Abstract

p63 is a master regulator of proliferation and differentiation in stratifying epithelia, and its expression is frequently altered in carcinogenesis. However, its role in maintaining proliferative capacity remains unclear. Here, we demonstrate that hypoproliferation and loss of differentiation in organotypic raft cultures of primary neonatal human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) depleted of the α and β isoforms of p63 result from p53–p21-mediated accumulation of retinoblastoma (Rb) family member p130. Hypoproliferation in p63-depleted HFKs can be rescued by depletion of p53, p21CIP1 or p130. Furthermore, we identified the gene encoding S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2), the recognition component of the SCFSkp2 E3 ubiquitin ligase, as a novel target of p63, potentially influencing p130 levels. Expression of Skp2 is maintained by p63 binding to a site in intron 2 and mRNA levels are downregulated in p63-depleted cells. Hypoproliferation in p63-depleted cells can be restored by re-expression of Skp2. Taken together, these results indicate that p63 plays a multifaceted role in maintaining proliferation in the mature regenerating epidermis, in addition to being required for differentiation.

Key words: Keratinocyte, Proliferation, p63

Introduction

The p53 family member p63 is crucial to the development of stratifying epithelia in human (Rinne et al., 2007), mouse (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999) and zebrafish (Lee and Kimelman, 2002). p63−/− mice exhibit severe developmental defects in tissues derived from stratifying epithelia and die perinatally because of an almost complete absence of mature epidermis (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). These phenotypes are mirrored in human syndromes caused by mutations of the gene encoding p63 (TP63) (Rinne et al., 2007).

Unlike p53, p63 is rarely mutated in tumours (Irwin and Kaelin, 2001); however, p63 expression is frequently increased in squamous cell carcinomas (reviewed in Deyoung and Ellisen, 2007), where the ΔN isoforms of p63 are thought to oppose the activity and anti-proliferative response of p53 family members. In addition, loss of expression of TA p63 isoforms has been shown in bladder carcinomas (Park et al., 2000) and recent data from TAp63-specific knockout mice indicates that TAp63 behaves as a tumour suppressor (Guo et al., 2009; Su et al., 2010), although the effects are dependent on tissue type and the expression of other p53 family members (Su et al., 2010). Taken together, these data suggest that p63 might act as a proto-oncogene or a tumour suppressor depending on the cellular context, isoforms and other p53 family members expressed.

This is perhaps not surprising, given the complicated nature of the TP63 gene, which encodes at least six isoforms (supplementary material Fig. S1A), a complexity mirrored in the other p53 family members. The six p63 isoforms are a result of alternative promoter usage producing transactivation domain (TA) or ΔN N-termini coupled with three C-terminal splice variants (α, β, γ), generating isoforms with differing as well as overlapping functions (reviewed in McDade and McCance, 2010). The predominant isoform expressed in basal keratinocytes and stratifying epithelia (Yang et al., 1998) is ΔNp63α, which contains a sterile alpha motif (SAM domain) and transcriptional inhibitory domain in its extended C-terminus, which can facilitate transcriptional repression in cis or trans. Regulation of p63 levels is further complicated by post-transcriptional targeting by microRNAs such as mir-203 (McKenna et al., 2010; Yi et al., 2008) or by being targeted for degradation by E3 ligases such as ITCH and FBW7 (Galli et al., 2010; Rossi et al., 2006).

Despite a large body of literature, the exact function of ΔNp63α in the post-developmental epidermis and whether this is influenced by other p63 isoforms or, indeed, p53 and p73 remains unclear. In the mature regenerating epidermis, depletion of all p63 isoforms in organotypic cultures results in hypoproliferation and loss of differentiation (Truong et al., 2006), similar to defects observed in knockout mice. Impaired proliferation can be rescued by simultaneous knockdown of p53; however, this is insufficient to induce differentiation. In addition, ΔNp63α and p53 have been shown to inversely regulate target genes such as p21CIP1 (p21) in the context of DNA damage (Schavolt and Pietenpol, 2007). Whether ΔNp63α-mediated inhibition of p53-induced target genes is important for normal epidermal morphogenesis remains unclear, as the p53 knockout mouse develops normal skin (Donehower et al., 1992) and is only altered in its ability to undergo differentiation as a protective mechanism following insult, such as UV-B treatment (Tron et al., 1998).

In addition to maintaining proliferation by opposing p53 functions, ΔNp63α has also been shown to inhibit notch signalling in the epidermis and the subsequent activation of p21 (Nguyen et al., 2006), which is required for cell cycle exit (Missero et al., 1995) during commitment to terminal differentiation. However, ΔNp63α also synergises with notch in the activation of keratin 1, a marker of early differentiation (Nguyen et al., 2006). Other evidence for a role in differentiation is the fact that ΔNp63α has been shown to induce expression of a number of genes involved in differentiation, such as IKKα, PERP, p57 and the notch ligand Jag-1 (Beretta et al., 2005; Candi et al., 2007; Candi et al., 2006; Ihrie et al., 2005).

Recent data from our laboratory using neonatal human foreskin keratinocytes (HFKs) indicates that p21 induction is important for proliferation and induction of differentiation (Wong et al., 2010). Here, we demonstrate that the predominant ΔNp63α isoform is important for regulation of p21 during differentiation and that p63 depletion results in p53-dependent aberrant activation of p21 and hypoproliferation. In addition, we identify accumulation of the retinoblastoma (Rb) family member p130 as a key event in the hypoproliferation observed in p63-depleted HFKs and demonstrate a novel role for p63 in regulating transcription of the S-phase kinase-associated protein (Skp2), which has been shown to modulate p130 levels and subsequent proliferation.

