Abstract

Actin is a key regulator of RNA polymerase (Pol) II-dependent transcription. Positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), a Cdk9/cyclin T1 heterodimer, has been reported to play a critical role in transcription elongation. However, the relationship between actin and P-TEFb is still not clear. In this study, actin was found to interact with Cdk9, a catalytic subunit of P-TEFb, in elongation complexes. Using immunofluorescence and immunoprecipitation assays, Cdk9 was found to bind to G-actin through the conserved Thr-186 in the T-loop. Overexpression and in vitro kinase assays showed that G-actin promotes P-TEFb-dependent phosphorylation of the Pol II C-terminal domain. An in vitro transcription experiment revealed that the interaction between G-actin and Cdk9 stimulated Pol II transcription elongation. ChIP and immobilized template assays indicated that actin recruited Cdk9 to a transcriptional template in vivo and in vitro. Using cytokine IL-6-inducible p21 gene expression system, we revealed that actin recruited Cdk9 to endogenous gene. Moreover, overexpression of actin and Cdk9 increased histone H3 acetylation and acetylized histone H3 binding to a transcriptional template through the interaction with histone acetyltransferase, p300. Taken together, our results suggested that actin participates in transcription elongation by recruiting Cdk9 for phosphorylation of the Pol II C-terminal domain, and the actin-Cdk9 interaction promotes chromatin remodeling.

Keywords: Actin, Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP), Chromatin Remodeling, Transcription Elongation Factors, Transcription Regulation

Introduction

In eukaryotic cells, a large number of regulatory factors are involved directly in transcription and chromatin remodeling (1). Transcription of protein-coding genes is performed by RNA polymerase II (Pol II)2 and C-terminal repeat domain (CTD), which comprises the consensus repeat heptad 1YSPTSPS7, has been demonstrated to be the core regulatory portion of Pol II (2). Within the CTD heptad repeats, Cdk7-mediated phosphorylation of Ser-5 is necessary for Pol II to enter the initiation stage. On the other hand, phosphorylation of Ser-2 by Cdk9 promotes Pol II to enter the productive elongation stage (3–6). In addition, CTD phosphorylation is believed to help recruit factors involved in both elongation and chromatin remodeling (7). During the elongation stage, a number of negative and positive elongation factors are involved in several steps, including promoter clearance, transcriptional pausing, transcriptional arresting, and transcriptional termination (8, 9). Among these elongation factors, positive transcription elongation factor b (P-TEFb), which contains Cdk9 and a regulatory cyclin T1 (CycT1) subunit, plays a critical role during the transition from aborted to productive elongation (10, 11). Evidence has shown that P-TEFb is involved in most Pol II-dependent transcription (12). P-TEFb binds to HIV Tat, a viral transactivator, and facilitates viral transcription as well as replication (13). P-TEFb is also recruited to gene promoters by interacting with a variety of transcription factors (14–16). Moreover, new evidence shows that Cdk9 is involved in myocardial cell hypertrophy by phosphorylating histone acetyltransferase p300 and increasing RNA pol II-dependent transcription (17). Nevertheless, the mechanism regulating the recruitment of P-TEFb to a wide range of genes is not fully understood (18, 19). Recent studies have shown that about half of the total P-TEFb in the nucleus is bound reversibly to the 7SK snRNP (small nuclear ribonucleoprotein), which inhibits P-TEFb transcriptional activity (20). Upon dissociation of the inhibitory subunit, P-TEFb regains kinase activity and the ability to stimulate transcription elongation with other factors.

Several studies have demonstrated that actin plays a critical role in the nucleus. Actin is involved in diverse processes such as chromatin remodeling, transcription, and RNA processing (21–24). Nuclear actin interacts with Pol I, II, and III and plays a key role in basal transcription (25–29). Evidence has shown that actin is involved in the transcription elongation of class II genes. Actin binds to a specific subset of premessenger RNA binding proteins to form a molecular platform for the recruitment of histone acetyltransferase or histone deacetylase complexes along the active transcription unit (30–33), but the structural form of actin used in these processes remains unclear. Recent research on the N-WASP (neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein) and ARP2/3 complexes in Pol II transcription (34, 35) showed that actin-mediated Pol II transcriptional regulation is sensitive to the state of actin polymerization (36). However, a new study suggested that actin may be present in a monomeric or oligomeric form that is different from canonical actin filaments (33). In our study, we investigated further what type of actin is involved in Pol II transcription regulation and how it works.

In this study, Cdk9 was identified as an actin-interacting protein in elongation complexes (ECs). Cdk9 bound to G-actin through the conserved Thr-186 in the T-loop and actin-Cdk9 interaction stimulated Pol II transcription elongation in vivo and in vitro. In addition, actin recruited Cdk9 to the transcriptional template, and the actin-Cdk9 interaction enhanced chromatin acetylation. Collectively, our data have provided convincing evidence that G-actin stimulated Pol II transcription elongation occurs via the recruitment of Cdk9 for phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD and that chromatin remodeling is promoted by the actin-Cdk9 interaction.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Antibodies and Plasmids

Rabbit anti-HA antibody (Y-11), rabbit anti-Pol II antibody (N-20), rabbit anti-TFIIF (general transcription factor IIF) RAP74 antibody (C-18), rabbit anti-TFIIB (general transcription factor IIB) antibody (SI-1), rabbit anti-NELF-A antibody (H-240) and rabbit anti-p300 antibody (N-15) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Mouse anti-Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II antibody (H5) was purchased from Covance. Rabbit anti-Cdk9 antibody (catalog no. ab6544) and rabbit anti-ELL antibody (catalog no. ab64824) were purchased from Abcam. Mouse anti-β-actin antibody (catalog no. A5441), rabbit anti-FLAG M2 antibody (catalog no. F1804), mouse anti-β-tubulin antibody (catalog no. T4026), and rabbit anti-acetylated histone H3 antibody were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Fluorescent DNase I conjugates (D-7497) against G-actin and the phallotoxin conjugates (A-12380) against F-actin were purchased from Invitrogen. FLAG-tagged Cdk9 wild-type, FLAG-tagged Cdk9 mutants FLAG-S175A, FLAG-S175D, FLAG-T186A, FLAG-T186E, FLAG-D167N, FLAG-4A and FLAG-8A (20), and the FLAG-tagged CycT1 were provided generously by Dr. Ruichuan Chen (Xiamen University). The HA-tagged site-directed R62D and V159N actin mutants were constructed in our laboratory. GST-tagged Cdk9, CycT1, wild-type actin, R62D, V159N, and the Pol II CTD were generated by PCR and introduced into the pGEX-6p-1 vector (Amersham Biosciences). Plasmids pBSAd20 and pBSAd22 were provided kindly by Dr. Maria M. Konarska (Rockefeller University).

