Summary

Most current crystallographic structure refinements augment the diffraction data with a priori information consisting of bond, angle, dihedral, planarity restraints and atomic repulsion based on the Pauli exclusion principle. Yet, electrostatics and van der Waals attraction are physical forces that provide additional a priori information. Here we assess the inclusion of electrostatics for the force field used for all-atom (including hydrogen) joint neutron/X-ray refinement. Two DNA and a protein crystal structure were refined against joint neutron/X-ray diffraction data sets using force fields without electrostatics or with electrostatics. Hydrogen bond orientation/geometry favors the inclusion of electrostatics. Refinement of Z-DNA with electrostatics leads to a hypothesis for the entropic stabilization of Z-DNA that may partly explain the thermodynamics of converting the B form of DNA to its Z form. Thus, inclusion of electrostatics assists joint neutron/X-ray refinements, especially for placing and orienting hydrogen atoms.

Introduction

The initial implementation of crystallographic refinement by simulated annealing (Brünger et al., 1987) used an early version of the CHARMM20 force field (Brooks et al., 1983) that included electrostatics. The benefits of including electrostatics with respect to hydrogen bonding in crystallographic refinement were noted in the refinement of influenza virus hemagglutinin (Weis et al., 1990), although incorrect hydrogen bonds were observed when electrostatics were used during the simulated annealing stages, especially for charged groups such as the headgroups of arginine residues. As a compromise, electrostatics was only used during the minimization stages, which resulted in favorable electrostatic interactions while preventing formation of incorrect hydrogen bonds. A likely explanation for the formation of incorrect hydrogen bonds during simulated annealing is that continuum solvent electrostatics are not included in the CHARMM20 force field to dampen the strength of interactions between solvent exposed residues (e.g. Poisson-Boltzmann or Generalized Kirkwood) (Schnieders et al., 2007; Schnieders and Ponder, 2007). Furthermore, the CHARMM20 force field also lacks polarization (Ponder and Case, 2003) and it uses a spherical cutoff rather than Ewald lattice summation (Sagui and Darden, 1999; Karttunen et al., 2008). For simplicity, it has therefore become the practice in most refinement programs to exclude electrostatics during all refinement stages and assume the diffraction data is capable of supplying this excluded a priori information (Adams et al., 1997). More recently, there have been attempts to re-introduce electrostatics in the refinement of NMR structures (Linge et al., 2003) and crystal structures (Moulinier et al., 2003; Korostelev et al., 2004; Schnieders et al., 2009; Fenn et al., 2010). Furthermore, force fields, lattice summation and continuum electrostatics have matured and computing power increased considerably over the last twenty years. It is therefore important to re-examine the question of the general use of electrostatics in routine crystallographic refinements, especially with respect to the increasing use of neutron diffraction and joint neutron/X-ray diffraction studies where hydrogen bonding is a motivation and electrostatics is expected to have a significant effect. We have therefore focused here on the effect of including electrostatics in the force field on joint neutron/X-ray diffraction crystal structure refinements.

The elastic interaction of X-rays with electrons gives rise to the coherent scattering phenomenon used in macromolecular crystallography experiments. The scattering power of a given atom type correlates with the number of electrons it possesses, and thus increases proportionally with atomic number. This puts light atoms at a disadvantage, especially in the case of hydrogen relative to the common atom types of organic biomolecules. Combined with the low signal to noise ratio of macromolecular diffraction, hydrogen atoms are commonly left out of the modeling process or, when possible, placed using simple geometric criteria. Therefore, accurately determining the locations of hydrogen atoms is difficult to achieve using X-ray crystallography data alone, although their locations form a core component in evaluating the function, stability and ligand binding of biomolecules.

As neutrons carry no formal charge, neutron scattering originates solely from nuclear interactions - while less stringently characterized due to resonance effects, scattering is more uniform between elements (Bacon and Lonsdale, 1953). Pioneering work by Shull and Wollan indicated hydrogen and deuterium strongly scatter neutrons, although incoherent scattering of neutrons by hydrogen gives rise to significantly greater background scattering (Davidson et al., 1947) - thus most macromolecular samples are exchanged into or prepared in D2O. As such, neutron diffraction is a useful complement to X-ray diffraction for determining the location of hydrogen atoms (Blakeley et al., 2008).

Electrostatic forces are particularly important for atoms that have several degrees of freedom after application of geometric chemical restraints, such as hydrogen atoms involved in hydroxyl groups and solvent molecules. In the case of water molecules modeled as D2O, even when relatively high resolution X-ray and neutron data are available, interpretation of scattering density in terms of oriented or partially oriented water molecules can be difficult, laborious, and subjective (Chatake et al., 2003). Until recently, computation of the electrostatic energy typically involved a conditionally convergent lattice summation based on spherical cutoffs, which is problematic for systems with long range correlations such as crystals (York et al., 1993), large proteins in water (Schreiber and Steinhauser, 1992), nucleic acids (York et al., 1995) and hydrogen bonding geometry (Morozov et al., 2004). A rigorous and efficient solution termed the particle mesh Ewald (PME) summation was devised, which employs the classical Ewald method (Ewald, 1921) of dividing the problem into rapidly converging real and reciprocal space sums and applies fast Fourier transforms (FFTs) to the latter portion of the summation method (Darden et al., 1993; Sagui et al., 1999). We have recently developed a refinement method for sub-atomic resolution crystal structures (Schnieders et al., 2009; Fenn et al., 2010) that includes a PME approach to rigorously calculate the electrostatic energy and forces, thereby avoiding the problems associated with spherical cutoffs. Further, this method replaces the simple geometric force field that is customarily used in macromolecular refinement (Engh and Huber, 1991) with the polarizable Atomic Multipole Optimized Energetics for Biomolecular Applications (AMOEBA) force field (Ren and Ponder, 2003, 2004; Ponder et al., 2010), which includes a water model that matches experimental observations in varied environments (Ren et al., 2004; Schnieders et al., 2007; Schnieders et al., 2007). We have previously used this approach to refine several sub-atomic resolution small molecule (Schnieders et al., 2009) and protein (Fenn et al., 2010) X-ray structures, which yielded improved statistical agreement with the diffraction data and more chemically informative models.

In this work we study the effect of including electrostatics using the OPLS-AA nonbonded parameters with a spherical cutoff (Jorgensen and Tirado-Rives, 1988) in conjunction with target and energy values for bond, angle and dihedral potentials adapted for structure determination (Engh et al., 1991; Parkinson et al., 1996; Linge et al., 2003; Nozinovic et al., 2010) (as implemented in CNS v1.3, simply referred to as the OPLS-AA-X force field), and using the AMOEBA force field with PME on joint neutron/X-ray structures of a B-DNA oligomer, a Z-DNA oligomer, and the protein xylose isomerase. For comparison we also tested an all-hydrogen force field without electrostatics (obtained by using the OPLS-AA-X force field as defined above, but with the nonbonded interactions replaced with a simple repulsive term, referred to as the “Repel” force field) (Adams et al., 1997). We find that both the OPLS-AA-X and AMOEBA force fields produce hydrogen-bonding patterns that are more consistent with theoretical models and chemical expectation than the Repel force field. AMOEBA provides a further improvement with the nuclear density maps and more extensive hydrogen bonding networks. In particular, refinement of B-DNA with electrostatics results in a revised hydrogen bonding arrangement that is in better agreement with experiment and the classical Dickerson theory of minor groove hydration. Refinement of Z-DNA with electrostatics, which is based on updated and improved X-ray and neutron diffraction data, produces unexpected results that challenge currently held views on the role of hydration spines in stabilizing DNA duplexes.

