Abstract

This randomized clinical trial examined the efficacy of comprehensive Usual Care (UC) alone (n=42) or enhanced by Reinforcement-Based Treatment (RBT) (n=47) to produce improved treatment outcomes, maternal delivery, and neonatal outcomes in pregnant women with opioid and/or cocaine substance use disorders. RBT participants spent, on average, 32.6 days longer in treatment (p<.001) and almost six times longer in recovery housing than did UC participants (p=.01). There were no significant differences between the RBT and UC conditions in proportion of participants testing positive for any illegal substance. Neonates in the RBT condition spent 1.3 fewer days hospitalized after birth than UC condition neonates (p=.03), although the two conditions did not differ significantly in neonatal gestational age at delivery, birth weight, or number of days hospitalized. Integrating RBT into a rich array of comprehensive care treatment components may be a promising approach to increase maternal treatment retention and reduce neonatal length of hospital stay.

INTRODUCTION

Illicit opioid and/or cocaine use in the context of complex social, physical, and environmental factors are associated with adverse neonatal outcomes such intrauterine growth restriction, pre-term delivery, low birth weight, decreased head circumference, and fetal death.1–5 Treating patients for opioid and/or cocaine use disorders during pregnancy remains a clinical challenge due to the myriad of issues that must be addressed in order to confront the root causes of the substance use disorder(s) in pregnant women. Specialized multidisciplinary treatment programs have been developed6,7 to address the “barriers to care” that prevent pregnant patients with substance use disorders from accessing and engaging in drug abuse treatment. Nevertheless, numerous substance-abusing pregnant patients leave drug abuse treatment prematurely and relapse to drug use, increasing the risks for poor maternal outcomes, premature delivery, long neonatal hospital stays, and neonatal morbidity and mortality.7–10 Therefore, identifying effective interventions for improving the outcomes of women with substance use disorders and their in-utero substance-exposed neonates is vitally important, from both individual and public health perspectives.

Reinforcement-Based Treatment (RBT) is a new and innovative behavioral treatment strategy that may assist in improving maternal and neonatal outcomes. RBT’s theoretical underpinnings include both operant conditioning principles (behavior is a reaction based on past consequences of actions11), and social learning theory (behavior is shaped by understanding of the relationship between the behavior and receiving a reward or punishment, and the value placed on that reward or punishment12). RBT has improved drug treatment (e.g., treatment retention, reduced drug use) and drug abstinence-sustaining outcomes (e.g., employment) in impoverished opioid and cocaine-using men and women.13 RBT was modeled after the Community Reinforcement Approach14,15 and tailored to the needs of inner city heroin-dependent patients not receiving opioid agonist medication treatment and exiting brief residential detoxification programs. In the context of a day treatment program, the treatment provides individual counseling supplemented by abstinence-contingent support for housing, recreational activities, and skills training for securing employment. The abstinence-contingent housing feature, modeled after the work of Milby and colleagues,16 may be especially well-suited to an urban population of pregnant women in treatment for their substance use disorders.

In non-pregnant opioid-dependent patients, compared to a treatment referral condition, RBT has repeatedly show increased treatment engagement in aftercare treatment, engendered greater heroin and cocaine abstinence, and produced significant increases in employment outcomes.13,17,18

Because RBT has demonstrated promising outcomes in samples of non-pregnant women and men using opioids, cocaine and/or alcohol, the next step in development of this treatment approach was to compare it to an active control condition. This comparison seemed best-suited for substance-abusing pregnant women (a population in which drug-abstinence outcomes are particularly important given the concern for the effects of drugs on both maternal and neonatal outcomes, given the complicating factors of poverty and lifestyle issues of drug users). Further, expanding the focus of RBT treatment outcome research to examine the impact of RBT on maternal delivery or neonatal outcomes in addition to maternal substance abuse outcomes and substance abuse treatment retention seemed warranted, given the need to determine the breadth of RBT’s treatment impact.

The purpose of the present study was to examine both the one-month drug treatment outcomes and the maternal and neonatal outcomes of RBT tailored to address the specific issues of pregnant women with opioid and/or cocaine substance use disorders in comparison to an active control condition. Specifically, all pregnant women in this study were provided evidence-based comprehensive care that has been shown to improve maternal and neonatal outcomes relative to no treatment19,20 and it was this Usual Care (UC) condition that was compared to an RBT condition that included specific elements of RBT treatment thought to be critical to maintaining drug abstinence (i.e., recovery housing and employment) as well as individual counseling tailored to the issues of the pregnant participant. The RBT and Usual Care conditions were compared not only on the one-month post-randomization treatment outcomes but also on subsequent critical maternal delivery and neonatal outcomes in order to determine the extent to which RBT produces beneficial effects above and beyond those positive outcomes expected to result from a rich array of usual care comprehensive care services.

METHODS

Setting

Participants were recruited from the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy (CAP) in Baltimore, Maryland, USA. CAP provides a broad array of clinical services to pregnant women with substance use disorders (see Usual Care Condition, below, for details).

