Abstract

Summary

Bone marrow (BM) has been for many years primarily envisioned as the ‘home organ’ of hematopoietic stem cells (HSC). In this review we will discuss current views of the BM stem cell compartment and present data showing that BM in addition to HSC also contains a heterogeneous population of non-hematopoietic stem cells. These cells have been variously described in the literature as i) endothelial progenitor cells (EPC), ii) mes-enchymal stem cells (MSC), iii) multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPC), iv) marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells, v) multipotent adult stem cells (MACS) and vi) very small embryonic-like (VSEL) stem cells. It is likely that in many cases similar or overlapping populations of primitive stem cells in the BM were detected using different experimental strategies and hence were assigned different names.

Key Words: VSEL, CXCR4, Oct-4, Nanog, SSEA

Abstract

Zusammenfassung

Knochenmark (KM) wurde über viele Jahre in erster Linie als das Ursprungsorgan für hämatopoetische Stammzellen (HSC) angesehen. In der vorliegenden Übersichtsarbeit werden die aktuellen Meinungen bezüglich des KM-Stammzellkompartiments diskutiert und Daten präsentiert, die zeigen, dass das KM neben den HSC auch eine heterogene Population von nichthämatopetischen Stammzellen enthält. Diese Zellen sind in der Literatur vielfach beschrieben: 1) als endotheliale Progenitorzellen, 2) mesenchymale Stammzellen (MSC), 3) als multipotente adulte Progenitorzellen (MAPC), 4) als «marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells», 5) als multipotente adulte Stammzellen (MACS) und 6) als «very small embryonic-like (VSEL) stem cells». Es ist zu vermuten, dass in vielen Fällen durch unterschiedliche experimentelle Strategien ähnliche oder überlappende Populationen von primitiven Stammzellen im KM detektiert wurden, die dann unterschiedlich benannt wurden.

Bone Marrow-Derived Stem Cells

Evidence accumulated that bone marrow (BM) in addition to hematopoietic stem cells (HSC) also contains a heterogeneous population of non-hematopoietic stem cells. Several types of non-hematopoietic stem/primitive cells have been variously described in the literature as i) endothelial progenitor cells (EPC) [1, 2], ii) mesenchymal stem cells (MSC) [3, 4], iii) multipotent adult progenitor cells (MAPC) [5], iv) marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells [6], v) multipotent adult stem cells (MACS) [7], and vi) very small embryonic-like (VSEL) stem cells [8]. Some authors suggested that the BM could also be a potential source of precursors of germ cells (oocytes and spermatogonial cells) [9, 10]. However, this observation needs to be confirmed.

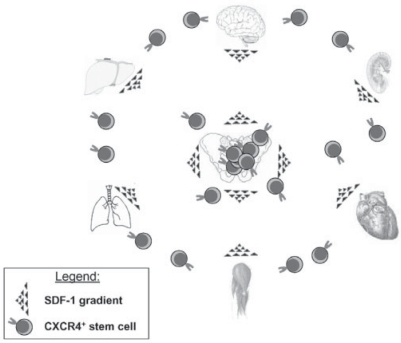

It is hypothesized that the presence of these various populations of stem cells in the BM is a result of the ‘developmental migration’ of stem cells during ontogenesis and the presence of the permissive environment that attracts them to the BM tissue. HSC and other non-hematopoietic stem cells are actively chemoattracted by factors secreted by BM stroma cells and osteoblasts (e.g., stromal derived factor-1 (SDF-1), hepatocyte growth factor (HGF)) and colonize marrow by the end of the second and the beginning of the third trimester of gestation [11]. Accumulating evidence suggests that these non-hematopoietic stem cells residing in the BM play some role in the homeostasis/turnover of peripheral tissues and if needed could be released/mobilized from the BM into circulation during tissue injury and stress (fig. 1), facilitating the regeneration of damaged organs [12, 13, 14, 15, 16].

Fig. 1.

BM-derived non-hematopoietic stem cells circulate in peripheral blood. The concept is presented based on the assumption that CXCR4+ non-hematopoietic stem cells circulate in the peripheral blood. Although the percentage of these cells circulating in peripheral blood is much lower than that of early hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells, these mobilized non-hematopoietic stem cells may play an important role in tissue repair following injury. The mobilization of these cells occurs during tissue damage/injury (e.g., heart infarct, stroke, toxic liver damage). It is postulated that after mobilization into peripheral blood CXCR4+ non-hematopoietic stem cells may subsequently be chemoattracted by an SDF-1 gradient to the damaged tissues. In this context BM tissue becomes a ‘hideout’ not only of HSC but also of circulating CXCR4+ non-hematopoietic stem cells (e.g. EPC, MSC or VSEL stem cells). These cells are deposited early in development and consequently reside in the BM, and we hypothesize that they could play an important role in tissue/organ repair as a mobile reserve pool of PSC. The trafficking of these cells involves, besides the SDF-1-CXCR4 axis, several other motomorphogens such as HGF, VEGF and LIF.

Bone Marrow Non-Hematopoietic Stem Cells – Lessons Learned from the Concept Postulating the Phenomenon of ‘Plasticity’ of Hematopoietic Stem Cells

Several investigators in the past few years have demonstrated that BM-derived cells can contribute to the regeneration of various organs and tissues [17, 18, 19]. These observations were mainly explained by the hypothesis that HSC are ‘plastic’ and thus could transdedifferentiate into stem cells committed for various non-hematopoietic organs and tissues [20]. For this phenomenon to occur requires i) a parallel switch of commitment for HSC in the compartment of monopotent (tissue/organ-committed) stem cells or ii), as postulated, a step back in the differentiation process of HSC with their de-differentation into multipotent (one germ layer-committed) or even pluripotent (three germ layer-committed) stem cells (PSC).

This hypothetical possibility that HSC are plastic and able to trans-dedifferentiate raised much hope that HSC isolated from BM, mobilized peripheral blood (mPB) or cord blood (CB) could become a universal source of stem cells for tissue/organ repair. This excitement was bolstered at that time by several reports that demonstrated the remarkable regenerative potential of ‘HSC’ in animal models, for example after heart infarct [18], stroke [21], spinal cord injury [22], and liver damage [23].

However, despite of these first exciting and promising reports, the role of BM stem cells in the repair of damaged organs has become controversial [24, 25]. Further experiments with highly purified populations of HSC showed them not to be effective in regenerating damaged heart [26] or brain [27]. In response to these unexpected results the scientific community became polarized in its view of the concept of stem cell plasticity.

These obvious discrepancies in published results could be explained by differences in the tissue injury models employed and/or problems in detection of tissue chimerism. However, several other possibilities have been proposed to explain these discrepancies (table 1). First, it is possible that, for trans-dedif-ferentiation of HSC to occur, the appropriate tissue damage models are required which are able to create the permissive ‘pro-plastic’ environment enriched in factors needed to promote this process. Hypothetically such a ‘permissive’ environment could induce epigenetic changes in HSC and thus force them to change lineage commitment [28]. To support this, it had been suggested that the genome of stem cells is in an open/accessible status and therefore is more susceptible for potential dedifferentiation events. For example, it had been postulated that HSC expressing mRNA for multiple lineages exist in BM as a continuum and undergo cell cycle-related conversions before being locked into organ-specific fate [29]. Second, it has been reported that some plasticity data could be explained simply by the phenomenon of cell fusion [30]. Accordingly, the donor-derived cells observed in damaged tissues which express non-hematopoietic markers could be in fact heterokaryons, the result of the fusion of BM-derived stem cells with somatic host cells in the damaged organs. Both cell fusion and epigenetic changes, however, are extremely rare and randomly occurring events that certainly could not fully account for all of the positive trans-dedifferentiation data published. Furthermore, fusion as a major contributor to the observed donor-derived chimerism has been excluded in several recently published studies [31]. Another possible explanation of some of the benefits observed in organ/tissue regeneration after infusion of BM-cells is the result of paracrine effects. It is well known that HSC are a source of several trophic cytokines and growth factors and that these factors if released from these cells could promote tissue repair and vascularization [32]. Furthermore, it has been recently shown that cells may transiently modify the phenotype of neighboring cells by transferring surface receptors, intracellular proteins and mRNA in mechanisms that involve exchange of cell membrane-derived microvesicles [33]. Shedding of membrane-derived microvesicles is a physiological phenomenon that accompanies cell growth and cell activation, e.g. hypoxia or oxidative injury [34]. Thus, microvesicle-mediated exchange of receptors, proteins, and mRNA that was demonstrated by us during interaction of embryonic stem cells with HSC [33, 35] takes also place between infused BM cells, and cells in damaged organs could temporarily modify the phenotype of cells in the damaged organ [36, 37].

