Abstract

Neuroimaging and lesion studies have appeared to converge on the idea that the hippocampus selectively supports recollection. However, these studies usually involve a comparison between strong recollection-based memories and weak familiarity-based memories. Studies that have avoided confounding memory strength with recollection and familiarity have found that the hippocampus supports both recollection and familiarity. We argue that the functional organization of the medial temporal lobe (MTL) is unlikely to be illuminated by the psychological distinction between recollection and familiarity and will be better informed by findings from neuroanatomy and neurophysiology. These findings suggest that the different structures of the MTL process different attributes of experience. By representing the widest array of attributes, the hippocampus supports recollection-based and familiarity-based memory of multi-attribute stimuli.

Introduction

A memory is viewed as consisting of a collection or set of different types of information, each type being called an attribute. Thus, the constituents of a memory are attributes

Benton Underwood, 1983

The discovery that medial temporal lobe (MTL) structures are essential for memory came from early descriptions of the noted patient H.M. [1, 2]. Subsequent work in this same tradition established key principles about the organization of memory [3, 4]. In particular, cumulative studies of an animal model of human memory impairment in the nonhuman primate [5], together with additional human cases, identified the structures in the MTL that are important for memory: the hippocampus and the adjacent entorhinal, perirhinal, and parahippocampal cortices [6]. Recently, a considerable body of research has focused on possible differences between these structures in how they support memory. One proposal holds that the functional organization of the MTL can be understood in terms of a longstanding distinction between the psychological constructs of recollection and familiarity. An alternative view holds that the function of MTL structures is not illuminated by this distinction and is better informed by findings from neuroanatomy and neurophysiology that help to identify the attributes of memory supported by different structures. After a brief overview of the problems associated with using the constructs of recollection and familiarity to identify the functions of different MTL structures, we elaborate on the proposal that the functions of MTL structures are best identified on the basis of the attributes of experience they process. We suggest that the hippocampus—more than the other structures of the MTL—is involved in combining the different aspects of experience, which supports the later recollection-based and familiarity-based memory of multi-attribute stimuli.

Recollection and Familiarity in the Medial Temporal Lobe

Dual-process theory [7, 8] holds that recognition memory can be based on a simple sense of familiarity (e.g., when all one knows on seeing a person is that the face is familiar) or on the recollection of additional details that are not present (e.g., when one can specifically remember meeting the person before). Brown and Aggleton [9] proposed that the hippocampus selectively supports recollection, whereas the perirhinal cortex selectively supports familiarity. Much evidence apparently consistent with this view has come from neuroimaging studies and lesion studies, using a variety of behavioral methods to assess recollection and familiarity in humans [10–12]. Additional evidence has come from lesion studies and single-unit recording studies in animals using still other behavioral methods [13]. Yet recent findings suggest that it is time to abandon these ideas about recollection and familiarity and to consider a different approach to the function of MTL structures.

Various methods have been used in an effort to assess recollection and familiarity. For example, participants are often asked to express their confidence in each recognition decision (e.g., using a 6-point confidence scale ranging from 1 = “Sure New” to 6 = “Sure Old”); or to indicate directly for each decision whether it was in fact based on recollection or familiarity (by declaring “Remember” or “Know,” respectively). Using these methods, recollection-based decisions are identified by high confidence (e.g., a rating of 6) or by a Remember judgment, whereas familiarity-based decisions are identified by lower confidence (e.g., a rating of 1 – 5) or by a Know judgment. These two methods rely on subjective reports, but more objective methods have also been used (e.g., in studies of source memory), wherein participants are asked to recall specific details associated with the items that they correctly recognize. Thus, in a recognition test of concrete nouns, participants might be asked (for each item correctly recognized) whether the item was accompanied at study by a question about the item's pleasantness (Source question A) or by a question about its size (Source question B). Recollection-based decisions are identified by correct source memory judgments (item-correct plus source-correct trials), and familiarity-based decisions are identified by incorrect source memory judgments (item-correct plus source-incorrect trials). The findings obtained with these methods tell a mostly consistent story – that the hippocampus selectively subserves recollection. However, this story holds only so long as one adopts the strong assumption that confidence and accuracy are high whenever recollection occurs. This assumption turns out to be the Achilles' heel of this program of research.

Studies that adopt the strong assumption that recollection always yields high confidence and high accuracy also necessarily assume that recognition decisions made with lower confidence and lower accuracy are familiarity-based. By this view, a comparison between strong (high confidence) memories and weak (low confidence) memories is an effective way to distinguish between recollection and familiarity. For example, neuroimaging studies have used confidence ratings as a direct proxy for these constructs [14]. Similarly, in Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) analyses of patients with memory impairment, quantitative estimates of recollection and familiarity have often been derived from a specific model [15, 16], whereby recollection yields only (and accounts for most) decisions made with the highest level of confidence (e.g., a 6 on a 6-point scale), and familiarity accounts for all decisions made with lower levels of confidence (e.g., 1 through 5 on a 6-point scale) [17–19].

