Abstract

Little is known about how much Medicare families can afford to pay for health care and whether the Medicare prescription drug program (Part D) will provide financial protection. In this paper we assess total out-of-pocket health care spending of Medicare families in the context of their available resources in the year prior to Part D. We find that high health spending burdens are common. Medicare families with incomes up to 250% of the Federal Poverty Level are at high risk for incurring burdensome health care costs, and this includes many who would not be eligible for Part D Low-income subsidy assistance.

A 65-year old couple needs about $215,000 to cover their estimated future out-of-pocket health care costs, yet the average retirement account for such a couple contains only $90,000.1 The magnitude of this difference illustrates the potential for health care costs to overwhelm personal household resources. Currently, one in four Americans report problems paying for health care, and one in three delay getting health care due to costs.2 Financial pressure from out-of-pocket health care costs may occur even in families with health insurance; over 50% of all bankruptcies involve substantial health care debt, even though 76% of bankruptcy filers had health insurance at the onset of illness.3

The single largest driver of out-of-pocket health care costs is medications, excluding the costs for health insurance premiums, and the burden of medication costs is often cited as an obstacle to appropriate care. In 2004, 20 cents of every dollar paid out-of-pocket for health care in the U.S. went to medications, compared to 17 cents for physician care, and 15 cents for dental care.4 The burden of out-of-pocket costs for medications is especially felt by older adults who take, on average, 4 to 5 different drugs each week.5 Older adults also frequently cite problems affording medications; in 2005, 11% of Medicare enrollees said they spent less on basic needs to afford their medications, while 14% said they took less medication than prescribed or did fill prescriptions because of costs.6

The most significant health care policy implemented in the past few decades to reduce the out-of-pocket health care costs of older adults is the Medicare outpatient prescription drug benefit (“Medicare Part D”). Medicare Part D provides assistance with out-of-pocket health care cost in several ways. First, it covers a portion of direct medication costs. In 2008, the standard Medicare Part D benefit paid for 75% of total drug costs occurring after a $275 deductible and before an initial coverage limit of $2,510, and then 95% of total drug costs above $5,726 (catastrophic coverage). Second, the premiums for Medicare Part D are heavily subsidized: about 75% of Medicare Part D’s costs are paid for by the Medicare program so that individuals paid, on average, only $28 per month for drug insurance in 2009.7 Lastly, Medicare Part D offers a generous low-income subsidy (LIS) to enrollees with limited assets and incomes under 150% of the federal poverty level. The LIS benefit provides full or partial waivers of many out-of-pocket cost-sharing requirements including premiums, deductibles, copayments, and the 100% coverage gap (“doughnut hole”). The average value of the Medicare Part D coverage, premium subsidy, and LIS benefit was $3,900 in 2009.8

To date, there have been no published studies evaluating the extent to which Medicare Part D has alleviated the financial burden of out-of-pocket health care costs. One reason for this is a fragmented understanding of these costs in the context of available household resources. The true burden of out-of-pocket health care costs is the extent to which they compete for a share of household resources among other basic necessities such as food, housing, clothing, and transportation. The theory of welfare economics holds that individuals are the best judges of how to allocate resources to maximize their welfare but it also raises questions about what is reasonable for individuals to sacrifice. In the case of health care, it is widely accepted that individuals should be protected from catastrophic health care costs and not be expected to endure impoverishment to cope with health costs.9 However, there is no practical definition of what constitutes this level of unacceptable costs or consensus on how much Medicare families can afford to pay for health care.

The purpose of this study is to characterize out-of-pocket health care spending of Medicare enrollees in the year before Part D and the relationship of this spending to other household spending. Our aim is to provide baseline information that can be used to assess the effects of Medicare Part D on the financial burden of medication costs. In addition, we will assess the adequacy of the LIS benefit by examining whether the eligibility rules identify families at-risk for burdensome health care costs. This information will be important as the program evolves, especially since out-of-pocket costs for Medicare Part D enrollees are indexed to the overall growth in drug costs.

