Abstract

Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) plays a vitally important role in the blood coagulation pathway. Recent studies indicated that TFPI induces apoptosis in vascular smooth-muscle cells (VSMCs) in animals. The present study investigated whether the TFPI gene could also induce apoptosis in human vascular smooth-muscle cells (hVSMCs). Such cells were isolated from human umbilical arteries and subsequently transfected with pIRES-TFPI plasmid (2 μg/mL). MTT assaying and cell counting were applied to measure cell viability and proliferation, RT-PCR was utilized to analyze TFPI gene expression in the cells. Apoptosis was analyzed by fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). Several key proteins involved in apoptosis were examined through Western blotting. It was shown that TFPI gene transfer led to its increased cellular expression, with a subsequent reduction in hVSMC proliferation. Further investigation demonstrated that TFPI gene expression resulted in lesser amounts of procaspase-3, procaspase-8 and procascase-9, and an increased release of mitochondrial cytochrome c (cyt-c) into cytoplasm, thereby implying the involvement of both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways in TFPI gene-induced apoptosis in hVSMCs.

Keywords: tissue factor pathway inhibitor, vascular smooth muscle cells, apoptosis

Introduction

Restenosis, a major complication leading to recurrent acute coronary diseases and even death (Douglas, 2007), occurs in 30%–40% of the patients following percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA). To date, the underlying mechanisms are not yet completely understood, even though several etiological factors have already been identified, these including the proliferation and migration of VSMCs, platelet adherence and aggregation, thrombus formation, the infiltration of inflammatory cells, as well as vascular remodeling (Ferns and Avades, 2000; Kaiura et al., 2000; Santin et al., 2004).

The tissue factor (TF) is a key initiator of the coagulation cascade (DelGiudice and White, 2009). It also participates in other cellular processes including migration and proliferation of VSMCs (Ducasse et al., 2003). It has been shown to mediate a prolonged prothrombotic state after balloon angioplasty, by generating active serine proteases of the coagulation cascade, these including factor VIIa (VIIa), factor Xa, and thrombin (Ducasse et al., 2003). These proteases promote the development of restenosis by both thrombotic and non-thrombotic mechanisms, exerting mitogenic and chemotactic effects on VSMCs and by eliciting a proinflammatory response (Ko et al., 1996; Senden et al., 1998). Hence, the possibility of blocking TF activity could lead to a reduction in thrombosis, local inflammation, and the proliferation and migration of VSMCs, and, consequently, intimal hyperplasia in injured blood vessels.

The tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI), a Kunitz-type protease inhibitor, exerts feedback inhibition on the TF/VIIa-complex in an Xa-dependent manner (Broze et al., 1990). It has been attracting increasing research effort as a potential agent for curing restenosis, since it was found to attenuate thrombus formation (Nishida et al., 1999), reduce local inflammatory responses induced by injury to blood vessels, and suppress the proliferation and migration of VSMCs (Kamikubo et al., 1997). Research, based on animal models, has amply confirmed that TFPI, in the form of either recombinant protein or gene, reduce restenosis induced by blood vessel injury (Hamuro et al., 1998; Hembrough et al., 2001; Sato et al., 1997, 1999; Yin et al., 2002). Since VSMCs proliferation and migration plays a central role in the progression of neointimal hyperplasia, it is of particular interest to understand the mechanism through which TFPIs modulate the former of the two.

Apoptosis induction is one of the major strategies for reducing cell proliferation. Recent investigation using animal models has revealed that adenovirus-mediated TFPI gene transfer induced apoptosis in VSMCs through the intrinsic pathway (Fu et al., 2008), adding more evidence to a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying its anti-proliferative behavior. Even so, little is known regarding the impact of the TFPI gene on hVSMCs.

