Abstract

Background

Pre-incarceration HIV transmission behaviors and current attitudes toward opioid substitution therapy (OST) among HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia have important implications for secondary HIV prevention efforts.

Methods

In June 2007, 102 HIV-infected male prisoners within 6 months of community-release were anonymously surveyed in Kota Bharu, Malaysia.

Results

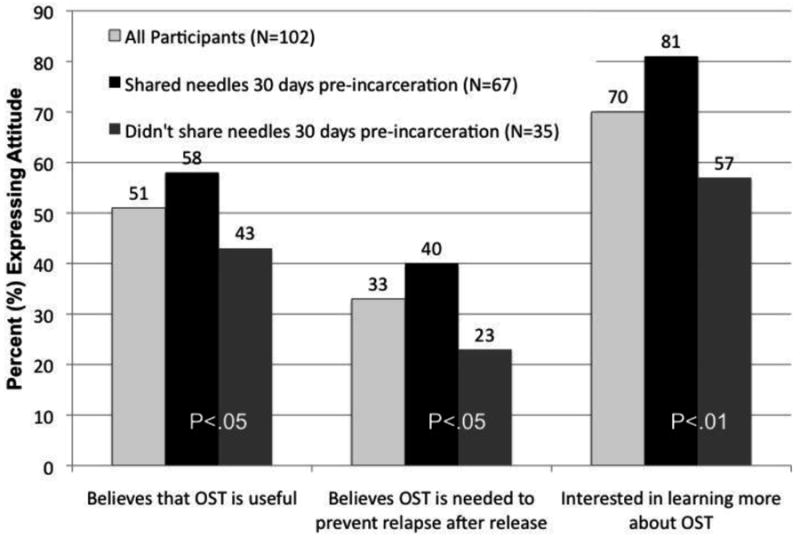

Nearly all subjects (95%) met criteria for opioid dependence. Overall, 66% of participants reported sharing needles, and 37% reported unprotected sex in the 30 days prior to incarceration. During this period, 77% reported injection drug use, with 71% injecting daily and 65% injecting more than one substance. Injection of buprenorphine (28%), benzodiazepines (28%) and methamphetamines (49%) was reported. Nearly all (97%) reporting unprotected sex did so with someone not known to be HIV-infected. While 51% believed that opioid substitution therapy (OST) would be helpful, only 33% believed they needed it to prevent relapse after prison release. Most participants (70%) expressed interest in learning more about OST. Those reporting the highest injection risks were more likely to believe OST would be helpful (p<.05), to believe that it was needed to prevent relapse post-release (p<.05), and to express interest in learning more about OST (p<.01).

Conclusions

Secondary HIV prevention among prisoners in Malaysia is crucial to reduce community HIV transmission after release. Effectively reducing HIV risk associated with opioid injection will require OST expansion, including social marketing to improve its acceptability and careful monitoring. Access to sterile injection equipment, particularly for non-opioid injectors, and behavioral interventions that reduce sexual risk will also be required.

Keywords: opioid substitution therapy, methadone, buprenorphine, Malaysia, prison, attitudes, injection drug use, HIV, needle and syringe exchange, secondary HIV prevention

1.0 Introduction

The HIV epidemic in Malaysia is primarily concentrated among injection drug users (IDUs). In 2008, injection drug use (IDU) accounted for more than half of all new HIV diagnoses in Malaysia (Kamarulzaman, 2009a, b; Mathers et al., 2008). Legal sanctions against drug users and a slow public health response prior to 2005 further marginalized IDUs and were unsuccessful in reducing the spread of HIV in Malaysia. In response to the failed attempt to control HIV/AIDS, the Malaysian government adopted harm reduction measures including needle and syringe exchange programs (NSEPs) and opioid substitution therapy (OST) to reduce HIV transmission among IDUs. In Malaysia, methadone was first introduced in 2005 in government-sponsored healthcare settings, whereas buprenorphine has been available but unmonitored in private office settings since 2002 (Noordin et al., 2008). Since this survey, which took place in June 2007, methadone maintenance therapy has been implemented in a small number of Malaysian prisons. Although these programs continue to expand, access to these critical harm reduction services remains insufficient, and IDU continues to fuel the HIV epidemic in Malaysia (Kamarulzaman, 2009b). Over the past few years, the face of Malaysia's HIV epidemic has rapidly changed. Sexual transmission is responsible for an increasing share of diagnosed HIV cases, accounting for close to 1/3 of new HIV infections in Malaysia in 2009 (AIDS/STD Section Disease Control Division, 2010).

