Abstract

Although dendritic cell (DC)- based cancer vaccines induce effective antitumor activities in murine models, only limited therapeutic results have been obtained in clinical trials. As cancer vaccines induce antitumor activities by eliciting or modifying immune responses in patients with cancer, the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and WHO criteria, designed to detect early effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy in solid tumors, may not provide a complete assessment of cancer vaccines. The problem may, in part, be resolved by carrying out immunologic cellular monitoring, which is one prerequisite for rational development of cancer vaccines. In this review, we will discuss immunologic monitoring of cellular responses for the evaluation of cancer vaccines including fusions of DC and whole tumor cell.

1. Introduction

The mechanism of action for most cancer vaccines is mainly mediated through cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs). We are now gaining a clear understanding of the cellular events leading to an effective CTL-mediated antitumor immunity. The antigen-presenting cells (APCs) most suitable for cancer vaccines are dendritic cells (DCs), which can be distinguished from B cells and macrophages by their abundant expression of costimulatory molecules and abilities to initiate a strong primary immune response [1, 2]. DCs are specialized to capture and process tumor-associated antigens (TAAs), converting the proteins to peptides that are presented on major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I and class II molecules [3]. After TAAs uptake and inflammatory stimulation, immature DCs in peripheral tissues undergo a maturation process characterized by the upregulation of costimulatory molecules [2, 3]. During this process, mature DCs migrate to T-cell areas of secondary lymphoid organs, where they present antigenic peptides to CD8+ and CD4+ T cells through MHC class I and class II pathways, respectively, and become competent to present antigens to T cells, thus initiating antigen-specific CTL responses [4]. Antigen-specific CTLs in turn can attack tumor cells that express cognate antigenic determinants or can provide help for B-cell responses that produce antibodies, which can also lead to tumor cell death in some cases [5]. Thus, the mechanism of action for cancer vaccines, based on harnessing host immune cells to infiltrate tumors and to exert CTL responses, is quite different from that of a traditional cytotoxic chemotherapy [6].

2. DC-Based Cancer Vaccines

A major area of investigation in induction of antitumor immunity involves the design of DC-based cancer vaccines [7]. DCs derive their potency from constitutive and inducible expression of essential costimulatory molecules including B7, ICAM-1, LFA-1, LFA-3, and CD40 on the cell surface [1, 8, 9]. These proteins function in concert to generate a network of secondary signals essential for reinforcing the primary antigen-specific signals in T-cell activation. Therefore, many strategies have been developed to load TAAs onto DCs and used as cancer vaccines. For example, DCs are pulsed with synthetic peptides derived from the known antigens [10], tumor lysates [11], tumor RNA [12, 13], and dying tumor cells [14] to induce antigen-specific antitumor immunity. Although the production of DC-based cancer vaccines for individual patients with cancer has currently been addressed in clinical trials, a major drawback of these strategies comes from the limited number of known antigenic peptides available in many HLA contexts. Moreover, the results of clinical trials using DCs pulsed with antigen-specific peptides show that clinical responses have been found in a small number of patients [15, 16]. To overcome this limitation, we have proposed the fusions of DCs and whole tumor cell (DC/tumor) to generate cell hybrids with the characteristics of APCs able to process endogenously provided whole TAAs [17]. The whole tumor cells may be postulated to serve as the best source of antigens [17–21].

3. DC/Tumor Fusion Vaccines

The fusion of DC and tumor cell through chemical [17], physical [22], or biological means [23] creates a heterokaryon which combines DC-derived costimulatory molecules, efficient antigen-processing and -presentation machinery, and an abundance of tumor-derived antigens including those yet to be unidentified (Figure 1). Thus, the DC/tumor fusion cells combine the essential elements for presenting tumor antigens to host immune cells and for inducing effective antitumor responses. Now, it is becoming clear that the tumor antigens are processed along the endogenous pathway, through the antigen processing machinery of human DC. Thus, it is conceivable that tumor antigens synthesized de novo in the heterokaryon are processed and presented through the endogenous pathway. The advantage of DC/tumor fusion vaccines over pulsing DC with whole tumor lysates is that endogenously synthesized antigens have better access to MHC class I pathway [18–21]. Indeed, it has been demonstrated that DC/tumor fusion vaccines are superior to those involving other methods of DC loaded with antigenic proteins, peptides, tumor cell lysates, or irradiated tumor cells in murine models [18–21]. The efficacy of antitumor immunity induced by DC/tumor fusion vaccines has been demonstrated in murine models using melanoma [24–32], colorectal [17, 30, 31, 33–41], breast [42–47], esophageal [48], pancreatic [49, 50], hepatocellular [51–55], lung [22, 41, 56–59], renal cell [60] carcinoma, sarcoma [61–66], myeloma [67–74], mastocytoma [75], lymphoma [76], and neuroblastoma [77]. The fusion cells generated with human DC and tumor cell also have the ability to present multiple tumor antigens, thus increasing the frequency of responding T cells and maximizing antitumor immunity capable of killing tumor targets such as colon [78–84], gastric [85, 86], pancreatic [87], breast [47, 88–93], laryngeal [94], ovarian [95–97], lung [85, 98], prostate [99, 100], renal cell [101, 102], hepatocellular [103–105] carcinoma, leukemia [106–111], myeloma [112, 113], sarcoma [114, 115], melanoma [116–119], glioma [120], and plasmacytoma [121].

Figure 1.

A model of antigen processing and presentation by DC/tumor fusion cell. DC/tumor fusion cell expresses MHC class I, class II, costimulatory molecules, and tumor-associated antigens. Tumor-associated antigens can be processed and presented through the antigen processing and presentation pathway of DC.

4. Monitoring of DC/Tumor Fusion Cell Preparations

Despite the strong preclinical evidences supporting the use of DC/tumor fusions for cancer vaccination, the results of clinical trials so far reported are conflicting [18–21]. One of the reasons is the evidence for fusion cell formation used as clinical trials is not definitive [23]. The levels of fusion efficiency, which can be quantified by determining the percentage of cells that coexpress tumor and DC antigens, are closely correlated with CTL induction in vitro [82, 83]. Another reason is immunosuppressive substances such as TGF-β derived from tumor cells used for fusion cell preparations [35, 47]. Although tumor-derived TGF-β reduces the efficacy of DC/tumor fusion vaccines via an in vivo mechanism [35], the reduction of TGF-β derived from the fusions inhibits the generation of Tregs and enhances antitumor immunity [47]. Moreover, the therapeutic effects in patients vaccinated by DC/tumor fusions are correlated with the characteristics of the DCs used as the fusion vaccines [82, 83]. Indeed, patient-derived fusions show inferior levels of MHC class II and costimulatory molecules and produce decreased levels of IL-12 and increased levels of IL-10, as compared with those obtained from fusions of tumor cell and DC from healthy donors [87, 103]. However, the fusion vaccines induce recovery of DC function in metastatic cancer patients [103]. Therefore, it is important to assess the phenotype and function of DC/tumor fusion cell preparations used in each vaccination.

5. In Vivo Monitoring

The delayed-type hypersensitivity (DTH) is an inflammatory reaction mainly mediated by CD4+ effector memory T cells that infiltrate the site of injection of an antigen against which the immune system has been primed by cancer vaccines [122]. Actually, soluble proteins, peptides, or antigens pulsed DCs have been injected intradermally, and the diameter of erythema or induration after 48–72 h is measured. CD4+ effector memory T cells that recognize the antigens presented on local APCs mediate the immune responses by releasing cytokines, resulting in an increased vascular permeability and the recruitment of monocytes and other inflammatory cells in the site. CD8+ T cells less frequently also mediate similar responses [123]. It has been reported that antigen-specific T cells can be readily detected in skin biopsies from DTH sites, much less in abdominal lymph nodes, and not in peripheral blood and tumor site [124]. Moreover, there is a significant correlation between favorable clinical outcome and the presence of vaccine-related antigen-specific T cells in biopsies from DTH sites [122]. Indeed, the increased DTH reactivity against tumor antigens has been observed in clinical responders by DC/tumor fusion vaccines [125]. In almost patients with cancer, T cells from lymph nodes and the tumor site itself are not readily available for monitoring purposes. Therefore, functional assessment of antigen-specific T cells from such DTH sites may serve as an additional strategy to evaluate antigen-specific antitumor immune responses [122, 126, 127].

