Abstract

To determine the ability of a vaccine formulated with the genital Chlamydia trachomatis, serovar F, native major outer membrane protein (Ct-F-nMOMP), to induce systemic and mucosal immune responses, rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) were immunized three times by the intramuscular (i.m.) and subcutaneous (s.c.) routes using CpG-2395 and Montanide ISA 720 VG, as adjuvants. As controls, another group of M. mulatta was immunized with ovalbumin instead of Ct-F-nMOMP using the same formulation and routes. High levels of Chlamydia-specific IgG and IgA antibodies were detected in plasma, vaginal washes, tears, saliva, and stools from the Ct-F-nMOMP immunized animals. Also, high neutralizing antibody titers were detected in the plasma from these animals. Monkeys immunized with ovalbumin had no detectable Chlamydia-specific antibodies. Furthermore, as measured by a lymphoproliferative assay, significant Chlamydia-specific cell-mediated immune responses were detected in the peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from the rhesus macaques vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP when compared with the animals immunized with ovalbumin. In addition, the levels of two Th1 cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were significantly higher in the animals immunized with Ct-F-nMOMP when compared with those from the monkeys immunized with ovalbumin. To our knowledge, this is the first time that mucosal and systemic immune responses have been investigated in a nonhuman primate model using a subunit vaccine from a human genital C. trachomatis serovar.

Keywords: Chlamydia trachomatis, vaccine, Macaca mulatta, nonhuman primates, systemic and mucosal immune responses

INTRODUCTION

It is estimated that close to 90–100 million new cases of sexually transmitted Chlamydia trachomatis infections occur worldwide each year [1–4]. C. trachomatis is the most prevalent sexually transmitted bacterial pathogen in the USA [1]. These infections affect mainly young individuals, in particular those between 15 and 25 years of age [4]. In females, 60–80% of the patients are asymptomatic [4]. Similarly, a significant number of males, 30–50%, do not have clinical symptoms [4]. Symptomatic females usually present with mucopurulent cervicitis while, in males, urethritis is the most common clinical manifestation. A majority of the individuals resolve the infection and do not develop long-term sequelae. However, severe acute infections and persistent infections may result in long-term sequelae [5–7]. Women may develop long-term sequelae including chronic abdominal pain, ectopic pregnancy and infertility [8, 9]. Mothers who are infected at the time of delivery can transmit the infection to their newborns who can then develop conjunctivitis and pneumonia [5, 10]. In males, the infection is for the most part limited to the lower genitourinary tract and seldom produces long-term sequelae [11–15]. In men that have sex with men, gastrointestinal infections are common [16]. In regions with poor sanitary conditions, C. trachomatis produces trachoma, the most common cause of preventable blindness in the world and lymphogranuloma venereum (LGV), a systemic disease with significant health complications [5, 17]. C. trachomatis also increases the risk of acquiring and transmitting human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and human papillomaviruses (HPV) [18, 19].

Treatment with antibiotics can sometimes cure an acute infection and prevent the development of long-term sequelae [11, 20]. However, antibiotics will not result in the control and/or eradication of these diseases since many individuals are asymptomatic and, even in symptomatic cases certain patients may not respond to therapy, or are treated too late, and as a result they develop long-term sequelae [8, 11]. Furthermore, the use of antibiotics in C. trachomatis infection control programs may result in an increase in the prevalence of the infection, likely by interfering with natural immunity, [21–23]. Therefore, implementing a vaccine appears to be the only approach for controlling C. trachomatis infections.

In the 1960's live and inactivated Chlamydia trachomatis vaccines were tested both in humans and in nonhuman primates for their ability to protect against trachoma [5, 24, 25]. From these trials several conclusions were reached. Some of the vaccination protocols elicited a protective response. However, the protection was found to be short-lived and to be serovar or subgroup specific. In addition in some immunized individuals re-exposure to C. trachomatis resulted in a hypersensitivity reaction that was not serovar-specific. Based on the concerns associated with the hypersensitivity reaction observed during the trachoma vaccine trials, recent efforts have focused on engineering a subunit vaccine [26–28].

Molecular characterization of the structure of the MOMP of C. trachomatis identified this protein as a potential immunogen. MOMP was found to have four variable domains (VD) unique for each serovar and therefore, most likely, accounted for the protection observed during the trachoma trials [29, 30]. Furthermore, MOMP is surface exposed, immunogenic and constitutes 60% of the mass of the outer membrane of C. trachomatis [31, 32]. Unfortunately, attempts to use recombinant MOMP (rMOMP), MOMP-peptides or DNA plasmids expressing MOMP resulted in limited success [27, 28, 33–38]. The possibilities that the conformation of MOMP, or that post-translational modification of this protein, play a role in protection were considered as potential reasons for the failure of these immunizations [27, 28]. To address these possibilities we extracted and purified MOMP directly from C. trachomatis. Using the native trimer of MOMP as the antigen (nMOMP), and adjuvants that induce a predominant Th1 response, we showed strong protection against a respiratory and intrabursal challenges in the murine model and against an ocular infection in the monkey model [39–41]. Based on those studies here, we used the nMOMP from the human genital C. trachomatis F serovar and adjuvants that elicit a biased Th1 response, to vaccinate nonhuman primates to determine if this formulation will elicit systemic and mucosal immune responses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

C. trachomatis serovar F stocks

The genital C. trachomatis serovar F (IC-Cal-3) was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and was grown in HeLa-229 cells using Eagles’ minimal essential medium supplemented with 5% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Density gradient-purified elementary bodies (EB) were stored at −80°C in 0.2 M sucrose, 20 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.4), and 5 mM glutamic acid (SPG) [31]. Bacterial stocks were titrated in HeLa-229 cells.

Preparation of the C. trachomatis serovar F native MOMP

Extraction and purification of the C. trachomatis MOMP serovar F native MOMP (Ct-F-Ct-F-nMOMP) were performed as previously described [40]. The purified Ct-F-nMOMP was refolded by dialysis in 0.1 M phosphate buffer (pH 7.8) containing 2 mM reduced glutathione, 1 mM oxidized glutathione (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), 1 mM EDTA, and 0.05% Z3–14. The protein was then concentrated and fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at room temperature for 2 min. Glycine (Bio-Rad Laboratories) was added to stop the reaction. The Ct-F-nMOMP was concentrated with a Centricon-10 filter (Millipore Corp., Bedford, MA) and dialyzed against a solution containing 20 mM phosphate buffer (pH 7.4), 0.15 M NaCl and 0.05% Z3−14 before using it to immunize the animals. The nMOMP was found to have less than 0.05 EU of LPS per mg of protein using the limulus amoebocyte assay (BioWhittaker, Inc., Walkersville, MD).

Nonhuman primates

Six healthy nulliparous female rhesus monkeys (M. mulatta; ~3 years of age) were used for these studies and housed at the California National Primate Research Center, University of California, Davis. Pre-immunization plasma samples were tested by ELISA and Western blot for the presence of antibodies to Chlamydia and were found to be negative. All animal-related procedures were reviewed and approved in advance by the Animal Care and Use Committee at University of California, Davis. The work was conducted in compliance with the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals, as well as all applicable federal laws and regulations. The facilities are fully accredited by the American Association for Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care.

