Abstract

Over the cancer disease trajectory, from diagnosis and treatment to remission or end of life, patients and their families face difficult decisions. The provision of information and support when most relevant can optimize cancer decision making and coping. An interactive health communication system (IHCS) offers the potential to bridge the communication gaps that occur among patients, family, and clinicians and to empower each to actively engage in cancer care and shared decision making. This is a report of the authors' experience (with a discussion of relevant literature) in developing and testing a Web-based IHCS—the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS)—for patients with advanced lung cancer and their family caregivers. CHESS provides information, communication, and coaching resources as well as a symptom tracking system that reports health status to the clinical team. Development of an IHCS includes a needs assessment of the target audience and applied theory informed by continued stakeholder involvement in early testing. Critical issues of IHCS implementation include 1) need for interventions that accommodate a variety of format preferences and technology comfort ranges; 2) IHCS user training, 3) clinician investment in IHCS promotion, and 4) IHCS integration with existing medical systems. In creating such comprehensive systems, development strategies need to be grounded in population needs with appropriate use of technology that serves the target users, including the patient/family, clinical team, and health care organization. Implementation strategies should address timing, personnel, and environmental factors to facilitate continued use and benefit from IHCS.

An interactive health communication system (IHCS) offers one platform for providing the information, communication, and coaching resources that cancer patients and their families need to understand the disease, find support, and develop decision-making and coping skills. One such IHCS—the Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS)—has evolved over the past 20 years. Based on our recent experience creating and testing a new version of CHESS—“Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support”—this article outlines the issues faced in developing and implementing such a system within the cancer context.

Keywords: oncology, outcomes research, quality of care

THE IMPACT OF CANCER

A cancer diagnosis brings about an abrupt transition into a new world orbiting around cancer.1 A new language is learned; a new identity as a patient is established; complicated treatment decisions are presented; schedules are restructured around treatments and scans; and physical, emotional, and spiritual challenges emerge. With a large care team of multiple physicians (i.e., oncologists, surgeons, and radiologists), nurses, physician assistants, lab technicians, social workers, and other professionals, one may not know where to turn, and the coordination of care may be overwhelming. Patients may also need to navigate the complexities of finding and making sense of second opinions, clinical trials, and insurance coverage. For the healthy person, the health care system can be daunting. For someone facing a life-threatening illness such as cancer, it can feel like a tidal wave washing you out to sea. Although patients may feel alone in their experience, this cancer “tidal wave” also breaks over their social networks, most significantly affecting those closest to them and then rippling out through concentric social circles. Shorter stays within acute treatment settings have required that cancer patients be sent home with greater responsibility to manage their own complicated treatment and care needs, including activities requiring a high degree of technical skill.8 Many patients rely on family and friends to assist with these home health care needs. Caregiving responsibilities include monitoring symptoms, dealing with unpleasant side effects, and providing emotional and instrumental support. Caregivers also play an important role in making decisions3,4 and gathering and sharing information, and caregivers influence the cancer patient's ability to respond to and cope with the stress of living with the disease, its treatment, and progression.5

DECISION MAKING IN CANCER

Throughout the cancer trajectory, including diagnosis, treatment, remission, and end of life, patients and caregivers face numerous dynamic needs and difficult decisions.6,7 The health care system has shifted its focus from an authoritative/paternal model to a collaborative/consumer model, requiring people to become more fully engaged in their own care decisions,8,9 often over a short time span. Shortly after diagnosis, patients may be required to make significant treatment decisions. Later, difficult choices include whether to continue curative treatments or focus on palliative care and, if the latter is chosen, which palliative options are most appropriate. The shift from clinician decision making to supporting patient choice means greater personal responsibility for patients who need to become active and informed in the pursuit of their personal well-being and quality of life.10 Information management can be a key factor in understanding the cancer diagnosis, making treatment decisions, and predicting the prognosis to better plan for future events.11–13 For people facing cancer, access to information can promote self-care, participation, and a sense of control; it can also facilitate the overall process of decision making and lead to improved mood and quality of life.14 However, information alone is not sufficient to direct health behaviors and decisions.10 Health care decisions, particularly in life-threatening illness, should result from a collaborative, fully informed decision-making process resulting from effective communication among the patient, family, and clinical team.15,16 Patients and family members often have vast differences in opinion regarding preferences for treatment decisions and care,17,18 which can create tension in their relationship and impair decision making and care planning.19 Services that facilitate family communication and improve patients' and family members' satisfaction with treatment decisions, particularly in life-threatening situations, are greatly needed. To generate a fully engaged team, people need the right information at the right time as well as support to effectively use that information.10 Useful information needs to be an integral part of health care delivery; patients and caregivers need to confidently share decision making with the clinician, and communication needs to be central to patient care. Accordingly, facilitating the exchange of information and support between the patient, caregiver, and clinician—not just directing interventions to the patient—is critical to generating positive health outcomes.20–23

ROLE OF AN IHCS

Interactive health communication systems hold the potential to help patients navigate the cancer crisis. As patients assume an increasingly active role in their own health care, health care organizations will rely on computer technologies to extend traditional health services—such as health promotion, disease management, and decision support and education—directly to patients and caregivers.24,25 As one such technology, IHCS provides a conduit for information and communication exchange. Given the interdependence of the patients' and family caregivers' experiences, 26 systems that provide information, support, and skills training for this dyad (not just the patient) may best facilitate coping with the physical and psychosocial sequelae of illness, collaborative decision making, and communication with the health care team.20–23 In turn, such a system could foster positive outcomes including quality of life, disease course, psychological adjustment, and survival.27–31

The IHCS delivers potentially beneficial services via 3 primary channels.32 First, IHCSs provide ready and organized access to information. Second, IHCSs link people together as a channel for communication and support. Third, IHCSs act as an interactive coach, wherein the system gathers information from the user, applies algorithms or decision rules, and provides relevant feedback or prompts.

