Abstract

Angiogenesis, extracellular matrix remodeling and cell migration are associated with cancer progression and involve at least, the plasminogen activating system and its main physiological inhibitor, the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1). Considering the recognized importance of PAI-1 in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis and invasion in murine models of skin tumor transplantation, we explored the functional significance of PAI-1 during early stages of neoplastic progression in the transgenic mouse model of multistage epithelial carcinogenesis (K14-HPV16 mice). We have studied the effect of genetic deletion of PAI-1 on inflammation, angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, as well as tumor progression. In this model, PAI-1 deficiency neither impaired keratinocyte hyperproliferation or tumor development, nor affected the infiltration of inflammatory cells and development of angiogenic or lymphangiogenic vasculature. We are reporting evidence for concomitant lymphangiogenic and angiogenic switches independent to PAI-1 status. Taken together, these data indicate that PAI-1 is not rate limiting for neoplastic progression and vascularization during premalignant progression, or that there is a functional redundancy between PAI-1 and other tumor regulators, masking the effect of PAI-1 deficiency in this long-term model of multi-stage epithelial carcinogenesis.

Keywords: Plasminogen activator, angiogenesis, lymphangiogenesis, K14-HPV16

INTRODUCTION

The plasminogen activator system plays a crucial role in tumor initiation, growth, invasion, angiogenesis and metastasis formation 1. This proteolytic system is composed of the cellular receptor of urokinase (uPAR), the urokinase-type (uPA) and tissue-type plasminogen (tPA) activators and their specific inhibitor, the plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) 2–3. Consistent with their role in cancer progression, high levels of uPA, PAI-1 and uPAR correlate with adverse patient outcome 1. A large body of clinical data led to the statement that uPA and PAI-1 are among the first biological prognostic factors to have their clinical value validated 4. PAI-1 over-expressed in tumors 5 is preferentially localized in the stromal area 6–7. It is expressed by various cell types including endothelial cells 8, mast cells 9, fibroblasts 10 and myofibroblasts 11.

Beside regulating proteolytic cascades during tissue remodeling, PAI-1 also modulates cell adhesion by interfering with integrin, vitronectin and low density lipoprotein receptor related protein (LRP) 12–15. In addition, it regulates cell proliferation 16–17 and cell apoptosis 18. PAI-1 is thus a multifunctional protein displaying paradoxical functions during tumor progression 1-3-13.

The effect of PAI-1 on tumor biology has been explored by using transgenic mice deficient for PAI-1 or over-expressing PAI-1 1-14-19. This approach clearly underlined two distinct effects of PAI-1 on tumor angiogenesis. While high levels of PAI-1 inhibited angiogenesis, physiological levels of PAI-1 were required for in vitro 20 and in vivo angiogenesis 21–23. In addition, PAI-1 produced by host cells plays an important role in human carcinoma progression 24. These data derived from experimental tumor transplantation models in which tumor cells were transplanted into syngeneic mice genetically modified to overproduce or be deficient in PAI-1 expression are not consistent with the observations made with de novo carcinogenesis models. Indeed, PAI-1 deficiency did not affect cancer progression in a transgenic mouse model of mammary carcinogenesis, the MMTV-PymT mice 25. In addition, we have recently reported that PAI-1 has no effect on primary ocular tumor growth, but reduces brain metastasis in TRP-1/SV40 transgenic mice 26. It is not clear whether PAI-1-induced tumor angiogenesis represents a direct intrinsic response to invasive cancer cells or an early response to inflammatory assault that induces the angiogenic switch and subsequent malignant conversion. It has become evident that early and persistent inflammatory responses observed in or around developing neoplasms influence tumor progression 27. Several studies have shown the production of PAI-1 by immune cells such as macrophages and mast cells 9–28. In addition, PAI-1 inhibits the phagocytosis of apoptotic neutrophils (efferocytosis) and potentiates neutrophil activation 29–30. Although the implication of PAI-1 in inflammation is clear, the putative contribution of PAI-1 in tumor-associated inflammation is not fully understood.

With the aim at evaluating the contribution of PAI-1 during the premalignant stages of carcinoma development, we used a well established transgenic mouse model of de novo epithelial squamous cell carcinogenesis 31. In this model, expression of early region genes (E6 and E7) of the human papillomavirus type 16 in basal keratinocytes driven by keratin 14 promoter/enhancer induces epithelial carcinogenesis through well-defined premalignant stages before de novo carcinoma development (e.g. K14-HPV16 mice). K14-HPV16 mice develop hyperplastic skin lesions with 100% penetrance by 1 month of age that focally progress to dysplasia by 3 to 6 months 31. Dysplastic tissues undergo malignant conversion into squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) in skin of 50% of mice (FVB/n, N25), 30% of which metastasize into draining lymph nodes 31–32. This model has called attention to the involvement of proteases produced by mast cells 33 and other bone marrow-derived cells (neutrophils and macrophage) in the development of angiogenic vasculature and tumor development 34-34-35. In the current study, we have examined the functional significance of PAI-1 in tumor-associated inflammation, development of angiogenic and lymphangiogenic vessels occurring during the course of carcinoma development. Our data indicate that PAI-1 independent pathways are critical for the onset and maintenance of chronic inflammation, angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis during the early stages of epithelial carcinogenesis.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Transgenic mice

Generation and characterization of K14-HPV16 transgenic mice on the FVB/n genetic background has been described previously 31–36. To generate K14-HPV16 PAI-1−/− and PAI-1+/+ mice, homozygous PAI-1 deficient mice and the corresponding WT mice were backcrossed with K14-HPV16 FVB/n transgenic mice for a minimum of 9 generations. K14-HPV16 PAI-1−/− and PAI-1+/+ mice with a mixed genetic background of 3.1% C57BL/6 and 96.9% FVB/n were used. Mouse experimentation was done in accordance to the guideline of the University of Liege regarding the care and use of laboratory. Transgenic mice were sacrificed at different ages: 1 month (n=10), 4 months (n=22) and 6 months (n=28). The presence of the PAI-1 allele was assessed by PCR genotyping of tail DNA using oligonucleotide primers discriminating between the WT allele (5′-CTAGAGCTGGTCCAGGGCTTCAT −3′ and 5- CAGGCGTGTCAGCTCGTCTACA −3′) when DNA was successively amplified for 35 cycles at 95°C 2 minutes, 94°C 30 seconds, 60°C 30 seconds, and 72°C 30 seconds.

