Abstract

Chronic elevation of adenosine, which occurs in the setting of repeated or prolonged tissue injury, can exacerbate cellular dysfunction, suggesting that it may contribute to the pathogenesis of CKD. Here, mice with chronically elevated levels of adenosine, resulting from a deficiency in adenosine deaminase (ADA), developed renal dysfunction and fibrosis. Both the administration of polyethylene glycol–modified ADA to reduce adenosine levels and the inhibition of the A2B adenosine receptor (A2BR) attenuated renal fibrosis and dysfunction. Furthermore, activation of A2BR promoted renal fibrosis in both mice infused with angiotensin II (Ang II) and mice subjected to unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO). These three mouse models shared a similar profile of profibrotic gene expression in kidney tissue, suggesting that they share similar signaling pathways that lead to renal fibrosis. Finally, both genetic and pharmacologic approaches showed that the inflammatory cytokine IL-6 mediates adenosine-induced renal fibrosis downstream of A2BR. Taken together, these data suggest that A2BR-mediated induction of IL-6 contributes to renal fibrogenesis and shows potential therapeutic targets for CKD.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a worldwide public health problem. Twenty-six million American adults have CKD, and it is the ninth leading cause of death in the United States, with poor outcomes and high cost.1 One of the major progressive features seen in CKD is renal fibrosis, a condition representing one of the largest challenges in nephrology because it ends with chronic renal failure (CRF).2–4 The only treatment today for CRF is dialysis or kidney transplantation, thus making CRF one of the most expensive diseases to treat on a per-patient basis.5,6 Reactive treatments rarely restore normal kidney function, and preventive approaches to limit renal fibrosis are lacking because of the poor understanding of the pathogenesis of CKD and its progression to renal fibrosis.

Ischemia and hypoxia have long been considered to be associated with CKD.7,8 One of the best-known signaling molecules to be induced under hypoxic conditions is adenosine.9,10 Adenosine signals through the engagement of G-protein–coupled cell surface receptors A1R, A2AR, A2BR, and A3R11. On one hand, adenosine protects tissues like the brain,12,13 kidney,14 and heart15 from acute ischemic damage, thereby exhibiting chemoprotective properties.16–19 On the other hand, in the setting of repeated or prolonged tissue injury, chronic elevation of adenosine becomes detrimental by promoting or exacerbating tissue injury and dysfunction.9,11 Of note, adenosine is known to be elevated in CKD patients.20 However, the role of chronic elevation of adenosine in the pathogenesis of CKD remains unidentified, and underlying mechanisms for renal fibrosis are poorly studied.

In this study, we report an important role for increased adenosine in CKD in three distinct mouse models: adenosine deaminase (ADA)-deficient mice, a well-accepted animal model to study the consequences of enhanced adenosine signaling, angiotensin II (Ang II)-infused mice and surgically induced unilateral ureteral obstruction (UUO) in mice, two valuable models to study renal fibrosis. In each of these three models, we show that A2BR-mediated IL-6 induction underlies renal fibrosis. These findings immediately offer novel therapeutic strategies for CKD.

RESULTS

Excess Renal Adenosine Contributes to Kidney Dysfunction in ADA−/− mice

To determine in vivo significance of increased adenosine in CKD, we took advantage of ADA-deficient mice (ADA−/−). ADA catalyzes the irreversible deamination of adenosine to produce inosine. As a result of ADA deficiency, we found that the mice accumulate high levels of adenosine in the kidney (Figure 1A). For this reason, ADA−/− mice serve as a valuable animal model to determine the direct role of excess adenosine in pathogenesis of CKD. To determine the contribution of adenosine in ADA−/− mice, enzyme therapy was carried out by the intraperitoneal injection of polyethylene glycol–modified ADA (PEG-ADA), a safe drug successfully used to treat both ADA-deficient humans and mice to lower elevated adenosine levels.21–23 We found that the adenosine levels in kidneys of ADA−/− mice receiving the high dose (HD) regimen of PEG-ADA were similar to those in kidney tissues of the ADA+ controls. However, adenosine levels in kidney tissues of mice on the low dose (LD) regimen of PEG-ADA were significantly higher than those of HD-treated mice and the controls (Figure 1A). We also observed that adenosine levels in the control ADA+ mice with HD PEG-ADA treatment were not significantly reduced below that of control ADA+ mice without PEG-ADA treatment. Thus, PEG-ADA treatment is a useful experimental strategy for controlling the endogenous level of adenosine present in kidney tissue of ADA-deficient mice.

Figure 1.

Increased adenosine in kidney tissues contributes to renal dysfunction and fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice. (A) Modulation of renal adenosine levels in ADA−/− after different dosages of PEG-ADA treatment. Adenosine levels in the kidney tissues were measured by HPLC. (B) Twenty-four-hour urine was collected by metabolic cages, and urinary albumin and creatinine were measured. (C) Histologic analysis of kidneys from control and ADA−/− mice on LD or HD regimens of PEG-ADA. H&E staining and Masson's trichrome staining showed significant vascular damage and fibrosis in glomeruli and interstitial tissues from ADA-deficient mice on the LD regimen. Vascular damage and renal fibrosis were prevented by treatment with a HD regimen of PEG-ADA from birth (HD group). Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Quantitative image analysis showed LD PEG-ADA–treated mice exhibited increased collagen staining, whereas ADA-deficient mice maintained on HD PEG-ADA enzyme therapy from birth have significantly less collagen staining. (E) Collagen content in both control and ADA−/− mice with or without PEG-ADA treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05 versus control mice. **P < 0.05 versus ADA-deficient mice with LD PEG-ADA treatment.

Next, we analyzed renal function in each group by measuring albumin content in 24-hour collected urine, an accurate assessment of renal function. In ADA-deficient mice on LD PEG-ADA treatment, the ratio of urinary albumin to creatinine in 24-hour collected urine was significantly increased compared with controls (Figure 1B). In contrast, HD PEG-ADA treatment significantly attenuated the increased proteinuria seen in LD PEG-ADA–treated ADA−/− mice (Figure 1B). HD PEG-ADA treatment had no significant effect on adenosine levels and kidney function in the control mice. Thus, these findings provide the first in vivo evidence that chronic elevation of kidney adenosine is associated with renal dysfunction in an intact animal.

