified heparinoids. A, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (p44/42) in serum-starved human primary lung lymphatic endothelial cells in response to treatment with recombinant human VEGF-C was measured in the absence/presence of increasing commercial heparin concentration. Lymphatic endothelial cell purity was confirmed by immunostaining to detect nuclear expression of Prox-1 (right photomicrographs; with IgG isotype-matched control antibody stain to right; bar, 50 μm). Maximum phosphorylation was noted in the absence of heparin (+VEGF-C, heparin = 0). Phospho/total signal intensities were quantified by densitometry and normalized relative to that of maximum stimulation (Signal Relative to Max, below panel). Preliminary testing showed that marked inhibition was achieved at heparin doses >1 μg/ml. B, effects of N-desulfated (N-deS), 2-O-desulfated (2-O-deS), or 6-O-desulfated (6-O-deS) heparin species were examined at the same doses as that used for unmodified commercial heparin in A. C, quantitative assessment for responses in the presence of heparin versus sulfate-modified heparinoids dosed at 10 μg/ml is shown (graph). Values represent the densitometry ratio of phospho/total Erk for VEGF-C-mediated stimulation in the presence of either heparin (+ Hep) or each of the respective heparinoids normalized to the signal for stimulation in the absence of heparin (− Hep). Graph shows mean of four experiments. *, p < 0.001 for + heparin versus − heparin; **, p < 0.001 for 6-O-deS versus − heparin; differences in means for N-deS versus − heparin or 2-O-deS versus − heparin were not significant).

Heparinase-mediated Ablation of Lymphatic Endothelial Heparan Sulfate Results in Altered Growth Signaling and Reduced Receptor Phosphorylation in Response to VEGF-C

Stimulation of serum-starved primary human lung LEC with VEGF-C resulted in phosphorylation of Erk1/2, although pretreatment of cells with heparinase, which destroys cell-surface heparan sulfate, abrogated VEGF-C signaling (Fig. 3A; compare − versus + Heparinase) and diminished the response to FGF-2 (Fig. 3B, left panels). However, heparinase did not reduce Erk1/2 phosphorylation mediated by EGF, a non-heparin-binding growth factor (Fig. 3B, right panels). Phosphorylation of Akt in response to VEGF-C and FGF-2 was also reduced following treatment of LEC with heparinase (data not shown). To investigate any effect of ablating cell-surface heparan sulfate on VEGF-C-mediated receptor activation, VEGFR-3 phosphorylation in response to VEGF-C stimulation was examined in the absence/presence of primary LEC pretreatment with heparinase. Stimulation of heparinase-treated cells resulted in reduced VEGFR-3 phosphorylation (Fig. 3C). Receptor phosphorylation was also reduced by VEGF-C stimulation in the presence of commercial heparin (supplemental Fig. S2).

FIGURE 3.

Heparinase-mediated ablation of lymphatic endothelial cell-surface heparan sulfate inhibits growth signaling and receptor activation in response to VEGF-C. A, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 (p44/42) in serum-starved primary human lung lymphatic endothelial cells was measured before/after growth factor stimulation. Responses to stimulation with recombinant human VEGF-C were measured for cells pretreated with or without heparinase (used to destroy cell-surface heparan sulfate). Total Erk for each panel is shown below respective phospho-Erk panels. Ratios of phospho/total Erk band intensities for each condition were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the respective base-line phospho/total Erk ratio (shown in parentheses below each panel). B, responses to stimulation by FGF-2 (left panels) as well as the non-heparin-binding factor EGF (right panels) pretreated with or without heparinase were also examined. C, VEGFR-3 receptor phosphorylation in response to VEGF-C was examined in the absence/presence of heparan sulfate elimination by heparinase. Receptor was immunoprecipitated from lysates of either serum-starved LEC (baseline) or the same cells preincubated in the absence/presence of heparinase and stimulated with VEGF-C. Immunoblotting with anti-phosphotyrosine was carried out and revealed a phosphorylated product in response to stimulation with VEGF-C (WB: P-Tyr; middle lane), consistent with phosphorylated VEGFR-3. The response of heparinase-treated cells is shown in the right lane. Total receptor in the original lysates (TL) is shown below (WB: VEGFR-3). Graph (right) shows mean signal intensities normalized to base-line signal for n = 3 experiments (±S.E.). *, p = 0.001 for difference relative to normalized base-line signal; **, p = 0.009 for difference between mean heparanase and mean VEGF-C values.