Studies that use the Remember/Know procedure to investigate recollection and familiarity [e.g., 20, 21, 22] also rely on this same assumption, albeit indirectly. These studies use Remember judgments to identify recollection-based decisions, and Know judgments to identify familiarity-based decisions. It is well known that Remember judgments are made with high confidence and high accuracy, whereas Know judgments are, on average (and without exception) made with lower confidence and lower accuracy [23–25]. Thus, once again, strong memories are used to identify recollection and weak memories are used to identify familiarity. These same considerations also apply to the more objective source memory procedure. In this procedure, correct old decisions followed by correct source recollection (item-correct plus source-correct trials) are usually made with high confidence, whereas correct old decisions followed by incorrect source recollection (item-correct plus source-incorrect trials) are usually made with lower confidence [26, 27].

Studies that use these procedures have often concluded that the hippocampus plays a role in recollection but not familiarity (see [13], for a review). In addition, anterior temporal structures have been proposed to be important for familiarity but not recollection [28]. The difficulty with these conclusions is that they are predicated on the assumption that recollection yields strong memory and that weaker memories are therefore familiarity-based (or they are based on a specific model [15, 16] that entails this assumption to estimate recollection and familiarity). Contrary to this assumption, much recent evidence shows that recollection is a continuous process that can vary from weak to strong. For example, the probability of correct source recollection increases in continuous fashion as a function of the confidence expressed in an old/new recognition decision (i.e., source recollection is not associated exclusively with the highest level of old/new confidence) [29]. In addition, when confidence ratings are taken for the source recollection decision itself, the accuracy of source recollection increases continuously as a function of confidence [30].

With respect to the Remember/Know procedure, source recollection is high following Remember judgments and is lower (but almost never absent) following Know judgments [31]. All of these findings, and many more [32–38], indicate that recollection, like familiarity, is a continuous process (from weak to strong). Accordingly, recollection and familiarity cannot be accurately assessed by comparing strong memories to weak memories (whether these memories are identified by confidence ratings, the Remember/Know procedure, or the source memory procedure). Moreover, models of recognition based on the assumption that recollection always yields strong memory [15, 16] cannot extract accurate estimates of recollection and familiarity. In light of these considerations, prior work interpreted to mean that the hippocampus selectively supports recollection provides equal support for an alternative view: that the role of the hippocampus is most evident during the encoding and retrieval of strong memories (whether these strong memories are recollection-based or familiarity-based). The point is that recollection-based memories can be weak and familiarity-based memories can be strong [29, 39]. Accordingly, methods that do not confound recollection and familiarity with memory strength must be used.

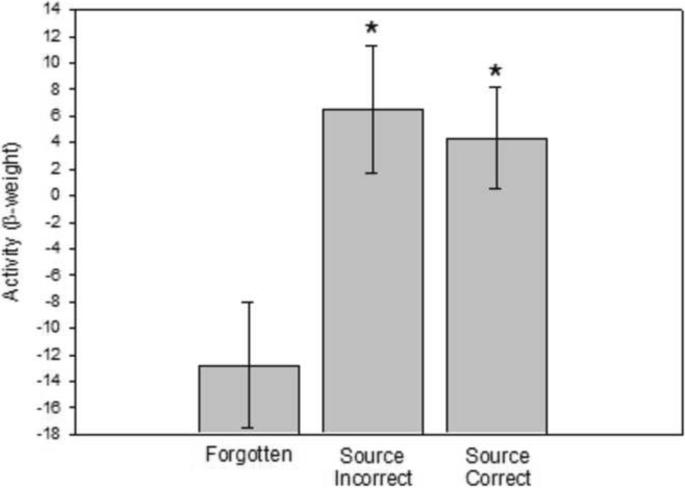

A recent neuroimaging experiment using a source memory procedure illustrates the usefulness of equating for memory strength when investigating the role of the hippocampus in recollection and familiarity [27]. A common finding in neuroimaging studies is that, compared to activity associated with forgotten items, hippocampal activity is elevated on trials where both the item is recognized and the source question is answered correctly (item-correct plus source-correct trials). Hippocampal activity is usually not elevated for item-correct plus source-incorrect trials [40–45]. These findings have been interpreted to mean that the hippocampus selectively supports recollection, but they could also mean that, in fMRI studies, hippocampal activity is detectable for strong memories (whether they are recollection-based or familiarity-based). Wais et al. [27] measured activity at retrieval after equating the memory strength of item-correct plus source-correct decisions and item-correct plus source-incorrect decisions. Specifically, the analysis was limited to items that received old/new confidence ratings of 5 or 6 (i.e., old decisions made with relatively high confidence regardless of whether source recollection occurred). The finding was that, compared to activity associated with forgotten items, hippocampal activity was elevated to a similar extent for both correct source judgments and incorrect source judgments (Figure 1). Kirwan et al. [46] conducted a similar study (scanning at encoding) and reached similar conclusions. These findings, amongst others [47, 48], suggest that the hippocampus is important for familiarity as well as recollection (for reviews, see [49, 50]).

Figure 1.

Hippocampal activity associated with strong recollection and strong familiarity. In the left hippocampus activity associated with Source-Correct decisions (item-correct plus source-correct items) was greater than the activity associated with Forgotten items. In the same region, activity associated with Incorrect Source decisions (item-correct plus source-incorrect items) was also greater than the activity associated with Forgotten items. To equate for memory strength, the source correct and source incorrect data were based on old decisions made with relatively high confidence (5 or 6 on a 6-point rating scale). Error bars for the two source categories represent the standard error of the mean (s.e.m.) of the difference scores for each comparison, whereas the error bar for the forgotten items represents the root mean square of the s.e.m. values associated with the two individual comparisons (* denotes a difference relative to forgotten items, p-corrected< 0.05). Reproduced, with permission, from [27].