Recruitment

Participants were recruited between September 2003 and November 2007. All participants signed an Institutional Review Board approved informed consent form and were randomly assigned to one of two aftercare conditions: Usual Care (see Usual Care Condition, below) alone or Usual Care enhanced with Reinforcement-Based Treatment (see Reinforcement-Based Treatment Condition, below).

Inclusion criteria were: CAP admission, minimum 18 years of age, single fetus, self-reported heroin or cocaine use in the past 30 days, completion of a 7-night inpatient stay on an Assisted Living Unit, and willingness to live in recovery housing or other drug-free housing. Exclusion criteria included: gestational age of 35 or more weeks based on last menstrual period and sonogram, and/or a severe concomitant medical or psychiatric condition that would interfere with study consent or participation.

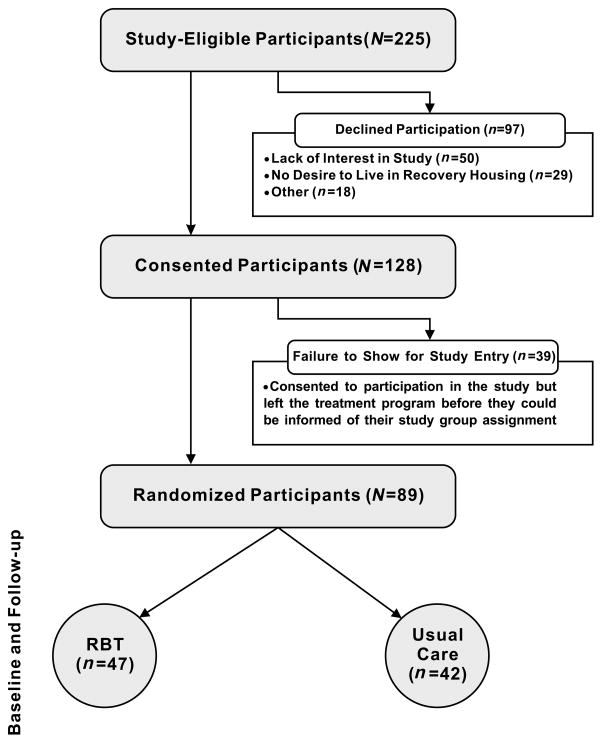

Of the 225 eligible CAP patients, 97 declined participation for the following reasons: lack of interest in the study (n=50), did not want to live in recovery housing (n=29), living out of the area/not returning to CAP (n=4), childcare issues (n=6), other aftercare plans (n=6), declined randomization process (n=1), and employment conflicted with study participation (n=1). Thus, 128 CAP patients signed written informed consent. Of these 128 patients, 39 participants left CAP shortly after consenting to participation in the study but before they could be informed of their study group assignment. The remaining 89 participants were informed of their group assignment and thus were considered randomized. All analyses reported in this paper are based on the data from these 89 participants and their respective 89 neonates. A CONSORT diagram detailing participant flow can be found in Figure 1.

Figure 1. CONSORT Diagram.

Of the 225 eligible CAP patients, 97 declined participation for the following reasons: lack of interest in the study (n=50), did not want to live in recovery housing (n=29), living out of the area/not returning to CAP (n=4), childcare issues (n=6), other aftercare plans (n=6), declined randomization process (n=1), and employment conflicted with study participation (n=1). Thus, 128 CAP patients signed written informed consent. Of these 128 patients, 39 participants left CAP shortly after consenting to participation in the study but before they could be informed of their study group assignment. The remaining 89 participants were informed of their group assignment and thus were considered randomized. All analyses reported in this paper are based on the data from these 89 participants and their respective 89 neonates.

Randomization

The random assignment of participants to one of the two treatment conditions was performed by a staff member with no participant contact who generated a random condition assignment with a computer program. Participants were informed of their random assignment to either Reinforcement-Based Treatment (n=47) or Usual Care (n=42) following the completion of the initial assessment battery and by the time of discharge from the assisted living unit to the intensive outpatient component of CAP.

Intervention Conditions

Usual Care (UC) Condition

CAP care includes treatment for substance use disorders (group and individual counseling and psychoeducation), medically-assisted withdrawal for patients either refusing methadone maintenance or not meeting current opioid dependence criteria, methadone maintenance for qualifying opioid-dependent patients, case management, obstetrical care, psychiatric evaluation and treatment, general medical management, and on-site child care and pediatric care. Maternal treatment commences with a 7-night stay on an assisted living unit (ALU) and is followed by daily intensive outpatient treatment.19,20

Reinforcement-based Treatment (RBT) Condition

The RBT condition was comprised of all the elements of the usual care condition plus the RBT treatment components. Specifically, RBT condition participants received individualized treatment planning, behavior graphing, weekly recreational, vocational and peer reinforcement groups.