Histopathological analysis and immunohistochemistry

Age-matched ear tissues removed from transgenic and control animals were either embedded in Tissue-Tek (O.C.T.™, Sakura, Zoeterwoude, NL), frozen at −80°C or fixed in buffered 1% formalin followed by dehydration through graded alcohols and xylen, and then embedded in paraffin. Sections (5-μm) were stained with hematoxylin/eosin for histopathological analysis. For immunohistochemistry, sections were treated by autoclave or trypsin to ensure epitope exposition and incubated 30 minutes at room temperature with H2O2 3% (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) to block endogenous peroxydases. After brief H2O wash, a blocking reagent was applied, followed up by the incubation of the primary antibodies. Antibodies raised against CD45 (rat anti-mouse CD45/biotin, diluted 1/1500, Pharmingen, San Diego, USA); Ki-67 (rat anti-mouse, diluted 1/50, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark); Lyve-1 (rabbit polyclonal Ab, diluted 1/1000, Bioconnect, Huissen, Netherlands) were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were washed in phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and then appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated to peroxydase or biotin for 30 minutes were added: rabbit anti-rat/biotin (diluted 1/300, DAKO) goat anti-rabbit/biotin (diluted 1/400, DAKO), rabbit anti-guinea pig/HRP (diluted 1/50, DAKO). After washes in PBS, the antibody-antigen complex was visualized by treatment with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB, DAKO, Glostrup, Denmark). Samples were counterstained with hematoxylin/eosin, washed in H2O, dehydrated in graded alcohols and mounted with EUKITT (Kindler GmbH, Ziegelhofstrasse, Freiburg).

For double staining, tissue sections were incubated with two primary antibodies: Von willebrand factor (rabbit polyclonal, diluted 1/500, DAKO) and alpha smooth muscle actin (α-SMA, mouse polyclonal, diluted 1/500, Sigma, Steinheim, Germany). Washings were performed with Tris/HCL buffer (Tris/HCl 1X: 6.0 g Tris; 9 gr NaCl; 3.3 ml HCL; 1.0 L H2O; pH 7.6). The α-SMA staining was visualized by Fast blue prepared by mixing Fast blue (1mg) (Sigma-Aldrich Steinheim, Germany) with 5 dips of levamisole (DAKO) in appropriate buffer (Naphtol-AS-MX-phosphate 20 mg; N,N-dimethylformamide 2 ml; Tris/HCL 98 ml). Slides were mounted with Aquapolymont (polysciences, inc, Warrington).

Enzyme histochemistry

Mast cells were visualized by chloroacetate esterase (CAE) histochemistry and toluidin blue coloration. CAE histochemistry was performed to reveal the presence of the chymotrypsin-like serine esterase activity of mast cells as previously described 33. Briefly, slides were deparaffinized and rehydrated in H2O. Then, 3.0 mg of Naphtol AS-D chloroacetate (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was dissolved in 60 μl of demethylformamide and 3.0 ml of buffer (8% demethylformamide, 20% Ethylene glycol monoethyl ether, in 80 nM Tris-maleate pH 7.5). Fast Blue BB (3mg) (Sigma-Aldrich, Steinheim, Germany) was added and applied on sections for 5 minutes. Slides were washed in PBS, dehydrated and mounted in glycerol.

Toluidin blue coloration was used to stain mast cell granules. Sections were deparaffinized and rehydrated in H2O. Slides were incubated for 30 minutes in toluidin blue 0,5% (0.5 g in HCL buffer: 948 ml H2O, 13.8 g dihydrogenophosophate de Na monohydrate, 42 HCL, pH 0.5). Sections were washed for 15 minutes in water and incubated 2 minutes in nuclear red (5 g ammonium sulfate in 100 ml H2O, 0.1 g Kernechtrat). After two washings in 2-propanol and one in xylen for 2 minutes, slides were mounted with EUKITT (Kindler GmbH, Ziegelhofstrasse, Freiburg).

Reverse Transcriptase-PCR analysis

RT-PCR amplification was carried out with the GeneAmp Thermostable rTth reverse transcriptase RNA PCR kit (Perkin Elmer Life Sciences, Boston, MA) with specific pairs of primers (Table I). RT-PCR products were resolved by electrophoresis in 10% polyacrylamide gels and analyzed with a Fluor-S MultiImager after staining with Gelstar dye (FMC BioProducts, Heidelberg, Germany). RT-PCR products were quantified by normalization with respect to 28S rRNA.

Table 1.

Sequences of primers used for RT-PCR studies.

| Forward primer (5′→3′) | Reverse primer (5′→3′) | Cycles (n) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MMP-2 | 5′-AGATCTTCTTCTTCAAGGACCGGTT-3′ | 5′-GGCTGGTCAGTGGCTTGGGGTA-3′ | 27 |

