Abstract

Introduced to minimize open vial wastage, single-dose vaccine vials require more storage space and therefore may affect vaccine supply chains (i.e., the series of steps and processes entailed to deliver vaccines from manufacturers to patients). We developed a computational model of Thailand’s Trang province vaccine supply chain to analyze the effects of switching from a ten-dose measles vaccine presentation to each of the following: a single-dose Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccine (which Thailand is currently considering) and a single-dose measles vaccine. While the Trang province vaccine supply chain would generally have enough storage and transport capacity to accommodate the switches, the added volume could push some locations’ storage and transport space utilization close to their limits. Single-dose vaccines would allow for more precise ordering and decrease open vial waste, but decrease reserves for unanticipated demand. Moreover, the added disposal and administration costs could far outweigh the costs saved from preventing open vial wastage.

Keywords: Measles Vaccine, Vaccine Supply Chain, Single-Dose

INTRODUCTION

Introduced to minimize open vial wastage, single-dose vaccine vials require more storage space and therefore may have untoward effects on vaccine supply chains (i.e., the series of steps and processes entailed to deliver vaccines from manufacturers to patients). Open vial wastage (from a heath care worker opening the vial to use a few doses but having to discard the remaining unused doses) and contamination risk (from having to repeatedly draw vaccine doses from one ten-dose vial) have long plagued traditional ten-dose vaccine presentations. A previous study demonstrated that using single-dose vaccine vial presentations can substantially decrease open vial wastage at the clinic level[3]. However, it remains unclear how introducing single-dose presentations may affect vaccine supply chains, an important consideration since vaccines must reach the population to be effective.

Discussions with members of Thailand’s National Health Security Office (NHSO) revealed their interest in replacing the currently used ten-dose measles vaccine (the first dose of a two-dose measles-containing vaccine series) with a single-dose presentation of a measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine[7–8], to decrease open vial wastage and decrease mumps and rubella incidence in young children[7–8]. Introducing new vaccine technologies to the Thailand Expanded Program on Immunization (EPI) first requires Ministry of Public Health (MoPH) approval with guidance from various policy makers, such as NHSO members[6]. However, policy makers may not always consider the impact of new vaccine technologies on the supply chain, as exemplified by the 2006 introduction of the rotavirus vaccine Latin America[4]. The two new rotavirus vaccines were too large for the existing vaccine supply chain and competed for space, thereby reducing the availability of both the rotavirus vaccine and other vaccines[5].

Members of the Vaccine Modeling Initiative (VMI), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, worked in conjunction with members of the Southern Vaccine Research Team (SVRT) from the Prince of Songkla University (PSU) in Thailand, to develop a computational model of the Southern Thailand vaccine supply chain and employed these models to simulate and determine the impacts on the supply chain of the following two scenarios:

Replacing the ten-dose measles vaccine given at 9–12 months, with single-dose the MMR vaccine.

Replacing the ten-dose measles vaccine given at 9–12 months with the single-dose measles single-antigen vaccine.

METHODS

Current EPI Thailand

Table 1 lists the vaccine characteristics of Thailand’s nine current EPI vaccines, as well as single-dose MMR and measles vaccines, which were obtained from the WHO’s Immunization Profile for Thailand[9].

Table 1.

Vaccine Characteristics for Model Inputs

| Vaccine | Dose(s) per person |

Dose(s) per vial |

Packed vol. per dose (cm3) |

Packed vol. of diluent per dose (cm3) |

Cold Storage Space |

Age of administration |

Route of Administration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) | 1 | 10 | 1.2 | 0.7 | Refrigerator | Birth | ID |

| Hepatitis B (HB) | 1 | 2 | 13.0 | none | Refrigerator | Birth | IM |

| Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis-Hepatitis B (DTP-HB) | 3 | 10 | 3.0 | none | Refrigerator | 2, 4 AND 6 months | IM |

| Oral polio vaccine (OPV) | 3 | 20 | 1.0 | none | Freezer† | 2, 4 AND 6 months | oral |

| Measles (M) | 1 | 10 | 3.5 | 4.0 | Refrigerator | 9–12 months | SC |

| Measles (M) | 1 | 1 | 9.3 | 20.0 | Refrigerator | 9–12 months | SC |

| Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) | 1 | 1 | 16.0 | 20.0 | Refrigerator | 9–12 months | SC |

| Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis (DTP) | 2 | 10 | 3.0 | none | Refrigerator | 1.5–2 years AND 4–5 years | IM |

| Japanese Encephalitis (JE) | 3 | 5 | 2.5 | 2.9 | Refrigerator | 1.5–2 years (x2) AND 2.5 –3 years | SC |

| Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) | 1 | 10 | 3.0 | 4.0 | Refrigerator | 1st grade | SC |

| Tetanus-Diphtheria (Td) | 3 | 10 | 3.0 | none | Refrigerator | Pregnant women (x2) AND Sixth grade | IM |

Abbreviations: ID (intradermal), IM (intramuscular), SC (subcutaneous).