Table 1.

Alternative explanations of the phenomenon of trans-dedifferentiation or plasticity of HSC

| Epigenetic changes | Factors present in the environment of damaged organs induce epigenetic changes in genes that regulate pluripotency of HSC (involvement of changes in DNA methylation, acetylation of histones). More evidence needed that it is a robust and reproducible phenomenon. |

| Cell fusion | The relatively rare phenomenon by which infused HSC may fuse with cells in damaged tissues and form heterokaryons. Heterokaryons created this way express markers of both donor and recipient cells (pseudochimerism). |

| Paracrine stimulation | HSC are a source of different trophic and angiopoietic factors that may promote tissue/organ repair. |

| Microvesicles-dependent transfer of molecules | Some of the plasticity data could be explained by a transient modification of cell phenotype by the transfer of receptors, proteins and mRNA between HSC and damaged cells by membrane-derived microvesicles. |

| Heterogeneous population of stem cells in BM | In addition to HSC, BM contains other stem cell populations. Regeneration could be explained by the presence of endothelial progenitors that promote neo-vasculogenesis and also by the presence of other stem cells including PSC This could also explain the loss of contribution of BM cells to organ regeneration with use of highly purified populations of HSC. |

Surprisingly, during all of these deliberations concerning stem cell plasticity (table 1) and the potential contribution of BM-derived cells to organ regeneration, the concept that BM may contain heterogeneous populations of stem cells was not taken into careful consideration [24, 38]. We postulate that regeneration studies demonstrating a contribution of donor-derived BM, mPB or CB cells to non-hematopoietic tissues without addressing this possibility (by including the appropriate controls) has led to misleading interpretations. It is reasonable to assume that the presence of heterogeneous populations of stem cells in BM, mPB or CB would be considered before experimental evidence is interpreted as plasticity or trans-differentiation of HSC [39]. Hence the presence of non-hematopoietic stem cells in BM, rather than ‘trans-dedifferentiation’ of HSC, could explain some of the positive results of tissue/organ regeneration as witnessed by several investigators using BM-derived cells [23, 40]. On the other hand, when highly purified HSC were employed for regeneration experiments non-hematopoietic stem cells were likely excluded from these cell preparations. In the current state of knowledge, the phenomenon of trans-dedifferentiation of HSC and their contribution to regeneration of damaged tissues remains questionable.

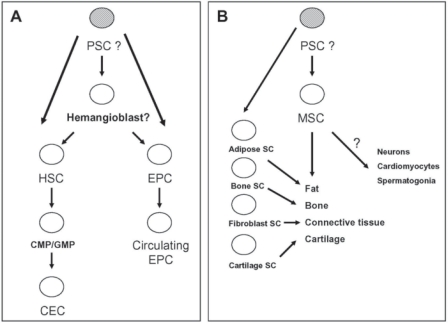

Therefore, the ‘positive’ data supporting stem cell plasticity can be re-interpreted by the assumption that BM-derived stem cells are heterogeneous and that BM tissue contains different types of stem cells, including perhaps a rare population of PSC (fig. 2). The question remains, however, whether these cells can continuously contribute in adult life to the renewal of other stem cells, including the most numerous population of stem cells in BM, HSC. The mechanisms proposed as responsible for the developmental accumulation of stem cells in BM are discussed below.

Fig. 2.

Origin of BM-derived EPC and MSC. A EPC originate in the BM from the hemangioblast or the even more primitive PSC. These rare cells may be released from the BM and circulate in the peripheral blood (circulating EPC). Another fraction of circulating endothelial cells (CEC) derives directly from descendants of HSC which are common myeloid progenitors (CMP) or granulocyto-monocytic progenitors (GMP). B MSC are precursors for fat, bone, connective tissues and cartilage. However, it is very likely that separate monopotent stem cells exist for these tissues. The possibility of trans-differentiation of MSC into neurons, cardiomyocytes and spermatogonia is not clear at this point and requires further studies.

Evidence of the Heterogeneity of Bone Marrow Stem Cells

The concept that BM may contain some non-hematopoietic stem cells has been postulated by several investigators, and, as previously mentioned, the best evidence that BM stem cells are in fact heterogeneous was provided by experiments showing that BM-derived cells could support the regeneration of various tissues/organs [24, 38].

Table 2 lists different types of non-hematopoietic stem cells that have been postulated to reside in BM tissue. These cells will be discussed below and the similarities between these versatile populations of stem cells indicated. It is very likely that several investigators using different isolation strategies described the same populations of stem cells but gave them different names according to circumstance. Some of these cells were described to express transcription factors characteristic for embryonic stem cells such as Oct-4. However, since the normal genome contains several Oct-4 pseudogenes, the real Oct-4 expression and its potential role in adult somatic cells requires further studies [41].

Table 2.

Versatile non-hematopoietic stem cells described in BM

| Stem Cells | Phenotype |

|---|---|

| MSC* | International Society for Cellular Therapy criteria: |

| CD105+, CD73+, CD90+, CD45−, CD34−, CD14−, CDllb−, CD79a−, CD19−, HLA-DR- | |

| Other additional markers: | |

| Stro-1+, SB-10+ (CD166), SH-2+ (epitope on CD105), SH-3+ (epitope on CD73), SH-4+ (epitope on CD73), CD44+, CD29+, CD31−, vWF− | |

| Markers of most primitive MSC: | |

| CXCR4, CD133, CD34 (?), p75LNGFR | |

| MAPC* | SSEA-1+, CD13+, Flk-1low, Thy-1low, CD34−, CD44−, CD45−, CD117 (c-kit)–MHC I-, MHC II- |

| MIAMI cells* | CD29+, CD63+, CD81+, CD122+, CD164+, c-met+, BMPR1B+, NTRK3+, CD34−, CD36−, CD45−, CD117 (c-kit)-, HLA-DR- |

| MACS* | CD13+, CD49b+, CD90+, CD73+, CD44+, CD29+, CD49a+, CD105+, MHC I+, HLA-DR−, CD14−, CD34−, CD45−, CD38−, CD133−, c-kit (CD117)- |

| VSEL stem cells | CXCR4+, AC133+, CD34+, SSEA-1+ (mouse), SSEA-4+ (human), AP+, c-met+, LIF-R+, CD45−, Lin-, HLA-DR-, MHC I-, CD90−, CD29−, CD105− |

AP = Fetal alkaline phosphatase; BMPR1B = bone morphogenetic protein receptor 1B; c-met = receptor for hepatocyte growth factor; LIF-R = receptor for leukemia inhibitory factor; NTRK3 = neurotropic tyrosine kinase receptor 3; vWF = von Willebrand factor.

Phenotype of expanded/cultured adherent cells.