Information

Health information can empower people to make decisions about their health and to talk with their clinicians.14 IHCSs can offer a wealth of potential information resources. Patients and caregivers have been documented to use the Internet to find second opinions, seek experiential information from other patients, interpret symptoms, and seek information about tests and treatments.33 Patients also use the Internet to check their doctors' advice covertly and to develop expertise in their cancer. By becoming more informed about the disease and treatments, patients and caregivers may have increased confidence, ask providers fewer, more informed questions, manage their disease more effectively, and even monitor and intervene to improve the quality of their own care, all facilitating a partnership with the clinical team.14 Yet despite these potential positive aspects of accessing health information, to some the information is overwhelming, increases awareness of conflicting cancer information, and can raise doubt about the right course of cancer treatment.14

Communication

IHCSs provide both a conduit for remote communication and a means to educate patients and caregivers on communication tactics to use in clinical encounters. Many people use the Internet to connect with others facing similar circumstances,33 to share information, personal experiences and opinions, encouragement, and support.14 Web sites also provide a mechanism to enhance communication with one's existing social network (e.g., www.caringbridge.org). An IHCS could similarly adapt this technology or serve as a portal to existing services, helping users elicit emotional and instrumental support. An IHCS could also provide a direct communication link to the clinical team, allowing patients and caregivers to provide updates and post questions regarding a patient's status. Furthermore, these systems can instruct users in which questions to ask clinicians in a variety of clinical situations; this, in turn, could facilitate the patient/caregiver/clinician communication exchange. By promoting awareness, monitoring, and communication exchange, an IHCS can provide patients and caregivers a greater sense of control over the cancer experience and enhance their engagement as partners in their health care and decision making.

Coaching

The field of health informatics has experienced rapid growth in the development and study of health decision aids, coaching tools designed to facilitate patient involvement in informed health decisions.34 Treatment decision aids are designed to provide individuals with information about their condition and the probable outcomes of different treatment courses, to improve understanding of which outcomes are of the greatest personal importance, and then to facilitate decision making consistent with personal values and preferences.35 Accordingly, most decision aids focus attention on the decisionmaking process, the target outcome of which is to teach users how to select a decision option.

However, numerous challenges may present themselves when implementing a decision, at times making this part of the decision process just as difficult, or even more so, than the decision making. Decisions with foreseeable consequences may require physical, mental, and practical preparation. Communicating one's decision may also be difficult, particularly if one's decision conflicts with family or other preferences. Furthermore, acting on a decision generates additional feedback for evaluating the decision's quality. By only addressing the initial decision-making process, decision aids miss the opportunity to facilitate patient behaviors consistent with their decision preference.

Advantages of Electronic Delivery Mechanisms

IHCSs can disseminate information resources, social support, and skills training more widely and at lower cost than in-person or one-on-one delivery modalities. Whereas one-on-one interventions can be time-consuming, expensive, and difficult for the patient or caregiver to attend,36,37 Internet-based interventions can break these barriers, offering timely, tailored information on demand at the convenience, location, speed, depth, and level of privacy the user prefers. Such systems can also connect people to remote others for support and information that otherwise would not be available. Furthermore,IHCSs can facilitate a team care approach drawing together multiple disciplines in one forum, with continuity across the disease trajectory. Although these applications can operate through a variety of mechanisms (e.g., telephones, PDAs, personal computers, public kiosks), this article highlights an Internet-based computer system. The World Wide Web has had one of the fastest adoption rates of any innovation in history,8 and Eysenbach14 has challenged the field to develop and critically evaluate IHCSs that can maximize the positive effect of the Internet and to leverage such technology for patients who want it, without disadvantaging those with different preferences.

DEVELOPMENT AND DESIGN OF AN IHCS

Theoretical Foundation

Kinsella and colleagues38 and others have called for a theory-based approach to designing and evaluating IHCSs. Self-determination theory (SDT) provides additional understanding of how an IHCS benefits patients and caregivers. SDT asserts that fulfillment of the fundamental psychological needs of competence (self-efficacy), autonomy (sense of choice or volition), and relatedness (sense of connection/belonging)39 is essential to promote optimal functioning, health, and personal well-being.39,40. Social contexts supportive of the needs for competence, autonomy, and relatedness have been associated with positive mood, maintained health behavior change, and better mental health.39

IHCS interventions that leverage similar characteristics may likewise facilitate cancer coping. As patients/caregivers develop 1) competence in information gathering, decision making, and coping behaviors, 2) the autonomy that comes with regaining a sense of control over their lives, and 3) social support systems (relatedness) for sharing their cancer experience, they will adopt or maintain coping behaviors that are in their best interests and their quality of life will improve.41 In turn, improvements in quality of life can improve patient outcomes.

Needs Assessment

Beyond a theoretical foundation, building a successful IHCS requires meeting the consumer's needs. To understand how to best provide care and services to patients and caregivers, we must understand the entire universe of their care delivery, information, and support needs. Needs assessment allows researchers to directly assess the perceived needs of a specific group of people (patients, caregivers, etc.), so that the allocation of resources can be prioritized to improve quality of service. Individual interviews, focus groups, and surveys are examples of methods for assessing needs, wherein a representative sample of consumers are asked questions that they are uniquely qualified to answer, focusing on examination of their personal experience, rather than postulating solutions. The critical incident technique (CIT) is one example of an interview strategy.42 Rather than ask directly what the individual needs, CIT asks consumers to think about specific events in their life relevant to the issue in question (e.g., cancer). For each event, they describe critical incidents that come to mind (fears, frustrations, uncertainties, barriers, bad surprises, difficulties).