Gray coloring indicates the vaccine characteristics of the single-dose vaccines that replaced the ten-dose measles vaccine of the EPI in our model. All vaccine characteristics were taken from the WHO Immunization Profile - Thailand [9]

The OPV vaccine is stored preferentially in the freezer; however, it has the ability to be stored in the refrigerator at administering locations.

Trang Province Vaccine Supply Chain

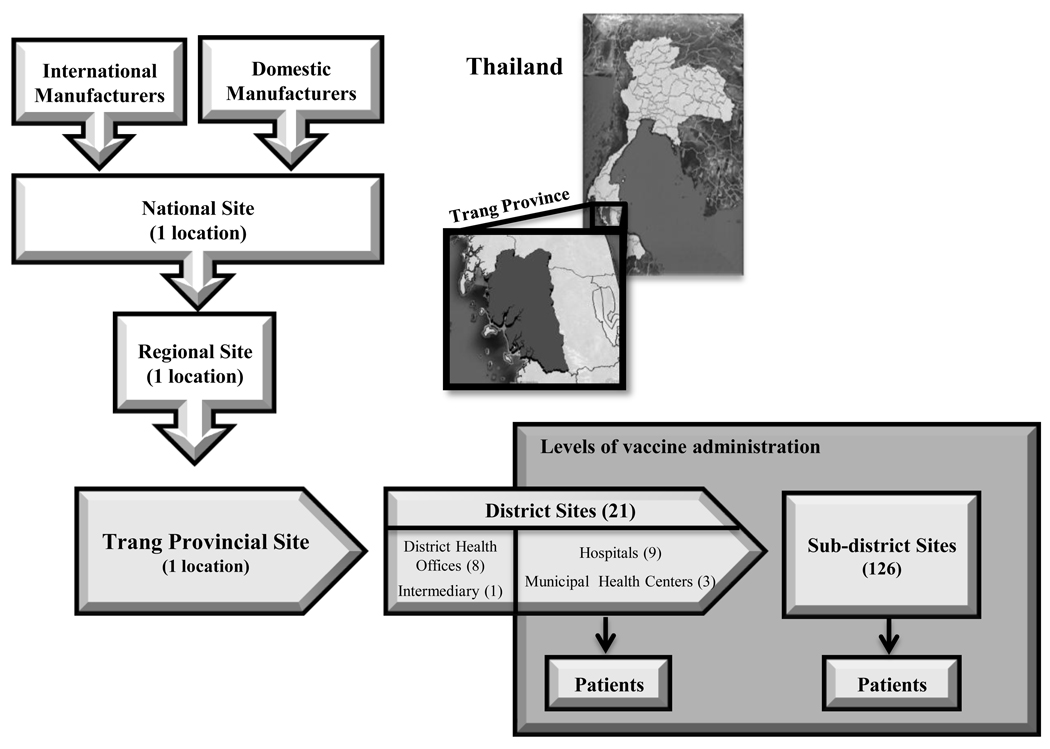

At the time of this study, vaccines flowed from manufacturers into the Thailand vaccine supply chain, consisting of five sequential levels. Figure 1 depicts the structure of the current vaccine flow from the manufactures through Trang province (one of seventy-six provinces in Thailand) branch of the Thailand vaccine supply chain. Data on the vaccine supply chain came from visits to locations at each level, surveys and interviews of managers at various locations, Thailand’s MoPH, and NHSO.

Figure 1.

Thailand vaccine supply chain network

Domestic and international manufacturers provide EPI vaccines to Thailand, either directly to the national site or through the Government Pharmaceutical Organization (GPO), which repackages vaccines and ships them to the national level site. The national store sorts vaccines into batches that are delivered to regional locations. The regional level sends refrigerated trucks every month to the Trang province site to deliver vaccines. The district level sites travel to the province monthly to obtain vaccine. At this point, vaccines are either administered (at hospitals and MHC’s) or stored (at some hospitals and DHOs) for the sub-district sites to pick up vaccines for administration. While the WHO recommends maintaining 25% buffer stocks at administering locations, vaccine supply chain managers and nurses in Trang province indicated that they base their order size on the previous month’s vaccine demand without maintaining any buffer stock.

Vaccine administration occurs weekly at district locations and monthly at sub-district locations. Arriving patients receive doses of the appropriate age-specified vaccines if they are available. Each vaccine vial has a specified lifetime based on their manufacturer provided shelf-lives. Wasted doses are doses that do not end up being administered to patients. Therefore, for each simulation run:

Estimates of population demand for each vaccine came from several sources. Trang province-specific population data from the 2000 Population and Housing Census inflated by a 1.45% annual growth rate including birth rate data generated the potential demand for each vaccination location at the district level proportional to the population density in each district[11]. Interviews with provincial health office staff suggested that 60% of children seek vaccination at the district and 40% at the sub-district levels. Therefore, we allocated 40% of the census-derived district populations evenly among a district’s sub-districts, for routine vaccinations. Newborn immunization occurs only at district level hospitals. Schools receive vaccines [MMR and Tetanus-diphtheria (Td)] from both district and sub-district locations. Age-specific census data generated the number of first and sixth grade students in each district.

