Delay in the diagnosis of medullary thyroid cancer until after thyroidectomy is relatively common and leads to suboptimal treatment.

Abstract

Context:

Medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) is diagnosed only after thyroidectomy in approximately 10–15% of cases. This delay in diagnosis can have adverse consequences such as missing underlying pheochromocytoma or hyperparathyroidism in unrecognized multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and choosing a suboptimal extent of surgery. Barriers to accurate preoperative diagnosis and management strategies after the discovery of occult MTC are reviewed.

Evidence Acquisition:

We reviewed PubMed (1975-September 2010) using the search terms medullary carcinoma, calcitonin, multinodular goiter, Graves' disease, calcium/diagnostic use, and pentagastrin/diagnostic use.

Evidence Synthesis:

The combined prevalence of occult MTC in thyroidectomy series is approximately 0.3%. Routine calcitonin measurement in goiter patients identifies C-cell hyperplasia as well as MTC. Challenges include interpreting intermediate values and unavailability of pentagastrin stimulation testing in the United States. Early studies have begun to identify appropriate cutoff values for calcium-stimulated calcitonin. For management of incidentally discovered MTC, we highlight the role of early measurement of calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen, RET testing, and comprehensive neck ultrasound exam to direct further imaging, completion thyroidectomy, and lymph node dissection.

Conclusions:

Occult MTC is an uncommon, but clinically significant entity. If calcium stimulation testing cutoff data become well-validated, calcitonin screening would likely become more widely accepted in the diagnostic work-up for thyroid nodules in the United States. Among patients with incidental MTC, those with persistently elevated serum calcitonin levels, positive RET test, or nodal disease are good candidates for completion thyroidectomy and lymph node dissection in selected cases, whereas patients with undetectable calcitonin, negative RET testing, and no sonographic abnormalities often may be watched conservatively.

Medullary thyroid cancer (MTC) is an uncommon thyroid tumor accounting for approximately 3% of thyroid cancer diagnoses. In the majority of cases, the preoperative diagnosis is secure, based on the results of thyroid fine-needle aspiration (FNA), serum calcitonin level, and RET protooncogene testing. In approximately 10–15% of cases, diagnosis of MTC is made only after thyroidectomy. This delay can have several adverse consequences. A rare but critical consequence is the risk of missing pheochromocytoma in the setting of occult multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN 2). Undiagnosed hyperparathyroidism also is potentially consequential. A more common problem is the underutilization of imaging and a suboptimal extent of surgery when the diagnosis of MTC is not made preoperatively. The main focus of this review is to examine factors associated with incidental discovery of MTC, including barriers to more accurate preoperative diagnosis. A second focus is to review management choices once an incidental MTC diagnosis has been made. The scope of this review includes two scenarios: 1) thyroidectomy performed for another indication that was confirmed at surgical pathology with previously unsuspected MTC also present; and 2) thyroidectomy performed for an indication that was not confirmed at surgical pathology; instead unsuspected MTC was present.

Preoperatively Diagnosed MTC: Management Overview

MTC, in distinction from differentiated thyroid cancer (DTC), originates from calcitonin-producing parafollicular C cells of the thyroid, believed to be derived from embryological neural crest. Once MTC is suspected clinically, the initial biochemical, genetic, and preoperative imaging work-ups are also distinctive. Surgical decision-making in known MTC patients takes into account all of these factors. For example, preoperative identification of a germline RET mutation (seen in the 25% of MTC patients with MEN 2) triggers a clinical evaluation for pheochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism and raises the potential for bilobar involvement in the thyroid as well as early nodal metastasis, depending on the specific RET mutation site (1). Failure to appreciate a clinically occult pheochromocytoma can result in a hypertensive crisis during surgery or after exposure to certain drugs, with significant mortality (2, 3). Appropriate α-blockade and pheochromocytoma resection should certainly precede surgical management of MTC to avoid intraoperative complications (4).

In the 2009 American Thyroid Association (ATA) guidelines for the surgical management of known MTC, the extent of calcitonin preoperative elevation guides the selection of preoperative imaging studies, which in turn influence the extent of surgery (4). A majority of guideline authors agreed to a consensus view that sporadic MTC in adults should be treated, at a minimum, with total thyroidectomy and central node dissection (4–6). In the consensus ATA view, ipsilateral level II–V dissection is best justified by suspicious lymph nodes on examination, ultrasound, or other imaging or intraoperative findings (4). A prophylactic approach to ipsilateral neck dissection is favored by some authors because the incidence of lateral node metastases in macroscopic MTC is roughly 80% (6). A recent study by Machens and Dralle (7) correlated basal and stimulated calcitonin levels with primary tumor size and lymph node involvement in a large cohort of 291 patients. Subjects who proved to have no lymph node involvement had a mean calcitonin value of 559 pg/ml [95% confidence interval (CI), 309–809] and a mean primary tumor size of 9.6 mm (95% CI, 8.1–11.2). Thus, the overwhelming majority of patients with a calcitonin level greater than 809 or a tumor diameter greater than 11.2 mm had nodal involvement. These authors advocate a central and bilateral modified neck dissection when preoperative basal calcitonin levels are greater than 200 pg/ml (7). Although leading centers disagree on the appropriate risk:benefit ratio of prophylactic neck dissections, a strong consensus exists to actively detect and, in most cases, to resect involved nodes (see Ref. 8 for discussion).