Immobilized Template Assay

The immobilized template assay was performed as described previously (37). Briefly, templates were prepared by PCR from pBSAd20 and pBSAd22 using the biotinylated upstream primer Ade-SE (5′-biotin-GTTGGGTAACGCCAGGG-3′) and the downstream primer Ade-AS (5′-GCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAA-3′). The fragments named Ad20 and Ad22 were gel-purified and bound to M-280 streptavidin Dynabeads (Dynal). The immobilized templates were then blocked with 1% BSA in transcription buffer (TB) (20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 100 mm KCl, 20% glycerol, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.5 mm DTT, and 250 μm PMSF) for 20 min at room temperature. After washing with TB, the bead-bound templates were resuspended in 28 μl of TB containing 0.05% Nonidet P-40. Transcription reactions (total volume, 105 μl) were performed at 30 °C for 30 min after addition of 6.7 mm MgCl2, 400 μm NTP, and 350 μg of whole HeLa nuclear extract (NE) (Promega). The bead-bound templates were washed gently (3 × 100 μl) with TB containing 0.05% Nonidet P-40 and 0.05% BSA. The templates were then digested with PvuII (New England Biolabs) as described previously (38). The supernatant was removed from the beads and ran on a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins on the gel were analyzed by immunoblotting. Beads lacking DNA were included as a negative control.

Immunoprecipitation and Immunoblotting Assays

HeLa NEs were prepared as described previously (39). Immunoprecipitation was carried out using HeLa NEs and the indicated antibodies at 4 °C for 3 h, followed by incubation for another 3 h with Protein A/G-Sepharose. After washing with lysis buffer (20 mm Tris/HCl (pH 8.0), 137 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P40, 10% glycerol, 1 mm Na3VO4, 1 mm PMSF, 10 mg/ml aprotinin, and 20 mg/ml leupeptin), the immunoprecipitates were resolved on SDS-PAGE, electrotransferred onto nitrocellulose membranes (Millipore), and probed with the indicated antibodies. Chemiluminescent detection was performed using ECL (GE Healthcare) plus Western blot reagents.

Immunofluorescence Assay

The immunofluorescence assays were conducted according to the procedures described by Zhou et al. (40) with minor modifications. The cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS for 10 min at room temperature and then permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 (Genview) for 10 min at 4 °C. The treated cells were washed with PBST (phosphate-buffered saline (pH 7.2) containing 0.05% Tween 20) three times before adding the appropriate antibodies at a dilution of 1:2000. After a 1-h incubation at room temperature, the cells were rinsed with PBST three times, and a second antibody was added to the cells and incubated for 30 min. The cells were again rinsed with PBST three times and then examined with confocal fluorescence microscope. Hoechst 33342 was used to stain the nuclei.

Immunodepletion of Cdk9 and/or Actin from HeLa NEs

Immunodepletion was performed by incubating 350 μg of HeLa NE containing 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and 0.5 m KCl with 3 mg of anti-Cdk9 and/or anti-actin antibodies at 4 °C for 30 min. The samples were treated with 20 μl of protein A/G-Sepharose beads (Amersham Biosciences), followed by three rounds of incubation. The depleted extracts were dialyzed using buffer D (20 mm HEPES-KOH (pH 7.9), 15% glycerol, 0.2 mm EDTA, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm DTT, and 1 mm PMSF) containing 0.1 m KCl prior to analyzing the samples in transcription and immobilized template assays.

In Vitro Kinase Assay

WT or mutant HA-actin was immunoprecipitated from the NEs of transfected HeLa cells. The immunoprecipitates were extensively washed with kinase buffer (25 mm Tris (pH 7.5), 2 mm DTT, 5 mm β-glycerophosphate, 1 mm Na3VO4, 10 mm MgCl2). After preincubation at 30 °C for 5 min, 30 μl of reaction was initiated by adding 3 μg of GST-CTD and 5 μm ATP. After 30 min, the reactions were terminated by adding 20 μl of 3× SDS sample buffer. The samples were then resolved with SDS-PAGE.

Transcription Assay

In vitro transcription reactions containing whole or immunodepleted HeLa NEs, DNA templates (Ad22), and indicated proteins (including GST, GST-actin, GST-R62D, GST-V159N, GST-Cdk9, and GST-CycT1, all of which were extracted from Escherichia coli BL21) were carried out as described previously (41). Transcription reaction (25 μl) contained 150 ng of Ad22 template and 35 μg of HeLa NE in 12 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.1 mm EDTA, 5 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 10 mm creatine phosphate, 12% (v/v) glycerol, 0.66 mm ATP, UTP, and CTP, 12.5 μm GTP, and 0.5 μCi of [α-32P]GTP (5000 Ci/mmol). The samples were incubated for 60 min at 30 °C, and then their RNA were analyzed on denaturing 6% polyacrylamide gels.

siRNA Transfection

HepG2 cells were transfected with either siRNA targeting CDK9 or actin. The siRNA efficiency of actin and Cdk9 was checked by Western blot HepG2 NEs, and tubulin was used as a negative control. After 48 h, the transfected cells were exposed to IL-6 (20 ng/ml) stimulation for 2 h prior to ChIP assay.

