Abstract

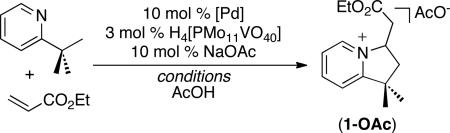

This communication describes a new method for the Pd/polyoxometalate-catalyzed aerobic olefination of unactivated sp3 C–H bonds. Nitrogen heterocycles serve as directing groups, and air is used as the terminal oxidant. The products undergo reversible intramolecular Michael addition, which protects the mono-alkenylated product from over-functionalization. Hydrogenation of the Michael adducts provides access to bicyclic nitrogen-containing scaffolds that are prevalent in alkaloid natural products. Additionally, the cationic Michael adducts undergo facile elimination to release α,β-unsaturated olefins, which can be elaborated in numerous C–C and C–heteroatom bond-forming reactions.

Transition metal catalyzed C–H olefination reactions have been the subject of tremendous research activity over the past 20 years.1 These transformations provide atom economical methods for replacing simple carbon-hydrogen bonds with readily derivatizable alkene functional groups. A variety of different metals (for example, Pd, Cu, Ni, Co, Rh, and Ru) catalyze the olefination of arenes,2 and these transformations have been applied to the synthesis and functionalization of biologically active target molecules.3 Pd-based catalysts have been particularly well studied and effectively promote the reaction of alkenes with diverse arene and heteroarene substrates.4

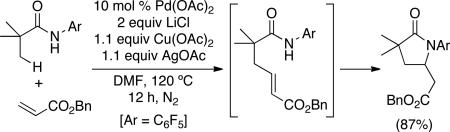

While the olefination of sp2 C–H bonds is a reliable and widely-used synthetic method, analogous transformations at unactivated sp3 C–H sites remain extremely rare.5,6 Expanding this chemistry to unactivated alkyl groups is challenging for several reasons. First, metal-mediated cleavage of sp3 C–H bonds is typically slow7 and is expected to be even slower in the presence of an alkene, which can compete for coordination sites at the metal center. Second, the key C–C bond-forming event requires carbometallation of a Pd-alkyl intermediate. Such reactions (particularly intermolecular variants) are difficult, because they are frequently plagued by competing β-hydride elimination.8,9 Finally, the nucleophilic directing groups required to promote sp3 C–H activation can undergo intramolecular Michael addition to the olefinated products, thereby removing the versatile olefin functional group that was installed in the first step. Due to these challenges, there is currently only one report of the C–H olefination of unactivated sp3 C–H bonds.5 As shown in eq. 1, this study by Yu and coworkers described the Pd-catalyzed reaction of pentafluorophenyl-substituted amides with benzylacrylate (eq. 1).5 Although this was a landmark report, the transformation has a limited substrate scope, requires stoichiometric CuII and AgI salts as oxidants, and yields cyclic products derived from irreversible Michael addition of the amide to the alkene.

|

(1) |

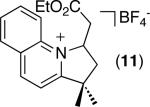

As part of a program aimed at developing Pd-catalyzed methods for the functionalization of unactivated C–H bonds,10 we report herein a new nitrogen heterocycle-directed sp3 C–H olefination reaction. This transformation utilizes air as the terminal oxidant and proceeds efficiently with a series of different 2-alkyl pyridines and α,β-unsaturated alkenes. The olefin-containing products can be elaborated using a variety of synthetic methods. In addition, this reaction provides a conceptually novel entry to 6,5-nitrogen heterocycles, which constitute the cores of numerous alkaloid natural products.

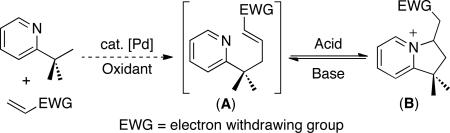

Our first efforts towards sp3 C–H olefination focused on the reaction of 2-tert-butylpyridine (2-tbp) with electron deficient alkenes (eq. 2). Extensive previous work from our group10a,b and others11 has shown that pyridine and quinoline derivatives are effective directing groups for the Pd-mediated cleavage of sp3 C–H bonds. The palladacyclic intermediates are generally slow to undergo β-hydride elimination (presumably due to the strong coordinating ability of pyridine), making them amenable to subsequent functionalization. In addition, we reasoned that a pyridine directing group could undergo reversible intramolecular Michael addition to the olefin product, thereby providing access to either olefin (A) or a cyclic pyridinium salt (B), depending on the reaction conditions (eq. 2).

|

(2) |

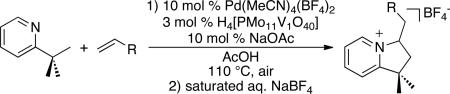

Dioxygen is the most cost effective and environmentally benign terminal oxidant for this transformation. As such, we first examined the reaction of 2-tbp with ethyl acrylate under conditions reported by Ishii for the Pd/polyoxometalate co-catalyzed aerobic olefination of benzene derivatives.12 Gratifyingly, the use of 10 mol % of Pd(OAc)2 and 10 mol % of acetylacetone (acac) along with 3 mol % of H4[PMo11VO40] in AcOH at 90 °C under 1 atm of O2 provided 49% yield of product 1 (Table 1, entry 1). Increasing the temperature to 110 °C under 1 atm of O2 significantly improved the yield to 81% (entry 2).

