Abstract

Background

In the recently published meta-analysis of multiple sclerosis genome-wide association studies De Jager et al. identified three single nucleotide polymorphisms associated to MS: rs17824933 (CD6), rs1800693 (TNFRSF1A) and rs17445836 (61.5 kb from IRF8). To refine our understanding of these associations we sought to replicate these findings in a large more extensive independent sample set of 11 populations of European origin.

Principal Findings

We calculated individual and combined associations using a meta-analysis method by Kazeem and Farral (2005). We confirmed the association of rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A (p 4.19×10−7, OR 1.12, 7,665 cases, 8,051 controls) and rs17445836 near IRF8 (p 5.35×10−10, OR 0.84, 6,895 cases, 7,580 controls and 596 case-parent trios) The SNP rs17824933 in CD6 also showed nominally significant evidence for association (p 2.19×10−5, OR 1.11, 8,047 cases, 9,174 controls, 604 case-parent trios).

Conclusions

Variants in TNFRSF1A and in the vicinity of IRF8 were confirmed to be associated in these independent cohorts, which supports the role of these loci in etiology of multiple sclerosis. The variant in CD6 reached genome-wide significance after combining the data with the original meta-analysis. Fine mapping is required to identify the predisposing variants in the loci and future functional studies will refine their molecular role in MS pathogenesis.

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a complex neurological autoimmune disease with few known predisposing factors. Both genetic and environmental components have been predicted to play a role in MS etiology and the role of the HLA-locus, HLA-DBR1 in particular, is well recognized [1], [2]. Recently, genome-wide association and candidate gene studies have revealed significant associations to MS outside the HLA-locus in IL2RA [2], IL7R [2], CD58 [3], CLEC16A [4], TYK2 [5], STAT3 [6], IL12A, MPHOSPH9/CDJ2AP1, EVI5 [2], KIF21B [2], [7], TMEM39A [2], [7], CYP27B1 [8], CD226 [4], CD40 [8], CBLB [9] and RGS1 [10], but with modest odds ratios suggesting the involvement of other loci.

In a recently published meta-analysis of six genome-wide analysis (GWA) study sets of 2,624 MS cases and 7,220 controls from four populations of European origin (United States, United Kingdom, Netherlands and Switzerland), De Jager et al. identified three single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with MS with significance exceeding the genome-wide significance level of p<5×10−8: rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A, rs17445836 61.5 kb from IRF8 and rs17824933 in CD6 [11]. De Jager et al. replicated these findings in 2,215 cases and 2,116 controls from UK and US. Recently, there have been reports showing significant genetic differences in allele frequencies between populations even within Europe [12], [13], [14] which has led to speculation of allelic heterogeneity. We set out to replicate the association of these SNPs to MS in a more extensive sample set with varying European origins.

