Abstract

More than any other cytokine family, the IL-1 family of ligands and receptors is primarily associated with acute and chronic inflammation. The cytosolic segment of each IL-1 receptor family member contains the Toll-IL-1-receptor domain. This domain is also present in each Toll-like receptor, the receptors that respond to microbial products and viruses. Since Toll-IL-1-receptor domains are functional for both receptor families, responses to the IL-1 family are fundamental to innate immunity. Of the 11 members of the IL-1 family, IL-1β has emerged as a therapeutic target for an expanding number of systemic and local inflammatory conditions called autoinflammatory diseases. For these, neutralization of IL-1β results in a rapid and sustained reduction in disease severity. Treatment for autoimmune diseases often includes immunosuppressive drugs whereas neutralization of IL-1β is mostly anti-inflammatory. Although some autoinflammatory diseases are due to gain-of-function mutations for caspase-1 activity, common diseases such as gout, type 2 diabetes, heart failure, recurrent pericarditis, rheumatoid arthritis, and smoldering myeloma also are responsive to IL-1β neutralization. This review summarizes acute and chronic inflammatory diseases that are treated by reducing IL-1β activity and proposes that disease severity is affected by the anti-inflammatory members of the IL-1 family of ligands and receptors.

Introduction

Since the 1996 publication in Blood of “Biologic Basis for Interleukin-1 in Disease,”1 there have been several major advances in understanding a role for IL-1 in the pathogenesis of disease. Because of its property as a hematopoietic factor, IL-1 was administered to patients to improve recovery after BM transplantation (human responses to IL-1 were reviewed in detail in 1996).1 Effective in reducing the duration of thrombocytopenia and leukopenia, recipients of IL-1 therapy experienced unacceptable signs and symptoms of systemic inflammation, including hypotension. Therefore, attention was initially focused on blocking IL-1 activity in sepsis with the use of the naturally occurring IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1Ra), now known by its generic name anakinra. There were 3 controlled trials of anakinra in human sepsis. Although in each trial there was a reduction in 28-day all-causes mortality compared with placebo-treated patients, the reductions did not reach statistical significance.2 The failure of blocking IL-1 to significantly reduce mortality in septic shock is not unusual, because most anticytokines and anti-inflammatory agents have also failed in sepsis trials (reviewed in Eichacker et al3).

Subsequently, attention focused on blocking IL-1 in noninfectious, chronic inflammatory conditions, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Anakinra is approved for reducing the signs and symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis and slows the progressive joint destructive characteristics of the disease. Anakinra has also been administered to patients with smoldering/indolent myeloma at high risk of progression to multiple myeloma. In combination with a weekly low dose of dexamethasone, anakinra treatment provided a significant increase in the number of years of progression-free disease.4 Consistently, there are no organ toxicities or gastrointestinal disturbances with anakinra or other parenteral therapies to reduce IL-1 activity. Blocking IL-1, particularly IL-1β, is now the standard of therapy for a class of inflammatory syndromes termed “autoinflammatory” diseases (reviewed by Simon and van der Meer5 and Masters et al6). Autoinflammatory syndromes are distinct from autoimmune diseases. In autoimmune diseases, the T cell is associated with pathogenesis as the dysfunctional cell or “driver” of inflammation. Immunosuppressive therapies targeting T-cell function as well as antibodies that deplete T and B cells are effective in treating autoimmune diseases. In contrast, in autoinflammatory diseases, the monocyte-macrophage is the dysfunctional cell, which directly promotes inflammation. Autoinflammatory conditions are characterized by recurrent bouts of fever with debilitating local and systemic inflammation; they are often responsive to IL-1β blockade (Table 1). In general, these diseases are poorly controlled with immunosuppressive therapies, and responses to blocking TNFα, if any, are modest. In this review, a growing number of unrelated diseases often responsive to blocking IL-1β are discussed.

Table 1.

Blocking IL-1β in treatment of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases

| Classic autoinflammatory diseases |

| Familial Mediterranean fever (FMF) |

| Pyogenic arthritis, pyoderma gangrenosum, acne (PAPA)*† |

| Cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPS) |

| Hyper IgD syndrome (HIDS) |

| Adult and juvenile Still disease |

| Schnitzler syndrome |

| TNF receptor-associated periodic syndrome (TRAPS) |

| Blau syndrome; Sweet syndrome |

| Deficiency in IL-1 receptor antagonist (DIRA) |

| Probable autoinflammatory diseases |

| Recurrent idiopathic pericarditis |

| Macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) |

| Urticarial vasculitis |

| Antisynthetase syndrome |

| Relapsing chondritis |

| Behçet disease |

| Erdheim-Chester syndrome (histiocytosis) |

| Synovitis, acne, pustulosis, hyperostosis, osteitis (SAPHO) |

| Common diseases mediated by IL-1β |

| Rheumatoid arthritis‡ |

| Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis syndrome (PFAPA) |

| Urate crystal arthritis (gout) |

| Type 2 diabetes |

| Smoldering multiple myeloma |

| Postmyocardial infarction heart failure |

| Osteoarthritis |

Complete list of citations is in supplemental References (available on the Blood Web site; see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article).

Incomplete responses to IL-1β blockade have been reported.

The combination of IL-1 plus TNFα have been used in some disorders.

Rheumatoid arthritis is also treatable with other anticytokines, antireceptors, immunomodulating agents, and B cell–depleting antibodies.

From IL-1α and IL-1β to the IL-1 superfamily of ligands and receptors

Similarities in the IL-1 family

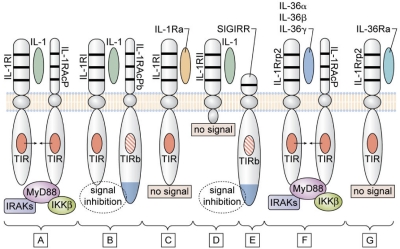

Although the original IL-1 family comprised only IL-1α and IL-1β, the IL-1 family has expanded considerably. As shown in Table 2, there are 11 members. The IL-1R family has also expanded to 9 distinct genes and includes coreceptors, decoy receptors, binding proteins, and inhibitory receptors.7 In terms of human disease, the properties of IL-1 itself still remain the model for mediating inflammation. As shown in Figure 1, IL-1α or IL-1β bind first to the ligand-binding chain, termed type I (IL-1RI). This is followed by recruitment of the coreceptor chain, termed the accessory protein (IL-1RAcP). A complex is formed of IL-1RI plus IL-1 plus the coreceptor. The signal is initiated with recruitment of the adaptor protein MyD88 to the Toll-IL-1 receptor (TIR) domain (see “IL-1 and TLR share similar functions”). Several kinases are phosphorylated, NF-κB translocates to the nucleus, and the expression of a large portfolio of inflammatory genes takes place. Signal transduction in IL-1–stimulated cells has been reviewed in detail by Weber et al.8

Table 2.

The IL-1 family

| Family name | Name | Receptor | Coreceptor | Property |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-1F1 | IL-1α | IL-1RI | IL-1RacP | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F2 | IL-1β | IL-1RI | IL-1RAcP | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F3 | IL-1Ra | IL-1RI | NA | Antagonist for IL-1α, IL-1β |

| IL-1F4 | IL-18 | IL-18Rα | IL-18Rβ | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F5 | IL-36Ra | IL-1Rrp2 | NA | Antagonist for IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36γ |

| IL-1F6 | IL-36α | IL-1Rrp2 | IL-1RAcP | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F7 | IL-37 | ?IL-18Rα* | Unknown | Anti-inflammatory |

| IL-1F8 | IL-36β | IL-1Rrp2 | IL-1RAcP | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F9 | IL-36γ | IL-1Rrp2 | IL-1RAcP | Proinflammatory |

| IL-1F10 | IL-38 | Unknown | Unknown | Unknown |

| IL-1F11 | IL-33 | ST2 | IL-1RAcP | Th2 responses, proinflammatory |

NA indicates not applicable.

Question mark indicates needs confirmation.

Figure 1.

Signaling and inhibition of signaling by IL-1Rs. (A) IL-1α (either precursor or mature) or mature IL-1β bind to the IL-1RI and with the IL-1RAcP forms the receptor heterodimeric complex. The TIR domain of each receptor chain approximate recruit MyD88, followed by phosphorylation of IL-1R–associated kinases (IRAKs) and inhibitor of NFκB kinase β (IKKβ), resulting in a signal to the nucleus. (B) In the brain and spinal cord, the variant IL-1RAcPb can form the heterodimeric complex with IL-1α or IL-1β and IL-1RI, but this complex fails to recruit MyD88, and there is inhibition of the IL-1 signal. The failure to recruit MyD88 may be because of an altered TIR domain (indicated as TIRb). (C) IL-1Ra binds to IL-1RI, but there is no signal because there is failure to form a complex with IL-1RAcP. (D) IL-1β binds to the IL-1RII, but lacking a cytoplasmic segment, there is no signal. (E) Because of an altered TIR domain (indicated as TIRb), SIGIRR inhibits IL-1 and TLR signaling. SIGIRR can form a complex with IL-33 (not shown) and inhibit IL-33 signaling. (F) IL-1Rrp2 binds IL-36α, IL-36β, or IL-36γ and forms a complex with IL-1RAcP. The TIR domain of each receptor chain approximates and recruits MyD88 similar to that shown in panel A. (G) IL-36Ra binds to IL-1Rrp2 but fails to form a complex with IL-1RAcP. Thus, IL-36Ra prevents the binding of IL-36α, IL-36β, or IL-36γ to IL-1Rrp2, and IL-36Ra is the natural receptor antagonist IL-36.