Prisons around the world host a disproportionate share of HIV disease burden (Dolan et al., 2007). In Malaysia's prisons, where HIV testing is mandatory, the HIV prevalence is 6%, more than 10 times higher than in the general population (AIDS/STD Section Disease Control Division, 2010; UNAIDS, 2009; Wan-Mohamad, 2008). The concentration of HIV in Malaysian prisons can be attributed in part to the high prevalence of HIV among IDUs, many of whom pass through the criminal justice system for drug-related offenses (AIDS/STD Section Disease Control Division, 2010; Bergenstrom et al., 2009; Zahari et al., 2010). Prisons can provide a key opportunity to treat and link this marginalized population to HIV risk reduction interventions and health services such as condom distribution, sexual risk counseling, OST, and antiretroviral therapy (ART) (Altice et al., 2010; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Dolan et al., 2007; Kinlock et al., 2009; Maru et al., 2007; Springer and Altice, 2005; Springer et al., 2010).

In the time immediately after prison release, IDUs are at elevated risk for relapse to drug use and drug overdose (Binswanger et al., 2007; Kinlock et al., 2002; Nurco et al., 1991). They also may have limited access to ART and HIV care, poor HIV treatment outcomes, and increased HIV transmission behaviors (Baillargeon et al., 2009; Springer et al., 2010; Springer et al., 2004; Stephenson et al., 2005). OST, using methadone or buprenorphine, has been demonstrated to effectively reduce opioid use, injection-related risk behaviors, criminal activity, and incarceration (Barnett et al., 2009; Gowing et al., 2006; Keen et al., 2000; Mattick et al., 2009; Metzger and Zhang, 2010; Sorensen and Copeland, 2000; Werb et al., 2008). Moreover, for opioid-dependent HIV-infected individuals, OST increases access to HIV care, adherence to ART, and retention in care (Lucas et al., 2010; Metzger and Zhang, 2010; Roux et al., 2008; Spire et al., 2007). Without access to OST after prison release, HIV-infected opioid injectors may be at risk for relapsing to opioid injection (Binswanger et al., 2007) and potentially re-engaging in HIV transmission behaviors.

Positive attitudes and beliefs about OST have been associated with increased treatment retention (Kayman et al., 2006); however, attitudes toward OST among HIV-infected prisoners with a history of substance use disorders in Malaysia have not been previously examined. Better understanding HIV risk behaviors and attitudes toward OST among HIV-infected IDUs is essential for developing targeted interventions to engage this population in treatment and reduce HIV transmission in the community after release. In this study, we examine HIV transmission behaviors and injection drug use prior to incarceration as well as attitudes toward OST among HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia.

2.0 Methods

2.1 Patient Population and Study Design

The patient population, eligibility criteria, and recruitment have been previously described (Choi et al., 2010). In June 2007, 102 HIV-infected male prisoners were interviewed in Pengkalan Chepa Prison, a male correctional facility in Kota Bharu, the largest city in the state of Kelantan, Malaysia. Inclusion criteria included being HIV-infected, a current prisoner, and within 6 months of release to the community. The prison provided a list of all eligible candidates to the medical practitioner who then asked if the inmate was willing to participate in a 60-minute anonymous survey. All 102 eligible inmates who were approached agreed to participate in the study and provided informed consent. No identifying information was collected. No incentives were provided, and there were no negative consequences for not participating. This study was approved by the Medical Research and Ethics Committee at the University Malaya Medical Centre.

2.2. Study Measures

Trained interviewers administered the survey in Bahasa Malaysia. Survey sections included sexual and drug-related HIV risk behaviors in the 30 days prior to current incarceration, attitudes toward drug treatment, and post-release plans. Due to ethical and administrative concerns, this study did not collect data on injection and sexual behaviors during incarceration. Additional data on stigma and perceived re-entry challenges are reported elsewhere (Choi et al., 2010). Participants were classified as opioid-dependent based on meeting DSM-IV criteria in the 12 months prior to current incarceration. Participants were classified as opioid-dependent based on meeting DSM-IV criteria using the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.) in the 12 months prior to current incarceration (Sheehan et al., 1998).

2.3 Data Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using STATA, version 10.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX). Independent sample t-tests were utilized to determine differences in attitudes between those who reported sharing needles or syringes in the 30 days prior to their current incarceration and those who did not. Multivariate logistic models were constructed to determine the adjusted odds ratios for predictors of specific attitudes toward OST. A p-value of <0.10 from bivariate logistic analyses was used to enter the multivariate model. A backward elimination strategy was employed to fit the multivariate logistic regression model so that all remaining covariates were significant at the <0.05 level.

3.0 Results

3.1 Participant Demographic, HIV and Drug Use Characteristics in 30 Days Prior to Current Incarceration

Table 1 describes the overall characteristics, HIV experience, pre-incarceration drug use, and drug treatment history of all 102 HIV-infected male prisoners included in the study. Most participants reported previous incarcerations (76%) and stays within mandatory drug treatment facilities (54%), were currently incarcerated a median of 7 months, knew their HIV status for a median of 25 months and received their initial HIV diagnosis within a prison setting (64%); only 2 participants had ever received ART.

