Abstract

Background

Peri-implantitis (PI) is an inflammatory disease which leads to the destruction of soft and hard tissues around osseointegrated implants. The subgingival microbiota appears to be responsible for peri-implant lesions and although the complexity of the microbiota has been reported in PI, the microbiota responsible for PI has not been identified.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to identify the microbiota in subjects who have PI, clinically healthy implants, and periodontitis-affected teeth using 16S rRNA gene clone library analysis to clarify the microbial differences.

Design

Three subjects participated in this study. The conditions around the teeth and implants were evaluated based on clinical and radiographic examinations and diseased implants, clinically healthy implants, and periodontally diseased teeth were selected. Subgingival plaque samples were taken from the deepest pockets using sterile paper points. Prevalence and identity of bacteria was analyzed using a 16S rRNA gene clone library technique.

Results

A total of 112 different species were identified from 335 clones sequenced. Among the 112 species, 51 (46%) were uncultivated phylotypes, of which 22 were novel phylotypes. The numbers of bacterial species identified at the sites of PI, periodontitis, and periodontally healthy implants were 77, 57, and 12, respectively. Microbiota in PI mainly included Gram-negative species and the composition was more diverse when compared to that of the healthy implant and periodontitis. The phyla Chloroflexi, Tenericutes, and Synergistetes were only detected at PI sites, as were Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, and Solobacterium moorei. Low levels of periodontopathic bacteria, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis and Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, were seen in peri-implant lesions.

Conclusions

The biofilm in PI showed a more complex microbiota when compared to periodontitis and periodontally healthy teeth, and it was mainly composed of Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Common periodontopathic bacteria showed low prevalence, and several bacteria were identified as candidate pathogens in PI.

Keywords: dental implants, peri-implant infection, periodontal disease, peri-implant microbiota, biofilm, microbiology

Osseointegrated titanium implants have become an important alternative to conventional prostheses for the replacement of missing teeth (1, 2). On the other hand, with the increasing demand for dental implants, dental implant failure is also being reported more frequently (3–8). Peri-implantitis (PI) is an inflammatory disease affecting soft and hard tissues around the osseointegrated implants, which can cause an early implant failure (9–11). Several factors, such as bacterial infection and/or excessive occlusal stress, are associated with the occurrence of the disease and the microbiological factors of PI have been of particular interest (11–13). After the insertion of titanium implants, rapid colonization of bacteria has been observed at the peri-implant sulcus (14). Some microbiological studies have shown that implants affected by PI tend to harbor microbiota encompassing periodontal pathogen species, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Tannerella forsythia, Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, Prevotella intermedia, and Fusobacterium species (15–20). Leonhardt et al. (17) also reported that less common oral species, such as staphylococci, enteric species, and yeasts, were recovered from failing implants. These findings indicate the complexity of the microbiota in PI and the species responsible for PI remain unclear. It is also possible that unknown bacteria are involved in the lesions. As pockets around the remaining teeth may act as a bacterial reservoir, the composition of the peri-implant microbiota is likely to be similar to that around teeth. However, few studies have evaluated the differences in bacterial composition between dental implants and remaining teeth in the same subjects.

In a recent study, molecular techniques such as oligonucleotide probes, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization have been applied to identify the bacteria in PI (20–25). However, these approaches only detect specific target bacteria and are not practical for identifying the true diversity of potential pathogens in the pockets of PI. In contrast, PCR amplification of conserved regions of the 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene followed by clone library construction has been used to comprehensively identify various microbiotas. This approach allows the detection of almost every species in a given sample and is able to indicate the presence of previously uncultivated and unknown bacteria (26).

The aim of this study was to determine the microbiota in subjects with PI, clinical healthy implants, and periodontal teeth using 16S rRNA gene clone library analysis, and to clarify the microbial differences.