Vaccination protocol

Following anesthesia (ketamine hydrochloride, 1 mg/kg body weight), three monkeys (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9, and Mmu-3.9) were immunized with Ct-F-nMOMP (100 µg/animal/immunization) in combination with CpG-2395 (400 µg/animal; Coley Pharmaceutical Group; NY, NY) plus Montanide ISA 720 VG (Seppic; Paris, France) at a 3:7 v/v ratio of Ct-F-nMOMP+CpG-2395/Montanide ISA 720 VG. The vaccine was delivered by the intramuscular (i.m.) (500 µl; 250 µl/quadriceps) plus subcutaneous (s.c.) (500 µl; base of the tail) routes. As a negative antigen control, three animals (Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8, and Mmu-5.3) were immunized with the same amount of ovalbumin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) instead of Ct-F-nMOMP by the same delivery routes and using the same adjuvants. The animals were boosted twice at 4-week intervals with the same vaccine preparations.

Sample Collection

Before each immunization and at 2-week intervals post-immunization, e.g. weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10, blood, vaginal washes, conjunctival swabs and rectal swabs were collected from each animal. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and plasma were processed immediately after collection. PBMC were first stored at −80°C for 24 h, and then transferred into liquid nitrogen. Other samples were stored at −20°C until tested.

Western blot

The Western blot was performed as previously described with EB of C. trachomatis serovar F as the antigen [42]. Approximately 30 µg of purified EB were loaded on a 7.5-cm-wide polyacrylamide gel. Following transfer to a nitrocellulose membrane, the nonspecific binding was blocked with BLOTTO (bovine lacto transfer technique optimizer; 5% [wt/vol] nonfat dry milk, 2mM CaCl2, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH8.0]) for 2 hrs at room temperature, and then, serum samples diluted 1:1000, were added to the membrane and incubated overnight at 4°C. The membrane was washed and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-monkey pan IgG and IgM (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) for 1 hr, followed by visualization of the bands by developing with 0.01% hydrogen peroxide and the substrate 4-chloro-1-naphthol (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). A 1:5 dilution of the mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb E-4; generated in our laboratory) against the C. trachomatis serovar E was used as a positive control [43].

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

Chlamydia-specific antibody titers in plasma, vaginal washes and conjunctival and rectal swabs were determined by ELISA as previously described [44]. In brief, a 96-well plate was coated with C. trachomatis, serovar F EB (10 µg/ml of protein) to which 1-fold serial dilutions of samples (plasma diluted 1:100, and saliva, vaginal washes, tears and stools diluted 1:10) were added. Goat anti-monkey IgG and IgA (KPL) was added followed by peroxidase-labeled rabbit anti-goat IgG (KPL). The binding was measured using 2, 2’-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonate) as the substrate. Cross reactivity of plasma from week 10 post immunization was tested against EB of the C. trachomatis D and E genital serovars. The plasma before immunization (week 0) was used as background. The titers are expressed as the inverse of the highest dilution that gave a positive result.

In vitro neutralization assay

The in vitro neutralization assay was performed according to the protocol described by Peterson et al. [43]. Briefly, five-fold serial dilutions of the serum were made in PBS. Duplicate dilutions were incubated for 45 min at 37°C with 104 inclusion forming units (IFU) of C. trachomatis F. The mixtures were then inoculated by centrifugation onto HeLa-229 cell monolayers that were grown in 15 × 45-mm glass shell vials. The monolayers were incubated for 40 hrs and subsequently fixed with methanol. The inclusions were stained using mAb E-4 [43]. A horseradish peroxidase conjugated goat anti-mouse antibody was added and developed with 0.01% H2O2 and 4-chloro-naphthol. The results are expressed as percent inhibition relative to the control sera.

In vitro PBMC response by a lymphocyte proliferative assay (LPA) and cytokine assays

To assess the cell-mediated immune (CMI) response elicited, an in vitro LPA was performed using PBMC isolated at weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8 and 10 post immunization [45]. In brief, frozen PBMC were rapidly thawed, washed with cold culture medium and counted [46]. PBMC (2 × 105/well) from each sample were incubated in triplicate with UV-inactivated C. trachomatis serovar F EB at a 1:1 ratio at 37°C. Concanavalin A (ConA; Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a positive stimulant at a concentration of 5 µg/ml, and tissue culture media served as a negative control. At the end of 96 hrs of incubation, 1.0 µCi of [methyl-3H] thymidine (47 Ci/mmol; Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL) was added to each well and the uptake of the [3H] thymidine was measured after 18 h.

Neat supernatants of stimulated PBMC at 48 h from each animal were analyzed by a liquid array multiplex immunoassay based on the Luminex (Luminex Corp., Austin, TX) fluorescent microsphere platform. A Multiplex kit (Millipore, Billerica, MA) containing cytokine analytes IFN-γ, TNF-α, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-10 and IL-12 was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with overnight sample incubation. A Bio-Rad (Hercules, CA) Bio-Plex 200 system was used with Bio-Plex Manager software 4.0 to analyze standard curves for all eight cytokines, calculated by a five parameter logistic (5-PL) regression model, and best fit regression analysis to calculate cytokine concentrations from experimental samples.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed with the Sigma Stat software package. The two-tailed unpaired Student's t-test was employed to determine the significance of the differences between groups. Differences were considered significant for values of p < 0.05.

RESULTS

SDS-PAGE of native C. trachomatis MOMP from serovar F

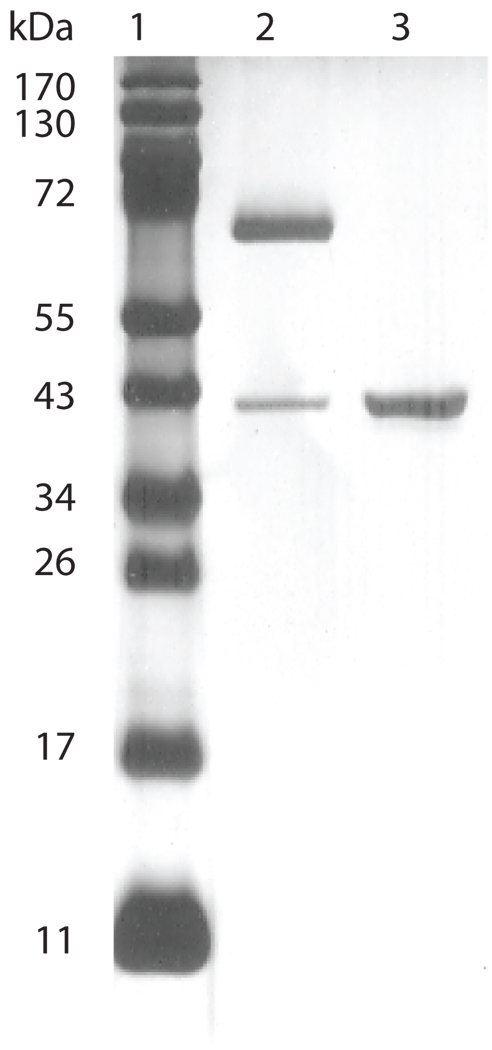

Following extraction with detergents and purification using a hydroxyapatite column, the purity and conformation of the Ct-F-nMOMP, was evaluated by SDS-PAGE. As shown in Fig. 1, when the preparation was not boiled before loading, the MOMP migrated with an apparent MW of 66 kDa. This band corresponds to the native trimer of MOMP. When the sample was boiled before loading the gel, the MOMP migrated with a MW of 40 kDa corresponding to the monomer. No other bands were detected in the silver-stained gel.

Figure 1. SDS-PAGE of the C. trachomatis native MOMP from serovar F.

Lane 1) Molecular weight (MW) standards; Lane 2) The Ct-F-nMOMP preparation was not boiled before loading. The major Ct-F-nMOMP band migrated with an apparent MW of 66 kDa corresponding to the native trimer, and the minor band (MW of 40 KDa) indicative of the MOMP monomer; Lane 3) The sample was boiled before loading into the gel. The MOMP migrated with a MW of 40 kDa corresponding to the monomer.

