Abstract

Background

MRI studies, including recent diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) studies, have shown corpus callosum abnormalities in children prenatally exposed to alcohol, especially in the posterior regions. These abnormalities appear across the range of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD). Several studies have demonstrated cognitive correlates of callosal abnormalities in FASD including deficits in visual-motor skill, verbal learning, and executive functioning. The goal of this study was to determine if inter-hemispheric structural connectivity abnormalities in FASD are associated with disrupted inter-hemispheric functional connectivity and disrupted cognition.

Methods

Twenty-one children with FASD and 23 matched controls underwent a six minute resting-state functional MRI scan as well as anatomical imaging and DTI. Using a semiautomated method, we parsed the corpus callosum and delineated seven inter-hemispheric white matter tracts with DTI tractography. Cortical regions of interest (ROIs) at the distal ends of these tracts were identified. Right-left correlations in resting fMRI signal were computed for these sets of ROIs and group comparisons were done. Correlations with facial dysmorphology, cognition, and DTI measures were computed.

Results

A significant group difference in inter-hemispheric functional connectivity was seen in a posterior set of ROIs, the para-central region. Children with FASD had functional connectivity that was 12% lower than controls in this region. Sub-group analyses were not possible due to small sample size, but the data suggest that there were effects across the FASD spectrum. No significant association with facial dysmorphology was found. Para-central functional connectivity was significantly correlated with DTI mean diffusivity, a measure of microstructural integrity, in posterior callosal tracts in controls but not in FASD. Significant correlations were seen between these structural and functional measures and Wechsler perceptual reasoning ability.

Conclusions

Inter-hemispheric functional connectivity disturbances were observed in children with FASD relative to controls. The disruption was measured in medial parietal regions (para-central) that are connected by posterior callosal fiber projections. We have previously shown microstructural abnormalities in these same posterior callosal regions and the current study suggests a possible relationship between the two. These measures have clinical relevance as they are associated with cognitive functioning.

Keywords: Fetal alcohol (FAS, FASD); Brain; functional MRI (fMRI); resting-state, connectivity; neuropsychological

INTRODUCTION

Prenatal alcohol exposure represents a major public health problem that results in permanent neurodevelopmental abnormalities for a very large number of individuals. The incidence of full Fetal Alcohol Syndrome (FAS) is approximately 0.1% of the population, but a much larger group of individuals experiences the damaging effects of prenatal alcohol exposure (Abel, 1995). Epidemiologic data suggest that the incidence of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders (FASD) is as high as 0.9% of the population (Lupton et al., 2004; May and Gossage, 2001; Sampson et al., 1997).

Neurocognitive deficits are a hallmark of FASD and studies have clearly shown that prenatal alcohol exposure is associated with deficits across a wide range of cognitive domains including intelligence, attention, executive functioning, memory, visual-spatial skill, motor skill, processing speed, adaptive functioning, and social skill (Coles et al., 1991; Janzen et al., 1995; Kodituwakku et al., 2006; Korkman et al., 2003; LaDue et al., 1992; Mattson et al., 1999; Mattson and Riley, 1998; Mattson et al., 1996; Streissguth et al., 1991; Streissguth et al., 1994; Thomas et al., 1998; Whaley et al., 2001). Furthermore, these problems occur across the FASD spectrum as evidenced by studies showing cognitive deficits in children who were prenatally exposed to alcohol, regardless of whether they met the full diagnostic criteria for FAS (Larroque and Kaminski, 1998; Mattson et al., 1997; Olson et al., 1997; Testa et al., 2003).

An accumulating body of evidence from pathologic and MRI studies suggests that numerous brain structures are vulnerable to prenatal alcohol exposure. Individuals with FASD have been shown to have smaller brains overall, including differences in both white matter and grey matter volumes (Archibald et al., 2001; Clarren, 1986; Clarren et al., 1978; Sowell et al., 2002b; Swayze et al., 1997; Wozniak et al., 2006). Some studies suggest that white matter may be disproportionately impacted in FASD (Archibald et al., 2001; Lebel et al., 2008). Corpus callosum abnormalities highlight the vulnerability of white matter in FASD. Agenesis of the callosum has been noted as have less severe alterations: thinning, hypoplasia, & partial agenesis (Autti-Ramo et al., 2002; Clarren and Smith, 1978; Riley et al., 1995; Swayze et al., 1997). Posterior callosum, including splenium, is most often affected (Riley et al., 1995; Sowell et al., 2001a; Wozniak et al., 2009). Splenium displacement appears to be common in FASD (Bookstein et al., 2007) and it predicts verbal learning deficits (Sowell et al., 2001a). Corpus callosum shape is also related to motor and executive functioning in FASD (Bookstein et al., 2002a; Bookstein et al., 2001). DTI studies have shown that posterior callosum microstructural abnormalities are associated with poor visual-motor performance (Sowell et al., 2008) and poor perceptual reasoning ability (Wozniak et al., 2009).

Having identified microstructural abnormalities in inter-hemispheric connectivity in FASD (Wozniak et al., 2006; Wozniak et al., 2009), we next sought to investigate whether inter-hemispheric functional connectivity is also disturbed in FASD. We were particularly interested in determining whether inter-hemispheric functional connectivity abnormalities are evident in those regions of the brain known to have underlying white matter microstructural abnormalities. Functional connectivity has been defined as the “temporal correlation between spatially remote neurophysical events” (Friston et al., 1993). Most functional connectivity studies measure brain activity during several minutes of rest and then apply correlation techniques to “map” networks in the brain based on regionally synchronized activity (Biswal et al., 1995). For example, using this innovative approach, Raichle et al. (2001) mapped a “default mode network” - a collection of brain regions not previously known to operate as a “system”, and have shown that resting state networks are involved in non-task, off-line activities, perhaps including memory consolidation and planning (Raichle and Snyder, 2007). The brain’s ability to coordinate itself in this fashion follows a developmental trajectory, reflected in increased functional network connectivity with age in children and young adults (Fair et al., 2008; Kelly et al., 2009). Using a number of different methods, functional connectivity has been shown to be abnormal in neurodevelopmental disorders including Autism (Broyd et al., 2008; Greicius, 2008) but there are no published studies in FASD. Inter-hemispheric connectivity has specifically been examined in a few studies. Loss of inter-hemispheric functional connectivity has been shown in surgical severing of the callosum (Johnston et al., 2008) in epilepsy patients. Corpus callosum agenesis has also been shown to be associated with loss of inter-hemispheric functional connectivity (Quigley et al., 2003). Recently, studies have begun to demonstrate clear relationships between resting state functional connectivity and DTI measures of structural connectivity (Skudlarski et al., 2008).

For the current investigation, we hypothesized that inter-hemispheric functional connectivity would be disturbed in children with FASD and that the disturbance would be regionally specific to those areas of cortex connected by posterior corpus callosum fibers. We also hypothesized that measures of structural connectivity and functional connectivity in these regions would be associated with cognitive processes involving visual integration and visual reasoning. This study used a modified version of the semi-automated corpus callosum parcellation and tractography method that we developed and tested in Wozniak et al. (2009). This study builds on that work by simultaneously evaluating inter-hemispheric functional connectivity using a novel, straightforward method of correlating brain activity in right and left homologous cortical regions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

Participants were between the ages of 10 and 17. A total of 21 children with FASD were recruited from the University of Minnesota’s Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders Clinic. Twenty-three control subjects with no prenatal alcohol exposure were recruited from the Twin Cities metropolitan area via advertisements on public websites, on bulletin boards, in stores, laundromats, libraries and other public buildings across a diverse range of neighborhoods, including a wide range of socioeconomic levels. As part of their clinic visit, all participants with FASD were seen by a pediatric psychologist and a developmental pediatrician with formal training and more than twelve years experience using the 4-Digit Diagnostic System (Astley and Clarren, 2000). MRI scans were completed within one year of the neurocognitive evaluation.

Astley and Clarren’s diagnostic system classifies individuals on four criteria: 1) growth, 2) facial characteristics, 3) Central Nervous System (CNS) status, and 4) alcohol exposure. Full-criteria FAS is defined by growth deficiency (<10th percentile height and weight or <3rd percentile on either), severe facial abnormalities (abnormally thin upper lip, abnormally smooth philtrum, and palpebral fissure width more than 2 SD below the mean), moderate or severe CNS impairment (microcephaly and/or cognitive deficits more than 2 SD from mean in three or more domains), and confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure. Partial FAS (pFAS) is characterized by at least moderate facial abnormalities (one or more of: abnormally thin upper lip, abnormally smooth philtrum, or palpebral fissure width more than 2 SD below the mean), moderate or severe CNS impairment, and confirmed prenatal alcohol exposure. Growth deficiency is not required for pFAS. Static Encephalopathy is characterized by moderate or severe CNS impairment. Sentinel Physical Findings (dysmorphic facial features and growth deficiency) may or may not be present along with Static Encephalopathy. For pFAS, confirmed maternal alcohol consumption is required at either a “high risk” level (estimated >100 mg/dl blood alcohol concentration weekly, early in pregnancy) or a lower level that is still associated with “some risk.” For Static Encephalopathy / Sentinel Physical Findings, maternal alcohol exposure may be either confirmed as heavy (see examples below) or may be only suspected - but only when facial dysmorphology is also present.