Endothelial Progenitor Cell (EPC)

The identification of BM- and PB-derived cells with endothelial progenitor activities has generated considerable interest in their role during the maintenance and repair of blood vessels [42]. From a historical point of view, the close relationship between hematopoiesis and vasculogenesis was postulated almost 2000 years ago by Aristotle. This Ancient Greek philosopher came to the conclusion based on his empirical work on development that the heart along with blood vessels were the first structures to appear during embryogenesis in eggs from different species. This notion now appears of outstanding significance because it implies that the heart and the blood have a common origin. Translated into today's language, this means that both descend from a common endothelial and hematopoietic progenitor, the putative hemangioblast in the embryonic mesoderm [43]. Hemangioblast activity was demonstrated to exist in embryonic bodies formed by embryonic stem cells in in vitro cultures [44]. However, whether heman-gioblasts persist in adult life and reside in the adult BM is not yet clear [45].

Nevertheless, adult BM-derived cells have been shown to contain endothelial precursors in both mice and humans [1, 42]. The possible place of these cells in the hierarchy of BM-derived stem/progenitor cells and their potential relationship to PSC and hemangioblasts is shown in figure 2, panel A. Accumulating evidence suggests that BM may contain a population of EPC residing in BM tissues that could be released/mobilized into peripheral blood as a source of cells able to play a role in the vascularization of damaged organs [2]. The phenotype of these cells is shown in table 2.

Furthermore, BM was also identified as a source of more differentiated circulating endothelial cells (CEC) [2]. It is not clear whether these cells (fig. 2, panel A) are direct progeny of EPC or can arise from a well-defined population of myeloid lineage-restricted BM progenitors [46]. In support of this latter possibility, a recent report has shown that in fact CEC differentiate both from common myeloid progenitors (CMP) and the more mature granulocyte/macrophage progenitors (GMP) [46]. In addition, endothelial cells derived from transplanted BM-derived myeloid progenitors expressed CD31, von Wille-brand factor and Tie-2 and were CD45− [46, 47]. Thus BM-derived CEC probably reside outside the stem cell population consistent with the hypothesis that CEC arise from differentiated progeny of HSC (fig. 2, panel A).

To summarize, it is postulated that the BM is endowed with neo-angiogenetic activity and BM in steady state is a source of EPC and CEC that subsequently circulate in peripheral blood at very low levels (0.0001% and 0.01%, respectively) and may play a role in the repair of damaged endothelium and contribute to post-natal neo-angiogenesis [48]. While EPC are probably progeny of PSC or perhaps direct descendants of hemangioblasts, the more differentiated CEC originate in the myeloid compartment from a CMP. The level of contribution of BM-derived cells to organ/tissue vascularization, however, still requires further study.

Mesenchymal Stem Cells (Multipotent Mesenchymal Stromal Cells; MSC)

MSC were identified 40 years ago by Friedenstein et al. [49] as a population of BM-derived adherent bone/cartilage-forming progenitor cells. At the same time, it has been known that BM-adherent cells grow colonies of fibroblastic-like cells which have a high replating potential [50]. It was also postulated that among the growing colonies are some progenitor cells that can grow new fibroblastic colonies and such cells were assigned a functional name, colony-forming units of fibroblasts (CFU-F) [51]. If plated at a low density, CFU-F grow distinct colonies of spindle-forming cells, whereas if they are plated at high concentration they rapidly establish confluent cell cultures. Of particular interest, when CFU-F-derived cells are implanted in the sub-renal capsule or are cultured in differentiating media they are able to accumulate lipids or calcium phosphate and grow ectotopic bone fragments. Similarly, when cultured as a bulk mass in the presence of TGF-β they are able to differentiate into chondrocytes [52].

Currently, it is widely accepted that MSC (fig. 2, panel B) contribute to the regeneration of mesenchymal tissues such as bone, cartilage, muscle, ligament, tendon, adipose, and stroma [53]. At this point, however, we cannot exclude the possibility that monopotent stem cells specific for all of these tissues exist (fig. 2, panel B).

MSC are essential in forming the hematopoietic microenvironment in which HSC grow and differentiate [53, 54]. In fact it is well known that fresh passages of unpurified MSC always contain a hidden population of HSC [55]. Thus, in LITCiC assays, BM-derived stroma cells have to be irradiated before the HSC are plated, not only to inhibit the growth of MSC but also to eliminate contaminating HSC which could change conditions for the tested exogenous HSC. However, it is likely that MSC as well as HSC may be contaminated by other populations of primitive non-hematopoietic stem cells. This possibility should be considered whenever a ‘trans-dedifferentiation’ of MSC into cells from other germ layers is demonstrated. Interestingly, MSC engraft very poorly in the BM of recipients of hematopoietic transplants. However, recently a significant degree of chimerism for BM stroma was demonstrated following hematopoietic transplants in pediatric patients [56].

MSC express several surface markers that could be used for their isolation (table 2), including most importantly Stro-1, SB-10, SH-2, SH-3, SH-4, CD44, CD29 and CD90 [57]. They do not express classical hematopoietic (CD34, CD45, CD14) and endothelial markers (CD34, CD31, vWF) [4, 58]. Interestingly some of the MSC were found to express CXCR4 and c-Met receptors and thus may respond to SDF-1 and HGF/SF gradients [59]. The major problem with the exact phenotyping of MSC is the fact that FACS analysis is always performed on MSC expanded ex vivo and not on cells that initiate growth of fibroblastic colonies (CFU-F). Thus, it is not clear if the rare MSC precursor cells initiating the cultures express CD34, CD133 or other primitive markers. Furthermore, since a panel of markers used for MSC purification is not sufficient to distinguish between different subsets of fibroblastic cells isolated from BM, the International Society for Cellular Therapy recently proposed several criteria to characterize better these cells (see below). The finding of populations of CD34+ cells in human BM and murine fetal liver that included CFU-F cells, supported the possibility of existence of such cells [60]. It has also been reported that CD34+ cells are able to establish colonies containing BM fibroblasts and HSC could be the precursors of MSC [61].

Population of MSC derived by culturing of adherent fraction of BM cells remains heterogeneous, and some of the cells are not able to renew CFU-F colonies after re-plating. Two morphologically distinct populations of cells have been described during early passages of low-density plated MSC, including the population of more mature large, flat and slowly replicating cells and the population of smaller, spindle-shaped and rapidly self-renewing cells (RS cells) [62]. Furthermore, serum deprivation of human MSC cultures selects a unique subpopulation of MSC, called serum-deprived MSC (SD-MSC) [63]. SD-MSC are similar in size to RS cells, express mRNA for embryonic markers such as Oct-4, ODC antizyme and hTERT, and proliferate slower than RS cells [63]. It has been suggested that SD-MSC cells are the most primitive fraction of MSC, giving rise into RS cells and more mature populations of MSC. Unfortunately, SD-MSC cells or their precursors have not yet been directly purified and characterized from BM tissue. Thus, there is a difficulty to conclude whether they are derivatives of marrow-derived PSC or a population of MSC that undergoes epigenetic changes due to the serum-deprived in vitro culture conditions. Moreover, the capacity of MSC to differentiate into cells from all three germ layers has been recently described. MSC have been shown to give rise to both neural cells and cardiomyocytes (fig. 2, panel B) [64, 65]. However, further investigations according to the role of various factors used for culture on differentiation of MSC need to be performed. Moreover, the presence of monopotent stem cells committed to various cells lineages, including osteoblasts, in the MSC fraction need to be investigated [57, 66]. The current knowledge about MSC indicates the heterogeneity of these cells and suggests the presence of cells on different levels of commitment and maturation.

