Abstract

Background

Most research on the impact of mind-body training does not ask about participants' baseline experience, expectations, or preferences for training. To better plan participant-centered mind-body intervention trials for nurses to reduce occupational stress, such descriptive information would be valuable.

Methods

We conducted an anonymous email survey between April and June, 2010 of North American nurses interested in mind-body training to reduce stress. The e-survey included: demographic characteristics, health conditions and stress levels; experiences with mind-body practices; expected health benefits; training preferences; and willingness to participate in future randomized controlled trials.

Results

Of the 342 respondents, 96% were women and 92% were Caucasian. Most (73%) reported one or more health conditions, notably anxiety (49%); back pain (41%); GI problems such as irritable bowel syndrome (34%); or depression (33%). Their median occupational stress level was 4 (0 = none; 5 = extreme stress). Nearly all (99%) reported already using one or more mind-body practices to reduce stress: intercessory prayer (86%), breath-focused meditation (49%), healing or therapeutic touch (39%), yoga/tai chi/qi gong (34%), or mindfulness-based meditation (18%). The greatest expected benefits were for greater spiritual well-being (56%); serenity, calm, or inner peace (54%); better mood (51%); more compassion (50%); or better sleep (42%). Most (65%) wanted additional training; convenience (74% essential or very important), was more important than the program's reputation (49%) or scientific evidence about effectiveness (32%) in program selection. Most (65%) were willing to participate in a randomized trial of mind-body training; among these, most were willing to collect salivary cortisol (60%), or serum biomarkers (53%) to assess the impact of training.

Conclusions

Most nurses interested in mind-body training already engage in such practices. They have greater expectations about spiritual and emotional than physical benefits, but are willing to participate in studies and to collect biomarker data. Recruitment may depend more on convenience than a program's scientific basis or reputation. Knowledge of participants' baseline experiences, expectations, and preferences helps inform future training and research on mind-body approaches to reduce stress.

Background

Stress and burnout are common among nurses, the largest group of health professionals [1-7]. Maintaining a calm, compassionate attitude is a core nursing skill [8-12]. Occupational stress among nurses is important because it can adversely affect attitudes, staff morale, communication, cognition, and quality of care[2,13-15]. Training in mind-body practices, such as meditation, can reduce stress and burnout and improve health outcomes [14,16-25]. Training nurses in mind-body skills could also indirectly improve the quality of care by improving staff health and teamwork, and decreasing unanticipated absences and turnover [19,26-29]. However, little is known about the most effective mind-body practices or training for health professionals in general or nurses in particular, suggesting the need for comparative effectiveness research. Such research should be grounded upon a clear understanding of nurses' baseline experiences, expectations, and preferences for mind-body practices.

According to the US National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM), mind-body practices "focus on the interactions among the brain, mind, body, and behavior, with the intent to use the mind to affect physical functioning and promote health" and include several different practices [30]. For example, intercessory prayers for others' health, which could be considered a mind-body practice, is the most commonly used complementary health therapy in the US[31,32]. Sitting meditation practices such as deep breathing, mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR), the Relaxation Response, and Transcendental Meditation™ are also common mind-body practices [33]. Nursing practices such as therapeutic touch and healing touch include a centering component similar to meditation, and explicitly extend compassion and good will, similar to prayer.

Although there has been enormous growth in the number of studies evaluating the health benefits of meditation, the paucity of direct comparisons between training in the different kinds of practices creates a challenge for those planning mind-body training programs to reduce nurses' stress and improve health care quality and outcomes[16,34-39]. Before large comparative effectiveness studies are undertaken, a greater understanding of existing practices and preferences for future training is desirable.

Because mind-body practices are commonly used by the general public, it is likely that some nurses also use them, but few studies have assessed the prevalence of mind-body practices and training. Whether or not professionals personally practice mind-body skills, they may have expectations about their health benefits which may influence their enrollment in or response to mind-body training programs. However, little is known about nurses' expectations about the health effects of mind-body training. Also, nurses may have preferences about the type or format of training which could affect recruitment and retention in training programs, but these factors have not been systematically assessed. Before implementing expensive training programs or undertaking costly studies to compare different kinds of mind-body practices, it would be useful to better understand nurses' experiences with mind-body practices, their expectations about benefits, their preferences for training, and their willingness to participate in research.

The purpose of this study was to prepare for subsequent studies comparing different mind-body approaches to reducing occupational stress among nurses. Because most studies of mind-body training involve voluntary courses that recruit subjects who are interested in stress reduction, a voluntary survey of nurses interested in reducing stress seemed an appropriate first step. The primary study questions were: Among nurses who are interested in stress reduction: 1. What experience do they already have with mind-body practices to reduce stress? 2. In addition to reducing stress, what other health benefits do they expect mind-body approaches to have for them? 3. What factors affect their preferred training?, and 4. Would they be willing to participate in studies of training, be randomized, and provide biomarker data for such studies?