Eighteen out of 21 participants with FASD had confirmed documentation of prenatal alcohol exposure (Astley and Clarren rank 3 or 4, corresponding to a diagnosis of FAS, pFAS, sentinel physical finding(s)/static encephalopathy, static encephalopathy or sentinel physical finding(s)/neurobehavioral disorder). Confirmed exposure included self-report by the biological parent or social service records indicating heavy maternal use during pregnancy. As an example, a rank of 4 was assigned if the mother’s alcohol use was documented specifically as daily and chronic or consisting of weekly heavy binges during pregnancy. In contrast, rank 3 was assigned when heavy maternal alcohol consumption was documented but was neither daily nor were binge episodes weekly. Documentation of several heavy binge drinking episodes during pregnancy resulted in assigning a rank of 3. Potential participants were excluded if only minimal alcohol use was documented (for example, a single drink consumed on several occasions during pregnancy). In three cases, maternal alcohol use was suspected by a third party but was neither self-reported by the biological mother nor formally observed and documented by a third party. These 3 subjects were included because they had suspected exposure along with each of the three other criteria: growth deficiency (rank 3 or 4), facial dysmorphology (rank 2, 3, or 4), and evidence of cognitive dysfunction (3 or 4). Subjects with FASD were excluded for other prenatal drug exposure (except nicotine and caffeine), although cocaine use by the mother was known in two cases. In four cases, there was suspected maternal marijuana use during pregnancy but no information about the extent of the use. In all four of these cases, alcohol was the predominant substance of abuse and alcohol use was reported to have been extensive during pregnancy.

Additional exclusion criteria for all subjects (FASD and controls) were the presence of another developmental disorder (ex. Autism, Down Syndrome), very low birthweight (<1500 grams), neurological disorder, traumatic brain injury, other medical condition affecting the brain, substance use in the participant themselves, or contraindications to safe MRI scanning. Control subjects were excluded for any parent-reported history of prenatal substance exposure, substance use in the participant themselves, and for history of psychiatric disorder or learning disability. We observed significant psychiatric co-morbidity in our participants with FASD, as has been extensively reported in the literature (O'Connor et al., 2002; Steinhausen et al., 1993; Streissguth et al., 2004; Streissguth and O'Malley, 2000). Participants with FASD were not excluded for psychiatric co-morbidity. The following co-morbid diagnoses were present in the group with FASD as established by full clinical evaluation: Attention-Deficit / Hyperactivity Disorder (76%); Oppositional Defiant Disorder (29%); Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (24%); Disruptive Behavior Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (24%); Reactive Attachment Disorder (10%); Developmental Communication Disorder (10%); Major Depressive Disorder (5%); Anxiety Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (5%). Table 1 contains additional subject characteristics.

Table 1.

Subject characteristics for FASD and control groups.

| N(%) or mean ± sd | FASD (n =21 ) | Control (n =23) | Statistical Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at MRI scan | 13.9 ± 2.3 yrs. | 12.8 ± 2.4 yrs. | t=1.52, p=.14 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 12 (27%) | 13 (30%) | |

| Female | 9 (20%) | 10 (23%) | χ2=.002, p=.967 |

| Handedness | |||

| Right | 20 (45%) | 20(45%) | |

| Left | 3 (7%) | 1(3%) | χ2=.911, p=.340 |

| Facial Features (FASD only) | |||

| (Astley & Clarren ratings) | |||

| 1. None | 4 (19%) | - | - |

| 2. Mild | 4 (19%) | - | - |

| 3. Moderate | 5 (24%) | - | - |

| 4. Severe | 8 (38%) | - | - |

| Alcohol Exposure (FASD only) | |||

| (Astley & Clarren ratings) | |||

| 1. No Risk | 0 (0%) | - | - |

| 2. Unknown Risk | 3 (14%) | - | - |

| 3. Some Risk | 13 (62%) | - | - |

| 4. High Risk | 5 (24%) | - | - |

| FASD Category (Astley & Clarren) | |||

| “Other FASD” including Sentinel Physical | |||

| Findings & Static Encephalopathy | 9 (43%) | - | - |

| Partial FAS | 11 (52%) | - | - |

| FAS | 1 (5%) | - | - |

| Intellectual Functioning | |||

| Verbal Comprehension Index | 88 ± 10.4 | 113 ± 12.7 | t=7.25, p<.001 |

| Perceptual Reasoning Index | 93 ± 12.3 | 117 ± 12.6 | t=6.40, p<.001 |

| Working Memory Index | 88 ±16.3 | 112 ± 11.7 | t=5.73, p<.001 |

| Processing Speed Index | 86 ± 16.2 | 103 ± 13.2 | t=3,88, p<.001 |

All procedures were approved by the University of Minnesota’s Research Subjects’ Protection Program and all participants underwent a comprehensive informed consent procedure. Participants were compensated with gift cards for their time.

Neuropsychological Evaluation

Participants were administered either the Wechsler Intelligence Scales for Children – Fourth Edition (WISC-IV) (Wechsler, 2003) (ages 10–16) or the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scales – Third Edition (WAIS-III) (Wechsler, 1997) (age 17) by a research assistant, psychometrist, or doctoral-level psychology trainee. Most of the participants with FASD were administered the test as part of their evaluation in the FASD Clinic. Control subjects were administered the IQ test at the time of the MRI.

MRI acquisition procedures

Subjects were scanned using a Siemens 3T TIM Trio MRI scanner with a 12-channel parallel array head coil. The imaging sequence and parameters for each scan are listed in Table 2. In all cases, the MRI scan was performed within one year of the IQ test. Participants were not sedated for the MRI scan nor were their usual medications modified for purposes of the MRI scan.

Table 2.

MRI sequence and parameters.

| Sequence | Imaging Parameters | Purpose | Time |

|---|---|---|---|

| Scout | 3 plane localizer | Positioning | 1 min |

| T1-weighted MPRAGE | TR=2350ms, TE=3.65ms, TI=1100ms, 224 slices, voxel size= 1×1×1mm, FOV=256mm, flip angle=7 degrees, GRAPPA 2. | Segmentation & cortical parcellation | 5 min |

| Diffusion weighted (DTI) | TR=8500ms, TE=90ms, 64 slices, voxel size=2×2×2mm, FOV=256mm, GRAPPA ;2, 30 volumes with b=1000 s/mm2 & 6 with b=0 s/mm2. |

Computation of the diffusion tensor | 6 min |

| DTI Field-map | Positioned to match DTI, 64 slices, voxel size=2×2×2mm, FOV=256mm ;TR=700ms, TE=4.62ms / 7.08ms, flip angle=90 deg. |

Correction of geometric distortions for DTI | 3 min |

| Resting fMRI | TR=2000 ms, TE=30ms, 34 interleaved slices, no skip, voxel size=3.45×3.45×4.0mm, FOV=220mm, flip angle=77 deg., 180 measures. | Measurement of BOLD signal | 6 min |

| fMRI Field map | Positioned to match fMRI, 34 slices, voxel size=3.45×3.45×4.0mm, FOV=220mm ;TR=700ms, TE=1.91ms / 3.37ms, flip angle=90 deg. |

Correction for geometric distortions for fMRI | 1 min |

MRI post-processing

Several tools from the FMRIB’s Software Library (FSL) version 4.0.1 were used in the post-processing (Smith et al., 2004; Woolrich et al., 2009).

T1 processing

Cortical reconstruction and segmentation were applied to the 1mm isotropic volume using FreeSurfer (Dale et al., 1999). Processing included removal of non-brain tissue, automated Talairach transformation, segmentation, intensity normalization, tessellation of the grey matter / white matter boundary, topology correction, surface deformation, and automated parcellation. FreeSurfer morphometric procedures have high test-retest reliability (Han et al., 2006). Each subject’s data was visually inspected by a trained operator (C.J.B. or M.L.N.) to ensure accuracy of the cortical parcellation. Hand editing was not employed. Cortical grey and white matter ROIs from FreeSurfer were aligned to both the fMRI and DTI data using a linear registration (FLIRT: FMRIB’s Linear Image Registration Tool) (Jenkinson and Smith, 2001).

DTI processing

Eddy current distortion was corrected with FLIRT (Jenkinson and Smith, 2001). Geometric distortions caused by susceptibility-induced field inhomogeneities were corrected using the DTI field map data (FUGUE: FMRIB’s Utility for Geometrically Unwarping EPIs) (Smith et al., 2004). The tensor was computed with FDT (FMRIB’s Diffusion Toolbox) (Behrens et al., 2003). Mean Diffusivity (MD) (mean of the three eigenvalues), and Fractional Anisotropy (FA) were derived.

Resting fMRI processing

Brain extraction (BET) (Smith, 2002) and motion correction (MCFLIRT) (Jenkinson et al., 2002) were performed. Grand mean intensity normalization was applied. Geometric distortions caused by susceptibility-induced magnetic field inhomogeneities were corrected with FUGUE using the fMRI field map (Smith et al., 2004). These data were corrected for slice-timing, then a .01 to .08 Hz. temporal bandpass filter was applied and the first three time points were dropped to allow for magnetization stabilization (FEAT: FMRIB’s Expert Analysis Tool).

