Abstract

Background:

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) has a high rating in the assessment of breast lesions. Various methods have been used to diagnose cytology of breast lesions.

Aims:

Present study was undertaken to evaluate the feasibility of application of systematic pattern analysis based on morphology in diagnosing breast aspirates.

Materials and Methods:

This is a retrospective study of FNAC of the breast done over a period of 4 years in a tertiary care centre. A total of 225 cases of breast lesions for which FNAC was done with histological follow-up were included in the study. Breast aspirates were provisionally diagnosed based on systematic pattern analysis. Aspirates were grouped into six categories based on predominant cellular pattern, and correlation between cytological and histological diagnosis was assessed.

Results:

Application of pattern analysis on FNAC of breast lesions in our study had a sensitivity of 94.5%, specificity of 98%, diagnostic accuracy of 97%, positive predictive value of 95.8%, and negative predictive value of 97.4%.

Conclusions:

Systematic pattern analysis based on morphology of FNAC smears was found to be highly reliable and could be easily reproducible in the assessment of breast masses.

Keywords: Breast lumps, fine needle aspiration cytology, histopathology, pattern analysis

Introduction

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is widely accepted as a reliable technique in the initial evaluation of palpable and non-palpable (guided biopsy) breast lumps. The procedure is simple, safe, cost effective, minimally invasive, rapid, and as sensitive as biopsy.[1–3]

The primary goal of FNAC is to separate malignant lesions that require more radical therapy from benign ones that may be conservatively managed. The scope of cytology now extends into identifying the subtypes of malignant lesions, benign lesions, and minimal residual disease for the purpose of planning the therapeutic protocol and eventual follow-up. Thus, it plays a major role as an important preoperative assessment along with clinical and mammography examination, which together are frequently referred to as “Triple test”.[4–6]

Pattern is identification of quality as a whole. It is known that despite the many sites and many types of tumors that are aspirated, there are a limited number of patterns based on morphology observed in aspirated material. However, the frequency, significance, and difference of each pattern vary with the site.[7]

Many authors have used various methods to come to a conclusive method of diagnosis on breast lesions. Here, we propose a partially modified method based on systematic pattern analysis to analyze the breast lesions and divide them into individual categories.

Materials and Methods

Material for this study was obtained retrospectively over a period of four years (2007–2010) from the Division of Cytology in the Department of Pathology. Majority of the aspirations were performed in the department itself by cytopathologists. Prior to aspiration, detailed history with physical examination of both the breasts and the mass were carried out to assess its size, mobility, and evidence of clinical signs of malignancy. Axillary nodes were also palpated for enlargement.

Fine needle aspiration was done with a 21- or 22-gauge needle attached to a 10 cc disposable syringe mounted on a syringe holder for single handgrip. The specimen was taken with minimum passes (to minimize hemorrhage) without needle withdrawal and under constant negative pressure. Samples were smeared onto glass slides and fixed as necessary. Wet-fixed smears were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H and E) and Papanicolaou stain, while air-dried smears were stained with May-Grünwald-Giemsa stain.

All cystic lesions were evacuated following which the wall of the cyst was needled. The cyst fluid was centrifuged and the deposit taken for smears.

Amongst a total of 1150 patients with palpable breast lumps who underwent FNAC during the study period, 225 breast aspirates with follow-up excision biopsy/lumpectomy/mastectomy formed the crux of the study.

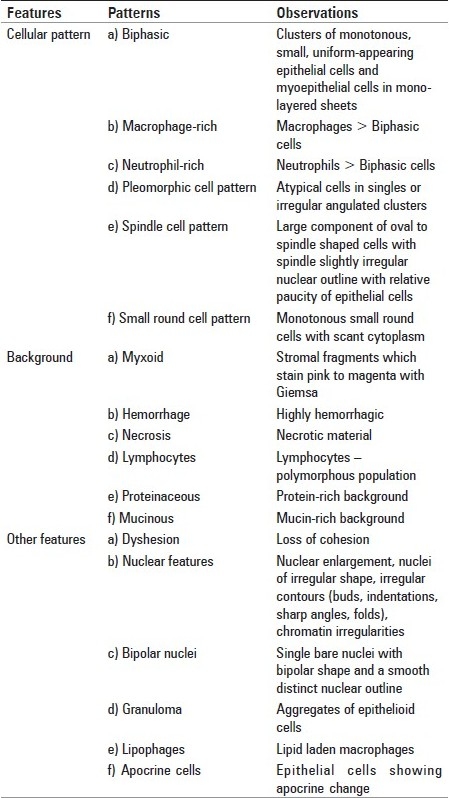

Each slide was reviewed by cytologist who was blind to the original cytological and histopathological diagnosis. The aspirates were evaluated for the cellular features, associated background, and other coexisting features as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