In search of the functional organization of the MTL

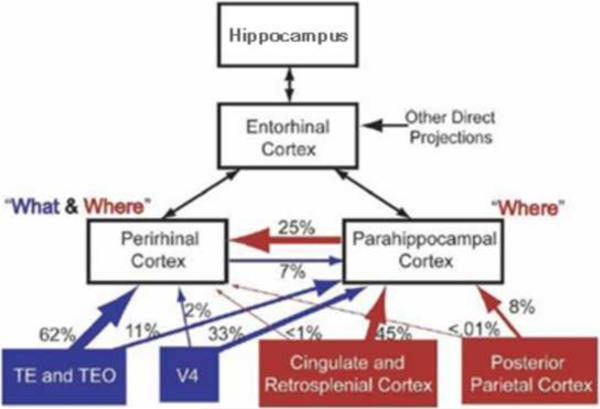

If the psychological distinction between recollection and familiarity does not illuminate the organization of the MTL, what does? Some useful suggestions come from neuroanatomical studies of the nonhuman primate [51]. As illustrated in Figure 2, the various structures of the MTL are highly and reciprocally interconnected, but the inputs to each structure are not identical. We next consider how functional distinctions between the structures of the MTL – in particular the perirhinal cortex and the hippocampus – might be better understood in terms of anatomy and physiology than in terms of the psychological distinction between recollection and familiarity.

Figure 2.

Cortical afferents to the medial temporal lobe in the nonhuman primate based on earlier findings [51]. The diagram shows the percentage of cortical input from the“what” (blue) and“where” (red) pathways to the perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices in the medial temporal lobe (black boxes). The box for hippocampus also includes dentate gyrus and subiculum. The data suggest that parahippocampal cortex might be important for spatial memory (red lines and boxes), while perirhinal cortex might be important for visual memory (blue lines and boxes). Perirhinal cortex may also be involved in spatial memory based on the strong input it receives from parahippocampal cortex. Figure adapted from [87].

Perirhinal Cortex

The perirhinal cortex is a polymodal associative area with strong connections to the entorhinal cortex and hippocampus. It lies at the boundary between the highest level of the ventral visual pathway (area TE) and the rest of the MTL, and in the nonhuman primate it receives the majority of its cortical input from visual areas TE and TEO (62%, Figure 2). Inasmuch as these areas are involved in processing visual information, this extensive visual input suggests that perirhinal cortex may be particularly important for remembering visual attributes (see [52] for a review of the considerable evidence supporting this idea).

The idea that perirhinal cortex may be important for visual memory is neutral with respect to its possible role in recollection and familiarity. Familiarity occurs when an item elicits a memory signal that is specific to that item, whereas recollection occurs when a retrieval cue brings to mind the representation of an associated stimulus that is no longer present. Based on anatomy, it seems reasonable to suppose that perirhinal cortex plays an important role in visual familiarity and that it also plays an important role in visual recollection (e.g., when a visual stimulus is used as a retrieval cue to recollect its visual paired associate; see [53]). That is, the important distinction is between visual and nonvisual attributes of memory, not between recollection and familiarity.

Evidence for a memory signal associated with visual stimuli in perirhinal cortex is abundant, and this evidence has been taken to support the claim that this structure is important for familiarity [9, 13]. For example, neurophysiological studies using rats and monkeys have found that neurons in the perirhinal cortex signal novelty by an increased firing rate in response to a simple visual stimulus and then return to baseline as an item is presented repeatedly and becomes more familiar. This phenomenon, termed repetition suppression, has been hypothesized to be the neural basis of familiarity [9]. However, evidence for a visual associative recollection signal in perirhinal cortex has also been observed [54]. Monkeys were presented with 24 colored patterns, and perirhinal neurons initially responded selectively to one or two of the patterns. After training in which the monkeys learned to associate pairs of stimuli, the stimulus-selective neurons began to fire not only in response to the preferred stimulus but also in response to its paired associate. Miyashita [55] suggested that these pair-coding neurons support “pair recall” activity in which presentation of one of the stimuli calls to mind its paired associate. Recent neuroimaging studies in humans have also found evidence of recollection-related activity (associated with “Remember” judgments) for visual objects in perirhinal cortex [56, 57] (see Box 1 for a discussion of efforts to interpret recollection-related perirhinal activity in terms of “unitized familiarity”).

In the monkey, the perirhinal cortex also receives substantial input from polymodal areas (Figure 2), in particular from area TF of the parahippocampal cortex (which itself receives visuospatial input from the dorsal “where” pathway). These connections raise the possibility that perirhinal cortex plays a role in processing both visual and spatial attributes of memory. In support of this idea, Yanike et al. [58] recorded neuronal activity as monkeys learned scene-location associations. After viewing a complex visual scene, monkeys fixated one of four screen locations to receive a reward, and their learning of the scene-location association improved with training. This associative learning task cannot be solved on the basis of scene familiarity alone and instead requires calling to mind the correct spatial location, a process more akin to recollection than familiarity. Perirhinal neurons signaled newly learned associations by changing their firing rate in association with behavioral learning (similar to earlier findings in the same task for hippocampal neurons) [59].