DTI tractography method

We applied a slightly modified version of the semi-automated corpus callosum tractography method that is described in detail in a previous paper (Wozniak et al., 2009). Briefly, an operator manually defined a rectangular mask outlining the corpus callosum and the border between the genu and the rostrum at the midline on the FMRIB58 FA map. The rectangular mask was warped into the native space of each subject and was then automatically partitioned into seven regions based on delineations from Witelson (1989). These rectangular regions were then segmented to fit the callosum using the x-component of the primary eigenvector. This analysis included the seventh region (rostrum) which was not included in the Wozniak et al. (2009) paper. For the current analysis, FNIRT (FMRIB’s Nonlinear Image Registration Tool) was used instead of the FLIRT linear registration tool. The new analysis also used the FMRIB58 1mm isotropic FA map as a template instead of the MNI template brain that was used in Wozniak et al. (2009). The FMRIB brain was rotated to align it to the corpus callosum. The seven regions were then used as seed points for probabilistic tractography (FMRIB’s Probtrack) of tracts projecting into right and left hemispheres. From anterior to posterior, the tracts were: 1. Rostrum; 2 Genu; 3. Rostral Body; 4. Anterior Mid-body; 5. Posterior Mid-body; 6. Isthmus; and 7. Splenium. Mean FA and MD were computed for each of these seven inter-hemispheric tracts. The reliability of this method is high, as described in Wozniak et al. (2009).

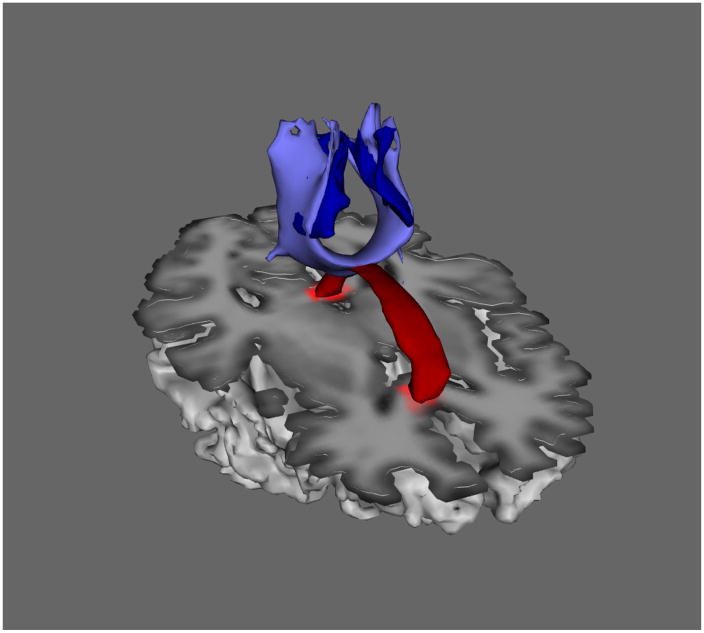

Functional connectivity method

A multimodal functional connectivity analysis was conducted with the following goals: 1. determine which bilateral cortical regions are interconnected by the seven inter-hemispheric tracts, 2. ascertain whether these interconnected regions exhibit altered functional connectivity. To accomplish goal 1, we first determined which bilateral cortical regions were at the distal ends of each of the corpus callosum tracts. FreeSurfer processing was performed on the T1-weighted images to parcellate the cortex into 35 cortical grey and associated white matter ROIs per hemisphere. The FreeSurfer parcellation was aligned to the FA map, overlap between each of the seven corpus callosum tracts and each right and left FreeSurfer white matter ROI was determined for every subject, and the overlap (percentage of voxels in common between each tract and FreeSurfer ROI) was averaged across the entire study population because there were not significant group differences in overlap. Using this method, four sets of cortical ROIs (right and left) were found to have the most significant overlap with the corpus callosum tracts: 1. Medial-orbitofrontal; 2. Superior-frontal; 3. Para-central; and 4. Pre-cuneus. Table 3 shows the relationship between corpus callosum tracts and FreeSurfer ROIs. Also included for reference are known fiber projections from the callosum based on anatomical studies (Aboitiz et al., 1992). Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between one set of cortical ROIs and the corresponding corpus callosum tract.

Table 3.

Corpus callosum regions of interest (ROIs), corresponding cortical regions to which fibers project, and associated FreeSurfer grey matter ROIs at the distal ends of the white matter tracts.

| Midline Corpus Callosum Region (Witelson, 1989) | Cortical region to which fibers project according to anatomical studies (Aboitz et al, 1992; Witelson, 1989) | FreeSurfer grey matter ROIs at the distal end of the white matter tracts (Dale et al., 1999) |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Rostrum | Caudal, orbital-prefrontal, & inferior pre-motor | Medial Orbitofrontal |

| 2. Genu | Prefrontal | Medial Orbitofrontal |

| 3. Rostral Body | Pre-motor and supplementary motor | Superior Frontal |

| 4. Anterior Mid-body | Motor | Superior Frontal |

| 5. Posterior Mid-body | Somasthetic and posterior parietal | Para-Central |

| 6. Isthmus | Superior temporal and posterior parietal | Para-Central |

| 7. Splenium | Occipital and inferior temporal | Pre-Cuneus |

Figure 1.

Illustration of the relationship between the isthmus corpus callosum tract (light blue) and the corresponding set of para-central cortical regions of interest (dark blue). Mean FA and MD were computed from all voxels in the corpus callosum tract (light blue). Mean BOLD time series were computed from all voxels in the cortical regions of interest (dark blue). The corpus callosum at the midline is included (red) for spatial reference.