Disruption of Lymphatic Endothelial Heparan Sulfate Chain Biosynthesis Results in Altered Erk1/2 Phosphorylation and Reduced VEGFR-3-dependent Binding of VEGF-C

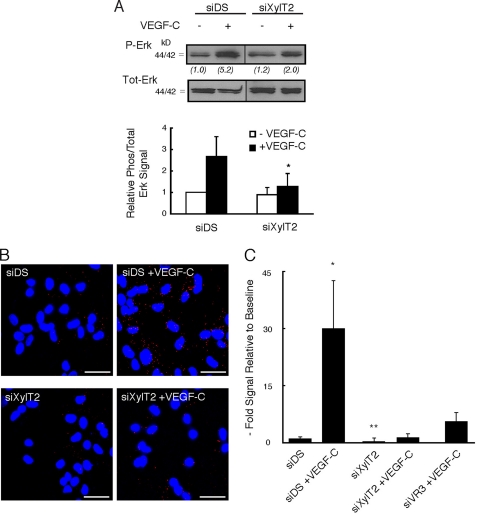

Heparan sulfate biosynthesis was targeted at the site of glycan initiation (attachment to core proteins via xylose) through siRNA-mediated silencing. Human primary LEC were transfected with siRNA targeting xylosyltransferase-2 (siXylT2), the major XylT isoenzyme expressed by human LEC (quantitative RT-PCR; data not shown). Control LEC were transfected with scrambled duplex RNA (siDS). Initial studies examining growth signaling revealed that VEGF-C-mediated Erk1/2 phosphorylation was blunted in siXylT2-targeted LEC as compared with controls (Fig. 4A). We then examined the upstream effect of such targeting on VEGFR-3 activation in response to VEGF-C stimulation. Using a novel PLA, the specific association of VEGF-C with VEGFR-3 receptor on siXylT2-targeted LEC was examined through dual labeling with ligand and receptor antibodies followed by application of secondary bi-functional PLA probes that yield a fluorescent signal in the assay only when ligand and receptor (the antibody targets) interact (26). Detection of abundant ligand/receptor proximity products was noted upon addition of exogenous VEGF-C to control LEC, whereas siXylT2-targeted LEC demonstrated a marked reduction in ligand-receptor complex formation (Fig. 4, B and C), indicating the importance of LEC cell-surface heparan sulfate in mediating association of receptor-ligand complexes. As a control, the assay was also sensitive to silencing VEGFR-3 (Fig. 4C, right panel), resulting in a marked reduction in complexes in siVEGFR-3-targeted cells relative to siDS controls (77% reduction; p = 0.004).

FIGURE 4.

Silencing of lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate chain biosynthesis inhibits VEGF-C-dependent Erk1/2 activation and reduces receptor-dependent binding of VEGF-C. A, cultured primary human lymphatic endothelia were transfected with siRNA targeting XylT2 (siXylT2) or with scrambled duplex RNA (siDS) as a control. Under each condition, phosphorylation of Erk1/2 in serum-starved cells before/after recombinant human VEGF-C exposure was examined by Western blotting. Total Erk for each condition is shown below respective phospho-Erk lanes. Ratios of phospho/total Erk band intensities for each condition were quantified and normalized to the respective base-line ratio (values in parentheses). Graph (below) shows mean signal intensities for n = 4 experiments (±S.E.). B, in separate experiments, exposure of mock-transfected (siDS) control cells to exogenous recombinant human VEGF-C followed by washing resulted in the engagement of numerous cell-surface VEGF-C-VEGFR-3 complexes (red dots, top right photomicrograph; siDS +VEGF-C), as measured through PLA. There was minimal endogenous signal at base line, prior to exogenous VEGF-C application (top left; siDS). Exposure of siXylT2-targeted cells to exogenous VEGF-C resulted in minimal complex formation over base line (bottom photomicrographs; bar, 50 μm). C, quantified results, showing the fold increase in fluorescent signal for each condition indexed to base-line signal for siDS control. Also shown on the graph (right) is the mean signal achieved by cells treated with siRNA targeting VEGFR-3 and exposed to exogenous VEGF-C (labeled siVR3+VEGF-C). *, p values for difference between siDS + VEGF-C and the following: siDS base line (p < 0.001); siXylT2 + VEGF-C (p = 0.001); siVR3 + VEGF-C (p = 0.004). **, p = 0.04 for difference in base-line signals (siDS versus siXylT2).

