Abstract

This paper examines whether children of marginalized racial/ethnic groups have an awareness of race at earlier ages than youth from non-marginalized groups, documents their experiences with racial discrimination, and utilizes a modified racism-related stress model to explore the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem. Data were collected for non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white, and Hispanic children aged 7 – 12 using face-to-face interviews (n = 175). The concept of race was measured by assessing whether children could define race, if not a standard definition was provided. Racial discrimination was measured using the Williams Every-day-Discrimination Scale, self-esteem was measured using the Rosenberg Scale, and ethnic identity was assessed using the Multi-group Ethnic Identity Measure. Non-Hispanic black children were able to define race more accurately, but overall, Hispanic children encountered more racial discrimination, with frequent reports of ethnic slurs. Additionally, after accounting for ethnic identity, perceived racial discrimination remained a salient stressor that contributed to low self-esteem.

Keywords: race, racism, children, ethnic-identity, self/other, ethnicity

INTRODUCTION

A substantial body of research on racial discrimination has linked it to many negative health outcomes (Brody et al. 2006;Clark et al. 2004;Connolly 2002; Fishbein 2002; Hughes and Johnson 2001; Nyborg and Curry 2003;Szalacha et al. 2003), however, few studies have investigated how race and racial discrimination are experienced by young children. The current research addresses these gaps in the literature with three main objectives: (1) to determine if there are racial differences in the awareness of race for children ages 7 to 12, (2) to examine the type of racial discrimination that children experience and (3) to explore if racial discrimination affects children's self-esteem after accounting for ethnic identity. In order to address these outcomes, an ethnically diverse group of young children—non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, and 1.5 to 2nd generation Hispanic—living in a mid-sized urban area in the Southeastern region participated in the research.

Systemic Nature of Racism

American racism should be viewed from a structural perspective, particularly as a set of racialized social systems created by white Americans to produce and maintain their privilege and status (Bell McDonald and Harvey Wingfield 2009;Bonilla-Silva 1997, 1999; Johnson and Rush 2000). These institutionalized systems create differential life chances and affect the social lives of majority and minority racial groups (Bell McDonald and Harvey Wingfield 2009;Bonilla-Silva 1997, 1999). The institutional nature of racism is so ingrained that it operates independently from individual actors and as such, has become more covert and often invisible to whites (Bonilla-Silva 1997; Johnson and Rush 2000). While covert, the institutional nature of racism is evident in the concentrated poverty among minority groups, residential segregation, unequal access to social and political resources, segregation in academically substandard schools, and continued health disparities between minority and majority groups (Bonilla-Silva 1999; Feagin and Sikes 1994;Williams and Collins 1995).

Awareness of Race among Young Children

Traditionally, researchers use dolls that represent different racial and ethnic groups to examine racial identity acquisition. These studies show that white children are able to identify their racial identity between ages four to six, whereas other racial/ethnic groups do not choose dolls that reflect their racial group until age seven (Fishbein 2002). The delay in appropriate doll selection for other racial and ethnic groups may not be a reflection of their racial awareness, but instead, may be an awareness of the value attached to whiteness. For example, between the ages four to six, black children develop a pro-white bias, with pro-black affinities developing between the ages of seven to ten, and finally more negative attitudes toward whites during the age range of fourteen to eighteen (Fishbein 2002). During field observations in London, Connolly (2002), noted that children as young as five downplayed their own South Asian identities in favor of whiteness and also criticized the ‘ethnic’ features of their counterparts.

When researchers conduct studies of skin color preference and prejudice among children, they frequently use the Color Meaning Test (CMT II) or the Preschool Racial Attitudes Measure II (PRAM II)(Connolly 2002;Williams and Roberson 1967;Williams et al. 1975). These instruments utilize vignettes and depictions of animals and humans. Response choices are forced choice options intended to capture negative terms or ideas associated with particular figures based on color. Researchers using the CMT II have consistently found that children aged three to five exhibit strong color preferences for white over black, which, in turn, may translate into negative assessments and interactions with darker-skinned individuals (Connolly 2002;Williams and Roberson 1967;Williams, Boswell, and Best 1975). While informative, the CMT II and PRAM II have limitations. First, they only measure perceptions of bias involving blacks and whites. It is important to depict other racial and ethnic groups in these figures given their growth in the United States. Second, these instruments do not ask children about their actual experiences with racial discrimination. With this lack of specificity, researchers can only speculate how a pro-white bias affects interactions between and within racial/ethnic groups. Third, the use of forced choice options may overestimate the prevalence of color bias and prejudice. As such, these instruments have important limitations.

Historically there may have been an assumption that children were unable to understand racial distinctions or deliberately utilize racially insensitive remarks (see (Van Ausdale and Feagin 2001) for discussion of linear development cognitive model). However, studies have found that children acquire an understanding of race and racial identity earlier than previously thought (Boocock and Scott 2005;Van Ausdale and Feagin 2001)). White children as young as six are aware of their racial identity, are more likely to assign positive features to whites, and by adolescence, white males are most likely to express racial prejudice (Fishbein 2002;Boocock and Scott 2005). The work of Van Ausdale and Feagin (2001) demonstrates that preschool children use racist language to produce harmful results, to evoke emotional reactions by victims, and to recreate social hierarchies.

Narratives charting children's self-separation by race, Van Ausdale and Feagin (2001), Connolly (2002), and Coppenhaver-Johnson (2006), show that children use race to establish dominance, maintain control, and reinforce segregation. When black first grade girls attempted to integrate the play groups of white girls, they were continuously rejected.As Connolly (2002; pp 5) notes, “some young children actively appropriate, rework, and reproduce discourses on ‘race’...in quite complex ways,” and more importantly this “has brought into question the appropriateness of making assumptions about children's cognitive ability or their level of awareness on matters of ‘race,’...simply by their age” (pp 128).