List of various patterns used in this study

The final provisional diagnosis was given out in the following manner:

Benign

Atypical/indeterminate

Suspicious

Malignant.

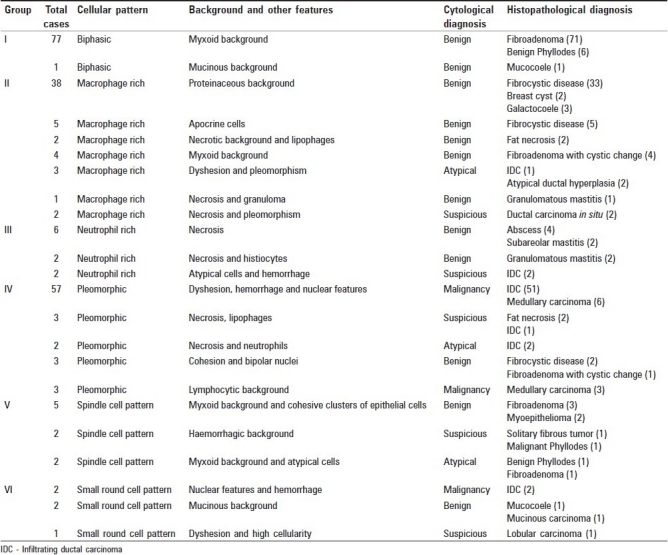

Lesions were categorized into six groups based on the predominant cellular pattern as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

List of cases showing patterns with cyto-histologic correlation

After tabulation of data, the sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values, false negative rate, false positive rate, and diagnostic accuracy were determined for the types of lesion and whether the FNAC results by pattern analysis agreed with the histopathological findings of the excisional biopsy.

Results

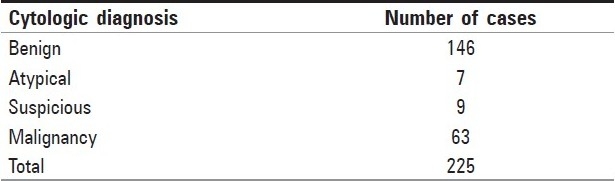

Two hundred and twenty five breast aspirations (age range, 16-88 years; mean age, 38.6 years; side, left breast [74.66%] > right breast [25.34%]) with histological confirmation were observed. Distribution of lesions based on pattern analysis is as shown in [Table 3].

Table 3.

Distribution of lesions based on pattern analysis

On histopathology, out of 225 cases, 152 were benign, 2 in situ lesions, and 71 malignant. Commonest amongst benign lesions were fibroadenoma (FA) followed by fibrocystic disease. Amongst the malignant lesions, infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) was the commonest followed by medullary carcinoma.

In Group I, the primary pattern was biphasic. The most common diagnosis was FA followed by phyllodes tumor (PT).

In Group II, the primary pattern was macrophage-rich pattern with fibrocystic disease as the most common diagnosis. Other lesions in this group were atypical ductal hyperplasia, fat necrosis and carcinoma.

In Group III, the primary pattern was neutrophil-rich pattern. The most common diagnoses were abscess and mastitis.

Group IV comprised of pleomorphic pattern with malignancy as the most common diagnosis. Two cases of fat necrosis were inadvertently called suspicious on cytology.

In Group V, primary pattern was spindle cell pattern with FA as the most common diagnosis. One case of benign PT was called atypical lesion on aspirate.

In Group VI, primary pattern was small round cell pattern with carcinoma as the most common diagnosis. However a case of mucinous carcinoma was called benign on cytology.