Methods

To answer these questions, an anonymous, cross-sectional on-line survey was conducted in spring, 2010. A broad response from nurses in a variety of settings was sought with the goal of receiving at least 300 completed surveys from a variety of settings. Nurses were eligible if they practiced in ambulatory or inpatient settings, community or academic settings, and whether they were in training or in practice. Internet access was necessary for participation because recruitment was conducted by email.

Recruitment was conducted solely through email. Approximately 75 email invitations were sent between April and June, 2010 to colleagues, leaders in nursing organizations, and to Listserv groups that included nurses. These included the Directors of Nursing at Wake Forest University Baptist Medical Center; the Directors of the Nursing Magnet program at the 17 North Carolina Magnet Hospitals recognized by the American Nurses' Credentialing Center; a nursing leader at the Ralph H. Johnson Veterans Administration (VA) Medical Center in Charleston, South Carolina; the Director of the Rhode Island State Nurses Association; the Dean of the School of Nursing at the University of New Brunswick; the Boston area coordinator of Therapeutic Touch International Association; and a nursing leader at Kent County Memorial Hospital in Rhode Island. They also included Listservs for Pediatric Integrative Medicine; the North Carolina Mountain Area Health Education Center's Nursing Consortium; and the Association of Wound Specialists.

The emails described the purpose of the survey and provided a link to the Survey Monkey site (SurveyMonkey can be found at http://www.surveymonkey.com. A PDF file of the survey questions is available on request from the authors), the Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval number, contact information for the investigators, and a request to forward the email to other nurses interested in mind-body practices. Due to the nature of the email survey distribution and subsequent email forwarding, it was not possible to determine a denominator for the number of nurses that eventually received an invitation to participate.

The survey was developed, reviewed, and revised by a multidisciplinary group including a meditation teacher, a psychologist with extensive experience with mind-body practices, researchers, nurses, nurse educators, and nursing administrators. It was pilot tested with two experienced nurses in two states before being distributed. In the pilot phase (which did not lead to any substantial revisions), the entire survey required less than 20 minutes to complete. It consisted of 5 e-pages with multiple choice questions: 1) previous experiences, training and practice with meditation, prayer, and other mind-body practices included in the NIH NCCAM category of mind-body practices as well as nursing biofield practices of therapeutic and healing touch (Although healing touch and therapeutic touch are generally considered biofield therapies, they were included in this survey at the suggestion of nurses who view them as ways of centering and extending compassion that reduce stress in providers as well as patients.); 2) expectations about expected benefits of meditation practice for physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and social health; 3) respondents' overall health status, occupational stress, and presence of one or more common health conditions; 4) demographic characteristics, practice location, and current involvement in research; and 5) preferences about type and format of meditation training, willingness to be randomized in comparison studies, and willingness to collect biomarker data. Answers were multiple choice and provided space for respondents to make comments.

Because the purpose of this study was to describe nurses' experiences and attitudes, data analysis relied on simple descriptive statistics. The anonymous data were downloaded from Survey Monkey into an Excel spreadsheet and exported to SAS version 9.1 for analysis.

This study was approved by the Wake Forest University Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Results

Subject characteristics

Between April 15, 2010 when the survey was approved by the IRB and June 30, 2010 when enrollment was closed, 342 nurses responded to the survey, of which 96% were women. Most (92%) were Caucasian, 4% were African American, 2% were mixed/other, 1% were Latino, and 1% were Asian. Most (63%) were more than 45 years old, and 80% had been in practice for 10 or more years. Most (62%) were registered nurses (RNs), nurses with masters or doctoral degrees (33%), or nurses' aides, licensed practical nurses (LPNs) or licensed vocational nurses (LVNs) (5%). Respondents lived in all major regions of the US designated by the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS): 58% from the southern US, 17% from the northeast, 11% from the west, 4% from the midwest; and 11% were Canadians.

The respondents practiced in a variety of settings: 36% practiced in academic health centers in inpatient settings, 26% in academic ambulatory settings, 19% in community outpatient or ambulatory settings, 11% in community inpatient settings (including long-term care, nursing homes, and hospice), and 9% in other settings.