Results

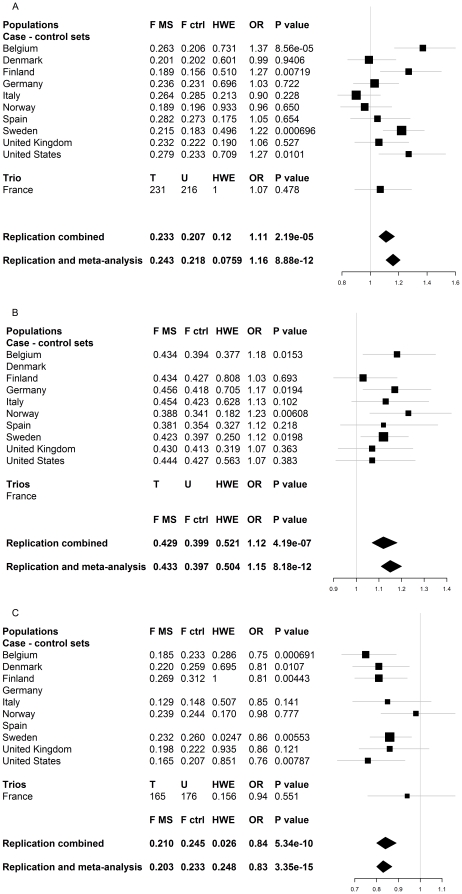

We investigated the top three SNP associations by De Jager et al. (rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A, rs17445836 61.5 kb from IRF8 and rs17824933 in CD6) in an independent sample set of 11 populations of varying European origins, comprising a total of 8,439 cases, 9,280 controls and 608 case-parent trios (Table 1). Cases and controls were selected from the same populations to minimize population stratification. We performed meta-analysis using a method by Kazeem and Farrall (2005) [15] and observed nominal association (p<0.05) with multiple sclerosis for rs17824933 in CD6 in four of the eleven cohorts (Figure 1a), for rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A in four out of nine available cohorts (Figure 1b) and for rs17445836 near IRF8 in five out of nine available cohorts (Figure 1c) (see materials and methods for details).

Table 1. Summary of all independent replication sample sets.

| Sets | N trios | N ctrl | N MS | % PPMS | Sex ratios F∶MMS, ctrl | EDSS | disease duration | Genotyping platform |

| Belgium | 0 | 1,021 | 776 | 13.7 | 1.8∶1, 1.1∶1 | 4.8 | 14 | TaqMan® (Applied Biosystems) |

| Denmark | 0 | 1,090 | 634 | 7.6 | 2.0∶1, 1.6∶1 | 4.1 | 12 | Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold |

| Finland | 0 | 1,077 | 792 | 9.4 | 2.4∶1, 1.4∶1 | 4.5 | 21 | Sequenom®,TaqMan®* |

| France | 608 | 0 | 0 | 12.0 | 2.4∶1, 1.0∶1 | 3.4 | 9.1 | TaqMan® (Applied Biosystems) |

| Germany | 0 | 911 | 930 | <1% | n.a. | n.a. | 7 | Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold |

| Italy | 0 | 629 | 828 | 11.1 | 2.0∶1, 1.0∶1 | 3.2 | 32 | TaqMan® (Applied Biosystems) |

| Norway | 0 | 1,027 | 662 | 17.7 | 2.6∶1, 2.0∶1 | 4.6 | 16 | Sequenom®,TaqMan®* |

| Spain | 0 | 501 | 501 | 19.9 | 1.8∶1, 1.1∶1 | 4.2 | 14 | TaqMan® (Applied Biosystems) |

| Sweden | 0 | 1,723 | 2,016 | 5.8 | 2.5∶1, 2.0∶1 | 3.3 | n.a. | Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold |

| United Kingdom | 0 | 714 | 656 | 14.4 | 2.8∶1, 2.8∶1 | 4.8 | 18 | Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold |

| United States | 0 | 587 | 644 | 12.0 | 1.1∶1, 1.1;1 | 4.1 | 15 | Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold |

| Total | 608 | 9,280 | 8,439 | 2.1∶1, 1.4∶1 |

All sample sets for the replication are independent, cases had clinically definite MS by either the Poser or McDonald criteria and anonymous population samples from respective populations were used as controls. The clinical parameters for MS patients describe the percentage of primary progressive MS (PPMS) of all cases, the mean EDSS score and the mean disease duration. The original GWA meta-analysis sample sets by De Jager et al. that were used in the combined analysis of the original GWA results and our independent replication have been described elsewhere [11], [16].

*The Norwegian and Finnish samples were genotyped with the Applied Biosystems TaqMan® platform for rs1800693 and Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold for rs17624933 and rs17445836.

Figure 1. Summary of results.

The results for individual populations are presented here each population on its own line. For each population we report the allele frequency in MS patients (F MS) and controls (F ctrl), Hardy-Weinberg (dis)equilibrium (HWE) p value, odds ratio (OR) and association p value. The association analyses were performed according to Kazeem and Farral [15]. The reported HWE p value is reported for cases and controls combined, but no significant deviation was observed within cases or controls when analyzed separately (data not shown). Figure 1a represents the results for rs17824933 in CD6. The Replication -line is the combined result of all independent sample sets in the replication (8,047 cases, 9,174 controls, 604 case-parent trios) and “Combined with De Jager et al. GWA” set includes the De Jager et al. [11] GWA data set (2,624 cases, 7,220 controls). Figure 1b summaries the results for rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A. Genotyping was unsuccessful in two sample sets (Danish case – control set and French case-parent trios) for rs1800693. Indipendent replication data set (“Replication”) included total of 7,665 cases and 8,051 controls and the “Combined with De Jager et al. GWA” set includes available genotypes from De Jager et al. [11] (1,829 cases, 2,591 controls). Figure 1c is a summary of results for rs17445836 (61.5 kb from IRF8). The genotyping was unsuccessful in two sample sets (Spanish and German case – control sets). The independent replication set (Replication) includes in total 6,895 cases, 7,580 controls and 596 case-parent trios and the “Combined with De Jager et al. GWA” set includes available genotypes from De Jager et al. [11] (2,624 cases, 7,220 controls).