Experiences with Racial Discrimination

During elementary school, African Americans experience institutional and individual racism. In one longitudinal study ninety-two per cent of black children aged ten or younger, experienced racial discrimination (Brody et. al 2006). These encounters lead to emotional and mental harm and increase aggression and delinquency (Nyborg and Curry 2003; Ferguson 2000;Lewis 2003).

Hispanic children also experience racial discrimination with increased reports paralleling their growth in the United States (Fisher et al. 2000;Flores 2002;Romero and Roberts 2003). Hispanics primarily attribute discrimination to ethnicity, English language proficiency, and phenotypic traits (Araujo and Borrell 2006). Among a group of Puerto Rican children aged seven to nine living on the mainland of the United States, twelve per cent attributed discriminatory events to their ethnicity (Szalacha et al 2003). The National Survey of Latinos revealed that fifty-five per cent of Spanish language only Hispanics, thirty-eight per cent of bilinguals, and twenty-nine per cent of English language only Hispanics experienced discrimination. In the study conducted by Romero and Roberts (2003) at least fifty per cent of immigrant and U.S. born Mexican children reported racial/ethnic discrimination. However, higher perceived socioeconomic status (SES) operated as a protective factor against these encounters (Romero and Roberts 2003). Taken together these results indicate that Hispanic youth are exposed to social contexts that can be stigmatizing.

Racial Discrimination and Mental Health

Racial discrimination is a stressor that affects the self-esteem and mental health status of adults (Mossakowski 2003;Whitbeck et al. 2002;Williams et al. 2003), Insights from the mental health literature also show that among Mexican American adolescents, racial discrimination ranks is a significant risk factor for reduced self-esteem and depression (Romero and Roberts 2003). However, these effects may be partially moderated through a strong sense of ethnic identity and the presence of social support (Whitbeck et al. 2002;Williams and Williams-Morris 2000;Harris-Britt et al. 2007). While informative, a paucity of research that examines racial discrimination among young children remains.

Theoretical Framework

The racial socialization literature examines parental strategies of racial socialization for their children and this framework is informative for the first aim of this research. While racial socialization occurs among all families, this form of socialization may be salient for racial/ethnic minorities with histories of oppression and marginalization (Hughes 2003). The processes of racial socialization include messages and practices relevant to racial status (Thornton et al. 1990). From this literature, direct statements about race are the pertinent and it is hypothesized that racial/ethnic minority children will be more cognizant of the term race than their non-Hispanic white counterparts.

A modified version of the racism-related stress model developed by Harrell (2000) was used to examine the relationship between racial discrimination and mental health . The theoretical model consists of racial discrimination as a social stressor, antecedent variables, internal/external mediators, and mental health as an outcome. In the modified model, self-esteem is used as an outcome measure instead of an internal/external mediator.

Racial discrimination is conceptualized as interpersonal level unfair treatment based on one's race that results from interpersonal interactions (Harrell 2000). For this research, we are interested in racial discrimination micro-stressors, which refer to the daily reminders that one's own race/ethnicity is a ‘stimulus in the world’ (Harrell 2000). The resultant indignities experienced due to racial discrimination can threaten the body's physiological defenses and affect psychological, social and spiritual functioning (Harrell 2000;Myers et al. 1989).

Antecedent variables are personal and socioenvironmental factors that provide the social context for life experience and personal development (Harrell 2000). Antecedent variables include ethnicity, gender, age, and SES. Internal/external factors refer to individual-level and sociocultural factors that may moderate the effects of racial discrimination on psychological distress. Racial/ethnic identity is an internal factor and refers to the feelings, thoughts, behavior, and affinity for ethnic-specific group membership (Porter and Washington 1993; Spencer and Markstrom-Adams 1990; Harrell 2000). Ethnic identity can comprise family values, ethnic pride, such as language, and connectedness (Barry and Grilo 2003). Positive identification and affiliation with an ethnic group helps bolster one's own self-concept and provides a set of cultural norms and values to which one can adhere (Spencer and Markstrom-Adams 1990).

The outcome measure is self-esteem. It is suggested that discrimination can affect self-orientation and challenge the sense of self (Harrell 2000). According to Harrell (2000, pp. 50-51), three factors “1) reflected appraisals of negative and ethnocentric perceptions of others; 2) self-fulfilling prophecy; and 3) environmental barriers to self-efficacy” affect self-esteem. Two hypotheses examine the racism-related-stress model among young children; 1) racial discrimination will negatively affect self-esteem and 2) ethnic identity will mediate the effects of racial discrimination on self-esteem.

METHODS

Data from the Admixture Mapping for Ethnic, Racial, Insulin Complex Outcomes (AMERICO) conducted in the Birmingham-Hoover, Alabama metropolitan area are used for these analyses. This study is a federally funded project supported by the National Institutes of Health with the aim of understanding the genetic, environmental, and related comorbidities associated with pediatric metabolic outcomes. A substudy evaluated the sociostructural risk factors for metabolic health.

Due to the clinical nature of the larger study, involvement was voluntary and required the participation of both parents and children. The recruitment of participants included presentations at schools, advertisements in newspapers, wide-distribution mailers, free parenting magazines, radio advertisements on Spanish language radio stations, church presentations, posted flyers, and booths set up at health fairs and camp recruitment fairs. Both parents and children could withdraw from the study at anytime without penalties and both the parent and child received compensation for their participation.

During 2006 to mid-2007, one African American female interviewer who is bilingual in both English and Spanish conducted all of the interviews. Approximately ninety-five per cent of interviews with Hispanic parents requested Spanish language interviews and thirty-five per cent of the Hispanic children requested Spanish language interviews. All child interviews took place separately from those of the parents in order to maintain privacy. In addition, the interviewer instructed the child that he/she did not have to answer any interview questions that made them feel uncomfortable.

