Abstract

Endoscopic ultrasonography is an established diagnostic tool for pancreatic masses and chronic pancreatitis. In recent years there has been a growing interest in the worldwide medical community in autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP), a form of chronic pancreatitis caused by an autoimmune process. This paper reviews the current available literature about the endoscopic ultrasonographic findings of AIP and the role of this imaging technique in the management of this protean disease.

Keywords: Pancreatitis, Autoimmune, Endoscopic ultrasound, IgG4 cholangitis

INTRODUCTION

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) is superior to standard imaging techniques in detecting pancreatic cancer or masses and in the assessment of early parenchymal changes in chronic pancreatitis[1,2]; however, its role in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) has yet to be standardized, even though its high accuracy together with its safety make it a promising tool in the management of this disease.

To date, no consensus about the diagnosis of AIP has been reached[3]. Several criteria have recently been proposed, reflecting the different clinical entities that AIP can adopt worldwide[4-9]. The diffuse form of AIP has typically been included in the first set of criteria[4], and in 2008 only, a focal pancreatic enlargement evident upon imaging was classified as a form of AIP.

Obstructive jaundice is the most common presentation of AIP and, together with biochemical and imaging features, can mimic neoplastic conditions[10,11]. Because AIP is a benign disease, a definitive diagnosis without the need for surgery is desirable.

AIP can present with extrapancreatic lesions, the most frequent being IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis (IgG4-SC), followed by hilar lymphadenopathy[12].

EUS can display both of these conditions in addition to parenchymal, ductal and vascular lesions. Moreover, this technique offers the advantage over other diagnostic tools of allowing clinicians to perform biopsies to achieve a definitive diagnosis[13-16].

In this article, we describe the EUS findings of AIP (Table 1) by reviewing the currently available literature in this field.

Table 1.

Endoscopic ultrasonography features of autoimmune pancreatitis

|

Pancreas |

Extrahepatic bile duct | Gallbladder | Lymph nodes1 | Peripancreatic vessels | ||

| Diffuse AIP | Focal AIP | |||||

| EUS | Gland volume: increased | Gland volume: focal enlargement/s | Caliber: dilated | Wall: diffuse and uniform thickening, “sandwich-pattern”1 | Volume: enlarged (also substantially) | Loss of interface between pancreas and portal or mesenteric veins1 |

| Echotexture: echopoor, with echogenic interlobular septa | Echotexture: echopoor, with echogenic interlobular septa | Wall: diffuse and uniform thickening, “sandwich-pattern”1 | Echotexture: echopoor | |||

| Gland border: thickened | Sites: liver hylum, peripancreatic, celiac | |||||

| Wirsung: narrowed | Wirsung: narrowed within the lesion, dilated upstream to the lesion | |||||

| Wirsung wall: thickened1 | Wirsung wall: thickened1 | |||||

| IDUS | Wall: diffuse and uniform thickening, “sandwich-pattern”; differential diagnosis with cholangiocarcinoma1 | |||||

Indicates the features which are detected only or substantially better by endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) and not seen in conventional cross-sectional imaging. AIP: Autoimmune pancreatitis; IDUS: Intraductal ultrasonography.