On the ALU day of discharge, RBT participants were escorted by study counseling staff to a women’s-only recovery house which allowed children to live in the home. Participants were also transported back to CAP the following morning to facilitate their treatment engagement. All participants completed an alternative housing plan in the event that the participant could no longer live in recovery housing (e.g., for breaking rules, drug use), or if it were determined that the participant’s living environment was not conducive for maintaining drug abstinence. If the participant refused to enter a recovery house, arrangements were made for her to enter another drug-free living environment in order to facilitate abstinence goals. The treatment program maintained a cooperative agreement with several privately-owned-and-operated recovery houses in the community so that immediate housing was always available. The houses provide a structured and supportive drug-free environment. The treatment program paid rent directly to the recovery house manager or owner at a rate of $115 per week. If drug or alcohol use was detected, either at the program or the house, the patient was removed and placed in an alternative living arrangement (e.g., with a relative or at a community shelter) until she once again tested negative for opioids and cocaine. At this time, the participant could re-enter the same house, or move to a different recovery house.

All participants assigned to RBT were requested to attend CAP seven days a week for the first month of outpatient treatment when risk for relapse is high. RBT individual counseling sessions were scheduled 2–3 times a week and included behavior graph review and elements of vocational counseling.21 Recreational activities included outings in the community such as attending poetry readings, seeing movies and participating in arts and crafts activities at the recovery house in a group format. On Fridays, social club was held. During social club, participants were served lunch, reviewed progress on and set recreational goals for the upcoming week, were given the opportunity to interact with non-drug using peers, and received certificates of study counseling attendance achievement in the study.

Opiate and cocaine testing (see Urine Testing below) was conducted twice a week, typically on Monday and Thursdays. Any missed samples were collected at the next face-to-face visit. Procedures for addressing a urine sample that tested positive for opioids and/or cocaine included a time-out from reinforcer availability. A urine-positive participant met with her counselor individually for a relapse focused session that included a functional analysis, detailed day planning and problem-solving strategies. The alternative housing plan was also reviewed and the patient was removed from the recovery house and placed in another safe housing situation (e.g., temporary shelters sponsored by local churches) until abstinence was reestablished. During the course of treatment (from delivery until one-month follow-up), 5 women were removed from recovery housing and placed into a safe housing situation; of these 5 women, 3 were subsequently returned to their recovery housing setting.

Drug abstinent-contingent benefits were in effect for 6 months, the duration of RBT treatment, and were available to participants who tested negative for opioids and cocaine. The present study focuses on the one-month post-randomization drug treatment outcomes as the gestational age criteria for study entry was inclusive of 32 weeks; thus, examining the first month of treatment response allowed for examination of treatment response during the time at which all participants were pregnant as well as the examination of delivery and neonatal outcomes. Moreover, maternal and neonatal outcomes at delivery were also examined.

Recovery Housing

Cooperative agreements were in place during the trial with several recovery houses in the community. This allowed participants to be quickly transferred to one of these houses on the first day of their participation. The recovery house environment was similar to a group home [i.e., overseen by a manager that is in recovery from drug and/or alcohol use disorder(s), common kitchen and living room, and multi-bed sleeping rooms, structured rules to follow]. If drug or alcohol use is detected, either at the program or the house, the patient is removed and placed in an alternative living arrangement (e.g., with a relative or at a community shelter) until s/he once again tests negative for opiates and cocaine. Upon testing drug-negative, the patient may reenter the same house, or more commonly, move to a different recovery house. It is more common for the participant to move to a different house because many recovery houses require a two-week waiting period before residents can return to live in the house. The cost of recovery housing was typically $115 per week.

All UC participants were informed about recovery housing and its potential importance in maintained drug abstinence. They were provided with a list of recovery housing resources in the community which included all of those houses used for RBT participant placement. They were provided with access to a telephone to call and access recovery housing. No payment was provided to the recovery house to pay for their rent.

All RBT participants were strongly encouraged to enter a drug-free living environment in order to facilitate their drug abstinence goals. The treatment program paid rent on the participant’s behalf contingent upon demonstrated drug-abstinence. Paid abstinent-contingent recovery housing was available for up to six months contingent on twice-weekly drug-free urinalysis results.e.g.,16

Data Sources

Outcome information was collected at two points in time. Post-natal maternal outcomes were measured one month following delivery, while maternal delivery and neonatal outcomes were collected immediately following delivery.

Addiction Severity Index (ASI)

Participants completed the ASI22 prior to randomization while residing on the assisted living unit at CAP and then one month later after randomization. The ASI is a semi-structured interview assessing both lifetime and recent (30 days prior to treatment entry) events and behaviors in seven domains (medical, employment, drug, alcohol, legal, family/social, and psychiatric). The ASI also captured selected maternal characteristics (e.g., age, race, education) at treatment entry. Specific items within each domain of the ASI were used to assess short-term response to the treatment conditions. All interviewers’ training and on-going inter-rater reliability has been previously described.19 The self-reported drug use data were confirmed with urine testing results.