In all except three cohorts (Denmark, Italy and Norway for the CD6 rs17824933 C allele) allele frequency differences between cases and controls had a trend towards the same direction as seen in the original meta-analysis [11] (Figure 1).Most of the individual cohorts had limited estimated power (varying between 25–82%, alpha 0.05) to observe the association by themselves (Table S1). Nevertheless, the estimated power for a combined analysis was >99% (alpha 0.05) to detect association to variants with the same effect sizes as observed in the original meta-analysis (rs1800693 OR 1.2, rs17445836 OR 0.80, rs17824933 OR 1.18).

The combined analysis confirmed independent associations with two of the SNPs with odds ratios comparable to those observed in the original meta-analysis: rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A (p 4.19×10−7, OR 1.12, 95% CI 1.07–1.18) and rs17445836 near IRF8 (p 5.34×10−10, OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.80–0.89) (Figure 1b and c, respectively). Nominally significant association for rs17824933 in CD6 was also observed (p 2.19×10−5, OR 1.11, 95% CI 1.06–1.17) (Figure 1a). Combining the replication data with the original meta-analysis data from De Jager et al. did not significantly change the observed odds ratios (Figure 1). We noticed an unequal distribution of minor allele frequencies across European populations as might be expected [12], [13], [14] in the rs17445836 and rs17824933 SNPs (Figure 1). However, the Breslow-Day test confirmed that there was no major heterogeneity in the odds ratios, although the allele frequency differences were significant between several populations when controls from different populations were compared in a pair-wise manner with a standard association tests (Table S2).

Discussion

We conclude that the SNPs rs1800693 (TNFRSF1A) and rs17445836 (IRF8) are convincingly associated to MS in this independent replication set. This supports the role of these genes in MS etiology. The rs17824933 (CD6) showed nominally significant association in the analysis combining the replication cohorts, although the association in most of the individual cohorts was not significant. It is possible that the lack of association in some cohorts is due to true population heterogeneity, but the individual cohorts in our study do not have enough power to draw any definite conclusions. Especially, since the cohorts showing an opposite trend have little power by themselves. None of these three genes (CD6, TNFRSF1A or IRF8) had shown association above the replication inclusion threshold in the IMSGC [2] or Gene MSA [16] original publications (p<10−4), but by combining the data in a meta-analysis the full advantage of these cohorts could be used to mine more MS susceptibility affecting genes [11].

Rare mutations in previously validated MS susceptibility genes have been implicated in rare monogenic disorders. For example, mutations in IL2RA [17] and IL7R [18] cause immunodeficiency and mutation in TYK2 [19] and STAT3 [20] have been reported to cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Similarly, mutations in TNFRSF1A can cause TRAPS, a disease of the immune system characterized by periodic fevers [21]. It is interesting, that both TRAPS and relapsing-remitting form of multiple sclerosis are characterized by periodic activations of autoimmunity. A recent study in a small German cohort reported that 24% (6/25) of patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS) or MS with TRAPS-like symptoms were carrying an amino-acid changing allele R92Q of the SNP rs4149584 in TNFRSF1A [22]. In addition, they reported that the frequency of the R92Q allele was 4.66% in a general MS patient sample set (n 365) and 2.95% in a population sample (n 407) (p 0.112) [22].