| MMP-9 | 5′-GCGGAGATTGGGAACCAGCTGTA-3′ | 5′-GACGCGCCTGTGTACACCCACA-3′ | 35 |

| MMP-13 | 5′-ATGATCTTTAAAGACAGATTCTTCTGG-3′ | 5′-TGGGATAACCTTCCAGAATGTCATAA-3′ | 33 |

| TIMP-1 | 5′-CATCCTGTTGTTGCTGTGGCTGAT-3′ | 5′-GTCATCTTGATCTCATAACGCTGG-3′ | 30 |

| TIMP-2 | 5′-CTCGCTGGACGTTGGAGGAAAGAA-3′ | 5′-AGCCCATCTGGTACCTGTGGTTCA-3′ | 25 |

| TIMP-3 | 5′-CTTCTGCAACTCCGACATCGTGAT-3′ | 5′-CAGCAGGTACTGGTACTTGTTGAC-3′ | 27 |

| uPA | 5′-ACTACTACGGCTCTGAAGTCACCA-3′ | 5′-GAAGTGTGAGACTCTCGTGTAGAC-3′ | 30 |

| tPA | 5′-CTACAGAGCGACCTGCAGAGAT-3′ | 5′-AATACAGGGCCTGCTGACACGT-3′ | 27 |

| uPAR | 5′-ACTACCGTGCTTCGGGAATG-3′ | 5′-ACGGTCTCTGTCAGGCTGATG-3′ | 30 |

| PAI-1 | 5′-CTAGAGCTGGTCCAGGGCTTCAT −3′ | 5′-CAGGCGTGTCAGCTCGTCTACA −3′ | 30 |

| PAI-2 | 5′-CTCAAACCAAAGGTGAAATCCCAA-3′ | 5′-GGTATGCTCTCATGCGAGTTCACA-3′ | 30 |

| Maspin | 5′-CACAGATGGCCACTTTGAGGACAT-3′ | 5′-GGGAGCACAATGAGCATACTCAGA-3′ | 27 |

| PN-1 | 5′-GGTCCTACCCAAGTTCACAGCTGT-3′ | 5′-AGGATTGCAGTTGTTGCTGCCGAA-3′ | 27 |

| VEGF-A | 5′-CCTGGTGGACATCTTCCAGGAGTA-3′ | 5′-CTCACCGCCTCGGCTTGTCACA-3′ | 33 |

| FGF-1 | 5′-GGCTGAAGGGGAGATCACAACCTT-3′ | 5′-CATTTGGTGTCTGCGAGCCGTATA-3′ | 29 |

| 28s | 5′-GTTCACCCACTAATAGGGAACGTGA-3′ | 5′-GATTCTGACTTAGAGGCGTTCAGT-3′ | 15 |

Quantification and statistical analysis

For each time point, quantitative analysis of all stained cells was performed by counting cells in 5 high-power fields (40X) (except of LYVE-1 positive cells for which (20X) high-power fields were used) per tissue section generated from 5 mice per neoplastic stage. Data presented reflect the average total count (cells or lymphatic vessels) per field from ventral ear leaflet. Proliferative index is defined as the proportion of tumor cells stained positively for Ki-67 from all epidermal cells. Quantitative analysis of the angiogenic response was performed by measuring the distance separating the epithelial basement membrane (dBM) to the 5 closest blood vessels. Five measures were realized on fields (40X) per mice (n=5 per neoplastic stage). To avoid problems of cutting artifact, each value was normalized to the thickness of the dermis (de). Results are expressed as the mean of the ratio dBM/de. Statistical differences between experimental groups were assessed by using Mann-Whitney with GraphPad Prism 4.0 (San Diego, Ca, USA.). Statistical significance was set as P<0,05.

Quantification assisted by computer

Micrographs of tissue section were digitized in the RGB space from optical microscope images captured at 5X magnification. In this representation, the lymphatic vessels stained as described above, appeared in the red colour. In order to quantify lymphangiogenesis, RGB images where decomposed into their red (R), green (G) and bleu (B) components and the red component images were thresholded using a non-parametric method. After this transformation, binary images were obtained in which vessels were represented by white pixels (intensity equal to 1) and the background by black pixels (intensity equal to 0). On these binary images, different parameters were evaluated: (1) the mean surface of vessels, (2) the number of vessels par unit of tissue area, and (3) the percent of tissue occupied by vessels (area density of vessels).

RESULTS

PAI-1 deficiency does not affect the characteristic parameters of premalignant carcinogenesis in K14-HPV16 mice

Previous studies using K14-HPV16 mice revealed an important role for the angiogenic switch during skin carcinoma progression 33. Given the critical role of the plasminogen activator plasmin system in the regulation of tumor angiogenesis as well as in the recruitment and activation of immune cells during pathologic tissue remodeling, we hypothesized that PAI-1 contributes to the recruitment of leukocytes toward neoplastic skin that fosters tumorigenicity. We tested this hypothesis through a genetic approach by generating a cohort of 30 K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and a cohort of 30 K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ and we examined several features of angiogenesis/lymphangiogenesis and premalignant progression in the absence and presence of PAI-1.

Early neoplastic progression in K14-HPV16 mice is characterized by hyperplastic lesions identified by a two-fold increase in epidermal thickness and an intact granular cell layer with keratohyalin granules. By 4–6 months of age, dysplastic lesions are identified by the prominent hyperproliferative epidermis that fails to undergo terminal differentiation of keratinocytes. Dysplastic lesions reflect precursor sites that for emergence of invasive squamous cell carcinomas (SCC) that include malignant keratinocytes containing abnormal mitotic figures and the loss of basement membrane integrity with clear development of malignant cell clusters proliferating into the dermal stroma. Histopathologically, K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ mice were indistinguishable from K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice. With 100% penetrance, HV16 mice of both genotypes developed hyperplastic skin lesions by 1 month of age followed by the development of dysplasias by 4 to 6 months of age. The latency and the incidence of the lesions observed in ear skin were independent of PAI-1 status. In both genotypes, we detected 100% of hyperplastic lesions by one month of age (n = 10) and 100% of dysplastic lesions at 4 months (n=22) and at 6 months (n=28) of age

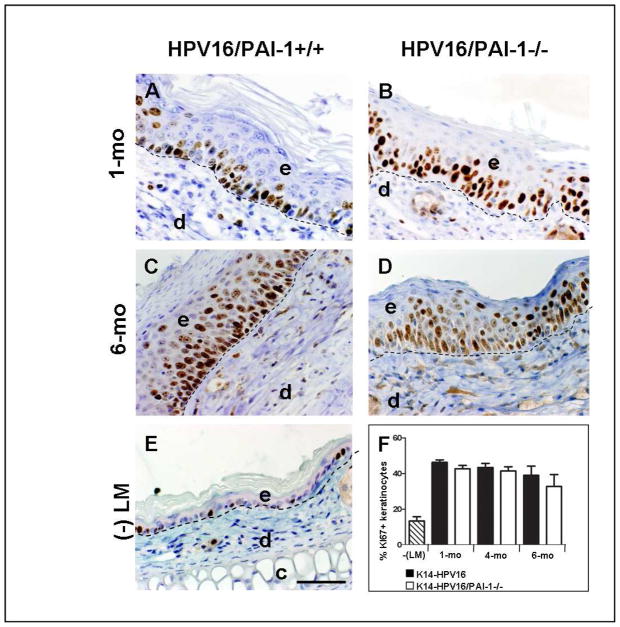

As an intrinsic property of many neoplastic cell types, keratinocyte hyperproliferation is a characteristic of neoplastic progression in K14-HPV16 mice 33-36-37. Keratinocyte proliferative indices were determined by Ki67 staining in age-matched skin from K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice and were found to be similar in each neoplastic stages examined (Figure 1, P>0.1). Altogether, these observations suggest that PAI-1 is not involved in the control of epithelial hyperproliferation and in early stages of premalignant progression.

Figure 1. Keratinocyte proliferation is not affected in the absence of PAI-1.

A–E: Immunohistochemical detection of Ki-67 positive cells on tissue sections of ears issued from K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ (A and C) and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− (B and D) mice with hyperplastic (A and B) and dysplastic (C and D) lesions; and on section of ears from negative littermate (-LM) (E). F: Quantitative analysis of the percentage of Ki-67-positive keratinocytes in K14-HPV16 and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice at 1, 4 and 6 months of age. Values represent keratinocyte proliferation which was determined as the percentage of Ki-67 positive keratinocytes as a fraction of total keratinocytes averaged from five high-power fields per mouse (n=5). Error bars represent SEM. No statistically significant difference was observed between age-matched neoplastic tissue issued from K14-HPV16 and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− (1 month P = 0.1143; 4 months P = 1; 6 months P = 0.62; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test). Dashed line indicates epidermal-dermal interface. The epidermis (e), dermis (d), and cartilage (c) are indicated. Original magnification: 400x. Bars, 50μm.