Table 1. Participant demographic, HIV and drug use experiences (n=102).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Mean age in years (Range 23-60) | 33 |

| Ethnicity | |

| Malay | 98 (96.1) |

| Other | 4 (3.9) |

| Education* | |

| No formal education | 9 (8.8) |

| Primary | 12 (11.8) |

| Lower secondary | 46 (45.1) |

| Higher secondary or higher | 35 (34.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 19 (18.6) |

| Single, Separated or Widowed | 83 (81.4) |

| Incarceration history | |

| Any previous incarcerations | 77 (75.5) |

| Median number of previous incarcerations (Range 0-10) | 2 |

| Median duration of current incarceration (months) | 7 |

| Previous detentions in compulsory rehabilitation center | |

| Any | 55 (53.9) |

| Median (Range 0-6) | 1 |

| Resided with family before incarceration | 77 (75.5) |

| Median number of months since HIV diagnosis (Range 0-252) | 25 |

| No response | 1 |

| Ever prescribed antiretroviral medications | 2 (2.0) |

| Opioid-dependent in 12 months prior to incarceration | 97 (95.1) |

| Substances injected in 30 days prior to incarceration | |

| Heroin | 44 (43.1) |

| Morphine | 62 (60.8) |

| Methamphetamine | 50 (49.0) |

| Benzodiazepine | 29 (28.4) |

| Buprenorphine and/or buprenorphine/naloxone | 28 (27.5) |

| Methadone | 3 (2.9) |

| Any opioid (heroin, morphine, buprenorphine or methadone) | 77 (75.5) |

| Only opioid | 26 (25.5) |

| More than 1 substance | 66 (64.7) |

| Lifetime history of using opioid substitution therapy | |

| Methadone only | 4 (3.9) |

| Buprenorphine only | 19 (18.6) |

| Both | 10 (9.8) |

| Any | 33 (32.4) |

Indicates highest level of education completed. Primary is up to Grade 6, lower secondary is up to Grade 9, higher secondary or higher is up to Grade 12 or college-level education

Nearly all (95%) met criteria for opioid dependence. The majority (76%) reported injecting opioids, including morphine (61%), heroin (43%), and buprenorphine (28%). Injection of methamphetamine (49%) and benzodiazepines (28%) was also common. Sixty-five percent of participants reported injecting more than one substance just prior to their current incarceration, while 26% reported injecting only opioids. Nearly one third (32%) of the sample reported ever entering an OST program before incarceration, with 14% having been prescribed methadone, 28% buprenorphine, and 10% both.

3.2 HIV Transmission Behaviors in 30 Days Prior to Current Incarceration

Table 2 displays self-reported HIV transmission behaviors in the 30 days prior to the current incarceration. Thirty-eight participants (37%) reported unprotected vaginal or anal sex during that time period, of whom 37 (97%) reported unprotected sex with someone thought to be HIV-negative or someone of unknown HIV status, while 7 (18%) reported unprotected sex with someone believed or known to be HIV-infected. We did not find a statistically significant association between HIV sexual transmission behaviors and methamphetamine injection (data not shown).

Table 2. HIV transmission behaviors in 30 days prior to incarceration (n=102).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Reported unprotected vaginal or anal sex | 38 (37.3) |

| Mean number of episodes among those reporting (Range 1-90) | 11.8 |

| Types of unprotected sex partners* | |

| Primary partner | 27 (26.5) |

| Casual partner | 17 (16.7) |

| Paid or paying partner | 14 (13.7) |

| In exchange for drugs | 10 (9.8) |

| With someone thought to be HIV+ | 7 (6.9) |

| With someone thought to be HIV- or unknown | 37 (36.3) |

| Reported injection drug use | 79 (77.5) |

| Frequency of injection | |

| None | 23 (22.5) |

| Some days | 7 (6.9) |

| Daily | 72 (70.6) |

| Number of injections per day | |

| 0 | 24 (23.5) |

| 1 to 3 | 42 (41.2) |

| 4 or more | 36 (35.3) |

| Reported sharing needle or syringe | 67 (65.7) |

| Mean number of episodes among those reporting (Range 1-180) | 49.6 |

| Injected first and then shared needle or syringe with others | 66 (64.7) |

| Mean number of episodes among those reporting (Range 1-150) | 26.9 |

| Types of injection partners* | |

| Sexual partner | 4 (3.9) |

| Spouse | 0 (0) |

| Friend/acquaintance | 70 (68.6) |

| Stranger | 9 (8.8) |

| Drug dealer | 18 (17.6) |

| Other | 23 (22.6) |

Participants indicated multiple responses

IDU was common in the 30 days just prior to this incarceration, with 77% reporting IDU and 71% injecting daily. Among those who reporting IDU (n=79), the average number of injections per day was 3.8 (±2.5). Many participants also reported frequent engagement in high-risk injection practices. Among those who injected, 85% (67/79) reported sharing needles or syringes at least one time, 35% (28/79) reported sharing needles or syringes during at least half of their injections, and 19% (15/79) reported sharing needles or syringes every time they injected. Among those who injected in the 30-day pre-incarceration period, the median number of sharing episodes was 16 (mean 42±50.6, range 0-180); 32% reported 1-10 episodes of sharing their needle or syringe, 13% reported 11-30 episodes, and 41% reported 31 or more episodes.