Characterization of the humoral immune response by ELISA

A total of three sexually mature female rhesus monkeys were vaccinated i.m.+s.c. three times with Ct-F-nMOMP and three control animals were immunized with ovalbumin. CpG-2395 and Montanide ISA 720 VG were used as adjuvants for both groups. Samples, including plasma, vaginal washes, tears, saliva and rectal swabs were collected at regular intervals and tested for the presence of C. trachomatis F serovar-specific antibodies using an ELISA.

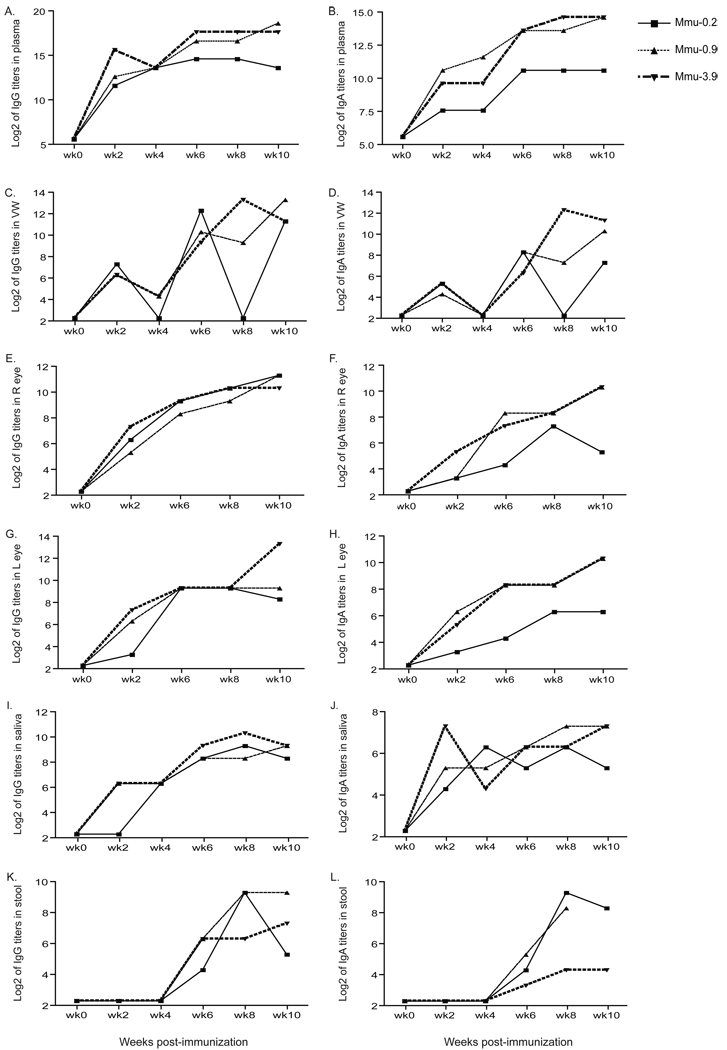

As shown in Figs. 2A and 2B, in the plasma samples from the three monkeys (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9) vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP, the IgG and IgA titers rapidly increased after the first immunization and remained high for the 10 weeks of the experiment. Overall, the antibody titers were similar in the three monkeys. At week-6, monkeys Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9 had IgG titers of 102,400 (log2=16.6) and 204,800 (log2=17.6), respectively while their IgA titer was 12,800 (log2=13.6). The same week monkey Mmu-0.2 had IgG and IgA antibody titers of 25,600 (log2=13.6) and 1,600 (log2=10.6) respectively. In these three monkeys, the IgG and IgA titers in plasma remained high during the 10 weeks of observation.

Figure 2. C. trachomatis, serovar F, ELISA antibody titers expressed as Log2.

A, C, E, G, I, and K are the IgG titers in plasma, vaginal washes (VW), conjunctival swabs from the right (R) and left (L) eyes, saliva and rectal swabs, respectively. B, D, F, H, J, and L are the IgA titers in plasma, vaginal washes, conjunctival swabs from the right (R) and left (L) eyes, saliva and rectal swabs, respectively.

In the vaginal washes the IgG and IgA antibody titers rose over the 10-week of observation (Figs. 2C, 2D). Following the second immunization high antibody titers to serovar F were found in the vaginal washes from the three monkeys (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9) vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP. For example, at week-6 following the first immunization, the IgG titers in monkeys Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9 were 5,120 (log2=12.3), 1,280 (log2=10.3) and 640 (log2=9.3), respectively. The same week the IgA titers in the vaginal washes were 320 (log2=8.3), 320 (log2=8.3) and 80 (log2=6.3) for the same three animals, respectively. In one of the monkeys, Mmu-0.2, the IgG and IgA antibody levels in the vaginal washes were 10 or below the level of detection at weeks 4 and 8 following the initial immunization. This pattern may truly represent fluctuating antibody responses. Anamnestic responses, followed by declines, have been reported by others in similar type of immunization experiments performed with non-human primates [47].

We also detected a continuous increase in Chlamydia-specific IgG and IgA antibodies titers in the tears of the three monkeys immunized with MOMP (Figs. 2E, 2F, 2G, 2H). The IgA and IgG titers were very similar in both eyes in the three monkeys indicating a consistent mucosal immune response to vaccination. Like in the case of the IgA in the vaginal washes, at week 10, monkey Mmu-0.2 had lower titers (40 (log2=5.3) and 80 (log2=6.3) in the right and left eye, respectively, than monkeys Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9 (1,280 (log2=10.3) both monkeys in both eyes).

IgG and IgA C. trahomatis antibody titers were also detected in the oral cavity and gastrointestinal tract samples of the three monkeys Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9, immunized with the Ct-F-nMOMP. Both saliva and stool specimens showed progressive increases in antibody levels for the first 6 to 8 weeks following immunization. At week 8 post-immunization, monkey Mmu-3.9 had overall, the highest IgG antibody titer in saliva (1,280; log2=10.3), while monkeys Mmu-0.2 and Mmu-0.9 had 1–2 fold lower antibody titers (Figs. 2I, 2J). In general, the IgA antibody levels were similar in the three MOMP immunized animals although monkey Mmu-0.2 had slightly lower titers. In the stool samples, no significant levels of Chlamydia-specific antibodies were detected until six weeks following the initial immunization (Figs. 2K, 2L). Both the IgG and the IgA antibody titers in the stools were similar to those found in the saliva.

In the three M. mulatta controls, Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3, immunized with ovalbumin no detectable Chlamydia specific antibodies were detected in plasma, vaginal washes, saliva, tears and stools.

