Abstract

Purpose

We performed a phase II study of oral vorinostat, a histone and protein deacetylase inhibitor, to examine its efficacy and tolerability in patients with relapsed/refractory indolent lymphoma.

Patients and Methods

In this open label phase II study (NCT00253630), patients with relapsed/refractory follicular lymphoma (FL), marginal zone lymphoma (MZL), or mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), with ≤ 4 prior therapies were eligible. Oral vorinostat was administered at a dose of 200 mg twice daily on days 1 through 14 of a 21-day cycle until progression or unacceptable toxicity. The primary end point was objective response rate (ORR), with secondary end points of progression-free survival (PFS), time to progression, duration of response, safety, and tolerability.

Results

All 35 eligible patients were evaluable for response. The median number of vorinostat cycles received was nine. ORR was 29% (five complete responses [CR] and five partial responses [PR]). For 17 patients with FL, ORR was 47% (four CR, four PR). There were two of nine responders with MZL (one CR, one PR), and no formal responders among the nine patients with MCL, although one patient maintained stable disease for 26 months. Median PFS was 15.6 months for patients with FL, 5.9 months for MCL, and 18.8 months for MZL. The drug was well-tolerated over long periods of treatment, with the most common grade 3 adverse events being thrombocytopenia, anemia, leucopenia, and fatigue.

Conclusion

Oral vorinostat is a promising agent in FL and MZL, with an acceptable safety profile. Further studies in combination with other active agents in this setting are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

While much progress has been made in the treatment of indolent lymphoma over the past few years, the high recurrence rate necessitates investigation of novel approaches for both first-line and salvage therapy. Patients with low-grade lymphomas tend to respond initially to approaches as disparate as watchful waiting, anthracycline-based chemotherapy (in conjunction with cyclophosphamide1 or fludarabine2,3), stem-cell transplant,4,5 or more recently, bendamustine6,7; however, the lymphoma recurs in the majority of patients within 5 years. On recurrence, remissions can be achieved with further chemotherapy, but the disease-free intervals tend to be shorter with each line of treatment.1 Allogeneic transplant has been successful in selected patients, but with greater treatment-related mortality,5 while autologous high-dose therapy, with or without the addition of high-dose radiolabeled antibodies has not been curative.8 In recent years, the addition of rituximab, a targeted antibody, has improved initial responses to chemotherapy7,9 and bendamustine has shown impressive single-agent activity,7 but ultimately most patients still recur. Given that the majority of patients relapse and require several lines of therapy, it is imperative that multiple classes of effective agents be available for sequential and combination therapies.

There is good preclinical evidence to support the use of histone deacetylase inhibitors (HDACi) in lymphoid malignancies. HDACi have been shown to affect a host of cellular targets and processes that might lead to antitumor activity in lymphoid malignancies, including angiogenesis, apoptosis, the cell cycle, and tumor immunology.10–13 Relevant specific targets whose levels or acetylation are affected by this class of agents include p53, gadd45, p21waf-1/cip1, hsp90, as well as various pro-inflammatory cytokines.14–16 B-cell tumor lines are more sensitive to vorinostat than solid tumor lines in vitro.17

Vorinostat (suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid), approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2006 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma, is an orally bioavailable synthetic hydroxamic acid class HDACi with both histone and protein deacetylase activity.18 In clinical trials, responses among patients with lymphoid malignancies are prominent. In the initial phase I study using intravenous vorinostat, of the four responders, two were patients with lymphoma.19 In a phase I study of oral vorinostat in Japanese patients with lymphoma, responses were seen in three of four treated patients with follicular lymphoma and one of two treated patients with mantle cell lymphoma.20

We report results of a phase II study of vorinostat at 200 mg orally, twice daily, on a 2-week-on, 1-week-off schedule. Included in this cohort are patients with follicular lymphoma, marginal zone B cell lymphoma, and mantle-cell lymphoma, who have recurred after rituximab and/or chemotherapy.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

All accrued patients signed an informed consent, according to the Declaration of Helsinki. The City of Hope institutional review board approved this trial in accord with an assurance filed with and approved by the Department of Health and Human Services.

