Abstract

Background

Childhood cancer survivors may develop a second malignant neoplasm during adulthood and therefore require regular surveillance.

Objective

To examine adherence to population cancer screening guidelines by survivors at average risk of developing a second malignant neoplasm, and to cancer surveillance guidelines by survivors at high risk of developing a second malignant neoplasm.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), a 26 center study of long-term survivors of childhood cancer who were diagnosed between 1970 and 1986.

Patients

4,329 male and 4,018 female survivors of childhood cancer who completed a CCSS questionnaire assessing screening and surveillance for new cancers.

Measurements

Patient-reported receipt and timing of mammography, Papanicolaou smear, colonoscopy, or skin examination was categorized as adherent to the United States Preventive Services Task Force guidelines for survivors at average risk for breast or cervical cancer, or the Children’s Oncology Group guidelines for survivors at high risk for developing breast, colorectal or skin cancer as a result of their therapy.

Results

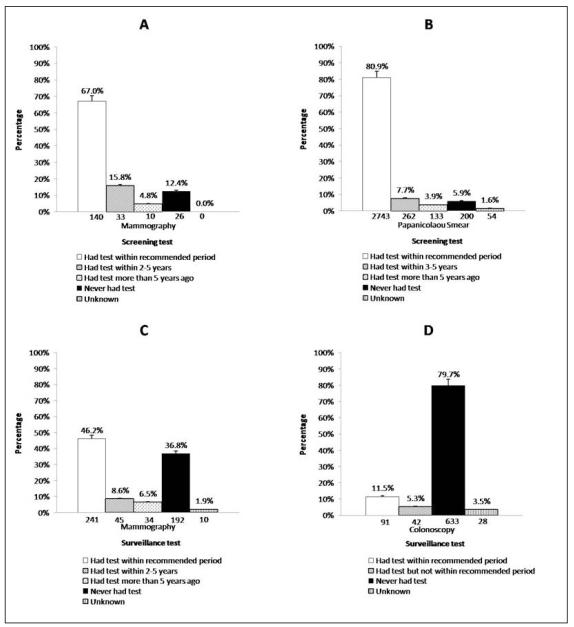

Among average risk female survivors, 2,743/3,392 (80.9%) reported a Papanicolaou smear within the recommended period, and 140/209 (67.0%) reported a mammogram within the recommended period. Among high risk survivors, rates of recommended mammography among females, and colonoscopy and complete skin exams among both genders were only 241/522 (46.2%), 91/794 (11.5%) and 1,290/4,850 (26.6%), respectively.

Limitations

Data were self report. CCSS participants are a select group of survivors and their compliance may not be representative of all childhood cancer survivors.

Conclusions

Female survivors at average risk for developing a second malignant neoplasm demonstrate reasonable rates of screening for cervical and breast cancer. However, surveillance for new cancers is very poor amongst survivors at highest risk for colon, breast or skin cancer, suggesting that survivors and their physicians need education about their risks and the recommended surveillance.

INTRODUCTION

There are over 325,000 survivors of childhood cancer alive in the United States (1), many of whom are at increased risk for the development of a second malignant neoplasm as a result of the therapy for their primary cancer (2-5). Almost 10% of survivors will develop a second malignant neoplasm by 30 years from their initial cancer diagnosis (2), and new malignancies are the most frequent cause of late mortality in patients who survive for more than 20 years after their childhood cancer diagnosis (6, 7). Among childhood cancer survivors who are not considered to be at an increased risk of developing a specific second malignant neoplasm (average risk survivors), adherence to cancer screening guidelines directed at the general population is of particular importance. These screening guidelines are published by organizations such as the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care, and the American Cancer Society. Since many children with cancer receive intensive chemotherapy or radiation, their options for therapy may be limited if they develop a second malignant neoplasm later in life. For example, a female survivor who develops invasive node-positive breast cancer during adulthood may not be able to receive adjuvant doxorubicin if she received anthracycline chemotherapy as treatment for her childhood cancer (8). Adherence to recommended screening for breast or cervical cancer in adult survivors of childhood cancer at average risk may lead to earlier detection and reduced morbidity or mortality, and is therefore imperative.

The use of radiation therapy to treat some childhood malignancies has resulted in breast cancer (4, 5, 9, 10), colorectal cancer and other gastrointestinal malignancies (5, 11-13), malignant melanoma (5, 14, 15) and non-melanoma skin cancer (2, 16) occurring at a younger age and with increased frequency in survivors of childhood cancer when compared to the general population. Studies of other population groups at increased risk for developing one of these neoplasms have demonstrated that more intense surveillance beginning at an earlier age than is recommended for the general population may lead to improved outcome in high-risk individuals (17-22). Consequently, the Children’s Oncology Group (COG) (23, 24) and other national and international groups (25-27) have published consensus-based guidelines for lifelong surveillance for second malignant neoplasms in survivors of childhood cancer who are considered at increased risk of developing a therapy-related malignancy.

In order to evaluate adherence to recommended screening and surveillance in childhood cancer survivors at average or high risk for developing a second malignant neoplasm during adulthood, we assessed these health practices in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) cohort. We evaluated adherence to population screening guidelines in female survivors at average risk of developing breast or cervical cancer. Additionally, we examined adherence to cancer surveillance guidelines in survivors at high risk for developing breast, colorectal or skin cancer as a result of their cancer therapy.