Pretesting Survey Instrument

Thirty children who participated in the study were pretested using the behavioral coding method (Presser and Blair 1994). Behavior codes notated on the survey indicated when the interviewer did not follow the exact wording of the questionnaire, a respondent required clarification, or the respondent had difficulty with a question. When questions had particularly high frequencies (e.g. fifteen per cent) of problems they were revised or omitted (Presser and Blair 1994). Although the concept of race emerged as problematic for some children (discussed in further detail in the measures section), none of the everyday discrimination scale items or other survey measures were problematic.

Sample Characteristics

All data collected for this sub-study were during the first visits, and as such no participants dropped out and none refused to answer any of the study questions. Participants consisted of 175 non-Hispanic black (n=57), non-Hispanic white (n=66), and Hispanic (n= 52) children aged seven to twelve years. The average ages of the sample was 9.72 years (non-Hispanic black), 9.74 years (non-Hispanic white), and 9.28 years (Hispanic). The sample was fifty per cent female. Participants were primarily from middle - and working-class socioeconomic backgrounds.

Measures

Awareness of race

The ability to define race was the dependent variable. The Williams Every-Day-Discrimination Scale was used to initiate this response (Williams et al. 1997). After reading the first item to the respondent, the interviewer prompted the child to define race. If the child could not define race, the interviewer provided a standard definition (black, white, or Hispanic). The simplistic wording of the definition took into account the ages of the respondents and the complications of defining the term “ethnicity/national origin” (which the authors acknowledge is more appropriate when discussing Hispanic ethnicity). Simplistic wording of racial definitions are common for younger children (Wardle et al. 2006). If the child required a definition of race, the interviewer notated the respondent's survey with an underline of the word race and a ‘y’ next to the term. After defining the term for the respondent, the interviewer provided an example of racial discrimination (e.g. people treat you differently because you are black, white, or Hispanic). After this, the interviewer administered the Williams Every-Day Discrimination Scale items.

If the respondent reported experiences of racial discrimination, they were prompted with the phrase, “can you tell me what happened?” If they were not comfortable recalling events (n = 4 Hispanic children, n = 1 European American child), they did not have to self-report the situation. This prompt validated that the children understood the meaning of race, could recall events that occurred, and insured that the experiences were their own and not encounters experienced by friends or family members. The examples of follow-up reports included, “I was told that I did not belong at the school because of my race, I was discriminated against because I speak Spanish, my friendship ended because of my race, I was told that I could not win at spelling because of my race, and people believe that I will fight a lot because of my race.”

Independent Variables

Racial Discrimination Measure

The Williams Every-Day-Discrimination Scale captured experiences with racial discrimination. The scale contained a list of response options for discriminatory occurrences including discrimination for gender, sexual orientation, and race. For the purposes of this research, only the race option was included with each scale item qualified by the term “because of your race.” This qualification is reliable for children (Clark, Coleman, and Novak 2004).

Respondents thought back over the past thirty days and responded to a series of ten questions. The sample questions included “you have been treated less well than other people because of your race,” “people have acted as if they think you are not smart because of your race,” “people have acted as if they are afraid of you because of your race,” and “you have been called names or insulted more than others because of your race.” Respondents noted whether they had never been treated this way = 0, one time =1, two to three times = 2, or three or more times = 3. Possible scores ranged from 0 to 30. While the Cronbach Alpha was high α = .83, the authors of the scale and other researchers suggest that this is not a good indicator for this measure because one encounter does not predispose an individual to other encounters (Clark, Coleman, and Novak 2004;Williams, Neighbors, and Jackson 2003).

Self-Esteem

The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale assessed overall self-esteem (Rosneberg 1965). This scale is unidimensional and assesses general self-worth (Butler and Gasson 2005;Rosenberg 1965). This measure is reliable and is valid among Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, and non-Hispanic white children (Lorenzo-Hernandez and Oullette 1998; McReary et al. 1996). The scale also demonstrates internal consistency when translated into Spanish (Lorenzo-Hernandez and Oullette 1998). There were five positively worded statements and five negatively worded statements (e.g. “On the whole, I like myself,” “At times, I think I am no good at all,” and “I am able to do things as well as most other people”). Response options used a Likert Scale ranging from ‘Strongly agree’ = 4 to ‘Strongly disagree’ = 1 with higher scores indicating higher self-esteem. The Cronbach's Alpha for the sample was α =.76.

Ethnic Identity

Ethnic identification was evaluated using the original ten-item Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) (Phinney 1992). This measure assessed how strongly an individual identified with his or her ethnic origin. The sample questions included “I am happy that I am (Hispanic American, African American, or European American),” “In order to learn more about my background I have often talked to other people about my culture and history,” “I have a lot of pride in my racial group and its accomplishments,” and “I participate in my cultural practices, such as special food, music, or customs.” Responses options used a Likert format ranging from ‘strongly agree’ = 4 to ‘strongly disagree = 1 with higher scores indicating stronger ethnic identity. This scale has been used among Hispanic, non-Hispanic white, and non-Hispanic black children (Homes and Lochman 2009;Roberts et al. 1999). The Cronbach's Alpha was α = .83.

Parents provided their child's age, male was coded 0 and female was coded as 1. SES was measured using the Hollingshead Four Factor Index (Hollingshead 1975). This 4-factor index combined educational attainment and occupational prestige for the number of working parents in the child's family. Scores ranged from 8 to 66, with higher scores indicating higher theoretical social status. The calculation method was applicable for one wage earner households. When the home had dual wage earners, the mean of the two scores provided a value for SES. For the unemployed (n = 2), their previous occupation was used to calculate occupational prestige.