As in the monkey, rat perirhinal cortex receives visual input, but it also receives strong input from other sensory modalities, including olfactory and auditory input [60]. In addition, input from postrhinal cortex (the rodent homolog of primate parahippocampal cortex and a possible source of spatial information) is weak [60]. These considerations suggest that pair-coding neurons might be found in rat perirhinal cortex that support non-spatial, cross-modal “pair recall” activity. For example, following training in which olfactory stimuli and visual stimuli were cross-modally paired, one might find cross-modal pair-coding neurons such that a perirhinal neuron that initially responded preferentially to a particular odor stimulus would now also respond to its visual paired associate. Although this possibility has not yet been tested, such a finding would provide further evidence that perirhinal neurons play a role in recollection (i.e., the calling to mind of stimuli that have not themselves been presented) and might help to confirm that rats are actually capable of recollection. In addition, such a finding would lend support to the idea, based on neuroanatomy, that rat perirhinal cortex is involved in processing both visual and olfactory attributes of memory.

Hippocampus

In the hierarchy of information processing in the MTL, the hippocampus is the ultimate recipient of convergent projections from perirhinal cortex, parahippocampal cortex and entorhinal cortex (Figure 2). Thus, the hippocampus receives and combines input from multiple sources and is in a position to be involved in all aspects of declarative memory. One striking aspect of single-unit recording data is that hippocampal neurons appear to code nearly every relevant aspect of an experience [61–63]. In addition, hippocampal neurons can yield an abstract match/nonmatch signal [35, 36, 64], they can signal recall of a specific event [65], and they can signal item familiarity in the same way that perirhinal neurons do (repetition suppression). Repetition suppression was not initially detected in the hippocampus [9], and that fact contributed to the notion that the hippocampus plays no role in familiarity. However, in two more recent studies, neural activity in hippocampus [59] and perirhinal cortex [58] was recorded while monkeys were repeatedly exposed to complex novel scenes (with no response required). A similar proportion of neurons in perirhinal cortex and hippocampus initially exhibited elevated firing that subsequently decreased to baseline as each scene became more familiar over the course of approximately 15 presentations. One reason why this familiarity effect was observed in the hippocampus in this study may be that the stimuli were sufficiently complex to require the processing of multiple stimulus attributes (such as the spatial relationship between different aspects of a visual scene).

Indeed, instead of singling out recollection, the function that distinguishes the hippocampus from the other structures of the MTL may be its ability to combine the wide variety of attributes associated with a particular experience to form an integrated memory trace. Furthermore, it seems reasonable to suppose that a well-formed, multi-attribute memory trace would facilitate not only recollection-based memory but also familiarity-based memory. For example, studies in rats found that, when passively viewed, novel visual objects selectively increased c-Fos levels in perirhinal cortex, whereas novel arrangements of a set of familiar objects selectively increased c-Fos levels in the hippocampus [66, 67]. These findings suggest that, although the hippocampus may not always play a role in recognizing a simple visual object as familiar (perhaps when the object is passively viewed and processed solely in terms of visual information), it nonetheless plays a role in recognizing as familiar a complex, multi-element stimulus (e.g., one that has several parts). To relate this finding to human experience, consider the spatial layout of furniture in a familiar room. If the furniture were rearranged, the familiarity of the room might be markedly altered even if the original arrangement of the furniture could not be called to mind (i.e., even if the original arrangement could not be recollected).

The idea that the hippocampus plays an integrative role in the encoding of complex stimuli is not new, but its integrative function has often been equated with the further idea that it plays a selective role in recollection. In our view, this has created confusion as well as the appearance of more disagreement than actually exists. The perspective outlined above is compatible with ideas proposed by others (e.g., [11, 68, 69]) up to the point where those ideas lead to the suggestion that the hippocampus plays no role in familiarity. Our alternative proposal is that the integrative role of the hippocampus supports recollection as well as familiarity, particularly when the familiar stimulus is encoded in terms of multiple attributes (e.g., visual, spatial, temporal, tactile, emotional, etc.).

A different line of research that has often been interpreted to mean that the hippocampus plays no role in familiarity uses the Novel Object Recognition (NOR) procedure. In a typical NOR task, two identical objects are presented (A and A), and later one old object and one new object are presented (A and B). Increased exploration of the new object (B) is taken as an indication that the old object is recognized as familiar. Although studies using humans and monkeys have consistently found that damage limited to the hippocampus impairs performance on this task [70–73], lesion studies in rats have often reported no effect (e.g., [74]) -- as if the hippocampus plays no role in the familiarity of a visual object. By contrast, perirhinal lesions in rats typically produce a deficit [52, 74]. Interestingly, when a version of the NOR task is used where spatial memory is relevant, hippocampal lesions reliably impair performance [75]. This pattern of results has been interpreted to mean that the perirhinal cortex supports recognition for individual items (perhaps based on familiarity), but that the hippocampus supports recognition of items in context (perhaps based on recollection).

An alternative interpretation is that intact rats – more so than primates – attempt to encode objects with respect to spatial attributes even when spatial memory is not required (e.g., [76]). Thus, for the NOR task, the rat might encode the two objects presented in the study phase as A-1 (i.e., item A in position 1) and A-2 (item A in position 2). Because the new item (e.g., B-2) shares positional information with a previously encountered object (A-2), the new item might not seem as novel as it would if spatial information had not been acquired. In line with this idea, a recent study [77] found that temporary inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus in mice immediately after learning unexpectedly enhanced NOR performance 24 hours later. This result suggests that the availability of spatial information, which is normally acquired when the hippocampus is functional, can interfere with the detection of a novel object. Accordingly, in the absence of the hippocampus, rats might acquire visual information about the objects more efficiently than intact rats. If so, one way to reduce spatial processing would be to expose the mice to the testing environment for a period of time before testing. Indeed, after increased exposure to the experimental apparatus prior to NOR testing (5 min/day for 5 days), post-training inactivation of the dorsal hippocampus no longer affected object recognition memory [77].