Results

B-DNA

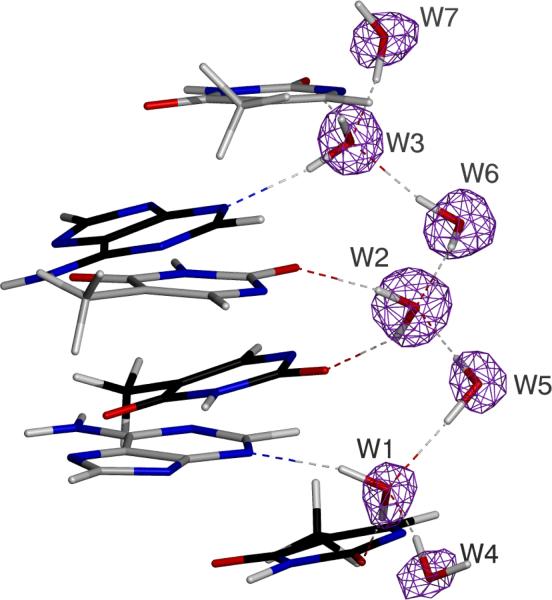

Early X-ray work by Dickerson on DNA described and refined a proposal of hydration in the minor groove of DNA referred to as the zig-zag spine (Wing et al., 1980; Drew and Dickerson, 1981). The hydration pattern is defined as a water molecule bridging a base with the base following on the opposing strand in the 5'→3' direction (e.g. see water W2 in Figure 1). The water molecules that form these bridges are joined by a second hydration shell, creating a zig-zag pattern (Figure 1). 1H NMR NOESY and ROESY spectra confirm this configuration via the presence of strong, long lived (>1 ns) NOE signals arising from adenine H2 protons in close proximity to water protons in the primary spine (Kubinec and Wemmer, 1992; Liepinsh et al., 1992; Fawthrop et al., 1993). Other experiments have independently observed the zig-zag spine or long lived water molecules in a zig-zag pattern, including molecular dynamics (Chuprina et al., 1991; Chen et al., 2008; Young, Ravishanker, et al., 1997; Young, Jayaram, et al., 1997) and atomic resolution crystallography studies (Chiu et al., 1999; Minasov et al., 1999; Valls et al., 2004; Woods et al., 2004), and the spine is a critical part of DNA stability (Lan and McLaughlin, 2000). Further, re-refinement of a crystal structure of a B-DNA 9-mer dGCGAATTCG (Soler-Lopez et al., 2000) (PDB ID 1ENN) using high-resolution X-ray data complemented by the AMOEBA force field produced all the features of the zig-zag spine (Fenn et al., 2010). However, a recent 2.5 Å resolution neutron structure on a different DNA sequence (dCCATTAATGG) (PDB ID 1WQZ) suggests the hydration spine is formed by four layers of water that form weak hydrogen bonds (Arai et al., 2005), although the weak classification is typically reserved for rare types of hydrogen bonds (e.g. O-H-π) that are not observed in the zig-zag spine (Desiraju and Steiner, 2001).

Figure 1.

Hydration structure in B-DNA. Zig-zag spine in the minor groove of B-DNA (dGCGAATTCG) as determined from re-refinement with the 0.89 Å X-ray diffraction data set (PDB ID 1ENN) using the AMOEBA force field and PME electrostatics (Fenn et al., 2010).

Starting from this deposited neutron structure, the deposited neutron diffraction data, and its corresponding X-ray data (PDB ID 1WQY), we re-refined the dCCATTAATGG B-DNA structure jointly against both the X-ray and neutron diffraction data using the Repel, OPLS-AA-X force field with electrostatics using a spherical cutoff based implementation of computing electrostatics, and the AMOEBA force field with PME. In all cases we used an updated version of the joint neutron/X-ray refinement version of CNS v1.3 (referred to as nCNS), and all hydrogen atoms were included in the refinements.

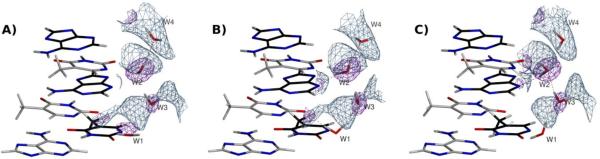

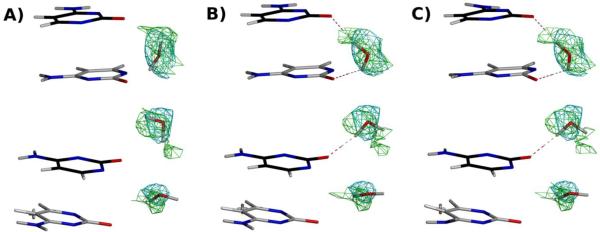

The results near the zig-zag spine are presented in Figures 2A–C, and the overall statistics are presented in Table 1. Joint neutron/X-ray refinement with the Repel force field (Figure 2A) does not produce any of the features of the zig-zag spine and only forms one hydrogen bond (shown as dashed lines in all Figures) in the region shown, suggesting that the particular neutron and X-ray diffraction data do not provide enough information to uniquely determine the hydrogen bonding pattern. In contrast, joint neutron/X-ray refinement with the OPLS-AA-X force field (Figure 2B) improves the hydrogen bonding, as one of the primary spine hydrogen bonds is reproduced on water molecules W1 and W2. Joint neutron/X-ray refinement using the AMOEBA force field further improves the agreement with the zig-zag spine model: water W2 (Figure 2C), for example, rotates to function as a hydrogen bond donor to the O2 and N3 atoms of the thymine and adenosine, respectively, as evidenced by NMR experiments (Kubinec et al., 1992; Liepinsh et al., 1992; Fawthrop et al., 1993). Likewise, water molecules W3 and W4 form secondary spine interactions that yield part of the classical zig-zag pattern. Water W1 fails to orient correctly. Furthermore, both the neutron and X-ray based Rfree values are decreased by 2.3 and 0.7%, respectively compared to refinement with the OPLS-AA-X force field, albeit at the expense of larger deviations from ideal bonds and angle values for the AMOEBA refinements. These differences may be related to differences in the relative weighting of the various energy terms rather than differences in the hydrogen bonding network, as we did not perform Rfree-based optimizations of the weights (wA and wB, Eqn. 1). The 2Fo-Fc nuclear density maps are of rather poor quality (light blue mesh in Figure 2A–C); this poor quality is likely due to the low resolution (2.5 Å) and low completeness (59%) of the neutron diffraction data. Thus, the positions of the oxygen atoms of the water molecules are largely determined by the X-ray data, whereas the orientation of the water molecules, and therefore the arrangements of the hydrogen bonds, is largely determined by the force field used in the joint neutron/X-ray refinement.

Figure 2.

(A) Minor groove of DNA resulting from the 2.5 Å refinement with neutron data (PDB ID 1WQZ, sequence dCCATTAATGG) and corresponding 1.6 Å X-ray data (PDB ID 1WQY) using the Repel force field (i.e. without the inclusion of electrostatics). (B) as in (A), but with electrostatics computed using the OPLS-AA-X force field (using a real space spherical cutoff of 8.5 Å). (C) as in (A) but using the AMOEBA force field. In all figures, the purple mesh represents X-ray σA weighted 2Fo−Fc electron density contoured at 2.0 σ and light blue mesh represents σA weighted 2Fo−Fc nuclear density contoured at 1.5 σ. Density is contoured around the water molecules only for the sake of clarity. Nucleotide bases in white are from the 5'→3' strand, and those in black correspond to the partner 3'→5' strand. Figures were generated with POVScript+ (Fenn et al., 2003) and rendered using POVRay.

Table 1.

Joint neutron/X-ray refinement statistics.

| Structur e | PDB ID (N/X1) | dlim (N/X, Å) | Force Field | rmsd bonds2 | rmsd angles2 | R/Rfree (N)3 | R/Rfree (X) | HB ratio4 | Ow-Ow (d, Å)5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B-DNA | 1WQZ/1WQY | 2.5/1.6 | Repel | 0.003 (0.001) | 0.60 (0.05) | 32.47/35.32 | 31.90/37.21 | 0.07 | 2.98 ± 0.08 |

| OPLS-AA-X | 0.004 (0.008) | 0.63 (0.46) | 33.15/37.39 | 32.04/37.00 | 0.5 | 2.86 ± 0.25 | |||

| AMOEBA | 0.012 (0.007) | 2.64 (2.33) | 32.55/35.05 | 31.64/36.24 | 0.56 | 2.90 ± 0.20 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Z-DNA | 3QBB/3QBA | 1.4/1.5 | Repel | 0.006 (0.002) | 0.76 (0.12) | 31.45/32.21 | 21.89/23.14 | 0.18 | 2.94 ± 0.18 |

| OPLS-AA-X | 0.007 (0.008) | 0.83 (0.38) | 31.60/33.28 | 21.81/23.49 | 0.44 | 2.90 ± 0.18 | |||

| AMOEBA | 0.011 (0.008) | 2.81 (2.51) | 30.51/31.95 | 21.05/24.46 | 0.55 | 2.92 ± 0.16 | |||

|

| |||||||||

| Xylose isomeras e | 3KCL/3KBM | 2.0/2.0 | Repel | 0.005 (0.001) | 0.76 (0.13) | 23.69/26.08 | 14.93/17.95 | 0.37 | 2.90 ± 0.14 |

| OPLS-AA-X | 0.006 (0.008) | 0.79 (0.40) | 23.87/25.57 | 14.99/17.81 | 0.68 | 2.87 ± 0.16 | |||

N refers to model statistics with respect to the neutron diffraction data, X refers to model statistics with respect to the X-ray diffraction data.