Clinical Setting of Incidentally Discovered MTC

Incidentally discovered MTC can occur after thyroidectomy performed for a variety of other indications. Although routine application of FNA has reduced the use of thyroidectomy for nonmalignant disease in the United States compared with 30 yr ago, thyroidectomy is still common for nodular goiter and less common for Graves' disease and toxic adenoma. This setting will be discussed later in this section. A second setting contributing to occult MTC is cytologically indeterminate nodules, including suspected follicular neoplasms and atypical cells of uncertain significance. Approximately 1–2% of such cases prove to be MTC at thyroidectomy (9). A third setting is patients with clear-cut cancer on FNA, in whom the diagnosis of MTC is not suspected or confirmed on cytopathology. Occasionally, these tumors are classified as poorly differentiated, anaplastic, or undifferentiated on FNA. A fourth setting for incidentally discovered MTC is patients undergoing surgery for known DTC. In the U.S. Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) database (1973–2002), 2.8% of MTC patients had concurrent PTC or FTC on surgical pathology, although many of the DTCs were incidentally discovered microcarcinomas in the setting of known MTC (10). A higher prevalence of mixed MTC and PTC in thyroidectomy specimens was seen in a retrospective study of 196 consecutive cases of MTC; of these, 27 (13.8%) were found to have coincidental microscopic PTC. No association was found between the presence of microscopic PTC and overall outcome of MTC (11). A smaller study by Kim et al. (12) found a 19% prevalence of coincidental PTC in their MTC series.

The prevalence of MTC in nodular goiter can be estimated from several prospective and retrospective series, some of which incorporate routine calcitonin testing in evaluation of these patients. For series with more than 100 patients, MTC prevalence ranges from 0.1 to 1.3%. The composite prevalence of MTC is 0.31% across 15,992 patients in 12 series (Table 1). Although a case-enrichment bias is possible in the patients selected for surgery by criteria including calcitonin testing in some series, the reasonably consistent results across several studies point to a low-level but readily detectable prevalence of MTC in patients presenting with multinodular thyroid disease.

Table 1.

Incidence of occult MTC in postsurgical multinodular goiter specimens

| First author (Ref.) | Year | Total no. of thyroid specimens | No. of occult MTC (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Atli (44) | 2006 | 815 | 3 (0.4) |

| Bertazzo (45) | 1981 | 917 | 1 (0.1) |

| Cerci (46) | 2007 | 294 | 1 (0.3) |

| Costante (47)a | 2007 | 5,817 | 15 (0.26) |

| Fernando (48) | 2009 | 32 | 1 (3.1) |

| Gandolfi (49) | 2004 | 81 | 0 (0.0) |

| Hahm (31)a | 2001 | 1,448 | 10 (0.6) |

| Niccoli (25)a | 1997 | 1,167 | 16 (1.3) |

| Pelizzo (50) | 1996 | 539 | 2 (0.3) |

| Pezzolla (51) | 2010 | 1,507 | 0 (0.0) |

| Rieu (29)a | 1995 | 469 | 1 (0.2) |

| Tezelman (52) | 2009 | 1,695b | 0 (0.0) |

| Tezelman (52) | 2009 | 1,211c | 1 (0.08) |

| Surgical total | 15,992 | 51 (0.31) |

Studies with routine calcitonin screening.

Bilateral subtotal thyroidectomy.

Total or near-total thyroidectomy.

The coincidence of Graves' disease with thyroid carcinoma is relatively uncommon. The majority of carcinomas that have been associated with Graves' disease are either papillary or follicular. Occult MTC in Graves' disease is extremely rare; one large study reported a single case in 3112 thyroidectomies for Graves' disease (13).

Recently, a systematic review of 24 autopsy series by Valle and Kloos (14) reported a prevalence of 0.14% of occult MTC in unselected autopsies. As the authors note, this prevalence may be an underestimate because of the variability between the series in terms of slice thickness, calcitonin immunostaining, and extent of the pathological exam of the thyroid (14). Whereas autopsy series report a very low prevalence of undiagnosed MTC, patients undergoing thyroidectomy for nodular thyroid disease have a rate that appears to be somewhat higher, as summarized in Table 1. Potentially, some conditions leading to follicular epithelial nodules may also predispose patients to C-cell proliferation. Nonhereditary CCH (C-cell hyperplasia) is more common than occult MTC in surgical series of nodular goiter and may be associated with a variety of thyroid and nonthyroidal conditions. Substantial overlap between CCH and MTC in subjects with modest calcitonin elevations complicates the routine application of calcitonin testing in nodular goiter patients.