One possibility, not tested in the study [77], is that after even more extended pre-exposure to the experimental apparatus, hippocampal inactivation might impair performance. An impairment might be found if – instead of acquiring spatial information while objects are presented – the animal now encoded multiattribute features of the objects themselves (e.g., visual and tactile information about the objects). A stimulus defined by multiple object-specific attributes should seem more familiar when later encountered than it would if only the visual aspects of the object had been encoded. Under those conditions, hippocampal lesions in rats would be expected to impair performance on the NOR task, a result that has been reported for both pre- and post-training hippocampal lesions [78]. In any case, the key point is that results from the NOR task, which are often interpreted to mean that the hippocampus plays no role in object familiarity, may instead indicate that the hippocampus encodes multiple attributes of an experience (including, in the case of rats and mice, spatial attributes).

The preceding considerations suggest that it may be possible to find memory-related tasks that do not involve the hippocampus, but they would not be tasks that are based on familiarity. Instead, they would be tasks that encourage the encoding of a single attribute (e.g., visual information) without encouraging the encoding of other attributes (e.g., spatial, tactile, olfactory, temporal, emotional, etc.). For example, as indicated earlier, several studies [66, 67] found no c-Fos activity in the hippocampus when rats passively viewed simple objects through a viewing window (a procedure that should minimize the spatial and tactile information that might otherwise have been processed). In effect, by encouraging the selective encoding of simple visual object information, the passive-viewing task may have accomplished what hippocampal lesions accomplish in circumstances when the animal is able to explore the stimulus.

In humans, virtually all stimuli are likely processed in terms of multiple attributes and in a way that engages the hippocampus. Even a simple list of words presented for study on a computer screen should involve the visual analysis of the letters as well as auditory verbal processing as the words are silently read. Such multi-attribute encoding, by engaging the hippocampus, would facilitate the later memory of the words – and this would be true whether memory were based on recollection or familiarity. However, if a task could be found that encouraged humans to encode stimuli in terms of a single attribute (such as their visual attribute), then hippocampal lesions might not impair memory performance because the task can be accomplished by perirhinal cortex.

Previous studies that can be construed as tests of memory for single-attribute stimuli have usually found deficits associated with hippocampal lesions. For example, hippocampal patients were impaired at recognition memory for a previously presented list of synthetic sounds (tones, harmonies, gurgling sounds, chimes, etc.) [79]. Similarly, hippocampal patients were impaired at recognition memory for a previously presented list of common odors (e.g., garlic powder, almond extract, shoe polish) [80]. Perhaps some of these stimuli could have been encoded by controls in terms of multiple attributes (e.g., using a verbal strategy), which might have engaged hippocampal processing.

A different task that may provide a purer test of single attribute processing is face memory. Recent evidence suggests that hippocampal lesions do not impair face memory, at least at short retention intervals [81]. It seems possible that no verbal processing or associative processing accompanies the presentation of each face. Still, processing of a temporal attribute might be expected during encoding (facilitating the later knowledge that the faces were not merely seen before but seen recently), and such processing might be expected to engage the hippocampus. Memory for faces warrants further investigation. If face memory is indeed intact and if our view is correct, it may be possible to find other single-attribute memory tasks that can be accomplished by patients with lesions limited to the hippocampus.

Concluding remarks

A large body of prior research concerned with recollection and familiarity in the MTL – much of which has been interpreted to mean that the hippocampus plays a selective role in recollection – involves a strength confound (comparing strong recollection to weak familiarity). When steps are taken to compare recollection and familiarity after they are equated for (high) strength, both a recollection and a familiarity signal are evident in the hippocampus.

This perspective should not be taken to mean that “memory strength” is the theoretical principle underlying the functional organization of the MTL. Memory strength is simply the methodological confound that has complicated the interpretation of prior research on this issue. The point instead is that an investigative approach grounded in neuroanatomy and neurophysiology is more likely to shed light on the functional anatomical organization of the MTL than an approach grounded in the psychological distinction between recollection and familiarity.

Neuroanatomical considerations suggest that the hippocampus – more so than the other structures of the MTL – is involved in combining multiple stimulus attributes. Perirhinal cortex may combine multiple attributes as well, but to a lesser extent. In nonhuman primates, for example, perirhinal cortex may be able to combine both visual and spatial attributes, but the hippocampus may be needed to elaborate the trace with other attributes (e.g., auditory, tactile, temporal, etc.). In rats, perirhinal cortex is also polymodal (receiving visual, auditory and olfactory input) but this cortex receives little spatial input. Thus, in the rat, the hippocampus may be essential for elaborating a memory trace with a spatial attribute. However, in rodents, monkeys, as well as in humans, the hippocampus is needed for encoding multiple attributes of an experience, thereby facilitating the later recollection-based and familiarity-based memory of multi-attribute stimuli.

Box 1 Continuous recollection vs. Unitized familiarity in Associative Recognition.