The current study was designed to investigate whether TFPI could induce also apoptosis in hVSMCs, as well as the underlying mechanisms involved. We could show that TFPI over-expression in human VSMCs induced cellular apoptosis through both intrinsic and extrinsic apoptotic pathways.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and identification of VSMCs

hVSMCs were isolated from human umbilical artery according to the method described by Li et al. (2003). Briefly, 3–5 cm sections of arteries isolated from the human umbilical cord were perfused with a physiological saline solution to remove the remaining internal blood. This was done by means of a 20 mL syringe connected to a needle. After cutting open and gently scraping off the intima, the blood vessels were sectioned into even smaller pieces of 2–3 mm3, for culture in 25 cm2 flasks, with DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal-calf serum (FBS) and 10% human AB serum. Culture itself was by incubation in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator at 37 °C. The medium was refreshed every 3 days until the cells reached about 90% confluence. Purification of hVSMCs was carried out by differential attachment, the cells of passage 3 being used for further investigation. The isolated hVSMCs were identified by immunocytochemical staining, using monoclonal antibodies against smooth muscle actin-α, according to manufacturer’s instructions, with a non-specific serum as antibody control.

Construction of the TFPI encoding plasmid

In order to construct a recombinant plasmid expressing TFPI in eukaryotic cells, TFPI cDNA, a generous gift from Professor George J. Broze Jr. at Washington University School of Medicine, was inserted into the pIRES 1-neo plasmid by using standard DNA recombination techniques. The resulting plasmid pIRES-TFPI was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Detection of TFPI expression in VSMCs by RT-PCR

hVSMCs were seeded into 25 cm2 flasks and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Thereafter, the cells were divided into 3 groups (8 flasks/group) and treated with pIRES-TFPI plasmid (2 μg/mL), pIRES 1-neo plasmid (2 μg/mL) and fresh medium, respectively, using lipofectamine as transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was extracted with Trizol reagent 3 days after transfection, and subsequently amplified by RT-PCR with TFPI specific primers (5′-GGAAGAAGATCCTGGAATATGTCGAGG -3′, and 5′-CTTGGTTGATTGCGGAGTCAGGGAG-3′). GAPDH was amplified as internal control, using the following primers: 5′-ACCACAGTCCATGCCATCACT-3′ and 5′-TCCACACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′. The amplified DNA was analyzed through electrophoresis followed by optical density scanning using a GDS8000 Gel Documentation and Analysis System (Cambridge, UK).

Testing of cell viability by MTT assay

hVSMCs were seeded into a 96-well plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells were divided into 3 groups (8 wells/group) and treated with pIRES-TFPI plasmid (2 μg/mL), pIRES 1-neo plasmid (2 μg/mL) and fresh medium, respectively, using lipofectamine as transfection reagent according to manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was measured 3, 5 and 7 days after DNA transfection by MTT assay as described previously (Mosmann, 1983). The test was repeated twice.

Measurement of cell proliferation

hVSMCs were seeded into a 48-well plate and incubated at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Cells were divided into three groups, and treated with pIRES-TFPI plasmid (2 μg/mL), pIRES 1-neo plasmid (2 μg/mL) and fresh medium, respectively, using lipofectamine as transfection reagent, according to manufacturer’s instructions. The cells were counted using a cytometer from 2 to 7 days after DNA transfection. The experiment was repeated twice.

Flow-cytometry for cell apoptosis analysis

hVSMCs were seeded into 25 cm2 flasks and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. The cells, divided into three groups, were treated with pIRES-TFPI plasmid (2 μg /mL), pIRES 1-neo plasmid and fresh medium, respectively, using lipofectamine as transfection reagent, according to manufacturer’s instructions. Harvesting was done 5 and 7 days after transfection. Cells were first washed with PBS and counted, and then suspended in a 1x binding buffer at a density of 1 x 106 cells/mL. After transfer to a 5 mL culture tube, 100 μL of the cell suspension (1 x 105 cells) was transferred to a 5 mL culture tube and then gently mixed with 5 μL of FITC-Annexin V and 10 μL of PI solution. After a 15 min’s incubation in the dark at RT, 400 μL of 1x binding buffer was added to each tube, followed by FACS analysis (NJ, USA). The experiment was repeated twice.