TNFRSF1A codes for the precursor of TNF binding protein 1 and TNFR superfamily member 1A, a receptor that binds TNF-alpha and -beta, is involved in inflammatory responses and mediates apoptosis [23]. Experiments using knockout mice have shown, that mice with no functional p55 (TNFR1/Tnfrsf1a/CD120a) receptor were resistant to experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE), the rodent model of MS [24]. On the other hand, clinical studies using lenercept, a recombinant TNF receptor p55 immunoglobulin fusion protein (sTNFR-IgG p55) that protects against EAE, reported increased exacerbation in a phase I safety trial patients using lenercept compared to patients using placebo [25].

CD6 is a T cell surface antigen involved in cell-cell adhesion [26]. It shares a role with a previously identified MS associated gene CD58 [3] in affecting the adhesion of the immune cells [27]. Interestingly, CD6 has been suggested to play a role in the apoptosis-resistance and positive selection of immature thymocytes during their maturation in thymus [28]. IRF8 is an interferon sensitive response element (ISRE) binding transcription factor expressed in cells of the immune system and responding to type 1 interferon stimulus [29]. It has been reported to regulate macrophage differentiation [30], has a critical role in the development of myeloid cells [31] and is likely involved in B-cell lineage specification, commitment and differentiation [32]. Both CD6 and IRF8 are involved in the development and maturation of leukocytes, which seems to emphasize the assumed autoimmune nature of MS.

TNFRSF1A, IRF8 and CD6 fit into the gradually emerging picture of the MS etiology as they have functions in various pathways involved in regulation of inflammatory responses in adaptive immunity and development of the immune system together with the previously identified MS associated genes HLA-DRB1 [1], IL7R [2], IL2RA [2], CLEC16A [2], [4] and CD58 [3], TYK2 [5], STAT3 [6] [6], IL12A, MPHOSPH9/CDJ2AP1, KIF21B [2], [7], TMEM39A [2], [7], CYP27B1 [8], CD226 [4], CD40 [8], CBLB [9] and RGS1 [10]. Thus, detailed fine mapping of these three genes together with other previously identified loci is needed to identify the causative variants. Future functional characterization of the identified variants will refine their role in MS pathogenesis and will enable the search for potential pathways and targets for future interventions.

Materials and Methods

Ethics Statement

All patient samples were collected with written informed consent. The study has been approved by appropriate local ethics committees: for Finnish sample collection and study design the Helsinki University Hospital ethics committee of ophthalmology, otorhinolaryngology, neurology and neurosurgery (permit no. 192/E9/02), for the Belgian cohort Commissie voor medische ethiek/klinisch onderzoek, Faculteit Geneeskunde K.U.Leuven (permit ML4733), for the Danish cohort The Danish Research Ethics Committee (permit KF 01314 009). The ethics committee approvals for all cohorts are listed in Table S3.

Samples and genotyping

All samples had clinically definite MS by either the Poser criteria or McDonald criteria and anonymous population samples from respective populations were used as controls. (Table 1) All cohorts used in this independent replication were genotyped in local centers using either Taqman (Applied Biosystems, CA,USA) or Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold platform (SEQUENOM, CA, US) and manufacturer protocols, except for the Danish and Norwegian samples that were genotyped in Finland for rs17445836 and rs17824933 (Sequenom® iPLEX® Gold) (Table 1). The original meta-analysis sample sets from De Jager et al., that we used in the combined analysis of the original GWA and our replication results (Figure 1, last line), and their genotyping have been described elsewhere [11], [16].

Statistical analyses

We excluded from the analysis all samples with >1 missing genotype and SNPs with <90% success rate or Hardy-Weinberg disequilibrium (HWE) p<0.001 per population. Using these criteria we excluded rs17445836 (IRF8) from the Spanish and German cohorts and rs1800693 (TNFRSF1A) from the Danish and French cohorts.

We performed both an independent replication analysis and a combined analysis using the original De Jager et al. GWA sample set. The analyses were performed according to Kazeem and Farral [15] and the calculations were done using R 2.9.0 (www.r-project.org). The Hardy-Weinberg (dis)equilibrium analysis p values were calculated using PLINK v1.06 (http://pngu.mgh.harvard.edu/~purcell/plink/). The T (Transmitted alleles) and U (Undertransmitted alleles) for the case-parent trios have been obtained from PLINK v1.06 transmission disequilibrium test (TDT) analysis.