Increased Renal Adenosine Underlies Renal Damage and Fibrosis in ADA−/− Mice

One of the major features associated with CKD is renal fibrosis. To determine the critical role of persistent accumulated adenosine in the progression of renal fibrosis, histologic studies were conducted to characterize the renal fibrosis in each group of mice described above. Analysis of hematoxylin-eosin (H&E)-stained sections from mice with LD PEG-ADA treatment showed extensive renal damage (Figure 1C). The majority of the glomeruli seen in these mice showed decreased Bowman's space, decreased capillary lumen, and mesangial hypercellularity (Figure 1C, top). Masson's Trichrome staining showed significant fibrosis in both glomeruli and interstitial areas between tubules (Figure 1C, middle and bottom). Quantitative image analysis showed significantly increased collagen staining in kidneys of LD PEG-ADA–treated ADA-deficient mice (Figure 1D). Consistent with histologic studies, total collagen measurements of the kidneys of ADA−/− mice with LD PEG-ADA treatment was significantly elevated (Figure 1E). In contrast, the HD-treated ADA−/− mice showed a significant reduction in renal fibrosis, collagen staining, and total collagen content relative to LD PEG-ADA–treated ADA−/− mice (Figure 1, C–E). Taken together, these results suggest that increased adenosine contributes to renal fibrosis and that chronic reduction of adenosine levels by PEG-ADA enzyme therapy attenuates the development of renal fibrosis in ADA−/− mice.

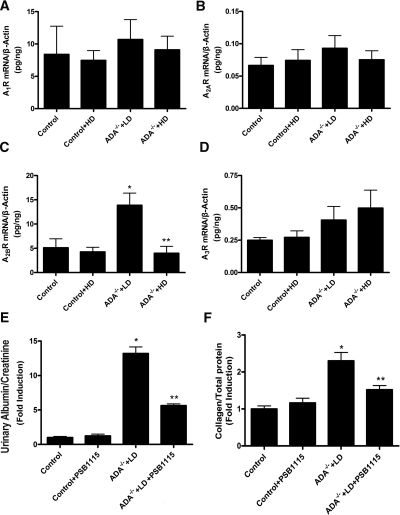

A2BR Activation Contributes to Renal Dysfunction and Fibrosis in ADA−/− Mice

To evaluate the role of adenosine receptor (AR) signaling in adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis seen in ADA−/− mice, we first measured AR expression profiles under LD and HD PEG-ADA therapy protocols. Kidneys from control (ADA+) mice ± HD PEG-ADA treatment were also examined. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that all four ARs were expressed in kidneys of control and ADA−/− mice in the presence or absence of PEG-ADA therapy (Figure 2, A–D). However, only A2BR expression was significantly increased in ADA−/− mice maintained on LD PEG-ADA treatment compared with that of control and ADA−/− mice on the HD regimen of PEG-ADA (Figure 2, A–D). Thus, elevated A2BR expression is associated with elevated adenosine. Because fibroblast cells play an important role in tissue fibrosis, we isolated renal fibroblasts and determined the distribution of adenosine receptor transcripts. The RT-PCR results showed that the A2BR is the predominant AR expressed in the primary wild-type renal fibroblast cells (Supplementary Figure 1). To test the importance of A2BR signaling in renal fibrosis, we injected LD-treated ADA−/− mice with the A2BR antagonist, PSB1115 (1.5mg/kg per day) for 8 weeks. The PSB1115 injections significantly decreased proteinuria and renal fibrosis (collagen content) in these mice (Figure 2, E and F). Collectively, these findings provide in vivo evidence for the important role of A2BR signaling in adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis and dysfunction in ADA−/− mice.

Figure 2.

A2BR activation is responsible for elevated adenosine-induced kidney dysfunction and fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice. (A–D) Four AR mRNA levels in ADA−/− mice. Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of four AR mRNAs in the control and ADA−/− mice with or without PEG-ADA treatment. (E and F) PSB1115 (an A2BR antagonist) treatment attenuated renal dysfunction and fibrosis in ADA−/− mice. Proteinuria (E) and total collagen content of the kidneys (F) of the controls and ADA−/− mice with LD PEG-ADA treatment with or without PSB1115 injection. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). *P < 0.05 versus control mice. **P < 0.05 versus ADA-deficient mice on LD PEG-ADA therapy.

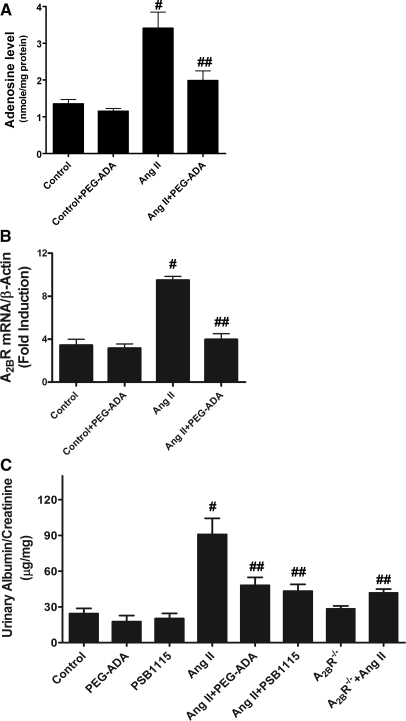

Increased Adenosine Contributes to Renal Dysfunction, Kidney Damage, and Fibrosis in Ang II–Infused Mice via A2BR Signaling

To assess the general significance of high adenosine in the pathophysiology of CKD, we chose to investigate the potential contribution of excess adenosine to the renal fibrosis and dysfunction in Ang II–infused mice, a well-accepted animal model of renal fibrosis.24,25 Adenosine levels in kidneys of Ang II–infused mice were significantly higher than those of controls (Figure 3A). To determine whether the increased adenosine contributes to renal fibrosis and dysfunction in these mice, we tested the effect of PEG-ADA therapy (2.5 units/wk) on these features. Similar to ADA−/− mice, treatment of Ang II–infused mice with PEG-ADA significantly improved kidney function characterized by decreased proteinuria (Figure 3C). Histologic studies showed that chronic Ang II infusion induced remarkable kidney damage in the mice similar to that seen in ADA−/− mice, including decreased Bowman's space, decreased capillary lumen, and mesangial hypercellularity in the glomerular compartment (Figure 4A). Trichrome staining showed remarkable increased collagen staining in both glomeruli and interstitial tissues in Ang II–infused mice compared with controls (Figure 4A). Of significance, PEG-ADA treatment attenuated both kidney damage and renal fibrosis seen in these mice (Figure 4A). Quantitative image analysis showed significantly increased collagen staining in kidneys of Ang II–infused mice (Figure 4B), and PEG-ADA treatment significantly reduced collagen staining in these mice. Consistent with histologic studies, total collagen measurements of kidneys of Ang II–infused mice were significantly elevated, and PEG-ADA treatment significantly reduced Ang II–induced collagen production (Figure 4C). These findings showed a previously unrecognized role for increased adenosine in Ang II–induced kidney fibrosis.