Model Structure

Our model represented each location, refrigerator, freezer, and transport device in the vaccine supply chain. HERMES (Highly Extensible Resource for Modeling Event-driven Simulations) is a detailed dynamic, discrete-event simulation model of the processes, locations, equipment and vaccines in the vaccine supply chain, representing the flow of vaccines from the manufacturer to the patient. Development of HERMES took place in Python, using SimPy package features[13].

Each location’s available refrigerator and freezer capacity is based on actual measurements from site visits and verified by SVRT members: provincial level locations have 660L refrigerator (165L/refrigerator×4 devices) and 410L freezer capacity, DHOs have 750L refrigerator and 13L freezer capacity, district hospitals have 428L of refrigerator and 197L of freezer space, and sub-district sites each have 140L of refrigerator and 25L of freezer space. Since some of this space is occupied by other temperature-sensitive products (e.g., medicines or other biologicals), shelving, and ice packs, we assumed that only 85% of total capacity is available for EPI vaccines. Each refrigerator maintains a temperature of 2°C to 8°C and each freezer a temperature of −15°C to −25°C. Each vaccine’s temperature profile governs its assignment to either a freezer or refrigerator (e.g., non-freezable vaccines cannot be stored in the freezer).

The following equation determines the current vaccine inventory (i.e., number of vaccines currently stored) in a refrigerator or freezer:

The current vaccine inventory cannot exceed that refrigerator’s, freezer’s, or cold room’s storage capacity. Vaccine shipments from location-to-location occur at defined frequencies specific to transportation routes and cannot contain more vaccines than the transport vehicles’ specified effective storage capacity. Transportation vehicles include a 4×4 truck (cold capacity: 9,187.5L) from the regional to provincial level, a cold box (cold capacity: 34.9L) from the district to the provincial level, and a vaccine carrier (cold capacity: 4.6L) carried by a public health worker to their sub-district location.

Vaccine loss transpires via:

Switching Measles Vaccine Presentations

Our experiments examined the following scenarios:

Switching the current first dose of the ten-dose measles vaccine presentation with a single-dose MMR presentation.

Switching the current first dose of the ten-dose measles vaccine presentation with a single-dose measles single-antigen presentation.

Model Output Measures

For each simulation, the following equation calculated the vaccine availability (i.e., percentage of children arriving at a location for vaccination, for which the desired vaccine is in stock) for each vaccine at each vaccine administration location across a year:

The model also tracked transport and storage utilization (i.e., percentage of space occupied by vaccines) at each location and along each route throughout each experiment.

The following equations calculated the net cost difference, in US$, from the switch [1, 3]:

Costvaccine administration=(Costvaccine/dose×doses/vial×patients)+(Costinjection syringe×patients)+(Costreconstitution syringe×vials opened)

Costwasted doses=Costper dose×wasted doses/location

Costwaste disposal=(Costwaste disposal/kilogram (g)×(Weightopened vials(g)+Weightreconstitution syringes(g)+Weightinjection syringes(g)))

The WHO Vaccine Volume Calculator provided the following input values: $0.25/dose (cost of ten-dose measles vaccine), $1.98/dose (single-dose MMR), $0.94/dose (single-dose measles), $0.06 (reconstitution syringe), $0.07 (administration syringe), 6.83g (weight of reconstitution syringe) and 5.84g (administration syringe)[1]. Direct measurements provided weights of differently-sized empty vials: 3.63g (ten-dose vial) and 1.76g (single-dose vial). An average of low and high costs of disposal ($0.00173 – $0.00907) from a medical waste disposal assessment in a neighboring Southeast Asian country provided waste disposal costs ($0.0059/gram)[15].

Sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses systematically ranged the following parameter values: inventory loss rate (range: 0%–2%), shipping loss rate (range: 0%–5%), cost of vaccines, cost of waste disposal and proportion of school serviced by the district versus the sub-district (range: 20%–80%). Additional scenarios varied population demand from a static monthly distribution (i.e., number of vaccine recipients in a given month is fixed based on projected population estimates and does not fluctuate from month to month) to a dynamic monthly distribution [i.e., number of vaccine recipients in a given month draws from a Poisson distribution with a mean of the previous months number of vaccine recipients (λ)].

RESULTS

Sensitivity analyses demonstrated that varying the patient demand (static versus dynamic) and shipping and inventory loss did not notably affect results. Varying the proportion of school-aged vaccines that come from district versus sub-district levels (20%–80%) only affected transport utilization from district to sub-district by less than +/−10% and never exceeded 60% of available capacity. Therefore, the following results report from scenarios representing a dynamic demand, 1% inventory and shipping loss and schools serviced by districts and sub-districts evenly (50% serviced at the district and 50% serviced at the sub district).