Most (91%) nurses reported having excellent (20%), very good (41%), or good (30%) overall health. Of the 73% who reported one or more health conditions, the most common were anxiety (49%), back pain (41%), GI problems such as irritable bowel syndrome and reflux (34%), and depression (33%) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Health conditions in the past 12 months (more than one answer allowed)

| Health Conditions in Past Year | Percentage of nurses who reported this condition |

|---|---|

| Anxiety | 49 |

| Back pain | 41 |

| GI Problems such as IBS or reflux severe enough to interfere with work | 34 |

| Depression | 33 |

| Arthritis | 24 |

| High blood pressure or Heart Disease | 21 |

| Headaches severe enough to interfere with work | 19 |

| Asthma | 9 |

| Diabetes | 6 |

| Chronic pain or fibromyalgia | 3 |

| Cancer or cancer survivor | 2 |

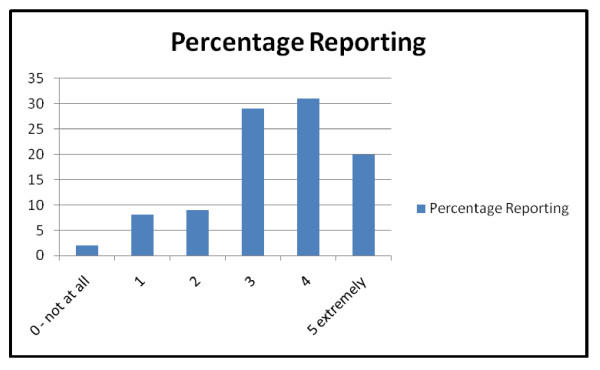

On a scale from 0 (not at all stressed) to 5 (extremely stressful), nurses' reported a median stress level 4 in their primary work environment over the past 30 days (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Stress levels in past 12 months in primary work location.

Experiences with Mind-Body Practices to Reduce Stress

Nearly all (99%) nurses reported one or more mind-body practices in the previous 12 months. The most common mind-body practices were prayer-based (Table 2). Specifically, over 85% of nurses reported having prayed for another person's health. In comparison, concentration-type meditation such as Relaxation Response or Transcendental Meditation practices were reported by 23%, and mindfulness-based meditation was reported by 18%. Other common mind-body practices included providing healing touch or therapeutic touch (39%), meditative movement such as yoga, tai chi or qigong (34%), and guided imagery or hypnosis (25%).

Table 2.

Nurses' experiences with mind-body practices in past 12 months

| Prayer practices | Percentage Practicing |

|---|---|

| Intercessory (for someone else's health or well-being) | 86 |

| Prayers of forgiveness, gratitude, or thanksgiving | 82 |

| Prayers for peace, harmony, understanding between people | 65 |

| Praise or devotion | 52 |

| Centering or grounding prayer | 40 |

| Prayerful singing | 34 |

| Reading prayers, daily devotional or sacred texts | 32 |

| Rosary | 8 |

| NO PRAYER practices in past 12 months | 6 |

| Meditation Practices | |

| Breath-focused | 49 |

| Visualization-based (object, mandala, condition) | 26 |

| Compassion or lovingkindness | 25 |

| Concentration-type (including Relaxation Response and TM) | 23 |

| Affirmation-based | 22 |

| Contemplative | 18 |

| Mindfulness-based (includes MBSR, Vipassana) | 18 |

| Sound-based (chanting or mantra-based) | 15 |

| Zen | 3 |

| NO MEDITATION practices in past 12 months | 35 |

| Other Mind-Body Practices | |

| Healing Touch or Therapeutic Touch | 39 |

| Yoga, Tai Chi, QiGong, or other mindful movement | 34 |

| Guided Imagery or Hypnosis | 25 |

| Reiki, Polarity therapy, or other mindful energy healing | 21 |

| Biofeedback to promote relaxation or well-being | 6 |

| Autogenic Training | 3 |

| Other (massage, acupuncture, crystals) | 2 |

| NO OTHER Mind-Body Practices | 29 |

| No Mind-Body Practices (Prayer, Meditation, or Other Mind-Body Practices) in Past 12 months | 1 |

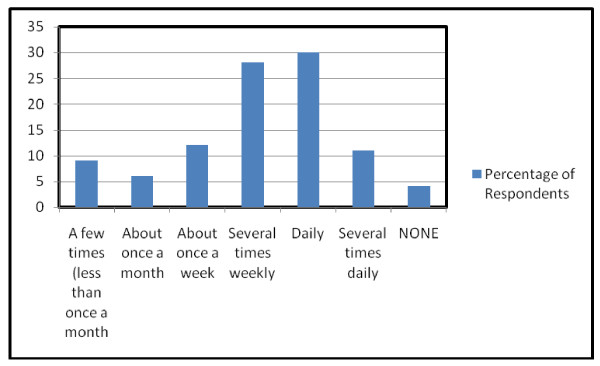

Nurses typically engaged in a mind-body practice daily or several times weekly for less than 20 minutes per session (Figure 2). Most (62%) typically practiced alone, while the rest practiced sometimes or only in groups. Nurses reported receiving several types of training, such as group training/class (42%), reading a book or web site (37%), listening to a CD/MP3 or watching a DVD or YouTube video (24%), individual training with a teacher (17%), or on-line training (4%); some (8%) nurses reported that they were already teachers of one or more mind-body practices.

Figure 2.

Frequency of mind-body practices.

