Abstract

In an effort to expand the stereochemical and structural complexity of chemical libraries used in drug discovery, the Center for Chemical Methodology and Library Development at Boston University has established an infrastructure to translate methodologies accessing diverse chemotypes into arrayed libraries for biological evaluation. In a collaborative effort, the NIH Chemical Genomics Center determined IC50’s for Plasmodium falciparum viability for each of 2,070 members of the CMLD-BU compound collection using quantitative high-throughput screening across five parasite lines of distinct geographic origin. Three compound classes displaying either differential or comprehensive antimalarial activity across the lines were identified, and the nascent structure activity relationships (SAR) from this experiment used to initiate optimization of these chemotypes for further development.

Keywords: chemical biology, organocatalytic, polycyclic ketal

The synthesis of compound libraries embodying structural diversity and complexity is one potential avenue to enabling the discovery of potent and selective bioactive agents (1–3). Synthetic methodology aimed at library design and distribution is the focus of the Center for Chemical Methodology and Library Development at Boston University (CMLD-BU). Currently the CMLD-BU maintains a collection of approximately 2,500 compounds derived from reaction methodologies developed in the Center and associated groups. The CMLD-BU has developed a workflow that leverages focused methodology development (4) and identification of new scaffolds and chemical reactions utilizing multidimensional reaction screening (5) for the synthesis of libraries.

In a collaboration between the CMLD-BU and the NIH Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), an effort to discover unique chemotypes which inhibit the viability of P. falciparum, the causative agent of malaria, is underway. Malaria not only inflicts tremendous suffering and morbidity on the human population, but has dramatically influenced the course of civilization with profound sociological and economic implications (6). In response, there have been significant screening efforts for new antimalarial agents (7, 8). Effective treatments continue to be needed in part due to acquired resistance of P. falciparum. Identification of molecular targets affecting the viability of malaria is necessary for efficient drug development as is the discovery of chemotypes active across a variety of geographic isolates. With an aim to improve the process of identifying new compounds and targets, we have used quantitative high-throughput screening (qHTS) to achieve pharmacological fingerprints of chemical libraries (9). This technique tests each compound as a seven point titration covering four orders of magnitude in concentration thus allowing sufficient resolving power by virtue of IC50 determinations to reveal subtle differences in compound activities between parasite lines. A compound with a differential chemical phenotype (DCP) can enable mapping of target genes using genetic recombination wherein the DCP emerges between two or more lines which represent the parental parasites of a genetic cross (10). Additionally, qHTS reveals nascent SAR supporting identification of low to moderately active chemotypes to maximally leverage the library. Herein, we report the initial results employing this technique to characterize the antimalarial activity of a CMLD-BU compound library and the activities identified from three distinct chemical series.

Results and Discussion

CMLD-BU Compound Collection.

In 2009, the CMLD-BU library consisted of 2,070 unique chemical structures which were derived from approximately 18 synthesized libraries and 10 diversity collections. To categorize the CMLD-BU compound collection, we evaluated the complexity as defined by stereogenenic carbon content and sp3/sp2 character (11). In this regard, we also compared our collection to the NIH Molecular Libraries Small-Molecule Repository (MLSMR). The analysis revealed a significant difference in overall complexity as defined by the ratio of stereogenic carbons to total carbons as well as total stereogenic carbon count. For instance, the CMLD-BU compounds have an average ratio of stereogenic carbons of about 0.1, while analysis of the MLSMR indicates an average of approximately 0.02. Likewise, the average number of steoreogenic carbons per molecule in the CMLD-BU collection is 2.8, while the average number in the MLSMR is 0.4.

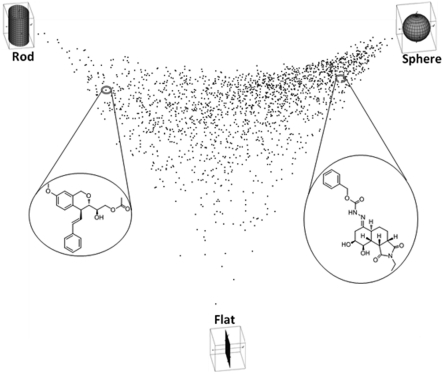

Another method for structural characterization of the CMLD-BU compound collection is based on an approach introduced by Sauer and Schwarz utilizing principle moments of inertia to describe the overall three-dimensional shape of molecules (12). More recently, efforts by Clemons and Schreiber have shown this method to be useful for description and comparison of compound collections (13). A similar analysis of the CMLD-BU compound collection shows that the overall shape is heavily “spherical” in nature with significant degree of “rod-like” character (Fig. 1). Overall, the CMLD-BU collection does not have a significant representation of “flat” compounds, correlating with a high sp3 content within the collection. This shape distribution distinguishes the CMLD-BU collection from those typically found in industry or commercial collections (14).

Fig. 1.

Principle moments of inertia analysis of the CMLD-BU compound collection.

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening for Inhibitors of P. falciparum Proliferation.