Root mean square deviations from ideal bond lengths and bond angles are given for all atoms and for water molecules alone (in parentheses).

R=Σ||Fobs|−|Fcalc||/Σ|Fobs| 10% of reflections in the B-DNA case and 5% of reflections in the Z-DNA and xylose isomerase data sets were set aside for computation of Rfree.

Criteria used for hydrogen bonds: hydrogen to water oxygen distance at most 2.5 Å, and Ow-Hw-A angle of 180 ± 40°. Includes bonds to symmetry mates, and only water-water hydrogen bonds are considered.

Expected Ow-Ow distance based on condensed phase small angle neutron/X-ray diffraction value is 2.80 ± 0.04 Å (Soper, 2007).

Z-DNA

The patterns of hydration in Z-DNA have been characterized by a number of crystallization studies, but have received relatively little attention by computer simulation and nuclear magnetic resonance studies. As a result, the hydrogen bonding characteristics of this form of DNA have not been experimentally verified. We therefore applied joint neutron/X-ray refinement to high-resolution neutron and X-ray diffraction data of Z-DNA crystals (dCGCGCG) (Langan et al., 2006). Importantly, we were able to obtain the Z-DNA crystals without the use of duplex stabilizing polyamines which can potentially disrupt or stabilize hydration networks, or alternatively facilitate interconversion between DNA structural forms (Hou et al., 2001). We collected a 90% complete neutron data set to 1.4 Å (Table 2), yielding a data to parameter ratio of approximately 2.3 (including hydrogen and deuterium atoms and assuming four independent parameters per atom) and corresponding X-ray diffraction data collected on the same crystal (to 1.5 Å resolution). The overall results of the joint neutron/X-ray refinements are presented in Table 1. In the following, we have restricted our structural references to those of unmodified and identical nucleotide sequence to that studied here (dCGCGCG) for the sake of brevity, although similar conclusions have been reached with other Z-DNA sequences (see, for example, Gessner et al. and references therein (Gessner et al., 1994)).

Table 2.

Neutron data collection statistics. See also Table S1.

| Neutron data | |

|---|---|

| Diffraction protocol | TOF neutron Laue |

| λ (Å) | 0.6 – 0.7 |

| Temperature (K) | 293 |

| Resolution range (Å) | 25.6 - 1.4 (1.45 - 1.4) |

| Unique reflections | 4680 (407) |

| Completeness | 90.1 (78.8) |

| Redundancy | 5.5 (3.2) |

| <I/σ(I)> | 5.6 (3.8) |

| Rmerge (%) | 23 (49) |

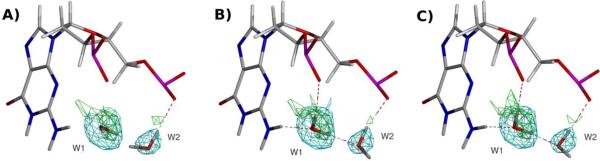

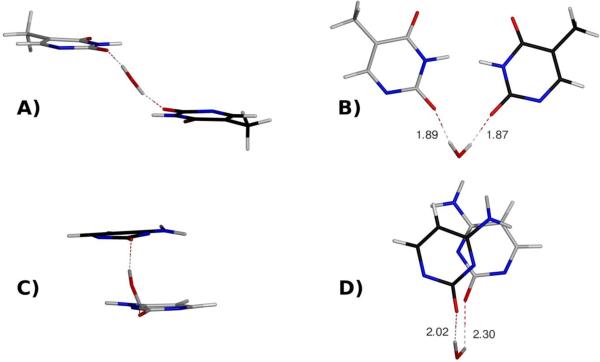

A common observation in Z-DNA structure is the hydration of the phosphate group with the preceding (i.e. in the 5' direction) guanosine N2 amino group (Wang et al., 1984; Gessner et al., 1994; Chatake et al., 2005). Such a configuration is associated with lower interaction energies with phosphate groups as compared with water self-interactions in molecular mechanics studies (Swamy and Clement, 1987), and with long-lived hydrogen bonds in molecular dynamics trajectories (Laaksonen et al., 1989; Eriksson and Laaksonen, 1992). An example of phosphate group solvation resulting from the joint neutron/X-ray refinements is shown in Figure 3. As with the B-DNA results, refinement with the Repel force field (Figure 3A) results in little to no hydrogen bonding of the water molecules with the surrounding environment. The refinement based on the OPLS-AA-X force field (Figure 3B) orients the water molecules to form a network from the guanosine N2 with the following phosphate, as predicted. The AMOEBA-based results agree with the OPLS-AA-X based refinement in this instance (Figure 3C). Also note that the nuclear density agrees with the electrostatics-based results at water molecule W1, although it is weakly defined around water molecule W2 (green mesh in Figure 3). Thus, the introduction of electrostatics with the OPLS-AA-X and AMOEBA force fields are primarily responsible for orienting the deuterium atoms in the latter case.

Figure 3.

Guanosine N2-phosphate hydration in Z-DNA. (A) Hydration pattern resulting from the joint refinement with the 1.4 Å neutron diffraction data (PDB ID X, sequence dCGCGCG) and with the corresponding X-ray diffraction data to 1.5 Å (PDB ID Y) using the Repel force field (i.e. without the inclusion of electrostatics). (B) As in (A), but with electrostatics computed using the OPLS-AAX force field (using a real space electrostatic cutoff of 8.5 Å). (C) Results from refinement using the AMOEBA force field (using a PME-based electrostatic implementation). In all figures, the cyan mesh represents X-ray σA weighted Fo−Fc electron density contoured at 2 σ and green mesh represents σA weighted Fo−Fc nuclear density contoured at 1.5 σ prior to the inclusion of these particular water molecules in the model phase calculations. Density is contoured around the water molecules only for the sake of clarity. See also Figure S1.

A second notable motif in Z-DNA hydration is the two-water bridge that forms between N4 amino groups on opposite strands of neighboring cytosine residues (Eriksson et al., 1992; Gessner et al., 1994; Chatake et al., 2005). This interaction is shown in Figure 4. In this case, the neutron data is relatively well defined (green mesh in Figure 4). However, only when electrostatics are used for the joint neutron/X-ray refinement (both OPLS-AA-X, Figure 4B, and AMOEBA, Figure 4C) do we observed the hydrogen bonds for the N4-water-water-N4 bridge (see water molecules W1 and W2). Interestingly, the OPLS-AA-X and AMOEBA-based refinements result in a different orientation of water molecule W2, the latter forming an additional hydrogen bond that is part of an extensive hydrogen bonding network that bridge two symmetry mates (tan DNA molecules in Figure 4). We speculate that this cross-symmetry hydrogen-bonding network stabilizes crystal contacts in a manner similar to the role of ions in B-DNA crystal forms (Minasov et al., 1999). This more extensive hydrogen bonding network for the AMOEBA based refinement compared to the OPLS-AA-X based refinement is also reflected in the higher ratio of hydrogen bonds (Table 1). The difference was further analyzed by omitting water molecules W1 and W2 from the model and calculating annealed omit-maps (Figure S1, related to Figure 4). The difference nuclear density around both water molecules is in better agreement with the AMOEBA-based refinement (Figure S1B, related to Figure 4C) versus the OPLS-AA-X based refinement (Figure S1A, related to Figure 4B). Thus, it would have been possible to deduce the hydrogen bonding pattern from inspection of such omit difference neutron density maps alone, but it is gratifying that the AMOEBA-based refinement achieves this pattern without manual inspection.

Figure 4.

Cytosine N4-water and phosphate hydration in Z-DNA. Panels follow the same order and density rendering as in Figure 3. Symmetry related molecules are colored in tan.