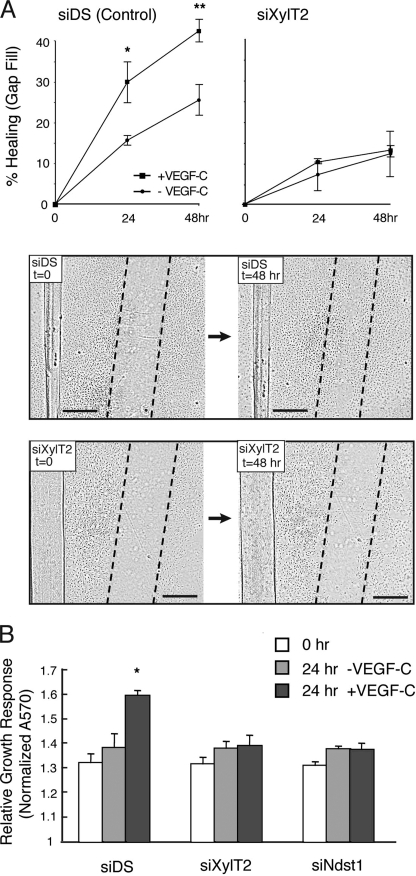

We turned to a functional assay to assess the effects of XylT2 targeting on VEGF-C-mediated cell growth across a gap in a culture plate. Targeted LEC were tested in a scratch assay (Fig. 5A), where cellular closure of a “scratch”-induced gap created across confluent control (siDS) LEC was efficiently achieved over 24–48 h by addition of VEGF-C, and absence of VEGF-C slowed gap filling by control LEC. However, siXylT2-targeted LEC were unresponsive to VEGF-C and showed a marked reduction in gap-filling capacity (Fig. 5A, lower panels). Cell growth studies using a viability assay (Fig. 5B) revealed that VEGF-C-dependent growth of the cells was sensitive to siXylT2 targeting. Growth inhibition persisted when siNdst1-targeted cells were used, indicating that the cells are also sensitive to inhibiting the sulfation of nascent heparan sulfate chains.

FIGURE 5.

Targeting lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate chain biosynthesis abrogates VEGF-C-dependent gap filling and growth responses in cultured cell systems. Monolayers of serum-starved human lymphatic endothelia transfected with siRNA targeting XylT2 (siXylT2) or with scrambled duplex RNA (siDS; control) were scratched to create a gap in the center at time 0. The ability of cells to fill the gap in response to VEGF-C was examined. A, graphs show quantitative data for percentage of gap filling over time in the presence/absence of VEGF-C by control cells (left panel) and by siXylT2-targeted cells (right panel). Photomicrographs below show gap (with dotted gap boundaries) within confluent cell layers at time 0, and degree of gap filling at 48 h in the presence of VEGF-C (bar, 0.5 mm). *, p = 0.009 and **, p = 0.003 for difference in mean responses by VEGF-C-stimulated versus un-stimulated control (siDS) cells at 24 h and 48 h, respectively. (Graph, mean of n = 3 trials.). B, cell viability assays demonstrate growth responses of control (siDS), siXylT2-, and siNdst1-targeted lymphatic endothelia in response to 24 h of exposure to VEGF-C. *, p < 0.001 for the difference in mean growth responses by control (siDS) cells stimulated ± VEGF-C for 24 h. Other differences were not significant.

Biosynthesis of Appropriately Sulfated Heparan Sulfate Is Required for VEGF-C as Well as FGF-2-dependent Growth and Sprouting Responses by Lymphatic Endothelial Cells

