Abstract

Mucopolysaccharidosis-I (MPS-I) is an inherited deficiency of α-L-iduronidase (IdU) that causes lysosomal accumulation of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) in a variety of parenchymal cell types and connective tissues. The fundamental link between genetic mutation and tissue GAG accumulation is clear, but relatively little attention has been given to the morphology or pathogenesis of associated lesions, particularly those affecting the vascular system. The terminal parietal branches of the abdominal aorta were examined from a colony of dogs homozygous (MPS-I affected) or heterozygous (unaffected carrier) for an IdU mutation that eliminated all enzyme activity, and in affected animals treated with human recombinant IdU. High resolution computed tomography showed that vascular wall thickenings occurred in affected animals near branch points, and associated with low endothelial shear stress. Histologically these asymmetric “plaques” entailed extensive intimal thickening with disruption of the internal elastic lamina, occluding more than 50% of the vascular lumen in some cases. Immunohistochemistry was used to demonstrate that areas of sclerosis contained foamy (GAG laden) macrophages, fibroblasts and smooth muscle cells with loss of overlying endothelial basement membrane and claudin-5 expression. Lesions contained scattered cells expressing nuclear NF-κβ (p65), increased fibronectin and transforming growth factor β-1 signaling (with nuclear Smad3 accumulation) in comparison to unaffected vessels. Intimal lesion development and morphology was improved by intravenous recombinant enzyme treatment, particularly with immune tolerance to this exogenous protein. The progressive sclerotic vasculopathy of MPS-I shares some morphologic and molecular similarities to atherosclerosis, including formation in areas of low shear stress near branch points, and can be reduced or inhibited by intravenous administration of recombinant IdU.

Keywords: atherosclerosis, mucopolysaccharidosis, pathogenesis, lysosomal storage disease, enzyme replacement therapy, vasculopathy

Lysosomal storage diseases are a heterogeneous group of heritable conditions associated with genetic mutations resulting in loss of lysosomal enzyme activity. The mucopolysaccharidoses are a subset of these storage disorders caused by deficiency of an enzyme involved in the breakdown of glycosaminoglycans (GAG). The resultant accumulation of GAG in parenchymal cells and connective tissues is associated with a progressive, debilitating, multisystem disease and typically premature death.1, 2

Mucopolysaccharidosis-I (MPS-I) is an autosomal recessive disease resulting from the deficiency of α-L-iduronidase (IdU) and consequent accumulation of dermatan sulfate and heparan sulfate GAG.2 Over 100 IdU mutations have been described in affected individuals and, depending on the extent to which this reduces IdU activity, clinical manifestations range from severe (Hurler syndrome) to mild (Scheie syndrome) or an intermediate (Hurler/Scheie) phenotype.2 Children with Hurler disease exhibit early onset facial and skeletal deformities, mental retardation and may die before 10 years of age from cardiac valvular and/or respiratory failure. In milder forms individuals can survive into their fourth and fifth decades with progressive musculoskeletal problems. Effective treatment of patients with MPS-I currently includes administration of recombinant IdU protein to replace defective enzyme function.3, 4 FDA approval for this treatment in 2003 was based in part on preclinical testing in a canine model of MPS-I.5–7 This outbred family of dogs carries a G to A point mutation in the donor splice site of intron 1 that causes retention of intron 1 in the RNA and a premature termination codon at the exon-intron junction.8 Heterozygous carriers produce adequate levels of enzyme from the wild-type allele and are unaffected, as are human carriers. Homozygotes completely lack IdU activity and exhibit clinicopathologic changes similar to the intermediate form of the disease in humans.5–7

MPS-I and other forms of storage disease are rare and consequently have not been studied as closely as more prevalent diseases such as atherosclerosis. Most of the work in MPS-I has been, appropriately, directed towards therapeutic intervention and very little is known about its pathogenesis beyond characterization of genetic mutations and associated accumulation of GAG in multiple tissues and cell types. The relationship between accumulation of this storage material and progressive multisystem disease has only been addressed in a few studies.9–13 Although it may be logical to assume that intracellular accumulation of GAG results in cell death, this has not been established for any of the affected cell types in MPS-I and does not explain all pathologic changes. Abnormal lysosomal GAG accumulation affects GAG content and/or related biochemical structures in other intra- or extracellular locations and may increase or otherwise alter cell function in a cell specific or microenvironment-dependent manner,14 but the specific perturbations have yet to be determined in MPS-I.

The vascular system is known to be affected in humans and dogs with MPS-I but, as with other organs, the morphology and pathogenesis of these changes has received limited study.6, 11, 12, 15–20 In this paper we provide new details about the morphology and potential contributing pathologic mechanisms involved in the development of vascular lesions in dogs with MPS-I, and examine the affects of recombinant IdU therapy on lesion morphology.

Materials and Methods

The canine MPS-I colony was founded at the University of Tennessee College of in Knoxville7 and subsequently transferred to the Harbor Research Institute, University of California Los Angeles Medical School, an AAALAC accredited facility. All studies were approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use committees. Tissues used in the current report were derived prospectively and retrospectively from preclinical trials, which have been reported in greater detail elsewhere.21–27 In short, dogs were treated intravenously and/or intrathecally with human recombinant IdU (BioMarin, Novato, CA) using protocols that included low and high IV doses (0.6 and 2 mg/kg), varying ages of treatment initiation (1 week to > 1 year of age) and length of treatment (weeks to > 1 yr), continuous vs periodic (once/week to every 3 months) therapy, and with preinduction of immune tolerance. The null mutation in homozygous dogs completely eliminates IdU protein expression, as is the case in many Hurler patients, and administration of recombinant enzyme elicits a robust immune response. We have found that pharmacologic induction of immune tolerance in these dogs enhances the beneficial effects of recombinant enzyme therapy,24 and that initiation of IV treatment shortly after birth also results in immune tolerance to the enzyme.27 Tissue samples for pathologic evaluation were obtained immediately following euthanasia and fixed in 10% (v/v) neutral buffered formalin. For immunohistochemical analysis the tissues were rinsed after 18 hours in fixative and held in 70% ethanol until they could be processed into paraffin for histologic sectioning. Routine hematoxylin and eosin staining was performed on all sections in order to compare the morphology of affected and unaffected vessels.