Methods

Data

We used the 2005–2006 Health and Retirement Study (HRS), a longitudinal survey of adults aged 51 and older.10 The HRS gathers information on the economics, demographics, and health care of aging, based on a sample of about 10,000 households headed by older adults. The HRS interviews are conducted in the home and follow-up surveys occur every other year. Response rates are high (~85%). By design, the survey oversamples Blacks, Hispanics and residents of Florida. The survey also provides sampling weights scaled to the Current Population Survey for yielding estimates generalizable to the U.S. population of older adults. In the off-year of the survey, a subsample of 5,000 HRS respondents is sent a mail survey, known as the Consumption and Activities Mail Survey (CAMS). The CAMS asks respondents to estimate household spending for major budget items, such as mortgage, food, and health care. Response rates for the CAMS are ~77%. For this study we merged the 2006 HRS core files with the 2005 CAMS files for a dataset on approximately 3,800 households. Household expenditures, including for medications, come from 2005, which allow us to establish baseline levels before the influence of Part D and the LIS benefit.

We restricted our study sample to households where the main HRS respondent or the spouse/partner reported Medicare coverage. We identified 3,242 respondents with Medicare enrollment, and excluded 761 individuals due to duplicate households and 379 due to death, institutionalization, or attrition for a total sample of 2,102 households, which represent 7.5 million Medicare families when the sampling weights are applied.

Measures

Burdensome out-of-pocket spending

There is no consensus on how much households should be able to pay for health care; however, a definition that has been used recently is 40% of a household’s total consumption after subtracting expenses for basic living needs.11 Total household consumption has been shown to be a more accurate reflection of family wealth than income.12 We applied the 40% threshold to our measure of a household’s flexible expenditures, as described in detail in a prior study.13

Briefly, we categorized household consumption into three broad types: housing, transportation, food, and personal care; health care; and other “nonessential” spending. Housing, transportation, food, and personal care comprised items such as food, gas, and heat, while nonessential spending comprised items such as vacations and event tickets.

We created two measures of out-of-pocket health care costs. Our primary measure included: prescription and over-the-counter drugs, hospital care, health professional services, lab tests, eye care, dental services, and health insurance premiums. The second measure of health care costs excludes the costs of premiums, since this is, arguably, the most predictable component of health care costs. A comparison of the two measures is provided in the technical appendix. Flexible expenditures are the sum of the household’s total consumption minus spending for housing, transportation, food, and personal care. In addition, sensitivity analyses were conducted varying the burdensome thresholds from 30% to 60% (see technical appendix).

Household wealth

In addition to total household consumption, we also measured household wealth, defined as income and assets. Household income included both earned and unearned income. Assets included nonhousing equity such as stock and mutual funds.

Medicare Part D Low Income Subsidy (LIS)

We applied the Part D assistance eligibility rules for the low-income subsidy program to our population.14 In summary, eligibility for the LIS is granted if enrollees have Medicaid, or incomes less than 150% of the federal poverty level (FPL) and nonhousing assets less than $11,500 if single or $23,000 if a married couple. To determine LIS eligibility, we examined 93 categories of income and other resources captured in the HRS and applied the program’s rules. For instance, we excluded resources related to the primary home, car, and savings for funeral or burial expenses, as per the program’s rules. We then categorized the population into 6 groups: 1) Eligible for Part D LIS assistance through Medicaid status; 2) Eligible through low income and low assets; 3) Ineligible due to asset thresholds; 4) Ineligible due to income thresholds and income <=200% FPL; 5) Ineligible due to income thresholds and income between 200% and 250% FPL; and 6) Ineligible due to income thresholds and income >250% FPL.