Utilizing a SYBR green I dye DNA staining assay (15) to measure proliferation of P. falciparum in human erythrocytes, we conducted qHTS across five geographically distinct clonal lines of the parasite (CP250, Dd2, HB3, 7G8 and GB4) utilizing the CMLD-BU small-molecule library (2,070 compounds). We selected these five lines to include two sets of parents of two genetic crosses (Dd2xHB3, and 7G8xGB4) for which we have progeny available to permit genetic mapping of the chromosomal locus controlling the differential activity (10). The CP250 line from Cambodia was included to identify compounds active on a multidrug resistant strain (16).

Initially, each compound was tested in qHTS format at seven fivefold interplate dilutions beginning at 5.7 μM. The assay as measured by standard methods displayed acceptable performance for each parasite line (Z′ factor ≥0.7 and a S∶B ratio ≥6). Two control inhibitors, artemisinin and mefloquine, were present on every plate as full intraplate titrations and exhibited the expected IC50 values (see SI Appendix, Table S1). The compound library was also counterscreened for color interference to eliminate positives that might have resulted from light absorbance interference-based artifacts (see SI Appendix, Fig. S1). Data from this screen was deposited into PubChem (Summary AID = 504350 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound) and are summarized in SI Appendix, Table S2.

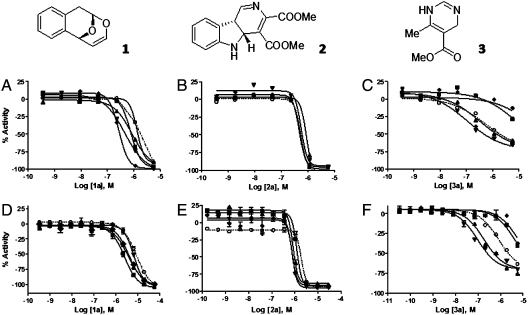

Primary screening results identified three chemotypes (1–3) which inhibited proliferation either nonselectively (1 and 2) or differentially (3), having completely fit concentration-response curves (CRCs) displaying full efficacy (curve class 1a), or partially complete CRCs (class 2a) (9). To further validate activities, compounds were retested in an intraplate titration format using twelve-point, threefold dilutions of the compounds to obtain more accurate IC50 values (Fig. 2; SI Appendix, Table S5) (vide infra). These compounds were then counterscreened in an erythrocyte viability assay to rule out the possibility that positive activity resulted from erythrocyte toxicity rather than parasite death. The results confirmed that all the identified positives (compounds associated with curve classes 1a, 1b, and 2a) inhibited parasite growth. Little or no erythrocyte toxicity and/or color interference was observed (see SI Appendix, Table S5, Fig. S1).

Fig. 2.

Active series from the CMLD-BU compound collection vs. ability to inhibit the viability of five geographic P. falciparum lines. Scaffolds of active series, polycyclic ketal (1), indoline alkaloid (2), and dihydropyrimidinone (3), and activity of representative compound as identified in qHTS (A–C) and follow-up confirmation (D–F). Plots show the compound potency against five geographic P. falciparum lines (square, 7G8; up triangle, Dd2; down triangle GB4; diamond, HB3; CP250 open circle) as determined in the SYBR Green-based viability assay in qHTS (A–C) and in a 12-point follow-up titration (D–F).

Identification of Nonselective Chemotypes.

Among the 2,070 compounds tested, several associated with curve classes 1a-2a (SI Appendix, Table S2) were found to be pan-active with IC50 values less than 2 μM across all the five parasite lines. In addition, these compounds also showed no significant effect on the viability of HepG2 and HEK293 cells at concentrations effective (IC50) in inhibiting P. falciparum viability (SI Appendix, Table S5). Structural analysis revealed that these pan-active compounds were derived from polycyclic ketal and indoline alkaloid chemotypes (1 and 2, Fig. 2).

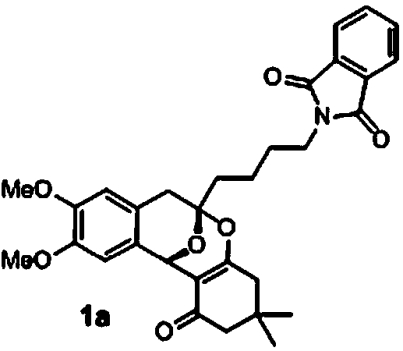

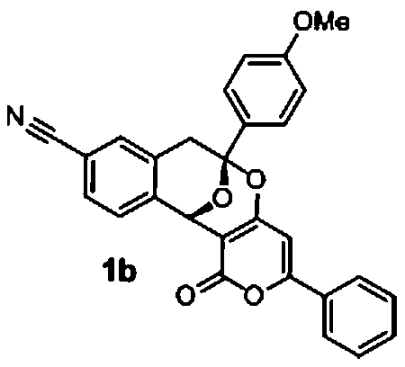

Polycyclic ketals.