Improving the Rate of Preoperative Diagnosis of MTC: Role of History, Ultrasound, FNA, and Calcitonin Testing

To reduce the rate of MTC cases diagnosed postoperatively, a diagnostic strategy is needed to use historical clues, plus findings from ultrasound, FNA, and the appropriate use of calcitonin testing. In a small fraction of MTC cases, familial inheritance is occult but discoverable. Thus, in 5–6% of cases, a germline RET mutation is present even when the family history is initially judged negative (15). Subsequent genetic testing typically reveals the presence of less penetrant RET mutations, such as those with ATA risk levels A and B (4). Very careful attention to family history is sometimes useful in detecting these situations, including an appreciation of when the family history has low information content due to small family size, early death, or lack of contact with biological parents and sibs. In addition to family history, the presence of systemic symptoms pointing to MTC can be informative—especially diarrhea, flushing, and bone pain. In data from Kebebew et al. (16), 10% of MTC patients had such systemic symptoms at presentation, usually in the setting of widespread metastatic disease.

Two recent studies compared preoperative thyroid ultrasonographic findings of MTC and PTC. Kim et al. (17) found no difference between the two groups in size, echogenicity, or calcifications, but found that nodules with histologically confirmed MTC tended to be more ovoid than did PTC nodules, which followed a “more tall than wide” pattern on ultrasound. Lee et al. (18) found that nodules with MTC tended to be slightly larger than those with PTC and more often had cystic changes. The presence of microcalcifications and echogenicity was comparable in the two diseases (18). Coarse calcifications may be more prevalent in MTC. Real-time ultrasound elastography has shown promise as an emerging technique in differentiating benign from malignant nodules based on a computed elastic modulus value (19). This technique can be adapted to allow real-time analysis of individual nodules within a multinodular goiter, although experience in diagnosing MTC is currently very limited (20).

There is controversy regarding the sensitivity of FNA for MTC; the diagnostic accuracy of the technique may vary widely in clinical practice. A German study reported that the accuracy of diagnosing MTC by FNA was 89% by experienced cytopathologists; furthermore, in 98.9% of patients, the cytopathology findings indicated a need for thyroidectomy (21). Combined data for the three largest cytopathology series with surgical ascertainment indicate that 79% of the patients had FNA positive for MTC, and 96% indicated some form of thyroid neoplasm prompting surgery (Table 2). A shortcoming of these studies is that patients lacking surgical ascertainment were lost to analysis, making a true sensitivity very difficult to estimate. Additional studies that examined the accuracy of FNA in detecting any thyroid malignancy have estimated that the sensitivity of FNA ranges from 66–97% and specificity ranges from 75–93% (22–24). In contrast, several European studies focusing on patients with nodular goiter and employing routine calcitonin testing and extensive surgical ascertainment indicate a sensitivity of FNA for MTC of only 30–50% (25, 26). Variation in sensitivity has been attributed to inconsistent use of calcitonin immunohistochemistry, difficulty in recognizing typical and variant MTC cytomorphology, and especially problems stemming from multiplicity of nodules and the challenges of selecting appropriate nodules for FNA (25, 26).

Table 2.

Reported accuracy of FNA in detecting MTC

| Author | Total MTC cases on surgical pathology | Cases with correct MTC diagnosis preoperatively (incidence %) | Cases with nonbenign cytopathology leading to surgery (incidence %) | Cases with benign cytopathology preoperatively (incidence %) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chang (53) | 34 | 28 (82) | 6 (17) | 0 (0) |

| Papaparaskeva (21) | 91 | 81 (89) | 9 (10) | 1 (1) |

| Bugalho (54) | 67 | 42 (63) | 19 (28) | 6 (9) |

| Overall | 192 | 151 (79) | 34 (17) | 7 (3) |

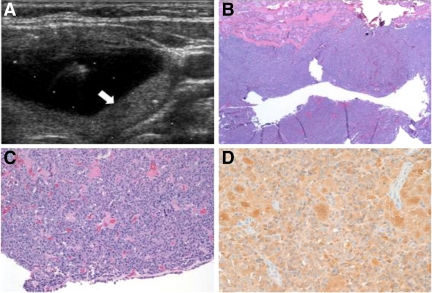

Given the limitations of history and ultrasound clues to MTC and the potential shortcomings of FNA, preoperative diagnosis can be difficult. An example of a case of missed preoperative diagnosis of MTC is illustrated in Fig. 1. In this instance, the complex cystic character of the MTC tumor was associated with a nondiagnostic FNA, and surgery was performed after the patient complained of dysphagia.

Fig. 1.

A, Transverse view of left thyroid lobe obtained at time of ultrasound-guided FNA of a 4.9 × 2.3 × 3.4-cm complex cystic nodule of a 36-yr-old female. The central cystic portion of the complex nodule is seen, along with a posterior solid portion (arrow). FNA cytopathology demonstrated scant cellularity with few groups of follicular cells and blood, but overall, the specimen was inadequate. The patient underwent left hemithyroidectomy for compressive dysphagia; surgical pathology revealed a 2.9-cm, partially cystic MTC on a background of nodular hyperplasia. B, Surgical section low-power view, showing cystic medullary thyroid cancer with a fragment of hyperplastic normal thyroid (top) (hematoxylin and eosin). C, Higher power view. D, Calcitonin immunohistochemistry revealing dense homogeneous reactivity. The postoperative calcitonin was undetectable, and CEA was 2.6. RET-protooncogene testing was negative for exons 10, 11, and 13–16. Completion thyroidectomy was deferred, and serum calcitonin, CEA, and neck ultrasound have remained normal through 3-yr follow-up.