6. T-Cell Monitoring In Vitro

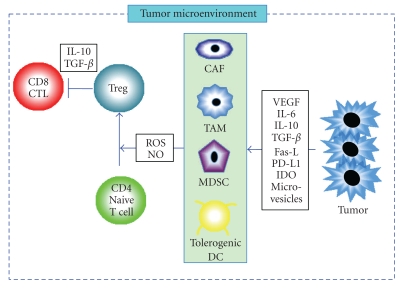

The mechanism of cancer vaccines, based on inducing CTLs, infiltrating tumors, and exerting T-cell-mediated cytotoxic effects, is quite different from that of cytotoxic chemotherapy. As cancer vaccines do not work as quickly as chemotherapy which has a direct cytotoxic effect, the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) and WHO criteria [128, 129], designed to detect early effects of cytotoxic chemotherapy, cannot appropriately evaluate the response patterns observed with cancer vaccines. The RECIST criteria are highly dependent upon measurement of tumor size. They presume that linear measures are an adequate substitute for 2-dimentional methods and register four response categories: CR (complete response), PR (partial response), SD (stable disease), and PD (progressive disease). However, in the solid tumors, there exist not only antigen-specific CTLs but also immune suppressive cells such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) [130], immunosuppressive tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) [131], and cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) [132] (Figure 2). After vaccination, the solid tumors may become heavily infiltrated by immune-related cells resulting in an apparent increase in size of lesions, which is, at least in part, due to the infiltration of CTLs induced by cancer vaccines. Therefore, the development of new response criteria, including immunologic cellular monitoring, is of great importance in the development of cancer vaccines.

Figure 2.

Immune suppressive responses at the tumor microenvironment. Tumor cells secrete various factors such as VEGF, IL-6, IL-10, TGF-β, Fas-L, IDO, PD-L1, and microvesicles, all of which promote the accumulation of heterogeneous populations of tumor-associated macrophage (TAM), myeloid-derived suppressor cell (MDSC), or tolerogenic DC. These immunosuppressive cells inhibit antitumor immunity by various mechanisms, including elaboration of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and nitrogen oxide (NO). The tumor microenvironment also promote the accumulation of regulatory T cell (Treg) that suppresses CD8+ CTL function through secretion of IL-10 or TGF-β from Tregs and tumor cells.

In clinical trials, the peripheral blood T-cell responses are generally accessible for serial analyses. The currently used methods of assessing T-cells from patients treated with cancer vaccines are T-cell proliferation, cytokine profile, cytotoxic T lymphocyte assays (CTL assays), CTL-associated molecules (CD107, perforin, granzyme B, and CD154), multimer analysis, T-cell receptor (TCR) gene usage, and immune suppression assays (Table 1). While these assays can be also used for monitoring cellular immune responses induced by DC/tumor fusion vaccines, none has been standardized. As DC/tumor fusion vaccines can induce defined and undefined antigen-specific antitumor activities, immunologic cellular monitoring for the fusion vaccines is much more complex. Furthermore, as immune responses induced by DC/tumor fusion vaccines are a balanced mosaic of both immune stimulatory and suppressive responses [92], multiple monitoring assays for the clinical efficacy parameters may be needed to evaluate the antitumor immune responses.

Table 1.

Immunologic monitoring.

| Inflammatory skin reaction | DTH |

|---|---|

| T-cell proliferation | [3H] thymidine uptake |

| CFSE dilution | |

| Cytokine profile | ELISPOT assay |

| Secretion of cytokines | |

| Intracellular cytokines | |

| CTL assays | 51Cr-release assays |

| Flow cytometry-based cytotoxicity assays (Caspase-3, Anexin-V) | |

| CTL-associated molecules | Perforin |

| Granzyme B | |

| CD107a and b expression in CD8+ T cells | |

| CD154 expression in CD4+ T cells | |

| T cell phenotype | Multimer analysis |

| TCR analysis | |

| Immune suppression assays | CD25, FOXP3, IL-10, TGF-beta |

| DTH; delayed type hypersensitivity | |

| CFSE; 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester | |

| TCR; T-cell receptor | |

6.1. T-Cell Proliferation

T-cell proliferation assay assesses the number and function at the level of the entire T-cell population in the culture. Therefore, the ability to detect T-cell responses is based on the proliferative potential of the cells in response to antigens. The most commonly used in vitro method for measuring antigen-specific T-cell proliferation is the assessment of T-cell clonal expansion following incubation of T-cells with antigens in the presence of a radio-labeled nucleotide (e.g., [3H] thymidine) in vitro. CFSE (5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester) staining can be also used to directly detect proliferative responses of T-cells [82]. Because CFSE is partitioned equally during cell division [133], this technique can monitor T-cell division and determine the relationship between T-cell division and differentiation in vitro and in vivo. The extensive T-cell proliferation can be demonstrated by the few undivided T-cells left and from proper accumulation of activated T cells, as shown by the increase in T-cell counts correlating with the decrease in CFSE label for each division. The CFSE-based assays are equivalent to traditional measures of antigen-specific T-cell responsiveness and have significant advantages for the ability to gate on a specific population of T-cells and the concomitant measurement of T-cell phenotype [134]. After vaccination, DC/tumor fusion cells can migrate to the T-cell area in the regional lymph nodes and form clusters with CD8+ and CD4+ T cells [34]. Simultaneous recognition of cognate peptides presented by MHC class I and class II molecules on DC/tumor fusion cell is essential in the induction of efficient CTLs. Therefore, measuring antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell proliferation is essential to evaluate the induction of vaccine-specific immune responses. Although T-cell proliferation assay is usefulness to detect immune responses in vitro, the results are strongly influenced by the in vitro stimulation procedures. Stimulation of naive T cells from healthy donors with DC/tumor fusions in vitro results in potent proliferation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [34, 80]. Therefore, to assess DC/tumor fusion vaccines, antigen-specific CD4+ and CD8+ T cells need to be expanded by stimulation with autologous tumor lysates [103]. In addition, the frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) obtained before and after vaccination must be processed in the same set of experiments [103, 135, 136]. As T-cell proliferation assay is biologically irrelevant and imprecise for the reasons stated above, this assay may not be emphasized in future studies.

6.2. Cytokine Production

There is a currently great interest in the assay of polyfunctional T cells, secreting multiple cytokines (e.g., secreting IFN-γ and TNF-α rather than either alone), or expressing multiple surface markers. As the release of Th1 cytokines such as IFN-γ and TNF-α is important to determine long-lasting antitumor immunity, a shift to Th1 response by cancer vaccines is essential for therapeutic potential in murine models [36, 37, 67, 77, 137, 138]. Therefore, it is important to test whether cancer vaccines can induce a Th1 response in the tumor-specific T cells, and what impact might this have on the clinical responses. Cytokine production by T cells in response to antigens can be detected in individual T cells by enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) assay [18–21, 139]. Moreover, production of IFN-γ captured by antibodies bound to T-cell surface can be detected by flow cytometry analysis [96, 140]. The actual state of antigen specific T-cell reactivity directly from peripheral blood T cells can be quantified by IFN-γ ELISPOT assay and flow cytometry analysis [18–21, 141]. As the IFN-γ ELISPOT assay shows highly reproducible results among different laboratories, the ELISPOT may be an ideal candidate for robust monitoring of T-cell activity [18–21, 142]. Coculture of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells from healthy donors with DC/tumor fusions results in high levels of IFN-γ production and low levels of IL-10 production [50, 54, 80, 143]. Therefore, to assess DC/tumor fusion vaccines precisely, T cells obtained before and after vaccination might be directly quantified with stimulation of autologous tumor lysates in vitro [103]. In effective clinical responders, comparable levels of IFN-γ production in response to tumor lysates may be detected in PBMCs obtained before vaccination. A correlation between IFN-γ ELISPOT outcome and effective clinical responses (period free of relapse or survival) has been found in patients treated with cancer vaccines including DC/tumor fusions [103, 135, 136, 144].