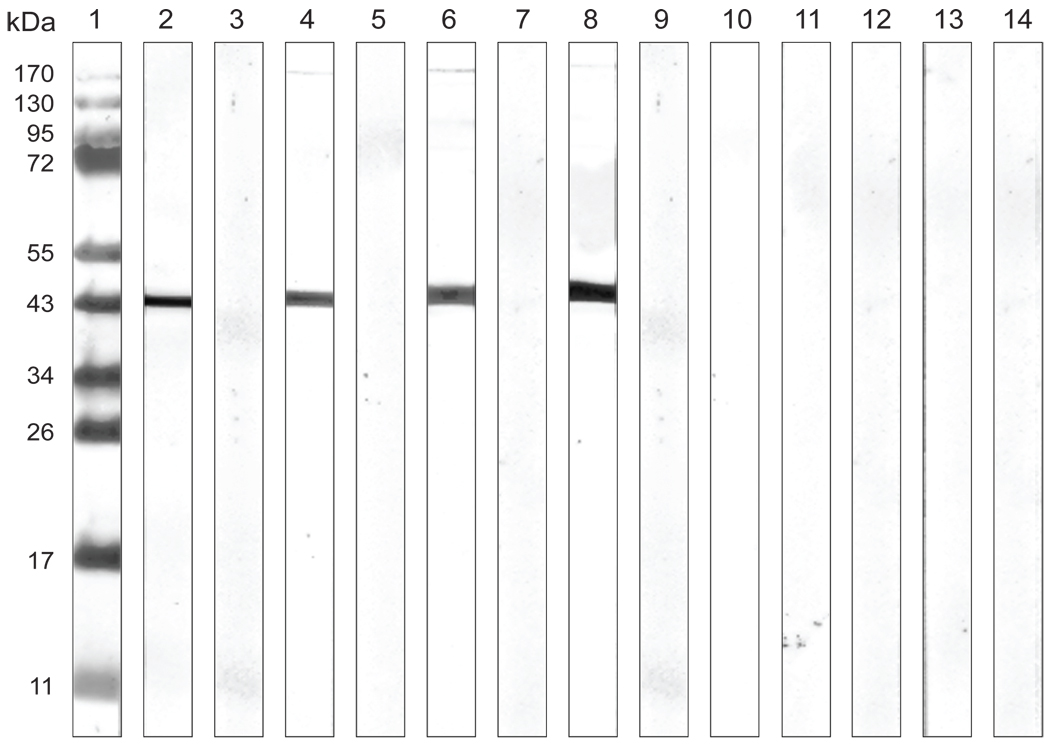

Analysis of the humoral response in plasma by Western blot

C. trachomatis, serovar F EB were separated on an SDS-PAGE and blotted. Results of the plasma samples collected before and after immunization from the six monkeys entered in the study are shown in Fig. 3. The three animals (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9), vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP developed antibodies against a band with a MW of 40 kDa corresponding to the MOMP. As determined by Western blot, none of the three control monkeys, Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3, immunized with ovalbumin and the same adjuvants, developed detectable Chlamydia-specific antibodies.

Figure 3. Western blot analysis of plasma samples.

C. trachomatis EBs of the human serovar F were used as the antigen. Lane 1) Molecular weight standards; Lane 2) control mAb E-4 to the C. trachomatis MOMP; Lanes 3), 5), 7), 9), 11), and 13) are plasma samples from animals Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9, Mmu-3.9, Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3 before immunization, respectively; Lane 4), 6), 8), 10), 12), and 14) are plasma samples from animals Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9, Mmu-3.9, Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3 two weeks after the third immunization, respectively.

Serum neutralizing antibodies

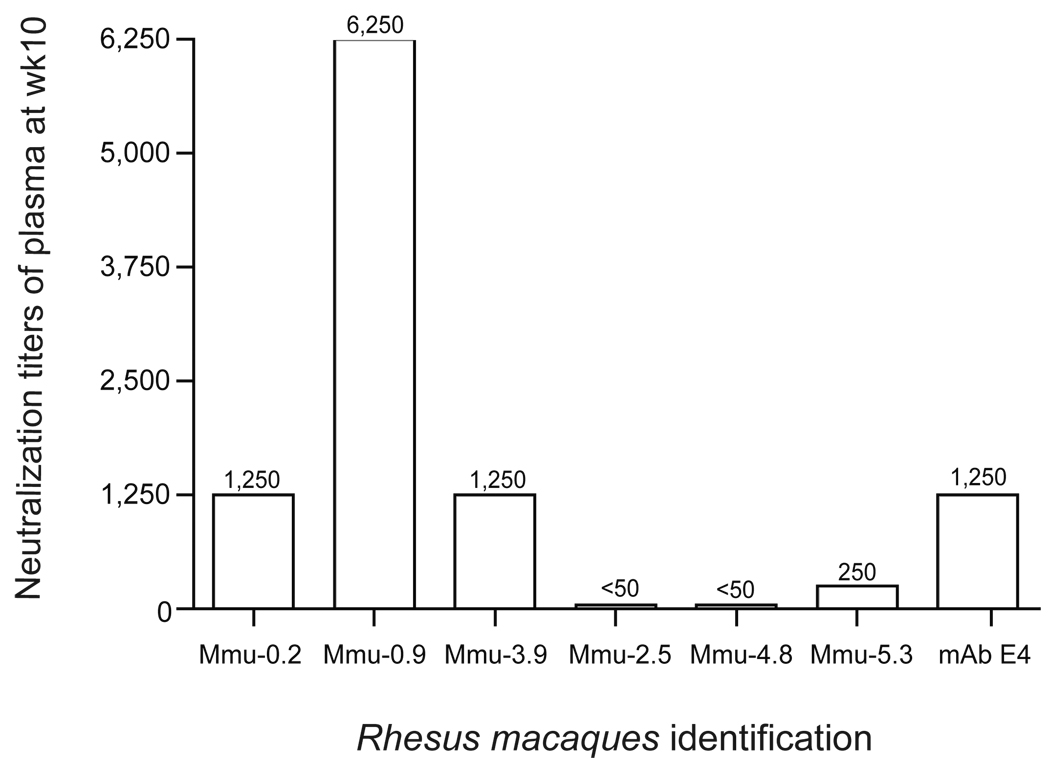

The in vitro neutralizing antibody titers were determined in the plasma samples collected at week 10 following vaccination. Plasma collected from each individual animal before immunization was used as control. As shown in Fig. 4, plasma from M. mulatta Mmu-0.2 and Mmu-3.9, vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP, have neutralizing titers of 1,250 while monkey Mmu-0.9 had a neutralizing titer of 6,250. Of the plasma from the three control monkeys immunized with ovalbumin only one, Mmu-5.3, neutralized EB at a level above the pre-immunization plasma (titer 250). The positive control mAb E-4, had a neutralizing titer of 1,250.

Figure 4. Neutralizing antibody titers in the plasma at 2 weeks following the last immunization.

Plasma collected prior to immunization was used as negative control and mAb E-4 as a positive control.