Patient Eligibility

Patients older than age 18 years were eligible if they had histologically or cytologically confirmed relapsed/refractory indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Included in this category were relapsed or refractory follicular center lymphomas of any grade, marginal zone B cell lymphoma (including both nodal and extranodal disease), and mantle cell lymphoma. Patients may have had up to four prior chemotherapeutic or radioimmunoconjugate-containing regimens; however, steroids alone, rituximab, or local radiation did not count as regimens. Patients who had had chemotherapy within 4 weeks, rituximab within 3 months (unless there was evidence of progression), radiotherapy within 2 weeks, or those who had not recovered from adverse events due to agents administered more than 4 weeks earlier, were excluded. Demonstration of recurrent disease, progression, or persistence after the most recent line of therapy was required for eligibility. Patients with Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group status lower than 2, absolute neutrophil count (ANC) higher than 1,000/μL, platelet counts higher than 100,000/μL, creatinine ≤ 2 mg/dL, and liver function tests lower than 2.5 times normal were eligible.

Treatment Plan

One cycle of therapy was defined as: vorinostat 200 mg twice daily administered orally for 14 days followed by a 7-day break on a 21-day cycle for the first cycle. Radiologic assessment by computed tomography (CT) and/or positron emission tomography (PET) scan was performed at baseline and after every three cycles. Response was assessed by standard criteria.21,22 Patients with measurable response or stable disease were permitted to continue vorinostat until progression. Patients who achieved complete response (CR) were treated with two further cycles of vorinostat and then observed after discontinuation. Patients who achieved CR and completed treatment as described were allowed to be restarted on drug in the event of relapse 6 months or longer from the time of initial CR, given the chronic relapsing nature of indolent lymphomas. Compliance with treatment was monitored by use of drug diaries.

Toxicity was assessed on days 1 and 8 of every cycle, and graded using the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 3.0. Treatment was held for patients who presented with nonhematologic toxicity of grade 3 or 4, until toxicity resolved to below grade 2. These patients were restarted at 100 mg daily less than their previous dose. If grade 3 or greater toxicity occurred at that dose, the patient was taken off the drug.

Dose was decreased by 100 mg daily less than their previous dose for patients who presented to treatment and were found to have ANC ≥ 500/μL, but ≤ 1,000/μL, or platelet counts ≥ 50,000, but ≤ 75,000/μL. This dose reduction was reversible with normalization of counts. For patients who presented with hematologic toxicity of ANC lower than 500/μL, or platelet count lower than 50,000/μL, dose was held until recovery to ANC higher than 1,000/μL or platelet count higher than 50,000/μL; if it lasted longer than 1 week, the drug would be restarted at 100 mg daily less than their previous dose. If this dose also lead to ANC lower than 500/μL or platelet count lower than 50,000/μL, than the patient was removed from study.

Patients already on erythropoeitin or aranesp for lymphoma-related anemia were allowed to continue use of these agents but these were not permitted to be started during therapy. Use of granulocyte colony-stimulating factor or granulocyte-macrophage colony stimulating factor was not allowed during this study.

Patient Evaluation

Pretreatment evaluation consisted of history and physical examination, assessment of performance status, CBC, hepatic and renal function tests. Laboratory tests, history and physical examination, and performance status assessment were repeated on day 1 of each cycle. Women of reproductive age underwent a serum pregnancy test. CT (or optional PET-CT) was obtained at baseline and every three cycles to assess response. Bone marrow biopsy for presence of marrow involvement was done at baseline and every three cycles if baseline exam revealed marrow involvement. Responses were assessed according to the International Harmonization Project criteria.21,22

Study Design

Response rate (CR + partial response [PR]) was the primary end point. The two-stage optimum design by Simon was used. In the first stage, 17 patients were enrolled, with the design such that if four or more patients achieved CR or PR, accrual would continue to a total of 33 patients, with 10 or more responses regarded as evidence of sufficient activity to warrant further investigation. An underlying 20% response rate would be regarded as not sufficiently active, with the trial designed to have little chance of missing a 40% response rate. If the true response rate were 20%, the proposed design had a 90% chance of declaring vorinostat insufficiently active, and a 55% chance of stopping early. If the true response rate were 40%, there would be an 89% chance of concluding vorinostat sufficiently active. All patients beginning vorinostat therapy were included in response rates calculations. As mantle-cell lymphoma was considered an indolent lymphoma at the time of study design, all eligible histologies were included in the primary response evaluation, although individual histologies were analyzed as part of the secondary analysis.