Expected benefits from mind-body training

Nurses expected a variety of health benefits from additional training in mind-body practices (Table 3). At least 20% of nurses expected a great (vs. moderate, little, or no) expected benefit for every item listed on the survey. The items most commonly endorsed as having great expected benefit were more often emotional or spiritual than physical, mental, or social. For example, more than 50% of respondents expected great benefits for more serenity, less anxiety, or greater spiritual well-being, inner peace, or connection with God or a higher power. In contrast, fewer than 50% of nurses expected great benefits for pain, sleep, or being more effective in their professional or personal relationships.

Table 3.

Expected physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and social benefits of meditation training for nurses (more than one response allowed)

| Physical benefits | % of respondents expecting GREAT benefit |

|---|---|

| More resilience in the face of physical challenges | 42 |

| Sleep better | 42 |

| Overall better physical health | 41 |

| Energy or vitality better (less fatigue) | 37 |

| Strong immunity | 36 |

| Pain less/comfort greater | 33 |

| Blood pressure lower | 29 |

| Weight better | 21 |

| Emotional benefits | |

| More serenity/calmness | 54 |

| Less anxiety or worry | 53 |

| Better mood | 51 |

| More happiness or cheerfulness | 46 |

| Less burned out, discouraged, or cynical | 46 |

| More emotional resilience | 46 |

| More confidence or courage | 44 |

| More accepting | 43 |

| Mental benefits | |

| More mindful - being more present in each moment | 48 |

| Overall better mental health | 44 |

| Better intuition | 40 |

| Greater clarity | 39 |

| Better focus or concentration | 39 |

| More creative | 37 |

| Less judgmental | 37 |

| Greater discernment | 35 |

| Less distractible | 31 |

| Better memory | 26 |

| Faster thinking | 26 |

| Spiritual benefits | |

| Greater spiritual well-being | 56 |

| More inner peace | 54 |

| Greater connection with God or Higher Power | 53 |

| More compassionate or loving | 50 |

| More forgiving | 48 |

| Greater coherence (sense that life is comprehensible and meaningful) | 46 |

| More wisdom | 44 |

| Greater appreciation for nature | 42 |

| Social benefits | |

| Greater kindness | 44 |

| Better listener | 41 |

| More effective in my professional work | 40 |

| More empathetic | 39 |

| Better relationship with my patients | 37 |

| Better family relationships | 36 |

| More generous | 35 |

| Better relationships with my team | 32 |

| Stronger friendships | 31 |

| Better communication with others | 31 |

| Stronger social support | 28 |

| More social connections | 27 |

| Better relationship with my supervisor | 27 |

| Better able to ask for and receive help from others | 25 |

NOTE: The question was " how much benefit do you EXPECT that training in meditation would have for you personally?" Responses included None, A little, Moderate, or Great benefit. For simplicity, this table lists the percentage of respondents for each item who reported Great benefit.

Preferences for Training and Willingness to Participate in Research

Over 90% of nurses reported interest in receiving additional mind-body training. When given choices between in-person or electronic training methods, the most commonly chosen was in-person (45%), followed by DVD/CD/MP3 (37%), with webinar (18%) as the least preferred training method. However, convenience was cited by 74% as being essential or very important in choosing a future training program. The time required to complete training (58%), time required for daily practice (60%), and being able to train at one's own pace (58%) were also essential or very important in choosing training. Getting to know the instructor, the teacher's or program's reputation, and the scientific evidence for a program's effectiveness were all less important (Table 4).

Table 4.

Preferences for training

| Factors Affecting Training Preferences | Percentage Reporting Very important or Essential |

|---|---|

| Convenience | 74 |

| Time required for daily practice | 61 |

| Time commitment to complete training | 59 |

| Doing it at my own pace | 59 |

| Reputation of sponsoring institution | 49 |

| Reputation of teacher | 47 |

| Reinforcing or strengthening an existing skill or practice | 42 |

| Privacy | 42 |

| Consistent with my religious beliefs | 35 |

| Scientific studies supporting a particular practice | 32 |

| Introductory training | 30 |

| Getting to know the teacher better | 19 |

| Group training in person | 16 |

| Intensive training | 13 |

| Novelty (new type of practice for me) | 13 |

| Being part of a group | 12 |

NOTE: Responses included -- not at all important; somewhat important; moderately important; very important; or essential. For simplicity, this table lists the percentage of respondents who reported very important/essential (combined).

Although most (65%) of those willing to enroll in a research-related training program were also willing to be randomized, 35% had such strong preferences for type or format of training that they were unwilling participate in a study requiring randomization.

Of potential control interventions for a future study of sitting meditation, those of most interest were yoga or tai chi (52%), massage (46%), and acupuncture (36%). Fewer nurses were interested in control groups featuring advice or education about diet/nutrition (26%), exercise/fitness (27%), or natural health products (24%).