Urine testing

Observed urine samples were tested on-site for opioids and cocaine using On-Track test sticks23 with concentration cut-offs of 300 ng/ml. The mean number of urine samples collected from participants did not differ between the RBT condition (M=11.4) and the UC condition (M=11.2), p > .9.

Medical co-morbidities, treatment status at delivery, maternal delivery and neonatal medical documentation

Days retained in CAP treatment and CAP enrollments at delivery were captured from CAP billing records. Maternal and neonatal delivery data were collected from documents completed by clinical staff during the care of the patient. Maternal urine toxicology at delivery was gathered from hospital laboratory results (tested for opioids, cocaine, barbiturates and/or benzodiazepines). All neonatal data were tracked from delivery until hospital discharge.

Outcome Measures

Study measures assessed outcomes in three domains: treatment, maternal delivery, and neonatal. Treatment outcome measures included days retained in CAP treatment before delivery, as well as measures administered at baseline (treatment entry) and 1-month following randomization to the study. These latter measures consisted of past 30-day: number of days in recovery housing; heroin and cocaine use, verified by urinalysis testing (yes v. no); employment status (employed v. unemployed); and illegal activity (yes v. no). Maternal delivery outcomes included: enrollment at CAP at delivery (yes v. no) and urine drug screening positive for any illegal drug at delivery (yes v. no). Neonatal outcome measures included: estimated gestational age at delivery; prematurity, defined as delivery at less than 37 weeks (yes v. no); birth weight (grams); and number of days hospitalized after birth.

Statistical Models

Separate analyses were conducted for each of the outcome variables. The maternal and neonatal delivery-related outcome measures were evaluated by a factor representing the between-subjects effect of Treatment (RBT v. UC). In the case of the treatment outcome measures that were measured repeatedly, a within-subjects factor representing Time (Baseline v. 1-month Follow-up) was added to the statistical model, along with the Treatment × Time interaction. Logistic regression was used to analyze the binary maternal and neonatal outcome measures (enrolled in CAP at delivery, urine drug screening positive for any drug, and prematurity); ordinary least squares regression for the continuous measure of birth weight, and Poisson regression for estimated gestational age at delivery, and number of days hospitalized after birth. In the case of treatment outcome measures, a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model was utilized for the binary outcome measures (heroin and cocaine use, employment status, and illegal activity), while a generalized linear mixed model approach was employed in the analyses of the Poisson outcome measures of the number of days in CAP treatment and recovery housing. Tests of simple main effects were employed following a significant Treatment × Time interaction; in the case of the GEE analyses, the resulting t tests had fractional df.

Model-derived least squares means are reported for the ordinary least squares and Poisson regression results. [The Poisson means are exponentiated to allow interpretation of findings based on the original units of measurement of the outcome variable.] Interpretation of the logistic regression results focused on the exponentiated regression coefficients, or odds ratios.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Participant (N=89) demographic and background characteristics are shown in Table 1. [It should be noted that each mother gave birth to a single, live neonate.]

Table 1.

Demographic and Background Characteristics for the Total Sample (N=89) and the Usual Care and RBT Conditions

| Total Sample (N=89) | Usual Care (n=42) | RBT (n=47) | Test Statistic (χ2 or t) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Age | 30.7 (5.9) | 30.5 (5.6) | 30.9 (6.2) | t(86)=−.3 | .79 |

| Estimated Gestational Age (EGA) at Study Entry | 20.5 (7.9) | 20.1 (8.5) | 20.9 (7.6) | t(77)= −.4 | .67 |

| Years of Education | 11.6 (1.5) | 11.6 (1.7) | 11.7 (1.3) | t(86)= −.3 | .77 |

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |||

| Race | χ2(1)=.2 | .69 | |||

| Black | 50 (56%) | 25 (59.5%) | 25 (53.2%) | ||

| White | 38 (43%) | 17 (40.5%) | 21 (44.7%) | ||

| Other | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (2.1%) | ||

| Marital Status | χ2(1)=3.5 | .06 | |||

| Not-Married | 77 (87.5%) | 33 (80.5%) | 44 (93.6%) | ||

| Married | 11 (12.5%) | 8 (19.5%) | 3 (6.4%) | ||

| Currently Employed | 8 (9.1%) | 3 (7.3%) | 5 (10.7%) | χ2(1)=.3 | .57 |

| Currently Living in Private Residence | 62 (72.5%) | 30 (73.2%) | 32 (68.1%) | χ2(1)=.3 | .60 |

| Planned Pregnancy | 11 (14.3%) | 7 (20.6%) | 4 (9.3%) | χ2(1)=2.0 | .16 |

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Number of Previous Pregnancies | 3.6 (2.6) | 3.3 (2.7) | 3.6 (2.6) | t(87)= −.9 | .38 |