Nearly two-thirds of all subjects (66%) and 84% of active IDUs reported injecting before their sharing partners with the same needle or syringe. Of those reporting IDU, 23% (18/79) reported injecting first and then passing a needle or syringe to others during at least half of their injection episodes, and 11% (9/79) reported doing so every time they injected. Participants reported using a needle or syringe first and then passing it to others a median of 5 times (mean 22.5±31.6) in the 30 days prior to incarceration.

3.3 Attitudes and Predictors of Attitudes Toward Opioid Substitution Therapy

Table 3 describes both positive and negative attitudes toward OST. Approximately half (51%) of the participants believed that OST would be helpful, of whom only 54% believed that OST after release would prevent relapse. Most (70%) expressed interest in learning more about OST options.

Table 3. Attitudes and beliefs toward opioid substitution therapy (n=102).

| n (%) | |

|---|---|

| Believe that opioid substitution therapy would be helpful | 52 (51.0) |

| Beliefs why opioid substitution therapy would be helpful* (n=52) | |

| Allow for continued but more controlled IDU with a normal life | 24 (46.1) |

| Prevent IDU | 20 (38.5) |

| Help to stay out of prison | 17 (32.7) |

| Help to become better person | 13 (25.0) |

| Take care of health issues | 12 (23.1) |

| Help to get a job and have financial stability | 12 (23.1) |

| Be more involved with family, friends | 11 (21.2) |

| Prevent all drug use | 9 (17.3) |

| Believe that opioid substitution therapy would not be helpful | 50 (49.0) |

| Beliefs why opioid substitution therapy would not be helpful* (n=50) | |

| Leads to methadone/buprenorphine addiction | 16 (32.0) |

| Need to stop on own | 14 (28.0) |

| Addiction best treated by religion | 7 (14.0) |

| Insufficient quantity of OST drugs provided | 1 (2.0) |

| Do not want to stop using drugs | 1 (2.0) |

| Drugs not needed to treat addiction | 0 (0) |

| Addiction best treated by counseling | 0 (0) |

| Other | 9 (18.0) |

| Perceived need for OST to prevent relapse after release | 34 (33.3) |

| Reasons for perceived need for OST to prevent relapse* (n=34) | |

| Understand how OST can help to treat addiction | 13 (38.2) |

| OST less stressful than heroin or other narcotics | 10 (29.4) |

| Tried buprenorphine or methadone on street, felt “normal” | 9 (26.5) |

| Relapsed previously and tried OST on own | 4 (11.8) |

Participants indicated multiple responses

Participants who believed that OST would be helpful reported believing so because it would allow them to stabilize and improve their lives by preventing IDU (20/52), controlling their drug use (24/52), stabilizing them to find employment (12/52), helping them to take care of their health (12/52), and allowing them to become more involved with family and friends (11/52). Among those not believing OST to be helpful (n=50), negative perceptions about OST reflected an abstinence-oriented approach to drug treatment. Most common among these perceptions was the concern that OST would lead to an addiction to methadone or buprenorphine (16/50) and the belief that they needed to stop using opioids on their own, without the assistance of OST (14/50).

Among those with prior OST experience, most individuals expressed satisfaction with their previous methadone (86%, 12/14) or buprenorphine (79%, 26/29) treatment. Nearly all subjects (93%) with prior OST experience responded that they would refer friends to OST. Having used OST previously was associated with interest in receiving OST to prevent relapse (OR=3.3, p<0.01) and in learning more about OST (OR=6.8, p<0.01) after release. Bivariate associations between predictor variables and attitudes toward OST are reported in Table 4.

Table 4. Bivariate associations between predictor variables and attitudes toward opioid substitution therapy (OST).

| Total (n) | Believe OST is helpful (n) | p-value | Wants OST to prevent relapse (n) | p-value | Interested in learning more about OST (n) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any previous incarcerations | 77 | 38 | 0.56 | 24 | 0.42 | 54 | 0.84 |

| Any previous compulsory rehabilitation | 55 | 26 | 0.42 | 17 | 0.57 | 38 | 0.90 |

| Friend died of HIV/AIDS | 30 | 16 | 0.76 | 8 | 0.36 | 26 | 0.02* |

| Lived with family prior to incarceration | 77 | 39 | 0.91 | 24 | 0.42 | 56 | 0.229 |