These specific encounters illuminate specific needs, themes, and categories. By delving into the consumer's mind, the researchers identify situations, barriers, and problems that people face in confronting and coping with a given situation, and then researchers draw from their technical expertise to develop creative solutions for what is not currently available. Selecting target groups for needs assessments requires several critical considerations. Foremost is deciding who is the appropriate target audience for the assessment. For example, in developing a system that would be helpful across the cancer continuum from diagnosis into caregiver bereavement, it is beneficial to include current patients and caregivers as well as cancer survivors and bereaved caregivers who could offer immediate and prospective as well as retrospective reports illustrating their needs. Similarly, the timing of survey administration in relation to the disease course needs to be carefully considered: for example, newly diagnosed versus post-treatment patients. Furthermore, the needs assessment sample should represent the target audience on important characteristics including age, sex, education, disease stage and diagnostic status, and level of experience with using the proposed technology. An additional key consideration is the extent to which recruiting for needs assessment is affected by the phenomenon that those with the greatest needs may be less likely to make time for an interview or complete a questionnaire because of limited resources and the assessment burden.

IHCS Prototype and Evaluation

Once IHCS services are selected and initially designed to address the target users' needs, paper prototyping43,44 is an efficient means of system usability testing to ensure effective navigation of the IHCS interface. For this process, paper mock-ups of online functionality, content, and layout are created without visual aesthetics such as graphics or design features. Prototyping involves guiding potential users through the page mock-ups depicting how the actual Web site would be viewed, with a series of predetermined activities addressing the developers' questions. Interactions with the page sheets as well as any verbal reactions are noted. In addition to prepared interview questions, the interviewer follows up on any unexpected interactions for further insight. Alterations suggested through one user's experience are easily made and then presented to the next paper prototype subject as an alternative solution. The testing of multiple renditions of specific features without delays of programming time facilitates rapid cycling of modifications. However, paper prototyping is limited in the interactive functionalities that can be meaningfully translated. Furthermore, the small number of prototype users typically involved (5–10 people for a specific function) raises concern regarding the sample's representation of the larger target audience and the appropriateness of design decisions based on such a small sample. To ameliorate these concerns, a sample selection that represents the target audience's diversity is needed, and a more diverse target audience may require larger prototype samples.

IMPLEMENTATION OF AN IHCS

Developing a tool that will be useful to those facing a health crisis is only the first step. An essential next step is identifying the prospective users and connecting them with the IHCS. Implementation of any intervention within a health care organization is always fraught with challenges. However, a unique challenge with implementing an IHCS stems from the fact that patients, rather than the organization (e.g., hospital, insurer) or its members (e.g., clinicians), are the intended users and key adopters.24 This is even more complicated when the IHCS aims to target not the organization's primary consumer, the patient, but rather a remote benefactor, the caregiver. However, to best address the patient–caregiver–clinician team, reaching this complex target audience within the health care organization is essential.

Successful implementation also requires incorporating the IHCS into the clinical care system. Clinicians are often the mediator between the health care organization offering an IHCS and the patients and caregivers targeted by a system. Therefore, organizations adopting an IHCS must attend to the needs of the clinical staff to ensure successful implementation. Clinicians operate under very busy schedules with difficult demands on their time. An IHCS that makes their work easier or more efficient or expands the services they can offer would have greater potential for acceptance.25 Alternatively, if clinicians believe that the benefit to their patients is significant, they may also have stronger motivation for system adoption.

CASE EXAMPLE: CHESS

First developed in 1989, CHESS is a noncommercial IHCS created by a multidisciplinary team of clinical, communication, and decision scientists at the University of Wisconsin. CHESS disease-focused modules aim to provide an integrated, user-driven system that combines information, communication, and interactive coaching tools to patients and caregivers facing a health crisis (e.g., cancer, heart disease, pediatric asthma). CHESS has been one of the most extensively studied IHCSs, having been (over its evolutions) the subject of numerous needs assessments,45–51 randomized clinical trials,52–56 and field tests.57,58 Studies have demonstrated that CHESS can be widely accepted and used, improves patient quality of life and information competence, and in some cases leads to more efficient health service use.59–61

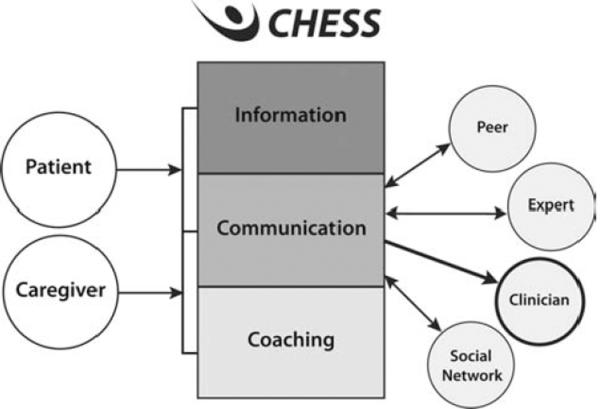

The new CHESS module, “Coping with Lung Cancer: A Network of Support” (CHESS-LC), moved CHESS in several new directions. Aside from being the first CHESS module addressing lung cancer, it was also one of the first to focus on advanced stage disease and end of life. Because of the severity of advanced-stage disease, particular focus was placed on supporting the caregiver as our primary target, rather than the patient. This module was one of the first to include the Clinician Report (CR) feature, allowing patients and caregivers to report their needs and patient symptom status to the clinical team via the Web site. CHESS-LC has expanded the social context addressed by CHESS; in addition to providing channels for communication among patients or between patients and an expert, CHESS now includes such channels for caregivers as well as communication with the oncology team and their own social support network of family and friends. This relationship is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Model of how CHESS connects patients/caregivers to key others in cancer experience.