PAI-1 deficiency does not affect the (lymph)angiogenic switch in K14-HPV16 mice

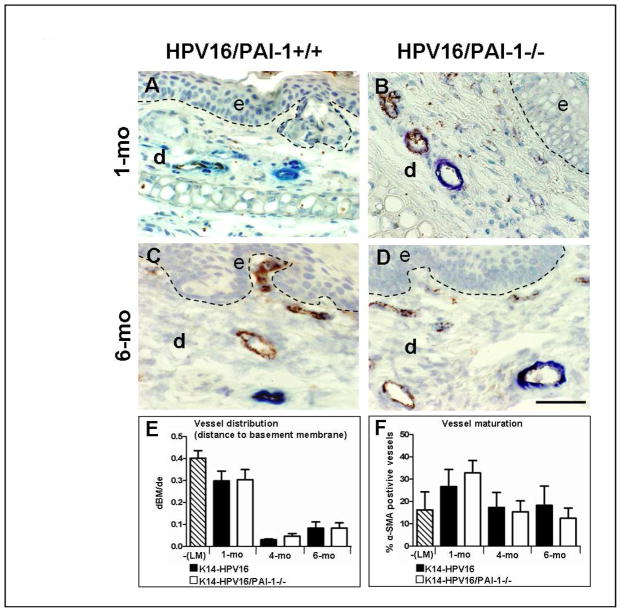

In K14-HPV16 mice, changes in vascular architecture reflect the phenotypic switch to angiogenesis. Normal non transgenic mouse skin contains infrequent capillaries located deep into the dermis (Figure 2). Hyperplastic lesions showed a modest increase in capillary density that remains distal to the neoplastic epidermis. An increase of dilated and enlarged capillaries closed to the epithelial basement membrane characterizes dysplastic lesions 33-36-37. The distance separating epithelial basement membrane to the closest vessels was about 3 times lower at 4 and 6 months than at 1 month (Figure 2E, P< 0.0159). These features are indicative of an angiogenic switch from a vascular quiescence to the initiation of a neo-vascularization in early low grade lesions (hyperplasias).

Figure 2. Tumor vascularization is not affected by PAI-1 deficiency.

A–D: Immunocolocalization of von Willebrand factor (endothelial cells in brown) and alpha-smooth muscle actin (pericytes in blue) in paraffin-embedded sections of age-matched neoplastic ear tissue of K14-HPV16 (A and C) and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice (B and D). E: Quantitative analysis of vessel distribution at distinct stages of neoplastic progression in ear tissue from K14-HPV16, K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and negative littermate (-LM). Values represent the average ratio between “dBM” and “de”. “dBM” corresponds to the distance separating epithelial basement membrane and the 5 closest blood vessels. “de” is the thickness of dermis. Errors bars represent SEM (1 month P = 0;8857; 4 months P = 0;547; 6 months P = 0.9166; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test). F: Quantitative analysis of vessel maturity at distinct stages of neoplastic progression in ear tissue from K14-HPV16, K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and negative littermate (-LM). Values represent the percentage of vessels covered by pericytes (% α-SMA positive vessels) evaluated on five high-power fields per mouse and five mice per category. Errors bars represent SEM. No statistically significant differences were observed between age-matched neoplastic tissues between K14-HPV16 and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− (1 month P = 0.3429; 4 months P = 0.8413; 6 months P = 0.3457; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test). Original magnification: 400x. Bars, 50μm.

To evaluate the impact of PAI-1 deficiency on tumor vascularization, a double staining for Von Willebrand factor and α-SMA was performed (Figure 2A–D). α-SMA identifies mature vessels by presence of alpha smooth muscle actin positive mural cells. A comparison of vascular architecture, vessel density and distribution (Figure 2E, P>0.5) during premalignant progression in K14-HPV16 and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice failed to reveal any differences between the two genotypes. There was also no difference in the percentage of mature vessels between PAI-1 proficient and deficient mice (Figure 2F, P>0.5).

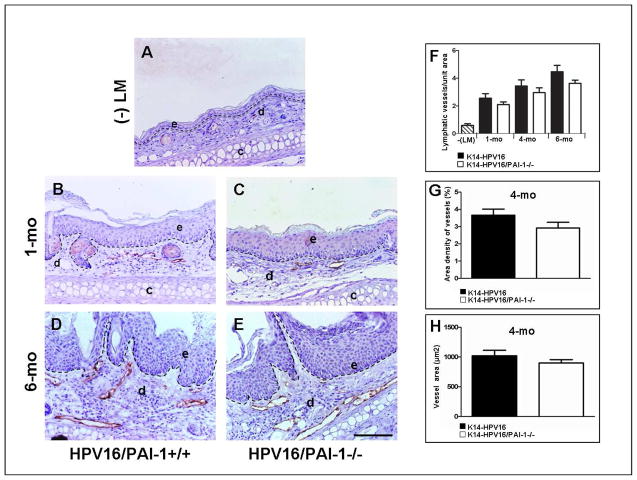

A “lymphangiogenic switch” in tumors might represent a mirror image of an angiogenic switch induced by an imbalance between lymphangiogenic factors and inhibitors in favour of activators 38–39. Lyve-1 staining was performed to identify lymphatic vessels and revealed dramatic changes in dermal lymphatic density and architecture associated with premalignant progression. Normal non transgenic mouse skin contained infrequent lymphatic vessels (Figure 3A). Hyperplastic lesions showed a modest increase in the density and dilatation of lymphatic vessels (Figure 3C). Dysplastic lesions contained dilated and enlarged vessels that were increased in number (Figure 3D). This vascular pattern is indicative of a lymphangiogenic switch and is in line with previous studies 40. Nevertheless, no significant difference in the number of lymph vessels was found between K14-HPV16 PAI-1−/− and K14-HPV16 PAI-1+/+ in age-matched mice at 1, 4 and 6 months (Figure 3F, P>0.3). To compare the area of dilated vessels present in dysplatic lesions between K14-HPV16 PAI-1−/− and K14-HPV16 PAI-1+/+, we performed a quantitative analysis on ear skin from mice at 4 months of age (Figure 3G and 3H, P>0.1). No difference was observed between the two genotypes.

Figure 3. The lymphangiogenic switch during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis is independent of PAI-1 status.

A–F: Immunohistochemical detection of lymphatic vessels by Lyve-1 staining in normal skin of negative littermate (-LM) (A); hyperplastic lesions (B, C), dysplastic lesions (D, E) of ear skin issued from K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ mice (B, D) and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− mice (C, E). F-H: Quantification of ear vascularization performed by determining the vessel density (number of vessels per area) (1 month P = 0.5386; 4 months P = 0.3321; 6 months P = 0.2530; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test) (F); the area density of vessels (percentage of tissue occupied by lymphatic vessels) (P = 0;1508; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test) (G) and the mean surface of lymphatic vessels (P = 0.4206; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test) (H). In all quantifications, values represent average values from five high-power fields per mouse and five mice per group. Errors bars represent SEM. Original magnification: 200x. Bars, 100μm.

Altogether, these data indicate that PAI-1 deficiency does not influence either the angiogenic switch or the lymphangiogenic switch observed early in premalignant skin of K14-HPV16 mice.