Calcitonin Testing: Controversies and Potential Resolution

Routine measurement of serum calcitonin to screen for MTC in patients with a known thyroid nodule or multinodular goiter is not standard practice in the United States and has been an area of controversy. The 2009 revised ATA guidelines for thyroid nodules and DTC, although recognizing a positive cost-effectiveness analysis for calcitonin testing in this setting (27), “cannot recommend either for or against the routine measurement of serum calcitonin” (28). Cooper et al. (28) noted that prevalence of microscopic MTC or CCH of uncertain clinical significance clouds the interpretation of calcitonin as a screening test. Several European and Asian studies have illustrated how routine calcitonin measurement can complement FNA in detecting MTC in nodular goiter patients. In these studies, elevated basal and pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin levels at appropriate cutoff values have a positive predictive value of greater than 50% in diagnosing MTC preoperatively (29). A study by Elisei et al. (26) concluded that outcomes were improved in patients who were screened prospectively with calcitonin measurements to detect occult MTC before undergoing thyroidectomy for another indication, compared with a historical MTC control group, largely composed of incidentally discovered cases. The European Thyroid Association recommends routine measurement of serum calcitonin in the evaluation of patients undergoing thyroidectomy for multinodular goiter (30).

The controversy regarding calcitonin testing in nodular goiter patients stems in part from the unavailability of pentagastrin in the United States, difficulty in assigning appropriate calcitonin cut-points, and unclear cost-effectiveness. The prospective screening programs cited above used pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin levels to increase the specificity of the preoperative diagnosis, and most of their recommendations are based on the combination of elevated basal and stimulated calcitonin levels. There is variability among the recommended basal calcitonin cut-points to elect stimulation testing and to choose surgery after stimulation testing. However, most centers agree that a basal calcitonin value of greater than 100 pg/ml is highly suggestive of MTC (25, 29, 31–33). Although many of the screening studies used calcitonin two-site radioimmunometric assays, a two-site automated chemiluminescent assay system is now more widely employed both in the United States and in some European countries, making it somewhat difficult to extrapolate from older values.

A perennial challenge is to determine whether a given elevated calcitonin value signifies CCH or MTC. Although CCH is known to be a preneoplastic condition in patients with MEN 2, its significance remains unclear outside of this genetic setting. In prospective screening studies, approximately 50% of the cases with calcitonin levels between 20 and 100 pg/ml were found to have CCH postoperatively and not MTC (25, 29, 31, 32). The problem of specificity for MTC is clearly illustrated by data from Hahm et al. (31). In this study, 3.9% of nodular goiter patients had basal calcitonin levels above the 99th percentile for normal subjects. Thus, calcitonin elevation appeared to be 4-fold more prevalent in goiter patients than in normal subjects. Of the 56 patients with basal calcitonin elevation out of a total of 1448 with nodular goiter, 10 MTC cases were identified at surgery (six tumors greater than 1 cm), with 46 patients having no evidence of the disease. Significantly, all proven MTC cases had a pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin level greater than 100, whereas only two of 22 non-MTC cases had such a value (31).

Gender-specific cutoff values have recently been proposed to improve the accuracy of basal and pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin levels to predict occult MTC (34). Machens et al. (34) compared 26 goiter patients who proved to have occult MTC with 74 who proved to have sporadic CCH. For women, a basal value of 20 pg/ml or greater had a positive predictive value for MTC of 88%. A comparable predictive value for men required a basal calcitonin of 80 pg/ml or greater (34). Pentagastrin-stimulated values greater than 250 pg/ml in women and 500 pg/ml in men were highly predictive of MTC rather than CCH (34). Nonhereditary CCH has been associated with PTC and lymphocytic thyroiditis. Serum calcitonin can also be elevated in a variety of systemic conditions including chronic renal insufficiency, patients taking proton pump inhibitors with hypergastrinemia, critical illness, and smoking, and in patients with neuroendocrine tumors of the lung, pancreas, and prostate (4, 35).

Calcium-stimulated calcitonin is a potentially attractive alternative to calcitonin testing. Doyle et al. (36) compared basal, calcium-stimulated, and pentagastrin-stimulated calcitonin values in normal subjects. The 95th percentile basal value was 5 pg/ml in normal males and 5.7 pg/ml in females. The 95th percentile peak value 2 min after calcium stimulation was 95.4 pg/ml in men and 90.2 pg/ml in women, compared with 37.8 and 26.2 pg/ml, respectively, for pentagastrin (36). Preliminary data for calcium-stimulated calcitonin in the settings of nodular goiter and MTC have been reported by Colombo et al. (37). Multinodular goiter patients without MTC had peak calcium-stimulated calcitonin levels up to 2-fold greater than normals (calcium-stimulated calcitonin range, 98–184 pg/ml, vs. pentagastrin-stimulated range, 21–86 pg/ml) (37). Very few patients with small MTC in the setting of nodular goiter were included in this preliminary report, and patients with low-level persistent MTC exhibited some overlap with benign multinodular goiter patients (37). The encouraging early results of Doyle et al. (36) and of Colombo et al. (37) show that calcium is a well-tolerated, potent calcitonin secretagogue and that normal ranges are needed for nodular goiter patients compared with normal subjects, and in comparison with patients with early MTC. Calcium-stimulated calcitonin appears to be promising as a means to further evaluate nodular goiter patients with moderate basal calcitonin elevations.