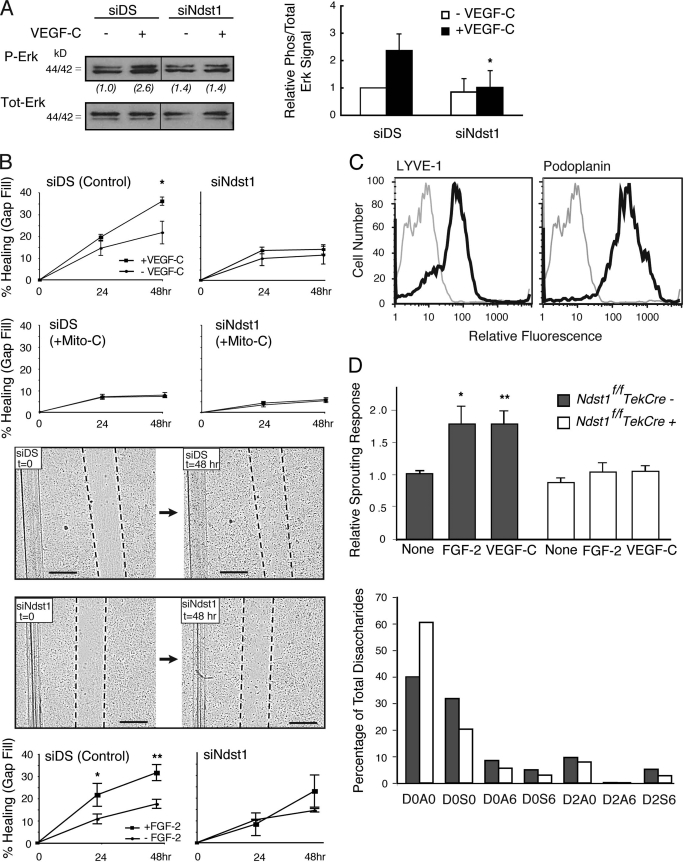

Following the functional effect of silencing heparan sulfate chain biosynthesis on LEC growth responses to VEGF-C (Fig. 5), we targeted chain sulfation. Primary human lung LEC were treated with siRNA targeting N-deacetylase/N-sulfotransferase-1 (Ndst1), a key sulfate-modifying enzyme involved in heparan sulfate biosynthesis. Initial growth signaling studies revealed that VEGF-C-mediated Erk1/2 phosphorylation was blunted in siNdst1-targeted LEC as compared with controls (Fig. 6A). Deficiency in the enzyme also resulted in abrogating cell growth responses (Fig. 5B) as well as cell cycle proliferation responses (supplemental Fig. S3) to VEGF-C. In addition, filling of a scratch/gap in a monolayer of control (siDS) LEC was efficiently achieved by addition of VEGF-C, whereas siNdst1-targeted LEC showed a marked reduction in the gap-filling response (Fig. 6B, top panel). The assay was sensitive to mitomycin-C, which blocks cell proliferation (see graphs labeled +Mito-C in Fig. 6B), indicating that gap filling in the original assay was dependent on VEGF-C-mediated proliferation (rather than migration), and was inhibited by Ndst1 deficiency. In other scratch assays, siNdst1-targeted primary human LEC also demonstrated a blunted response to FGF-2 (Fig. 6B, bottom panel).

FIGURE 6.

Targeting lymphatic endothelial Ndst1 results in reduced growth and sprouting responses to VEGF-C and FGF-2. A, serum-starved human lymphatic endothelia were transfected with siRNA targeting Ndst1 (siNdst1) or with scrambled duplex RNA (siDS; control). Phosphorylation of Erk1/2 before/after VEGF-C exposure was examined by Western blotting. Total Erk for each condition is shown. Ratios of phospho/total Erk band intensities for each condition were quantified and normalized to the respective base-line ratio (values in parentheses). Graph (right) shows mean signal intensities for n = 4 experiments (±S.E.). B, ability of the siRNA-targeted lymphatic endothelia to fill a gap made between cells in a scratch assay was examined over 48 h in the presence/absence of growth factor. Photomicrographs show gap (with dotted gap boundaries) within confluent cell layers at time 0, and at 48 h in the presence of VEGF-C (bar, 0.5 mm). Control siDS cells partially filled the gap over 48 h (upper photomicrographs), whereas response by siNdst1-targeted cells is shown below. Mean values for responses in the presence/absence of VEGF-C were graphed (top). *, p = 0.01 for VEGF-C versus un-stimulated cells at 48 h. Graphs for assays carried out in the presence of the cell proliferation inhibitor mitomycin-C are also shown (labeled +Mito-C). The scratch assay was also carried out for cell stimulation in the presence/absence of FGF-2 (graphs shown below photomicrographs). *, p = 0.008 for FGF-2 versus unstimulated cells at 24 h; **, p < 0.001 for FGF-2 versus unstimulated cells at 48 h. (Graphs, mean of n = 3 trials.) C, lymphatic endothelia were isolated from oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions generated in Ndst1f/fTekCre(+) mutant mice and Cre(−) littermates, with podoplanin and LYVE-1 expression shown by FACS. D, sprouting responses in collagen upon stimulation with recombinant VEGF-C or FGF-2 were examined. Significant responses to growth factor were noted for Cre(−) wild type cells (*, p = 0.003, and **, p = 0.008 for respective VEGF-C and FGF-2 responses versus base-line responses in the absence of growth factor, None). Mutant responses (right) were not significantly different from base line. Sulfation of heparan sulfate disaccharides purified from mutant versus wild type cells was determined by liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry and quantified as a percentage of total disaccharides (bottom graph). The detected disaccharide species are listed (x axis) according to published nomenclature (21), with D0A0 (left-most bars) indicating the percentages of unsulfated disaccharides.

