Summary

Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) is the causative agent of the human disease Tuberculosis, and remains a worldwide health threat responsible for ~1.7 million deaths annually. During infection, Mtb prevents acidification of the engulfing phagosome, thus blocking endocytic progression and eventually leading to stable residence. The diterpenoid metabolite isotuberculosinol (isoTb) exhibits biological activity indicative of a role in this early arrest of phagosome maturation. Presumably, isoTb production should be induced by phagosomal entry. However, the relevant enzymatic genes are not transcriptionally upregulated during engulfment. Previous examination of the initial biosynthetic enzyme (Rv3377c/MtHPS) involved in isoTb biosynthesis revealed striking inhibition by its Mg2+ co-factor, leading to the hypothesis that the depletion of Mg2+ observed upon phagosomal engulfment may act to trigger isoTb biosynthesis. While Mtb is typically grown in relatively high levels of Mg2+ (0.43 mM), shifting Mtb to media with phagosomal levels (0.1 mM) led to a significant (~10-fold) increase in accumulation of the MtHPS product, halimadienyl diphosphate, as well as easily detectable amounts of the derived bioactive isoTb. These results demonstrate isoTb production by Mtb specifically under conditions that mimic phagosomal cation concentrations, and further support a role for isoTb in the Mtb infection process.

Introduction

First described in 1882, Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb), the main pathogen responsible for the human disease Tuberculosis, remains a major health concern into the 21st century. It has been estimated that up to one-third of the global population harbors the bacteria, with approximately 1.7 million deaths due to Tuberculosis yearly (Russell et al., 2010). Further, the recent emergence of multi- and extremely drug resistance strains highlights the continued relevance of this pernicious human pathogen (Chiang et al., 2010). The complete mechanism of pathogenesis is unknown, but likely involves a multi-factorial attack of the immune system (Deretic et al., 2006).

Mtb resides within macrophage phagosome compartments that are arrested at an early stage of maturation that prevents delivery of Mtb to bactericidal phagolysomes (Vergne et al., 2004). Therefore, a key step in the Mtb infection process is blocking endocytic progression of the bacteria containing phagosome. Although there is clear evidence that mycobacterial specific cell surface lipids play a role in halting phagosome maturation (Guenin-Mace et al., 2009, Chua et al., 2004), it seems likely that there are multiple factors affecting this critical aspect of the Mtb life-cycle (Russell, 2007), as independent genetic screens have uncovered non-overlapping sets of genes required for pathogenesis (Sassetti & Rubin, 2003, Joshi et al., 2006, Rengarajan et al., 2005).

The only genetic screen focused on Mtb genes involved in early infection highlighted a role for two previously unstudied genes, Rv3377c and Rv3378c, found in an operon that seemed to be involved in isoprenoid/terpenoid biosynthesis (Pethe et al., 2004). This was verified by subsequent biochemical analysis, as Rv3377c was demonstrated to encode a class II diterpene cyclase that carries out bicyclization and rearrangement of the universal diterpenoid precursor (E,E,E)-geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) to produce halimadienyl diphosphate (HPP) (Nakano et al., 2005). Subsequently, it has been reported that the enzyme encoded by Rv3378c acts upon HPP to produce either a mixture of the corresponding primary and tertiary alcohols [termed tuberculosinol and isotuberculosinol, respectively (Nakano, 2005)], or a novel tricyclic diterpene (Mann et al., 2009b). Recent results demonstrate that the true enzymatic product is isotuberculosinol (isoTb) (Spangler et al., 2010, Maugel et al., 2010). Notably, in bead-based phagocytosis assays pure isoTb halted acidification at a pH 0.5 units above that of the control (Mann et al., 2009b), matching the defect observed with the corresponding Mtb Rv3377c and Rv3378c mutants, which also were impaired in their ability to replicate in macrophage cell culture (Pethe et al., 2004).

The biological activity of isoTb strongly suggests a role in inhibiting the phagosome maturation process and, while a recent report demonstrates that it is possible to detect isoTb from Mtb (Prach et al., 2010), the levels of isoTb found in Mtb grown in the standard 7H9 media are quite low, suggesting the possibility that isoTb biosynthesis might need to be increased upon phagosomal engulfment. However, genome-wide pre- and post-infection microarrays have failed to find changes in the transcription of Rv3377c and Rv3378c upon macrophage infection (Rohde et al., 2007, Waddell & Butcher, 2007, Stewart et al., 2005).