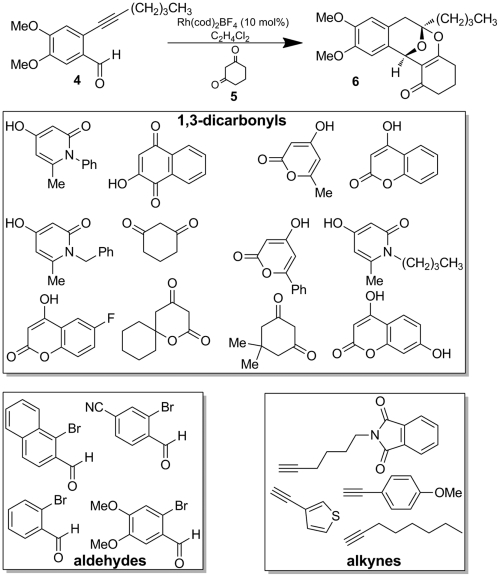

We have described the synthesis of polycyclic ketals which were discovered through the process of multidimensional reaction screening (5). The polycyclic ketal core 6 is derived from cycloisomerization/annulation of o-alkynyl benzaldehydes (4) and 1,3-dicarbonyls such as 1,3-cyclohexanedione 5 in the presence of a cationic rhodium (I) catalyst (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

General cycloisomerization/annulation route to polycyclic ketals and polycyclic ketal library building blocks.

Upon discovery of this polycyclization reaction, we explored the scope and limitations regarding the dicarbonyl component. We chose a series of 24 1,3-dicarbonyl reaction partners which were reacted with alkynyl benzaldehyde 4. Each reaction was carried out under optimized reaction conditions (10 mol% Rh(cod)2BF4, C6H5Cl, 80 °C, 4 h). Overall, a broad scope of 1,3-dicarbonyl substrates participated in the polycyclic ketal formation affording moderate to good yields rendering the methodology ideal for library synthesis.

We next designed an array of 192 polycyclic ketals using sixteen alkynyl benzaldehydes (derived from cross coupling of four ortho-bromo benzaldehydes and four terminal alkynes) and twelve 1,3-dicarbonyls as building blocks (Fig. 3). Library synthesis was conducted under optimized conditions (10 mol% Rh(cod)2BF4, C6H5Cl, 80 °C, 12 h) on a 4 mmol scale. Products were isolated by mass-directed, preparative high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). Sixty reactions had an isolated yield of 70% or greater and fifty reactions had isolated yields of 10–70%. The remaining reactions did not afford isolatable products. Purities of the isolated compounds were generally high (> 90%) as measured by HPLC analysis. Library members which were isolated and maintained high purity (90 compounds) were included in the collection of 2,070 compounds tested for biological activity.

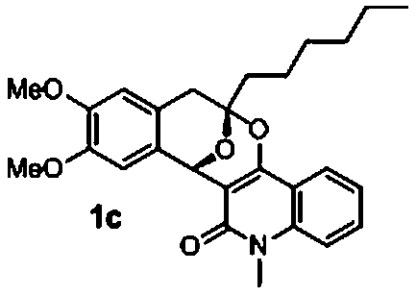

Activity profiling of the screened polycyclic ketal library members revealed a number of active compounds ranging from very low to moderate activity. Validation of the most active compounds (1a and 1b) afforded good dose-response curves although with reduced potency in comparison to the primary screen (Table 1). We synthesized a number of analogs with variation of the alkyne derived substitution and 1,3-dicarbonyl. Among these derivatives, we identified compound 1c as the most active. Compounds 1a and 1c were not cytotoxic to HepG2, HEK293, and red blood cells (SI Appendix, Table S5). Although these polycyclic ketals have low μM activity against the five lines, they represent a unique class of potential antimalarial chemotypes. We are currently synthesizing analogs in an attempt to explore additional SAR and increase antimalarial potency.

Table 1.

Active polycyclic ketals

| Structure | 7G8 GB4 | HB3 Dd2 | CP250 |

|

2.5 μM (0.6, n = 2) 6.5 μM (0, n = 2) | 3.8 μM (0.6, n = 4) 4.0 μM (0.2, n = 4) | 8.7 μM (0.7, n = 2) |

|

1.7 μM (0.1, n = 2) 1.3 μM (0.1, n = 2) | 2.9 μM (0.9, n = 2) 9.0 μM (1.5, n = 2) | na |

|

1.0 μM (0.2, n = 2) 4.2 μM (0.4, n = 2) | 2.5 μM (0, n = 2) 1.9 μM (0.5, n = 2) | 6 μM (0.5, n = 2) |

Results are reported as effective concentration values needed to inhibit parasite growth at 50% (IC50) in μM. Standard deviation and number of replicates are reported in parentheses. Replicate numbers > 2 represent assays carried out under identical conditions on different days. Compounds were retested in an intraplate titration format using twelve-point, threefold dilutions.

Indoline alkaloids.

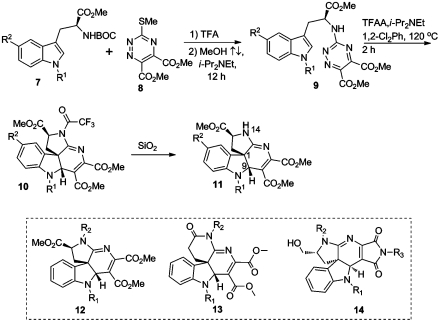

Indoline alkaloid scaffolds are derived from intramolecular inverse-demand Diels-Alder cycloaddition of tryptophan derivatives tethered to triazines (Fig. 4) (17). The underlying approach is representative of a methodology focused on the synthesis of scaffolds which resemble Aspidosperma alkaloid (18) natural products. Libraries based on three scaffolds were synthesized using a general synthetic approach. A representative scaffold synthesis begins with Boc-protected tryptophan (7). Deprotection and subsequent nucleophilic aromatic substitution of triazine 8 afforded the inverse-demand Diels-Alder precursor 9. In situ acylation [lowering the triazine lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO)] and thermolysis promoted cycloaddition with loss of nitrogen to afford the protected indoline alkaloid scaffold 10 which could be readily deprotected to scaffold 11. A library of 199 related indoline alkaloids derived from scaffold 12–14 were synthesized via N14 diversification employing acyl and sulfonyl chlorides (19).