Similarly, IL-18 first binds to its ligand binding chain, IL-18Rα, recruits its coreceptor the IL-18Rβ chain, and a proinflammatory signal is initiated (Figure 1; Table 2). Family members IL-36α, β, and γ (formerly termed IL-1F6, IL-1F8, and IL-1F9) bind to the IL-1Rp2, recruit the same IL-1RAcP, and a proinflammatory signal is initiated. IL-36Ra (formerly IL-1F5) also binds to the IL-1Rp2, but does not recruit IL-1RAcP and acts as the natural-occurring receptor antagonist for IL-36α, β, and γ. IL-33 binds to ST2, also recruits the IL-1RAcP, but Th2-like properties characterize IL-33. Thus, the 6 proinflammatory members of the IL-1 family each recruit the IL-1RAcP coreceptor with the TIR domain and MyD88 docks to each.

Active precursors

With the sole exception of IL-1Ra, each member of the IL-1 family is first synthesized as a precursor without a clear signal peptide for processing and secretion, and none are found in the Golgi. IL-1α and IL-33 are similar in that their precursor forms can bind to their respective receptor and trigger signal transduction. Although recombinant mature forms of IL-1α and IL-33 are active, it remains unclear whether the mature forms are representative of the naturally occurring IL-1α and IL-33 produced in vivo. The importance of the biologic activity of the IL-1α precursor is discussed below. The precursor forms of IL-18 and IL-1β do not bind their respective receptors, are not active, and require cleavage by either intracellular caspase-1 or extracellular neutrophilic proteases (see below).

Dual-function cytokines

IL-1α and IL-33 are “dual-function” cytokines in that in addition to binding to their respective cell surface receptors, the intracellular precursor forms translocate to the nucleus and influence transcription.9,10 IL-33 is a bona fide transcription factor, and the IL-1α N-terminal amino acids contain a nuclear localization site (reviewed in Dinarello7). In general, the nuclear function of IL-1α or IL-33 is transcription of proinflammatory genes. For example, expression of the N-terminal amino acids of IL-1α stimulates IL-8 production in the presence of complete blockade of the IL-1RI on the cell surface.10 IL-37, formerly IL-1F7, also translocates to the nucleus.11 but, in the case of IL-37, there is a net decrease in inflammation.11,12 As such, IL-37 is a unique ligand in the IL-1 family because it functions as an anti-inflammatory cytokine (see below).

IL-1 and TLR share similar functions

The IL-1 family of receptors is unique in its class of Ig-like receptors because of the presence of the TIR domain in cytoplasmic segment of each member (reviewed in O'Neill13). The Toll protein was originally studied for its role in embryogenesis of the fruit fly Drosophila. After John Sims reported the cDNA of the IL-1RI, it was reported that the cytosolic segment of the IL-1RI shared a 50-aa homologous domain with the Toll protein in Drosophila. The significance of this observation was unclear until a few months later when Heguy et al14 demonstrated that the 50-aa domain in the IL-1RI was essential for IL-1 activities. Was the same domain in the Toll protein also functional for properties that were similar to IL-1 properties? It was not until 1996 that a role for the Toll protein in host defense of the fly was shown. But in 1988 van der Meer et al15 had already reported that a low dose of IL-1 protected the host against live infections. Thus, the link of the Toll protein to IL-1 and to nonspecific host defense against invading microorganisms had already been made. In 1992, Charles Janeway replaced the term “nonspecific resistance to infection” with “innate immune response.“ Still later, the existence a mammalian cell surface receptor for microbial products was shown and as reviewed by O'Neill,13 these receptors are now called Toll-like receptors (TLRs). All TLRs share the TIR domain with the IL-1RI. With the new term “innate immunity” came the term “acquired immunity,” and the concept that innate immunity affects acquired immunity. However, looking back, IL-1 is the best example of the nonspecific nature of an “innate” cytokine. That innate immunity affects acquired immunity had already been reported in 1979, with the demonstration that human IL-1β enhanced antigen-specific responses of murine T cells.16

Humans have 11 TLRs.13 Each has a unique extracellular domain containing of leucine-rich repeats, which recognize a diverse number of bacterial products, nucleic acids, and possibly some endogenous lipoproteins. Intracellularly, however, each TLR has a functional TIR domain as does the IL-1RI. Similar to IL-1 receptors, TLRs recruit the intracellular adaptor protein MyD88 to the TIR domain as the first step in signal transduction. The TIR domain is also present in 2 IL-1 family receptors that function to inhibit inflammation (Figure 1): the single Ig IL-1–related receptor (SIGIRR)17 and the newly discovered IL-1R accessory protein, IL-1RAcPb.18 The TIR of these inhibitory receptors have amino acid substitutions, which alter charge distribution of the TIR domain and prevent the recruitment of MyD88.18

Because deletion of the TIR domain from IL-1RI prevented IL-1 signaling,14 the presence of a functional TIR domain in both IL-1 and TLRs suggested that microbial products such as endotoxin could be ligands for TLRs. However, it was not until 1998-1999 that different groups reported microbial products as ligands for TLRs. The TIR domain is perhaps one of the most conserved sequences in both plants and animals.13 The near ubiquitous presence of the TIR domain shows an unexpected duplication in evolution. Receptor signaling by the IL-1 family as well as for a large number of bacterial products and viral nucleic acids depend on the same TIR domain; therefore, the inflammatory manifestations are similar.

Are endogenous mammalian proteins ligands for TLRs?

There is considerable specificity of each IL-1 family ligand for its respective receptor. There appears to be less specificity in the TLRs for the diversity of molecular structures in binding ligands, particularly for TLR2. For example, several products of Gram-positive bacterial and mycobacterial organisms are ligands for TLR2. However, there are reports showing a reduction in disease severity with blocking TLR2 in models that are IL-1 dependent but independent of microbial products.19,20 A role for TLRs in such models raises the issue whether the extracellular segment of the TLRs recognizes a wide variety of endogenous proteins. Although there is some evidence for this possibility, particularly in TLR2, an alternative explanation for disease modification in mice deficient in specific TLRs may relate to a nonspecific coactivation or recruitment of the TIR domain of a particular TLR during signal transduction of a specific cell surface or intracellular receptor. For example, during signal transduction after the binding of IL-1 to its receptor, the TIR domain on TLR2 recruits MyD88 and contributes to the activation of NFκB. This intracellular coactivation is often termed “cross talk.”

Limiting inflammation in the IL-1 family of cytokines and receptors

Two receptor antagonists

As listed in Table 2, IL-1Ra binds to IL-1RI and is specific for preventing the activity of IL-1α and IL-1β. As shown in Figure 1, IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ each bind to IL-1Rrp2, recruit IL-1RAcP, and initiate a proinflammatory signal. For example, IL-36α inhibits the differentiation of adipocytes and induces insulin resistance.21 However, IL-36Ra also binds to IL-1Rrp2, but similar to IL-1Ra, does not recruit IL-1RAcP. Therefore, IL-36Ra is the specific receptor antagonist for IL-1Rrp2 and prevents the activity of IL-36α, IL-36β, and IL-36γ.22 In the skin, overexpression of IL-36α produces an inflammatory phenotype similar to that of psoriasis and is antagonized by IL-36Ra.22

IL-1 receptor type II

IL-1 receptor type II (IL-1RII) does not signal because it lacks a cytoplasmic domain, and, without a TIR domain, docking of MyD88 cannot take place (Figure 1). This receptor is expressed mostly on macrophages and B cells. IL-1RII binds IL-1β with a greater affinity than that of IL-1RI, thereby sequestering IL-1β. Hence, cell surface IL-1RII functions as a decoy receptor for IL-1β.23 Because IL-1RAcP is recruited to the IL-1RII–IL-1β complex, the decoy receptor also serves to sequester the accessory receptor from participating in IL-1 signaling from the IL-1RI. The type II receptor is highly conserved and is found in bony fish where it functions to inhibit inflammation because of IL-1β. The soluble (extracellular) domain binds both mature as well as the IL-1β precursor. Although the soluble type II receptor is an effective anti-inflammatory agent, for optimal neutralization of IL-1β, the soluble type II receptor, requires the soluble form of the IL-1RAcP.24 A splice variant of this receptor codes for the extracellular domains and functions as an acute phase protein synthesized and released from the liver.