Our recent kinetic analysis of the HPP synthase encoded by Rv3377c (MtHPS) uncovered an intriguing biphasic response of enzymatic activity to its divalent magnesium ion (Mg2+) co-factor, which led us to hypothesize that this might act as a physiologically relevant regulatory mechanism (Mann et al., 2009a). Specifically, MtHPS exhibits optimal activity in the presence of 0.1 mM Mg2+, and even slightly higher levels dramatically reduce its activity (i.e. 60% reduction at 0.5 mM and above). Intriguingly, during Mtb entry the bacteria transition from the high-µM levels of Mg2+ observed in oral and lung mucus (Effros et al., 2005, Shpitzer et al., 2007) to the 10–50 µM levels found in macrophage phagosomes, at least those containing Salmonella (Garcia-del Portillo et al., 1992), which is close to the optimal level for MtHPS activity in vitro. In addition, studies of other intracellular pathogens, such as Brucella suis, further support the low concentration of magnesium in the phagosome (Lavigne et al., 2005). Indeed, it is hypothesized that Mtb shares a parallel strategy for surviving the initial shock of uptake into this depleted environment with Salmonella and Brucella (Lavigne et al., 2005, Buchmeier et al., 2000), although such depletion of Mg2+ has not been directly measured with Mtb containing phagosomes. Nevertheless, we hypothesized that MtHPS activity, representing the committed step in isoTb biosynthesis (Figure 1), is induced by this depletion of Mg2+ (Mann et al., 2009a). This also was based in part on the observation of such Mg2+-dependent regulation of plant class II diterpene cyclases (Prisic & Peters, 2007, Mann et al., 2010), which are distant homologs of MtHPS (Cao, 2010). Indeed, active site mutant analysis (Nakano & Hoshino, 2009) and shared susceptibility to mechanism based inhibitors indicate that MtHPS catalysis is analogous to that mediated by these plant enzymes (Mann et al., 2009a). This hypothesis also might then explain previous difficulties in detecting isoTb and halimadienol from Mtb, which is typically grown rich media containing higher amounts (~0.43 mM) of Mg2+ (Wards, 1996).

Figure 1. Isotuberculosinol biosynthesis.

Synthesis of isotuberculosinol proceeds via the cyclization of geranylgeranyl diphosphate (GGPP) to halimadienyl diphosphate (HPP) via the MtHPS encoded by Rv3377c, which is further transformed to isotuberculosinol (isoTb) via the enzyme encoded by Rv3378c.

Here we have tested and verified this hypothesis in Mtb. By understanding the metabolism and regulation of this pathway, we hope to clarify the role of isoTb in the Mtb infection process, and shed light on this factor assisting Mtb attack on the human immune system.

Experimental procedures

General

Geranylgeranyl diphosphate was purchased from Isoprenoids, LC (Tampa, FL). All other chemicals were purchased from Fisher Scientific (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise noted. Molecular biology reagents were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) unless otherwise noted. High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) separations were performed on an Agilent (Santa Clara, CA) 1100 instrument equipped with automated sample injector and fraction collector, as well as diode array detector and heated column compartment. GC-MS analysis was performed on a Varian 3900 GC with Saturn 2100T ion-trap detector (Palo Alto, CA) using an Agilent HP-1MS column (Santa Clara, CA).

Measurement of halimadienyl diphosphate in recombinant E. coli

To endow E. coli with the ability to produce HPP, the previously described MBP-Rv3377c fusion from a pTH1/DEST:Rv3377c expression vector (Mann et al., 2009b) was cloned into a previously described pACYC-Duet vector (Novagen, Merck Corp.), that already contained a GGPP synthase from Abies grandis (Burke & Croteau, 2002) in the second multiple cloning site (Cyr et al., 2007). Specifically, MBP-Rv3377c was cloned into the first multiple cloning site of this pGG vector using 5' NcoI and 3' HindIII restriction sites, which were introduced into MBP-Rv3377c by PCR, creating a pGG/MBP-Rv3377c co-expression vector. E. coli C41 (Lucigen, Middleton, WI) was transformed with this vector and selectively grown on NZY agar plates or in TB liquid media (12 g/L casein, 24 g/L yeast extract, 8 mL/L glycerol, 100 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) These recombinant cells were grown in modified liquid TB media (containing 0.43 mM MgCl2) to OD600 ~ 0.8, with cultures then moved to 16 °C for 1 hr, followed by induction with 0.5 mM IPTG, with an additional 14–16 hrs of fermentation. Control cultures were allowed to grow for the entire experimental period. The effect of Mg2+ depletion was assessed by pelleting 50-mL cultures at 4 °C. These cells were washed with 0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7, and then resuspended in 50-mL fresh TB culture media supplemented either 0.1 or 0.4 mM MgCl2, and fermentation continued at 16 °C. Triplicate time points were taken prior to this media shift, and then 30 min., 1 hr, 6 hrs, and 24 hrs following the shift in media (i.e., transfer), by pelleting cells from a 50-mL aliquot and extracting the resulting clarified media with an equal volume of hexane, which was then dried to completion and resuspended in 100 µL fresh hexane for analysis. Pellets from each time point were weighed and analyzed for overexpression of MtHPS via denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and subsequent Coomassie blue staining. Bands were quantified and subject to statistical analysis.