Objective Neighborhood Characteristics

The work of William Julius Wilson (1996, 1987) provided a framework to calculate the index of objective neighborhood characteristics. Wilson highlights unemployment, poverty, female-headed households, and racial segregation of blacks as indicators of neighborhood disadvantage. Data obtained from census tract information captured the characteristics of neighborhoods (U.S. Census Bureau 2000). The individual percentages of unemployment, poverty, female-headed households, and racial segregation were divided by ten, summed across measures, and divided to obtain the mean. This scale had a reliability of α = .938.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics provided information across groups and ANOVA's determined if there were significant differences across the independent variables. Logistic regression examined the odds of accurately defining race and it examined whether there were racial/ethnic differences in awareness of the term. There were two categorical racial/ethnic variables—non-Hispanic black and Hispanic, with whites as the reference category for each group. Gender was a covariate because boys are more likely to experience racial discrimination and as a result may be more aware of race. Female was the referent category. We expected that males and older children would be more aware of race. Due to parsimony and a lack of significance, SES was not reported for the logistic regression model. ANOVAs examined the second aim of the study. Because means for separate scale items were relatively low, they violated assumptions of homoskedasticity. The variables were log transformed; however, means for scale items were zero for one or more racial/ethnic groups. As such, percentages for each item of the discrimination measure were presented.

To examine the third aim of the study, we used multiple regression. Exploratory analyses also controlled for school and neighborhood effects, however these factors were insignificant and excluded from the analytic models. Block entry method examined the impact of the independent variables on self-esteem. The first block included age, gender, and SES, the second block included racial discrimination, the third block included all previous variables and the ethnic identity measure, and the final block included the interaction term with the hypothesized moderator (racial discrimination x ethnic identity). Centering of variables eased interpretability of the results and reduced multicollinearity between the interaction term and the independent variables.

RESULTS

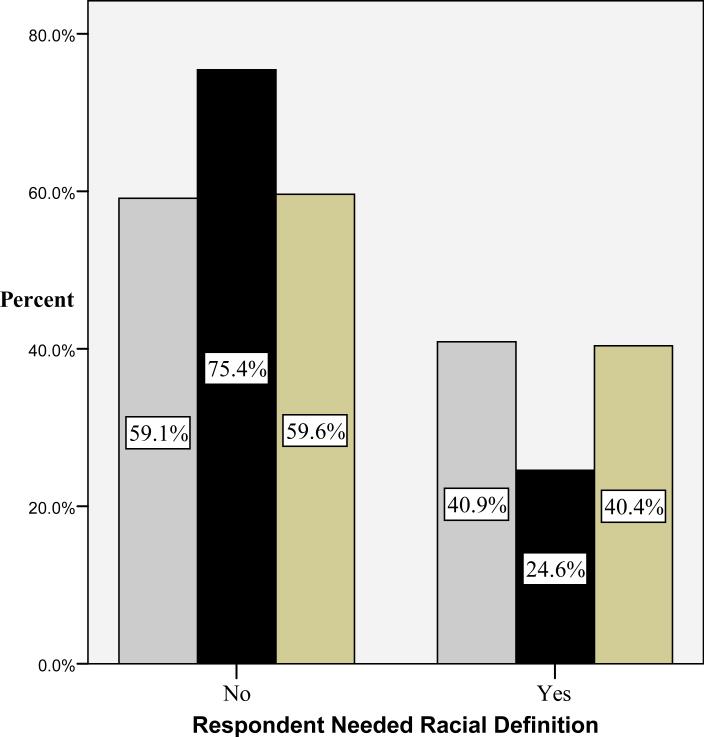

Figure 1 depicts the percentage of children by racial/ethnic group able to define race or, conversely, needing a definition. As this figure illustrates, non-Hispanic black children were less likely to require a definition of race, followed by Hispanic and non-Hispanic white children.

Figure 1.

Percentage of Children Requiring a Racial Definition, Presented by Child's Race/Ethnicity

Racial/Ethnic Group

non-Hispanic

non-Hispanic

white non-Hispanic black

white non-Hispanic black

Hispanic

Hispanic

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics by ethnicity. Overall, non-Hispanic white children reported significantly fewer encounters with racial discrimination (p<.05) and lower ethnic identity scores (p<.05) than Hispanic and non-Hispanic black children. Hispanic American children reported lower self-esteem (p<.05), than non-Hispanic black and non-Hispanic white children. All three groups were significantly different in SES (p<.05), with non-Hispanic whites of higher SES than their non-Hispanic black and Hispanic counterparts respectively. Non-Hispanic black children were more likely to live in neighborhoods of higher poverty, unemployment, single female-headed households with dependent children, and higher concentrations of blacks than their non-Hispanic white and Hispanic counterparts.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Sample Respondents by Ethnicity Means (Standard Deviation)

| Non-Hispanic Black (n = 57) | Hispanic (n = 52) | Non-Hispanic White (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perceived Racial Discrimination | 3.33(5.44)a | 4.60(5.68)a | .96(2.60)b |

| Self-Esteem | 31.19(4.16)a | 28.84(3.85)b | 31.17(4.51)a |

| Ethnic Identity | 30.28(4.72)a | 30.0(3.82)a | 27.16(5.30)b |

| Age | 9.69(1.44) | 9.3(1.44) | 9.73(1.75) |

| Gender (% female) | 50% | 49% | 49% |

| Socioeconomic Status | 37.89(11.84)a | 25.54(1120)b | 49.5(8.70)c |

| Neighborhoodd | |||

| Poverty | 17.48(15.50)a | 9.88(11.58)b | 9.75(9.78)b |

| Unemployment | 5.3(4.81)ab | 3.31(4.27)c | 2.60(1.83)abc |

| Female-headed households | 16.68(9.46)a | 11.04(8.16)b | 9.11(8.01)a |

| Black | 49.73(37.75)a | 18.26(23.02)b | 16.08(26.76)a |

denote significant differences at p<.01

denote significant differences at p<.01

denote significant differences at p<.01

Neighborhood denotes Census tract percentages of poverty, unemployment, female-headed households, and black race.