Supporting Information

Power calculations for all study sets. All calculations were done using Researcher's toolkit's Statistical Power Calculator's two-tailed test with percentages by DSS (http://www.dssresearch.com/toolkit/spcalc/power_p2.asp) alpha = 5% for false positive probability, fixed MAFs calculated from the ORs of the combined effects and allele frequencies from the original study by De Jager et al. 2009. These results show that most of the individual sample sets have only moderate power to detect the association by themselves, but together have over 99% power to detect these variants with these effect sizes. The power for trios was not estimated.

(DOC)

Differences in rs17824933, rs1800693 and rs17445836 minor allele frequencies between population based controls. This table shows results for pair-wise associations between controls from different populations. We used the controls from populations on the left as cases and controls from the population above as controls. For French samples, healthy parents from case-parent trio samples were used as population controls. Uncorrected p-values are shown, but all values below p 0.000303 are significant (α = 0.05) after Bonferroni correction. Table S2a has the results for rs17624933 in CD6, Table S2b describes the results for rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A and Table S2c describes results for 17445836 61.5 kb from IRF8.

(DOC)

Ethics committee approvals for all cohorts. This study has been approved by appropriate local ethics committees as listed in this table by sample set. For each cohort we report the ethics committee or equivalent authority and the approval number.

(DOC)

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all participating MS patients and families. We also wish to thank Liisa Arala and Anne Vikman for their invaluable assistance and technical support. Concerning the statistical analyses, we sincerely thank Dr Samuli Ripatti who has provided valuable assistance and advice. The IMSGC and Gene MSA consortia are acknowledged for the data from the original meta-analysis. Danish Multiple Sclerosis Society is acknowledged for supporting the Danish sample collection and The Norwegian Bone Marrow Donor Registry is acknowledged for collaboration in establishment of the Norwegian control material. Dr Mauri Reunanen (Oulu University Hospital and University of Oulu), Dr Tuula Pirttilä (Kuopio University Hospital and University of Kuopio) and Dr Keijo Koivisto (Seinäjoki Central Hospital) are thanked for their efforts in recruiting Finnish MS patients. We also would like to acknowledge the Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland FIMM Technology Center for genotyping assistance. The French network REFGENSEP acknowledges the collaboration of CIC Pitié-salpêtrière (Centre d'Investigation Clinique) and Généthon.

Consortium Authors

Virpi Leppä1,2,3, Ida Surakka1,2, Pentti J. Tienari4, Irina Elovaara5, Alastair Compston6, Stephen Sawcer6, Neil Robertson7, Philip L. De Jager8,9, Cristin Aubin9, David A. Hafler9,10, Annette Bang Oturai11, Helle Bach Søndergaard11, Finn Sellebjerg11, Per Soelberg Sørensen11, Bernhard Hemmer12, Sabine Cepok12, Juliane Winkelmann12,13,14, Heinz-Erich Wichmann15,16, Manuel Comabella17, Marta F. Bustamante17, Xavier Montalban17, Tomas Olsson18, Ingrid Kockum18, Jan Hillert19, Lars Alfredsson20, An Goris21, Bénédicte Dubois21, Inger-Lise Mero22,23, Cathrine Smestad22, Elisabeth G. Celius22, Hanne F. Harbo22,24, Sandra D'Alfonso25, Laura Bergamaschi25, Maurizio Leone26, Giovanni Ristori27, Ludwig Kappos28, Stephen L. Hauser29, Isabelle Cournu-Rebeix30, Bertrand Fontaine30, Steven Boonen31, Chris Polman32, Aarno Palotie1,33,34,35, Leena Peltonen1,2,9,33,† and Janna Saarela1,2,36

1 Institute for Molecular Medicine Finland FIMM, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

2 Public Health Genomics Unit, National Institute for Health and Welfare, Helsinki, Finland

3 Helsinki Biomedical Graduate School, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

4 Helsinki University Central Hospital, Department of Neurology and University of Helsinki, Biomedicum, Molecular Neurology Programme, Helsinki, Finland