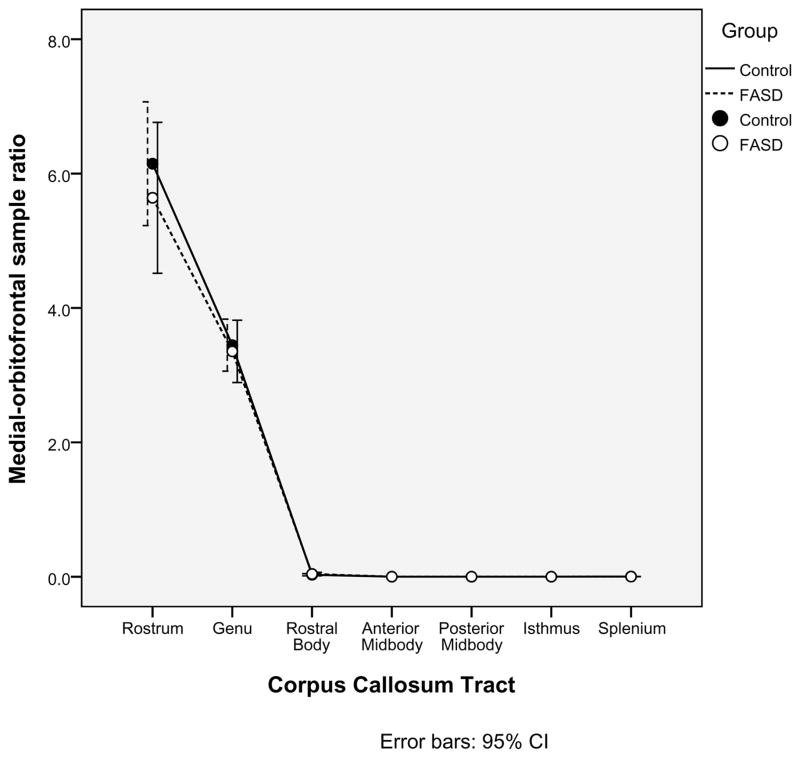

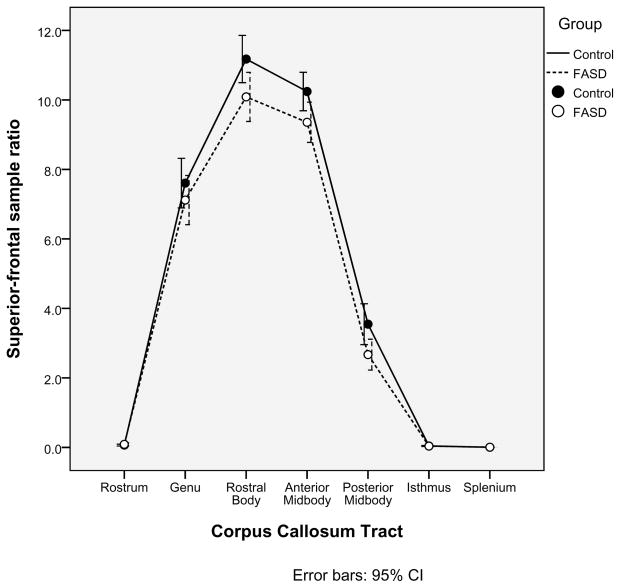

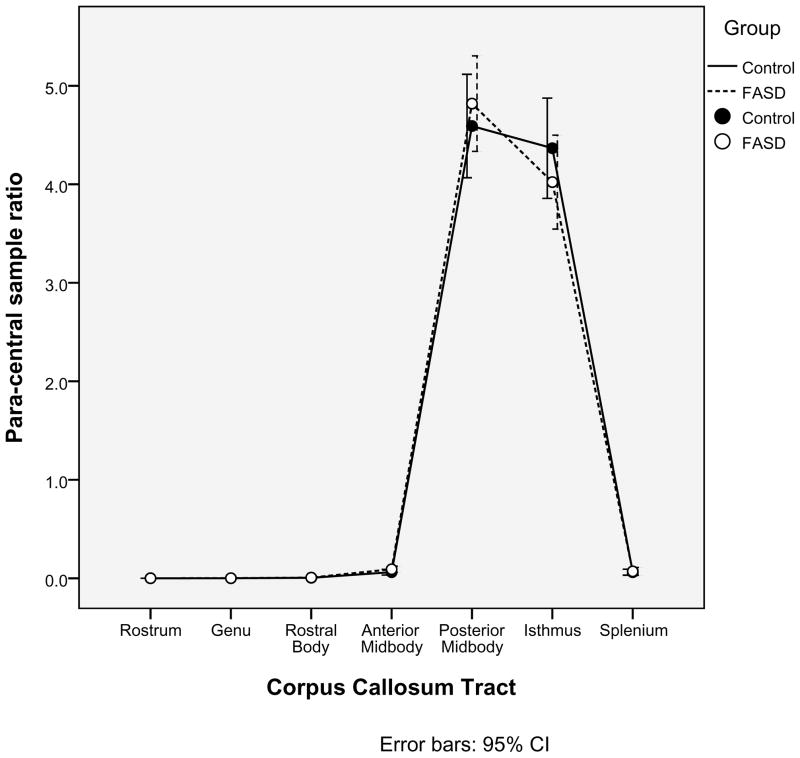

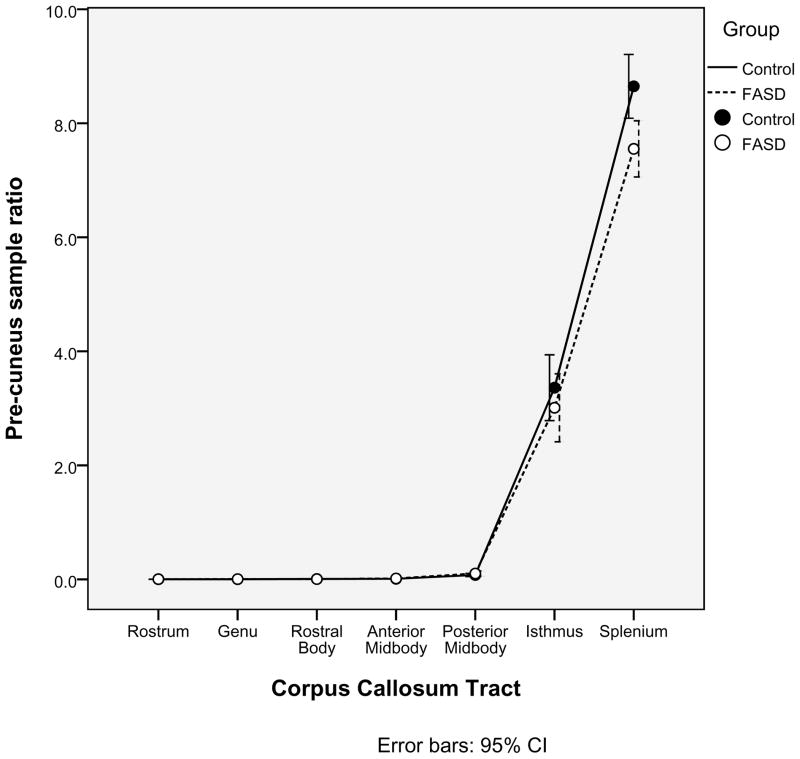

A second, independent analysis of the probabilistic tractography data was employed in order to confirm the relationships between the corpus callosum tracts and cortical ROIs defined in Table 3. Within each of the seven corpus callosum seed regions identified earlier, 5000 samples were sent from each seed voxel into each hemisphere. Within each of the four cortical ROIs (Medial-orbitofrontal, Superior-frontal, Para-central, and Pre-cuneus), the number of samples received from each corpus callosum tract was determined. For each pairing of corpus callosum region and cortical ROI, a ratio of samples received to samples sent was calculated. As illustrated in Figures 2a, 2b, 2c, 2d, there was no significant group difference in the pairings between callosal tracts and cortical ROIs (ex. for the Medial-orbitofrontal ROI, both the control group and the FASD group showed high percentages of samples from the genu and rostrum and very low percentages from the remaining regions. The links identified via the “overlap” methodology described earlier were corroborated by this method. It is worth noting in Figure 2d that the Superior-frontal ROI does receive significant samples from the genu region in addition to the previously identified anterior midbody and rostral body.

Figure 2.

Alternative analysis of the probabilistic tractography data confirms the relationships between cortical regions of interest and corpus callosum tracts. The mean ratios of samples received to samples sent are illustrated for each of the four cortical regions of interest (2a. Medial-orbitofrontal; 2b. Superior-frontal; 2c. Para-central; and 2d. Pre-cuneus).

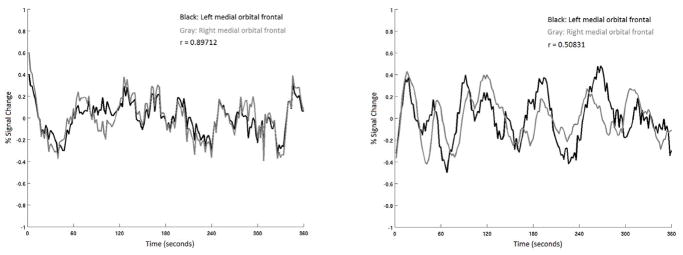

To accomplish goal 2, the four sets of cortical ROIs identified above were probed for connectivity deficits by investigating functional connectivity in the resting-state fMRI data. These four cortical regions were aligned to the fMRI data using FLIRT with a linear six degree of freedom registration. Mean pixel intensity was computed within each of the ROIs, yielding one value for each ROI at every time point. Separately, mean pixel intensity across the brain was also computed at every time point. A representative white matter time series was also extracted by applying an eroded mask comprising the Freesurfer right and left white matter ROIs to the fMRI data. Similarly, a representative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) time series was extracted by applying a mask comprising the Freesurfer right and left lateral ventricle ROIs to the fMRI data. Custom MATLAB code was used to regress the four ROI time series against the six motion correction parameters, the whole brain voxel intensity time series, the white matter time series, and the CSF time series. Pearson product-moment time series correlations were computed for each of the four sets of right and left ROIs for each subject. Figure 3 illustrates time series from medial orbitofrontal ROIs with an example of high correlation in a control subject and low correlation in a subject with FASD.

Figure 3.

Sample six-minute resting fMRI time-series from two participants recorded from left (black) and right (gray) medial orbital-frontal regions of interest. The figure on the left, from a control subject, shows tight inter-hemispheric correlation. In contrast, the figure on the right, from a subject with FASD, shows much lower inter-hemispheric correlation.

RESULTS

Group comparison of motion during MRI scans

In addition to correcting the data for motion as detailed above, a group comparison was performed to test for any potential remaining systematic group difference in motion. The resting fMRI data were used for this comparison because of their relative sensitivity to motion. Translational motion (in mm.) and rotational motion (in radians) were used for these analyses (Liao et al., 2010; Liu et al., 2008). Independent samples t-tests showed that there were not significant group differences in the amount of translation [T=.434, p = .667] or rotation [T=.−.012, p = .991]. Therefore, motion was not entered as a covariate in any of the remaining statistical analyses.

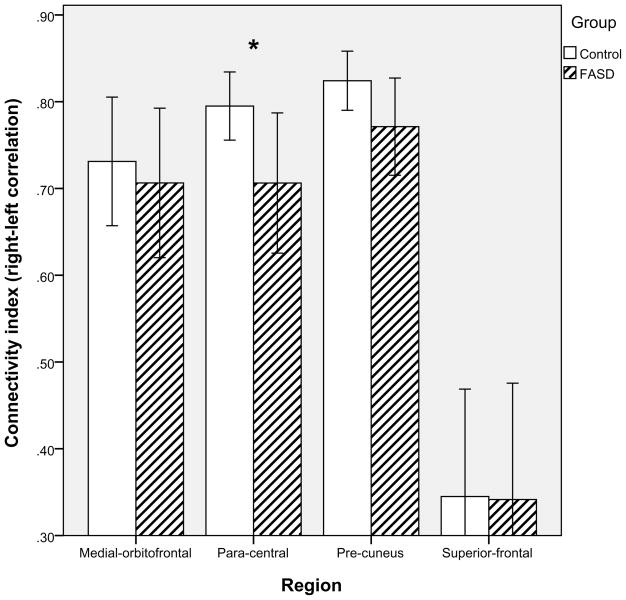

Group differences in functional connectivity

Although the groups were matched on age and sex, the effects of these two subject factors on the dependent measures were tested nonetheless with general linear modeling. Neither was a significant factor and, thus, both were removed from further analyses. A MANOVA testing for differences between controls and FASD for the four inter-hemispheric functional connectivity measures was significant, Wilks’ Lambda = .783, F(4, 38) = 2.63, p = .049 (the volume of the Freesurfer CSF ROI was included as a covariate in this analysis because we observed significant variability across subjects). As shown in Figure 4, connectivity was numerically lower for FASD vs. Controls in all four sets of ROIs, and univariate tests revealed a significant difference in the para-central ROIs, F(1,43)=4.47, p =.041. Children with FASD had inter-hemispheric para-central correlations that were 12.7% lower than controls.