To examine another characteristic growth factor response by Ndst1-targeted lymphatic endothelia, we focused on sprouting responses by proliferating LEC isolated from experimental oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions in mice (17). LEC directly isolated from these lesions expressed LYVE-1 and podoplanin (Fig. 6C). To achieve a genetic alteration in lymphatic endothelial Ndst1, lesions were generated in Ndst1f/fTekCre+ mutant mice, which bear a pan-endothelial conditional mutation in Ndst1. The Tek promoter drives pan-endothelial expression of Cre recombinase, as described previously (20, 27). Analysis of the isolated LEC by quantitative genomic PCR showed that mutant LEC underwent ∼75% deletion of the loxP-flanked allele of Ndst1, consistent with the known expression of Tek during lymphatic proliferation in vivo (28, 29). Sprouting of mutant LEC in response to VEGF-C or FGF-2 in type I collagen was significantly diminished (Fig. 6D), indicating that the sulfate composition of lymphatic heparan sulfate affects matrix-associated sprouting by the LEC. To examine whether the observed phenotype correlated with reduced sulfation of lymphatic heparan sulfate produced by the LEC, analysis of heparan sulfate disaccharides derived from the LEC was carried out using quantitative tandem liquid chromatography/mass spectrometry. N-Sulfation of mutant disaccharides was reduced by ∼35%, with an increase in unsulfated disaccharides (52%) and modest reductions in 6-O- and 2-O-sulfation (Fig. 6D, lower graph; see also supplemental Fig. S4). More dramatic reduction in sulfation did not occur due to incomplete Ndst1 inactivation and the fact that lymphatic endothelia also express a second isoenzyme (Ndst2). Similar results have been observed when Ndst1 was genetically targeted in blood endothelial cells (11, 20). These findings suggest that appropriately sulfated lymphatic heparan sulfate is required for the growth and sprouting of VEGF-C-stimulated lymphatic endothelial cells.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we found that lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate is critically required for the following: 1) activation of Erk1/2 growth signaling as well as VEGFR-3 receptor-dependent binding of VEGF-C, and 2) lymphatic endothelial cell growth and sprouting in response to VEGF-C. In addition, targeting lymphatic endothelial Ndst1, which plays a key role in generating clustered sulfate-modified domains on nascent heparan sulfate chains, is sufficient to disrupt lymphatic growth (including proliferation) as well as sprouting in response to VEGF-C. Although altering lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate also results in impaired lymphatic growth responses to FGF-2, a known heparin-binding pro-lymphangiogenic growth factor, our findings demonstrate a distinct requirement for the presence and appropriate sulfation of the glycan chain on the cell surface to elicit characteristic VEGF-C-mediated responses.

Experiments focusing on the interaction of VEGF-C with cultured lymphatic endothelia revealed an important role for lymphatic heparan sulfate in mediating ligand binding to the cell surface. It is possible that heparan sulfate presented on lymphatic cell-surface proteoglycans may directly bind VEGF-C (Fig. 1) and cluster it in a manner that facilitates receptor interaction. Moreover, using a proximity ligation assay, it appears that biosynthesis of the glycan is critically required for the specific association of VEGF-C with its cognate receptor VEGFR-3 (Fig. 4, B and C). Activation of the latter is known to be required for lymphatic endothelial Erk1/2 and Akt-mediated signaling responses to VEGF-C (4, 5). Destroying lymphatic cell-surface heparan sulfate (via heparinase) or competing with heparin during stimulation with VEGF-C inhibited not only the activation of major mitogen growth signaling intermediates (i.e. Erk1/2) but also upstream ligand-dependent phosphorylation of VEGFR-3 (Fig. 3).