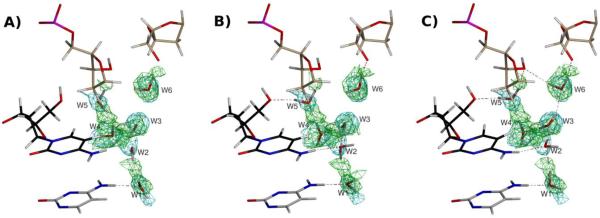

Similar to the zig-zag spine of hydration described for B-DNA, a spine of hydration has likewise been noted for Z-DNA. In the case of a CG dinucleotide repeat (as described here), the hydration spine takes the form of an interstrand water bridge between neighboring O2 oxygen atoms on cytosine residues (Wang et al., 1984; Egli et al., 1991; Bancroft et al., 1994; Gessner et al., 1994; Chatake et al., 2005). The consistency of this water bridge led to proposals regarding stability of CG over AT dinucleotide repeats based on free energy measurements and calculations (Ho and Mooers, 1997 and references therein), the latter of which does not indicate a hydration spine (Wang et al., 1984; Ho et al., 1997). The results of the joint neutron/X-ray refinements in the region of the hydration spine are shown in Figure 5. The apparent feature in all three refinements - refined either with or without electrostatics - indicate that the hydration spine is not a prevalent feature in ZDNA, as only one of five waters in the spine (the water molecule at the top of Figure 5B–C) forms the expected hydrogen bonding pattern. Surprised by this result, we refined an independently determined Z-DNA structure with X-ray data to atomic resolution (0.95 Å, PDB ID 1ICK (Dauter and Adamiak, 2001)) using the AMOEBA force field. The resultant model from this re-refinement also does not support the hydration spine (Figure S2, related to Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Hydration spine in Z-DNA. Panels follow the same order and density rendering as in Figure 3. See also Figure S2.

To further analyze this unexpected result, we compared the primary hydration spine bonding geometry in the minor groove of B- versus Z-DNA (Figure 6). In B-DNA (Figure 6A–B), the two thymine bases that act as hydrogen bonding acceptors are offset from one another, which allows the bridging water molecule to interact with the lone pair electrons on both bases at a distance that is optimal for a hydrogen bond (approximately 1.9 Å, Figure 6B). In Z-DNA, however, the differing geometry leads to more closely stacked cytosine bases (compare Figure 6C with Figure 6A). For the bridging water molecule to interact with both bases in this case, it must straddle the axis formed by the O2 atoms of the two cytosine bases in order to form an electrostatic interaction with the lone pair electrons, which primarily lie in the plane of the base. This also requires the water molecule to lie at a distance that is reasonable for the electrostatic interaction to take place, which is difficult to achieve given the stacked cytosine geometry. This results in an overall poor hydrogen bonding geometry, evidenced by a calculated ~2kcal/mol weaker hydrogen bond interaction in Z-DNA versus B-DNA (based on comparing a primary spine water from the B-DNA result for PDB ID 1ENN as shown in Figure 1 and the Z-DNA result shown in Figure 5C, computed using the AMOEBA force field).

Figure 6.

Difference in hydrogen bonding geometry in B-DNA (A, B) versus Z-DNA (C, D). Distance from the hydrogen/deuterium atom to the O2 position on thymines is given in Å.

Xylose Isomerase

We applied joint neutron/X-ray refinement with electrostatics to a recently collected neutron and matching X-ray diffraction data set of xylose isomerase (Kovalevsky et al., 2010). The position of hydrogen atoms is of relevance given the importance of water/hydrogen in the mechanism of this enzyme. Briefly, the enzyme catalyzes ring opening of sugar monomers, followed by metal-dependent isomerization - via a hydride shift mechanism - between the aldo and keto (with the carbonyl at C2) forms of the sugar (Suekane et al., 1978; Farber et al., 1989; Collyer and Blow, 1990; Collyer et al., 1990; Lee et al., 1990; Allen, Lavie, Farber, et al., 1994; Hu et al., 1997). In general, xylose isomerases tend to favor the aldo form of pentoses (e.g. 88% to 12% for xylose and xylulose at equilibrium, respectively), although hexoses (e.g. glucose) also serve as substrates, albeit at a two to three order of magnitude depressed efficiency (van Bastelaere et al., 1991). This latter point is of industrial importance, as column-immobilized whole-cells expressing xylose isomerase is the principal method of generating high fructose corn syrup for use as a sugar substitute/food sweetener (for a review of the industrial aspects of xylose isomerase, see Bhosale et al. (Bhosale et al., 1996)). Also of crystallographic relevance is the hydride transfer step, which involves metal stabilization of a general acid/base water/hydroxide ion and metal-induced polarization of the substrate to lower the energy barrier for hydride transfer (Schray and Rose, 1971; Allen, Lavie, Glasfeld, et al., 1994; Lavie et al., 1994; Fuxreiter et al., 1995; Hu et al., 1997; Fenn et al., 2004).

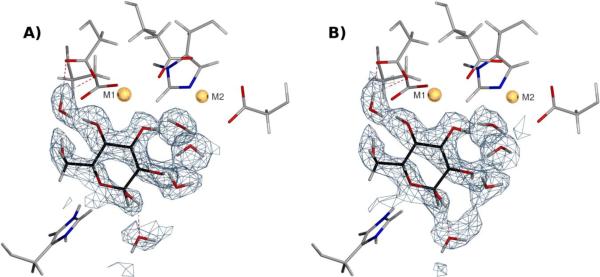

The active site of xylose isomerase with bound perdeuterated, cyclic α-D-glucose is shown in Figure 7. along with the 2Fo-Fc nuclear density map resulting from joint neutron/X-ray refinement using the Repel and OPLS-AA-X force fields. Unfortunately, limitations in the AMOEBA implementation in TINKER currently preclude the application to large structures such as xylose isomerase. The hydrogen bonding in the OPLS-AA-X based refinement is primarily dictated by the strong electric field at the two metal centers (Co2+ in the case presented), which orients the sugar OD3 and OD4 deuterium atoms away from the ion (M1 in Figure 7). This orientation is in agreement with the result obtained using the Repel force field (Figure 7A). The majority of the water molecule orientations are unchanged upon refinement with and without electrostatics, resulting in a low number of hydrogen bonds at the active site. Inclusion of electrostatics tends to primarily affect regions where the nuclear density is not clearly defined (Figure S3, related to Figure 7), leading to an overall improvement in the water molecule hydrogen bonding geometry (Table 1).

Figure 7.

Xylose isomerase active site, with the bound perdeuterated glucose rendered in black. Active site metal ions are rendered in gold. (A) Result from joint refinement with the 2.0 Å neutron diffraction data (PDB ID 3KCL) and with corresponding X-ray data of the same resolution (PDB ID 3KBM) using the Repel force field (i.e. without electrostatics). (B) As in (A), but with the OPLS-AA-X force field (i.e. electrostatics computed using a real space cutoff of 8.5 Å). Light blue mesh represents σA weighted 2Fo−Fc nuclear density contoured at 1.5 σ. See also Figure S3.

Discussion

Macromolecular diffraction techniques are utilized in an increasing number of biological applications over an increasingly larger resolution range. Many of the questions posed and structural models that are generated stand to benefit from a physics-based force field, as the results here indicate. Although the presented examples are primarily restricted to solvent related hydrogen bonding patterns/geometries due to the inclusion of electrostatics, it is important to point out the crucial role of electrostatics in alpha helix and beta sheet stabilization, and protein stabilization overall: studies have suggested approximately 82% of a protein hydrogen atoms are involved in hydrogen bonding (Baker and Hubbard, 1984; Sticke et al., 1992), with an energetic benefit of up to 2 kcal/mol for each hydrogen bond formed (Fersht and Serrano, 1993; Pace et al., 1996). Therefore, physics-based force fields are likely to significantly affect heavy atom positioning and assist in keeping secondary and tertiary structures intact during refinement. This is a significant issue for low resolution crystal structures, for which additional restraints are sometimes used to maintain secondary structure and proper hydrogen bonding (Brunger, 2005). Conversely, hydrogen orientation/bonding is often the motive for determining sub-atomic X-ray crystal structures, for which an improved force field is also of utility (Fenn et al., 2010).