In a typical associative recognition test, participants are asked to distinguish between intact and rearranged item pairs (e.g., word pairs). Because the familiarity of the items does not help to make this discrimination, associative recognition is thought to depend on recollection. Recently, using fMRI, Haskins et al. [18] reported that perirhinal activity was elevated for correct associative recognition decisions, consistent with other fMRI research [82] and with single-unit evidence in monkeys showing activity in perirhinal neurons correlated with associative memory [83]. This evidence would seem to suggest that perirhinal cortex plays a role in recollection (not just familiarity). However, in an effort to preserve the idea that perirhinal cortex is involved in familiarity (and not in recollection), Haskins et al. [18] proposed that the perirhinal cortex supports “unitized familiarity.” The concept of unitized familiarity was justified by ROC evidence, and it is important to consider the reasoning that led to this proposal.

Whereas the ROCs observed in item recognition tests are typically curvilinear, early investigations of associative recognition and source memory found nearly linear ROCs [84, 85]. The linear ROCs initially obtained in these recollection-based tests (tests of associative recognition and source memory) appeared consistent with the idea that recollection is a dichotomous process (i.e. that recollection yields only strong memories). This characteristic of recollection is a key feature of a prominent model of recognition memory [15]. However, many later studies showed that associative recognition and source memory ROCs are almost always curvilinear [29]. A curvilinear ROC obtained from a recollection-based test is consistent with a continuous recollection process, graded in strength, not a discontinuous process as required by the model. Nonetheless, an alternative explanation of curvilinear ROCs in these tests – one that does not require relinquishing the idea that recollection is a dichotomous process and that does not require abandoning the model – invokes the concept of“unitized familiarity.” According to this idea, the two items of a word pair (or an item and its source) can be combined into a singular memory trace that yields a continuous familiarity signal and a curvilinear ROC.

Two recent studies directly tested the unitized familiarity interpretation of curvilinear ROCs by combining source [37] or associative recognition [86] ROC analysis with the Remember/Know procedure. Both studies found unambiguously curvilinear ROCs. Importantly, these were mainly associated with Remember judgments (as predicted by a continuous recollection account), not by Know judgments (as predicted by a unitized familiarity account). In addition, confidence in the associative recognition decisions was correlated in continuous fashion with the accuracy of subsequent cued recall [a direct test of recollection, 86]. These results argue against the effort to reconceptualize evidence of associative recollection in terms of unitized familiarity. The point is not that unitized familiarity does not exist (e.g., people do sometimes make high-confidence Know judgments for associative recognition decisions). Instead, the point is that curvilinear ROCs do not provide evidence for unitized familiarity, and elevated perirhinal activity in association with correct associative memory decisions [18] is probably best understood as evidence for recollection (see also [57] and [56]).