METHODS

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS)

The CCSS methodology and a description of the participants have been published previously (28-30). Briefly, the cohort includes individuals diagnosed with cancer before age 21 years at one of 26 centers (25 US, 1 Canada) from 1970-1986, who were alive at least five years from their original diagnosis. The eligible cohort consisted of 20,626 participants, of whom 17,568 (85.2%) were successfully contacted and 14,357 (69.6%) enrolled in the study. There were no statistically significant differences between participants and non-participants by gender, age at diagnosis, cancer type or treatment (28, 31). Detailed diagnosis and treatment information were systematically abstracted from participants’ hospital records. Participants completed a comprehensive baseline questionnaire and several subsequent questionnaires. Eligibility for this analysis was limited to participants (n=8,347) who completed a questionnaire in 2002-2003 (hereafter referred to as the CCSS 2003 Questionnaire) that addressed cancer screening and surveillance practices, and who had not developed a new neoplasm prior to completing the questionnaire (Online appendix 1). Study instruments are available at http://ccss.stjude.org. The study was approved by Institutional Review Boards at each participating institution and informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Cancer screening in average risk female survivors

We examined female survivors’ adherence to the cervical and breast cancer screening recommendations for the general (average risk) population published by the USPSTF (available at http://www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/uspstfix.htm; summarized in Online appendix 2) (32). We used the guidelines current at the time of the survey (i.e. the 2002 breast cancer guidelines and the 2003 cervical cancer guidelines). The survey questions were designed to mirror those used on the 2003 National Health Interview Survey (33). The USPSTF recommends screening for cervical cancer with a periodic Papanicolaou smear every three years starting at the time of first sexual intercourse or age 21 years, whichever is earlier. Since time of first intercourse was not captured by the study questionnaire, we used age 21 years as the expected time of commencement of screening. The USPSTF recommends a mammogram every one to two years in all women aged 40 years or older. For each screening test, we classified survivors as (i) completing the test within the recommended period; (ii) completing the test, but not within the recommended period; or (iii) never having completed the test. Only those survivors who completed the test within the recommended period were considered to be “adherent” to the guidelines. For example, to assess compliance with mammography screening recommendations, females respondents were asked, “When was the last time you had a mammogram?” and were presented with 6 response options: (i) Never; (ii) Less than 1 year ago; (iii) 1-2 years ago; (iv) More than 2 years but less than 5 years ago; (v) 5 or more years ago; or (vi) Don’t know. Women aged 42 or older (allowing for 2 years from their 40th birthday) who reported a mammogram “less than 1 year ago” or “1-2 years ago” were considered adherent to the guidelines. Canadian survivors were excluded from the breast cancer screening analysis since that country’s guidelines suggest mammography starting at age 50 years (34), rather than age 40 years as was suggested by the USPSTF at the time of the questionnaire. Additionally, survivors who were classified as being at high risk for developing breast cancer were excluded from this analysis of breast cancer screening in average risk individuals, and are included in the analysis of breast cancer surveillance among high risk individuals described below.

Cancer surveillance among female survivors at high risk for breast cancer, and male and female survivors at high risk for colorectal cancer, malignant melanoma or non-melanoma skin cancer

We assessed adherence to the COG Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers (COG LTFU Guidelines; available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org) (23) in all survivors considered to be at increased risk for developing breast cancer, colorectal cancer or skin cancer (malignant melanoma or non-melanoma skin cancer) as a result of their cancer therapy (Online appendix 2). COG defines females at high risk for developing breast cancer as those who received greater or equal to 20 Gray of radiation therapy to the chest, and recommends an annual mammogram beginning eight years after radiation or at age 25 years, whichever occurs last. Survivors are considered at high risk for colorectal cancer if they received greater or equal to 30 Gray of radiation therapy to the abdomen, pelvis or spine. COG recommends a colonoscopy every five years starting at age 35 years for these survivors. Finally, survivors are considered at high risk for skin cancer if they received any radiation therapy, and an annual dermatologic exam of all irradiated areas is recommended.

Predictors of screening and surveillance

Demographic data were obtained on the baseline questionnaire. Socio-demographic status (marital status, health insurance, education) was assessed in the CCSS 2003 Questionnaire. Disease and treatment variables were abstracted from medical records. In order to evaluate the association between health status, chronic medical conditions and surveillance/screening, the severity of chronic health conditions reported on the baseline questionnaire was classified as (0) none; (1) mild; (2) moderate; (3) severe; or (4) life-threatening or disabling using the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3), as published previously (35). Health status was measured using a previously defined set of domains (emotional health, physical function, cancer-related pain, and cancer-related anxiety and fears) (36). Emotional health was assessed with the 18-item Brief Symptom Index, and was classified as poor in patients scoring greater than 63 on this instrument’s global status index (36, 37). Physical function was assessed with the role function-physical subscale of the 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) (38) and was classified as poor in patients scoring below 40. Cancer-related pain and anxiety were assessed separately on a five-point Likert scale and were dichotomized into none or a small amount versus moderate, a lot or extreme (36). In order to evaluate survivors’ concern regarding their future health, they were asked whether the statement, “I expect my health to get worse” was “definitely true”,” mostly true”, “mostly false” or “definitely false”, and their responses were dichotomized as “true” or “false”.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics including frequencies, percentages, means and standard deviations (as appropriate) were calculated for demographic, disease and health status. The proportions of survivors in the average risk and high-risk categories for second malignant neoplasms who adhered to the appropriate screening/surveillance guidelines were calculated and are reported as percentages. The relative risks for adherence to the guidelines were calculated by demographic and health status variables and compared in multiple variable regression models using a log link and a Poisson distribution (39). Demographic, socioeconomic, health history, chronic disease and health status predictors of participation in surveillance were evaluated in multiple variable models if they were independently associated with the outcome (p< 0.10). Independent variable collinearity was evaluated by examining variance inflation factors and tolerance (40). Variables that were highly correlated were not included in the same models. Data analyses were completed with SAS statistical software version 9.2 (Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the study cohort