Impact on Transport

Although all transport routes had enough existing capacity to accommodate the switch to a MMR single-dose or measles single-dose vaccine, the increased volume from the switch decreased the amount of transport space available for other temperature-sensitive products. Table 2 lists the transport capacity utilization rates associated with each formulation of the first-dose measles vaccine. While transport from the regional to provincial store had ample capacity (utilizing only 3.8% for the ten-dose measles, 4.3% for the MMR single-dose, and 4.0% for the measles single-dose vaccines) and was relatively unaffected by the switch, transport space utilization from the province-to-district levels increased from a median of 30.9% (range: 6.9%–105.5%) to 37.6% (range: 8.7%–117.2%) for the MMR single-dose and to 33.5% (range: 7.5%–111.1%) for the measles single-dose formulation. Between provincial and district levels, transport capacity along only 1 of 22 routes required over 100% of the available space for both the ten and single-dose measles vaccine scenarios, and only 2 of 22 devices required more space than available for the single-dose MMR vaccine scenario. Between district and sub-district levels, transport utilization rates increased from a median of 42.7% (range: 22.9%–85.4%) to 49.9% (range: 24.0%–106.9%) for the MMR single-dose and to 45.3% (range: 23.5%–97.5%) for the measles single-dose vaccines.

Table 2.

Median Capacity Utilization Rates

| Ten-dose Measles vaccine |

Single-dose MMR vaccine |

Single-dose Measles vaccine |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Transport space utilization | |||

| Regional to Provincial (1 route) | 3.8% | 4.3% | 4.0% |

| Provincial to District | 30.9% (range: 6.9%–105.5%)* |

37.6% (range: 8.7%–117.2%)** |

33.5% (range: 7.5%–111.1%)* |

| District to Sub-district | 42.7% (range: 22.9%–85.4%) |

49.9% (range: 24.0%–106.9%)* |

45.3% (range: 23.5%–97.5%) |

| Storage space utilization | |||

| Regional (1 site) | 28.2% | 41.9% | 35.0% |

| Provincial (1 site) | 29.2% | 33.7% | 31.0% |

| District | 2.2% (range: 0.7%–4.5%) |

2.8% (range: 0.7% – 5.1%) |

2.6% (range: 0.7%–4.8%) |

| Sub-district | 0.9% (range: 0.4%–1.6%) |

1.1% (range: 0.6%–2.4%) |

1.1% (range: 0.6%–2.3%) |

Only one transport device would need to utilize more than 100% of the available space

Only two transport devices would need to utilize more than 100% of the available space

Impact on Storage Facilities

Table 2 also shows the impact of the switch on storage space utilization rates. Thailand has ample storage space for the current EPI vaccines and a switch to either single-dose MMR or measles vaccines. Even after the switch to either formulation (MMR or measles single-dose), neither regional nor provincial sites exceeded 42%, and none of the district or sub-district sites exceeded 6% of their available storage capacity.

Impact on Vaccine Administration

After the switch, the vaccine availability for the first measles dose decreased from a median of 94.4% (range: 90.8%–98.9%) to 92.4% (range: 88.2%–98.7%) following the switch to the single-dose MMR vaccine and decreased to 91.9% (range: 87.9%–98.5%) following the switch to the single-dose measles, at the district levels. A much larger impact was seen at the sub-district level where the vaccine availability for the first-dose measles vaccine decreased from a median of 95.6% (range: 86.2%–100%) to 83.4% (range: 72.7%–92.9%) following the switch to the single-dose MMR and decreased to 83.6% (range: 73.4%–91.7%) following the switch to a single-dose measles vaccine. The availability of other EPI vaccines did not change substantially, changing slightly from an average of 95.8% for the ten-dose measles vaccine scenario to 95.6% for the single-dose MMR vaccine scenario and to 95.7% for the single-dose measles vaccine scenario. The switch increased the total number of measles containing vaccine vials in the vaccine supply chain in a given year from an average of 17,440 (ten-dose measles vials) to 119,261 (single-dose MMR vials) or 118,622 (single-dose measles vials). The greater the number of vials, the greater the risk of vial breakage, which increased the doses lost from vial breakage in our simulations from 1,760 doses to 2,502 doses (MMR single-dose) or 2,497 doses (measles single-dose).