6.3. CTL Assays

For immune monitoring of cancer vaccines, T-cell-mediated CTL assays are appealing because measurement of the ability of CTL to kill tumor targets is thought to be a relevant marker for antitumor activity. It has been assumed that the cytotoxicity has been measured in 51Cr-release assays in vitro. One drawback to the CTL assays is their relative insensitivity. Instead of 51Cr release assays, flow cytometry-based methods have been developed to assess CTL activity [145, 146]. Flow cytometry CTL assays can be predicated on measurement of CTL-induced caspase-3 or annexin-V activation in target cells through fluorescence detection, which are more sensitive to conventional 51Cr release assays [145–147]. These assays show increased sensitivity at early time points after target/effector cell mixing and allow for analysis of target cells in real time at the single-cell level. However, it is unusual to detect antigen-specific killing by T cells directly isolated from the patients vaccinated with DC/tumor fusions even with the use of flow cytometry-based CTL assays [103, 148]. Therefore, there is a need to stimulate and expand the antigen-specific T cells in vitro for several days. These stimulations may distort the phenotype and function of the T-cell populations from tumor state. Moreover, it is difficult to obtain sufficient numbers of viable tumor cells from primary lesion due to the length of culture time and potential contamination of bacteria and fungus [79]. Thus, semiallogeneic targets with shared TAAs and MHC class I molecules are necessary instead of autologous targets. Importantly, a majority of the antigen-specific CD8+ CTLs in peripheral blood may not be tumor reactive due to various mechanisms such as downmodulation of MHC class I molecules on tumors and presence of Tregs at the tumor site. Indeed, cytotoxic activity against autologous targets has been observed in peripheral blood T cells from patients vaccinated with DC/tumor fusions by CTL assays [103, 148], but the clinical responses from early clinical trails in patients with melanoma, glioma, gastric, breast, and renal cancer are muted [103, 130, 134, 135, 142, 143, 148–154]. The defects of the clinical responses may be caused by the immunosuppressive influences derived from the local tumor microenvironment [103]. In addition, therapeutic antitumor immunity depends on highly migratory CTLs capable of trafficking between lymphoid and tumor sites [155]. Therefore, localization of antigen-specific CTLs demonstrated by analysis of biopsy samples from tumor sites may be directly associated with clinical responses [155].

6.4. Tumor-Specific CD8+ and CD4+ T Cells

The population of CD8+ CTLs can destroy tumor cells through effector molecules (e.g., perforin and granzyme B) [156]. Degranulation of CD107a and b is a requisite process of perforin/granzyme B-dependent lytic fashions mediated by responding antigen-specific CTLs. These perforin/granzyme B-dependent lytic fashions require degranulation of CD107a and b in CD8+ CTLs [5]. Therefore, measurement of CD107a and b, perforin, or granzyme B expression by flow cytometric analysis can be combined with intracellular IFN-γ staining to more completely assess the functionality of CD8+ CTLs [83, 87]. Moreover, autologous tumor-induced de novo CD154 expression in CD4+ T cells is highly sensitive for tumor-specific Th cells [157]. The coupling of CD154 expression with multiplexed measurements of IFN-γ production provides a greater level of detail for the study of tumor-specific CD4+ T-cell responses. Although DC/tumor fusion vaccines have abilities to induce CD107+ IFN-γ+ CD8+ T cells and CD154+ IFN-γ+ CD4+ T cells upon autologous tumor encounter in vitro [83, 87], it has now been unclear the correlation of the assay with clinical outcome.

6.5. Multimer Assays

Now, it has become possible to analyze antigen-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells by flow cytometric analysis using multimeric MHC-peptide complexes, measuring the affinity of the TCR to a given epitope [158]. The MHC-peptide multimer analysis is more sensitive to conventional CTL assays [158]. Although DC/tumor fusion vaccines can induce defined and undefined antigens-specific CD8+ and CD4+ T cells, the multimer analysis can only be used to detect immune responses against defined antigenic epitopes expressing in tumor cells [21]. MHC-peptide multimers stably bind to the TCR exhibiting a certain minimal avidity. Hence, there are principal limitations of the multimeric analysis including the suitability and specificity of multimers and the lack of information about the functionality of multimer-positive T cells [158]. The specific role of the multimer-positive T cells for cancer vaccine efficacy has not yet been well established in the setting of clinical trials. Recent studies suggest that effective cancer vaccines not only stimulate CTL activity, but also sustain long-term memory T cells capable of mounting strong proliferative and functional responses to secondary tumor antigen challenge [159]. Therefore, it is more important to assess whether multimer-positive T cells are effector or effector-memory cells. Moreover, the combined use of multimers and functional assays such as IFN-γ analysis may have provided some insight into the functional activity of these cells. It has been demonstrated that cryopreserved PBMCs from melanoma patients vaccinated with gp100 peptide show that the majority of multimer-positive CD8+ T cells had either a long-term “effector” (CD45RA+ CCR7−) or an “effector-memory” (CD45RA− CCR7−) phenotype [160]. Interestingly, after vaccination, the resected melanoma patients can mount a significant antigen-specific CD8+ T cell immune response with a production of IFN-γ and high proliferation potential [160]. To date, no studies have evaluated the functional activity of multimer-positive T cells in the blood after vaccination with DC/tumor fusions.

6.6. TCR

Only T cells having a TCR specific for a given antigen are triggered by interaction with cancer vaccines. This activation results in the clonal expansion of antigen-specific T cells that can be followed by TCR Vβ gene usage. Recently, the availability of a large panel of monoclonal antibodies against TCRs, mainly Vβ epitopes, allows one to study the TCR repertoire by flow cytometry [161]. PCR techniques can also be used to detect a restricted TCR repertoire from small amounts of T cells without biases caused by ex vivo expansions [162]. Although DC/tumor fusion vaccines have resulted in selection and expansion of T-cell clones [87], the generation of antitumor immunity by CTLs has not correlated with clinical responses. Tumors may evade surveillance of CTLs by distinct mechanisms. Immunogenic tolerance to a particular set of antigens is the absence of an immune response to those antigens, which can be achieved by processes that result in T-cell anergy (antigen-specific unresponsiveness), T-cell unresponsiveness (generalized dysfunction), and T-cell deletion (apoptosis) [163]. Future fusion vaccine studies should be designed to determine whether T-cell dysfunction correlated with clinical outcome.

6.7. Immune Suppression Assays

Although antigen-specific CTLs can be generated and detected in the circulation of vaccinated patients, these do not usually act against the tumor. It has been documented that immune suppressive cells can counteract antitumor immune responses. In tumor microenvironment, there are not only CTLs but also many immune suppressive cells such as CD4+ CD25high+ Foxp3+ Tregs [103, 164], MDSCs [130], TAMs [131], and CAFs [132] (Figure 2). Moreover, tumor cells produce immunosuppressive substances such as transforming growth factor β (TGF-β) [165] vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) [166], IL-6 [167], IL-10 [167], soluble Fas ligand (Fas-L) [168], programmed death-1 ligand (PD-L1) [169], indolamine-2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) [170], and microvesicles [171]. Type 1 regulatory T cells (Tr1) expressing CD39 may mediate suppression by IL-10, TGF-β, and adenosine secretion, and whereby accumulation strongly correlates with the cancer progression [172]. The mechanisms that suppress the immune system provide a fundamental reason why cancer vaccines fail to induce consistently robust antitumor immune responses. In DC/tumor fusion vaccines, CD4+ CD25high+ Foxp3+ Tregs were promoted in the presence of the local tumor-related factors in vitro [103]. Moreover, increased CD4+ CD25high+ Foxp3+ Tregs impaired the effector function of CTLs induced by DC/tumor fusion vaccines [103]. Therefore, monitoring of immune suppressive cells in cancer patients vaccinated with DC/tumor fusions is also essential.

