Abstract

The p21 Rho-family of small GTPases are master regulators of actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. Their functions have been well characterized in terms of their effects toward various actin-modulating protein targets. However, more recent studies have shown that the dynamics of Rho GTPase activities are highly complex and tightly regulated in order to achieve their specific subcellular localization. Furthermore, these localized effects are highly dynamic, often spanning the time-scale of seconds, making the interpretation of traditional biochemical approaches inadequate to fully decipher these rapid mechanisms in vivo. Here, we provide an overview of Rho family GTPase biology, and introduce state-of-the-art approaches to study the dynamics of these important signaling proteins that ultimately coordinate the actin cytoskeleton rearrangements during cell migration.

Key words: Rho, dynamics, live-cell imaging, FRET, migration, actin, biosensors

Introduction

It has been over two decades since the Rho family of p21 small GTP-binding proteins were identified and associated with the direct regulation of actin cytoskeleton.1–5 Much has been described to date in relation to their regulatory roles on the dynamics of actin cytoskeleton rearrangements. Here, we summarize the pathways that Rho, Rac and Cdc42 GTPases regulate with respect to the actin cytoskeleton, and introduce the state-of-the-art approaches to decipher the dynamics of these Rho-family GTPase activations.

Rho GTPases and Regulation by Upstream Factors

The Rho-family of p21 small GTPases are critical to the regulation of a myriad of cellular functions including motility, mitosis, proliferation and apoptosis.6–12 Rho GTPases function as molecular switches1,13 and can interact with downstream effector molecules to propagate the signal transduction in their GTP-loaded “on” state. The intrinsic phosphatase activity hydrolyzes the GTP to GDP, turning the protein “off”. This process is accelerated by the interaction with GAPs (GTPase activating proteins).14 The interaction with GEFs (guanine-nucleotide exchange factors) facilitates the exchange of GDP to GTP.15,16 The relative affinity difference of the effector molecules from GTP versus GDP-loaded states of the Rho GTPase can be as much as 100-fold,17–19 resulting in a highly specific interaction with its pertinent signaling partner only in its GTP-bound activated state. Furthermore, GEF/GAP interactions take place directly at the same effector binding interfaces (switch I/II) of the Rho GTPase.20,21 The binding of GEF or GAP confers slight structural changes that act to: (1) displace the Mg+2 and release the bound GDP in exchange for GTP in the case of GEFs20 and (2) insert a water molecule into the catalytic pocket of the Rho GTPase to facilitate the hydrolysis of GTP into GDP by a factor of nearly 4,000 fold over the intrinsic phosphatase activity in the case of GAPs.22,23 An important consideration for the Rho GTPase and the associated upstream regulator interaction is the overexpression of the dominant negative (T17N Rac1 or Cdc42 or T19N RhoA) or the constitutively active (Q61L or G12V Rac1 and Cdc42 or Q63L or G14V RhoA) mutant versions of the Rho GTPase. This creates a situation in which these mutants sequester the upstream GEFs and GAPs.15 These effects are due to the high-affinity state of these mutant Rho GTPases toward upstream GEFs and GAPs, respectively. Rho GTPases that are in the Apo configuration (guanine nucleotide-free) have high affinity towards GEFs, while those in the GTP-loaded state have high affinity toward GAPs. This is a problem as upstream GEFs and GAPs can be and are typically not selective between the members of the isoforms of Rho GTPases,15 making the delineation of the phenotype impossible if more than one isoform of GTPases are involved.

Guanine-nucleotide dissociation inhibitors (GDIs) are another class of molecules that interact with Rho GTPases in the regulatory cycle.2,24–26 GDI binding to a Rho GTPase inhibits the dissociation of the guanine nucleotide27,28 and prevents activation of Rho GTPases. GDI has been shown to extract membrane-bound Rho GTPases that are post-translationally modified by the addition of a lipid moiety to the C-terminus.27,28 This post-translational modification includes almost all of small p21-GTPases except for GTPases of the Ran family.28 This lipid moiety interacts with the GDI through its insertion into the hydrophobic pocket formed by the immunoglobulin-like beta-sandwich of the GDI. The interaction also brings into contact the N-terminal regulatory portion of the GDI against the effector binding interface (GTP-regulated switch I and switch II regions) of the Rho GTPase,28 preventing any spurious binding of the Rho GTPase with its effectors. The binding of GDI to Rho GTPase at the plasma membrane causes the bound complex to be pulled into the cytoplasm. This shuttling of the Rho GTPase between membranes (active fraction) and the cytoplasm (inactive fraction) constitutes one of the major regulatory dynamics of Rho GTPases. The spatiotemporal regulation of GTPase-GDI interactions is an emerging field of study. New studies suggest that the phosphorylation of GDI and the Rho GTPase plays a key role in modulating the relative affinities towards each other.28–31 Various upstream kinases targeting GDI and Rho GTPases including Src,29 PKC,31 PKA,30 have been identified to be able to specifically modulate the affinity of GDI toward each member of the Rho GTPase family. Additional evidence supports the possibility that the GTP-loaded Rho GTPase may be sequestered by GDI though at a reduced efficiency.32 This mode of Rho GTPase regulation could further complicate the deciphering of the spatiotemporal dynamics of the Rho GTPase activation in living cells.

GTPase Isoforms, Classes Important for Motility

Traditionally, the Rho family GTPases, RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42 have been primarily associated with cytoskeleton rearrangements based on the seminal work by Hall and colleagues.2–7 Microinjection of the activated mutants of Rho GTPases into starved and quiescent Swiss3T3 cells induced dramatic actin cytoskeletal rearrangements where RhoA caused stress fiber and adhesion formation, Rac1 induced sheet-like lamellipodial protrusion and Cdc42 produced filopodial protrusions. Since these initial studies, various upstream and downstream pathways have been elucidated; however, the mechanism by which these pathways are coordinated in living cells and in real-time remains less characterized due to the technically challenging nature of observing multiple protein activities in vivo.

The Rho-subfamily of GTPases has been shown to regulate a variety of cytoskeletal dynamics.6–12,33–35 Based on in vitro biochemical observations, inhibitor assays or ectopic expression of a variety of mutants of Rho GTPases, it is very tempting to conclude that any one of the GTPases (Rac1, RhoA or Cdc42) could have distinct and isolated effects on cell motility in vivo.36 However, it appears more likely that these Rho GTPases exist in complex activation cascades with antagonistic regulatory mechanisms that result in coordinated effects with precise interrelationships between each family member in vivo.37,38 An example of this effect is the antagonism between Rac1 and RhoA (Fig. 1). Historically, Rac1 has been associated with lamellipodial protrusions or membrane ruffles following the microinjection of a constitutively active Rac1 into starved Swiss3T3 cells7,11 while microinjection of activated RhoA resulted in the formation of stress fibers, adhesion plaques and a contractile phenotype.6,9,10 More evidence suggesting a segregation of protrusive versus retractile signals came from the neuronal system where deactivation of RhoA led to the neurite growth cone extension while activation of RhoA caused its collapse.39,40 It has been hypothesized that the protrusive phenotype driven primarily by Rac1 must prevail at the leading edge and the contractile phenotype by RhoA primarily drives the tail retraction in locomoting cells.10,41–45 Observations of activated Rac1 at the leading edge and activated RhoA at the tail had been demonstrated in some cell systems.43,46 However, more recent studies of fibroblasts and cancer cells appear to indicate a more complex and dynamic pattern of Rac1/RhoA GTPase coordination that appears to be not only spatially but also temporally regulated at significantly finer time-scales within regions that undergo cytoskeletal rearrangements including protrusion, retraction, ruffling or macropinocytosis37,47–50 (Fig. 2). These recent observations support the idea that cytoskeletal dynamics and Rac1/RhoA activities are tightly coupled at subcellular levels.