ChIP Assay

The ChIP assay was performed as described previously (42) with slight modifications. Briefly, HeLa cells were transfected with an AdMLP-luciferase DNA template, wild-type FLAG-Cdk9, mutant FLAG-Cdk9, and HA-actin expression plasmids. The total amount of expression vector was kept constant by adding an appropriate amount of empty vector. 72 h after transfection, the cells were harvested and the ChIP assays were performed using anti-FLAG antibody or anti-acetylated histone H3 antibody (Upstate). ChIP reagents were used according to the recommended protocol of Upstate. 1 × 106 cells were cross-linked with 1% paraformaldehyde and sheared by sonication. 1 ml of the 10-fold diluted reactions were incubated with antibodies, or without antibodies as a control, and then immunoprecipitated with protein A-agarose containing salmon sperm DNA. The precipitated materials were washed extensively with washing buffers, decross-linked, and subjected to PCR.

RESULTS

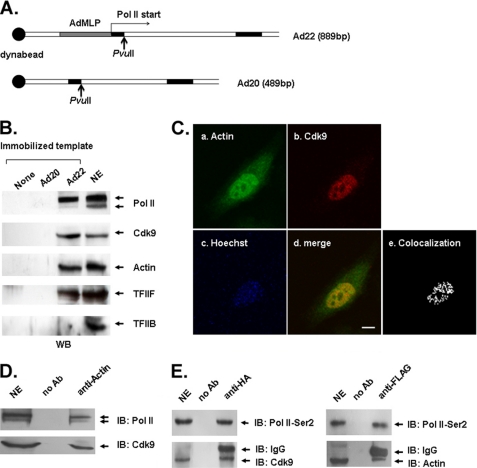

Actin Binds P-TEFb in Elongation Complexes

Recent reports have shown that actin, acting as a component of hnRNP complexes, is coupled to Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II CTD in active genes (33). P-TEFb is a key factor for Ser-2 phosphorylation of Pol II CTD in transcription elongation (10). In this study, the of role actin in P-TEFb-mediated phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD during transcription elongation was investigated. First, we performed an immobilized template assay to determine whether actin, P-TEFb, and Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II were present simultaneously in the transcription elongation complexes. Results from the immobilized template assay (Fig. 1B) showed that the antibody N-20 detects Pol II preferentially in the state of hyperphosphorylation, suggesting that the complexes formed on the Ad22 template were actively transcribing, and the absence of signals from the Ad20 template control reflected the lack of EC formation. Moreover, actin and Cdk9 also were detected at considerable levels in EC formed on the Ad22 template, but not on the Ad20 template or on the beads without DNA. Other EC-associated proteins such as TFIIF were also detected on Ad22. In contrast, TFIIB (general transcription factor IIB), a preinitiation complex component, was not present at a detectable level on the Ad22 template, thereby confirming that EC was the only complex present in our assay (Fig. 1B). Next, actin colocalization with Cdk9 was determined by immunofluorescence assay. As shown in Fig. 1C, endogenous Cdk9 was restricted to the nucleus, whereas endogenous actin was more extensively distributed throughout the cell. Yellow dots in the merged image showed the colocalization of Cdk9 and actin in the nucleus. Fig. 1C (d) was analyzed by the confocal microscope software Olympus Fluoview (version 1.7c) to generate white dots in Fig. 1C (e), which presented the colocalization of actin and Cdk9. Immunoprecipitation assay with NEs from untransfected or transfected HeLa cells (Fig. 1, D and E, respectively) was performed to confirm whether actin, Cdk9, and Pol II were present in the same complex. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blot with antibodies against Pol II and Cdk9 (Fig. 1D); HA tag, FLAG tag, and Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II (Fig. 1E). Both Cdk9 and Pol II were detected in the anti-actin immunoprecipitates from the NEs of untransfected HeLa cells (Fig. 1D). Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II and Cdk9 were detected in the immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-HA antibody from the NEs of transfected HeLa cells. Meanwhile, Ser-2-phosphorylation of Pol II and actin were found in the immunoprecipitation assay with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 1E). These results suggested that actin associates with P-TEFb and Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II in transcription elongation complexes.

FIGURE 1.

Actin binds P-TEFb in elongation complexes. A, diagram of the immobilized Ad20 and Ad22 DNA templates. The biotinylated 889-bp DNA transcription template named as Ad22 containing the AdMLP was linked to magnetic streptavidin beads. The Ad20 was a 490-bp DNA template identical to Ad22 but lacking the AdMLP. B, Western blot analysis of proteins released from the beads lacking DNA or linked to the Ad20 or Ad22 templates using the indicated antibodies. C, HeLa cells were stained with anti-actin antibody (a), anti-Cdk9 antibody (b), and Hoechst dye (c). The image (d) was a merge of a and b. Colocolization of actin and Cdk9 in d was analyzed by the confocal microscope software Olympus Fluoview (version 1.7c) to generate white dots in e. Scale bar, 10 μm. D, the immunoprecipitates were obtained from the NE of HeLa cells using an anti-actin antibody. Then, the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) in combination with antibodies against Pol II and Cdk9. E, HeLa cells were transfected with plasmids encoding HA-tagged actin or FLAG-tagged Cdk9. The NEs from the transfected HeLa cells were immunoprecipitated with either anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibody. The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by Western blot with anti-Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II (Pol II-Ser2), anti-Cdk9, or anti-actin antibodies, respectively.

