Abstract

Objective

Lifestyle interventions produce short-term improvements in glycemia and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes, but no long-term data are available. We examined the effects of a lifestyle intervention on changes in weight, fitness and cardiovascular (CVD) risk factors over 4 years.

Research Design and Methods

Look AHEAD is a multi-center randomized clinical trial comparing the effects of intensive lifestyle intervention (ILI) and diabetes support and education (DSE, control group) on the incidence of major CVD events in 5145 individuals with type diabetes, aged 45 to 76 years, who were overweight or obese (BMI > 25 kg/m2). Participants have ongoing intervention and annual assessments.

Results

Averaged across four years of follow-up, participants in ILI had greater percent weight losses than those in DSE (−6.15% vs −0.88%, p<.0001) and greater improvements in fitness (12.74% vs. 1.96%, p < .0001), HbA1c (A1c, −0.36% vs. 0.09%, p<.0001), systolic blood pressure (SBP, −5.33 vs. −2.97 mmHg, p<.0001), diastolic blood pressure (DBP, −2.92 vs. −2.48 mmHg, p<.012), HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C, 3.67 vs. 1.97 mg/dl, p<.0001), and triglycerides (−25.56 vs. −19.75 mg/dl, p<.0006). Reductions in LDL-C were greater in DSE than ILI (−11.27 vs. −12.84 mg/dl, p=.009), but adjusted for medication use, changes in LDL-C did not differ between the two groups. Although the greatest benefits were often seen at 1 year, ILI participants still had greater improvements than DSE in weight, fitness, HbA1c, SBP, and HDL-C at 4 years.

Conclusions

Intensive lifestyle intervention can produce and maintain significant weight losses and improvements in fitness in individuals with type 2 diabetes. Across four years of follow-up, those in ILI had better overall levels of glycemic control, blood pressure, HDL-C and triglycerides, and thus spent considerable time with lower CVD risk. Whether this translates to reduction in CVD events will ultimately be addressed by the Look AHEAD study.

INTRODUCTION

Improving glycemic control and cardiovascular disease risk factors in the population with type 2 diabetes is critical for prevention of long-term vascular complications of the disease. This has led to increased emphasis on screening and medical management of blood pressure, lipids, and glycemic control. Lifestyle-based weight loss interventions are also recommended to improve glycemic control and risk factors, but the evidence supporting the efficacy of lifestyle approaches is limited to short-term studies of typically under one year.1–4 With recent improvements in behavioral weight loss interventions5, 6 and increased recognition of the impact of lifestyle approaches for prevention of diabetes, it is timely to examine the longer term effects of these interventions on changes in glycemic control and cardiovascular risk factors in individuals with diabetes.

The Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) Study is examining the long-term impact of an intensive lifestyle intervention, compared with usual care, on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in 5,145 overweight or obese individuals with type 2 diabetes.7 We have previously reported on the beneficial effects of the lifestyle intervention at one year.1 This report examines the changes in weight, fitness, glycemic control and cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk factors over 4 years for participants in the intensive lifestyle intervention compared with diabetes support and education.

METHODS

Participants

As reported previously,7 participants for Look AHEAD were recruited at 16 centers in the United States and were required to be 45–76 years of age (increased to 55–75 years in year 2 of randomization) and to have a BMI of ≥25 (≥27 in patients on insulin), HbA1c <11%, SBP <160 mmHg, DBP <100 mmHg, and triglycerides 003C600 mg/dl. The goal was to recruit approximately equal numbers of men and women and > 33% from racial and ethnic minority groups. Participants were required to successfully complete a maximal graded exercise test, two weeks of self-monitoring, and attend a Look AHEAD diabetes education session. All participants signed a consent form approved by their local Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Interventions

Participants were randomly assigned by center to Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) or Diabetes Support and Education (DSE). The intensive lifestyle intervention8 included diet modification and physical activity and was designed to induce at least a 7% weight loss at year 1 and to maintain this weight loss in subsequent years. ILI participants were assigned a calorie goal (1200–1800 based on initial weight), with <30% of total calories from fat (< 10% from saturated fat) and a minimum of 15% of total calories from protein. To increase dietary adherence, a portion-controlled diet was used, with liquid meal replacements provided free and recommendations to use other portion-controlled items. The goal was at least 175 minutes of physical activity per week, using activities similar in intensity to brisk walking. Behavioral strategies, including self-monitoring, goal setting and problem solving were stressed.

Participants in ILI were seen weekly for the first 6 months and 3 times per month for the next 6 months, with a combination of group and individual contacts. During years 2–4, participants were seen individually at least once a month, contacted another time each month by phone or e-mail, and offered a variety of centrally-approved group classes. At each session, participants were weighed, self-monitoring records were reviewed, and a new lesson was presented, following a standardized treatment protocol.

Participants in DSE were invited to three group sessions each year. These sessions utilized a standardized protocol and focused on diet, physical activity, or social support. Information on behavioral strategies was not presented and participants were not weighed at these sessions.

For participants in both ILI and DSE, the participant’s own physicians provided all medical care and made changes in medications, with the exception of temporary changes in diabetes medication during periods of intensive weight loss in ILI.

Assessments

Assessments were completed annually and a $100 honorarium was provided. All measures were obtained by certified staff masked to the participants’ intervention assignment. Weight and height were measured in duplicate using a digital scale and stadiometer. Blood pressure was measured in duplicate using an automated device. All blood work was completed after at least a 12-h fast and was analyzed by the Central Biochemistry Laboratory (Northwest Lipid Research Laboratories, University of Washington, Seattle, WA) using standardized laboratory procedures for measuring HbA1c, total cholesterol, HDL-C, and triglycerides. LDL-C was estimated using the Friedewald equation.9 Participants brought all their prescription medications to their assessments to accurately record use of medications. A maximal graded exercise test was administered at baseline and a submaximal exercise test at years 1 and 4.10 Changes in fitness were computed as the difference between estimated METS when the participants achieved or exceeded 80% of age-predicted maximal heart rate or an RPE of ≥ 16 at baseline and at the subsequent assessment.

Statistical Analyses

Means reported at baseline are unadjusted averages. All tests of group differences were based on the intent-to-treat principle. Mixed effects analysis of covariance models were used to obtain adjusted mean changes for each outcome at annual visits 1–4, except fitness which was measured only at years 1 and 4. For binary outcomes, generalized estimating equation (GEE) models were used. The intervention effect was estimated as the average difference between arms across all visits, with baseline level of the outcome, clinical center, an indicator of visit for the repeated outcome measures, and intervention assignment included in the model. Adjustment for post-randomization medication use was done using an indicator for use of medication at each follow-up visit. The LDL cholesterol data are presented with and without adjustment for medication use, since this is the only outcome where adjusting for medication use affected the findings. The mixed effects maximum likelihood and GEE analysis of repeated outcomes was carried out in Proc Mixed of SAS, Version 9, using a 0.05 alpha level. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to account for correlation between repeated outcomes, except for triglycerides which required a first order autoregressive structure.