A study by Cheung et al. (27) evaluated the cost-effectiveness of routine calcitonin measurements in patients undergoing evaluation for a thyroid nodule. The study compared target populations with a thyroid nodule and undergoing screening based on standard ATA guidelines or ATA guidelines plus a basal calcitonin measurement. A cutoff basal value for surgical intervention was set at 50 pg/ml, with no provision for stimulation testing. Assuming a seemingly optimistic specificity of calcitonin testing for MTC of 98% at this cutoff value, the analysis indicated that routine measurement of serum calcitonin would cost $11,793 per life years saved, translating to an additional 113,000 life years for a 5.3% increase in cost. Cost-effectiveness increased with younger age and larger nodules. However, at such a low cutoff basal value, cases of CCH and microscopic MTC will be captured at higher frequency than clinically significant MTC; thus, the cost per life years saved may be underestimated in this analysis.

Adjunctive approaches to FNA

Other modalities also have some potential to improve the preoperative diagnosis of MTC. To increase the sensitivity of FNA in the diagnosis of MTC, two studies have examined the use of RT-PCR to amplify calcitonin cDNA from samples obtained via aspiration of a nodule or lymph node. In these small-scale series, calcitonin by RT-PCR was claimed to be 100% sensitive and specific for confirmation of the diagnosis of MTC (38, 39). Clearly, both this technique and calcitonin concentration in aspirate fluid are still susceptible to sampling and nodule multiplicity issues. As novel systemic approaches to detection, circulating tumor cells can be detected in known MTC patients, and very low abundance circulating tumor-derived mutant DNA has been assayed in several cancer types using advanced technology such as BEAMing (single-molecule PCR on microparticles in water-oil emulsion) (40), although such techniques appear unlikely to supplant calcitonin testing.

Diagnostic Strategy for Occult MTC

Consistent with the above literature review, our practice is to recommend basal calcitonin testing for thyroid nodule patients with increased risk of MTC, including those with a family history of MTC, with a diagnosis of hyperparathyroidism or pheochromocytoma, or symptoms of flushing or diarrhea. We also consider calcitonin testing in patients with FNA results suspicious for malignancy that lack typical features of papillary or follicular neoplasms, and in patients with a metastatic pattern typical of MTC. On the other hand, patients with benign FNA results from a solitary nodule are rarely offered calcitonin testing. If the basal calcitonin level is greater than 80 pg/ml in males or at a lower threshold in females, we generally offer total thyroidectomy, including central neck dissection in patients with marked calcitonin elevation. Ipsilateral neck dissection is considered, based on preoperative neck ultrasound and other imaging. Patients with basal calcitonin levels between 20 and 80 pg/ml may undergo calcium stimulation following the Doyle protocol, although cutoffs for patients with nodular goiter are currently under investigation. If well-validated, such data could provide a basis to recommend routine calcitonin testing in U.S. nodular goiter patients. Our current approach if the basal calcitonin is elevated but below 20 pg/ml and there is no hereditary disease is to follow patients conservatively with ultrasound and basal calcitonin, considering surgery for progressive calcitonin rise or suspicious ultrasound or FNA findings during follow-up.

Evaluation after Diagnosis of Occult MTC

Once the diagnosis of occult MTC is made postoperatively, ATA guidelines recommend the measurement of the serum markers calcitonin and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). RET protooncogene testing is also recommended in all of these patients, as well as a neck ultrasound (4). The timing of the calcitonin and CEA test is relevant. In our practice, we obtain these markers as soon as the diagnosis of occult MTC is suspected to have some gauge of the degree of preoperative calcitonin elevation. Calcitonin levels decline progressively and variably after surgery, with some patients not reaching a nadir for up to 8 to 12 wk or longer. We also obtain nadir values at that point, useful in determining a calcitonin doubling time after approximately four measurements. If the calcitonin value exceeds 400 pg/ml, patients are considered for additional imaging, including neck computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resource imaging (MRI), chest CT, liver protocol abdominal MRI, and bone imaging, following ATA consensus guidelines (4). As noted above, a positive RET test result would provide critical risk information regarding concurrent pheochromocytoma and hyperparathyroidism, bilobar involvement in the thyroid, and disease risk in first-degree relatives. In MTC patients with a negative family history for the disease, the estimated risk of familial involvement is approximately 5–6% (15).

Treatment of Occult MTC

Including both sporadic and familial cases, approximately 13% of MTCs are bilobar in U.S. SEER data. In a multivariate analysis, patients with MTC who underwent lobectomy had poorer survival than patients who underwent total or subtotal thyroidectomy, regardless of the extent of nodal dissection (10). However, it seems unlikely that calcitonin- and RET-negative patients with a sonographically normal contralateral lobe would be significantly disadvantaged by a watchful waiting approach, as opposed to completion thyroidectomy. Our approach to the treatment of occult MTC follows current ATA guidelines. Patients initially treated with hemithyroidectomy who have unifocal intrathyroidal sporadic MTC with no CCH, negative surgical margins, and no suspicion for persistent disease on neck ultrasound may be considered for additional surgery or for follow-up if the basal serum calcitonin is undetectable. Patients with a persistent elevated calcitonin should undergo additional testing and therapy. Often this includes further imaging, completion thyroidectomy, and central node dissection, plus ipsilateral nodal dissection if warranted by ultrasound or FNA. Patients with positive RET tests also are offered completion thyroidectomy and consideration for neck dissection, based on a higher prevalence of bilobar disease in MEN 2.