Analysis

We weighted all estimates using the HRS household sampling weights and adjusted the standard errors for the survey’s clustered sample design. We used the imputed values in the HRS dataset for missing asset and income data and the RAND/UCLA income and assets variables.15 We inflated the expenditure values to 2006 values using the consumer price index.16 We reported medians and interquartile ranges for all expenditures and used logistic regression to estimate the probability of incurring burdensome health expenditures by Part D LIS status.

Results

Our study sample looked similar to the national Medicare population; 64% were female; 90% were white/Caucasian; average age was 75 (SE+/−0.31); 35% reported fair or poor health, and 90% had drug coverage (data not shown). Table 1 shows that the median family income was $26,000 in 2006 (interquartile range (IQR): 15,000–45,432) and median nonhousing assets were $55,000 (IQR: 5,000–271,200). Median family expenditures were $22,854 (IQR 14,682–33,513), of which $15,297 (IQR: 10,431–21,634) were allocated to housing, transportation, food, and personal care and $2,781 (IQR: 1,021–5,150) to health care. The remainder of $2,909 (IQR: 1050–6,858) was allocated to nonessential items such as entertainment and gifts. Older families spent 43.9% (IQR: 26.5–66.9) of their flexible expenditures on health care.

Exhibit 1.

Medicare Family Income, Non-Housing Assets, and Household Consumption Patterns, 2006

| Interquartile range | Median | |

|---|---|---|

| Household income | 15000–45432 | $26,000 |

| Non-housing assets | 5000–271200 | $55,000 |

| Total household consumption | 14682–33513 | $22,854 |

| Health care | 1021–5150 | $2,781 |

| Health insurance premiums | 154–2765 | $1236 |

| Medications | 185–1236 | $556 |

| Housing, food, transportation & personal care | 10431–21634 | $15,297 |

| Food | 1609–4944 | $2,683 |

| Heat | 0–1168 | $618 |

| Gasoline | 370–1609 | $988 |

| Nonessential spending | 1050–6859 | $2,909 |

| Health care as % of flexible expenditures* | 26.5–66.9 | 43.9% |

Total household consumption – expenses for housing, food, transportation & personal care