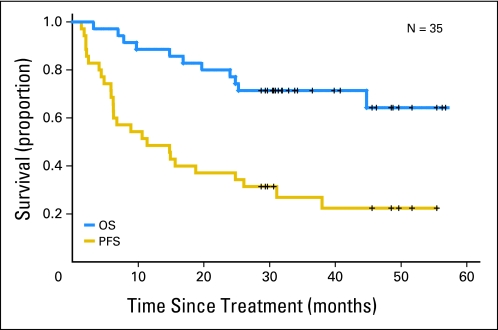

Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) were also secondary end points. Survival estimates were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier product-limit method; 95% CIs were calculated using the logit transformation and the Greenwood variance estimate.23 OS was measured from the day of initial protocol treatment to death from any cause. PFS was defined as time from initial protocol treatment to progression, relapse, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

A total of 37 patients were enrolled in the study between September 2005 and January 2008 (Table 1). Two enrolled patients were ineligible due to diffuse B-cell lymphoma at start of treatment. Treatment was changed for these ineligible patients (within 2 months of enrollment) before a response evaluation. The patients were replaced and they are not included in the analysis. In the 35 eligible patients (12 female, 23 male), the median age at treatment was 65 years (range, 32 to 79). Histologies represented included mantle cell in nine patients, marginal zone lymphoma in nine patients, and follicular lymphoma in 17 patients, of whom four were grade 1, six were grade 2, six were grade 3, and there was one follicular lymphoma of unknown grade. Previous treatments included rituximab in 36 of 37 patients, radiolabeled antibodies in three patients, autologous stem-cell transplant in eight patients, and local radiation in 10 patients. Twenty-seven patients received anthracycline-containing regimens as part of their previous treatment. Overall prior treatments received before study enrollment included: rituximab only (n = 2), one line of chemotherapy (n = 9), two lines chemotherapy (n = 7), three lines chemotherapy (n = 11), four lines chemotherapy (n = 6).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Characteristic | No. | % |

|---|---|---|

| Eligible patients | 35 | |

| Age, years | ||

| Median | 64.5 | |

| Range | 32-79 | |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 23 | |

| Female | 12 | |

| Karnofsky score | ||

| Median | 90 | |

| Range | 70-100 | |

| Ann Arbor clinical stage | ||

| I | 1 | |

| II | 6 | |

| III | 13 | |

| IV | 15 | |

| LDH level | ||

| Median | 486 | |

| Range | 235-890 | |

| LDH elevated | 10 | 29 |

| FLIPI | ||

| I | 2 | |

| II | 5 | |

| III | 4 | |

| IV | 6 | |

| Median | 3 | |

| Marrow involvement | 12 | 34 |

| Histological subtype | ||

| Follicular | ||

| Total | 17 | |

| I | 5 | |

| II | 6 | |

| III | 6 | |

| Mantle cell | 9 | |

| Marginal zone | 9 | |

| Prior therapies | ||

| Autologous transplant | 8 | |

| Radioimmunotherapy | 3 | |

| Rituximab | 34 | |

| No. of prior chemotherapy regimens | ||

| Median | 2 | |

| Range | 0-4* | |

Abbreviations: LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (for follicular lymphoma patients only).

Two patients received prior rituximab monotherapy alone.

Treatment and Toxicities

The median duration of treatment was 6 months; with a maximum of 49+ months (one patient still on therapy). Disease progression was the most common cause for discontinuation of therapy, with 22 patients stopping therapy due to progression, three due to toxicities, one due to intercurrent unrelated illness, four due to either patient or physician preference, and four others discontinuing after attaining a complete response. Of the three patients who stopped due to toxicity, one was due to grade 3 fatigue after 10 courses, one for a grade 4 thrombosis after five courses, and one for a combination of grade 2 diarrhea and grade 2 dizziness after two courses. The most common grade 3 to 4 toxicities seen were thrombocytopenia, anemia, leukopenia, and fatigue (Table 2).