PANCREATIC FINDINGS

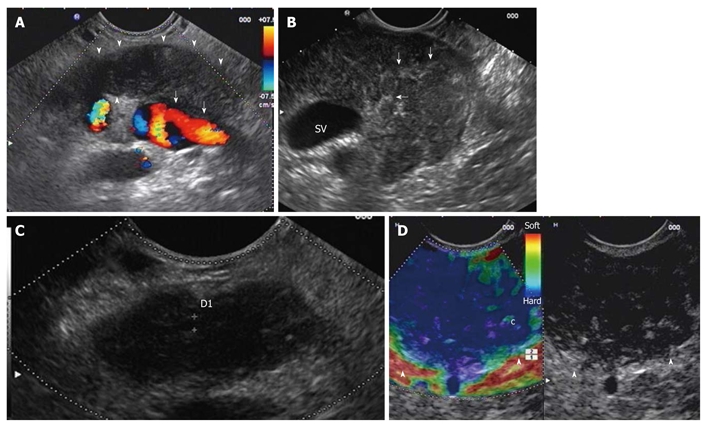

The predominant finding in the diffuse form of AIP is a diffuse pancreatic enlargement with altered echotexture (Figure 1)[14,15]. A recent retrospective study proposed to differentiate early from advanced stage AIP according to EUS findings[15]. In 19 patients with AIP, the presence of parenchymal lobularity and a hyperechoic pancreatic duct margin were significantly correlated with early stage AIP[17]. Other EUS findings that are indicative of AIP, such as reduced echogenicity, hyperechoic foci and hyperechoic strands (Figure 1), are found in both AIP stages[17]. Should these results be confirmed in prospective studies, EUS would acquire an essential role in the identification of early stage AIP, which is characterized by a prompt response to steroid therapy. Stones and cysts similar to those described in chronic alcoholic pancreatitis can occur in the late stage of AIP[18].

Figure 1.

Diffuse form of autoimmune pancreatitis. A: Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) linear scanning shows a diffuse pancreatic enlargement (arrowheads) with echopoor echotexture, and with loss of interface with splenic vein (arrows); B: Parenchymal lobularity and hyperechoic strands (arrows) are visible in the enlarged gland; C: Pancreatic duct calliper is 1.8 mm; D: EUS-elastography demonstrates the diffuse pancreatic stiffness (arrowheads).

The Sahai criteria for chronic pancreatitis were found to be inadequate to evaluate parenchymal and ductal changes in AIP[19]. According to the scoring system, a series of 25 patients with AIP were classified as normal or displaying mild disease[16].

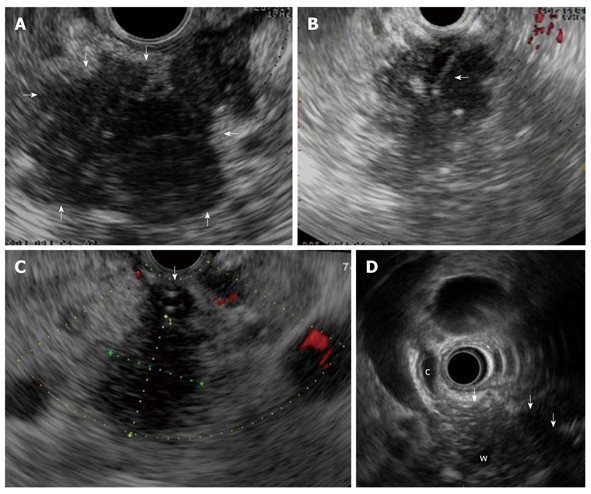

In the focal form of AIP a solitary (Figure 2), irregular hypoechoic mass, generally located in the head of the pancreas, is observed[13-15]. In addition, upstream dilatation of the main pancreatic duct could be observed[13,17]. In this setting, the overlap with EUS findings of pancreatic cancer is remarkable, and EUS-elastography (Figure 1) can provide further information about pancreatic lesions. In a case-control study of five patients with AIP, EUS-elastography showed a typical and homogeneous stiffness pattern of the focal lesions and of the surrounding parenchyma that is different from that observed in ductal adenocarcinoma[20].

Figure 2.

Focal form of autoimmune pancreatitis. A: Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) shows a focal lesion (arrows) of pancreatic head which is echopoor with hyperechoic strands; B: A EUS-guided fine needle aspiration is performed (arrow) for tissue characterization; C: Another case of focal autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) with echopoor lesion of pancreatic head (between callipers) and marked echopoor thickening of the choledochal wall (arrow); D: In this case of focal AIP EUS shows a echopoor lesion (arrows) of pancreatic head, with upstream dilatation of both common bile duct (c) and pancreatic duct (w); notice the thickened choledochal wall.