Of the 9,308 survivors who responded to the CCSS 2003 Questionnaire, 961 were not eligible for this analysis. One did not complete the baseline questionnaire and 960 had developed a second malignant neoplasm. Consequently, there were at total of 8,347 survivors (4,018 female, 4,329 male). The mean age at diagnosis among males was 8.1 years (standard deviation [SD] 5.7 years) and among females was 7.6 years (SD 5.7). The mean age at the time of questionnaire completion was 31.5 years (SD 7.3) and 30.8 years (SD 7.3) for males and females, respectively. Demographic, treatment and health status characteristics of the participants, stratified by gender, are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic, disease and health status data

| Survivors Male (n=4,329) |

Survivors Female (n=4,018) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | N | % | N | % |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| White, Non-Hispanic | 3,842 | 88.7 | 3,536 | 88.0 |

| Non-white | 472 | 10.9 | 468 | 11.6 |

| Not reported | 15 | 0.4 | 14 | 0.4 |

| Cancer diagnosis | ||||

| Leukemia | 1,441 | 33.3 | 1,447 | 36.0 |

| CNS tumor | 562 | 13.0 | 502 | 12.5 |

| Hodgkin lymphoma | 495 | 11.4 | 380 | 9.4 |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 452 | 10.4 | 199 | 5.0 |

| Wilms tumor | 371 | 8.5 | 465 | 11.6 |

| Neuroblastoma | 263 | 6.1 | 336 | 8.4 |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 393 | 9.1 | 346 | 8.6 |

| Bone cancer | 350 | 8.1 | 343 | 8.5 |

| Unknown | 2 | 0.1 | - | - |

| Age group | ||||

| <18 years | 10 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.2 |

| 18-24 years | 959 | 22.2 | 1,033 | 25.7 |

| 25-34 years | 1,971 | 45.5 | 1,827 | 45.5 |

| 35+ years | 1,389 | 32.1 | 1,150 | 28.6 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Single/widowed/divorced or separated | 2,421 | 55.9 | 2,120 | 52.7 |

| Married or living as married | 1,873 | 43.3 | 1,859 | 46.3 |

| Unknown | 35 | 0.8 | 39 | 1.0 |

| Education | ||||

| Post high school or some college | 1,597 | 36.9 | 1,469 | 36.6 |

| High school or less | 1,015 | 23.4 | 806 | 20.0 |

| College or higher | 1,674 | 38.7 | 1,701 | 42.3 |

| Unknown | 43 | 1.0 | 42 | 1.1 |

| Insurance status | ||||

| US Insured or Canadian | 3,683 | 85.1 | 3,520 | 87.6 |

| US not insured | 603 | 13.9 | 470 | 11.7 |

| Unknown | 43 | 1.0 | 28 | 0.7 |

| Concern about future health (Expect worse) | ||||

| False | 3,153 | 72.8 | 3,048 | 75.8 |

| True | 1,145 | 26.5 | 959 | 23.9 |

| Unknown | 31 | 0.7 | 11 | 0.3 |

| Chronic disease status * | ||||

| Grade 0, 1, 2 | 3,449 | 79.7 | 3,027 | 75.3 |

| Grade 3, 4 | 880 | 20.3 | 991 | 24.7 |

| Poor emotional health | ||||

| No | 3,586 | 82.8 | 3,367 | 83.8 |

| Yes | 386 | 8.9 | 397 | 9.9 |

| Unknown | 357 | 8.3 | 254 | 6.3 |

| Poor physical function | ||||

| No | 3,942 | 91.1 | 3,492 | 86.9 |

| Yes | 369 | 8.5 | 505 | 12.6 |

| Unknown | 18 | 0.4 | 21 | 0.5 |

| Cancer-related pain | ||||

| None, a small amount | 3,916 | 90.5 | 3,564 | 88.7 |

| Moderate, a lot, extreme | 381 | 8.8 | 439 | 10.9 |

| Unknown | 32 | 0.7 | 15 | 0.4 |

| Survivor has cancer treatment summary | ||||

| No | 2,711 | 62.6 | 2,464 | 61.3 |

| Yes | 996 | 23.0 | 1,058 | 26.3 |

| Unknown | 622 | 14.4 | 496 | 12.4 |

| Medical care in last 2 years at cancer center | ||||

| No | 3,827 | 88.4 | 3,483 | 86.7 |

| Yes | 502 | 11.6 | 535 | 13.3 |

| Cancer related visit in last 2 years | ||||

| Yes | 1,170 | 27.0 | 1,244 | 31.0 |

| No | 3,049 | 70.4 | 2,675 | 66.6 |

| Unknown | 110 | 2.6 | 99 | 2.5 |

National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 3) grading = none (0), mild (1), moderate (2), severe (3), life threatening/disabling (4)

Cancer screening in survivors at average risk of developing cervical or breast cancer

The number of female survivors who were not at increased risk for cervical or breast cancer as a result of their prior cancer therapy and had reached the age where screening was recommended in the general population was 3,392 and 209 for Papanicolaou smear and mammography, respectively. Eighty-one percent (2,743/3,392) reported a Papanicolaou smear within the recommended period, and 67.0% (140/209) reported a mammogram within the recommended period (Figure 1, panels a and b). Six percent (200/3,392) and 12.4% (26/209) of survivors reported never having had a Papanicolaou smear or mammogram, respectively. Table 2 displays the univariate and multiple variable logistic regression models predicting adherence to mammography and Papanicolaou smear screening guidelines. The following variables were not statistically significant in the univariate analysis for mammography or Papanicolaou smear adherence and so are not shown in the table: concern about future health, poor physical function, cancer related pain, the survivor having a treatment summary, medical care at a cancer center in the preceding two years or a cancer related visit in the preceding two years. Being “married or living as married” (RR 1.15, 95% CI 1.06-1.24) was associated with an increased likelihood of Papanicolaou smear adherence, while having a high school education or less (RR 0.87, 95% CI 0.77-0.98) or being uninsured (RR 0.85, 95% CI 0.74-0.97) were associated with a decreased likelihood of adherence. No demographic, socioeconomic or health status factors predicted adherence to mammography screening recommendations.