Actin Interacts with Conserved Thr-186 Residue in T-loop of Transcriptionally Active P-TEFb

Because Cdk9 associated with actin in elongation complexes, the exact interaction mechanism of the two proteins were next determined. Phosphorylation of Thr-186 in the T-loop of Cdk9 has been reported to be essential for the Pol II CTD substrate to access the catalytic core of the enzyme (43). To determine whether this amino acid or other amino acids might be involved in actin-Cdk9 binding, a series of FLAG-tagged Cdk9 plasmids with site-directed point mutations were transfected into HeLa cells (as indicated under “Experimental Procedures”). Then, the transfected cells were examined by immunoprecipitation and Western blot. As shown in Fig. 2A, T186A and T186E mutations significantly reduced the binding of actin to Cdk9, whereas mutations in Ser-175 in the T-loops of Cdk9 did not affect the binding of actin to Cdk9. In contrast, D167N, which destroys Cdk9 kinase activity, and the alanine substitutions of either four or eight Ser/Thr residues near the C terminus of Cdk9 (named 4A or 8A), which also disrupts the formation of the Tat-TAR-P-TEFb (44) ternary complex, had no obvious effect on actin-Cdk9 binding. The data described above indicate that actin interacts with the conserved Thr-186 in the T-loop.

FIGURE 2.

Actin interacts with Thr-186 in the T-loop of transcriptionally active P-TEFb. A, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids, expressing either FLAG-tagged wild-type or mutant Cdk9. The immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-FLAG antibody from the NEs of transfected HeLa cells were subjected to SDS-PAGE and analyzed by immunoblotting (IB) with the indicated antibodies. The proteins expressed in NEs were shown as a control in the right panel. B, HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged actin were treated with actinomycin D (ActD) or the solvent DMSO (a negative control). Immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-HA antibody were detected with anti-Cdk9 antibody through Western blot (WB). The HA tag, Cdk9, and β-tubulin in the NEs were shown as controls for transfection and loading. C, HeLa cells were transfected with FLAG-tagged Cdk9. The lysates of NEs of the transfected HeLa cells were then immunoprecipitated with anti-FLAG antibody and analyzed by Western blot using an anti-actin antibody. FLAG tag, actin, and β-tubulin in the NEs were shown as controls for transfection and loading.

In HeLa cells, the repression of transcriptionally active P-TEFb by 7SK-HEXIM complexes could be disrupted by actinomycin D, transcription inhibitor 5,6-dichloro-1-β-d-ribofuranosylbenzimidazole, and UV irradiation (45–47). To investigate whether actin interacts with transcriptionally active Cdk9, HeLa cells transfected with HA-actin or FLAG-Cdk9 were treated with the solvent DMSO (a negative control) or actinomycin D. The immunoprecipitates obtained with anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibodies were detected with anti-Cdk9 or anti-actin antibodies by Western blot. As shown in Fig. 2, B and C, the actin-Cdk9 interaction was enhanced by treatment with actinomycin D, which could induce disruption of the 7SK snRNP (small nuclear ribonucleoprotein) and activation of P-TEFb. DMSO treatment had little effect. The data described above indicate that actin interacts with transcriptionally active P-TEFb. Taken together, these data show that actin interacts with the conserved Thr-186 in the T-loop of transcriptionally active P-TEFb.

P-TEFb Mainly Interacts with Monomeric Actin

It has been demonstrated that actin is associated with Pol II-mediated transcription, but its structural form in this process remained unclear. There was evidence that actin-mediated Pol II transcriptional regulation might be sensitive to the state of actin polymerization (34–36), but new evidence showed that transcriptionally active actin might be present in monomeric or oligomeric forms, which are different from canonical actin filaments (33). To determine which form of actin was involved in the association with Cdk9, co-localization of monomeric and polymeric actin with endogenous Cdk9 was examined under a confocal microscope. As shown in Fig. 3, A and B, antibody labeling against G-actin and Cdk9 showed that G-actin was distributed throughout the cell (a) and Cdk9 was localized in the nucleus (b). The merged image of G-actin and Cdk9 showed that the two proteins were colocalized in the nucleus (Fig. 3A, d). Fig. 3A (d) and Fig. 3B (i) were analyzed by the confocal microscope software Olympus Fluoview (version 1.7c) to generate white dots in Fig. 3, A and B (e and j, respectively). Fig. 3A (e) presented the colocalization of G-actin and Cdk9, whereas Fig. 3B (j) presented the colocalization of F-actin and Cdk9. The colocalization in Fig. 3A (e) was highly significant compared with that of Fig. 3B (j). These results indicate that Cdk9 mainly associates with monomeric actin. To provide further evidence for the involvement of monomeric actin in actin-Cdk9 binding, HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged actin were treated with drugs that affect actin polymerization, and 1% DMSO was used as a control. After immunoprecipitation with anti-HA antibody, the amount of Cdk9 in the immunoprecipitates was detected with anti-Cdk9 antibody. As shown in Fig. 3, C and D, jasplakinolide, which promotes the assembly of actin filaments, inhibited actin-Cdk9 binding. On the other hand, cytochalasin D, which inhibits actin polymerization, stimulated the association of Cdk9 and actin. Taken together, the data show that monomeric actin is mainly responsible for the interaction with P-TEFb.

FIGURE 3.

P-TEFb mainly interacts with monomeric actin. A and B, G- or F-actin was labeled with fluorescent DNase I conjugates or phallotoxin conjugates (a or f) respectively, Cdk9 was labeled with anti-Cdk9 antibody (b and g), and nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (c and h). d was the merge of a and b, and i was the merge of f and g. d and i were analyzed by the confocal microscope software Olympus Fluoview (version 1.7c) to generate white dots in e and j, respectively. Scale bar, 10 μm. C, HeLa cells transfected with HA-tagged actin and a control vector were treated with jasplakinolide (Jas), cytochalasin D (CD), or 1% DMSO. Immunoprecipitates (IP) were obtained with anti-HA antibody from the NEs of transfected HeLa cells, and the amounts of Cdk9 were analyzed by Western blot (WB). HA tag, Cdk9, and β-tubulin expression in the NEs were shown as controls for transfection and loading. D, showing the amount of Cdk9 interacted with HA-actin after treatment with jasplakinolide, cytochalasin D, or 1% DMSO. The data shown are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments.