How might HS modulate the initiation of receptor-dependent signaling by VEGF-C? One possibility is that the interaction of VEGF-C with VEGFR-3 may be similar to the interaction of certain VEGF isoforms with VEGFR-2 or FGF-2 with FGF receptor during ternary complex formation, wherein heparan sulfate binds both ligand and receptor (11, 30, 31). More generally, lymphatic heparan sulfate may serve to maintain the presence of VEGF-C in proximity with VEGFR-3. It should be mentioned that despite a nearly complete abrogation of VEGF-C-VEFGR3 interaction as a result of siXylT2 targeting (Fig. 4, B and C), a very minimal receptor response by the HS-altered cells may still translate into a modest downstream Erk signal in response to the VEGF-C ligand (Fig. 4A, right side of blot). It is also possible that other non-VEGFR3 activation signals may contribute to Erk phosphorylation in this setting. Moreover, in the siXylT2-targeted state, there may also be partial contribution to HS biosynthesis from any XylT1 expression (see supplemental Fig. S1, for example). Nevertheless, the overall effect of siXylT2 targeting on Erk signaling correlates with the marked inhibition noted in VEGF-C-VEGFR3 association, and the effect is significant (Fig. 4). Intriguingly, it also appears that the functional interaction of VEGF-C with the lymphatic cell surface (and downstream Erk activation) is selective with respect to the sulfation pattern of the heparan sulfate chains (Fig. 2). Although further work is needed to define specific heparan sulfate-binding sites in VEGF-C and VEGFR-3, the findings herein suggest an important co-receptor role for heparan sulfate in facilitating the actions of major lymphatic growth factors on lymphatic endothelium.

We isolated mutant versus wild type LEC from experimental oil granuloma lymphatic proliferative lesions induced in Ndst1f/fTekCre+ mutant mice. Primary LEC isolated ex vivo from lesions in mutant mice demonstrated reduced sprouting responses to VEGF-C as well as FGF-2 (Fig. 6D, upper panel). Driving Cre-mediated Ndst1 inactivation under control of the Tek promoter generates a pan-endothelial reduction in Ndst1 expression. This was sufficient to alter Ndst1 expression in lymphatic endothelia isolated from Ndst1f/fTekCre+ mutants, consistent with studies reporting the expression of Tek in developing lymphatic endothelium (28, 29). In addition, heparan sulfate purified from mutant cells showed reductions in glycan sulfate composition consistent with deficiency in the Ndst1-sulfating enzyme (Fig. 6D, bottom panel). Lymphatic proliferation in vivo might be affected not only by VEGF-C and/or FGF-2 but also by partial contributions from other heparan sulfate-dependent growth factors, such as PDGF or heparin-binding splice variants of VEGF-A. The latter has been shown to function in concert with VEGF-C to induce early lymphatic sprouting in embryoid body models (32). It was beyond the scope of our studies to measure the relative degrees to which alterations in heparan sulfate biosynthesis affect the various factors that may be involved. Indeed, this may vary among lymphatic endothelia isolated from different tissues. Rather, the experiments herein, employing heparinoid competition, heparinase-mediated ablation, and siRNA as well as genetic loss-of-function strategies to alter lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate, provide evidence for the cell autonomous importance of the glycan during lymphatic endothelial responses to VEGF-C, a dominant pro-lymphangiogenic factor. Lymphatic heparan sulfate may function in a similar manner during responses to FGF-2, a known lymphatic growth factor (8) with well recognized heparan sulfate binding properties. Although this has not yet been examined for responses of lymphatic endothelium to FGF-2, the unique and critical role of the glycan, including its specific sulfation, in lymphatic endothelial VEGF-C binding and signaling point to what may be a novel co-receptor function for heparan sulfate in VEGFR-3 activation by VEGF-C.