5 University of Tampere and Tampere University Hospital, Department of Neurology, Tampere, Finland

6 Department of Clinical Neurosciences, University of Cambridge, Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, UK

7 Department of Neurology, Ophthalmology and Audiological Medicine, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff, CF14 4XN, UK

8 Program in Translational NeuroPsychiatric Genomics, Department of Neurology, Brigham & Women's Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MS, USA

9 The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA

10 Departments of Neurology and Immunobiology, Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06520-8018, USA

11 Danish Multiple Sclerosis Center, University of Copenhagen and Department of Neurology, Rigshospitalet, Copenhagen, Denmark

12 Klinik für Neurologie, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Technische Universität, München, Germany

13 Institut für Humangenetik, Technische Universität München, München, Germany

14 Institut für Humangenetik, Helmholtz Zentrum München, München, Germany

15 Institute of Epidemiology, Helmholtz Zentrum München-German Research Center for Environmental Health, Munich, Germany

16 Institute of Medical Informatics, Biometry and Epidemiology, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, Munich, Germany

17 Centre d'Esclerosi Múltiple de Catalunya, CEM-Cat, Unitat de Neuroimmunologia Clínica, Hospital Universitari Vall d'Hebron (HUVH), Barcelona, Spain

18 Neuroimmunology Unit, Center for Molecular Medicine, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

19The Multiple Sclerosis Research Group, Center for Molecular Medicine, Department of Clinical Neuroscience, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

20 Institute of Environmental Medicine, Karolinska Institutet, Stockholm, Sweden

21 Laboratory for Neuroimmunology, Section for Experimental Neurology, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven, Herestraat 49 bus 1022, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

22 Department of Neurology, Oslo University Hospital, 0407 Oslo, Norway

23 Institute of Immunology, Oslo University Hospital, 0027 Oslo, Norway

24 University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

25 Department of Medical Sciences and Interdisciplinary Research Center of Autoimmune Diseases (IRCAD), University of Eastern Piedmont, Novara, Italy

26 Department of Neurology, Ospedale Maggiore and IRCAD, Novara, Italy

27 Department of Neurology and Center for Experimental Neurological Therapy (CENTERS), Università La Sapienza, Roma, Italy

28 Departments of Neurology and Biomedicine University Hospital Basel, University of Basel, Switzerland

29 Department of Neurology, University of California at San Francisco, US

30 on behalf of the French Genetics MS network REFGENSEP, INSERM, UMR_S975, Paris, France, UPMC Univ Paris 06, UMR_S975, Centre de Recherche Institut du Cerveau et de la Moelle, CNRS 7225. Department of Neurology, Hôpital Pitié –Salpêtrière, AP-HP, Paris, France

31 Leuven University Center for Metabolic Bone Diseases and Division of Geriatric Medicine, University of Leuven, 3000 Leuven, Belgium

32 Department of Neurology, Vrije Universiteit Medical Centre, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

33 Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, Wellcome Trust Genome Campus, Hinxton, Cambridge, CB10 1SA, United Kingdom

34 Program in Medical and Population Genetics and Genetic Analysis Platform, The Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA 02142, USA

35 Department of Medical Genetics, University of Helsinki and University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

36Department of Gynecology and Pediatrics, Department of Child Psychiatry, Helsinki University Central Hospital, Helsinki, Finland