Because of various inconsistencies in the field of MSC research, the International Society for Cellular Therapy recently recommended to name MSC as ‘multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells’ instead of ‘mesenchymal stem cell’ [67]. This change in nomenclature is a result of the fact that MSC cultures contain heterogeneous populations of cells, and the majority of fibroblastic cells growing in vitro do not meet the criteria to be identified as stem cells. This name should be reserved for only a very small population of cells, closely related to CFU-F, RS or SD-MSC cells. More importantly, the abbreviation for mesenchymal stromal cells, MSC, however remains the same as for mesenchymal stem cells, allowing for literature searches using both names.

In addition, the Mesenchymal and Tissue Stem Cell Committee of the International Society for Cellular Therapy proposed minimal criteria to define human MSC [68]. First, MSC must be plastic-adherent when maintained in standard culture conditions. Second, MSC must express CD105, CD73 and CD90 and lack expression of CD45, CD34, CD14 or CD11b, CD79alpha or CD19 and HLA-DR surface molecules. Third, MSC must differentiate into osteoblasts, adipocytes and chondroblasts in vitro (fig. 2, panel B). This minimal set of standard criteria should foster a more uniform characterization of MSC and facilitate the exchange of data among investigators [68].

Finally, there are recent reports showing the expression of pluripotent stem cell markers such as Oct-4 and Rex1 or Oct-4 and Nanog by a subpopulation of undifferentiated MSC expanded from BM-adherent cells [69]. The relationship of these undifferentiated MSC with other populations of putative BM-derived PSC requires further investigation. It is very likely that similar/overlapping populations of stem cells were isolated by employing different strategies and hence assigned different names. Of note, MSC so far have not been shown to be able to complete blastocyst development, and thus they do not fulfill the complete criteria for a PSC.

Furthermore, the reported robust contribution of MSC in regeneration of damaged organs in vivo could be explained by the paracrine effects of these cells affecting angiogenesis in damaged tissues rather than by a direct contribution of MSC to supplying tissue-specific functional cells for organ regeneration. Also to be considered is the notion that MSC could serve as scaffolds during regeneration of damaged tissues. Finally, this controversial yet interesting cell type can be successfully employed to modulate graft-versus-host disease and enhance engraftment in patients after hematopoietic transplants [56].

Multipotent Adult Progenitor Cells (MAPC)

MAPC are isolated from BM mononuclear cells as a population of CD45− GPA-A- adherent cells, and they display a similar fibroblastic morphology to MSC [5]. Thus it has been postulated that MAPC could be more primitive cells than MSC; however, the potential relationship between MSC, in particular RS-MSC and SD-MSC, and MAPC has yet to be established.

The colonies of cells enriched in murine MAPC express low levels of FLK-1, Sca-1 and CD90, and higher levels of CD13 and SSEA-1 [5]. They are also negative for the expression of CD34, CD44, CD45, CD117 and MHC class I and class II [5]. The growth of these rare cells depends on selected serum batches and is tightly regulated by oxygen tension. This could explain why several laboratories have had difficulty in establishing cultures of MAPC.

Interestingly MAPC are the only population of BM-derived stem cells that, so far as is known, contribute to all three germ layers after injection into a developing blastocyst, indicating their pluripotency [5]. The contribution of MAPC to blastocyst development, however, requires confirmation by other, independent laboratories.

Marrow-Isolated Adult Multilineage Inducible (MIAMI) Cells

This population of cells has been isolated from human adult BM by culturing BM cells in low oxygen tension conditions on fibronectin [6]. Colonies of small adherent cells were subsequently isolated and further expanded on fibronectin, at low oxygen tension. Cells derived from these cultures expressed CD29, CD63, CD81, CD122, CD164, c-Met, bone morpho-genetic protein receptor IB (BMPR1B) and neutrophic tyrosine kinase receptor 3 (NTKR3), and were negative for CD34, CD36, CD45, CD117 and HLA-DR [70]. Interestingly, these cells also expressed the embryonic stem cell markers Oct-4 and Rex-1. MIAMI cells were isolated from the BM of people with ages ranging between 3 and 72 years. Colonies derived from MIAMI cells expressed several markers for cells from all three germ layers, suggesting that, at least as determined by in vitro assays, they are endowed with pluripotency. However, these cells have not been tested so far for their ability to complete blastocyst development.

The potential relationship of these cells to MSC and MAPC described above is not clear, although it is possible that these are overlapping populations of cells identified by slightly different isolation/expansion strategies. Lending credence to this is the fact that MIAMI cells are derived from a population of BM-adherent cells like MSC or MAPC and can also differentiate into cells that express markers unique to osteoblasts, chondrocytes and adipocytes.

Multipotent Adult Stem Cells (MACS).

These cells express pluripotent-state-specific transcription factors (Oct-4, Nanog and Rex1) and were cloned from human liver, heart, and BM-isolated mononuclear cells [7]. MACS display a high telomerase activity and exhibit a wide range of differentiation potential. Again the potential relationship of these cells to MSC, MAPC and MIAMI cells described above is not clear, although it is possible that these are overlapping populations of cells identified by slightly different isolation/expansion strategies. The phenotype of these cells is shown in table 2.

Very Small Embryonic-Like (VSEL) Stem Cells

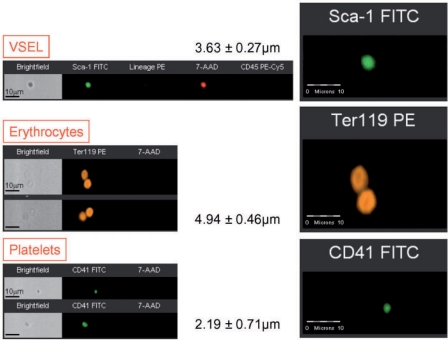

Recently a homogenous population of rare (∼0.01% of BM mononuclear cells) Sca-1+ lin− CD45− cells was identified in murine BM. They express (as determined by RQ-PCR and immunhistochemistry) markers of PSC such as SSEA-1, Oct-4, Nanog and Rex-1 and Rif-1 telomerase protein [8]. Of note, we employed Oct-4 specific primers that do not amplify Oct-4 pseudogenes [41]. Direct electron microscopical analysis revealed that these cells display several features typical for embryonic stem cells such as i) a small size (∼3.5 μm in diameter), ii) a large nucleus surrounded by a narrow rim of cytoplasm, and iii) open-type chromatin (euchromatin). We also employed ImageStream system (ISS) analysis to evaluate better VSEL stem cells. This technology was developed as a novel method for multiparameter cell analysis and as a supportive tool for flow cytometry. ISS integrates the features of flow cytometry and fluorescent microscopy collecting images of acquired cells for offline digital image analysis [71, 72]. Analysis employing ISS system confirmed a very small size of VSEL stem cells as well as other features related to their primitivity such as high nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio [73]. VSEL stem cells are smaller than erythrocytes and larger than the majority of platelets, as shown in figure 3. They can be distinguished from large platelets not only based on different surface markers but also because they contain nuclei (fig. 3). Interestingly, VSEL stem cells, despite their small size, posses diploid DNA and contain numerous mitochondria. They do not express MHC-1 and HLA-DR antigens and are CD90− CD105− CD29-. For the first time a sorting procedure have been described that indicates how to purify from adult BM a distinct population of very primitive embryonic-like stem cells and, more importantly, the morphology and the surface markers of these rare cells at the single cell level [73, 74].

Fig. 3.

Morphological comparison between murine VSEL stem cells, erythrocytes and platelets by ImageStream system. Murine VSEL stem cells were stained for Sca-1 (FITC, green), lineage markers (PE, orange) and CD45 (PE-Cy5, magenta). Murine erythrocytes were stained for Ter119 (PE, orange), while murine platelets for CD41 (FITC, green). Following fixation, all samples were stained with 7-aminiactinomycin D (7-AAD, red) to visualize nuclei. Erythrocytes and platelets do not possess nuclei, while VSEL stem cells show cellular structure containing nuclei. Average size of each population is shown (mean ± SEM).