Forthcoming data from a randomized control trial of CHESS-LC has demonstrated benefits of CHESS-LC. Caregivers with access to CHESS-LC, in comparison with an Internet control group, experienced less caregiver burden and less negative mood 6 months after initial access.62 A secondary analysis compared participants who received CHESS that included the CR with a subset of participants who had CHESS alone without the CR feature. The CR group demonstrated greater rates of improvement for symptoms reported as high (those that triggered a clinician alert for the CHESS+CR group).63 For symptoms not triggering an alert, rates of improvement appear similar between the groups. Sending of the clinician alert for highly distressing symptoms appears to positively affect symptom burden, potentially by allowing earlier intervention than otherwise might have occurred.64 Accordingly, such IHCSs have the potential to benefit patient and caregiver well-being through a variety of mechanisms.

CHESS Support for Decision Making

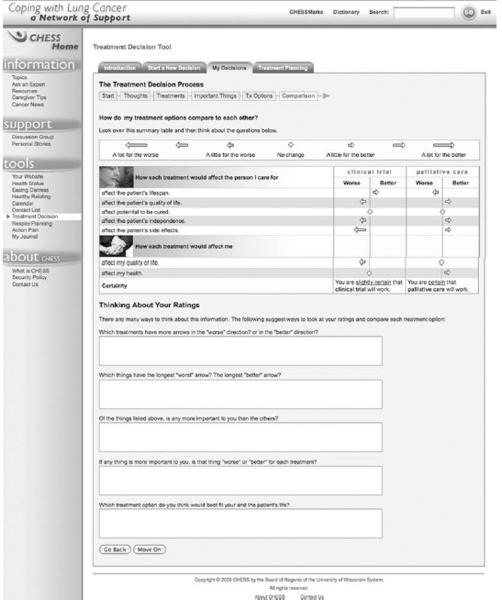

CHESS-LC integrates numerous services to provide patients and caregivers with information, communication, and coaching resources that can facilitate cancer and caregiving decision-making. Table 1 lists and describes CHESS services according to these IHCS delivery routes. CHESS decision support services are based on a decision-making model adapted from Charles and others.11 First, information must be brought to light demonstrating that options are available and therefore a choice, or decision, needs to be made. Next, identified options are deliberated upon, weighing preferences through evaluation of personal values and potential impact each option would have on those values. Based on this evaluation, one determines a preference and makes the decision. In extending this model, naturally once the choice is made, actions are necessary to implement the decision, and subsequently, evaluation of outcomes will suggest whether that decision had the desired outcome. If not, this information may bring to bear the need to reevaluate the decision, starting the process again with gathering information regarding options that are now available. CHESS facilitates decision making in 2 ways. Most directly, CHESS Decision Aids (described in Table 1; Coaching Services illustrated in Figure 2) walk the user through these decision-making and implementation steps. Less directly, but likely more comprehensively, the overall module is designed to facilitate patient and family caregiver engagement in their health care, including decision making.

Table 1.

CHESS Services Listed According to Service Category

| Information Services | |

| Frequently asked questions (FAQs) | Short answers to hundreds of common lung cancer questions; e.g., “How does chemotherapy work?” or “How do I know if I have depression?” |

| Instant library | Full-text articles on lung cancer from scientific journals and the popular press; e.g., “Do I Have to Die in Pain?” (PBS) |

| Resource directory | Descriptions of and contacts for lung cancer organizations |

| Web links | Links to high-quality content in health-related and non–health-related sites |

| Cancer news | Summaries of lung cancer news and research; e.g., “Erlotinib Improves Survival in Stage III NSCLC,” August 2009 |

| Personal stories | Real-life text accounts of how patients and caregivers cope with cancer |

| Caregiver tips | Brief suggestions on topics written by experts and other CHESS users |

| Communication Services | |

| Discussion groups | Limited-access, facilitated online support groups for—separately—patients, caregivers, and bereaved caregivers |

| Ask an expert | Confidential expert responses to patient and caregiver questions |

| Personal Web page | Guidance for setting up a patient's own bulletin board and interactive calendar with family and friends to share updates and request help |

| Clinician report | Three types: On Demand gives a summary report on a patient to a clinician who logs into CHESS. Threshold Alert sends an e-mail notice to the clinician when the patient exceeds a threshold on a symptom. Clinic Visit Report sends an e-mail notice to the clinician 2 days before a patient's scheduled clinic visit, suggesting that the clinician look at the report. |

| Coaching and Training Services | |

| Health status | Prompts users to enter data and provides graphs showing how patient health status is changing |

| Decision aids | Helps patients and caregivers think through difficult decisions by learning about options, clarifying values, and understanding consequences, e.g., Treatment Decision Aid or Respite Decision Aid |

| Easing distress | Uses principles of cognitive–behavioral therapy to help patients and caregivers identify emotional distress and cope with it |

| Healthy relating | Teaches techniques to increase closeness and decrease conflict |

| Action plan | Guides patients and caregivers in building a plan for change, including identifying and overcoming obstacles |

Figure 2.

Output page of the CHESS treatment decision aid.