RESULTS

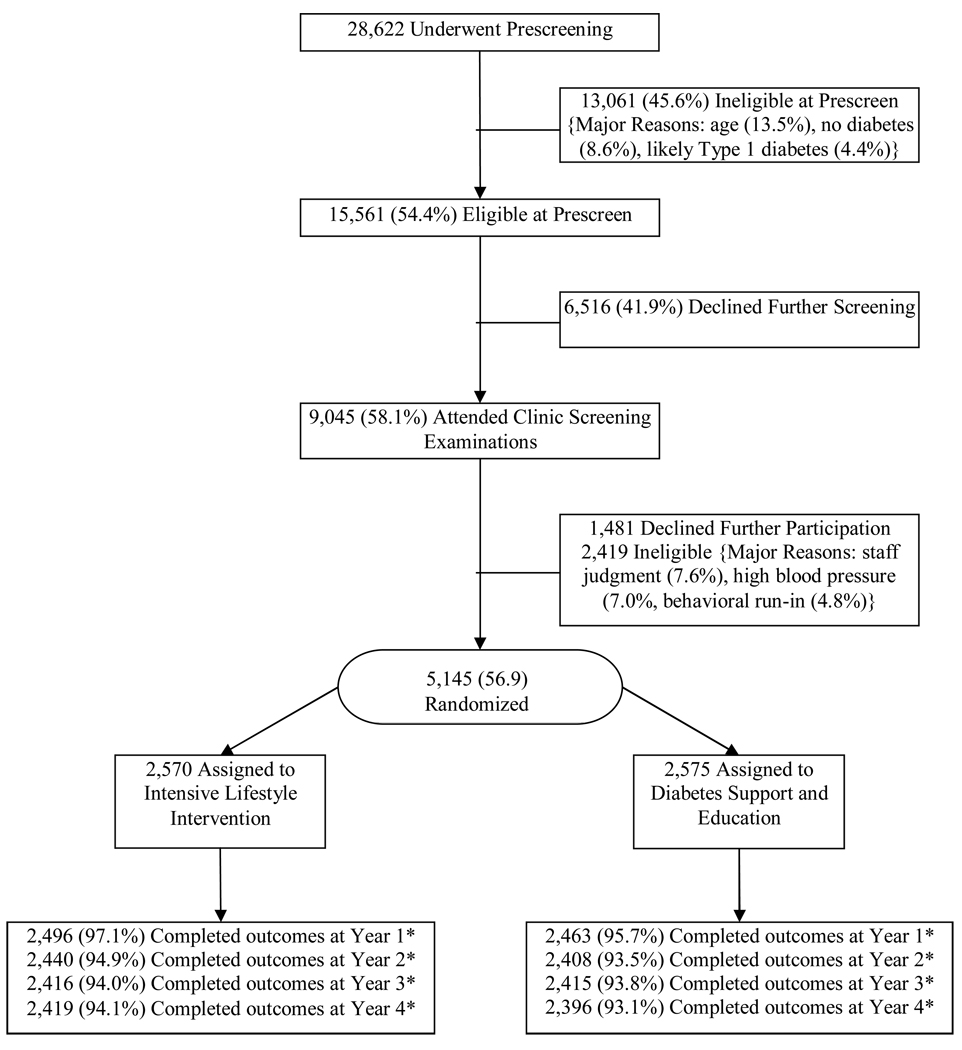

A total of 5145 participants were randomized: 2570 to ILI and 2575 to DSE. The baseline characteristics of these participants have been described in detail.11 Overall, 59% of the participants were women; 37% were from racial or ethnic minorities; 14% reported a history of CVD at baseline, the average age was 58.7 ± 6.8 (Mean ± SD), and the average BMI was 36 ± 5.9 kg/m2. Over 93% of participants were assessed at each of the four years (Fig 1).

Figure 1.

Participant flow

*The remaining participants include missed visits, withdrawals, or deaths.

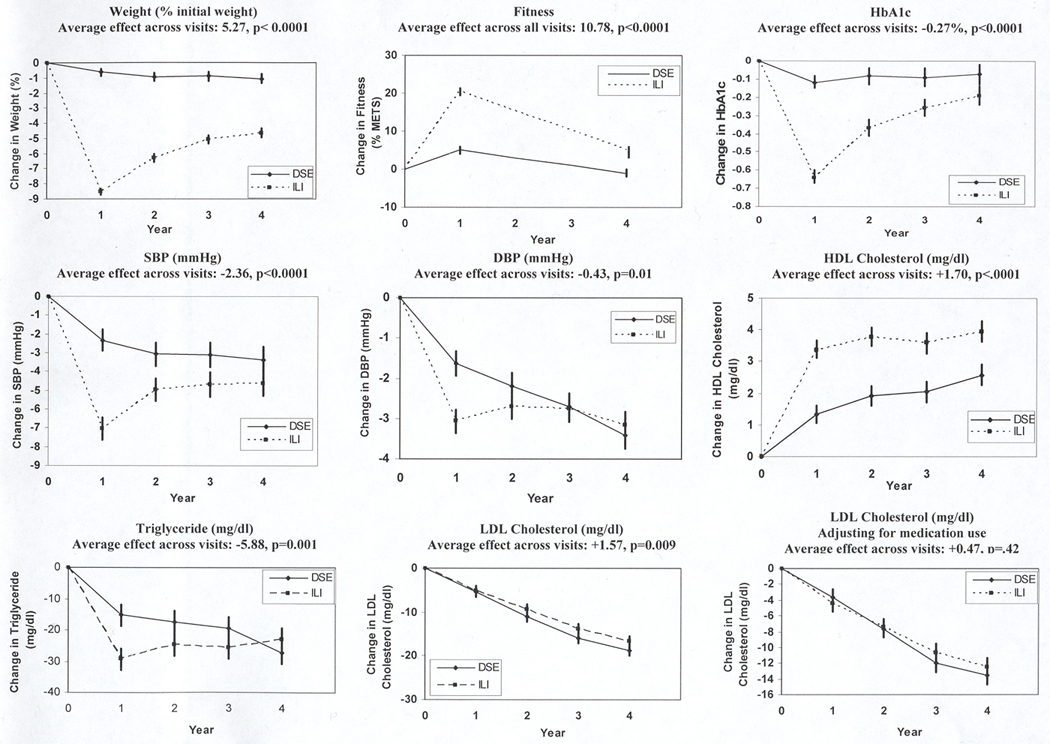

Averaged over the four years, participants in ILI experienced significantly greater improvements in weight, fitness, glycemic control, blood pressure, HDL-C and triglycerides than those in DSE (Table 1). The DSE group experienced greater overall reductions in LDL-C but after adjusting for medication use, changes in LDL-C did not differ between ILI and DSE.