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Medical Research Service of the Department of Veterans Affairs and NIMH Grants 24600 and 082892. We thank Wendy Suziki for her comments on an earlier version of this article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Milner B. Disorders of learning and memory after temporal lobe lesions in man. Clin. Neurosurg. 1972;19:421–446. doi: 10.1093/neurosurgery/19.cn_suppl_1.421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scoville WB, Milner B. Loss of recent memory after bilateral hippocampal lesions. Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery and Psychiatry. 1957;20:11–21. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.20.1.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Squire LR. The legacy of patient H.M. for neuroscience. Neuron. 2009;61:6–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Squire LR, Wixted JT. The cognitive neuroscience of human memory since H.M. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2011 doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mishkin M. A memory system in the monkey. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. B-Biol. Sci. 1982;298:85–95. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1982.0074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Squire LR, Zola-Morgan S. The medial temporal-lobe memory system. Science. 1991;253:1380–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1896849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Atkinson RC, Juola JF. Search and decision processes in recognition memory. In: Krantz DH, Atkinson RC, Suppes P, editors. Contemporary developments in mathematical psychology. Freeman; San Francisco: 1974. pp. 243–290. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandler G. Recognizing - the judgment of previous occurrence. Psychol. Rev. 1980;87:252–271. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MW, Aggleton JP. Recognition memory: What are the roles of the perirhinal cortex and hippocampus? Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2001;2:51–61. doi: 10.1038/35049064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Diana RA, et al. Imaging recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe: A three-component model. Trends Cogn. Sci. 2007;11:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ranganath C. A unified framework for the functional organization of the medial temporal lobes and the phenomenology of episodic memory. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1263–1290. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yonelinas AP, et al. Effects of extensive temporal lobe damage or mild hypoxia on recollection and familiarity. Nat. Neurosci. 2002;5:1236–1241. doi: 10.1038/nn961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eichenbaum H, et al. The medial temporal lobe and recognition memory. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;30:123–152. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.30.051606.094328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daselaar SM, et al. Triple dissociation in the medial temporal lobes: Recollection, familiarity and novelty. Journal of Neurophysiology. 2006;96:1902–1911. doi: 10.1152/jn.01029.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yonelinas AP. Receiver-operating characteristics in recognition memory - evidence for a dual-process model. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1994;20:1341–1354. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.20.6.1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yonelinas AP, et al. Recollection and familiarity: Examining controversial assumptions and new directions. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1178–1194. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilboa A, et al. Hippocampal contributions to recollection in retrograde and anterograde amnesia. Hippocampus. 2006;16:966–980. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haskins AL, et al. Perirhinal cortex supports encoding and familiarity-based recognition of novel associations. Neuron. 2008;59:554–560. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vann SD, et al. Impaired recollection but spared familiarity in patients with extended hippocampal system damage revealed by 3 convergent methods. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:5442–5447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812097106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bowles B, et al. Double dissociation of selective recollection and familiarity impairments following two different surgical treatments for temporal-lobe epilepsy. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:2640–2647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCormick C, et al. Hippocampal-neocortical networks differ during encoding and retrieval of relational memory: Functional and effective connectivity analyses. Neuropsychologia. 2010;48:3272–3281. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2010.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohn M, et al. Recollection versus strength as the primary determinant of hippocampal engagement at retrieval. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009;106:22451–22455. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0908651106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dunn JC. Remember-know: A matter of confidence. Psychol. Rev. 2004;111:524–542. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.111.2.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dunn JC. The dimensionality of the remember-know task: A state-trace analysis. Psychol. Rev. 2008;115:426–446. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.115.2.426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wixted JT, Stretch V. In defense of the signal detection interpretation of remember/know judgments. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 2004;11:616–641. doi: 10.3758/bf03196616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Slotnick SD, Dodson CS. Support for a continuous (single-process) model of recognition memory and source memory. Mem. Cogn. 2005;33:151–170. doi: 10.3758/bf03195305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wais PE, et al. In search of recollection and familiarity signals in the hippocampus. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010;22:109–123. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bowles B, et al. Impaired familiarity with preserved recollection after anterior temporal-lobe resection that spares the hippocampus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:16382–16387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705273104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wixted JT. Dual-process theory and signal-detection theory of recognition memory. Psychol. Rev. 2007;114:152–176. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mickes L, et al. Recollection is a continuous process: Implications for dual-process theories of recognition memory. Psychol. Sci. 2009;20:509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wais PE, et al. Remember/know judgments probe degrees of recollection. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2008;20:400–405. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johnson JD, et al. Recollection, familiarity and cortical reinstatement: A multivoxel pattern analysis. Neuron. 2009;63:697–708. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kurilla BP, Westerman DL. Source memory for unidentified stimuli. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2010;36:398–410. doi: 10.1037/a0018279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Onyper SV, et al. Some-or-none recollection: Evidence from item and source memory. J. Exp. Psychol.-Gen. 2010;139:341–364. doi: 10.1037/a0018926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rutishauser U, et al. Activity of human hippocampal and amygdala neurons during retrieval of declarative memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:329–334. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706015105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rutishauser U, et al. Single-trial learning of novel stimuli by individual neurons of the human hippocampus-amygdala complex. Neuron. 2006;49:805–813. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slotnick SD. Oremembero source memory rocs indicate recollection is a continuous process. Memory. 2010;18:27–39. doi: 10.1080/09658210903390061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Starns JJ, Ratcliff R. Two dimensions are not better than one: Streak and the univariate signal detection model of remember/know performance. J. Mem. Lang. 2008;59:169–182. doi: 10.1016/j.jml.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wixted JT, Mickes L. A continuous dual-process model of remember/know judgments. Psychol. Rev. 2010;117:1025–1054. doi: 10.1037/a0020874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cansino S, et al. Brain activity underlying encoding and retrieval of source memory. Cereb. Cortex. 2002;12:1048–1056. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.10.1048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Davachi L, et al. Multiple routes to memory: Distinct medial temporal lobe processes build item and source memories. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2003;100:2157–2162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0337195100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kensinger EA, Schacter DL. Amygdala activity is associated with the successful encoding of item, but not source, information for positive and negative stimuli. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:2564–2570. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5241-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ranganath C, et al. Dissociable correlates of recollection and familiarity within the medial temporal lobes. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2003.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross RS, Slotnick SD. The hippocampus is preferentially associated with memory for spatial context. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2008;20:432–446. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2008.20035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weis S, et al. Process dissociation between contextual retrieval and item recognition. Neuroreport. 2004;15:2729–2733. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kirwan CB, et al. Activity in the medial temporal lobe predicts memory strength, whereas activity in the prefrontal cortex predicts recollection. J. Neurosci. 2008;28:10541–10548. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3456-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wais PE, et al. The hippocampus supports both the recollection and the familiarity components of recognition memory. Neuron. 2006;49:459–466. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kirwan CB, et al. A demonstration that the hippocampus supports both recollection and familiarity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010;107:344–348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912543107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wixted JT, Squire LR. The role of the human hippocampus in familiarity-based and recollection-based recognition memory. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;215:197–208. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2010.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wixted JT, et al. Measuring recollection and familiarity in the medial temporal lobe. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1195–1205. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Suzuki WA, Amaral DG. Perirhinal and parahippocampal cortices of the macaque monkey - cortical afferents. Journal of Comparative Neurology. 1994;350:497–533. doi: 10.1002/cne.903500402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Winters BD, et al. Object recognition memory: Neurobiological mechanisms of encoding, consolidation and retrieval. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews. 2008;32:1055–1070. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Cowell RA, et al. Components of recognition memory: Dissociable cognitive processes or just differences in representational complexity? Hippocampus. 2010;20:1245–1262. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sakai K, Miyashita Y. Neural organization for the long-term-memory of paired associates. Nature. 1991;354:152–155. doi: 10.1038/354152a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyashita Y. Cognitive memory: Cellular and network machineries and their top-down control. Science. 2004;306:435–440. doi: 10.1126/science.1101864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Carr VA, et al. Neural activity in the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex during encoding is associated with the durability of episodic memory. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 2010;22:2652–2662. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Staresina BP, Davachi L. Differential encoding mechanisms for subsequent associative recognition and free recall. J. Neurosci. 2006;26:9162–9172. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2877-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yanike M, et al. Comparison of associative learning-related signals in the macaque perirhinal cortex and hippocampus. Cereb. Cortex. 2009;19:1064–1078. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhn156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wirth S, et al. Single neurons in the monkey hippocampus and learning of new associations. Science. 2003;300:1578–1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1084324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Furtak SC, et al. Functional neuroanatomy of the parahippocampal region in the rat: The perirhinal and postrhinal cortices. Hippocampus. 2007;17:709–722. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Eichenbaum H, et al. The hippocampus, memory and place cells: Is it spatial memory or a memory space? Neuron. 1999;23:209–226. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80773-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wood ER, et al. The global record of memory in hippocampal neuronal activity. Nature. 1999;397:613–616. doi: 10.1038/17605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.DeVito LM, Eichenbaum H. Distinct contributions of the hippocampus and medial prefrontal cortex to the “what-where-when” components of episodic-like memory in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2010;215:318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Squire LR, et al. Recognition memory and the medial temporal lobe: A new perspective. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:872–883. doi: 10.1038/nrn2154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gelbard-Sagiv H, et al. Internally generated reactivation of single neurons in human hippocampus during free recall. Science. 2008;322:96–101. doi: 10.1126/science.1164685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Jenkins TA, et al. Novel spatial arrangements of familiar visual stimuli promote activity in the rat hippocampal formation but not the parahippocampal cortices: A c-fos expression study. Neuroscience. 2004;124:43–52. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2003.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wan HM, et al. Different contributions of the hippocampus and perirhinal cortex to recognition memory. J. Neurosci. 1999;19:1142–1148. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-03-01142.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brown MW, et al. Recognition memory: Material, processes and substrates. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1228–1244. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Montaldi D, Mayes AR. The role of recollection and familiarity in the functional differentiation of the medial temporal lobes. Hippocampus. 2010;20:1291–1314. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.McKee RD, Squire LR. On the development of declarative memory. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1993;19:397–404. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.19.2.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pascalis O, et al. Visual paired comparison performance is impaired in a patient with selective hippocampal lesions and relatively intact item recognition. Neuropsychologia. 2004;42:1293–1300. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zola SM, et al. Impaired recognition memory in monkeys after damage limited to the hippocampal region. J. Neurosci. 2000;20:451–463. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-01-00451.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nemanic S, et al. The hippocampal/parahippocampal regions and recognition memory: Insights from visual paired comparison versus object-delayed nonmatching in monkeys. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:2013–2026. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3763-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Winters BD, et al. Double dissociation between the effects of peri-postrhinal cortex and hippocampal lesions on tests of object recognition and spatial memory: Heterogeneity of function within the temporal lobe. J. Neurosci. 2004;24:5901–5908. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1346-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Good MA, et al. Context- but not familiarity-dependent forms of object recognition are impaired following excitotoxic hippocampal lesions in rats. Behav. Neurosci. 2007;121:218–223. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Manns JR, Eichenbaum H. A cognitive map for object memory in the hippocampus. Learn. Mem. 2009;16:616–624. doi: 10.1101/lm.1484509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Oliveira AMM, et al. Post-training reversible inactivation of the hippocampus enhances novel object recognition memory. Learn. Mem. 2010;17:155–160. doi: 10.1101/lm.1625310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Broadbent NJ, et al. Object recognition memory and the rodent hippocampus. Learn. Mem. 2010;17:794–800. doi: 10.1101/lm.1650110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Squire LR, et al. Impaired auditory recognition memory in amnesic patients with medial temporal lobe lesions. Learn. Mem. 2001;8:252–256. doi: 10.1101/lm.42001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Levy DA, et al. Impaired odor recognition memory in patients with hippocampal lesions. Learn. Mem. 2004;11:794–796. doi: 10.1101/lm.82504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bird CM, Burgess N. The hippocampus supports recognition memory for familiar words but not unfamiliar faces. Current Biology. 2008;18:1932–1936. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Law JR, et al. Functional magnetic resonance imaging activity during the gradual acquisition and expression of paired-associate memory. J. Neurosci. 2005;25:5720–5729. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4935-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Naya Y, et al. Forward processing of long-term associative memory in monkey inferotemporal cortex. J. Neurosci. 2003;23:2861–2871. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-07-02861.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yonelinas AP. Recognition memory rocs for item and associative information: The contribution of recollection and familiarity. Mem. Cogn. 1997;25:747–763. doi: 10.3758/bf03211318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yonelinas AP. The contribution of recollection and familiarity to recognition and source-memory judgments: A formal dual-process model and an analysis of receiver operating characteristics. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 1999;25:1415–1434. doi: 10.1037//0278-7393.25.6.1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mickes L, et al. Continuous recollection versus unitized familiarity in associative recognition. J. Exp. Psychol.-Learn. Mem. Cogn. 2010;36:843–863. doi: 10.1037/a0019755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Buffalo EA, et al. Distinct roles for medial temporal lobe structures in memory for objects and their locations. Learn. Mem. 2006;13:638–643. doi: 10.1101/lm.251906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]