Abstract

Objectives

Genetic variations or polymorphisms within genes of the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway alter DNA repair capacity. Reduced DNA repair (NER) capacity may result in tumors that are more susceptible to cisplatin chemotherapy, which functions by causing DNA damage. We investigated the potential predictive significance of functional NER single nucleotide polymorphisms in esophageal cancer patients treated with (n = 262) or without (n = 108) cisplatin.

Methods

Four NER polymorphisms XPD Asp312Asn; XPD Lys751Gln, ERCC1 8092C/A, and ERCC1 codon 118C/T were each assessed in polymorphism–cisplatin treatment interactions for overall survival (OS), with progression-free survival (PFS) as a secondary endpoint.

Results

No associations with ERCC1 118 were found. Polymorphism–cisplatin interactions were highly significant in both OS (P = 0.002, P = 0.0001, and P < 0.0001) and PFS (P = 0.006, P = 0.008, and P = 0.0007) for XPD 312, XPD 751, and ERCC1 8092, respectively. In cisplatin-treated patients, variant alleles of XPD 312, XPD 751, and ERCC1 8092 were each associated with significantly improved OS (and PFS): adjusted hazard ratios of homozygous variants versus wild-type ranged from 0.22 [95% confidence interval (CI): 0.1–0.5] to 0.31 (95% CI: 0.1–0.7). In contrast, in patients who did not receive cisplatin, variant alleles of XPD 751 and ERCC1 8092 had significantly worse survival, with adjusted hazard ratios of homozygous variants ranging from 2.47 (95% CI: 1.1–5.5) to 3.73 (95% CI: 1.6–8.7). Haplotype analyses affirmed these results.

Conclusion

DNA repair polymorphisms are associated with OS and PFS, and if validated may predict for benefit from cisplatin therapy in patients with esophageal cancer.

Keywords: DNA repair, esophageal cancer, genetic polymorphisms

Introduction

The incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is rising at a rate exceeding that of most other solid malignancies [1]. Despite rising incidence and poor prognosis, new treatment strategies are slow to emerge, and the most appropriate curative multimodality approach remains controversial [2–5]. The identification of predictive pharmacogenetic markers may tailor treatment selection and improve outcome.

Multimodality regimens in esophageal cancer commonly include cisplatin-based chemotherapy [5]. DNA adducts including those induced by cisplatin are repaired by the nucleotide excision repair (NER) pathway [6–9]. NER capacity is, therefore, important to the efficacy of cisplatin, and suboptimal NER capacity may render esophageal cancers more sensitive to cisplatin treatment.

Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) within NER genes may alter DNA repair capacity [10–16]. In preclinical studies, the variant alleles of the Xeroderma pigmentosum group D-complementing gene (XPD) polymorphisms XPD Asp312Asn (rs1799793) and XPD Lys751Gln (rs13181) are associated with decreased lymphocyte mRNA levels compared with the more common, wild-type allele [14]. Excision repair cross-complementing 1 (ERCC1) codon 118C/T (rs11615) is associated with cisplatin sensitivity in ovarian cancer cell lines [15], and ERCC1 8092C/A (rs3212986) may be associated with altered mRNA stability [16].

Several studies have found a correlation between these putatively functional SNPs and clinical outcome in cisplatin-treated patients, although results have been inconsistent [17–24]. In a study of patients with advanced squamous cancer of the head and neck treated with cisplatin regimens, the variant alleles of XPD Asp312Asn and XPD Lys751Gln were associated with an improved overall survival (OS) [21]. It was hypothesized that reduced DNA repair associated with the variant genotype provided a therapeutic advantage from cisplatin chemotherapy. Furthermore, a study evaluating a range of NER SNPs in 149 patients with cisplatin-treated esophageal cancer, found a trend for improved outcome associated with a reduced number of wild-type NER SNPs [22]. Neither study evaluated the impact of the NER SNPs in non-cisplatin-treated patients to explore the potential predictive versus prognostic implications of NER genotype. We hypothesized that four NER polymorphisms, XPD Asp312Asn; XPD Lys751Gln, ERCC1 8092C/A, and ERCC1 codon 118C/T, are independent pharmacogenetic predictors of cisplatin therapy in esophageal cancer patients, which we evaluated in cisplatin and non-cisplatin-treated patients.