Construction of a ΔRv3377-78c strain and Rv3377-78c complementing plasmid

A ΔRv3377-78c strain was constructed by in Mtb CDC1551 by an allelic exchange method using the pYUB854 plasmid (Bardarov et al., 2002). The Mtb rpsL (Rv0682) gene was PCR amplified and ligated into the PacI site of pYUB854 for counter selecting purposes (Sander et al., 1995). For allelic exchange, ~600-bp DNA fragments corresponding to the upstream and downstream region of the Rv3377–Rv3378 locus were cloned into pYUB854 to flank the hygromycin resistance gene. The final plasmid was electroporated into streptomycin-resistant Mtb CDC1551. Hygromycin-resistant and streptomycin-resistant clones were screened by PCR and Southern blot to confirm loss of Rv3377c and Rv3378c. Rv3377c and Rv3378c were cloned from Mtb CDC1551, recombined as a single transcriptional unit into pMV361 (Stover et al., 1992) under control of a blaF promoter (Lim et al., 1995), and verified by complete gene sequencing. The resulting plasmid was used to complement the ΔRv3377-78c Mtb CDC1551 by transformation following published protocols (Snapper et al., 1988).

Measurement of isotuberculosinol in Mtb

Mtb was grown using 7H9 media (0.5 g/L ammonium sulfate, 0.5g/L L-glutamic acid, 0.1g/L sodium citrate, 1.0 mg/L pyridoxine, 0.5 mg/L biotin, 2.5 g/L dibasic sodium phosphate, 1.0 g/L monobasic potassium phosphate, 0.04 g/L ferric ammonium citrate, 0.5 mg/L calcium chloride, 1.0 mg/L zinc sulfate, 1.0 copper sulfate, 8.5 g/L sodium chloride, 50 g/L bovine albumin, 20 g/L dextrose, 0.03 g/L catalase, pH 6.6, and typically 0.05 g/L magnesium sulfate). Modified liquid media was made up by altering the amount of MgSO4 to achieve concentrations of 0.1 mM Mg2+ and/or by the addition of Mn2+ 2.5 mM (MnCl2·4H2O). Specifically, to make up ‘7H9-low’ media containing only 0.1 mM Mg2+ with the addition of 2.5 mM Mn2+, and ‘7H9-Mn2+’ media wherein the only change is the addition of 2.5 mM Mn2+ (as the counter-anion does not affect MtHPS activity; Table S1). Bacteria (~1×1011 cfu) were innoculated into 200 mL of media and grown for 2 weeks. Cells were then pelleted and resuspended in 7H9 or experimental media conditions and allowed to grow for 2 more weeks. Media was then extracted with equivalent volumes of hexane and dried. Extracts were resuspended in 1 mL fresh hexanes for initial analysis via gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy (GC-MS) against previously prepared authentic standards (Mann et al., 2009a, Mann et al., 2009b). Crude extracts proved too complex for quantification, and samples were dried and resuspended in 1:1 (v/v) mixture of acetonitrile:water for fractionation by HPLC utilizing C-8 reverse-phase analytical column (Kromasil, Brewster, NY) with a flow rate of 0.2 mL/min at 40 °C against a 50–100% acetonitrile (ACN) gradient (0–15 min, 50% ACN 0.5 ml/min; 15–30 min 50–100% ACN 0.1 mL/min; 30–39.9 min 100% ACN 0.5 mL/min; 39.9–40.0 50% ACN). The fractionated extracts were dried and resuspended in hexane for GC-MS analysis. Extracts were normalized against endogenous menaquinone concentrations, which were quantified as varying less than 10% by comparison to known concentrations of an authentic standard (Table S2) (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and the concentrations of isoTb, halimadienol, and geranylgeraniol diterpenoids were quantified via total ion chromatograph against a standard curve constructed with the diterpene cembrene (Sigma-Aldrich) using amounts ranging from 10 – 500 ng/uL. Trace metabolites were quantified via extracted ion chromatographs of ions 119, 191, 290.

Transcriptional analysis of Rv3377c and Rv3378c in Mtb

Mtb CDC1551, Mtb CDC1551 ∆3377-78c, and Mtb CDC1551 ∆3377-78c complemented strains were grown in the previously described experimental conditions, and 4 mL of bacterial culture were pelleted via centrifugation for RNA extraction. Bacterial pellets were resuspended in 1 mL GTC buffer (4M guanidine thiocyanate, 0.5% sodium-lauryl sarcosine, 25 mM sodium citrate, 0.1 M β-mercaptoethanol) and frozen at −80 °C for 16 hours. Cultures were thawed and pelleted before washing in PBS buffer (0.15 M sodium chloride, 10 mM dibasic sodium phosphate, 1.75 mM monobasic sodium phosphate, and 0.1% tween-20, pH to 7.4). Washed pellets were resuspened in 200 µL lysozyme (10 mg/mL) and incubated at 25 °C for 15 minutes. Hot (65 °C) Trizol (750 µL) was added before cellular disruption with ~0.5 mL glass beads (0.1 mm) for 2 minutes by beadbeating. Lysates were phase separated by adding 200 µL chloroform and centrifuged for 15 minutes. 500 µL ethyl alcohol was added to the aqueous phase and RNA was isolated via the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Valencia, CA) with elution by 2 × 50 µL sterile water. The resulting RNA was treated with Ambion TurboDNAse Free according to manufacturer protocols (Austin, TX) before quantification. Equivalent concentrations of RNA (600 ng) were converted to cDNA via the Iscript reaction as per manufacturer protocols (BioRad, Hercules, CA), and 2 µL of each cDNA reaction was amplified with gene-specific primers for Rv3377c or Rv3378c in 25 µL reactions using Invitrogen Accuprime Taq (Carlsbad, CA) and recommended polymerase chain reaction conditions (95°C 5 min, followed by 95 °C 30 sec, 60 °C 2 min, 72 °C 3 min for 45 cycles, 72 °C 10 minutes). Transcription of endogenous sigma factor A (SigA, Rv2703) was measured for normalization of gene transcription. PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide (Figure S1) and visualized with UV irradiation for quantification and statistical analysis (Table S3).