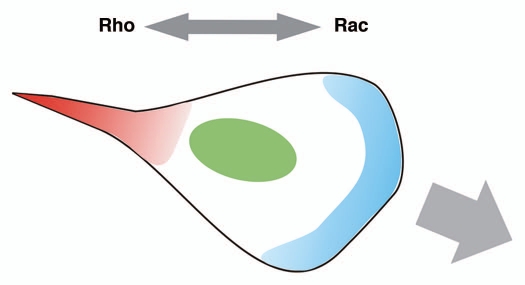

Figure 1.

Diagram showing the traditional view of Rac1 versus RhoA activities in migrating cells. RhoA was thought to be activated mainly at the retracting tail (red) to promote tail contraction, while Rac1 was thought to be activated at the front of the cell to promote lamellipodial protrusion (blue).

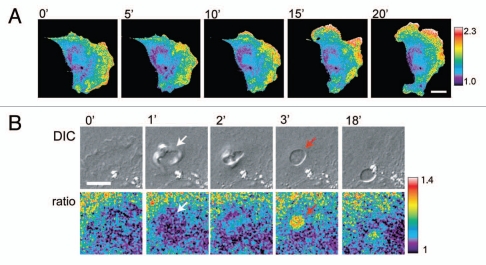

Figure 2.

Sample fluorescent biosensor data showing the complex activation patterns of RhoA at the leading edge (A) and in a subcellular structure of a macropinosome (B). Images taken from Pertz et al.48

Rho GTPase Downstream Targets

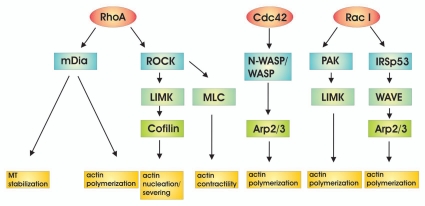

The downstream targets of Rho have been well described and include kinases, formins, families of WASp proteins, and other scaffolding molecules (Fig. 3). Of these major subclasses, the Rho-associated coiled-coil kinase1/2 (ROCK), the p21-activated kinase (PAK), the mammalian Diaphanous formin (mDia) and proteins of the WASp family including WASp, N-WASp and WAVE, have direct effects on actin cytoskeleton rearrangements pertinent to motility.

Figure 3.

Downstream effector targets of Rho family of GTPases.

RhoA, B and C activate the immediate downstream kinase target ROCK.51 ROCK has been shown to directly phosphorylate a number of actin cytoskeleton regulators including myosin light chain phosphatase and LIM kinase (LIMK).51,52 The direct phosphorylation of myosin light chain or of myosin light chain phosphatase has a immediate impact on the level of phosphorylated myosin light chain, which contributes to contractility.53 Activation of LIMK by ROCK has been linked to the phosphoregulation of ADF/cofilin.52,54–56 ADF/cofilin has been shown to be one of the key regulators of actin severing, nucleation and capping within the protrusive machinery.57–63

Cofilin-mediated actin nucleation through severing of preexisting actin fibers is an important regulatory mechanism through which cells regulate the protrusive dynamics of the leading edge.64–67 Cofilin is regulated by a direct phosphorylation at Ser3 through the LIMK.63 This phosphorylation is thought to form an intramolecular salt-bridge with a pair of Lys126/127 to block the actin binding interface, preventing its actin binding function (inactive).63 Furthermore, unphosphorylated (active) cofilin has been shown to bind to PIP2 as well as to cortactin,63 imparting an additional level of activity modulation through directly sequestering the activated cofilin. Feeding directly into this pathway, Rac1 and Cdc42 activate p21 activated kinase1 (PAK1), which also activates LIMK.68 The Slingshot and Chronophin family of phosphatases activated by Rac1 can dephosphorylate cofilin to activate it;69,70 however, how these multiple pathways are coordinated and in turn regulate ADF/cofilin through upstream Rho GTPases within the leading edge protrusions remains unknown.

Another critical downstream effector of RhoA, B and C isoforms is the Formin family of proteins. Formins produce straight, unbranched actin fibers through the formin homology domain 2 (FH2) that is responsible for the initiation of actin filament assembly.71 FH2 is persistently associated with the tip of the growing actin filament, accelerating the incorporation of actin monomers as well as protecting the ends from actin capping proteins.71–75 Formin homology 1 (FH1) delivers the profilin-bound actin monomers to the FH2 to incorporate them into the growing tip of the actin filament.73 These actin filaments are typically evident in actin stress fibers, filopodia, actin cables and cytokinetic actin rings.71 The mode of activation of formins typically involves binding of the upstream activated Rho GTPases which in turn displaces the autoinhibitory domain.71 This relaxes the autoinhibited and closed conformation, allowing for the FH1/FH2 to process the actin polymerization. Out of the identified 15 mammalian formins, mammalian Diaphanous formin (mDia) 1 and 2 have been studied the most to date in the context of cell motility.71 mDia1 has been shown to be activated by Rho isoforms. However, mDia2 also appears to be activated by Rac1 and Cdc42,76 further complicating the upstream signaling pathways that result in specific downstream actin cytoskeleton rearrangements in vivo. Interestingly, mDia1 through association with the microtubule end capping protein complex EB1/APC, has been shown to stabilize dynamic microtubule tips and to stabilize adhesions.77–79 mDia2 possesses a microtubule binding ability that is independent of its actin polymerization activity,77 directly tying the actin cytoskeleton rearrangements to the microtubule dynamics in migrating cells.

Rac1 and Cdc42 activate Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome family of proteins including WASP, N-WASP and WAVE1/2.80–85 WASP and N-WASP are thought to be directly activated by binding of Cdc42 and Rac1 to the CRIB motif within the GTPase binding domain and to be subsequently and cooperatively activated by interacting with PI(4,5)P2.86 These molecules exist in an autoinhibited, closed conformation where the C-terminal VCA motif binds to the GTPase binding domain (GBD) in the inactive state. Activated upstream Cdc42 or Rac1 competes against this auto-inhibition, releasing the VCA from the GBD. The opening of the molecule then allows binding of the Arp2/3 complex to the VCA motif and its subsequent activation of the Arp2/3 complex.83,86–89 However, the localization of WASP and N-WASP can also be regulated by the interaction with other binding partners including Grb2,90–92 likely targeting the molecule to sites of receptor stimulation and active actin cytoskeleton remodeling. Unlike WASP, WAVE proteins do not have a GBD domain86 and their activation requires binding of Rac1 to the adapter molecule IRSp53, followed by binding of this complex to the WAVE protein.93 Furthermore, binding of Abi1 appears also to be required for the activity of WAVE.94,95 WAVE has a C-terminal VCA motif that activates the Arp2/3 complex, promoting dendritic actin network formation.86

Methods to Study the Dynamics of Rho GTPases

Dominant negative (DN) and constitutively activated (CA) mutant versions of the Rho GTPases have been widely used in living cells to produce cell phenotypes that are strongly driven by these mutant Rho GTPases. However, these approaches require caution in interpreting the cell phenotype due to overwhelming effects of the DN and CA mutations.1,13,96 There are additional mutations that may not necessarily confer the DN or the CA effects, such as effector-binding mutations, GDI-binding and GEF/GAP binding mutants.97 The usage of these versions of Rho GTPase would necessitate an siRNA-knockdown/rescue approach to specifically remove the endogenous wild-type background. There are further observations that the KD of the endogenous Rho GTPase may cause a compensatory overexpression of other Rho GTPases in some systems.98

Immunofluorescence localizations of Rho family GTPases have been challenging due to their generally diffuse cytoplasmic distribution patterns and the nature of Rho GTPase regulation in which active/inactive material shuttles between the membrane and the cytoplasmic compartments. This shuttling often mobilizes only a small fraction of the total Rho GTPase population to the sites of activation.99 GFP-fusion of Rho GTPases has been used previously to describe the general localization patterns of various Rho GTPases and their mutants.100 However, this approach does not differentiate between active and GTP-loaded versus inactive and GDP-loaded GTPase localizations in vivo, and fails to capture the real-time transitions between such active versus inactive states in living cells.