7. Conclusion

The development of assays for detecting immune responses associated with clinical outcome has been limited. A variety of assays had been introduced to provide monitoring tools necessary for following changes in the frequency of antigen-specific CTLs and to assess the impact of cancer vaccines on the immune system. As the mechanisms of immune response that cause tumor regression are not simple, the currently available assays may not actually measure a function with direct relevance to how tumors are actually attacked immunologically in cancer patients. A high reproducibility of results among different laboratories leads to the conclusion that cytokine flow cytometry or ELISPOT may be an ideal candidate for robust and reproducible monitoring of T-cell activity in vivo. However, the widely used ELISPOT assay often does not correlate the best with clinical outcome [173]. Therefore, it may be important to use a functional assay like cytokine flow cytometry or ELISPOT in combination with a quantitative assay like multimers for immune monitoring. Furthermore, it is necessary to understand the immune responses seen in peripheral blood versus the responses at the tumor site. Monitoring of antigen-specific CTLs at the tumor site may be directly associated with clinical responses [155]. However, T cells from lymph nodes and the tumor site itself are not readily available for monitoring purposes in almost all patients. Therefore, the ability to assess the function of antigen-specific T cells from DTH site may serve as an additional strategy to evaluate cancer vaccines [122, 126, 127]. In our opinion, monitoring of multimer-positive CD8+ (effector or effector memory) T cells from the DTH sites or PBMCs with IFN-γ production by flow cytometry may be sensitive markers particularly associated with overall survival. In addition, the DC/tumor fusion vaccine studies should be designed to determine whether T cell dysfunction in the tumor microenvironment correlated with clinical outcome. This informations may help us more fully understand the mechanisms of cancer vaccines and its potency to hasten the progress of efficient cancer vaccine strategies into the clinic.

Disclosure

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the paper.

Acknowledgments

This work has been supported by Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation, Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) from the Ministry of Education, Cultures, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan, Grant-in-Aid of the Japan Medical Association, Takeda Science Foundation, Pancreas Research Foundation of Japan, and Mitsui Life Social Welfare Foundation.