Table 1.

Optimization of Pd-Catalyzed Reaction between 2-tert-Butylpyridine and Ethylacrylate.

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | [Pd] | Conditions | Yield 1 (%)[a] |

| 1 | Pd(OAc)2 | 90 °C, O2, acac | 49 |

| 2 | Pd(OAc)2 | 110 °C, O2, acac | 81 |

| 3 | Pd(OAc)2 | 110 °C, air, acac | 83 |

| 4 | Pd(OAc)2 | 110 °C, air | 89 |

| 5 | Pd(MeCN)4(BF4)2 | 110 °C, air | 92 |

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis.

We were pleased to find that ambient air could be used in place of 1 atm of O2 without any detrimental effect on the overall yield (Table 1, entry 3). Finally, removing the acac ligand (entry 4) and replacing Pd(OAc)2 with the cationic catalyst Pd(MeCN)4(BF4)213 (entry 5) both accelerated olefination and limited the formation of olefin-derived byproducts.14 Interestingly, despite the presence of an excess (5 equiv) of alkene, this reaction exclusively afforded the monofunctionalized product 1. This is in marked contrast to the C–H acetoxylation of 2-tbp with PhI(OAc)2, which forms mixtures of mono-, di-, and triacetoxylated products.10b In the current system, the intramolecular Michael addition appears to play a key role in protecting the product from over-functionalization.

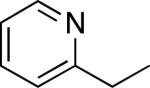

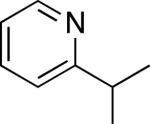

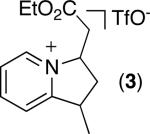

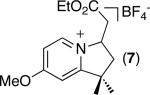

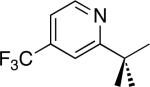

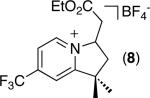

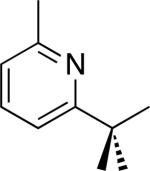

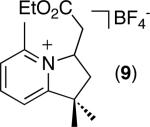

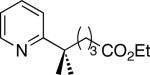

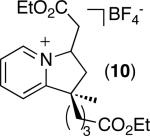

As shown in Table 2, a variety of other 2-alkylpyridine derivatives participate in this sp3 C–H olefination/cyclization reaction. We found that replacing NaOAc with 1.1 equiv of NaOTf allowed for the olefination of substrates lacking geminal dimethyl groups; for example, both 2-ethyl and 2-iso-propylpyridine afforded high yields of the desired products (entries 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Pd-Catalyzed Olefination and Cyclization Between Various Pyridines and Ethyl Acrylate.

| Entry | Substrate | Product | Yield |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 [a] |

|

|

89% |

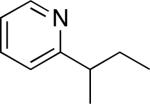

| 2 [a] |

|

|

81% (dr = 1.2 : 1) |

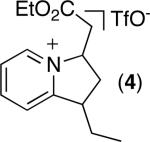

| 3 [a] |

|

|

55% (dr = 1.2 : 1) |

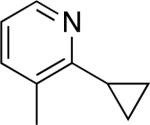

| 4 [a] |

|

|

43% (dr = 2.4 : 1) |

| 5 [b] |

|

|

70% |

| 6 [b] |

|

|

71% |

| 7 [b] |

|

|

75% |

| 8 [b] |

|

|

36% |

| 9 [b] |

|

|

49% (dr = 1 : 1) |

| 10 [b] |

|

|

39% |

Conditions: 1.1 equiv of NaOTf, 10 mol % of Pd(MeCN)4(BF4)2, 3 mol % of H4[PMo11VO40], 5 equiv of ethyl acrylate, AcOH, air, 110 °C, 18 h.

Conditions: (i) 10 mol % of NaOAc, 10 mol % of Pd(MeCN)4(BF4)2, 3 mol % of H4[PMo11VO40], 5 equiv of ethyl acrylate , AcOH, air, 110 °C, 18 h; (ii) saturated aq. NaBF4.