PAI-1 deficiency does not affect the infiltration of inflammatory cells in K14-HPV16 mice

The K14-HPV16 transgenic model is characterized by an increased infiltration of CD45 positive immune cells in the successive neoplastic stages. In the opposite to hyperplasia, dysplastic lesions are infiltrated by mast cells, macrophages and neutrophils close to dilated and enlarged angiogenic vasculature 33-37-41. We profiled the infiltration of leukocytes and mast cells in neoplastic tissue from K14-HPV16 PAI-1−/− and K14-HPV16 PAI-1+/+ mice aged of 1, 4 and 6 months by immunohistochemistry. Visual detection of leukocytes performed by CD45 staining did not reveal differences in leukocyte infiltration between the two genotypes (data not shown).

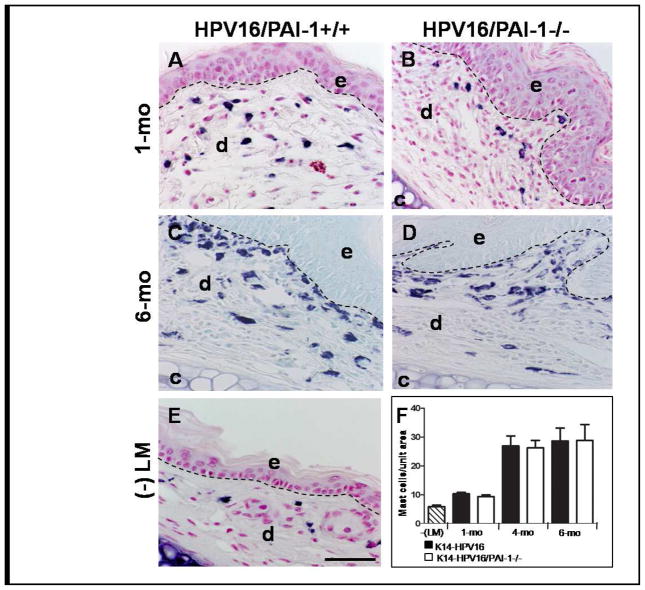

Through toluidin blue coloration, we detected mast cells in tissue. In accordance with previous observations, mast cell numbers increased progressively in the dermal connective tissue at the hyperplastic (1-month old) and dysplastic (4–6 months old) stages (Figure 4F). However, the number of mast cells infiltrating the lesions was similar in mice irrespective of their PAI-1 status (Figure 4, P>0.3). We confirmed these results by chloroacetate esterase (CAE) histochemistry which detects serine esterase activity in mast cells (data not shown). The lack of difference in immune cell infiltration between the two genotypes indicates that this process is not influenced by PAI-1 status.

Figure 4. The infiltration of neoplastic skin by mast cells is not affected by PAI-1-deficiency.

A–E: Detection of mast cell infiltration by toluidin blue coloration on hyperplastic ear skin (A and B), in dysplastic ear skin (C and D) from K14-HPV16 (A and C) and K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− (B and D) and in normal ear skin (E). F: Quantitative analysis of mast cells at distinct stages of neoplastic progression in ear tissue from K14-HPV16, K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and negative littermate (-LM). Values represent the number of mast cells averaged from five high-power fields per mouse and five mice per experimental group. Error bars represent SEM (1 month P = 0.3314; 4 months P = 0.9166; 6 months P = 0.92; Mann-Whitney unpaired t-test). Original magnification: 400x. Bars, 50μm.

PAI-1 deficiency is not compensated by the overexpression of the main related proteases or inhibitors

In order to address the possibility that other components of related proteolytic systems might compensate for the absence of PAI-1, we performed mRNA expression analysis by semi-quantitative RT-PCR of the genes encoding several protease related candidates (Table I). The molecules studied included components of the plasminogen/plasmin system (tPA, uPA, uPAR, PAI-1, PAI-2, PN-1 and MASPIN), several members of metalloproteinase family putatively involved in angiogenesis (MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-13) and angiogenic factors (FGF-1 and VEGF-A). This expression profiling was performed on premalignant ear skin tissues resected after 1, 4 and 6 months. At all time points, no significant differences were found in the mRNA levels of these factors in ears issued from K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ mice (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we examined the functional significance of PAI-1 in a mouse model of epithelial carcinogenesis characterized by a prominent immune cell infiltration, activation of angiogenic vasculature and keratinocyte hyperproliferation in premalignant lesions. By crossing a PAI-1-null allele into the K14-HPV16 model, we generated a cohort of mice in which we compared neoplastic progression, angiogenesis, vessel maturity and leukocyte recruitment. In addition, we extended our exploration to lymphangiogenesis in K14-HPV16 transgenic mice deficient for PAI. The analysis of mice aged from 1, 4 and 6 months revealed that K14-HPV16/PAI-1−/− and K14-HPV16/PAI-1+/+ were indistinguishable histopathologically.

Our results confirm the occurrence of a lymphangiogenic switch occurring during the course of carcinogenesis. This is in line with the previous study showing a proliferation of lymphatic endothelial cells during the early stages of neoplastic progression 42. Large and dilated lymphatic vessels appeared associated with the epithelia of dysplasic lesions. The exact mechanisms by which tumor cells recruit and invade lymphatic vessels are still unknown. Since vascular remodeling associated with lymphangiogenesis and angiogenesis seems to involve a similar process 43, we hypothesized that PAI-1 could influence the lymphangiogenic reaction occurring in this multistage carcinogenesis model. However, the lack of PAI-1 did not affect either the lymphatic vessel density or lymphatic vessel architecture. This observation is in line with our previous study showing that PAI-1 deficiency or a pharmacological inhibitor of serine proteases did not affect the endothelial cell sprouting from thoracic duct explants in the in vitro lymphatic ring assay 44.

Considering the critical role of PAI-1 as a proinflammatory mediator by inhibiting the phagocytosis of neutrophils 30 and for potentiating Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-mediated activation of neutrophils 29, we examined the possibility that PAI-1 might modulate immune cell infiltration during carcinogenesis. Indeed immune cells and in particular mast cells are important contributors to the early stages of carcinogenesis. Our data indicate that PAI-1 is neither required for leukocyte infiltration in premalignant skin nor influences the role of inflammatory cells in regulating characteristics of premalignant progression during squamous carcinogenesis, e.g. keratinocyte hyperproliferation or angiogenesis. While PAI-1 levels are associated with unfavorable outcomes during the occurrence of a number of inflammatory diseases such as, acute lung injury, myocardial infarction and sepsis 45–47, PAI-1 is not a molecular determinant of inflammation during neoplastic progression which is considered as chronic disease is not significant.

Altogether, our results indicate that PAI-1 is not required for neoplastic progression in K14-HPV16 transgenic mice model. They are consistent with a previous study showing that PAI-1 does not influence tumorigenesis, tumor growth, vascularization or metastasis in the MMTV-PymT model 25. However, a large body of clinical data documents the correlation existing between high PAI-1 levels in different types of cancer and adverse outcome 1. Does this mean that high PAI-1 level in cancer is an epiphenomenon? Recent studies from different groups do point to PAI-1 being causally involved in different steps of cancer progression and identify it as a potential therapeutic target 1-48-49. Indeed, PAI-1 deficiency in mice has been reported to dramatically reduce angiogenesis in different models of tumor transplantation 21–22. In addition, PAI-1 displays a pro-angiogenic effect in other angiogenesis model such as the mouse aortic ring assay 20 and the laser-induced choroidal neoangiogenesis model 50.