Table 2 shows the logistic regression results for being able to define race. Being a non-Hispanic black child was associated with a fifty-seven per cent less likelihood of requiring a definition of race in comparison to non-Hispanic white children (p<.05). While the direction of the data indicates boys were more likely to be aware of the concept of race than girls, the difference was not statistically significant. Younger age associated with a forty-eight per cent chance of requiring a definition of race. This difference was significant at the .01 level. The pseudo R2 suggested that the model accounted for approximately twenty-seven per cent of the variance in awareness of race as a concept.

Table 2.

Estimated Odds Ratios (OR) of Sociodemographic Factors on the Likelihood of Needing a Definition of Race

| Independent Variables | OR |

|---|---|

| Non-Hispanic blacka | .429* |

| Hispanica | .752 |

| Gender (female = 1) | .750 |

| Age | .517** |

| χ 2 | 39.09** |

| df | 4 |

| Nagelkerke R2 (pseudo R2) | 27.50% |

non-Hispanic white is the reference group

p<.05

p<.01

Table 3 presents the average every-day-discrimination scores calculated for each racial/ethnic group and the percentage frequency of each discriminatory event. Overall, Hispanic children had higher average reports of everyday discrimination and reported that they were treated less well and with less respect because of their race. Non-Hispanic black children reported that they received poorer service in stores because of their race. Hispanic children had greater reports that people thought that they were “not smart” because of their race. Non-Hispanic black children were 2.5 times more likely than Hispanic children to report that people were afraid of them because of their race, followed by non-Hispanic white children. Almost similar percentages of non-Hispanic black and Hispanic children reported that people thought that they were dishonest because of their race, with few non-Hispanic white children reporting this form of discrimination. Hispanic children reported that people thought that they were inferior because of their race and reported race-based name-calling. Additionally, more Hispanic children reported that they were threatened and/or bothered because of their race. Lastly, non-Hispanic black children had greater reports of store employees following them around in stores because of their race.

Table 3.

Children's Reports of Experiences with Racial Discrimination Expressed as P Percentages

| Non-Hispanic Black (n = 57) | Hispanic (n = 52) | Non-Hispanic White (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Williams Everyday Discrimination Scale | |||

| Treated less well* | 19.3 | 34.6 | 6.1 |

| Treated with less respect* | 12.3 | 30.8 | 4.5 |

| Received poorer service at stores* | 19.3 | 11.5 | 0.0 |

| People think you're not smart* | 23.8 | 35.6 | 6.1 |

| People are afraid of you* | 26.3 | 11.5 | 3.0 |

| People believe you are dishonest* | 21.1 | 19.2 | 6.1 |

| People think they're better than you* | 26.3 | 44.2 | 12.1 |

| You've been called names or insulted* | 17.5 | 28.8 | 7.6 |

| Threatened or bothered* | 14.0 | 19.2 | 9.1 |

| Followed around in stores* | 7.0 | 5.8 | 0.0 |

| Mean (Standard Deviation) | 3.33(5.44) | 4.60(5.68) | .96(2.60) |

Note.

All statements qualified by, “because of your race.”

Table 4 presents regression results for the effects of racial discrimination on self-esteem. In the first model, age, female gender, and SES were all statistically significant and positively related to an increased sense of self-esteem. The second model included racial discrimination as a social stressor. Subjective experiences of racial discrimination were significantly and negatively related with self-esteem; for every one-unit increase in encounters with racial discrimination, self-esteem decreased by .13 points. The R2 change indicated that the inclusion of this variable significantly improved the model fit (p<.05). All of the significant demographic variables in the first model retained significance in this model. The third model included ethnic identity and the previous variables from model's one and two. A strong sense of ethnic identity was significantly and positively related to self-esteem. The inclusion of this variable also significantly contributed to the model (R2 change p <.01). In this model, all of the significant variables retained their significance with ethnic identity exhibiting the strongest effects on self-esteem followed by SES, age, and racial discrimination. The demographic variables, perceived racial discrimination, and ethnic identity explained 38 per cent of the variance in self-esteem. The final model tested the hypothesized moderating effect of ethnic identity on the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem. In this model, all of the independent variables retained significance. The interaction term of racial discrimination x ethnic identity failed to reach significance suggesting that ethnic identity may not moderate the relationship between perceived racial discrimination and self-esteem.

Table 4.

Regression Estimates of the Relationship between Racial Discrimination and Self-Esteem among Children (N = 175)

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b(s.e.) | β | b(s.e.) | β | b(s.e.) | β | b(s.e.) | β | |

| Age | 1.04(.19)** | 0.373 | 0.98(.19)** | 0.35 | 0.88(.18)** | 0.31 | 0.90(.18)** | 0.32 |

| Gendera | 1.93(59)** | 0.224 | 1.86(.59)** | 0.22 | 1.73(.54)** | 0.20 | 1.68(.55)** | 0.19 |

| SES | 0.08(.02)** | 0.283 | 0.07(.02)** | 0.24 | 0.10(.02)** | 0.33 | 0.10(.02)*** | 0.33 |

| Racial Discrimination | -0.13(.06)* | -0.14 | -0.11(.06)* | -0.13 | -0.12(.06)* | -0.14 | ||

| Ethnic Identity | 0.32(.06)** | 0.36 | 0.33(.06)*** | 0.36 | ||||

| Interaction termb | -.01(01) | |||||||

| R2 | 0.25 | .26 | .38 | .40 | ||||

Female as referent category

Interaction term racial discrimination × ethnic identity

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

DISCUSSION

This research examined whether marginalized groups had an awareness of race, reported children's experiences with racial discrimination, and assessed the moderating effect of ethnic identity on the relationship between racial discrimination and self-esteem. Overall, non-Hispanic black children were more aware of the concept of race. This finding supports the racial socialization literature and the work conducted by Nazroo (2003) in the United Kingdom that marginalized groups (non-Hispanic blacks) with histories of oppression are more aware of race. Children also reported frequent encounters with racial discrimination over a thirty-day period. The findings also support the racism-related-stress model that racial discrimination negatively affects self-esteem. However, the findings do not support the moderating effects of ethnic identity.