Histochemical staining

Select histologic sections were stained with a modified Movat’s pentachrome stain as previously described.28, 29 In these sections, elastic fibers are black, smooth muscle is red, collagen yellow, nuclei purple, and GAG appear blue-green. Masson trichrome stain was also used to highlight collagen (deep blue) and Alcian blue for acid mucopolysaccharides.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was performed by the University of Tennessee College of Veterinary Medicine Immunohistochemistry Laboratory as previously described.30 Primary antibodies (Supplementary online information) were applied for 30 min at room temperature and localized in situ with a horse radish peroxidase-labeled polymer (Envision+ System, Dako, Carpinteria, CA) and the chromogen 3,3′-diaminobenzidine. Slides incubated with Universal Negative Control (Dako), in place of primary antibody, served as controls. Positive controls included endogenous vascular proteins (α-smooth muscle actin, laminin, type IV collagen, claudin-5), canine granulation tissue (fibronectin, transforming growth factor (TGF) β-1, Smad3, cyclooxygenase-2], or sections of canine intestine and mesenteric lymph node (CD18, lysozyme, proliferating cell nuclear antigen, nuclear factor (NF)-κβ p65, activated caspase-3).

CT Imaging

The caudal thoracic to sublumbar abdominal aorta and proximal segments of all branches from affected dogs were imaged using a microCAT II + SPECT imaging system (Siemens Preclinical Solutions, Knoxville, TN). Aortas were flushed after removal, fixed in formalin, and evacuated with pressurized air before imaging. The vessels and adherent surrounding soft tissues were imaged by CT using an X-ray voltage biased to 80 kVp with a 500 μA anode current, the full 90 mm × 60 mm field of view was used and the data were binned 4 × 4. A series of 360, 1-degree projections were collected using an exposure time of 475 msec per projection. The data were reconstructed in real-time using an implementation of the Feldkamp filtered back-projection algorithm onto a 512 × 512 × 768 matrix with isotropic 0.077 mm voxels. These data were visualized and evaluated in 3-dimensions using the Amira software package (Visage Imaging, Andover, MA).

RESULTS

Vascular Pathology

Most of the affected dogs in this study were between 18–24 months of age (mean 22 months) at necropsy (Table 1) and both males and females were included. There were no obvious differences in vascular lesions between genders, but direct anatomic comparisons and quantification were not attempted. All vascular lesions were arterial; no striking morphologic changes were identified in the venous system. At necropsy macroscopic vascular changes were obvious only in the proximal aorta of affected dogs, where there was rugose intimal thickening and nodular plaques projecting from the wall behind semilunar valve leaflets (Supplemental information, Figure). Two dogs had a discrete 0.5–3 cm diameter, round to oval aneurysmal defect in the outer convex aspect of the aortic wall at or just beyond the arch (17 month old untreated; 23 month old from low dose, tolerant group). Smooth muscle tunics in these areas were replaced by disorganized fibrous or chondroid tissue with bone formation and macrophages containing hemosiderin.

Table 1.

Ages of MPS-I affected dogs and non-affected carriers (normal control) at necropsy. All ages in months.

| Group | Number | Mean Age | Age Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Untreated | 4 | 16.5 | 13–18 |