Fig. 4.

General route to indoline alkaloid scaffolds.

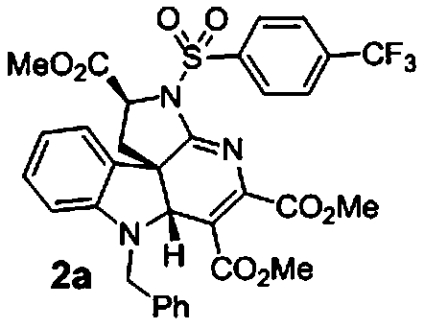

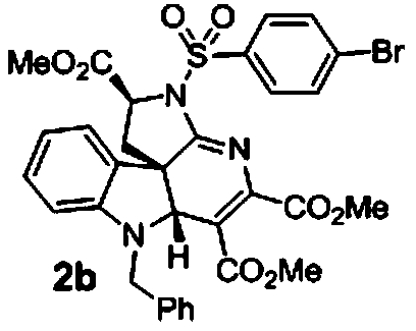

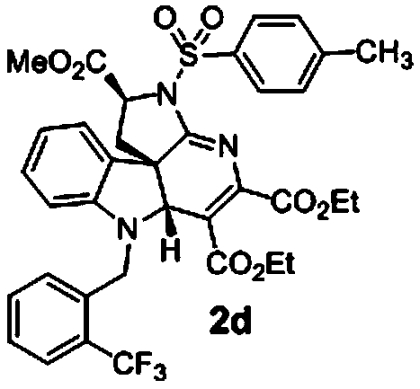

Of the 199 indoline alkaloid scaffolds present in the library, a number of weakly active compounds clustered to scaffold 12. Compounds 2a and 2b (Table 2) were found to be the most active against all five lines. Initial SAR indicates that the activity appears to be particular to structures having an aryl sulfonamide substitution at N14 and benzyl substitution at the indole nitrogen. Validation of compounds 2a and 2b recapitulated the preliminary observation of dose-response curves with steep Hill coefficients (Fig. 2). The compounds were not adversely cytotoxic to HepG2, HEK293, or red blood cells at their antimalarial IC50’s (SI Appendix, Table S5).

Table 2.

Active indoline alkaloids

| Structure | 7G8 GB4 | HB3 Dd2 | CP250 |

|

1.7 μM (0.7, n = 8) 1.2 μM (0.5, n = 8) | 1.3 μM (0.5, n = 14) 1.1 μM (0.5, n = 14) | 1.5 μM (0.5, n = 6) |

|

2.5 μM (0.2, n = 2) 1.7 μM (0.1, n = 2) | 1.6 μM (0.3, n = 4) 1.6 μM (0.09, n = 4) | 2.3 μM (0.0, n = 2) |

|

0.7 μM (0.1, n = 4) 0.6 μM (0.07, n = 4) | 0.6 μM (0.09, n = 4) 0.6 μM (0.03, n = 4) | 0.6 μM (0.0, n = 2) |

|

0.8 μM (0.07, n = 6) 0.6 μM (0.1, n = 6) | 0.6 μM (0.0, n = 6) 0.6 μM (0.1, n = 6) | 0.6 μM (0.05, n = 2) |

Results are reported as effective concentration values needed to inhibit parasite growth at 50% (IC50) in μM. Standard deviation and number of replicates are reported in parentheses. Replicate numbers > 2 represent assays carried out under identical conditions on different days. Compounds were retested in an intraplate titration format using twelve-point, threefold dilutions.

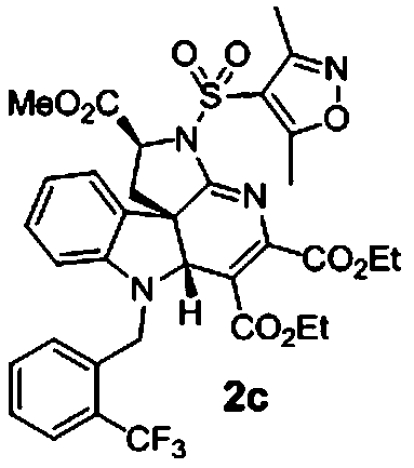

Based on the apparent preliminary SAR obtained, we synthesized analogs directed at improving potency for pan-active indoline alkaloid scaffolds. Our first observation was that substitution of the triazine methyl esters for ethyl esters reduced activity (SI Appendix, Table S5). However, due to solubility and stability issues, we chose to synthesize a series of forty ethyl ester analogs varying substitution of both the aryl sulfonamide and indole nitrogen. The most active compounds were those bearing a o-trifluoromethyl benzyl group at the indole nitrogen. Interestingly scaffolds having either p-bromo or p-nitrile-substituted benzyl groups were less active (SI Appendix, Table S5). The most active compound in this series was 2c bearing a 3,5-dimethylisoxazole sulfonamide moiety. Phenyl sulfonamides tolerated para substitution (2d and 2e) with a decrease of activity observed upon ortho substitution (SI Appendix, Table S5). These analogs were also not cytotoxic to HepG2, HEK293, or red blood cells in the range effective at inhibiting parasite growth (SI Appendix, Table S5).