Although nurses primarily expected strong benefits for emotional and spiritual well-being, 84% of those willing to participate in a study were willing to have at least one biomarker collected before and after training to assess the impact of training. Most were willing to have weight measured (62%); collect their own saliva for cortisol measurement up to 4 times daily (60%); have their blood pressure (BP) measured (54%); have an electrocardiogram (ECG) reading to determine heart rate variability (56%); and/or blood drawn for biomarkers (53%).

Discussion

This is the first study to provide a detailed description of nurses' experience with, expectations of, and preferences for practices and training in mind-body approaches to reducing stress. These factors affect recruitment to, retention in, and impact of mind-body training programs [40-42]. They have important implications for those planning or evaluating mind-body training programs to reduce stress among health professionals.

This study focused on nurses because they are the largest group of health professionals; they often experience stress; and stress can adversely affect their personal health as well as the quality and cost of care they provide. The survey included a large number of nurses practicing in a variety of settings across North America. The results are consistent with earlier studies showing high rates of occupational stress and personal health conditions frequently related to stress such as anxiety, back pain, functional bowel disorders, and depression [2,5,43-48]. Future studies may use similar methodology to assess the experiences, expectations, and preferences of other health professionals interested in using mind-body practices to reduce occupational stress.

These results are also consistent with other surveys in which nurses had positive attitudes about mind-body therapies, were already using one or more of them, and wanted additional training [49-53]. For example, many critical care nurses personally used relaxation therapy (87%), therapeutic touch (83%), prayer (84%), and meditation (63%), and were interested in additional training [50]. Similarly, the complementary therapies most often used by the clinical nurse specialists in Minnesota included spirituality/prayer (71%), relaxed breathing (57%), and meditation (34%) [48]. The data from this study are unique in surveying North American nurses in a variety of settings who are interested in additional mind-body training, and eliciting information about a very broad range of potential practices. Our survey shows that nearly all nurses interested in mind-body training to reduce stress already practice one or more mind-body strategies. This suggests that future studies evaluating the impact of mind-body training should conduct stratified analyses to control for baseline experience and expectations.

The choice of mind-body practices to include in the survey was informed by discussion with nurses and included healing touch, therapeutic touch, and prayer as well as meditation, hypnosis, and yoga. A number of training programs teach nurses to provide therapeutic touch or healing touch, which NCCAM currently categorizes as biofield therapies. Central to both therapeutic and healing touch are the practices of centering and intentionally extending calm, caring compassion which appear to reduce stress and improve overall well being among the nurses who learn them [29,54]. Several different types of prayer were included because it is so commonly practiced as a way of coping [31]. Furthermore, the US Joint Commission mandates the assessment of patients' spiritual needs, so explicit attention to this arena is an integral aspect of nursing practice. The number of nurses using prayer as a stress management strategy exceeded our expectation; the relative proportion of professionals using different strategies may vary geographically, culturally, and by age, race, and/or profession.

The nurses in this study reported numerous expectations about the expected benefits of mind-body training on physical, emotional, mental, spiritual, and social well-being as well as stress. It was not an intervention study and did not assess the actual impact of any mind-body practice. Nurses primarily expected greater benefits in terms of spiritual well-being (56%), inner peace (54%), or serenity (54%) compared with physical outcomes such as better sleep (42%), immunity (36%), or blood pressure (29%). This information builds on results from earlier surveys in which nurses expected that complementary therapies would be helpful with a variety of physical and mental concerns including anxiety, pain, and insomnia [50,55,56]. Matching recruitment materials and outcome measures with nurses' expectations about benefits may improve recruitment and retention in future training programs. Biomarkers alone may be insufficient to capture the range of expected benefits of mind-body training.

Over 90% of nurses in this study were interested in additional training despite a high rate of existing practice. The information about factors affecting interest in participation (e.g., convenience and time required for training and practice as more important than established effectiveness or reputation) could help when planning and recruiting for training programs. Furthermore, information about preferences for in-person vs. electronic training methods can assist in planning future interventions.

Although most nurses were willing to participate in research on mind-body training, 35% were unwilling to be randomized, suggesting that a combination of RCTs and preference or cohort trials may be useful. The most frequently preferred comparison interventions (compared with sitting meditation practices) were yoga, Tai Chi or QiGong. Comparing sitting with movement-based meditative practices would be useful because movement-based practices may have additional benefits associated with exercise [57-62]. Finally, this study suggests that even though nurses have the strongest expectations about spiritual and emotional benefits of meditation, over 80% are willing to collect one or more kinds of biomarker data. However, they are less willing to have blood drawn than to be weighed or collect salivary cortisol.