Although Hispanic children reported significant exposure to racial discrimination, their awareness of the definition of race was almost identical to that of non-Hispanic white children and below that of non-Hispanic black children. These findings are supported by the works of Levine and Ruiz (1978) and Ocampo and colleagues (1993) which suggest that Mexican American children develop racial identification at later ages. The Hispanic children in the current study are largely generation 1.5 immigrants (those who have recently migrated from Latin American countries before the age of 12, ~ 86 per cent) and are overwhelmingly of Mexican origin (~ 80 per cent). As Viruell-Fuentes (2007) notes, this generation of Hispanic children learns about their lower racial/ethnic status through interactions with others.

The early social contexts of the Hispanic participants in this study are overwhelmingly in Latin America. The traditional perceptions of racism in the United States, with an emphasis on a black-white racial binary, do not fit the Hispanic immigrant experience as Hispanics may be black, white, Amerindian, or some combination thereof. When Hispanic children immigrate to the United States and have contacts with children of other races and ethnicities, in their schools or neighborhoods, they are more likely to become aware of their marginalized status (Viruell-Fuentes 2007). Hispanics, particularly immigrant children, may therefore be more similar to non-Hispanic whites when considering race as a master status than they are to non-Hispanic blacks.

Although they have lower awareness of race, a greater percentage of Hispanic children report discriminatory encounters. This suggests that the embodiment of Hispanic ethnicity is not without challenges in the United States. Taken together, these data suggest that as their population and visibility continue to increase, Hispanics may become targets of discrimination at younger ages. The higher rates of discriminatory experiences directed at Hispanic children may also include forms of discrimination separate from those experienced by other racial/ethnic groups. For example, it is possible that if the Williams Every-Day-Discrimination Scale included discrimination based on language, discriminatory experiences reported by Hispanics would be even greater.

Non-Hispanic white children in this study are less able to define the term race and very few non-Hispanic white children report racial discrimination. The racial socialization literature suggests that only a segment of the population engages in this process. As other studies note, racial socialization is salient for individuals with historic experiences of discrimination (Brown and Krishnakumar 2007). Therefore, it is not surprising that many non-Hispanic white children required racial definitions. As Copenhaver-Johnson (2006) demonstrates, white parents are more reluctant to discuss race, discrimination, and racism, which can possibly contribute to the inability of the non-Hispanic white children in this study to define race. The largest percentage of discriminatory experiences for non-Hispanic whites was being bothered or threatened because of their race.

Additionally, racial discrimination negatively affected self-esteem across racial/ethnic groups. It appears that encounters with discrimination are important for children and that the negative health affects associated with racial discrimination are present in this group of young children. This further supports the work linking racial discrimination to health status for adolescents and adults. As well, these results highlight the need for more studies to decompose the effects of racial discrimination on the physical and mental health of young children.

While Hispanic children in Birmingham reported higher rates of discrimination than their non-Hispanic black counterparts, these results may not apply to all locales. The non-Hispanic black children in this study are predominantly concentrated in urban areas with high concentrations of blacks. Such ethnic enclaves can function as protective zones (Wilson and Martin 1982) where children may be less likely to have exposure to racism (Massey and Denton 1992). Further, to examine the levels of segregation across groups, isolation and interaction indices were calculated (McKibben and Faust 2004). These calculations indicate that, indeed non-Hispanic black and Hispanic/non-Hispanic white children are highly segregated by residence (numbers not calculated separately for Hispanics due to small sample sizes). The likelihoods of meeting another member of their racial/ethnic group are 64 and 87 per cent for non-Hispanic black and Hispanic/non-Hispanic whites respectively. Furthermore, non-Hispanic blacks have a 35 per cent chance of interacting with people of other racial/ethnic groups whereas the Hispanic/non-Hispanic white children have only an 11 per cent chance. These indices convey that non-Hispanic white children have a low degree of interacting with children of other racial/ethnic groups and further underscore their lack of racial awareness.

Although we evaluated racial discrimination on an individual level, the racialized social systems that help to create these interactions are important. As Bonilla-Silva notes (1997, 1999), racialized social systems become institutionalized and form a culture whereby the social relationships and life chances within and between racial groups are structured. The reported instances of racial discrimination and the resultant effects on the self-esteem of young children in this study emerge from these embedded social structures. The children in this study utilize these structures to maintain dominance, status, and privilege (Van Ausdale and Feagin 2001).

While very informative, there are some limitations to this research. One African American interviewer conducted all interviews and research shows there may be respondent bias due to the racial-gender discordance between the interviewer and respondents. Research also indicates that individuals are likely to underreport instances of discrimination resulting from the possible stresses of recalling the incidents, the sensitive nature of the topic, or the denial of personal experiences for self-preservation (Karlsen and Nazroo 2002). In addition, the methods used for racial socialization are not included in this study. This study sample consists of healthy children recruited and paid to participate in a clinical study. Nevertheless, the current findings expand the literature and provide important clues for guiding future research on race and discrimination among children. This study suggests that racial heterogeneity among children is not necessarily indicative of racial harmony. This calls attention to the need for parents, schools, and communities to be attentive to solving such problems, especially with the current growth in the Hispanic population. Research on racial discrimination during childhood has primarily focused on the experiences of non-Hispanic black children. However, this research suggests that the experiences of young Hispanic children need to be included in future work and measures of discrimination associated with accent, immigrant status, and language proficiency, as well as skin color be utilized. In addition, future studies should engage in research to understand how young Hispanic children identify and interpret race and ethnicity.