Such a discrepancy or apparently contradiction could be explained by some differences that exist between the models used. It is possible that tumor growth and vascularization are governed by other processes during the development of tumors upon carcinogenesis than those provoked by the inoculation or transplantation of tumor cells which represents an acute response as opposed to de novo tumor development. In carcinogenesis models, the impact of a genetic ablation is evaluated during the whole process of cancer progression and dissemination, while it is temporally assessed in transplantation models. Compensatory increase in (an) other modulator(s) could take place during mice development and growth, but not upon transient mice challenging through tumor xenografts. Knowing the functional overlap between PAI-1 and other protease inhibitors, we analysed the expression for putative alternative inhibitors of matrix remodeling. We found that PAI-2, PN-1 and MASPIN are expressed in the K14-HPV16 tumors irrespective of PAI-1 status. These data are in line with previous findings in the MMTV-PymT 25 and TRP-1/SV40 Tag models 26. Alternatively, a functional overlap between MMP and PA systems has been demonstrated in wound healing 51. We therefore searched for other compounds of PA, MMP proteolytic systems and angiogenic factors (FGF1, VEGF) putatively involved in angiogenesis. However, we found no evidence that PAI-1 deficiency led to a compensatory increase in the levels of proteases (tPA, uPA, uPAR, MMP-2, MMP-9 and MMP-13) or angiogenic factors (FGF1, VEGF).

Differential data generated with carcinogenesis models and tumor transplantation could also rely on the important influence of various host and/or tumor factors such as for instances, cell numbers, cell types (carcinoma versus fibrosarcoma; poorly tumorigenic versus aggressive tumor cells), stages of malignancy studied, expression of other modulators and site of inoculation 24–52. In addition, it is worth noting that the two investigations using mammary and skin multistage carcinogenesis models of MMTV-PymT-induced mammary gland carcinoma 25 and the K14-HPV-16 skin squamous carcinoma model (the present study) reveal the lack of PAI-1 deficiency impacts on neoplastic progression and vascular density. These two transgenic mice have similar FVB/N background while the pro-angiogenic and pro-tumorigenic effects of PAI-1 were observed in C57BL/6 21-22-53 and Rag-1−/−/C57BL/6 18–24. There are accumulating reports of strain-related polymorphisms differentially affecting phenotypes in mouse carcinogenesis models 31–54. The phenotyping of K14-HPV16 mice in different backgrounds revealed that C57BL/6 mice are the most resistant, developing only hyperplasia, whereas BALB/c develop dysplasia and papillomas and only FVB/n mice are permissive for malignant conversion 31. Similarly, C57BL/6 strain is resistant to the development of Hras-induced SCC whereas FVB/N mice are highly susceptible 55. A strong effect of strain on tumor latency and timing of metastasis has also been reported for PymT mice 56–57. In this context, a recent study has demonstrated that the anti-metastatic outcome of MMP-9 deficiency is dependent on the strain used 54. Only mice that had a genetic background derived from C57BL/6 showed reduced metastasis in the absence of MMP9, whereas mice of the FVB/n background showed no differences after genetic ablation of the enzyme. Analysis of strain-dependent modifiers has identified Sipa1 gene on chromosome 19 and Patched gene on chromosome 13 as likely candidates for MMTV-PyMT metastasis and SCC susceptibility in FVB/N strain, respectively 55–58. Other loci related to tumor susceptibility might also be present on chromosomes 6, 9, 13, 17 and 19 59. The possibility that PAI-1 gene is itself the gene that is polymorphic is unlikely since it is located on chromosome 5. Further in-depth genetic studies are required to investigate the putative implication of other strain-dependent genes coding for PAI-1 partners such as proteases, ECM components, adhesion molecules.

PAI-1 is a multi-functional molecule displaying, some time, opposite functions during cancer progression on cell migration, apoptosis, proliferation and extracellular matrix proteolysis. The ability of PAI-1 to regulate cell proliferation and migration has been attributed to its ability to control plasmin production, to modify signaling pathways and to bind to uPAR, vitronectin, integrin and lipoprotein receptor related protein 1-14-52-60. In addition, PAI-1 protects endothelial cells against apoptosis by inhibiting plasmin-mediated dependent activation of FAS-ligand 18 or by alterning key signaling pathways such as PI3J/AKT 61. Finally, in transplantation assay, angiogenesis was dependent on the anti-proteolytic activity of PAI-1 53. Therefore, one cannot exclude the possibility that depending on the model/cell used and/or mice strain, the relevant molecules such as among others, uPAR, vitronectin, integrins, plasmin are differently available. Based on the numerous studies carried out during the last decade on PAI-1 biology, it appears that tumor and host determinants varied from one cancer type to another. Altogether our data highlight the request to compare the impact of a gene deficiency in different models of experimental tumor transplantation and multistage carcinogenesis models in order to better understand the implication of a protein during the different steps of cancer progression and to determine how to target it for therapeutical applications.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Guy Roland, I. Dasoul, E. Feyereisen, L. Poma and P. Gavitelli for their excellent technical assistance. This work was supported by grants from the European Union Framework Program projects (FP7 “MICROENVIMET” No 201279), the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique Médicale, the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique (F.N.R.S., Belgium), the Fondation contre le Cancer, the Fonds spéciaux de la Recherche (University of Liège), the Centre Anticancéreux près l’Université de Liège, the Fonds Léon Fredericq (University of Liège), the D.G.T.R.E. from the « Région Wallonne », the Interuniversity Attraction Poles Programme - Belgian Science Policy (Brussels, Belgium). AM and FB are recipients of a Televie-FNRS grant. LMC is supported by grants from the NIH/NCI.