| Unaffected Carriers | 2 | - | 15, 78 |

| Low Dose, Non-tolerant | 11 | 28.7 | 13–40 |

| Low Dose, Tolerant | 9 | 18.6 | 13–25 |

| Low Dose, From Birth | 2 | - | 17, 18 |

| High Dose, Non-tolerant | 6 | 17.5 | 13–31 |

| High Dose, Tolerant | 3 | 18 | 17–20 |

| High Dose, From Birth | 2 | - | 13, 13 |

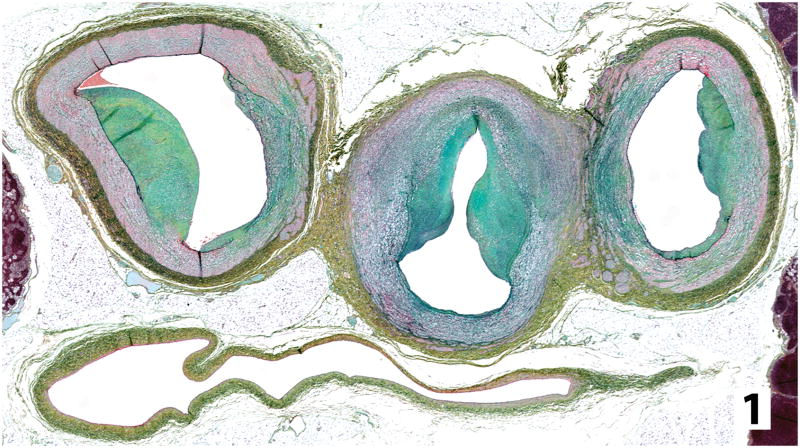

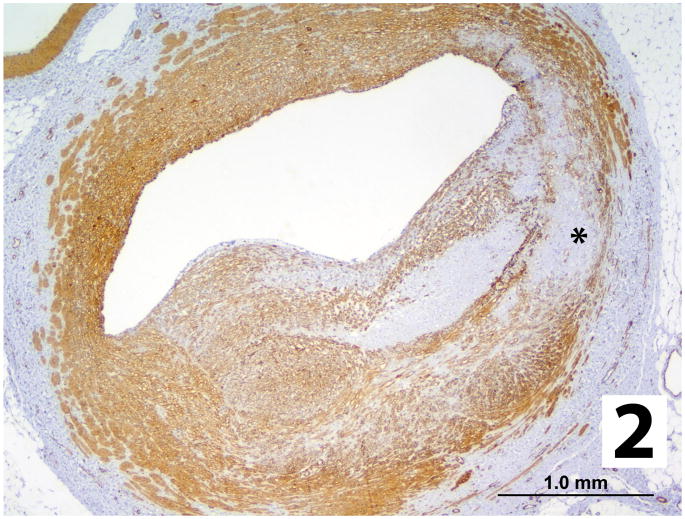

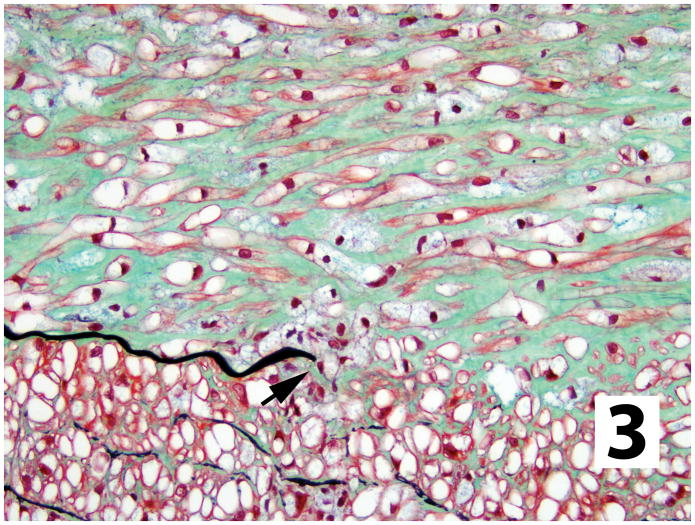

Histologically the proximal aorta was characterized by severe distortion of mural architecture with sclerotic features as described below for smaller caliber arteries, occasional areas of necrosis, mineralization, or chondroid metaplasia. Smooth muscle cells of the tunica media in all medium to large caliber arteries were distended with clear vacuolar cytoplasm (glycosaminoglycan, GAG). Asymmetric areas of intimal thickening were occasionally found in extramural coronary and mesenteric arteries. In contrast, areas of intimal sclerosis were consistently and reproducibly found in transverse histologic sections from the distal aorta (viz. iliac branches) so we focused on this anatomic location for our studies. These lesions consisted of discrete to circumferential areas of asymmetric intimal thickening resulting in an approximate reduction of up to 60–70% of the lumen (Figures 1, 2). The internal elastic lamina in these areas was discontinuous with displacement of the free ends (Figure 3). The normal circumferential organization of the media was asymmetrically distorted in association with intimal lesions by interstitial accumulations of faintly basophilic extracellular matrix, elastin and loss of smooth muscle cells (Figures 1, 2) with infrequent cartilaginous metaplasia. This disorganization of the media was particularly apparent in sections stained for elastin and collagen. Many of the lining endothelial cells contained foamy cytoplasm (GAG), but this was not restricted to areas of sclerosis (not shown).

Figure 1.

Transverse histologic section from an untreated dog with MPS-I through distal aorta (central) just beyond branch points of external iliac arteries (left and right). Asymmetric areas of intimal sclerosis containing GAG (blue-green) infringe on vessel lumens and the normal smooth muscle (red) of the vessel is disrupted. Vena cava is below the arteries (Movat’s modified pentachrome).

Figure 2.

Intimal plaque replacing >50% of an arterial lumen from an untreated MPS-I dog contains smooth muscle and/or myofibroblasts (brown stain) with some loss of normal muscle structure in the media (asterisk; α-smooth muscle actin IHC).

Figure 3.

Plaque in an untreated MPS-I dog showing disruption of internal elastic lamina (black). Plaque matrix with GAG (blue-green) separating smooth muscle cells (red), containing cytoplasmic storage material (vacuolation). Smaller foamy macrophages, also with cytoplasmic GAG storage, are scattered throughout and clustered in this image (arrow) around a free end of the internal elastic lamina (Movat’s modified pentachrome).

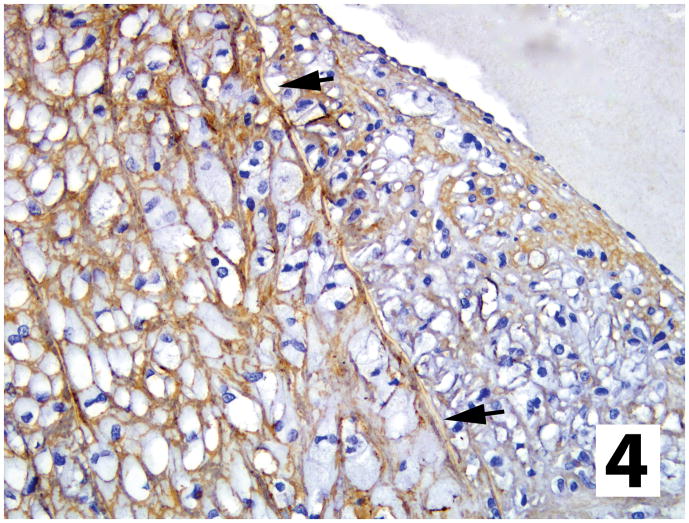

The thickened tunica intima (plaque) consisted of abundant extracellular matrix and cells distended with finely vacuolated (foamy) cytoplasm, which was blue-green in Movat’s stained sections (some lysosomal content lost in histologic processing). Larger plaques contained small arterioles and capillaries (neovascularization). Expression of activated caspase-3 (as a marker of apoptosis) was very rare in areas of intimal sclerosis and was not found within the endothelium (not shown). A very thin rim of type IV collagen outlined smooth muscle cells of the media in affected and unaffected dogs (Figure 4). Laminin and type IV collagen were present below the endothelium lining vessels from unaffected dogs but these components of basal lamina were discontinuous or absent in affected vessels, particularly in association with intimal plaques (Figure 4). Similarly, claudin-5 was diffusely expressed in the endothelial lining of unaffected dog arteries and throughout most of the endothelium lining vessels from affected dogs, except in areas of plaque formation where it was absent or highly discontinuous (Figure 5). Most of the intimal mesenchymal cell types were identified as either fibroblasts or myofibroblasts/smooth muscle, based on elongate, spindled morphology, histochemical staining characteristics and expression of α-smooth muscle actin (Figure 2, 3). Myofibroblasts traversed regions where the internal elastic lamina had ruptured and were oriented perpendicular to the internal elastic lamina; when concentrated towards the luminal aspect of the plaque they were oriented parallel to the overlying endothelium. There was otherwise no pattern or organization of these cells or matrix within the plaques from untreated dogs. There were scattered cells expressing proliferating cell nuclear antigen morphologically consistent with macrophages and either myofibroblasts or fibroblasts within the intimal plaques (not shown), suggesting that in situ proliferation at least partially contributes to intimal cellularity. Although infrequent in the media of dogs with MPS-I, smooth muscle cells expressing proliferating cell nuclear antigen were much less common in the media of unaffected dogs (not shown). Macrophages were the other common cell type within areas of sclerosis, based on cell morphology and cytoplasmic or cell membrane staining for lysozyme and/or CD18 (Figure 6), respectively. Macrophages were scattered throughout the intimal plaques and were often clustered immediately below the endothelium (Figure 6) or in areas of neovascularization, most of them distended with foamy cytoplasm (GAG) in untreated dogs. Subendothelial foamy macrophages were not found in adjacent unaffected vasculature (Figure 6).

Figure 4.

Arterial wall (to left) and intimal plaque (arrows = internal elastic lamina) from an untreated MPS-I affected dog stained for type IV collagen, which encircles smooth muscle of media but is absent under the endothelium lining the plaque (type IV collagen IHC stain).