The refinements with force fields that include electrostatics produce energetically more favorable hydrogen bonds and more canonical O-O water-water bond distances (Table 1). In the DNA examples, the AMOEBA-based refinements result in a further improvement, as determined by inspection of omit nuclear density maps (Figure 4 and Figure S1) and hydrogen bonding statistics (Table 1). Further, the models refined with electrostatics agree with theory and independent experiments regarding solvent structure in the minor groove of B-DNA (Figure 2) and offer new insight regarding the stability and structure of the hydration spine in Z-DNA (Figure 5–6 and discussion below). Conversely, structures refined with the commonly used repulsive force field without electrostatics do not converge to the same hydrogen-bonding network, especially for cases where the neutron diffraction data do not uniquely determine the hydrogen positions. Even at high resolution and with complete neutron diffraction data electrostatics is a useful complement and can assist careful modeling, as observed for xylose isomerase (Figure 7 and Figure S3).

Liquid water hydrogen bonds break at a rate of approximately 1ps (Luzar and Chandler, 1996; Steinel et al., 2004), whereas hydrogen bonds formed at the interior of proteins can be stable for tens of milliseconds (Otting et al., 1991). Therefore, an important aspect we have not discussed or addressed here regards the dynamic nature of hydrogen bond networks, and the possibility that hydrogen atoms may not be well defined in terms of their position during the course of a crystallographic experiment. These networks can be modeled as discrete conformers (as is typically done in macromolecular crystallography), although the dynamic nature of some hydrogen bonds may not be adequately modeled in this fashion. Therefore, future methods utilizing ensemble-based approaches coupled with electrostatics may be of utility in this regard (Rice et al., 1998).

Our results show differences in hydrogen bonding/orientation results between the OPLS-AA-X and AMOEBA force fields. It is possible that the differences result from the fixed charge OPLS-AA-X versus the polarizable atomic multipole AMOEBA force fields or the use of spherical cutoffs versus the particle mesh Ewald method of computing electrostatics. Both of these factors play a role in the energetics and stability of a given water molecule orientation, particularly in periodic systems. The improved agreement versus the neutron diffraction data with the AMOEBA models (as assessed by annealed omit maps, Figure S1) and higher prevalence of hydrogen bonding (Table 1) suggests that the more physical representations available with this description is desirable over using the OPLS-AA-X force field with spherical cutoffs, although the latter force field offers benefits over not using electrostatics at all. However, it is important to recall that lattice summations computed with a spherical cutoff are expected to contain systematic errors due to lack of convergence of the electrostatic energy (Sagui et al., 1999; Karttunen et al., 2008 and references therein).

The ability of DNA to be stabilized in different conformations is widely recognized to be crucial to its biological function. The equilibrium between the right handed B and left handed Z forms is complex and poorly understood, but the thermodynamics is thought to be influenced by several factors including hydration, ionic strength and toplogical stress (Fuertes et al., 2006). Early on it was established that the formation of Z-DNA, in particular with the sequence described here, is most likely driven by entropy (Pohl and Jovin, 1972). However, molecular dynamics studies suggest Z-DNA is more rigid than B-DNA (Irikura et al., 1985), implying that solvent entropy must play a significant role in the thermodynamics of the equilibrium from B- to Z-DNA. The finding that the minor groove hydration spine is predominantly disordered - as observed here with all three methods of computing hydrogen bonding geometry which include both X-ray and neutron diffraction data - is not expected (Wang et al., 1984; Laaksonen et al., 1989; Egli et al., 1991; Bancroft et al., 1994; Gessner et al., 1994; Chatake et al., 2005), but is reasonable given the differences in hydrogen bonding geometry (Figure 6). Further, if the primary spine were ordered, it is reasonable to also expect a secondary spine bridging the primary water molecules as observed with B-DNA, but this is not the case. We therefore propose the primary water spine in Z-DNA is disordered, and most likely prefers to form transient hydrogen bonds with the cytosine O2 atoms (Figure 5 and Figure S2). If this is the case, it is interesting to speculate as to the possibility that the increased disorder in the primary spine represents an increase in entropy upon transiting from B- to Z-DNA, thereby partly explaining the observed free energy difference (Pohl et al., 1972). Recent simulations on B-DNA suggest a gain in entropic free energy of 0.9 kcal/mol for each water molecule moving from the minor groove to bulk solution, suggesting the water molecules that occupy the spine have a significant effect, providing some support to this theory (Jana et al., 2006). This conclusion would be difficult to attain without the combination of crystallographic data and rigorous electrostatics.

It has been noted for some time that medium resolution neutron density “is not sufficiently resolved to orient the water hydrogens precisely” (Finer-Moore et al., 1992), a shortcoming that can be partly compensated by use of more physics-based force fields during refinement, as described here. Even for high resolution neutron structures, the joint neutron/X-ray refinement using the OPLS-AA-X or AMOEBA force fields provides a means of automating water molecule building, one of the more laborious and subjective tasks in structure refinements against neutron diffraction data and joint neutron/X-ray diffraction data. The improved force fields that are used in this work and elsewhere (Schnieders et al., 2009; Fenn et al., 2010) suggest a more wide-spread “resurrection” of refinements that include electrostatics as had been initially used in crystallographic refinement (Weis et al., 1990). We expect that such refinements will improve hydrogen bonding geometry and yield more chemically reasonable models for studies of catalysis, drug design, ligand binding and molecular stability, systems for which electrostatics plays a major role. Indeed, the need for rigorous electrostatics methods (Warshel and Papazyan, 1998) and advanced force fields (Morozov et al., 2004) in structural biology has been stressed in the past, which we believe the results presented here partly fulfill. However, we note that the inclusion of implicit solvent to model disordered solvent and counter-ion atmospheres in crystals remains an area that needs further development in the context of crystallographic refinement, as the current exclusion of such phenomena may lead to spurious hydrogen bonding patterns involving charged groups (Weis et al., 1990; Moulinier et al., 2003; Korostelev et al., 2004). This will be particularly important during the early stages of refinement, when solvent networks and side chain orientations are incomplete and/or incorrect. Therefore, the proposed methods are best utilized at the final stages of refinement to avoid artifacts resulting from incomplete electrostatics.

Experimental Procedures

B-DNA and xylose isomerase models

The neutron diffraction data for the B-DNA (dGCGAATTCG) was obtained from PDB ID 1WQZ (at 2.5 Å resolution) and corresponding X-ray diffraction data from PDB ID 1WQY (at 1.6 Å resolution) (Arai et al., 2005). The neutron diffraction data for xylose isomerase was obtained from PDB ID 3KCL (at 2.0 Å resolution) and the corresponding X-ray diffraction data from PDB ID 3KBM (at 2.0 Å resolution) (Kovalevsky et al., 2010). In both cases, the deposited neutron models were used as starting models for the model refinement, detailed below. Water molecules lacking deuterium atoms were fully deuterated prior to refinement.

Z-DNA

Synthesis, crystallization and preliminary X-ray and neutron data collection for Z-DNA have been previously described (Langan et al., 2006). For this study additional neutron diffraction data were collected using the Protein Crystallography Station (PCS) at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center (Langan et al., 2008) in order to improve completeness and resolution (resolution: 1.4 Å; completeness 90%). The data collection statistics are provided in Table 2. The X-ray data statistics are as given in Langan et al., 2006. The final, deposited atomic models (neutron: PDB ID 3QBB and X-ray: PDB ID 3QBA) included discrete disorder at three phosphate backbone positions, and the statistics for this model with respect to both the X-ray and neutron data is given in Table S1 (Related to Table 2).