| Number of Previous Live Births | 2.5 (2.2) | 2.4 (2.4) | 2.6 (2.1) | t(87)= −.5 | .60 |

| Addiction Severity Index Composite Scores | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Medical | .31 (.35) | .29 (.39) | .33 (.32) | t(87)= −.5 | .60 |

| Employment | .84 (.20) | .82 (.19) | .86 (.20) | t(87)= −1.0 | .34 |

| Drug | .28 (.11) | .27 (.11) | .28 (.12) | t(87)= −.4 | .70 |

| Alcohol | .03 (.10) | .01 (.05) | .05 (.12) | t(87)= −1.8 | .08 |

| Legal | .18 (.23) | .13 (.19) | .23 (.26) | t(87)= −2.3 | .03 |

| Psychiatric | .18 (.22) | .18 (.23) | .18 (.22) | t(87)=.1 | .93 |

| Family/Social | .24 (.27) | .29 (.29) | .20 (.24) | t(87)=1.7 | .09 |

| Lifetime Psychological Adjustment | |||||

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |||

| Serious Depression | 47 (53.4%) | 17 (41.5%) | 30 (63.8%) | χ2(1)=4.4 | .036 |

| Serious Anxiety | 37 (42.1%) | 14 (34.2%) | 23 (48.9%) | χ2(1)=2.0 | .16 |

| Attempted Suicide | 27 (30.7%) | 11 (26.8%) | 16 (34.0%) | χ2(1)=.5 | .46 |

| Past 30 Days Injection Status | |||||

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |||

| Injected Heroin | 27 (30.3%) | 14 (33.3%) | 13 (27.7%) | χ2(1)=.34 | .56 |

| Injected Cocaine | 11 (12.4%) | 4 (9.5%) | 7 (14.9%) | χ2(1)=.59 | .44 |

| Past 30 Days of Use | |||||

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | |||

| Nicotine | 24.1 (11.3) | 24.3 (11.2) | 24.0 (11.6) | t(86)=.1 | .89 |

| Alcohol | 2.3 (5.6) | 1.1 (2.8) | 3.4 (7.1) | t(86)= −1.9 | .06 |

| Marijuana | 1.4 (4.9) | .7 (2.5) | 1.9 (6.3) | t(86)= −1.1 | .26 |

| Cocaine | 13.4 (12.2) | 13.1 (11.8) | 13.7 (12.8) | t(86)= −.2 | .82 |

| Opiates | 14.9 (13.6) | 16.1 (13.5) | 13.8 (13.8) | t(86)=.8 | .43 |

| Number of past drug treatments | 3.1 (3.1) | 3.2 (2.6) | 3.0 (3.6) | t(86)=.4 | .72 |

| Medical Co-Morbidities | |||||

| f (%) | f (%) | f (%) | |||

| HIV-positive† | 3 (4.3%) | 0 | 3 (7.3%) | χ2(1)=2.2 | .14 |

| Hepatitis-B positive† | 8 (11.4%) | 2 (6.7%) | 6 (15.0%) | χ2(1)=1.2 | .28 |

| Hepatitis-C positive† | 24 (33.8) | 12 (40.0%) | 12 (29.3%) | χ2(1)=.9 | .35 |

Notes. χ2 goodness-of-fit test for Race collapsed the “Other” group into the “Black” group. The questions regarding age, race, marital, employment, and living status were derived from the ASI, as were questions regarding past 30 day injection status and drug use, while questions regarding pregnancy and birth status were derived from questions that were added to the ASI for the purposes of the present study. Estimated gestational age (EGA) at study entry was derived from the date of the last menstrual period. As part of the obstetrical care at the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy, patients in treatment past 20 weeks EGA have a confirmatory sonogram. Thus, for those participants entering treatment after 20 weeks, their initial EGA was be determined by the sonogram since this is a more accurate method for determining EGA later in pregnancy.

n = 70, missing participants are due to refusal of the tests. Percentages are within the respective group.

Treatment Outcome Measures

As shown in Table 2, there was a significant Treatment effect with the RBT condition being retained in treatment for significantly more days than the UC condition. During the first month of treatment, there was a significant Treatment × Time interaction for number of days in recovery housing in the past 30 days. Tests of simple main effects of Time within Treatment indicated that RBT showed a significant increase in number of days in recovery housing from baseline to 1-month follow-up, t(134.6) = 3.9, p<.001, while the Usual Care condition did not, p>.16] an almost six-fold difference in number of days in recovery housing at one month between RBT and UC. Although the corresponding Treatment × Time interaction effects were nonsignificant, there were significant Time main effects for both heroin and cocaine use, χ2(1)=19.9, p<.001 and χ2(1)=41.0, p<.001, respectively, with the likelihood of both heroin and cocaine use decreasing in the 30-day period in question. Finally, although illegal activity declined from baseline to on-month assessment similarly in the two treatments conditions, from 21% and 22% to 4% and 0% in the RBT and UC conditions, respectively, the activity at one-month follow-up was at such a low level as to preclude inferential analysis.