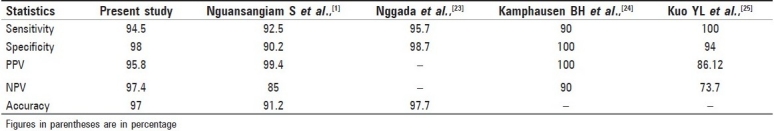

Application of pattern analysis on FNAC of breast lesions in relation to malignancy had a sensitivity of 94.5%, specificity of 98%, diagnostic accuracy of 97%, positive predictive value of 95.8%, and negative predictive value of 97.4%. The false positive and false negative rates were 1.3% and 1.8%, respectively [Table 4].

Table 4.

Comparison of results of the present study with other studies

Discussion

Pattern recognition is defined as “the act of taking in raw data and taking an action based on category of pattern”. Its aim is to classify patterns based on prior knowledge or statistical information extracted from patterns. Here, the perspective is on identification of pattern that is based on various morphological attributes on aspirates of breast lesions (cellular features, background material, and other features).

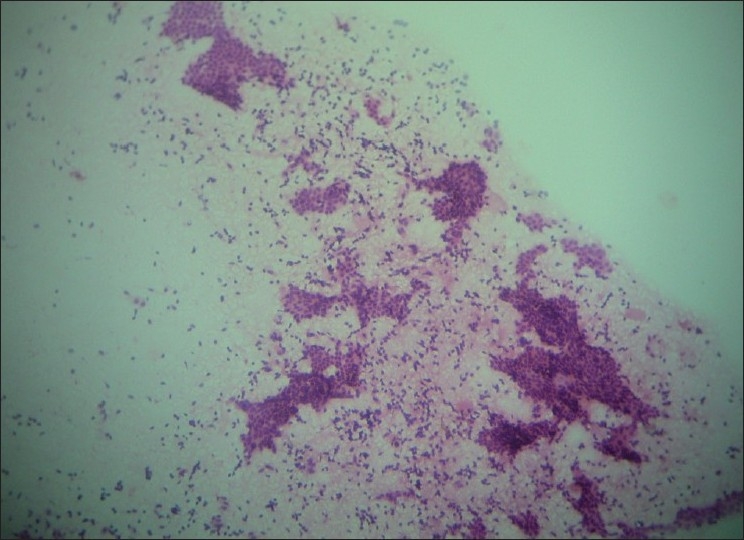

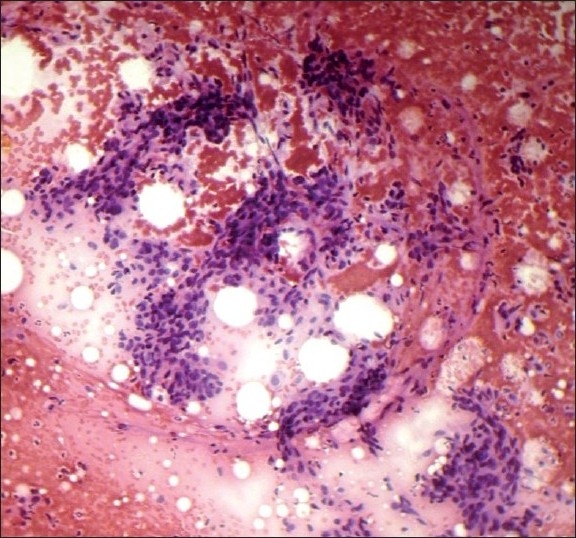

Biphasic pattern (Group I, Figure 1) usually include epithelial cells and myoepithelial cells arranged in mono-layered sheets with a honeycomb pattern (“antler-like, staghorn”). The presence of myoepithelial cells has been recognized as a prominent feature of benign breast disease. Lesions with biphasic pattern are most often benign, hence identification of this pattern is an important aspect of breast lesions.[8–10]

Figure 1.