| Polysubstance injection | 66 | 35 | 0.58 | 25 | 0.19 | 52 | <0.01** |

| <25 months since HIV diagnosis | 50 | 24 | 0.56 | 18 | 0.58 | 36 | 0.61 |

| Age <33 years | 51 | 28 | 0.43 | 17 | 1 | 40 | 0.05* |

| ≥7 HIV symptoms | 52 | 28 | 0.56 | 19 | 0.48 | 41 | 0.04* |

| Married | 19 | 11 | 0.50 | 7 | 0.72 | 13 | 0.90 |

| Education | |||||||

| No Education | 9 | 3 | 0.64 | 3 | 0.30 | 5 | 0.67 |

| Primary | 12 | 6 | 3 | 7 | |||

| Lower Secondary | 46 | 24 | 12 | 33 | |||

| Higher Secondary or more | 35 | 19 | 16 | 26 | |||

| History of prior OST | 33 | 26 | <0.01** | 17 | <0.01** | 30 | <0.01** |

| Unprotected sex in 30 days before this incarceration | 38 | 21 | 0.51 | 10 | 0.25 | 30 | 0.11 |

| Shared needle or syringe in 30 days before this incarceration | 67 | 39 | 0.04* | 27 | 0.04* | 54 | <0.01** |

p<0.01

p<0.05

In multiple logistic regression, correlates of wanting to learn more about OST included sharing needles or syringes (AOR: 3.9, p<0.05), injecting more than one substance (AOR: 3.5, p<0.05), age (AOR: 0.9, p<0.05), and whether a close friend had died of AIDS (AOR: 10.2, p<0.01). Significant differences in attitudes between those who shared needles or syringes in the 30-day pre-incarceration period and those who did not are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Attitudes toward Opioid Substitution Therapy (OST) among all participants (n=102) and significant differences in attitudes between those who reported sharing needles or syringes (n=67) in the 30 days prior to this incarceration and those who did not (n=35).

4.0 Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to explore attitudes toward OST among HIV-infected prisoners. These findings have important implications for OST expansion and secondary HIV prevention in Malaysia and elsewhere. Among this HIV-infected sample, we identified disturbingly high rates of pre-incarceration sexual and injection-related HIV transmission behaviors. The finding that most subjects were recidivists to prison and had longstanding HIV infection that was greater than their current duration of incarceration, suggests that HIV risk behaviors were high subsequent to previous releases from prison. Without effective interventions to reduce these risk behaviors, individuals may return to the same behaviors they engaged in before incarceration and are therefore targets for risk reduction interventions (Copenhaver et al., 2009).

Despite potential underreporting of sexual behavior due to social desirability bias, more than a third (37%) of the sample reported unprotected sex just prior to this incarceration. Among our sample, there was little or no consistent serosorting, with 97% (37/38) reporting unprotected sex with someone thought to be HIV-negative or someone of unknown HIV status. This finding differs from reports in the U.S. where HIV-infected IDUs (40%) may selectively serosort (Mizuno et al., 2010). HIV prevention interventions that have been shown to reduce sexual transmission behaviors among HIV-infected and injection drug using populations should be adapted to the Malaysian context for prisoners transitioning to the community (Copenhaver et al., 2006; Crepaz et al., 2006; Semaan et al., 2002).

Reduction of injection-related HIV risk among opioid injectors can be achieved through properly dosed OST, but access to affordable, appropriate OST remains limited (Altice et al., 2010; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Metzger and Zhang, 2010; Wolfe et al., 2010). OST has the added benefit of retaining HIV-infected persons in care (Lucas 2010), improving adherence to ART, and enhancing virologic outcomes among HIV-infected IDUs (Altice et al., 2010; Lucas et al., 2010; Wolfe et al., 2010). In addition to limited availability, attitudes and beliefs toward OST may also be barriers to accessing treatment. Even though nearly all participants (95%) met criteria for opioid-dependence, only 51% believed that OST would be personally helpful, and 33% believed they needed OST to prevent relapse after release. Since relapse rates within one year of prison release can be as high as 85-90% for opioid-dependent individuals, and 76% of our sample had previously been incarcerated, it is possible that participants were overestimating their ability to abstain from opioid use (Kinlock et al., 2002; Nurco et al., 1991). This may be due in part to decades of abstinence-based treatment messages delivered in correctional facilities and compulsory rehabilitation centers in Malaysia. Part of this discrepancy may also be due to a lack of accurate knowledge about OST, since it was still a relatively new treatment modality in Malaysia when this study was conducted.

Despite limited perceived need for OST, the majority of participants (70%) expressed interest in learning more about OST. Educational and social marketing campaigns may increase acceptance of OST programs in Malaysia by promoting a medical treatment approach rather than abstinence for chronic, opioid-dependent IDUs. Importantly, most of those with previous OST experience (93%) would refer friends to methadone or buprenorphine treatment, suggesting a possible role for peer education in facilitating OST acceptance and expansion.