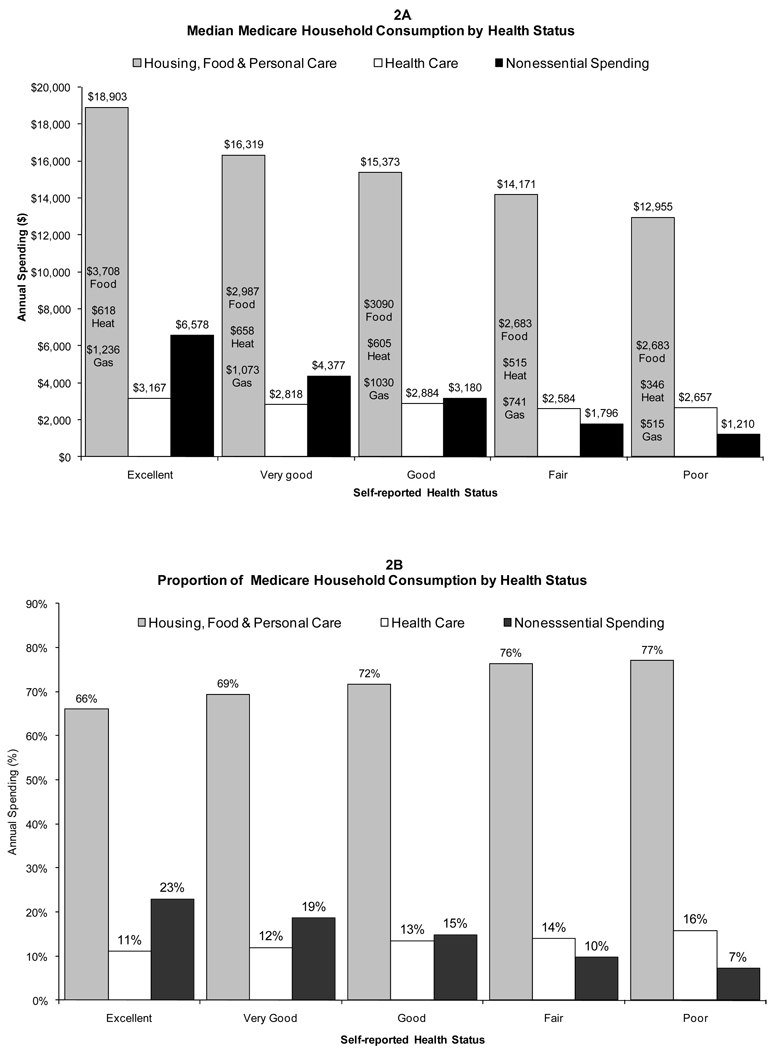

Exhibit 2 illustrates two important points about the relationship between household consumption and health status. First, regardless of health status, Medicare families allocated a large majority of their consumption to basic necessities, both in terms of absolute dollars and as a proportion of consumption. Housing, food, transportation, and personal care expenses made up 66% to 77% of total household consumption. Secondly, however, these basic necessities and health care costs became an even larger share of total consumption as health declined. Compared to families in better health, Medicare families in the poorest health had very few dollars, in either absolute or relative terms, that were not allocated to basic necessities and health care. In other words, an older family reporting fair or poor health had very few dollars allocated to nonessential spending that could be reallocated to health care, if needed. A major change in out-of-pocket health care costs would place these families in economic jeopardy.

Exhibit 2.