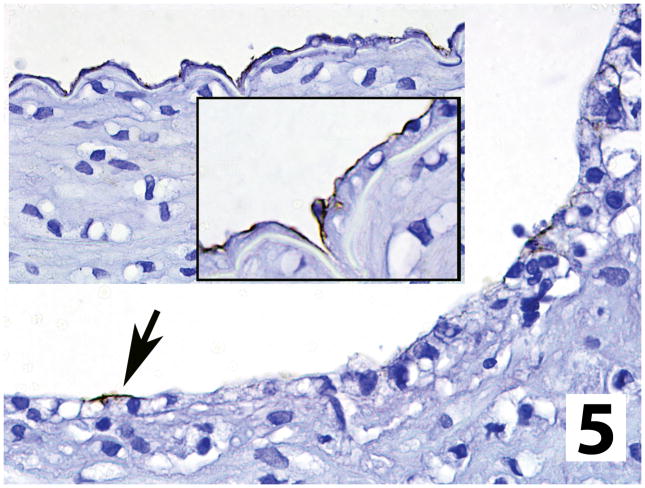

Figure 5.

Endothelial claudin-5 expression in an untreated MPS-I affected dog is almost completely lost over intimal plaques (arrow), in comparison to adjacent arterial wall, were no plaque is present (insets; claudin-5 IHC stain).

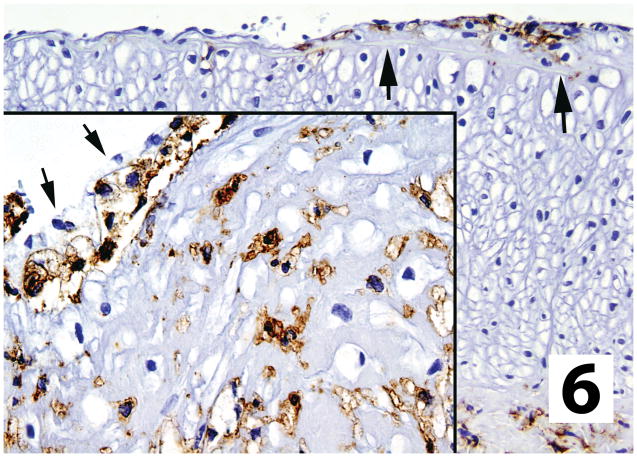

Figure 6.

Macrophages in small/early sclerotic plaque (arrows) and larger plaque (inset) in vessels from untreated dogs. Macrophages were not present in arterial walls outside plaques and were often clustered immediately below the endothelium (inset arrows) of the affected vessel (CD18 IHC stain).

Extracellular matrix (ECM) in plaques consisted of a very loose to more densely packed eosinophilic fibrillar collagen separated by faintly basophilic amorphous ground substance. The ratio of cells to matrix varied considerably within plaques, particularly larger ones, with more ECM typically present towards the middle of these lesions (i.e. Figure 2). Modified Movat’s pentachrome and Masson trichrome histochemical staining confirmed that the fibrillar material was collagen (not shown). The amorphous material was often brightly green-blue in Movat’s stained sections (Figures 1, 3) and also stained with Alcian blue (not shown), indicating the presence of glycosaminoglycans. Cytoplasmic granular staining for GAG was present in swollen foamy macrophages (Figure 3) and other cells containing the vacuolar storage material. Thick to thin short branching elastin fibrils were variably present within plaques, sometimes in focally dense tangles. There was consistent fragmentation and occasional loss of the internal elastic lamina in areas of intimal sclerosis (Figures 1, 3) as well as multifocal fragmentation of the external elastic laminae (not shown). Glycosaminoglycan-containing ground substance and collagen in some vessels extended from the expanded intima into or through the subjacent tunica media, separating and replacing the smooth muscle fibers (Figures 1, 2).

There was little to no immunostaining for TGF-β1 in vessels from unaffected dogs, but in affected MPS-I vessels the neointima was distinctly positive, particularly towards the lumen (not shown). This included the matrix and, in some instances, the cytoplasm of subendothelial foamy macrophages. Intracellular staining for TGF-β1 was most intense in the moderately distended cells compared to the markedly distended cells, where the staining was sparse. At the same time, nuclear expression of Smad3 was prominent in cells within the plaque (Figure 7).

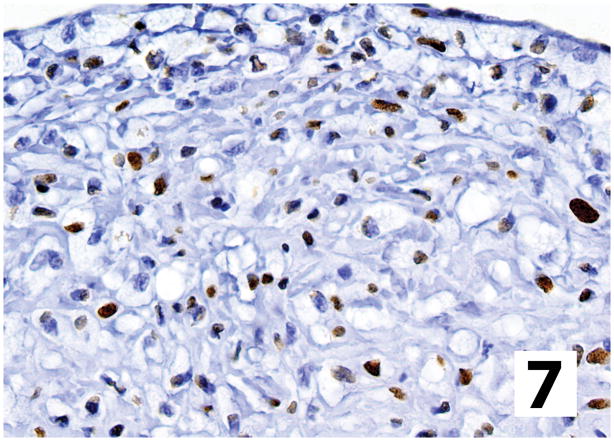

Figure 7.

Intimal plaque (endothelium at top) from an untreated dog with MPS-I has nuclear Smad3 localization (brown) in scattered cells morphologically consistent with fibroblasts/myofibroblasts and macrophages, indicating TGF-β signaling (Smad3 IHC stain).

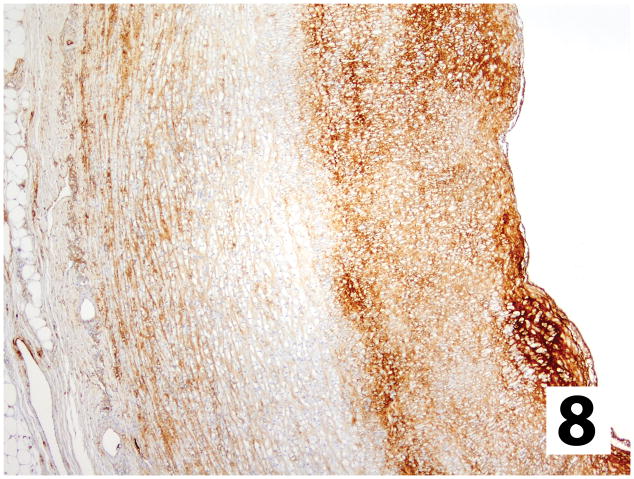

In unaffected normal dogs, fibronectin was present in arterial subendothelial basement membranes, around medial smooth muscle cells, and throughout the adventitia. In vessels from dogs with MPS-I the most intensely stained areas corresponded to the most intensely labeled areas of TGF-β1 immunoreactivity, with the strongest expression in the subendothelial areas of intimal plaques (Figure 8). Fibronectin was predominantly found in the ECM but was also present in some cells. The tunica media of affected vessels had more staining for both TGF-β1 and fibronectin as compared to unaffected vessels, located primarily in areas of medial damage/remodeling near intimal plaques (not shown).

Figure 8.