Table 2.

Toxicities

| Treatment-Related Toxicities by Grade (possible) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adverse Event | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3/4 (%) |

| ANC | 7 | 4 | 2 | 17 |

| AST/ALT | 2 | — | — | — |

| Anorexia | 6 | 1 | — | 3 |

| Bicarbonate, serum low | 1 | — | — | — |

| Constipation | — | — | — | — |

| Creatinine | 4 | — | — | — |

| Dehydration | — | — | — | — |

| Diarrhea | 6 | — | — | — |

| Distension/bloating | 1 | — | — | — |

| Dizziness | 3 | — | — | — |

| Dry mouth/salivary gland | 2 | — | — | — |

| Dry skin | 3 | — | — | — |

| Dysphagia | 1 | — | — | — |

| Dyspnea | 2 | — | — | — |

| Fatigue | 13 | 3 | — | 9 |

| Hyperglycemia | 1 | — | — | — |

| Headache | 2 | — | — | — |

| Heartburn/dyspepsia | 1 | — | — | — |

| Hemoglobin | 6 | 4 | — | 11 |

| Hemorrhage, GU (vagina) | 1 | — | — | — |

| Hot flashes/flushes | 1 | — | — | — |

| Hypertension | 1 | — | — | — |

| Hypokalemia | — | 1 | — | 3 |

| Hyponatremia | — | 1 | — | 3 |

| Hypophosphatemia | 7 | 2 | — | 6 |

| Hypotension | 3 | — | — | — |

| Infection | ||||

| With grade 3 or 4 ANC | 2 | — | — | — |

| With < grade 3 ANC | 6 | — | — | — |

| Skin (cellulitis) | — | 1 | — | 3 |

| INR | — | 2 | — | 6 |

| Leukocytes (total WBC) | 5 | 3 | 1 | 11 |

| Lymphopenia | 3 | 4 | 1 | 14 |

| Myalgia | 2 | 1 | — | 3 |

| Mucositis/stomatitis | 1 | 1 | — | 3 |

| Muscle weakness (not neurologic) | 3 | — | — | — |

| Nail changes | 1 | — | — | — |

| Nausea/vomiting | 9 | — | — | — |

| Neuropathy: sensory | 1 | — | — | — |

| Pain (not muscle or headache) | 5 | — | — | — |

| Palpitations | 1 | — | — | — |

| Platelets | 4 | 3 | 7 | 29 |

| Pneumonitis/pulmonary infiltrate | 1 | — | — | — |

| Rash/desquamation | 1 | — | — | — |

| Somnolence | 1 | — | — | — |

| Supraventricular/nodal arrhythmia | 2 | — | — | — |

| Taste alteration | 2 | — | — | — |

| Thrombosis/thrombus/embolism | — | 1 | 1 | 6 |

Abbreviations: ANC, absolute neutrophil count; GU, genitourinary; INR, international normalized ratio for coagulant response time.

Efficacy

All 35 of the eligible patients were evaluable for response. The median number of cycles received was nine (range, two to 67). Response rates for the overall population and each disease grouping are given in Table 3. There were 10 of 35 formal responses, with five CRs (14%) noted and five PRs (14%), giving a formal overall response rate of 29% (95% CI, 0.15 to 0.46). Figure 1 shows OS and PFS for the total patient population. The 2-year OS for the total population was 77% (95% CI, 0.64 to 0.92) and the 2-year PFS was 37% (95% CI, 0.24 to 0.57). Seventeen patients with follicular lymphoma were treated on study; in this population there were four CRs and four PRs leading to a response rate of 47% for follicular lymphoma. The median PFS for patients with follicular lymphoma was 15.6 months (95% CI, 6.2 to not reached [NR]), with a 6-month PFS of 71% (Fig 2A). There were two responders among the nine patients with marginal zone lymphoma, one CR and one PR (the PR patient had clearance of lesions by CT-PET, but persistence in marrow), a response rate of 22% for marginal zone lymphoma. The median PFS for the patients with marginal zone lymphoma was 18.8 months (95% CI, 2.1 to NR), with a 6-month PFS of 89% (Fig 2A). There were no formal responses among the nine patients with mantle cell lymphoma, although one patient maintained stable disease for 26 months (37 cycles). The median PFS for patients with mantle cell lymphoma was 5.9 months (95% CI, 2.1 to NR), with a 6-month PFS of 44% (Fig 2A). Only for mantle cell lymphoma did OS reach a median, of 16.9 months (95% CI, 9.8 to NR) as illustrated in Figure 2B.