Materials and methods

Patient selection

The study was approved by the institutional review boards of Massachusetts General Hospital, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Harvard School of Public Health (all Boston, Massachusetts, USA) and Princess Margaret Hospital, (Toronto, Ontario, Canada). Methods are in accordance with REMARK recommendations [25]. Complete methodological details are attached as an appendix (Appendix 1). Patients with histologically confirmed esophageal (and gastro-esophageal junction) cancer were recruited as part of a prospective molecular outcomes study from November 1999, at Massachusetts General Hospital, and from January 2004, at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Demographic, patient characteristics, and blood samples for genotyping were collected at the time of study entry, and outcome variables were collected prospectively, full details of which have been described [26]. To enable adequate follow-up, only patients recruited up to October 2004 were included in this analysis. A total of 404 patients were recruited, representing a participation rate of 93% from the two institutions, of which 34 were excluded for the following reasons: blood samples not collected (n = 6); significant clinical data missing (n = 23); and genotype data lacking because of technical issues (n = 5). Patients were classified into the ‘Cisplatin-treated’ group (n = 262), if they received cisplatin as part of first-line therapy. First-line therapy was considered such even if multiple sequential therapies were administered, as long as the sequence was planned at the outset of treatment. Patients who did not receive first-line cisplatin were considered to be in the ‘No-cisplatin’ group for analysis (n = 108).

Outcome endpoints

The primary endpoints were OS, measured from the date of histologic confirmation of diagnosis to either the date of death (event) or last known to be alive (censored), and progression-free survival (PFS), measured from the date of histological diagnosis to documented recurrence/progression (event), or date last assessed clinically, radiologically, or pathologically to have lack of recurrence/progression.

Polymorphism selection, DNA extraction and genotyping

The four NER SNPs, XPD Asp312Asn, rs1799793; XPD Lys751Gln, rs13181; ERCC1 8092C/A, rs3212986; and ERCC1 codon 118C/T, rs11615, were selected based on the following criteria:

Associated with altered DNA repair capacity and/or clinical evidence of a prognostic or predictive impact in other cisplatin-treated malignancies.

High frequency within the Caucasian population.

DNA was extracted from whole blood using the Puregene DNA Isolation Kit (Gentra Systems, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA). Polymorphisms were genotyped using the TaqMan assay [384-well ABI 7900HT; Applied Biosystems Inc. (ABI), Foster City, California, USA]. Primers, probe sequences, and genotyping conditions were obtained from Primer Express Software (ABI), and are available on request.

Statistical methods

General approach

Demographic, clinical, and polymorphism data were compared using Fisher’s exact and student t-tests. Primary analyses involved Cox proportional hazard (CPH) models that were adjusted for age, sex, stage, performance status (PS), and treatment with cisplatin. Adjustment for ethnicity, anatomic sublocation, and histology were initially included, but each fell out of the backward selection analysis of clinical variables. For each series of CPH models, we evaluated two different models of genetic inheritance: an additive (primary) model that assumes each variant allele dose adds an incremental effect on clinical outcome (which uses a single term to reflect the effect of an allele on outcome); and a codominant (secondary) model that did not assume a dose effect (where separate terms compared homozygous and heterozygous genotypes separately with the wild-type genotype). Associations between genotype and outcome were also estimated using the method of Kaplan–Meier to generate survival curves (with log-rank tests), separately for cisplatin and non-cisplatin-treated patients. All statistical testing was conducted at the 0.05 level using SAS software Version 8.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina, USA). By convention, the T allele of ERCC1 codon 118C/T has the greater allele frequency; therefore, this allele was treated as wild-type in analyses.

A useful biomarker predicts different outcomes for treated and non-treated patients, which statistically, can be tested through a biomarker–treatment interaction on outcome. The primary analysis was a polymorphism–cisplatin treatment interaction analysis of OS using CPH models for each of the four NER polymorphisms, assuming an additive model of inheritance. Secondary analyses considered codominant models of inheritance.

Bonferroni’s correction was used in the primary analyses to correct 24 analyses (assessment of the association between each of the four SNPs and OS, PFS, and interaction analysis using an additive and codominant model), this yields a corrected P value of 0.002. This is an extremely conservative correction given that the outcomes of the SNPs are not fully independent variables.

Exploratory analyses

To better understand the nature of interactions, subgroup analyses for the cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin cohorts were explored separately. In addition, differential associations by treatment (cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin) were studied in subgroups defined by clinical criteria, including age (older; or younger than median age), sex, histologic subtype (adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma), PS (Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group 0–1; ≥2), and anatomic sublocation of primary tumor (gastro-esophageal junction and distal esophagus). We explored polymorphism–outcome relationships in patients treated with cisplatin-based trimodality therapy (the predominant treatment within the cisplatin-treated cohort), and in patients treated with surgery alone (the predominant treatment within the no-cisplatin cohort).

