Abstract

A new synthesis of 1,4-benzodiazepines and 1,4-benzodiazepin-5-ones is reported. The Pd-catalyzed coupling ofN-allyl-2-aminobenzylamine derivatives with aryl bromides affords the heterocyclic products in good yield, and substrates bearing allylic methyl groups are transformed toc is-2,3-disubstituted products with >20:1 dr.

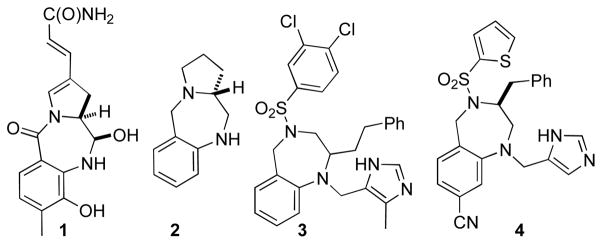

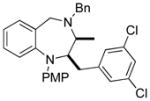

The benzodiazepine moiety is considered a privileged scaffold in medicinal chemistry, and many biologically active compounds bear this core.1 Although much effort has been directed towards the construction of unsaturated 1,4-benzodiazepines,2 fewer methods for the synthesis of saturated derivatives have been developed.3 This remains an important goal, as saturated 1,4-benzodiazepines are displayed in both natural products and pharmaceutical leads (Figure 1). For example, anthramycin(1) is a naturally occurring antitumor antibiotic,4 and analogs such as2 display antileishmanial activity.5 Benzodiazepine3 is an inhibitor of mitochondrial F1F0 ATP hydrolase, and has been examined as a potential candidate for treatment of cardiac ischemic conditions.6 In addition, benzodiazepine4 exhibits potent antitumor activity.7

Figure 1.

Biologically Active Saturated 1,4-Benzodiazepines

Our group has demonstrated that Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions between aryl or alkenyl halides and amines bearing pendant alkenes are effective for the synthesis of a broad array of five-8 and six-membered9 nitrogen heterocycles.10,11 However, our prior studies suggested that generation of seven-membered heterocycles via this strategy would be quite challenging, as both yields and reaction rates diminish with increasing ring size. This appears to be due to two main problems related to the mechanism of these transformations: as ring size increases, (a)Syn-aminopalladation of the alkene (Scheme 1),6→7, becomes more difficult due to entropic and stereoelectronic effects;9,10 and (b) competing formation of enamine side products9–10, via β-hydride elimination from intermediate7, becomes more problematic.9,10 The application of this methodology to the construction of seven-membered rings has not previously been demonstrated, and the formation of seven-membered nitrogen heterocycles via other metal-catalyzed alkene difunctionalization reactions is very rare.12 For example, Michael has described a conceptually related Pd(II)-catalyzed C–H activation/carboamination of aN-allyl-2-(aminomethyl)aniline derivative that afforded a 3-substituted 1,4-benzodiazepine. However, only a single example was reported, and the yield was modest (53%).12c

Scheme 1.

Mechanism and Competing Pathways

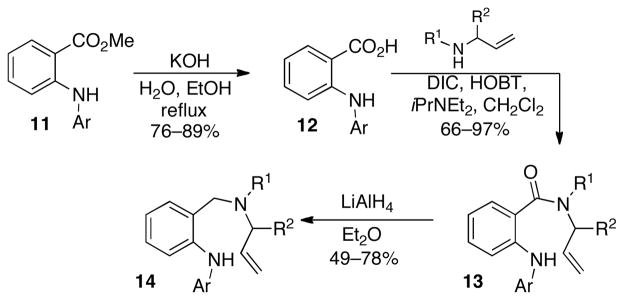

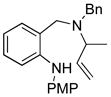

To determine the feasibility of forming seven-membered nitrogen heterocycles via Pd-catalyzed carboamination reactions, we elected to examine the synthesis of saturated 1,4-benzodiazepines. The substrates14 for these studies were prepared in three steps from readily available diarylamines11 (Scheme 2), which can be generated via Pd-catalyzedN-arylation of methyl-2-aminobenzoate.13 Saponification of the ester followed by coupling of the resulting acid12 with an allylic amine provided amides13. Reduction of the amides with LiAlH4 then afforded14 in moderate to good yield.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of Substrates