Table 1.

Mean changes in weight, fitness, and CVD risk factors in Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) and Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) and the difference between the two groups averaged over the four years

| Measure | Mean Change DSE | Mean Change ILI | Mean Difference ILI -DSE |

p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weight (% initial weight) | −0.88 (−1.12, −0.64) | −6.15 (−6.39, −5.91) | −5.27 | <0.0001 |

| Fitness (% METS) | 1.96 (1.07,2.85) | 12.74 (11.87, 13.62) | 10.78 | <0.0001 |

| HbA1c1 | −0.09 (−0.13, −0.06) | −0.36 (−0.40, −0.33) | −0.27 | <0.0001 |

| SBP (mmHg)1 | −2.97 (−3.44, −2.49) | −5.33 (−5.80, −4.86) | −2.36 | <0.0001 |

| DBP (mmHg)1 | −2.48 (−2.73, −2.24) | −2.92 (−3.16, −2.68) | −0.43 | 0.012 |

| HDL Cholesterol (mg/dl)1 | 1.97 (1.73, 2.22) | 3.67 (3.43, 3.91) | +1.70 | <0.0001 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dl)1 | −19.75 (−22.11, −17.39) | −25.56 (−27.91, −23.21) | −5.81 | 0.0006 |

| LDL Cholesterol (mg/dl) | −12.84 (−13.67, −12.00) | −11.27 (−12.10, 10.44) | +1.57 | 0.009 |

| LDL Cholesterol (adjusting for medication use) (mg/dl) | −9.22 (−10.04, −8.39) | −8.75 (−9.56, −7.94) | +0.47 | 0.42 |

Data presented are average effects unadjusted for medication use.

Adjusting for baseline use of medications or changes over time did not influence the average effect or the p-value. For LDL-cholesterol, the data are presented with and without medication adjustments.

Changes in weight and risk factors for DSE and ILI participants at each of the 4 years are shown in Figure 2 (see Appendix 1 for detailed data). Weight losses in ILI were significantly greater than in DSE at each year. The mean maximal weight loss (8.6%) for the ILI group was reached at year 1 and participants in ILI maintained a mean weight loss of 4.7% compared with 1.1% in DSE at 4 years (p<.0001).

Figure 2.

Changes in Weight, HbA1c, Blood Pressure, HDL-C, Triglycerides, and LDL-C (unadjusted and adjusted for medication use).

Between baseline and year 1, fitness increased by 20.4% in ILI participants and by 5.0% in DSE (p<.0001). At year 4, the fitness level of ILI participants was still 5.1% over baseline, whereas DSE participants were 1.1% below baseline (p<.0001)

Although the differences in HbA1c between groups were greatest at year 1, the ILI group had significantly greater reductions than DSE at each of the 4 years (Fig 2; all p-values <.001). The greater improvements in HbA1c in ILI occurred despite their lower use of diabetes drugs (Table 2). Among those not using any diabetes drug (insulin or oral agents) at baseline, a larger proportion of DSE compared with ILI participants started on these medications each year. Likewise, among those using diabetes medications at baseline, more participants remained on these medications in DSE than in ILI. The same pattern occurred for those using insulin.

Table 2.

Proportion of Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) and Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) participants who initiate or terminate use of medication for diabetes, hypertension, or lipid lowering

| Among those not using at baseline |

Among those using at baseline |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DSE | ILI | P value | DSE | ILI | P value | |

| Diabetes Medication | ||||||

| Baseline | N = 348 | N = 354 | N = 2208 | N = 2202 | ||

| Year 1 | 33% | 10% | <.0001 | 97% | 89% | <.0001 |

| Year 2 | 46% | 17% | <.0001 | 96% | 88% | <.0001 |

| Year 3 | 59% | 27% | <.0001 | 95% | 89% | <.0001 |

| Year 4 | 67% | 42% | <.0001 | 96% | 91% | <.0001 |

| Insulin | ||||||

| Baseline | N = 2167 | N = 2190 | N = 408 | N = 380 | ||

| Year 1 | 4% | 2% | <.0001 | 92% | 81% | <.0001 |

| Year 2 | 7% | 3% | <.0001 | 86% | 76% | <.0001 |

| Year 3 | 9% | 4% | <.0001 | 86% | 78% | <.0001 |

| Year 4 | 12% | 7% | <.0001 | 88% | 77% | <.0001 |

| Hypertension Medication | ||||||

| Baseline | N = 684 | N = 661 | N = 1872 | N = 1895 | ||

| Year 1 | 22% | 16% | 0.0137 | 90% | 81% | <.0001 |

| Year 2 | 32% | 25% | 0.0052 | 90% | 81% | <.0001 |

| Year 3 | 40% | 33% | 0.0120 | 91% | 83% | <.0001 |

| Year 4 | 47% | 43% | 0.1473 | 93% | 85% | <.0001 |

| Lipid Lowering Medication | ||||||

| Baseline | N = 1313 | N = 1310 | N = 1243 | N = 1246 | ||

| Year 1 | 25% | 18% | <.0001 | 92% | 90% | 0.0820 |

| Year 2 | 40% | 29% | <.0001 | 91% | 89% | 0.5609 |

| Year 3 | 47% | 39% | <.0001 | 89% | 90% | 0.2743 |

| Year 4 | 53% | 47% | 0.0054 | 91% | 90% | 0.5276 |

Participants in ILI achieved significantly greater reductions in SBP than participants in DSE at all 4 years. However, the magnitude of the difference between arms decreased over time (Figure 2). Likewise improvements in DBP were initially greater in the ILI group than DSE, but differences between groups were no longer significant at year 4 (Table 2). Fewer ILI than DSE participants started on hypertensive medications at years 1, 2, and 3.

HDL-C increased gradually over the 4 years in both DSE and ILI, with significantly greater increases in ILI than in DSE at each time point and a fairly consistent difference between the two groups over the four years (Figure 2). The ILI group also experienced significantly greater reductions in triglycerides during the early years of the study, but the two groups did not differ significantly at year 4.

Both the ILI and the DSE group had significant reductions in unadjusted LDL-C at years 1 and 2, with no significant differences between the two groups. However by years 3 and 4, significant differences emerged in the unadjusted analyses (p<.01), with DSE participants experiencing greater decreases in LDL-cholesterol than ILI. This difference was related to the greater use of lipid lowering medications, specifically statins, in the DSE group (Table 2). After adjusting for use of lipid-lowering medications at baseline and annually, the changes in LDL cholesterol were not significantly different between the ILI and DSE group at any of the 4 years or averaged across the 4 years.