Results

As an initial test of our hypothesis that external Mg2+ levels can regulate MtHPS activity inside bacterial cells, we engineered E. coli for the production of HPP. Specifically, E. coli transformed with a single plasmid enabling inducible co-expression of a GGPP synthase and MtHPS expressed as fusion protein with MBP. Following induction, this recombinant E. coli was subjected to changes in environmental Mg2+ levels designed to mimic the conditions that Mtb is believed to experience when it is engulfed by the phagosome. In particular, the cells were grown in media containing 0.43 mM Mg2+, induced, and then pelleted ~16 hrs after induction. These cell pellets were washed, and then transferred to media with either at a high (0.4 mM) or low (0.1 mM) level of Mg2+, with the latter approximating that found in phagosomes (Garcia-del Portillo et al., 1992), and equivalent to the optimal concentration for MtHPS activity in vitro (Mann et al., 2009a). Cultures transferred to high (0.43 mM) Mg2+ media exhibited reduced accumulation of HPP-derived HaOH compared to cultures transferred to low (0.1 mM) Mg2+ (Figure 2A). This appears to occur due to increased flux of GGPP through MBP-MtHPS, as concentrations of GGPP-derived GGOH are low compared to concentrations in cultures transferred to high Mg2+ media (Figure 2B), yet the relative overall concentration of diterpenoid metabolites is comparable between populations. During this time, no changes in MBP-MtHPS protein levels were noted. This confirms that, at least in E. coli, changes in environmental Mg2+ levels do influence HPP production, presumably via a direct effect on intrinsic MtHPS activity within the bacteria.

Figure 2. Magnesium depletion triggers increased HPP production by MtHPS in E. coli.

- Concentration of GGPP per gram of bacterial fresh weight over time.

- Concentration of HPP per gram of bacterial fresh weight over time.

It is well understood that Mtb and E. coli differ drastically, especially in metabolism, growth, and cell wall constituents (Kumar & Robbins, 2007). Because of these differences, it was imperative to determine if similar Mg2+ depletion could also directly influence internal enzymatic activity and metabolic flux in Mtb. Furthermore, at the time this study was initiated, the expected HPP intermediate and bioactive isoTb end product had not yet been detected in Mtb itself. Notably, the preferred divalent cation for the enzyme encoded by Rv3378c that converts HPP to isoTb is Mn2+ (Mann et al., 2009b), which might also limit isoTb production. To address these latter two issues, Mtb was grown in 7H9 media containing either the standard Mg2+ concentration of 0.43 mM, in the absence or presence of 2.5 mM Mn2+ (7H9 and 7H9-Mn2+, respectively), or 7H9 media containing only 0.1 mM Mg2+ as well as 2.5 mM Mn2+ (7H9-low). After growth, the bacteria and media were extracted with organic solvent, which was then analyzed for the presence of the precursor GGPP (detected as geranylgeraniol, GGOH), the MtHPS derived intermediate HPP (detected as halimadienol, HaOH), and the bioactive end product isoTb (Table 1). In these extracts, isoTb was not found in Mtb grown in unmodified 7H9 media, although small amounts of HPP derived HaOH were detected, indicating that isoTb levels may be lower than our detection limit (i.e. less than 20 ng/L bacterial culture). However, isoTb was easily detected in Mtb grown in 0.1 mM Mg2+ containing 7H9 media supplemented with 2.5 mM Mn2+, although these cells also were apparently depleted of GGPP, suggesting limitations exerted by exhaustion of this precursor. Conversely, addition of Mn2+ to 7H9 media led to the loss of HPP production, with isoTb also not detected, although considerably larger amounts of GGPP derived GGOH were observed. This preliminary data suggested environmental control of isoTb production occurs via regulation of MtHPS activity, which is easily inhibited by Mg2+ concentrations over 0.1 mM and cannot utilize Mn2+ (Nakano & Hoshino, 2009)(Table S1), while the GGPP and isoTb synthases are able to utilize Mn2+ in place of Mg2+.

Table 1.

Effect of divalent cations on isoTb production by Mtb.Mtb CDC1551 was grown in the indicated media (7H9, which contains 0.43 mM Mg2+; 7H9-Mn2+ was supplemented with 2.5 mM Mn2+; while 7H9-low contains only 0.1 mM Mg2+, although it also was supplemented with 2.5 mM Mn2+). Production of the diterpenoid metabolites GGPP, detected as the derived geranylgeraniol (GGOH), and HPP, detected as the derived halimadienol (HaOH), as well as isotuberculosinol (isoTb), were analyzed via comparison to prepared standards and normalized against endogenous menaquinone concentrations.

| Metabolite Concentration (µg/L) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Media | GGOH | → | HaOH | → | IsoTb |

| 7H9 | + | + | N.D. | ||

| 7H9-Mn2+ | ++ | N.D. | N.D. | ||

| 7H9-low | N.D. | + | + | ||

(N.D. = not detected; + indicates levels of production over 0.25 ug/L, ++ indicates levels of production over 0.75 ug/L). The limit of detection for this experiment is 20 ng/L culture.