Utilizing an efficient complexity building inverse-demand Diels-Alder reaction, we were able to synthesize natural product-inspired scaffolds which were utilized in library synthesis. The resulting indoline alkaloid compounds were found to inhibit growth of a number of P. falciparum lines. Initial follow-up has shown improvement of potency through analog synthesis. Continued studies are focused on further SAR and molecular target identification.

Identification of an Isolate Selective Chemotype.

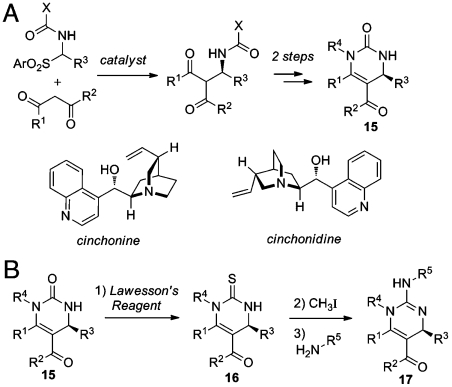

In previous studies, we demonstrated that compounds displaying differential chemical phenotypes (DCPs) by selectively acting on one of two parental lines (e.g., 7G8 or GB4) can enable the identification of genes underlying the DCPs through genetic mapping methods (10). In the CMLD-BU collection, we identified only six potential DCP’s having > 5 fold differential activity between any two lines (SI Appendix, Table S5) which were all derived from dihydropyrimidone scaffolds (15). Dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-ones exhibit wide-ranging biological activity. Chiral hetereocyclic compounds such as monastrol (20, 21) and SNAP-7941 (22) are active as single enantiomers. We have developed an organocatalytic route to these compounds using the Cinchona alkaloids, chiral bases derived from the Cinchona tree (Fig. 5) (23, 24). Because the Cinchona catalysts are available in pseudoenantiomeric form from natural sources, both enantiomers of dihydropyrimidinones are easily accessible. In a demonstration of utility, the method was used in the construction of a library (24) of chiral dihydropyrimidones 15.

Fig. 5.

(A) Organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of dihydropyrimidinone scaffolds. (B) Synthesis of DHP-derived guanidine library. Reagents: (i) 2 equivalent Lawesson’s reagent, PhCh3, reflux, 48 h. (ii) 20 equivalent CH3I, CH3CN, 75 °C, 2 h. (iii) R5-NH2, CH3CN, 83 °C, 36 h.

In designing synthetic routes for further elaboration of these chemical structures, we were inspired by naturally occurring guanidines (25) such as the batzellidines and derived analogs, inhibitors of HIV gp120-human CD4 binding (26) and HIV-1 Nef-protein interactions (27) and the muramycins, antimicrobial natural products active against Gram-positive bacteria (28, 29). A synthetic route was devised converting the dihydropyrimidinone 15 to a collection of guanidines 17 via the thiourea 16 (Fig. 5). Conversion of the dihydropyrimidinone to the thioxodihydropyrimidine was accomplished using Lawesson’s reagent (30). Alkylation of the sulfur using CH3I, followed by substitution with amines, afforded the desired guanidines in a two-step process (31). Viability of the route was demonstrated on nine dihydropyrimidinones utilized to prepare 96 guanidines. After purification by mass-directed HPLC, 81 guanidines were tested for biological activity.

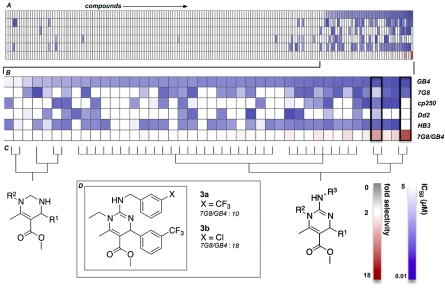

During the course of screening, these compounds were identified as possessing antimalarial activity. More importantly, a differential chemical phenotype was observed among the GB4, 7G8, Dd2, and HB3 lines (SI Appendix, Table S5) for which the progeny of two crosses are available. Fig. 6 depicts a two-dimensional heat map of activity where compounds were first ranked by IC50 in the GB4 strain followed by clustering of the chemical structures. Two structurally similar compounds were identified as possessing significant differential activity; 3a and 3b with a 7G8 IC50/GB4 IC50 (selectivity factor) of 17 and 10 (See PubChem AIDs 504316 and 504315), respectively and sufficient to allow genetic mapping.

Fig. 6.

Heat map analysis of DHP compounds. (A) Results were ranged in order of effective concentrations necessary to inhibit proliferation at 50% (IC50) in the GB4 line. The resulting structures were then clustered and fold selectivity calculated for IC50. (B) Magnification of most active compounds. (C) Substructure analysis of the most active compounds. (D) Compounds 3a and 3b exhibiting the highest level of 7G8 IC50/GB4 IC50 selectivity.