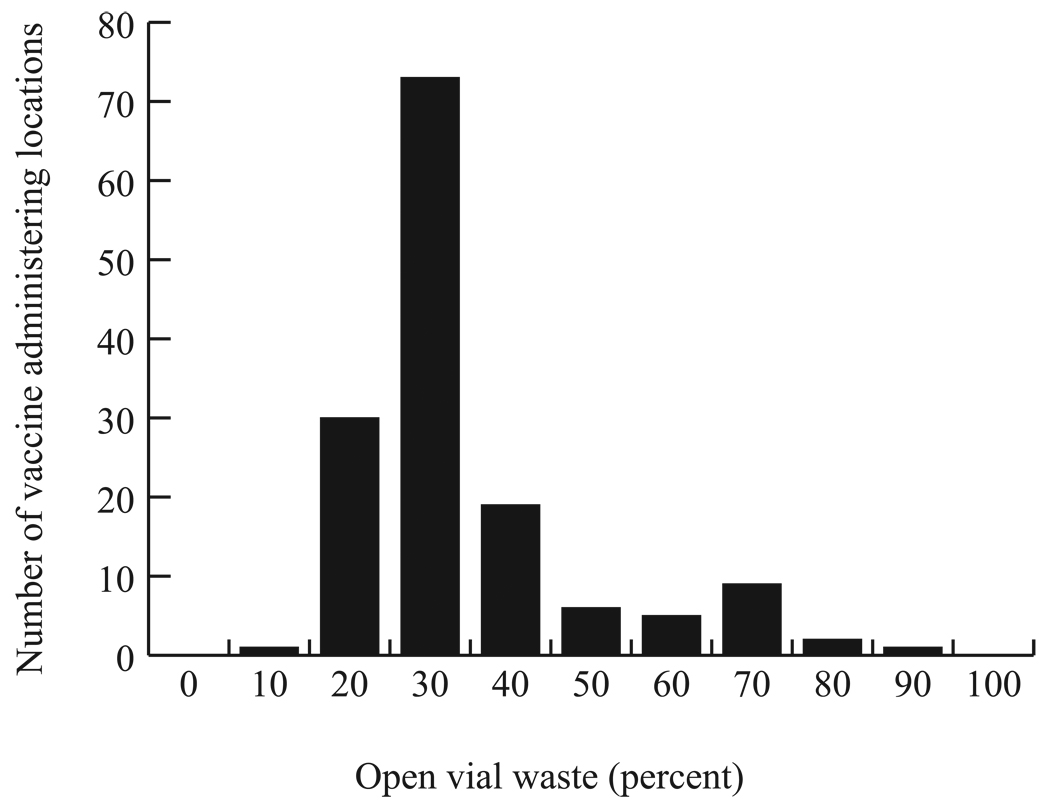

Switching from a ten-dose to a single-dose presentation decreased open vial wastage. Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of open vial waste from the ten-dose measles vaccine across vaccine administering locations, the majority of which could be eliminated by a switch to a single-dose presentation.

Figure 2.

Frequency Distribution of Open Vial Waste from the Ten-dose Measles Vaccine by Administration Locations across a Year