Results

Dynamic regulation of p21 is required for efficient epidermal differentiation

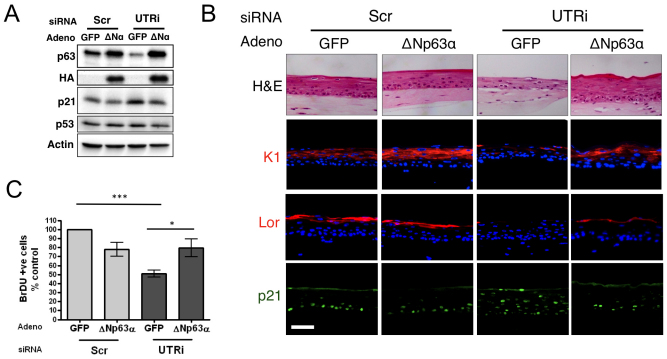

Organotypic raft cultures of neonatal HFKs represent an ideal model system to investigate the role of p63 isoforms in proliferation and differentiation. Therefore, we established stable and transient RNA interference (RNAi) models targeting a subset of p63 isoforms, with small interfering (si)RNA directed to either the 3′-UTR of the α and β isoforms (UTRi) or the DNA-binding domain of all isoforms (Pan) (supplementary material Fig. S1A). Initial experiments revealed that p63 depletion with UTRi and Pan RNAi resulted in hypoproliferation, as measured by the number of 5-bromodeoxyuridine (BrDU)-incorporating cells (Fig. 1A; supplementary material Fig. S1B,D), and loss of differentiation, as assessed by morphology and indirect immunofluorescence of early (keratin 1) and intermediate (loricrin) markers of differentiation (Fig. 1A,B; supplementary material Fig. S1C,E). We further confirmed that, similar to findings from Truong et al. (Truong et al., 2006), simultaneous p53 depletion fully restored proliferation with no rescue of differentiation (data not shown). Because we consistently observed increased p21 protein levels in p63-depleted cells (Fig. 1A), we further examined p21 expression in 3D organotypic raft cultures depleted for p63 by indirect immunofluorescent staining. This revealed not only increased levels of p21, but also altered localisation (Fig. 1B; supplementary material Fig. S1C). In scrambled control rafts, p21 is detected in the basal and immediately suprabasal layers, where cells are exiting the cells cycle, whereas p21 expression was detected throughout the p63-depleted rafts (Fig. 1B; supplementary material Fig. S1C). The altered localisation and levels of p21 could be rescued by adenoviral re-expression of the ΔNp63α isoform (Fig. 1A,B). We re-expressed ΔNp63α because it is expressed >20-fold more than the β and >100-fold more than the γ isoforms in cycling HFKs (supplementary material Fig. S1D). Expression of the ΔNp63α isoforms was sufficient to restore differentiation, as measured by expression of early (keratin 1) and intermediate (loricrin) markers (Fig. 1B). Exogenous re-expression of ΔNp63α in p63-depleted cells also significantly increased proliferation to levels observed in control cells transduced with ΔNp63α (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Re-expression of ΔNp63α rescues loss of differentiation and proliferation in p63-UTRi knockdowns. (A) Western blot analysis of HFKs transfected with siRNA targeting p63 UTR (UTRi) or scrambled control (Scr). The depleted cells were infected with adenovirus (MOI=50) expressing ΔNp63α with an HA tag (ΔNα) or GFP control virus 4 days post infection. (B) Sections of organotypic raft cultures generated from the same cells stained for H&E and indirect immunofluorescent staining for early [keratin 1 (K1)] and intermediate [loricrin (Lor)] markers of differentiation and p21. Scale bar: 100 μM. (C) Number of BrDU-incorporating cells assessed by immunofluorescent staining. The graph represents the average number of BrDU-positive cells in the basal epithelial layer from organotypic raft cultures cells per 1000 μM, expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (mean ± s.e. for at least 10 counts each of three independent biological replicates; P-value from paired t-test, *P<0.05, ***P<0.001).

p63 depletion results in aberrant p53-mediated activation of p21 expression

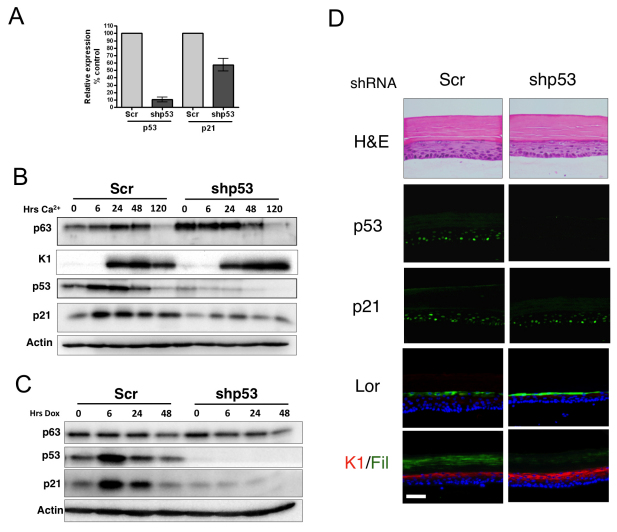

The ΔNp63α isoform has previously been shown to repress transcription of p21 by binding to two p53 response elements in the p21 promoter (Westfall et al., 2003). Therefore, the increase in p21 levels observed in p63-depleted cells probably represents aberrant de-repression of p53-mediated activation of the p21 promoter. We examined p21 levels in HFKs stably transduced with short hairpin RNA (shRNA) targeting p53. Although there was a greater than 90% reduction in mRNA levels of p53 in the cells, levels of expression of mRNA encoding p21, although reduced, were clearly not as significantly decreased as those of p53, indicating a p53-independent mechanism of expression (Fig. 2A). Furthermore, the transient induction observed during calcium-induced differentiation seems to be, in part, p53 independent, because p21 is still induced, albeit at lower levels (Fig. 2B). In striking contrast, p21 induction in response to DNA damage induced by adriamycin treatment is completely abrogated in p53-depleted cells (Fig. 2C). Furthermore, we detected p21 expression in organotypic raft cultures of p53 depleted by shRNA (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2.

p21 is transiently induced during differentiation in a p53-independent manner. (A) Quantitative PCR analysis of levels of mRNAs encoding p53 and p21 in HFKs depleted of p53 by shRNA. Each sample was analysed in triplicate and normalised to RPLPO as control, and expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (Scr) (mean ± s.e. of three independent biological replicates). (B) Western blot analysis of expression of p63, keratin 1 (K1), p21, p53 and actin loading control in HFKs expressing p53shRNA and scrambled control HFKs following calcium treatment to induce differentiation for the indicated times. (C) Western blot analysis of expression of p63, p21, p53 and actin loading control in HFKs expressing p53shRNA and scrambled control HFKs following adriamycin treatment to induce DNA damage for the indicated times. (D) Sections of organotypic raft cultures generated from HFKs expressing p53shRNA and scrambled control HFKs stained for H&E and indirect immunofluorescent staining for early (K1), intermediate (loricrin) and late (filaggrin) markers of differentiation, p21 and p53. Scale bar: 100 μM.