Figure 4.

Inter-hemispheric connectivity by group (control vs. FASD) for four cortical regions of interest. A significant difference was observed in the para-central region (** p<.01).

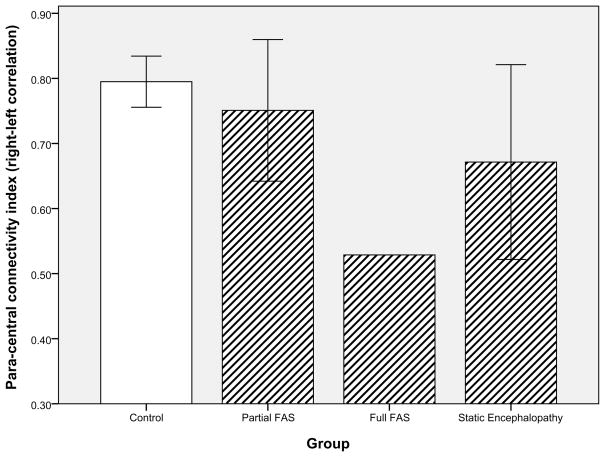

Unfortunately, the diagnostic sub-groups were not large enough to analyze for statistical differences in para-central connectivity, but an examination of the data is informative nonetheless. Figure 5 is noteworthy in that it shows the extremely tight variability of this connectivity measure in healthy control subjects in contrast to the wide variability among children with FASD. The low functional connectivity in the one subject with full FAS was expected and it supports the clinical relevance of the measure to some extent. The notably low level of functional connectivity in those with static encephalopathy is intriguing because this group is generally considered to be less severely affected.

Figure 5.

Inter-hemispheric connectivity in the para-central region by diagnostic group.

Association with facial dysmorphology

Functional connectivity in the para-central ROIs was not found to be associated with facial dysmorphology as defined by 1–4 rankings from the Astley and Clarren diagnostic system. The Spearman correlation was .095, p = .681.

Functional / structural connectivity relationships

We next examined the relationship between inter-hemispheric functional connectivity of the para-central ROIs and microstructural integrity in the corresponding two corpus callosum tracts (isthmus and posterior mid-body) using one-tailed Pearson correlations. As hypothesized, low inter-hemispheric functional connectivity (low right-left correlation) in the para-central ROIs was associated at a trend level with increased MD in the isthmus tract (across all subjects: r = −.23, p = .067) (Controls: r = −.30, p = .086; FASD: r = −.13, p = .383) and significantly in the posterior mid-body tract (all subjects: r = −.29, p = .026) (Controls: r = −.48, p = .01; FASD: r = −.19, p = .20). The correlations with FA were not significant in the isthmus (all subjects: r = .09, p = .287) (Controls: r = −.01, p = .493; FASD: r = .05, p = .419) nor the posterior mid-body (all subjects: r = .111, p = .238) (Controls: r = .292, p = .09; FASD: r = −.01, p = .485). To illustrate the relative specificity of the association between para-central functional connectivity and MD in posterior corpus callosum tracts, Table 4 lists all of the correlation coefficients between para-central ROI functional connectivity and MD in the callosal tracts in positional order from anterior to posterior. The data show a general pattern of stronger association with posterior callosal MD compared with anterior callosal MD, peaking in the posterior-midbody, isthmus, and splenium regions. Breaking this analysis down by groups reveals that this pattern is especially evident in the controls, but that the relationship is less evident in the FASD group alone.

Table 4.

Correlations between para-central functional connectivity Index and mean diffusivity (MD) in seven corpus callosum tracts.

| Corpus Callosum Tract | Correlation between para-central connectivity index and callosal tract MD across all subjects (Pearson r, sig) | Correlations for the control group only | Correlations for the FASD group only |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rostrum | r = .15, p = .162 | r = .28, p = .099 | r = .21, p = .184 |

| 2. Genu | r = −.08, p = .305 | r = −.40, p = .028* | r = −.04, p = .432 |

| 3. Rostral Body | r = −.20, p = .093 | r = −.18, p = .208 | r = −.26, p = .129 |

| 4. Anterior Mid-body | r = −.10, p = .270 | r = −.10, p = .331 | r = −.11, p = .321 |

| 5. Posterior Mid-body | r = −.29, p = .026* | r = −.48, p = .010** | r = −.19, p = .201 |

| 6. Isthmus | r = −.23, p = .067 | r = −.30, p = .086 | r = −.13, p = .383 |

| 7. Splenium | r = −.22, p = .079 | r = −.49, p = .009*** | r = −.15, p = .472 |

Inter-hemispheric connectivity and cognitive functioning

A series of four linear regression analyses were conducted to examine the relative contributions of structural and functional connectivity measures in explaining variance in cognitive functioning. The index scores from the Wechsler intelligence test (WISC-IV or WAIS-III) served as the dependent measures for these analyses. Predictor variables for each regression were the para-central connectivity measure and mean diffusivity from the two associated corpus callosum tracts (isthmus and posterior mid-body). For the Verbal Comprehension Index (VCI), the regression was non-significant, R2 = .098, F(3, 43) = 1.44, p = .245. For the Perceptual Reasoning Index (PRI), the regression was at a trend level, R2 = .146, F(3,43) = 2.28, p = .095. Beta coefficients were as follows: para-central connectivity = .083, t = .553, p = .583, isthmus mean diffusivity = −.440, t = −2.13, p = .039, and posterior mid-body mean diffusivity = .505, t = 2.47, p = .018. Two follow-up regressions by group (control and FASD) were not significant, likely due to the small sample size. For the Working Memory Index (WMI), the regression was non-significant, R2 = −.010, F(3,43) = .865, p = .467. Lastly, for the Processing Speed Index (PSI), the regression was non-significant, R2 = −.065, F(3,43) = .126, p = .944. In this set of analyses, perceptual reasoning was the cognitive factor most related to inter-hemispheric connectivity and it appears that the structural connectivity measures were stronger predictors than the functional connectivity measure in this case.

DISCUSSION

For the first time, we report disturbances in inter-hemispheric functional connectivity during a resting state in children with FASD using fMRI. A number of DTI studies have recently highlighted white matter microstructural abnormalities in FASD and several studies have shown associations with cognitive dysfunction (Fryer et al., 2008; Fryer et al., 2009; Lebel et al., 2010; Lebel et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2005; Sowell et al., 2008; Wozniak et al., 2006; Wozniak et al., 2009). These findings suggest that understanding abnormalities in the brain’s primary communication backbone (white matter) will be important in understanding the particular cognitive challenges faced by these children. For this first study, we focused on examining inter-hemispheric functional connectivity because our previous DTI work has clearly demonstrated underlying abnormalities in the microstructure of posterior corpus callosum fibers connecting the hemispheres (Wozniak et al., 2006; Wozniak et al., 2009). Those findings were consistent with numerous other studies showing abnormalities in corpus callosum structure, especially in the posterior regions (Bookstein et al., 2007; Fryer et al., 2009; Lebel et al., 2008; Li et al., 2009; Ma et al., 2005; Sowell et al., 2008; Sowell et al., 2001a).

Riley et al (1995) first reported volume reductions in both posterior and anterior corpus callosum regions. Sowell et al. (2001a) reported significant posterior callosal volume reductions as well as posterior callosal displacement in individuals with FASD. Bookstein and colleagues have presented a number of highly detailed characterizations of corpus callosum structural abnormalities in FASD. They have shown that callosal shape is more variable in FASD than in normal development (Bookstein et al., 2002a; Bookstein et al., 2001) and they have demonstrated that excessive callosal thickness is associated with executive functioning deficit and callosal thinning is associated with motor impairment (Bookstein et al., 2002b). More recently, they have highlighted posterior abnormalities in callosal shape, especially in the isthmus and splenium, as particularly common in FASD (Bookstein et al., 2005; Bookstein et al., 2007). Overall, the findings of posterior callosal abnormalities in FASD are consistent with other studies showing abnormalities in the cortical regions connected by posterior callosum including peri-sylvian regions of parietal and temporal cortex (Sowell et al., 2001b; Sowell et al., 2002a). These findings may also be consistent with documented abnormalities in posterior cingulate white matter as shown by Bjorkquist et al. (2010). These authors have suggested that the dependent relationship between posterior cingulate and corpus callosum during development may be partly responsible for the finding of abnormalities in both regions in FASD.