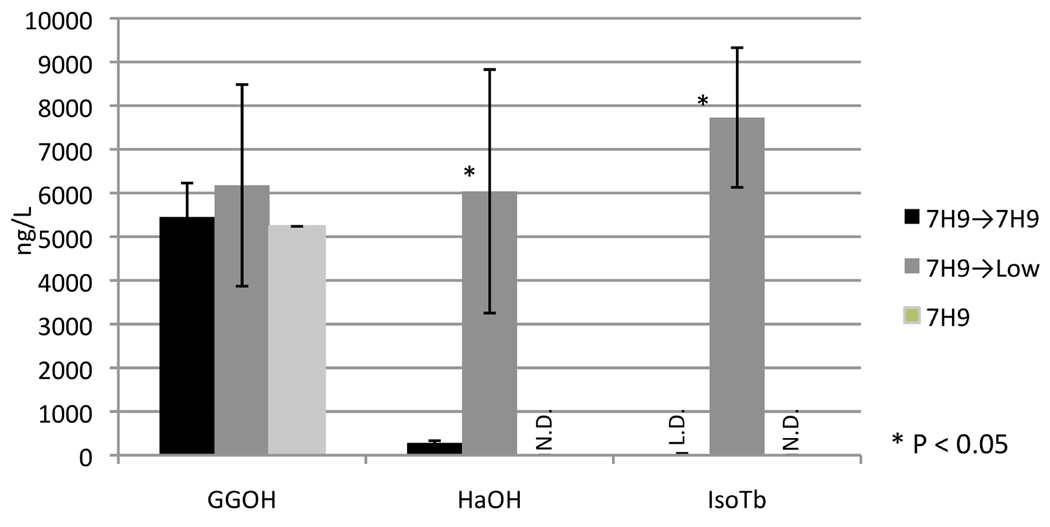

To directly test our hypothesis that external Mg2+ levels can regulate MtHPS activity and, hence, isoTb production in Mtb itself, the mycobacteria was grown in unmodified 7H9 media and transferred/shifted by pelleting and resuspending either back into unmodified 7H9 media or into low Mg2+ 7H9 media supplemented with Mn2+ (7H9-low). Strikingly, isoTb was easily detected when Mtb was grown in unmodified 7H9 media and then transferred to 7H9-low media, although only trace amounts were detected when the bacteria was shifted back to 7H9 media, indicating ≥100-fold increase in this metabolite, to an easily detectable 3–5 µg/L (Figure 3). This drastic increase in isoTb production presumably occurs due to the observed ~10-fold increase in intermediate HPP production, and maintenance of GGPP precursor levels (Figure 4), as Rv3377c and Rv3378c transcript levels do not change (Table S3).

Figure 3. Biosynthesis of isoTb is triggered by Mg2+ depletion.

Selected ion (m/z = 119 + 191 + 290) chromatogram from GC-MS analysis of extracted diterpenoid metabolites from M. tuberculosis H37Rv grown in 7H9 media and transferred into new 7H9 media containing either the normal high (0.43 mM) or low (0.1 mM) concentration of Mg2+ compared to isoTb standard reference chromatogram (as indicated). The chromatograms are vertically offset for clarity, but those of the extracts from high and low [Mg2+] exposed Mtb cultures are shown on the same absolute scale.

Figure 4. Magnesium depletion triggers diterpenoid metabolism in Mtb.

Mtb CDC1551 grown in 7H9 media for 4 weeks (“7H9”) or grown in 7H9 for 2 weeks and new 7H9 media for 2 weeks (“7H9→7H9”) show distinctly different production profiles of diterpenoid metabolites HPP (detected here as the derived HaOH) and IsoTb from bacteria subject to growth in 7H9 and subsequent shift to 7H9 containing 0.1 mM Mg2+ and 2.5 mM Mn2+ (“7H9→Low”). However, the change in environmental media conditions does not appear to effect availability of the precursor molecule, GGPP (detected here as the derived GGOH). (N.D. = not detected, L.D. = concentrations at or below limit of positive identification, 20 ng/L culture). Shown is the average, with error bars indicating the standard deviation, of two independent biological samples.