The proportions of participants achieving the ADA goals for HbA1c, BP, and LDL-C in each year of the trial are presented in Table 3. A significantly greater proportion of ILI participants met the ADA goal for HbA1c at each year and for blood pressure at years 1, 2 and 3. The percent of participants achieving the ADA goals for LDL-cholesterol did not differ until year 4, where 65% of DSE participants compared with 61% in ILI (p=.01) met this goal.

Table 3.

Proportion of participants in Diabetes Support and Education (DSE) and Intensive Lifestyle Intervention (ILI) that achieved the ADA treatment goals1 at baseline and years 1 – 4

| DSE | ILI | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | |||

| Baseline | 45% | 47% | |

| Year 1 | 50% | 72% | <.0001 |

| Year 2 | 51% | 63% | <.0001 |

| Year 3 | 51% | 60% | <.0001 |

| Year 4 | 51% | 57% | <.0001 |

| Blood Pressure | |||

| Baseline | 50% | 54% | |

| Year 1 | 57% | 69% | <.0001 |

| Year 2 | 60% | 64% | 0.0033 |

| Year 3 | 60% | 63% | 0.0490 |

| Year 4 | 61% | 63% | 0.0904 |

| LDL-C | |||

| Baseline | 37% | 37% | |

| Year 1 | 45% | 44% | 0.3576 |

| Year 2 | 53% | 51% | 0.3686 |

| Year 3 | 60% | 58% | 0.0682 |

| Year 4 | 65% | 61% | 0.0134 |

The ADA treatment goals are as follows: hbA1c < 7%, BP < 130/80 mm/Hg and LDL-C < 100 mg/dL

CONCLUSIONS

Look AHEAD is the first study to examine the effects of an intensive lifestyle intervention through 4 years of follow-up in a large cohort of overweight and obese individuals with type 2 diabetes. This study shows that lifestyle interventions can produce long term weight loss and improvement in fitness and sustained beneficial effects on CVD risk factors. Across the four years, the intensive lifestyle group experienced significantly greater average improvements in all risk factors, except LDL-cholesterol. Although the differences between the two groups was greatest initially and decreased over time for several measures, the differences between the groups averaged over the four years were substantial (Table 1) and indicate that the intervention group spent a considerable time at lower CVD risk.

The average weight losses achieved in the intensive lifestyle intervention at one year (8.6%) were greater than those seen in other multi-center lifestyle trials.5, 12, 13 Although few studies report weight loss data for two or more years of follow-up, the Look AHEAD results at year 2 (6.4%), 3 (5.1%) and year 4 (4.7%) appear comparable or better than those reported previously.5, 14–16 The weight losses in Look AHEAD are impressive in light of the perception that individuals with diabetes have more difficulty losing weight than do their non-diabetic counterparts.17

Maintenance of weight loss has always been a major problem in behavioral treatments of obesity.18, 19 Thus it is interesting to note that weight regain may be slowing over time in Look AHEAD. Whereas participants regained approximately 25% of their weight losses between years 1 and 2 and 20% between years 2 and 3, they regained only 8% of their weight loss between years 3 and 4. The positive effects of the Look AHEAD intervention on weight loss may reflect the ongoing intensive contact,20 combination of group and individual contact, use of meal replacement products, and higher goals prescribed for weight loss.6

Since there have been no intervention studies reporting fitness changes beyond one year for participants with diabetes,21 Look AHEAD provides unique data on long-term changes in fitness. At year 4 the ILI group had maintained a 5% improvement in fitness whereas the control group was below their baseline. The improvements in fitness seen in the ILI group exceed those reported previously for patients with type 2 diabetes in response to a 52 week diet plus exercise intervention.22 The sustained improvements in fitness are important in light of the large number of studies showing that fitness levels are associated with CVD and all-cause mortality.23–26

Averaged across the 4 years, the intervention had significant effects relative to the control group for every cardiovascular risk factor, except LDL-cholesterol. Whereas medications typically address only one risk factor, the lifestyle intervention produced positive changes in glycemic control, blood pressure, and lipids simultaneously. Thus across this time period, participants in the ILI group had lower exposure to a number of potentially negative effects of elevated CVD risk factors.

The improvements in risk factors can also be viewed at each annual visit separately to determine the duration of the effect. Compared with the DSE group, the intervention produced sustained positive effects for four years on glycemic control, systolic blood pressure and HDL-C. The effects on DBP and triglycerides were maintained for only 2–3 years, respectively. We have found no prior intervention studies with individuals with diabetes followed for as long as four years. Based on studies with non-diabetic subjects, the long-term effects of the lifestyle intervention in Look AHEAD are consistent with or greater than those reported previously in other randomized trials with 2 to 3 year follow-up periods or in meta-analyses for blood pressure,13, 27, 28 triglycerides,14, 15, 28 and HDL-C.14, 15, 29

The impact of the intervention on several of the risk factors (HbA1c and SBP) was greatest at year 1, followed by recidivism toward baseline levels. This pattern is likely due in part to the regain of weight and decreases in changes in fitness from years 1 to 4. It may also relate to the stronger effect of weight loss on CVD risk factors immediately after weight loss than at longer time intervals even in those who maintain their weight loss in full.30, 31 In the Swedish Obesity Study (SOS) much larger weight losses achieved through gastric surgery led to short-term improvements in CVD risk factors, which were not necessarily sustained long-term;32 despite this, there were marked benefits of weight loss on cardiovascular mortality.33 The decrease in the beneficial effects of lifestyle, relative to DSE, over the four years for measures such as DBP was also due to the improvements that occurred in the DSE group. These improvements may reflect secular trends in the treatment of CVD risk factors or the effects of diabetes on body weight,34 joining a clinical trial, and/or the beneficial effects of the educational classes.

In addition to the significant differences between groups in the levels of the CVD risk factors, the intervention also resulted in fewer participants in the lifestyle group starting on medications to achieve this control. This was particularly apparent for diabetes medications, especially insulin. Thus, in addition to health benefits, the intervention may result in both health benefits and cost-savings due to decreased medication use.