Interestingly, the para-central region is one of eight anatomical sub-regions that Hagmann et al. (2008) identified as members of a “structural core” – regions that show elevated fiber counts / fiber densities and regions that had exceptionally high inter-hemispheric connectivity in their network analyses of diffusion spectrum imaging (DSI) tractography-based structural data. The other regions in the structural core include the posterior cingulate, precuneus, cuneus, the isthmus of the cingulate, superior temporal banks, and inferior and superior parietal cortex. Hagmann et al. (2008) characterize this structural core of medial posterior cortical regions as an integrated system that is critical to the coordination of the two hemispheres. This characterization points out the potentially devastating cognitive effects of the structural and functional connectivity abnormalities in these regions that we have now described in FASD.

In the current study, we did not observe a significant relationship between inter-hemispheric functional connectivity in the para-central region and facial dysmorphology. This analysis is somewhat limited by the inclusion of only one participant with full FAS, but there was a range of facial dysmorphology in the sample. In general, this is consistent with our previous studies which did not show a relationship between microstructural integrity of the callosum and facial dysmorphology (Wozniak et al., 2006; Wozniak et al., 2009) and with the view that brain damage and facial stigmata may be semi-independent outcomes of prenatal alcohol exposure (Bookstein et al., 2002a; Connor et al., 2006). A number of other studies have failed to find relationships between facial characteristics and callosal measures. For example, Bookstein et al. (2007; 2002b) found no evidence of a relationship between callosal shape abnormalities and facial dysmorphology. The lack of a relationship between brain and face abnormalities is not inconsistent with the general consensus in the literature that facial dysmorphology is only present in a subset of individuals affected by prenatal alcohol exposure (Stratton et al., 1996) and is tied to a specific window of exposure to alcohol (Sulik, 2005), whereas brain damage may be an outcome of alcohol exposure across a much wider window of exposure during gestation.

The clinical relevance of corpus callosum abnormalities in FASD has been shown in a number of studies that demonstrate associations with cognitive deficits. The current finding of a trend-level relationship between Wechsler Perceptual Reasoning Index score and connectivity mediated via the posterior callosum is consistent with our previous report of a significant association between posterior callosal mean diffusivity and performance on the Wechsler PRI (r = −.45, p = .008) (Wozniak et al., 2009). Similarly, Sowell et al. (2008) showed that fractional anisotropy in the splenium of the corpus callosum was correlated with visuomotor integration skill in children with FASD. Pfefferbaum and colleagues (2006) have observed similar regionally-specific relationships between visuospatial functioning and posterior callosum integrity in alcoholism and have hypothesized that certain tasks requiring bilateral integration are particularly affected by the relatively subtle callosal abnormalities that are seen with DTI. In FASD, corpus callosum shape abnormalities are also known to be associated with executive functioning (Bookstein et al., 2002b) and verbal memory (Sowell et al., 2001a). The current data suggest that DTI microstructural connectivity measures in the posterior callosum may be better predictors of perceptual reasoning ability than the fMRI functional connectivity measure used here. Future studies with larger samples will be able to examine the relative contributions of structural and functional connectivity measures in more depth.

A few studies have focused on the contribution of corpus callosum integrity to inter-hemispheric transfer in FASD. Roebuck et al. (2002) provided evidence that children with FASD have less than optimal inter-hemispheric transfer as evidenced by their performance on the “crossed” condition of a finger localization task. Furthermore, they demonstrated associations between poor task performance and reduced corpus callosum volumes in both anterior and posterior regions. Dodge et al. (2009) also used a finger localization task to examine inter-hemispheric transfer in FASD. They found that children with FASD made more errors on the task and that errors were associated with volume reductions in the isthmus and splenium regions of the corpus callosum. DTI studies suggest that inter-hemispheric transfer is related to even more subtle measures of microstructural corpus callosum integrity. In a sample of healthy, normally-developing children and young adults, Muetzel et al. (2008) showed that FA in the splenium was associated with alternating hand performance on a finger tapping task. A functional/structural connectivity relationship has also been shown using EEG coherence and corpus callosum DTI measures in healthy adults (Teipel et al., 2009). In that study, right-left EEG coherence in the temporal-parietal region was correlated with fractional anisotropy in posterior white matter including posterior corpus callosum. In general, inter-hemispheric transfer of information other than sensory-motor information is challenging to study. For the current study, we utilized a non-task based approach to examine inter-hemispheric functional connectivity, mediated by corpus callosum, during a resting state. In this manner, our functional connectivity measures served as proxy measures of inter-hemispheric transfer of information. The non-task based approach to functional connectivity may have some advantages over task-based approaches in that it may be applicable to younger participants and/or significantly impaired participants who might have difficulty performing tasks.

Limitations to the interpretation of the current results are acknowledged. First, we observed significant psychiatric co-morbidity in the participants with FASD and intentionally did not exclude for co-morbidity. Eliminating potential participants with co-existing psychiatric diagnoses would have significantly limited enrollment in the study and, more importantly, would have seriously limited the generalizability of the results. FASD is well-known to be associated with significant psychiatric co-morbidity of the type that we observed (O'Connor et al., 2002; Steinhausen et al., 1993; Streissguth et al., 2004; Streissguth and O'Malley, 2000). Because Fetal Alcohol spectrum Disorders themselves and the associated psychiatric co-morbidity are both likely related to the underlying neurodevelopmental effects of alcohol, it will likely be extremely difficult to entirely separate the two completely. However, future studies might begin to parse out the effects of these co-morbid disorders by including comparison groups for the major co-morbidities including Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder and Oppositional Defiant Disorder. A second potential limitation of the study relates to the diagnostic system used (Astley and Clarren’s 4-Digit code), for which there is not universal agreement. Alternate diagnostic criteria exist, including those proposed by the Institute of Medicine (1996) and modified by Hoyme et al. (2005) as well as those proposed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention for FAS (Bertrand et al., 2004). Critics of the 4-Digit coding system have argued that it is overly complex, it over-emphasizes brain dysfunction (which is a non-specific component of the syndrome), it is subject to problems with diagnostic consensus, and may over-diagnose FASD (Benz et al., 2009; Hoyme et al., 2005; Jones et al., 2006). The current study attempted to address some of these concerns by only enrolling participants with confirmed heavy alcohol exposure and/or measurable facial dysmorphology in addition to cognitive dysfunction. A more narrow focus on full FAS could have been taken, but would have limited the generalizability of the results.

Thus far, this is the first study to examine inter-hemispheric functional connectivity in FASD. The data suggest that communication between homologous cortical regions is disturbed in FASD, and is specifically disturbed in those regions connected by posterior corpus callosum fibers, especially the isthmus and splenium. Because this disturbance in functional connectivity may be related to macrostructural or microstructural abnormalities and to cognitive functioning, further efforts to examine functional connectivity in FASD are warranted. The current analyses suggested that the relationship between regional microstructural connectivity and functional connectivity is stronger in non-exposed controls versus children with FASD. At this point, it is unclear why this would be the case. One possibility is that greater variability in white matter anatomy at the macroscopic level among those with FASD may be adding variability to these analyses of microstructural integrity. Small sample size may also have been a factor. Thus, future studies with larger numbers of subjects may benefit from additional analyses of potential differences in anatomy such as differences in white matter fiber projections as determined by DTI tractography.

Overall the connectivity methods used here can easily be extended to other white matter tracts in the brain, allowing for examination of additional networks. A number of analysis approaches have been described (Fox and Raichle, 2007) and are potentially applicable to FASD including placing multiple seeds in known anatomical networks (Kelly et al., 2009; Margulies et al., 2007) or applying independent components analysis in a purely empirical derivation of functional networks (Beckmann et al., 2005; Biswal et al., 2003; Greicius et al., 2004).

In addition to providing data that complement the findings of white matter structural abnormalities in FASD, these types of functional connectivity measures may serve an additional role in providing quantitative metrics of brain health. In turn, these metrics may be useful in exploring subgroups of individuals with FASD, further examining relationships with cognitive functioning, and possibly evaluating the effects of new interventions for neurodevelopmental conditions including FASD. Recent interventions targeting early neurodevelopment in those exposed to alcohol, such as peri-natal nutritional supplementation, will ultimately be evaluated by sensitive measures of brain status such as microstructural integrity and functional connectivity. Although abnormalities in these characteristics are not likely to be specific to FASD and there will be challenges to interpreting the data in light of findings in common co-morbid conditions such as ADHD (Konrad and Eickhoff, 2010), it is possible that these measures may prove to be uniquely sensitive to the effects of prenatal alcohol exposure and, thus, useful in further understanding the full range of effects across the full FASD spectrum.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Dana Foundation, The National Institutes of Health (5P41RR008079, 5K12RR023247, P30-NS057091,& MO1-RR00400), and the MIND Institute.