Moreover, it is possible that these VSEL stem cells may be released from BM and circulate in blood during tissue/organ injury (e.g. heart infarct and stroke). Interestingly ∼5–10% of purified VSEL stem cells if plated over a C2C12 murine sarcoma cell feeder layer are able to form spheres that resemble embryoid bodies. Cells from these VSEL stem cell-derived spheres (VSEL-DS) are composed of immature cells with large nuclei containing euchromatin and, like purified VSELs, are CXCR4+ SSEA-1+ Oct-4+.

Furthermore, VSEL-DS, after re-plating over C2C12 cells, may again (up to 5–7 passages) grow new spheres or, if plated into cultures promoting tissue differentiation, expand into cells from all three germ cell layers. Since VSEL stem cells isolated from GFP+ mice grew GFP+ VSEL-DS showing a diploid content of DNA, this confirms that VSEL-DS are derived from VSEL stem cells, and not from the supportive C2C12 cell line, as well as excludes the possibility of cell fusion. Similar spheres were also formed by VSEL stem cells isolated from murine fetal liver, spleen, and thymus. Interestingly, formation of VSEL-DS was associated with a young age in mice, and no VSEL-DS were observed in cells isolated from old mice (>2 years) [8, 39]. This age-dependent content of VSEL stem cells in BM may explain why the regeneration processes is more efficient in younger individuals. There are also differences in the content of these cells among BM mononuclear cells between long- and short-lived mouse strains. The concentration of these cells is much higher in BM of long-lived (e.g. C57B16) as compared to short-lived (DBA/2J) mice [39]. It would be interesting to identify genes that are responsible for tissue distribution/expansion of these cells as they could be involved in controlling the life span of mammals.

Since VSEL stem cells express several markers of primordial germ cells (fetal-type alkaline phosphatase, Oct-4, SSEA-1, CXCR4, Mvh, Stella, Fragilis, Nobox, Hdac6), they could be closely related to a population of epiblast-derived primordial germ cells. VSEL stem cells are also highly mobile and respond robustly to an SDF-1 gradient, adhere to fibronectin and fibrinogen, and may interact with BM-derived stromal fibroblasts. Confocal microscopy and time-lapse studies revealed that these cells attach rapidly to, migrate beneath, and undergo emperipolesis in marrow-derived fibroblasts [39]. Since fibroblasts secrete SDF-1 and other chemottractants, they may create a homing environment for small CXCR4− VSEL stem cells. This robust interaction of VSEL stem cells with BM-derived fibroblasts has an important implication, namely that isolated BM stromal cells may be contaminated by these tiny cells from the beginning. This observation may explain the unexpected ‘plasticity’ of marrow-derived fibroblastic cells (e.g. MSC or MAPC).

Recently, a very similar population of cells that show similar morphology and markers to murine BM-derived VSEL stem cells was purified from human CB [75]. Evidence has also mounted that similar cells are also present in the human BM, in particular in young patients. It is anticipated that VSEL stem cells could become an important source of PSC for regeneration. At this point, however, it is not clear whether VSEL stem cells contribute to the blactocyst development.

Bone Marrow-Derived Oocytes and Spermatogonia?

Recently somewhat unexpectedly BM was also identified as a source of oocyte-like and spermatogonia-like cells [9, 10]. The presence of functional oocyte precursors in BM, however, recently became somewhat controversial after recent parabiotic experiments excluded BM as a source of oocytes in normal steady state conditions [76].

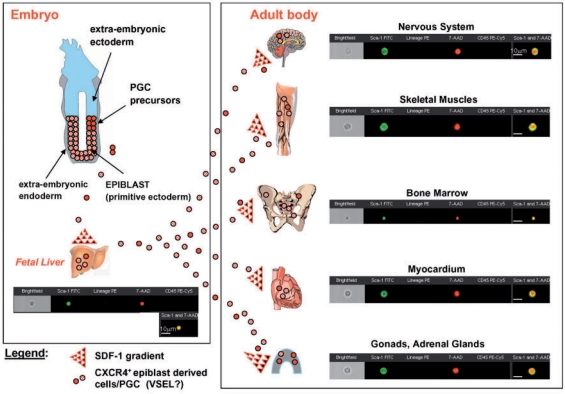

The presence of primitive germ cells supports to some extent the concept that during embryonic development some of the primordial germ cells may go astray on their way to the genital ridges and colonize fetal liver, and subsequently by the end of the second trimester of gestation, together with fetal liver-derived HSC move to the BM tissue (fig. 4). We hypothesize that also VSEL stem cell population migrates during development and can be potentially deposited in various tissues. The examples of cells with VSEL stem cell phenotype in several organs, including fetal liver, adult bone marrow, brain, skeletal and heart muscles as well as testis, is shown in figure 4.

Fig. 4.

Hypothesis of developmental deposition of Oct-4+ epiblast-derived embryonic stem cells (VSEL stem cells?) in adult tissues. The presence of Oct-4+ stem cells in the fetal liver, BM and other tissues could be explained by the developmental deposition in different organs (mainly BM) of CXCR4+ epiblast-derived stem cells (e.g., VSEL stem cells) that follow an SDF-1 gradient. The potential relationship of these cells to early epiblast/primordial germ cells requires further investigation. The images of Sca-1+ lin− CD45− cells analyzed from various organs by ImageS tream system are shown as examples. Cells were stained for Sca-1 (FITC, green), lineage markers (PE, orange) and CD45 (PE-Cy5, magenta). Nuclei were stained with 7-aminiactinomycin D (7-AAD, red) following fixation.

All Roads Lead to the Pluripotent Stem Cell – Does It Really Exist in Bone Marrow?

Above we discussed several types of non-hematopoietic stem cells that have been identified so far in the BM. An important question remains, however: whether a PSC, a founder cell for cells forming all three germ layers, resides in the adult BM. Several lines of evidence support the presence of PSC in BM tissue. First, expression of typical PSC markers such as SSEA-1, Oct-4 and Nanog was reported in BM-derived stem cells isolated using various strategies. These early embryonic transcription factors that are characteristic for embryonic stem cells and epiblast-derived cells were demonstrated at the protein and/or mRNA levels in VSEL stem cells, MAPC, MSC (in particular the SD fraction) and MIAMI cells [5, 6, 8, 63, 69]. Second, the contribution of BM-derived cells to regeneration of multiple non-hematopoietic organs and tissues indirectly suggests the existence of pluripotent or multipotent stem cells in BM. Illustrating this are experiments performed at the single cell level with BM-derived stem cells (Fr25 Sca-1+ Kit+ Lin- or Fr25SKL cell) that contributed to multiorgan, multi-lineage engraftment in lethally irradiated mice [77]. These cells were first fractionated by elutriation at a flow rate of 25 ml/min (Fr25), then lineage depleted (lin-) and labeled with cell membrane-marking fluorochrome (PKH26) and injected intravenously into lethally irradiated animals. Two days post transplant PKH26+ cells were recovered by flow cytometric sorting of recipient BM. These single adult BM-derived Fr25SKL cells have a robust capacity to differentiate into epithelial cells of the liver, lung, gastrointestinal tract (endoderm) and skin (ectoderm) [77].

Nevertheless, several questions relating to the presence of a putative PSC in BM remain. First, it is important to elucidate if this cell is merely a remnant from developmental embryogenesis that resides in a dormant state in the BM tissue or if it is a rare but mitotically active cell that contributes to the renewal of the pool of other BM-residing stem cells including HSC, EPC and MSC. Second, what is the relationship of this cell related to the cells recently described and purified from BM: i) SSEA-1+ Oct-4+ Nanog+ VSEL stem cells, ii) small Oct-4+ MAPC, iii) Oct-4+ SD-fraction of MSC, and iv) Oct-4+ MIAMI cells? As mentioned before, it is likely that all of these versatile BM-derived Oct-4+ non-hematopoietic stem cells, which were given different operational names, are in fact very closely related to the same type of BM-residing PSC.