Figure 1.

Adherence to screening guidelines for (A) mammography and (B) Papanicolaou smears by female survivors at average risk of breast or cervical cancer, and to surveillance guidelines for (C) mammography (females only) and (D) colonoscopy (both genders) for survivors at increased risk of breast cancer or colorectal cancer

Table 2.

Predictors of adherence to mammography and Papanicolaou smear guidelines in female survivors at average risk of breast or cervical cancer*

| Mammography (N=209 females; Adherent=140) |

Papanicolaou smear (N=3,392 females; Adherent=2,743) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate** | Univariate | Multivariate** | |||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI | |

| Race | ||||||||

| White (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Non-white | 1.00 | 0.55-1.80 | 0.99 | 0.54-1.81 | 1.02 | 0.91-1.15 | 1.05 | 0.94-1.19 |

| Age at interview, years | ||||||||

| 1.02 | 0.95-1.10 | 1.03 | 0.95-1.11 | 1.00 | 1.00-1.01 | 1.00 | 0.99-1.01 | |

| Marital status | ||||||||

| Single/widowed/divorced or separated (referent) |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Married or living as married | 1.14 | 0.79-1.66 | 1.17 | 1.08-1.26 | 1.15 | 1.06-1.24 | ||

| Education | ||||||||

| Post high school or some college (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| High school or less | 1.06 | 0.64-1.75 | 1.04 | 0.63-1.74 | 0.84 | 0.75-0.95 | 0.87 | 0.77-0.98 |

| College or higher | 1.37 | 0.92-2.02 | 1.37 | 0.92-2.03 | 1.05 | 0.97-1.14 | 1.03 | 0.95-1.12 |

| Insurance status | ||||||||

| US Insured or Canadian (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| US not insured | 0.81 | 0.71-0.92 | 0.85 | 0.74-0.97 | ||||

| Chronic disease status | ||||||||

| Grade 0, 1, 2 (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| Grade 3, 4 | 1.06 | 0.76-1.49 | 0.97 | 0.89-1.05 | ||||

| Poor emotional health | ||||||||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||

| Yes | 0.76 | 0.46-1.26 | 0.93 | 0.81-1.06 | 0.95 | 0.85-1.08 | ||

A relative risk (RR)>1 indicates increased compliance with the recommended screening test; a RR<1 indicates decreased compliance

Univariate analysis was performed and all the variables with p-value less than 0.10 were included in the multivariate model. Independent variable collinearity was evaluated by examining variance inflation factors and tolerance. Variables that were highly correlated were not included in the same models. The multivariate analysis of mammogram and Papanicolaou smear are adjusted for race, age at questionnaire and age at diagnosis.

Cancer surveillance in survivors at high-risk for breast, colorectal or skin cancer

Among female survivors at increased risk for developing breast cancer and survivors of both genders at increased risk for developing colorectal cancer who required surveillance according to the COG LTFU Guidelines, only 241/522 (46.2%) and 91/794 (11.5%) reported undergoing a mammogram or colonoscopy within the recommended period (Figure 1, panels c and d). Only 1,290/4,850 (26.6%) survivors at increased risk for skin cancer reported ever having a complete examination of all irradiated areas. Table 3 displays the univariate and multiple variable logistic regression models predicting adherence to mammography, colonoscopy and skin examination surveillance guidelines. Older age at interview (RR 1.08, 95% CI 1.05-1.11) was associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a mammogram. Older age at interview (RR 1.07, 95% CI 1.02-1.12), the survivor having a copy of their cancer treatment summary (RR 1.66, 95% CI 1.06-2.61) and a medical visit related to their prior cancer within the preceding two years (RR 2.77, 95% CI 1.69-4.52) were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a colonoscopy. Having a college education or higher (RR 1.24, 95% CI 1.08-1.42), medical care at a cancer center within the preceding two years (RR 1.43, 95% CI 1.21-1.68), and the survivor having a copy of the cancer treatment summary (RR 1.31, 95% CI 1.15-1.49) were associated with an increased likelihood of reporting a skin exam. Survivors that were non-white (RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.52-0.86), had moderate to extreme cancer-related pain (RR 0.77, 95% CI 0.62-0.95), or who had not had a medical visit related to their prior cancer within the preceding two years (RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.73-0.96) were less likely to report a skin exam.

Table 3.

Predctors of adherence to mammography, colonoscopy and skin exam guidelines in survivors at high risk of breast, colorectal or skin cancer*

| Mammography (N=522 females; Adherent=241) |

Colonoscopy (N=794 males and females; Adherent=91) |

Skin exam (N=4,850 males and females; Adherent=1,290) |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate** | Univariate | Multivariate** | Univariate | Multivariate** | |||||||

| RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI |

RR | 95% CI |

RR | 95% CI | RR | 95% CI |

RR | 95% CI | |

| Sex | ||||||||||||

| Female (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0.65- | 0.51- | 1.02- | ||||||||||

| Male | N/A | 1.00 | 1.56 | 0.79 | 1.23 | 1.14 | 1.27 | 1.08 | 0.97-1.22 | |||

| Race | ||||||||||||

| White (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0.81- | 0.63- | 0.78- | 0.55- | |||||||||

| Non-white | 1.12 | 0.73-1.72 | 1.29 | 2.04 | 1.25 | 2.46 | 1.48 | 2.80 | 0.68 | 0.84 | 0.67 | 0.52-0.86 |

| Age at interview, years | ||||||||||||

| 1.05- | 1.03- | 1.02- | 1.00- | |||||||||

| 1.08 | 1.06-1.10 | 1.08 | 1.11 | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.07 | 1.12 | 1.01 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 1.00-1.03 | |

| Marital status | ||||||||||||

| Single/widowed/divorced or separated (referent) |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0.92- | 0.72- | 0.98- | ||||||||||

| Married or living as married | 1.63 | 1.23-2.16 | 1.24 | 1.66 | 1.12 | 1.74 | 1.09 | 1.22 | ||||