Relationship between Medicare Household Consumption and Health Status

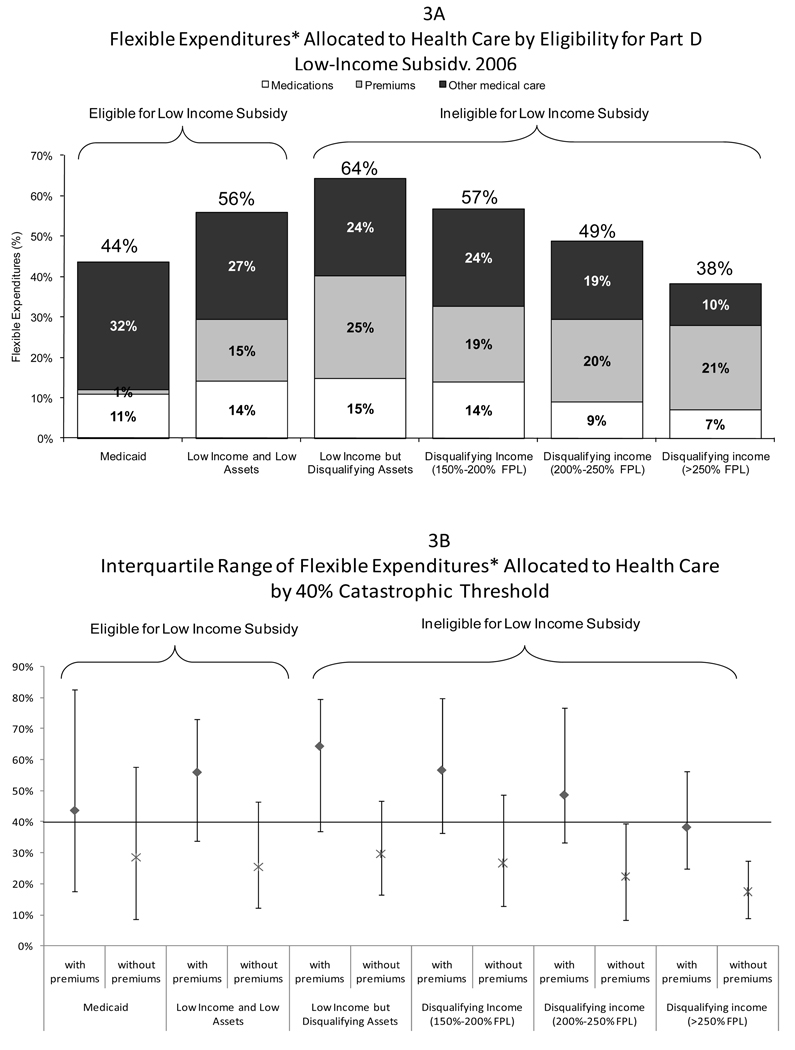

Exhibit 3 shows the relationship between flexible expenditures allocated to health care, eligibility for the Medicare Part D LIS benefit, and the potential for catastrophic health care expenditures. Our analysis identified 21% of our study sample as potentially eligible for the LIS benefit: 12% were eligible through Medicaid status, while another 9% met the low income and low assets thresholds (data not shown). Among the 79% of Medicare enrollees who were ineligible, 5% had low income but disqualifying assets, 21% had disqualifying income under 250% FPL, and 53% had disqualifying incomes greater than 250% FPL.

Exhibit 3.

Flexible Expenditures, Eligibility for Part D Low Income Subsidy, and Threshold for Catastrophic Health Care Expenditures

*Flexible expenditures=total consumption − expenses for housing, food, transportation and personal care

In the top panel of this exhibit, the major categories of health care costs are identified as a proportion of flexible expenditures. Here we see clearly that certain families with high out-of-pocket burden for health care will not qualify for the LIS benefit. Families disqualified for the LIS benefit by the asset test or by having incomes just above the LIS income threshold (150% to 200% of FPL) have the highest ratios of health care costs to flexible expenditures. Furthermore, out-of-pocket costs for health insurance premiums are a much larger burden to these families than medication costs. The bottom panel in this exhibit shows that a large proportion of Medicare families with incomes up to 250% of FPL were already spending above the 40% threshold for catastrophic health care expenditures, especially if spending on insurance premiums is included as a component of out-of-pocket health care costs.

Exhibit 4 shows the adjusted probability that a Medicare family will incur burdensome health care expenditures and eligibility for the Medicare Part D LIS benefit. Medicare families with incomes up to 250% of the Federal Poverty Level are at elevated risk for incurring burdensome health care expenditures compared to wealthier families. This includes a large group who will be ineligible for Part D LIS assistance; after adjusting for health status, families with low income (<150% FPL) but disqualifying assets have more than twice the risk of incurring burdensome health care expenditures as higher income families. In fact, their risk for burdensome health spending is similar to the risk in low income families who qualify for Part D LIS assistance (adjusted odds ratio (AOR) 2.3; 95% CI: 1.3–4.0 vs. AOR 2.2, 95% CI: 1.5–3.2). Families with near-poor incomes of 150–250% FPL are ineligible for Part D LIS assistance, but nonetheless have twice the risk of burdensome health care expenditures compared to higher income families. Finally, Medicare families in poor health have high risk. Even after accounting for their eligibility for the Part D LIS program, families reporting poor health status have an AOR of 2.2 (95% CI: 1.3–3.9) of incurring potentially burdensome health care expenditures relative to families reporting excellent health status.

Exhibit 4.

Adjusted Model of Catastrophic Health Care Expenditures*Among Medicare Enrollees

| Characteristics | Predicted Mean |

Adjusted† Odds Ratio |

95% CI (lower bound) |

95% CI (upper bound) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible for Part D Cost-Sharing Assistance | ||||