Figure 3.

Elevated adenosine in kidney tissues underlies renal dysfunction in Ang II–infused mice via A2BR signaling. (A) Adenosine levels in the kidneys of control and Ang II–infused mice in the presence or absence of PEG-ADA. (B) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of renal A2BR mRNA levels of control and Ang II–infused mice in the presence or absence of PEG-ADA. (C) Albumin and creatinine concentrations were measured in 24-hour collected mouse urine of the control and Ang II–infused mice with or without PEG-ADA or PSB1115 treatment and A2BR-deficient mice with or without Ang II infusion. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). #P < 0.05 versus control mice. ##P < 0.05 versus Ang II–infused mice without PEG-ADA or PSB1115.

Figure 4.

Increased adenosine is responsible for renal fibrosis in Ang II–infused mice via A2BR signaling. (A) H&E and Trichrome staining showed that Ang II–infused mice without PEG-ADA or PSB1115 treatment showed kidney damage and fibrosis. PEG-ADA enzyme therapy, PSB1115 treatment, or genetic deletion of A2BR significantly reduced vascular damage and fibrosis. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Quantitative image analyses showed Ang II–infused mice exhibited increased collagen staining in the kidney. PEG-ADA enzyme therapy, PSB1115 treatment, or genetic deletion of A2BR significantly decreased collagen staining in the kidney of Ang II–infused mice. (C) Collagen content in the kidney was significantly increased in Ang II–infused mice. PEG-ADA enzyme therapy, PSB1115 therapy, or genetic deletion of A2BR significantly decreased collagen content in the kidneys of Ang II–infused mice. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 6). #P < 0.05 versus control mice. ##P < 0.05 versus Ang II–infused mice without PEG-ADA therapy or PSB1115 treatment.

Similar to ADA-deficient mice, we found that A2BR expression was significantly elevated in the kidneys of Ang II–infused mice and that A2BR expression was reduced by PEG-ADA treatment (Figure 3B). Next, to test whether elevated adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis and dysfunction in Ang II–infused mice is via A2BR signaling, we used both pharmacologic and genetic approaches. We found that PSB1115 treatment or genetic deletion of A2BR significantly decreased Ang II–induced proteinuria (Figure 3C) and renal fibrosis measured by collagen staining (Figure 4, A and B) and total collagen content (Figure 4C), indicating that A2BR signaling contributes to renal dysfunction and fibrosis in Ang II–infused mice. Taken together, these findings provide strong in vivo evidence that increased adenosine, via A2BR signaling, contributes to CKD induced by chronic Ang II infusion.

Elevated Adenosine Contributes to Increased Renal Fibrotic Gene Expression in ADA−/− Mice and Ang II–Infused Mice via A2BR Signaling

To determine the common intermediates for renal fibrosis, we examined the expression of fibrotic mediators in the renal tissue of both ADA−/− mice and Ang II–infused mice. We found that the expression of pro-collagen I, IL-6, and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Pai-1) mRNAs was significantly increased in the kidneys of ADA−/− mice maintained on the LD regimen of PEG-ADA and Ang II–infused mice (Figure 5). Thus, ADA−/− mice and Ang II–infused mice share a similar fibrotic gene expression profile in kidney tissue, suggesting that they share similar signaling pathways for progression to renal fibrosis. Unexpectedly, we found that PEG-ADA treatment significantly decreased elevated profibrotic gene expression in the kidneys of both ADA−/− mice and Ang II–infused mice (Figure 5), These results show that elevated adenosine contributes to increased expression of fibrotic marker genes and plays an important role in renal fibrosis.

Figure 5.

Elevated adenosine in kidney tissues stimulates increased expression of fibrotic marker genes via A2BR activation. (A–C) The expression of fibrotic marker genes in kidney tissue of control and ADA−/− mice maintained on an LD regimen of PEG-ADA enzyme therapy in the presence or absence of PSB1115 or on an HD regimen of PEG-ADA. HD PEG-ADA enzyme therapy for ADA−/− mice or PSB1115 treatment for ADA−/− mice on LD PEG-ADA treatment prevented the increased expression of fibrotic mediators. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 4 to 5). *P < 0.05 versus control mice. **P < 0.05 versus ADA−/− mice with LD PEG-ADA therapy. Collagen I mRNA (A), IL-6 mRNA (B), and Pai-1 mRNA (C) in control and PEG-ADA or PSB1115-treated ADA−/− mice. (D–F) Ang II–infused mice exhibited increased expression of fibrotic mediators in kidney tissue. PEG-ADA, PSB1115 treatment, or genetic deletion of A2BR inhibited the increased expression of fibrotic marker genes in Ang II–infused mice. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 5 to 6). #P < 0.05 versus control mice. ##P < 0.05 versus Ang II–infused mice without PEG-ADA or PSB1115 therapy.

Among the four adenosine receptors, we found that A2BR was the one elevated (Figures 2, A–D, and 3B) and contributed to renal fibrosis in both ADA−/− mice and Ang II–infused mice (Figures 1 and 4). Similar to PEG-ADA treatment, we found that PSB1115 successfully lowered the expression of pro-collagen I, IL-6, and Pai-1 mRNA in the kidney tissues of ADA−/− mice (Figure 5, A–F). Likewise, we found that PSB1115 treatment or genetic deletion of A2BR significantly reduced expression of the fibrotic genes in the kidneys of Ang II–infused mice (Figure 5, A–F). Altogether, these findings indicate that A2BR signaling is responsible for excess adenosine-induced fibrotic gene expression in the kidney.