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Post high school or some college (referent) |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 0.48- | 0.53- | 0.75- | ||||||||||

| High school or less | 0.70 | 0.46-1.07 | 0.75 | 1.15 | 1.00 | 1.90 | 0.88 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 0.77-1.12 | ||

| 0.73- | 0.64- | 1.13- | ||||||||||

| College or higher | 1.00 | 0.76-1.33 | 0.98 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 1.71 | 1.28 | 1.45 | 1.24 | 1.08-1.42 | ||

| Insurance status | ||||||||||||

| US Insured or Canadian (referent) |

1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 0.47- | 0.47- | 0.56- | ||||||||||

| US not insured | 0.63 | 0.35-1.16 | 0.88 | 1.64 | 0.97 | 2.01 | 0.67 | 0.82 | 0.85 | 0.69-1.06 | ||

|

Concern about future health

(Expect worse) | ||||||||||||

| False (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1.13- | 0.72- | 1.02- | ||||||||||

| True | 1.18 | 0.89-1.57 | 1.78 | 2.80 | 1.15 | 1.83 | 1.15 | 1.30 | 1.07 | 0.92-1.23 | ||

| Chronic disease status | ||||||||||||

| Grade 0, 1, 2 (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1.04- | 0.82- | 0.96- | ||||||||||

| Grade 3, 4 | 1.10 | 0.85-1.44 | 1.63 | 2.55 | 1.28 | 2.01 | 1.09 | 1.24 | ||||

| Poor emotional health | ||||||||||||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1.07- | 0.91- | 0.72- | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.91 | 0.60-1.38 | 1.15 | 1.24 | 1.63 | 2.92 | 0.88 | 1.08 | ||||

| Poor physical function | ||||||||||||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 1.01- | 0.53- | 0.75- | ||||||||||

| Yes | 0.83 | 0.56-1.23 | 1.07 | 1.14 | 0.95 | 1.69 | 0.90 | 1.08 | ||||

| Cancer-related pain | ||||||||||||

| None, a small amount (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 0.79- | 0.70- | 0.62- | ||||||||||

| Moderate, a lot, extreme | 0.79 | 0.51-1.22 | 1.40 | 2.48 | 0.85 | 1.03 | 0.77 | 0.95 | ||||

|

Survivor has cancer treatment

summary | ||||||||||||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||||||

| 1.15- | 1.06- | 1.25- | 1.15- | |||||||||

| Yes | 1.04 | 0.78-1.38 | 1.84 | 2.94 | 1.66 | 2.61 | 1.40 | 1.57 | 1.31 | 1.49 | ||

|

Medical care in last 2 years at cancer

center | ||||||||||||

| No (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0.97- | 0.98- | 0.63- | 1.43- | 1.21- | ||||||||

| Yes | 1.51 | 1.12-2.02 | 1.35 | 1.87 | 1.68 | 2.88 | 1.08 | 1.84 | 1.64 | 1.87 | 1.43 | 1.68 |

| Cancer related visit in last 2 years | ||||||||||||

| Yes (referent) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||||

| 0.60- | 0.21- | 0.22- | 0.63- | 0.73- | ||||||||

| No | 0.72 | 0.56-0.93 | 0.79 | 1.05 | 0.33 | 0.53 | 0.37 | 0.62 | 0.70 | 0.78 | 0.84 | 0.96 |

Arelative risks (RR)>1 indicates increased compliance with the recommended surveillance test; a RR<1 indicates decreased compliance

Univariate analysis was performed and all the variables with p-value less than 0.10 were included in the multivariate model. Independent variable collinearity was evaluated by examining variance inflation factors and tolerance. Variables that were highly correlated were not included in the same models. The multivariate analysis of colonoscopy and skin exam is adjusted for sex, race, age at questionnaire and age at diagnosis. The multivariate analysis of mammography (which is restricted to females) is adjusted for race, age at questionnaire and age at diagnosis.

DISCUSSION

We assessed the cancer screening and surveillance practices of 8,347 survivors of childhood cancer. Encouragingly, female survivors considered average risk for developing cervical or breast cancer demonstrated acceptable rates of adherence to Papanicolaou smear and mammography recommendations, with adherence rates of 81% and 67% for each test, respectively. This suggests that female childhood cancer survivors are generally health conscious and aware of screening guidelines published for the general population. Survivors of cancer in adulthood have been demonstrated to have better adherence to cancer screening recommendations than that observed in the general population (41), although actual screening rates are quite variable and often sub-optimal.