Biphasic pattern (H and E, ×100)

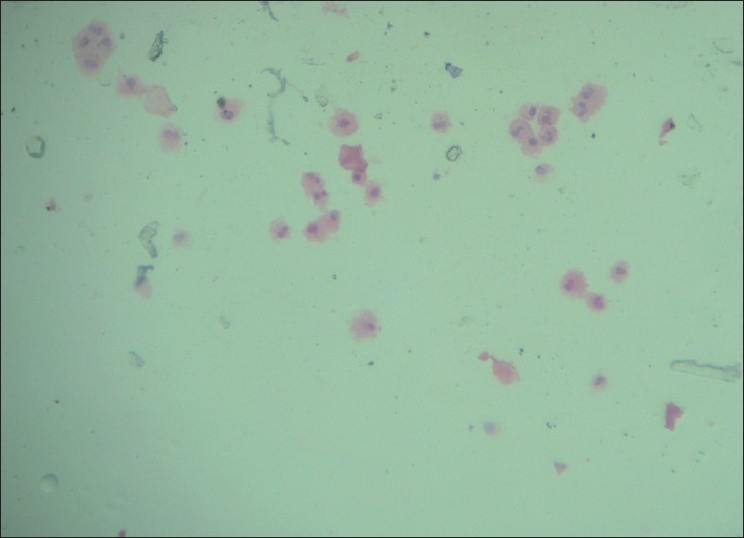

Macrophage-rich pattern (Group II, Figure 2) is seen predominantly in fibrocystic change and in cysts which usually showed foam cells, apocrine cells, and occasionally non-apocrine cells. Smears with apocrine cells showing degenerative atypia should be interpreted with caution, taking into consideration background patterns like proteinaceous background (for benign cystic lesion of breast)and hemorrhagic background (to rule out malignancy).[9,11]

Figure 2.

Macrophage-rich pattern (H and E, ×100)

Two cases of atypical ductal hyperplasia presenting predominantly with macrophage-rich pattern were called atypical on cytology. The term ‘Atypical or Indeterminate’ is intended to indicate those lesions in which a benign lesion is favored, though the possibility of carcinoma cannot be completely ruled out because some atypical features are present. Studies have shown that, in general, cases of atypical ductal hyperplasia are most likely to be diagnosed as negative or atypical.[9,11]

We had a case of ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), which was called suspicious with predominant macrophage-rich pattern and pleomorphism as an associated feature. Ductal carcinoma in situ is more likely to be interpreted as suspicious or positive. The term “Suspicious” has a higher likelihood of representing a malignant tumor, and is used for those lesions in which the suspicion of carcinoma is high, but without definitive evidence of malignancy.[9,12]

Cytological features in neutrophil-rich pattern (Group III, Figure 3) usually include abundant neutrophils along with lymphocytes, plasma cells, apocrine cells, and abundant macrophages. Isolated cells and clusters of epithelial cells with varying degrees of reactive atypia are also present. Two cases of granulomatous mastitis presenting predominantly with neutrophils were diagnosed as abscess on FNAC, later confirmed by biopsy. Granulomas are often misdiagnosed as pyogenic abscess when neutrophils are the predominant cells in a necrotic background. Fine-needle aspiration cytology from the breast lesion continues to remain an important diagnostic tool for breast tuberculosis. Failure to demonstrate necrosis on FNAC does not exclude the diagnosis of tuberculosis in view of small quantity of sample harvested and examined.[13–16]

Figure 3.

Neutrophil-rich pattern (H and E, ×100)

Infiltrating ductal carcinoma presenting predominantly with neutrophils was called as suspicious on cytology. Neutrophils are rarely seen in carcinoma; in such a scenario, aspirates have to be carefully screened for atypical epithelial cells with obvious malignant features.[9]