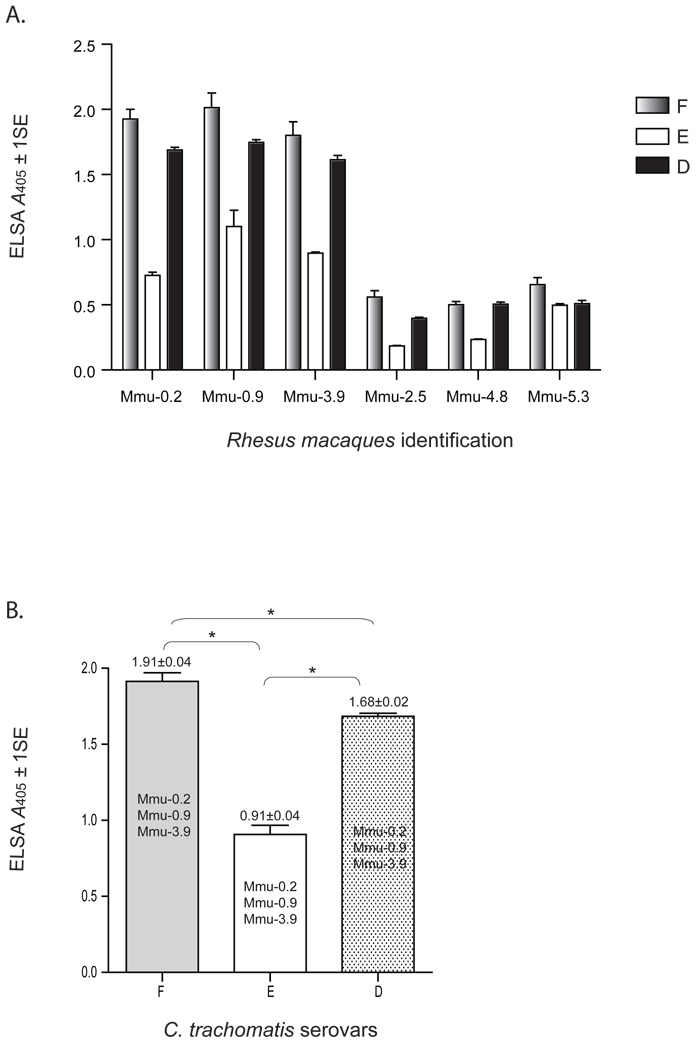

Cross-reactivity of antibodies to other human C. trachomatis serovars

To determine the amount of cross-reactivity induced by Ct-F-nMOMP, we tested plasma collected at 10 weeks following the initial immunization for their ability to react with EB from C. trachomatis serovars D and E. As shown in Figs. 5A, samples from the three M. mulata (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9), vaccinated with the serovar F Ct-F-nMOMP cross-reacted by ELISA with EB from serovars D and E. By pooling the data from the three monkeys, the total antibody titer to serovar D was significantly higher than the antibody titer to serovar E (p < 0.05) (Fig. 5B). The reactivity with serovars D and E was however, significantly lower than to serovar F (p < 0.05). No cross-reactivity to serovars D or E was detected in the three control monkeys (Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3) immunized with ovalbumin.

Figure 5. Cross-reactivity of plasma IgG antibodies with C. trachomatis EB from serovars D and E.

A. Plasma samples collected at 2 weeks following the last immunization were reacted with the C. trachomatis EB from the human serovars F, E and D using an ELISA (OD values= A405 ± 1SE).

B. Comparative statistically analysis of the ELISA antibody titers to C. trachomatis serovars D, E, and F (*, p ≤ 0.05).

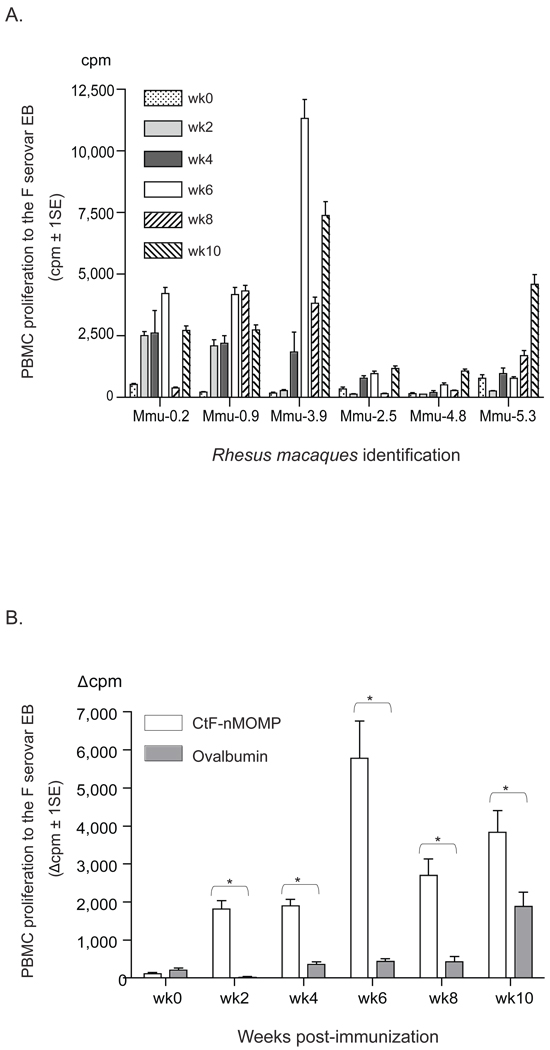

Characterization of the cell-mediated immune response

To assess the CMI response following immunization, PBMC were collected at regular intervals and evaluated by an in vitro LPA and cytokine assay. As shown in Fig. 6A, the strongest Chlamydia-specific lymphoproliferative responses were obtained with the PBMC from M. mulatta Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9. In these animals, high proliferative responses were obtained starting at 2 to 4 weeks following the primary immunization with Ct-F-nMOMP, reached the highest level by week 6 and subsequently declined. To confirm the significance of the Chlamydia-specific response of the PBMC, a statistical analysis was performed by comparing the combined results of the three MOMP vaccinated monkeys (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9), versus those of the three animals immunized with ovalbumin (Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8 and Mmu-5.3). As shown in Fig. 6B, starting at week 2 following immunization and continuing for the 10 weeks of observation, a significant difference in the lymphoproliferative response was found between the monkeys vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP and those immunized with ovalbumin (p < 0.05).

Figure 6. Lymphoproliferative assay (LPA) using PBMC stimulated with C. trachomatis EB from human serovar F.

A. Proliferation of PBMC from individual animals at various time points following immunization (weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) (cpm ± 1SE).

B. Comparison of PBMC proliferation between the Ct-F-nMOMP- (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9, and Mmu-3.9) and the ovalbumin-vaccinated animals (Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8, and Mmu-5.3) at various time points (weeks 0, 2, 4, 6, 8, and 10) post-immunization. (*, p < 0.05).

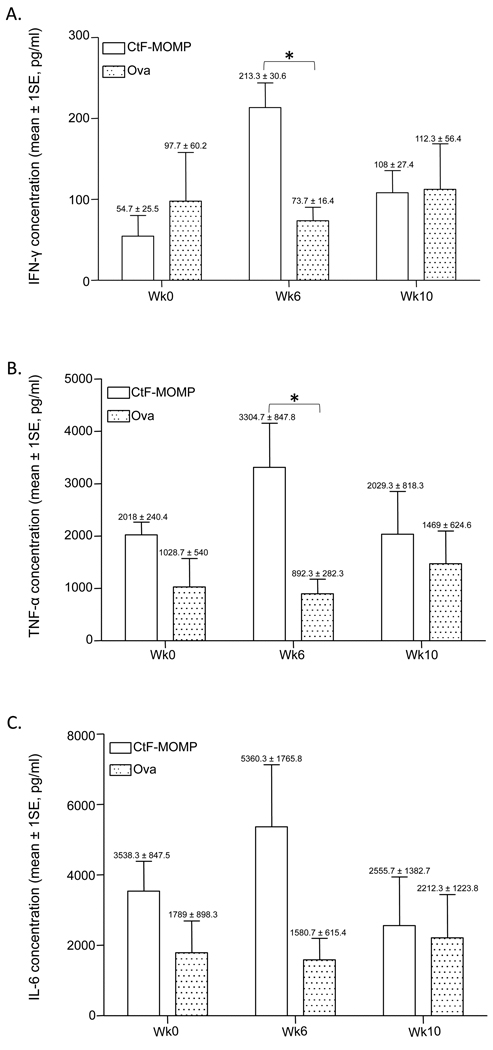

The levels of two out of eight cytokines secreted in the supernatants from the EB-stimulated PBMC from monkeys immunized with Ct-F-nMOMP were significantly different than those from the monkeys immunized with ovalbumin. As shown in Fig. 7, the levels of the Th1 cytokines, IFN-γ and TNF-α, were significantly higher at week 6 in Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9 and Mmu-3.9 when compared with those from the monkeys immunized with ovalbumin (p < 0.05). Unlike for the LPA, no significant differences between the two groups of animals were detected at week 10. The levels of IL-6, a Th2 cytokine, were not significantly different between those animals immunized with Ct-F-nMOMP and the monkeys vaccinated with ovalbumin. Similarly, no differences in the levels of the other measured cytokines were found between the two groups.

Figure 7. Levels of cytokines in supernatants from PBMC stimulated in vitro with C. trachomatis EB from human serovar F.