Genetic Deletion of A2BR Attenuates UUO-Induced Renal Fibrosis

To further determine the general role of A2BR activation in progression of renal fibrosis, we evaluated renal response of wild-type (WT) and A2BR-deficient mice to UUO,26,27 a well-accepted experimental procedure to induce renal fibrosis. We found that the genetic deletion of A2BR in mice reduced UUO-induced vascular damage measured by H&E staining (Figure 6A, top), renal fibrosis measured by collagen staining (Figure 6A, bottom), and quantified by imagine analysis (Figure 6B) and collage production (Figure 6C). Similar to ADA−/− and Ang II–infused mice, pro-collagen I, IL-6, and Pai-1 mRNA levels were significantly increased in the surgically manipulated kidney of WT mice with UUO (Figure 6, D–F). However, genetic deletion of A2BR in mice led to a significant reduction of UUO-induced the fibrotic gene expression (Figure 6, D–F). Thus, these findings provide strong in vivo evidence that A2BR plays an important role in UUO-induced chronic renal fibrosis featured with enhanced fibrotic gene expression.

Figure 6.

Genetic deletion of A2BR attenuates UUO-induced renal fibrosis in mice. (A) H&E staining and Masson's trichrome staining and (B) quantitative image analyses showed significant reduction of UUO-induced vascular damage and fibrosis in glomeruli and interstitial tissues in A2BR-deficient mice compared with WT mice. (C) Quantitative RT-PCR measurement of renal A2BR mRNA levels of sham-operated and UUO-manipulated WT mice. (D) Collagen content in kidneys of WT and A2BR-deficient mice with sham-operation or UUO manipulation. (E–G) Collagen I mRNA (E), IL-6 mRNA, (F), and Pai-1 mRNA (G) in in the kidney of WT and A2BR-deficient with sham-operation or UUO manipulation. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM (n = 5 to 6). $P < 0.05 versus sham-operated WT mice. $$P < 0.05 versus UUO-manipulated WT mice.

IL-6 Is a Common Profibrotic Mediator Responsible for Excess Adenosine-Induced Collagen Production in the Kidney via A2BR Signaling

It is difficult to determine specific factors and signaling pathways involved in adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis in intact animals in vivo. In an effort to decipher specific molecules involved in adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis, we performed experiments using kidney organ cultures. Specifically, we isolated kidneys from WT mice and four adenosine receptor–deficient mice and incubated renal explants in the presence or absence of 5′-N-ethylcarboxamindo-adenosine (NECA), a potent nonmetabolized adenosine analog (20 μM), for 24 hours. We found that NECA directly induced collagen secretion and that genetic deletion of A2BR abolished NECA-induced collagen secretion, suggesting that A2BR is likely the major AR contributing to renal fibrosis by increasing collagen production in the kidney (Figure 7A). Next, we found that NECA increased the IL-6 mRNA expression and pro-collagen I mRNA levels by fourfold and twofold, respectively (Figure 7, B and C). This induction was completely abolished by the A2BR-specific antagonist, MRS1754 (Figure 7, B and C). Consistent with the pharmacologic findings, we found that genetic deletion of A2BR abolished the NECA-induced pro-collagen I and IL-6 mRNA production in the kidney cultures (Figure 7, B and C). Taken together, the pharmacologic and genetic studies showed that A2BR contributes to adenosine-induced fibrotic gene expression in cultured kidneys.

Figure 7.

IL-6 is a common signaling molecule downstream of A2B adenosine receptor activation responsible for excess adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis by increased procollagen production. (A) Analysis of collagen secretion from cultured kidney explants isolated from WT and four adenosine receptor-deficient mice in response to NECA treatment. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. @P < 0.05 versus without treatment (n = 4). @@P < 0.05 versus WT treated with NECA. (B) NECA increased the expression of pro-collagen I mRNA levels in kidney explants, which was completely abolished by the A2BR-specific antagonist, MRS1754, or genetic deletion of A2BR. @P < 0.05 versus without treatment. @@P < 0.05 versus treatment with NECA (n = 4 to 6). (C) NECA-induced IL-6 mRNA expression in kidney explants was inhibited by the A2BR-specific antagonist, MRS1754, or genetic deletion of A2BR. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. @P < 0.05 versus without treatment. @@P < 0.05 versus treatment with NECA (n = 4 to 6). (D) NECA-induced expression of pro-collagen I mRNA levels in kidney explants was abolished by the presence of IL-6 neutralizing antibody but not isotype control antibody. @P < 0.05 versus without treatment. @@P < 0.05 versus treatment with NECA (n = 4 to 6).

IL-6 is a profibrotic mediator28–31 and several studies implicate that IL-6 functions downstream of A2BR activation as a profibrotic mediator of adenosine-induced fibrosis.14,32,33 Because IL-6 gene expression was elevated in the kidney of ADA-deficient mice, Ang II–infused mice, and UUO mice, we speculated that IL-6 is a common intermediate responsible for adenosine-induced pro-collagen expression in kidney tissues seen in these three mouse model of renal fibrosis. To test this hypothesis, we treated the isolated kidney explants with NECA (20 μM) for 24 hours in the presence and absence of neutralizing IL-6 antibody or isotype control antibody. We found that the NECA-induced pro-collagen I mRNA expression was abolished by IL-6 neutralizing antibody but not by isotype control antibody (Figure 7D). These findings provide direct evidence that adenosine-induced IL-6 production contributes to renal fibrosis associated with matrix protein production.

DISCUSSION

A role for adenosine signaling in renal fibrosis in CKD was initially shown by the striking renal fibrosis and dysfunction observed in ADA−/− mice, features similar to those seen in patients with CKD. Our initial finding was extended and confirmed by analysis of Ang II–infused mice and UUO mice, two well-accepted models for renal fibrosis. These findings led us to further discover that IL-6 is a common profibrotic signaling molecule responsible for adenosine-mediated renal fibrosis by induction of procollagen gene expression via A2BR activation. Overall, our analysis of renal fibrosis and kidney dysfunction in these three mouse models provides strong support for the novel view that A2BR-mediated IL-6 signaling contributes to CKD and immediately suggests novel adenosine-based therapies in the disease.