It should also be noted that the effects of heparan sulfate targeting on VEGF-C-mediated lymphatic endothelial growth across a scratch-gap in culture (as in Fig. 6B, top graphs) were abolished by carrying out the assays in the presence of mitomycin-C (Fig. 6B, +Mito-C graphs), which inhibits cell proliferation. It thus appears that the major effect of targeting heparan sulfate biosynthesis is on VEGF-C-dependent cell growth and proliferation. Accordingly, this was confirmed in assays directly examining cell growth (Fig. 5B) as well as cell cycle responses. Along those lines, we noted that siNdst1 targeting was sufficient to inhibit the cell cycle response of cultured primary LEC to VEGF-C stimulation (supplemental Fig. S3). This is consistent with the upstream effects on mitogen-mediated Erk1/2 activation. In addition, lymphatic endothelial sprouting responses were also sensitive to Ndst1 deficiency. This implies that mechanisms required for lymphangiogenesis may be uniquely sensitive to changes in lymphatic endothelial heparan sulfate.

A variety of different proteoglycan core proteins might serve to scaffold heparan sulfate chains on the lymphatic endothelial surface or even the pericellular matrix on secreted proteoglycans. For example, in primary mouse LEC isolated from oil granuloma/lymphangioma lesions (employed in Fig. 6, C and D), preliminary quantitative expression studies suggest that syndecan-4 appears to be the major proteoglycan core protein expressed on the LEC surface (data not shown). With this in mind, it is interesting to consider our finding of reduced growth factor-dependent sprouting by heparan sulfate-targeted LEC (Fig. 6), because syndecan-4 itself has been shown to play a critical role in mediating focal adhesions in studies employing syndecan-4 truncation constructs in cultured cells (33). Further studies are needed to identify the relative importance of this proteoglycan as a possible co-receptor for lymphangiogenesis signaling. Studies in proteoglycan gene-targeted mice are also underway to address these questions.

The findings herein may have importance with respect to therapeutic targeting. For example, interfering with heparan sulfate biosynthesis may reduce or prevent lymphatic progression during pathologic states of lymphangiogenesis, such as cancer, where the process may contribute to lymph node metastasis (1, 2). More generally, the findings may validate a rationale for up- or down-regulating heparan sulfate in the lymphatic microenvironment as a unique strategy to modulate VEGF-C-receptor engagement and activation in a variety of lymphatic pathologic states.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Nissi Varki, Lucie Kim, Laarni Gapuz, and Felix Karp (University of California San Diego Immunohistology Core) and Dr. Steffney Rought and the University of California San Diego Genomics Core. We thank Dr. J. Esko for valuable review and discussions.

This work was supported by the Veterans Affairs Career Development Program, American Cancer Society Grant RSG-08-153-01-CSM, and Uniting Against Lung Cancer Foundation (to M. M. F.). This work was also supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grant P01-HL57345-11 (to Dr. Jeffrey D. Esko).

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S4 and Table 1.

- LEC

- lymphatic endothelial cell

- siDS

- scrambled-duplex RNA

- PLA

- proximity ligation assay.