Acknowledgments

Funded by NIH grant R01DK067426. The authors wish to acknowledge the AMERICO team, Alexandra Luzuriaga-McPherson, Amanda Willig, Krista Casazza, and Michelle Cardel for their assistance with the data collection phase of the project. The author's field of study is Medical Sociology.

Biographies

AKILAH DULIN KEITA is a Postdoctoral Scholar in the Department of Nutrition Sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

ADDRESS: Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, WEBB 415, 1530 3rd Ave S., Birmingham, AL 35294. akilah@uab.edu

LONNIE HANNON III is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Sociology at Tuskegee University.

ADDRESS: Department of Sociology, Tuskegee University, Bioethics Center Room 44-315, Tuskegee, AL 36088. lhannon@tuskegee.edu

JOSE R. FERNANDEZ is an Associate Professor in the Department of Nutrition Sciences at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

ADDRESS: Department of Nutrition Sciences, University of Alabama at Birmingham, WEBB 449A, 1530 3rd Ave S., Birmingham, AL 35294. jose@uab.edu

WILLIAM C. COCKERHAM is a Distinguished Professor in the Department of Sociology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

ADDRESS: Department of Sociology, University of Alabama at Birmingham, HHB 460., Birmingham, AL 35294. wcocker@uab.edu

Reference List

- ARAUJO BY, BORRELL LN. Understanding the link between discrimination, mental health outcomes, and life chances among Latinos. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2006;28(2):245–266. [Google Scholar]

- BARRY DT, GRILO CM. Cultural, self-esteem, and demographic correlates of perception of personal and group discrimination among East Asian immigrants. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2003;73:223–229. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.73.2.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BELL MCDONALD K, HARVEY WINGFIELD AM. (In)Visibility blues: The paradox of institutional racism. Sociological Spectrum. 2009;29(1):28–50. [Google Scholar]

- BONILLA-SILVA E. Rethinking racism: Toward a structural interpretation. American Sociological Review. 1997;62(3):465–480. [Google Scholar]

- BONILLA-SILVA E. The essential social fact of race. American Sociological Review. 1999;64(6):899–906. [Google Scholar]

- Boocock SS, Scott KA. Kids in Context: The Sociological Study of Children and Childhoods. Rowman and Littlefield; Lanham, Maryland: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- BRODY GH, CHEN YF, MURRY VM, GE XJ, SIMONS RL, GIBBONS FX, GERRARD M, CUTRONA CE. Perceived discrimination and the adjustment of African American youths: A five-year longitudinal analysis with contextual moderation effects. Child Development. 2006;77(5):1170–1189. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- BROWN TL, KRISHNAKUMAR A. Development and validation of the adolescent racial and ethnic socialization scale (ARESS) in African American families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2007;36(8):1072–1085. [Google Scholar]

- BUTLER RJ, GASSON SL. Self Esteem/Self Concept Scales for Children and Adolescents: A Review. Child and Adolescent Mental Health. 2005;10:190–201. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-3588.2005.00368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CLARK R, COLEMAN AP, NOVAK JD. Initial psychometric properties of the everyday discrimination scale in black adolescents. Journal of Adolescence. 2004;273:363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly P. Racism, Gender Identities and Young Children: Social Relations in a Multi-Ethnic, Inner-City Primary School. Routledge, London: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- COPENHAVER-JOHNSON J. Talking to children about Race: The Importance of Inviting Difficult Conversations. Childhood Education. 2006;83:12–22. [Google Scholar]

- FEAGIN JR, SIKES MP. Living with racism: The black middle class experience. Beacon Press; Boston, MA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- FERGUSON A. Bad Boys: Public Shools in the Making of Black Masculinity. University of Michigan Press; Ann Arbor, MI: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- FISHBEIN HD. Peer Prejudice and Discrimination: The Origins of Prejudice. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- FISHER CB, WALLACE SA, FENTON RE. Discrimination distress during adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2000;29:679–695. [Google Scholar]

- FLORES JC. Nueva York - Diaspora City: U.S. Latinos Between and Beyond. NACLA Report on the Americas. 2002;35:46–49. [Google Scholar]

- HARRELL SP. A multidimensional conceptualization of racism-related stress: Implications for the well-being of people of color. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(1):42–57. doi: 10.1037/h0087722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HARRIS-BRITT A, VALRIE CR, KURTZ-COSTES B. Perceived Racial Discrimination and Self-Esteem in African American Youth: Racial Socialization as a Protective Factor. Journal of Research on Adolescence. 2007;17:669–682. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-7795.2007.00540.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HOLLINGSHEAD AB. Four Factor Index of Social Status. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- HOMES KJ, LOCHMAN JE. Ethnic identity in African American and European American preadolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence. 2009;29:476–496. [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES D. Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2003;31(1-2):15–33. doi: 10.1023/a:1023066418688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- HUGHES D, JOHNSON D. Correlates in children's experiences of parents’ racial socialization behaviors. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2001;63(4):981–995. [Google Scholar]