Of particular note is the sustained effect of lifestyle intervention on HDL-cholesterol. In contrast to several other risk factors, the effect for HDL-cholesterol of the intensive lifestyle intervention relative to the control group was as great at year 4 as it had been at year 1. At each of the 4 years, HDL-C in the lifestyle group was approximately 8–9% higher than baseline levels, whereas the control group was 3–6% above baseline. Early randomized controlled trials35, 36 showed that the combination of weight loss and increased physical activity had the greatest impact on HDL-cholesterol levels and parallel the type of approach used in Look AHEAD. Given the evidence from the Helsinki Heart Study of a strong association between increases in HDL-C and reduced heart disease,37 the effects of lifestyle intervention on HDL-C may provide important long-term cardiovascular benefit.

The finding from Look AHEAD of greater benefits of lifestyle intervention for HDL-C than for LDL-C is consistent with prior studies.2 Levels of LDL-cholesterol decreased consistently over the four years of follow-up in both groups in Look AHEAD, likely due to the large number of participants in both groups who were started on lipid lowering medications, typically statins and reflecting the increasing emphasis given to treating LDL-cholesterol in individuals with diabetes.38 After adjusting for the use of lipid lowering medications, no significant differences in LDL-cholesterol were observed either initially or at follow-up.

In conclusion, the intensive lifestyle intervention was successful in producing sustained weight losses and improvements in cardiovascular fitness through 4 years of follow-up. The intervention group also experienced significantly greater improvements than the usual care group in all CVD risk factors averaged across this time period, with the exception of LDL-C, where after adjusting for medication use, improvements were similar in the two groups. The lifestyle group in Look AHEAD is being offered ongoing intervention activities in an effort to sustain the improvements in risk factors. The critical question is whether these differences between groups in risk factors will translate into differences in the development of cardiovascular disease. These results will not be available for several additional years. However, we note that the magnitude of the effects we have observed for fitness, HDL-C, HbA1c and blood pressure have been associated with decreased cardiovascular events and mortality in prior medication trials and observational studies.24, 25, 39–41 Moreover, there may be long-term beneficial effects from the four year period in which lifestyle participants have been exposed to lower CVD risk factors as seen in other clinical trials.42, 43 Longer follow-up will allow us to determine whether the differences between groups in cardiovascular risk factors can be maintained and whether lifestyle intervention has positive effects on cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Supplementary Material

Appendix

Authors

Rena R. Wing, PhD; Judy L. Bahnson, BA, CCRP; George A. Bray, MD; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH; Mace Coday, PhD; Caitlin Egan, MS; Mark A. Espeland, PhD; John P. Foreyt, PhD; Edward W. Gregg, PhD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Helen Hazuda, PhD; James O. Hill, PhD; Edward S. Horton, MD; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; John Jakicic, PhD; Robert W. Jeffery, PhD; Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH; Steven Kahn MB, ChB; Tina Killean, BS; Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD; Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH; Cathy Manus, LPN; Barbara J. Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE; Sara Michaels, MD; Maria Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE; David M. Nathan, MD; Jennifer Patricio, MS; Anne Peters, MD; Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD; Henry Pownall, PhD; David Reboussin, PhD; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD; Richard Rubin, PhD; Monika Safford, MD; Tricia Skarphol, MA; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD; Thomas A. Wadden, PhD; Lynne Wagenknecht, DrPH; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE; Delia S. West, PhD; Donald Williamson, PhD; Susan Z.Yanovski, MD

Look AHEAD Research Group at Year 4

Clinical Sites

The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions

Frederick L. Brancati, MD, MHS1; Lee Swartz2; Lawrence Cheskin, MD3; Jeanne M. Clark, MD, MPH3; Kerry Stewart, EdD3; Richard Rubin, PhD3; Jean Arceci, RN; Suzanne Bau; Jeanne Charleston, RN; Danielle Diggins; Mia Johnson; Joyce Lambert; Kathy Michalski, RD; Daron Niggetts; Chanchai Sapun

Pennington Biomedical Research Center

George A. Bray, MD1; Kristi Rau2; Allison Strate, RN2; Frank L. Greenway, MD3; Donna H. Ryan, MD3; Donald Williamson, PhD3; Brandi Armand, LPN; Jennifer Arceneaux; Amy Bachand, MA; Michelle Begnaud, LDN, RD, CDE; Betsy Berhard; Elizabeth Caderette; Barbara Cerniauskas, LDN, RD, CDE; David Creel, MA; Diane Crow; Crystal Duncan; Helen Guay, LDN, LPC, RD; Carolyn Johnson, Lisa Jones; Nancy Kora; Kelly LaFleur; Kim Landry; Missy Lingle; Jennifer Perault; Cindy Puckett; Mandy Shipp, RD; Marisa Smith; Elizabeth Tucker

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

Cora E. Lewis, MD, MSPH1; Sheikilya Thomas MPH2; Monika Safford, MD3; Vicki DiLillo, PhD; Charlotte Bragg, MS, RD, LD; Amy Dobelstein; Stacey Gilbert, MPH; Stephen Glasser, MD3; Sara Hannum, MA; Anne Hubbell, MS; Jennifer Jones, MA; DeLavallade Lee; Ruth Luketic, MA, MBA, MPH; L. Christie Oden; Janet Raines, MS; Cathy Roche, RN, BSN; Janet Truman; Nita Webb, MA; Casey Azuero, MPH; Jane King, MLT; Andre Morgan

Harvard Center

Massachusetts General Hospital

David M. Nathan, MD1; Enrico Cagliero, MD3; Kathryn Hayward, MD3; Heather Turgeon, RN, BS, CDE2; Linda Delahanty, MS, RD3; Ellen Anderson, MS, RD3; Laurie Bissett, MS, RD; Valerie Goldman, MS, RD; Virginia Harlan, MSW; Theresa Michel, DPT, DSc, CCS; Mary Larkin, RN; Christine Stevens, RN; Kylee Miller, BA; Jimmy Chen, BA; Karen Blumenthal, BA; Gail Winning, BA; Rita Tsay, RD; Helen Cyr, RD; Maria Pinto

Joslin Diabetes Center

Edward S. Horton, MD1; Sharon D. Jackson, MS, RD, CDE2; Osama Hamdy, MD, PhD3; A. Enrique Caballero, MD3; Sarah Bain, BS; Elizabeth Bovaird, BSN, RN; Barbara Fargnoli, MS,RD; Jeanne Spellman, BS, RD; Ann Goebel-Fabbri, PhD; Lori Lambert, MS, RD; Sarah Ledbury, MEd, RD; Maureen Malloy, BS; Kerry Ovalle, MS, RCEP, CDE

Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center

George Blackburn, MD, PhD1; Christos Mantzoros, MD, DSc3; Ann McNamara, RN; Kristina Spellman, RD