ADA-deficient mice were originally constructed to serve as an animal model of severe combined immunodeficiency, reflecting the most highly studied feature of ADA deficiency in humans. In agreement with expectations, we showed that ADA-deficient mice have a combined immunodeficiency characterized by a reduction in T, B, and NK cells.34 Although immunodeficiency is the most studied feature of ADA deficiency, additional features including hepatocellular impairment, pulmonary insufficiency, neurologic disturbances, kidney pathology, adrenal abnormalities, and skeletal deformities were also observed in ADA−/− mice.35 Most of these features had been described earlier in ADA-deficient children in the years before the advent of enzyme therapy.21–23 Before the advent of PEG-ADA therapy, most ADA-deficient children died within the first 2 years of life.21–23 Analysis of tissues taken at autopsy for eight patients with ADA-deficient severe combined immune deficiency showed numerous nonlymphoid alterations, including renal, adrenal, bone, and cartilage.36 It is noteworthy that the renal findings we describe here for ADA−/− mice are reminiscent of those described earlier for ADA-deficient children, including mesangial sclerosis and hypercellularity.36 Thus, our findings about the important role of elevated adenosine in renal fibrosis in ADA-deficient mice are strongly supported by the renal impairment observed in ADA-deficient children.

The renin angiotensin system is a signaling cascade controlling arterial BP and salt balance.37,38 In both humans and animals with renal dysfunction, circulating Ang II is elevated.39 Intriguingly, adenosine is reported to be elevated in Ang II–infused animals, a well-accepted animal model of CKD.24,25 However, the pathologic role of elevated adenosine in Ang II–induced CKD is unknown. Our initial discovery of the contributory role of elevated adenosine to CKD in ADA-deficient mice led us to further show that increased adenosine also plays an important role in Ang II–induced renal fibrosis and dysfunction in vivo. Of note, we found that renal damage and fibrosis in Ang II–infused mice were significantly but not completely ameliorated by either PEG-ADA or PSB1115 treatment. These findings indicate that excess adenosine contributes directly to renal fibrosis and damage via A2BR activation. However, because renal pathology was not completely inhibited by PEG-ADA or PSB1115, it is also possible that adenosine signaling may not account for all of Ang II–induced renal damage and fibrosis and that some of the detrimental effects of Ang II are independent of elevated adenosine. More importantly, we extended and confirmed the important role of A2BR in renal fibrosis in the UUO mouse model of renal fibrosis. However, unlike ADA deficiency, the Ang II infusion and UUO-induced renal fibrosis mouse models are not characterized by widespread elevation of adenosine (data not shown). Thus, the association of chronic elevated adenosine and A2BR signaling that we report here for Ang II–infused mice and UUO mice is not likely to be related to systemic actions of adenosine but rather local effects of adenosine on kidney fibrosis. Overall, our findings showed adenosine signaling as a novel mechanism for renal fibrosis and kidney dysfunction in general and thereby identified this signaling pathway as a promising therapeutic target for the treatment and prevention of progressive renal fibrosis in CKD.

Here we showed that renal A2BR gene expression is significantly elevated in ADA-deficient mice, Ang II–infused mice, and the UUO model. These findings suggest that there are common causative factors responsible for elevated A2BR expression in these mouse models of renal fibrosis. A2BR expression is known to be elevated under hypoxic conditions.10,40 One of the transcription factors known to be responsible for enhanced A2BR gene expression under hypoxic condition is hypoxia inducible factor (HIF).41 Another transcription factor underlying increased A2BR expression is the cAMP response element binding protein CREB.10,40 Intriguingly, the A2BR is a Gs-coupled receptor that signals through adenylyl cyclase activation, leading to increased cAMP production and the activation of CREB. Thus, activation of A2BR itself functions as a positive feedback to further enhance A2BR gene expression. In view of this regulatory network and our findings that selective elevation of A2BR gene expression was observed in the kidneys of all three models of renal fibrosis, we speculate that hypoxia-mediated HIF stabilization and A2BR-mediated CREB activation function together as a malicious cycle underlying upregulation of A2BR expression in renal fibrosis.

The progressive nature of renal fibrosis seen in ADA-deficient mice, Ang II–infused mice, and the UUO mouse model suggests that adenosine may activate common pathways that maintain or promote the progression from renal damage to kidney fibrosis. All of these animal models are useful in examining common mechanisms and potential therapeutic possibilities by targeting adenosine mediated fibrosis, as well as investigating the cellular signaling pathways involved in the progression, maintenance, and resolution of renal fibrosis. We used both in vivo and in vitro approaches to characterize adenosine levels, adenosine receptors, and signaling pathways involved in renal fibrosis. Using PEG-ADA enzyme therapy, we showed that increased adenosine is an important contributing factor for renal fibrosis in ADA-deficient and Ang II–infused mice. Using an A2BR-specific antagonist, PSB1115, we further showed that activation of the A2BR is a major factor contributing to renal fibrosis and dysfunction in both mouse models. Moreover, using A2BR-deficient mice, we further showed that A2BR is required for UUO-induced renal fibrosis. Of note, we found that all three mouse models share similar expression profiles of mediators of renal fibrosis, such as IL-6, PAI-1, and procollagen, suggesting that renal fibrosis in these three mouse models shares common mechanistic pathways that may be directly or indirectly influenced via A2BR signaling. Using pharmacologic and genetic approaches, we determined that adenosine functions through the A2BR to stimulate procollagen expression. Finally, we showed that IL-6, a potent profibrotic factor, induced by adenosine in the kidney via A2BR activation, contributes to increased procollagen production, a major fibrotic protein. Taken together, our studies showed that adenosine-induced A2BR activation resulted in increased production of IL-6. The resulting increase in IL-6 production contributes to renal fibrosis by stimulating increased procollagen synthesis.

Although prolonged chronic exposure to high levels of adenosine is harmful to tissue, as we showed here for kidneys, the work of Grenz et al.14 showed that A2BR signaling is important for protecting the kidney from acute injury after ischemic preconditioning. Subsequently, Rosenberger et al.42 showed that HIF is responsible for hypoxia-mediated acute inflammatory response (including the induction of IL-6) by induction of netrin-1, which has an anti-inflammatory role via A2BR activation. In contrast, under conditions of chronically elevated adenosine concentrations, we showed here that persistent A2BR activation is detrimental because of the induction of procollagen and other profibrotic mediators via IL-6 signaling. Overall, these findings support an emerging view that, although A2BR signaling is protective during acute injury, prolonged exposure to a high adenosine concentration is detrimental.