Reference List

- 1.Binder BR, Mihaly J. The plasminogen activator inhibitor “paradox” in cancer. Immunology Letters. 2008;118:116–124. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2008.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andreasen PA, Egelund R, Petersen HH. The plasminogen activation system in tumor growth, invasion, and metastasis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2000;57:25–40. doi: 10.1007/s000180050497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rakic JM, Maillard C, Jost M, Bajou K, Masson V, Devy L, Lambert V, Foidart JM, Noel A. Role of plasminogen activator-plasmin system in tumor angiogenesis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:463–473. doi: 10.1007/s000180300039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duffy MJ. Urokinase plasminogen activator and its inhibitor, PAI-1, as prognostic markers in breast cancer: From pilot to level I evidence studies. Clinical Chemistry. 2002;48:1194–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilkins-Port CE, Higgins CE, Freytag J, Higgins SP, Carlson JA, Higgins PJ. PAI-1 is a critical upstream regulator of the TGF-beta 1/EGF-induced invasive phenotype in mutant p53 human cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2007 doi: 10.1155/2007/85208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hildenbrand R, Schaaf A. The urokinase-system in tumor tissue stroma of the breast and breast cancer cell invasion. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;34:15–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pedersen TX, Pennington CJ, Almholt K, Christensen IJ, Nielsen BS, Edwards DR, Romer J, Dano K, Johnsen M. Extracellular protease mRNAs are predominantly expressed in the stromal areas of microdissected mouse breast carcinomas. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1233–1240. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Hinsbergh VW, van den Berg EA, Fiers W, Dooijewaard G. Tumor necrosis factor induces the production of urokinase-type plasminogen activator by human endothelial cells. Blood. 1990;75:1991–1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cho SH, Tam SW, Demissie-Sanders S, Filler SA, Oh CK. Production of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 by human mast cells and its possible role in asthma. J Immunol. 2000;165:3154–3161. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.6.3154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lund LR, Riccio A, Andreasen PA, Nielsen LS, Kristensen P, Laiho M, Saksela O, Blasi F, Dano K. Transforming growth factor-beta is a strong and fast acting positive regulator of the level of type-1 plasminogen activator inhibitor mRNA in WI-38 human lung fibroblasts. EMBO J. 1987;6:1281–1286. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02365.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Offersen BV, Nielsen BS, Hoyer-Hansen G, Rank F, Hamilton-Dutoit S, Overgaard J, Andreasen PA. The myofibroblast is the predominant plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-expressing cell type in human breast carcinomas. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:1887–1899. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63547-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Degryse B, Neels JG, Czekay RP, Aertgeerts K, Kamikubo Y, Loskutoff DJ. The low density lipoprotein receptor-related protein is a motogenic receptor for plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:22595–22604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313004200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kamikubo Y, Neels JG, Degryse B. Vitronectin inhibits plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-induced signalling and chemotaxis by blocking plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 binding to the low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein. International Journal of Biochemistry & Cell Biology. 2009;41:578–585. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2008.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Czekay RP, Aertgeerts K, Curriden SA, Loskutoff DJ. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 detaches cells from extracellular matrices by inactivating integrins. Journal of Cell Biology. 2003;160:781–791. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200208117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schar CR, Jensen JK, Christensen A, Blouse GE, Andreasen PA, Peterson CB. Characterization of a site on PAI-1 that binds to vitronectin outside of the somatomedin B domain. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2008;283:28487–28496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804257200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen YB, Budd RC, Kelm RJ, Sobel BE, Schneider DJ. Augmentation of proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells by plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis and Vascular Biology. 2006;26:1777–1783. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000227514.50065.2a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ploplis VA, Balsara R, Sandoval-Cooper MJ, Yin ZJ, Batten J, Modi N, Gadoua D, Donahue D, Martin JA, Castellino FJ. Enhanced in vitro proliferation of aortic endothelial cells from plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-deficient mice. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2004;279:6143–6151. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307297200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bajou K, Peng H, Laug WE, Maillard C, Noel A, Foidart JM, Martial JA, DeClerck YA. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 protects endothelial cells from FasL-mediated apoptosis. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:324–334. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Noel A, Maillard C, Rocks N, Jost M, Chabottaux V, Sounni NE, Maquoi E, Cataldo D, Foidart JM. Membrane associated proteases and their inhibitors in tumour angiogenesis. Journal of Clinical Pathology. 2004;57:577–584. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2003.014472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Devy L, Blacher S, Grignet-Debrus C, Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, Gils A, Carmeliet G, Carmeliet P, Declerck PJ, Noel A, Foidart JM. The pro- or antiangiogenic effect of plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 is dose dependent. FASEB J. 2002;16:147–154. doi: 10.1096/fj.01-0552com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bajou K, Noel A, Gerard RD, Masson V, Brunner N, Holst-Hansen C, Skobe M, Fusenig NE, Carmeliet P, Collen D, Foidart JM. Absence of host plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 prevents cancer invasion and vascularization. Nat Med. 1998;4:923–928. doi: 10.1038/nm0898-923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gutierrez LS, Schulman A, Brito-Robinson T, Noria F, Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. Tumor development is retarded in mice lacking the gene for urokinase-type plasminogen activator or its inhibitor, plasminogen activator inhibitor-1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:5839–5847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leik CE, Su EJ, Nambi P, Crandall DL, Lawrence DA. Effect of pharmacologic plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 inhibition on cell motility and tumor angiogenesis. Journal of Thrombosis and Haemostasis. 2006;4:2710–2715. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maillard C, Jost M, Romer MU, Brunner N, Houard X, Lejeune A, Munaut C, Bajou K, Melen L, Dano K, Carmeliet P, Fusenig NE, Foidart JM, et al. Host plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 promotes human skin carcinoma progression in a stage-dependent manner. Neoplasia. 2005;7:57–66. doi: 10.1593/neo.04406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almholt K, Nielsen BS, Frandsen TL, Brunner N, Dano K, Johnsen M. Metastasis of transgenic breast cancer in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 gene-deficient mice. Oncogene. 2003;22:4389–4397. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maillard CM, Bouquet C, Petitjean MM, Mestdagt M, Frau E, Jost M, Masset AM, Opolon PH, Beermann F, Abitbol MM, Foidart JM, Perricaudet MJ, Noel AC. Reduction of brain metastases in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-deficient mice with transgenic ocular tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:2236–2242. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Kempen LCL, de Visser KE, Coussens LM. Inflammation, proteases and cancer. European Journal of Cancer. 2006;42:728–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cao C, Lawrence DA, Li Y, Von Arnim CA, Herz J, Su EJ, Makarova A, Hyman BT, Strickland DK, Zhang L. Endocytic receptor LRP together with tPA and PAI-1 coordinates Mac-1-dependent macrophage migration. EMBO J. 2006;25:1860–1870. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kwak SH, Wang XQ, He Q, Fang WF, Mitra S, Bdeir K, Ploplis VA, Xu Z, Idell S, Cines D, Abraham E. Plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 potentiates LPS-induced neutrophil activation through a JNK-mediated pathway. Thromb Haemost. 