As shown in figure 4, it is possible that these BM-residing PSC, as remnants of embryonic development (e.g. derivatives from the epiblast), reside in a dormant state in ectotopic BM niches. The dormant status of these cells could be the result of the fact that these cells are i) located in a non-physiological niche, ii) exposed to inhibitors, iii) deprived of some appropriate stimulatory signals, and finally iv) limited in pluripotency because of the erasure of the somatic imprint on some of the crucial somatically imprinted genes (e.g. H19 and IGF2). These cells, however, could be activated if they are exposed to some appropriate activation signals (e.g. upregulated during organ/tissue injury, oncogenesis) or undergo epigenetic changes that change the methylation status of their DNA and acetylation of histones. Finally they may be reactivated if a proper somatic imprint is re-established (fig. 3) [78].

In summary, there is mounting evidence that BM in fact contains PSC. For example, BM contains a population of VSEL stem cells that express SSEA-1 Oct-4 Nanog and are lin-CD45− [8]. These cells display a very primitive morphology and as shown at the single cell level are able in in vitro cultures to differentiate into cells from all three germ layers. Furthermore, Oct-4 and Nanog are also expressed in small MAPC, SD-MSC and MIAMI cells [6, 63].

The most convincing evidence for the pluripotency of BM-derived stem cells would be the demonstration that these cells can complement blastocyst development after injection into a developing blastocyst. Unfortunately, such evidence for pluripotency has so far not been achieved in a reproducible way with any of the BM-derived stem cells.

Bone Marrow-Derived Non-Hematopoietic Stem Cells and Regenerative Medicine?

Humanity continually searches for the holy grail of an end to the suffering caused by illness, and a better quality of life in advancing years. There is no doubt that medical science is now looking to stem cells to provide some of milestones in this important quest. Adult BM stem cells could potentially provide a real therapeutic alternative to the controversial use of human embryonic stem cells and therapeutic cloning. However, it is still unclear whether BM contains a PSC. Several attempts have been made to identify such a cell in the BM that at the single cell level in vitro could give rise to cells from all three germ layers (meso-, ecto- and endoderm). However, the most valuable evidence for pluripotentiality of the stem cell is its contribution to the development of multiple organs and tissues in vivo after injection into the developing blastocyst, and this evidence is missing.

Nevertheless, while the ethical debate on the application of embryonic stem cells in therapy continues, the potential of BM-derived non-hematopoietic stem cells is ripe for exploration. The coming years will bring important answers to these question.

Acknowledgments

Supported by NIH grant R01 CA106281-01 to MZR.