COMMON BILE DUCT FINDINGS

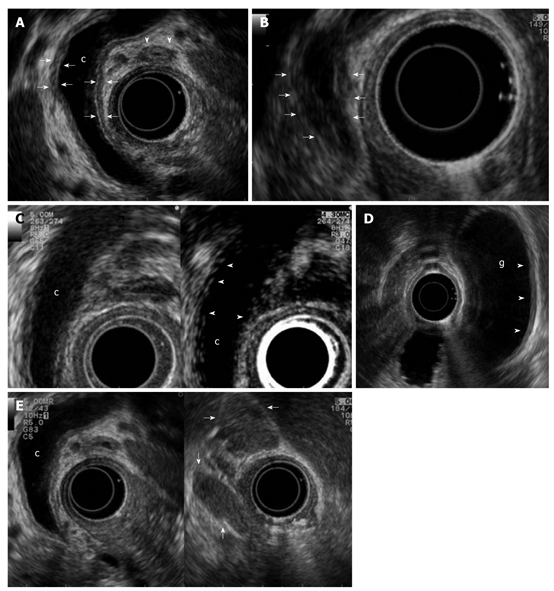

The common bile duct is the most frequent extrapancreatic organ involved in AIP and was found to affect 58% of patients in a Japanese survey[12]. Biliary strictures can mimic both sclerosing cholangitis and biliary cancer. EUS allows visualization of the entire common bile duct and enables identification of the cause of a biliary stricture. In patients with either diffuse or focal AIP, EUS can show dilatation of the common bile duct and thickening of its wall better than other diagnostic techniques[3,13-16,21]. The typical EUS feature of the common bile duct is a homogeneous, regular thickening of the bile duct wall, called “sandwich-pattern”, which is characterized by an echopoor intermediate layer and hyperechoic outer and inner layers, has been described as a EUS feature of the common bile duct; the cause of the biliary stricture is the thickened wall itself rather than extrinsic pancreatic compression (Figure 3)[3,13].

Figure 3.

Biliary and peripancreatic findings in autoimmune pancreatitis. Autoimmune pancreatitis presenting with jaundice: A: Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) shows a dilated common bile duct (c) upstream to a distal funnel-shaped stenosis; EUS demonstrates the diffuse thickening of the biliary wall (between arrows) with “sandwich-pattern”, either of common bile duct or of cystic duct (arrowheads). This thickening is equally visible both in the dilated region of the common bile duct; B: In the distal strictured tract (arrows); C: After contrast administration (Sonovue, Bracco) the biliary wall shows an early and persistent enhancement (arrowheads); D: EUS shows the same thickening of the gallbladder (g) wall (arrowheads); E: Enlarged lymph nodes to the hepatic hylum (arrows).

A further application of EUS is intraductal ultrasonography (IDUS), which can be performed during endoscopic retrograde cholangiography for the characterization of biliary stenosis. Naitoh et al[22] recently evaluated IDUS findings in 23 patients with IgG4-SC. They found that a circular, symmetric wall thickness, smooth inner and outer margins and a homogeneous intermediate layer in the stricture were significantly more common in AIP than in cholangiocarcinoma. The wall thickness in IgG4-SC in regions of non-stricture on the cholangiogram was significantly greater than that in cholangiocarcinoma and therefore a bile duct wall thickness exceeding 0.8 mm in regions of non-stricture on the cholangiogram was highly suggestive of IgG4-SC. Contrast enhancement of conventional EUS and IDUS showed an inflammatory pattern of the bile duct wall, with a long-lasting enhancement starting in the early phase instead of the poor enhancement found in bile duct cancer (Figure 3)[21].

PERIPANCREATIC FINDINGS

Hilar lymphadenopathy is one of the most frequently described extrapancreatic lesions[12]. Other sites of enlarged lymph nodes are the peripancreatic and celiac regions. EUS nodal features that accurately predict nodal metastasis have been previously identified in patients with esophageal cancer[23]; they include size (> 1 cm in diameter on the short axis), hypoechoic appearance, round shape, and smooth border. However, these conventional EUS criteria have proven inaccurate for staging non-esophageal cancers, including those that are biliopancreatic[24,25]. EUS can detect single or multiple enlarged lymph nodes in patients with AIP (Figure 3), reflecting the underlying inflammatory process, which can involve extra-pancreatic organs[14,15].

Hoki et al[16] reported a significant difference in detection of lymphadenopathy by EUS imaging over CT (72% vs 8%) in patients with AIP. Moreover, in the same series, a trend toward a higher prevalence of lymphadenopathy in AIP compared to pancreatic cancer was reported.

In the absence of specific nodal features indicating malignancy, the differential diagnosis with biliopancreatic neoplasms is arduous but can be achieved by evaluating the broad spectrum of clinical and imaging data of AIP patients.

EUS criteria for vascular invasion of pancreatic cancer have been established[26,27].

In a series of 14 patients with AIP, EUS suspected invasion of the portal or mesenteric veins in 21% of patients compared to 14% on CT. No pancreatic cancer developed during the follow-up of these patients. Such EUS features, easily mistaken for malignancy, are due to the inflammatory process of AIP, which can involve medium and large-sized vessels (Figure 1)[15].