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed to verify the amount of the proteins involved in apoptosis. In brief, 5 days after DNA transfection, the cells were harvested, washed with PBS, and resuspended in cold lysis buffer containing PMSF (1 mM). The cell lysates were subsequently incubated on ice for 30 min and centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4 °C. The amount of protein was determined using a Bradford protein-assay kit. Aliquots of the cell lysates containing 50 μg of proteins were mixed with SDS-sample buffers and subjected to electrophoresis on 10% PAGE gels followed by routine Western blotting analysis using antibodies against procaspase-8, procaspase-9, procaspase-3, cyt-c, and β-actin (Santa Cruz, USA). The experiment was repeated three times and the results were presented as mean values of the three tests.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using one way ANOVA (one-way analysis of variance) followed by Bonferroni t-tests for comparisons with the control group. The values were presented as means ± SD of eight tests, and statistical significance was determined at p < 0.05.

Results

TFPI gene transfer led to elevated TFPI expression in hVSMCs

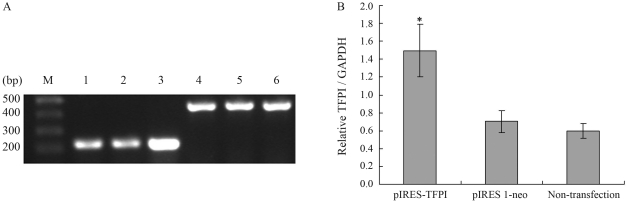

TFPI mRNA levels in hVSMCs were determined by RT-PCR, with simultaneously amplified GAPDH, as internal control. As shown in Figure 1A, a DNA fragment of around 230 bps was amplified by TFPI specific primers and a DNA fragment of around 500 bps by GAPDH specific primers. Figure 1B shows that the TFPI/ GAPDH ratio in cells treated with pIRES-TFPI (1.50) was significantly higher than in those treated with pIRES 1-neo (0.70) or normal ones (0.60). The fact of there being no significant difference in treatment between the pIRES 1-neo treated cells and normal cells indicates that TFPI gene transfer did, in fact, result in higher expression of TFPI.

Figure 1.

Analysis of RT-PCR amplification of TFPI by agarose gel electrophoresis. (A) M: DNA maker; 1: TFPI amplification in the non-transfection group; 2: TFPI amplification in pIRES 1-neo group; 3: TFPI amplification in the pIRES-TFPI group; 4: GAPDH amplification in the non-transfection group; 5: GAPDH amplification in the pIRES 1-neo group; 6: GAPDH amplification in the pIRES-TFPI group. (B) TFPI mRNA levels standardized by GAPDH. *p < 0.05 as compared to the pIRES 1-neo or non-transfection group (n = 8).

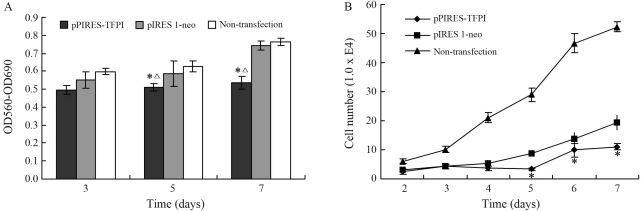

Suppressed cell viability and proliferation as a result of TFPI gene transfer

Both MTT assay and cell counting demonstrated that pIRES-TFPI gene transfer resulted in decreased cell viability and proliferation, in a time dependent manner, compared with pIRES 1-neo plasmid treatment, thereby inferring the inhibitory effect of the TFPI gene on VSMCs proliferation (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Cell viability measured by MTT. (A) Cell proliferation measured by cell counting. B *p < 0.05 as compared with the pIRES 1-neo group (n = 16); Δp < 0.05 as compared with the non-transfection group (n = 16).