References

- 1.Asahara T, Murohara T, Sullivan A, Silver M, van der Zee R, Li T, Witzenbichler B, Schatteman G, Isner JM. Isolation of putative progenitor endothelial cells for angiogenesis. Science. 1997;275:964–967. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5302.964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Shi Q, Rafii S, Wu MH, Wijelath ES, Yu C, Ishida A, Fujita Y, Kothari S, Mohle R, Sauvage LR, Moore MA, Storb RF, Hammond WP. Evidence for circulating bone marrow-derived endothelial cells. Blood. 1998;92:362–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peister A, Mellad JA, Larson BL, Hall BM, Gibson LF, Prockop DJ. Adult stem cells from bone marrow (MSCs) isolated from different strains of inbred mice vary in surface epitopes, rates of proliferation, and differentiation potential. Blood. 2004;103:1662–1668. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prockop DJ. Marrow stromal cells as stem cells for nonhematopoietic tissues. Science. 1997;276:71–74. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5309.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jiang Y, Jahagirdar BN, Reinhardt RL, Schwartz RE, Keene CD, Ortiz-Gonzalez XR, Reyes M, Lenvik T, Lund T, Blackstad M, Du J, Aldrich S, Lisberg A, Low WC, Largaespada DA, Verfaillie CM. Pluripotency of mesenchymal stem cells derived from adult marrow. Nature. 2002;418:41–49. doi: 10.1038/nature00870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.D'Ippolito G, Diabira S, Howard GA, Menei P, Roos BA, Schiller PC. Marrow-isolated adult multi-lineage inducible (MIAMI) cells, a unique population of postnatal young and old human cells with extensive expansion and differentiation potential. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:2971–2981. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beltrami AP, Cesselli D, Bergamin N, Marcon P, Rigo S, Puppato E, D'Aurizio F, Verardo R, Piazza S, Pignatelli A, Poz A, Baccarani U, Damiani D, Fanin R, Mariuzzi L, Finato N, Masolini P, Burelli S, Belluzzi O, Schneider C, Beltrami CA. Multipotent cells can be generated in vitro from several adult human organs (heart, liver and bone marrow) Blood. 2007;110:3438–3446. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kucia M, Reca R, Campbell FR, Zuba-Surma E, Majka M, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. A population of very small embryonic-like (VSEL) CXCR4(+) SSEA-1(+)Oct-4+ stem cells identified in adult bone marrow. Leukemia. 2006;20:857–869. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Johnson J, Bagley J, Skaznik-Wikiel M, Lee HJ, Adams GB, Niikura Y, Tschudy KS, Tilly JC, Cortes ML, Forkert R, Spitzer T, Iacomini J, Scadden DT, Tilly JL. Oocyte generation in adult mammalian ovaries by putative germ cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood. Cell. 2005;122:303–315. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nayernia K, Lee JH, Drusenheimer N, Nolte J, Wulf G, Dressel R, Gromoll J, Engel W. Derivation of male germ cells from bone marrow stem cells. Lab Invest. 2006;86:654–663. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nagasawa T. A chemokine, SDF-1/PBSF, and its receptor, CXC chemokine receptor 4, as mediators of hematopoiesis. Int J Hematol. 2000;72:408–411. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kollet O, Shivtiel S, Chen YQ, Suriawinata J, Thung SN, Dabeva MD, Kahn J, Spiegel A, Dar A, Samira S, Goichberg P, Kalinkovich A, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Nagler A, Hardan I, Revel M, Shafritz DA, Lapidot T. HGF, SDF-1, and MMP-9 are involved in stress-induced human CD34+ stem cell recruitment to the liver. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:160–169. doi: 10.1172/JCI17902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kucia M, Dawn B, Hunt G, Guo Y, Wysoczynski M, Majka M, Ratajczak J, Rezzoug F, Ildstad ST, Bolli R, Ratajczak MZ. Cells expressing early cardiac markers reside in the bone marrow and are mobilized into the peripheral blood after myocardial infarction. Circ Res. 2004;95:1191–1199. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150856.47324.5b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kucia M, Zhang YP, Reca R, Wysoczynski M, Machalinski B, Majka M, Ildstad ST, Ratajczak J, Shields CB, Ratajczak MZ. Cells enriched in markers of neural tissue-committed stem cells reside in the bone marrow and are mobilized into the peripheral blood following stroke. Leukemia. 2006;20:18–28. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kucia M, Wojakowski W, Reca R, Machalinski B, Gozdzik J, Majka M, Baran J, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. The migration of bone marrow-derived non-hematopoietic tissue-committed stem cells is regulated in an SDF-1-, HGF-, and LIF-dependent manner. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2006;54:121–135. doi: 10.1007/s00005-006-0015-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kucia M, Zuba-Surma E, Wysoczynski M, Dobrowolska H, Reca R, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Physiological and pathological consequences of identification of very small embryonic like (VSEL) stem cells in adult bone marrow. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2006;57:5–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Campli C, Piscaglia AC, Pierelli L, Rutella S, Bonanno G, Alison MR, Mariotti A, Vecchio FM, Nestola M, Monego G, Michetti F, Mancuso S, Pola P, Leone G, Gasbarrini G, Gasbarrini A. A human umbilical cord stem cell rescue therapy in a murine model of toxic liver injury. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:603–613. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2004.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Orlic D, Kajstura J, Chimenti S, Jakoniuk I, Anderson SM, Li B, Pickel J, McKay R, Nadal-Ginard B, Bodine DM, Leri A, Anversa P. Bone marrow cells regenerate infarcted myocardium. Nature. 2001;410:701–705. doi: 10.1038/35070587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lagasse E, Connors H, Al-Dhalimy M, Reitsma M, Dohse M, Osborne L, Wang X, Finegold M, Weissman IL, Grompe M. Purified hematopoietic stem cells can differentiate into hepatocytes in vivo. Nat Med. 2000;6:1229–1234. doi: 10.1038/81326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mezey E, Chandross KJ, Harta G, Maki RA, McKercher SR. Turning blood into brain: cells bearing neuronal antigens generated in vivo from bone marrow. Science. 2000;290:1779–1782. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5497.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hess DC, Abe T, Hill WD, Studdard AM, Carothers J, Masuya M, Fleming PA, Drake CJ, Ogawa M. Hematopoietic origin of microglial and perivascular cells in brain. Exp Neurol. 2004;186:134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2003.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Corti S, Locatelli F, Donadoni C, Strazzer S, Salani S, Del Bo R, Caccialanza M, Bresolin N, Scarlato G, Comi GP. Neuroectodermal and microghal differentiation of bone marrow cells in the mouse spinal cord and sensory ganglia. J Neurosci Res. 2002;70:721–733. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Petersen BE, Bowen WC, Patrene KD, Mars WM, Sullivan AK, Murase N, Boggs SS, Greenberger JS, Goff JP. Bone marrow as a potential source of hepatic oval cells. Science. 1999;284:1168–1170. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5417.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orkin SH, Zon LI. Hematopoiesis and stem cells: plasticity versus developmental heterogeneity. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:323–328. doi: 10.1038/ni0402-323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wagers AJ, Sherwood RI, Christensen JL, Weissman IL. Little evidence for developmental plasticity of adult hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2002;297:2256–2259. doi: 10.1126/science.1074807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Murry CE, Soonpaa MH, Reinecke H, Nakajima H, Nakajima HO, Rubart M, Pasumarthi KB, Virag JI, Bartelmez SH, Poppa V, Bradford G, Dowell JD, Williams DA, Field LJ. Haematopoietic stem cells do not transdifferentiate into cardiac myocytes in myocardial infarcts. Nature. 2004;428:664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature02446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Castro RF, Jackson KA, Goodell MA, Robertson CS, Liu H, Shine HD. Failure of bone marrow cells to transdifferentiate into neural cells in vivo. Science. 2002;297:1299. doi: 10.1126/science.297.5585.1299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morshead CM, Benveniste P, Iscove NN, van der Kooy D. Hematopoietic competence is a rare property of neural stem cells that may depend on genetic and epigenetic alterations. Nat Med. 2002;8:268–273. doi: 10.1038/nm0302-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quesenberry PJ, Colvin G, Dooner G, Dooner M, Aliotta JM, Johnson K. The stem cell continuum: cell cycle, injury, and phenotype lability. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1106:20–29. doi: 10.1196/annals.1392.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Terada N, Hamazaki T, Oka M, Hoki M, Mastalerz DM, Nakano Y, Meyer EM, Morel L, Petersen BE, Scott EW. Bone marrow cells adopt the phenotype of other cells by spontaneous cell fusion. Nature. 2002;416:542–545. doi: 10.1038/nature730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harris RG, Herzog EL, Bruscia EM, Grove JE, Van Arnam JS, Krause DS. Lack of a fusion requirement for development of bone marrow-derived epithelia. Science. 2004;305:90–93. doi: 10.1126/science.1098925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rafii S, Lyden D. Therapeutic stem and progenitor cell transplantation for organ vascularization and regeneration. Nat Med. 2003;9:702–712. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ratajczak J, Miekus K, Kucia M, Zhang J, Reca R, Dvorak P, Ratajczak MZ. Embryonic stem cell-derived microvesicles reprogram hematopoietic progenitors: evidence for horizontal transfer of mRNA and protein delivery. Leukemia. 2006;20:847–856. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Morel O, Toti F, Hugel B, Freyssinet JM. Cellular microparticles: a disseminated storage pool of bioactive vascular effectors. Curr Opin Hematol. 2004;11:156–164. doi: 10.1097/01.moh.0000131441.10020.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ratajczak J, Wysoczynski M, Hayek F, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak MZ. Membrane-derived microvesicles: important and underappreciated mediators of cell-to-cell communication. Leukemia. 2006;20:1487–1495. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aliotta JM, Sanchez-Guijo FM, Dooner GJ, Johnson KW, Dooner MS, Greer KA, Greer D, Pimentel J, Kolankiewicz LM, Puente N, Faradyan S, Ferland P, Bearer EL, Passero MA, Adedi M, Colvin GA, Quesenberry PJ. Alteration of marrow cell gene expression, protein production, and engraftment into lung by lung-derived microvesicles: a novel mechanism for phenotype modulation. Stem Cells. 2007;25:2245–2256. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deregibus MC, Cantaluppi V, Calogero R, Lo Iacono M, Tetta C, Biancone L, Bruno S, Bussolati B, Camussi G. Endothelial progenitor cell derived microvesicles activate an angiogenic program in endothelial cells by a horizontal transfer of mRNA. Blood. 2007;110:2440–2448. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-03-078709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ratajczak MZ, Kucia M, Reca R, Majka M, Janowska-Wieczorek A, Ratajczak J. Stem cell plasticity revisited: CXCR4-positive cells expressing mRNA for early muscle, liver and neural cells ‘hide out’ in the bone marrow. Leukemia. 