Affinity precipitation of activated Rho GTPases using the GST-fusion of small binding domains derived from various downstream effector targets (i.e., RBD from Rhotekin or PBD from PAK1) has been the main workhorse of determining the cellular content of activated Rho GTPases.101,102 These approaches can pull down specifically activated Rho family GTPases and compare the active fraction to the total Rho GTPase on immunoblots. However, one must consider that this approach provides population averages and snapshot views of GTP-loading states in whole populations of cells. Since Rho GTPase activations are often rather subtle and highly localized to various subcellular compartments,100 isolation of peripheral protrusions from the cell body using porous filters can be used to address these issues.103 The second major consideration is the time-scale resolution in these assays. The dynamics of Rho GTPase activations in living cells are often in the time-scales of few seconds to tens of seconds, making the preparation of cell lysates difficult in order to resolve these finer time-scale events.

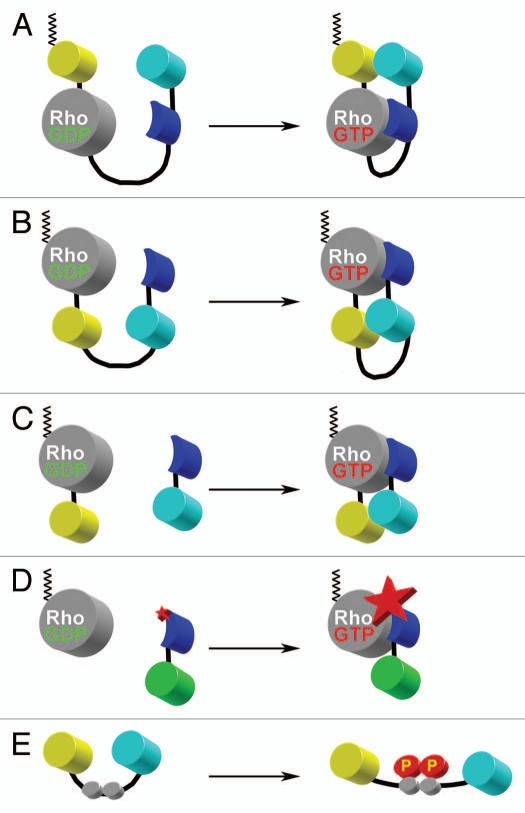

The direct visualization of proteins in their native environment has been a critical tool in cell biological studies for over two decades.104 The development of the fluorescent biosensors allowed the first observations of protein post-translational modification dynamics in living cells under native conditions.46–48,105–107 The applicability of biosensors was greatly expanded by the discovery of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) from the jellyfish Aequoria victoria108,109 and by the development of mutant versions of GFP with enhanced photo-physical properties that can undergo fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET). Non-radiative FRET between different spectral variants of fluorescent proteins is strongly dependent on the distance and orientation between the GFP mutants. This property can be used to design genetically encoded biosensors that report post-translational modifications and conformational changes, rather than simply tagging proteins to follow changes in their localization. There are now multiple biosensors available based on FRET between GFP mutants.110–115 (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic representations of various design approaches used in FRET biosensors. (A) Single-chain, genetically-encoded biosensor for Rho family GTPases based on the design of Raichu-sensors for Ras.135 This design places a CAAX box from K-Ras at the C-terminal end of the fluorescent protein to constitutively place the probe into the plasma membrane (depicted in black zig-zag lines). Upon activation of Rho GTPase through GDP-GTP exchange, the binding domain derived from a downstream effector target (blue) binds to the GTPase, changing the relative proximities of the FRET pair of yellow and cyan fluorescent proteins. (B) Single-chain, genetically-encoded biosensor for Rho GTPase.48 This design places the FRET pair of fluorescent proteins within the internal portion of the single-chain construction. This approach maintains the native C-terminus of the Rho GTPase where proper post-translational lipid modification can take place. This feature maintains the interaction between the GTPase and the guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor. This allows for the proper shuttling of the biosensor between the cytoplasm (inactive) and the plasma membrane (active), in a manner analogous to the endogenous protein. Upon activation of the GTPase through GDP-GTP exchange, the binding domain (blue) binds to activated Rho, changing the relative orientations between the cyan and yellow fluorescent proteins to affect FRET. (C) Bi-molecular, genetically encoded biosensor for Rho GTPases.37 This design separates the FRET donor and acceptor moieties into two molecules which must be expressed separately. While the quantitative analysis is more cumbersome due to non-equimolar distribution of the FRET donor and acceptor pairs, the total change in dynamic range can be much greater than any single-chain versions of the biosensor. (D) Solvent-sensitive dye-based biosensor for detecting the activity of an endogenous Rho GTPase.47 This approach uses an organic dye that changes the fluorescence emission intensity as a function of the local solvent polarity. By placing the dye within the binding domain (blue) derived from a downstream target protein, the binding of this biosensor to the activated, unlabeled, endogenous Rho GTPase causes the dye to change the fluorescence intensity of emission. By monitoring the ratio of this fluorescence emission intensity modulation over the non-responsive fluorescence (e.g., green fluorescent protein shown in green), one can monitor the effector-binding state of the Rho GTPase. (E) Substrate-based FRET biosensor for the kinase activity. The FRET pair of fluorescent proteins flank the phosphorylation motif of the target upstream kinase (gray circles). Upon phosphorylation, the conformation of the molecule is slightly altered and affects the FRET between the two fluorescent proteins. This approach can also include an appropriate binding site adjacent to the kinase phosphorylation motif for the upstream kinase of interest in order to improve the selectivity (not shown). The main caveat to this approach is that it is not as specific for the “kinase activity” because it simply monitors the balance of the relative upstream kinase and the local phosphatase activities in live-cell situations.

Factors Influencing FRET Efficiency

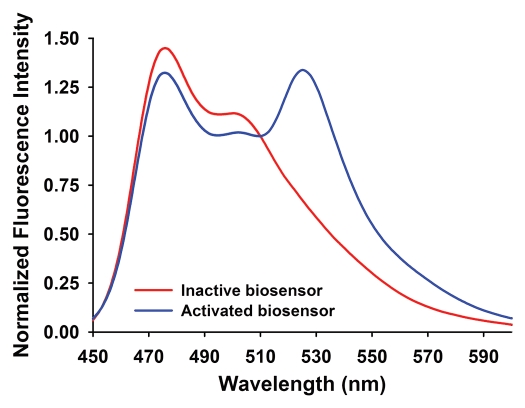

FRET is sensitive to both the distance and the orientation of the two fluorophores within the biosensor. When the fluorophores are sufficiently far apart or have orthogonal dipole orientations, excitation of the donor leads to the fluorescence emission from the donor rather than resulting in the FRET emission from the acceptor. However, when the distance is sufficiently small (typically, less than 10 nm), and the orientations of the FRET pair of fluorophores enable sufficient dipole-dipole coupling, there exists a finite probability that the excitation energy is transferred from the donor to the acceptor through a quantum mechanical process, leading to a decreased donor emission and an increased emission from the acceptor. This produces a characteristic FRET excitation/emission spectrum (Fig. 5), which is different from that of the donor or acceptor alone.

Figure 5.

Characteristic FRET emission response observed in spectrofluorometric measurements for a sample biosensor. The 525 nm emission peak is visible only when the biosensor is activated (blue line), due to FRET. When the biosensor is inactive, the FRET peak at 525 nm is substantially reduced (red line).