Crystallographic Refinements

Refinement of each model was performed using an updated version of nCNS (Langan et al., 2008; Adams et al., 2009) using CNS v1.3 as the base (Schroder et al., 2010) (the nCNS patch for CNS v1.3 is available upon request from M.M. and P.L.). In addition, an interface between this new version of nCNS and TINKER was implemented as previously described (Schnieders et al., 2009). In the case of B-DNA and xylose isomerase, hydrogen/deuterium assignments and positions were left unaltered from the deposited coordinates. All refinements included hydrogen atoms (including aliphatic groups). Refinement was carried out using a maximum likelihood amplitude based target function that combined the X-ray diffraction maximum likelihood term, neutron diffraction maximum likelihood term, and force field energy:

| (1) |

Refinements were carried out with one of three force fields: the first force field used the all hydrogen parameters for proteins and nucleic acids as implemented in CNS v1.3 that incorporates non-hydrogen target and energy values for bond, angle and dihedral potentials as described by Engh and Huber (Engh et al., 1991) and Parkison et al. (Parkinson et al., 1996) along with a purely repulsive nonbonded potential function without electrostatics (Adams et al., 1997) (referred to as “Repel,” the topology and parameter files “protein-allhdg5-4.*”, “dna-rna-allatom-hj-opls.*”, and “water-allhdg5-4.*” were used with no electrostatics and the “repel” option). The second force field used the same non-hydrogen bond lengths, angles and dihedral terms as the “Repel” force field, but with the OPLSAA nonbonded potential (Jorgensen et al., 1988) which includes van der Waals and electrostatic potentials, computed using a real space spherical cutoff of 8.5 Å with a switching function that begins taking effect at 6.5 Å, and the CHARM22 version of the TIP3P water model (but with stiff, not fixed bond lengths and angles with energy constants of 1000 kcal/mol/Å2 and 500 kcal/mol, respectively) as implemented in CNS v.1.3, revision 3 (simply referred to as the “OPLS-AA-X” force field, the toplogy and parameter files “protein-allhdg5-4.*”, “dna-rna-allatom-hj-opls.*” and “water-allhdg5-4.*” were used in conjunction with the “electrostatics.settings” file in CNS version 1.3, revision 3) (Linge et al., 2003; Nozinovic et al., 2010). The third force field is the all-hydrogen polarizable AMOEBA force field (Ren et al., 2003, 2004) as implemented in TINKER (which includes van der Waals and PME electrostatic terms (Sagui et al., 2004), referred to as “AMOEBA”). For the PME summation, we used a real space cutoff of 7.0 Å, an Ewald coefficient of 0.545, grid spacing of 1.2 Å−1, and 5th order B-splines. The weights (wA and wB) were set to 1.0 in all cases, i.e. we did not perform Rfree based optimization of these weights. Three cycles of refinement were carried out for each, which consisted of 250 rounds of positional and 100 rounds of B-factor based minimization. In the xylose isomerase test case, the system size was too large for TINKER when expanded to spacegroup P1, and therefore only the Repel and OPLS-AA-X force fields could be tested for this case.

Contour levels of X-ray and nuclear density maps

The standard deviation (σ) of a Fourier map is often used as the unit for the contour levels in the map. For example, contours might be drawn at 1.5 σ, at 3 σ, and at other multiples of σ. The sigma value is calculated by the following equation:

| (2) |

where ρ is the electron density for XPC and the nuclear density for NPC. N is the number of grid points in a unit cell. For electron density (2Fo-Fc) maps, hydrogen atoms have negative true values of scattering lengths, leading to holes in the map. Therefore, the deviations with respect to the mean are larger for nuclear density maps, and as a result, becomes larger. This means that the same value of represents a stronger signal in NPC maps that in electron density maps. Therefore, all Figures used lower contour levels when displaying nuclear density versus electron density.

Model Evaluation

To construct Table 1, we wrote a computer program to systematically search for hydrogen bond donors/acceptors with the assistance of the CCP4 coordinate library (Krissinel et al., 2004). Each water hydrogen atom (or deuterium in the case of neutron structures) was analyzed by searching for water oxygen atoms within 2.5 Å of the hydrogen, including symmetry mates. The Ow-Hw-A angle was then checked, and only angles within 180 ± 40° were considered for analysis. The program is available upon request.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Aaron Moulin for discussions regarding neutron diffraction and Paul Sigala for comments and suggestions on the initial manuscript. The neutron diffraction data for the Z-DNA and xylose isomerase crystal structures were collected at the Protein Crystallography Station (PCS) at Los Alamos National Laboratory. The PCS is funded by the Office of Environmental Research of the Department of Energy. The PCS is located at the Lujan Center at Los Alamos Neutron Science Center, funded by the DOE office of Basic Energy Sciences. M.M. And P.L. Were partly supported by an NIH-NIGMS grant (R01GM071939). M.J.S. was supported by NSF grant CHE-0535675.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adams PD, Mustyakimov M, Afonine PV, Langan P. Generalized X-ray and neutron crystallographic analysis: more accurate and complete structures for biological macromolecules. Acta. Cryst. 2009;D 65:567–573. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909011548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams PD, Pannu NS, Read RJ, Brünger AT. Cross-validated maximum likelihood enhances crystallographic simulated annealing refinement. PNAS. 1997;94:5018–5023. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KN, Lavie A, Farber GK, Glasfeld A, Petsko GA, Ringe D. Isotopic Exchange plus Substrate and Inhibition Kinetics of D-Xylose Isomerase Do Not Support a Proton-Transfer Mechanism. Biochem. 1994;33:1481–1487. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen KN, Lavie A, Glasfeld A, Tanada TN, Gerrity DP, Carlson SC, Farber GK, Petsko GA, Ringe D. Role of the Divalent Metal Ion in Sugar Binding, Ring Opening, and Isomerization by D-Xylose Isomerase: Replacement of a Catalytic Metal by an Amino Acid. Biochem. 1994;33:1488–1494. doi: 10.1021/bi00172a027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai S, Chatake T, Ohhara T, Kurihara K, Tanaka I, Suzuki N, Fujimoto Z, Mizuno H, Niimura N. Complicated water orientations in the minor groove of the B-DNA decamer d(CCATTAATGG)2 observed by neutron diffraction measurements. Nucl. Acid Res. 2005;33:3017–3024. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacon GE, Lonsdale K. Neutron diffraction. Reports on Progress in Physics. 1953;16:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Baker E, Hubbard RE. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Bio. 1984;44:97–179. doi: 10.1016/0079-6107(84)90007-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bancroft D, Williams LD, Rich A, Egli M. The low-temperature crystal structure of the pure-spermine form of Z-DNA reveals binding of a spermine molecule in the minor groove. Biochemistry. 1994;33:1073–1086. doi: 10.1021/bi00171a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Bastelaere P, Vangrysperre W, Kersters-Hilderson H. Kinetic studies of Mg(2+)-, Co(2+)- and Mn(2+)-activated D-xylose isomerases. Biochem. J. 1991;278:285–292. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhosale S, Rao M, Deshpande V. Molecular and industrial aspects of glucose isomerase. Microbiol. Rev. 1996;60:280–300. doi: 10.1128/mr.60.2.280-300.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blakeley MP, Langan P, Niimura N, Podjarny A. Neutron crystallography: opportunities, challenges, and limitations. Curr. Op. Struct. Bio. 2008;18:593–600. doi: 10.1016/j.sbi.2008.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks BR, Bruccoleri RE, Olafson BD, States DJ, Swaminathan S, Karplus M. CHARMM: A program for macromolecular energy, minimization, and dynamics calculations. J. Comp. Chem. 1983;4:187–217. [Google Scholar]

- Brünger AT, Kuriyan J, Karplus M. Crystallographic R Factor Refinement by Molecular Dynamics. Science. 1987;235:458–460. doi: 10.1126/science.235.4787.458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunger AT. Low-Resolution Crystallography Is Coming of Age. Structure. 2005;13:171–172. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatake T, Ostermann A, Kurihara K, Parak FG, Niimura N. Hydration in proteins observed by high-resolution neutron crystallography. Proteins. 2003;50:516–523. doi: 10.1002/prot.10303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatake T, Tanaka I, Umino H, Arai S, Niimura N. The hydration structure of a Z-DNA hexameric duplex determined by a neutron diffraction technique. Acta Cryst. 2005;D 61:1088–1098. doi: 10.1107/S0907444905015581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Weber I, Harrison RW. Hydration Water and Bulk Water in Proteins Have Distinct Properties in Radial Distributions Calculated from 105 Atomic Resolution Crystal Structures. J. Phys. Chem. 2008;B 112:12073–12080. doi: 10.1021/jp802795a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu TK, Kaczor-Grzeskowiak M, Dickerson RE. Absence of minor groove monovalent cations in the crosslinked dodecamer C-G-C-G-A--T-T-C-G-CG. JMB. 1999;292:589–608. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuprina VP, Heinemann U, Nurislamov AA, Zielenkiewicz P, Dickerson RE, Saenger W. Molecular dynamics simulation of the hydration shell of a B-DNA decamer reveals two main types of minor-groove hydration depending on groove width. PNAS. 1991;88:593–597. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.2.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collyer CA, Blow DM. Observations of reaction intermediates and the mechanism of aldose-ketose interconversion by D-xylose isomerase. PNAS. 1990;87:1362–1366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collyer CA, Henrick K, Blow DM. Mechanism for aldose-ketose interconversion by -xylose isomerase involving ring opening followed by a 1,2-hydride shift. JMB. 1990;212:211–235. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90316-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darden T, York D, Pedersen L. Particle mesh Ewald: An N · log(N) method for Ewald sums in large systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;98:10089–10092. [Google Scholar]