Despite the relatively high screening rates for survivors at average risk for another cancer, the rates of cancer surveillance for those at high risk for a therapy-related second malignant neoplasm were alarmingly low. Less than half of the survivors at increased risk of breast, colorectal or skin cancer reported compliance with recommended surveillance. Females who have received radiation therapy to the chest during childhood demonstrate a 13% to 20% cumulative incidence of breast cancer by 40 to 45 years of age (42), a risk similar to that observed in women with breast cancer susceptibility gene mutations (43-45). Several studies have recognized an emerging risk of colorectal cancer in patients who have received abdominal or pelvic radiation as part of their primary therapy, with a 3.9 to 4.7- fold increased risk when compared to the general population (13, 14, 46). Increased rates of other gastrointestinal malignancies such as gastric cancer have also been observed, suggesting that clinicians need to be aware of new symptoms in survivors who have received radiation to any portion of their gastrointestinal tract. Malignant melanoma occurs with increased frequency in childhood cancer survivors (5, 14, 15), and the cumulative incidence of non-melanoma skin cancer is almost 7% in 30-year survivors of childhood cancer (2). Thus, the low surveillance rates observed in our cohort suggest that opportunities to detect secondary breast, colorectal or skin cancers early in their course are being missed, placing some survivors at increased risk for both serious morbidity and mortality.

The dichotomy of low rates of surveillance among the high risk survivors within the setting of high rates of cancer screening among average risk survivors suggests that the problem is not simply a lack of interest or compliance on the part of the survivors. Survivors were more likely to report an indicated mammogram or skin exam if they received their follow-up care at a cancer center or in a long-term follow-up program. However, only a minority of adult survivors (12.4% in this cohort) continues to receive regular care at a cancer center once they reach adulthood (47). Although many pediatric cancer centers offer specialized care to survivors during childhood and adolescence, few provide access to specialized clinics once survivors reach adulthood (48). Several adult cancer centers run survivorship clinics although these generally target survivors of adult malignancies such as breast or colon cancer, and are not routinely used by survivors of childhood cancer (49, 50). These data suggest that interventions to improve adherence to cancer surveillance should be directed at the primary care physicians who care for the majority of long-term childhood cancer survivors, as well as to the survivors themselves. Prior research has suggested that a physician recommendation is a statistically significant determinant of adherence to mammography guidelines (51). However, since the guidelines for high risk patients recommend that breast and colorectal cancer surveillance commence many years before screening in the general population, many primary care physicians are likely unaware of the surveillance guidelines for these high risk patients (52). In fact, primary care physicians’ lack of familiarity with the health problems faced by survivors has been identified as a substantial barrier to their provision of adequate survivor care (52, 53). Targeted education of physicians, open access to guidelines (such as the COG LTFU Guidelines available at www.survivorshipguidelines.org) and the availability of the pediatric cancer centers as a resource for primary care providers may improve survivor care. Perhaps most importantly, survivors must be provided with the knowledge and tools to advocate for their own care. Survivors are often unaware of the details of their cancer therapy, preventing them from seeking care focused on specific risks (54). Efforts to empower survivors have included provision of treatment summaries and survivor care plans at the conclusion of cancer therapy. Indeed, in the present study, survivors who had a summary of their cancer treatment were more likely to report a recommended colonoscopy or skin exam. The feasibility of providing survivors with a portable electronic record of their cancer history and recommended care that can be shared with their health care provider is being assessed currently.

Several methodological limitations must be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, we relied on self report data about the completion of screening tests. Although self report of imaging or diagnostic tests such as mammography or Papanicolaou smear has been demonstrated to be generally reliable (55), there is no evidence to suggest that patients accurately report skin exams. Second, CCSS participants are a select group of survivors, and their compliance with surveillance recommendations may not be representative of all childhood cancer survivors. Third, this cohort of survivors received their therapy between 1970 and 1986. Caution should be exercised in generalizing these findings to patients treated more recently. It is plausible that patients treated in the current era are better informed about their need for routine surveillance. The CCSS is currently recruiting a cohort of survivors treated between 1987 and 1999 to examine such questions. Finally, assessment of screening compliance among survivors at average risk of developing a second malignant neoplasm focused only on females. There were too few survivors who had reached the age where colorectal cancer screening is recommended to assess compliance with these screening guidelines. Thus, the findings of good compliance among female survivors should not be generalized to male survivors.

In summary, survivors of childhood cancer who are not considered to be at increased risk for developing a second malignant neoplasm demonstrate reasonable adherence to Papanicolaou smear and mammography guidelines. However, survivors at increased risk for developing a new cancer during adulthood demonstrate very poor adherence to recommended surveillance for breast, colorectal and skin cancer. Clinicians who care for survivors of childhood cancers must implement and evaluate methods for ensuring better adherence with recommended cancer surveillance and for improving awareness among both the survivors and the primary care clinicians who provide care for the majority of these survivors as they age. This should include provision of a treatment summary and care plan to all childhood cancer survivors prior to their transition out of a pediatric cancer center.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS) is a collaborative, multi-institutional project, funded as a resource by the National Cancer Institute, of individuals who survived five or more years after diagnosis of childhood cancer. CCSS is a retrospectively ascertained cohort of 20,626 childhood cancer survivors diagnosed before age 21 between 1970 and 1986, and 3,899 siblings of survivors who serve as a control group. The cohort was assembled through the efforts of 26 participating clinical research centers in the United States and Canada. The study is currently funded by a U24 resource grant (NCI grant # U24 CA55727, Principal Investigator: LL Robison) awarded to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Currently, we are in the process of expanding the cohort to include an additional 14,000 childhood cancer survivors diagnosed before age 21 between 1987 and 1999. For information on how to access and utilize the CCSS resource, visit http://ccss.stjude.org.

Primary Funding Source: Grant No. U24-CA-55727 (L.L. Robison, principal investigator) from the National Cancer Institute, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC.)