Fibronectin expression in an intimal plaque from an untreated dog with MPS-I contains more abundant fibronectin staining than the adjacent media, with rapid decreases at the internal elastic lamina. The densest accumulations were subjacent to the endothelium (to right of image). (Fibronectin IHC stain).

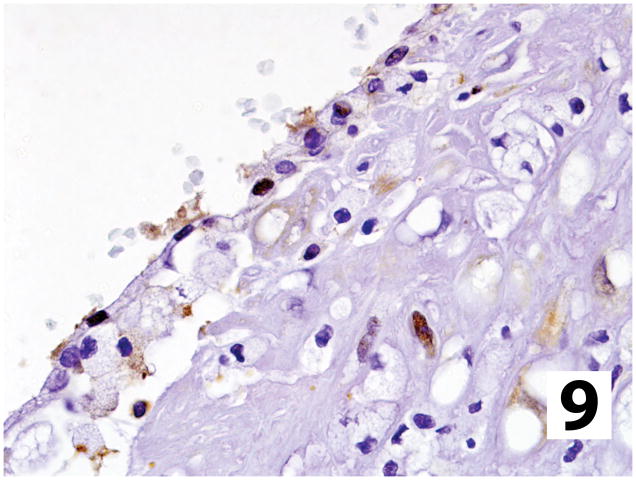

Rarely, endothelial and smooth muscle cells were immunoreactive for NF-κβ (p65) in control vessels from unaffected dogs. In contrast, nuclear expression increased considerably in the neointima of affected vessels and included some macrophages. Positive cells were scattered throughout the intima (Figure 9) but there were focal ‘hotspots’ with 10–15 clustered cells expressing nuclear p65.

Figure 9.

Intranuclear localization of p65 indicating activation of NF-κB signaling in scattered cells within the intimal plaque of an untreated dog with MPS-I (p65 IHC stain).

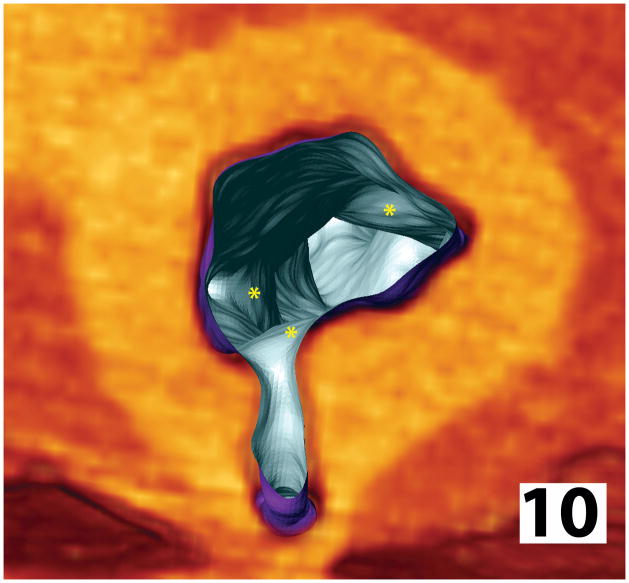

X-Ray Computed Tomography

In order to determine the distribution of vascular lesions along the distal aorta and its branches, we examined fixed tissues from several affected dogs by CT and reconstructed scans for 3 dimensional analyses (Supplemental information, movie). Neointimal plaques were found in association with arterial branches. Specifically, these were most often present in the aortic wall just distal (downstream) and ipsilateral to the arterial branch point(s), associated with asymmetric thickening of the aortic wall (corresponding to histologic lesions described above) and reduced luminal diameter (Figure 10). Frequently, there was also narrowing of the branch lumen as it exited the aorta. In areas where larger branches created a triad of similarly sized subsidiaries (i.e. external iliacs) the sclerotic lesions were more complex involving opposing lateral walls (Figure 1).

Figure 10.

Reconstruction of sublumbar aortic microCT scan from a non-tolerant dog with MPS-I that had received low doses of IdU. Areas of intimal plaque formation (asterisks) are localized just beyond arterial branch points and taper distally along the aortic wall, with some thickening at the os of these branches and luminal narrowing. In contrast, vessels from normal animals are cylindrical structures with smooth interior surfaces, constant luminal diameters and have a uniform circumferential wall thickness.