One salient finding for secondary HIV prevention is that those reporting the highest injection-related HIV transmission behaviors were the ones with the most favorable attitudes toward OST. Specifically, those sharing injection equipment pre-incarceration were more likely to think OST is helpful, to want OST post-release to prevent relapse, and to be interested in learning about receiving OST post-release. These findings were confirmed after controlling for other covariates. Those who share injection equipment may be more knowledgeable about the beneficial effects of OST. These positive attitudes toward OST may be explained by targeted OST information campaigns or by information exchange through social networks of injection partners, some of whom may have used OST. Given the increased positive attitudes toward OST among those with previous OST experience, it is possible that those who have taken OST are informally acting as peer educators and disseminating information about the therapeutic value of OST.

Positive attitudes toward methadone have been shown to be associated with longer retention in treatment, which in turn is associated with better social and health outcomes (Corsi et al., 2009; Karow et al.; Kayman et al., 2006; Kimber et al.; Xiao et al., 2010). The findings from this study are encouraging and demonstrate the potential for uptake of OST among individuals most at risk for transmitting HIV.

Although OST has been documented to markedly reduce opioid injection and HIV transmission (Metzger et al., 1998), other data from this study support the need for improving OST prescription practices and integrating OST with other harm reduction activities. Over one-quarter (28%) of subjects reported injection of prescribed OST medications. This was primarily reported among those who were previously on OST (20/29), likely representing misuse of medications prescribed for treatment. Most of the OST injection was buprenorphine, and previous studies of buprenorphine injectors in Malaysia confirm that this medication is usually purchased from private practice physicians and was largely unregulated in 2007 (Bruce et al., 2008; Bruce et al., 2009). More recently, buprenorphine abuse appears reduced after the institution of more stringent regulations on the prescription and dispensation of buprenorphine in private office settings (Vicknasingam et al., 2010). Making NSEPs available within or near OST programs may, however, be one way to reduce HIV transmission among individuals on OST who do not completely stop injecting.

The use of multiple substances has been associated with poor drug treatment outcomes among individuals on OST (Brands et al., 2008). A minority (28%) of the sample injected benzodiazepines, and nearly half (49%) injected methamphetamines. While OST may effectively reduce opioid use, it will not address the injection of other substances such as benzodiazepines and methamphetamines. In the absence of effective treatments for benzodiazepine- and methamphetamine-related disorders, OST combined with NSEPs and behavioral interventions will likely be needed to more fully address injection-related HIV transmission behaviors in Malaysia (Copenhaver et al., 2007; Degenhardt et al., 2010; Rawson et al., 2008).

Despite the Malaysian government's goal to treat all HIV-infected individuals meeting clinical criteria for treatment, access to appropriate HIV/AIDS care is scant. Only 2% of our sample had ever been prescribed ART. Among HIV-infected persons, ART has been demonstrated to lower HIV-1 RNA levels and reduce HIV incidence even if high risk HIV behaviors persist (Brands et al., 2008; Granich et al., 2009; Lingappa et al.; Weber et al., 2009). Provision of ART for all HIV-infected patients meeting clinical criteria, irrespective of drug use or incarceration status, is not only a human rights imperative, but a central component of secondary HIV prevention efforts.

Though several important findings emerged from our analysis, this study is limited by the recruitment from a single correctional institution and a relatively small sample size. These results therefore may not be representative of other HIV-infected prisoners in Malaysia or elsewhere. Social desirability bias may have led to underreporting of drug use and sexual behaviors, especially since extramarital sex is strongly discouraged in Malaysian society (Kamarulzaman and Saifuddeen, 2009). Although we assessed a range of factors associated with our outcomes of interest, a 60-minute survey may have been insufficient to elicit all potentially confounding covariates. Notwithstanding these limitations, our results have important implications for secondary prevention strategies for HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia and potentially in other criminal justice settings.