2006;95:829–835. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YJ, Liu G, Lorne EF, Zhao X, Wang J, Tsuruta Y, Zmijewski J, Abraham E. PAI-1 inhibits neutrophil efferocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:11784–11789. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801394105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coussens LM, Hanahan D, Arbeit JM. Genetic predisposition and parameters of malignant progression in K14-HPV16 transgenic mice. Am J Pathol. 1996;149:1899–1917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Kempen LCL, Rhee JS, Dehne K, Lee J, Edwards DR, Coussens LM. Epithelial carcinogenesis: dynamic interplay between neoplastic cells and their microenvironment. Differentiation. 2002;70:610–623. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-0436.2002.700914.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coussens LM, Raymond WW, Bergers G, Laig-Webster M, Behrendtsen O, Werb Z, Caughey GH, Hanahan D. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1382–1397. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ribatti D, Nico B, Crivellato E, Roccaro AM, Vacca A. The history of the angiogenic switch concept. Leukemia. 2007;21:44–52. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2404402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Coussens LM, Tinkle CL, Hanahan D, Werb Z. MMP-9 supplied by bone marrow-derived cells contributes to skin carcinogenesis. Cell. 2000;103:481–490. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00139-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arbeit JM, Munger K, Howley PM, Hanahan D. Progressive squamous epithelial neoplasia in K14-human papillomavirus type 16 transgenic mice. J Virol. 1994;68:4358–4368. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.7.4358-4368.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.de Visser KE, Korets LV, Coussens LM. Early neoplastic progression is complement independent. Neoplasia. 2004;6:768–776. doi: 10.1593/neo.04250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cao Y, Zhong W. Tumor-derived lymphangiogenic factors and lymphatic metastasis. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2007;61:534–539. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2007.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cao YH. Opinion - Emerging mechanisms of tumour lymphangiogenesis and lymphatic metastasis. Nature Reviews Cancer. 2005;5:735–743. doi: 10.1038/nrc1693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eichten A, Hyun WC, Coussens LM. Distinctive features of anglogenesis and lymphangiogenesis determine their functionality during de novo tumor development. Cancer Research. 2007;67:5211–5220. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Junankar SR, Eichten A, Kramer A, de Visser KE, Coussens LM. Analysis of immune cell infiltrates during squamous carcinoma development. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2006;11:36–43. doi: 10.1038/sj.jidsymp.5650024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eichten A, Hyun WC, Coussens LM. Distinctive features of anglogenesis and lymphangiogenesis determine their functionality during de novo tumor development. Cancer Research. 2007;67:5211–5220. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Adams RH, Alitalo K. Molecular regulation of angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2007;8:464–478. doi: 10.1038/nrm2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruyere F, Melen-Lamalle L, Blacher S, Roland G, Thiry M, Moons L, Frankenne F, Carmeliet P, Alitalo K, Libert C, Sleeman JP, Foidart JM, Noel A. Modeling lymphangiogenesis in a three-dimensional culture system. Nature Methods. 2008;5:431–437. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.El Solh AA, Bhora M, Pineda L, Aquilina A, Abbetessa L, Berbary E. Alveolar plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 predicts ARDS in aspiration pneumonitis. Intensive Care Medicine. 2006;32:110–115. doi: 10.1007/s00134-005-2847-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Prabhakaran P, Ware LB, White KE, Cross MT, Matthay MA, Olman MA. Elevated levels of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in pulmonary edema fluid are associated with mortality in acute lung injury. American Journal of Physiology-Lung Cellular and Molecular Physiology. 2003;285:L20–L28. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00312.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Takeshita K, Hayashi M, Iino S, Kondo T, Inden Y, Iwase M, Kojima T, Hirai M, Ito M, Loskutoff DJ, Saito H, Murohara T, Yamamoto K. Increased expression of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in cardiomyocytes contributes to cardiac fibrosis after myocardial infarction. American Journal of Pathology. 2004;164:449–456. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63135-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Andreasen PA. PAI-1 - a potential therapeutic target in cancer. Curr Drug Targets. 2007;8:1030–1041. doi: 10.2174/138945007781662346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McMahon B, Kwaan HC. The plasminogen activator system and cancer. Pathophysiol Haemost Thromb. 2008;36:184–194. doi: 10.1159/000175156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lambert V, Munaut C, Noel A, Frankenne F, Bajou K, Gerard R, Carmeliet P, Defresne MP, Foidart JM, Rakic JM. Influence of plasminogen activator inhibitor type 1 on choroidal neovascularization. FASEB J. 2001;15:1021–1027. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0393com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lund LR, Romer J, Bugge TH, Nielsen BS, Frandsen TL, Degen JL, Stephens RW, Dano K. Functional overlap between two classes of matrix-degrading proteases in wound healing. EMBO J. 1999;18:4645–4656. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee CC, Huang TS. Plasminogen Activator inhibitor-1: the expression biological functions and effects on tumorigenesis tumor cell adhesion migration. Journal of cancer molecules. 2005;1:25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bajou K, Masson V, Gerard RD, Schmitt PM, Albert V, Praus M, Lund LR, Frandsen TL, Brunner N, Dano K, Fusenig NE, Weidle U, et al. The plasminogen activator inhibitor PAI-1 controls in vivo tumor vascularization by interaction with proteases, not vitronectin. Implications for antiangiogenic strategies. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:777–784. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.4.777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Martin MD, Carter KJ, Jean-Philippe SR, Chang M, Mobashery S, Thiolloy S, Lynch CC, Matrisian LM, Fingleton B. Effect of ablation or inhibition of stromal matrix metalloproteinase-9 on lung metastasis in a breast cancer model is dependent on genetic background. Cancer Research. 2008;68:6251–6259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wakabayashi Y, Mao JH, Brown K, Girardi M, Balmain A. Promotion of Hras-induced squamous carcinomas by a polymorphic variant of the Patched gene in FVB mice. Nature. 2007;445:761–765. doi: 10.1038/nature05489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lifsted T, Le Voyer T, Williams M, Muller W, Klein-Szanto A, Buetow KH, Hunter KW. Identification of inbred mouse strains harboring genetic modifiers of mammary tumor age of onset and metastatic progression. International Journal of Cancer. 1998;77:640–644. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980812)77:4<640::aid-ijc26>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fluck MM, Schaffhausen BS. Lessons in signaling and tumorigenesis from polyomavirus middle T antigen. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:542–63. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00009-09. Table. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Park YG, Zhao X, Lesueur F, Lowy DR, Lancaster M, Pharoah P, Qian X, Hunter KW. Sipa1 is a candidate for underlying the metastasis efficiency modifier locus Mtes1. Nat Genet. 2005;37:1055–1062. doi: 10.1038/ng1635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hunter KW, Broman KW, Voyer TL, Lukes L, Cozma D, Debies MT, Rouse J, Welch DR. Predisposition to efficient mammary tumor metastatic progression is linked to the breast cancer metastasis suppressor gene Brms1. Cancer Res. 2001;61:8866–8872. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jankun J, Aleem AM, Specht Z, Keck RW, Lysiak-Szydlowska W, Selman SH, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. PAI-1 induces cell detachment, downregulates nucleophosmin (B23) and fortilin (TCTP) in LnCAP prostate cancer cells. International Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2007;20:11–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balsara RD, Castellino FJ, Ploplis VA. A novel function of plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 in modulation of the AKT pathway in wild-type and plasminogen activator inhibitor-1-deficient endothelial cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281:22527–22536. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M512819200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]