University of Colorado Health Sciences Center

James O. Hill, PhD1; Marsha Miller, MS, RD2; Brent Van Dorsten, PhD3; Judith Regensteiner, PhD3; Ligia Coelho, BS; Paulette Cohrs, RN, BSN; Susan Green; April Hamilton, BS, CCRC; Jere Hamilton, BA; Eugene Leshchinskiy; Lindsey Munkwitz, BS; Loretta Rome, TRS; Terra Worley, BA; Kirstie Craul, RD,CDE; Sheila Smith, BS

Baylor College of Medicine

John P. Foreyt, PhD1; Rebecca S. Reeves, DrPH, RD2; Henry Pownall, PhD3; Ashok Balasubramanyam, MBBS3; Peter Jones, MD3; Michele Burrington, RD, RN; Chu-Huang Chen, MD, PhD; Allyson Clark Gardner, MS, RD; Molly Gee, MEd, RD; Sharon Griggs; Michelle Hamilton; Veronica Holley; Jayne Joseph, RD; Julieta Palencia, RN; Jennifer Schmidt; Carolyn White

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center

University of Tennessee East

Karen C. Johnson, MD, MPH1; Carolyn Gresham, RN2; Stephanie Connelly, MD, MPH3; Amy Brewer, RD, MS; Mace Coday, PhD; Lisa Jones, RN; Lynne Lichtermann, RN, BSN; Shirley Vosburg, RD, MPH; and J. Lee Taylor, MEd, MBA

University of Tennessee Downtown

Abbas E. Kitabchi, PhD, MD1; Ebenezer Nyenwe, MD3; Helen Lambeth, RN, BSN2; Amy Brewer, MS, RD,LDN; Debra Clark, LPN; Andrea Crisler, MT; Debra Force, MS, RD, LDN; Donna Green, RN; Robert Kores, PhD

University of Minnesota

Robert W. Jeffery, PhD1; Carolyn Thorson, CCRP2; John P. Bantle, MD3; J. Bruce Redmon, MD3; Richard S. Crow, MD3; Scott Crow, MD3; Susan K Raatz, PhD, RD3; Kerrin Brelje, MPH, RD; Carolyne Campbell; Jeanne Carls, MEd; Tara Carmean-Mihm, BA; Julia Devonish, MS; Emily Finch, MA; Anna Fox, MA; Elizabeth Hoelscher, MPH, RD, CHES; La Donna James; Vicki A. Maddy, BS, RD; Therese Ockenden, RN; Birgitta I. Rice, MS, RPh, CHES; Tricia Skarphol, BS; Ann D. Tucker, BA; Mary Susan Voeller, BA; Cara Walcheck, BS, RD

St. Luke’s Roosevelt Hospital Center

Xavier Pi-Sunyer, MD1; Jennifer Patricio, MS2; Stanley Heshka, PhD3; Carmen Pal, MD3; Lynn Allen, MD; Lolline Chong, BS, RD; Marci Gluck, PhD; Diane Hirsch, RNC, MS, CDE; Mary Anne Holowaty, MS, CN; Michelle Horowitz, MS, RD; Nancy Rau, MS, RD, CDE; Dori Brill Steinberg, BS

University of Pennsylvania

Thomas A. Wadden, PhD1; Barbara J Maschak-Carey, MSN, CDE2; Robert I. Berkowitz, MD3; Seth Braunstein, MD, PhD3; Gary Foster, PhD3; Henry Glick, PhD3; Shiriki Kumanyika, PhD, RD, MPH3; Stanley S. Schwartz, MD3; Michael Allen, RN; Yuliis Bell; Johanna Brock; Susan Brozena, MD; Ray Carvajal, MA; Helen Chomentowski; Canice Crerand, PhD; Renee Davenport; Andrea Diamond, MS, RD; Anthony Fabricatore, PhD; Lee Goldberg, MD; Louise Hesson, MSN, CRNP; Thomas Hudak, MS; Nayyar Iqbal, MD; LaShanda Jones-Corneille, PhD; Andrew Kao, MD; Robert Kuehnel, PhD; Patricia Lipschutz, MSN; Monica Mullen, RD, MPH

University of Pittsburgh

John M. Jakicic, PhD1, David E. Kelley, MD1; Jacqueline Wesche-Thobaben, RN, BSN, CDE2; Lewis H. Kuller, MD, DrPH3; Andrea Kriska, PhD3; Amy D. Otto, PhD, RD, LDN3, Lin Ewing, PhD, RN3, Mary Korytkowski, MD3, Daniel Edmundowicz, MD3; Monica E. Yamamoto, DrPH, RD, FADA3; Rebecca Danchenko, BS; Barbara Elnyczky; David O. Garcia, MS; George A. Grove, MS; Patricia H. Harper, MS, RD, LDN; Susan Harrier, BS; Nicole L. Helbling, MS, RN; Diane Ives, MPH; Juliet Mancino, MS, RD, CDE, LDN; Anne Mathews, PhD, RD, LDN; Tracey Y. Murray, BS; Joan R. Ritchea; Susan Urda, BS, CTR; Donna L. Wolf, PhD

The Miriam Hospital/Brown Medical School

Rena R. Wing, PhD1; Renee Bright, MS2; Vincent Pera, MD3; John Jakicic, PhD3; Deborah Tate, PhD3; Amy Gorin, PhD3; Kara Gallagher, PhD3; Amy Bach, PhD; Barbara Bancroft, RN, MS; Anna Bertorelli, MBA, RD; Richard Carey, BS; Tatum Charron, BS; Heather Chenot, MS; Kimberley Chula-Maguire, MS; Pamela Coward, MS, RD; Lisa Cronkite, BS; Julie Currin, MD; Maureen Daly, RN; Caitlin Egan, MS; Erica Ferguson, BS, RD; Linda Foss, MPH; Jennifer Gauvin, BS; Don Kieffer, PhD; Lauren Lessard, BS; Deborah Maier, MS; JP Massaro, BS; Tammy Monk, MS; Rob Nicholson, PhD; Erin Patterson, BS; Suzanne Phelan, PhD; Hollie Raynor, PhD, RD; Douglas Raynor, PhD; Natalie Robinson, MS, RD; Deborah Robles; Jane Tavares, BS

The University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio

Steven M. Haffner, MD1; Maria G. Montez, RN, MSHP, CDE2; Carlos Lorenzo, MD3; Charles F. Coleman, MS, RD; Domingo Granado, RN; Kathy Hathaway, MS, RD; Juan Carlos Isaac, RC, BSN; Nora Ramirez, RN, BSN; Ronda Saenz, MS, RD

VA Puget Sound Health Care System / University of Washington

Steven Kahn MB, ChB1; Brenda Montgomery, RN, MS, CDE2; Robert Knopp, MD3; Edward Lipkin, MD3; Dace Trence, MD3; Terry Barrett, BS; Joli Bartell, BA; Diane Greenberg, PhD; Anne Murillo, BS; Betty Ann Richmond, MEd; Jolanta Socha, BS; April Thomas, MPH, RD; Alan Wesley, BA

