Abstract

Interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase 2 (IRAK2) has been shown to be essential for lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-mediated posttranscriptional control of cytokine and chemokine production. In this study, we investigated the role of IRAK2 kinase activity in LPS-mediated posttranscriptional control by reconstituting IRAK2-deficient macrophages with either wild-type or kinase-inactive IRAK2. Compared with wild-type IRAK2 (IRAK2-WT) macrophages, kinase-inactive IRAK2 (IRAK2-KD) macrophages show reduced cytokine and chemokine mRNA stability and translation in response to LPS. Further, LPS-treated IRAK2-KD macrophages also show reduced activation of MKK3/6, MNK1, and eIF4E and attenuated toll-like receptor 4-induced tristetraprolin modification and stabilization. Taken together, these results suggest that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for the optimal activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling, which regulates cytokine and chemokine production at posttranscriptional levels.

Introduction

Innate immunity detects invading pathogens through the recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns by the toll-like receptors (TLRs), which triggers the adaptive immune response (Medzhitov and others 1997; Rock and others 1998; Takeuchi and others 1999; Chuang and Ulevitch 2000; Hemmi and others 2000; Zhang and others 2004). Upon binding of TLR ligands, all of the TLRs except TLR3 recruit the adaptor molecule MyD88 through the toll-interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain, mediating the so-called MyD88-dependent pathway (Akira and others 2001). MyD88 then recruits serine-threonine kinases interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinase 4 (IRAK4), IRAK1, and IRAK2 (Cao and others 1996; Kawagoe and others 2008). IRAK4 is the kinase that functions upstream of and phosphorylates IRAK1 and IRAK2, which mediates the recruitment of TRAF6 to the receptor complex (Deng and others 2000). The IRAKs-TRAF6 complex then activates the downstream kinases, such as transforming growth factor β-activated kinase 1 (TAK1), which leads to the activation of NFκB and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling cascades (Ninomiya-Tsuji and others 1999). The activation of NFκB and MAPK signaling cascades induces the transcription of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, including tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-6, and chemokine (C-X-C) motif ligand 1 (CXCL-1/KC).

In addition to induction of gene transcription, the production of TLR-induced proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines is also regulated at the posttranscriptional level (Anderson 2008). Many cytokine mRNAs have adenine- and uridine-rich elements (AREs) in their 3′ untranslated regions, characterized by a pentamer “AUUUA” or a nonamer “UUAUUUAUU,” promoting rapid decay of these mRNAs (Caput and others 1986; Shaw and Kamen 1986). Proteins that associate with AREs mediate interactions between these mRNAs and exosome complexes, the major machinery for intracellular mRNA degradation. Tristetraprolin (TTP), the prototype of an ARE-binding protein, plays a critical role in inhibiting cytokine and chemokine production by destabilizing their mRNAs (Datta and others 2008; Hartupee and others 2008). Upon TLR stimulation, TTP is phosphorylated, which reduces its affinity for AREs and abolishes TTP-dependent destabilization of proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine mRNAs (Brook and others 2006; Hitti and others 2006; Ronkina and others 2007). Further, MAPK signaling is also involved in the regulation of cytokine mRNA translation. The MAPK-interacting serine/threonine kinases (MNKs) are activated in response to lipopolysaccharide (LPS), subsequently activating eIF4E through phosphorylation, which is a 5′ cap (CAP)-binding protein in the translation initiation complex. The phosphorylation of eIF4E promotes translation of a variety of LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokines (Fukunaga and Hunter 1997; Ueda and others 2004; Rowlett and others 2008).