From a clinical perspective, expression of surface IL-1RII or circulating levels of soluble IL-1RII appear to affect the degree of inflammation in several diseases. Glucocorticoids induce expression of surface IL-1RII, and this property may contribute to their anti-inflammatory effects. For instance, in patients with an acute loss in hearing because of an unknown autoimmune process, a robust induction of IL-1RII by dexamethasone on blood monocytes correlated with clinical response to oral prednisone. In contrast, cells from patients unresponsive to prednisone did not increase expression of the decoy receptor.25 The production of IL-1β appears to play a role in endometriosis and related infertility. Peritoneal fluid from fertile and infertile women with endometriosis had lower soluble IL-1RII and higher IL-1β concentrations than healthy controls, and the increase in IL-1β was significant in women with endometriosis who reported pelvic pain.26 These and several clinical studies support the concept that, like the balance of IL-1 to IL-1Ra, the amount of surface or soluble IL-1RII affects disease severity.

SIGIRR

The SIGIRR (also known as TIR817) is a unique receptor in the IL-1 receptor family and functions to inhibit TLR- as well as cytokine-mediated signals.27,28 As shown in Figure 1, the extracellular domain contains a single IgG-like domain; the cytosolic portion does contain the TIR domain, but the 2 aa required for a functional TIR domain are absent. In addition, the C-terminal contains an extra 95-aa extension, which may contribute to the anti-inflammatory properties of this receptor.17 Although a ligand for SIGIRR has not been identified, the single Ig-like domain is required for its inhibitory function. SIGIRR also forms a complex with the precursor form of IL-33,29 which may explain some of the anti-inflammatory properties of IL-33. For example, IL-33 reduces the development of atherosclerosis as well as cardiomyocyte hypertrophy. Intracellularly, SIGIRR reduces NF-κB activation by members of the IL-1 family (IL-1, IL-18, and IL-33), as well as by the family of TLRs. Compared with wild-type mice, mice deficient in SIGIRR exhibit a severe inflammatory response to colitis28 and more severe responses to acute renal injury, which is because of a greater infiltration of myeloid cells into the renal parenchyma.30 With the use of the same model of acute renal injury, caspase-1–deficient mice are protected, most likely because of decreased IL-18 activity rather than decreased IL-1 effects.31 Thus, SIGIRR may keep IL-18 activity in the kidney at bay.

IL-1RAcPb

The IL-1RAcP serves as the coreceptor for IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-36α, IL-36β, IL-36γ, and IL-33, each a proinflammatory cytokine. However, a unique form of the IL-1RAcP has been found in the brain where it serves to decrease IL-1 activities.18 Termed IL-1RAcPb, this coreceptor forms the expected complex with IL-1 and IL-1RI but does not recruit MyD88 or phosphorylate IL-1R–associated kinase 4. Therefore, most IL-1 signaling is arrested. But, because some genes increase by the IL-1RI/IL-1RAcPb complex, partial IL-1 signaling takes place. Nevertheless, IL-1RAcPb functions as an inhibitory receptor chain only in the brain. Mice deficient in IL-1RAcPb exhibit a normal inflammatory response in the periphery but greater neurodegeneration in the brain. As such, IL-1RAcPb could play a role in chronic inflammatory responses in the brain by “buffering” IL-1–mediated neurodegeneration.

Like SIGIRR, IL-1RAcPb contains the amino acid differences in its TIR domain that likely reduce binding of MyD88.18 In addition to an altered TIR domain, IL-1RAcPb has a carboxyl extension of 140 aa. Carboxyl extensions are also present in SIGIRR as well as 2 other members of the IL-1 receptor family, TIGIRR-1 and TIGIRR-2. TIGIRR-2 is associated with an X-linked cognitive deficiency, which apparently is independent of IL-1 functions. Little is known about whether these C-terminal segments contribute to the inhibitory properties of these receptors.

A compelling case for the importance of the naturally occurring IL-1Ra

Rabbits passively immunized against their own endogenous IL-1Ra exhibit a worsening of colitis,32 and mice deficient in IL-1Ra develop spontaneous diseases such as a destructive arthritis,33 an arteritis34 and a psoriatic-like skin eruption. Furthermore, mice deficient in endogenous IL-1Ra develop aggressive tumors after exposure to carcinogens.35 These data support the concept that the concentrations of IL-1β versus IL-1Ra affect the severity of some diseases. The single nucleotide polymorphism rs4251961 C allele is associated with lower circulating levels of IL-1Ra (reviewed in Dinarello36 and Larsen et al37) and is common in type 2 diabetes.37 The same polymorphism is associated with reduced survival in patients with colon carcinoma compared with those with the wild-type allele. The concept of an imbalance between IL-1β and IL-1Ra gained considerable legitimacy with reports of infants born with nonfunctional IL-1Ra.38,39 Soon after birth, the affected infants exhibited impressive systemic and local inflammation. Multiple neutrophil-laden pustular skin eruptions, vasculitis, bone abnormalities with large numbers of osteoclasts, osteolytic lesions, and sterile osteomyelitis were observed. The inflammation resembled infection with sepsis-like multiorgan failure, but all cultures were sterile. Treatment with anakinra was lifesaving; the inflammation abated, and the bone lesions disappeared. IL-17 was prominently expressed in cells from these patients (see below). These findings are an extreme example that, without functional IL-1Ra, the activity of endogenous IL-1 is “unopposed” and IL-1–driven inflammation can run rampant.

One can conclude that low levels of IL-1β can induce inflammation, but the presence of natural IL-1Ra is sufficient to limit the inflammation. IL-1Ra is found in the circulation of healthy subjects in the range of 100-300 ng/mL, whereas IL-1β is in the picogram per milliliter range and is not easily detectable by standard ELISA methods in the same persons. In healthy humans, daily total constitutive production of IL-1β has been calculated at 6 ng; in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes (CAPSs), a rare autoinflammatory disease associated with increased IL-1β secretion, the calculated amount of IL-1β was 31 ng/d.40 These low amounts are consistent with reports of increased release of IL-1β from blood monocytes of patients with autoinflammatory diseases. The increase is usually 5- to 10-fold more than that from blood monocytes of healthy subjects.41–43

IL-37, a fundamental inhibitor of innate immune responses

The function of IL-37 (formerly IL-1 family member 7) has remained elusive. Studies with the recombinant form of the cytokine have been inconsistent because of aggregation, although some reports show that recombinant IL-37 binds to the IL-18Rα chain. Nevertheless, a role for natural-occurring IL-37 in inflammation was shown by suppressing endogenous IL-37 in human blood monocytes. In those studies, both lipopolysaccharide (LPS)– and IL-1β–induced cytokine production increased significantly.12 Consistent with this observation, overexpression of IL-37 in macrophages or epithelial cells nearly completely suppressed production of proinflammatory cytokines. Mice with transgenic expression of IL-37 were protected from LPS-induced shock and showed markedly improved lung and kidney functions with reduced liver damage.12 IL-37 transgenic mice also exhibited lower concentrations of circulating and tissue cytokines (72%-95% less) than wild-type mice and showed less dendritic cell activation. Previous studies have shown that IL-37 translocates to the nucleus via a caspase-1–dependent fashion.11 IL-37 interacts intracellularly with Sma- and Mad-related protein 3 (Smad3), and IL-37–expressing cells and transgenic mice showed less cytokine suppression when endogenous Smad3 was depleted.12 It appears that IL-37 colocalizes to the nucleus with Smad3 and suppresses transcription of inflammatory genes induced by microbial products as well as cytokines themselves. Thus, IL-37 emerges as a natural suppressor of innate inflammatory and immune responses. Whether disease severity in humans is affected by the level of IL-37 expression remains to be determined.

IL-1β and the spectrum of autoinflammatory diseases

The distinction between autoinflammatory and autoimmune diseases

Nearly all autoimmune diseases have an inflammatory component. However, autoinflammatory diseases appear to be primarily inflammatory, with systemic as well as local manifestations that are often periodic rather than progressive. Autoimmune diseases are primarily caused by dysregulation of adaptive immune responses and because of pathologic antibodies or autoreactive T cells. In contrast, some classic autoinflammatory diseases are caused by genetic defects in innate inflammatory pathways and usually are manifested early in life. Typically, autoinflammatory diseases have no associations with HLA or MHC class II haplotypes, and there is and absence of autoreactive T cells or autoantibodies. However, some complex systemic inflammatory diseases are driven by autoinflammatory mechanisms, but adaptive pathways also seem to play a role. For example, in Behçet disease, there is a strong association with HLA-B51, which probably contributes an autoimmune component of the disease.