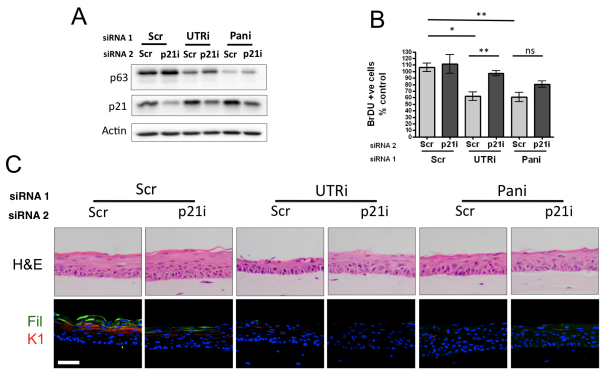

To determine whether the observed hypoproliferation in p63-depleted HFKs is p21 dependent, we simultaneously depleted HFKs with siRNAs targeting p63 (UTR or pan), p21 or scrambled control (Fig. 3A). Organotypic raft cultures revealed that p21 depletion resulted in partial rescue of proliferation in keratinocyte rafts depleted of the α and β p63 isoforms (UTR), whereas a smaller effect was observed in pan p63-depleted rafts that was not statistically significant (Fig. 3B). Similar to p53, p21 depletion did not restore expression of markers of differentiation or morphology (Fig. 3C). In contrast to p53 knockdown, p21 depletion alone resulted in decreased expression of markers of differentiation (Fig. 3C), as we have previously shown (Wong et al., 2010). Taken together, these data suggest that p21 induction is mediated by a p53-independent mechanism in HFKs in response to differentiation signals.

Fig. 3.

Hypoproliferation in p63-depleted HFKs is rescued by simultaneous depletion of p21. (A) Western blot analysis of expression of p63, p21, p53 and actin loading control in HFKs doubly transfected with p63-targeting siRNA (UTRi or Pani) and scrambled control (Scr) or p21-targeting siRNA (p21i). (B) Number of BrDU-incorporating cells in organotypic raft culture assessed by immunofluorescent staining. The graph represents the average number of BrDU-positive cells in the basal epithelial layer from organotypic raft cultures per 1000 μM, expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (mean ± s.e. for at least 10 counts each of three independent biological replicates; P-value for paired t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01; ns, not significant). (C) Sections of organotypic raft cultures generated from the same cells stained for H&E and indirect immunofluorescent staining for early (K1) and late filaggrin (Fil) markers of differentiation (scale bar=100 μM).

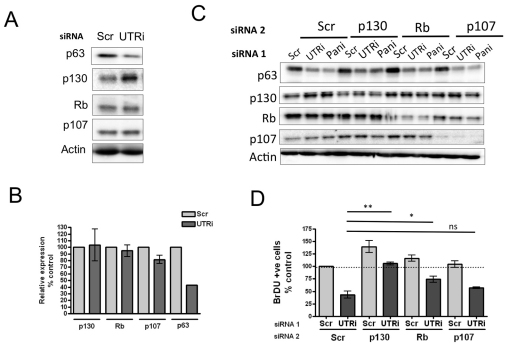

Hypoproliferation in p63-depleted cells is dependent on the Rb family member p130

Cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors such as p21 mediate their inhibitory effects on the cell cycle through the Rb family (DeGregori, 2004). We therefore examined levels of the Rb family members in p63-depleted cells and found that p63 depletion consistently resulted in increased p130 levels, whereas p107 and Rb levels were not consistently altered, as measured by western blot (Fig. 4A). Quantitative PCR analysis revealed that the increase in p130 levels was at the protein level, because mRNA levels of p130 are not significantly altered in p63-depleted cells (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

p130 is the major Rb family member required for hypoproliferation in p63-depleted HFKs. (A) Western blot analysis of p63, p130, Rb and p107 protein levels and actin loading control in HFKs depleted of α and β isoforms of p63 (UTRi). (B) Quantitative PCR analysis of levels of mRNA encoding p130, Rb, p107 and p63 in p63-depleted HFKs. Each sample was analysed in triplicate and normalised to RPLPO as control and expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (mean ± s.e. of three independent biological replicates). (C) Western blot analysis of p63, p130, Rb and p107 protein levels and actin loading control in HFKs simultaneously depleted for α and β isoforms of p63 (UTRi) or all isoforms of p63 (Pani) and individual Rb family members. (D) The number of BrDU-incorporating cells in HFKs simultaneously depleted for p63 and p130, Rb or p107, or scrambled control. The graph represents the percentage of BrDU-positive cells, expressed relative to scrambled control (mean ± s.e. of at least 500 cells, from three independent biological replicates; P-value for paired t-test, *P<0.05, **P<0.01; ns, not significant).

To determine whether p130, p107 or Rb family members are required for hypoproliferation in p63-depleted cells, we simultaneously depleted HFKs for p63 α and β isoforms using the UTR-targeting siRNA and individual Rb family members (Fig. 4C), and quantified the number of BrDU-incorporating cells in 2D culture (Fig. 4D). Depletion of p130 alone resulted in an increase in the number of BrDU-positive cells and rescued proliferation of p63-UTR-depleted cells to ~110% of the number of BrDU-positive cells observed in scrambled control (Fig. 4D). By contrast, p107 depletion did not significantly affect proliferation alone or in p63-depleted cells, whereas Rb knockdown results in a smaller increase in proliferation and partial rescue of proliferation to ~70% that of scrambled control. This is interesting, because recent data indicate that p130 is the major pocket protein accumulated downstream of p53 and p21 in replicative and DNA-damage-induced senescence (Helmbold et al., 2009), whereas Rb and p107 levels are consistently decreased. Therefore, because of the p130–p53–p21 association and because we only observed an increase in p130 protein levels in the p63-depleted cells and p130 depletion resulted in greater and more significant rescue of proliferation in p63-depleted cells, we examined the effect of p130 depletion in organotypic raft cultures. Depletion of p130 fully rescued hypoproliferation induced in rafts depleted of p63 by UTR siRNA (Fig. 5A,B). Similar to p53 and p21 depletion, p130 knockdown did not rescue expression of markers of differentiation (Fig. 5C). Taken together, these results indicate that p63 depletion results in cell cycle arrest dependent on p21 and Rb family members, in particular p130.