Cost Impact

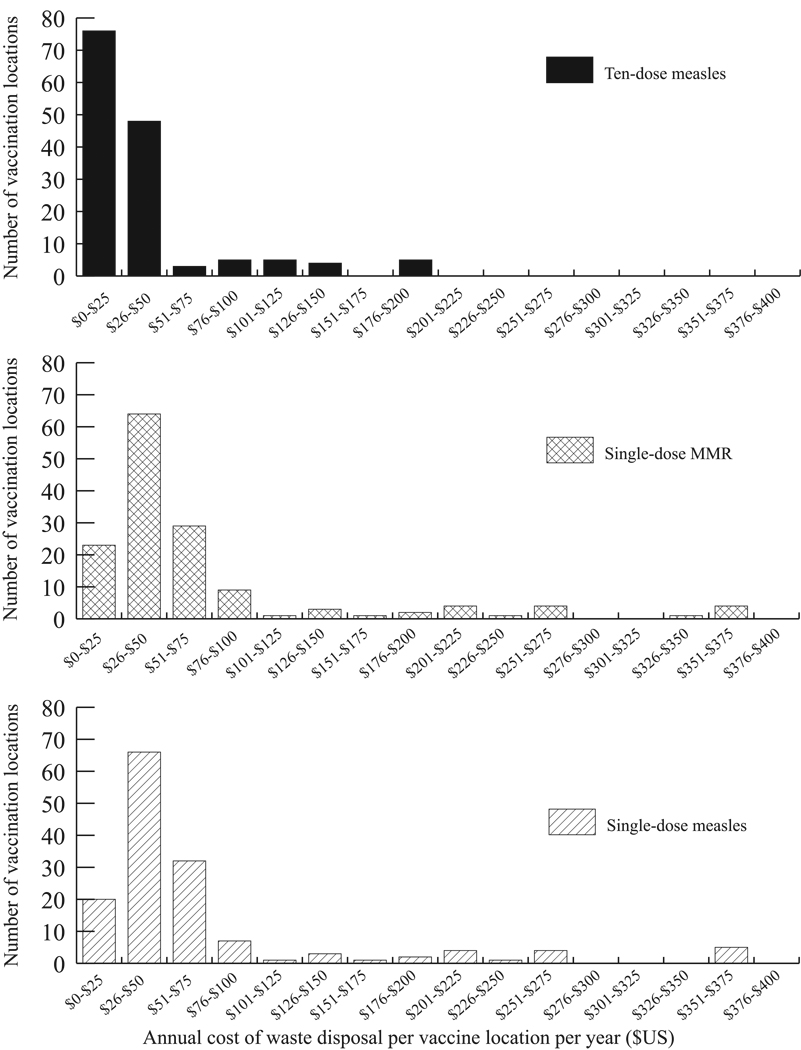

Switching to either single-dose vial would increase medical waste and subsequent medical waste disposal costs would outweigh cost savings from reducing open vial waste, resulting in net additional costs. For the ten-dose measles vaccine, 16% of the total cost was attributed to open vial waste, 8% to waste disposal costs and 75% to vaccine administration. For the single-dose MMR, the proportions were 0%, 4%, and 96%. For the single-dose measles, the proportions were 0%, 7%, and 93%. The switch to a single-dose presentation increased the number of vials (and therefore reconstitution syringes) required from 17,440 to 119,261 (MMR single-dose) and 118,622 (measles single-dose) but decreased the number of injection syringes (as a result from the decrease in the number of children who received vaccine) from 128,235 to 119,261 (MMR single-dose) and 118,622 (measles single-dose). The increased in medical waste resulted in an increase from US$5,889 to US$10,183 (single-dose MMR) or US$10,238 (single-dose measles). Moreover, the higher relative cost of the single-dose vial presentation increased the vaccine administration cost from US$52,925 to US$251,641 (single-dose MMR) and US$127,281 (single-dose measles). The cost of wasted doses from the ten-dose measles vial presentation was US$11,357; whereas the single-dose vials carry no open vial waste cost. For all of Trang province, the total costs of switching were US$70,171 (US$501/vaccination location, US$0.55/vaccinated child and US$0.52/arriving child) for the ten-dose measles vaccine scenario, US$261,878 (US$1,871/vaccination location, US$2.20/vaccinated child, and US$1.03/arriving child) for the single-dose MMR vaccine scenario, and US$137,464 (US$982/vaccination location, US$1.16/vaccinated child, and US$1.95/arriving child) for the single-dose measles vaccine scenario. Figure 3 shows that making either switch would increase the annual waste disposal costs at many locations. As Trang province is just one of 76 provinces in Thailand, switching to either single-dose measles or MMR vaccine presentations from the ten-dose measles vaccine could result in significant costs to the EPI.

Figure 3.

Frequency Distribution of Waste Disposal Costs for Ten-dose Measles, Single-dose Measles, and Single-dose MMR Vaccines by Vaccine Administering Site

Sensitivity analyses showed the single-dose presentations to be consistently more costly than the ten-dose presentation as long as the cost of either of the single-dose vaccines is >$0.37/dose (>$0.50 if one eliminates the cost of all injection and reconstitution syringes in the single-dose presentations, e.g., pre-packaged integrated uni-dose injection devices). Results were robust to changes in the costs of waste disposal or syringes. For example, even a ten-fold decrease in the cost of waste disposal (from $5.737 to $0.5737/gram) resulted in only a minor decrease in additional cost associated with a switch from the ten-dose to the single-dose MMR (from $191,707 to $187,794) or to a single-dose measles (from $67,293 to $63,429).

DISCUSSION

Results suggest that while the Trang province vaccine supply chain would generally have enough storage and transport capacity to accommodate the intended switch from the ten-dose measles vaccine to the single-dose MMR vaccine or a single-dose formulation of the measles vaccine, the added volume could push storage and transport space utilization close to their limits at some locations. Reducing (and in some cases eliminating) the buffer capacity provided by a ten-dose vial, could jeopardize the vaccine supply chain's ability to handle events that would require additional cold capacity (e.g., introductions of new vaccines, breakdowns in transport vehicles, refrigerator failure, or unexpected increases in population demand). While replacing the ten-dose measles vaccine with any single-dose measles containing vaccine would eliminate open vial waste, there would be an added expense associated with the increased waste disposal costs from the increase in vials. The increase in the total number of vials in the vaccine supply chain would also increase the number of vaccine vials that could be broken.

Although single-dose vaccines would allow for more exact ordering and decrease open vial waste, this practice may not leave enough additional vaccine doses available in case demand is greater than anticipated, which could limit the number of patients able to be vaccinated. This phenomenon was seen in our results when switching from the ten-dose to either single-dose vaccine. Vaccine availability decreased for children 9–12 months, despite enough storage and transport space in the vaccine supply chain, due to the ordering and buffer-stock policies that are in place and more suited for multi-dose vials. For example, if the anticipated demand is 14, a vaccination location may order either 2 vials of the ten-dose vial or 14 vials of the single-dose vial. In this scenario, a 17 patient demand would result in 3 patients not getting vaccinated if single-dose vials had been ordered, but all patients vaccinated if ten-dose vials had been ordered. This finding is a very important consideration if an ordering policy that does not include buffer-stock remains in place, as it results in decreased vaccine availability. Therefore, when switching to a single-dose vaccine, one may want to consider revising buffer-stock levels and the reorder point policy.

When considering the switch from a ten-dose measles vial to a single-dose, despite the potential for single-dose vials to eliminate open vial wastage, the added disposal and administration costs could far outweigh the open vial wastage prevention cost savings. These findings highlight the importance of considering medical waste when introducing a new vaccine presentation or vaccine technology. In fact, while our costs of medical waste drew from previous studies, they may in fact underestimate this cost. Improper waste disposal could lead to blood borne pathogen exposure. Effective systems to safely remove medical waste and mitigate infection often require sorting or separating different kinds of waste product, treating contaminated waste material, and transporting the waste material to a disposal facility where it will either be buried or incinerated [16].