Throughout CHESS, a number of services inform users about the disease and treatment options. The most direct are the information services, which provide resources describing the disease, treatment course and options, potential side effects, and other points of consideration. However, users also learn of options via communication services from peers who describe their treatment course and actions taken. The “Ask an Expert” service is available for more specific, detailed questions. The information, communication, and coaching services all help users engage in deliberation and decision-making. For example, “Discussion Group” and “Personal Stories” allow users to explore other patients' decision-making experiences, assisting users as they evaluate their own options and the potential consequences. Information services also address communication with the health care team, providing instruction in communication skills such as questions to ask before making a treatment decision. Furthermore, CHESS may facilitate shared decision deliberation by supporting communication between the patient and her or his social support network. Coaching services like “Healthy Relating” provide instruction on communication techniques for difficult discussions, such as end-of-life decision-making. By providing the same information and support to family members, the system may encourage family participation at an equivalent level of knowledge and understanding. By understanding available options, potential outcomes, and one's own preferences, as well as those of one's clinician and caregiver, patients may be more fully engaged and better prepared to select the option most in line with their individual needs and values. Finally, “Easing Distress” (a coaching and training service) and the information services guide users in dealing with the emotional difficulties inherent in this difficult decision-making process.

Unlike decision aids that stop at the decision itself, CHESS also extends decision support to implementing and evaluating the decision. Once an option is chosen, users can find support in taking action to implement their choices, whether by developing a plan for change via “Action Plan” or getting support from others with “Discussion Group” or “Personal Website.” The “Treatment Decision Aid” offers direct instruction on how to implement the decision, including coaching in talking with clinicians and family about the decision. Furthermore, the information services provide information relevant to the chosen option, which can help in preparing for next steps.

Finally, after the user acts on the decision, decision outcomes are evaluated based on personal progress. For decisions between treatment options, health status assessments can be important sources of clinical data for both the patient and the clinical team. Such data, as managed through the CR, may indicate to the clinical team that a treatment option may be causing problems or is ineffective, providing an early alert to examine new treatment options. The dynamic nature of cancer lends many decision opportunities across the illness trajectory. CHESS provides continuity as a single resource to enable the user to be fully engaged in care and decision making across the full cancer spectrum, including diagnosis, treatment, survivorship or end of life, and—for caregivers—bereavement.

CHESS Development

For the CHESS-LC Web site development, a comprehensive needs assessment approach was used involving a combination of individual and group interviews and a survey instrument. Interview data served as the foundation for the development of a survey instrument that could assess which needs were important at 10 specific events along the cancer trajectory, as well as caregiver bereavement. From the interviews we were able to generate and refine a list of 104 specific caregiver needs. Although importance ratings would have been ideal for each need item at each event, this would require 1040 rankings, which would have been far too burdensome for survey respondents. Therefore, to achieve a compromise between respondent burden and researcher assessment needs, we created a checklist that linked caregiver needs to specific illness events by asking whether they “wanted or would want information on” each individual need item at each of 10 key experiences of the cancer trajectory. Although these data are not as rich as qualified ratings, the checklist allowed us to gather self-report of changes in needs over a variety of key cancer experiences.65

CHESS Implementation

Although CHESS was implemented within the context of a clinical trial, we examined recruitment efforts, patient training benefits, and user feedback to lend insight into adoption issues relevant to other implementation contexts.

Recruitment

As a clinical trial, CHESS was introduced to patients and caregivers through individual in-person contacts. This method has been very successful with previous CHESS trials for early-stage breast cancer patients, where study recruitment rates were consistently at least 75%.57 However, the recent advanced lung cancer caregiver study struggled with recruitment rates of only 56%.66 This dramatic difference between these populations and types of studies sparked exploration of reasons for low recruitment in the lung cancer study.66 When patients and caregivers declined study participation, they were routinely asked, “Would you mind telling us your reason for declining?” Open-ended responses often highlighted the computer as a barrier for 2 reasons. First, many were not familiar with using a computer and, in the midst of a health crisis, did not view the study as an opportunity for beginning use, even though one-on-one training was offered. This reluctance to use the technology may reflect an older patient population, as some clearly stated they were “too old” to take part in a computer study. In contrast, some individuals already used the Internet to learn about cancer and did not believe CHESS would offer any additional benefits. Still others believed they were getting all they needed from another source, particularly their physician. Although some resistance to technology may lessen as computers become further integrated into daily life and culture, the variety of resource preferences illustrates the importance of developing interventions that will appeal to the user's preferred format for receiving information and support resources (e.g., clinicians, pamphlets, video, computer, portable device).

User training

Although there is encouraging evidence that CHESS can produce positive outcomes,53,54,67 it may not be enough to simply provide such resources. Training on the use of CHESS may be an important factor in maximizing benefits, particularly for those with lower literacy.68 Recently, a study examined the impact of receiving CHESS system training on later CHESS use.69 Of the 216 women participating in the CHESS breast cancer study, 136 women were trained (including introduction to the variety of CHESS services) via CHESS staff whereas 70 opted out of training. Participation in training predicted higher levels of CHESS use. Training potentially affects later system use in a variety of ways. First, it may help expose users to the full range of services that are available within an IHCS, here CHESS. Second, training may broadly increase users' competence in using such systems. Third, receiving personalized training may increase users' sense of connection to the system and its support staff, which motivates greater use of the IHCS.

This is an important finding in light of previous CHESS studies indicating that higher levels of use for some services is associated with improved outcomes.50,60 Additionally, some patterns of CHESS use, like more purposeful48 or continuous use,70 confer greater benefits than others.54,60,71–73 Accordingly, if greater IHCS use and certain kinds of use lead to improved benefits, then training users to use the system in the most effective fashion may be a key element in generating intended IHCS benefits. However, training yields additional delivery costs, and the best amount of training to maximize IHCS benefit is not known. Further cost–benefit analysis as well as alternative methods for training should be evaluated to establish appropriate guidelines.