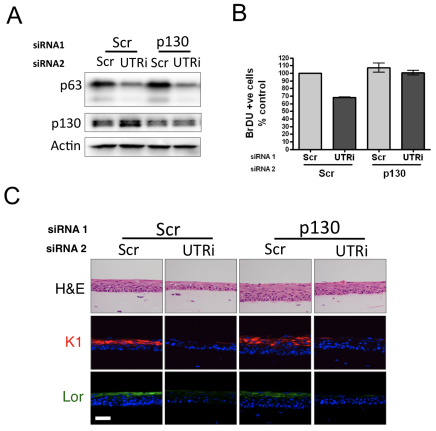

Fig. 5.

p130 accumulation in p63-depleted HFKs is required for hypoproliferation. (A) Western blot analysis of p63 and p130 levels and actin loading control in HFKs doubly transfected with UTRi and scrambled control or p130-targeting siRNA. (B) Number of BrDU-incorporating cells in organotypic raft cultures assessed by immunofluorescent staining. The graph represents the average number of BrDU-positive cells in the basal epithelial layer from organotypic raft cultures per 1000 μM, expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (mean ± s.e. for at least 10 counts each of three independent biological replicates). (C) Sections of organotypic raft cultures generated from the same cells stained for H&E and indirect immunofluorescent staining for early (K1) and intermediate (Lor) markers of differentiation. Scale bar: 100 μM.

SKP2 is a novel p63-regulated gene

Next, we looked for potential regulators of p130 stability and identified SKP2 as a potential p63-regulated gene, because it was recently shown to be regulated by p53 in response to DNA damage (Barre and Perkins, 2010). We wanted to determine whether Skp2 expression was positively regulated by p63, because Skp2 can target p130 and p21 for ubiquitylation and degradation as part of the SCFSkp2 complex (Bhattacharya et al., 2003; Yu et al., 1998). In addition, we also identified SKP2 as a potential p63 target gene in a p63 chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-seq experiment in HFKs (S. S. McD. and D. J. McC., unpublished). Furthermore, examination of an independent p63 genome tiling ChIP-chip approach in ME180 cervical carcinoma cells (Yang et al., 2006) and ChIP-seq in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (Kouwenhoven et al., 2010) revealed the same, but less finely mapped, predicted p63-binding site ~4 kb into intron 2 of the SKP2 gene (Fig. 6A).

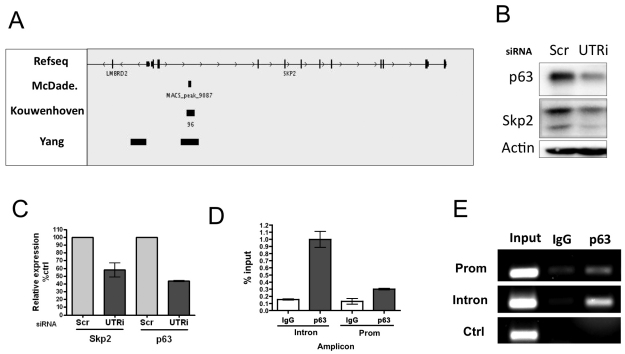

Fig. 6.

Skp2 expression is transcriptionally regulated by p63. (A) Schematic representation of the p63-binding region of Skp2 identified from ChIP-seq and ChIP-ChIP experiments (S. S. McD. and D. J. McC., unpublished) (Kouwenhoven et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2006). (B) Western blot analysis of p63 and Skp2 levels in HFKs depleted for p63 (UTRi). (C) Quantitative PCR analysis of mRNA levels of Skp2 and p63 in HFKs depleted by p63-UTRi siRNA. Each sample was analysed in triplicate, normalised to RPLPO as control and expressed as a percentage of the scrambled control (mean ± s.e. of three independent biological replicates). (D) Quantitative PCR analysis of DNA from ChIP of cycling HFKs treated with p63 antibody and matched IgG control. PCR with primers directed to p63-binding sites in Skp2 promoter (−1254 bp), intron 2 (+4 kb) and NFκB-binding site in proximal promoter (−243 bp) as negative control. Expressed as fold enrichment compared to IgG (mean ± s.e. of two independent biological replicates). (E) Agarose gel analysis of ChIP-PCR products.

To establish whether Skp2 is transcriptionally regulated by p63, we first examined Skp2 expression in p63-depleted HFKs and showed that expression is decreased at both protein and mRNA levels (Fig. 6B,C). To validate p63 binding to regulatory regions of the SKP2 gene, ChIP assays with a pan-p63 antibody and control IgG were carried out with chromatin isolated from cycling cells. Binding of p63 to the characterised p53-binding site in the SKP2 promoter (−1254) and to the intron 2 binding site identified in the ChIP-seq study (transcription start site +4 kb) of the SKP2 gene was quantified by real-time PCR (Fig. 6D). The primer sets used flank the p53-binding site in the SKP2 promoter (Barre and Perkins) and the p63-binding site in intron 2 identified by ChIP-Seq and a negative control region (an NFκB-binding site at −243 in the SKP2 promoter). An approximately sixfold enrichment (corresponds to 1% input) for the intron 2 p63-binding site compared with the control was observed (Fig. 6D). Binding of p63 to the p53-binding site in the SKP2 promoter (Prom) was also observed; however, enrichment was only 2–3 fold at this site in p63 ChIP compared with IgG control. Examination of an NFκB-binding site in the SKP2 promoter (−234) as a negative control indicated that there was no enrichment in p63 ChIP assays compared with IgG control assays. The specificity of these results was further confirmed by separating products of ChIP-PCR by agarose gel electrophoresis (Fig. 6E). Taken together, these data identify SKP2 as a novel p63 target gene.

Depletion of Skp2 in HFKs results in p130 accumulation

To determine whether modulation of Skp2 levels in HFKs leads to increased p130 levels, we depleted Skp2 with RNAi in HFKs and observed increased levels of p130 by western blot; in addition, we also observed a consistent but modest increase in p21 levels (Fig. 7A). This was concomitant with a 40% decrease in the number of BrDU-incorporating cells in 2D culture (Fig. 7B). To determine whether expression of exogenous Skp2 in p63-depleted cells rescued proliferation, we transiently transfected HFKs depleted for p63 with GFP alone or with Skp2 and 10% GFP (as a marker) and pulsed with BrDU. We then stained cells for BrDU and GFP, and counted the number of GFP-positive cells that were also positive for BrDU. The results indicate that expression of Skp2 in p63-depleted cells restores proliferation (Fig. 7C).