Much effort has been devoted toward the search for inhibitors of IRAKs to block TLR signaling, with the hope of developing better anti-inflammatory therapies (Janssens and Beyaert 2003). Analyses of IRAK4 kinase-inactive knockin mice indeed showed that inactivation of IRAK4 kinase activity leads to resistance to LPS-induced septic shock and diminished production of cytokines and chemokines in response to stimulation of IL-1 and TLR ligands (Kim and others 2007). Interestingly, TLR/IL-1R–mediated cytokine and chemokine mRNA stability is reduced in bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) from IRAK4 kinase-inactive knockin mice (Kim and others 2007). Consistent with this finding, we recently reported that the IRAK4 substrate, IRAK2, is also essential for LPS-mediated posttranscriptional control of cytokine and chemokine production (Wan and others 2009). One important question is whether IRAK2 kinase activity is important for LPS-mediated posttranscriptional control, which will provide critical information for the search and development of IRAK2 inhibitors. In this study, wild-type and kinase-inactive IRAK2 were used to restore the IRAK2-deficient macrophages. Analyses of these cells showed that inactivation of IRAK2 kinase activity resulted in a reduction of LPS-mediated cytokine/chemokine mRNA stability and translation, which contributed to reduced cytokine and chemokine production in the IRAK2 kinase-inactive macrophages. These results demonstrate a critical role of IRAK2 kinase activity in the posttranscriptional control of LPS-induced proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine production.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

LPS (Escherichia coli 055:B5) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich; R848 from GLSynthesis; CpG from Invivogen. Antibodies against phospho-MKK3/6, phospho-ERK, phospho-p38, phospho-MNK1, phospho-eIF4E, and phospho-MK2 were purchased from Cell Signaling; anti-IRAK2 from Abcam; anti-β-actin from Sigma-Aldrich; anti-TTP was a gift from Dr. Perry Blackshear at the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Bone marrow-derived macrophages

Bone marrow was obtained from tibiae and femurs of IRAK2 knockout mice and cultured in Dulbecco's minimal essential medium with 20% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and 30% L929 cell-conditioned medium for 5 days for differentiation of BMMs.

Construction of pMX-IRAK2 retroviral constructs and generation of IRAK2 put back cells

IRAK2 cDNA was cloned by reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR) from wild-type BMMs with primers 5′-CATGGCTTGCTACATCTACC-3′ and 5′-ACGTTTGTCTGTCCAGTTGA-3′. The kinase-inactive mutant IRAK2 (KK235AA) was generated by site-direct mutagenesis PCR. The wild-type and kinase-inactive mutant IRAK2 were cloned into pMX retroviral expression vector and transfected into phoenix cells for viral packaging. IRAK2-deficient BMMs were infected with the packaged retroviral constructs separately, selected with puromycin (2 μg/mL) for 3 days for stable viral integration, and used as IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, and EMPTY macrophages.

In vitro kinase assay

IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, and EMPTY macrophages were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 0, 10, and 30 min and then lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, 137 mM NaCl, 5 mM EDTA, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mM PMSF, 20 mg/mL Aprotinin, 20 mg/mL Leupeptin, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na4P2O7, and 10 mM β-glycerophosphate) on ice. IRAK2 was immunoprecipitated with anti-IRAK2 antibody and protein A-Sepharose beads. The beads were washed 4 times with the lysis buffer and once with the kinase assay buffer [25 mM HEPES (pH 7.6), 20 mM MgCl2, 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, and 2 mM DTT] and incubated with 5 μg of myelin basic protein and 10 mCi of [γ32P]-labeled ATP in 20 μL of kinase assay buffer for 15 min at room temperature. Reactions were terminated by boiling and samples were separated by SDS-PAGE. Dried gels were analyzed by autoradiography.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, and EMPTY macrophages were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL), R848 (1 μg/mL), or CpG B (1 μg/mL), and the culture media were collected at 24 h after stimulation. IL-6, KC, and TNF-α concentrations in the culture medium were measured by ELISA kits purchased from R&D Systems.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated with the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen). Quantitative PCR was performed as previously described (Kim and others 2007). The results were normalized to mouse β-actin. The specific primer sequences used for mouse β-actin, mouse TNF-α, mouse IL-6, mouse KC, and mouse GAPDH are as follows: β-actin (133 bp): 5′-GGTCATCACTATTGGCAACG-3′ and 5′-ACGGATGTCAACGTCACACT-3′; TNF-α (103 bp): 5′-CAAAGGGAGAGTGGTCAGGT-3′ and 5′-ATTGCACCTCAGGGAAGAGT-3′; IL-6 (127 bp): 5′-GGACCAAGACCATCCAATTC-3′ and 5′-ACCACAGTGAGGAATGTCCA-3′; KC (125 bp): 5′-TAGGGTGAGGACATGTGTGG-3′ and 5′-AAATGTCCAAGGGAAGCGT-3′. GAPDH (179 bp); 5′-GAGCTGAACGGGAAGCTCAC-3′ and 5′-TGTCATACCAGGAAATGAGC-3′.