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

This work was supported by Grant No. U24-CA-55727 (L.L. Robison, principal investigator) from the National Cancer Institute, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC). The funding sources had no role in the design, conduct, analysis, interpretation or presentation of the data, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Appendix 1

CCSS participants eligible for study of screening and surveillance practices

Appendix 2

Recommended screening (USPSTF) (32) and surveillance (COG) (23) for survivors at average or high risk of developing a second malignant neoplasm

| Screening in survivors at AVERAGE risk of a second malignant neoplasm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Cervix | Colorectal | Skin | |

| USPSTF recommended screening for the general (average risk) population |

Mammogram every 1 to 2 years for women aged 40 years or older |

Papanicolaou smear every 3 years commencing at age 21 years* |

** | Not applicable |

| Surveillance in survivors at HIGH risk of a second malignant neoplasm | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast | Cervix | Colorectal | Skin | |

| Definition (COG) of high risk group |

Female, ≥20 Gy radiation therapy to the chest |

Not applicable | ≥30 Gy radiation therapy to the abdomen, pelvis or spine |

Any radiation therapy |

| COG recommended surveillance for survivors at high risk |

Annual mammogram beginning 8 years after radiation or age 25 years, whichever occurs last*** |

Not applicable | Colonoscopy every 5 years beginning at age 35 years |

Annual dermatologic exam of irradiated areas |

Guideline recommends Papanicolaou smear screening to start at time of first sexual intercourse or age 21 years, whichever is earlier (http://www.ahrq.gov/clinic/3rduspstf/cervcan/cervcanrr.htm). Since time of first intercourse was not captured by the study questionnaire, we used age 21 years as the expected time of the commencement of screening.

Since few survivors in the cohort have reached the age at which colorectal cancer screening in the general population is recommended, this outcome is not presented in this analysis

Breast MRI was identified as an adjunct to mammography in a revised version of the COG surveillance guidelines published in 2008 after the completion of the study surveys.

MRI is not assessed in this analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mariotto AB, Rowland JH, Yabroff KR, Scoppa S, Hachey M, Ries L, et al. Long-term survivors of childhood cancers in the United States. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(4):1033–40. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Meadows AT, Friedman DL, Neglia JP, Mertens AC, Donaldson SS, Stovall M, et al. Second Neoplasms in Survivors of Childhood Cancer: Findings From the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study Cohort. J Clin Oncol. 2009;7(14):2356–62. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jenkinson HC, Hawkins MM, Stiller CA, Winter DL, Marsden HB, Stevens MC. Long-term population-based risks of second malignant neoplasms after childhood cancer in Britain. Br J Cancer. 2004;91(11):1905–10. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhatia S, Yasui Y, Robison LL, Birch JM, Bogue MK, Diller L, et al. High risk of subsequent neoplasms continues with extended follow-up of childhood Hodgkin’s disease: report from the Late Effects Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(23):4386–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.11.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olsen JH, Moller T, Anderson H, Langmark F, Sankila R, Tryggvadottir L, et al. Lifelong cancer incidence in 47,697 patients treated for childhood cancer in the Nordic countries. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101(11):806–13. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstrong GT, Liu Q, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, Leisenring W, Robison LL, et al. Late Mortality Among 5-Year Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Summary From The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2328–38. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lawless SC, Verma P, Green DM, Mahoney MC. Mortality experiences among 15+ year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48(3):333–8. doi: 10.1002/pbc.20723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanna G, Lorizzo K, Rotmensz N, Bagnardi V, Cinieri S, Colleoni M, et al. Breast cancer in Hodgkin’s disease and non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors. Ann Oncol. 2007;18(2):288–92. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kenney LB, Yasui Y, Inskip PD, Hammond S, Neglia JP, Mertens AC, et al. Breast cancer after childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(8):590–7. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Horwich A, Swerdlow AJ. Second primary breast cancer after Hodgkin’s disease. Br J Cancer. 2004;90(2):294–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ng AK, Bernardo MV, Weller E, Backstrand K, Silver B, Marcus KC, et al. Second malignancy after Hodgkin disease treated with radiation therapy with or without chemotherapy: long-term risks and risk factors. Blood. 2002;100(6):1989–96. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-02-0634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Metayer C, Lynch CF, Clarke EA, Glimelius B, Storm H, Pukkala E, et al. Second cancers among long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease diagnosed in childhood and adolescence. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(12):2435–43. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.12.2435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgson DC, Gilbert ES, Dores GM, Schonfeld SJ, Lynch CF, Storm H, et al. Long-term solid cancer risk among 5-year survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(12):1489–97. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inskip PD, Curtis RE. New malignancies following childhood cancer in the United States, 1973-2002. Int J Cancer. 2007;121(10):2233–40. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neglia JP, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, Mertens AC, Hammond S, Stovall M, et al. Second malignant neoplasms in five-year survivors of childhood cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(8):618–29. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.8.618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perkins JL, Liu Y, Mitby PA, Neglia JP, Hammond S, Stovall M, et al. Nonmelanoma skin cancer in survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(16):3733–41. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu WL, Jansen L, Post WJ, Bonnema J, Van de Velde JC, De Bock GH. Impact on survival of early detection of isolated breast recurrences after the primary treatment for breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2009;114(3):403–12. doi: 10.1007/s10549-008-0023-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moss SM, Ellman R, Coleman D, Chamberlain J, United Kingdom Trial of Early Detection of Breast Cancer Group Survival of patients with breast cancer diagnosed in the United Kingdom trial of early detection of breast cancer. J Med Screen. 1994;1(3):193–8. doi: 10.1177/096914139400100312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levin B, Lieberman DA, McFarland B, Smith RA, Brooks D, Andrews KS, et al. Screening and surveillance for the early detection of colorectal cancer and adenomatous polyps, 2008: a joint guideline from the American Cancer Society, the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer, and the American College of Radiology. CA Cancer J Clin. 2008;58(3):130–60. doi: 10.3322/CA.2007.0018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolff T, Tai E, Miller T. Screening for skin cancer: an update of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):194–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Saslow D, Boetes C, Burke W, Harms S, Leach MO, Lehman CD, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast screening with MRI as an adjunct to mammography. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57(2):75–89. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.2.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maurice A, Evans DG, Shenton A, Ashcroft L, Baildam A, Barr L, et al. Screening younger women with a family history of breast cancer--does early detection improve outcome? Eur J Cancer. 2006;42(10):1385–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines for Survivors of Childhood, Adolescent, and Young Adult Cancers. http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org.