Effects of Recombinant Enzyme Treatment

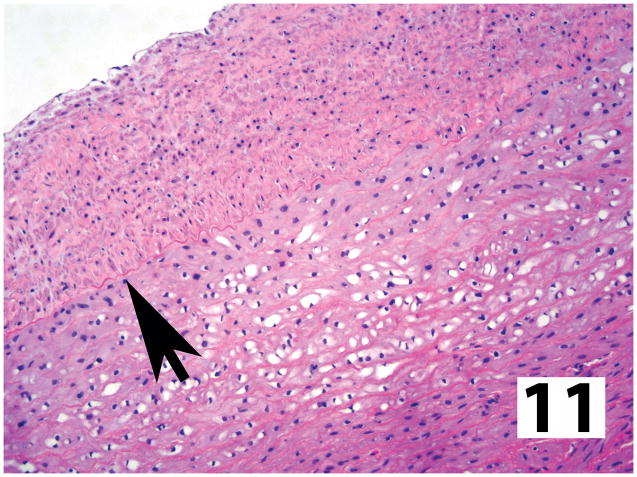

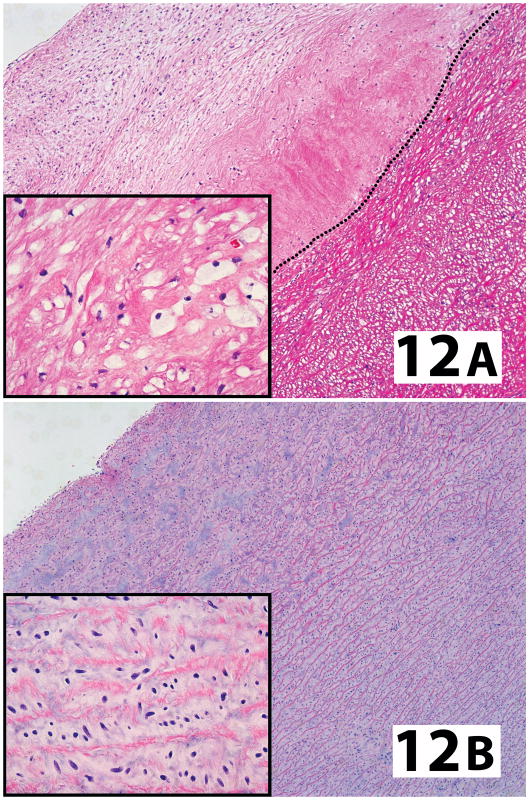

The pattern of changes in vessels from treated dogs generally followed the responses found in other tissues, as previously published.21–26 Adult dogs treated with IV IdU at lower doses (0.6 mg/kg) and not preconditioned to induce immunologic tolerance had almost no evidence of beneficial effects, other than a reduction in endothelial GAG storage and fewer subendothelial foamy macrophages. The intimal plaques and medial smooth tunics could not otherwise be distinguished from untreated animals. Treatment of adult dogs with the higher dose (2 mg/kg IV IdU) further reduced subendothelial GAG vacuolation in the plaques, creating a thin subendothelial rim of sclerotic tissue with less storage material in some areas, but the rest of the plaques and the media were otherwise unaffected by therapy. When animals were made tolerant to IdU through use of immunosuppressive compounds24 there was a distinct improvement from IV enzyme treatment with both low dose, and in particular, high dose regimens (Figure 11). Vessels from these dogs had less storage material within both plaques and the medial smooth muscle in areas without plaque formation. The intimal plaques were more organized with laminar organization of fibrous tissue, parallel to the endothelium, more compact collagen and structurally intact elastic laminae, less ECM and GAG (by Movat’s stain) and reduced numbers of arterioles and capillaries (neovascularization) and macrophages. Direct comparison of the size/thickness of these plaques was not feasible, but they generally appeared smaller/thinner than in treated, non-tolerant or untreated dogs. Storage material in the medial smooth muscle in tolerant, high dose treated animals was still present in scattered foci (Figure 11), but often completely absent across the entire vessel wall. Finally, when either high (Figure 12-A) or low dose treatment was initiated soon after birth, all evidence of storage material was eliminated from the entire arterial wall in the proximal/supravalvular aorta and mural architecture, including the intima, was essentially the same as in normal, unaffected dogs. In contrast, proximal aorta from untreated littermates and any of the other treatment regimens started at an older age (generally > 12 months) retained storage material and degrees of sclerosis (Figure 12-B). The distal aorta was not sampled in animals treated from birth, but complete inhibition of lesion development in this location (and throughout the body) can reasonably be predicted from responses observed in the proximal aorta.

Figure 11.

Affected large caliber artery from MPS-I affected dog made tolerant to IdU and treated weekly with high doses of recombinant enzyme. The intimal plaque is more organized with complete absence of storage material (arrow = internal elastic lamina). Intracellular GAG vacuolization has been almost completely eliminated in the adjacent media (hematoxylin and eosin stain).

Figure 12.

In comparison to animals receiving any form of treatment at an older age (A; high dose IdU without tolerance. Dotted line = internal elastic lamina), the proximal (supravalvular) aorta from dogs treated from birth (B; high dose IdU) completely lacked any evidence of intracellular storage material in the media (inserts) or intimal plaque formation (hematoxylin and eosin stain).

Discussion

Vascular disease can be widespread in patients with MPS-I and, while typically not fatal, may contribute to clinical disease. Autopsies of MPS-I patients have shown the arterial narrowing to be caused by development of “Hurler plaque” within the intima and inner portion of the media of the large and medium-sized arteries, particularly within the heart.15–17 The canine model of MPS-I in our studies shares many of the same clinical and pathologic features as humans, including this vasculopathy. However, in contrast to the more extensive and diffuse sclerosis seen in coronary vessels of Hurler patients, coronary lesions in the dogs were more sparsely scattered and presumably associated with branch points (as in the distal aorta). The literature contains much less information about vascular lesions outside the heart in Hurler patients. Interestingly, mice with MPS-I develop relatively mild lesions in their proximal aorta but none of the arteriosclerotic coronary or peripheral arterial lesions found in affected dogs and people31 (M.F. McEntee, unpublished observations). While most descriptions of cardiovascular disease in children focus on the cardiac valvular and coronary arterial changes, occlusive disease of the abdominal aorta and renal arteries can be extensive in these individuals and associated with systemic hypertension.16 We have found that the distal aorta and its proximal branches are also affected in dogs with MPS-I, although it remains to be determined whether these animals develop clinical hypertension. The purpose of this study was to further characterize the vasculopathy in dogs with MPS-I and examine the relative effects of various treatments with recombinant IdU.

There are distinct morphologic similarities between intimal plaques in atherosclerosis and MPS-I and it therefore seems logical that they also share pathogenic mechanisms, despite the distinct underlying metabolic disturbances. It has been shown that atherosclerotic lesions develop primarily in locations with low endothelial shear stress, increased turbulence and oscillating blood flow, associated with branches in the vascular tree.32–34 In contrast, regions with laminar flow and the opposite hemodynamic forces are relatively resistant to plaque formation. We have shown that the distal aortic lesions in dogs with MPS-I are localized primarily in areas subjected to the same hemodynamic factors that lead to atherosclerotic plaques, implicating this predisposing mechanism in MPS-I vasculopathy. What is not clear, however, is how GAG accumulation sensitizes these vascular tissues to plaque formation, as lipid imbalances and oxidative stress do in atherosclerosis. We chose to further characterize the nature of these lesions by looking for expression of proteins previously associated with atherosclerosis and/or restenosis in order to help shed some light on lesion morphogenesis and possible signaling pathways involved in MPS-I vascular disease.

Intimal plaques in dogs with MPS-I consist of a greatly expanded interstitial matrix containing GAG (“ground substance”), collagen and elastin. The cellular component consists primarily of fibroblasts and myofibroblasts (or smooth muscle cells), responsible for much of the matrix deposition. These cells, which were often themselves distended with GAG storage material, could have either migrated into the intima through fracture sites in the underlying internal elastic lamina, as dedifferentiated smooth muscle, or perhaps through the overlying endothelial layer from circulating mesenchymal stem cells,35 with subsequent local replication. In either case the asymmetric and localized distribution of the plaques within the vasculature implicates endothelium and/or internal elastic lamina as primary targets of hemodynamic forces in early Hurler plaque formation. Endothelial cells subjected to the hemodynamic forces typically found around branch points have a markedly altered gene expression profile and phenotype.34, 36 We have shown that endothelial basal lamina components and the adhesion protein claudin-5 are down regulated in areas of plaque formation, presumably when endothelium in these areas is subjected to reduced shear stress and other atherogenic hemodynamic forces. These effects in areas of plaque formation would increase endothelial permeability and egress of circulating cells. In fact, macrophages, many laden with GAG, were common immediately below the endothelium in areas of neointimal plaque formation. These macrophages might then contribute to lysis of the internal elastic lamina with release of various degradative enzymes (e.g. membrane metalloproteinases) and lesion progression. Although plausible, the phenotype and biologic activity of macrophages in this disease has not been adequately examined. We have shown, however, that at least some of the intralesional macrophages in the canine Hurler plaques exhibit activated NF-κβ signaling and/or upregulation of TGF-β1 expression. These changes no doubt contribute to a phlogistic tone as well as expansion and remodeling of connective tissues with plaque growth, as occurs in atherosclerosis. Surprisingly, we very rarely encountered cyclooxygenase-2 expression in the canine vascular lesions (not shown), distinguishing them from atherosclerosis. Although endothelial cell apoptosis was not found in sections stained for activated caspase-3, this certainly does not rule out the potential for low rates of cell death particularly as these would rapidly detach into the blood. It was clear that endothelial cells in this area of the vasculature were laden with GAG in MPS-I affected dogs, and damage or loss of endothelium through apoptosis, in addition to altered responses to normal hemodynamic forces, could contribute to plaque initiation and propagation.