Materials and methods

Subjects and clinical examination

Three subjects with PI, a clinically healthy implant, and a periodontally diseased tooth were selected. Subjects were non-smokers and in good general health. They had not received systemic antibiotics, anti-inflammatory drugs, or oral anti-microbial agents within the last 3 months. The investigation was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Tokyo Medical and Dental University, and a written informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Clinical examinations were performed for the selected teeth and implants. The following clinical parameters were assessed at six sites per tooth and at six sites per implant (mesiobuccal, buccal, distobuccal, mesiolingual, lingual, and distolingual): (1) probing depth (PD), (2) bleeding on probing (BOP), (3) suppuration (SUP), and (4) Gingival Index (GI) (27). Intra-oral periapical radiographs (Insight dental films, Eastman Kodak Company, SP, Japan) were obtained using the parallel technique. Radiographs were analyzed for peri-implant bone loss by the same examiner using the smooth components and threads of the implants as reference points. Based on clinical and radiographic data, a diseased implant, a clinically healthy implant, and a periodontally diseased tooth were selected for plaque sampling in each subject. Diseased implants (implants with PI) showed PD≥5 mm with BOP and/or SUP and concomitant radiographic bone loss (bone loss more than three threads up to half of the implant length). Healthy implants (H) showed PD<4 mm without BOP and SUP, and radiographic bone loss. All implants for sampling were treated as single stand prostheses. Periodontally diseased teeth (P) showed PD≥4 mm with BOP.

Sample collection and bacterial DNA isolation

Subgingival plaque samples were obtained from the deepest pockets at the implants with/without PI. In addition, samples from the deepest pockets of the periodontally diseased tooth, not adjacent to the implant were collected. Two weeks before sampling, we performed periodontal examination for all of the residual teeth and implants. PD, BOP, and SUP were measured at six points per tooth as pre-examination and together with radiographic evaluation, sampling sites were decided. Sampling sites were isolated with sterile cotton rolls. Supragingival plaque was removed with sterile cotton pellets. Three paper points were inserted into a pocket until resistance was felt. After 30 s, all paper points were removed and placed in a sterile tube with 1 ml of sterile distilled water.

Samples were mixed for 1 min using a vortex mixer. After removing the paper point, each sample was collected by centrifugation at 12,000g for 5 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 150 µl of lysis buffer from a bacterial DNA extraction kit (Mora-extract, AMR Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Samples were then incubated for 10 min at 90°C and total bacterial genomic DNA was isolated using the Mora-extract kit. Total bacterial DNA was eluted with 200 µl of TE buffer (AMR Inc.) and was stored at −20°C.

16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene clone library analysis

16S rRNA gene clone library analysis was performed as described previously (28, 29). Briefly, the primers used for PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene were 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). PCR reaction mixture (100 µl) containing 10 µl of extracted DNA, 2.5 U of TaKaRa Ex taq® (TAKARA BIO Inc., Otsu, Japan), 10 µl of 10× Ex Taq buffer, 8 µl of dNTP mixture (0.2 mM each), and 50 pmol of each primer. PCR amplification was performed using a Veriti 200 PCR Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) with the following program; 95°C for 3 min, followed by 15 cycles of 95°C for 30 s, 50°C for 30 s, 72°C for 1.5 min and a final extension period of 72°C for 10 min. PCR products were purified using a QIAquick PCR purification kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA, USA).

Purified amplicons were ligated into plasmid vector pCR®2.1 and then transformed into One Shot® INVaF′ competent cells using the Original TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, CA, USA). Plasmid DNAs were prepared using the TempliPhi DNA Amplification Kit (GE Healthcare, Buckinghamshire, UK) from randomly selected recombinants and used as templates for sequencing. Sequencing was conducted using the 27F and 520R primers, a BigDye Terminator Cycle Sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems), and a 3130xl Genetic Analyzer (Applied Biosystems).