Table 3.

Efficacy

| Best Response | All Patients | Follicular | Mantle Cell | Marginal Zone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CR | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| PR | 5 | 4 | 0 | 1 |

| SD | 18 | 7 | 6 | 5 |

| PD | 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| NA | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviations: CR, complete response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; PD, progressive disease; NA, not available.

Fig 1.

Survival for total population. Overall survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) estimates were calculated for the entire patient population (N = 35). PFS is defined as the time from treatment to relapse, progression, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

Fig 2.

Survival stratified by histology. (A) Overall and (B) progression-free survival estimates were calculated for the three histological populations: marginal zone (n = 9), follicular (n = 17), and mantle cell (n = 9). Progression-free survival is defined as the time from treatment to relapse, progression, or death from any cause, whichever occurred first.

Four of the patients with PR as best response subsequently progressed (at 4, 5, 9, and 18 months after achieving PR), and one patient with marginal zone lymphoma continues to be in PR 40 months after achieving a PR. Four of the patients who achieved CR remained in CR at 49, 41, 23, and 23 months. One patient who achieved CR, relapsed after 27 months (Table 4). The median PFS for responders was 38 months. Notably, the onset of response was typically preceded by a long period of disease stabilization; in one case the patient had stable disease for close to 2 years and then developed CR based on CT scan. For all responders the median time to best response was 6.5 months (range, 2 to 26), and the median duration of response was 27 months.

Table 4.

Responders

| Patient No.* | Histology | FLIPI | No. Priors | Best Response | Time to Best Response | Duration of Response | PFS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | FL Gr 2 | 3 | 3 | PR | 6 | 9 | 15 |

| 3 | FL Gr 2 | 1 | 1 | CR | 6 | 49+ | 55+ |

| 4 | FL Gr 3 | 4 | 3 | PR | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| 9 | MZL | NA | 1 | PR | 10 | 40+ | 50+ |

| 10 | MZL | NA | 3 | CR | 26 | 23+ | 48+ |

| 13 | FL Gr 2 | 2 | 1 | CR | 5 | 41+ | 46+ |

| 15 | FL Gr 3 | 2 | 2 | PR | 20 | 18 | 38 |

| 17 | FL Gr 2 | 2 | 3 | CR | 4 | 27 | 31 |

| 24 | FL Gr 3 | 2 | 3 | PR | 11 | 5 | 16 |

| 36 | FL Gr 2 | 4 | 1 | CR | 7 | 23+ | 30+ |

Abbreviations: FLIPI, Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index; PFS, progression-free survival; FL, follicular lymphoma; Gr, grade; PR, partial response; CR, complete response; MZL, marginal zone lymphoma; NA, not available.

For all responders, median duration of response was 27 months, median time to best response was 6.5 months (range, 2 to 26 months), and median PFS for responders was 38 months.

DISCUSSION

Vorinostat is an oral HDAC inhibitor with activity against class I and II histone deacetylases, approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2006 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Given the interesting preclinical and clinical activity of this class of drugs in lymphoid malignancy, we conducted a phase II study of vorinostat as a single agent in indolent lymphoma. Given the biology of indolent lymphoma, we hypothesized that a dosing regimen that maintained adequate levels of drug with minimal toxicity would be best, and thus chose the 200 mg oral twice-daily schedule, which had been well-tolerated and effective in the phase I study.