TGF-β1 and fibronectin are integral in many physiologic and pathophysiologic processes and their expression was distinctly increased in the matrix of canine intimal plaques and, in particular, just below the endothelium. TGF-β1 is a multifunctional cytokine that exerts its affects in a both autocrine and paracrine manner to regulate cell proliferation, differentiation, wound repair and tissue remodeling. It promotes net matrix deposition by increasing the expression of specific ECM components such as fibronectin, collagen, dermatan and heparan sulfate proteoglycans, and inhibitors of the ECM proteases, such as tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinases. TGF-β1 simultaneously down-regulates proteases which degrade matrix components, and the net effect is connective tissue expansion.37–39 Fibronectin, in turn, can cause smooth muscle activation and migration, and is chemotactic for macrophages.40 The TGF-β-fibronectin system plays a vital role in the characteristic changes of the vascular smooth muscle cells during transition from a structural to a synthetic phenotype, as occurs with atherosclerotic plaque formation; by analogy it seems likely this stimulus is also involved in the appearance of α-smooth muscle actin positive myofibroblasts and matrix deposition in Hurler plaques. TGF-β1 directly or indirectly induces fibronectin production, which may involve activation of NF-κB through the JNK pathway.41 NF-κβ transcriptional activation was demonstrated in the MPS-I plaques with intranuclear migration of p65 (REL-A) and is central in all toll-like receptor signaling pathways. Interestingly, toll-like receptor-4 has recently been shown to play a role in MPS disease expression.11, 12

The fact that MPS-I sensitizes dogs to intimal arterial disruption and sclerosis associated with hemodynamic stressors that are also associated with atherosclerotic plaque formation is intriguing, but much more work will be required to determine the underlying mechanisms and the pathogenic relationship between intracellular storage material and the morphologic changes noted above. The lysosome is now recognized as important in diverse cellular functions, in addition to degradation and recycling of intra- and extracellular materials.14 Accumulation of dermatan and heparan sulfate GAG within this compartment in endothelium, fibroblasts, macrophages and myofibroblasts of MPS-I patients must be responsible for the subsequent tissue changes either through cytotoxic effects and/or altered cell function/signaling, dependent on the degree of storage and microenvironmental cell/tissue context. Our results strongly suggest that this manifests as a localized phenomenon in the vasculature of MPS-I dogs in response to normal hemodynamic forces that are also responsible for atherogenesis. Reduction of this storage material in the vasculature with recombinant enzyme therapy clearly mitigates the vasculopathy, particularly in the context of immune tolerance achieved either through administration of the enzyme at an early age or use of immunosuppressive drugs. We attribute the role of immune tolerance in ERT efficacy to be enhanced delivery of the enzyme, and not a result of drug-induced immunosuppression, because: 1) specific antibodies against the enzyme inhibit uptake in vitro; 2) the immune suppressive drugs were administered for a limited time (60 days); and 3) animals treated with an abbreviated regimen (21–45 days) of immunosuppressive drugs that failed to induce tolerance exhibited similar tissue ERT efficacy as that observed in non-tolerant dogs that had not received these drugs.24 Thus, administration of immunosuppressive drugs without induction of tolerance does not improve efficacy of ERT. We have shown in these studies that early initiation of ERT may prevent arterial vasculopathy associated with MPS-I, and have reported elsewhere that the same is true for other refractory tissues such as the atrioventricular valve.27 Whether longer term therapy initiated in older animals would eventually result in complete remodeling and regression of these plaques, as suggested for atherosclerosis,42 remains to be determined. Further investigation of the pathogenic role abnormal GAG accumulation plays in altering the normal cell-cell, cell-matrix interactions in MPS-I (and other storage diseases) is warranted in order to develop adjunct therapies that complement use of recombinant IdU.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Alan Stuckey for acquiring the vascular microCAT scans and rendering them for visualization, and the innumerable staff members at Harbor UCLA and Iowa State who have contributed benchtop and clinical efforts without which we could not have obtained the samples used in this study. Additional affected and breeding animals were provided by Drs. Mark E. Haskins (NIH RR002512, University of Pennsylvania) and Katherine P. Ponder (NIH DK066448, Washington University, St. Louis)

Funding provided by grants from the National Institutes of Health (NS054242 to PID), the Ryan Foundation (NME), the Center for Integrated Animal Genomics/ISU (NME), and the State of Iowa Board of Regents Battelle Platform and Infrastructure Grant Programs (NME).

ABBREVIATIONS

- IdU

α-L-iduronidase

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- GAG

glycosaminoglycan

- IHC

immunohistochemistry

- MPS-I

mucopolysaccharidosis-I

- NF-κB

nuclear factor-κβ

- TGF-β1

transforming growth factor beta-1

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Supplementary information is available at Laboratory Investigation’s website