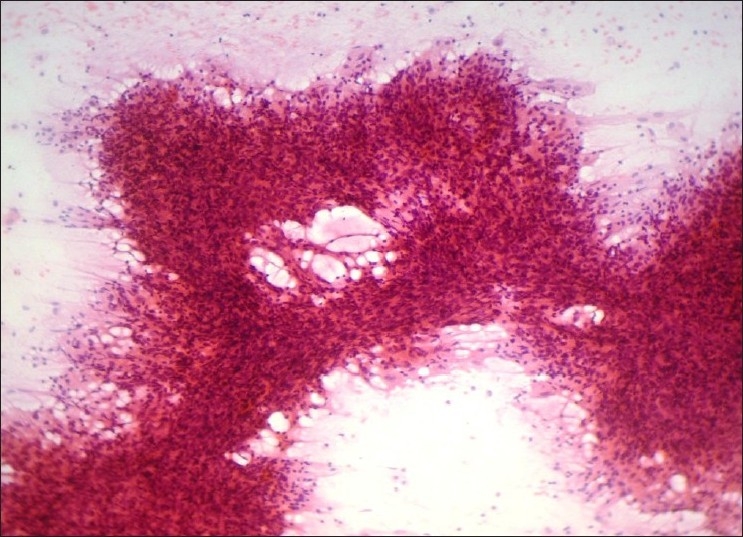

Pleomorphic pattern (Group IV, Figure 4), in a breast aspirate commonly leads to a diagnosis of malignancy. However, benign lesions like FA, fibrocystic disease, and fat necrosis can present with pleomorphism. We had five benign lesions with pleomorphic pattern, of which two were called suspicious on cytology probably due to the presence of some but not all of the cytologic features of malignancy, such as increased cellularity, nuclear enlargement, and conspicuous nucleoli. Two cases of fat necrosis were called suspicious probably due to reactive atypia of ductal epithelial cells which is usually seen in this lesion. Fat necrosis is a mimicker of carcinoma clinically and radiologically that may create diagnostic problems if the history of injury is remote or is not recalled by the patient. The scantiness and cohesion of these cells, which are devoid of significant pleomorphism, should prevent such an error. However, fat necrosis may be associated with carcinoma.[9,10]

Figure 4.

Pleomorphic cell pattern (H and E, ×100)

A case of DCIS was called malignant on cytology. Distinguishing between invasive ductal carcinoma and DCIS is difficult, because the two entities have similar features. Features favoring ductal carcinoma in situ include more single dyshesive atypical cells, loosely arranged epithelial fragments, prominent anisonucleosis, coarser nuclear chromatin (“clumped chromatin”), and background inflammatory cells.[9,17,18]

The smears from medullary carcinoma are typically hypercellular and composed of large tumor cells in a background of reactive lymphocytes and plasma cells. The lymphoid component can be variable.[12]

Spindle-cell rich (Group V, Figure 5) lesions of the breast commonly include PT, fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, and metaplastic carcinoma. These entities can be distinguished by the presence of markedly atypical spindle cells with numerous mitotic figures. Spindle cell pattern should be interpreted with caution due to variable presentation of FA.[9,10,19]

Figure 5.

Spindle cell pattern (H and E, ×100)

A case of PT was diagnosed as an atypical lesion. This could probably be due to atypia of epithelial or stromal/mesenchymal cells which can be pronounced. Phyllodes tumor is mistaken for ductal carcinomas and forms a significant cause of false-positive diagnoses. The presence of stromal fragments and some benign ductal cells could support the diagnosis of PT.[9]