To further verify the role of Rv3377c and Rv3378c in isoTb production, as well as the observed biochemical regulation, the key Mg2+ depletion growth experiments were repeated with both wild-type Mtb CDC1551 and a derived ΔRv3377-78c strain, which was also further complemented with a plasmid expressing Rv3377c and Rv3378c under control of a constitutive promoter. Specifically, these three Mtb variants were grown in unmodified 7H9 media, then pelleted and resuspended either back into unmodified 7H9 media or into 7H9-low media. As expected, the Mtb ΔRv3377-78c mutant did not synthesize HPP or isoTb under any conditions, demonstrating that the enzymes encoded by Rv3377c and Rv3378c are required for such biosynthesis. Conversely, the complemented strain exhibited similar induction of isoTb production by the shift to 7H9-low, but not 7H9, as wild type Mtb, indicating these genes are responsible for production of these diterpenoid metabolites in Mtb, consistent with previously reported analysis using a Mycobacterium smegmatis expression system (Prach et al., 2010). In addition, these results are consistent with a biochemical mechanism by which Mg2+ depletion triggers isoTB production.

Discussion

The biological activity exhibited by the Mtb diterpenoid metabolite isoTb is strongly indicative of a role early in the infection process. Specifically, it is involved in arresting initial acidification of the phagosomal compartment. Differences in pH profile are evident within 30 min. in phagosomes containing Mtb lacking the relevant enzymatic genes, Rv3377c and Rv3378c, relative to those containing wild-type Mtb (Pethe et al., 2004), and within 10 min. in phagosomes fed isoTb coated versus control beads (Mann et al., 2009b). These effects imply that isoTb should be either constitutively produced at physiological relevant levels or rapidly biosynthesized upon phagosomal uptake. However, while transcription of Rv3377c and Rv3378c is not increased upon phagosome engulfment (Rohde et al., 2007, Waddell & Butcher, 2007, Stewart et al., 2005), indicating constitutive expression of the biosynthetic machinery, and isoTb production by Mtb has been reported (Prach et al., 2010), as demonstrated here isoTb is only found at very low levels in Mtb grown in the standard 7H9 media.

The Rv3377c encoded MtHPS catalyzes the committed step in isoTb biosynthesis (Figure 1), and, hence, controls flux into isoTb production. Intriguingly, MtHPS activity is optimal at a low (0.1 mM) concentration of Mg2+ (Mann et al., 2009a), which is close to the levels found in the phagosome (Garcia-del Portillo et al., 1992), while MtHPS activity is significantly reduced at higher concentrations of Mg2+, particularly at levels ≥0.5 mM, which is similar to what is found in oral and lung mucus (Effros et al., 2005, Shpitzer et al., 2007). In addition, internal bacterial cation concentrations have been shown to change to reflect environmental levels (Hurwitz & Rosano, 1967), and in-depth studies on Mycobacterial species tuberculosis, avium, and smegmatis indicate that the concentrations of several cations in these bacteria are reduced after phagosomal engulfment, although Mg2+ itself was not detectable by the methods used (Wagner et al., 2005a, Wagner et al., 2005b). Nevertheless, potential transporters and chelators of Mg2+ from Mtb have been characterized and implicated in bacterial survival and pathogenesis (Blanc-Potard & Lafay, 2003, Buchmeier et al., 2000, Agranoff & Krishna, 2004, Wagner et al., 2005b), suggesting that depletion of Mg2+ in the phagosome may play a role in regulating pathogenesis. Indeed, other intracellular bacterial pathogens such as Salmonella and Brucella have been shown to respond to Mg2+-depletion levels similar to those utilized here (Lavigne et al., 2005, Rang et al., 2007) and genes believed to be involved in intraphagosomal survival and nutrient scavenging in Salmonella and Brucella are also found in Mtb (Buchmeier et al., 2000, Lavigne et al., 2005, Rang et al., 2007). Thus, we hypothesized that the Mg2+ depletion occurring upon phagosomal uptake provides a biochemical regulatory mechanism that activates MtHPS and triggers isoTb biosynthesis (Mann et al., 2009a).

The results reported here demonstrate that Mg2+ depletion does trigger isoTb production in Mtb. Preliminary studies in E. coli engineered to produce the HPP product of MtHPS demonstrated that changes in external/environmental Mg2+ levels can rapidly regulate metabolic flux within bacteria (Figure 2), despite no change in MtHPS protein levels. Studies with Mtb itself further supported Mg2+-depletion triggered production of isoTb via a biochemical mechanism (Table 1). In particular, transferring Mtb from high Mg2+ media to media containing ‘phagosome-like’ low Mg2+ levels, triggered not only a ~10-fold increase in HPP levels, but also the production of easily measureable isoTb (Figure 3), with an overall ~20-fold increase in biosynthesized diterpenoids (Figure 4). This was observed regardless of upstream promoter (native or recombinant), consistent with the lack of effect from Mg2+-depletion on Rv3377c and Rv3378c transcripts in wild type Mtb (Figure S1), and indicative of a biochemical regulatory mechanism. Notably, continuous growth at low concentrations of Mg2+ failed to result in a similar chemotype, as Mtb simply grown in a low Mg2+ environment do produce a small amount of HPP and isoTb, but deplete GGPP precursor levels in the process (Table 1). This indicates that it is not simply low Mg2+ levels, but the depletion of Mg2+ that occurs during phagocytosis which enables flux towards such bioactive diterpenoid metabolism, triggering production of the immune modulating isoTb (i.e., via activation of MtHPS activity), as well as increasing overall flux, providing a physiologically relevant regulatory mechanism, and further supporting a role for isoTb in the Mtb infection process (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proposed regulation of isotuberculosinol biosynthesis during phagosomal engulfment.