5.0 Conclusions

High rates of pre-incarceration sexual and injection-related HIV transmission behaviors among HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia illustrate the need for improved secondary HIV prevention efforts. The concentration of HIV-infected IDUs in the criminal justice system makes incarceration and the period immediately following release an ideal opportunity to implement OST, NSEPs, and other HIV risk reduction interventions. Access to NSEPs and evidence-based treatment for benzodiazepine and methamphetamine dependence will be particularly important for those who inject non-opioids and cannot achieve maximal benefit from OST alone. Successful implementation of these programs will require effective transitional care to the community and has the potential to profoundly impact community levels of HIV transmission among HIV-infected persons who are released from prison. In light of these findings, when designing OST programs, policymakers should consider employing peer education modalities and targeting those at highest risk for injection-related HIV transmission.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- AIDS/STD Section Disease Control Division, M.M.o H., Government of Malaysia . UNGASS Country Progress Report: Malaysia. Petaling Jaya: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Altice FL, Kamarulzaman A, Soriano VV, Schechter M, Friedland GH. Treatment of medical, psychiatric, and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. Lancet. 2010;376:59–79. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60829-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, Paar DP. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA. 2009;301:848–857. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnett PG, Sorensen JL, Wong W, Haug NA, Hall SM. Effect of incentives for medication adherence on health care use and costs in methadone patients with HIV. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;100:115–121. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergenstrom A, Kamarulzaman A, Khalib AM. Malaysia Country Advocacy Brief: Injecting Drug Use and HIV. UNODC, UNAIDS; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD. Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brands B, Blake J, Marsh DC, Sproule B, Jeyapalan R, Li S. The impact of benzodiazepine use on methadone maintenance treatment outcomes. J Addict Dis. 2008;27:37–48. doi: 10.1080/10550880802122620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Govindasamy S, Sylla L, Haddad MS, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Case series of buprenorphine injectors in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2008;34:511–517. doi: 10.1080/00952990802122259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce RD, Govindasamy S, Sylla L, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Lack of reduction in buprenorphine injection after introduction of co-formulated buprenorphine/naloxone to the Malaysian market. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:68–72. doi: 10.1080/00952990802585406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi P, Kavasery R, Desai MM, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Prevalence and correlates of community re-entry challenges faced by HIV-infected male prisoners in Malaysia. Int J STD AIDS. 2010;21:416–423. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2009.009180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver M, Chowdhury S, Altice FL. Adaptation of an evidence-based intervention targeting HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community: the process and outcome of formative research for the Positive Living Using Safety (PLUS) intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:277–287. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver MM, Johnson BT, Lee IC, Harman JJ, Carey MP. Behavioral HIV risk reduction among people who inject drugs: meta-analytic evidence of efficacy. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2006;31:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver MM, Lee IC, Margolin A. Successfully integrating an HIV risk reduction intervention into a community-based substance abuse treatment program. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2007;33:109–120. doi: 10.1080/00952990601087463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsi KF, Lehman WK, Booth RE. The effect of methadone maintenance on positive outcomes for opiate injection drug users. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:120–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crepaz N, Lyles CM, Wolitski RJ, Passin WF, Rama SM, Herbst JH, Purcell DW, Malow RM, Stall R. Do prevention interventions reduce HIV risk behaviours among people living with HIV? A meta-analytic review of controlled trials. AIDS. 2006;20:143–157. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000196166.48518.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt L, Mathers B, Vickerman P, Rhodes T, Latkin C, Hickman M. Prevention of HIV infection for people who inject drugs: why individual, structural, and combination approaches are needed. Lancet. 2010;376:285–301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60742-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan K, Kite B, Black E, Aceijas C, Stimson GV. HIV in prison in low-income and middle-income countries. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:32–41. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(06)70685-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowing LR, Farrell M, Bornemann R, Sullivan LE, Ali RL. Brief report: Methadone treatment of injecting opioid users for prevention of HIV infection. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21:193–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00287.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granich RM, Gilks CF, Dye C, De Cock KM, Williams BG. Universal voluntary HIV testing with immediate antiretroviral therapy as a strategy for elimination of HIV transmission: a mathematical model. Lancet. 2009;373:48–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61697-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman A. Impact of HIV prevention programs on drug users in Malaysia. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009a;52:S17–S19. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181bbc9af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman A. Rolling Out the National Harm Reduction Programme in Malaysia. Presentation at the symposium organised by the United Nations Regional Task Force on Injecting Drug Use and HIV/AIDS for Asia and the Pacific. Proceedings of the In 9th International Congress on AIDS in Asia and the Pacific.2009b. [Google Scholar]