- 24.Landier W, Bhatia S, Eshelman DA, Forte KJ, Sweeney T, Hester AL, et al. Development of risk-based guidelines for pediatric cancer survivors: the Children’s Oncology Group Long-Term Follow-Up Guidelines from the Children’s Oncology Group Late Effects Committee and Nursing Discipline. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(24):4979–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scottish Collegiate Guidelines Network Long term follow up of survivors of childhood cancer: A national clinical guideline. http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign76.pdf.

- 26.United Kingdom Children’s Cancer Study Group: Therapy-based long-term follow-up: Practice Statement. http://www.cclg.org.uk/library/19/PracticeStatement/LTFU-full.pdf.

- 27.Kremer L, Jaspers M, van Leeuwen F, Versluys B, Bresters D, Bokkerink J. Landelijke richtlijnen voor follow-up van overlevenden van kinderkanker. Tijdschrift voor kindergeneeskunde (Dutch Journal of Pediatrics) 2006;6:214–8. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol. 2002;38(4):229–39. doi: 10.1002/mpo.1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robison LL, Armstrong GT, Boice JD, Chow EJ, Davies SM, Donaldson SS, et al. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study: A National Cancer Institute-Supported Resource for Outcome and Intervention Research. J Clin Oncol. 2009;7(14):2308–18. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, Stovall MA, Neglia JP, Lanctot JQ, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2319–27. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.21.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mertens AC, Walls RS, Taylor L, Mitby PA, Whitton J, Inskip PD, et al. Characteristics of childhood cancer survivors predicted their successful tracing. J Clin Epidemiol. 2004;57(9):933–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2004.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.United States Preventive Services Task Force Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. http://www.ahrq.gov/CLINIC/uspstfix.htm.

- 33.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics National Health Interview Survey 2003 NHIS Datasets. http://www.cdc.gov/Nchs/nhis/quest_data_related_1997_forward.htm.

- 34.The Workshop Group Reducing deaths from breast cancer in Canada. CMAJ. 1989;141(3):199–201. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, Kawashima T, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(15):1572–82. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa060185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Hobbie W, Chen H, Gurney JG, et al. Health status of adult long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. JAMA. 2003;290(12):1583–92. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Derogatis LR. BSI-18 Administration, Scoring and Procedures Manual. National Computer Systems; Minneapolis, MN: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware JE, Jr., Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36). I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McNutt LA, Wu C, Xue X, Hafner JP. Estimating the relative risk in cohort studies and clinical trials of common outcomes. Am J Epidemiol. 2003;157(10):940–3. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Allison PD. Logistic Regression Using the SAS System: Theory and A. SAS Press; Cary, NC: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trask PC, Rabin C, Rogers ML, Whiteley J, Nash J, Frierson G, et al. Cancer screening practices among cancer survivors. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(4):351–6. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Henderson TO, Amsterdam A, Bhatia S, Hudson MM, Meadows AT, Neglia JP, et al. Systematic review: surveillance for breast cancer in women treated with chest radiation for childhood, adolescent, or young adult cancer. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(7):444–55. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-7-201004060-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ford D, Easton DF, Stratton M, Narod S, Goldgar D, Devilee P, et al. The Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Genetic heterogeneity and penetrance analysis of the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes in breast cancer families. Am J Hum Genet. 1998;62(3):676–89. doi: 10.1086/301749. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Easton DF, Ford D, Bishop DT, Breast Cancer Linkage Consortium Breast and ovarian cancer incidence in BRCA1-mutation carriers. Am J Hum Genet. 1995;56(1):265–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Begg CB, Haile RW, Borg A, Malone KE, Concannon P, Thomas DC, et al. Variation of breast cancer risk among BRCA1/2 carriers. Jama. 2008;299(2):194–201. doi: 10.1001/jama.2007.55-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dores GM, Metayer C, Curtis RE, Lynch CF, Clarke EA, Glimelius B, et al. Second malignant neoplasms among long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: a population-based evaluation over 25 years. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(16):3484–94. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Mahoney MC, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(27):4401–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.16.9607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hewitt M, Weiner SL, Simone JV, editors. Childhood Cancer Survivorship: Improving Care and Quality of Life. The National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E, editors. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Oeffinger KC, McCabe MS. Models for delivering survivorship care. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(32):5117–24. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.0474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Oeffinger KC, Ford JS, Moskowitz CS, Diller LR, Hudson MM, Chou JF, et al. Breast cancer surveillance practices among women previously treated with chest radiation for a childhood cancer. JAMA. 2009;301(4):404–14. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zebrack BJ, Eshelman DA, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM, et al. Health care for childhood cancer survivors: insights and perspectives from a Delphi panel of young adult survivors of childhood cancer. Cancer. 2004;100(4):843–50. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mertens AC, Cotter KL, Foster BM, Zebrack BJ, Hudson MM, Eshelman D, et al. Improving health care for adult survivors of childhood cancer: recommendations from a delphi panel of health policy experts. Health Policy. 2004;69(2):169–78. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, Neglia JP, Yasui Y, Hayashi R, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Jama. 2002;287(14):1832–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.14.1832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Caplan LS, McQueen DV, Qualters JR, Leff M, Garrett C, Calonge N. Validity of women’s self-reports of cancer screening test utilization in a managed care population. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2003;12(11 Pt 1):1182–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]