Familial Mediterranean fever, familial cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome, and CAPS are classic examples of autoinflammatory diseases.6,44 TNF receptor associated periodic syndrome was the first disease to be labeled as autoinflammatory. As shown in Table 1, there are a growing number of diseases that fall under the category of being primarily autoinflammatory. One of the most consistent characteristics of these autoinflammatory diseases is a rapid and sustained resolution of disease severity on treatment with IL-1β blockade, although there are exceptions. In the case of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis, there are often but not always dramatic responses to IL-1β blockade.41,45 Although antibodies to the IL-6 receptor are also effective in this disease, a reduction in IL-1β activity probably reduces IL-6 production. Autoinflammatory diseases are weakly responsive to TNFα neutralization, and, in some reports, disease worsens with TNFα blockade. Although autoimmune diseases respond to anti-TNFα, CTLA4-Ig, anti–IL-6 receptor, depletion of CD20 B cells, depletion of CD3 T cells, anti–IL-17, or anti–IL-12/IL-23 antibodies, these agents are often ineffective in patients with autoinflammatory diseases. For example, in the case of Schnitzler syndrome with a monoclonal gammopathy, depletion of B cells resulted in a dramatic reduction in the paraprotein but was of no benefit on systemic symptoms. In contrast, anakinra resulted in a rapid improvement sometimes within hours and a complete remission in disease activity within days.46 Table 1 lists autoinflammatory diseases that, for the most part, respond to blocking IL-1 activity.

Clinical characteristics of systemic autoinflammatory diseases

Systemic autoinflammatory diseases are syndromes.5,6,47 As listed in Table 1, although many are rare, the clinical manifestations are common. Fever, neutrophila, and elevated hepatic acute phase proteins are characteristically present with painful joint, myalgias, and debilitating fatigue. These manifestations are consistent with the responses observed in humans after administration of intravenous IL-1; fever, neutrophilia, and elevated IL-6 and adrenocorticotropic hormone levels were observed at doses of IL-1α or IL-1β as low as 1-3 ng/kg.1

Patients with CAPS can present with a spectrum of disease severity. In the mildest form, familial cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome, the episodes are triggered by cold exposure.44 A more severe form is Muckle-Wells syndrome, in which the inflammation is persistent and apparently not related to cold but associated with the development of hearing loss and amyloidosis.48 The most severe form of CAPS is neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease, which, in addition to systemic inflammation, is also associated with joint deformities and developmental disabilities in early childhood.42 Often, on blocking IL-1β, patients with CAPS and other autoinflammatory diseases experience a rapid and sustained cessation of symptoms as well as reductions in biochemical, hematologic, and functional markers of their disease.42,49,50 Because treatment with the soluble IL-1RI rilonacept or a monoclonal anti–IL-1β antibody (canakinumab) are equally effective in treating autoinflammatory diseases,49,50 the culprit in these diseases is IL-1β and not IL-1α.

Caspase-1–dependent and –independent processing of the IL-1β precursor into an active cytokine

Increased release of IL-1β in autoinflammatory diseases

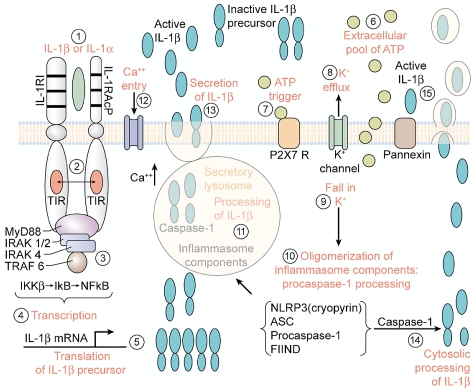

Fundamental to many autoinflammatory diseases is an increased release of active IL-1β. Caspase-1 is the intracellular cysteine protease that cleaves the N-terminal 116 aa from the IL-1β precursor, thus converting the inactive precursor to the active “mature” cytokine. Caspase-1 exists in tissue macrophages and dendritic cells as an inactive zymogen and requires conversion to an active enzyme by autocatalysis. However, in circulating human blood monocytes, caspase-1 is present in an active state.51 Caspase-1 is also constitutively active in highly metastatic human melanoma cells.52 In general, the release of active IL-1β from blood monocytes is tightly controlled with < 20% of the total IL-1β precursor being processed and released. Although the release of active IL-1β from blood monocytes of healthy subjects takes place over several hours, the process can be accelerated by increased levels of extracellular ATP, which triggers the P2X7 purinergic receptor (Figure 2).53,54

Figure 2.

Steps in the processing and release of IL-1 induced by IL-1. (1) Primary blood monocytes, tissue macrophages or dendritic cells are activated by either mature IL-1β or the IL-1α precursor with the formation of the IL-1 receptor complex heterodimer comprised of the IL-1RI with IL-1RAcP. (2) Approximation of the intracellular TIR domains. (3) Recruitment of MyD88 and phosphorylation of IL-1R–associated kinases (IRAKs) and inhibitor of NFκB kinase β (IKKβ). (4) Transcription of IL-1β. (5) Translation into the IL-1β mRNA takes place on polysomes. IL-1β mRNA is not bound to actin microfilaments but rather intermediate filaments. (6) ATP released from the activated monocyte/macrophage accumulates extracellularly.51 (7) Activation of the P2X7 receptor by ATP. (8) Efflux of potassium from the cell after ATP binding to P2X7 receptor. (9) Fall in intracellular levels of potassium. (10) The fall in intracellular potassium levels triggers the assembly of the components of the caspase-1 inflammasome with the conversion of procaspase-1 to active caspase-1. (11) Caspase-1 is found in the secretory lysosome together with the IL-1β precursor and lysosomal enzymes.53 Active caspase-1 cleaves the IL-1β precursor in the secretory lysosome, generating the active, carboxyl-terminal mature IL-1β. (12) An influx of calcium with an increase in intracellular calcium levels. The rise in intracellular calcium activates phosphatidylcholine-specific phospholipase C and calcium-dependent phospholipase A. (13) The release of mature IL-1β, the IL-1β precursor, and the contents of the secretory lysosomes by exocytosis in the absence of cell death. (14) Processing of the IL-1β precursor in the cytosol. Rab39a, a member of the GTPase family, contributes to the secretion of by helping traffic IL-1β from the cytosol into a vesicle compartment. Exocytosis is another mechanism described in mouse macrophages. (15) Mature IL-1β exists the cells via loss in membrane integrity, associated with the release of lactic dehydrogenase or microvesicles. TRAF indicates TNF receptor-associated factor.

Activation of caspase-1

As shown in Figure 2, after ATP binding to the P2X7 receptor, there is a rapid exit of potassium from the cell, and intracellular potassium falls. With inhibition of ATP binding or in cells deficient in the P2X7 receptor, the amount of secreted IL-1β is low or absent.55 The fall in intracellular potassium is thought to bring about the oligomerization of a highly specialized group of intracellular proteins termed the “inflammasome,” which convert procaspase-1 to an active enzyme.56 Active caspase-1 then cleaves the IL-1β precursor in specialized secretory lysosomes or in the cytosol, followed by secretion of “mature” IL-1β (Figure 2). Blood monocytes from patients with autoinflammatory syndromes release more processed IL-1β than cells from healthy subjects and thus likely account for the inflammation in these diseases.40–43 An increase in the secretion of active IL-1β is observed in monocytes from patients with a gain-of-function mutation in a gene originally called cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome-1.57 The mutations in this gene result in a single amino acid change in the intracellular protein named cryopyrin, because after the exposure to cold, the patients develop fever and other manifestations of systemic inflammation. Cryopyrin is now termed nucleotide-binding domain and leucine-rich repeat-containing protein 3 (NLRP3).

The gene cold-induced autoinflammatory syndrome-1was first reported by Hoffman et al in 2001,57 and a historical perspective of this important discovery has been published.7 In 2004, NLRP3 was reported to associate with procaspase-1 and other intracellular proteins to form a complex, which was termed the “inflammasome.”56 As shown in Figure 2, these components activate procaspase-1, resulting in active caspase-1, followed by the processing and secretion of active IL-1β. However, approximately one-half of the patients with classic symptoms and biochemical markers of CAPS, familial Mediterranean fever, and other autoinflammatory diseases do not have mutations, and the basis for increased secretion of IL-1β remains unknown. As noted above, the increase in IL-1β secretion in monocytes from patients with autoinflammatory diseases is modest compared with that of monocytes from healthy subjects. Despite severe systemic inflammation, only a 5-fold more IL-1β is produced each day in patients with CAPS compared with healthy controls.40

Secretion of IL-1β

As shown in Figure 2, multiple mechanisms have been reported for the secretion of the processed mature IL-1β; these include the loss of membrane integrity, a requirement for phospholipase C and secretory lysosomes,53 and the shedding of plasma membrane microvesicles or multivesicular bodies containing exosomes. In general, the release of active IL-1β takes place before there is significant release of lactate dehydrogenase, although some report that the release of IL-1β parallels that of lactate dehydrogenase. Pyroptosis is a caspase-1–dependent mechanism for cell death with the release of IL-1β58 and may account for the release of active IL-1β in ischemic disease.58

Because caspase-1 is present in an active form in freshly obtained blood monocytes from healthy subjects,51 the rate-limiting step in the secretion of IL-1β is at the transcriptional and translational levels. But in monocytes from patients with single amino acid mutation in NLRP3, the release of active IL-1β occurs without a requirement for a rapid fall in the level of intracellular potassium.43 Although often studied with the use of endotoxin-induced synthesis of the IL-1β precursor, inflammation in autoinflammatory diseases is sterile. Continued treatment with anakinra results in a progressive reduction in the secretion of IL-1β from monocytes compared with secretion before treatment.42,43 A reduction in steady-state caspase-1 gene expression also takes place.42 Thus, IL-1 itself increases the synthesis of caspase-1 as well as its own IL-1β precursor59 and may account for the autoinflammation of these diseases.