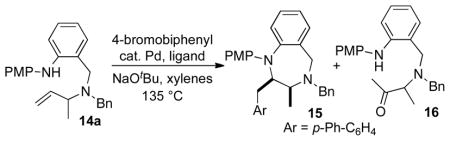

In our preliminary experiments we examined the Pd-catalyzed coupling of14a with 4-bromobiphenyl (Table 1). Our previous studies indicated that use of P(2-fur)3 as a ligand gave satisfactory results in six-membered ring forming reactions.9 However, use of this ligand in a reaction of14a provided desired product15 in a modest 58% NMR yield, along with 13% of ketone16. This side product presumably results from hydrolysis of an enamine (9, n = 3), which is generated via a competing β-hydride elimination pathway (Scheme 1). In order to minimize this side reaction, several other monodentate ligands were examined. Use of S-Phos failed to afford the desired product.14 Instead, competingN-arylation of the starting material was observed. However, after additional experimentation we discovered that a catalyst composed of PdCl2(MeCN)2 and PPh2Cy provided acceptable results (79% NMR yield), and upon isolation the desired product15 was obtained in 65% yield.

Table 1.

Optimization of Reaction Conditionsa

| ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pd-source | ligand | conversion (%) | yield15 (%)b | yield16 (%)b |

| Pd2(dba)3 | P(2-fur)3 | 91 | 58 | 13 |

| Pd2(dba)3 | S-Phos | 100 | 0 | 0c |

| Pd2(dba)3 | PCy2Ph | 100 | 46 | 8 |

| Pd2(dba)3 | PPh2Cy | 100 | 79 | 6 |

| PdCl2(MeCN)2 | PPh2Cy | 100 | 79 (65)d | 4 |

Conditions: 1.0 equiv14a, 2.0 equiv 4-bromobiphenyl, 2.0 equiv NaOtBu, 2 mol % [Pd], 4 mol % ligand. Product15 was formed with >20:1 dr.

Yields were determined by1H NMR analysis of crude reaction mixtures using phenanthrene as an internal standard.

The major product resulted fromN-arylation of the starting material.

Isolated yield (average of two experiments).

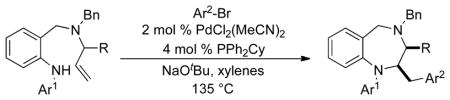

As shown in Table 2, the transformations were effective for a number of different substrate combinations. Aryl bromides bearing electron-donating or electron-withdrawing groups were coupled in good yields. However,N-arylation of the substrate was observed with highly electron-poor aryl bromides such as 4-bromo-2-fluorobenzonitrile. In most cases reactions were also effective for aryl bromides bearingo-alkyl substituents (entries 3, 10–11) including the very hindered 2,4,6-triisopropylbromobenzene (entry 11). However, no reaction was observed in the attempted coupling of 1-bromo-2-chlorobenzene with14a, and no desired product was obtained in a reaction between 1-bromopentamethylbenzene and14d; competing Heck arylation of the starting material was observed. Efforts to employ alkenyl bromides have thus far been unsuccessful.

Table 2.

Synthesis of Saturated 1,4-Benzodiazepinesa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%)b |

| 1 |

14b |

17 |

78 |

| 2 | 14b |

18 |

88 |

| 3 |

14c |

19 |

94 |

| 4 |

14d |

20 |

71 |

| 5 | 14d |

21 |

74 |

| 6 |

14e |

22 |

82c |

| 7 |

14a |

15 |

65 |

| 8 | 14a |

23 |

81c |

| 9 | 14a |

24 |

62 |

| 10 | 14a |

25 |

84 |

| 11 | 14a |

26 |

60 |

Conditions: Reactions were conducted on a 0.15 mmol scale using 1.0 equiv substrate, 2.0 equiv ArBr, 2.0 equiv NaOtBu, 2 mol % PdCl2(MeCN)2, 4 mol % PPh2Cy, xylenes (0.2 M), 135 °C, 18–24 h reaction time.