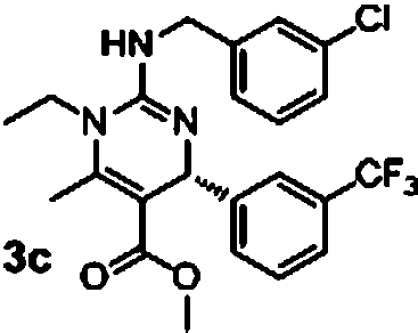

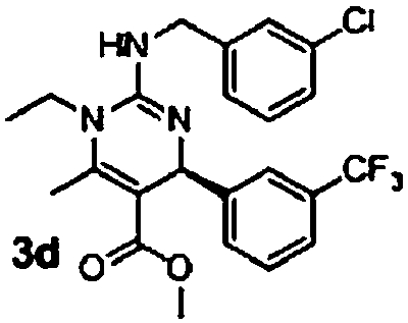

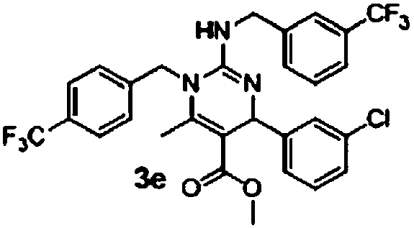

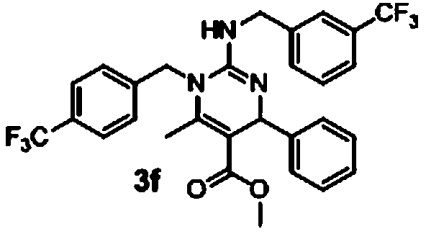

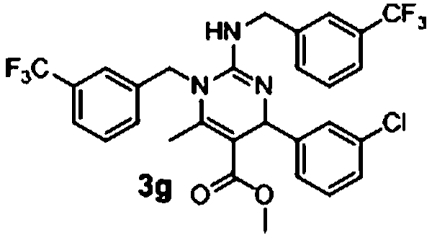

The original guanidine library was a demonstration library containing only a fraction of the full combinatorial design. Once these initial leads were retested, a second synthetic effort was undertaken to elaborate structure activity relationships. A combinatorial library of 630 compounds was designed and is currently undergoing evaluation in the antimalarial assays. From results obtained to date, this compound class possesses intriguing biological properties against malaria that offer significant potential for further development (Table 3). First, the enantiomers of 3b were independently prepared and assessed in the assays for differential activity. The R-enantiomer 3c exhibited greater activity in the GB4 line than the S-enantiomer 3d with a selectivity factor of 48 (entries 1 and 2, Table 3). More interestingly, compounds with significantly greater activity against GB4 and selectivity factors were identified (compounds 3e–3g, entries 3–5, Table 3). An initial statement about active substituents include electron deficient aromatic groups with substitution at the meta- or para- positions; the most active to date being compound 3e with an IC50 of 20 nM against GB4 and a selectivity factor of 275. While certainly at the initial stages of development, this compound design should prove suitable for identifying mechanisms of resistance and possibly unique drug target identification. Current efforts are directed toward attaining these objectives.

Table 3.

Guanidine analogs

| Entry | Structure | 7G8 | GB4 | 7G8/GB4* |

| 1 |  |

9.5 μM (0.6, n = 4) | 0.2 μM (0.06, n = 4) | 48 |

| 2 |  |

9.8 μM (0.6, n = 4) | 2.8 μM (0.3, n = 4) | 4 |

| 3 |  |

5.5 μM (0.81, n = 8) | 0.02 μM (0.04, n = 8) | 275 |

| 4 |  |

5.4 μM (0.08, n = 8) | 0.04 μM (0.06, n = 8) | 135 |

| 5 |  |

2.8 μM (2.0, n = 8) | 0.04 μM (0.04, n = 8) | 70 |

Results are reported as effective concentration values needed to inhibit parasite growth at 50% (IC50) in μM

*7G8 IC50/GB4 IC50. Standard deviation and number of replicates are reported in parentheses. Replicate numbers > 2 represent assays carried out under identical conditions on different days. Compounds were retested in an intraplate titration format using twelve-point, threefold dilutions.

Conclusion

The current work illustrates the developing paradigm for utilizing synthetic methodologies for the synthesis of libraries of complex chemotypes rich in stereochemical and structural features. Once prepared, these libraries can be examined in a host of biological processes, here exemplified with a neglected disease of the third world for discovery of probes and future drugs. In our collaborative effort, the CMLD-BU compound collection was assayed for antimalarial activity against five lines of P. falciparum with distinct geographic origins, representing genotypic variation in part resulting from acquired antimalarial drug resistance (16). Overall, the CMLD-BU compound collection provided an effective source of chemotypes in the antimalaria assays. The collection yielded 1–4% high quality actives defined as those giving qHTS curve classes 1a, 1b, or 2a (9) suitable for extraction of preliminary SAR. Specifically, we identified three compound classes which variously inhibit the growth of the P. falciparum lines tested in this study. Two compound classes in this library, polycyclic ketals and indoline alkaloid structures, were found to be active against multiple geographic parasite lines with moderate activity. A series of dihydropyrimidinone guanidines was identified leading to compounds with low nM IC50’s and high selectivity for the GB4 line. These initial efforts should pave the way for future projects directed at further development of unique antimalarial agents as well as identification of their molecular targets.