Of course, rather than advocate against the use of single-dose vaccine presentations, our findings help elucidate some of the operational and economic repercussions of switching from ten-dose to single-dose vaccine presentations. Single-dose presentations offer certain benefits not captured by our study. The single-dose presentation may allow for more consistent dose-size administration, reduce the risk of cross-contamination from repeated entry by needles to draw vaccine doses into administration syringes, and provide more convenience to health care workers. Eliminating open vial wastage may also alleviate the need for policies to minimize open vial wastage (e.g., planning when and when not to open new vials). Additionally, switching from the ten-dose single-antigen measles vaccine to the single-dose MMR vaccine provides further protection against mumps and rubella, which is of great interest in Thailand, therefore, some changes to vaccine presentations in EPIs should be more than cost-driven.

Our study demonstrates how models can help identify effects of decisions not immediately evident. Models have long aided decision making in many other industries, such as meteorology [17], manufacturing [18], transportation [19], aerospace [20], and finance [21], and sports and rehabilitation [22]. By contrast, their use to date in public health has not been as extensive [23–25]. Models have assisted responses to the spread of infectious disease such as the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic and health-care associated infections [26–30], but much of their potential remains untapped.

Limitations

By definition, all models are simplified representations of real life and therefore cannot capture every potential factor, event, or outcome [31–32]. The model is based on data up to June 2010 and may not represent changes that may occur in the future. Actual demand may vary from our estimated demand, although sensitivity analyses demonstrated the effects of altering demand. Our model assumed that all diluents were matched correctly with the appropriate vaccine, and therefore do not consider adverse events following immunization that would result from reconstituting vaccines with non-matching diluents. Due to the paucity of available data on vaccine administration frequency at district level sites, immunization session frequency was extrapolated from a sample across the district level. Constructing our model involved substantial data collection from a wide variety of sources including records and interviews at different locations. Also, a minority of patients may seek vaccination from outside the EPI vaccine supply chain. As a result, parameter values may vary in accuracy and reliability, although sensitivity analyses demonstrated that model outcomes are robust under a wide variety of circumstances.

Conclusions

While the Trang province vaccine supply chain would generally have enough storage and transport capacity to accommodate the switch from the ten-dose measles vaccine to the single-dose measles or MMR vaccines, the added volume could push storage and transport space utilization close to their limits at some locations. Moreover, replacing ten-dose vials with either single-dose vial presentation would increase the total number of vials in the vaccine supply chain, thereby increasing the number of vaccine vials that could be broken. Additionally, the cost of disposal and administration of single-dose vials could outweigh the benefit provided by eliminating open vial waste. Our study presented a unique unanticipated finding; the policy of ordering the exact mean of patients arriving in the prior month for the current month without buffer can play a major factor in the ability to supply all patients with the required vaccination. Utilizing single-dose vials eliminated an inherent buffer provided by a ten-dose vial, and these effects should be considered before switching any vaccine type from a ten-dose to a single-dose presentation.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Vaccine Modeling Initiative (VMI), funded by the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation and the National Institute of General Medical Sciences Models of Infectious Disease Agent Study (MIDAS) grant 1U54GM088491-0109. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

We would like to acknowledge members of the SVRT: Ms. Chayanit Phetcharat, Mr. Somkit Phetchatree, Ms.Thunwarat Untrichan, Ms. Ratana Yamacharoen and Ms. Phornwarin Rianrungrot for their role in data acquisition.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Vaccine volume calculator. [cited 2010 September];2009 Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_delivery/systems_policy/logistics/en/index4.html.

- 2.Chunsuttiwat S, Biggs BA, Maynard JE, Thammapormpilas P, M OP. Comparative evaluation of a combined DTP-HB vaccine in the EPI in Chiangrai Province, Thailand. Vaccine. 2002 Dec 13;21(3–4):188–193. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(02)00461-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee BY, Norman BA, Assi TM, Chen SI, Bailey RR, Rajgopal J, Brown ST, Wiringa AE, Burke DS. Single versus multi-dose vaccine vials: an economic computational model. Vaccine. 2010 Jul 19;28(32):5292–5300. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lee BY, Burke DS. Constructing target product profiles (TPPs) to help vaccines overcome post-approval obstacles. Vaccine. 2010;28(16):2806–2809. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.09.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Oliveira LH, Danovaro-Holliday MC, Matus CR, Andrus JK. Rotavirus vaccine introduction in the Americas: progress and lessons learned. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2008 Apr;7(3):345–353. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.3.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muangchana C, Thamapornpilas P, Karnkawinpong O. Immunization policy development in Thailand: the role of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practice. Vaccine. 2010 Apr 19;28 Suppl 1:A104–A109. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karnjanapiboonwong A, Chaifoo W, Khempet T, Darapong C, Jiraphongsa C, Iamsirithaworn S. Thailand: Field Epidemiology Training Program, Thailand Pangmapha Hospital, Maehongson; 2010. MMR Vaccine Effectiveness for Preventing Mumps in Outbreak at a Rural School, Northern Thailand, August 2009 –February 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tharmaphornpilas P, Yoocharean P, Rasdjarmrearnsook AO, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y. Seroprevalence of antibodies to measles, mumps, and rubella among Thai population: evaluation of measles/MMR immunization programme. J Health Popul Nutr. 2009 Feb;27(1):80–86. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v27i1.3320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Immunization Profile - Thailand. [cited 2011 January];2010 December 15; 2010 Available from: http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/en/globalsummary/countryprofileselect.cfm.