- Kamarulzaman A, Saifuddeen SM. Islam and harm reduction. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;21:115–118. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2009.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karow A, Reimer J, Schafer I, Krausz M, Haasen C, Verthein U. Quality of life under maintenance treatment with heroin versus methadone in patients with opioid dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;112:209–215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayman DJ, Goldstein MF, Deren S, Rosenblum A. Predicting treatment retention with a brief “opinions about methadone” scale. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2006;38:93–100. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2006.10399832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keen J, Rowse G, Mathers N, Campbell M, Seivewright N. Can methadone maintenance for heroin-dependent patients retained in general practice reduce criminal conviction rates and time spent in prison? Br J Gen Pract. 2000;50:48–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimber J, Copeland L, Hickman M, Macleod J, McKenzie J, De Angelis D, Robertson JR. Survival and cessation in injecting drug users: prospective observational study of outcomes and effect of opiate substitution treatment. BMJ. 2010;341:c3172. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c3172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Battjes RJ, Schwartz RP. A novel opioid maintenance program for prisoners: preliminary findings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O'Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2009;37:277–285. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingappa JR, Hughes JP, Wang RS, Baeten JM, Celum C, Gray GE, Stevens WS, Donnell D, Campbell MS, Farquhar C, Essex M, Mullins JI, Coombs RW, Rees H, Corey L, Wald A. Estimating the impact of plasma HIV-1 RNA reductions on heterosexual HIV-1 transmission risk. PLoS One. 5:e12598. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas GM, Chaudhry A, Hsu J, Woodson T, Lau B, Olsen Y, Keruly JC, Fiellin DA, Finkelstein R, Barditch-Crovo P, Cook K, Moore RD. Clinic-based treatment of opioid-dependent HIV-infected patients versus referral to an opioid treatment program: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152:704–711. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-152-11-201006010-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maru DS, Basu S, Altice FL. HIV control efforts should directly address incarceration. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:568–569. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70190-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, Wodak A, Panda S, Tyndall M, Toufik A, Mattick RP. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372:1733–1745. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattick RP, Breen C, Kimber J, Davoli M. Methadone maintenance therapy versus no opioid replacement therapy for opioid dependence. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009:CD002209. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Navaline H, Woody GE. Drug abuse treatment as AIDS prevention. Public Health Rep. 1998;113 1:97–106. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metzger DS, Zhang Y. Drug treatment as HIV prevention: expanding treatment options. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2010;7:220–225. doi: 10.1007/s11904-010-0059-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno Y, Purcell DW, Latka MH, Metsch LR, Ding H, Gomez CA, Knowlton AR. Is sexual serosorting occurring among HIV-positive injection drug users? Comparison between those with HIV-positive partners only, HIV-negative partners only, and those with any partners of unknown status. AIDS Behav. 2010;14:92–102. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9548-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noordin NM, Merican MI, Rahman HA, Lee SS, Ramly R. Substitution treatment in Malaysia. Lancet. 2008;372:1149–1150. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN, Hanlon TE, Kinlock TW. Recent research on the relationship between illicit drug use and crime. Behav Sci Law. 1991;9:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Rawson RA, Gonzales R, Pearce V, Ang A, Marinelli-Casey P, Brummer J. Methamphetamine dependence and human immunodeficiency virus risk behavior. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2008;35:279–284. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2007.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux P, Carrieri MP, Villes V, Dellamonica P, Poizot-Martin I, Ravaux I, Spire B. The impact of methadone or buprenorphine treatment and ongoing injection on highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) adherence: evidence from the MANIF2000 cohort study. Addiction. 2008;103:1828–1836. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02323.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semaan S, Lauby J, Liebman J. Street and network sampling in evaluation studies of HIV risk-reduction interventions. AIDS Rev. 2002;4:213–223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, Sheehan KH, Amorim P, Janavs J, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Baker R, Dunbar GC. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): the development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998;59 20:22–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen JL, Copeland AL. Drug abuse treatment as an HIV prevention strategy: a review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000;59:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(99)00104-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spire B, Lucas GM, Carrieri MP. Adherence to HIV treatment among IDUs and the role of opioid substitution treatment (OST) Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:262–270. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2006.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Altice FL. Managing HIV/AIDS in correctional settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2005;2:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s11904-005-0011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Chen S, Altice FL. Improved HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes for released HIV-infected prisoners: the impact of buprenorphine treatment. J Urban Health. 2010;87:592–602. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;38:1754–1760. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public Health Rep. 2005;120:84–88. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UNAIDS Report on the global AIDS epidemic. 2008. [August 11, 2010];2009 http://www.unaids.org/en/KnowledgeCentre/HIVData/GlobalReport/2008/2008_Global_report.asp.

- Vicknasingam B, Mazlan M, Schottenfeld RS, Chawarski MC. Injection of buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone tablets in Malaysia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;111:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wan-Mohamad N. Initiating Methadone Maintenance Therapy (MMT) in Prisons in Malaysia. Proceedings of a Satellite Session on HIV prevention interventions for injecting drug users: Lessons learnt from Asia. UN Regional Task Force on Injecting Drug Use and HIV/AIDS for Asia and the Pacific. Proceedings of the 19th International Harm Reduction Association.2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weber R, Huber M, Rickenbach M, Furrer H, Elzi L, Hirschel B, Cavassini M, Bernasconi E, Schmid P, Ledergerber B, Study SHC. Uptake of and virological response to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected former and current injecting drug users and persons in an opiate substitution treatment programme: the Swiss HIV Cohort Study. HIV Medicine. 2009;10:407–416. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1293.2009.00701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werb D, Kerr T, Marsh D, Li K, Montaner J, Wood E. Effect of methadone treatment on incarceration rates among injection drug users. Eur Addict Res. 2008;14:143–149. doi: 10.1159/000130418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe D, Carrieri MP, Shepard D. Treatment and care for injecting drug users with HIV infection: a review of barriers and ways forward. Lancet. 2010;376:355–366. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60832-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao L, Wu Z, Luo W, Wei X. Quality of life of outpatients in methadone maintenance treatment clinics. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;53 1:S116–120. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181c7dfb5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahari MM, Hwan Bae W, Zainal NZ, Habil H, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Psychiatric and substance abuse comorbidity among HIV seropositive and HIV seronegative prisoners in Malaysia. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:31–38. doi: 10.3109/00952990903544828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]