As a survey of self-selected nurses, this study has several limitations. Just as only a subset of eligible subjects enroll in evaluations of mind-body training, only a subset of nurses respond to a survey on mind-body practices, so interest and practices in this survey may overestimate experience and expectations in the general nursing profession. On the other hand, the survey specifically sought responses from nurses interested in mind-body training to reduce stress, so it is likely to build a better platform for research recruiting voluntary recruits for studies of mind-body training than studies that ask nurses who may not be interested in stress reduction training. Because nurses were recruited by email, response rate cannot be calculated. The respondents included few ethnic or racial minorities; all had access to email and were able to complete an on-line survey in English, limiting generalizability. One the other hand, the survey was completed by a large number of nurses from diverse geographic locations and practice locations, increasing the likelihood that these results would be meaningful in different settings. This study did not directly assess the impact of mind-body practices, but it prepares the way for comparative effectiveness research on mind-body interventions. As a descriptive study, analyses to determine what factors predict which nurses would be interested in what types of mind-body training were not conducted. This would be a worthwhile question for future research. Finally, additional research is needed to understand nurses' perspectives on mind-body training when provided in the context of mandatory or required courses compared with elective formats.

Conclusions

This study confirms earlier research suggesting that many nurses experience high levels of work-related stress, and many already have personal experience with mind-body practices. The most commonly used practices to manage stress include prayer, breath-focused meditation, and healing touch/therapeutic touch. Nurses expect these practices to have spiritual, emotional, and mental as well as physical benefits; want training that is convenient; and are willing to participate in and collect biomarker data for comparative effectiveness research,. These results inform future projects in mind-body training and research.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

KK conceived of and drafted the survey, participated in data analysis, drafted and revised the manuscript.

DK, SB, MJO, and JM reviewed the survey instrument, disseminated the survey to nurses, reviewed and participated in revising the manuscript.

PG analyzed the data, reviewed and participated in revising the manuscript.

All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

Contributor Information

Kathi Kemper, Email: kkemper@wfubmc.edu.

Sally Bulla, Email: sbulla@wfubmc.edu.

Deborah Krueger, Email: dkrueger@wfubmc.edu.

Mary Jane Ott, Email: maryjane_ott@dfci.harvard.edu.

Jane A McCool, Email: J.McCool@neu.edu.

Paula Gardiner, Email: paula.gardiner@bmc.org.

Acknowledgements

We thank Jeff Feldman, PhD and Ann McCarty, PA-C for sharing their expertise in mind-body practices which helped frame some of the survey questions. We thank Kim Shufran, RN and Nancy Rudner-Lugo, RN, MSN, PhD for pilot testing the survey.

References

- Alacacioglu A, Yavuzsen T, Dirioz M, Oztop I, Yilmaz U. Burnout in nurses and physicians working at an oncology department. Psychooncology. 2009;18(5):543–548. doi: 10.1002/pon.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braithwaite M. Nurse burnout and stress in the NICU. Adv Neonatal Care. 2008;8(6):343–347. doi: 10.1097/01.ANC.0000342767.17606.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho EC, Muller M, de Carvalho PB, de Souza Melo A. Stress in the professional practice of oncology nurses. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28(3):187–192. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200505000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poghosyan L, Clarke SP, Finlayson M, Aiken LH. Nurse burnout and quality of care: Cross-national investigation in six countries. Res Nurs Health. 2010;33(4):288–298. doi: 10.1002/nur.20383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, Kentish-Barnes N, Timsit JF, Pochard F, Chevret S, Schlemmer B, Azoulay E. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halbesleben JR, Wakefield BJ, Wakefield DS, Cooper LB. Nurse burnout and patient safety outcomes: nurse safety perception versus reporting behavior. West J Nurs Res. 2008;30(5):560–577. doi: 10.1177/0193945907311322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays MA, All AC, Mannahan C, Cuaderes E, Wallace D. Reported stressors and ways of coping utilized by intensive care unit nurses. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 2006;25(4):185–193. doi: 10.1097/00003465-200607000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper K, Larrimore D, Dozier J, Woods C. Impact of a Medical School Elective in Cultivating Compassion Through Touch Therapies. Complement Health Pract Rev. 2006;11(1):47–56. [Google Scholar]

- Barron AC, Coakley AB, Mahoney EK. Promoting the integration of therapeutic touch in nursing practice on an inpatient oncology and bone marrow transplant unit. Int J Human Caring. 2008;12(2):81–89. [Google Scholar]