Southwestern American Indian Center, Phoenix, Arizona and Shiprock, New Mexico

William C. Knowler, MD, DrPH1; Paula Bolin, RN, MC2; Tina Killean, BS2; Cathy Manus, LPN3; Jonathan Krakoff, MD3; Jeffrey M. Curtis, MD, MPH3; Justin Glass, MD3; Sara Michaels, MD3; Peter H. Bennett, MB, FRCP3; Tina Morgan3; Shandiin Begay, MPH; Paul Bloomquist, MD; Teddy Costa, BS; Bernadita Fallis RN, RHIT, CCS; Jeanette Hermes, MS,RD; Diane F. Hollowbreast; Ruby Johnson; Maria Meacham, BSN, RN, CDE; Julie Nelson, RD; Carol Percy, RN; Patricia Poorthunder; Sandra Sangster; Nancy Scurlock, MSN, ANP-C, CDE; Leigh A. Shovestull, RD, CDE; Janelia Smiley; Katie Toledo, MS, LPC; Christina Tomchee, BA; Darryl Tonemah, PhD

University of Southern California

Anne Peters, MD2; Valerie Ruelas, MSW, LCSW2; Siran Ghazarian Sengardi, MD2; Kathryn (Mandy) Graves Hillstrom, EdD,RD,CDE; Kati Konersman, MA, RD, CDE; Sara Serafin-Dokhan

Coordinating Center

Wake Forest University

Mark A. Espeland, PhD1; Judy L. Bahnson, BA, CCRP3; Lynne E. Wagenknecht, DrPH3; David Reboussin, PhD3; W. Jack Rejeski, PhD3; Alain G. Bertoni, MD, MPH3; Wei Lang, PhD3; Michael S. Lawlor, PhD3; David Lefkowitz, MD3; Gary D. Miller, PhD3; Patrick S. Reynolds, MD3; Paul M. Ribisl, PhD3; Mara Vitolins, DrPH3; Haiying Chen, PhD3; Delia S. West, PhD3; Lawrence M. Friedman, MD3; Brenda L. Craven, MS, CCRP2; Kathy M. Dotson, BA2; Amelia Hodges, BS, CCRP2; Carrie C. Williams, BS, CCRP2; Andrea Anderson, MS; Jerry M. Barnes, MA, Mary Barr; Daniel P. Beavers, PhD; Tara Beckner; Cralen Davis, MS; Thania Del Valle-Fagan, MD; Patricia A. Feeney, MS; Candace Goode; Jason Griffin, BS; Lea Harvin, BS; Patricia Hogan, MS; Sarah A. Gaussoin, MS; Mark King, BS; Kathy Lane, BS; Rebecca H. Neiberg, MS; Michael P. Walkup, MS; Karen Wall, AAS; Terri Windham

Central Resources Centers

DXA Reading Center, University of California at San Francisco

Michael Nevitt, PhD1; Ann Schwartz, PhD2; John Shepherd, PhD3; Michaela Rahorst; Lisa Palermo, MS, MA; Susan Ewing, MS; Cynthia Hayashi; Jason Maeda, MPH

Central Laboratory, Northwest Lipid Metabolism and Diabetes Research Laboratories

Santica M. Marcovina, PhD, ScD1; Jessica Chmielewski2; Vinod Gaur, PhD4

ECG Reading Center, EPICARE, Wake Forest University School of Medicine

Elsayed Z. Soliman MD, MSc, MS1; Ronald J. Prineas, MD, PhD1; Charles Campbell2; Zhu-Ming Zhang, MD3; Teresa Alexander; Lisa Keasler; Susan Hensley; Yabing Li, MD

Diet Assessment Center, University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, Center for Research in Nutrition and Health Disparities

Robert Moran, PhD1

Hall-Foushee Communications, Inc.

Richard Foushee, PhD; Nancy J. Hall, MA

Federal Sponsors

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

Mary Evans, PhD; Barbara Harrison, MS; Van S. Hubbard, MD, PhD; Susan Z.Yanovski, MD; Robert Kuczmarski, PhD

National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute

Lawton S. Cooper, MD, MPH; Peter Kaufman, PhD, FABMR

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Edward W. Gregg, PhD; David F. Williamson, PhD; Ping Zhang, PhD

Funding and Support

This study is supported by the Department of Health and Human Services through the following cooperative agreements from the National Institutes of Health: DK57136, DK57149, DK56990, DK57177, DK57171, DK57151, DK57182, DK57131, DK57002, DK57078, DK57154, DK57178, DK57219, DK57008, DK57135, and DK56992. The following federal agencies have contributed support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; National Institute of Nursing Research; National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities; Office of Research on Women’s Health; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and the Department of Veterans Affairs. This research was supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The Indian Health Service (I.H.S.) provided personnel, medical oversight, and use of facilities. The opinions expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the I.H.S. or other funding sources.

Additional support was received from The Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions Bayview General Clinical Research Center (M01RR02719); the Massachusetts General Hospital Mallinckrodt General Clinical Research Center and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01066); the University of Colorado Health Sciences Center General Clinical Research Center (M01RR00051) and Clinical Nutrition Research Unit (P30 DK48520); the University of Tennessee at Memphis General Clinical Research Center (M01RR0021140); the University of Pittsburgh General Clinical Research Center (GCRC) (M01RR000056), the Clinical Translational Research Center (CTRC) funded by the Clinical & Translational Science Award (UL1 RR 024153) and NIH grant (DK 046204); and the Frederic C. Bartter General Clinical Research Center (M01RR01346)

The following organizations have committed to make major contributions to Look AHEAD: FedEx Corporation; Health Management Resources; LifeScan, Inc., a Johnson & Johnson Company; OPTIFAST® of Nestle HealthCare Nutrition, Inc.; Hoffmann-La Roche Inc.; Abbott Nutrition; and Slim-Fast Brand of Unilever North America.