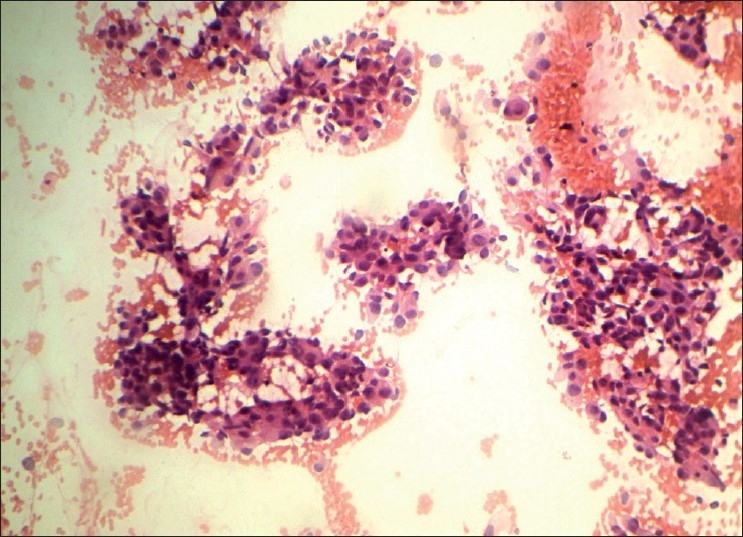

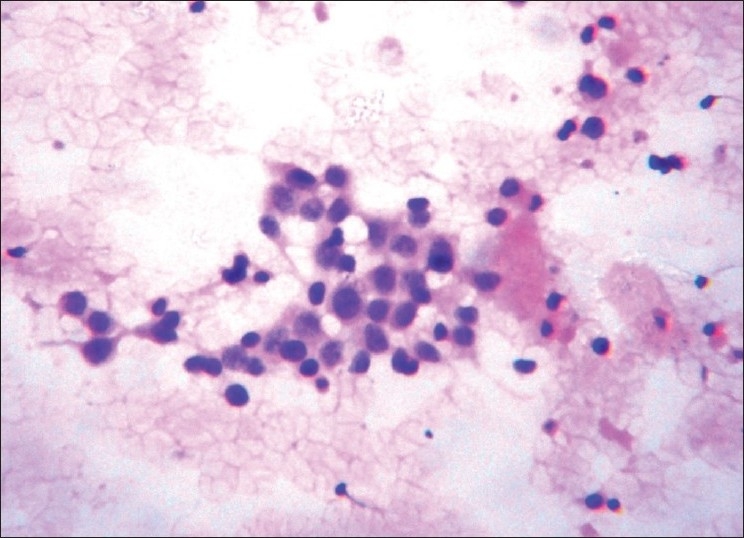

Small round cell pattern (Group VI, Figure 6) includes lesions composed of cells with minimal atypia like lobular carcinoma, mucinous carcinoma, tubular carcinoma, low-grade carcinoma of ductal origin, adenoid cystic carcinoma, lymphoma, metastatic small round cell tumors, and benign lesions like mucocoele, adenosis, and FA.[9]

Figure 6.

Small round cell pattern (H and E, ×400)

One case of mucinous carcinoma was interpreted as benign lesion on cytology. Mucinous carcinoma is a low-grade carcinoma and usually has monomorphic cell pattern and mimics various benign lesions. Absence of myoepithelial cells and distinctive feature like thin-walled capillaries, either free floating or coursing through the thick mucin could help in making a diagnosis.[12,20]

One case of classic form of invasive lobular carcinoma was called suspicious on cytology. Lobular carcinoma cells are relatively small and their malignant nature may be overlooked. However, a higher proportion of dissociated cells, homogenous small malignant cells with minimal cytoplasm, large but non-pleomorphic nuclei are pointers for classic form of invasive lobular carcinoma.[21,22]

The statistical values indicating the diagnostic efficacies of the present study is well comparable to other studies [Table 4].[1,23–25]

Our findings illustrate the value of applying a systematic pattern analysis to evaluate the breast cytology smear. The present study substantiates that assessment of pattern has enough accuracy for the surgeon to triage into operative and non-operative cases.

Identification of the patterns could help in reducing the interobserver variation and make it more reproducible especially in 90% of the cases, which do have common patterns. This method is dependent on adequate material in the smear. Inadequate smears, uncommon presentation/diagnosis, low quality of slide needs experience, and pattern analysis would be difficult to apply in these cases.

This method needs to be standardized by bigger studies with its application helping in reducing the variable diagnosis between cytologists and thus helping the clinician to make an informed decision.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated that FNAC based on systematic pattern analysis is accurate in the diagnosis of breast lesions. It is also easily applicable and could be reproducible. Along with radiology it could provide important information for prompt recognition of discordant results. Hence we recommend this method in the interpretation of breast FNAC.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