Comparison of the levels of: A) IFN-γ; B) TNF-α; and C) IL-6, between the Ct-F-nMOMP- (Mmu-0.2, Mmu-0.9, and Mmu-3.9) and the ovalbumin-vaccinated animals (Mmu-2.5, Mmu-4.8, and Mmu-5.3) at various time points (weeks 0, 6, and 10) post-immunization; (*, p < 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The current study was designed to test the ability of a vaccine formulated with the Ct-F-nMOMP and Th1+Th2 adjuvants, to induce robust systemic and mucosal immune responses in a nonhuman primate model. The results indicate that this vaccine formulation, delivered by systemic routes, can elicit strong humoral and cell mediated immune responses in sexually mature female rhesus macaques. Specifically, as determined by the presence of IgG and IgA Chlamydia-specific antibodies, the vaccination protocol elicited humoral responses in the conjunctiva, oral cavity, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts. In addition, as measured by a lymphoproliferative assay, the vaccine elicited a systemic cell mediated immune response. To our knowledge, this is the first time that a subunit vaccine, formulated with a native antigen from a genital human C. trachomatis serovar, was found to elicit robust systemic and mucosal immune responses in a nonhuman primate model.

In the 1970's the recognition of a major role for C. trachomatis in sexually transmitted infections ignited an interest in the development of a vaccine. Most investigators elected to characterize the immunopathogenesis of the infection and to test vaccines in female mice using the C. trachomatis mouse pneumonitis (MoPn; also called C. muridarum) isolate [28, 35]. By infecting female mice with live MoPn it was determined that protection against a genital challenge required cellular and humoral immune responses [28, 35]. Specifically, at least in mice, CD4+ T cells, in particular Th1-type, and antibodies were found to be critical for the resolution of a genital chlamydial infection while CD8+ T cells played a minor role [28, 35, 48–50]. For example, transfer of purified CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from mice with a primary MoPn genital infection to naïve mice showed that only CD4+ cells conferred protection against a vaginal challenge [35, 48, 49]. In addition, passive immunization of mice with an IgA mAb to the MOMP reduced infection rates, levels of vaginal shedding and dissemination [51]. In humans, antibodies have also been found to be important for protection. For example, Brunham et al. [52] found an inverse correlation between the amount of IgA in cervical secretions and the amount of chlamydial IFU recovered from the cervix of infected women. Thus, combining cellular and humoral responses may be desirable for maximum immune-induced protection against Chlamydia. Here, to optimize the protective immune response, we elected to use CpG-2395 and Montanide ISA 720 VG two adjuvants that bias the immune response toward Th1 and antibody production, respectively [53–55]. These two adjuvants have already been shown to be safe and effective in human clinical trials against several pathogens and therefore, could potentially be used in the formulation of a Chlamydia vaccine [56, 57].

The amount of information currently available on the pathogenesis and immune mechanisms of protection against a chlamydial genital infection in nonhuman primates is very limited. For example, Wolner-Hanssen et al. [58] inoculated the cervix of female pig-tailed macaques (M. nemestrina) with C. trachomatis, serovar D and observed that repeated inoculation either failed to produce infection, or resulted in a shorter duration of infection with lower number of inclusions. The authors concluded that, vaccination with live organisms, elicits a protective immune response. Wolner-Hanssen et al. [58] only measured serum IgG antibodies and found that the titers and the maximum inclusion counts did not correlate and that there was no relationship between antibody titers at the time of reinoculation and the reinfection rate. The authors postulated that local antibodies, specifically IgA, could account for the protection observed in their model. Van Voorhis et al. [59] repeatedly infected with C. trachomatis, serovar E subcutaneous pockets of autologous salpingeal tissue implanted in M. nemestrina and observed a mononuclear infiltrate, mainly composed of CD8+ T-cells. Increases in IFN-γ, IL-2, IL-6 and IL-10, but not IL-4, mRNA were detected in the salpingeal pocket tissues. Following the third infection fibrosis developed in the subcutaneous salpingeal pockets. The authors concluded that chlamydial infection of the upper genital tract leads to CD8 T-cell predominance in a Th1 cytokine environment, and that these inflammatory changes lead to fibrosis and infertility.

The route of administration of a vaccine influences the distribution and nature of immune responses [60–62]. The portal of entry of Chlamydia can involve several organs including the conjunctiva, oral cavity and the respiratory, gastrointestinal and genitourinary tracts [5, 63]. Therefore, it is critical, to identify routes of immunization that can elicit strong immune responses at various mucosal sites. This is particularly important because, due to the compartmentalization of the mucosal immune system, stimulation of the various mucosal inductive sites results in an uneven distribution of immune responses at the various effector sites [60, 64, 65]. Overall, the most effective way to induce an immune response at a specific effector site is to locally administer the immunization, or perhaps, stimulate sites with related lymph drainage. Due to the multiple portals of entry of Chlamydia, using a mucosal site for vaccination may only result in a localized protection at the mucosal site used for immunization. For this reason here, systemic routes were used for immunization with the expectation of eliciting systemic and mucosal responses at the different portals of entry of Chlamydia. As determined by the presence of IgG and IgA in plasma, tears, saliva, stools and vaginal washes, we were able to elicit broad and robust mucosal immune responses at the main Chlamydia portals of entry.

These results have certain similarities and also some differences from those obtained by Kari et al. [41] following immunization of cynomologous macaques (Macaca fascicularis) with the ocular C. trachomatis serovar A nMOMP also formulated with CpG-2395 plus Montanide ISA 720. Like Kari et al. [41] we detected high IgG and IgA Chlamydia-specific antibody titers in plasma samples from the three Ct-F-nMOMP immunized monkeys. However, the in vitro neutralizing activity that we observed was significantly lower than the one detected by Kari et al. [41]. These authors found very high neutralizing titers in the plasma from the three immunized monkeys (20,000–100,000) while the titers that we detected were significantly lower (1,250–6,250). This difference may be biologically significant, or it may be a result of the differences in the methods used to determine neutralizing antibodies. For example, Kari et al. [41] used HAK cells for their in vitro neutralization assay, without guinea pig complement, while we utilized HeLa-229 cells in the presence of guinea pig complement. Alternatively, the epitopes present in the MOMP from the different Chlamydia isolates may be more or less immunodominant. Also, Kari et al. [41] performed their studies in M. fascicularis while we immunized M. mulatta. Therefore, it is possible that, monkeys with various genetic backgrounds, respond differently to similar vaccination protocols [66].

Here, we have also shown that monkeys vaccinated with Ct-F-nMOMP, formulated with CpG-2395 plus Montanide ISA 720 VG, mounted a strong Chlamydia-specific mediated cellular immune response. PBMC from the Ct-F-nMOMP vaccinated monkeys, in comparison with PBMC from ovalbumin-immunized animals, showed a significant proliferative response when stimulated with C. trachomatis F EB. These results are consistent with the findings reported by Kari et al. in cynomologus monkeys immunized with nMOMP from C. trachomatis serovar A [41]. We also detected a parallel significant increase in the levels of IFN-γ and TNF-α in the supernatants of EB-stimulated PBMC. Similarly, Kari et al. detected positive levels of IFN-γ in the supernatants of PBMC stimulated with C. trachomatis serovar A EB [41].