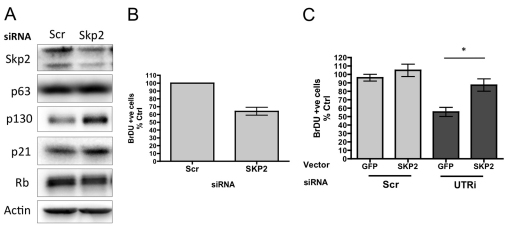

Fig. 7.

Skp2 depletion results in increased p130 levels. (A) Western blot analysis of p63, Skp2, p130, Rb, p21 and actin loading control in HFKs depleted by siRNA targeting Skp2. (B) The number of BrDU-incorporating cells in HFKs depleted for Skp2 or scrambled control. The graph represents the percentage of BrDU-positive cells, expressed relative to scrambled control (mean ± s.e. of at least 500 cells, from three independent biological replicates). (C) The number of BrDU-incorporating cells in HFKs depleted for Skp2 or scrambled control and transfected with GFP alone or Skp2 plus 10% GFP. The graph represents the percentage of BrDU-GFP-positive cells, expressed relative to scrambled control (mean ± s.e. of at least 250 cells, from three independent biological replicates; P-value for paired t-test, *P<0.05).

Discussion

The p63 transcription factor has been proposed as a master regulator of proliferation and differentiation of stratifying epithelia. Its role in maintaining proliferation and differentiation is somewhat controversial, because of subtle differences in phenotypes of different knockout mice (Mills et al., 1999; Yang et al., 1999). The complex nature of the TP63 gene and its clear role in development make it difficult to explore the functions of p63 in the mature epidermis of the knockout mouse. Using human organotypic raft cultures of normal human epidermal keratinocytes, it has recently been shown that depletion of p63 results in p53-dependent hypoproliferation, which can be fully rescued by p53 depletion; however, this is insufficient to restore differentiation (Truong et al., 2006).

Using organotypic raft cultures with neonatal HFKs, we demonstrate that RNAi-mediated depletion specifically of the α and β p63 isoforms results in loss of differentiation and hypoproliferation, indicating that these isoforms are required for both differentiation and maintenance of proliferative capacity. As described previously for depletion of all p63 isoforms (Truong et al., 2006), the hypoproliferation observed in α and β knockdowns could be fully rescued upon p53 depletion. Similar to depletion of all isoforms (Truong et al., 2006), in p63-UTR-depleted HFKs, we observed a p53-dependent increase in p21 levels.

When we depleted p21 levels in p63 knockdowns, we observed a partial rescue of proliferation in p63-depleted HFKs in four-day-old organotypic raft cultures This increase in proliferation was statistically significant in the raft depleted for the α and β isoforms, but not when all isoforms were depleted. Truong et al. (Truong et al., 2006) had previously reported that p21 depletion delayed hypoproliferation in p63-depleted cells, but in their model system of human epidermal keratinocytes this was insufficient to rescue proliferation in four-day-old rafts using an siRNA that targeted all p63 isoforms. The differences might be due to the different isoforms depleted (the γ isoforms remaining in the cells depleted of α and β) and the models utilised (neonatal foreskin keratinocytes versus adult epidermal keratinocytes). The neonatal model might contain a greater proportion of basal progenitors and p53-mediated activation of p21 has been shown to play a role dampening down proliferation in these cells (Gatza et al., 2007; Topley et al., 1999). Also, we show that, together with an increase in p21 levels, there is a change in the distribution of p21, from expression in just the basal cell to expression throughout the epithelial layers. This change in distribution was rescued by exogenous expression of ΔNp63α. Furthermore, we observed p21 induction in p53-depleted cells following calcium treatment to induce differentiation, in contrast to DNA damage in these p53-depleted HFKs, in which induction of p21 is completely abrogated. The results suggest that expression of the predominant ΔNp63α isoform is required for the regulation of p21 expression.

To determine the role of p21 in hypoproliferation in p63-depleted cells, we investigated downstream targets of p21. The Rb family members are important in regulating epidermal growth and differentiation. This is exemplified by the human papillomaviruses, which deregulate keratinocyte growth control through degradation of Rb, p107 and p130 mediated by the E7 protein (Ueno et al., 2006). We found that p130 is increased at the protein level in p63-depleted cells, suggesting stabilisation of the protein in the absence of p63. Importantly, the increase in p130 in these cells probably contributes to the hypoproliferative phenotype, because depletion of p130 leads to restoration of proliferation. It is interesting to note that depletion of Rb resulted in a smaller but significant increase in proliferation, indicating that it also plays a role in controlling proliferation. Furthermore, the Rb family member p130 has been shown recently to be the major pocket protein required for replicative and DNA-damage-induced senescence downstream of p53–p21 and p16INK4A (Helmbold et al., 2009). Taken together, this suggests that accumulation of p130 is one of the mechanisms underlying the hypoproliferation observed in HFKs acutely depleted for p63. In addition, p130 has been shown to be a possible effector of cell cycle arrest induced by transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) (Choi et al., 2002), which is an important regulator of epithelial cell cycle exit (Herzinger et al., 1995).

Because levels of the mRNA encoding p130 are unchanged in p63-depleted cells, it is clear that the protein stability is regulated post-transcriptionally. Interestingly, Skp2, which is the substrate recognition component of the SCFSkp2 E3 ubiquitin ligase complex (Skp2–Rbx1–Cul1–Skp1), which plays an important role in S-phase progression, has recently been shown to be cooperatively regulated by p53 and NFκβ in response to DNA damage (Barre and Perkins, 2010). Skp2 promotes S-phase progression by degrading negative cell cycle regulators, including p27, p21 and p130 among others, and can repress p53 activation by p300 (reviewed in Frescas and Pagano, 2008). Results from a p63 ChIP-seq experiment in HFKs (S. S. McD. and D. J. McC., unpublished), as well as a similar ChIP-seq experiment in normal human epidermal keratinocytes (NHEKs) and a genome tiling ChIP-chip experiment in ME180 cells, identified a common p63-binding site in intron 2 of the SKP2 gene (Kouwenhoven et al., 2010; Yang et al., 2006). Our results indicate that binding of p63 to the intron 2 binding site is responsible for promoting SKP2 transcription in keratinocytes. We also show that exogenous expression of Skp2 in p63-depleted cells is sufficient to rescue proliferation in p63-depleted HFKs. Taken together, we identify SKP2 as a novel pro-proliferative p63 target gene that probably exerts its function through targeted degradation of p130 and p21 to maintain cell proliferation (Bhattacharya et al., 2003; Yu et al., 1998). Supporting our findings, recent data indicate a positive role for p63 in maintaining expression of pro-proliferative cell cycle target genes and opposing p53-mediated repression (Lefkimmiatis et al., 2009).