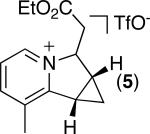

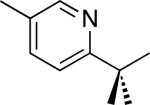

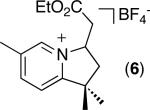

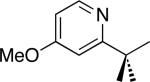

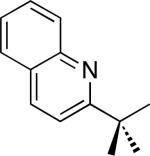

C–H activation/C–C coupling proceeded with >20:1 selectivity for 1° over 2° sp3 C–H bonds (for example, see entry 3). However, a 2° C–H bond on the cyclopropane ring of 2-cyclopropyl-3-methylpyridine could be functionalized to form tricyclic product 5 in modest yield (entry 4). Both electron withdrawing and electron donating substituents were tolerated on the pyridine ring (entries 5-7), and a tethered ester functional group was also compatible with the reaction conditions (entry 9). Remarkably, even 2-methyl-6-tert-butylpyridine provided moderate (36%) yield, despite the sterically crowded environment around the pyridine moiety (entry 8). Finally, quinoline was a useful directing group for sp3 C–H olefination under these conditions (entry 10).

The reaction of 2-tbp was also examined with a series of other olefinic substrates. As shown in Table 3, α,β-unsaturated esters, amides, and ketones were effective alkene coupling partners. Remarkably, the free carboxylic acid moiety of acrylic acid was also well tolerated (entry 4). In contrast, more electron rich olefins like styrene and 1-hexene exhibited low reactivity under the current conditions (entries 7 and 8). This is a common limitation of Pd-catalyzed arene C–H alkenylation reactions.4

Table 3.

Alkene Scope for C–H Bond Alkenylation.

| ||

|---|---|---|

| Entry | R | Yield (%) |

| 1 | CO2Et | 90[a] |

| 2 | CO2Bu | 80[a] |

| 3 | CO2Bn | 75[a] |

| 4 | CO2H | 69[b] |

| 5 | CONMe2 | 55[b] |

| 6 | COEt | 40[a] |

| 7 | Ph | <5[b] |

| 8 | Butyl | nr[c] |

Isolated yield.

Yield determined by 1H NMR spectroscopic analysis.

nr = no reaction detected

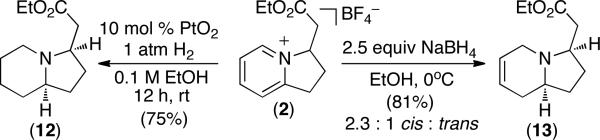

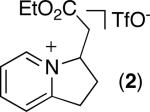

The cationic bicyclic products in Tables 1-3 are useful synthetic intermediates. For example, the PtO2-catalyzed reduction of 2 with H2 formed piperidine 12 in 75% yield as a 28 : 1 mixture of cis and trans isomers (Scheme 1).15 In addition, partial reduction of 2 with NaBH4 in EtOH afforded 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine 13 in 81% yield as a 2.3 : 1 mixture of readily separable cis and trans isomers (Scheme 1).16 This chemistry provides an expedient route to 6,5-nitrogen heterocycles, which are a common structural motif in naturally occurring alkaloids.

Scheme 1.

Reduction Reactions of 2

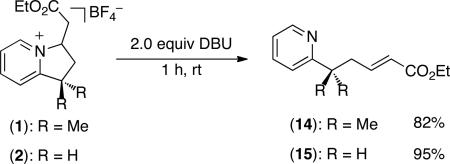

The pyridinium products of sp3 C–H olefination/cyclization can also be converted to the corresponding alkenes by treatment with base. For example, the reaction of 2 with 2 equiv of DBU in CH2Cl2 for 1 h afforded olefin 15 in 95% yield (eq 3).

|

(3) |

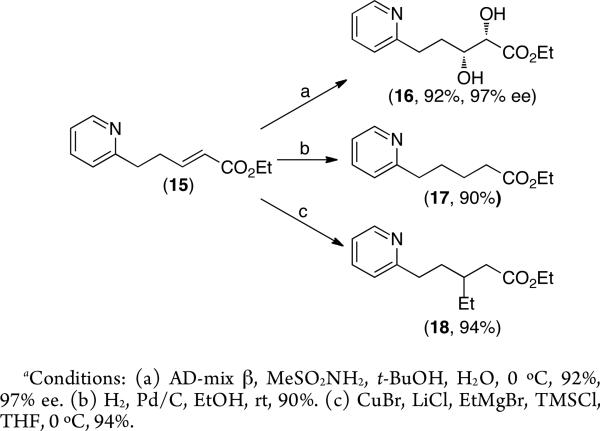

The ability to readily generate the olefin-containing products allowed us to explore the further functionalization of these molecules. In particular, we sought to demonstrate that the pyridine moiety was compatible with various transition-metal mediated olefin functionalization reactions. As shown in Scheme 2, 15 underwent smooth and high yielding asymmetric dihydroxylation17 (to form 16 in 97% ee), Pd/C-catalyzed hydrogenation18 (to form 17), and Cu-catalyzed conjugate addition of EtMgBr19 (to form 18).