| Medicaid-eligible | .57 | 1.21 | 0.80 | 1.82 |

| Low Income and Low Assets | .71 | 2.17 | 1.47 | 3.20 |

| Ineligible for Part D Cost-Sharing Assistance | ||||

| Low Income but Disqualifying Assets | .72 | 2.32 | 1.34 | 4.0 |

| Disqualifying Income (150–200% FPL) | .71 | 2.15 | 1.45 | 3.18 |

| Disqualifying Moderate Income (200–250% FPL) | .59 | 1.41 | 0.99 | 2.03 |

| Disqualifying High Income (>250% FPL) | .49 | ref | ||

| Self-reported Health Status | ||||

| Poor | .68 | 2.24 | 1.30 | 3.86 |

| Fair | .65 | 1.96 | 1.32 | 2.89 |

| Good | .54 | 1.28 | 0.84 | 1.95 |

| Very Good | .49 | 1.16 | 0.77 | 1.75 |

| Excellent | .43 | ref |

Catastrophic health care expenditure is defined as more than 40% of flexible expenditures allocated to health care including insurance premiums

Adjusted for marital status, gender, age, education level, race, Hispanic ethnicity, disabled status, and drug coverage

Discussion

Our analysis reveals that in the year prior to the implementation of Medicare Part D, most Medicare families had only a modest pool of money remaining from which to draw out-of-pocket health care expenses. Two-thirds to three-quarters of total household consumption of Medicare families were allocated to the necessities of housing, food, transportation, and personal care expenses. Any increases in health care expenditures had the potential to ‘crowd out’ other essential budget items and pose threats to the health and welfare of Medicare families.

The Medicare Part D program and the LIS benefit were clearly needed to help shield the neediest Medicare enrollees from burdensome health care costs. Our study demonstrates, however, that Medicare families faced substantial burden for health care costs besides medication costs, especially for health insurance premiums. Medicare Part D and its subsidized premiums may have alleviated some of this burden. The LIS benefit would provide direct and substantial assistance to families who qualified, by offsetting costs related to medications and premiums for drug coverage. These are not trivial costs, especially to families with few resources; however, the LIS benefit would provide no relief from other medical care and general health insurance costs. We found that as many as 26% of the Medicare population, or over 10 million individuals, had incomes and assets that would have disqualified them from LIS assistance, yet their household spending allocations indicated real risk for catastrophic health care costs. In particular, families reporting poor health status exhibited especially high risk. This is consistent with early assessments that the sickest segments of the Medicare population still report high levels of cost-related medication nonadherence and spending less on basic needs to afford medications even after implementation of Medicare Part D.17

Our study has several limitations. Using consumption patterns and essential and nonessential spending categories is a novel way to measure a family’s ability to pay for health care. We believe our approach offers an intuitive method for assessing the protection that health policies offer to Medicare families in need of food, clothing, housing, and transportation. It may be true that spending for essential items may contain nonessential components. However, our analyses showed little evidence of excessive spending within essential categories. For example, in the category of food costs, study families spent a median of $2,683 to feed two adults for an entire year. In comparison, the cost of the USDA Thrifty Food Plan for a family of two aged 51 years or older is $3,480.18 Additionally, the 40% threshold of burdensome expenditures that we selected was arbitrary. However, our ad hoc sensitivity analysis showed consistent results for thresholds varying from 30% to 60% (see technical appendix).

In conclusion, in the year prior to the implementation of Medicare Part D, potentially burdensome health care expenditures were common in Medicare families. Furthermore, our estimates of the income and assets eligibility rules for the Part D Low-Income Subsidy Program indicate a limited scope of relief that may leave many families at-risk. Policymakers should consider eliminating the assets test in the eligibility rules, and providing premium subsides to families with incomes up to 200% FPL.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by The Commonwealth Fund

Contributor Information

Becky A. Briesacher, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Biotech Four, Suite 315, 377 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, Tel: 508-856-3495, FAX: 508-856-5024, Becky.Briesacher@umassmed.edu.

Dennis Ross-Degnan, Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, 133 Brookline Ave, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, Tel: 617-509-9920, FAX: 617-859-8112, Dennis_Ross-Degnan@hms.harvard.edu.

Anita K. Wagner, Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, 133 Brookline Ave, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, Tel: 617-509-9956, FAX: 617-859-8112, anita_wagner@hms.harvard.edu.