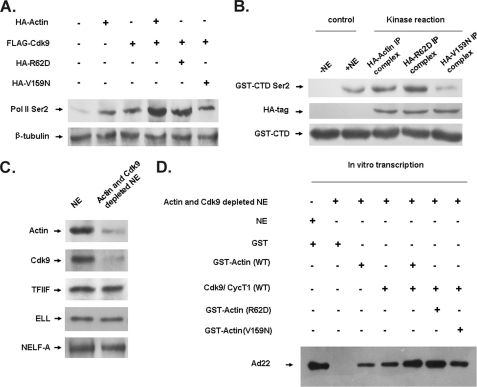

Interaction between G-actin and P-TEFb Is Critical for Transcription Elongation

After showing that G-actin was associated with P-TEFb, we next tested whether G-actin or F-actin in particular affected the phosphorylation of Ser-2 in Pol II CTD, a process known to be mediated by P-TEFb. In Fig. 4A, Ser-2 CTD phosphorylation was stimulated by the overexpression of wt actin or Cdk9 respectively, and overexpression of both proteins led to further increase in Ser-2 phosphorylation. Co-transfection of Cdk9 and R62D (a nonpolymerizable actin point mutant that is not incorporated into F-actin) stimulated Ser-2 phosphorylation to a similar degree as observed with the co-transfection of Cdk9 and WT actin. Conversely, co-transfection of Cdk9 and V159N (an actin point mutant that stabilizes F-actin) only stimulated Ser-2 phosphorylation to the level induced by the overexpression of Cdk9 alone, showing that G-actin was responsible for the actin-Cdk9 interaction, which lead to phosphorylation of Ser-2 in the Pol II CTD and F-actin had little effect. To confirm the above results, we performed an in vitro kinase assay to examine the contribution of G-actin to Pol II CTD phosphorylation (GST-CTD). As shown in Fig. 4B, compared with the control, phosphorylation of Ser-2 in GST-CTD induced by the HA-R62D immunoprecipitate was similar to that induced by WT HA-actin immunoprecipitate. Meanwhile, HA-V159N immunoprecipitate had little effect on the phosphorylation of Ser-2 in GST-CTD. These data indicate that phosphorylation of Ser-2 in Pol II CTD was mediated by the interaction of G-actin and P-TEFb.

FIGURE 4.

Interaction between G-actin and P-TEFb is critical for transcription elongation. A, nuclear extract from the HeLa cells transfected with indicated plasmids (top) were immunoblotted with antibody specific for Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II CTD, and β-tubulin was used as a control. B, in vitro kinase reactions were performed with the indicated immunoprecipitation (IP) complexes of WT or mutant HA-actin and GST-CTD as a substrate. Phosphorylated GST-CTD was subjected to SDS-PAGE and detected with anti-Ser-2-phosphorylated Pol II CTD antibody. The HA tag and GST-CTD at the bottom were shown as controls. C, the depletion specificity of actin and Cdk9 was checked by Western blot using NEs from the transfected HeLa cells, and TFIIF, ELL, and NELF-A were used as negative controls. D, different combinations of WT or mutant actin, with or without P-TEFb, were introduced into the in vitro transcription system in the NEs of Cdk9 and actin-depleted HeLa cells. RNA transcripts derived from the transcription template Ad22 were analyzed as described under “Experimental Procedures.”

To further examine the role of actin and P-TEFb in transcription elongation, we performed an in vitro transcription assay utilizing HeLa NE depleted of both actin and Cdk9 (as indicated in “Experimental Procedures”). As shown in Fig. 4C, Western blot was carried out with the indicated antibodies using transcription elongation factors TFIIF, ELL, and NELF-A as controls, and the blotting confirmed the specificity of depletion in the NEs. The addition of either GST-Cdk9/CycT1 or GST-actin (WT) into the in vitro transcription system only partially restored transcription, whereas the addition of both proteins fully restored transcription. Furthermore, addition of G-actin and Cdk9/CycT1 also fully restored transcription of the Ad22 templates, but the addition of F-actin and Cdk9/CyT1 could not (Fig. 4D). These results demonstrate that the interaction between G-actin and P-TEFb is critical for transcription elongation.

Actin Recruits P-TEFb to Transcriptional Template

To further understand the actin-P-TEFb interaction in transcription elongation, we performed a ChIP assay to investigate the contribution of actin to the transcriptional activity of P-TEFb. Compared with WT Cdk9, T186A showed significantly reduced binding to the promoter and coding region of the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 5, A and B). Because T186A could not bind to actin, we hypothesized that the binding of Cdk9 to the transcriptional template is mediated mainly by actin. We then performed an in vitro-immobilized template assay to confirm the effect of actin on the recruitment of Cdk9 to immobilized biotin-Ad22 DNA templates. Actin- or Cdk9-depleted HeLa NEs were prepared (Fig. 5, C and D, left panel). The immobilized DNA template was then incubated under transcription conditions with HeLa NE, actin-depleted NE, or Ckd9-depleted NE. The results indicated that Cdk9 could not bind to the Ad22 template when actin was specifically removed from the NE (Fig. 5C, right panel), but actin still bound to the Ad22 template in the absence of Cdk9 (Fig. 5D, right panel). Our data strongly suggest a role of actin in recruiting P-TEFb to the transcriptional template both in vivo and in vitro.

FIGURE 5.

Actin recruits P-TEFb to the transcriptional template. A, schematic representation of the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene template. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene template, FLAG-tagged WT, or T186A-Cdk9. The ChIP assay was performed with anti-FLAG antibody. The promoter and coding regions of the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene template were PCR-amplified. WT or mutant FLAG-tagged Cdk9 associated with the immunoprecipitated (IP) chromatin were used as controls. C and D (left panel), Western blot (WB) analysis of NEs in which endogenous actin or Cdk9 was immunodepleted under high salt conditions. TFIIF was used as a negative control. Right panel, the depleted NEs were incubated with immobilized Ad22 template under transcription conditions. The Cdk9 and actin retained by the template were detected with Western blot using TFIIF as a control.