Polysome fraction analysis

IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages were stimulated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 1.5 h. Polysomal fraction analysis was performed as previously described (Wan and others 2009).

Expression profiling

Two hundred fifty nanograms of RNA was reverse transcribed into cRNA and biotin-UTP labeled using the Illumina TotalPrep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion). cRNA was quantified using a nanodrop spectrophotometer and the cRNA quality (size distribution) was further analyzed on a 1% agarose gel. cRNA was hybridized to the Illumina MouseRef8-v2 Expression BeadChip using standard protocols (provided by Illumina) and the chips were washed and stained using protocols provided by Illumina. The arrays were scanned using an Illumina BeadArray Reader and the data were loaded into Illumina BeadStudion software for quality control and data analysis purposes.

Statistical analysis

Repeated measures analysis of variance was used to compare LPS-mediated cytokine and chemokine mRNA stabilization in IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages.

Results

Kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for TLR-mediated cytokine and chemokine production

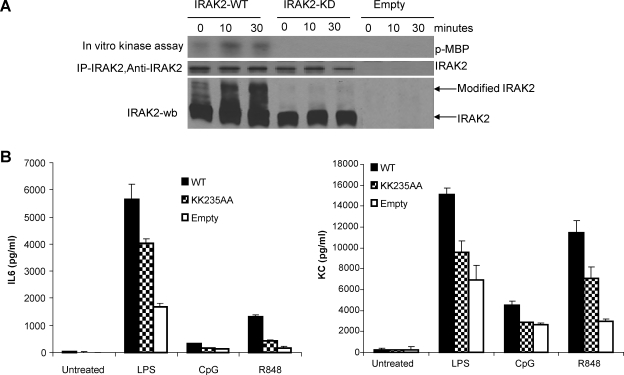

To investigate the role of IRAK2 kinase activity in TLR signaling, we mutated the ATP-binding site in the kinase domain by converting the 2 adjacent conserved lysine residues into alanines (KK235AA, IRAK2-KD) (Kawagoe and others 2008) and retrovirally expressed wild-type (IRAK2-WT) and the mutant IRAK2 (IRAK2-KD) in IRAK2-deficient macrophages derived from IRAK2-deficient mice. IRAK2 was immunoprecipitated from cell lysates of untreated- or LPS-treated IRAK2-deficient macrophages restored with IRAK-WT or IRAK2-KD, followed by in vitro kinase assay using the myelin basic protein as a substrate. The wild-type IRAK2 showed increased kinase activity in response to LPS stimulation, whereas the kinase activity of mutant IRAK2 was completely impaired (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, wild-type IRAK2 was modified in response to LPS stimulation, whereas the mutant IRAK2 failed to be modified, indicating that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is essential for its own modification (Fig. 1A). Further, the inactivation of IRAK2 kinase activity impaired the ability of IRAK2 to restore IRAK2-deficient macrophages to produce TNF-α and KC in response to the stimulation by multiple TLR ligands, demonstrating that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for cytokine and chemokine production in multiple TLR-mediated signaling (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for optimal production of cytokine and chemokine in toll-like receptor ligands-stimulated macrophages. (A) IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD constructs or empty vector and then treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for indicated times; lysates were immunoprecipitated with IRAK2 antibody, and IRAK2 kinase activities were determined by in vitro kinase assay using myelin basic protein (MBP). (B) IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, or empty vector and then cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL), R848 (1 μg/mL), or CpG (1 μg/mL) for 24 h. The production of interleukin (IL)-6 and chemokine (C-X-C) motif ligand 1 (CXCL-1/KC) in supernatant was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

The kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for stabilization of a subset of cytokine and chemokine mRNAs in response to LPS

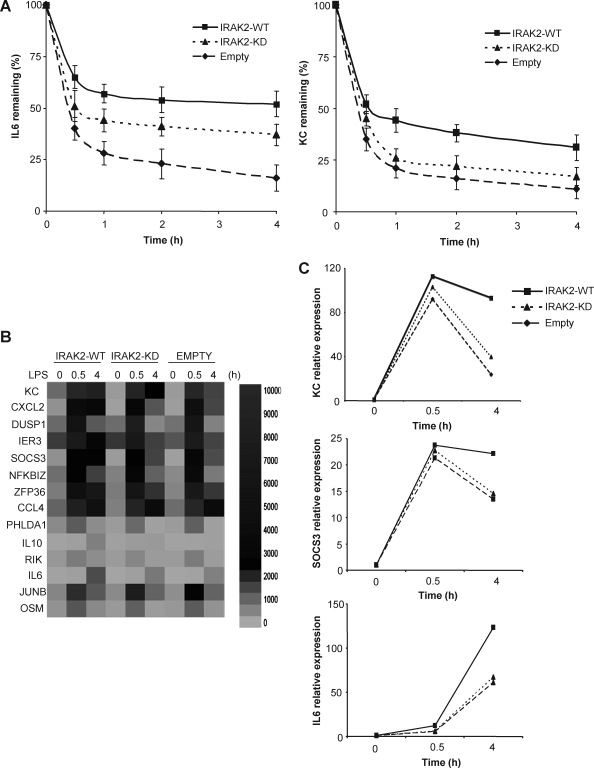

As our previous study shows that IRAK2 is critical for LPS-mediated posttranscriptional control of cytokine and chemokine production, we investigated cytokine and chemokine mRNA decay in IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages in response to LPS. Macrophages were first treated with LPS for 1.5 h, followed by treatment with actinomycin D (to block gene transcription) and LPS (for mRNA stabilization) for 0.5–4 h. Although KC and IL-6 mRNAs were induced to similar levels in IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages, the decay rate of those mRNAs was accelerated and the mRNA levels were lower in IRAK2-KD macrophages when compared with that in IRAK2-WT macrophages (Fig. 2A). These results demonstrate that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for LPS-mediated cytokine and chemokine mRNA stabilization. To determine the overall impact of IRAK2 kinase activity on TLR-mediated gene expression, we examined gene expression profiles of IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages in response to LPS stimulation using Illumina array analysis. Sixty-seven genes were induced (>2-folds) in IRAK2-WT macrophages at early time (0.5 h) in response to LPS stimulation. Majority of these genes (63/67) showed similar levels of expression (<2-folds) between IRAK2-WT macrophages and IRAK2-KD macrophages at early time in response to LPS stimulation. Interestingly, among the 63 genes, 14 genes showed reduced levels of expression (>2-folds) in IRAK2-KD macrophages at late time (4 h) in response to LPS stimulation, indicating that the mRNA stability of these genes might be affected by the kinase activity of IRAK2 (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

Kinase activity of IRAK2 is required to stabilize LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine mRNA. (A) IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, or empty vector, and put back cells were pretreated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 90 min and then treated with actinomycin D (5 μg/mL) and LPS (1 μg/mL) for indicated times. KC and IL-6 mRNAs were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction (PCR), normalized by β-actin, and plotted. Results shown are the mean and standard deviation of 3 independent experiments (P < 0.05). (B) IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT, IRAK2-KD, or empty vector. The put back cells were treated with LPS for indicated times and analyzed by Illumina microarray analysis. A heat map is shown for genes that are induced to similar levels in IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD cells at 0.5 h, but much lower in the IRAK2-KD than the IRAK2-WT cells at 4 h. (C) Confirmation of some genes shown in B with real-time PCR.

The kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for LPS-mediated translation of cytokine and chemokine mRNA

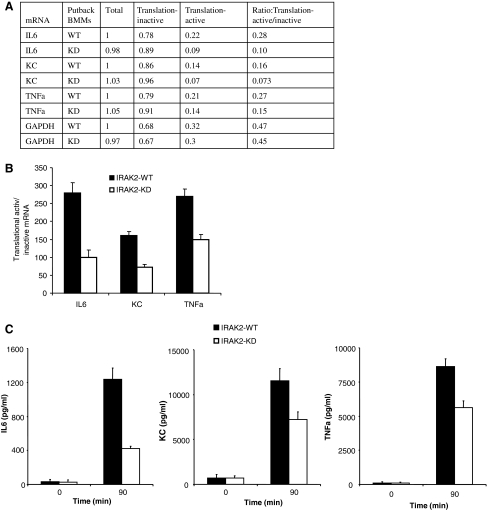

In addition to mRNA stability, IRAK2 has also been shown to mediate LPS-induced translational control of cytokines and chemokines. To investigate the role of IRAK2 kinase activity in the regulation of protein translation, we used polysomal fractionation to separate translation-active mRNA and translation-inactive mRNA from LPS-treated IRAK2-WT and IRAK2-KD macrophages. Compared with IRAK2-WT macrophages, the IRAK2-KD microphages had more cytokine and chemokine mRNAs in the translation-inactive pool than that in the translation-active pool (Fig. 3A). As a result, the ratios of LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine mRNAs in translation-active versus translation-inactive pools were reduced in IRAK2-KD macrophages compared with IRAK2-WT macrophages, suggesting that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for LPS-mediated protein translation (Fig. 3B, C).

FIG. 3.

Kinase activity of IRAK2 is required to promote the translation of LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine mRNAs. (A) IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT or IRAK2-KD vector, and put back cells were treated with LPS (1 μg/mL) for 90 min. Cytokine, chemokine, and GAPDH mRNAs from unfractionated cell lysates, translation-active pools, and translation-inactive pools were analyzed by quantitative reverse transcription–PCR and normalized to β-actin. Similar results were obtained in 3 independent experiments. One representative is shown. (B) The ratios of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, IL-6, and KC mRNAs from translation-active and -inactive pools are shown. Results shown are the mean and standard deviation of 3 independent experiments (P < 0.05). (C) The production of IL-6, KC, and TNF-α were measured in the supernatant of LPS-treated or nontreated cells with enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

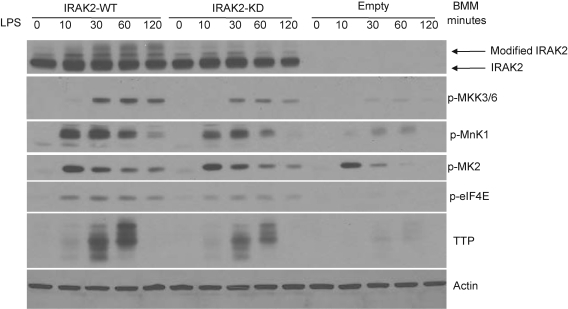

Activation of MAPK signaling is impaired in IRAK2-KD macrophages in response to LPS

These observations promoted us to examine the role of IRAK2 kinase activity in regulating TLR-mediated MAPK signaling, which is involved in the posttranscriptional control. The upstream kinase MKK3/6 and downstream effector molecules MNK1 and eIF4E were phosphorylated at lower levels in LPS-treated IRAK2-KD macrophages compared with that in IRAK2-WT macrophages (Fig. 4). LPS stimulation has been shown to induce TTP modification and stabilization (Anderson 2008). The accumulation of modified TTP was reduced in IRAK2-KD macrophages upon LPS stimulation compared with IRAK2-WT macrophages, indicating the potential role of IRAK2 kinase activity in mediating TLR4-induced TTP modification and stabilization.