References

- 1.Nguansangiam S, Jesdapatarakul S, Tangjitgamol S. Accuracy of fine needle aspiration cytology from breast masses in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2009;10:623–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalhan S, Dubey S, Sharma S, Dudani S, Preeti , Dixit M. Significance of nuclear morphometry in cytological aspirates of breast masses. J Cytol. 2010;27:16–21. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.66694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chaiwun B, Settakorn J, Ya-In C, Wisedmongkol W, Rangdaeng S, Thorner P. Effectiveness of fine-needle aspiration cytology of breast: analysis of 2,375 cases from northern Thailand. Diagn Cytopathol. 2002;26:201–5. doi: 10.1002/dc.10067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhargava V, Jain M, Agarwal K, Thomas S, Singh S. Critical appraisal of cytological nuclear grading in carcinoma of breast and its correlation with ER/PR expression. J Cytol. 2008;25:58–61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Joshi A, Maimoon S. Limitations of fine needle aspiration cytology in subtyping breast malignancies – a report of three cases. J Cytol. 2007;24:203–6. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaufman Z, Shpitz B, Shapiro M, Rona R, Lew S, Dinbar A. Triple approach in the diagnosis of dominant breast masses: combined physical examination, mammography, and fine-needle aspiration. J Surg Oncol. 1994;56:254–7. doi: 10.1002/jso.2930560413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller T. Breast. In: Renshaw AA, editor. Aspiration cytology – A pattern recognition approach. 1st ed. China: Elsevier Saunders; 2005. pp. 431–76. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattari SK, Dey P, Gupta SK, Joshi K. Myoepithelial cells: any role in aspiration cytology smears of breast tumors? Cytojournal. 2008;5:9. doi: 10.1186/1742-6413-5-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Saad RS, Silverman JF. Breast. In: Bibbo M, editor. Comprehensive cytopathology. 3rd ed. China: Elseiver Saunders; 2009. pp. 713–72. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Levine PH, Cangiarella J. Cytomorphology of benign breast disease. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25:689–712. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Masood S. Cytomorphology of fibrocystic change, high-risk proliferative breast disease, and premalignant breast lesions. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25:713–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Howell LP, Lin-Chang L. Cytomorphology of common malignant tumors of the breast. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25:733–60. doi: 10.1016/j.cll.2005.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishore B, Khare P, Gupta RJ, Bisht SP. Fine needle aspiration cytology in the diagnosis of inflammatory lesions of the breast with emphasis on tuberculous mastitis. J Cytol. 2007;24:155–6. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma PK, Babel AL, Yadav SS. Tuberculosis of breast (study of 7 cases) J Postgrad Med. 1991;37:24–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kant S, Dua R, Goel MM. Bilateral tubercular mastitis. Lung India. 2007;24:90–3. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kakkar S, Kapila K, Singh MK, Verma K. Tuberculosis of the breast. A cytomorphologic study. Acta Cytol. 2000;44:292–6. doi: 10.1159/000328467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masood S, Frykberg ER, McLellan GL, Scalapino MC, Mitchum DG, Bullard JB. Prospective evaluation of radiologically directed fine-needle aspiration biopsy of nonpalpable breast lesions. Cancer. 1990;66:1480–7. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901001)66:7<1480::aid-cncr2820660708>3.0.co;2-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sneige N, White VA, Katz RL, Troncoso P, Libshitz HI, Hortobagyi GN. Ductal carcinoma in-situ of the breast: fine needle aspiration cytology of 12 cases. Diagn Cytopathol. 1989;5:371–7. doi: 10.1002/dc.2840050406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bandyopadhyay R, Nag D, Mondal SK, Mukhopadhyay S, Roy S, Sinha SK. Distinction of phyllodes tumor from fibroadenoma: Cytologists′ perspective. J Cytol. 2010;27:59–62. doi: 10.4103/0970-9371.70739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nayak SK, Naik R, Upadhyaya K. Raghuveer CV, Pai MR.FNAC diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma of male breast--a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2001;44:355–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kini H, Pai R, Rau AR, Lobo FD, Augustine AJ, Ramesh BS. Pleomorphic lobular carcinoma of the breast – a diagnostic dilemma. J Cytol. 2007;24:193–5. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Abhijit HD, Ashok GS, Prakash MR, Basavaraj GV, Shrishail MC. Accuracy of intra-operative imprint smears in breast tumors: A study of 40 cases with review of literature. Ind J Surg. 2006;68:302–5. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nggada HA, Tahir MB, Musa AB, Gali BM, Mayun AA, Pindiga UH, et al. Correlation between histopathologic and fine needle aspiration cytology diagnosis of palpable breast lesions: a five-year review. Afr J Med Med Sci. 2007;36:295–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamphausen BH, Toellner T, Ruschenburg I. The value of ultra-sound-guided fine-needle aspiration cytology of the breast: 354 cases with cytohistological correlation. Anticancer Res. 2003;23:3009–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kuo YL, Chang TW. Can concurrent core biopsy and fine needle aspiration biopsy improve the false negative rate of sonographically detectable breast lesions? BMC Cancer. 2010;10:371. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]