Caspase-1–independent processing of the IL-1β precursor into an active cytokine

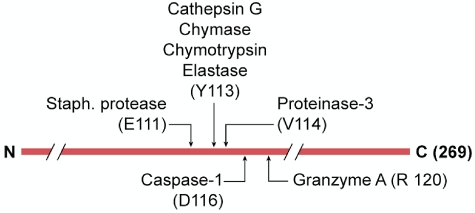

In the arthritic joint and after blunt trauma, hypoxia, hemorrhage, or exposure to irritants, there is a brisk myeloid response into the affected tissues dominated by neutrophils. Although IL-1β often plays a pivotal role in these conditions, caspase-1 may not be required. For example, IL-1β is required for irritant-induced inflammation in muscle tissue but is caspase-1 independent.60 Similarly, cartilage destruction in joints61 and urate crystal–induced inflammation62 are also IL-1β dependent but caspase-1 independent. In many models of sterile inflammation, cell death and release of the IL-1β precursor from resident macrophages or infiltrating monocytes take place. With the infiltrating neutrophils, there is also a role for neutrophil proteases. As shown in Figure 3, these proteases include elastase, chymases, granzyme A, cathepsin G, and proteinase-3. In particular, proteinase-3 cleaves the inactive IL-1β precursor close to the caspase-1 site, resulting in active IL-1β.60,61 Moreover, inhibition of neutrophil proteases prevented urate crystal–induced peritonitis.62 These findings question whether caspase-1 is responsible for IL-1β–dependent inflammation in patients with gout or any inflammatory process in which there is a robust infiltration of neutrophils in the release of the IL-1β precursor into the extracellular space.

Figure 3.

Non–caspase-1 extracellular processing of the IL-1β precursor. The 269-aa-long IL-1β precursor is shown with the caspase-1 site at aspartic acid (D) at position 116. Extracellular protease sites are indicated by their amino acid recognition sites. The probable proteinase-3 site was derived from combinatorial methods of the specific substrate.

Role of reactive oxygen species on caspase-1–dependent secretion of IL-1β

Inflammation and carcinogenesis are associated with the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs), and ROSs have been proposed to activate the caspase-1 inflammasome.63 Because IL-1β appears to play a role in carcinogenesis,35 it is an attractive hypothesis that ROSs directly activate the inflammasome to induce release of IL-1β and trigger inflammation. However, in cells deficient in gp91phox ROSs, levels are low and IL-1β levels are high, and in cells deficient in super oxide dismutase-1, ROS levels are high but caspase-1 is suppressed and IL-1β levels are low.64

Like murine cells deficient in gp91phox, humans with chronic granulomatous disease have a mutation in p47-phox, with defective NADPH activity and are unable to generate ROSs. Blood monocytes from these patients release IL-1β after stimulation in vitro.65,66 Although the well-known inhibitor of ROSs, diphenylene iodonium, reduces the secretion of IL-1β in all studies, diphenylene iodonium inhibits IL-1β and also TNFα gene expression rather than caspase-1 activity.65 Thus, it appears that ROSs may dampen the inflammasome, and this may explain why patients with chronic granulomatous disease, who are unable to generate ROSs, have increased inflammation with granulomatous lesions and a form of colitis indistinguishable from that found in Crohn disease. It has also been shown that ROS induces intracellular N-acetylcysteine, a potent antioxidant, which facilitates the secretion of active IL-1β.67 Although ROS generation from mitochondria may contribute to caspase-1 activation, there is the conundrum that, regardless of the source of ROS, the concept is not supported by decades of failed placebo-controlled antioxidant trials.

Role of IL-1α in ischemia-induced inflammation

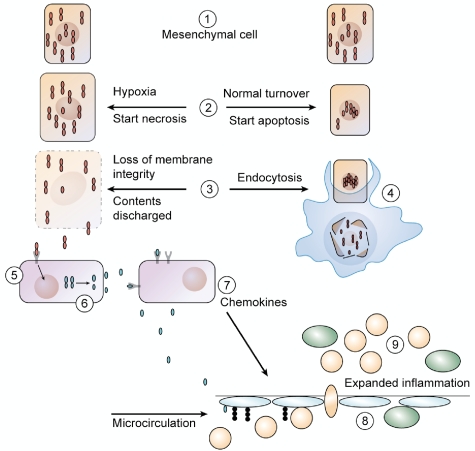

Cells of mesenchymal origin constitutively contain preformed IL-1α precursor, for example, keratinocytes, endothelial cells, and epithelial cells of the lung, kidney, and gastrointestinal tract. If released from its intracellular pool in healthy cells, the IL-1α precursor is inflammatory. Thus, it was not unexpected that robust inflammatory responses were observed when extracts of cellular contents from healthy tissues containing the IL-1α precursor on injection into the peritoneal cavity of mice.68,69 Importantly, inflammation was shown to be MyD88 and IL-1RI dependent but TLR independent.68,69 Intracellular IL-1α is found diffusely distributed in the cytosol as well as in the nucleus where it associates with chromatin.70 The N-terminal domain of the IL-1α precursor contains a nuclear localization sequence, which actively participates in transcription10,71 and affects the senescence of cells.

As shown in Figure 4, during the hypoxia of an ischemic event, there is loss of membrane integrity in dying cells with the release of intracellular contents, which include the IL-1α precursor.70 Subsequently, resident tissue macrophages respond to IL-1α and produce IL-1β (Figure 4). Although ischemia-induced inflammation is often initiated by the IL-1α precursor, it rapidly becomes caspase-1 and IL-1β dependent.72 Adenovirus infection induces a neutrophil infiltration that is independent of TLR9 and NLRP3,73 and the inflammation is because of IL-1α activation of the IL-1RI with a brisk production of chemokines.73 Cell death by a caspase-1–dependent process called pyroptosis may also take place in ischemic tissues with the release of cell contents.58

Figure 4.

Role of IL-1α in necrosis versus apoptosis. (1 left and right) In healthy cells of mesenchymal origin, the IL-1α precursor is found diffusely in the cytoplasm but also in the nucleus where it binds to chromatin. (2 right) During normal cell turnover, an apoptotic signal drives cytoplasmic IL-1α into the nucleus and is no longer a dynamic in the cell. The cell shrinks. (2 left) Cells exposed to hypoxia begin to die, and nuclear IL-1α moves out of the nucleus into the cytoplasm. Taking on water, the cell swells as the necrotic process begins. (3 left) As the necrotic process continues, there is loss of membrane integrity, and cytoplasmic contents containing the IL-1α precursor leak out. (3 right) Tissue macrophages take up the apoptotic cell into endocytotic vesicles. (4) In the vesicles, the apoptotic cell is digested, and there is no inflammatory response from the macrophage. (5 left) The IL-1α precursor is released into the extracellular compartment and binds to IL-1RI expressed on adjacent cells or to resident tissue macrophages. The tissue macrophage responds with synthesis of the IL-1β precursor as well as increased in caspase-1. From step 3 left, ATP is also released on cell death and activates the P2X7 receptor for activation of caspase-1. (6) Caspase-1 is activated by the inflammasome, cleaves the IL-1β precursor, and mature, active IL-1β is released. Alternatively, IL-1β is released via pyroptosis. (7) Once released, IL-1β induces chemokine production, resulting in a chemoattractant gradient. (8) As the endothelium of the microcirculation expresses adhesion molecule, blood neutrophils adhere and cross into the ischemic area. (9) With the infiltration of myeloid cells (monocytes and neutrophils), there is expanded inflammation, which extends beyond the initial area of ischemia.

In contrast, the same mesenchymally derived cells undergo apoptosis as part of normal tissue renewal. During apoptosis, intracellular IL-1α concentrates in dense nuclear foci, and chromatin binding is not reversed by histone deacetylases or affected by inhibitors of ROSs.70 As shown in Figure 4, in apoptotic cells, IL-1α is retained within the chromatin fraction and is not present in the cytoplasmic contents. As such, lysates of cells undergoing apoptotic death are biologically inactive.70 Thus, nuclear trafficking and differential release during necrosis versus apoptosis (Figure 4) show that inflammation by IL-1α is tightly controlled.