FIG. 4.

Kinase activity of IRAK2 is required to fully activate mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling. IRAK2-deficient macrophages were restored by IRAK2-WT or IRAK2-KD vector, and put back cells were treated with LPS for indicated times. Cell lysates were analyzed by the Western method with antibodies against IRAK2, phospho-MKK3/6, phospho-p38, phospho-Erk, phospho-MK2, phospho-MNK1, tristetraprolin (TTP), phospho-eIF4E, and actin.

Discussion

We previously report a novel function for IRAK2 in mediating LPS-triggered posttranscriptional control of cytokine and chemokine expression. Consequently, the IRAK2-deficient mice were resistant to lethal endotoxic shock, because of impaired proinflammatory cytokine and chemokine induction. Here we show that kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for IRAK2 to mediate LPS-induced cytokine and chemokine mRNA stability and translation. Compared with IRAK2-WT macrophages, IRAK2-KD macrophages demonstrate reduced cytokine and chemokine mRNA stability and translation in response to LPS. Further, LPS-treated IRAK2-KD macrophages also show reduced activation of MKK3/6, MNK1, and eIF4E and attenuated TLR4-induced TTP modification and stabilization. Taken together, these results suggest that the kinase activity of IRAK2 is required for the optimal activation of MAPK signaling, which regulates cytokine and chemokine production at posttranscriptional levels.

It is important to note that LPS-mediated TTP induction is diminished following LPS stimulation of IRAK2-KD macrophages. We found that cycloheximide treatment does not block the induced TTP following LPS treatment (data not shown). Therefore, the induced TTP is not from newly synthesized protein. Previous studies have shown that ligand-induced modification of TTP leads to its dissociation from mRNAs and stabilization of TTP, which promotes mRNA stability. It is intriguing that we only detected the modified TTP upon LPS stimulation. We speculate that the modified TTP induced by LPS might be released from RNA–protein complexes and preferentially detected by our TTP antibody. As the modification of TTP leads to its dissociation from mRNAs and promotes mRNA stability, the decreased TTP modification in IRAK2-KD macrophages might be responsible for decreased cytokine or chemokine mRNA stability, such as KC and IL-6. Future studies are required to understand how the IRAK2 enzymatic activity is really involved in the posttranscriptional regulation of chemokines.

It is important to note that although the KK235AA mutation completely abolishes the kinase activity of IRAK2 (Fig. 1A), the inactivation of IRAK2 kinase activity did not completely impair the ability of IRAK2 to mediate the cytokine and chemokine production (Fig. 1B). Our previous study shows that IRAK4 kinase activity is essential for TLR-mediated cytokine and chemokine mRNA stabilization (Kim and others 2007). Therefore, IRAK2 might also function as a structural molecule to recruit the downstream signaling components to IRAK4. We previously reported that IRAK2 is not required for either early or late LPS-induced NFκB activation, but the IRAK2 kinase activity has been shown to be essential for late NFκB activation in response to TLR2, TLR7, and TLR9 stimulation (data not shown). As the kinase activity of IRAK2 is important for cytokine and chemokine production in multiple TLR-mediated signaling pathways, IRAK2 might be a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by Program Project Grants (PPG) PO1 HL 029582-26 (to P.E.D, P.L.F, J.D.S. and X.L.).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