Peripancreatic fluid collections are less common and not specific for AIP.

INTERVENTIONAL EUS IN AIP

In recent years, the possibility of guiding tissue sampling with either fine needle aspiration (EUS-FNA) (Figure 2) or Tru-cut biopsy (EUS-TCB) has increased the diagnostic potential of EUS by the acquisition of cytological and histological specimens from gastrointestinal lesions[28-30].

In the setting of AIP, EUS-FNA can be employed to yield specimens of pancreatic lesions, the common bile duct wall or lymph nodes[13,15]. Although a cytologic pattern specific for AIP has not been identified, high cellularity of stromal fragments with lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate has emerged as a discriminating feature in a retrospective series of 16 patients with an AIP diagnosis confirmed by histology of the respective specimens. Indeed, 56% of AIP patients presented such a feature vs 19% of patients with pancreatic carcinoma, and none of the chronic pancreatitis controls exhibited this feature[31]. Immunohistochemical staining can show IgG4-positive plasma cells which are a useful marker for the tissue diagnosis of AIP.

EUS-FNA can fail in diagnosis because of the small size of the specimens that do not have preserved tissue architecture. Moreover, sampling error due to the patchy distribution of AIP can occur. EUS-TCB can overcome these limitations by acquiring large samples fit for histological examination[30-32].

A recent study compared EUS-FNA and EUS-TCB performed in 14 patients for the diagnosis of AIP. EUS-TCB showed higher sensitivity (100%) and specificity (100%) compared to EUS-FNA (36% and 33%, respectively). Both procedures were found to be safe, with no complications[33].

However, the diagnostic accuracy of EUS-FNA for pancreatic cancer has been reported to range between 60% and 90%[34-36], and the shortcomings of EUS-TCB due to technical difficulties of the sampling of lesions in the pancreatic head should also be considered.

Hence, when AIP is suspected, a sequential sampling strategy has been proposed based on using EUS-FNA first, which is followed by EUS-TCB when cytologic examination is inconclusive[33].

In cases of inconclusive cytology, an additional aid for AIP diagnosis could come from molecular analysis of EUS-FNA samples, which has shown high accuracy in the differential diagnosis between AIP and pancreatic cancer[37].

CONCLUSION

AIP represents 20%-25% of benign diagnoses undergoing resection for presumed malignancy[38,39]. Thus, a definitive diagnosis based on safe and reliable methods should be obtained. In this setting, EUS could play an important role in diagnosis, identifying typical features of AIP and distinguishing it from biliopancreatic neoplasms. The higher sensitivity over standard imaging for pancreatic, biliary and nodal lesions should make it a cornerstone in the process of diagnosing AIP. If validated in large prospective series, newly available techniques such as EUS-elastography and CE-EUS could add useful information about focal lesions without resorting to invasive procedures. Finally, EUS-FNA or EUS-TCB can provide pathological specimens, as required by some diagnostic criteria.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Dr. Jeremy FL Cobbold, PhD, Clinical Lecturer in Hepatology, Department of Hepatology and Gastroenterology, Liver Unit, Imperial College London, St Mary’s Hospital, 10th Floor, QEQM building, Praed Street, London, W2 1NY, United Kingdom