IL-1β, periodontitis, and bone loss

Epidemiologic studies have examined polymorphisms in the IL-1 gene cluster (IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-1Ra) with increased periodontitis and tooth loss as well as with coronary heart disease (CHD) and type 2 diabetes. In a study in Germany, > 1500 subjects with increased levels of glycosylated hemoglobin were found to have significant periodontal disease compared with normoglycemic subjects. Diabetics with IL-1β promoter genotype C/T or T/T exhibited a more severe form of periodontitis than their wild-type IL-1β counterparts, suggesting that carrying these polymorphisms increases the inflammation. In another study, mean alveolar bone levels were measured in patients with CHD. The same polymorphisms were associated with bone loss. An IL-1Ra polymorphism was also associated with both CHD and the highest level of bone loss. In patients with the IL-1α +4845T polymorphism, there was a statistically significant correlation with acute coronary syndrome and severe periodontitis.

The mechanism of IL-1β production in periodontitis has been extensively studied with the use of bacteria isolated from patients with long-standing disease. The most persistent bacterial infection in periodontitis is Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, which infects the periodontal space in many throughout the world and is the most common cause of tooth loss.74 These organisms produce a leukotoxin, which induces degranulation and lysis in human neutrophils. The leukotoxin also activates caspase-1 and the secretion of large amounts of IL-1β from human macrophages.74 IL-1β is a known player in bone loss in patients with rheumatoid arthritis, and the amino acid sequence of purified osteoclast-activating factor is identical to that of IL-1β. Thus, the induction of IL-1β in the periodontal space by the leukotoxin probably explains alveolar bone tooth loss with periodontitis. Because the inflammation in periodontitis appears to be IL-1β–mediated, IL-1β entering the circulation from the local inflammation in the periodontal space may affect the distant insulin-producing β cell in the pancreatic islet and account for the association of periodontitis with type 2 diabetes.

IL-1 in B- and T-cell responses

IL-1β as an adjuvant

A role for IL-1β in antibody production has been repeatedly reported (reviewed in Kelk et al75). Not unexpectedly, the most widely used adjuvant, aluminum hydroxide (alum), induces IL-1β via a caspase-1–dependent mechanism. Previous studies have shown that mice deficient in IL-1β do not produce anti–sheep red blood cell antibodies, a T-dependent response. In wild-type mice, IL-1β causes a marked increase in the expansion of naive and memory CD4 T cells in response to antigen and particularly when used with LPS as a costimulant.76 In fact, when LPS is used as an adjuvant ∼ 55% of the antibody response is because of IL-1.76 There are also striking increases in serum IgE and IgG1 levels. The role of IL-1β on the expansion and differentiation of CD4 T cells is independent of IL-6 or CD28 but rather because of IL-17– and IL-4–producing cells. In human T cells, Th17 polarization induced by Mycobacterium tuberculosis is IL-1β dependent77 via dectin-1 and TLR4 stimulation. This observation has relevance to models of experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) and collagen-induced arthritis, both of which require the complete Freund adjuvant, a mixture of killed M tuberculosis and the irritant croton oil. These results indicate that IL-1β signaling in T cells induces durable primary and secondary CD4 responses, most probably because of the induction of IL-17.

A role for IL-1 in the generation of Th17 polarization

Increasingly, clinical studies indicate that T-cell differentiation into IL-17–producing cells plays a major role in some autoimmune diseases, and IL-1 appears to play a pivotal role in the polarization of T cells toward Th17.78,79 The role of IL-1β in the generation of Th17 cells is also consistent with the inflammation in mice deficient in IL-1Ra.80 In mice deficient in IL-1Ra, the activity of endogenous IL-1 is unopposed, and spontaneous rheumatoid arthritis-like disease develops33 but not in mice also deficient in IL-17.81 In mice specifically deficient in endogenous IL-1Ra in myeloid cells, collagen-induced arthritis appears to be because of unopposed IL-1 activity, which drives IL-17.82 IL-1–dependent IL-17 production may be relevant to EAE, the rodent model for multiple sclerosis. Mice deficient in both IL-1α and IL-1β do not develop EAE, which is thought to be a failure to mount a Th17 response. In mice deficient in caspase-1, EAE is markedly attenuated. Thus, IL-1 rather than TNFα blockade reduces disease severity in mice subjected to EAE; in fact, blocking TNFα worsens the outcome of the EAE model. In rheumatoid arthritis, depleting CD20-bearing B cells results in decreased IL-17 production,83 which may be because of a reduction in B-cell IL-1β.

Although there is no dearth of reports that adding IL-1 to cultures induces IL-17, an essential role for IL-1 was shown when mice deficient in the IL-1R fail to induce IL-17 on antigen challenge.84 Moreover, IL-23 fails to sustain IL-17 in IL-1R–deficient T-cells and TNFα and IL-6 enhancement of IL-23–induced IL-17 is also IL-1 dependent.84 In a subsequent study of EAE, γ/δ CD4+ T cells were the source of IL-17 but independent of TCR engagement. γ/δ CD4+ T cells contain the retinoic acid–related orphan receptor γ transcription factor and thus a direct induction of IL-17 by IL-1 is fundamental to the Th17 paradigm. Therefore, it is probable that there is a cascade of IL-1β–induced IL-23 as well as IL-1–induced IL-6 for Th17 differentiation.

In human T cells, IL-1β–dependent Th17 differentiation is because of the intermediate production of prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) from macrophages.85 This observation is consistent with ability of IL-1β to induce cyclooxygenase 2 (reviewed in Dinarello7) and PGE2 to induce IL-6. Thus, an innate inflammatory response that is IL-1β driven appears to play a pivotal role in the outcome of EAE. To maintain Th1-driven responses, IFNγ suppresses the differentiation into the Th17 phenotype. One possible mechanism by which IFNγ suppresses Th17 is by the suppression of IL-1. IFNγ reduces the induction of IL-1 by IL-1 and also of IL-1–induced PGE2 (reviewed in Dinarello1). Thus, IFNγ suppression of IL-1–driven PGE2 as well as IL-1 itself may explain the reduction in Th17 differentiation.

Blocking IL-1β–mediated disease

Therapeutic agents

Initially, anakinra was used to treat several unrelated chronic inflammatory diseases as listed in Table 1. Today, these diseases are also successfully treated with neutralization by human anti–IL-1β monoclonal Abs. For example in type 2 diabetes, either anakinra or monoclonal Abs to IL-1β improve glycemic control.37,86,87 At this writing, one anti–IL-1β antibody (canakinumab) has been approved for treating CAPS,50 whereas others are presently in clinical trials. Rilonacept is a construct of the 2 extracellular chains of the IL-1R complex (IL-1RI plus IL-1RAcP) fused to the Fc segment of IgG and has also been approved for use in CAPS.49

Targeting IL-1β in smoldering/indolent myeloma

Monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance and smoldering myeloma present a challenge to medicine as the population ages. Several years of research has focused on the role of IL-1β and IL-6 in the pathogenesis of multiple myeloma. Similar to mature B cells, the myeloma plasma cell produces IL-1β. In the microenvironment of the BM, stromal cells respond to low concentrations IL-1β and release large amounts of IL-6, which in turn promote the survival and expansion of the myeloma cells. Although IL-6 is an essential growth factor for myeloma cells, Abs to IL-6 have not been effective in treating the disease. Lust et al4 reasoned that, in the indolent stages of multiple myeloma, blocking IL-1β would provide better reduction of IL-6 activity. BM cells from patients with smoldering myeloma were cocultured with a myeloma cell line actively secreting IL-1β. Although the addition of dexamethasone reduced stromal cell IL-6 production, the amount of IL-6 remained sufficiently high enough to protect the plasma cell against dexamethasone-mediated apoptosis. However, anakinra added to these cocultures significantly reduced IL-6 by nearly 90%, and the combination of anakinra plus dexamethasone induced myeloma cell death.4

Patients with smoldering or indolent myeloma were selected with the clinical objective of slowing or preventing progression to active disease. On the basis of in vitro data, 47 patients with smoldering/indolent myeloma at high risk of progression to multiple myeloma were treated with daily anakinra for 6 months. During the 6 months, there were decreases in C-reactive protein (CRP) in most but not all patients, which paralleled a decrease in the plasma cell–labeling index, a measure of myeloma cell proliferation in unfractionated BM cells. After 6 months of anakinra, a low dose of dexamethasone (20 mg/week) was added. Of the 47 patients who received anakinra (25 with dexamethasone), progression-free disease was > 3 years and in 8 patients > 4 years.4 Compared with historical experience, the findings indicate a significant failure to progress to active disease and a modest fall in CRP-predicted responders who continued with stable disease. Patients with a decrease in serum CRP of ≥ 15% after 6 months of anakinra monotherapy resulted in progression-free disease > 3 years compared with 6 months in patients with less than a 15% fall during anakinra therapy (P < .002). Thus, an effective reduction in IL-1β activity with the use of CRP as the marker for IL-1β–induced IL-6 halts progression to active myeloma. With the use of anakinra in > 200 000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis or autoinflammatory diseases, no opportunistic infections, including M tuberculosis reactivation, have been reported.