- Bossi LM, Ott MJ, DeCristofaro S. Reiki as a clinical intervention in oncology nursing practice. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2008;12(3):489–494. doi: 10.1188/08.CJON.489-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DW, Broida JP. Pandimensional field pattern changes in healers and healees: experiencing therapeutic touch. J Holist Nurs. 2007;25(4):217–225. doi: 10.1177/0898010106297571. discussion 226-217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemper KJ, Larrimore D, Dozier J, Woods C. Electives in complementary medicine: are we preaching to the choir? Explore (NY) 2005;1(6):453–458. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez M, Teresi J, Holmes D. Demoralization and attitudes toward residents among certified nurse assistants in relation to job stressors and work resources: cultural diversity in long term care. J Cult Divers. 2006;13(2):119–125. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasner MS, Epstein RM, Beckman H, Suchman AL, Chapman B, Mooney CJ, Quill TE. Association of an educational program in mindful communication with burnout, empathy, and attitudes among primary care physicians. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1284–1293. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Sapolsky RM. Stress and cognitive function. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1995;5(2):205–216. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies WR. Mindful meditation: healing burnout in critical care nursing. Holist Nurs Pract. 2008;22(1):32–36. doi: 10.1097/01.HNP.0000306326.56955.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beddoe AE, Murphy SO. Does mindfulness decrease stress and foster empathy among nursing students? J Nurs Educ. 2004;43(7):305–312. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20040701-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koszycki D, Benger M, Shlik J, Bradwejn J. Randomized trial of a meditation-based stress reduction program and cognitive behavior therapy in generalized social anxiety disorder. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(10):2518–2526. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chattha R, Nagarathna R, Padmalatha V, Nagendra HR. Effect of yoga on cognitive functions in climacteric syndrome: a randomised control study. Bjog. 2008;115(8):991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2008.01749.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson LE, Speca M, Faris P, Patel KD. One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(8):1038–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes VA, Treiber FA, Johnson MH. Impact of transcendental meditation on ambulatory blood pressure in African-American adolescents. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17(4):366–369. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiesa A, Serretti A. A systematic review of neurobiological and clinical features of mindfulness meditations. Psychol Med. 2009. pp. 1–14. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Chiesa A, Serretti A. Mindfulness-based stress reduction for stress management in healthy people: a review and meta-analysis. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(5):593–600. doi: 10.1089/acm.2008.0495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreitzer MJ, Gross CR, Ye X, Russas V, Treesak C. Longitudinal impact of mindfulness meditation on illness burden in solid-organ transplant recipients. Prog Transplant. 2005;15(2):166–172. doi: 10.1177/152692480501500210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenzweig S, Reibel DK, Greeson JM, Edman JS, Jasser SA, McMearty KD, Goldstein BJ. Mindfulness-based stress reduction is associated with improved glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a pilot study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2007;13(5):36–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaRose A, Danhauer S, Feldman J, Evans G, Kemper K. Brief Stress Reduction Training in an Academic Health Center. J Altern Complement Med. 2010. pp. 1–2. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Pagnoni G, Cekic M. Age effects on gray matter volume and attentional performance in Zen meditation. Neurobiol Aging. 2007;28(10):1623–1627. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeidan F, Johnson SK, Diamond BJ, David Z, Goolkasian P. Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Conscious Cogn. 2010;19(2):597–605. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang R, Tegeler C, Larrimore D, Cowgill S, Kemper KJ. Improving the Well-Being of Nursing Leaders Through Healing Touch Training. J Altern Complement Med. 2010;16(8):837–841. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- http://nccam.nih.gov/health/whatiscam/

- Barnes PM, Powell-Griner E, McFann K, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults: United States, 2002. Adv Data. 2004. pp. 1–19. [PubMed]

- Graham RE, Ahn AC, Davis RB, O'Connor BB, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Use of complementary and alternative medical therapies among racial and ethnic minority adults: results from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97(4):535–545. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes PM, Bloom B, Nahin RL. Complementary and alternative medicine use among adults and children: United States, 2007. Natl Health Stat Report. 2008. pp. 1–23. [PubMed]