There has been a continuing evolution of useful GFP mutants suitable for FRET in living cells. Mutants incorporate different trade-offs between brightness, FRET efficiency, folding and maturation rates, photostability and the pH dependence of fluorescence characteristics.116,117 Higher brightness improves the overall signal to noise ratio in cells during imaging but is not an advantage if it comes at the cost of FRET efficiency (which affects the dynamic range or the difference between the activated and inactivated states of the biosensor).118 The enhanced Cyan and Citrine yellow fluorescent proteins (ECFP and CitYFP)117,119 are relatively fast maturing, pH stable, bright GFP mutants that have been useful in many FRET biosensors.118

In biosensors, activation of the targeted protein affects FRET efficiency by altering the distance and/or the orientation of the two fluorophores. FRET efficiency is sensitive to the distance between the pair of fluorophores by the inverse sixth dependence.120 Changes in the relative angular orientations of the dipoles produce a smaller but important effect. The dipole orientations of the fluorophores can be considered not to have an effect on the FRET efficiency only when both fluorophores are free to rotate isotropically during the excited state lifetime of the fluorophore. Therefore, a change in the rotational mobility or the fixed angle of the fluorophores in different biosensor states can also affect FRET.120,121 The fluorescent proteins are relatively large and do not rotate freely during a typical excited-state lifetime. Hence, in order to optimize the dipole-dipole coupling angle, approaches including circular permutation of fluorescent proteins122 have been extremely useful to reorient the attachment angles of the FRET pair of fluorophore dipole moments in relation to each other. One critical point is that effects of the fluorophore separation (linear displacement) versus the angular reorientation cannot be readily delineated in live-cell studies. Therefore, FRET changes should not be used to determine the precise distance between proteins but instead the extent of FRET produced by the fully active versus the inactive target protein. These values are then used to interpret the relative FRET changes and resulting activation state of the target proteins within cells.

Biosensors for Detecting Rho Family GTPase Activity

There are now several fluorescent biosensors available for detecting the Rho GTPase activity in living cells.46–48,123 Figure 4 shows several examples of these approaches. The major advantage of these biosensors is that they enable the direct visualization of protein “activation” (usually by way of effector-binding interactions) in the native condition of living cells and in real-time. Using optimized versions of the fluorescent proteins with superior photo-physical properties, it is now possible to observe these cells in extended time-lapse experiments, often spanning hours and capture events at subcellular resolutions.37,47–49

In order to observe the coordinate regulation of these Rho GTPase activities that are often very tightly coupled both in space and time, it would be highly informative to observe multiple Rho GTPase activities at the same time in a single living cell. One of the primary limitations of the FRET biosensors in living cells is the spectral overlap between multiple FRET pairs of fluorescent proteins if more than one set of biosensors is used at the same time. Recent attempts to overcome this problem involve using compatible pairs of fluorescent proteins including CFP/YFP and mOrange2/mCh combinations.124 However, these approaches require critical optical component design in order to minimize the spectral bleed-throughs between different channels of fluorescence. Newer techniques are beginning to emerge promising separations of multiple wavelengths far in excess of standard epifluorescence (i.e., spectral deconvolution, fluorescence lifetime microscopy, etc.),125–128 however, these modes of imaging are often accompanied by other issues (including slow acquisition rates, large irradiation dose, etc.,) making them not yet amenable to live cell imaging of relatively fast kinetics.

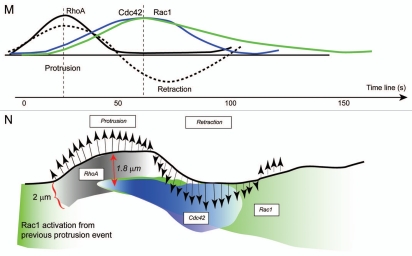

The approach for multiplexed visualization of Rho GTPase biosensors has limitations as discussed above. Recently, Machacek et al. devised a computational approach to virtually multiplex the biosensor readouts to reconstruct the leading edge dynamics of Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA GTPase activities in the mouse fibroblast.37 Using a set of computer algorithms to precisely track the leading edge motion, the authors were able to produce “dynamics maps” of protein activities and leading edge velocities37,129 (Fig. 6). The central premise for their approach is that if protein activities are measured individually against a common fiduciary timer, and if a conserved relationship between such a fiduciary marker and the protein activation dynamics exists, then it would be possible to later reconstruct the full dynamics of all Rho GTPases thus measured independently.37 Using this assumption, the authors have recreated a precise map of the activation dynamics of Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA GTPases during a single cycle of a constitutive leading edge protrusion/retraction. Interestingly, RhoA activity was shown to be directly correlated to the leading edge protrusion/retraction cycles with an almost insignificant time lag, whereas Rac1 and Cdc42 were delayed in activation by approximately 40 seconds. Based on these observations, the authors suggested that the stabilization of the protruded lamellipodia through Rac1/Cdc42-driven mechanisms may require additional time and other factors including formation of adhesions at the leading edge in order to initiate the stabilization of the dendritic actin network.37 The finding that RhoA activation appears to coincide directly with the leading edge motion seems to suggest that RhoA/ROCK/mDia-mediated actin polymerization may be the critical initiator of the leading edge protrusions in fibroblasts. However, Rac1/Cdc42-driven mechanisms appear to be more important in establishment of the persistence of protrusions in order to produce the directionality required during cell edge motion.

Figure 6.

Dynamics mapping and cross-correlational approach to determining the spatio-temporal coordination of GTPases (Taken from Machacek et al.).37 (A, D and G) Edge tracking of the leading edge protrusion/retraction, sampling window numbers 1 ∼ 35 are designated. Scale bar = 10 µm. Dynamics maps of the average velocity and Rac1 (B and C), Cdc42 (E and F) and RhoA (H and I) activities at the leading edge during random protrusion and retraction cycles of MEF/3T3 cells. (J–L) Cross-correlation coefficient distribution between the edge velocity map and the Cdc42 activity map is shown as a function of time shifts. (M) Reconstruction of Rho GTPase dynamics. Timing of Rac1, Cdc42 and RhoA activation relative to edge velocity, as determined with time-lag dependent cross-correlation coefficients; green line, edge movement correlation with Rac1; blue line, edge movement correlation with Cdc42; black line, edge movement correlation with RhoA; dashed lines, edge velocity. (N) Timing and location of GTPase activation during protrusion and retraction (not drawn to scale) determined from the cross correlation maxima and the auto correlation width. Green, Rac1 activation; black, RhoA activation; blue, Cdc42 activation.