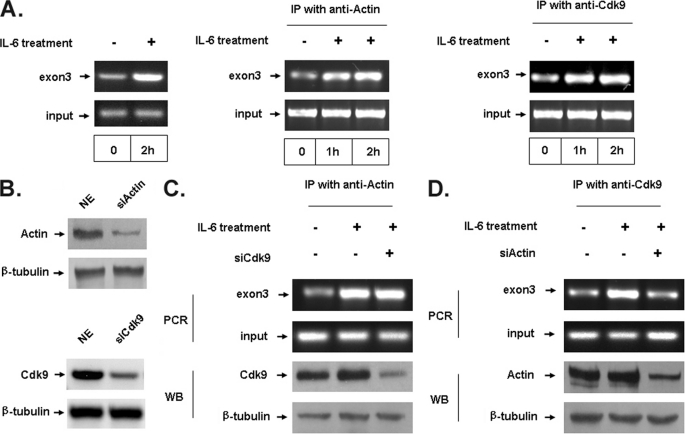

It is particularly important to evaluate whether native actin recruit Cdk9 to endogenous genes. To this end, we used p21 as a target endogenous gene, which could be induced by IL-6 in HepG2 cells. First, ChIP assay was performed using a pair of primer that cover exon3 of the p21 gene. As shown in Fig. 6A, actin and Cdk9 were both recruited to the p21 gene following IL-6 stimulation. siRNA transfection was used to silence endogenous actin or Cdk9 expression to confirm the role of endogenous actin and Cdk9 in the recruitment to the endogenous p21 gene following IL-6 stimulation. As shown in Fig. 6B, transfection of actin or Cdk9 siRNA (siActin or siCdk9) significantly reduced actin or Cdk9 protein levels. ChIP assay was carried out to examine the effect of actin or Cdk9 knockdown on their recruitment to the IL-6-induced p21 gene. In Fig. 6C, Cdk9 knockdown did not affect the recruitment of actin to p21 gene following IL-6 stimulation. Contrastively, the recruitment of Cdk9 to the p21 gene following IL-6 stimulation was decreased by actin knockdown (Fig. 6D). These results indicate that native actin could recruit Cdk9 to an endogenous gene.

FIGURE 6.

Actin recruited Cdk9 to endogenous genes. A, HepG2 cells were stimulated for 2 h with IL-6 (20 ng/ml). Total RNA was isolated and expression of the p21 gene was analyzed by RT-PCR. In parallel, the recruitment of actin or Cdk9 to the p21 gene was analyzed by ChIP experiments. B, HepG2 cells in six-well plates were transiently transfected with 100 nm actin siRNA (siActin) or Cdk9 siRNA (siCDK9). 72 h after transfection, equivalent amounts of protein from the whole cell lysates were used for immunoblotting. β-Tubulin at bottom was shown as a control. C and D, siRNA transfection was performed as described in B. 48 h after siRNA transfection, cells were treated with IL-6 (20 ng/ml) for 2 h. ChIP assay was performed using anti-actin or anti-Cdk9 antibody. Actin and Cdk9 in NEs showed the efficiency of siRNA. WB, Western blot; IP, immunoprecipitation.

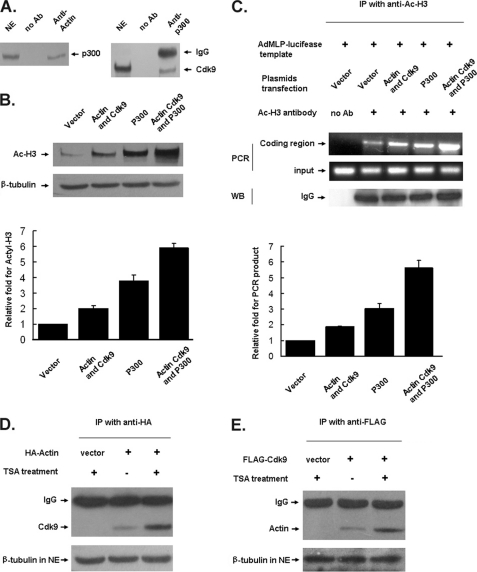

Actin-P-TEFb Interaction Enhances Chromatin Acetylation by Activating p300

Recent studies showed that chromatin modifications and remodeling take place during both initiation and elongation of transcription (48, 49). Moreover, it was believed previously that Pol II CTD phosphorylation might help recruit factors involved in both elongation and chromatin remodeling (7). Studies on actin showed that actin was involved in recruiting chromatin modifiers to active genes (31, 32). Interestingly, P-TEFb also was recruited to acetylated chromatin by a mammalian bromodomain protein named Brd4 (19). New evidence showed that Cdk9 phosphorylates histone acetyltransferase p300 and increases RNA pol II-dependent transcription (17). Therefore, we propose that the interaction of actin and Cdk9 might play a role in chromatin acetylation to facilitate transcription elongation by activating p300. As shown in Fig. 7A, p300 was detected in the anti-actin immunoprecipitates from the NE of HeLa cells and Cdk9 was also detected in the anti-p300 immunoprecipitates from the same NE. In the transfection assay, overexpression of both actin and Cdk9 or p300 alone enhanced the level of histone H3 acetylation. Overexpression of actin, Cdk9, and p300 together significantly enhanced the level of histone H3 acetylation (Fig. 7B). ChIP assay performed on HeLa cells transfected with the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene showed that interaction of actin-Cdk9 with p300 stimulated acetylated histone H3 binding to coding region of the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 7C). The binding capacity of actin and Cdk9 was also increased under a high acetylation level in HeLa cells as shown in the immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 7, D and E). These results suggest that the actin-P-TEFb interaction enhances chromatin acetylation of active genes by activating p300.

FIGURE 7.