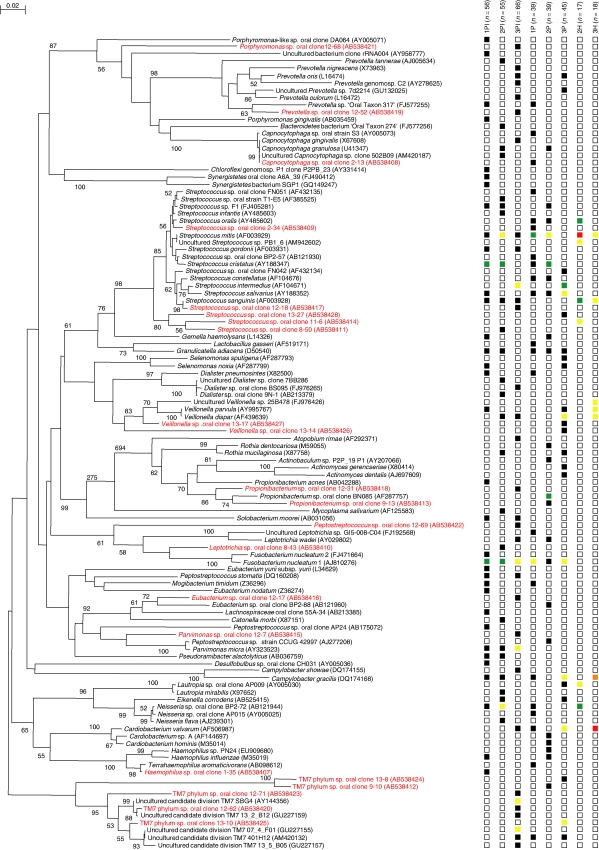

All sequences were checked for possible chimeric artifacts by the Chimera Check program of the Ribosomal Database Project-II (RDP-II) and compared to similar sequences of the reference organisms by BLAST search (30). A 16S rRNA gene sequence similarity of 98% was used as the cut-off for positive identification of taxa (operational taxonomic unit – OTU). Less than 98% identity in the 16S rRNA gene sequence was the criterion used to identify bacteria at the species level. The sequences were aligned with the Clustal X 2.0.12 program (31) and corrected by manual inspection. Nucleotide substitution rates (K nuc values) were calculated (32) after gaps and unknown bases were eliminated. The phylogenetic tree was constructed by the neighbor-joining method (33). Bootstrap resampling analysis (34) was performed to estimate the confidence of tree topologies. Sequences for novel phylotypes were deposited in the DDBJ database under accession numbers AB538407 to AB538428.

Libraries were analyzed using the Mothur program v.1.7.2 (35). Distance matrices were calculated using the Dnadist program within the PHYLIP software package version 3.69. The Shannon index was used to measure community diversity. The Chao1 index was applied to measure community richness.

Results

Clinical data of subjects and sites selected for bacterial sampling are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. A total of nine sites (three PI, three periodontitis, and three healthy implants) were selected and collected for subgingival plaque samples. One sample (periodontally healthy implant) was missed in the process of sample preparation, so eight samples were analyzed. A total of 335 sequences from eight samples were subjected to sequence analysis, which revealed 112 species; 51 (46%) were uncultivated phylotypes, of which 22 were novel. The total numbers of bacterial species identified at the sites of PI, periodontitis, and periodontally healthy implants were 77, 57, and 12, respectively. Each clone was classified into several clusters corresponding to phylum-level classification (Table 3, Fig. 1). Microbiota of PI primarily included Gram-negative species and the composition was more diverse than that for healthy implants or periodontitis. Chloroflexi, Tenericutes, and Synergistetes phyla were only detected at PI sites. Also Parvimonas micra, Peptostreptococcus stomatis, Pseudoramibacter alactolyticus, and Solobacterium moorei were only observed at PI sites. Fusobacterium nucleatum was identified at all of the PI sites and Granulicatella adiacens was identified at two thirds of PI sites; these two species were also detected at periodontitis sites but not at healthy implants. Most of the bacterial species found in the healthy implants were also detected in the PI and periodontitis sites.

Table 1.

Clinical data of the subjects

| Subject | A | B | C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 60 | 60 | 60 |

| Gender | Female | Female | Female |

| Smoking habit | Non | Non | Non |

| Mean of all teeth PD (mm)a | 2.7±0.76 | 2.2±0.42 | 2.5±1.27 |

| Residual teeth | 21 | 20 | 13 |

| Residual implants | 2 | 6 | 8 |

Mean±SD.

Table 2.

Clinical information of sampling sites

| Subject A | Subject B | Subject C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | PI | P | PI | P | PI | P |

| Site | 37 | 44 | 16 | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| PD (mm) | 5 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 5 | 4 |

| BOP or SUP | + | + | + | + | + | + |

| GI | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Time of implant load (year) | 10 | 7 | 3 | |||

| Implant surface | Rough | Machine | Rough | |||

Table 3.