Clinicians' perspectives

In addition to addressing patient and caregiver needs, the CHESS CR service was designed to facilitate the clinicians' practice by establishing more effective communication regarding patient symptoms among patients, caregivers, and the clinical team. CHESS assesses patient health status upon a patient's and/or caregiver's first login within a week or on demand. Users rate 10 common cancer symptoms (e.g., pain, fatigue, depression, or loss of appetite) on a 10-point distress scale. If symptom distress is rated 7 or higher, CHESS instantly sends an e-mail to the clinical team. Data are also summarized and charted over time (see Figure 3), and e-mail notices reminding the clinician that the CR is available are sent to the clinic team 2 days prior to the patient's scheduled clinic visit. In CHESS-LC development, clinicians participated in early development and prototyping to inform symptom selection and format for reports. Critical challenges of designing the CR are described by DuBenske and others.64

In designing the CHESS CR service, where clinician adoption was an essential element, the designers highlighted flexibility to suit the needs of a variety of organizational structures. Clinicians were able to select which members of their clinical team received the e-mail alerts of patient symptom thresholds. Furthermore, although the design of the report was intended to provide easy access to detailed information through interactive Web links, clinicians were also able to print out reports for quick reference of general data or to possibly include in the patient's medical chart. Although this customizability of the system facilitated the implementation process, challenges existed in the inability to merge the CR with existing clinic practice guidelines, such as the existing electronic medical record (EMR) system or paper chart. Flexibility to meet individual settings' needs will likely increase system adoption. Accordingly, IHCS should be designed to be integrated seamlessly within existing medical record formats, using consistent and familiar data presentation and design features.

Despite staff, patient, and caregiver training on the CR and recognition of the potential merit in using the system, the ongoing promotion of the system to maintain enthusiasm for CR use was challenging.64 Some clinicians indicated that the assessed symptoms were already frequently monitored at clinic visits, therefore limiting the usefulness of the CR. Accordingly, systems need to be designed around the needs of those they plan to serve, offering functionality that clearly fulfills a need. In this case, clinicians did participate in early needs assessments and offered these symptoms as key issues to track for their patients. However, it may not have been clear at the development and prototyping stages exactly how the CR would fit into the clinicians' practices to be able to predict what would be most useful to them. Using their current practice as a model for development may have restricted problem formulation and innovation, rendering a more duplicative rather than enhanced tool for their clinical practice.

Another factor limiting the usefulness of the CR was that clinicians perceived that the system as primarily used by caregivers rather than patients.64 Although clinicians reported that being aware of both patient and caregiver perceptions had some merit, the clinicians were concerned with how to address caregiver reports that were not substantiated by the patient. One privacy issue that remains debated is whether to initiate patient contact based on information provided solely by the caregiver. However, given that advanced-stage patients may be suffering from severe symptoms that prohibit sitting at the computer to enter their information, involvement of the caregiver may be crucial for timely and necessary care. Innovative approaches are needed to overcome such hurdles to enhance cancer care.

CONCLUSION

IHCSs have the potential to serve as a single place for trusted information, decision support, supportive communication, and coaching across the disease continuum. But to create effective systems, developers of IHCSs need to be comprehensive in both their approach to content development and the content itself. A thorough needs assessment addressing all target users is critical: health care organizations that will adopt the systems, clinicians who will promote and interface with them, and patients and caregivers who will use them. Once these needs are understood, plans for systems to meet those needs can be designed. With the variety of technical devices and communication channels available, the type of technology used should be carefully considered. Content is also a critical element, and the technical device used may have implications for information volume and format. Both technology and content should be prototyped and/or tested for usability and feasibility. Finally, implementation strategies should address the timing, personnel, and environmental factors involved, to ensure successful uptake and continued use of the IHCS. Early feedback from all interested parties can be effective in directing necessary adaptations to facilitate continued use and benefit from the IHCS.

ACKNOWLEGEMENTS

The Eisenberg White Paper Series is supported through a contract (HHSA290200810015C) with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ). The author(s) of this article are responsible for its content.

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (1 P50 CA095817-01A1) and the National Institute of Nursing Research (RO1 NR008260-01).