Materials and Methods

Cycloisomerization/Annulation.

Detailed procedures for the synthesis of polycyclic ketals, characterization of alkynyl benzaldehydes, description of representative library members, and biologically active polycyclic ketas are provided in the SI Appendix.

Indoline Alkaloids.

Detailed procedures for the synthesis of indoline alkadoids are outlined in previous publications (14, 16). Characterization of biologically active indoline alkaloids are provided in the SI Appendix.

Guanidine Library Preparation.

Guanidines were prepared from the corresponding thioxodihydropyrimidines. Enantioenriched thioxodihydropyrimidines were obtained via treatment of enantioenriched dihydropyrimidinones (24) with Lawesson’s reagent (30). Racemic thioxodihydropyrimidines were obtained according to the procedure of Ryabukhin, et al (32). Guanidines were synthesized according to the method of Taylor and Cain, via formation of the thiomethyl ether followed by nucleophilic displacement of thiomethane (33, 34). See SI Appendix.

Parasite Viability Assay for qHTS and Follow-Up.

Briefly, 3 μL of culture medium was dispensed into 1,536-well black clear-bottom plates (Aurora Biotechnologies) using a Multidrop Combi (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). Then, 23 nL of compounds in DMSO were added by a pin tool (Kalypsys), and 5 μL of P. falciparum-infected human red blood cells (0.3% parasitemia, 2.5% hematocrit final concentration) were added. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in a humidified incubator in 5% CO2 for 72 h, and 2 μL of lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl,10 mM EDTA, 0.16% saponin) weight to volume (w/v), 1.6% Triton-X (vol/vol), 10× SYBR Green I (supplied as 10,000× concentration by Invitrogen) were added to each well. The plates were mixed for 25 s with gentle shaking and incubated overnight at 22–24 °C in the dark. The following morning, fluorescence intensity at 485 nm excitation and 535 nm emission wavelengths were measured on an EnVision (Perkin Elmer) plate reader. The compound library was screened against each parasite line at seven fivefold dilutions beginning at 5.7 or 29 μM. The antimalarial drugs artemisinin, mefloquine, and DMSO were included as positive and negative controls for each plate, respectively. The primary qHTS results are available in PubChem under the following Assay Identification Descriptions (AIDs); Dd2 504314, GB4 504315, 7G8 504316, HB3 504318, CP250 504320.

Mammalian Cell Viability Assays.

Cell viability assays for HEK293 and HepG2 lines, and human red blood cells were carried out using Cell TiterGlo (Promega) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Assays were performed in solid white 1,536-well plates (Nexus Biosystems) and measurements made on a ViewLux (Perkin Elmer). See protocol SI Appendix, Table S3 for additional details.

Optical Interference Assay.