There is an enormous knowledge gap in understanding the progression of renal fibrosis in CKD. ADA-deficient mice have served as valuable experimental system to conduct in vivo biochemical screens to identify aspects of mammalian physiology and development that are impaired by abnormally high adenosine signaling. For example, ADA-deficient mice were instrumental in discovering the detrimental role of elevated adenosine in priapism (prolonged penile erection),11 pulmonary disease,35 and now renal fibrosis. After our initial discovery of the role of adenosine signaling in renal fibrosis and function in ADA-deficient mice, we subsequently extended these findings to more widely accepted models of renal fibrosis involving chronic Ang II infusion and UUO mouse models. In all three mouse models studied here, we showed that elevated A2BR-mediated IL-6 signaling underlies the progression of renal fibrosis and renal dysfunction. These findings will not only provide new insight into the pathogenesis of CKD but also open up the possibility of preventing and treating this challenging disease with PEG-ADA enzyme therapy to reduce adenosine levels and A2BR antagonists to block detrimental signaling. Thus, interference with adenosine signaling is likely a novel, effective, and safe mechanism-based strategy to treat and prevent renal fibrosis. If adenosine-induced renal fibrosis can be prevented by PEG-ADA or AR antagonists, the progression of this disease could be halted.

CONCISE METHODS

Mice

ADA-deficient mice were generated and genotyped as described previously.34,35,43 Control mice, designated ADA+, were littermates that were heterozygotes for the null Ada allele. Heterozygous mice do not display a phenotype. All mice were initially on a mixed 129sV/C57BL/6J background and subsequently backcrossed at least 10 generations on the C57BL/6 background. All phenotypic comparisons were performed among littermates. Four adenosine receptor-deficient mutants were also backcrossed at least 10 generations onto the C57BL/6 background and were genotyped according to established protocols.44 Ang II was delivered at a rate of 1.5 mg/kg body weight per day into 12-week-old C57BL/6J mice with osmotic minipumps (Alzet model 2001; Alza, Palo Alto, CA) implanted subcutaneously in the nape of the neck for 2 weeks. All mice were maintained and housed in accordance with National Institute of Health guidelines and with the approval of the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

ADA Enzyme Therapy

PEG-ADA was generated by the covalent modification of purified bovine ADA with activated PEG as described previously.45–47 Different dosages of PEG-ADA were delivered weekly by intraperitoneal injection to reduce adenosine levels. Specifically, the ADA-deficient mice were maintained on high dose (HD) enzyme therapy at 5 U/wk for at least 8 weeks to allow for normal kidney development. At 8 weeks of age, the dose of PEG-ADA for some mice was tapered down over a 4-week period to a low dosage of 0.625 U/wk (2.5 U for 2 weeks, 1.25 U for 2 weeks, and then 0.625 U for the remainder of the experiment). This dosing protocol was designated an low dose (LD) PEG-ADA treatment regimen. Some ADA-deficient mice were treated with HD PEG-ADA (5 U/wk) from birth for 16 weeks. This dosing protocol was designated an HD PEG-ADA treatment regimen. For all experiments, ADA+ mice treated with or without an HD of PEG-ADA at 5 U/wk were used as the controls.

For Ang II–infused mice, a group of mice was injected with 2.5 U PEG-ADA weekly for 2 weeks. This dosing protocol was designated Ang II–infused mice with PEG-ADA treatment regimen (Ang II+PEG-ADA). Other Ang II–treated mice were injected with normal saline for 2 weeks; this group was designated as Ang II without PEG-ADA treatment regimen (Ang II). Age-matched C57Bl/6 mice treated with or without PEG-ADA at 2.5 U/wk were used as the controls.

Treatment with the A2BR Antagonist PSB1115

ADA-deficient mice on LD PEG-ADA treatment with kidney dysfunction and renal fibrosis or WT mice were divided into two groups: one group was injected with 200 μg of PSB1115 (A2B receptor antagonist; Tocris Bioscience, St. Louis, MO) in PBS, daily for 2 weeks. PSB1115 treatment was initiated at 8 weeks of age for ADA-deficient mice that were on the LD PEG-ADA regimen. Note that the LD regimen was achieved by providing HD PEG-ADA for the first 8 weeks of life to allow for normal development, followed by a gradual reduction of PEG-ADA therapy to the LD level over an additional 4-week period. At 8 weeks of age, some of the LD PEG-ADA–treated ADA-deficient mice began to receive daily injections of PSB1115 for an additional 8 weeks. A control group of ADA+ was injected with saline or HD PEG-ADA.

UUO

Twelve- to 16-week-old male mice were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine. Mice were placed on a heating pad at 37°C. The left ureter was identified through a midline incision and ligated with 3-0 sutures at two sites near the renal hilum. Sham-operated mice (the same operation without ureter ligation) were also produced and used as controls. Kidney tissue samples collected at day 14 after UUO were used for histology, collagen content measurements, and a real-time PCR analysis.

Quantification of Kidney Adenosine Levels

Mice were anesthetized, and the kidneys were rapidly removed and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Adenine nucleosides were extracted from frozen kidneys using 0.4 N perchloric acid, and adenosine was separated and quantified using reverse-phase HPLC as described previously.34,43

Urinalysis

Urinary samples were collected for 24 hours using a metabolic cage (Nalgene). We quantified urinary albumin by ELISA (Exocell) and measured urinary creatinine by a picric acid colorimetric assay kit (Exocell). We used the ratio of urinary albumin to urinary creatinine as an index of urinary protein as described.48,49

Histologic Analysis

Mice were anesthetized, and the kidneys were isolated and pressure-infused with 4% paraformaldehyde in PBS and fixed overnight at 4°C. Fixed tissues were rinsed in PBS, dehydrated through graded ethanol washes, and embedded in paraffin. Five-micrometer sections were collected on slides and stained with H&E or Masson's trichrome, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Shardon-Lipshaw).

Morphometric Analysis of the Renal Fibrosis in Masson's Trichrome–Stained Sections

Ten consecutive nonoverlapping fields of a mouse kidney stained with the Trichrome were analyzed. The fibrotic areas stained in light blue were picked up on the digital images using a computerized densitometry (ImagePro Plus, version 6.0; Media Cybernetics, Silver Spring, MD) coupled to a microscope equipped with a digital camera as described.50,51 The percentage of the fibrotic area relative to the whole area of the field was calculated (percent fibrosis area). The average densities of 10 areas per kidney were averaged, the SEM is indicated, and n = 4 to 6 kidneys for each category.