Isolated yield (average of two experiments). In all cases, 2,3-disubstituted products were obtained with >20:1 dr.

This product contained ca. 8% of ketone side product16.

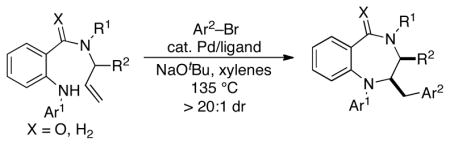

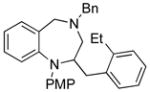

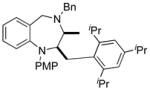

Although sterically bulky aryl bromides were reasonably well-tolerated, transformations of hindered diamine substrates proved to be more challenging. For example, substrates that contained an allylic-methyl group were stereoselectively transformed tocis-2,3-disubstituted products with >20:1 dr (entries 6–11). However, substrates bearing either larger substituents at the allylic position, or 1,1-disubstituted alkenes, failed to react. The electronic properties of theN-aryl group on the cyclizing nitrogen atom did not have a large influence on chemical yield, as substrates bearingN-phenyl-,N-PMP-, andN-(3,5-dichlorophenyl)-groups were all effectively converted to products in moderate to good yield. However, attempts to employ substrates with a benzyl group on the cyclizing nitrogen atom were unsuccessful.

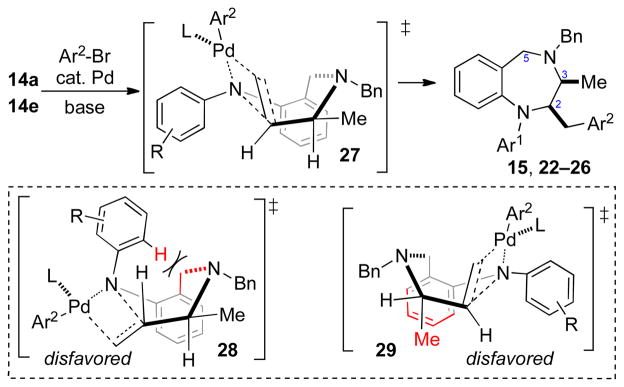

The stereochemical outcome of transformations involving substrates14a and14e is likely determined during C–N bond-forming alkene aminopalladation of an intermediate palladium(aryl)(amido) complex.8–10,15 Our prior studies have indicated that alkene aminopalladations proceed via organized transition states in which the alkene is eclipsed with the Pd–N bond. This suggests reactions of substrates14a and14e, which affordcis-2,3-disubstituted products, most likely occur via boat-like transition state27 (Scheme 3).16 Pathways leading to thetrans-disubstituted products appear to be high in energy. Chair-like transition state28 suffers from unfavorable steric interactions between theN-aryl group and the C5 methylene unit, and boat-like transition state29 is presumably disfavored due to the axial orientation of the C3 methyl group.

Scheme 3.

Origin of Observed Diastereoselectivity

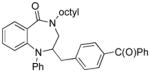

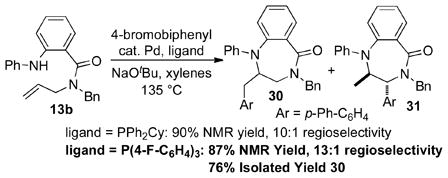

In order to further explore the scope of benzodiazepine-forming reactions, we examined the use of amides13 as substrates for the carboamination reactions. As shown in eq 1, the conditions that were optimized for transformations of diamine substrates provided good yields of30 in the coupling of13b with 4-bromobiphenyl, although small amounts of regioisomer31 were also obtained.17 After some additional optimization we found that use of P(4-F-C6H4)3 as ligand provided slightly improved selectivities. The regioisomer was separable by chromatography, and30 was obtained in 76% isolated yield. These modified conditions proved to be useful for the coupling of amides13b,13d, and13f with a number of different aryl bromides (Table 3). However, efforts to employ an amide substrate bearing an allylic methyl group were unsuccessful; complex mixtures of regioisomers were obtained.