REFERENCES

- 1.Living Beyond Cancer . Finding a New Balance, President's Cancer Panel, 2003– 2004. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health; Washington, DC: May, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barg F, Pasacreta J, Nuamah I, Robinson K. A description of a psychoeducational intervention for family caregivers of cancer patients. J Child Fam Nurs. 1998;4:394–13. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speice J, Harkness J, Laneri H, et al. Involving family members in cancer care: focus group considerations of patients and oncological providers. Psychooncology. 2000;9:101–2. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200003/04)9:2<101::aid-pon435>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.James N, Daniels H, Rahman R, McConkey C, Derry J, Young A. A study of information seeking by cancer patients and their carers. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2007;19:356–62. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardwick C, Lawson N. The information and learning needs of the caregiving family of the adult cancer patient. Eur J Cancer Care. 1995;4:118–21. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2354.1995.tb00068.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.DuBenske LL, Wen KY, Gustafson DH, et al. Caregivers' needs at key experiences of the advanced cancer disease trajectory. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hileman JW, Lackey NR. Self-identified needs of patients with cancer at home and their home caregivers: a descriptive study. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1990;17(6):907–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brennan PF. Patient-focused technology and the health care delivery system. In: Gustafson DH, Brennan PF, Hawkins RP, editors. Investing in eHealth: What it Takes to Sustain Consumer Health Informatics. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lynn J. Reforming Health Care for the Last Years of Life. University of California Press; London, UK: 2004. Sick to Death and Not Going to Take It Anymore! [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cayton H. The flat-pack patient? Creating health together. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;62:288–90. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Charles C, Gafni A, Whelan T. Decision making in the physician–patient encounter: revisiting the shared treatment decision making model. Soc Sci Med. 1999;49(5):651–61. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weisman AD. Coping With Cancer. McGraw Hill; New York: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brashers DE, Goldsmith DJ, Hsieh E. Information seeking and avoiding in health contexts. Hum Comm Res. 2002;28:258–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eysenbach G. The impact of the Internet on cancer outcomes. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53:356–71. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.53.6.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen H, Haley WE, Robinson BE, Schonwetter RS. Decisions for hospice care in patients with advanced cancer. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(6):789–97. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Connor AM, Fiset V, DeGrasse C, et al. Decision aids for patients considering options affecting cancer outcomes: evidence of efficacy and policy implications. NCI Monogr. 1999;25:67–80. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jncimonographs.a024212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowman KW. Communication, negotiation, and mediation: dealing with conflict in end of life decisions. J Palliat Care. 2000;16(Suppl.):S17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang AY, Siminoff LA. The role of the family in treatmentdecision making by patients with cancer. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2003;30(6):1022–8. doi: 10.1188/03.ONF.1022-1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casarett D, Karlawish J, Morales K, Crowley R, Mirsch T, Asch D. Improving the use of hospice services in nursing homes: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Assoc. 2005;294(2):211–7. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.2.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pearlin L, Mullan J, Semple S, Skaff M. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of the concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583–94. doi: 10.1093/geront/30.5.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pasacreta J, Barg F, Nuamah I, McCorkle R. Participant characteristics before and 4 months after attendance at a family caregiver cancer education program. Cancer Nurs. 2000;23(4):295–303. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200008000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Halford W, Scott J, Smythe J. Couples and coping with cancer: helping each other through the night. In: Schmaling K, Goldman Sher T, editors. The Psychology of Couples and Illness: Theory, Research and Practice. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 2000. pp. 135–67. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Donnelly J, Kornblith A, Fleishman S, et al. A pilot study of interpersonal psychotherapy by telephone with cancer patients and their caregivers. Psychooncology. 2000;9:44–56. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1611(200001/02)9:1<44::aid-pon431>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gustafson DH, Brennan PF. Key learning and advice for implementers. In: Gustafson DH, Brennan PF, Hawkins RP, editors. Investing in eHealth: What it Takes to Sustain Consumer Health Informatics. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gustafson DH, Fellows J. Considerations for successful implementation of newly adopted technologies. In: Gustafson DH, Brennan PF, Hawkins RP, editors. Investing in eHealth: What it Takes to Sustain Consumer Health Informatics. Springer; New York: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Northouse LL, Dorris G, Charron-Moore C. Factors affecting couples' adjustment to recurrent breast cancer. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(1):69–76. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00302-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manne S, Dougherty J, Veach S, Kless R. Hiding worries from one's spouse: protective buffering among cancer patients and their spouses. Cancer Research Therapy and Control. 1999;8:175–88. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Coyne JC, Smith DAF. Couples coping with a myocardial infarction: a contextual perspective on wives' distress. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1991;61(3):404–12. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.61.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Manne S, Alfieri T, Taylor K, Dougherty J. Spousal negative responses to cancer patients: the role of social restriction, spouse mood, and relationship satisfaction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67(3):352–61. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manne S, Taylor K, Dougherty J, Kemeny N. Supportive and negative responses in the partner relationship: their association with psychological adjustment among individuals with cancer. J Behav Med. 1997;20(2):101–25. doi: 10.1023/a:1025574626454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: an interactional perspective. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Strecher V. Internet methods for delivering behavioral and health-related interventions (eHealth) Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2007;3:53–76. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ziebland S, Chapple A, Dumelow C, Evans J, Prinjha S, Rozmovits L. How the internet affects patients' experience of cancer: a qualitative study. Br Med J. 2004;328:564–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7439.564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Consumer use of computerized applications to address health and health care needs. 2009 Contract No. HHSP233200800001T. Available from: http://aspe.hhs.gov/sp/reports/2009/consumerhit/report.shtml#TOC.

- 35.O'Connor A, Wennberg J, Legare F, et al. Toward the “tipping point”: decision aids and informed patient choice. Health Aff. 2007;26(3):716–25. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.3.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klemm WR. Use and mis-use of technology for online, asynchronous collaborative learning. In: Roberts TS, editor. Computer- Supported Collaborative Learning in Higher Education. Idea Group Publishing; Hershey, PA: 2005. pp. 172–200. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Given BS, Kozachik C, Collins D, Devoss D, Given C. Caregiver role strain. In: Maas M, Buckwalter K, Hardy M, Tripp-Reimer T, Titler M, editors. Nursing Care of Older Adults Diagnosis: Outcome and Interventions. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 2001. pp. 679–95. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kinsella G, Cooper B, Picton C, Murtaugh D. A review of measurement of caregiver and family burden in SOP care. J Palliat Care. 1998;14(2):37–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychologist. 2000;55(1):68–78. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deci EL, Ryan RM. The “what” and “why” of goal pursuits: human needs and the self-determination of behavior. Psychol Inq. 2000;11:227–68. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deci E, Ryan R. Intrinsic Motivation and Self-Determination in Human Behavior (Perspectives in Social Psychology) Plenum; New York: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gremler D. The critical incident technique in service research. J Serv Res. 2004;7(1):65–89. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Snyder C. Paper Prototyping: The Fast and Easy Way to Refine User Interfaces. Morgan Kaufmann; San Francisco: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nielsen J. Usability Engineering. Academic Press/AP Professional; Cambridge, MA: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gustafson DH, Johnson P, Molfenter T, Patton T, Shaw B, Owens BH. Development and test of a model to predict adherence to a medical regimen. J Pharm Technol. 2001;17:198–208. [Google Scholar]