Interestingly, Skp2 expression has recently been shown to be required for spontaneous tumorigenesis in Rb- (Lin et al., 2010) and PTEN-deficient mice (Wang et al., 2010), and is required for Ras-mediated transformation (Wang et al., 2010). Furthermore, inhibition of activation of the SCFSkp2 complex with a neddylation inhibitor was sufficient to suppress tumorigenesis (Wang et al., 2010). This is intriguing as several lines of evidence implicate p63 in preventing senescence (Guo et al., 2009; Keyes et al., 2006). Therefore, it will be important to determine the precise role played by p63 in regulating Skp2 expression, because increased expression of p63 and Skp2 is frequently observed in squamous cell carcinomas (Gstaiger et al., 2001; Sniezek et al., 2004).

Our data indicate that p63 plays a multifaceted role in the mature epidermis. It maintains proliferation by repressing p53-mediated activation of p21 and inhibition of p130, and by inducing expression of pro-proliferative genes such as SKP2. The identification of SKP2 as a p63 target gene is novel and particularly interesting, considering its recently identified essential role in several models of tumorigenesis and potential use as a therapeutic target (Bauzon and Zhu, 2010; Lin et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2010; Zhu, 2010).

Materials and Methods

Cell culture, infections and transfections

Isolation of primary neonatal HFKs and generation of shRNAs were carried out as previously described (Incassati et al., 2006). Differentiation of HFK cell lines in organotypic raft cultures was carried out as previously described (McCance et al., 1988). The raft cultures were harvested, fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), and then embedded in paraffin for subsequent sectioning and staining with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E). In order to label DNA-synthesizing cells, 20 μM BrDU was added to the raft culture 16 hours prior to harvest. Adenovirus expressing ΔNp63α including an HA tag was generated in the pADCMV destination adenovirus backbone, amplified, purified and titred on HEK293 cells according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). For adenoviral infection, cells were incubated with a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 50 for 6 hours in culture media. siRNA transfection of HFK cells was carried out with 200 nm siRNA using FuGENE HD transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. siRNAs were manually designed for p63 or Rb-family-targeting sequences were taken from pre-designed Ambion Silencer Select siRNAs, and are described in supplementary material Table S1. For calcium-induced differentiation, confluent monolayers of HFKs were induced to differentiate by withdrawal of growth factors and addition of 1.5 mM CaCl2.

Plasmids and constructs

pSuper-retro constructs expressing shRNAs against the 3′-UTR of p63 (p63-UTR), the p63 DNA-binding domain (p63-pan) and p53 (p53) were generated by legating annealed oligonucleotides (supplementary material Table S1) containing 21-mer targeting sequences into pSuper (Puro or Neo) according to manufacturers' instructions (Oligoengine); a scrambled control targeting no annotated gene was described previously (shSCRAM) (Incassati et al., 2006). All retroviral plasmid constructs were sequenced prior to transfection into ΦNYX-GP packaging cells. Adenovirus expressing ΔNp63α including an HA tag was produced by amplifying ΔNp63α with primers incorporating an HA tag at the C-terminus, cloned into pENT11 (Invitrogen) and recombined using LR Clonase into the pADCMV (Invitrogen) destination adenovirus backbone according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen).

Real-time reverse-transcriptase PCR analysis

RNA extraction was carried out with a High Pure RNA isolation kit (Roche), according to manufacturer instructions. RNA (1 μg) was treated with RQ1 RNase-Free DNase (Promega) prior to first strand cDNA synthesis using random primers with the Transcriptor High-Fidelity cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) according to manufacturer instructions. Amplification of PCR products was quantified using FastStart SYBR Green Master (Roche) according to manufacturer instruction and fluorescence monitored on a DNA Engine Peltier Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) equipped with a Chromo4 Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Melting curve analysis was also performed. In brief, cDNA samples were diluted 1:10 and quantified by amplification against serial dilutions of appropriate control cDNA with the following cycling conditions: initial denaturation 95°C for 10 minutes and 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 seconds, 58°C for 15 seconds, 60°C for 60 seconds. Specific primer sets were utilised for α, β and γ p63, p53 (Wang and Seed, 2003), p21Cip1 and RPLPO (large ribosomal protein) (Minner and Poumay, 2009) (for primer sequences, see supplementary material Table S2). Expression levels were assessed in triplicate, normalised to RPLPO levels and graphs represent the combined results of at least three independent biological replicates.

ChIP assays

Chromatin immunoprecipitations were carried out as described previously (Wong et al., 2010). An anti-pan-p63 monoclonal (clone 4A4; Santa Cruz) antibody or control mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG) were used for ChIP. The recovered DNA was subjected to PCR amplification using quantitative PCR as described above. For ChIP primer sequences, see supplementary material Table S2.

Western blot analysis

Protein lysate concentrations were 40 μg for western blots as previously described (Westbrook et al., 2002). Primary antibodies used are described in supplementary material Table S3. Secondary antibodies used in this study were goat anti-mouse and anti-rabbit HRP (Santa Cruz). Luminescence was revealed by incubation with either Western Lightning ECL (Perkin-Elmer) or West Femto substrate (Pierce), and signal detected on an Alpha Innotech FluorChem SP imaging system.