- Cohen-Katz J, Wiley S, Capuano T, Baker DM, Deitrick L, Shapiro S. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout: a qualitative and quantitative study, part III. Holist Nurs Pract. 2005;19(2):78–86. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200503000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Katz J, Wiley SD, Capuano T, Baker DM, Kimmel S, Shapiro S. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout, Part II: A quantitative and qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2005;19(1):26–35. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200501000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Katz J, Wiley SD, Capuano T, Baker DM, Shapiro S. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on nurse stress and burnout: a quantitative and qualitative study. Holist Nurs Pract. 2004;18(6):302–308. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200411000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenberger NE, Matheis RJ, Shiflett SC, Cotter AC. Opinions and practices of medical rehabilitation professionals regarding prayer and meditation. J Altern Complement Med. 2002;8(1):59–69. doi: 10.1089/107555302753507186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Poulin PA, Seidman-Carlson R. A brief mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention for nurses and nurse aides. Appl Nurs Res. 2006;19(2):105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.apnr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe Ruff K, Mackenzie ER. The role of mindfulness in healthcare reform: a policy paper. Explore (NY) 2009;5(6):313–323. doi: 10.1016/j.explore.2009.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffaux P, de Souza JB, Potvin S, Marchand S. Pain relief through expectation supersedes descending inhibitory deficits in fibromyalgia patients. Pain. 2009;145(1-2):18–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2009.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preference Collaborative Review G. Patients' preferences within randomised trials: systematic review and patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;337:a1864. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King M, Nazareth I, Lampe F, Bower P, Chandler M, Morou M, Sibbald B, Lai R. Impact of participant and physician intervention preferences on randomized trials: a systematic review. JAMA. 2005;293(9):1089–1099. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.9.1089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdon M, Merlani P, Perneger T, Ricou B. Burnout in a surgical ICU team. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34(1):152–156. doi: 10.1007/s00134-007-0907-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery JE. Perceived sources of stress among pediatric oncology nurses. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1993;10(3):87–92. doi: 10.1177/104345429301000303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal VR, McBeth J, Zakrzewska JM, Lunt M, Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic syndromes that are frequently unexplained: do they have common associated factors? Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(2):468–476. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell T, O'Sullivan PB, Smith A, Burnett AF, Straker L, Thornton J, Rudd CJ. Biopsychosocial factors are associated with low back pain in female nursing students: a cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46(5):678–688. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elkins G, Cook T, Dove J, Markova D, Marcus JD, Meyer T, Rajab MH, Perfect M. Perceived Stress Among Nursing and Administration Staff Related to Accreditation. Clin Nurs Res. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cutshall S, Derscheid D, Miers AG, Ruegg S, Schroeder BJ, Tucker S, Wentworth L. Knowledge, attitudes, and use of complementary and alternative therapies among clinical nurse specialists in an academic medical center. Clin Nurse Spec. 2010;24(3):125–131. doi: 10.1097/NUR.0b013e3181d86cd1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy MF, Lindquist R, Watanuki S, Sendelbach S, Kreitzer MJ, Berman B, Savik K. Nurse attitudes towards the use of complementary and alternative therapies in critical care. Heart Lung. 2003;32(3):197–209. doi: 10.1016/S0147-9563(03)00040-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tracy MF, Lindquist R, Savik K, Watanuki S, Sendelbach S, Kreitzer MJ, Berman B. Use of complementary and alternative therapies: a national survey of critical care nurses. Am J Crit Care. 2005;14(5):404–414. quiz 415-416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindquist R, Tracy MF, Savik K. Personal use of complementary and alternative therapies by critical care nurses. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;15(3):393–399. doi: 10.1016/S0899-5885(02)00104-1. x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes KM, Alexander IM. Alternative therapies and nurse practitioners: knowledge, professional experience, and personal use. Holist Nurs Pract. 2000;14(3):49–58. doi: 10.1097/00004650-200004000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitch MI, Gray RE, Greenberg M, Douglas MS, Labrecque M, Pavlin P, Gabel N, Freedhoff S. Oncology nurses' perspectives on unconventional therapies. Cancer Nurs. 1999;22(1):90–96. doi: 10.1097/00002820-199902000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElligott D, Holz MB, Carollo L, Somerville S, Baggett M, Kuzniewski S, Shi Q. A pilot feasibility study of the effects of touch therapy on nurses. J N Y State Nurses Assoc. 2003;34(1):16–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keegan L. Alternative and complementary modalities for managing stress and anxiety. Crit Care Nurse. 2000;20(3):93–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards K, Nagel C, Markie M, Elwell J, Barone C. Use of complementary and alternative therapies to promote sleep in critically ill patients. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2003;15(3):329–340. doi: 10.1016/S0899-5885(02)00051-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wall RB. Tai Chi and mindfulness-based stress reduction in a Boston Public Middle School. J Pediatr Health Care. 2005;19(4):230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor-Piliae RE, Haskell WL, Waters CM, Froelicher ES. Change in perceived psychosocial status following a 12-week Tai Chi exercise programme. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54(3):313–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03809.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Telles S, Naveen KV, Dash M. Yoga reduces symptoms of distress in tsunami survivors in the andaman islands. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2007;4(4):503–509. doi: 10.1093/ecam/nem069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danhauer SC, Tooze JA, Farmer DF, Campbell CR, McQuellon RP, Barrett R, Miller BE. Restorative yoga for women with ovarian or breast cancer: findings from a pilot study. J Soc Integr Oncol. 2008;6(2):47–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalsa SBS, Khalsa SBS, Shorter SM, Cope S, Wyshak G, Sklar E. Yoga ameliorates performance anxiety and mood disturbance in young professional musicians. Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback. 2009;34(4):279. doi: 10.1007/s10484-009-9103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdee GS, Wayne PM, Davis RB, Phillips RS, Yeh GY. T'ai chi and qigong for health: patterns of use in the United States. J Altern Complement Med. 2009;15(9):969–973. doi: 10.1089/acm.2009.0174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]