REFERENCES

- 1. Alitalo K., Tammela T., Petrova T. V. (2005) Nature 438, 946–953 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liersch R., Detmar M. (2007) Thromb. Haemost. 98, 304–310 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Veikkola T., Jussila L., Makinen T., Karpanen T., Jeltsch M., Petrova T. V., Kubo H., Thurston G., McDonald D. M., Achen M. G., Stacker S. A., Alitalo K. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 1223–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mäkinen T., Veikkola T., Mustjoki S., Karpanen T., Catimel B., Nice E. C., Wise L., Mercer A., Kowalski H., Kerjaschki D., Stacker S. A., Achen M. G., Alitalo K. (2001) EMBO J. 20, 4762–4773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wissmann C., Detmar M. (2006) Clin. Cancer Res. 12, 6865–6868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stacker S. A., Stenvers K., Caesar C., Vitali A., Domagala T., Nice E., Roufail S., Simpson R. J., Moritz R., Karpanen T., Alitalo K., Achen M. G. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 32127–32136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Joukov V., Sorsa T., Kumar V., Jeltsch M., Claesson-Welsh L., Cao Y., Saksela O., Kalkkinen N., Alitalo K. (1997) EMBO J. 16, 3898–3911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chang L. K., Garcia-Cardeña G., Farnebo F., Fannon M., Chen E. J., Butterfield C., Moses M. A., Mulligan R. C., Folkman J., Kaipainen A. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 11658–11663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nagy J. A., Vasile E., Feng D., Sundberg C., Brown L. F., Detmar M. J., Lawitts J. A., Benjamin L., Tan X., Manseau E. J., Dvorak A. M., Dvorak H. F. (2002) J. Exp. Med. 196, 1497–1506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shin W. S., Rockson S. G. (2008) Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1131, 50–74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Fuster M. M., Wang L., Castagnola J., Sikora L., Reddi K., Lee P. H., Radek K. A., Schuksz M., Bishop J. R., Gallo R. L., Sriramarao P., Esko J. D. (2007) J. Cell Biol. 177, 539–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Jakobsson L., Kreuger J., Holmborn K., Lundin L., Eriksson I., Kjellén L., Claesson-Welsh L. (2006) Dev. Cell 10, 625–634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Iozzo R. V., Zoeller J. J., Nyström A. (2009) Mol. Cells 27, 503–513 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Cohen-Kaplan V., Naroditsky I., Zetser A., Ilan N., Vlodavsky I., Doweck I. (2008) Int. J. Cancer 123, 2566–2573 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esko J. D., Selleck S. B. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 435–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Albuquerque R. J., Hayashi T., Cho W. G., Kleinman M. E., Dridi S., Takeda A., Baffi J. Z., Yamada K., Kaneko H., Green M. G., Chappell J., Wilting J., Weich H. A., Yamagami S., Amano S., Mizuki N., Alexander J. S., Peterson M. L., Brekken R. A., Hirashima M., Capoor S., Usui T., Ambati B. K., Ambati J. (2009) Nat. Med. 15, 1023–1030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mancardi S., Stanta G., Dusetti N., Bestagno M., Jussila L., Zweyer M., Lunazzi G., Dumont D., Alitalo K., Burrone O. R. (1999) Exp. Cell Res. 246, 368–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bame K. J., Esko J. D. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264, 8059–8065 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kreuger J., Lindahl U., Jemth P. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 363, 327–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang L., Fuster M., Sriramarao P., Esko J. D. (2005) Nat. Immunol. 6, 902–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lawrence R., Olson S. K., Steele R. E., Wang L., Warrior R., Cummings R. D., Esko J. D. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33674–33684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lawrence R., Kuberan B., Lech M., Beeler D. L., Rosenberg R. D. (2004) Glycobiology 14, 467–479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Watson J. V., Chambers S. H., Smith P. J. (1987) Cytometry 8, 1–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Aikawa J., Grobe K., Tsujimoto M., Esko J. D. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 5876–5882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Folkman J., Klagsbrun M., Sasse J., Wadzinski M., Ingber D., Vlodavsky I. (1988) Am. J. Pathol. 130, 393–400 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Söderberg O., Leuchowius K. J., Gullberg M., Jarvius M., Weibrecht I., Larsson L. G., Landegren U. (2008) Methods 45, 227–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kisanuki Y. Y., Hammer R. E., Miyazaki J., Williams S. C., Richardson J. A., Yanagisawa M. (2001) Dev. Biol. 230, 230–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Morisada T., Oike Y., Yamada Y., Urano T., Akao M., Kubota Y., Maekawa H., Kimura Y., Ohmura M., Miyamoto T., Nozawa S., Koh G. Y., Alitalo K., Suda T. (2005) Blood 105, 4649–4656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gale N. W., Thurston G., Hackett S. F., Renard R., Wang Q., McClain J., Martin C., Witte C., Witte M. H., Jackson D., Suri C., Campochiaro P. A., Wiegand S. J., Yancopoulos G. D. (2002) Dev. Cell 3, 411–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Yayon A., Klagsbrun M., Esko J. D., Leder P., Ornitz D. M. (1991) Cell 64, 841–848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ono K., Hattori H., Takeshita S., Kurita A., Ishihara M. (1999) Glycobiology 9, 705–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kreuger J., Nilsson I., Kerjaschki D., Petrova T., Alitalo K., Claesson-Welsh L. (2006) Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 26, 1073–1078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Longley R. L., Woods A., Fleetwood A., Cowling G. J., Gallagher J. T., Couchman J. R. (1999) J. Cell Sci. 112, 3421–3431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.