Table 3.

Synthesis of 1,4-Benzodiazepin-5-one Productsa

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| entry | substrate | product | yield (%)b |

| 1 |

13b |

32 |

67 |

| 2 | 13b |

33 |

62 |

| 3 |

13d |

34 |

74 |

| 4 | 13d |

35 |

48 |

| 5 |

13f |

36 |

70 |

| 6 | 13f |

37 |

77 |

Conditions: Reactions were conducted on a 0.15 mmol scale using 1.0 equiv substrate, 2.0 equiv ArBr, 2.0 equiv NaOtBu, 1 mol % Pd2(dba)3, 4 mol % P(4-F-C6H4)3, xylenes (0.2 M), 135 °C, 18–24 h reaction time.

Isolated yield (average of two experiments).

|

(1) |

In conclusion we have developed an efficient entry into saturated 1,4-benzodiazepines and 1,4-benzodiazepin-5-ones via Pd-catalyzed alkene carboamination reactions. The method is effective for a variety of different aryl bromide coupling partners, andcis-2,3-disubstituted 1,4-benzodiazepines are formed with >20:1 dr. These transformations are rare examples of 7-membered ring-forming alkene difunctionalization reactions. Further studies toward enantioselective synthesis of 1,4-benzodiazepines and application of this strategy to biologically active targets are currently in progress.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the NIH-NIGMS for financial support of this work (GM-071650). Additional funding was provided by GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, and Eli Lilly. JDN acknowledges the U.S. Department of Education GAANN program for fellowship support. ASA was a participant in the NSF-REU program at the University of Michigan. The authors thank Mr. Daniel Miller (University of Michigan) for conducting preliminary experiments in this area.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available Experimental procedures, characterization data for all new compounds, descriptions of stereochemical assignments, and copies of1H and13C NMR spectra for all new compounds reported in the text. This material is available free of charge via the Internet athttp://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Costantino L, Barlocco D. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reviews: Horton DA, Bourne GT, Smythe ML. Chem Rev. 2003;103:893. doi: 10.1021/cr020033s.Ellman JA. Acc Chem Res. 1996;29:132.

- 3.For recent examples, see: Donald JR, Martin SF. Org Lett. 2011;13:852. doi: 10.1021/ol1028404.Sakai N, Watanabe A, Ikeda R, Nakaike Y, Konakahara T. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:8837.Mishra JK, Samanta K, Jain M, Dikshit M, Panda G. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2010;20:244. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2009.10.126.Rujirawanich J, Gallagher T. Org Lett. 2009;11:5494. doi: 10.1021/ol9023453.Yar M, McGarrigle EM, Aggarwal VK. Org Lett. 2009;11:257. doi: 10.1021/ol8023727.Wang J-Y, Guo X-F, Wang D-X, Huang Z-T, Wang M-X. J Org Chem. 2008;73:1979. doi: 10.1021/jo7024306.