Scheme 2.

Functionalization of C–H Olefinated Product 15.a

In conclusion, this communication describes a new Pd-catalyzed reaction for the pyridine-directed aerobic olefination of unactivated sp3 C–H sites. This transformation provides a convenient route to 6,5-N-fused bicyclic cores as well as readily functionalizable alkene products. Ongoing work is focused on expanding the scope of this transformation with respect to both directing group and alkene substrate, and these results will be reported in due course.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank the NIH (GM073836 and GM073836-05S1) for support of this research. KJS thanks the ACS Division of Organic Chemistry/Eli Lilly for a graduate fellowship. In addition, we thank Asako Kubota for the preparation of substrate S5.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Experimental and isolation procedures, and characterization data for all new compounds. This material is free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Oestreich M, editor. The Mizoroki-Heck Reaction. John Wiley and Sons; Chicester, U.K.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a Satoh T, Miura M. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:11212. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b pp. 383–400. Ref 1.

- 3.a Trost BM, Godleski SA, Genet JP. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1978;100:3930. [Google Scholar]; b Baran PS, Corey EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:7904. doi: 10.1021/ja026663t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Garg NK, Caspi DD, Stoltz BM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9552. doi: 10.1021/ja046695b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Beck EM, Hatley R, Gaunt MJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:3004. doi: 10.1002/anie.200705005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Wang DH, Engle KM, Shi BF, Yu J-Q. Science. 2010;327:315. doi: 10.1126/science.1182512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.pp. 345–378. Ref. 1.

- 5.Wasa M, Engle KM, Yu JQ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3680. doi: 10.1021/ja1010866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.For examples of olefination and alkylation at sp3 C–H sites activated by α-heteroatoms or aromatic rings, see: Chatani N, Asaumi T, Yorimitsu S, Ikeda T, Kakiuchi F, Murai S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:10935. doi: 10.1021/ja011540e. and references therein. DeBoef B, Pastine SJ, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:6556. doi: 10.1021/ja049111e.Song C-X, Cai G-X, Farrell TR, Jiang Z-P, Li H, Gan L-B, Shi Z-J. Chem. Commun. 2009:6002. doi: 10.1039/b911031c.

- 7.Jazzar R, Hitce J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shultz LH, Tempel DJ, Brookhart M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11539. doi: 10.1021/ja011055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.a Firmansjah L, Fu GC. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:11340. doi: 10.1021/ja075245r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Bloome KS, Alexanian EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:12823. doi: 10.1021/ja1053913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.a Dick AR, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2300. doi: 10.1021/ja031543m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Desai LV, Hull KL, Sanford MS. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:9542. doi: 10.1021/ja046831c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Dick AR, Sanford MS. Tetrahedron. 2006;62:2439. [Google Scholar]; d Neufeldt SR, Sanford MS. Org. Lett. 2010;12:532. doi: 10.1021/ol902720d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lyons TW, Sanford MS. Chem. Rev. 2010;110:1147. doi: 10.1021/cr900184e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.For examples, see: Zaitsev VG, Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:13154. doi: 10.1021/ja054549f.Shabashov D, Daugulis O. Org. Lett. 2005;7:3657. doi: 10.1021/ol051255q.Reddy BVS, Reddy LR, Corey EJ. Org. Lett. 2006;8:3391. doi: 10.1021/ol061389j.Shabashov D, Daugulis O. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:3965. doi: 10.1021/ja910900p.Zhang S, Luo F, Wang W, Jia X, Hu M, Cheng J. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:3317.

- 12.Obora Y, Ishii Y. Molecules. 2010;15:1487. doi: 10.3390/molecules15031487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nishikata T, Lipshutz BH. Org. Lett. 2010;12:1972. doi: 10.1021/ol100331h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Product 1 was also formed when H4[PMo11VO40]/air was replaced with other oxidants (e.g., Cu(OAc)2 or benzoquinone); however, significantly lower yields were obtained with these oxidants. See Table S3 for details.

- 15.Azzouz R, Fruit C, Bischoff L, Marsais F. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:1154. doi: 10.1021/jo702141b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sinigaglia I, Nguyen TM, Wypych JC, Delpech B, Marazano C. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:3594. doi: 10.1002/chem.201000142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kolb HC, VanNieuwenhze MS, Sharpless KB. Chem. Rev. 1994;94:2483. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dias LC, de Oliveira LG, Vilcachagua JD, Nigsch F. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:2225. doi: 10.1021/jo047732k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reetz MT, Kindler A. J. Organomet. Chem. 1995;502:C5. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.