Actin-P-TEFb interaction enhances chromatin acetylation by activating p300. A, the immunoprecipitates were obtained from the NEs of HeLa cells using anti-actin antibody or anti-p300 antibody. Next, the immunoprecipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting in combination with antibodies against p300 or Cdk9. B, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated expression plasmids. The whole cell lysates were subjected to Western blot (WB) analysis using anti-Ac-H3 antibody, and β-tubulin was shown as a control. Amount of acetylated histone 3 after transfection with indicated plasmids was quantified. The data shown are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. C, the ChIP experiment was performed using anti-Ac-H3 antibody with the HeLa cells transfected with the AdMLP-luciferase reporter gene and indicated expression plasmids. The coding region of the AdMLP-luciferase gene was PCR-amplified. Relative fold for PCR product was quantified. The data shown are the mean ± S.D. from three independent experiments. D and E, HeLa cells were transfected with HA-tagged actin or FLAG-tagged Cdk9 and then treated with histone deacetylase inhibitor trichostatin A (TSA) (200 ng/ml) for 4 h. An immunoprecipitation assay was performed with anti-HA or anti-FLAG antibody, and the resulting immunoprecipitates (IP) were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies against Cdk9 or actin. β-Tubulin was used as a control.

DISCUSSION

In our present study, G-actin was found to stimulate Pol II transcription elongation by recruiting P-TEFb to phosphorylate Ser-2 of the Pol II CTD. The interaction between actin and P-TEFb also stimulated chromatin remodeling, which in turn facilitated transcription elongation. P-TEFb was identified as the nuclear actin-binding protein in ECs. Interaction between actin and transcriptionally active P-TEFb was demonstrated to be essential for P-TEFb to stimulate Pol II transcription elongation. Furthermore, actin was shown to recruit P-TEFb to transcriptional templates in vivo and in vitro. Native actin was also shown to recruit native P-TEFb to the endogenous gene. Finally, we demonstrated that the actin-P-TEFb interaction resulted in the promotion of histone H3 acetylation, and the acetylated histone H3 bound to the transcriptional template.

Actin exists as an equilibrium between monomers (G-actin) and polymers (F-actin) in the cytoplasm. In most cell types, the concentration of actin in the nucleus is too low to form an actin-based filament (50). Nevertheless, a recent study demonstrated the existence of polymeric forms of actin in the nucleus (51). Using fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, both rapid and slow moving populations of nuclear actin were observed, corresponding to the monomeric and polymeric forms. Indeed, nuclear actin does not form long F-actin filaments but forms shorter, potentially novel conformations that are distinct from those found as conventional actin filaments in the cytoplasm (52). This suggests that the plasticity of the actin molecule may facilitate its diverse functions in the nucleus. Several studies of the involvement of N-WASP (neuronal Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein) and the ARP2/3 complex in Pol II transcription showed that actin-mediated Pol II transcriptional regulation may be sensitive to actin polymerization status (34–36). However, other studies showed that transcriptionally active actin may be present in a monomeric or oligomeric form that is different from canonical actin filaments (33). In this study, we demonstrated that G-actin was associated with endogenous P-TEFb in the nucleus with an immunofluorescence assay. Jasplakinolide, a drug that promotes the assembly of actin filaments, inhibited the association of actin-P-TEFb, whereas cytochalasin D, a drug that inhibits actin polymerization, stimulated the association. We have shown that co-transfection of the G-actin mutant R62D and Cdk9 increased the Ser-2 phosphorylation level in the Pol II CTD to the same degree as co-transfection of WT actin and Cdk9. In contrast, co-transfection of the F-actin mutant V159N with Cdk9 induced similar changes as the Cdk9 single transfection. We have also shown that the interaction between G-actin and P-TEFb was critical for transcription elongation. Taken together, our results suggest that transcriptionally active actin could exist in a monomeric form in the nuclei, a finding that agrees with a recent study demonstrating that actin can be coprecipitated in a complex with hnRNP U (heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein U), PCAF (p300/CBP-associated factor), and Pol II by DNase I affinity chromatography, a procedure that has a high affinity for monomeric actin (33).

Previous studies showed that P-TEFb could be recruited to various DNA templates by specific activators (14, 15). Recent studies showed that P-TEFb was required for efficient transcription elongation of most genes (12) and that actin was involved in overall Pol II-dependent transcription. We surmise that actin is a general P-TEFb recruitment factor for most Pol II-dependent transcription. To confirm this hypothesis, we performed immobilized template and ChIP assays with a DNA-coding sequence linked to the universal promoter AdMLP as a target template. The fact that actin can recruit P-TEFb to the universal DNA template and the actin-P-TEFb interaction is able to promote Ser-2 phosphorylation of the CTD in vivo suggests a general role for actin in P-TEFb-mediated gene transcription elongation.

However, Pol II-dependent transcription elongation is believed to be accompanied by chromatin remodeling. Phosphorylation of the Pol II CTD also helps to recruit factors for this process (7). A large number of actin-related proteins are components of chromatin remodeling complexes and function in transcription regulation (53, 54). Recent observations demonstrated that Cdk9 kinase activity affects the p300-induced histone acetylation (17). Therefore, we suppose actin-Cdk9 interaction might increase p300-induced acetylation of histones. In this study, we have provided experimental evidence that actin-Cdk9 interacts with p300, and the overexpression of actin and Cdk9 enhances the level of histone H3 acetylation. The ChIP assay also showed that the interaction of actin and Cdk9 stimulated acetylized histone H3 binding to an active gene. Taken together, these data support the hypothesis that the interaction of actin with P-TEFb facilitates transcription elongation by promoting phosphorylation of CTD-Ser-2 as well as chromatin acetylation.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ruichuan Chen (Key Laboratory of the Ministry of Education for Cell Biology and Tumor Cell Engineering, School of Life Sciences, Xiamen University) for providing the FLAG-Cdk9, S175A, S175D, T186A, T186E, D167N, 4A, and 8A mutants and FLAG-CycT1. We also thank Dr. Maria M Konarska (Laboratory of Molecular Biology and Biochemistry, Rockefeller University) for providing plasmids pBSAd20 and pBSAd22.

This work was supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (Grant 2005CB522404) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant 90608021).