Outcome

Currently, only limited outcomes data assess the impact of a failed preoperative diagnosis of MTC. Whereas delay of therapy for greater than 12 months is a known negative prognostic factor for DTC (41), comparable data aren't available for MTC. Elisei et al. (26) compared the clinical course of 44 MTC patients identified through a calcitonin screening program to 45 historical MTC cases, 96% of whom were only diagnosed after surgery. The two patient populations were treated in different eras, 1991–1998 and 1970–1990, respectively. Patients identified in the screening program were significantly more likely to have early-stage disease at diagnosis and had correspondingly better overall survival (26). Clearly, however, the historical control population in this study does not mimic contemporary MTC practice with respect to modern diagnostic and surgical approaches, even while sharing the property of infrequent screening calcitonin testing with U.S. patients. Many, but not all, incidentally discovered MTCs are small and confined to the thyroid gland. For stage I MTC, overall survival is excellent, with a very high likelihood of calcitonin normalization. In U.S. SEER data, such patients had 10 yr survival greater than 95% (10). The presence of lymphadenopathy reduces the chance of calcitonin normalization substantially, and 10-yr survival is reduced to approximately 75% (42). Increasing tumor size greatly increases the risk of lymph node metastases (43). For example, MTC tumors between 1 and 1.5 cm (irrespective of surrounding goiter) have on average 7.5 affected nodes (95% CI, 3.6–11.3) (7). On balance, the consequences of a missed preoperative diagnosis of MEN 2 are occasionally life-threatening, but a broader impact comes from the subset of patients who have delayed diagnosis of sporadic MTC leading to delayed and inadequate surgery.

Conclusion

Occult MTC is a rare entity, seen in approximately 0.3% of patients with nodular goiter. Calcitonin testing is appropriate for patients with increased risk of MTC based upon history or atypical cytopathology. Significant basal calcitonin elevations (>80 pg/ml in males or >20 pg/ml in females) should prompt further evaluation or surgery. Should valid cut-points for calcium-stimulated calcitonin become available, routine calcitonin testing could become a recommended adjunct to thyroid nodule evaluation in the United States. When an incidental MTC is discovered, the decision to pursue completion thyroidectomy and neck dissection should depend on persistent calcitonin elevation, positive RET testing, or evidence of nodal disease on imaging. In select cases lacking these findings, a conservative approach may be reasonable.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health SPORE (Specialized Programs of Research Excellence) in Head and Neck Cancer Grant CA-96784.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have no relationships to disclose.

Footnotes

- CCH

- C-cell hyperplasia

- CEA

- carcinoembryonic antigen

- CI

- confidence interval

- DTC

- differentiated thyroid cancer

- FNA

- fine-needle aspiration

- MEN 2

- multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2

- MTC

- medullary thyroid carcinoma.