In conclusion, to our knowledge, this is the first time that, in addition to a systemic immune response, Chlamydia-specific antibodies have been measured in the saliva, stools and vaginal washes of nonhuman primates following immunization with a subunit vaccine. Sexual transmission of Chlamydia can occur in both the heterosexual and homosexual population by various routes including the conjunctiva, mouth, rectum and genitourinary tract [5, 63]. In this respect, our results are very encouraging since we were able to detect antibodies at all these chlamydial portals of entry.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by a Pilot Grant from the University of California, Davis, California National Primate Research Center (NCRR, RR000169).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chlamydia screening among sexually active young female enrollees of health plans--United States, 2000–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009 Apr 17;58(14):362–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Summary of Notifiable Diseases, United States, 1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999 Dec 31;47(53) ii-92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Datta SD, Sternberg M, Johnson RE, Berman S, Papp JR, McQuillan G, et al. Gonorrhea and chlamydia in the United States among persons 14 to 39 years of age, 1999 to 2002. Ann Intern Med. 2007 Jul 17;147(2):89–96. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-2-200707170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WC, Ford CA, Morris M, Handcock MS, Schmitz JL, Hobbs MM, et al. Prevalence of chlamydial and gonococcal infections among young adults in the United States. Jama. 2004 May 12;291(18):2229–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.18.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schachter J, Dawson C. Human chlamydial infections. Littleton: PSG Publishing Co; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schachter J. Infection and disease epidemiology. In: Stephens R, editor. Chlamydia: intracellular biology, pathogenesis and immunity. Washington: ASM; 1999. pp. 139–170. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ness RB, Smith KJ, Chang CC, Schisterman EF, Bass DC. Prediction of pelvic inflammatory disease among young, single, sexually active women. Sex Transm Dis. 2006 Mar;33(3):137–142. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000187205.67390.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Westrom L, Joesoef R, Reynolds G, Hagdu A, Thompson SE. Pelvic inflammatory disease and fertility. A cohort study of 1,844 women with laparoscopically verified disease and 657 control women with normal laparoscopic results. Sex Transm Dis. 1992 Jul–Aug;19(4):185–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brunham RC, Binns B, McDowell J, Paraskevas M. Chlamydia trachomatis infection in women with ectopic pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1986 May;67(5):722–726. doi: 10.1097/00006250-198605000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beem MO, Saxon EM. Respiratory-tract colonization and a distinctive pneumonia syndrome in infants infected with Chlamydia trachomatis. N Engl J Med. 1977 Feb 10;296(6):306–310. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197702102960604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Geisler WM, Suchland RJ, Whittington WL, Stamm WE. The relationship of serovar to clinical manifestations of urogenital Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2003 Feb;30(2):160–165. doi: 10.1097/00007435-200302000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berger RE, Alexander ER, Harnisch JP, Paulsen CA, Monda GD, Ansell J, et al. Etiology, manifestations and therapy of acute epididymitis: prospective study of 50 cases. J Urol. 1979 Jun;121(6):750–754. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56978-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beagley KW, Wu ZL, Pomering M, Jones RC. Immune responses in the epididymis: implications for immunocontraception. J Reprod Fertil Suppl. 1998;53:235–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gdoura R, Kchaou W, Znazen A, Chakroun N, Fourati M, Ammar-Keskes L, et al. Screening for bacterial pathogens in semen samples from infertile men with and without leukocytospermia. Andrologia. 2008 Aug;40(4):209–218. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2008.00845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berger RE, Alexander ER, Monda GD, Ansell J, McCormick G, Holmes KK. Chlamydia trachomatis as a cause of acute "idiopathic" epididymitis. N Engl J Med. 1978 Feb 9;298(6):301–304. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197802092980603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Annan NT, Sullivan AK, Nori A, Naydenova P, Alexander S, McKenna A, et al. Rectal chlamydia--a reservoir of undiagnosed infection in men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Infect. 2009 Jun;85(3):176–179. doi: 10.1136/sti.2008.031773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schachter J, Dawson CR. Elimination of blinding trachoma. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2002 Oct;15(5):491–495. doi: 10.1097/00001432-200210000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paba P, Bonifacio D, Di Bonito L, Ombres D, Favalli C, Syrjanen K, et al. Co-expression of HSV2 and Chlamydia trachomatis in HPV-positive cervical cancer and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia lesions is associated with aberrations in key intracellular pathways. Intervirology. 2008;51(4):230–234. doi: 10.1159/000156481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Plummer FA, Simonsen JN, Cameron DW, Ndinya-Achola JO, Kreiss JK, Gakinya MN, et al. Cofactors in male-female sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 1991 Feb;163(2):233–239. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.2.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ness RB, Soper DE, Holley RL, Peipert J, Randall H, Sweet RL, et al. Effectiveness of inpatient and outpatient treatment strategies for women with pelvic inflammatory disease: results from the Pelvic Inflammatory Disease Evaluation and Clinical Health (PEACH) Randomized Trial. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002 May;186(5):929–937. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekart ML, Brunham RC. Epidemiology of chlamydial infection: are we losing ground? Sex Transm Infect. 2008 Apr;84(2):87–91. doi: 10.1136/sti.2007.027938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brunham RC, Pourbohloul B, Mak S, White R, Rekart ML. The unexpected impact of a Chlamydia trachomatis infection control program on susceptibility to reinfection. J Infect Dis. 2005 Nov 15;192(10):1836–1844. doi: 10.1086/497341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gotz H, Lindback J, Ripa T, Arneborn M, Ramsted K, Ekdahl K. Is the increase in notifications of Chlamydia trachomatis infections in Sweden the result of changes in prevalence, sampling frequency or diagnostic methods? Scand J Infect Dis. 2002;34(1):28–34. doi: 10.1080/00365540110077001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SP, Grayston JT, Alexander ER. Trachoma vaccine studies in monkeys. Am J Ophthalmol. 1967 May;63(5) Suppl:1615–1630. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(67)94155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Taylor HR. Strategies for the control of trachoma. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol. 1987 May;15(2):139–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-9071.1987.tb00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rockey DD, Wang J, Lei L, Zhong G. Chlamydia vaccine candidates and tools for chlamydial antigen discovery. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009 Oct;8(10):1365–1377. doi: 10.1586/erv.09.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.de la Maza LM, Peterson EM. Vaccines for Chlamydia trachomatis infections. Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002 Jul;3(7):980–986. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brunham RC, Rey-Ladino J. Immunology of Chlamydia infection: implications for a Chlamydia trachomatis vaccine. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005 Feb;5(2):149–161. doi: 10.1038/nri1551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Stephens RS, Sanchez-Pescador R, Wagar EA, Inouye C, Urdea MS. Diversity of Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein genes. J Bacteriol. 1987 Sep;169(9):3879–3885. doi: 10.1128/jb.169.9.3879-3885.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang SP, Grayston JT. Classification of Trachoma Virus Strains by Protection of Mice from Toxic Death. J Immunol. 1963 Jun;90:849–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Caldwell HD, Kromhout J, Schachter J. Purification and partial characterization of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect Immun. 1981 Mar;31(3):1161–1176. doi: 10.1128/iai.31.3.1161-1176.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Caldwell HD, Schachter J. Antigenic analysis of the major outer membrane protein of Chlamydia spp. Infect Immun. 1982 Mar;35(3):1024–1031. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.3.1024-1031.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dong-Ji Z, Yang X, Shen C, Lu H, Murdin A, Brunham RC. Priming with Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein (MOMP) DNA followed by MOMP ISCOM boosting enhances protection and is associated with increased immunoglobulin A and Th1 cellular immune responses. Infect Immun. 2000 Jun;68(6):3074–3078. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3074-3078.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Igietseme JU, Black CM, Caldwell HD. Chlamydia vaccines: strategies and status. BioDrugs. 2002;16(1):19–35. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200216010-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morrison RP, Caldwell HD. Immunity to murine chlamydial genital infection. Infect Immun. 