- Pol II

- RNA polymerase II

- G-actin

- globular actin

- P-TEFb

- positive transcription elongation factor b

- EC

- elongation complex

- CTD

- C-terminal repeat domain

- NE

- nuclear extract

- DMSO

- dimethyl sulfoxide

- AdMLP

- adenovirus major late promoter

- TFIIF

- general transcription factor IIF.

REFERENCES

- 1. Orphanides G., Reinberg D. (2002) Cell 108, 439–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Corden J. L. (1990) Trends Biochem. Sci 15, 383–387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dvir A., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 94, 9006–9010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. O'Brien T., Hardin S., Greenleaf A., Lis J. T. (1994) Nature 370, 75–77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Marshall N. F., Peng J., Xie Z., Price D. H. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27176–27183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sims R. J., 3rd, Belotserkovskaya R., Reinberg D. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 2437–2468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hirose Y., Ohkuma Y. (2007) J. Biochem. 141, 601–608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Shilatifard A., Conaway R. C., Conaway J. W. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 72, 693–715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Arndt K. M., Kane C. M. (2003) Trends Genet. 19, 543–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Price D. H. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 2629–2634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jones K. A. (1997) Genes Dev. 11, 2593–2599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Chao S. H., Price D. H. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31793–31799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wei P., Garber M. E., Fang S. M., Fischer W. H., Jones K. A. (1998) Cell 92, 451–462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Barboric M., Nissen R. M., Kanazawa S., Jabrane-Ferrat N., Peterlin B. M. (2001) Mol. Cell 8, 327–337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kanazawa S., Soucek L., Evan G., Okamoto T., Peterlin B. M. (2003) Oncogene 22, 5707–5711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Simone C., Bagella L., Bellan C., Giordano A. (2002) Oncogene 21, 4158–4165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Sunagawa Y., Morimoto T., Takaya T., Kaichi S., Wada H., Kawamura T., Fujita M., Shimatsu A., Kita T., Hasegawa K. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 9556–9568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yang Z., Yik J. H., Chen R., He N., Jang M. K., Ozato K., Zhou Q. (2005) Mol Cell 19, 535–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jang M. K., Mochizuki K., Zhou M., Jeong H. S., Brady J. N., Ozato K. (2005) Mol Cell 19, 523–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chen R., Yang Z., Zhou Q. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 4153–4160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhao K., Wang W., Rando O. J., Xue Y., Swiderek K., Kuo A., Crabtree G. R. (1998) Cell 95, 625–636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Grummt I. (2006) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 16, 191–196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Percipalle P., Visa N. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172, 967–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Bettinger B. T., Gilbert D. M., Amberg D. C. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 410–415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hofmann W. A., Stojiljkovic L., Fuchsova B., Vargas G. M., Mavrommatis E., Philimonenko V., Kysela K., Goodrich J. A., Lessard J. L., Hope T. J., Hozak P., de Lanerolle P. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1094–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fomproix N., Percipalle P. (2004) Exp. Cell Res. 294, 140–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Philimonenko V. V., Zhao J., Iben S., Dingova H., Kysela K., Kahle M., Zentgraf H., Hofmann W. A., de Lanerolle P., Hozak P., Grummt I. (2004) Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1165–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ye J., Zhao J., Hoffmann-Rohrer U., Grummt I. (2008) Genes Dev. 22, 322–330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hu P., Wu S., Hernandez N. (2004) Genes Dev. 18, 3010–3015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Percipalle P., Fomproix N., Kylberg K., Miralles F., Bjorkroth B., Daneholt B., Visa N. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 100, 6475–6480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kukalev A., Nord Y., Palmberg C., Bergman T., Percipalle P. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 238–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sjölinder M., Björk P., Söderberg E., Sabri N., Farrants A. K., Visa N. (2005) Genes Dev. 19, 1871–1884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Obrdlik A., Kukalev A., Louvet E., Farrants A. K., Caputo L., Percipalle P. (2008) Mol. Cell. Biol. 28, 6342–6357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wu X., Yoo Y., Okuhama N. N., Tucker P. W., Liu G., Guan J. L. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 756–763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Yoo Y., Wu X., Guan J. L. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 7616–7623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vieu E., Hernandez N. (2006) Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 650–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kameoka S., Duque P., Konarska M. M. (2004) EMBO J. 23, 1782–1791 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ranish J. A., Yudkovsky N., Hahn S. (1999) Genes Dev. 13, 49–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mayeda A., Krainer A. R. (1999) Methods Mol. Biol. 118, 309–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Zhou D., Jiang X., Xu R., Cai Y., Hu J., Xu G., Zou Y., Zeng Y. (2008) Cell Mol. Neurobiol. 28, 895–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Zhou Q., Sharp P. A. (1995) EMBO J. 14, 321–328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Choi C. H., Hiromura M., Usheva A. (2003) Nature 424, 965–969 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Baumli S., Lolli G., Lowe E. D., Troiani S., Rusconi L., Bullock A. N., Debreczeni J. E., Knapp S., Johnson L. N. (2008) EMBO J. 27, 1907–1918 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Fong Y. W., Zhou Q. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 5897–5907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Nguyen V. T., Kiss T., Michels A. A., Bensaude O. (2001) Nature 414, 322–325 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Yang Z., Zhu Q., Luo K., Zhou Q. (2001) Nature 414, 317–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Yik J. H., Chen R., Pezda A. C., Samford C. S., Zhou Q. (2004) Mol. Cell. Biol. 24, 5094–5105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Mellor J. (2005) Mol. Cell 19, 147–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Saha A., Wittmeyer J., Cairns B. R. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 437–447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Stüven T., Hartmann E., Görlich D. (2003) EMBO J. 22, 5928–5940 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. McDonald D., Carrero G., Andrin C., de Vries G., Hendzel M. J. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 13, 541–552 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Jockusch B. M., Schoenenberger C. A., Stetefeld J., Aebi U. (2006) Trends Cell Biol. 16, 391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Olave I. A., Reck-Peterson S. L., Crabtree G. R. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 755–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pederson T., Aebi U. (2002) J. Struct. Biol. 140, 3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]