Bacterial phyla and genera detected in this study

| Actinobacteria | Proteobacteria | TM7 |

| Actinobaculum | Campylobacter | TM7 |

| Actinomyces | Cardiobacterium | |

| Atopobium | Desulfobulbus | Tenericutes |

| Propionibacterium | Eikenella | Mycoplasma |

| Rothia | Hemophilus | |

| Lautropia | Synergistetes | |

| Firmicutes | Neisseria | Synergistes |

| Catonella | Terrahaemophilus | |

| Dialister | ||

| Eubacterium | Bacteroidetes | |

| Gemella | Bacteroidetes | |

| Granulicatella | Capnocytophaga | |

| Lachnospiraceae | Porphyromonas | |

| Lactobacillus | Prevotella | |

| Mogibacterium | ||

| Parvimonas | Chloroflexi | |

| Peptostreptococcs | Chloroflexi | |

| Pseudoramibacter | ||

| Selenomonas | Fusobacteria | |

| Solobacterium | Fusobacterium | |

| Streptococcus | Leptotrichia | |

| Veillonella |

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of bacterial species and phylotypes detected in peri-implantitis (PI), periodontitis (P), and healthy implants (H). Novel phylotypes identified in this study are indicated in red letters. The scale bar represents 0.02 substitutions per nucleotide. Accession numbers for 16S rRNA gene sequences are given for each strain. Right columns 1PI, 2PI, 3PI, 1P, 2P, 3P, 2H, and 3H represent subject, sample, and the numbers of bacterial species identified at each site (see text). Boxes used to indicate abundance levels, based on total number of clones assayed: not detected (blank box), 1–5% (black), 6–10% (yellow), 11–20% (green), 21–40% (orange), and ≥40% (red).

When the diversity and richness of the resident bacterial species were compared between PI and periodontitis, higher values for the Shannon index and richness were observed at PI sites (Table 4), thus suggesting that the bacterial community at PI sites were more diverse when compared to periodontitis.

Table 4.

Comparison of diversity and richness of sequenced clones between peri-implantitis and periodontitisa

| Sample source | No. of sequences | No. of OTUsb | Shannon index | Richnessc | Coverage (%)d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peri-implantitis | 177 | 77 | 3.8 (3.7–4.0) | 161 (110–278) | 75.7 |

| Periodontitis | 123 | 57 | 3.7 (3.5–3.8) | 78 (61–124) | 79.7 |

Shannon index and richness are estimated based on 2% differences in nucleic acid sequence alignments. Values given in parentheses are 95% confidence intervals, as calculated by the Mothur program.

OTU – operational taxonomic unit.

Chao1 values, a non-parametric estimate of species richness.

Coverage values for a distance of 0.02, as calculated by the Mothur program.

Discussion

In the present study, we identified the bacteria that compose biofilm at sites with PI. It is believed that the source of infecting bacteria on implants is mainly plaque from residual teeth or saliva, and that microbiota around the implants tend to be similar to that of residual teeth (36–38). The periodontal status of remaining teeth would thus determine the bacterial composition at PI sites (37, 38). Our results show that some Streptococcus spp. and F. nucleatum are common to sites with periodontitis and PI. Sites with PI tend to show a more complex microbiota when compared to periodontitis/healthy implant sites and Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria are particularly common at such sites.

The presence of periodontopathic bacteria is generally considered to be a risk factor for PI, and indeed, many studies have reported the high prevalence of bacteria, such as P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans in PI lesions (15–20). In contrast, several researchers have argued that PI and/or implant failure does not always harbor periodontopathic bacteria (39–41). F. nucleatum is reported to be a pathogen involved in periodontitis and was found at all PI sites in the present study. However, we were unable to confirm the high prevalence of other periodontopathic bacteria in peri-implant/periodontal lesions. It should be emphasized that the sample size was limited and our results do not rule out an association between ‘established’ periodontopathic bacteria and PI. Although numerous species reside in peri-implant lesions when compared to periodontitis sites, potentially important bacteria may have been overlooked as disease pathogens. To our knowledge, this is the first study using the 16S rRNA gene clone library technique to analyze the microbiota in PI, to confirm that the biofilm of PI is composed of a greater variety of bacterial species when compared to periodontitis. Bacteria isolated only in PI, such as P. micra, P. stomatis, and P. alactolyticus, have been reported to be present in periodontal and/or endodontal lesions (42, 43). Because most of these bacteria are difficult to grow in culture, they have not yet been characterized by their bacterial properties. Also the Chloroflexi, Tenericutes, and Synergistetes phyla were only detected at PI sites. This is in contrast to Vartoukian et al. (44) who reported a high prevalence of the phylum ‘Synergistetes’ in both periodontitis and healthy subjects. We considered that the discrepancy of the results was mainly derived from the bacterial sampling method; they used pooled plaque samples taken by curette from four periodontal pockets. Since the number of subjects attended in the studies was small (Vartoukian; 10, ours; 3), further studies are necessary for clarifying the role of the phylum Synergistetes in peri-implant diseases, moreover for other bacteria.