2002 Jun;70(6):2741–2751. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.6.2741-2751.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Su H, Caldwell HD. Immunogenicity of a chimeric peptide corresponding to T helper and B cell epitopes of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. J Exp Med. 1992 Jan 1;175(1):227–235. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taylor HR, Whittum-Hudson J, Schachter J, Caldwell HD, Prendergast RA. Oral immunization with chlamydial major outer membrane protein (MOMP) Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1988 Dec;29(12):1847–1853. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pal S, Barnhart KM, Wei Q, Abai AM, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Vaccination of mice with DNA plasmids coding for the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein elicits an immune response but fails to protect against a genital challenge. Vaccine. 1999 Feb 5;17(5):459–465. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(98)00219-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun G, Pal S, Weiland J, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Protection against an intranasal challenge by vaccines formulated with native and recombinant preparations of the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein. Vaccine. 2009 Aug 6;27(36):5020–5025. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pal S, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Vaccination with the Chlamydia trachomatis major outer membrane protein can elicit an immune response as protective as that resulting from inoculation with live bacteria. Infect Immun. 2005 Dec;73(12):8153–8160. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.12.8153-8160.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kari L, Whitmire WM, Crane DD, Reveneau N, Carlson JH, Goheen MM, et al. Chlamydia trachomatis native major outer membrane protein induces partial protection in nonhuman primates: implication for a trachoma transmission-blocking vaccine. J Immunol. 2009 Jun 15;182(12):8063–8070. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0804375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schagger H, von Jagow G. Tricine-sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for the separation of proteins in the range from 1 to 100 kDa. Anal Biochem. 1987 Nov 1;166(2):368–379. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90587-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peterson EM, Zhong GM, Carlson E, de la Maza LM. Protective role of magnesium in the neutralization by antibodies of Chlamydia trachomatis infectivity. Infect Immun. 1988 Apr;56(4):885–891. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.4.885-891.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cheng C, Bettahi I, Cruz-Fisher MI, Pal S, Jain P, Jia Z, et al. Induction of protective immunity by vaccination against Chlamydia trachomatis using the major outer membrane protein adjuvanted with CpG oligodeoxynucleotide coupled to the nontoxic B subunit of cholera toxin. Vaccine. 2009 Oct 19;27(44):6239–6246. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen CR, Koochesfahani KM, Meier AS, Shen C, Karunakaran K, Ondondo B, et al. Immunoepidemiologic profile of Chlamydia trachomatis infection: importance of heat-shock protein 60 and interferon- gamma. J Infect Dis. 2005 Aug 15;192(4):591–599. doi: 10.1086/432070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Makino M, Baba M. A cryopreservation method of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells for efficient production of dendritic cells. Scand J Immunol. 1997 Jun;45(6):618–622. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3083.1997.d01-441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Abel K, Strelow L, Yue Y, Eberhardt MK, Schmidt KA, Barry PA. A heterologous DNA prime/protein boost immunization strategy for rhesus cytomegalovirus. Vaccine. 2008 Nov 5;26(47):6013–6025. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.07.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Igietseme JU, Ramsey KH, Magee DM, Williams DM, Kincy TJ, Rank RG. Resolution of murine chlamydial genital infection by the adoptive transfer of a biovar-specific, Th1 lymphocyte clone. Reg Immunol. 1993 Nov–Dec;5(6):317–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Igietseme JU, Magee DM, Williams DM, Rank RG. Role for CD8+ T cells in antichlamydial immunity defined by Chlamydia-specific T-lymphocyte clones. Infect Immun. 1994 Nov;62(11):5195–5197. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5195-5197.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Perry LL, Feilzer K, Caldwell HD. Immunity to Chlamydia trachomatis is mediated by T helper 1 cells through IFN-gamma-dependent and -independent pathways. J Immunol. 1997 Apr 1;158(7):3344–3352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pal S, Theodor I, Peterson EM, de la Maza LM. Monoclonal immunoglobulin A antibody to the major outer membrane protein of the Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis biovar protects mice against a chlamydial genital challenge. Vaccine. 1997 Apr;15(5):575–582. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brunham RC, Kuo CC, Cles L, Holmes KK. Correlation of host immune response with quantitative recovery of Chlamydia trachomatis from the human endocervix. Infect Immun. 1983 Mar;39(3):1491–1494. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.3.1491-1494.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vollmer J, Weeratna R, Payette P, Jurk M, Schetter C, Laucht M, et al. Characterization of three CpG oligodeoxynucleotide classes with distinct immunostimulatory activities. Eur J Immunol. 2004 Jan;34(1):251–262. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Klinman DM, Klaschik S, Sato T, Tross D. CpG oligonucleotides as adjuvants for vaccines targeting infectious diseases. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2009 Mar 28;61(3):248–255. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2008.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hui GS, Hashimoto CN. Adjuvant formulations possess differing efficacy in the potentiation of antibody and cell mediated responses to a human malaria vaccine under selective immune genes knockout environment. Int Immunopharmacol. 2008 Jul;8(7):1012–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Genton B, D'Acremont V, Lurati-Ruiz F, Verhage D, Audran R, Hermsen C, et al. Randomized double-blind controlled Phase I/IIa trial to assess the efficacy of malaria vaccine PfCS102 to protect against challenge with P. falciparum. Vaccine. 2010 Sep 14;28(40):6573–6580. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sagara I, Ellis RD, Dicko A, Niambele MB, Kamate B, Guindo O, et al. A randomized and controlled Phase 1 study of the safety and immunogenicity of the AMA1-C1/Alhydrogel + CPG 7909 vaccine for Plasmodium falciparum malaria in semi-immune Malian adults. Vaccine. 2009 Dec 9;27(52):7292–7298. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.10.087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wolner-Hanssen P, Patton DL, Holmes KK. Protective immunity in pig-tailed macaques after cervical infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Sex Transm Dis. 1991 Jan–Mar;18(1):21–25. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199101000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Van Voorhis WC, Barrett LK, Sweeney YT, Kuo CC, Patton DL. Repeated Chlamydia trachomatis infection of Macaca nemestrina fallopian tubes produces a Th1-like cytokine response associated with fibrosis and scarring. Infect Immun. 1997 Jun;65(6):2175–2182. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2175-2182.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Neutra MR, Kozlowski PA. Mucosal vaccines: the promise and the challenge. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006 Feb;6(2):148–158. doi: 10.1038/nri1777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kozlowski PA, Williams SB, Lynch RM, Flanigan TP, Patterson RR, Cu-Uvin S, et al. Differential induction of mucosal and systemic antibody responses in women after nasal, rectal, or vaginal immunization: influence of the menstrual cycle. J Immunol. 2002 Jul 1;169(1):566–574. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.1.566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Barnett SW, Srivastava IK, Kan E, Zhou F, Goodsell A, Cristillo AD, et al. Protection of macaques against vaginal SHIV challenge by systemic or mucosal and systemic vaccinations with HIV-envelope. Aids. 2008 Jan 30;22(3):339–348. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3282f3ca57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Stamm W. Chlamydia trachomatis infections of the adult. In: Holmes PS KK, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit JW, Corey L, Cohen MS, Watts DH, editors. Sexually transmitted diseases. New York: McGrawHill Book Co; 2008. pp. 575–593. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mestecky J, Russell MW. Induction of mucosal immune responses in the human genital tract. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2000 Apr;27(4):351–355. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2000.tb01449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mestecky J, Moldoveanu Z, Russell MW. Immunologic uniqueness of the genital tract: challenge for vaccine development. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2005 May;53(5):208–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2005.00267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lichtenwalner AB, Patton DL, Cosgrove Sweeney YT, Gaur LK, Stamm WE. Evidence of genetic susceptibility to Chlamydia trachomatis-induced pelvic inflammatory disease in the pig-tailed macaque. Infect Immun. 1997 Jun;65(6):2250–2253. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.6.2250-2253.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]