Immunofluorescent staining of organotypic raft sections

Tissue embedding and H&E staining were carried out as previously described (McKenna et al., 2010). Images were taken on an Olympus BH-2 microscope with an Olympus D25 camera using Cell B software (Olympus). 5 μm thick paraffin-embedded sections were deparaffinised with xylene, rehydrated with step-down concentrations of ethanol and submitted to antigen retrieval with boiling citrate buffer (DAKO). Indirect immunofluorescent staining was performed using the indicated primary antibodies and Alexa-Fluor-488-conjugated secondary reagents (Molecular Probes). Briefly, sections were permeabilised with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS) and 0.2% TRITON X-100 for 30 minutes at room temperature, rinsed and incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C in 10% FCS, washed and incubated with secondary goat anti-mouse or anti-rabbit antibodies conjugated to Alexa-Fluor-488 or Alexa-Fluor-594 (Molecular Probes) at room temperature for 1 hour, washed and mounted with Prolong Gold antifade reagent plus DAPI (Molecular Probes). Primary antibodies used are described in supplementary material Table S3. BrDU-pulsed cells on cover slips were fixed for 10 minutes with 4% PFA, washed three times with PBS, submitted to antigen retrieval and stained as described above. For raft sections, the number of BrDU-positive cells was counted for a minimum of 10 fields of view (1000 μM). For cover slips, a minimum of 10 fields of view and 500 cells were counted for each slide and expressed as the percentage of BrDU-positive cells (BrDU-DAPI). Graphs represent the mean of three independent biological replicates. In all cases, immunofluorescent images were captured on a Leica AF6000 inverted fluorescence microscope and Leica AF imaging software. Exposure times were kept constant within an experiment; images were pseudocoloured and processed identically in all cases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI030798) and the Medical Research Council (G0700754). We would like to thank Neil Perkins for siRNA targeting Skp2 and primer details. Deposited in PMC for release after 6 months.

Footnotes

Supplementary material available online at http://jcs.biologists.org/cgi/content/full/124/10/1635/DC1