- Dauter Z, Adamiak DA. Anomalous signal of phosphorus used for phasing DNA oligomer: importance of data redundancy. Acta Cryst. 2001;D 57:990–995. doi: 10.1107/s0907444901006382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson WL, Morton GA, Shull CG, Wollan EO. Neutron diffraction analysis of NaH and NaD. Atomic Energy Commission; Washington, DC: 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Desiraju GR, Steiner T. The Weak Hydrogen Bond: In Structural Chemistry and Biology. Oxford University Press; USA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Drew HR, Dickerson RE. Structure of a B-DNA dodecamer: III. Geometry of hydration. JMB. 1981;151:535–556. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(81)90009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egli M, Williams LD, Gao Q, Rich A. Structure of the pure-spermine form of Z-DNA (magnesium free) at 1-.ANG. resolution. Biochem. 1991;30:11388–11402. doi: 10.1021/bi00112a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engh RA, Huber R. Accurate bond and angle parameters for X-ray protein structure refinement. Acta. Cryst. 1991;A 47:392–400. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson MAL, Laaksonen A. A molecular dynamics study of conformational changes and hydration of left-handed d (CGCGCGCGCGCG)2 in a nonsalt solution. Biopolymers. 1992;32:1035–1059. doi: 10.1002/bip.360320814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewald PP. Die Berechnung optischer und elektrostatischer Gitterpotentiale. Annalen der Physik. 1921;369:253–287. [Google Scholar]

- Farber GK, Glasfeld A, Tiraby G, Ringe D, Petsko GA. Crystallographic studies of the mechanism of xylose isomerase. Biochem. 1989;28:7289–7297. doi: 10.1021/bi00444a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fawthrop SA, Yang J, Fisher J. Structural and dynamic studies of a non-selfcomplementary dodecamer DNA duplex. Nucl. Acids Res. 1993;21:4860–4866. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.21.4860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. POVScript+: a program for model and data visualization using persistence of vision ray-tracing. J. Appl. Cryst. 2003;36:944–947. [Google Scholar]

- Fenn TD, Ringe D, Petsko GA. Xylose isomerase in substrate and inhibitor michaelis states: atomic resolution studies of a metal-mediated hydride shift. Biochem. 2004;43:6464–6474. doi: 10.1021/bi049812o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenn TD, Schnieders MJ, Brunger AT, Pande VS. Polarizable Atomic Multipole X-Ray Refinement: Hydration Geometry and Application to Macromolecules. Biophys. J. 2010;98:2984–2992. doi: 10.1016/j.bpj.2010.02.057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersht AR, Serrano L. Principles of protein stability derived from protein engineering experiments. Curr. Op. Struct. Bio. 1993;3:75–83. [Google Scholar]

- Finer-Moore JS, Kossiakoff AA, Hurley JH, Earnest T, Stroud RM. Solvent structure in crystals of trypsin determined by X-ray and neutron diffraction. Proteins. 1992;12:203–222. doi: 10.1002/prot.340120302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes MA, Cepeda V, Alonso C, Pérez JM. Molecular Mechanisms for the B-Z Transition in the Example of Poly[d(G-C)·d(G-C)] Polymers. A Critical Review. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:2045–2064. doi: 10.1021/cr050243f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuxreiter M, Farkas Ö, Náray-Szabó G. Molecular modelling of xylose isomerase catalysis: the role of electrostatics and charge transfer to metals. Protein Eng. 1995;8:925–933. doi: 10.1093/protein/8.9.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gessner RV, Quigley GJ, Egli M. Comparative studies of high resolution Z-DNA crystal structures Part 1: Common hydration patterns of alternating dC-dG. JMB. 1994;236:1154–1168. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(94)90018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho PS, Mooers BHM. Z-DNA crystallography. Biopolymers. 1997;44:65–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1997)44:1<65::AID-BIP5>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou M, Lin S, Yuann JP, Lin W, Wang AH, Kan L. Effects of polyamines on the thermal stability and formation kinetics of DNA duplexes with abnormal structure. Nucl. Acid Res. 2001;29:5121–5128. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.24.5121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Liu H, Shi Y. The reaction pathway of the isomerization of d-xylose catalyzed by the enzyme d-xylose isomerase: A theoretical study. Proteins. 1997;27:545–555. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0134(199704)27:4<545::aid-prot7>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irikura K, Tidor B, Brooks B, Karplus M. Transition from B to Z DNA: contribution of internal fluctuations to the configurational entropy difference. Science. 1985;229:571–572. doi: 10.1126/science.3839596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jana B, Pal S, Maiti PK, Lin S, Hynes JT, Bagchi B. Entropy of Water in the Hydration Layer of Major and Minor Grooves of DNA. J. Phys. Chem. 2006;B 110:19611–19618. doi: 10.1021/jp061588k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen WL, Tirado-Rives J. The OPLS [optimized potentials for liquid simulations] potential functions for proteins, energy minimizations for crystals of cyclic peptides and crambin. JACS. 1988;110:1657–1666. doi: 10.1021/ja00214a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karttunen M, Rottler J, Vattulainen I, Sagui C. Computational Modeling of Membrane Bilayers. Academic Press; 2008. Electrostatics in biomolecular simulations: Where are we now and where are we heading? pp. 49–89. [Google Scholar]

- Korostelev A, Fenley MO, Chapman MS. Impact of a Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatic restraint on protein structures refined at medium resolution. Acta Cryst. 2004;D 60:1786–1794. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovalevsky AY, Hanson L, Fisher SZ, Mustyakimov M, Mason SA, Trevor Forsyth V, Blakeley MP, Keen DA, Wagner T, Carrell H, et al. Metal Ion Roles and the Movement of Hydrogen during Reaction Catalyzed by D-Xylose Isomerase: A Joint X-Ray and Neutron Diffraction Study. Structure. 2010;18:688–699. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krissinel EB, Winn MD, Ballard CC, Ashton AW, Patel P, Potterton EA, McNicholas SJ, Cowtan KD, Emsley P. The new CCP4 Coordinate Library as a toolkit for the design of coordinate-related applications in protein crystallography. Acta. Cryst. 2004;D 60:2250–2255. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904027167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubinec MG, Wemmer DE. NMR evidence for DNA bound water in solution. JACS. 1992;114:8739–8740. [Google Scholar]

- Laaksonen A, Nilsson LG, Jönsson B, Teleman O. Molecular dynamics simulation of double helix Z-DNA in solution. Chem. Phys. 1989;129:175–183. [Google Scholar]