References

- Abel EL. An update on incidence of FAS: FAS is not an equal opportunity birth defect. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995;17:437–443. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(95)00005-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aboitiz F, Scheibel AB, Fisher RS, Zaidel E. Fiber composition of the human corpus callosum. Brain Res. 1992;598:143–153. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(92)90178-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archibald SL, Fennema-Notestine C, Gamst A, Riley EP, Mattson SN, Jernigan TL. Brain dysmorphology in individuals with severe prenatal alcohol exposure. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2001;43:148–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astley SJ, Clarren SK. Diagnosing the full spectrum of fetal alcohol-exposed individuals: introducing the 4-digit diagnostic code. Alcohol Alcohol. 2000;35:400–410. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/35.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Autti-Ramo I, Autti T, Korkman M, Kettunen S, Salonen O, Valanne L. MRI findings in children with school problems who had been exposed prenatally to alcohol. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2002;44:98–106. doi: 10.1017/s0012162201001748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann CF, DeLuca M, Devlin JT, Smith SM. Investigations into resting-state connectivity using independent component analysis. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1001–1013. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Nunes RG, Clare S, Matthews PM, Brady JM, Smith SM. Characterization and propagation of uncertainty in diffusion-weighted MR imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2003;50:1077–1088. doi: 10.1002/mrm.10609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benz J, Rasmussen C, Andrew G. Diagnosing fetal alcohol spectrum disorder: History, challenges and future directions. Paediatr Child Health. 2009;14:231–237. doi: 10.1093/pch/14.4.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertrand J, Floyd RL, Weber MK, O'Connor MJ, Riley EP, Johnson KA, Cohen DE. FAS/FAE NTFo. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Guidelines for referral and diagnosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta, GA: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Biswal B, Yetkin FZ, Haughton VM, Hyde JS. Functional connectivity in the motor cortex of resting human brain using echo-planar MRI. Magn Reson Med. 1995;34:537–541. doi: 10.1002/mrm.1910340409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biswal BB, Pathak AP, Ulmer JL, Hudetz AG. Decoupling of the hemodynamic and activation-induced delays in functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2003;27:219–225. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200303000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjorkquist OA, Fryer SL, Reiss AL, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Cingulate gyrus morphology in children and adolescents with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Psychiatry Res. 2010;181:101–107. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Connor PD, Covell KD, Barr HM, Gleason CA, Sze RW, McBroom JA, Streissguth AP. Preliminary evidence that prenatal alcohol damage may be visible in averaged ultrasound images of the neonatal human corpus callosum. Alcohol. 2005;36:151–160. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2005.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Connor PD, Huggins JE, Barr HM, Pimentel KD, Streissguth AP. Many infants prenatally exposed to high levels of alcohol show one particular anomaly of the corpus callosum. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2007;31:868–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2007.00367.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Sampson PD, Connor PD, Streissguth AP. Midline corpus callosum is a neuroanatomical focus of fetal alcohol damage. Anat Rec. 2002a;269:162–174. doi: 10.1002/ar.10110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Connor PD. Geometric morphometrics of corpus callosum and subcortical structures in the fetal-alcohol-affected brain. Teratology. 2001;64:4–32. doi: 10.1002/tera.1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bookstein FL, Streissguth AP, Sampson PD, Connor PD, Barr HM. Corpus callosum shape and neuropsychological deficits in adult males with heavy fetal alcohol exposure. Neuroimage. 2002b;15:233–251. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2001.0977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broyd SJ, Demanuele C, Debener S, Helps SK, James CJ, Sonuga-Barke EJ. Default-mode brain dysfunction in mental disorders: A systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2008;33:279–296. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarren SK. Neuropathology in fetal alcohol syndrome. In: West JR, editor. Alcohol and Brain Development. Oxford University Press; New York: 1986. pp. 158–166. [Google Scholar]

- Clarren SK, Alvord EC, Jr, Sumi SM, Streissguth AP, Smith DW. Brain malformations related to prenatal exposure to ethanol. J Pediatr. 1978;92:64–67. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(78)80072-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarren SK, Smith DW. The fetal alcohol syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1978;298:1063–1067. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197805112981906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coles CD, Brown RT, Smith IE, Platzman KA, Erickson S, Falek A. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure at school age. I. Physical and cognitive development. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1991;13:357–367. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(91)90084-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connor PD, Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM. Effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on fine motor coordination and balance: A study of two adult samples. Neuropsychologia. 2006;44:744–751. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2005.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dale AM, Fischl B, Sereno MI. Cortical surface-based analysis. I. Segmentation and surface reconstruction. Neuroimage. 1999;9:179–194. doi: 10.1006/nimg.1998.0395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge NC, Jacobson JL, Molteno CD, Meintjes EM, Bangalore S, Diwadkar V, Hoyme EH, Robinson LK, Khaole N, Avison MJ, Jacobson SW. Prenatal alcohol exposure and interhemispheric transfer of tactile information: Detroit and Cape Town findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1628–1637. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.00994.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fair DA, Cohen AL, Dosenbach NU, Church JA, Miezin FM, Barch DM, Raichle ME, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. The maturing architecture of the brain's default network. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4028–4032. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0800376105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox MD, Raichle ME. Spontaneous fluctuations in brain activity observed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:700–711. doi: 10.1038/nrn2201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friston KJ, Frith CD, Liddle PF, Frackowiak RS. Functional connectivity: the principal- component analysis of large (PET) data sets. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1993;13:5–14. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.1993.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer SL, Frank LR, Spadoni AD, Theilmann RJ, Nagel BJ, Schweinsburg AD, Tapert SF. Microstructural integrity of the corpus callosum linked with neuropsychological performance in adolescents. Brain Cogn. 2008;67:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fryer SL, Schweinsburg BC, Bjorkquist OA, Frank LR, Mattson SN, Spadoni AD, Riley EP. Characterization of White Matter Microstructure in Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00864.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius M. Resting-state functional connectivity in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Neurol. 2008;21:424–430. doi: 10.1097/WCO.0b013e328306f2c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greicius MD, Srivastava G, Reiss AL, Menon V. Default-mode network activity distinguishes Alzheimer's disease from healthy aging: evidence from functional MRI. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:4637–4642. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308627101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagmann P, Cammoun L, Gigandet X, Meuli R, Honey CJ, Wedeen VJ, Sporns O. Mapping the structural core of human cerebral cortex. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e159. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han X, Jovicich J, Salat D, van der Kouwe A, Quinn B, Czanner S, Busa E, Pacheco J, Albert M, Killiany R, Maguire P, Rosas D, Makris N, Dale A, Dickerson B, Fischl B. Reliability of MRI-derived measurements of human cerebral cortical thickness: the effects of field strength, scanner upgrade and manufacturer. Neuroimage. 2006;32:180–194. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyme HE, May PA, Kalberg WO, Kodituwakku P, Gossage JP, Trujillo PM, Buckley DG, Miller JH, Aragon AS, Khaole N, Viljoen DL, Jones KL, Robinson LK. A practical clinical approach to diagnosis of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: clarification of the 1996 institute of medicine criteria. Pediatrics. 2005;115:39–47. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton KR, Howe JC, Battaglia FC, editors. Institute of Medicine (IOM) Fetal alcohol syndrome: Diagnosis, epidemiology, prevention, and treatment. Washington D.C: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Janzen LA, Nanson JL, Block GW. Neuropsychological evaluation of preschoolers with fetal alcohol syndrome. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 1995;17:273–279. doi: 10.1016/0892-0362(94)00063-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady M, Smith S. Improved optimization for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(02)91132-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. doi: 10.1016/s1361-8415(01)00036-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston JM, Vaishnavi SN, Smyth MD, Zhang D, He BJ, Zempel JM, Shimony JS, Snyder AZ, Raichle ME. Loss of resting interhemispheric functional connectivity after complete section of the corpus callosum. J Neurosci. 2008;28:6453–6458. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0573-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones KL, Robinson LK, Bakhireva LN, Marintcheva G, Storojev V, Strahova A, Sergeevskaya S, Budantseva S, Mattson SN, Riley EP, Chambers CD. Accuracy of the diagnosis of physical features of fetal alcohol syndrome by pediatricians after specialized training. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1734–1738. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly AM, Di Martino A, Uddin LQ, Shehzad Z, Gee DG, Reiss PT, Margulies DS, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Development of anterior cingulate functional connectivity from late childhood to early adulthood. Cereb Cortex. 2009;19:640–657. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kodituwakku PW, Coriale G, Fiorentino D, Aragon AS, Kalberg WO, Buckley D, Gossage JP, Ceccanti M, May PA. Neurobehavioral characteristics of children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in communities from Italy: Preliminary results. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1551–1561. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00187.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konrad K, Eickhoff SB. Is the ADHD brain wired differently? A review on structural and functional connectivity in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:904–916. doi: 10.1002/hbm.21058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korkman M, Kettunen S, Autti-Ramo I. Neurocognitive impairment in early adolescence following prenatal alcohol exposure of varying duration. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn C Child Neuropsychol. 2003;9:117–128. doi: 10.1076/chin.9.2.117.14503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaDue RA, Streissguth AP, Randels SP. Clinical considerations pertaining to adolescents and adults with fetal alcohol syndrome. In: Sonderegger TB, editor. Perinatal Sunstance Abuse: Research Findings and Clinical Implications. Johns Hopkins University Press; Baltimore: 1992. pp. 104–131. [Google Scholar]