- 4.Leimgruber W, Stefanovic V, Schenker F, Karr A, Berger J. J Am Chem Soc. 1965;87:5791. doi: 10.1021/ja00952a050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clark RL, Carter KC, Mullen AB, Coxon GD, Owusu-Dapaah G, McFarlane E, Thi MDD, Grant MH, Tettey JNA, Mackay SP. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2007;17:624. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2006.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hamann LG, Ding CZ, Miller AV, Madsen CS, Wang P, Stein PD, Pudzianowski AT, Green DW, Monshizadegan H, Atwal KS. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14:1031. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2003.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Hunt JT, Ding CZ, Batorsky R, Bednarz M, Bhide R, Cho Y, Chong S, Chao S, Gullo-Brown J, Guo P, Kim SH, Lee FYF, Leftheris K, Miller A, Mitt T, Patel M, Penhallow BA, Ricca C, Rose WC, Schmidt R, Slusarchyk WA, Vite G, Manne V. J Med Chem. 2000;43:3587. doi: 10.1021/jm000248z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Johnston SRD. IDrugs. 2003;6:72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pyrrolidines: Ney JE, Wolfe JP. Angew Chem, Int Ed. 2004;43:3605. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460060.Bertrand MB, Neukom JD, Wolfe JP. J Org Chem. 2008;73:8851. doi: 10.1021/jo801631v.Lemen GS, Wolfe JP. Org Lett. 2010;12:2322. doi: 10.1021/ol1006828.Pyrazolidines: Giampietro NC, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2008;130:12907. doi: 10.1021/ja8050487.Isoxazolidines: Lemen GS, Giampietro NC, Hay MB, Wolfe JP. J Org Chem. 2009;74:2533. doi: 10.1021/jo8027399.Imidazolidin-2-ones: Fritz JA, Wolfe JP. Tetrahedron. 2008;64:6838. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2008.04.015.

- 9.Piperazines: Nakhla JS, Schultz DM, Wolfe JP. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:6549. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.017.Morpholines: Leathen ML, Rosen BR, Wolfe JP. J Org Chem. 2009;74:5107. doi: 10.1021/jo9007223.

- 10.Reviews: Wolfe JP. Eur J Org Chem. 2007:571.Wolfe JP. Synlett. 2008:2913.

- 11.For Cu- or Au-catalyzed carboamination reactions that afford 2-(arylmethyl)pyrrolidines and related heterocycles, see: Chemler SR. Org Biomol Chem. 2009;7:3009. doi: 10.1039/B907743J.Zhang G, Cui L, Wang Y, Zhang L. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:1474. doi: 10.1021/ja909555d.For alkene carboamination reactions involving solvent C–H bond functionalization, see: Rosewall CF, Sibbald PA, Liskin DV, Michael FE. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9488. doi: 10.1021/ja9031659.

- 12.For hydroamination reactions see: Leitch DC, Payne PR, Dunbar CR, Schafer LL. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:18246. doi: 10.1021/ja906955b.Reznichenko AL, Hultzsch KC. Organometallics. 2010;29:24.Gagné MR, Stern CL, Marks TJ. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:275.For diamination reactions see: Streuff J, Hövelmann CH, Nieger M, Muñiz K. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14586. doi: 10.1021/ja055190y.For Cope-type hydroamination reactions, see: Roveda J-G, Clavette C, Hunt AD, Gorelsky SI, Whipp CJ, Beauchemin AM. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:8740. doi: 10.1021/ja902558j.

- 13.Wolfe JP, Buchwald SL. Tetrahedron Lett. 19977;38:6359. [Google Scholar]

- 14.S-Phos = 2-dicyclohexylphosphino-2′,6′-di-isopropoxy-1,1′-biphenyl.

- 15.(a) Neukom JD, Perch NS, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6276. doi: 10.1021/ja9102259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Neukom JD, Perch NS, Wolfe JP. Organometallics. 2011;30:1269. [Google Scholar]; (c) Hanley PS, Markovic D, Hartwig JF. J Am Chem Soc. 2010;132:6302. doi: 10.1021/ja102172m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.The major stereoisomers could also arise from chairlike transition states in which the methyl groups are oriented in axial positions. However, these transitions states appear to be higher in energy than 27 due to 1,3-diaxial interactions and unfavorable steric interactions between theN-aryl group and the C5 methylene similar to those illustrated in 28.

- 17.This regioisomer likely originates from competing β-hydride elimination processes similar to those illustrated in Scheme 1. For further discussion, see: Ney JE, Wolfe JP. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:8644. doi: 10.1021/ja0430346.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.