References

- 1.Inaba K, Pack M, Inaba M, Sakuta H, Isdell F, Steinman RM. High levels of a major histocompatibility complex II-self peptide complex on dendritic cells from the T cell areas of lymph nodes. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1997;186(5):665–672. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.5.665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banchereau J, Steinman RM. Dendritic cells and the control of immunity. Nature. 1998;392(6673):245–252. doi: 10.1038/32588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Steinman RM, Swanson J. The endocytic activity of dendritic cells. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1995;182(2):283–288. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.2.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steinman RM. The dendritic cell system and its role in immunogenicity. Annual Review of Immunology. 1991;9:271–296. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.001415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry M, Bleackley RC. Cytotoxic T lymphocytes: all roads lead to death. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2002;2(6):401–409. doi: 10.1038/nri819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wolchok JD, Hoos A, O’Day S, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation of immune therapy activity in solid tumors: immune-related response criteria. Clinical Cancer Research. 2009;15(23):7412–7420. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Banchereau J, Palucka AK. Dendritic cells as therapeutic vaccines against cancer. Nature Reviews Immunology. 2005;5(4):296–306. doi: 10.1038/nri1592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inaba K, Witmer-Pack M, Inaba M, et al. The tissue distribution of the B7-2 costimulator in mice: abundant expression on dendritic cells in situ and during maturation in vitro. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;180(5):1849–1860. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.5.1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Young JW, Inaba K. Dendritic cells as adjuvants for class I major histocompatibility complex-restricted antitumor immunity. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;183(1):7–11. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Celluzzi CM, Mayordomo JI, Storkus WJ, Lotze MT, Falo LD., Jr. Peptide-pulsed dendritic cells induce antigen-specific, CTL-mediated protective tumor immunity. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1996;183(1):283–287. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.1.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nestle FO, Alijagic S, Gilliet M, et al. Vaccination of melanoma patients with peptide- or tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells. Nature Medicine. 1998;4(3):328–332. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nair SK, Hull S, Coleman D, Gilboa E, Lyerly HK, Morse MA. Induction of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)-specific cytotoxic T-lymphocyte responses in vitro using autologous dendritic cells loaded with CEA peptide or CEA RNA in patients with metastatic malignancies expressing CEA. International Journal of Cancer. 1999;82(1):121–124. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19990702)82:1<121::aid-ijc20>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koido S, Kashiwaba M, Chen D, Gendler S, Kufe D, Gong J. Induction of antitumor immunity by vaccination of dendritic cells transfected with MUC1 RNA. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(10):5713–5719. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.10.5713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Palucka AK, Ueno H, Connolly J, et al. Dendritic cells loaded with killed allogeneic melanoma cells can induce objective clinical responses and MART-1 specific CD8+ T-cell immunity. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2006;29(5):545–557. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000211309.90621.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thurner B, Haendle I, Röder C, et al. Vaccination with Mage-3A1 peptide-pulsed nature, monocyte-derived dendritic cells expands specific cytotoxic T cells and induces regression of some metastases in advanced stage IV melanoma. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1999;190(11):1669–1678. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.11.1669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackensen A, Herbst B, Jr., Chen JIL, et al. Phase I study in melanoma patients of a vaccine with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells generated in vitro from CD34+ hematopoietic progenitor cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;89(2):385–392. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000501)86:3<385::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gong J, Chen D, Kashiwaba M, Kufe D. Induction of antitumor activity by immunization with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Nature Medicine. 1997;3(5):558–561. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, Fujise K, Gong J, Tajiri H. Dendritic/tumor fusion cell-based vaccination against cancer. Archivum Immunologiae et Therapiae Experimentalis. 2007;55(5):281–287. doi: 10.1007/s00005-007-0034-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gong J, Koido S, Calderwood SK. Cell fusion: from hybridoma to dendritic cell-based vaccine. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2008;7(7):1055–1068. doi: 10.1586/14760584.7.7.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, et al. Cancer vaccine by fusions of dendritic and cancer cells. Clinical and Developmental Immunology. 2009;2009:13 pages. doi: 10.1155/2009/657369. Article ID 657369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Koido S, Homma S, Hara E, et al. Antigen-specific polyclonal cytotoxic T lymphocytes induced by fusions of dendritic cells and tumor cells. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2010;2010:12 pages. doi: 10.1155/2010/752381. Article ID 752381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Celluzzi CM, Falo LD., Jr. Physical interaction between dendritic cells and tumor cells results in an immunogen that induces protective and therapeutic tumor rejection. The Journal of Immunology. 1998;160(7):3081–3085. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shu S, Zheng R, Lee WT, Cohen PA. Immunogenicity of dendritic-tumor fusion hybrids and their utility in cancer immunotherapy. Critical Reviews in Immunology. 2007;27(5):463–483. doi: 10.1615/critrevimmunol.v27.i5.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Saffold S, Cao X, Krauss J, Chen W. Eliciting T cell immunity against poorly immunogenic tumors by immunization with dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccines. The Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(10):5516–5524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cao X, Zhang W, Wang J, et al. Therapy of established tumour with a hybrid cellular vaccine generated by using granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor genetically modified dendritic cells. Immunology. 1999;97(4):616–625. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li J, Holmes LM, Franek KJ, Burgin KE, Wagner TE, Wei Y. Purified hybrid cells from dendritic cell and tumor cell fusions are superior activators of antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2001;50(9):456–462. doi: 10.1007/s002620100218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Phan V, Errington F, Cheong SC, et al. A new genetic method to generate and isolate small, short-lived but highly potent dendritic cell-tumor cell hybrid vaccines. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(9):1215–1219. doi: 10.1038/nm923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu K, Kuriyama H, Kjaergaard J, Lee W, Tanaka H, Shu S. Comparative analysis of antigen loading strategies of dendritic cells for tumor immunotherapy. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2004;27(4):265–272. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200407000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuriyama H, Watanabe S, Kjaergaard J, et al. Mechanism of third signals provided by IL-12 and OX-40R ligation in eliciting therapeutic immunity following dendritic-tumor fusion vaccination. Cellular Immunology. 2006;243(1):30–40. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2006.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ishida A, Tanaka H, Hiura T, et al. Generation of anti-tumour effector T cells from naïve T cells by stimulation with dendritic/tumour fusion cells. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2007;66(5):546–554. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2007.02012.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ko E, Luo W, Peng L, Wang X, Ferrone S. Mouse dendritic-endothelial cell hybrids and 4-1BB costimulation elicit antitumor effects mediated by broad antiangiogenic immunity. Cancer Research. 2007;67(16):7875–7884. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Šalomskaite-Davalgiene S, Čepurniene K, Šatkauskas S, Venslauskas MS, Mir LM. Extent of cell electrofusion in vitro and in vivo is cell line dependent. Anticancer Research. 2009;29(8):3125–3130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gong J, Apostolopoulos V, Chen D, et al. Selection and characterization of MUC1-specific CD8+ T cells from MUC1 transgenic mice immunized with dendritic-carcinoma fusion cells. Immunology. 2000;101(3):316–324. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2000.00101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Koido S, Tanaka Y, Chen D, Kufe D, Gong J. The kinetics of in vivo priming of CD4 and CD8 T cells by dendritic/tumor fusion cells in MUC1-transgenic mice. The Journal of Immunology. 2002;168(5):2111–2117. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.5.2111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kao JY, Gong Y, Chen CM, Zheng QD, Chen JJ. Tumor-derived TGF-β reduces the efficacy of dendritic cell/tumor fusion vaccine. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(7):3806–3811. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.7.3806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iinuma T, Homma S, Noda T, Kufe D, Ohno T, Toda G. Prevention of gastrointestinal tumors based on adenomatous polyposis coli gene mutation by dendritic cell vaccine. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2004;113(9):1307–1317. doi: 10.1172/JCI17323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suzuki T, Fukuhara T, Tanaka M, et al. Vaccination of dendritic cells loaded with interleukin-12-secreting cancer cells augments in vivo antitumor immunity: characteristics of syngeneic and allogeneic antigen-presenting cell cancer hybrid cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(1):58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kao JY, Zhang M, Chen CM, Chen JJ. Superior efficacy of dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccine compared with tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cell vaccine in colon cancer. Immunology Letters. 2005;101(2):154–159. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2005.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu F, Ye YJ, Cui ZR, Wang S. Allogeneic dendritomas induce anti-tumour immunity against metastatic colon cancer. Scandinavian Journal of Immunology. 2005;61(4):364–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2005.01572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yasuda T, Kamigaki T, Kawasaki K, et al. Superior anti-tumor protection and therapeutic efficacy of vaccination with allogeneic and semiallogeneic dendritic cell/tumor cell fusion hybrids for murine colon adenocarcinoma. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2007;56(7):1025–1036. doi: 10.1007/s00262-006-0252-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cho EI, Tan C, Koski GK, Cohen PA, Shu S, Lee WT. Toll-like receptor agonists as third signals for dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccines. Head and Neck. 2010;32(6):700–707. doi: 10.1002/hed.21241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gong J, Chen D, Kashiwaba M, et al. Reversal of tolerance to human MUC1 antigen in MUC1 transgenic mice immunized with fusions of dendritic and carcinoma cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1998;95(11):6279–6283. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.11.6279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lindner M, Schirrmacher V. Tumour cell-dendritic cell fusion for cancer immunotherapy: comparison of therapeutic efficiency of polyethylen-glycol versus electro-fusion protocols. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2002;32(3):207–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2362.2002.00968.