Hassan Fouayzi, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Biotech Four, Suite 315, 377 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, Tel: 508-856-4659, Fax: 508-856-3495, Hassan.Fouayzi@umassmed.edu.

Fang Zhang, Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, 133 Brookline Ave, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, Tel: 617-509-9962, FAX: 617-859-8112, Fang_Zhang@harvardpilgrim.org.

Jerry H. Gurwitz, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Division of Geriatric Medicine, Biotech Four, Suite 315, 377 Plantation Street, Worcester, MA 01605, Tel: 508-791-7392, Fax: 508-595-2200, Jerry.Gurwitz@umassmed.edu.

Stephen B. Soumerai, Department of Ambulatory Care and Prevention, Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care, 133 Brookline Ave, 6th Floor, Boston, MA 02215, Tel: 617-509-9942, FAX: 617-859-8112, ssoumerai@hms.harvard.edu.

Notes

- 1.Fidelity Investments, "Rising Health Care Costs Could Consume as Much as 50 Percent of Retirees' Future Social Security Benefits," in Press Release (Boston, MA: 2007), P. Purcell, Retirement Savings and Household Wealth: Trends from 2001–2004, Pub. no. RL30922 The Library of Congress, May 22 2006).

- 2.ABC News/Kaiser Family Foundation/USA Today. Health Care in America 2006 Survey. 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Himmelstein DU, et al. Illness and Injury as Contributors to Bankruptcy. Health Affairs Suppl Web Exclusives. 2005 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w5.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Highlights - National Health Expenditures. 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaufman DW, et al. Recent Patterns of Medication Use in the Ambulatory Adult Population of the United States: The Slone Survey. JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;287(3) doi: 10.1001/jama.287.3.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Madden JM, et al. Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence and Spending on Basic Needs Following Implementation of Medicare Part D. Jama. 2008;299(16) doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. The Medicare Prescription Drug Benefit. Menlo Park, CA: 2008. Feb, [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Press Releases. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. Lower Medicare Part D Costs Than Expected in 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kawabata K, Xu K, Carrin G. Preventing Impoverishment through Protection against Catastrophic Health Expenditure. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(8) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Juster RT, Suzman R. An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study. The Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30(supplement) [Google Scholar]; Willis RJ. Theory Confronts Data: How Hrs Is Shaped by the Economics of Aging and How the Economics of Aging Will Be Shaped by the Hrs. Labour Economics. 1999;9(119–145) [Google Scholar]

- 11.Berki SE. A Look at Catastrophic Medical Expenses and the Poor. Health Affairs. 1986;5(4) doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.5.4.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Wyszewianski L. Financially Catastrophic and High-Cost Cases: Definitions, Distinctions, and Their Implications for Policy Formulation. Inquiry. 1986;23(4) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Xu K, et al. Household Catastrophic Health Expenditure: A Multicountry Analysis. Lancet. 2003;362(9378) doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hurd M, Rohwedder S. Economic Well-Being at Older Ages: Income- and Consumption-Based Poverty Measures in the Hrs. 2006 November; Pub. no. WR-410 RAND. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Briesacher BA, et al. A New Measure of Medication Affordability. Journal of Health and Social Policy. 2008 doi: 10.1080/19371910802672346. (In press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Guidance to States on the Low-Income Subsidy. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rand Hrs Data File. [accessed June 1 2009]; http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/meta/rand/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 16.U.S. Department of Labor and Bureau of Labor Statistics. Consumer Expenditures in 2005. 2007 February [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madden, et al. Cost-Related Medication Nonadherence and Spending on Basic Needs Following Implementation of Medicare Part D. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.16.1922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Center for Nutrition and Promotion. Official Usda Food Plans: Cost of Food at Home at Four Levels, U.S. Average. U.S. Department of Agriculture; 2006. [Google Scholar]