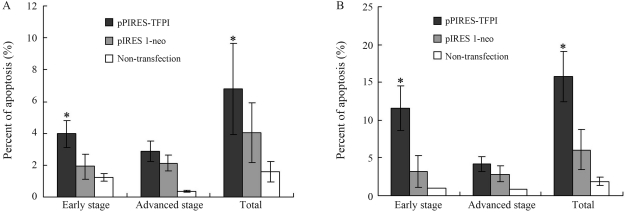

TFPI gene induced cell apoptosis in hVSMCs

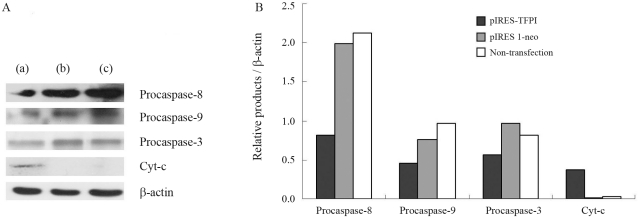

The results obtained demonstrated that TFPI gene transfer started to reveal its inhibitory effect on VSMC proliferation from the 5th day after DNA transfection (Figure 2). Thus, the 5th and 7th days post-transfection were chosen for observing the impact of TFPI gene transfer on cellular apoptosis. We found that the TFPI gene induced significantly higher cellular apoptosis in comparison to experimental controls (Figure 3). To further explore the underlying mechanisms, certain key proteins involved in apoptosis were analyzed through Western blotting, showing that TFPI gene transfer led to decreased expression of procaspase-3, procaspase-8 and procascase-9, and increased release of cyt-c into the cytoplasm in comparison to the control groups (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Cell apoptosis analysis at the 5th (A) and 7th (B) days after gene transfection. *p < 0.05 in comparison to the pIRES 1-neo group or the non-transfection group (n = 8).

Figure 4.

Western blot analysis for procaspase-8, procaspase-9, procaspase-3, and cyt-c. (A) Representative data of Western blotting for pIRES-TFPI treated group (a), pIRES 1-neo treated group (b) and non-transfection group (c); (B) protein levels standardized by β-actin. *p < 0.05 as compared with the pIRES 1-neo group (n = 3).

Discussion

Both the abnormal proliferation and migration of VSMCs contribute significantly to restenosis progression after cardiovascular intervention such as PTCA, which leads to high long-term failure rates of bypass surgery and angioplasty in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Therefore, the development of molecular strategies that effectively block such pathogenic cellular processes has been the focus of much research and many clinical trials over the past two decades (Kiernan et al., 2008, 2009).

VSMCs usually comprise two phenotypes, namely contractile and synthetic. The contractile phenotype cells are spindle-shaped with low frequency of proliferation, whereas the synthetic phenotype cells are rhomboid-shaped showing a high degree of protein synthesis, proliferation and migratory activity. It is generally agreed that contractile differentiated VSMCs are the typical phenotype of the vascular wall under most normal, physiological conditions, whereas synthetic dedifferentiated VSMCs only exist during developmental and pathological processes. In response to various stimuli including vascular injury, VSMCs switch from the quiescent contractile phenotype to the synthetic one, proliferate in media, and migrate from the media to the intima, where they undergo further proliferation leading to neointimal hyperplasia. Reduction of neointimal hyperplasia could be achieved either by regulating the cell cycle (cytostatic strategy), or by inducing cell-death, such as apoptosis (cytotoxic strategy).

Apoptosis normally occurs during development and aging, as a homeostatic mechanism to maintain cell populations in tissues. It also operates as a defense mechanism against cell-damage induced by diseases or noxious agents (Norbury and Hickson, 2001). The highly complex and sophisticated apoptosis mechanisms involve a cascade of molecular events. It is generally agreed that there are two major apoptotic pathways, the extrinsic or death receptor pathway and the intrinsic or mitochondrial pathway. Recent evidence demonstrates that the two pathways are linked and converge on the execution pathway (Igney and Krammer, 2002). The extrinsic pathway involves the binding of ligands to their corresponding death receptors, followed by a series of molecular events leading to auto-catalytic activation of procaspase-8 (Kischkel et al., 1995). In the intrinsic pathway, apoptosis is triggered by a varied array of intracellular signals that act directly on targets within the cell. All these signals induce changes in the inner mitochondrial membrane, thereby leading to opening of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore, loss of mitochondrial transmembrane potential, and the release of pro-apoptotic proteins, such as cyt-c, from intermembrane space into the cytosol (Saelens et al., 2004). Cyt-c binds to and activates Apaf-1, as well as procaspase-9, thereby leading to caspase-9 activation (Chinnaiyan, 1999; Hill et al., 2004). Both pathways end at the execution phase. Caspase-3, considered to be the most important of the executioner caspases, is activated by any one of the initiator caspases including caspase-8 and caspase-9.