Angiogenesis

Angiogenesis plays a pathologic role in multiple myeloma. In vitro and in animal models, there are a growing number of reports on IL-1β as a key cytokine in angiogenesis.88–90 Compared with thalidomide or its analogues, blocking IL-1β is essentially free of toxic side effects. There is an ongoing trial at the National Institutes of Health of anakinra as an antiangiogenic therapy in patients with cutaneous melanoma. Because blocking IL-1β reduces IL-6 as well as the proangiogenic chemokine IL-8, the use of IL-1β–blocking strategies may result in therapy in high-risk patients with smoldering/indolent myeloma or metastatic melanoma. There is also a role for IL-1β in the angiogenic process of macular degeneration,91 and anakinra treatment in rheumatoid arthritis reduces the vascularization of the pannus.

Role for IL-1 in GVHD

Reducing cytokine activity in the development of GVHD is based on preclinical studies. Of the 3 phases of GVHD, immunization, proliferation, and targeting of tissue, IL-1 is least important in the primary phases of the disease, in part, because IL-1 is not dominant in the Th1 paradigm of T-cell and natural killer cell activation compared with IL-2, IL-15, and IL-18. In a placebo-controlled trial, patients were treated with anakinra 4 days before and 10 days after allogeneic stem cell transplantation added to standards of therapy. Moderate-to-severe GVHD developed in both anakinra- and placebo-treated patients.92 One can conclude that during conditioning and 10 days after transplantation, IL-1 plays no significant role in the development of the disease. In contrast, in patients with full-blown GVHD, blocking IL-1 reduced the severity of the disease.93 With the use of a continuous intravenous infusion of anakinra, there was improvement in the clinical score in 16 of 17 treated patients. Moreover, a decrease in the steady state mRNA for TNFα in peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlated with improvement (P = .001).93 It is probable that there is role for IL-1 in the inflammatory manifestations of GVHD rather than the immunologic development of the disease.

Treating gout with IL-1β neutralization

There is a long association of IL-1 production with urate crystals and a causal relationship of IL-1 with gout.94,95 Some patients with recurrent attacks of gouty arthritis resistant to colchicine and other standards of therapy often require steroids to control disease flares. When treated with anakinra, rilonacept, or canakinumab, a rapid, sustained, and remarkable reduction in pain and objective signs of reduced inflammation have been observed.96–98 The effect of IL-1 blockade appears to be superior to that of steroids and result in prolonged periods without flares. Although some studies report that urate crystals directly activate the NLRP3 for processing of the IL-1β precursor,99 it is probable that 2 signals are required; urate crystals plus free fatty acids account for IL-1β activity in flares of gout.100,101 Given the characteristic neutrophilic infiltration in gouty joints, it is also probable that the IL-1β precursor is processed extracellularly by neutrophilic enzymes as shown in Figure 3.

Effects of IL-1R blockade in stroke

Although infection, particularly septic shock, evokes a “cytokine storm” as part of a systemic inflammatory response, in many ischemic diseases, such as acute lung injury, thrombotic stroke, acute renal failure, myocardial infarction, and hepatic failure, inflammation is characterized by cell death and infiltration of neutrophils into the ischemic area. The induction of IL-1β in human monocytes exposed to hypoxia was first reported in 1991.102 Subsequently, many studies have shown an essential role for IL-1 and specifically for IL-1β and caspase-1 in various models of ischemic injury without and with reperfusion. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of anakinra was carried out in patients with acute stroke. Three days of a high dose of intravenous anakinra was administered, the same dose used in the sepsis trials.103 Peripheral white blood cells, neutrophil counts, CRP, and IL-6 concentrations were lower in patients treated with anakinra than with placebo. After 3 months, the anakinra-treated patients exhibited less loss of cognitive function than the placebo group.103

Reducing IL-1β in type 2 diabetes

For > 25 years, the cytotoxic effects of IL-1β for the insulin-producing pancreatic β cell have been studied.104 Subsequently, it was shown that high concentrations of glucose stimulated IL-1β production from the β cell itself,105 implicating a role for IL-1β in type 2 diabetes.106 In addition, free fatty acids act together with glucose to stimulate IL-1β from the β cell. The production of IL-1β also increases the deposition of amyloid via activation of NLRP3.107 In support of these studies, gene expression for IL-1β was > 100-fold higher in β cells from patients with type 2 diabetes than from patients without diabetes. The clinical proof of a role for IL-1β in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes came from a randomized, placebo-controlled study of anakinra for 13 weeks, in which improved insulin production and glycemic control associated with decreased CRP and IL-6 levels was reported.86 In the 39 weeks after the 13-week course of anakinra, patients who responded to anakinra used 66% less insulin to obtain the same glycemic control compared with baseline requirements.37 This observation suggests that blocking IL-1β even for a short period of time restores the function of the β cells or possibly allows for partial regeneration of β cells. Several trials that blocked TNFα in type 2 diabetes have succeeded in reducing CRP but did not improve glycemic control. The findings of anakinra therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes have been confirmed with canakinumab, as well as another neutralizing monoclonal antibody to IL-1β.87 The data also provide evidence that short-term blockade of IL-1β restores the function of the β cells or possible regeneration.

The above studies are consistent with the concept that type2 diabetes is a chronic IL-1–mediated disease and could be classified as an autoinflammatory disease in which IL-1β–mediated inflammation progressively destroys the insulin-producing β cells. The IL-1β can come from the β cell itself, from infiltrating macrophages into the islet, or from the adipose tissue stores. A requirement for caspase-1 in regulating IL-1β production from the insulin-producing β cell as well as the adipocyte provides a molecular mechanism. Differentiation of the adipocyte is caspase-1 dependent.108 In diabetic mice, administration of a caspase-1 inhibitor reduces insulin resistance; in mice deficient in caspase-1, there is improved sensitivity to insulin.108 Because type 2 diabetes increases risk of cardiovascular events, blocking IL-1β activity in these patients may also reduce the incidence in myocardial infarction and stroke as reviewed in Dinarello.106

IL-1β as a mediator of cartilage destruction in osteoarthritis

In the joint, IL-1β is the mediator of reduced chondrocyte proteoglycan synthesis, increased synthesis of matrix metalloproteinases, and the release of nitric oxide.109 Mice deficient in IL-1β are protected from inflammation-induced arthritis. The role of IL-1β in the destructive processes of osteoarthritis has also been studied in rabbits, pigs, dogs, and horses. In a placebo-controlled trial of intra-articular anakinra in patients with knee osteoarthritis, there was a clear dose-dependent (50 mg vs 150 mg) reduction in pain and stiffness scores, but the benefit did not extend beyond 1 month.110 The modest reduction may be because of the heterogeneity of the osteoarthritis population in general but also to the short duration of IL-1RI blockade by anakinra.

Does IL-1 contribute to heart failure after myocardial infarction?

ST elevation myocardial infarction has a high risk of death for patients, but patients who survive the acute event progress to chronic heart failure because of a loss of viable myocardium. In a randomized, placebo-controlled trial of patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction, daily anakinra was added to standard of therapy the day after angioplasty and continued for 14 days. Serial imaging and echocardiographic studies were performed over the following 10-14 weeks.111 Left ventricular remodeling was significantly reduced with anakinra treatment and consistent with the reductions in CRP compared with patients receiving 14 days of placebo. After 18 months, 60% of placebo-treated patients had developed stage IV heart failure, whereas there were none in the anakinra-treated patients. These findings are consistent with experimental myocardial infarction in mice in which blocking IL-1β results is a reduction in postinfarction remodeling.72 It remains to be tested whether chronic heart failure in non–postmyocardial infarction patients is reduced by IL-1β blockade.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

I thank Antonio Abbate, Leo Joosten, Mihai Netea, Frank van de Veerdonk, and Jos van der Meer for many helpful suggestions in the preparation of this manuscript. I also thank Kenneth X. Probst for the professional drawings of the figures.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grants AI-15614, CA-04 6934) and Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation (26-2008-893).

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.D. was the single author of this paper.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The author declares no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Charles A. Dinarello, University of Colorado Denver, 12700 E 19th Ave B168, Aurora, CO 80045; e-mail: cdinarello@mac.com.