- 10.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. WHO Policy Statement: The use of opened multi-dose vials of vaccine in subsequent immunization sessions, in Department of Vaccines and Biologicals. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bangkok: National Statistics Office of Thailand; 2000. Population and Housing Census. [Google Scholar]

- 12.IBM. C and C++ Compilers. [cited 2010];Software. 2010 Available from: http://www-01.ibm.com/software/awdtools/xlcpp/ [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller K, Vignaux T. [cited 2011 Feb 7];SimPy: Simulating Systems in Python. 2003 Available from: http://onlamp.com/pub/a/python/2003/02/27/simpy.html?page=2. [Google Scholar]

- 14.World Health Organization. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. WHO Policy Statement: The use of opened multi-dose vials of vaccine in subsequent immunization sessions. [Google Scholar]

- 15.PATH. Medical Waste Management for Primary Health Centers in Indonesia. Seattle: PATH; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO. Immunization safety: Waste management. [cited 2010 4 November];2010 Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization_safety/waste_management/en/

- 17.Klingberg J, Danielsson H, Simpson D, Pleijel H. Comparison of modelled and measured ozone concentrations and meteorology for a site in south-west Sweden: implications for ozone uptake calculations. Environ Pollut. 2008 Sep;155(1):99–111. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2007.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee JH, Kim CO. Multi-agent systems applications in manufacturing systems and supply chain management : a review paper. London: Royaume-Uni: Taylor & Amp; Francis; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borndorfer R, Lobel A, Weider S. A bundle method for integrated multi-depot vehicle and duty scheduling in public transit. Computer-aided Systems in Public Transport. 2008;600(Part 1):3–21. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moormann D, Mosterman JP, Looye G. Paris, FRANCE: Elsevier; 1999. Object-oriented computational model building of aircraft flight dynamics and systems. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fouque J-P, Papanicolaou G, Sircar K. Financial Modeling in a Fast Mean-Reverting Stochastic Volatility Environment. Asia-Pacific Financial Markets. 1999;6(1):37–48. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Neptune RR. Computer modeling and simulation of human movement. Applications in sport and rehabilitation. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2000 May;11(2):417–434. viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Trochim WM, Cabrera DA, Milstein B, Gallagher RS, Leischow SJ. Practical challenges of systems thinking and modeling in public health. Am J Public Health. 2006 Mar;96(3):538–546. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.066001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leischow SJ, Milstein B. Systems thinking and modeling for public health practice. Am J Public Health. 2006 Mar;96(3):403–405. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.082842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Epstein JM. Generative social science: Studies in agent-based computational modeling. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cooley P, Lee BY, Brown S, Cajka J, Chasteen B, Ganapathi L, et al. Protecting health care workers: a pandemic simulation based on Allegheny County. Influenza Other Respi Viruses. 2010 Mar;4(2):61–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00122.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee BY, Brown ST, Cooley P, Grefenstette JJ, Zimmerman RK, Zimmer SM, et al. Vaccination deep into a pandemic wave potential mechanisms for a "third wave" and the impact of vaccination. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Nov;39(5):e21–e29. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee BY, Brown ST, Cooley P, Potter MA, Wheaton WD, Voorhees RE, et al. Simulating school closure strategies to mitigate an influenza epidemic. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2010 May–Jun;16(3):252–261. doi: 10.1097/PHH.0b013e3181ce594e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee BY, Brown ST, Cooley PC, Zimmerman RK, Wheaton WD, Zimmer SM, et al. A computer simulation of employee vaccination to mitigate an influenza epidemic. Am J Prev Med. 2010 Mar;38(3):247–257. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2009.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee BY, Brown ST, Korch GW, Cooley PC, Zimmerman RK, Wheaton WD, et al. A computer simulation of vaccine prioritization, allocation, and rationing during the 2009 H1N1 influenza pandemic. Vaccine. 2010 Jul 12;28(31):4875–4879. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee BY, Biggerstaff BJ. Screening the United States blood supply for West Nile Virus: a question of blood, dollars, and sense. PLoS Med. 2006 Feb;3(2):e99. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee BY. Digital decision making: computer models and antibiotic prescribing in the twenty-first century. Clin Infect Dis. 2008 Apr 15;46(8):1139–1141. doi: 10.1086/529441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]