Differences in bacterial diversity between PI and periodontitis lesions may be explained by the characteristics of surfaces to which the bacteria adhere. Surface roughness and free energy (wettability) are thought to have a significant impact on biofilm formation (45) and the higher levels of free energy on the implant surfaces are likely to affect biofilm components.

In conclusion, PI biofilms showed a more complex microbiota when compared to periodontitis and periodontally healthy implants, and were mainly composed of Gram-negative anaerobic bacteria. Previously established periodontopathic bacteria showed low prevalence and several bacteria were identified as candidate of pathogens in PI, although it is unclear whether the importance of these species is higher when compared to established periodontopathic bacteria.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (No. 21792110, 21390553) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan. This study was supported by Graduate School of Medical and Dental Sciences, Tokyo Medical and Dental University, Tokyo, Japan and Microbe Division/Japan Collection of Microorganisms, RIKEN BioResource Center, Wako, Saitama, Japan.

Conflict of interest and funding

There is no conflict of interest in the present study for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Albrektsson T, Zarb GA, Worthington P, Ericsson AR. The long term efficacy of currently used dental implants: a review and proposed criteria for success. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1986;1:11–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zarb GA, Schmitt A. The longitudinal clinical effectiveness of osseointegrated dental implants: the Toronto study. Part II: the prosthetic results. J Prosthet Dent. 1990;64:53–61. doi: 10.1016/0022-3913(90)90153-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mombelli A, Lang NP. The diagnosis and treatment of peri-implantitis. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17:63–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hultin M, Gustafsson A, Hallström H, Johansson L-Å, Ekfeldt A, Klinge B. Microbiological findings and host response in patients with peri-implantitis. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:349–58. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130402.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Quirynen M, De Soete M, van Steenberghe D. Infectious risks for oral implants: a review of the literature. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:1–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roos-Jansåker AM, Renvert S, Egelberg J. Treatment of peri-implant infections: a literature review. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;30:467–85. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2003.00296.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roos-Jansåker AM, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year follow up of implant treatment: I. Implant loss and associations to various factors. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;22:283–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00907.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Roos-Jansåker AM, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Renvert S. Nine- to fourteen-year followup of implant treatment: II. Presence of periimplant lesions. J Clin Periodontol. 2006;22:290–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2006.00906.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindhe J, Berglundh T, Ericsson I, Liljenberg B, Marinello C. Experimental breakdown of peri-implant and periodontal tissues. A study in the beagle dog. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1992;1:9–16. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1992.030102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pontoriero R, Tonelli MP, Carnevale G, Mombelli A, Nyman SR, Lang NP. Experimentally induced peri-implant mucositis. A clinical study in humans. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1994;4:254–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1994.050409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito M, Hirch JM, Lekholm U, Thomsen P. Biological factors contributing to failures of osseointegrated oral implants (II). Etiopathogenesis. Eur J Oral Sci. 1998;106:721–64. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836..t01-6-.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tonetti MS. Risk factors for osseodisintegration. Periodontol 2000. 1998;17:55–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0757.1998.tb00123.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berglundh T, Persson L, Klinge B. A systematic review of the incidence of biological and technical complications in implant dentistry reported in prospective longitudinal studies of at least 5 years. J Clin Periodontol. 2002;3:197–212. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.29.s3.12.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Winkelhoff AJ, Goené RJ, Benschop C, Folmer T. Early colonization of dental implants by putative periodontal pathogens in partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2000;11:511–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2000.011006511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mombelli A, van Osten MA, Schurch E, Jr, Lang NP. The microbiota associated with successful or failing osseointegrated titanium implants. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;4:145–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Augthun M, Conrads G. Microbial findings of deep peri-implant bone defects. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1997;1:106–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leonhardt Å, Renvert S, Dahlén G. Microbial findings at failing implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1999;5:339–45. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1999.100501.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leonhardt Å, Dahlén G, Renvert S. Five-year clinical, microbiological, and radiological outcome following treatment of peri-implantitis in man. J Periodontol. 2003;10:1415–22. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.10.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Botero JE, Gonzalez AM, Mercado RA, Olave G, Contreras A. Subgingival microbiota in peri-implant mucosa lesions and adjacent teeth in partially edentulous patients. J Periodontol. 2005;9:1490–5. doi: 10.1902/jop.2005.76.9.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shibli JA, Melo L, Sanchez F, Figueiredo LC, Faveri M, Feres M. Composition of supra and subgingival biofilms of subjects with healthy and diseased implants. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:975–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01566.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Socransky SS, Smith C, Martin L, Paster BJ, Dewhirst FE, Levin AE. Checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization. Biotechniques. 1994;17:788–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Smith C, Martin L, Haffajee JA, Goodson JM. Use of checkerboard DNA–DNA hybridization to study complex microbial ecosystems. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2004;19:352–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.2004.00168.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Renvert S, Roos-Jansåker AM, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Persson RG. Infection at titanium implants with or without a clinical diagnosis of inflammation. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2007;18:509–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renvert S, Lindahl C, Renvert H, Persson RG. Clinical and microbiological analysis of subjects treated with Brånemark or AstraTech implants: a 7-year follow-up study. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2008;19:342–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2007.01476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maximo BM, Mendonca CA, Santos RV, Figueiredo CL, Feres M, Duarte MP. Short-term clinical and microbiological evaluations of peri-implant diseases before and after mechanical anti-infective therapies. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2009;20:99–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2008.01618.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Aas JA, Paster BJ, Stokes LN, Olsen I, Dewhirst FE. Defining the normal bacterial flora of the oral cavity. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5721–32. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.11.5721-5732.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loe H, Silness J. Periodontal disease in pregnancy. I. Prevalence and severity. Acta Odontol Scand. 1963;21:533–51. doi: 10.3109/00016356309011240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sakamoto M, Umeda M, Ishikawa I, Benno Y. Comparison of the oral bacterial flora in saliva from a healthy subject and two periodontitis patients by sequence analysis of 16S rDNA libraries. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:643–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sakamoto M, Rôças IN, Siqueira JF, Jr, Benno Y. Molecular analysis of bacteria in asymptomatic and symptomatic endodontic infections. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:112–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2006.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–10. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Larkin MA, Blackshields G, Brown NP, Chenna R, McGettigan PA, McWilliam H, et al. Clustal W and Clustal X version 2.0. Bioinformatics. 2007;23:2947–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rate of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–20. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–25. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felsenstein J. Confidence limits of phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution. 1985;39:783–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01541-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Papaioannou W, Quirynen M, van Steenberghe D. The influence of periodontitis on the subgingival flora around implants in partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1996;4:405–9. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1996.070415.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quirynen M, De Soete M, Dierickx K, van Steenberghe D. The intra-oral translocation of periodontopathogens jeopardises the outcome of periodontal therapy. A review of the literature. J Clin Periodontol. 2001;6:499–507. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.2001.028006499.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Quirynen M, Vogels R, Peeters W, van Steenberghe D, Naert I, Haffajee A. Dynamics of initial subgingival colonization of ‘pristine’ peri-implant pockets. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2006;17:25–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leonhardt Å, Adolfsson B, Lekholm U, Wikström M, Dahlén G. A longitudinal microbiological study on osseointegrated titanium implants in partially edentulous patients. Clin Oral Implants Res. 1993;4:113–20. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.1993.040301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leonhardt Å, Gröndahl K, Bergström C, Lekholm U. Long-term follow-up of osseointegrated titanium implants using clinical, radiographic and microbiological parameters. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2002;13:127–32. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0501.2002.130202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sbordone L, Barone A, Ciaglia RN, Ramaglia L, Lacono VJ. Longitudinal study of dental implants in a periodontally compromised population. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1322–9. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.11.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahlén G, Leonhardt Å. A new checkerboard panel for testing bacterial markers in periodontal disease. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 2006;21:6–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302X.2005.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Colombo AP, Boches SK, Cotton SL, Goodson JM, Kent R, Haffajee AD, et al. Comparisons of subgingival microbial profiles of refractory periodontitis, severe periodontitis, and periodontal health using the human oral microbe identification microarray. J Periodontol. 2009;80:1421–32. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.090185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vartoukian SR, Palmer RM, Wade WG. Diversity and morphology of members of the phylum “Synergistetes” in periodontal health and disease. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3777–86. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02763-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Subramani K, Jung RE, Molenberg A, Hammerle CH. Biofilm on dental implant: a review of the literature. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 2009;24:616–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]