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xia J, Tanaka Y, Koido S, et al. Prevention of spontaneous breast carcinoma by prophylactic vaccination with dendritic/tumor fusion cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(4):1980–1986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.4.1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen D, Xia J, Tanaka Y, et al. Immunotherapy of spontaneous mammary carcinoma with fusions of dendritic cells and mucin 1-positive carcinoma cells. Immunology. 2003;109(2):300–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.2003.01656.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tamai H, Watanabe S, Zheng R, et al. Effective treatment of spontaneous metastases derived from a poorly immunogenic murine mammary carcinoma by combined dendritic-tumor hybrid vaccination and adoptive transfer of sensitized T cells. Clinical Immunology. 2008;127(1):66–77. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang M, Berndt BE, Chen JJ, Kao JY. Expression of a soluble TGF-β receptor by tumor cells enhances dendritic cell/tumor fusion vaccine efficacy. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(5):3690–3697. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.5.3690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo GH, Chen SZ, Yu J, et al. In vivo anti-tumor effect of hybrid vaccine of dendritic cells and esophageal carcinoma cells on esophageal carcinoma cell line 109 in mice with severe combined immune deficiency. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2008;14(8):1167–1174. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ziske C, Etzrodt PE, Eliu AS, et al. Increase of in vivo antitumoral activity by CD40L (CD154) gene transfer into pancreatic tumor cell-dendritic cell hybrids. Pancreas. 2009;38(7):758–765. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e3181ae5e1a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yamamoto M, Kamigaki T, Yamashita K, et al. Enhancement of anti-tumor immunity by high levels of Th1 and Th17 with a combination of dendritic cell fusion hybrids and regulatory T cell depletion in pancreatic cancer. Oncology Reports. 2009;22(2):337–343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Homma S, Toda G, Gong J, Kufe D, Ohno T. Preventive antitumor activity against hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) induced by immunization with fusions of dendritic cells and HCC cells in mice. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2001;36(11):764–771. doi: 10.1007/s005350170019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang JK, Li J, Zhang J, Chen HB, Chen SB. Antitumor immunopreventive and immunotherapeutic effect in mice induced by hybrid vaccine of dendritic cells and hepatocarcinoma in vivo. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;9(3):479–484. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v9.i3.479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Iriei M, Homma S, Komita H, et al. Inhibition of spontaneous development of liver tumors by inoculation with dendritic cells loaded with hepatocellular carcinoma cells in C3H/HeNCRJ mice. International Journal of Cancer. 2004;111(2):238–245. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang HM, Zhang LW, Liu WC, Cheng J, Si XM, Ren J. Comparative analysis of DC fused with tumor cells or transfected with tumor total RNA as potential cancer vaccines against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cytotherapy. 2006;8(6):580–588. doi: 10.1080/14653240600991353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sheng XIL, Zhang H. In-vitro activation of cytotoxic T lymphocytes by fusion of mouse hepatocellular carcinoma cells and lymphotactin gene-modified dendritic cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2007;13(44):5944–5950. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i44.5944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Šímová J, Bubeník J, Bieblová J, Indrová M, Jandlová T. Immunotherapeutic efficacy of vaccines generated by fusion of dendritic cells and HPV16-associated tumour cells. Folia Biologica. 2005;51(1):19–24. doi: 10.14712/fb2005051010019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Savai R, Schermuly RT, Schneider M, et al. Hybrid-primed lymphocytes and hybrid vaccination prevent tumor growth of Lewis lung carcinoma in mice. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2006;29(2):175–187. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000197096.38476.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Savai R, Schermuly RT, Pullamsetti SS, et al. A combination hybrid-based vaccination/adoptive cellular therapy to prevent tumor growth by involvement of T cells. Cancer Research. 2007;67(11):5443–5453. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ou X, Cai S, Liu P, et al. Enhancement of dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccine potency by indoleamine-pyrrole 2,3-dioxygenase inhibitor, 1-MT. Journal of Cancer Research and Clinical Oncology. 2008;134(5):525–533. doi: 10.1007/s00432-007-0315-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Siders WM, Vergilis KL, Johnson C, Shields J, Kaplan JM. Induction of specific antitumor immunity in the mouse with the electrofusion product of tumor cells and dendritic cells. Molecular Therapy. 2003;7(4):498–505. doi: 10.1016/s1525-0016(03)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kjaergaard J, Shimizu K, Shu S. Electrofusion of syngeneic dendritic cells and tumor generates potent therapeutic vaccine. Cellular Immunology. 2003;225(2):65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2003.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Matsue H, Matsue K, Edelbaum D, Walters M, Morita A, Takashima A. New strategy for efficient selection of dendritic cell-tumor hybrids and clonal heterogeneity of resulting hybrids. Cancer Biology and Therapy. 2004;3(11):1145–1151. doi: 10.4161/cbt.3.11.1217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kim GY, Chae HJ, Kim KH, et al. Dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccine prevents tumor growth in vivo. Bioscience, Biotechnology and Biochemistry. 2007;71(1):215–221. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu Z, Ma B, Zhou Y, et al. Allogeneic tumor vaccine produced by electrofusion between osteosarcoma cell line and dendritic cells in the induction of antitumor immunity. Cancer Investigation. 2007;25(7):535–541. doi: 10.1080/07357900701508918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zheng R, Cohen PA, Paustian CA, et al. Paired toll-like receptor agonists enhance vaccine therapy through induction of interleukin-12. Cancer Research. 2008;68(11):4045–4049. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yanai S, Adachi Y, Fuijisawa JI, et al. Anti-tumor effects of fusion cells of type 1 dendritic cells and Meth A tumor cells using hemagglutinating virus of Japan-envelope. International Journal of Oncology. 2009;35(2):249–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gong J, Koido S, Chen D, et al. Immunization against murine multiple myeloma with fusions of dendritic and plasmacytoma cells is potentiated by interleukin 12. Blood. 2002;99(7):2512–2517. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.7.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang W, Yang H, Zeng H. Enhancing antitumor by immunization with fusion of dendritic cells and engineered tumor cells. Journal of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Medical Science. 2002;22(1):1–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02904773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Liu Y, Zhang W, Chan T, Saxena A, Xiang J. Engineered fusion hybrid vaccine of IL-4 gene-modified myeloma and relative mature dendritic cells enhances antitumor immunity. Leukemia Research. 2002;26(8):757–763. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2126(02)00002-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hao S, Bi X, Xu S, et al. Enhanced antitumor immunity derived from a novel vaccine of fusion hybrid between dendritic and engineered myeloma cells. Experimental Oncology. 2004;26(4):300–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Xia D, Li F, Xiang J. Engineered fusion hybrid vaccine of IL-18 gene-modified tumor cells and dendritic cells induces enhanced antitumor immunity. Cancer Biotherapy and Radiopharmaceuticals. 2004;19(3):322–330. doi: 10.1089/1084978041424990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shi M, Su L, Hao S, Guo X, Xiang J. Fusion hybrid of dendritic cells and engineered tumor cells expressing interleukin-12 induces type 1 immune responses against tumor. Tumori. 2005;91(6):531–538. doi: 10.1177/030089160509100614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Quéant S, Sarde CO, Gobert MG, Kadouche J, Roseto A. Antitumor response against myeloma cells by immunization with mouse syngenic dendritoma. Hybridoma. 2005;24(4):182–188. doi: 10.1089/hyb.2005.24.182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Alvarez E, Moga E, Barquinero J, Sierra J, Briones J. Dendritic and tumor cell fusions transduced with adenovirus encoding CD40L eradicate B-cell lymphoma and induce a Th17-type response. Gene Therapy. 2010;17(4):469–477. doi: 10.1038/gt.2009.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lespagnard L, Mettens P, Verheyden AM, et al. Dendritic cells fused with mastocytoma cells elicit therapeutic antitumor immunity. International Journal of Cancer. 1998;76(2):250–258. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(19980413)76:2<250::aid-ijc13>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wells JW, Cowled CJ, Darling D, et al. Semi-allogeneic dendritic cells can induce antigen-specific T-cell activation, which is not enhanced by concurrent alloreactivity. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2007;56(12):1861–1873. doi: 10.1007/s00262-007-0328-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iinuma H, Okinaga K, Fukushima R, et al. Superior protective and therapeutic effects of IL-12 and IL-18 gene-transduced dendritic neuroblastoma fusion cells on liver metastasis of murine neuroblastoma. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(6):3461–3469. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.6.3461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Draube A, Beyer M, Schumer S, et al. Efficient activation of autologous tumor-specific T cells: a simple coculture technique of autologous dendritic cells compared to established cell fusion strategies in primary human colorectal carcinoma. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2007;30(4):359–369. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e31802bfefe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, et al. Dendritic cells fused with allogeneic colorectal cancer cell line present multiple colorectal cancer-specific antigens and induce antitumor immunity against autologous tumor cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(21):7891–7900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Koido S, Hara E, Torii A, et al. Induction of antigen-specific CD4- and CD8-mediated T-cell responses by fusions of autologous dendritic cells and metastatic colorectal cancer cells. International Journal of Cancer. 2005;117(4):587–595. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hock BD, Roberts G, McKenzie JL, et al. Exposure to the electrofusion process can increase the immunogenicity of human cells. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2005;54(9):880–890. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0659-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, et al. Streptococcal preparation OK-432 promotes fusion efficiency and enhances induction of antigen-specific CTL by fusions of dendritic cells and colorectal cancer cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;178(1):613–622. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, et al. Synergistic induction of antigen-specific CTL by fusions of TLR-stimulated dendritic cells and heat-stressed tumor cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2007;179(7):4874–4883. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.7.4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yang JY, Cao DY, Ma LY, Liu WC. Dendritic cells fused with allogeneic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line compared with fused autologous tumor cells as hepatocellular carcinoma vaccines. Hepatology Research. 2010;40(5):505–513. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2010.00625.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Imura K, Ueda Y, Hayashi T, et al. Induction of cytotoxic T lymphocytes against human cancer cell lines using dendritic cell-tumor cell hybrids generated by a newly developed electrofusion technique. International Journal of Oncology. 2006;29(3):531–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Matsumoto S, Saito H, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M. Allogeneic gastric cancer cell-dendritic cell hybrids induce tumor antigen (carcinoembryonic antigen) specific CD8+ T cells. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2006;55(2):131–139. doi: 10.1007/s00262-005-0684-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Koido S, Hara E, Homma S, et al. Dendritic/pancreatic carcinoma fusions for clinical use: comparative functional analysis of healthy-versus patient-derived fusions. Clinical Immunology. 