References

- 1.Dorfman A, Matalon R. The mucopolysaccharidoses (a review) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1976;73:630–637. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.2.630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Neufeld EF, Muenzer J. The Mucopolysaccharidoses. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Sly WS, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Diseases. McGraw-Hill Professional; 2001. pp. 3421–3452. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kakkis ED, Muenzer J, Tiller GE, et al. Enzyme-replacement therapy in mucopolysaccharidosis I. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:182–188. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200101183440304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Muenzer J, Wraith JE, Clarke LA. Mucopolysaccharidosis I: management and treatment guidelines. Pediatrics. 2009;123:19–29. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Spellacy E, Shull RM, Constantopoulos G, et al. A canine model of human α-L-iduronidase deficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6091–6095. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.19.6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shull RM, Helman RG, Spellacy E, et al. Morphologic and biochemical studies of canine mucopolysaccharidosis I. Am J Pathol. 1984;114:487–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shull RM, Munger RJ, Spellacy E, et al. Canine α-L-iduronidase deficiency. A model of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Am J Pathol. 1982;109:244–248. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Menon KP, Tieu PT, Neufeld EF. Architecture of the canine IDUA gene and mutation underlying canine mucopolysaccharidosis I. Genomics. 1992;14:763–768. doi: 10.1016/s0888-7543(05)80182-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ohmi K, Greenberg DS, Rajavel KS, et al. Activated microglia in cortex of mouse models of mucopolysaccharidoses I and IIIB. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:1902–1907. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252784899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinek A, Braun KR, Liu K, et al. Retrovirally mediated overexpression of versican v3 reverses impaired elastogenesis and heightened proliferation exhibited by fibroblasts from Costello syndrome and Hurler disease patients. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:119–131. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63103-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Metcalf JA, Linders B, Wu S, et al. Upregulation of elastase activity in aorta in mucopolysaccharidosis I and VII dogs may be due to increased cytokine expression. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;99:396–407. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Simonaro CM, Ge Y, Eliyahu E, et al. Involvement of the Toll-like receptor 4 pathway and use of TNF-alpha antagonists for treatment of the mucopolysaccharidoses. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:222–227. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912937107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ma X, Tittiger M, Knutsen RH, et al. Upregulation of elastase proteins results in aortic dilatation in mucopolysaccharidosis I mice. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;94:298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ballabio A, Gieselmann V. Lysosomal disorders: from storage to cellular damage. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2009;1793:684–696. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brosius FC, III, Roberts WC. Coronary artery disease in the Hurler syndrome. Qualitative and quantitative analysis of the extent of coronary narrowing at necropsy in six children. Am J Cardiol. 1981;47:649–653. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(81)90550-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Taylor DB, Blaser SI, Burrows PE, et al. Arteriopathy and coarctation of the abdominal aorta in children with mucopolysaccharidosis: imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:819–823. doi: 10.2214/ajr.157.4.1909834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krovetz LJ, Lorincz AE, Schiebler GL. Cardiovascular manifestations of the Hurler syndrome: Hemodynamic and Angiocardiographic observations in 15 patients. Circulation. 1965;31:132–141. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.31.1.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braunlin EA, Berry JM, Whitley CB. Cardiac findings after enzyme replacement therapy for mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:416–418. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.02.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braunlin E, Mackey-Bojack S, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, et al. Cardiac functional and histopathologic findings in humans and mice with mucopolysaccharidosis type I: implications for assessment of therapeutic interventions in Hurler syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2006;59:27–32. doi: 10.1203/01.pdr.0000190579.24054.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Renteria VG, Ferrans VJ, Roberts WC. The heart in the Hurler syndrome: gross, histologic and ultrastructural observations in five necropsy cases. Am J Cardiol. 1976;38:487–501. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(76)90468-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kakkis ED, McEntee MF, Schmidtchen A, et al. Long-term and high-dose trials of enzyme replacement therapy in the canine model of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Biochem Mol Med. 1996;58:156–167. doi: 10.1006/bmme.1996.0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shull RM, Kakkis ED, McEntee MF, et al. Enzyme replacement in a canine model of Hurler syndrome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:12937–12941. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.26.12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Passage MB, Krieger AW, Peinovich MC, et al. Continuous infusion of enzyme replacement therapy is inferior to weekly infusions in MPS I dogs. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2009. URL: www.springerlink.com/content/0250912230732ng1/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Dickson P, Peinovich M, McEntee M, et al. Immune tolerance improves the efficacy of enzyme replacement therapy in canine mucopolysaccharidosis I. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:2868–2876. doi: 10.1172/JCI34676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dickson P, McEntee M, Vogler C, et al. Intrathecal enzyme replacement therapy: successful treatment of brain disease via the cerebrospinal fluid. Mol Genet Metab. 2007;91:61–68. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2006.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dickson PI, Hanson S, McEntee MF, et al. Early versus late treatment of spinal cord compression with long-term intrathecal enzyme replacement therapy in canine mucopolysaccharidosis type I. Mol Genet Metab. 2010;10:115–122. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2010.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dierenfeld AD, McEntee MF, Vogler C, et al. Enzyme therapy from birth normalizes systemic disease and treats the brain in canine mucopolysaccharidosis I. Science Translational Medicine. 2010 under review. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hinek A, Wilson SE. Impaired elastogenesis in Hurler disease: dermatan sulfate accumulation linked to deficiency in elastin-binding protein and elastic fiber assembly. Am J Pathol. 2000;156:925–938. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64961-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Musto L. Modified Movat’s pentachrome stain. J Histotech. 1986;9:173–174. [Google Scholar]

- 30.McEntee MF, Chiu CH, Whelan J. Relationship of β-catenin and Bcl-2 expression to sulindac induced regression of intestinal tumors in Min mice. Carcinogenesis. 1999;20:635–640. doi: 10.1093/carcin/20.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jordan MC, Zheng Y, Ryazantsev S, et al. Cardiac manifestations in the mouse model of mucopolysaccharidosis I. Mol Genet Metab. 2005;86:233–243. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2005.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cunningham KS, Gotlieb AI. The role of shear stress in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Lab Invest. 2005;85:9–23. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.VanderLaan PA, Reardon CA, Getz GS. Site specificity of atherosclerosis: site-selective responses to atherosclerotic modulators. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2004;24:12–22. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000105054.43931.f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hastings NE, Simmers MB, McDonald OG, et al. Atherosclerosis-prone hemodynamics differentially regulates endothelial and smooth muscle cell phenotypes and promotes pro-inflammatory priming. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C1824–C1833. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00385.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Keeley EC, Mehrad B, Strieter RM. Fibrocytes: bringing new insights into mechanisms of inflammation and fibrosis. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2010;42:535–542. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Davies PF. Hemodynamic shear stress and the endothelium in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Nat Clin Pract Cardiovasc Med. 2009;6:16–26. doi: 10.1038/ncpcardio1397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Blobe GC, Schiemann WP, Lodish HF. Role of transforming growth factor β in human disease. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1350–1358. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rasmussen LM, Wolf YG, Ruoslahti E. Vascular smooth muscle cells from injured rat aortas display elevated matrix production associated with transforming growth factor-beta activity. Am J Pathol. 1995;147:1041–1048. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wells RG. Fibrogenesis V. TGF-β signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2000;279:G845–G850. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2000.279.5.G845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Norris DA, Clark RA, Swigart LM, et al. Fibronectin fragment(s) are chemotactic for human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol. 1982;129:1612–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hocevar BA, Brown TL, Howe PH. TGF-beta induces fibronectin synthesis through a c-Jun N-terminal kinase-dependent, Smad4-independent pathway. EMBO J. 1999;18:1345–1356. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.5.1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shanmugam N, Roman-Rego A, Ong P, et al. Atherosclerotic plaque regression: Fact or fiction? Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 2010;24:311–317. doi: 10.1007/s10557-010-6241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.