- JOHNSON J, RUSH SFJ. Reducing Inequalities: Doing Anti-Racism: Toward an Egalitarian American Society. Contemporary Sociology. 2000;29:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- KARLSEN S, NAZROO JY. Relation between racial discrimination, social class, and health among ethnic minority groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(4):624–631. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.4.624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEVINE E, RUIZ R. An exploration of multi-correlates of ethnic group choice. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology. 1978;9:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- LEWIS A. Race in the Schoolyard: Negotiating the color Line in Classrooms and Communities. Rutgers University Press; New Brunswick, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- LORENZO-HERNANDEZ J, OULLETTE S. Ethnic identity, self-esteem, and values in Dominicans, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans. American Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1998;28:2007–2024. [Google Scholar]

- MASSEY DS, DENTON NA. Residential Segregation of Asian-Origin Groups in United-States Metropolitan-Areas. Sociology and Social Research. 1992;76(4):170–177. [Google Scholar]

- MCKIBBEN JN, FAUST KA. Population Distribution-Classification of Residence. In: SIEGEL JS, SWANSON DA, editors. The Methods and Materials of Demography. Elsevier Academic Press; San Diego CA: 2004. pp. 105–124. [Google Scholar]

- MCREARY M, SLAVIN L, BERRY EJ. Predicting problem behavior and self-esteem among African American adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1996;11:216–234. [Google Scholar]

- MOSSAKOWSKI KN. Coping with perceived discrimination: does ethnic identity protect mental health? Journal of Health and Social .Behavior. 2003;44(3):318–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MYERS LJ, STOKES D, SPEIGHT S. Physiological responses to anxiety and stress: reactions to oppression, galvinc skin potential, and heart rate. Journal of Black American Studies. 1989;20:80–96. [Google Scholar]

- NAZROO JY. The structuring of ethnic inequalities in health: economic position, racial discrimination, and racism. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):277–284. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NYBORG VM, CURRY JF. The impact of perceived racism: Psychological symptoms among African American boys. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32(2):258–266. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3202_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OCAMPO K, BERNAL MKP. Gender, race, and ethnicity: The sequencing of social constancies. In: BERNAL M, KNIGHT G, editors. Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. State University of New York Press; Albany: 1993. pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- PHINNEY JS. The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1992;2:156–176. [Google Scholar]

- PORTER JE, WASHINGTON RE. Minority identity and self-esteem. Annual Reviews in Sociology. 1993;19:139–161. [Google Scholar]

- PRESSER S, BLAIR J. Survey Pretesting - Do Different Methods Produce Different Results? Sociological Methodology. 1994;24:73–104. [Google Scholar]

- ROBERTS RE, PHINNEY JS, MASSE LC, CHEN RY, ROBERTS CR, ROMERO AJ. The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. Journal of Early Adolescence. 1999;19:301–322. [Google Scholar]

- ROMERO AJ, ROBERTS RE. The impact of multiple dimensions of ethnic identity on discrimination and adolescents’ self-esteem. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 2003;33:2288–2305. [Google Scholar]

- Rosneberg M. Society and the Adolescent. Princeton University Press; Princeton, NJ: 1965. [Google Scholar]

- SPENCER MB, MARKSTROM-ADAMS C. Identity processes among racial and ethnic minority children in America. Child Development. 1990;61:290–310. [Google Scholar]

- SZALACHA LA, ERKUT S, GARCIA CC, ALARCON O, FIELDS JP, CEDER I. Discrimination and Puerto Rican children's and adolescents’ mental health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9(2):141–155. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THORNTON MC, CHATTERS LM, TAYLOR RJ, ALLEN WR. Sociodemographic and Environmental Correlates of Racial Socialization by Black Parents. Child Development. 1990;61(2):401–409. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1990.tb02786.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ausdale D, Feagin JR. The First R: How Children Learn Race and Racism. Rowman and Littlefield; Lanham, MD: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- VIRUELL-FUENTES EA. Beyond acculturation: Immigration, discrimination, and health research among Mexicans in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 2007;65(7):1524–1535. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WARDLE J, WILLIAMSON S, JOHNSON F, EDWARDS C. Depression in adolescent obesity: cultural moderators of the association between obesity and depressive symptoms. Inernational Journal of Obesity. 2006;30(4):634–643. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHITBECK LB, MCMORRIS BJ, HOYT DR, STUBBEN JD, LAFROMBOISE T. Perceived discrimination, traditional practices, and depressive symptoms among American Indians in the upper Midwest. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2002;43(4):400–418. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS DR, COLLINS C. Us Socioeconomic and Racial-Differences in Health - Patterns and Explanations. Annual Review of Sociology. 1995;21:349–386. [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS DR, NEIGHBORS HW, JACKSON JS. Racial/ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–208. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.2.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS DR, WILLIAMS-MORRIS R. Racism and mental health: the African American experience. Ethnicity and .Health. 2000;5(3-4):243–268. doi: 10.1080/713667453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS DR, YAN YU, JACKSON JS, ANDERSON NB. Racial Differences in Physical and Mental Health: Socioeconomic Status, Stress and Discrimination. Journal of Health Psychology. 1997;2:335–351. doi: 10.1177/135910539700200305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS JE, BOSWELL DA, BEST DL. Evaluative Responses of Preschool Children to the Colors White and Black. Child Development. 1975;46:501–508. [Google Scholar]

- WILLIAMS JE, ROBERSON KJ. A Method for Assessing Racial Attitudes in Preschool Children. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1967;27:671–689. [Google Scholar]

- WILSON KE, MARTIN WA. Ethnic Enclaves: A Comparison of Cuban and Black Economies in Miami. American Journal of Sociology. 1982;88:135–160. [Google Scholar]

- WILSON WJ. When Work Disappears: The world of the new urban poor. Alfred A Knopf: distributed by Random House; New York, NY: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- WILSON WJ. The Truly Disadvantaged. University of Chicago; Chicago IL: 1987. [Google Scholar]