During infection, Mtb (purple) is compartmentalized within the phagosome (light grey) of the macrophage (dark grey). IsoTb is known to interfere with early stages of phagosomal maturation, which prevents later lysosomal (greyscale) fusion and bactericidal activity. IsoTb biosynthesis is inhibited by high Mg2+ concentration until phagosomal engulfment, when the bacteria are subjected to a shift to a low Mg2+ environment, releasing inhibition of the committed step of isoTb biosynthesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Kevin Pethe for construction of the Mtb CDC1551 ΔRv3377-78c strain and Rv3377c+Rv3378c expression plasmid. All the work with Mtb was carried out in the lab of Prof. David G. Russell (Cornell), whose support for these studies is gratefully acknowledged. Thus, this work was supported by grants from the NIH to D.G.R. (AI057086), as well as to R.J.P. (GM076324).

References

- Agranoff D, Krishna S. Metal ion transport and regulation in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Front Biosci. 2004;9:2996–3006. doi: 10.2741/1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardarov S, Bardarov S, Jr, Pavelka MS, Jr, Sambandamurthy V, Larsen M, Tufariello J, Chan J, Hatfull G, Jacobs WR., Jr Specialized transduction: an efficient method for generating marked and unmarked targeted gene disruptions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis, M. bovis BCG and M. smegmatis. Microbiology. 2002;148:3007–3017. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-10-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanc-Potard AB, Lafay B. MgtC as a horizontally-acquired virulence factor of intracellular bacterial pathogens: evidence from molecular phylogeny and comparative genomics. J Mol Evol. 2003;57:479–486. doi: 10.1007/s00239-003-2496-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmeier N, Blanc-Potard A, Ehrt S, Piddington D, Riley L, Groisman EA. A parallel intraphagosomal survival strategy shared by mycobacterium tuberculosis and Salmonella enterica. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:1375–1382. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01797.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke C, Croteau R. Interaction with the small subunit of geranyl diphosphate synthase modifies the chain length specificity of geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase to produce geranyl diphosphate. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3141–3149. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M105900200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao R, Yonghui Z, Mann FM, Huang C, Mukkamala D, Hudock MP, Mead M, Prisic S, Wang K, Lin F, Chang T, Peters RJ, Oldfield E. Diterpene Cyclases and the Nature of the Isoprene Fold. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Bioinformatics. 2010;78:2417–2432. doi: 10.1002/prot.22751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiang CY, Centis R, Migliori GB. Drug-resistant tuberculosis: past, present, future. Respirology. 2010;15:413–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2010.01738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua J, Vergne I, Master S, Deretic V. A tale of two lipids: Mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome maturation arrest. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:71–77. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2003.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr A, Wilderman PR, Determan M, Peters RJ. A modular approach for facile biosynthesis of labdane-related diterpenes. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:6684–6685. doi: 10.1021/ja071158n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deretic V, Singh S, Master S, Harris J, Roberts E, Kyei G, Davis A, de Haro S, Naylor J, Lee HH, Vergne I. Mycobacterium tuberculosis inhibition of phagolysosome biogenesis and autophagy as a host defence mechanism. Cell Microbiol. 2006;8:719–727. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2006.00705.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Effros RM, Peterson B, Casaburi R, Su J, Dunning M, Torday J, Biller J, Shaker R. Epithelial lining fluid solute concentrations in chronic obstructive lung disease patients and normal subjects. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1286–1292. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00362.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-del Portillo F, Foster JW, Maguire ME, Finlay BB. Characterization of the micro-environment of Salmonella typhimurium-containing vacuoles within MDCK epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:3289–3297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb02197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guenin-Mace L, Simeone R, Demangel C. Lipids of pathogenic Mycobacteria: contributions to virulence and host immune suppression. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2009;56:255–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1865-1682.2009.01072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurwitz C, Rosano CL. The intracellular concentration of bound and unbound magnesium ions in Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 1967;242:3719–3722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi SM, Pandey AK, Capite N, Fortune SM, Rubin EJ, Sassetti CM. Characterization of mycobacterial virulence genes through genetic interaction mapping. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11760–11765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603179103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Robbins SL. Robbins basic pathology. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2007. p. 946. p. xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Lavigne JP, O'Callaghan D, Blanc-Potard AB. Requirement of MgtC for Brucella suis intramacrophage growth: a potential mechanism shared by Salmonella enterica and Mycobacterium tuberculosis for adaptation to a low-Mg2+ environment. Infect Immun. 2005;73:3160–3163. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.3160-3163.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim EM, Rauzier J, Timm J, Torrea G, Murray A, Gicquel B, Portnoi D. Identification of mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA sequences encoding exported proteins by using phoA gene fusions. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:59–65. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.1.59-65.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann FM, Prisic S, Davenport EK, Determan MK, Coates RM, Peters RJ. A single residue switch for Mg2+-dependent inhibition characterizes plant class II diterpene cyclases from primary and secondary metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2010 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.123307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann FM, Prisic S, Hu H, Xu M, Coates RM, Peters RJ. Characterization and inhibition of a class II diterpene cyclase from Mycobacterium tuberculosis: implications for tuberculosis. J Biol Chem. 2009a;284:23574–23579. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.023788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann FM, Xu M, Chen X, Fulton DB, Russell DG, Peters RJ. Edaxadiene: a new bioactive diterpene from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Am Chem Soc. 2009b;131:17526–17527. doi: 10.1021/ja9019287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugel N, Mann FM, Hillwig ML, Peters RJ, Snider BB. Synthesis of (+/−)-Nosyberkol (Isotuberculosinol, Revised Structure of Edaxadiene) and (+/−)-Tuberculosinol. Org Lett. 12:2626–2629. doi: 10.1021/ol100832h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano C. Structure of Diterpene Produced by Rv3378c Gene Product from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Koryo Terupen oyobi Seiyu Kagaku ni kansuru Toronkai Koen Yoshishu (Japan) 2005;49:247–249. [Google Scholar]