- 46.McTavish FM, Hawkins RP, Gustafson DH, Pingree S, Shaw BR. Experiences of women with breast cancer: exchanging social support over the CHESS computer network. J Health Comm. 2000;5(2):135–59. doi: 10.1080/108107300406866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gustafson DH, Julesberg K, Stengle W, McTavish FM, Hawkins RP. Assessing costs and outcomes of providing computer support to underserved women with breast cancer: a work in progress. Electronic Journal of Communication. 2001;11(3&4) [Google Scholar]

- 48.McTavish FM, Pingree S, Hawkins RP, Gustafson DH. Cultural differences in use of an electronic discussion group. J Health Psychol. 2003;8(1):105–17. doi: 10.1177/1359105303008001447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shaw BR, Hawkins R, McTavish F, Pingree S, Gustafson DH. Effects of insightful disclosure within computer mediated support groups on women with breast cancer. Health Comm. 2006;19(2):133–42. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shaw BR, Han JY, Hawkins RP, Stewart J, McTavish FM, Gustafson DH. Doctor- patient relationship as motivation and outcome: examining uses of an interactive cancer communication system. Int J Med Inform. 2006;76(4):274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meis T, Gaie M, Pingree S, et al. Development of a tailored, internet-based smoking cessation intervention for adolescents. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2002;7(3):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Boberg EW, et al. Impact of patient centered computer-based health information and support system. Am J Prev Med. 1999;16:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(98)00108-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:435–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gustafson DH, McTavish FM, Hawkins RP. Computer-based support systems for women with breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1999;281:1268–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.14.1268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Japuntich SJ, Zehner ME, Smith SS, et al. Smoking cessation via the Internet: a randomized clinical trial of an Internet intervention as adjuvant treatment in a smoking cessation intervention. Nicotine Tob Res. 2006;8(Suppl. 1):S59–67. doi: 10.1080/14622200601047900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patten CA, Croghan IT, Meis TM, et al. Randomized clinical trial of an internet-based versus brief office intervention for adolescent smoking cessation. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;64(1–3):249–58. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gustafson D, McTavish F, Stengle W, et al. Reducing the digital divide for low-income women with breast cancer: a feasibility study of a population-based intervention. J Health Comm. 2005;10(Special Issue, Suppl. 1):173–93. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.McTavish FM, Hawkins RP, Gustafson DH, Pingree S, Shaw BR. Experiences of women with breast cancer: exchanging social support over the CHESS computer network. J Health Comm. 2000;5(2):135–59. doi: 10.1080/108107300406866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gustafson DH, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, et al. Effect of computer support on younger women with breast cancer. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:435–45. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016007435.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shaw B, Han J, Hawkins R, Stewart J, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Doctor-patient relationship as motivation and outcome: examining uses of an interactive cancer communication system. Int J Med Inform. 2007;76(4):274–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Shaw BR, Han JY, Baker T, et al. How women with breast cancer learn using interactive cancer communication systems. Health Educ Res. 2007;22(1):108–19. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Namkoong K, et al. Effects of an interactive cancer communication system on lung cancer caregivers' quality of life and negative mood: a randomized clinical trial. Psychooncology. 2010;19(Suppl. 2):100. [Google Scholar]

- 63.DuBenske LL, Gustafson DH, Chih M, Hawkins RP, Dinauer S, Cleary JF. Alerting clinicians to caregiver's ratings of cancer patient symptom distress: a randomized comparison of the clinician report (CR) service. Psychooncology. 2010;19(Suppl. 2):115. [Google Scholar]

- 64.DuBenske LL, Chih MY, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, Cleary JF. Development and implementation of a clinician reporting system for advanced stage cancer: initial lessons learned. JAMIA. 2008;15(5):679–86. doi: 10.1197/jamia.M2532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.DuBenske LL, Wen KY, Gustafson DH, et al. Caregivers' needs at key experiences of the advanced cancer disease trajectory. Palliat Support Care. 2008;6:1–8. doi: 10.1017/S1478951508000400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buss MK, DuBenske LL, Dinauer S, Gustafson DH, McTavish F, Cleary JF. Patient/caregiver influences for declining participation in supportive oncology trials. J Support Oncol. 2008;6:168–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gustafson DH, Hawkins R, McTavish F, et al. Internet-based interactive support for cancer patients: are integrated systems better? J Comm. 2008;58(2):238–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2008.00383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shaw B, Gustafson D, Hawkins R, et al. How underserved breast cancer patients use and benefit from eHealth programs: implications for closing the digital divide. Am Behav Sci. 2006;49:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDowell H, Kim E, Shaw B, Han JY, Gumieny L. Predictors and effects of training on an online health education and support system for women with breast cancer. J Comput Mediat Commun. 2010;15:412–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2010.01516.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Han JY, Hawkins RP, Shaw B, Pingree S, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Unraveling uses and effects of an interactive health communication system. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2009;53:112–33. doi: 10.1080/08838150802643787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Han JY, Shaw B, Hawkins RP, Pingree S, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Expressing positive emotions within online support groups by women with breast cancer. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:1002–7. doi: 10.1177/1359105308097963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wise M, Han JY, Shaw B, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Effects of using online narrative and didactic information on healthcare participation for breast cancer patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;70:348–56. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.11.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaw B, Han JY, Hawkins RP, McTavish F, Gustafson DH. Communicating about self and others within an online support group for women with breast cancer and subsequent outcomes. J Health Psychol. 2008;13:930–9. doi: 10.1177/1359105308095067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]