Table 2.

Parameter Estimates and Tests of Significance for Outcome Measures

| Usual Care (n=42) | RBT (n=47) | Treatment × Time Test Statistic | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal Treatment | ||||

| M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Days in Recovery Housing | χ2(1)=6.6 | .01 | ||

| Baseline | 1.46 (.83) | .34 (.37) | ||

| Follow-up | 3.70 (1.73) | 21.55 (3.80) | ||

| Heroin-Positive | χ2(1)=.6 | .44 | ||

| Baseline | .75 (.37) | .65 (.31) | ||

| Follow-up | .40 (.38) | .39 (.34) | ||

| Cocaine-Positive | χ2(1)=2.0 | .16 | ||

| Baseline | .89 (.54) | .81 (.52) | ||

| Follow-up | .19 (.39) | .30 (.39) | ||

| Employed | χ2(1)=.3 | .60 | ||

| Baseline | .12 (.48) | .09 (.52) | ||

| Follow-up | .05(.95) | .07 (.75) | ||

| Treatment Main Effect Test Statistic | ||||

| Days Retained in CAP Treatment | 41.9 (6.0) | 74.4 (7.4) | χ2(1)=11.6 | <.001 |

| Maternal Delivery | ||||

| % | % | |||

| Odds Ratios (Confidence Interval) | ||||

| CAP Enrollment at Delivery | 29.0% | 28.6% | χ2(1)=0.0 | 1.0 |

| OR=1 (.37, 2.85) | ||||

| Urine Toxicology Positive for any Illegal Drug | 17.7% | 31.0% | χ2(1)=1.0 | .32 |

| OR=.48 (.11, 2.08) | ||||

| Neonatal | ||||

| % | % | |||

| Odds Ratios (Confidence Interval) | ||||

| Prematurity | 26.7% | 30.0% | χ2(1)=.05 | .82 |

| OR=.85 (.21, 3.39) | ||||

| M (SE) | M (SE) | |||

| Gestational Age at Delivery | 38.5 (1.6) | 37.2 (1.1) | χ2(1)=.42 | .52 |

| Birth Weight (gms) | 2996.3 (198.8) | 2708.3 (143.0) | F(1, 42)=1.4 | .25 |

| Days hospitalized after birth | 4.2 (.53) | 2.9 (.35) | χ2(1)=4.7 | .03 |

Maternal Delivery-related Outcomes

Of the 2 maternal delivery-related outcomes, RBT was no more advantageous that Usual Care. Both groups retained patients in treatment approximately 70% of the time and yielded at least 69% negative urine drug screening test results at delivery (both ps>.3).

Neonatal Delivery-related Outcomes

Of the 4 neonatal delivery-related outcomes, only the number of days hospitalized after birth showed a significant difference between conditions, with neonates in the RBT condition spending 1.3 fewer days in the pediatric nursery than Usual Care condition, on average, χ2(1)=4.7, p<.03.

DISCUSSION

The ability of RBT to retain participants in drug treatment is consistent with prior studies of RBT in non-pregnant patient.e.g.,17 Retention in drug treatment has been associated with improved longer-term treatment outcomes, including drug abstinence, improved maternal-child relationships, and employment.24,25 The dramatically shorter treatment retention in the Usual Care condition affirms the efficacy of RBT as a part of a comprehensive treatment program. RBT’s efficacy in improving treatment retention may be centered around its focus on having every interaction with each participant be one that is positively reinforcing to the participant. RBT has a strength-based focus and methods for breaking large goals (e.g., drug abstinence, obtaining a job) into small, concrete steps that are tracked thereby increasing participant’s accountability for her behavior and provided multiple opportunities each week for positive reinforcement from staff about her progress. Finally, RBT’s proactive outreach and assistance of participants though compiled social service systems are seen positively by the participants and may each be factors in the increased retention.

In terms of substance use disorder treatment outcomes, as expected, relative to UC, RBT showed efficacy in increasing the number of days participants lived in recovery housing.

These results suggest that recovery housing may be beneficial to pregnant patients recovering from substance use disorders by removing stimuli associated with drug use while providing monitoring and social support for abstinence from substances; however, it is not always viewed as an attractive option by all substance-abusing pregnant women due to the rules and restrictions imposed by the recovery house lifestyle. These results are also somewhat consistent with previous research in non-pregnant participants that has also shown that drug-free housing promotes treatment retention,e.g.,26 but not necessarily drug abstinence.17,27 Future studies to explore other models of supported housinge.g.,16 that might better retain patients and increase efficacy of drug use abstinence while being more attractive to individuals recovering from addiction may be of considerable interest.