†Posthumously

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (grants RO1 NS 43559 and RO1 NS049477), Center of Excellence for Complex Disease Genetics of the Academy of Finland (grants 213506, 129680), the Sigrid Juselius Foundation, the Biocentrum Helsinki Foundation, Helsinki University Central Hospital Research Foundation, the Neuropromise EU project (grant LSHM-CT-2005-018637), The Wellcome Trust grant (089061/Z/09/Z), the Cambridge NIHR Biomedical Research Centre, The Danish Council for Strategic Research grant 2142-08-0039, Italian Foundation for Multiple Sclerosis (FISM grants 2008/R/11), Regione Piemonte Ricerca Sanitaria Finalizzata (2007, 2008), Fondazione Cariplo grant n° 2010- 0728, Progetto Strategico 2007 - Italian Ministry of Health, CRT Foundation, Torino, National Multiple Sclerosis Foundation (USA) and Swiss MS society. South and Eastern Norway Regional Health Authority is acknowledged for support to genotyping of Norwegian samples. The French network REFGENSEP is financially supported by INSERM (Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Médicale), ARSEP (Association pour la Recherche sur la Sclérose En Plaques) and AFM (Association Française contre les Myopathies). The German group was supported by a grant from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (Krankheitsbezogenes Kompetenznetzwerk Multiple Sklerose, Control-MS). The Swedish group was supported by the Swedish Medical Research Council, The Söderberg Foundation, Swedish Council for Working Life and Social and the Bibbi och Nils Jensens Stiftelse (Foundation). Bénédicte Dubois is a Clinical Investigator of the Research Foundation Flanders (FWO-Vlaanderen) Bayer Chair on fundamental genetic research regarding the neuroimmunological aspects of multiple sclerosis and the Biogen Idec Chair Translational Research in Multiple Sclerosis at the KULeuven, Leuven, Belgium. PLD is a Harry Weaver Neuroscience Scholar of the National MS Society, and this work is supported by R01 NS067305. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Jersild C, Fog T. Histocompatibility (HL-A) antigens associated with multiple sclerosis. Acta Neurol Scand Suppl. 1972;51:377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IMSGC. Risk alleles for multiple sclerosis identified by a genomewide study. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:851–862. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.De Jager PL, Baecher-Allan C, Maier LM, Arthur AT, Ottoboni L, et al. The role of the CD58 locus in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5264–5269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813310106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IMSGC. The expanding genetic overlap between multiple sclerosis and type I diabetes. Genes Immun. 2009;10:11–14. doi: 10.1038/gene.2008.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burton PR, Clayton DG, Cardon LR, Craddock N, Deloukas P, et al. Association scan of 14,500 nonsynonymous SNPs in four diseases identifies autoimmunity variants. Nat Genet. 2007;39:1329–1337. doi: 10.1038/ng.2007.17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jakkula E, Leppa V, Sulonen AM, Varilo T, Kallio S, et al. Genome-wide association study in a high-risk isolate for multiple sclerosis reveals associated variants in STAT3 gene. Am J Hum Genet. 2010;86:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2010.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IMSGC. Comprehensive follow-up of the first genome-wide association study of multiple sclerosis identifies KIF21B and TMEM39A as susceptibility loci. Hum Mol Genet. 2010;19:953–962. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.ANZgene. Genome-wide association study identifies new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci on chromosomes 12 and 20. Nat Genet. 2009;41:824–828. doi: 10.1038/ng.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanna S, Pitzalis M, Zoledziewska M, Zara I, Sidore C, et al. Variants within the immunoregulatory CBLB gene are associated with multiple sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2010;42:495–497. doi: 10.1038/ng.584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.IMSGC. IL12A, MPHOSPH9/CDK2AP1 and RGS1 are novel multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Genes Immun. 2010;11:397–405. doi: 10.1038/gene.2010.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Jager PL, Jia X, Wang J, de Bakker PI, Ottoboni L, et al. Meta-analysis of genome scans and replication identify CD6, IRF8 and TNFRSF1A as new multiple sclerosis susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2009;41:776–782. doi: 10.1038/ng.401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lao O, Lu TT, Nothnagel M, Junge O, Freitag-Wolf S, et al. Correlation between genetic and geographic structure in Europe. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1241–1248. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelis M, Esko T, Magi R, Zimprich F, Zimprich A, et al. Genetic structure of Europeans: a view from the North-East. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5472. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Novembre J, Johnson T, Bryc K, Kutalik Z, Boyko AR, et al. Genes mirror geography within Europe. Nature. 2008;456:98–101. doi: 10.1038/nature07331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kazeem GR, Farrall M. Integrating case-control and TDT studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2005;69:329–335. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2005.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Baranzini SE, Galwey NW, Wang J, Khankhanian P, Lindberg R, et al. Pathway and network-based analysis of genome-wide association studies in multiple sclerosis. Hum Mol Genet. 