Activating the Rho GTPases in Vivo by Optical Manipulations

The detection of either the endogenous Rho GTPase activity or that of a biosensor analogue provides glimpses into the signaling regulation of cells in conditions that most closely mimic the native environment. Recent studies have taken the inverse approach to this, and have produced methods to transiently activate the Rho GTPases in cells through photomanipulations.130,131 In both of these approaches by Wu and Levskaya and their colleagues, components from plant proteins that are responsible for the phototropism (Light-oxygen-voltage: LOV-domain) and photoreceptor signaling network (phytochrome signaling, protein-protein interaction triggered or disrupted by light), respectively, were used in approaches to achieve the photo-regulation of Rho GTPase activities. The direct derivatization of Rho GTPases with the LOV domain was performed by Wu and colleagues in a way such that the combined LOV-Ja domains in the dark-state obstructed the Switch I/II regions of the Rho GTPase.130 The derivatized Rho GTPase additionally contained mutations to eliminate GEF/GAP interactions (E91H and N92H mutations in Rac1) and a constitutive activation mutation (Q61L for Rac1). Upon irradiation at 458∼473 nm light, the Jα helix unraveled thereby exposing the obstructed Switch I/II towards endogenous downstream effector targets and initiated the signaling. The activation has a distinct half-life of approximately 43 seconds for the photoactivatable Rac1, allowing for a multiple activation/inactivation cycling as well as a continuous activation through strobing the irradiation.130 One key point in designing this type of photoactivatable system is the stability of the LOV-Jα complex over the active site of the target molecule in its dark state so that any spurious “leakiness” is controlled. Wu et al. showed that the LOV-Jα in the dark state of the photoactivatable Rac1 was particularly stable because of the formation of a hydrophobic cluster of amino acid residues between Rac1 and the LOV domain in the dark state.130 Therefore, in order to extend this system to other family members of Rho GTPases (as well as to other potentially regulatable targets), introduction of appropriate mutations within the target protein may be necessary to stabilize the dark state, abrogating the leakiness of the system. Levskaya and colleagues took a different approach in which a protein-protein interaction between the optimized version of the Arabidopsis thaliana Phytochrome B (PhyB) and its immediate downstream target Phytochrome interaction factor 6 (PIF6) can be triggered or disrupted by different wavelengths of light.131 By introducing a constitutively membrane anchored PhyB and coexpressing a constitutively activated fragments of Tim, Tiam-1 and Intersectin GEFs (GEF for RhoA, Rac1 and Cdc42, respectively) derivatized with the PIF moiety, authors were able to achieve a reversible plasma membrane recruitment of the constitutively activated GEF fragments upon irradiations at 650/750 nm, for binding and release, respectively.131 The binding and release kinetics were optimized through screening approaches wherein different combinations of PhyB and PIF domains were tested and an optimal pair was found to possess fast binding and release kinetics suitable for in vivo use in living cells. Here, the approach in which the upstream activators of Rho GTPases are photoswitched, poses an interesting alternative to directly activating the Rho proteins through the photoactivatable Rho GTPase analogues. Activation of the endogenous Rho GTPases by providing the photoswitched, activated upstream GEF will naturally limit the signal propagation in the pathway if the rate limiting step is the interaction of active GEF with an available endogenous Rho GTPase at the plasma membrane. However, this will not be the case for the direct photoactivation of the Rho GTPase analogs, as these will result in a transient, local pseudo-overexpression of constitutively activated material. The questions that remain are: Which of these two approaches will likely produce more physiologically realistic signaling dynamics and how does one quantitatively characterize the activation kinetics and the extent of protein activation using these new tools in light of obtaining realistic cellular phenotypic readouts?

Summary

Here, we provide an overview of Rho GTPases and their role in the regulation of the actin polymerization machinery that drives cell motility and describe recent approaches to study Rho GTPases dynamics utilizing state-of-the-art methods. Additional details of fluorescent biosensor design and usage including the computer algorithms required for biosensor data analysis are described in references 132–134.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by GM093121 (D.S., L.H.) and “Sinsheimer Foundation Young Investigator Award” (L.H.). Authors thank Dr. Robert Eddy for the critical reading of the manuscript.

Abbreviations

- ADF

actin depolymerizing factor

- APC

adenomatous polyposis coli

- tYFP

Citrine yellow fluorescent protein

- EB1

end-binding protein 1

- ECFP

enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- FH

formin homology

- FRET

fluorescence resonance energy transfer

- GAP

GTPase activating protein

- GBD

GTPase binding domain

- GDI

guanine nucleotide dissociation inhibitor

- GDP

guanine diphosphate

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GTP

guanine triphosphate

- IRSp53

insulin receptor tyrosine kinase substrate p53

- LIMK

LIM-motif containing protein kinases

- LOV

light-oxygen-voltage

- mDia

mammalian Diaphanous formin

- MT

microtubule

- N-WASp

neuronal-Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- PAK

p21-activated kinase

- PBD

p21-binding domain

- PIF6

phytochrome interaction factor 6

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PhyB

phytochrome B

- RBD

Rho binding domain

- ROCK

rho-associated coiled coil kinase

- VCA

verprolin, cofilin, acidic

- WASp

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein

- WAVE

Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein-family verprolin homologous protein