S- Editor Tian L L- Editor O’Neill M E- Editor Zheng XM

References

- 1.Chang DK, Nguyen NQ, Merrett ND, Dixson H, Leong RW, Biankin AV. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in pancreatic cancer. Expert Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;3:293–303. doi: 10.1586/egh.09.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kahl S, Glasbrenner B, Leodolter A, Pross M, Schulz HU, Malfertheiner P. EUS in the diagnosis of early chronic pancreatitis: a prospective follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;55:507–511. doi: 10.1067/mge.2002.122610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buscarini E, Frulloni L, De Lisi S, Falconi M, Testoni PA, Zambelli A. Autoimmune pancreatitis: a challenging diagnostic puzzle for clinicians. Dig Liver Dis. 2010;42:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Japan Pancreas Society. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis. J Jpn Pancreas Soc. 2002;17:585–587. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okazaki K, Kawa S, Kamisawa T, Naruse S, Tanaka S, Nishimori I, Ohara H, Ito T, Kiriyama S, Inui K, et al. Clinical diagnostic criteria of autoimmune pancreatitis: revised proposal. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:626–631. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim MH, Kwon S. Diagnostic criteria for autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2007;42 Suppl 18:42–49. doi: 10.1007/s00535-007-2050-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chari ST, Smyrk TC, Levy MJ, Topazian MD, Takahashi N, Zhang L, Clain JE, Pearson RK, Petersen BT, Vege SS, et al. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis: the Mayo Clinic experience. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:1010–1016; quiz 934. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otsuki M, Chung JB, Okazaki K, Kim MH, Kamisawa T, Kawa S, Park SW, Shimosegawa T, Lee K, Ito T, et al. Asian diagnostic criteria for autoimmune pancreatitis: consensus of the Japan-Korea Symposium on Autoimmune Pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:403–408. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frulloni L, Gabbrielli A, Pezzilli R, Zerbi A, Cavestro GM, Marotta F, Falconi M, Gaia E, Uomo G, Maringhini A, et al. Chronic pancreatitis: report from a multicenter Italian survey (PanCroInfAISP) on 893 patients. Dig Liver Dis. 2009;41:311–317. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2008.07.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim KP, Kim MH, Song MH, Lee SS, Seo DW, Lee SK. Autoimmune chronic pancreatitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:1605–1616. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.30336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kamisawa T, Egawa N, Nakajima H, Tsuruta K, Okamoto A, Kamata N. Clinical difficulties in the differentiation of autoimmune pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003;98:2694–2699. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.08775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kamisawa T, Okamoto A. Autoimmune pancreatitis: proposal of IgG4-related sclerosing disease. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:613–625. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1862-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.De Lisi S, Buscarini E, Arcidiacono PG, Petrone M, Menozzi F, Testoni PA, Zambelli A. Endoscopic ultrasonography findings in autoimmune pancreatitis: be aware of the ambiguous features and look for the pivotal ones. JOP. 2010;11:78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sahani DV, Kalva SP, Farrell J, Maher MM, Saini S, Mueller PR, Lauwers GY, Fernandez CD, Warshaw AL, Simeone JF. Autoimmune pancreatitis: imaging features. Radiology. 2004;233:345–352. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2332031436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farrell JJ, Garber J, Sahani D, Brugge WR. EUS findings in patients with autoimmune pancreatitis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2004;60:927–936. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02230-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoki N, Mizuno N, Sawaki A, Tajika M, Takayama R, Shimizu Y, Bhatia V, Yamao K. Diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using endoscopic ultrasonography. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:154–159. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kubota K, Kato S, Akiyama T, Fujita K, Yoneda M, Takahashi H, Ogawa M, Inamori M, Abe Y, Kirikoshi H, et al. A proposal for differentiation between early- and advanced-stage autoimmune pancreatitis by endoscopic ultrasonography. Dig Endosc. 2009;21:162–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2009.00879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takayama M, Hamano H, Ochi Y, Saegusa H, Komatsu K, Muraki T, Arakura N, Imai Y, Hasebe O, Kawa S. Recurrent attacks of autoimmune pancreatitis result in pancreatic stone formation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:932–937. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sahai AV, Zimmerman M, Aabakken L, Tarnasky PR, Cunningham JT, van Velse A, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ. Prospective assessment of the ability of endoscopic ultrasound to diagnose, exclude, or establish the severity of chronic pancreatitis found by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Gastrointest Endosc. 1998;48:18–25. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(98)70123-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dietrich CF, Hirche TO, Ott M, Ignee A. Real-time tissue elastography in the diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis. Endoscopy. 2009;41:718–720. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1214866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hyodo N, Hyodo T. Ultrasonographic evaluation in patients with autoimmune-related pancreatitis. J Gastroenterol. 