Although at first look, the lack of significant differences between opiate and cocaine abstinence rates in RBT versus UC appears in contrast to previous comparisons of RBT and usual care conditions in non-pregnant patients. However, all prior studies compared RBT against a very brief and minimal ’standard care’ condition of referrals to other community treatment programs. Thus, although heroin and cocaine drug abstinence rates with RBT were not significantly different from the Usual Care condition in the present study, the fact that both groups showed significant improvements with time and relatively low rates of positive urine test results at delivery speaks to the relative success of an intensive usual comprehensive care approach in producing favorable drug use outcomes in pregnant women, thereby decreasing the ability to uncover significant differences between RBT and UC.

Of central importance to this study are the neonatal delivery-related outcomes. There was a statistically significant difference between the two conditions in the length of hospitalization after birth. Specifically, neonates of mothers who received RBT were discharged from the hospital 1.3 days earlier than neonates of mothers who received Usual Care. While the exact reasons driving the shorter hospitalization are elusive at this point, it may be the case that RBT improved certain unmeasured lifestyle factors (e.g., improved nutrition as nutritious meals are provided in the recovery houses) or RBT may have resulted in more subtle reductions in the quantity and/or frequency of drug that were not detected in this study. Finally, a reduction in hospitalization days of 31% as observed in this study with RBT relative to UC has the potential to amount to substantial reductions in health care costs to society.

The present sample of drug-dependent pregnant patients has, on average, characteristics comparable to similar such participants in other published studies. For example, the average patient characteristics include mean age in the mid-childbearing age, with a majority being unemployed, unmarried, and poly-drug users including nicotine.8,28,29 Because the maternal characteristics of the present sample are similar to those characteristics of mothers in other reports, these similarities support the ability to generalize from these findings to the larger population of pregnant women treated for substance use disorders.

Limitations to this study deserve comment. First, a broader array of maternal treatment outcomes measured over a longer period of time as complements to the delivery and one-month outcomes might have proven informative. However, because of the somewhat exploratory nature of this study for pregnant women, a focus on one-month outcomes seemed the most appropriate for both the behavioral maternal measures and the neonatal outcomes. Second, the fact that 43% of potential participants declined to participate, and 17% failed to enter treatment following randomization suggests that the treatment options may not have been overly attractive to these women. However, of the 43% who declined to participate, 51% (22% of the total pool of potential participants) did so because they were not interested in the study, while only 30% (13% of the total pool of potential participants) were not interested in recovery housing. These numbers suggest that recovery housing in and of itself may not be an unattractive feature of a treatment intervention, and did not play a critical role in declining participation. Moreover, although it is disappointing that 30 (39/128) of the participants who consented to participate dropped out prior to learning their treatment assignment, the population of pregnant women, who are abusing multiple substances are quite fluid and this drop-out rate may reflect the need for different treatment regimens (e.g., more medication and non-medication comfort measures and/or change in treatment intensity) to better address the detoxifying pregnant patient’s needs. Third, it might be argued that the present study is one in which contingency management wasn’t effective in producing behavior change. However, it is also the case that the UC participants showed significant positive change in a number of treatment outcome measures, suggesting that the intensive comprehensive usual care was itself a reasonably effective treatment approach. Further, the reward of rent paid to the recovery house may not have represented the critical components of effective contingency management (i.e., a tangible reward that is highly valued by the participant and is provided quickly after the behavior is emitted). As such, future studies of RBT should examine the use of rewards that are more diverse, of higher magnitude and tailored to the participant. Fourth, although it cannot be discounted that the efficacy of RBT is due simply to more time and attention provided to participants in the RBT condition, yet having a time and attention matched control group would have minimized our ability to examine the outcomes from RBT in the proper perspective – understanding the efficacy of abstinence-contingent recovery house placement combined with specialized individual counseling.

Finally, because a no-care condition was avoided due to ethical constraints, caution needs to be exercised in interpreting any change from baseline to one-month follow-up reflecting a treatment impact rather than simply a maturation effect. Nonetheless, this controlled study adds additional support to the literature demonstrating the efficacy of comprehensive care in engendering drug abstinence and the efficacy of RBT added to that care to reduce the length of neonatal hospitalization following birth.

There were several strengths to the present study. First, the prospective random assignment to conditions boosts the strength with which conclusions can be drawn. Second, the lack of negative birth outcomes (i.e., lack of prematurity) in both groups demonstrates the utility of a comprehensive care model for pregnant women. Finally, all treatment, obstetrical care, deliveries, and neonatal observations were performed within a single hospital and by one group of experienced medical practitioners. In summary, the results of this randomized study suggest that Reinforcement-Based Treatment integrated into a rich array of comprehensive care treatment components is a promising approach to increase maternal retention in treatment and days in recovery housing as well as reduce neonatal length of hospital stay after birth.

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by grant R01-14979 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Jones).