Collagen Quantification

Soluble collagen levels were quantified in kidney tissues using the Sircol collagen assay (Biocolor, Belfast, Ireland) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Total RNA Isolation and Real-Time RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). RNase-free DNase (Invitrogen) was used to eliminate genomic DNA contamination. Transcript levels were quantified using real-time quantitative RT-PCR. Cyber green was used for analysis of α2 (I) procollagen, IL-6, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (Pai-1), and β-actin using the following primers: α2 (I) procollagen, forward, 5′-AGACATGCTCAGCTTTGTGGATAC-3′ and reverse, 5′-CGTACTGATCCCGATTGCAAAT-3′; Pai-1, forward, 5′-AGTGATGGAGCCTTGACAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGGAGGAGTTGCCTTCTCTT-3′; β-actin, forward, 5′- GCTCTGGCTCCTAGCACCAT-3′ and reverse, 5′-CCACCGATCCACACAGAGTAC-3′. Adenosine receptor transcripts were analyzed using Taqman probes, with primer sequences and conditions as described previously.45,46 The sequence for four adenosine receptor were described previously.33

Isolation of Kidneys and Organ Culture Conditions

Kidneys were surgically isolated from WT mice and four adenosine receptor–deficient mice. The isolated kidneys were washed in PBS, minced into 2- to 3-mm3 pieces, suspended in DMEM containing 10% FBS, and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C. After 24 hours in culture, tissues were serum-starved in DMEM without FBS and treated with various drugs. Specifically, NECA (20 μM), a potent nonmetabolized adenosine analog, and MRS1754 (20 μM), a specific A2BR antagonist, were used. IL-6 neutralizing antibody or isotype control antibody (R&D Systems) at a final concentration of 0.5 μg/ml was used. After 24-hour treatment, collagen content in the supernatants and total RNA from tissues were isolated as described above.

Statistical Analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± SEM. Unpaired t tests were applied in two-group analysis. Statistical significance of the difference of multiple groups of mice was assessed by two-way repeated-measures ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni post tests. Data were analyzed for statistical significance using GraphPad Prism 4 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA).48,49 A value of P < 0.05 was considered significant.

DISCLOSURES

None.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grants DK077748 (to Y.X.) and DK083559 (to Y.X.) and China Scholarship Council Grant 2008637068 (to J.W.).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.jasn.org.