References

- 1.Dinarello CA. Biological basis for interleukin-1 in disease. Blood. 1996;87(6):2095–2147. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Opal SM, Fisher CJJ, Dhainaut JF, et al. Confirmatory interleukin-1 receptor antagonist trial in severe sepsis: a phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Crit Care Med. 1997;25(7):1115–1124. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199707000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eichacker PQ, Parent C, Kalil A, et al. Risk and the efficacy of antiinflammatory agents: retrospective and confirmatory studies of sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166(9):1197–1205. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200204-302OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lust JA, Lacy MQ, Zeldenrust SR, et al. Induction of a chronic disease state in patients with smoldering or indolent multiple myeloma by targeting interleukin 1beta-induced interleukin 6 production and the myeloma proliferative component. Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(2):114–122. doi: 10.4065/84.2.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Simon A, van der Meer JW. Pathogenesis of familial periodic fever syndromes or hereditary autoinflammatory syndromes. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2007;292(1):R86–98. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00504.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masters SL, Simon A, Aksentijevich I, Kastner DL. Horror autoinflammaticus: the molecular pathophysiology of autoinflammatory disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:621–668. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dinarello CA. Immunological and inflammatory functions of the interleukin-1 family. Ann Rev Immunol. 2009;27:519–550. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber A, Wasiliew P, Kracht M. Interleukin-1 (IL-1) pathway. Sci Signal. 2010;3:cm1. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.3105cm1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carriere V, Roussel L, Ortega N, et al. IL-33, the IL-1-like cytokine ligand for ST2 receptor, is a chromatin-associated nuclear factor in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(1):282–287. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606854104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Werman A, Werman-Venkert R, White R, et al. The precursor form of IL-1alpha is an intracrine proinflammatory activator of transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(8):2434–2439. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308705101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sharma S, Kulk N, Nold MF, et al. The IL-1 family member 7b translocates to the nucleus and down-regulates proinflammatory cytokines. J Immunol. 2008;180(8):5477–5482. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.8.5477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nold MF, Nold-Petry CA, Zepp JA, Palmer BE, Bufler P, Dinarello CA. IL-37 is a fundamental inhibitor of innate immunity. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(11):1014–1022. doi: 10.1038/ni.1944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O'Neill LA. The interleukin-1 receptor/Toll-like receptor superfamily: 10 years of progress. Immunol Rev. 2008;226:10–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2008.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heguy A, Baldari C, Bush K, et al. Internalization and nuclear localization of interleukin 1 are not sufficient for function. Cell Growth Differ. 1991;2(7):311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Meer JWM, Barza M, Wolff SM, Dinarello CA. A low dose of recombinant interleukin 1 protects granulocytopenic mice from lethal gram-negative infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85(5):1620–1623. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenwasser LJ, Dinarello CA, Rosenthal AS. Adherent cell function in murine T-lymphocyte antigen recognition, IV: enhancement of murine T-cell antigen recognition by human leukocytic pyrogen. J Exp Med. 1979;150(3):709–714. doi: 10.1084/jem.150.3.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garlanda C, Anders HJ, Mantovani A. TIR8/SIGIRR: an IL-1R/TLR family member with regulatory functions in inflammation and T cell polarization. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(9):439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smith DE, Lipsky BP, Russell C, et al. A central nervous system-restricted isoform of the interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein modulates neuronal responses to interleukin-1. Immunity. 2009;30(6):817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Neill LA, Bryant CE, Doyle SL. Therapeutic targeting of toll-like receptors for infectious and inflammatory diseases and cancer. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61(2):177–197. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.001073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arslan F, Smeets MB, O'Neill LA, et al. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury is mediated by leukocytic toll-like receptor-2 and reduced by systemic administration of a novel anti-toll-like receptor-2 antibody. Circulation. 2010;121(1):80–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.880187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Asseldonk EJ, Stienstra R, Koenen TB, et al. The effect of the interleukin-1 cytokine family members IL-1F6 and IL-1F8 on adipocyte differentiation. Obesity. 2010;18(11):2234–2236. doi: 10.1038/oby.2010.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Blumberg H, Dinh H, Trueblood ES, et al. Opposing activities of two novel members of the IL-1 ligand family regulate skin inflammation. J Exp Med. 2007;204(11):2603–2614. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Colotta F, Re F, Muzio M, et al. Interleukin-1 type II receptor: a decoy target for IL-1 that is regulated by IL-4. Science. 1993;261(5120):472–475. doi: 10.1126/science.8332913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smeets RL, Joosten LA, Arntz OJ, et al. Soluble interleukin-1 receptor accessory protein ameliorates collagen-induced arthritis by a different mode of action from that of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(7):2202–2211. doi: 10.1002/art.21108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vambutas A, DeVoti J, Goldofsky E, Gordon M, Lesser M, Bonagura V. Alternate splicing of interleukin-1 receptor type II (IL1R2) in vitro correlates with clinical glucocorticoid responsiveness in patients with AIED. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5293. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Akoum A, Al-Akoum M, Lemay A, Maheux R, Leboeuf M. Imbalance in the peritoneal levels of interleukin 1 and its decoy inhibitory receptor type II in endometriosis women with infertility and pelvic pain. Fertil Steril. 2008;89(6):1618–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wald D, Qin J, Zhao Z, et al. SIGIRR, a negative regulator of Toll-like receptor-interleukin 1 receptor signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003;4(9):920–927. doi: 10.1038/ni968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garlanda C, Riva F, Polentarutti N, et al. Intestinal inflammation in mice deficient in Tir8, an inhibitory member of the IL-1 receptor family. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(10):3522–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308680101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bulek K, Swaidani S, Qin J, et al. The essential role of single Ig IL-1 receptor-related molecule/Toll IL-1R8 in regulation of Th2 immune response. J Immunol. 2009;182(5):2601–2609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lech M, Avila-Ferrufino A, Allam R, et al. Resident dendritic cells prevent postischemic acute renal failure by help of single Ig IL-1 receptor-related protein. J Immunol. 2009;183(6):4109–4118. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Melnikov VY, Ecder T, Fantuzzi G, et al. Impaired IL-18 processing protects caspase-1-deficient mice from ischemic acute renal failure. J Clin Invest. 2001;107(9):1145–1152. doi: 10.1172/JCI12089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ferretti M, Casini-Raggi V, Pizarro TT, Eisenberg SP, Nast CC, Cominelli F. Neutralization of endogenous IL-1 receptor antagonist exacerbates and prolongs inflammation in rabbit immune colitis. J Clin Invest. 1994;94(1):449–453. doi: 10.1172/JCI117345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Horai R, Saijo S, Tanioka H, et al. Development of chronic inflammatory arthropathy resembling rheumatoid arthritis in interleukin 1 receptor antagonist-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191(2):313–320. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nicklin MJ, Hughes DE, Barton JL, Ure JM, Duff GW. Arterial inflammation in mice lacking the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist gene. J Exp Med. 2000;191(2):303–312. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Krelin Y, Voronov E, Dotan S, et al. Interleukin-1beta-driven inflammation promotes the development and invasiveness of chemical carcinogen-induced tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67(3):1062–1071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dinarello CA. Why not treat human cancer with interleukin-1 blockade? Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2010;29(2):317–329. doi: 10.1007/s10555-010-9229-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Larsen CM, Faulenbach M, Vaag A, Ehses JA, Donath MY, Mandrup-Poulsen T. Sustained effects of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist treatment in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32(9):1663–1668. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Aksentijevich I, Masters SL, Ferguson PJ, et al. An autoinflammatory disease with deficiency of the interleukin-1-receptor antagonist. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2426–2437. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Reddy S, Jia S, Geoffrey R, et al. An autoinflammatory disease due to homozygous deletion of the IL1RN locus. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(23):2438–2444. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0809568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lachmann HJ, Lowe P, Felix SD, et al. In vivo regulation of interleukin 1beta in patients with cryopyrin-associated periodic syndromes. J Exp Med. 2009;206(5):1029–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20082481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pascual V, Allantaz F, Arce E, Punaro M, Banchereau J. Role of interleukin-1 (IL-1) in the pathogenesis of systemic onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis and clinical response to IL-1 blockade. J Exp Med. 2005;201(9):1479–1486. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Goldbach-Mansky R, Dailey NJ, Canna SW, et al. Neonatal-onset multisystem inflammatory disease responsive to interleukin-1beta inhibition. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):581–592. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gattorno M, Tassi S, Carta S, et al. Pattern of interleukin-1beta secretion in response to lipopolysaccharide and ATP before and after interleukin-1 blockade in patients with CIAS1 mutations. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56(9):3138–3148. doi: 10.1002/art.22842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hoffman HM, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, et al. Prevention of cold-associated acute inflammation in familial cold autoinflammatory syndrome by interleukin-1 receptor antagonist prevents. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17401-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gattorno M, Piccini A, Lasiglie D, et al. The pattern of response to anti-interleukin-1 treatment distinguishes two subsets of patients with systemic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58(5):1505–1515. doi: 10.1002/art.23437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Eiling E, Moller M, Kreiselmaier I, Brasch J, Schwarz T. Schnitzler syndrome: treatment failure to rituximab but response to anakinra. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57(2):361–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.03.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goldbach-Mansky R, Kastner DL. Autoinflammation: the prominent role of IL-1 in monogenic autoinflammatory diseases and implications for common illnesses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1141–1149. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.11.016. quiz 1150–1141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hawkins PN, Lachmann HJ, Aganna E, McDermott MF. Spectrum of clinical features in Muckle-Wells syndrome and response to anakinra. Arthr Rheumat. 2004;50(2):607–612. doi: 10.1002/art.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]