References

- 1. Machens A, Niccoli-Sire P, Hoegel J, Frank-Raue K, van Vroonhoven TJ, Roeher HD, Wahl RA, Lamesch P, Raue F, Conte-Devolx B, Dralle H. 2003. Early malignant progression of hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med 349:1517–1525 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. O'Riordan JA. 1997. Pheochromocytomas and anesthesia. Int Anesthesiol Clin 35:99–127 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Eisenhofer G, Rivers G, Rosas AL, Quezado Z, Manger WM, Pacak K. 2007. Adverse drug reactions in patients with phaeochromocytoma: incidence, prevention and management. Drug Saf 30:1031–1062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kloos RT, Eng C, Evans DB, Francis GL, Gagel RF, Gharib H, Moley JF, Pacini F, Ringel MD, Schlumberger M, Wells SA., Jr 2009. Medullary thyroid cancer: management guidelines of the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid 19:565–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Lundgren CI, Delbridg L, Learoyd D, Robinson B. 2007. Surgical approach to medullary thyroid cancer. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metabol 51:818–824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cohen MS, Moley JF. 2003. Surgical treatment of medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Intern Med 253:616–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Machens A, Dralle H. 2010. Biomarker-based risk stratification for previously untreated medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:2655–2663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ball DW. 2009. American Thyroid Association guidelines for management of medullary thyroid cancer: an adult endocrinology perspective. Thyroid 19:547–550 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jo VY, Stelow EB, Dustin SM, Hanley KZ. 2010. Malignancy risk for fine-needle aspiration of thyroid lesions according to the Bethesda System for Reporting Thyroid Cytopathology. Am J Clin Pathol 134:450–456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Roman S, Lin R, Sosa JA. 2006. Prognosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: demographic, clinical, and pathologic predictors of survival in 1252 cases. Cancer 107:2134–2142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Biscolla RP, Ugolini C, Sculli M, Bottici V, Castagna MG, Romei C, Cosci B, Molinaro E, Faviana P, Basolo F, Miccoli P, Pacini F, Pinchera A, Elisei R. 2004. Medullary and papillary tumors are frequently associated in the same thyroid gland without evidence of reciprocal influence in their biologic behavior. Thyroid 14:946–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kim WG, Gong G, Kim EY, Kim TY, Hong SJ, Bae Kim W, Shong YK. 2010. Concurrent occurrence of medullary thyroid carcinoma and papillary thyroid carcinoma in the same thyroid should be considered as coincidental. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 72:256–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chao TC, Lin JD, Chen MF. 2004. Surgical treatment of thyroid cancers with concurrent Graves disease. Ann Surg Oncol 11:407–412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Valle LA, Kloos RT. 2011. The prevalence of occult medullary thyroid carcinoma at autopsy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 96:E109–E113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wohllk N, Cote GJ, Bugalho MM, Ordonez N, Evans DB, Goepfert H, Khorana S, Schultz P, Richards CS, Gagel RF. 1996. Relevance of RET proto-oncogene mutations in sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3740–3745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kebebew E, Ituarte PH, Siperstein AE, Duh QY, Clark OH. 2000. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: clinical characteristics, treatment, prognostic factors, and a comparison of staging systems. Cancer 88:1139–1148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kim SH, Kim BS, Jung SL, Lee JW, Yang PS, Kang BJ, Lim HW, Kim JY, Whang IY, Kwon HS, Jung CK. 2009. Ultrasonographic findings of medullary thyroid carcinoma: a comparison with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Korean J Radiol 10:101–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lee S, Shin JH, Han BK, Ko EY. 2010. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: comparison with papillary thyroid carcinoma and application of current sonographic criteria. AJR Am J Roentgenol 194:1090–1094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hong Y, Liu X, Li Z, Zhang X, Chen M, Luo Z. 2009. Real-time ultrasound elastography in the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. J Ultrasound Med 28:861–867 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sebag F, Vaillant-Lombard J, Berbis J, Griset V, Henry JF, Petit P, Oliver C. 2010. Shear wave elastography: a new ultrasound imaging mode for the differential diagnosis of benign and malignant thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95:5281–5288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Papaparaskeva K, Nagel H, Droese M. 2000. Cytologic diagnosis of medullary carcinoma of the thyroid gland. Diagn Cytopathol 22:351–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tee YY, Lowe AJ, Brand CA, Judson RT. 2007. Fine-needle aspiration may miss a third of all malignancy in palpable thyroid nodules: a comprehensive literature review. Ann Surg 246:714–720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ravetto C, Colombo L, Dottorini ME. 2000. Usefulness of fine-needle aspiration in the diagnosis of thyroid carcinoma: a retrospective study in 37,895 patients. Cancer 90:357–363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Caraway NP, Sneige N, Samaan NA. 1993. Diagnostic pitfalls in thyroid fine-needle aspiration: a review of 394 cases. Diagn Cytopathol 9:345–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Niccoli P, Wion-Barbot N, Caron P, Henry JF, de Micco C, Saint Andre JP, Bigorgne JC, Modigliani E, Conte-Devolx B. 1997. Interest of routine measurement of serum calcitonin: study in a large series of thyroidectomized patients. The French Medullary Study Group. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82:338–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Elisei R, Bottici V, Luchetti F, Di Coscio G, Romei C, Grasso L, Miccoli P, Iacconi P, Basolo F, Pinchera A, Pacini F. 2004. Impact of routine measurement of serum calcitonin on the diagnosis and outcome of medullary thyroid cancer: experience in 10,864 patients with nodular thyroid disorders. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 89:163–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cheung K, Roman SA, Wang TS, Walker HD, Sosa JA. 2008. Calcitonin measurement in the evaluation of thyroid nodules in the United States: a cost-effectiveness and decision analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93:2173–2180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cooper DS, Doherty GM, Haugen BR, Hauger BR, Kloos RT, Lee SL, Mandel SJ, Mazzaferri EL, McIver B, Pacini F, Schlumberger M, Sherman SI, Steward DL, Tuttle RM. 2009. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid 19:1167–1214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Rieu M, Lame MC, Richard A, Lissak B, Sambort B, Vuong-Ngoc P, Berrod JL, Fombeur JP. 1995. Prevalence of sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma: the importance of routine measurement of serum calcitonin in the diagnostic evaluation of thyroid nodules. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 42:453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gharib H, Papini E, Paschke R, Duick DS, Valcavi R, Hegedüs L, Vitti P. 2010. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists, Associazione Medici Endocrinologi, and European Thyroid Association medical guidelines for clinical practice for the diagnosis and management of thyroid nodules: Executive Summary of Recommendations. J Endocrinol Invest 33:287–291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hahm JR, Lee MS, Min YK, Lee MK, Kim KW, Nam SJ, Yang JH, Chung JH. 2001. Routine measurement of serum calcitonin is useful for early detection of medullary thyroid carcinoma in patients with nodular thyroid diseases. Thyroid 11:73–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pacini F, Fontanelli M, Fugazzola L, Elisei R, Romei C, Di Coscio G, Miccoli P, Pinchera A. 1994. Routine measurement of serum calcitonin in nodular thyroid diseases allows the preoperative diagnosis of unsuspected sporadic medullary thyroid carcinoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 78:826–829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Ozgen AG, Hamulu F, Bayraktar F, Yilmaz C, Tüzün M, Yetkin E, Tunçyürek M, Kabalak T. 1999. Evaluation of routine basal serum calcitonin measurement for early diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma in seven hundred seventy-three patients with nodular goiter. Thyroid 9:579–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Machens A, Hoffmann F, Sekulla C, Dralle H. 2009. Importance of gender-specific calcitonin thresholds in screening for occult sporadic medullary thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 16:1291–1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Toledo SP, Lourenço DM, Jr, Santos MA, Tavares MR, Toledo RA, Correia-Deur JE. 2009. Hypercalcitoninemia is not pathognomonic of medullary thyroid carcinoma. Clinics (Sao Paulo) 64:699–706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Doyle P, Düren C, Nerlich K, Verburg FA, Grelle I, Jahn H, Fassnacht M, Mäder U, Reiners C, Luster M. 2009. Potency and tolerance of calcitonin stimulation with high-dose calcium versus pentagastrin in normal adults. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94:2970–2974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Colombo C, Verga U, Perrino M, Vicentini L, Beck-Peccoz P, Fugazzola L. 2010. High-dose calcium and pentagastrin tests in patients with cured or persistent medullary thyroid cancer and in controls: comparison of the efficacy and the tolerance. Proc 14th Annual International Thyroid Congress, Paris, 2010 (Abstract P-0923) [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bugalho MJ, Mendonça E, Sobrinho LG. 2000. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: an accurate pre-operative diagnosis by reverse transcription-PCR. Eur J Endocrinol 143:335–338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Takano T, Miyauchi A, Matsuzuka F, Liu G, Higashiyama T, Yokozawa T, Kuma K, Amino N. 1999. Preoperative diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma by RT-PCR using RNA extracted from leftover cells within a needle used for fine needle aspiration biopsy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:951–955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Diehl F, Schmidt K, Choti MA, Romans K, Goodman S, Li M, Thornton K, Agrawal N, Sokoll L, Szabo SA, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, Diaz LA., Jr 2008. Circulating mutant DNA to assess tumor dynamics. Nat Med 14:985–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Mazzaferri EL, Jhiang SM. 1994. Long-term impact of initial surgical and medical therapy on papillary and follicular thyroid cancer. Am J Med 97:418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Machens A, Schneyer U, Holzhausen HJ, Dralle H. 2005. Prospects of remission in medullary thyroid carcinoma according to basal calcitonin level. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90:2029–2034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Scollo C, Baudin E, Travagli JP, Caillou B, Bellon N, Leboulleux S, Schlumberger M. 2003. Rationale for central and bilateral lymph node dissection in sporadic and hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:2070–2075 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Atli M, Akgul M, Saryal M, Daglar G, Yasti AC, Kama NA. 2006. Thyroid incidentalomas: prediction of malignancy and management. Int Surg 91:237–244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bertazzo S, Turioni G, Ghimenton F, Toniolo L, Borsato N. 1981. [Thyroid nodular pathology: retrospective study of 917 surgical interventions]. Chir Ital 33:852–863 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cerci C, Cerci SS, Eroglu E, Dede M, Kapucuoglu N, Yildiz M, Bulbul M. 2007. Thyroid cancer in toxic and non-toxic multinodular goiter. J Postgrad Med 53:157–160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Costante G, Meringolo D, Durante C, Bianchi D, Nocera M, Tumino S, Crocetti U, Attard M, Maranghi M, Torlontano M, Filetti S. 2007. Predictive value of serum calcitonin levels for preoperative diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma in a cohort of 5817 consecutive patients with thyroid nodules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 92:450–455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Fernando R, Mettananda DS, Kariyakarawana L. 2009. Incidental occult carcinomas in total thyroidectomy for benign diseases of the thyroid. Ceylon Med J 54:4–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gandolfi PP, Frisina A, Raffa M, Renda F, Rocchetti O, Ruggeri C, Tombolini A. 2004. The incidence of thyroid carcinoma in multinodular goiter: retrospective analysis. Acta Biomed 75:114–117 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pelizzo MR, Toniato A, Piotto A, Bernante P. 1996. [Cancer in multinodular goiter]. Ann Ital Chir 67:351–356 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Pezzolla A, Docimo G, Ruggiero R, Monacelli M, Cirocchi R, Parmeggiani D, Conzo G, Gubitosi A, Lattarulo S, Ciampolillo A, Avenia N, Docimo L, Palasciano N. 2010. [Incidental thyroid carcinoma: a multicentric experience]. Recenti Prog Med 101:194–198 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Tezelman S, Borucu I, Senyurek Giles Y, Tunca F, Terzioglu T. 2009. The change in surgical practice from subtotal to near-total or total thyroidectomy in the treatment of patients with benign multinodular goiter. World J Surg 33:400–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Chang TC, Wu SL, Hsiao YL. 2005. Medullary thyroid carcinoma: pitfalls in diagnosis by fine needle aspiration cytology and relationship of cytomorphology to RET proto-oncogene mutations. Acta Cytol 49:477–482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bugalho MJ, Santos JR, Sobrinho L. 2005. Preoperative diagnosis of medullary thyroid carcinoma: fine needle aspiration cytology as compared with serum calcitonin measurement. J Surg Oncol 91:56–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]