In this trial, we saw formal responses in relapsed patients with follicular and marginal zone lymphoma (eight of 17 patients with follicular lymphoma, two of nine patients with marginal zone lymphoma), but no formal responses among the patients with mantle cell lymphoma. Noteworthy are the prolonged PFSs for all groups, with a median of 15.6 months for follicular lymphoma, 5.9 months for mantle cell lymphoma (with one patient experiencing stable disease for 28 months), and a median PFS for marginal zone lymphoma of 18.8, suggesting that disease progression is slowed even in the absence of formal response.

The patient population was fairly heavily pretreated as compared to the usual patients with this disease (seven patients with three prior lines of therapy, and three with four prior lines of therapy), with responses seen in patients who had progressed after salvage therapies including autologous transplant, and all patients except one having previously received rituximab. This suggests that resistance to chemotherapy or rituximab does not predict resistance to vorinostat, which may be crucial in this population, given that patients with follicular lymphoma generally require a series of treatment regimens over time.

Overall, the drug was well-tolerated for extended treatment durations; multiple patients have been able to stay on therapy for several years, with little impact on their daily outpatient lives. Adverse events were similar to those seen in other studies and did not seem to increase with the number of cycles. It is of note that formal responses generally required many cycles with prolonged periods of stable disease. This phenomenon may be akin to that seen with another class of clinical epigenetic agents, the hypomethylating agents in myelodysplastic syndrome, which typically show benefit after multiple cycles and manifest clinical activity largely by slowing progression of disease.

There are several mechanistic explanations for the activity of vorinostat particularly in the follicular B-cell lymphomas. Vorinostat is an epigenetic drug, with activity against both class I and class II deacetylases, affecting acetylation of histones and other proteins. From an epigenetic perspective, HDACi have been shown to alter expression levels of several proteins involved in lymphoid malignancies, including myc, bcl-2, bcl-XL, and bcl-6, which may push the abnormal cells towards apoptosis.15 In addition, the growth of follicular lymphoma may be particularly dependent on the state of the microenvironment, with elevated levels of a number of cytokines seen in patients with follicular lymphoma.24 We have shown in a mouse model that the production of several of these cytokines, including interleukin-6, can be suppressed even with low doses of vorinostat.16 Thus, it is likely that the activity of HDACi in indolent lymphoma is related to effects on multiple pathways.

Another clinical trial with an HDACi, reported in abstract format, included patients with follicular lymphoma. In a phase II study of the isotype-selective HDACi MGCD0103, three PRs of 28 patients with follicular lymphoma were seen, whereas in a study of the broad spectrum HDAC inhibitor PCI-24781, of four patients with follicular lymphoma, one PR and one CR were seen.25,26

Recent data demonstrates promising activity in this patient population with novel agents such as bortezomib, lenalidomide, and bendamustine. Bendamustine, a novel alkylating agent, shows an impressive 82% overall response rate in patients with follicular lymphoma, with a duration of response in this group of 9 months.7 Responses are seen in six (27%) of 22 patients with follicular lymphoma grade 1 to 2 treated with daily oral lenalidomide at 25 mg, with a PFS for the entire group of 4.4 months, and an impressive median duration of response of over 16.5 months. Fewer patients with marginal zone lymphoma are included in the lenalidomide study, while patients with mantle cell and follicular grade 3 were excluded.27 Bortezomib at a 1.5 mg/m2 dose administered on days 1, 4, 11, and 18 of a 21-day cycle, to a group of patients similar to those in our study, yields a a formal response rate of 50% for mantle cell patients, and 50% in follicular lymphoma with prolonged treatment. The PFS for the group was 4.75 months.28 The results we report for single-agent vorinostat are in line with these novel approaches and suggest that we now have multiple therapeutic modalities to offer for these patients with indolent lymphoma.

In summary, this study demonstrates single-agent activity of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor, vorinostat, in relapsed or refractory follicular and marginal zone lymphoma, with a well-tolerated toxicity profile. Given this single agent activity, studies in combination with other agents such as rituximab, lenalidomide, bortezomib and bendamustine are warranted.

Acknowledgment

We thank the City of Hope staff and nurses without whom this work would not be possible, and Sandra Thomas, PhD, City of Hope, for assistance with manuscript preparation and review.