References

- 1.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: conserved structure and molecular mechanism. Nature. 1991;349:117–127. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hall A. Ras-related GTPases and the cytoskeleton. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:475–479. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.5.475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nobes CD, Hall A. Regulation and function of the Rho subfamily of small GTPases. Cur Opin Genet Dev. 1994;4:77–81. doi: 10.1016/0959-437x(94)90094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, Rac and Cdc42 GTPases: regulators of actin structures, cell adhesion and motility. Biochem Soc Transactions. 1995;23:456–459. doi: 10.1042/bst0230456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nobes CD, Hall A. Rho, rac and cdc42 GTPases regulate the assembly of multimolecular focal complexes associated with actin stress fibers, lamellipodia and filopodia. Cell. 1995;81:53–62. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90370-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridley AJ, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rho regulates the assembly of focal adhesions and actin stress fibers in response to growth factors. Cell. 1992;70:389–399. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90163-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ridley AJ, Paterson HF, Johnston CL, Diekmann D, Hall A. The small GTP-binding protein rac regulates growth factor-induced membrane ruffling. Cell. 1992;70:401–410. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norman JC, Price LS, Ridley AJ, Hall A, Koffer A. Actin filament organization in activated mast cells in regulated by heterotrimeric and small GTP-binding proteins. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:1005–1015. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ridley AJ, Hall A. Signal transduction pathways regulating Rho-mediated stress fiber formation: requirement for a tyrosine kinase. EMBO J. 1994;13:2600–2610. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06550.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chrzanowska-Wodnicka M, Burridge K. Rho-stimulated contractility drives the formation of stress fibers and focal adhesions. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1403–1415. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machesky LM, Hall A. Role of actin polymerization and adhesion to extracellular matrix in Rac- and Rho-induced cytoskeletal reorganization. J Cell Biol. 1997;138:913–926. doi: 10.1083/jcb.138.4.913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Subauste MC, Von Herrath M, Benard V, Chamberlain CE, Chuang TH, Chu K, et al. Rho family proteins modulate rapid apoptosis induced by cytotoxic T lymphocytes and Fas. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:9725–9733. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.13.9725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature. 1990;348:125. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gibbs JB, Marshall MS, Scohick EM, Dixon RAF, Vogel US. Modulation of guanine nucleotide bound to Rac in NIH3T3 cells by oncogenes, growth factors and the GTPase activating protein (GAP) J Biol Chem. 1990;265:20437–20442. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rossman KL, Der CJ, Sondek J. GEF means go: turning on RHO GTPases with guanine nucleotide-exchange factors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:167–180. doi: 10.1038/nrm1587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Snyder JT, Worthylake DK, Rossman KL, Betts L, Pruitt WM, Siderovski DP, et al. Structural basis for the selective activation of Rho GTPases by Dbl exchange factors. Nat Struct Biol. 2002;9:468–475. doi: 10.1038/nsb796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujisawa K, Fujita A, Ishizaki T, Saito Y, Narumiya S. Identification of the Rho-binding domain of p160ROCK, a Rho-associated coiled-coil containing protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23022–23028. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reid T, Furuyashiki T, Ishizaki T, Watanabe G, Watanabe N, Fujisawa K, et al. Rhotekin, a new putative target for Rho bearing homology to a serine/threonine kinase, PKN and rhophilin in the rho-binding domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:13556–13560. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.23.13556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujisawa K, Madaule P, Ishizaki T, Watanabe G, Bito H, Saito Y, et al. Different regions of Rho determine Rho-selective binding of different classes of Rho target molecules. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18943–18949. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rossman KL, Worthylake DK, Snyder JT, Siderovski DP, Campbell SL, Sondek J. A crystallographic view of interactions between Dbs and Cdc42: PH domain-assisted guanine nucleotide exchange. EMBO J. 2002;21:1315–1326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.6.1315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fidyk NJ, Cerione RA. Understanding the catalytic mechanism of GTPase-activating proteins: demonstration of the importance of switch domain stabilization in the stimulation of GTP hydrolysis. Biochemistry. 2002;41:15644–15653. doi: 10.1021/bi026413p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moon SY, Zheng Y. Rho GTPase-activating proteins in cell regulation. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:13–22. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(02)00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang B, Zheng Y. Regulation of RhoA GTP hydrolysis by the GTPase-activating proteins p190, p50RhoGAP, Bcr and 3BP-1. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5249–5257. doi: 10.1021/bi9718447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hart MJ, Maru Y, Leonard D, Witte ON, Evans T, Cerione RA. A GDP dissociation inhibitor that serves as a GTPase inhibitor for the Ras-like protein CDC42Hs. Science. 1992;258:812–815. doi: 10.1126/science.1439791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chuang TH, Bohl BP, Bokoch GM. Biologically active lipids are regulators of Rac:GDI complexation. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:26206–26211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chuang TH, Xu X, Knaus UG, Hart MJ, Bokoch GM. GDP dissociation inhibitor (GDI) prevents intrinsic and GTPase activating protein (GAP)-stimulated GTP hydrolysis by the Rac1 and Rac2 GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:775–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bokoch GM, Bohl BP, Chuang TH. Guanine nucleotide exchange regulates membrane translocation of Rac/Rho GTP-binding proteins. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:31674–31679. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DerMardirossian C, Bokoch GM. GDIs: central regulatory molecules in Rho GTPase activation. Trends Cell Biol. 2005;15:356–363. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.DerMardirossian C, Rocklin G, Seo JY, Bokoch GM. Phosphorylation of RhoGDI by Src regulates Rho GTPase binding and cytosol-membrane cycling. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:4760–4768. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-06-0533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qiao J, Holian O, Lee BS, Huang F, Zhang J, Lum H. Phosphorylation of GTP dissociation inhibitor by PKA negatively regulates RhoA. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:1161–1168. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00139.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dovas A, Choi Y, Yoneda A, Multhaupt HA, Kwon SH, Kang D, et al. Serine 34 phosphorylation of rho guanine dissociation inhibitor (RhoGDIalpha) links signaling from conventional protein kinase C to RhoGTPase in cell adhesion. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:23296–23308. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.098129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sasaki T, Kato M, Takai Y. Consequences of weak interaction of rho GDI with the GTP-bound forms of rho p21 and rac p21. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:23959–23963. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berdeaux RL, Diaz B, Kim L, Martin GS. Active Rho is localized to podosomes induced by oncogenic Src and is required for their assembly and function. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:317–323. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200312168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buccione R, Orth JD, McNiven MA. Foot and mouth: podosomes, invadopodia and circular dorsal ruffles. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:647–657. doi: 10.1038/nrm1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yamaguchi H, Lorenz M, Kempiak S, Sarmiento C, Coniglio S, Symons M, et al. Molecular mechanisms of invadopodium formation: the role of the N-WASP-Arp2/3 complex pathway and cofilin. J Cell Biol. 2005;168:441–452. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200407076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sander EE, ten Klooster JP, van Delft S, van der Kammen RA, Collard JG. Rac downregulates Rho activity: reciprocal balance between both GTPases determines cellular morphology and migratory behavior. J Cell Biol. 1999;147:1009–1022. doi: 10.1083/jcb.147.5.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Machacek M, Hodgson L, Welch C, Elliott H, Pertz O, Nalbant P, et al. Coordination of Rho GTPase activities during cell protrusion. Nature. 2009;461:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hoppe AD, Swanson JA. Cdc42, Rac1 and Rac2 display distinct patterns of activation during phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:3509–3519. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-11-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kozma R, Sarner S, Ahmed S, Lim L. Rho family GTPases and neuronal growth cone remodelling: relationship between increased complexity induced by Cdc42Hs, Rac1 and acetylcholine and collapse induced by RhoA and lysophosphatidic acid. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:1201–1211. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.3.1201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leeuwen FN, Kain HE, Kammen RA, Michiels F, Kranenburg OW, Collard JG. The guanine nucleotide exchange factor Tiam1 affects neuronal morphology; opposing roles for the small GTPases Rac and Rho. J Cell Biol. 1997;139:797–807. doi: 10.1083/jcb.139.3.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang F, Herzmark P, Weiner OD, Srinivasan S, Servant G, Bourne HR. Lipid products of PI(3)Ks maintain persistent cell polarity and directed motility in neutrophils. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:513–518. doi: 10.1038/ncb810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Keymeulen A, Wong K, Knight ZA, Govaerts C, Hahn KM, Shokat KM, et al. To stabilize neutrophil polarity, PIP3 and Cdc42 augment RhoA activity at the back as well as signals at the front. J Cell Biol. 2006;174:437–445. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200604113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wong K, Pertz O, Hahn K, Bourne H. Neutrophil polarization: spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity support a self-organizing mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:3639–3644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600092103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rottner K, Hall A, Small JV. Interplay between Rac and Rho in the control of substrate contact dynamics. Curr Biol. 1999;9:640–648. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80286-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yamana N, Arakawa Y, Nishino T, Kurokawa K, Tanji M, Itoh RE, et al. The Rho-mDia1 pathway regulates cell polarity and focal adhesion turnover in migrating cells through mobilizing Apc and c-Src. Mol Cell Biol. 2006;26:6844–6858. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00283-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kraynov VS, Chamberlain C, Bokoch GM, Schwartz MA, Slabaugh S, Hahn KM. Localized Rac activation dynamics visualized in living cells. Science. 2000;290:333–337. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5490.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nalbant P, Hodgson L, Kraynov V, Toutchkine A, Hahn KM. Activation of endogenous Cdc42 visualized in living cells. Science. 2004;305:1615–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.1100367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Pertz O, Hodgson L, Klemke RL, Hahn KM. Spatiotemporal dynamics of RhoA activity in migrating cells. Nature. 2006;440:1069–1072. doi: 10.1038/nature04665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen F, Hodgson L, Rabinovich A, Pertz O, Hahn K, Price JH. Functional proteometrics for cell migration. Cytometry. 2006 doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Healy KD, Hodgson L, Kim TY, Shutes A, Maddileti S, Juliano RL, et al. DLC-1 suppresses non-small cell lung cancer growth and invasion by RhoGAP-dependent and independent mechanisms. Mol Carcinog. 2007;47:326–337. doi: 10.1002/mc.20389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Narumiya S, Tanji M, Ishizaki T. Rho signaling, ROCK and mDia1, in transformation, metastasis and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Boku S, Watanabe N, Fujita A, Iwamatsu A, et al. Signaling from Rho to the actin cytoskeleton through protein kinases ROCK and LIM-kinase. Science. 1999;285:895–898. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5429.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Riento K, Ridley AJ. Rocks: multifunctional kinases in cell behaviour. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:446–456. doi: 10.1038/nrm1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ohashi K, Nagata K, Maekawa M, Ishizaki T, Narumiya S, Mizuno K. Rho-associated kinase ROCK activates LIM-kinase 1 by phosphorylation at threonine 508 within the activation loop. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3577–3582. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lin T, Zeng L, Liu Y, DeFea K, Schwartz MA, Chien S, et al. Rho-ROCK-LIMK-cofilin pathway regulates shear stress activation of sterol regulatory element binding proteins. Circ Res. 2003;92:1296–1304. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000078780.65824.8B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Song X, Chen X, Yamaguchi H, Mouneimne G, Condeelis JS, Eddy RJ. Initiation of cofilin activity in response to EGF is uncoupled from cofilin phosphorylation and dephosphorylation in carcinoma cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2871–2881. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bernstein BW, Painter WB, Chen H, Minamide LS, Abe H, Bamburg JR. Intracellular pH modulation of ADF/cofilin proteins. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2000;47:319–336. doi: 10.1002/1097-0169(200012)47:4<319::AID-CM6>3.0.CO;2-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bowman GD, Nodelman IM, Hong Y, Chua NH, Lindberg U, Schutt CE. A comparative structural analysis of the ADF/cofilin family. Proteins. 2000;41:374–384. doi: 10.1002/1097-0134(20001115)41:3<374::aid-prot90>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.DesMarais V, Ichetovkin I, Condeelis J, Hitchcock-DeGregori SE. Spatial regulation of actin dynamics: a tropomyosin-free, actin-rich compartment at the leading edge. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:4649–4660. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zigmond SH. Beginning and ending an actin filament: control at the barbed end. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2004;63:145–188. doi: 10.1016/S0070-2153(04)63005-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andrianantoandro E, Pollard TD. Mechanism of actin filament turnover by severing and nucleation at different concentrations of ADF/cofilin. Mol Cell. 2006;24:13–23. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Bamburg JR, Bernstein BW. ADF/cofilin. Curr Biol. 2008;18:273–275. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Bernstein BW, Bamburg JR. ADF/cofilin: a functional node in cell biology. Trends Cell Biol. 2010;20:187–195. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.DesMarais V, Ghosh M, Eddy R, Condeelis J. Cofilin takes the lead. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:19–26. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.van Rheenen J, Condeelis J, Glogauer M. A common cofilin activity cycle in invasive tumor cells and inflammatory cells. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:305–311. doi: 10.1242/jcs.031146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Oser M, Condeelis J. The cofilin activity cycle in lamellipodia and invadopodia. J Cell Biochem. 2009;108:1252–1262. doi: 10.1002/jcb.22372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Condeelis J. How is actin polymerization nucleated in vivo? Trends Cell Biol. 2001;11:288–293. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(01)02008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Edwards DC, Sanders LC, Bokoch GM, Gill GN. Activation of LIM-kinase by Pak1 couples Rac/Cdc42 GTPase signalling to actin cytoskeletal dynamics [see comments] Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:253–259. doi: 10.1038/12963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kligys K, Claiborne JN, DeBiase PJ, Hopkinson SB, Wu Y, Mizuno K, et al. The slingshot family of phosphatases mediates Rac1 regulation of cofilin phosphorylation, laminin-332 organization and motility behavior of keratinocytes. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32520–32528. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707041200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang TY, DerMardirossian C, Bokoch GM. Cofilin phosphatases and regulation of actin dynamics. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2006;18:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Goode BL, Eck MJ. Mechanism and function of formins in the control of actin assembly. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:593–627. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shemesh T, Kozlov MM. Actin polymerization upon processive capping by formin: a model for slowing and acceleration. Biophys J. 2007;92:1512–1521. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.098459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romero S, Le Clainche C, Didry D, Egile C, Pantaloni D, Carlier MF. Formin is a processive motor that requires profilin to accelerate actin assembly and associated ATP hydrolysis. Cell. 2004;119:419–429. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Zigmond SH. Formin-induced nucleation of actin filaments. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2004;16:99–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2003.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zigmond SH, Evangelista M, Boone C, Yang C, Dar AC, Sicheri F, et al. Formin leaky cap allows elongation in the presence of tight capping proteins. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1820–1823. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.09.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Lammers M, Meyer S, Kuhlmann D, Wittinghofer A. Specificity of interactions between mDia isoforms and Rho proteins. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:35236–35246. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805634200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bartolini F, Moseley JB, Schmoranzer J, Cassimeris L, Goode BL, Gundersen GG. The formin mDia2 stabilizes microtubules independently of its actin nucleation activity. J Cell Biol. 2008;181:523–536. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200709029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Palazzo AF, Cook TA, Alberts AS, Gundersen GG. mDia mediates Rho-regulated formation and orientation of stable microtubules. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:723–729. doi: 10.1038/35087035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wen Y, Eng CH, Schmoranzer J, Cabrera-Poch N, Morris EJ, Chen M, et al. EB1 and APC bind to mDia to stabilize microtubules downstream of Rho and promote cell migration. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:820–830. doi: 10.1038/ncb1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Symons M, Derry JM, Karlak B, Jiang S, Lemahieu V, McCormick F, et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein, a novel effector for the GTPase CDC42Hs, is implicated in actin polymerization. Cell. 1996;84:723–734. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81050-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kempiak SJ, Yamaguchi H, Sarmiento C, Sidani M, Ghosh M, Eddy RJ, et al. A neural Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome protein-mediated pathway for localized activation of actin polymerization that is regulated by cortactin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:5836–5842. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M410713200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Derivery E, Gautreau A. Generation of branched actin networks: assembly and regulation of the N-WASP and WAVE molecular machines. BioEssays. 2010;32:119–131. doi: 10.1002/bies.200900123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Takenawa T, Miki H. WASP and WAVE family proteins: key molecules for rapid rearrangement of cortical actin filaments and cell movement. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1801–1809. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.10.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nakagawa H, Miki H, Ito M, Ohashi K, Takenawa T, Miyamoto S. N-WASP, WAVE and Mena play different roles in the organization of actin cytoskeleton in lamellipodia. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1555–1565. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.8.1555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Miki H, Suetsugu S, Takenawa T. WAVE, a novel WASP-family protein involved in actin reorganization induced by Rac. EMBO J. 1998;17:6932–6941. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.23.6932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Takenawa T. From N-WASP to WAVE: key molecules for regulation of cortical actin organization. Novartis Found Symp. 2005;269:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Nakanishi O, Suetsugu S, Yamazaki D, Takenawa T. Effect of WAVE2 phosphorylation on activation of the Arp2/3 complex. J Biochem. 2007;141:319–325. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvm034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ishiguro K, Cao Z, Ilasca ML, Ando T, Xavier R. Wave2 activates serum response element via its VCA region and functions downstream of Rac. Exp Cell Res. 2004;301:331–337. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2004.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Miki H, Takenawa T. Regulation of actin dynamics by WASP family proteins. J Biochem. 2003;134:309–313. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvg146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.She HY, Rockow S, Tang J, Nishimura R, Skolnik EY, Chen M, et al. Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein is associated with the adapter protein Grb2 and the epidermal growth factor receptor in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 1997;8:1709–1721. doi: 10.1091/mbc.8.9.1709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Carlier MF, Nioche P, Broutin-L'Hermite I, Boujemaa R, Le Clainche C, Egile C, et al. GRB2 links signaling to actin assembly by enhancing interaction of neural Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (N-WASp) with actin-related protein (ARP2/3) complex. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:21946–21952. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000687200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Benesch S, Lommel S, Steffen A, Stradal TE, Scaplehorn N, Way M, et al. Phosphatidylinositol 4,5-biphosphate (PIP2)-induced vesicle movement depends on N-WASP and involves Nck WIP and Grb2. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:37771–37776. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204145200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Miki H, Yamaguchi H, Suetsugu S, Takenawa T. IRSp53 is an essential intermediate between Rac and WAVE in the regulation of membrane ruffling. Nature. 2000;408:732–735. doi: 10.1038/35047107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Ismail AM, Padrick SB, Chen B, Umetani J, Rosen MK. The WAVE regulatory complex is inhibited. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:561–563. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Derivery E, Lombard B, Loew D, Gautreau A. The Wave complex is intrinsically inactive. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2009;66:777–790. doi: 10.1002/cm.20342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lundquist EA. Small GTPases. WormBook. 2006:1–18. doi: 10.1895/wormbook.1.67.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Johnson DI. Cdc42: An essential Rho-type GTPase controlling eukaryotic cell polarity. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1999;63:54–105. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.63.1.54-105.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Bielek H, Anselmo A, Dermardirossian C. Morphological and proliferative abnormalities in renal mesangial cells lacking RhoGDI. Cell Signal. 2009;21:1974–1983. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Del Pozo MA, Kiosses WB, Alderson NB, Meller N, Hahn KM, Schwartz MA. Integrins regulate GTP-Rac localized effector interactions through dissociation of Rho-GDI. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:232–239. doi: 10.1038/ncb759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Michaelson D, Silletti J, Murphy G, D'Eustachio P, Rush M, Philips MR. Differential localization of Rho GTPases in live cells: regulation by hypervariable regions and RhoGDI binding. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:111–126. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.1.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Ren XD, Schwartz MA. Determination of GTP loading on Rho. Methods Enzymol. 2000;325:264–272. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)25448-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Benard V, Bokoch GM. Assay of Cdc42, Rac and Rho GTPase activation by affinity methods. Methods Enzymol. 2002;345:349–359. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(02)45028-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Cho SY, Klemke RL. Purification of pseudopodia from polarized cells reveals redistribution and activation of Rac through assembly of a CAS/Crk scaffold. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:725–736. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200111032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Taylor DL, Wang YL. Fluorescently labeled molecules as probes of the structure and function of living cells. Nature. 1980;284:405–410. doi: 10.1038/284405a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tsien RY, Miyawaki A. Seeing the machinery of live cells. Science. 1998;280:1954–1955. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Miyawaki A, Griesbeck O, Heim R, Tsien RY. Dynamic and quantitative Ca2+ measurements using improved cameleons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:2135–2140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zaccolo M, De Giorgi F, Cho CY, Feng L, Knapp T, Negulescu PA, et al. A genetically encoded, fluorescent indicator for cyclic AMP in living cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:25–29. doi: 10.1038/71345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green fluorescent protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Heim R, Tsien RY. Engineering green fluorescent protein for improved brightness, longer wavelengths and fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Curr Biol. 1996;6:178–182. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00450-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Adams SR, Harootunian AT, Buechler YJ, Taylor SS, Tsien RY. Fluorescence ratio imaging of cyclic AMP in single cells. Nature. 1991;349:694–697. doi: 10.1038/349694a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Hahn K, DeBiasio R, Taylor DL. Patterns of elevated free calcium and calmodulin activation in living cells. Nature. 1992;359:736–738. doi: 10.1038/359736a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Miyawaki A, Llopis J, Heim R, McCaffery JM, Adams JA, Ikura M, et al. Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin [see comments] Nature. 1997;388:882–887. doi: 10.1038/42264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Llopis J, Westin S, Ricote M, Wang Z, Cho CY, Kurokawa R, et al. Ligand-dependent interactions of coactivators steroid receptor coactivator-1 and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor binding protein with nuclear hormone receptors can be imaged in live cells and are required for transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4363–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.8.4363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ting AY, Kain KH, Klemke RL, Tsien RY. Genetically encoded fluorescent reporters of protein tyrosine kinase activities in living cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:15003–15008. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211564598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Haj FG, Verveer PJ, Squire A, Neel BG, Bastiaens PI. Imaging sites of receptor dephosphorylation by PTP1B on the surface of the endoplasmic reticulum. Science. 2002;295:1708–1711. doi: 10.1126/science.1067566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Heikal AA, Hess ST, Baird GS, Tsien RY, Webb WW. Molecular spectroscopy and dynamics of intrinsically fluorescent proteins: coral red (dsRed) and yellow (Citrine) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:11996–12001. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.22.11996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Miyawaki A, Tsien RY. Monitoring protein conformations and interactions by fluorescence resonance energy transfer between mutants of green fluorescent protein. Methods Enzymol. 2000;327:472–500. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(00)27297-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nguyen AW, Daugherty PS. Evolutionary optimization of fluorescent proteins for intracellular FRET. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23:355–360. doi: 10.1038/nbt1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Griesbeck O, Baird GS, Campbell RE, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. Mechanism and applications. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:29188–29194. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102815200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lakowicz JR. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 1999. pp. 368–377. [Google Scholar]