1Principal Investigator

2Program Coordinator

3Co-Investigator

All other Look AHEAD staffs are listed alphabetically by site.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00017953

REFERENCES

- 1.Look AHEAD Research Group. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007 Jun;30(6):1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NHLBI. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults-The evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6(S2):51S–210S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wing RR, Koeske R, Epstein LH, Nowalk MP, Gooding W, Becker D. Long-term effects of modest weight loss in type II diabetic patients. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1749–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pi-Sunyer FX. Short-term medical benefits and adverse effects of weight loss. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:722–726. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-7_part_2-199310011-00019. 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wadden TA, West DS, Neiberg RH, et al. One-year weight losses in the Look AHEAD study: factors associated with success. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009 Apr;17(4):713–722. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Look AHEAD Research Group. Look AHEAD: Action for Health in Diabetes: Design and methods for a clinical trial of weight loss for the prevention of cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes. Control Clin Trials. 2003;24:610–628. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(03)00064-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Look AHEAD Research Group. The Look AHEAD study: a description of the lifestyle intervention and the evidence supporting it. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006 May;14(5):737–752. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clin Chem. 1972 Jun;18(6):499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jakicic JM, Jaramillo SA, Balasubramanyam A, et al. Effect of a lifestyle intervention on change in cardiorespiratory fitness in adults with type 2 diabetes: results from the Look AHEAD Study. Int J Obes (Lond) 2009 Mar;33(3):305–316. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bray G, Gregg E, Haffner S, et al. Baseline characteristics of the randomized cohort from the Look AHEAD (Action for Health in Diabetes) study. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2006 Dec;3(3):202–215. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2006.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whelton PK, Appel LJ, Espeland MA, et al. Sodium reduction and weight loss in the treatment of hypertension in older persons: A randomized controlled trial of nonpharmacologic interventions in the elderly (TONE) JAMA. 1998;279(11):839–846. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.839. 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. Effects of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hypertension incidence in overweight people with high-normal blood pressure: The Trials of Hypertension Prevention, Phase II. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:657–667. 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shai I, Schwarzfuchs D, Henkin Y, et al. Weight loss with a low-carbohydrate, Mediterranean, or low-fat diet. N Engl J Med. 2008 Jul 17;359(3):229–241. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0708681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sacks FM, Bray GA, Carey VJ, et al. Comparison of weight-loss diets with different compositions of fat, protein, and carbohydrates. N Engl J Med. 2009 Feb 26;360(9):859–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0804748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ley SJ, Metcalf PA, Scragg RK, Swinburn BA. Long-term effects of a reduced fat diet intervention on cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with glucose intolerance. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2004 Feb;63(2):103–112. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2003.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Guare JC, Wing RR, Grant A. Comparison of obese NIDDM and nondiabetic women; short- and long-term weight loss. Obes Res. 1995;3(4):329–335. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1995.tb00158.x. 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Byrne KJ. Efficacy of lifestyle modification for long-term weight control. Obes Res. 2004 Dec;(12 Suppl):151S–162S. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray G, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker, Inc.; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Perri MG, Foreyt JP. Preventing Weight Regain After Weight Loss. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boule NG, Kenny GP, Haddad E, Wells GA, Sigal RJ. Meta-analysis of the effect of structured exercise training on cardiorespiratory fitness in Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetologia. 2003 Aug;46(8):1071–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00125-003-1160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vanninen E, Uusitupa M, Siitonen O, Laitinen J, Lansimies E. Habitual physical activity, aerobic capacity and metabolic control in patients with newly-diagnosed Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: effect of 1-year diet and exercise intervention. Diabetologia. 1992;35:340–346. doi: 10.1007/BF00401201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee CD, Blair SN, Jackson AS. Cardiorespiratory fitness, body composition, and all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Am J Clin Nutr. 1999 Mar;69(3):373–380. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/69.3.373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Church TS, LaMonte MJ, Barlow CE, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness and body mass index as predictors of cardiovascular disease mortality among men with diabetes. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Oct 10;165(18):2114–2120. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.18.2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Blair SN. Cardiorespiratory fitness attenuates the effects of the metabolic syndrome on all-cause and cardiovascular disease mortality in men. Arch Intern Med. 2004 May 24;164(10):1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Janssen I, Ross R, Blair SN. Metabolic syndrome, obesity, and mortality: impact of cardiorespiratory fitness. Diabetes Care. 2005 Feb;28(2):391–397. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.2.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horvath K, Jeitler K, Siering U, et al. Long-term effects of weight-reducing interventions in hypertensive patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Mar 24;168(6):571–580. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.6.571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Perreault L, Ma Y, Dagogo-Jack S, et al. Sex differences in diabetes risk and the effect of intensive lifestyle modification in the Diabetes Prevention Program. Diabetes Care. 2008 Jul;31(7):1416–1421. doi: 10.2337/dc07-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poobalan A, Aucott L, Smith WC, et al. Effects of weight loss in overweight/obese individuals and long-term lipid outcomes--a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2004 Feb;5(1):43–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789x.2004.00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wing RR, Jeffery RW. Effect of modest weight loss on changes in cardiovascular risk factors: Are there differences between men and women or between weight loss and maintenance? Int J Obes. 1995;19:67–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD. Two-year changes in lipids and lipoproteins associated with the maintenance of a 5% TO 10% reduction in initial weight: Some findings and some questions. Obes Res. 1999;7(2):170–171. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00699.x. 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004 Dec 23;351(26):2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, et al. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in Swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007 Aug 23;357(8):741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Looker HC, Knowler WC, Hanson RL. Changes in BMI and weight before and after the development of type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2001 Nov;24(11):1917–1922. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.11.1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wood P, Stefanick M, Williams P, Haskell W. The effects on plasma lipoproteins of a prudent weight-reducing diet, with or without exercise, in overweight men and women. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:461–466. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199108153250703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stefanick ML, Mackey S, Sheehan M, Ellsworth N, Haskell WL, Wood PD. Effects of diet and exercise in men and postmenopausal women with low levels of HDL cholesterol and high levels of LDL cholesterol. N Engl J Med. 1998 Jul 2;339(1):12–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807023390103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Frick MH, Elo O, Haapa K, et al. Helsinki Heart Study: primary-prevention trial with gemfibrozil in middle-aged men with dyslipidemia. Safety of treatment, changes in risk factors, and incidence of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 1987 Nov 12;317(20):1237–1245. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198711123172001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.American Diabetes Association. Vol 32. American Diabetes Association; 2009. Clinical Practice Recommendations. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Selvin E, Marinopoulos S, Berkenblit G, et al. Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004 Sep 21;141(6):421–431. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-141-6-200409210-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vasan RS, Larson MG, Leip EP, et al. Impact of high-normal blood pressure on the risk of cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2001 Nov 1;345(18):1291–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa003417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rubins HB, Robins SJ, Collins D, et al. Gemfibrozil for the secondary prevention of coronary heart disease in men with low levels of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol. Veterans Affairs High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol Intervention Trial Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999 Aug 5;341(6):410–418. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908053410604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Retinopathy and nephropathy in patients with type 1 diabetes four years after a trial of intensive therapy. The Diabetes Control and Complications Trial/Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications Research Group. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 10;342(6):381–389. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002103420603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet. 2006 Nov 11;368(9548):1673–1679. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.