Supplemental information for this article is available online at http://www.jasn.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1. Kuroki A, Akizawa T: [Management of chronic kidney disease–preventing the progression of renal disease]. Nippon Rinsho 66: 1735–1740, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wynn TA: Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J Pathol 214: 199–210, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Strutz F, Zeisberg M: Renal fibroblasts and myofibroblasts in chronic kidney disease. J Am Soc Nephrol 17: 2992–2998, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zeisberg M, Strutz F, Muller GA: Renal fibrosis: An update. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 10: 315–320, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bidani AK, Griffin KA: Pathophysiology of hypertensive renal damage: Implications for therapy. Hypertension 44: 595–601, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kim S, Iwao H: Molecular and cellular mechanisms of angiotensin II-mediated cardiovascular and renal diseases. Pharmacol Rev 52: 11–34, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fine LG, Norman JT: Chronic hypoxia as a mechanism of progression of chronic kidney diseases: From hypothesis to novel therapeutics. Kidney Int 74: 867–872, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nangaku M, Fujita T: Activation of the renin-angiotensin system and chronic hypoxia of the kidney. Hypertens Res 31: 175–184, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fredholm BB: Adenosine, an endogenous distress signal, modulates tissue damage and repair. Cell Death Differ 14: 1315–1323, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Eltzschig HK, Thompson LF, Karhausen J, Cotta RJ, Ibla JC, Robson SC, Colgan SP: Endogenous adenosine produced during hypoxia attenuates neutrophil accumulation: Coordination by extracellular nucleotide metabolism. Blood 104: 3986–3992, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mi T, Abbasi S, Zhang H, Uray K, Chunn JL, Xia LW, Molina JG, Weisbrodt NW, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Xia Y: Excess adenosine in murine penile erectile tissues contributes to priapism via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. J Clin Invest 118: 1491–1501, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rudolphi KA, Schubert P, Parkinson FE, Fredholm BB: Adenosine and brain ischemia. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 4: 346–369, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Schubert P, Rudolphi KA, Fredholm BB, Nakamura Y: Modulation of nerve and glial function by adenosine: Rrole in the development of ischemic damage. Int J Biochem 26: 1227–1236, 1994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Grenz A, Osswald H, Eckle T, Yang D, Zhang H, Tran ZV, Klingel K, Ravid K, Elzschig HK: The reno-vascular A2B adenosine receptor protects the kidney from ischemia. PLoS Med 5: e137, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lasley RD, Rhee JW, Van Wylen DG, Mentzer RM, Jr: Adenosine A1 receptor mediated protection of the globally ischemic isolated rat heart. J Molec Cell Cardiol 22: 39–47, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fishman P, Bar-Yehuda S, Farbstein T, Barer F, Ohana G: Adenosine acts as a chemoprotective agent by stimulating G-CSF production: A role for A1 and A3 adenosine receptors. J Cell Physiol 183: 393–398, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Linden J: Adenosine in tissue protection and tissue regeneration. Mol Pharmacol 67: 1385–1387, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lu B, Rajakumar SV, Robson SC, Lee EK, Crikis S, d'Apice AJ, Cowan PJ, Dwyer KM: The impact of purinergic signaling on renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Transplantation 86: 1707–1712, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hatfield S, Belikoff B, Lukashev D, Sitkovsky M, Ohta A: The antihypoxia-adenosinergic pathogenesis as a result of collateral damage by overactive immune cells. J Leukoc Biol 86: 545–548, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Vallon V, Muhlbauer B, Osswald H: Adenosine and kidney function. Physiol Rev 86: 901–940, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hershfield MS: PEG-ADA replacement therapy for adenosine deaminase deficiency: An update after 8.5 years. Clin Immunol Immunopathol 76: S228–S232, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Hershfield MS: PEG-ADA: An alternative to haploidentical bone marrow transplantation and an adjunct to gene therapy for adenosine deaminase deficiency. Hum Mutat 5: 107–112, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hershfield MS: New insights into adenosine-receptor-mediated immunosuppression and the role of adenosine in causing the immunodeficiency associated with adenosine deaminase deficiency. Eur J Immunol 35: 25–30, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wolf G: Angiotensin II is involved in the progression of renal disease: Importance of non-hemodynamic mechanisms. Nephrologie 19: 451–456, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Guo G, et al. : Contributions of angiotensin II and tumor necrosis factor-alpha to the development of renal fibrosis. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 280: F777–F785, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Klahr S, Morrissey JJ: The role of growth factors, cytokines, and vasoactive compounds in obstructive nephropathy. Semin Nephrol 18: 622–632, 1998 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klahr S: Mechanisms of progression of chronic renal damage. J Nephrol 12[Suppl 2]: S53–S62, 1999 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Carrero JJ, Park SH, Axelsson J, Lindholm B, Stenvinkel P: Cytokines, atherogenesis, and hypercatabolism in chronic kidney disease: A dreadful triad. Semin Dialysis 22: 381–386, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pachaly MA, do Nascimento MM, Sulliman ME, Hayashi SY, Rielia MC, Manfro RC, Stenvinkel P, Lindholm B: Interleukin-6 is a better predictor of mortality as compared to C-reactive protein, homocysteine, pentosidine and advanced oxidation protein products in hemodialysis patients. Blood Purif 26: 204–210, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Stenvinkel P, Ketteler M, Johnson RJ, Lindholm B, Pecoits-Filho R, Riella M, Heimburger O, Cederholm T, Girndt M: IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-alpha: Central factors in the altered cytokine network of uremia–the good, the bad, and the ugly. Kidney Int 67: 1216–1233, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pecoits-Filho R, Barany P, Lindholm B, Heimburger O, Stenvinkel P: Interleukin-6 is an independent predictor of mortality in patients starting dialysis treatment. Nephrol Dial Transplant 17: 1684–1688, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Sun CX, Zhong H, Mohsenin A, Morschl E, Chunn JL, Molina JG, Belardinelli L, Zeng D, Blackburn MR: Role of A2B adenosine receptor signaling in adenosine-dependent pulmonary inflammation and injury. J Clin Invest 116: 2173–2182, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wen J, Jiang X, Dai Y, Zhang Y, Tang Y, Sun H, Mi T, Phatarpekar PV, Kellems RE, Blackburn MR, Xia Y: Increased adenosine contributes to penile fibrosis, a dangerous feature of priapism, via A2B adenosine receptor signaling. FASEB J 24: 740–749, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Blackburn MR, Datta SK, Kellems RE: Adenosine deaminase-deficient mice generated using a two-stage genetic engineering strategy exhibit a combined immunodeficiency. J Biol Chem 273: 5093–5100, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Blackburn MR, Kellems RE: Adenosine deaminase deficiency: metabolic basis of immune deficiency and pulmonary inflammation. Adv Immunol 86: 1–41, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ratech H, Greco MA, Gallo G, Rimoin DL, Kamino H, Hirschhorn R: Pathologic findings in adenosine deaminase-deficient severe combined immunodeficiency. I. Kidney, adrenal, and chondro-osseous tissue alterations. Am J Pathol 120: 157–169, 1985 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Covic A, Gusbeth-Tatomir P: The role of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system in renal artery stenosis, renovascular hypertension, and ischemic nephropathy: Diagnostic implications. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 52: 204–208, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mori T, Cowley AW, Jr, Ito S: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic strategies of chronic renal injury: Physiological role of angiotensin II-induced oxidative stress in renal medulla. J Pharmacol Sci 100: 2–8, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Steinhausen M, Endlich K, Wiegman DL: Glomerular blood flow. Kidney Int 38: 769–784, 1990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Furuta GT, Leonard MO, Jacobson KA, Enjyoji K, Robson SC, Colgan SP: Coordinated adenine nucleotide phosphohydrolysis and nucleoside signaling in posthypoxic endothelium: Role of ectonucleotidases and adenosine A2B receptors. J Exp Med 198: 783–796, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kong T, Westerman KA, Faigle M, Eltzschig HK, Colgan SP: HIF-dependent induction of adenosine A2B receptor in hypoxia. FASEB J 20: 2242–2250, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rosenberger P, Schwab JM, Mirakaj V, Masekowsky E, Mager A, Morote-Garcia JC, Unertl K, Elzschig HK: Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat Immunol 10: 195–202, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blackburn MR, Datta SK, Wakamiya M, Vartabedian BS, Kellems RE: Metabolic and immunologic consequences of limited adenosine deaminase expression in mice. J Biol Chem 271: 15203–15210, 1996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chen JF, Huang Z, Ma J, Zhu J, Moratalia R, Standaert D, Moskowitz MA, Fink JS, Schwarzschild MA: A(2A) adenosine receptor deficiency attenuates brain injury induced by transient focal ischemia in mice. J Neurosci 19: 9192–9200, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chunn JL, Mohsenin A, Young HW, Lee CG, Elias JA, Kellems RE, Balckburn MR: Partially adenosine deaminase-deficient mice develop pulmonary fibrosis in association with adenosine elevations. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 290: L579–L587, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Chunn JL, Molina JG, Mi T, Xia Y, Kellems RE, Balackburn MR: Adenosine-dependent pulmonary fibrosis in adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Immunol 175: 1937–1946, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Chunn JL, Young HW, Banerjee SK, Colasurdo GN, Blackburn MR: Adenosine-dependent airway inflammation and hyperresponsiveness in partially adenosine deaminase-deficient mice. J Immunol 167: 4676–4685, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Zhou CC, Irani RA, Zhang Y, Blackwell SC, Mi T, Wen J, Shelat H, Geng YJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y: Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibody-mediated tumor necrosis factor-alpha induction contributes to increased soluble endoglin production in preeclampsia. Circulation 121: 436–444, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Zhou CC, Zhang Y, Irani RA, Zhang H, Mi T, Popek EJ, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y: Angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies induce pre-eclampsia in pregnant mice. Nat Med 14: 855–862, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Irani RA, Zhang Y, Blackwell SC, Zhou CC, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y: The detrimental role of angiotensin receptor agonistic autoantibodies in intrauterine growth restriction seen in preeclampsia. J Exp Med 206: 2809–2822, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Irani RA, Zhang Y, Zhou CC, Blackwell SC, Hicks MJ, Ramin SM, Kellems RE, Xia Y: Autoantibody-mediated angiotensin receptor activation contributes to preeclampsia through tumor necrosis factor-alpha signaling. Hypertension 55: 1246–1253, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]