Potential compound interference with the SYBR green I dye viability assay was determined by adding test compound following a 72 h incubation time and reading fluorescence intensity at 485/535 nm excitation (EX)/emission (EM) on an EnVision (Perkin Elmer). See protocol SI Appendix, Table S4 for additional details.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Dr. John Schwab [National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIGMS)] for his guidance of the CMLD Centers Program, Dr. Paul Ralifo (BU) for assistance with NMR. Paul Shinn (NCGC) for compound management, and Dr. Ruili Huang for informatics assistance (NCGC). We also thank Dr. Paul Clemons (Broad Institute), Dr. Tanar Kaya (Broad Institute), and Dr. J. Anthony Wilson (Broad Institute) for assistance with principle moments of inertia analysis of the CMLD-BU compound collection. This work was generously supported by NIGMS CMLD Initiative (P50 GM067041 J.A.P., Jr.) and the Divisions of Intramural Research at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases and National Human Genome Research Institute and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research, all at the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: The chemical compounds reported in this paper have been deposited in PubChem (AIDs 504350, Dd2 504314, GB4 504315, 7G8 504316, HB3 504318, CP250 504320).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1017666108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Stanton BZ, Peng LF. A small molecule that binds Hedgehog and blocks its signaling in human cells. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:154–156. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dandapani S, Marcaurelle LA. Grand challenge commentary: accessing new chemical space for “undruggable” targets. Nat Chem Biol. 2010;6:861–863. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nören-Müller A. Discovery of a new class of inhibitors of Mycobacterium tuberculosis protein tyrosine phosphatase B by biology-oriented synthesis. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 2008;47:5973–5977. doi: 10.1002/anie.200801566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lei X, Zaarur N, Sherman MY, Porco JA., Jr Stereocontrolled synthesis of a complex library via elaboration of angular epoxyquinol scaffolds. J Org Chem. 2005;70:6474–6483. doi: 10.1021/jo050956y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Beeler AB, Su S, Singleton CA, Porco JA., Jr Discovery of chemical reactions through multidimensional screening. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:1413–1419. doi: 10.1021/ja0674744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shah S. The Fever: how malaria has ruled humankind for 500,000 years. New York: Sarah Crichton Books; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guiguemde WA, Shelat AA. Chemical genetics of Plasmodium falciparum. Nature. 2010;465:311–315. doi: 10.1038/nature09099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gamo FJ, Sanz LM. Thousands of chemical starting points for antimalarial lead identification. Nature. 2010;465:305–310. doi: 10.1038/nature09107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Inglese J, et al. Quantitative high-throughput screening: a titration-based approach that efficiently identifies biological activities in large chemical libraries. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:11473–11478. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yuan J. Genetic mapping of targets mediating differential chemical phenotypes in Plasmodium falciparum. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5:765–771. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clemons PA, et al. Small molecules of different origins have distinct distributions of structural complexity that correlate with protein-binding profiles. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18787–18792. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1012741107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sauer WH, Schwarz MK. Molecular shape diversity of combinatorial libraries: a prerequisite for broad activity. J Chem Inf Comput Sci. 2003;43:987–1003. doi: 10.1021/ci025599w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilson JA, Bender A, Kaya T, Clemons PA. Alpha shapes applied to molecular shape characterization exhibit novel properties compared to established shape descriptors. J Chem Inf Model. 2009;49:2231–2241. doi: 10.1021/ci900190z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovering F, Bikker J, Humble C. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J Med Chem. 2009;52:6752–6756. doi: 10.1021/jm901241e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bennett TN. Novel, rapid, and inexpensive cell-based quantification of antimalarial drug efficacy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1807–1810. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.5.1807-1810.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mu J. Plasmodium falciparum genome-wide scans for positive selection, recombination hot spots and resistance to antimalarial drugs. Nat Genet. 2010;42:268–271. doi: 10.1038/ng.528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Benson SC, Lee L, Yang L, Snyder JK. Intramolecular inverse electron demand diels-alder reactions of tryptamine with tethered heteroaromatic azadienes. Tetrahedron. 2000;56:1165–1180. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saxton JE. In: Alkaloids of the Aspidospermine Group The Alkaloids. Cordell GE, editor. Vol. 51. New York: Academic Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wei W. New small molecule inhibitors of hepatitis C virus. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2009;19:6926–6930. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayer TU, et al. Small molecule inhibitor of mitotic spindle bipolarity identified in a phenotype-based screen. Science. 1999;286:971–974. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeBonis S, et al. Interaction of the mitotic inhibitor monastrol with human kinesin Eg5. Biochemistry. 2003;42:338–349. doi: 10.1021/bi026716j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borowsky B, et al. Antidepressant, anxiolytic, and anorectic effects of a melanin-concentrating hormone-1 receptor antagonist. Nat Med. 2002;8:825–830. doi: 10.1038/nm741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lou S, Taoka BM, Ting A, Schaus SE. Asymmetric Mannich reactions of β-keto esters with acyl imines catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:11256–11257. doi: 10.1021/ja0537373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lou S, Dai P, Schaus SE. Asymmetric Mannich reaction of dicarbonyl compounds with α-amido sulfones catalyzed by cinchona alkaloids and synthesis of chiral dihydropyrimidones. J Org Chem. 2007;72:9998–10008. doi: 10.1021/jo701777g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wyatt EE, et al. Identification of an anti-MRSA dihydrofolate reductase inhibitor from a diversity-oriented synthesis. Chem Commun. 2008:4962–4964. doi: 10.1039/b812901k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patil AD, et al. Novel alkaloids from the sponge Batzella sp.: inhibitors of HIV gp120-Human CD4 binding. J Org Chem. 1995;60:1182–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Olszewski A, et al. Guanidine alkaloid analogs as inhibitors of HIV-1 Nef interactions with p53, actin, and p56lck. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:14079–14084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406040101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin YI, et al. Muraymycins, novel peptidoglycan biosynthesis inhibitors: semisynthesis and SAR of their derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002;12:2341–2344. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(02)00469-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald LA, et al. Structures of the muraymycins, novel peptidoglycan biosynthesis inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:10260–10261. doi: 10.1021/ja017748h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hupp CD, Tepe JJ. Total synthesis of a marine alkaloid from the tunicate Dendrodoa grossularia. Org Lett. 2008;10:3737–3739. doi: 10.1021/ol801375k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ibrahim DA, El-Metwally AM. Design, synthesis, and biological evaluation of novel pyrimidine derivatives as CDK2 inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2010;45:1158–1166. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2009.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ryabukhin SV, Plaskon AS, Ostapchuk EN, Volochnyuk DM, Tolmachev AA. N-Substituted ureas and thioureas in biginelli reaction promoted by chlorotrimethylsilane: convenient synthesis of N1-Alkyl-, N1-Aryl-, and N1,N3-Dialkyl-3,4-Dihydropyrimidin-2(1H)-(thi)ones. Synthesis. 2007;39:417–427. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Taylor EC, Cain CK. Pteridines. VII. The Synthesis of 2-Alkylaminopteridines. J Am Chem Soc. 1952;74:1644–1647. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vogel VA, Troxler F. Neue Synthesen von Pyrazolo[1,5-a]-s-triazinen. Helv Chim Acta. 1975;58:761–771. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.