- Langan P, Fisher Z, Kovalevsky A, Mustyakimov M, Sutcliffe Valone A, Unkefer C, Waltman MJ, Coates L, Adams PD, Afonine PV, et al. Protein structures by spallation neutron crystallography. J. Synchrotron Rad. 2008;15:215–218. doi: 10.1107/S0909049508000824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langan P, Li X, Hanson BL, Coates L, Mustyakimov M. Synthesis, capillary crystallization and preliminary joint X-ray and neutron crystallographic study of Z-DNA without polyamine at low pH. Acta Cryst. 2006;F 62:453–456. doi: 10.1107/S174430910601236X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan T, McLaughlin LW. Minor groove hydration is critical to the stability of DNA duplexes. JACS. 2000;122:6512–6513. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie A, Allen KN, Petsko GA, Ringe D. X-ray Crystallographic Structures of D-Xylose Isomerase-Substrate Complexes Position the Substrate and Provide Evidence for Metal Movement during Catalysis. Biochem. 1994;33:5469–5480. doi: 10.1021/bi00184a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CY, Bagdasarian M, Meng MH, Zeikus JG. Catalytic mechanism of xylose (glucose) isomerase from Clostridium thermosulfurogenes. Characterization of the structural gene and function of active site histidine. JBC. 1990;265:19082–19090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liepinsh E, Otting G, Wuthrich K. NMR observation of individual molecules of hydration water bound to DNA duplexes: direct evidence for a spine of hydration water present in aqueous solution. Nucl. Acids Res. 1992;20:6549–6553. doi: 10.1093/nar/20.24.6549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linge JP, Williams MA, Spronk CA, Bonvin AMJJ, Nilges M. Refinement of protein structures in explicit solvent. Proteins. 2003;50:496–506. doi: 10.1002/prot.10299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luzar A, Chandler D. Hydrogen-bond kinetics in liquid water. Nature. 1996;379:55–57. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.76.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minasov G, Tereshko V, Egli M. Atomic-resolution crystal structures of B-DNA reveal specific influences of divalent metal ions on conformation and packing. JMB. 1999;291:83–99. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morozov AV, Kortemme T, Tsemekhman K, Baker D. Close agreement between the orientation dependence of hydrogen bonds observed in protein structures and quantum mechanical calculations. PNAS. 2004;101:6946–6951. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0307578101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulinier L, Case DA, Simonson T. Reintroducing electrostatics into protein X-ray structure refinement: bulk solvent treated as a dielectric continuum. Acta. Cryst. 2003;D 59:2094–2103. doi: 10.1107/s090744490301833x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nozinovic S, Fürtig B, Jonker HRA, Richter C, Schwalbe H. High-resolution NMR structure of an RNA model system: the 14-mer cUUCGg tetraloop hairpin RNA. Nucl. Acid Res. 2010;38:683–694. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otting G, Liepinsh E, Wuthrich K. Protein hydration in aqueous solution. Science. 1991;254:974–980. doi: 10.1126/science.1948083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace C, Shirley B, McNutt M, Gajiwala K. Forces contributing to the conformational stability of proteins. FASEB J. 1996;10:75–83. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.10.1.8566551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parkinson G, Vojtechovsky J, Clowney L, Brünger AT, Berman HM. New parameters for the refinement of nucleic acid-containing structures. Acta Cryst. 1996;D 52:57–64. doi: 10.1107/S0907444995011115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl FM, Jovin TM. Salt-induced co-operative conformational change of a synthetic DNA: Equilibrium and kinetic studies with poly(dG-dC) JMB. 1972;67:375–396. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(72)90457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder JW, Case DA. Force fields for protein simulations. Adv. Prot. Chem. 2003;66:27–85. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3233(03)66002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder JW, Wu C, Ren P, Pande VS, Chodera JD, Schnieders MJ, Haque I, Mobley DL, Lambrecht DS, DiStasio RA, et al. Current Status of the AMOEBA Polarizable Force Field. J. Phys. Chem. 2010;B 114:2549–2564. doi: 10.1021/jp910674d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ren P, Ponder JW. Polarizable atomic multipole water model for molecular mechanics simulation. J. Phys. Chem. 2003;B 107:5933–5947. [Google Scholar]

- Ren P, Ponder JW. Temperature and pressure dependence of the AMOEBA water model. J. Phys. Chem. 2004;B 108:13427–13437. [Google Scholar]

- Rice LM, Shamoo Y, Brünger AT. Phase Improvement by Multi-Start Simulated Annealing Refinement and Structure-Factor Averaging. J. Appl. Cryst. 1998;31:798–805. [Google Scholar]

- Sagui C, Darden TA. Molecular dynamics simulations of biomolecules: long-range electrostatic effects. Ann. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 1999;28:155–179. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.28.1.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sagui C, Pedersen LG, Darden TA. Towards an accurate representation of electrostatics in classical force fields: Efficient implementation of multipolar interactions in biomolecular simulations. J. Chem. Phys. 2004;120:73. doi: 10.1063/1.1630791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders MJ, Baker NA, Ren P, Ponder JW. Polarizable atomic multipole solutes in a Poisson-Boltzmann continuum. J. Chem. Phys. 2007;126:124114–21. doi: 10.1063/1.2714528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders MJ, Fenn TD, Pande VS, Brunger AT. Polarizable atomic multipole X-ray refinement: application to peptide crystals. Acta. Cryst. 2009;D 65:952–965. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909022707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnieders MJ, Ponder JW. Polarizable atomic multipole solutes in a generalized Kirkwood continuum. J. Chem. Theory Comp. 2007;3:2083–2097. doi: 10.1021/ct7001336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schray KJ, Rose IA. Anomeric specificity and mechanism of two pentose isomerases. Biochem. 1971;10:1058–1062. doi: 10.1021/bi00782a019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber H, Steinhauser O. Cutoff size does strongly influence molecular dynamics results on solvated polypeptides. Biochem. 1992;31:5856–5860. doi: 10.1021/bi00140a022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroder GF, Levitt M, Brunger AT. Super-resolution biomolecular crystallography with low-resolution data. Nature. 2010;464:1218–1222. doi: 10.1038/nature08892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soler-Lopez M, Malinina L, Subirana JA. Solvent organization in an oligonucleotide crystal. The structure of d(GCGAATTCG)2 at atomic resolution. JBC. 2000;275:23034–23044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002119200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper AK. Joint structure refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data on disordered materials: application to liquid water. J. Phys. 2007 doi: 10.1088/0953-8984/19/33/335206. Condensed Matter 19, 335206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinel T, Asbury JB, Zheng J, Fayer MD. Watching Hydrogen Bonds Break: A Transient Absorption Study of Water. J. Phys. Chem. 2004;A 108:10957–10964. doi: 10.1021/jp046711r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sticke D, Presta L, Dill K, Rose G. Hydrogen bonding in globular proteins. JMB. 1992;226:1143–1159. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91058-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suekane M, Tamura M, Tomimura C. Physicochemical and enzymatic properties of purified glucose isomerases from Streptomyces olivochromogenes and Bacillus stearothermophilus. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1978;42:909–917. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy KN, Clement E. Hydration structure and dynamics of B- and ZDNA in the presence of counterions via molecular dynamics simulations. Biopolymers. 1987;26:1901–1927. doi: 10.1002/bip.360261106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valls N, Wright G, Steiner RA, Murshudov GN, Subirana JA. DNA variability in five crystal structures of d(CGCAATTGCG) Acta. Cryst. 2004;D 60:680–685. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904002896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang AH, Hakoshima T, van der Marel G, van Boom JH, Rich A. AT base pairs are less stable than GC base pairs in Z-DNA: The crystal structure of d(m5CGTAm5CG) Cell. 1984;37:321–331. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(84)90328-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warshel A, Papazyan A. Electrostatic effects in macromolecules: fundamental concepts and practical modeling. Curr. Op. Struct. Bio. 1998;8:211–217. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(98)80041-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weis WI, Brünger AT, Skehel JJ, Wiley DC. Refinement of the influenza virus hemagglutinin by simulated annealing. JMB. 1990;212:737–761. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(90)90234-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing R, Drew H, Takano T, Broka C, Tanaka S, Itakura K, Dickerson RE. Crystal structure analysis of a complete turn of B-DNA. Nature. 1980;287:755–758. doi: 10.1038/287755a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods KK, Maehigashi T, Howerton SB, Sines CC, Tannenbaum S, Williams LD. High-resolution structure of an extended A-tract: [d(CGCAAATTTGCG)]2. JACS. 2004;126:15330–15331. doi: 10.1021/ja045207x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- York DM, Darden TA, Pedersen LG. The effect of long-range electrostatic interactions in simulations of macromolecular crystals: A comparison of the Ewald and truncated list methods. J. Chem. Phys. 1993;99:8345. [Google Scholar]

- York DM, Yang W, Lee H, Darden T, Pedersen LG. Toward the Accurate Modeling of DNA: The Importance of Long-Range Electrostatics. JACS. 1995;117:5001–5002. [Google Scholar]

- Young M, Ravishanker G, Beveridge D. A 5-nanosecond molecular dynamics trajectory for B-DNA: analysis of structure, motions, and solvation. Biophys. J. 1997;73:2313–2336. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78263-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young MA, Jayaram B, Beveridge DL. Intrusion of counterions into the spine of hydration in the minor groove of B-DNA: fractional occupancy of electronegative pockets. JACS. 1997;119:59–69. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.