2010;135(3):384–400. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Gong J, Avigan D, Chen D, et al. Activation of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes by fusions of human dendritic cells and breast carcinoma cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2000;97(6):2715–2718. doi: 10.1073/pnas.050587197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Zhang Y, Ma B, Zhou Y, et al. Dendritic cells fused with allogeneic breast cancer cell line induce tumor antigen-specific CTL responses against autologous breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 2007;105(3):277–286. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9457-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Serhal K, Baillou C, Ghinea N, et al. Characteristics of hybrid cells obtained by dendritic cell/tumour cell fusion in a T-47D breast cancer cell line model indicate their potential as anti-tumour vaccines. International Journal of Oncology. 2007;31(6):1357–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Koido S, Tanaka Y, Tajiri H, Gong J. Generation and functional assessment of antigen-specific T cells stimulated by fusions of dendritic cells and allogeneic breast cancer cells. Vaccine. 2007;25(14):2610–2619. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.12.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Vasir B, Wu Z, Crawford K, et al. Fusions of dendritic cells with breast carcinoma stimulate the expansion of regulatory T cells while concomitant exposure to IL-12, CpG oligodeoxynucleotides, and Anti-CD3/CD28 promotes the expansion of activated tumor reactive cells. The Journal of Immunology. 2008;181(1):808–821. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.1.808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rosenblatt J, Wu Z, Vasir B, et al. Generation of tumor-specific t lymphocytes using dendritic cell/tumor fusions and anti-CD3/CD28. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2010;33(2):155–166. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181bed253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Weise JB, Maune S, Görögh T, et al. A dendritic cell based hybrid cell vaccine generated by electrofusion for immunotherapy strategies in HNSCC. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2004;31(2):149–153. doi: 10.1016/j.anl.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Gong J, Nikrui N, Chen D, et al. Fusions of human ovarian carcinoma cells with autologous or allogeneic dendritic cells induce antitumor immunity. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;165(3):1705–1711. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Koido S, Ohana M, Liu C, et al. Dendritic cells fused with human cancer cells: morphology, antigen expression, and T cell stimulation. Clinical Immunology. 2004;113(3):261–269. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2004.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Koido S, Nikrui N, Ohana M, et al. Assessment of fusion cells from patient-derived ovarian carcinoma cells and dendritic cells as a vaccine for clinical use. Gynecologic Oncology. 2005;99(2):462–471. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.07.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Cheong SC, Blangenois I, Franssen JD, et al. Generation of cell hybrids via a fusogenic cell line. Journal of Gene Medicine. 2006;8(7):919–928. doi: 10.1002/jgm.906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Lundqvist A, Palmborg A, Bidla G, Whelan M, Pandha H, Pisa P. Allogeneic tumor-dendritic cell fusion vaccines for generation of broad prostate cancer T-cell responses. Medical Oncology. 2004;21(2):155–165. doi: 10.1385/MO:21:2:155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kim TB, Park HK, Chang JH, et al. The establishment of dendritic cell-tumor fusion vaccines for hormone refractory prostate cancer cell. Korean Journal of Urology. 2010;51(2):139–144. doi: 10.4111/kju.2010.51.2.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gottfried E, Krieg R, Eichelberg C, Andreesen R, Mackensen A, Krause SW. Characterization of cells prepared by dendritic cell-tumor cell fusion. Cancer Immunity. 2002;5:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hu Z, Liu S, Mai X, Hu Z, Liu C. Anti-tumor effects of fusion vaccine prepared by renal cell carcinoma 786-O cell line and peripheral blood dendritic cells of healthy volunteers in vitro and in human immune reconstituted SCID mice. Cellular Immunology. 2010;262(2):112–119. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Koido S, Homma S, Hara E, et al. In vitro generation of cytotoxic and regulatory T cells by fusions of human dendritic cells and hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Journal of Translational Medicine. 2008;6, article 51 doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Cao DY, Yang JY, Yue SQ, et al. Comparative analysis of DC fused with allogeneic hepatocellular carcinoma cell line HepG2 and autologous tumor cells as potential cancer vaccines against hepatocellular carcinoma. Cellular Immunology. 2009;259(1):13–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2009.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xu F, Ye YJ, Liu W, Kong M, He Y, Wang S. Dendritic cell/tumor hybrids enhances therapeutic efficacy against colorectal cancer liver metastasis in SCID mice. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010;45(6):707–713. doi: 10.3109/00365521003650180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Galea-Lauri J, Darling D, Mufti G, Harrison P, Farzaneh F. Eliciting cytotoxic T lymphocytes against acute myeloid leukemia-derived antigens: evaluation of dendritic cell-leukemia cell hybrids and other antigen-loading strategies for dendritic cell-based vaccination. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2002;51(6):299–310. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0284-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kokhaei P, Rezvany MR, Virving L, et al. Dendritic cells loaded with apoptotic tumour cells induce a stronger T-cell response than dendritic cell-tumour hybrids in B-CLL. Leukemia. 2003;17(5):894–899. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Gong J, Koido S, Kato Y, et al. Induction of anti-leukemic cytotoxic T lymphocytes by fusion of patient-derived dendritic cells with autologous myeloblasts. Leukemia Research. 2004;28(12):1303–1312. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2004.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Banat GA, Usluoglu N, Hoeck M, Ihlow K, Hoppmann S, Pralle H. Dendritic cells fused with core binding factor-beta positive acute myeloid leukaemia blast cells induce activation of cytotoxic lymphocytes. British Journal of Haematology. 2004;126(4):593–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Allgeier T, Garhammer S, Nößner E, et al. Dendritic cell-based immunogens for B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Letters. 2007;245(1-2):275–283. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2006.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lei Z, Zhang GM, Hong M, Feng ZH, Huang B. Fusion of dendritic cells and CD34+CD38− acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells potentiates targeting AML-initiating cells by specific CTL induction. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2009;32(4):408–414. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181a01abb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Raje N, Hideshima T, Davies FE, et al. Tumour cell/dendritic cell fusions as a vaccination strategy for multiple myeloma. British Journal of Haematology. 2004;125(3):343–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.04929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Vasir B, Borges V, Wu Z, et al. Fusion of dendritic cells with multiple myeloma cells results in maturation and enhanced antigen presentation. British Journal of Haematology. 2005;129(5):687–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Yu Z, Ma B, Zhou Y, Zhang M, Qiu X, Fan Q. Activation of antitumor cytotoxic T lymphocytes by fusion of patient-derived dendritic cells with autologous osteosarcoma. Experimental Oncology. 2005;27(4):273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Guo W, Guo Y, Tang S, Qu H, Zhao H. Dendritic cell-Ewing’s sarcoma cell hybrids enhance antitumor immunity. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research. 2008;466(9):2176–2183. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0348-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Jantscheff P, Spagnoli G, Zajac P, Rochlitz C. Cell fusion: an approach to generating constitutively proliferating human tumor antigen-presenting cells. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2002;51(7):367–375. doi: 10.1007/s00262-002-0295-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Parkhurst MR, DePan C, Riley JP, Rosenberg SA, Shu S. Hybrids of dendritic cells and tumor cells generated by electrofusion simultaneously present immunodominant epitopes from multiple human tumor-associated antigens in the context of MHC class I and class II molecules. The Journal of Immunology. 2003;170(10):5317–5325. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.10.5317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Trevor KT, Cover C, Ruiz YW, et al. Generation of dendritic cell-tumor cell hybrids by electrofusion for clinical vaccine application. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2004;53(8):705–714. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0512-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Neves AR, Ensina LFC, Anselmo LB, et al. Dendritic cells derived from metastatic cancer patients vaccinated with allogeneic dendritic cell-autologous tumor cell hybrids express more CD86 and induce higher levels of interferon-gamma in mixed lymphocyte reactions. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2005;54(1):61–66. doi: 10.1007/s00262-004-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sloan AE, Parajuli P. Human autologous dendritic cell-glioma fusions: feasibility and capacity to stimulate T cells with proliferative and cytolytic activity. Journal of Neuro-Oncology. 2003;64(1-2):177–183. doi: 10.1007/BF02700032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Sukhorukov VL, Reuss R, Endter JM, et al. A biophysical approach to the optimisation of dendritic-tumour cell electrofusion. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;346(3):829–839. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.05.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Aarntzen EHJG, Figdor CG, Adema GJ, Punt CJA, de Vries IJM. Dendritic cell vaccination and immune monitoring. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2008;57(10):1559–1568. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0553-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Puccetti P, Bianchi R, Fioretti MC, et al. Use of a skin test assay to determine tumor-specific CD8+ T cell reactivity. European Journal of Immunology. 1994;24(6):1446–1452. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Lesterhuis WJ, de Vries IJM, Schuurhuis DH, et al. Vaccination of colorectal cancer patients with CEA-loaded dendritic cells: antigen-specific T cell responses in DTH skin tests. Annals of Oncology. 2006;17(6):974–980. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Märten A, Renoth S, Heinicke T, et al. Allogeneic dendritic cells fused with tumor cells: preclinical results and outcome of a clinical phase I/II trial in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Human Gene Therapy. 2003;14(5):483–494. doi: 10.1089/104303403321467243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Waanders GA, Rimoldi D, Liénard D, et al. Melanoma-reactive human cytotoxic T lymphocytes derived from skin biopsies of delayed-type hypersensitivity reactions induced by injection of an autologous melanoma cell line. Clinical Cancer Research. 1997;3(5):685–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.de Vries IJM, Bernsen MR, Lesterhuis WJ, et al. Immunomonitoring tumor-specific T cells in delayed-type hypersensitivity skin biopsies after dendritic cell vaccination correlates with clinical outcome. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2005;23(24):5779–5787. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.06.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2000;92(3):205–216. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Miller AB, Hoogstraten B, Staquet M, Winkler A. Reporting results of cancer treatment. Cancer. 1981;47(1):207–214. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19810101)47:1<207::aid-cncr2820470134>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Morse MA, Hall JR, Plate JMD. Countering tumor-induced immunosuppression during immunotherapy for pancreatic cancer. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy. 2009;9(3):331–339. doi: 10.1517/14712590802715756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Kormelink TG, Abudukelimu A, Redegeld FA. Mast cells as target in cancer therapy. Current Pharmaceutical Design. 2009;15(16):1868–1878. doi: 10.2174/138161209788453284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Fassnacht M, Lee J, Milazzo C, et al. Induction of CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell responses to the human stromal antigen, fibroblast activation protein: implication for cancer immunotherapy. Clinical Cancer Research. 2005;11(15):5566–5571. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Hasbold J, Gett AV, Rush JS, et al. Quantitative analysis of lymphocyte differentiation and proliferation in vitro using carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester. Immunology and Cell Biology. 1999;77(6):516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1999.00874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Tanaka Y, Koido S, Xia J, et al. Development of antigen-specific CD8+ CTL in MHC class I-deficient mice through CD4 to CD8 conversion. The Journal of Immunology. 2004;172(12):7848–7858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.12.7848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Avigan D, Vasir B, Gong J, et al. Fusion cell vaccination of patients with metastatic breast and renal cancer induces immunological and clinical responses. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(14):4699–4708. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Avigan DE, Vasir B, George DJ, et al. Phase I/II study of vaccination with electrofused allogeneic dendritic cells/autologous tumor-derived cells in patients with stage IV renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2007;30(7):749–761. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3180de4ce8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Kikuchi T, Akasaki Y, Abe T, et al. Vaccination of glioma patients with fusions of dendritic and glioma cells and recombinant human interleukin 12. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2004;27(6):452–459. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200411000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Homma S, Kikuchi T, Ishiji N, et al. Cancer immunotherapy by fusions of dendritic and tumour cells and rh-IL-12. European Journal of Clinical Investigation. 2005;35(4):279–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2005.01494.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Czerkinsky C, Andersson G, Ekre HP, Nilsson LA, Klareskog L, Ouchterlony O. Reverse ELISPOT assay for clonal analysis of cytokine production. I. Enumeration of gamma-interferon-secretion cells. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1988;110(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(88)90079-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Suni MA, Picker LJ, Maino VC. Detection of antigen-specific T cell cytokine expression in whole blood by flow cytometry. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1998;212(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00004-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Schmittel A, Keilholz U, Scheibenbogen C. Evaluation of the interferon-γ ELISPOT-assay for quantification of peptide specific T lymphocytes from peripheral blood. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1997;210(2):167–174. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(97)00184-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Schmittel A, Keilholz U, Thiel E, Scheibenbogen C. Quantification of tumor-specific T lymphocytes with the ELISPOT assay. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2000;23(3):289–295. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200005000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Rosenblatt J, Vasir B, Uhl L, et al. Vaccination with dendritic cell/tumor fusion cells results in cellular and humoral antitumor immune responses in patients with multiple myeloma. Blood. 2011;117(2):393–402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-04-277137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144.Scheibenbogen C, Schmittel A, Keilholz U, et al. Phase 2 trial of vaccination with tyrosinase peptides and granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in patients with metastatic melanoma. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2000;23(2):275–281. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200003000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Liu L, Chahroudi A, Silvestri G, et al. Visualization and quantification of T cell-mediated cytotoxicity using cell-permeable fluorogenic caspase substrates. Nature Medicine. 2002;8(2):185–189. doi: 10.1038/nm0202-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Jerome KR, Sloan DD, Aubert M. Measuring T-cell-mediated cytotoxicity using antibody to activated caspase 3. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(1):4–5. doi: 10.1038/nm0103-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Goldberg JE, Sherwood SW, Clayberger C. A novel method for measuring CTL and NK cell-mediated cytotoxicity using annexin V and two-color flow cytometry. Journal of Immunological Methods. 1999;224(1-2):1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Homma S, Matai K, Irie M, Ohno T, Kufe D, Toda G. Immunotherapy using fusions of autologous dendritic cells and tumor cells showed effective clinical response in a patient with advanced gastric carcinoma. Journal of Gastroenterology. 2003;38(10):989–994. doi: 10.1007/s00535-002-1183-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Kikuchi T, Akasaki Y, Irie M, Homma S, Abe T, Ohno T. Results of a phase I clinical trial of vaccination of glioma patients with fusions of dendritic and glioma cells. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2001;50(7):337–344. doi: 10.1007/s002620100205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Trefzer U, Weingart G, Chen Y, et al. Hybrid cell vaccination for cancer immune therapy: first clinical trial with metastatic melanoma. International Journal of Cancer. 2000;85(5):618–626. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(20000301)85:5<618::aid-ijc4>3.0.co;2-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Trefzer U, Herberth G, Wohlan K, et al. Tumour-dendritic hybrid cell vaccination for the treatment of patients with malignant melanoma: immunological effects and clinical results. Vaccine. 2005;23(17-18):2367–2373. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2005.01.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Krause SW, Neumann C, Soruri A, Mayer S, Peters JH, Andreesen R. The treatment of patients with disseminated malignant melanoma by vaccination with autologous cell hybrids of tumor cells and dendritic cells. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2002;25(5):421–428. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200209000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 153.Haenssle HA, Krause SW, Emmert S, et al. Hybrid cell vaccination in metastatic melanoma: clinical and immunologic results of a phase I/II study. Journal of Immunotherapy. 2004;27(2):147–155. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200403000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 154.Zhou J, Weng D, Zhou F, et al. Patient-derived renal cell carcinoma cells fused with allogeneic dendritic cells elicit anti-tumor activity: in vitro results and clinical responses. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy. 2009;58(10):1587–1597. doi: 10.1007/s00262-009-0668-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 155.Su H, Chang DS, Gambhir SS, Braun J. Monitoring the antitumor response of naive and memory CD8 T cells in RAG1−/− mice by positron-emission tomography. The Journal of Immunology. 2006;176(7):4459–4467. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.4459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 156.Finn OJ. Molecular origins of cancer: cancer immunology. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2008;358(25):2704–2715. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra072739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 157.Chattopadhyay PK, Yu J, Roederer M. A live-cell assay to detect antigen-specific CD4+ T cells with diverse cytokine profiles. Nature Medicine. 2005;11(10):1113–1117. doi: 10.1038/nm1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 158.Altman JD, Moss PAH, Goulder PJR, et al. Phenotypic analysis of antigen-specific T lymphocytes. Science. 1996;274(5284):94–96. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5284.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 159.Klebanoff CA, Gattinoni L, Restifo NP. CD8+ T-cell memory in tumor immunology and immunotherapy. Immunological Reviews. 2006;211:214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2006.00391.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 160.Walker EB, Haley D, Miller W, et al. gp100(209-2M) peptide immunization of human lymphocyte antigen-A2+ stage I-III melanoma patients induces significant increase in antigen-specific effector and long-term memory CD8+ T cells. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10(2):668–680. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-0095-03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 161.Houtenbos I, Westers TM, Dijkhuis A, de Gruijl TD, Ossenkoppele GJ, van de Loosdrecht AA. Leukemia-specific T-cell reactivity induced by leukemic dendritic cells is augmented by 4-1BB targeting. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(1):307–315. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 162.Kalams SA, Johnson RP, Trocha AK, et al. Longitudinal analysis of T cell receptor (TCR) gene usage by human immunodeficiency virus 1 envelope-specific cytotoxic T lymphocyte clones reveals a limited TCR repertoire. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(4):1261–1271. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.4.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 163.Ramsdell F, Fowlkes BJ. Clonal deletion versus clonal anergy: the role of the thymus in inducing self tolerance. Science. 1990;248(4961):1342–1348. doi: 10.1126/science.1972593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 164.Law JP, Hirschkorn DF, Owen RE, Biswas HH, Norris PJ, Lanteri MC. The importance of Foxp3 antibody and fixation/permeabilization buffer combinations in identifying CD4+CD25+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. Cytometry Part A. 2009;75(12):1040–1050. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 165.Teicher BA. Transforming growth factor-β and the immune response to malignant disease. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(21):6247–6251. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 166.Fricke I, Mirza N, Dupont J, et al. Vascular endothelial growth factor-trap overcomes defects in dendritic cell differentiation but does not improve antigen-specific immune responses. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(16):4840–4848. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 167.Elgert KD, Alleva DG, Mullins DW. Tumor-induced immune dysfunction: the macrophage connection. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 1998;64(3):275–290. doi: 10.1002/jlb.64.3.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 168.Houston A, Bennett MW, O’Sullivan GC, Shanahan F, O’Connell J. Fas ligand mediates immune privilege and not inflammation in human colon cancer, irrespective of TGF-β expression. British Journal of Cancer. 2003;89(7):1345–1351. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 169.Takeda K, Kojima Y, Uno T, et al. Combination therapy of established tumors by antibodies targeting immune activating and suppressing molecules. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(10):5493–5501. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 170.Uyttenhove C, Pilotte L, Théate I, et al. Evidence for a tumoral immune resistance mechanism based on tryptophan degradation by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. Nature Medicine. 2003;9(10):1269–1274. doi: 10.1038/nm934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 171.Szajnik M, Czystowska M, Szczepanski MJ, Mandapathil M, Whiteside TL. Tumor-derived microvesicles induce, expand and up-regulate biological activities of human regulatory T cells (Treg) PLoS One. 2010;5(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011469. Article ID e11469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 172.Strauss L, Bergmann C, Szczepanski M, Gooding W, Johnson JT, Whiteside TL. A unique subset of CD4+CD25highFoxp3+T cells secreting interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-β1 mediates suppression in the tumor microenvironment. Clinical Cancer Research. 2007;13(15):4345–4354. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 173.Plebanski M, Katsara M, Sheng KC, Xiang SD, Apostolopoulos V. Methods to measure T-cell responses. Expert Review of Vaccines. 2010;9(6):595–600. doi: 10.1586/erv.10.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]