We thank Heather Fitzsimons, Jennifer Facteau, Judy Jakubowski and the other Center for Addiction and Pregnancy (CAP) Research and Clinical staff for their effort and support in conducting this study.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Blinick G, Wallach RC, Jerez E, Ackerman BD. Drug addiction in pregnancy and the neonate. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1976;125:135–142. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(76)90583-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blinick G, Wallach RC, Jerez E. Pregnancy in narcotics addicts treated by medical withdrawal: The methadone detoxification program. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1969;105:997–1003. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(69)90117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Naeye RL, Blanc W, Leblanc W, Khatamee MA. Fetal complications of maternal heroin addiction: Abnormal growth, infections and episodes of stress. J Pediatrics. 1973;83:1055–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(73)80550-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finnegan LP. Perinatal substance abuse: Comments and perspectives. Seminars in Perinatology. 1991;15:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schempf AH. Illicit drug use and neonatal outcomes: a critical review. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2007;62:749–757. doi: 10.1097/01.ogx.0000286562.31774.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jansson LM, Svikis D, Lee J, et al. Pregnancy and addiction. A comprehensive care model. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaltenbach K, Finnegan L. Prevention and treatment issues for pregnant cocaine-dependent women and their infants. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1998;846:329–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaltenbach K, Berghella V, Finnegan L. Opioid dependence during pregnancy. Effects and management. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1998;25:139–151. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8545(05)70362-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Haller DL, Knisley JS, Dawson KS, et al. Perinatal substance abusers. Psychological and social characteristics. J Nervous Mental Dis. 1993;181:509–513. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199308000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jones HE, O’Grady KE, Malfi D, Tuten M. Methadone maintenance vs. methadone taper during pregnancy: maternal and neonatal outcomes. Am J Addict. 2008;17:372–386. doi: 10.1080/10550490802266276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Skinner BF. Beyond freedom and dignity. New York: Knopf; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rotter JB. The development and applications of social learning theory. New York: Praeger; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones HE, Wong CJ, Tuten M, Stitzer ML. Reinforcement Based Therapy: 12-Month Evaluation of an Outpatient Drug-free Treatment for Heroin Abusers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Budney AJ, Higgins ST. National Institute on Drug Abuse Therapy Manuals for Addiction: Manual 2, A Community Reinforcement Plus Vouchers Approach: Treating Cocaine Addiction. Rockville, Md: US Dept of Health and Human Services; 1998. NIH publication 98–4309. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meyers RJ, Smith JE. Clinical Guide to Alcohol Treatment: The Community Reinforcement Approach. New York: The Guilford Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Milby JB, Schumacher JE, Wallace D, Freedman MJ, Vuchinich RE. To house or not to house: the effects of providing housing to homeless substance abusers in treatment. Am J Public Health. 2005;95:1259–1265. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.039743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gruber K, Chutuape MA, Stitzer ML. Reinforcement-based intensive outpatient treatment for inner city opiate abusers: A short-term evaluation. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;57:211–223. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz EC, Gruber K, Chutuape MA, Stitzer ML. Reinforcement-based outpatient treatment for opiate and cocaine abusers. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2001;20:93–98. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(00)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Svikis DS, Golden AS, Huggins GR, et al. Cost-effectiveness of treatment for drug-abusing pregnant women. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1997b;45:105–113. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(97)01352-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jansson LM, Svikis DS, Velez M, Fitzgerald E, Jones HE. The impact of managed care on drug-dependent pregnant and postpartum women and their children. Subst Use Misuse. 2007;42:961–974. doi: 10.1080/10826080701212451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Azrin NH, Besalel VA. Job Club Counselor’s Manual: a behavioral approach to vocational counseling. PRO-ED inc; Austin, TX: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 22.McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Towt J, Tsai SCJ, Hernandez M, et al. ONTRAK TESTCUP: A novel, on-site, multi-analyte screen for the detection of abused drugs. J Analyt Toxicol. 1995;19:504–510. doi: 10.1093/jat/19.6.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grella CE, Joshi V, Hser YI. Program variation in treatment outcomes among women in residential drug treatment. Eval Rev. 2000;24:364–383. doi: 10.1177/0193841X0002400402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dahlgren L, Willander A. Are special treatment facilities for female alcoholics needed? A controlled 2-year follow-up from a specialized female unit (EWA) versus a mixed male/female treatment facility. Alcohol Exp Clin Res. 1989;13:399–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1989.tb00366.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hitchcock HC, Stainback RD, Roque GM. Effects of halfway house placement on retention of patients in substance abuse aftercare. Am J Drug Alc Abuse. 1995;21:379–390. doi: 10.3109/00952999509002704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moos RH, Pettit B, Gruber V. Longer episodes of community residential care reduce substance abuse patients’ readmission rates. J Stud Alcohol. 1994;56:433–443. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1995.56.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kissin WB, Svikis DS, Moylan P, Haug NA, Stitzer ML. Identifying pregnant women at risk for early attrition from substance abuse treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2004;27:31–38. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miles DR, Kulstad JL, Haller DL. Severity of substance abuse and psychiatric problems among perinatal drug-dependent women. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2002;34:339–346. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2002.10399974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]