Footnotes

Supported by Grants No. U01-CA-62505 and N01-CM-62209 from the National Cancer Institute Cancer Therapy Evaluation Program and Grant No. P30-CA-033572 from the City of Hope.

Presented in part at the 49th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, December 8-11, 2007, Atlanta, GA, and the 50th annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology, December 6-9, 2008, San Francisco, CA.

Authors' disclosures of potential conflicts of interest and author contributions are found at the end of this article.

Clinical trial information can be found for the following: NCT00253630.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Although all authors completed the disclosure declaration, the following author(s) indicated a financial or other interest that is relevant to the subject matter under consideration in this article. Certain relationships marked with a “U” are those for which no compensation was received; those relationships marked with a “C” were compensated. For a detailed description of the disclosure categories, or for more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to the Author Disclosure Declaration and the Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest section in Information for Contributors.

Employment or Leadership Position: None Consultant or Advisory Role: Mark Kirschbaum, Merck (C); Paul Frankel, Merck (C); Auayporn Nademanee, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals (C), Allos Therapuetics (C), Genzyme (C); David Gandara, Amgen (C), AstraZeneca (C), Biodesix (C), Boehringer Ingelheim (C), Bristol-Meyers Squibb/Imclone Systems (C), Pfizer/Eli Lilly (U), GlaxoSmithKline (C), Genentech (C), Merck (C), Novartis (C), sanofi-aventis (C), Response Genetics (C) Stock Ownership: None Honoraria: Mark Kirschbaum, Merck; Jasmine Zain, Merck; Maria Delioukina, Merck, Eisai, Genentech; Auayporn Nademanee, Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Allos Therapuetics, Genzyme Research Funding: Mark Kirschbaum, Merck; David Gandara, Abbott, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Imclone Systems, Genentech, Eli Lilly, Merck, Novartis Expert Testimony: None Other Remuneration: None

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Mark Kirschbaum, Paul Frankel, David Gandara, Edward Newman

Provision of study materials or patients: Mark Kirschbaum, Leslie Popplewell, Jasmine Zain, Maria Delioukina, Vinod Pullarkat, Bernadette Pulone, Auayporn Nademanee, Stephen J. Forman, David Gandara

Collection and assembly of data: Mark Kirschbaum, Paul Frankel, Leslie Popplewell, Maria Delioukina, Vinod Pullarkat, Deron Matsuoka, Bernadette Pulone, Arnold J. Rotter

Data analysis and interpretation: Mark Kirschbaum, Paul Frankel, Arnold J. Rotter, Igor Espinoza-Delgado, Edward Newman, Stephen J. Forman