- Larroque B, Kaminski M. Prenatal alcohol exposure and development at preschool age: main results of a French study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Rasmussen C, Wyper K, Andrew G, Beaulieu C. Brain microstructure is related to math ability in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34:354–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01097.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lebel C, Rasmussen C, Wyper K, Walker L, Andrew G, Yager J, Beaulieu C. Brain diffusion abnormalities in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorder. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;23:1732–1740. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00750.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Coles CD, Lynch ME, Hu X. Voxelwise and skeleton-based region of interest analysis of fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders in young adults. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:3265–3274. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao W, Zhang Z, Pan Z, Mantini D, Ding J, Duan X, Luo C, Lu G, Chen H. Altered functional connectivity and small-world in mesial temporal lobe epilepsy. PLoS One. 2010;5:e8525. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Liang M, Zhou Y, He Y, Hao Y, Song M, Yu C, Liu H, Liu Z, Jiang T. Disrupted small-world networks in schizophrenia. Brain. 2008;131:945–961. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupton C, Burd L, Harwood R. Cost of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2004;127C:42–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma X, Coles CD, Lynch ME, Laconte SM, Zurkiya O, Wang D, Hu X. Evaluation of corpus callosum anisotropy in young adults with fetal alcohol syndrome according to diffusion tensor imaging. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:1214–1222. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000171934.22755.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies DS, Kelly AM, Uddin LQ, Biswal BB, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. Mapping the functional connectivity of anterior cingulate cortex. Neuroimage. 2007;37:579–588. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Goodman AM, Caine C, Delis DC, Riley EP. Executive functioning in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:1808–1815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Riley EP. A review of the neurobehavioral deficits in children with fetal alcohol syndrome or prenatal exposure to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:279–294. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1998.tb03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Riley EP, Delis DC, Stern C, Jones KL. Verbal learning and memory in children with fetal alcohol syndrome. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20:810–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson SN, Riley EP, Gramling L, Delis DC, Jones KL. Heavy prenatal alcohol exposure with or without physical features of fetal alcohol syndrome leads to IQ deficits. J Pediatr. 1997;131:718–721. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)70099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- May PA, Gossage JP. Estimating the prevalence of fetal alcohol syndrome. A summary. Alcohol Res Health. 2001;25:159–167. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muetzel RL, Collins PF, Mueller BA, AMS, Lim KO, Luciana M. The development of corpus callosum microstructure and associations with bimanual task performance in healthy adolescents. Neuroimage. 2008;39:1918–1925. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.10.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Connor MJ, Shah B, Whaley S, Cronin P, Gunderson B, Graham J. Psychiatric illness in a clinical sample of children with prenatal alcohol exposure. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2002;28:743–754. doi: 10.1081/ada-120015880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson HC, Streissguth AP, Sampson PD, Barr HM, Bookstein FL, Thiede K. Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with behavioral and learning problems in early adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1187–1194. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199709000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfefferbaum A, Adalsteinsson E, Sullivan EV. Dysmorphology and microstructural degradation of the corpus callosum: Interaction of age and alcoholism. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:994–1009. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quigley M, Cordes D, Turski P, Moritz C, Haughton V, Seth R, Meyerand ME. Role of the corpus callosum in functional connectivity. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2003;24:208–212. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, MacLeod AM, Snyder AZ, Powers WJ, Gusnard DA, Shulman GL. A default mode of brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:676–682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raichle ME, Snyder AZ. A default mode of brain function: a brief history of an evolving idea. Neuroimage. 2007;37:1083–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.02.041. discussion 1097–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riley EP, Mattson SN, Sowell ER, Jernigan TL, Sobel DF, Jones KL. Abnormalities of the corpus callosum in children prenatally exposed to alcohol. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:1198–1202. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb01600.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roebuck TM, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Interhemispheric transfer in children with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26:1863–1871. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000042219.73648.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson PD, Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Little RE, Clarren SK, Dehaene P, Hanson JW, Graham JM., Jr Incidence of fetal alcohol syndrome and prevalence of alcohol-related neurodevelopmental disorder. Teratology. 1997;56:317–326. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199711)56:5<317::AID-TERA5>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skudlarski P, Jagannathan K, Calhoun VD, Hampson M, Skudlarska BA, Pearlson G. Measuring brain connectivity: diffusion tensor imaging validates resting state temporal correlations. Neuroimage. 2008;43:554–561. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.07.063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. doi: 10.1002/hbm.10062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Woolrich MW, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Johansen-Berg H, Bannister PR, De Luca M, Drobnjak I, Flitney DE, Niazy RK, Saunders J, Vickers J, Zhang Y, De Stefano N, Brady JM, Matthews PM. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23:S208–219. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2004.07.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Johnson A, Kan E, Lu LH, Van Horn JD, Toga AW, O'Connor MJ, Bookheimer SY. Mapping white matter integrity and neurobehavioral correlates in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. J Neurosci. 2008;28:1313–1319. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5067-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Mattson SN, Thompson PM, Jernigan TL, Riley EP, Toga AW. Mapping callosal morphology and cognitive correlates: Effects of heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Neurology. 2001a;57:235–244. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.2.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Mattson SN, Tessner KD, Jernigan TL, Riley EP, Toga AW. Voxel-based morphometric analyses of the brain in children and adolescents prenatally exposed to alcohol. Neuroreport. 2001b;12:515–523. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200103050-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Mattson SN, Tessner KD, Jernigan TL, Riley EP, Toga AW. Regional brain shape abnormalities persist into adolescence after heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Cereb Cortex. 2002a;12:856–865. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowell ER, Thompson PM, Peterson BS, Mattson SN, Welcome SE, Henkenius AL, Riley EP, Jernigan TL, Toga AW. Mapping cortical gray matter asymmetry patterns in adolescents with heavy prenatal alcohol exposure. Neuroimage. 2002b;17:1807–1819. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC, Willms J, Spohr HL. Long-term psychopathological and cognitive outcome of children with fetal alcohol syndrome. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:990–994. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199309000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stratton KR, Howe CJ, Battaglia FC. Fetal Alcohol Syndrome: Diagnosis, Epidemiology, Prevention, and Treatment. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Aase JM, Clarren SK, Randels SP, LaDue RA, Smith DF. Fetal alcohol syndrome in adolescents and adults. JAMA. 1991;265:1961–1967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Sampson PD, O'Malley K, Young JK. Risk factors for adverse life outcomes in fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effects. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2004;25:228–238. doi: 10.1097/00004703-200408000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, O'Malley K. Neuropsychiatric implications and long-term consequences of fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Semin Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2000;5:177–190. doi: 10.1053/scnp.2000.6729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streissguth AP, Sampson PD, Olson HC, Bookstein FL, Barr HM, Scott M, Feldman J, Mirsky AF. Maternal drinking during pregnancy: attention and short-term memory in 14-year-old offspring--a longitudinal prospective study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:202–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1994.tb00904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulik KK. Genesis of alcohol-induced craniofacial dysmorphism. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2005;230:366–375. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayze VW, 2nd, Johnson VP, Hanson JW, Piven J, Sato Y, Giedd JN, Mosnik D, Andreasen NC. Magnetic resonance imaging of brain anomalies in fetal alcohol syndrome. Pediatrics. 1997;99:232–240. doi: 10.1542/peds.99.2.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teipel SJ, Pogarell O, Meindl T, Dietrich O, Sydykova D, Hunklinger U, Georgii B, Mulert C, Reiser MF, Moller HJ, Hampel H. Regional networks underlying interhemispheric connectivity: an EEG and DTI study in healthy ageing and amnestic mild cognitive impairment. Hum Brain Mapp. 2009;30:2098–2119. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testa M, Quigley BM, Eiden RD. The effects of prenatal alcohol exposure on infant mental development: a meta-analytical review. Alcohol Alcohol. 2003;38:295–304. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agg087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Kelly SJ, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Comparison of social abilities of children with fetal alcohol syndrome to those of children with similar IQ scores and normal controls. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children. 4. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Whaley SE, O'Connor MJ, Gunderson B. Comparison of the adaptive functioning of children prenatally exposed to alcohol to a nonexposed clinical sample. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:1018–1024. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witelson SF. Hand and sex differences in the isthmus and genu of the human corpus callosum. A postmortem morphological study. Brain. 1989;112:799–835. doi: 10.1093/brain/112.3.799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolrich MW, Jbabdi S, Patenaude B, Chappell M, Makni S, Behrens T, Beckmann C, Jenkinson M, Smith SM. Bayesian analysis of neuroimaging data in FSL. Neuroimage. 2009;45:S173–186. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.10.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak JR, Mueller BA, Chang PN, Muetzel RL, Caros L, Lim KO. Diffusion tensor imaging in children with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:1799–1806. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00213.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozniak JR, Muetzel RL, Mueller BA, McGee CL, Freerks MA, Ward EE, Nelson ML, Chang PN, Lim KO. Microstructural corpus callosum anomalies in children with prenatal alcohol exposure: an extension of previous diffusion tensor imaging findings. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:1825–1835. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01021.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]