References

- Barre B., Perkins N. D. (2010). The Skp2 promoter integrates signaling through the NF-kappaB, p53, and Akt/GSK3beta pathways to regulate autophagy and apoptosis. Mol. Cell 38, 524-538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauzon F., Zhu L. (2010). Racing to block tumorigenesis after pRb loss: an innocuous point mutation wins with synthetic lethality. Cell Cycle 9, 2118-2123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beretta C., Chiarelli A., Testoni B., Mantovani R., Guerrini L. (2005). Regulation of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p57Kip2 expression by p63. Cell Cycle 4, 1625-1631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya S., Garriga J., Calbo J., Yong T., Haines D. S., Grana X. (2003). SKP2 associates with p130 and accelerates p130 ubiquitylation and degradation in human cells. Oncogene 22, 2443-2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E., Terrinoni A., Rufini A., Chikh A., Lena A. M., Suzuki Y., Sayan B. S., Knight R. A., Melino G. (2006). p63 is upstream of IKK alpha in epidermal development. J. Cell Sci. 119, 4617-4622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candi E., Rufini A., Terrinoni A., Giamboi-Miraglia A., Lena A. M., Mantovani R., Knight R., Melino G. (2007). DeltaNp63 regulates thymic development through enhanced expression of FgfR2 and Jag2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104, 11999-12004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. H., Jong H. S., Hyun Song S., You Kim T., Kyeong Kim N., Bang Y. J. (2002). p130 mediates TGF-beta-induced cell-cycle arrest in Rb mutant HT-3 cells. Gynecol. Oncol. 86, 184-189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeGregori J. (2004). The Rb network. J. Cell Sci. 117, 3411-3413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deyoung M. P., Ellisen L. W. (2007). p63 and p73 in human cancer: defining the network. Oncogene 26, 5169-5183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donehower L. A., Harvey M., Slagle B. L., McArthur M. J., Montgomery C. A., Jr, Butel J. S., Bradley A. (1992). Mice deficient for p53 are developmentally normal but susceptible to spontaneous tumours. Nature 356, 215-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frescas D., Pagano M. (2008). Deregulated proteolysis by the F-box proteins SKP2 and beta-TrCP: tipping the scales of cancer. Nat. Rev. Cancer 8, 438-449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli F., Rossi M., D'Alessandra Y., De Simone M., Lopardo T., Haupt Y., Alsheich-Bartok O., Anzi S., Shaulian E., Calabro V., et al. (2010). MDM2 and Fbw7 cooperate to induce p63 protein degradation following DNA damage and cell differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 123, 2423-2433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatza C., Moore L., Dumble M., Donehower L. A. (2007). Tumor suppressor dosage regulates stem cell dynamics during aging. Cell Cycle 6, 52-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gstaiger M., Jordan R., Lim M., Catzavelos C., Mestan J., Slingerland J., Krek W. (2001). Skp2 is oncogenic and overexpressed in human cancers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 5043-5048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo X., Keyes W. M., Papazoglu C., Zuber J., Li W., Lowe S. W., Vogel H., Mills A. A. (2009). TAp63 induces senescence and suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1451-1457 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helmbold H., Komm N., Deppert W., Bohn W. (2009). Rb2/p130 is the dominating pocket protein in the p53-p21 DNA damage response pathway leading to senescence. Oncogene 28, 3456-3467 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herzinger T., Wolf D. A., Eick D., Kind P. (1995). The pRb-related protein p130 is a possible effector of transforming growth factor beta 1 induced cell cycle arrest in keratinocytes. Oncogene 10, 2079-2084 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihrie R. A., Marques M. R., Nguyen B. T., Horner J. S., Papazoglu C., Bronson R. T., Mills A. A., Attardi L. D. (2005). Perp is a p63-regulated gene essential for epithelial integrity. Cell 120, 843-856 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Incassati A., Patel D., McCance D. J. (2006). Induction of tetraploidy through loss of p53 and upregulation of Plk1 by human papillomavirus type-16 E6. Oncogene 25, 2444-2451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwin M. S., Kaelin W. G., Jr (2001). Role of the newer p53 family proteins in malignancy. Apoptosis 6, 17-29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes W. M., Vogel H., Koster M. I., Guo X., Qi Y., Petherbridge K. M., Roop D. R., Bradley A., Mills A. A. (2006). p63 heterozygous mutant mice are not prone to spontaneous or chemically induced tumors. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 8435-8440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouwenhoven E. N., van Heeringen S. J., Tena J. J., Oti M., Dutilh B. E., Alonso M. E., de la Calle-Mustienes E., Smeenk L., Rinne T., Parsaulian L., et al. (2010). Genome-wide profiling of p63 DNA-binding sites identifies an element that regulates gene expression during limb development in the 7q21 SHFM1 locus. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee H., Kimelman D. (2002). A dominant-negative form of p63 is required for epidermal proliferation in zebrafish. Dev. Cell 2, 607-616 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefkimmiatis K., Caratozzolo M. F., Merlo P., D'Erchia A. M., Navarro B., Levrero M., Sbisa E., Tullo A. (2009). p73 and p63 sustain cellular growth by transcriptional activation of cell cycle progression genes. Cancer Res. 69, 8563-8571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin H. K., Chen Z., Wang G., Nardella C., Lee S. W., Chan C. H., Yang W. L., Wang J., Egia A., Nakayama K. I., et al. (2010). Skp2 targeting suppresses tumorigenesis by Arf-p53-independent cellular senescence. Nature 464, 374-379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCance D. J., Kopan R., Fuchs E., Laimins L. A. (1988). Human papillomavirus type 16 alters human epithelial cell differentiation in vitro. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 7169-7173 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDade S. S., McCance D. J. (2010). The role of p63 in epidermal morphogenesis and neoplasia. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38, 223-228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna D. J., McDade S. S., Patel D., McCance D. J. (2010). MicroRNA 203 expression in keratinocytes is dependent on regulation of p53 levels by E6. J. Virol. 84, 10644-10652 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills A. A., Zheng B., Wang X. J., Vogel H., Roop D. R., Bradley A. (1999). p63 is a p53 homologue required for limb and epidermal morphogenesis. Nature 398, 708-713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minner F., Poumay Y. (2009). Candidate housekeeping genes require evaluation before their selection for studies of human epidermal keratinocytes. J. Invest. Dermatol. 129, 770-773 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missero C., Calautti E., Eckner R., Chin J., Tsai L. H., Livingston D. M., Dotto G. P. (1995). Involvement of the cell-cycle inhibitor Cip1/WAF1 and the E1A-associated p300 protein in terminal differentiation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 92, 5451-5455 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen B. C., Lefort K., Mandinova A., Antonini D., Devgan V., Della Gatta G., Koster M. I., Zhang Z., Wang J., Tommasi di Vignano A., et al. (2006). Cross-regulation between Notch and p63 in keratinocyte commitment to differentiation. Genes Dev. 20, 1028-1042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park B. J., Lee S. J., Kim J. I., Lee C. H., Chang S. G., Park J. H., Chi S. G. (2000). Frequent alteration of p63 expression in human primary bladder carcinomas. Cancer Res. 60, 3370-3374 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinne T., Brunner H. G., van Bokhoven H. (2007). p63-associated disorders. Cell Cycle 6, 262-268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi M., De Simone M., Pollice A., Santoro R., La Mantia G., Guerrini L., Calabro V. (2006). Itch/AIP4 associates with and promotes p63 protein degradation. Cell Cycle 5, 1816-1822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schavolt K. L., Pietenpol J. A. (2007). p53 and Delta Np63 alpha differentially bind and regulate target genes involved in cell cycle arrest, DNA repair and apoptosis. Oncogene 26, 6125-6132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sniezek J. C., Matheny K. E., Westfall M. D., Pietenpol J. A. (2004). Dominant negative p63 isoform expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Laryngoscope 114, 2063-2072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su X., Chakravarti D., Cho M. S., Liu L., Gi Y. J., Lin Y. L., Leung M. L., El-Naggar A., Creighton C. J., Suraokar M. B., et al. (2010). TAp63 suppresses metastasis through coordinate regulation of Dicer and miRNAs. Nature 467, 986-990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Topley G. I., Okuyama R., Gonzales J. G., Conti C., Dotto G. P. (1999). p21(WAF1/Cip1) functions as a suppressor of malignant skin tumor formation and a determinant of keratinocyte stem-cell potential. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96, 9089-9094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tron V. A., Trotter M. J., Tang L., Krajewska M., Reed J. C., Ho V. C., Li G. (1998). p53-regulated apoptosis is differentiation dependent in ultraviolet B-irradiated mouse keratinocytes. Am. J. Pathol. 153, 579-585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truong A. B., Kretz M., Ridky T. W., Kimmel R., Khavari P. A. (2006). p63 regulates proliferation and differentiation of developmentally mature keratinocytes. Genes Dev. 20, 3185-3197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ueno T., Sasaki K., Yoshida S., Kajitani N., Satsuka A., Nakamura H., Sakai H. (2006). Molecular mechanisms of hyperplasia induction by human papillomavirus E7. Oncogene 25, 4155-4164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., Bauzon F., Ji P., Xu X., Sun D., Locker J., Sellers R. S., Nakayama K., Nakayama K. I., Cobrinik D., et al. (2010). Skp2 is required for survival of aberrantly proliferating Rb1-deficient cells and for tumorigenesis in Rb1+/− mice. Nat. Genet. 42, 83-88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X., Seed B. (2003). A PCR primer bank for quantitative gene expression analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, e154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook T. F., Nguyen D. X., Thrash B. R., McCance D. J. (2002). E7 abolishes raf-induced arrest via mislocalization of p21(Cip1). Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 7041-7052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westfall M. D., Mays D. J., Sniezek J. C., Pietenpol J. A. (2003). The Delta Np63 alpha phosphoprotein binds the p21 and 14-3-3 sigma promoters in vivo and has transcriptional repressor activity that is reduced by Hay-Wells syndrome-derived mutations. Mol. Cell. Biol. 23, 2264-2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong P. P., Pickard A., McCance D. J. (2010). p300 alters keratinocyte cell growth and differentiation through regulation of p21(Waf1/CIP1). PLoS ONE 5, e8369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Kaghad M., Wang Y., Gillett E., Fleming M. D., Dotsch V., Andrews N. C., Caput D., McKeon F. (1998). p63, a p53 homolog at 3q27-29, encodes multiple products with transactivating, death-inducing, and dominant-negative activities. Mol. Cell 2, 305-316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Schweitzer R., Sun D., Kaghad M., Walker N., Bronson R. T., Tabin C., Sharpe A., Caput D., Crum C., et al. (1999). p63 is essential for regenerative proliferation in limb, craniofacial and epithelial development. Nature 398, 714-718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang A., Zhu Z., Kapranov P., McKeon F., Church G. M., Gingeras T. R., Struhl K. (2006). Relationships between p63 binding, DNA sequence, transcription activity, and biological function in human cells. Mol. Cell 24, 593-602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R., Poy M. N., Stoffel M., Fuchs E. (2008). A skin microRNA promotes differentiation by repressing ‘stemness’. Nature 452, 225-229 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Z. K., Gervais J. L., Zhang H. (1998). Human CUL-1 associates with the SKP1/SKP2 complex and regulates p21(CIP1/WAF1) and cyclin D proteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95, 11324-11329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu L. (2010). Skp2 knockout reduces cell proliferation and mouse body size: and prevents cancer? Cell Res. 20, 605-607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.