- Nakano C, Hoshino T. Characterization of the Rv3377c gene product, a type-B diterpene cyclase, from the Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37 genome. Chembiochem. 2009;10:2060–2071. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakano C, Okamura T, Sato T, Dairi T, Hoshino T. Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv3377c encodes the diterpene cyclase for producing the halimane skeleton. Chem Commun (Camb) 2005:1016–1018. doi: 10.1039/b415346d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pethe K, Swenson DL, Alonso S, Anderson J, Wang C, Russell DG. Isolation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutants defective in the arrest of phagosome maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:13642–13647. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401657101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prach L, Kirby J, Keasling JD, Alber T. Diterpene production in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. FEBS J. 2010;277:3588–3595. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisic S, Peters RJ. Synergistic substrate inhibition of ent-copalyl diphosphate synthase: a potential feed-forward inhibition mechanism limiting gibberellin metabolism. Plant Physiol. 2007;144:445–454. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.095208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rang C, Alix E, Felix C, Heitz A, Tasse L, Blanc-Potard AB. Dual role of the MgtC virulence factor in host and non-host environments. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:605–622. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05542.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rengarajan J, Bloom BR, Rubin EJ. Genome-wide requirements for Mycobacterium tuberculosis adaptation and survival in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8327–8332. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503272102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohde KH, Abramovitch RB, Russell DG. Mycobacterium tuberculosis invasion of macrophages: linking bacterial gene expression to environmental cues. Cell Host Microbe. 2007;2:352–364. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG. Who puts the tubercle in tuberculosis? Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:39–47. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell DG, Barry CE, 3rd, Flynn JL. Tuberculosis: what we don't know can, and does, hurt us. Science. 2010;328:852–856. doi: 10.1126/science.1184784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander P, Meier A, Bottger EC. rpsL+: a dominant selectable marker for gene replacement in mycobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1995;16:991–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1995.tb02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shpitzer T, Bahar G, Feinmesser R, Nagler RM. A comprehensive salivary analysis for oral cancer diagnosis. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2007;133:613–617. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0207-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snapper SB, Lugosi L, Jekkel A, Melton RE, Kieser T, Bloom BR, Jacobs WR., Jr Lysogeny and transformation in mycobacteria: stable expression of foreign genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6987–6991. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.18.6987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spangler JE, Carson CA, Sorenson EJ. Synthesis enables a structural revision of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis-produced diterpene, edaxadiene. Chem. Sci. 2010;1:202–205. doi: 10.1039/C0SC00284D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart GR, Patel J, Robertson BD, Rae A, Young DB. Mycobacterial mutants with defective control of phagosomal acidification. PLoS Pathog. 2005;1:269–278. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0010033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stover CK, de la Cruz VF, Bansal GP, Hanson MS, Fuerst TR, Jacobs WR, Jr, Bloom BR. Use of recombinant BCG as a vaccine delivery vehicle. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1992;327:175–182. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-3410-5_19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergne I, Chua J, Singh SB, Deretic V. Cell biology of mycobacterium tuberculosis phagosome. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:367–394. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.114015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waddell SJ, Butcher PD. Microarray analysis of whole genome expression of intracellular Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:287–296. doi: 10.2174/156652407780598548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Maser J, Lai B, Cai Z, Barry CE, 3rd, Honer Zu Bentrup K, Russell DG, Bermudez LE. Elemental analysis of Mycobacterium avium-, Mycobacterium tuberculosis-, and Mycobacterium smegmatis-containing phagosomes indicates pathogen-induced microenvironments within the host cell's endosomal system. J Immunol. 2005a;174:1491–1500. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.3.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner D, Maser J, Moric I, Boechat N, Vogt S, Gicquel B, Lai B, Reyrat JM, Bermudez L. Changes of the phagosomal elemental concentrations by Mycobacterium tuberculosis Mramp. Microbiology. 2005b;151:323–332. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27213-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wards BJ. Evaluation of defined media suitable for isolation of auxotrophic mutants of mycobacteria. Journal of Basic Microbiology. 1996;36:355–362. doi: 10.1002/jobm.3620360510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.