2003;38:1155–1161. doi: 10.1007/s00535-003-1223-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Naitoh I, Nakazawa T, Ohara H, Ando T, Hayashi K, Tanaka H, Okumura F, Takahashi S, Joh T. Endoscopic transpapillary intraductal ultrasonography and biopsy in the diagnosis of IgG4-related sclerosing cholangitis. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:1147–1155. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0108-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Catalano MF, Sivak MV Jr, Rice T, Gragg LA, Van Dam J. Endosonographic features predictive of lymph node metastasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:442–446. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70206-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhutani MS, Hawes RH, Hoffman BJ. A comparison of the accuracy of echo features during endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) and EUS-guided fine-needle aspiration for diagnosis of malignant lymph node invasion. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:474–479. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70176-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gleeson FC, Rajan E, Levy MJ, Clain JE, Topazian MD, Harewood GC, Papachristou GI, Takahashi N, Rosen CB, Gores GJ. EUS-guided FNA of regional lymph nodes in patients with unresectable hilar cholangiocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:438–443. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rösch T, Dittler HJ, Strobel K, Meining A, Schusdziarra V, Lorenz R, Allescher HD, Kassem AM, Gerhardt P, Siewert JR, et al. Endoscopic ultrasound criteria for vascular invasion in the staging of cancer of the head of the pancreas: a blind reevaluation of videotapes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:469–477. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.106682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Snady H, Bruckner H, Siegel J, Cooperman A, Neff R, Kiefer L. Endoscopic ultrasonographic criteria of vascular invasion by potentially resectable pancreatic tumors. Gastrointest Endosc. 1994;40:326–333. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(94)70065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vilmann P, Jacobsen GK, Henriksen FW, Hancke S. Endoscopic ultrasonography with guided fine needle aspiration biopsy in pancreatic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 1992;38:172–173. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(92)70385-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Levy MJ, Reddy RP, Wiersema MJ, Smyrk TC, Clain JE, Harewood GC, Pearson RK, Rajan E, Topazian MD, Yusuf TE, et al. EUS-guided trucut biopsy in establishing autoimmune pancreatitis as the cause of obstructive jaundice. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;61:467–472. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(04)02802-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wiersema MJ, Levy MJ, Harewood GC, Vazquez-Sequeiros E, Jondal ML, Wiersema LM. Initial experience with EUS-guided trucut needle biopsies of perigastric organs. Gastrointest Endosc. 2002;56:275–278. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(02)70193-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deshpande V, Mino-Kenudson M, Brugge WR, Pitman MB, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Warshaw AL, Lauwers GY. Endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration biopsy of autoimmune pancreatitis: diagnostic criteria and pitfalls. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29:1464–1471. doi: 10.1097/01.pas.0000173656.49557.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zamboni G, Lüttges J, Capelli P, Frulloni L, Cavallini G, Pederzoli P, Leins A, Longnecker D, Klöppel G. Histopathological features of diagnostic and clinical relevance in autoimmune pancreatitis: a study on 53 resection specimens and 9 biopsy specimens. Virchows Arch. 2004;445:552–563. doi: 10.1007/s00428-004-1140-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuno N, Bhatia V, Hosoda W, Sawaki A, Hoki N, Hara K, Takagi T, Ko SB, Yatabe Y, Goto H, et al. Histological diagnosis of autoimmune pancreatitis using EUS-guided trucut biopsy: a comparison study with EUS-FNA. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:742–750. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suits J, Frazee R, Erickson RA. Endoscopic ultrasound and fine needle aspiration for the evaluation of pancreatic masses. Arch Surg. 1999;134:639–642; discussion 642-643. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.134.6.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang KJ, Nguyen P, Erickson RA, Durbin TE, Katz KD. The clinical utility of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis and staging of pancreatic carcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 1997;45:387–393. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5107(97)70149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiersema MJ, Vilmann P, Giovannini M, Chang KJ, Wiersema LM. Endosonography-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy: diagnostic accuracy and complication assessment. Gastroenterology. 1997;112:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70164-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khalid A, Nodit L, Zahid M, Bauer K, Brody D, Finkelstein SD, McGrath KM. Endoscopic ultrasound fine needle aspirate DNA analysis to differentiate malignant and benign pancreatic masses. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:2493–2500. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abraham SC, Wilentz RE, Yeo CJ, Sohn TA, Cameron JL, Boitnott JK, Hruban RH. Pancreaticoduodenectomy (Whipple resections) in patients without malignancy: are they all 'chronic pancreatitis'? Am J Surg Pathol. 2003;27:110–120. doi: 10.1097/00000478-200301000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weber SM, Cubukcu-Dimopulo O, Palesty JA, Suriawinata A, Klimstra D, Brennan MF, Conlon K. Lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis: inflammatory mimic of pancreatic carcinoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2003;7:129–137; discussion 137-139. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(02)00148-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]