- Akira S. Takeda K. Toll-like receptors: critical proteins linking innate and acquired immunity. Nat Immunol. 2001;2(8):675–680. doi: 10.1038/90609. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson P. Post-transcriptional control of cytokine production. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(4):353–359. doi: 10.1038/ni1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brook M. Tchen CR. Posttranslational regulation of tristetraprolin subcellular localization and protein stability by p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(6):2408–2418. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2408-2418.2006. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Z. Henzel WJ. IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Science. 1996;271(5252):1128–1131. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5252.1128. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caput D. Beutler B. Identification of a common nucleotide sequence in the 3′-untranslated region of mRNA molecules specifying inflammatory mediators. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83(6):1670–1674. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.6.1670. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang TH. Ulevitch RJ. Cloning and characterization of a sub-family of human toll-like receptors: hTLR7, hTLR8 and hTLR9. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2000;11(3):372–378. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta S. Biswas R. Tristetraprolin regulates CXCL1 (KC) mRNA stability. J Immunol. 2008;180(4):2545–2552. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.4.2545. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng L. Wang C. Activation of the IkappaB kinase complex by TRAF6 requires a dimeric ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex and a unique polyubiquitin chain. Cell. 2000;103(2):351–361. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00126-4. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga R. Hunter T. MNK1, a new MAP kinase-activated protein kinase, isolated by a novel expression screening method for identifying protein kinase substrates. EMBO J. 1997;16(8):1921–1933. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.1921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartupee J. Li X. Interleukin 1alpha-induced NFkappaB activation and chemokine mRNA stabilization diverge at IRAK1. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):15689–15693. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801346200. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hemmi H. Takeuchi O. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408(6813):740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitti E. Iakovleva T. Mitogen-activated protein kinase-activated protein kinase 2 regulates tumor necrosis factor mRNA stability and translation mainly by altering tristetraprolin expression, stability, and binding to adenine/uridine-rich element. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26(6):2399–2407. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.6.2399-2407.2006. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssens S. Beyaert R. Functional diversity and regulation of different interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase (IRAK) family members. Mol Cell. 2003;11(2):293–302. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00053-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawagoe T. Sato S. Sequential control of Toll-like receptor-dependent responses by IRAK1 and IRAK2. Nat Immunol. 2008;9(6):684–691. doi: 10.1038/ni.1606. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim TW. Staschke K. A critical role for IRAK4 kinase activity in Toll-like receptor-mediated innate immunity. J Exp Med. 2007;204(5):1025–1036. doi: 10.1084/jem.20061825. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medzhitov R. Preston-Hurlburt P. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388(6640):394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ninomiya-Tsuji J. Kishimoto K. The kinase TAK1 can activate the NIK-I kappaB as well as the MAP kinase cascade in the IL-1 signalling pathway. Nature. 1999;398(6724):252–256. doi: 10.1038/18465. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rock FL. Hardiman G. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95(2):588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.588. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronkina N. Kotlyarov A. The mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK)-activated protein kinases MK2 and MK3 cooperate in stimulation of tumor necrosis factor biosynthesis and stabilization of p38 MAPK. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(1):170–181. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01456-06. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowlett RM. Chrestensen CA. MNK kinases regulate multiple TLR pathways and innate proinflammatory cytokines in macrophages. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294(2):G452–G459. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00077.2007. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw G. Kamen R. A conserved AU sequence from the 3′ untranslated region of GM-CSF mRNA mediates selective mRNA degradation. Cell. 1986;46(5):659–667. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90341-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi O. Kawai T. TLR6: a novel member of an expanding toll-like receptor family. Gene. 1999;231(1–2):59–65. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(99)00098-0. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueda T. Watanabe-Fukunaga R. Mnk2 and Mnk1 are essential for constitutive and inducible phosphorylation of eukaryotic initiation factor 4E but not for cell growth or development. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(15):6539–6549. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.15.6539-6549.2004. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan Y. Xiao H. Interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinase 2 is critical for lipopolysaccharide-mediated post-transcriptional control. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(16):10367–10375. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M807822200. and others. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang D. Zhang G. A toll-like receptor that prevents infection by uropathogenic bacteria. Science. 2004;303(5663):1522–1526. doi: 10.1126/science.1094351. and others. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]