As demonstrated in the current study, TFPI gene transfer could suppress the proliferation of neonatal VSMCs from human umbilical artery that share characteristics similar to those of synthetic VSMCs observed in restenosis lesions (Fujita et al., 1993). This is in line with a previous report showing TFPI gene-induced apoptosis in rat VSMCs by (Fu et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the current study showed that TFPI gene transfer reduced the expression of caspase 3, caspase 8, and caspase 9 and induced the release of cyt-c into the cytosol. This implies the involvement of both extrinsic and intrinsic pathways in TFPI gene-induced cellular apoptosis, contrary to that observed in rats, where only the intrinsic pathway was affected (Fu et al., 2008). The mechanisms underlying the difference in impact of the TFPI gene on apoptotic pathways needs to be further elucidated.

Acknowledgments

The authors are sincerely grateful to Professor G Broze Jr at Washington University School of Medicine for kindly providing the cDNA encoding TFPI. This research was supported by a grant from the Tianjin Science and Technology Committee, China (Grant number 06YFGPSH03700).

Footnotes

Associate Editor: Carlos F.M. Menck

References

- Broze GJ, Jr, Girard TJ, Novotny WF. Regulation of coagulation by a multivalent Kunitz-type inhibitor. Biochemistry. 1990;29:7539–7546. doi: 10.1021/bi00485a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chinnaiyan AM. The apoptosome: Heart and soul of the cell death machine. Neoplasia. 1999;1:5–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.neo.7900003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DelGiudice LA, White GA. The role of tissue factor and tissue factor pathway inhibitor in health and disease states. J Vet Emerg Crit Care. 2009;19:23–29. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-4431.2008.00380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglas JS., Jr Pharmacologic approaches to restenosis prevention. Am J Cardiol. 2007;100:10K–16K. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2007.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducasse E, Cosset JM, Eschwege F, Chevalier J, De Ravignan D, Puppinck P, Lartigau E. Hyperplasia of the arterial intima due to smooth muscle cell proliferation. Current data, experimental treatments and perspectives. J Mal Vasc. 2003;28:130–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferns GA, Avades TY. The mechanisms of coronary restenosis: Insights from experimental models. Int J Exp Pathol. 2000;81:63–88. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2613.2000.00143.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Zhang Z, Zhang G, Liu Y, Cao Y, Yu J, Hu J, Yin X. Adenovirus-mediated gene transfer of tissue factor pathway inhibitor induces apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells. Apoptosis. 2008;13:634–640. doi: 10.1007/s10495-008-0199-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Shimokado K, Yutani C, Takaichi S, Masuda J, Ogata J. Human neonatal and adult vascular smooth muscle cells in culture. Exp Mol Pathol. 1993;58:25–39. doi: 10.1006/exmp.1993.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamuro T, Kamikubo Y, Nakahara Y, Miyamoto S, Funatsu A. Human recombinant tissue factor pathway inhibitor induces apoptosis in cultured human endothelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1998;421:197–202. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)01559-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembrough TA, Ruiz JF, Papathanassiu AE, Green SJ, Strickland DK. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor inhibits endothelial cell proliferation via association with the very low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:12241–12248. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010395200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill MM, Adrain C, Duriez PJ, Creagh EM, Martin SJ. Analysis of the composition, assembly kinetics and activity of native Apaf-1 apoptosomes. EMBO J. 2004;23:2134–2145. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igney FH, Krammer PH. Immune escape of tumors: Apoptosis resistance and tumor counterattack. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71:907–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaiura TL, Itoh H, Kubaska SM, 3rd, McCaffrey TA, Liu B, Kent KC. The effect of growth factors, cytokines, and extracellular matrix proteins on fibronectin production in human vascular smooth muscle cells. J Vasc Surg. 2000;31:577–584. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamikubo Y, Nakahara Y, Takemoto S, Hamuro T, Miyamoto S, Funatsu A. Human recombinant tissue-factor pathway inhibitor prevents the proliferation of cultured human neonatal aortic smooth muscle cells. FEBS Lett. 1997;407:116–120. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00312-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan TJ, Yan BP, Cruz-Gonzalez I, Cubeddu RJ, Caldera A, Kiernan GD, Gupta V. Pharmacological and cellular therapies to prevent restenosis after percutaneous trans-luminal angioplasty and stenting. Cardiovasc Hematol Agents Med Chem. 2008;6:116–124. doi: 10.2174/187152508783955033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiernan TJ, Kiernan GD, Yan BD. Coronary artery restenosis: A paradigm of current treatment approaches. Minerva Cardioangiol. 2009;57:77–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kischkel FC, Hellbardt S, Behrmann I, Germer M, Pawlita M, Krammer PH, Peter ME. Cytotoxicity-dependent APO-1 (Fas/CD95)-associated proteins form a death-inducing signaling complex (DISC) with the receptor. EMBO J. 1995;14:5579–5588. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1995.tb00245.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko FN, Yang YC, Huang SC, Ou JT. Coagulation factor Xa stimulates platelet-derived growth factor release and mitogenesis in cultured vascular smooth muscle cells of rat. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:1493–1501. doi: 10.1172/JCI118938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S, Tian J, Liu J, Wan L, Lu X, Feng L, Sun M, Fan Y, Bu H, Li Y. Biological characteristics of human umbilical artery smooth muscle cells cultured in vitro and the preestablishment of immortalized cell line. Sichuan Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2003;34:189–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: Application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida T, Ueno H, Atsuchi N, Kawano R, Asada Y, Nakahara Y, Kamikubo Y, Takeshita A, Yasui H. Adenovirus-mediated local expression of human tissue factor pathway inhibitor eliminates shear stress-induced recurrent thrombosis in the injured carotid artery of the rabbit. Circ Res. 1999;84:1446–1452. doi: 10.1161/01.res.84.12.1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norbury CJ, Hickson ID. Cellular responses to DNA damage. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:367–401. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saelens X, Festjens N, Vande Walle L, van Gurp M, van Loo G, Vandenabeele P. Toxic proteins released from mitochondria in cell death. Oncogene. 2004;23:2861–2874. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santin M, Morris C, Harrison M, Mikhalovska L, Lloyd AW, Mikhalovsky S. Factors inducing in-stent restenosis: An in-vitro model. Med J Malaysia. 2004;59(Suppl B):93–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Asada Y, Marutsuka K, Hatakeyama K, Kamikubo Y, Sumiyoshi A. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor inhibits aortic smooth muscle cell migration induced by tissue factor/factor VIIa complex. Thromb Haemost. 1997;78:1138–1141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato Y, Kataoka H, Asada Y, Marutsuka K, Kamikubo Y, Koono M, Sumiyoshi A. Overexpression of tissue factor pathway inhibitor in aortic smooth muscle cells inhibits cell migration induced by tissue factor/factor VIIa complex. Thromb Res. 1999;94:401–406. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(99)00032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Senden NH, Jeunhomme TM, Heemskerk JW, Wagenvoord R, van’t Veer C, Hemker HC, Buurman WA. Factor Xa induces cytokine production and expression of adhesion molecules by human umbilical vein endothelial cells. J Immunol. 1998;161:4318–4324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin X, Yutani C, Ikeda Y, Enjyoji K, Ishibashi-Ueda H, Yasuda S, Tsukamoto Y, Nonogi H, Kaneda Y, Kato H. Tissue factor pathway inhibitor gene delivery using HVJ-AVE liposomes markedly reduces restenosis in atherosclerotic arteries. Cardiovasc Res. 2002;56:454–463. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00595-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]