2009;18:2078–2090. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sharfe N, Dadi HK, Shahar M, Roifman CM. Human immune disorder arising from mutation of the alpha chain of the interleukin-2 receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3168–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Puel A, Ziegler SF, Buckley RH, Leonard WJ. Defective IL7R expression in T(−)B(+)NK(+) severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat Genet. 1998;20:394–397. doi: 10.1038/3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, Watanabe K, Agematsu K, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:745–755. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Tsuchiya S, Tsuge I, Takada H, et al. Dominant-negative mutations in the DNA-binding domain of STAT3 cause hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2007;448:1058–1062. doi: 10.1038/nature06096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ryan JG, Aksentijevich I. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome: toward a molecular understanding of the systemic autoinflammatory diseases. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:8–11. doi: 10.1002/art.24145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kumpfel T, Hoffmann LA, Rubsamen H, Pollmann W, Feneberg W, et al. Late-onset tumor necrosis factor receptor-associated periodic syndrome in multiple sclerosis patients carrying the TNFRSF1A R92Q mutation. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;56:2774–2783. doi: 10.1002/art.22795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Micheau O, Tschopp J. Induction of TNF receptor I-mediated apoptosis via two sequential signaling complexes. Cell. 2003;114:181–190. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00521-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van Oosten BW, Barkhof F, Truyen L, Boringa JB, Bertelsmann FW, et al. Increased MRI activity and immune activation in two multiple sclerosis patients treated with the monoclonal anti-tumor necrosis factor antibody cA2. Neurology. 1996;47:1531–1534. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Whitney GS, Starling GC, Bowen MA, Modrell B, Siadak AW, et al. The membrane-proximal scavenger receptor cysteine-rich domain of CD6 contains the activated leukocyte cell adhesion molecule binding site. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:18187–18190. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sewell WA, Palmer RW, Spurr NK, Sheer D, Brown MH, et al. The human LFA-3 gene is located at the same chromosome band as the gene for its receptor CD2. Immunogenetics. 1988;28:278–282. doi: 10.1007/BF00345506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singer NG, Fox DA, Haqqi TM, Beretta L, Endres JS, et al. CD6: expression during development, apoptosis and selection of human and mouse thymocytes. Int Immunol. 2002;14:585–597. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxf025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nelson N, Marks MS, Driggers PH, Ozato K. Interferon consensus sequence-binding protein, a member of the interferon regulatory factor family, suppresses interferon-induced gene transcription. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13:588–599. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.1.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tamura T, Nagamura-Inoue T, Shmeltzer Z, Kuwata T, Ozato K. ICSBP directs bipotential myeloid progenitor cells to differentiate into mature macrophages. Immunity. 2000;13:155–165. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00016-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, et al. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87:307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang H, Lee CH, Qi C, Tailor P, Feng J, et al. IRF8 regulates B-cell lineage specification, commitment, and differentiation. Blood. 2008;112:4028–4038. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-129049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Power calculations for all study sets. All calculations were done using Researcher's toolkit's Statistical Power Calculator's two-tailed test with percentages by DSS (http://www.dssresearch.com/toolkit/spcalc/power_p2.asp) alpha = 5% for false positive probability, fixed MAFs calculated from the ORs of the combined effects and allele frequencies from the original study by De Jager et al. 2009. These results show that most of the individual sample sets have only moderate power to detect the association by themselves, but together have over 99% power to detect these variants with these effect sizes. The power for trios was not estimated.

(DOC)

Differences in rs17824933, rs1800693 and rs17445836 minor allele frequencies between population based controls. This table shows results for pair-wise associations between controls from different populations. We used the controls from populations on the left as cases and controls from the population above as controls. For French samples, healthy parents from case-parent trio samples were used as population controls. Uncorrected p-values are shown, but all values below p 0.000303 are significant (α = 0.05) after Bonferroni correction. Table S2a has the results for rs17624933 in CD6, Table S2b describes the results for rs1800693 in TNFRSF1A and Table S2c describes results for 17445836 61.5 kb from IRF8.

(DOC)

Ethics committee approvals for all cohorts. This study has been approved by appropriate local ethics committees as listed in this table by sample set. For each cohort we report the ethics committee or equivalent authority and the approval number.

(DOC)