2004;18:29–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kucia M, Reca R, Jala VR, Dawn B, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Bone marrow as a home of heterogenous populations of nonhematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2005;19:1118–1127. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kucia M, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ. Are bone marrow stem cells plastic or heterogenous-that is the question. Exp Hematol. 2005;33:613–623. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2005.01.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lengner CJ, Camargo FD, Hochedlinger K, Welstead GG, Zaidi S, Gokhale S, Scholer HR, Tomilin A, Jaenisch R. Oct4 expression is not required for mouse somatic stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell. 2007;1:403–415. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2007.07.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Asahara T, Masuda H, Takahashi T, Kalka C, Pastore C, Silver M, Kearne M, Magner M, Isner JM. Bone marrow origin of endothelial progenitor cells responsible for postnatal vasculogenesis in physiological and pathological neovascularization. Circ Res. 1999;85:221–228. doi: 10.1161/01.res.85.3.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Choi K, Kennedy M, Kazarov A, Papadimitriou JC, Keller G. A common precursor for hematopoietic and endothelial cells. Development. 1998;125:725–732. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.4.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lacaud G, Robertson S, Palis J, Kennedy M, Keller G. Regulation of hemangioblast development. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;938:96–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb03578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pelosi E, Valtieri M, Coppola S, Botta R, Gabbianelli M, Lulli V, Marziali G, Masella B, Müller R, Sgadari C, Testa U, Bonanno G, Peschle C. Identification of the hemangioblast in postnatal life. Blood. 2002;100:3203–3208. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-05-1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bailey AS, Willenbring H, Jiang S, Anderson DA, Schroeder DA, Wong MH, Grompe M, Fleming WH. Myeloid lineage progenitors give rise to vascular endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:13156–13161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604203103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bailey AS, Jiang S, Afentoulis M, Baumann CI, Schroeder DA, Olson SB, Wong MH, Fleming WH. Transplanted adult hematopoietic stems cells differentiate into functional endothelial cells. Blood. 2004;103:13–19. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-05-1684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ingram DA, Caplice NM, Yoder MC. Unresolved questions, changing definitions, and novel paradigms for defining endothelial progenitor cells. Blood. 2005;106:1525–1531. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Friedenstein AJ, Piatetzky-Shapiro II, Petrakova KV. Osteogenesis in transplants of bone marrow cells. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1966;16:381–390. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedenstein AJ, Petrakova KV, Kurolesova AI, Frolova GP. Heterotopic of bone marrow. Analysis of precursor cells for osteogenic and hematopoietic tissues. Transplantation. 1968;6:230–247. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Friedenstein AJ, Deriglasova UF, Kulagina NN, Panasuk AF, Rudakowa SF, Luriá EA, Ruadkow IA. Precursors for fibroblasts in different populations of hematopoietic cells as detected by the in vitro colony assay method. Exp Hematol. 1974;2:83–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackay AM, Bec kSC, Murphy JM, Barry FP, Chichester CO, Pittenger MF. Chondrogenic differentiation of cultured human mesenchymal stem cells from marrow. Tissue Eng. 1998;4:415–428. doi: 10.1089/ten.1998.4.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pittenger MF, Mackay AM, Beck SC, Jaiswal RK, Douglas R, Mosca JD, Moorman MA, Simonetti DW, Craig S, Marshak DR. Multilineage potential of adult human mesenchymal stem cells. Science. 1999;284:143–147. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dexter TM, Spooncer E. Growth and differentiation in the hemopoietic system. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1987:3. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.03.110187.002231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Phinney DG, Kopen G, Righter W, Webster S, Tremain N, Prockop DJ. Donor variation in the growth properties and osteogenic potential of human marrow stromal cells. J Cell Biochem. 1999;75:424–436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pozzi S, Lisini D, Podestà M, Bernardo ME, Sessareg N, Piaggio G, Cometa A, Giorgiani G, Mina T, Buldini B, Maccario R, Frassoni F, Locatelli F. Donor multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells may engraft in pediatric patients given either cord blood or bone marrow transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:934–942. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kemp KC, Hows J, Donaldson C. Bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Leuk Lymphoma. 2005;46:1531–1544. doi: 10.1080/10428190500215076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van den Heuvel RL, Versele SR, Schoeters GE, Vanderborght OL. Stromal stem cells (CFU-f) in yolk sac, liver, spleen and bone marrow of pre- and postnatal mice. Br J Haematol. 1987;66:15–20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1987.tb06884.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Son BR, Marquez-Curtis LA, Kucia M, Wysoczynski M, Turner AR, Ratajczak J, Ratajczak MZ, Janowska-Wieczorek A. Migration of bone marrow and cord blood mesenchymal stem cells in vitro is regulated by stromal-derived factor-1-CXCR4 and hepatocyte growth factor-c-met axes and involves matrix metalloproteinases. Stem Cells. 2006;24:1254–1264. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2005-0271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Waller EK, Olweus J, Lund-Johansen F, Huang S, Nguyen M, Guo GR, Terstappen L. The ‘common stem cell’ hypothesis reevaluated: human fetal bone marrow contains separate populations of hematopoietic and stromal progenitors. Blood. 1995;85:2422–2435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ogawa M, LaRue AC, Drake CJ. Hematopoietic origin of fibroblasts/myofibroblasts: its pathophysiologic implications. Blood. 2006;108:2893–2896. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-016600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Colter DC, Sekiya I, Prockop DJ. Identification of a subpopulation of rapidly self-renewing and multi-potential adult stem cells in colonies of human marrow stromal cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7841–7845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141221698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Pochampally RR, Smith JR, Ylostalo J, Prockop DJ. Serum deprivation of human marrow stromal cells (hMSCs) selects for a subpopulation of early progenitor cells with enhanced expression of OCT-4 and other embryonic genes. Blood. 2004;103:1647–1652. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jiang Y, Henderson D, Blackstad M, Chen A, Miller RF, Verfaillie CM. Neuroectodermal differentiation from mouse multipotent adult progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:11854–11860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834196100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Toma C, Pittenger MF, Cahill KS, Byrne BJ, Kessler PD. Human mesenchymal stem cells differentiate to a cardiomyocyte phenotype in the adult murine heart. Circulation. 2002;105:93–98. doi: 10.1161/hc0102.101442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dominici M, Pritchard C, Garlits JE, Hofmann TJ, Persons DA, Horwitz EM. Hematopoietic cells and osteoblasts are derived from a common marrow progenitor after bone marrow transplantation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:11761–11766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404626101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Horwitz EM, Le Blanc K, Dominici M, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini FC, Deans RJ, Krause DS, Keating A. Therapy, for the International Society for Cellular Therapy: Clarification of the nomenclature for MSC: The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2005;7:393–395. doi: 10.1080/14653240500319234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dominici M, Le Blanc K, Mueller I, Slaper-Cortenbach I, Marini F, Krause D, Deans R, Keating A, Prockop DJ, Horwitz E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:315–317. doi: 10.1080/14653240600855905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lamoury FM, Croitoru-Lamoury J, Brew BJ. Un-differentiated mouse mesenchymal stem cells spontaneously express neural and stem cell markers Oct-4 and Rex-1. Cytotherapy. 2006;8:228–242. doi: 10.1080/14653240600735875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.D'Ippolito G, Howard GA, Roos BA, Schiller PC. Isolation and characterization of marrow-isolated adult multilineage inducible (MIAMI) cells. Exp Hematol. 2006;34:1608–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zuba-Surma EK, Kucia M, Abdel-Latif A, Lillard JJ, Ratajczak MZ. The ImageStream system: a key step to a new era in imaging. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2007;45:279–290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zuba-Surma EK, Kucia M, Ratajczak MZ. ‘Decoding the Dots’: The ImageStream system (ISS) as a new and powerful tool for flow cytometric analysis. CEJB. 2008;3:1–10. DOI: 0.2478/s 11535-007-0044-8. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zuba-Surma EK, Kucia M, Abdel-Latif A, Dawn B, Hall B, Singh R, Lillard JW, Jr, Ratajczak MZ. Morphological characterization of Very Small Embryonic-Like stem cells (VSELs) by ImageStream system analysis. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00154.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ratajczak MZ, Zuba-Surma EK, Machalinski B, Kucia M. Bone-marrow-derived stem cells – our key to longevity? J Appl Genet. 2007;48:307–319. doi: 10.1007/BF03195227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kucia M, Halasa M, Wysoczynski M, Baskiewicz-Masiuk M, Moldenhawer S, Zuba-Surma E, Czajka R, Wojakowski W, Machalinski B, Ratajczak MZ. Morphological and molecular characterization of novel population of CXCR4(+) SSEA-4(+) Oct-4(+) very small embryonic-like cells purified from human cord blood – preliminary report. Leukemia. 2007;21:297–303. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Eggan K, Jurga S, Gosden R, Min IM, Wagers AJ. Ovulated oocytes in adult mice derive from non-circulating germ cells. Nature. 2006;441:1109–1114. doi: 10.1038/nature04929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krause DS, Theise ND, Collector MI, Henegariu O, Hwang S, Gardner R, Neutzel S, Sharkis SJ. Multi-organ, multi-lineage engraftment by a single bone marrow-derived stem cell. Cell. 2001;105:369–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00328-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ratajczak MZ, Machalinski B, Wojakowski W, Ratajczak J, Kucia M. A hypothesis for an embryonic origin of pluripotent Oct-4+ stem cells in adult bone marrow and other tissues. Leukemia. 2007;21:860–867. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]