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

REFERENCES

- 1.Dana BW, Dahlberg S, Nathwani BN, et al. Long-term follow-up of patients with low-grade malignant lymphomas treated with doxorubicin-based chemotherapy or chemoimmunotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1993;11:644–651. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.4.644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Klasa RJ, Meyer RM, Shustik C, et al. Randomized phase III study of fludarabine phosphate versus cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone in patients with recurrent low-grade non-Hodgkin's lymphoma previously treated with an alkylating agent or alkylator-containing regimen. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:4649–4654. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.11.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Velasquez WS, Lew D, Grogan TM, et al. Combination of fludarabine and mitoxantrone in untreated stages III and IV low-grade lymphoma: S9501. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:1996–2003. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bierman PJ, Sweetenham JW, Loberiza FR, Jr, et al. Syngeneic hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation for non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: A comparison with allogeneic and autologous transplantation–The Lymphoma Working Committee of the International Bone Marrow Transplant Registry and the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3744–3753. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.08.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Besien K, Loberiza FR, Jr, Bajorunaite R, et al. Comparison of autologous and allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for follicular lymphoma. Blood. 2003;102:3521–3529. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-04-1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robinson KS, Williams ME, van der Jagt RH, et al. Phase II multicenter study of bendamustine plus rituximab in patients with relapsed indolent B-cell and mantle cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4473–4479. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Friedberg JW, Cohen P, Chen L, et al. Bendamustine in patients with rituximab-refractory indolent and transformed non-Hodgkin's lymphoma: Results from a phase II multicenter, single-agent study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:204–210. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.5070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gopal AK, Gooley TA, Maloney DG, et al. High-dose radioimmunotherapy versus conventional high-dose therapy and autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for relapsed follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma: A multivariable cohort analysis. Blood. 2003;102:2351–2357. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Czuczman MS, Weaver R, Alkuzweny B, et al. Prolonged clinical and molecular remission in patients with low-grade or follicular non-Hodgkin's lymphoma treated with rituximab plus CHOP chemotherapy: 9-year follow-up. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4711–4716. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhao Y, Lu S, Wu L, et al. Acetylation of p53 at lysine 373/382 by the histone deacetylase inhibitor depsipeptide induces expression of p21(Waf1/Cip1) Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:2782–2790. doi: 10.1128/MCB.26.7.2782-2790.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ellis L, Hammers H, Pili R. Targeting tumor angiogenesis with histone deacetylase inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:145–153. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maeda T, Towatari M, Kosugi H, et al. Up-regulation of costimulatory/adhesion molecules by histone deacetylase inhibitors in acute myeloid leukemia cells. Blood. 2000;96:3847–3856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frew AJ, Johnstone RW, Bolden JE. Enhancing the apoptotic and therapeutic effects of HDAC inhibitors. Cancer Lett. 2009;280:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.02.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Richon VM, Sandhoff TW, Rifkind RA, et al. Histone deacetylase inhibitor selectively induces p21WAF1 expression and gene-associated histone acetylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:10014–10019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180316197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scuto A, Kirschbaum M, Kowolik C, et al. The novel histone deacetylase inhibitor LBH589, induces expression of DNA damage response genes and apoptosis in Ph- acute lymphoblastic leukemia cells. Blood. 2008;111:5093–5100. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-10-117762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li N, Zhao D, Kirschbaum M, et al. HDAC inhibitor reduces cytokine storm and facilitates induction of chimerism that reverses lupus in anti-CD3 conditioning regimen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:4796–4801. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712051105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Richardson PG, et al. Molecular sequelae of histone deacetylase inhibition in human malignant B cells. Blood. 2003;101:4055–4062. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xu WS, Parmigiani RB, Marks PA. Histone deacetylase inhibitors: Molecular mechanisms of action. Oncogene. 2007;26:5541–5552. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kelly WK, Richon VM, O'Connor O, et al. Phase I clinical trial of histone deacetylase inhibitor: Suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid administered intravenously. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:3578–3588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Watanabe T, Kato H, Kobayashi Y, et al. Potential efficacy of the oral histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat in a phase I trial in follicular and mantle cell lymphoma. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2009.01360.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cheson BD. The International Harmonization Project for response criteria in lymphoma clinical trials. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2007;21:841–854. doi: 10.1016/j.hoc.2007.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheson BD, Horning SJ, Coiffier B, et al. Report of an international workshop to standardize response criteria for non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: NCI sponsored International Working Group. J Clin Oncol. 1999;17:1244. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1999.17.4.1244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical methods in cancer research: Volume II, the design and analysis of cohort studies. IARC Sci Publ. 1987;82:1–406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Labidi SI, Menetrier-Caux C, Chabaud S, et al. Serum cytokines in follicular lymphoma: Correlation of TGF-beta and VEGF with survival. Ann Hematol. 2010;89:25–33. doi: 10.1007/s00277-009-0777-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martell RE, Younes A, Assouline SE, et al. Phase II study of MGCD0103 in patients with relapsed follicular lymphoma (FL): Study reinitiation and update of clinical efficacy and safety. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl; abstr 8086):594s. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Evens AM, Ai W, Balasubramanian S, et al. Phase I analysis of the safety and pharmacodynamics of the novel broad spectrum histone deacetylase inhibitor (HDACi) PCI-24781 in relapsed and refractory lymphoma. Blood. 2009;114 abstr 2726. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Witzig TE, Wiernik PH, Moore T, et al. Lenalidomide oral monotherapy produces durable responses in relapsed or refractory indolent non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5404–5409. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Connor OA, Portlock C, Moskowitz C, et al. Time to treatment response in patients with follicular lymphoma treated with bortezomib is longer compared with other histologic subtypes. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:719–726. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]