- 121.dos Remedios CG, Moens PD. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer spectroscopy is a reliable “ruler” for measuring structural changes in proteins. Dispelling the problem of the unknown orientation factor. J Struct Biol. 1995;115:175–185. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.1995.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nagai T, Yamada S, Tominaga T, Ichikawa M, Miyawaki A. Expanded dynamic range of fluorescent indicators for Ca(2+) by circularly permuted yellow fluorescent proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:10554–10559. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400417101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Machacek M, Hodgson L, Welch C, Elliot H, Nalbant P, Pertz O, et al. Coordination of Rho GTPase activation during protrusion. Nature. 2009;461:99–103. doi: 10.1038/nature08242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Ouyang M, Huang H, Shaner NC, Remacle AG, Shiryaev SA, Strongin AY, et al. Simultaneous visualization of protumorigenic Src and MT1-MMP activities with fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Cancer Res. 2010;70:2204–2212. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ameloot M, Beechem JM, Brand L. Simultaneous analysis of multiple fluorescence decay curves by Laplace Transforms: Deconvolution with reference or excitation profiles. Biophys Chem. 1986;23:155–171. doi: 10.1016/0301-4622(86)85001-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Verveer PJ, Squire A, Bastiaens PI. Improved spatial discrimination of protein reaction states in cells by global analysis and deconvolution of fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy data. J Microsc. 2001;202:451–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2818.2001.00917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Le Puil M, Biggerstaff JP, Weidow BL, Price JR, Naser SA, White DC, et al. A novel fluorescence imaging technique combining deconvolution microscopy and spectral analysis for quantitative detection of opportunistic pathogens. J Microbiol Methods. 2006;67:597–602. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2006.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Pepperkok R, Squire A, Geley S, Bastiaens PI. Simultaneous detection of multiple green fluorescent proteins in live cells by fluorescence lifetime imaging microscopy. Curr Biol. 1999;9:269–272. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80117-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Machacek M, Danuser G. Morphodynamic profiling of protrusion phenotypes. Biophys J. 2006;90:1439–1452. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.070383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Wu YI, Frey D, Lungu OI, Jaehrig A, Schlichting I, Kuhlman B, et al. A genetically encoded photoactivatable Rac controls the motility of living cells. Nature. 2009;461:104–108. doi: 10.1038/nature08241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Levskaya A, Weiner OD, Lim WA, Voigt CA. Spatiotemporal control of cell signalling using a light-switchable protein interaction. Nature. 2009;461:997–1001. doi: 10.1038/nature08446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Hodgson L, Nalbant P, Shen F, Hahn K. Imaging and photobleach correction of Mero-CBD, sensor of endogenous Cdc42 activation. Methods Enzymol. 2006;406:140–156. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)06012-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hodgson L, Pertz O, Hahn KM. Design and optimization of genetically encoded fluorescent biosensors: GTPase biosensors. Methods Cell Biol. 2008;85:63–81. doi: 10.1016/S0091-679X(08)85004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Hodgson L, Shen F, Hahn K. Biosensors for characterizing the dynamics of rho family GTPases in living cells. Curr Protoc Cell Biol. 2010;14:1–26. doi: 10.1002/0471143030.cb1411s46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Itoh RE, Kurokawa K, Ohba Y, Yoshizaki H, Mochizuki N, Matsuda M. Activation of rac and cdc42 video imaged by fluorescent resonance energy transfer-based single-molecule probes in the membrane of living cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6582–6591. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6582-6591.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]