Exploratory haplotype analyses were performed to assess the combined effect of all four NER polymorphisms, which are in linkage disequilibrium (Lewontin D′ for XPD Lys751Gln–XPD Asp312Asn–ERCC1 8092C/A–ERCC1 Codon 118C/T were 0.73–0.44–0.84). The haplotype frequencies were estimated using PHASE (Bayesian approach) [27]. CPH models were applied to haplotype trend regression analyses using the estimated haplotype frequencies [28]. Both the omnibus association test and haplotype-specific association tests were performed [29,30]. Interaction and subgroup analyses were performed on haplotypes for OS and PFS, analogous to the primary analysis.

Results

Population characteristics

Median follow-up times were 33 (OS) and 31 (PFS) months for the entire 370 patient population. During follow-up, there were 241 relapses and 216 deaths. Median OS was 30 months (53 months – node-negative disease; 28 months – node-positive disease; 14 months – metastatic disease), and median PFS was 16 months (42 months – node-negative disease; 16 months – node-positive disease; 8 months – metastatic disease).

Separate patient characteristics for the cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin cohorts patients are summarized in Table 1. No-cisplatin-treated patients were older (P = 0.0002, t-test) and had significantly less nodal disease (P < 0.0001) than cisplatin-treated patients. No differences in sex, ethnicity, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group PS, histological subtype, and tumor site were found. OS and PFS were similar between cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin groups (Table 1). There were no significant associations between each polymorphism and any of the clinical factors in Table 1 (P > 0.10 for each comparison).

Table 1.

Patient and treatment characteristics, for cisplatin-treated patients (‘Cisplatin-treated’) and patients not treated with cisplatin (‘No-cisplatin’)

| All patients |

P value (by Fisher’s exact test unless otherwise specified) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Cisplatin-treated (n = 262) |

No-cisplatin (n = 108) |

|

| Median age (range) (years) |

62 (21–91) | 69 (32–91) | 0.0002 (t-test) |

| Sex (%) | |||

| Male | 87 | 82 | 0.20 |

| Female | 13 | 18 | |

| Ethnicity (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 97 | 97 | 0.67 |

| Other | 3 | 3 | |

| ECOG performance status (%) | |||

| 0–1 | 84 | 91 | 0.28 |

| 2 | 13 | 7 | |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | |

| Stagea,b (%) | |||

| Early | 21 | 46 | <0.0001 |

| Locally advanced | 60 | 32 | |

| Metastatic | 18 | 19 | |

| Histological subtypes (%) | |||

| Adenocarcinoma | 80 | 83 | 0.51 |

| Squamous arcinoma | 18 | 14 | |

| Poorly differentiated carcinoma | 2 | 3 | |

| Tumor site (%) | |||

| Gastro-esophageal junction | 23 | 33 | 0.33 |

| Distal thoracic | 63 | 58 | |

| Mid thoracic | 8 | 5 | |

| Proximal/cervical | 6 | 4 | |

| Treatmenta (%) | |||

| Surgery alone | 0 | 59 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemoradiation | 70 | 8 | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | 2 | 1 | |

| Adjuvant chemoradiation or chemotherapy | 7 | 4 | <0.0001 |

| Definitive chemoradiation | 12 | 7 | |

| Chemotherapy alone | 10 | 9 | |

| PDT, radiation only | 0 | 8 | |

| No or refused treatment | 0 | 4 | |

| OS (months) | 28 | 33 | HR 0.95 (95% CI: 0.7–1.3)c |

| PFS (months) | 16 | 17 | HR 0.94 (95% CI: 0.7–1.2)c |

CI, confidence interval; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; HR, hazard ratio; OS, overall survival; PDT, photodynamic therapy: PFS, progression-free survival.

Percentages do not add up to 100 because of rounding up the values.

Early= T1-3N0M0; Locally advanced = T1-3N1M0, T4NxM0, and TxNxM1A; Metastatic =TxNxM1B.

Comparing cisplatin-treated to no-cisplatin patients.

Genotype frequency

The genotype frequencies in the entire sample for homozygous wild-type, heterozygous, and homozygous variants, respectively, were as follows: XPD Asp312Asn (rs1799793) 40%, 51%, and 9%; XPD Lys751Gln (rs13181) 38%, 52%, and 10%; ERCC1 8092C/A (rs3212986) 50%, 44%, and 6%; and for ERCC1 codon 118C/T (rs11615) 13%, 52%, and 36%. All four genotypes were in Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium. Genotyping was unsuccessful in only 13 cases, (<4%) for one or more polymorphisms.

Nucleotide excision repair genotype and outcome in cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin patients

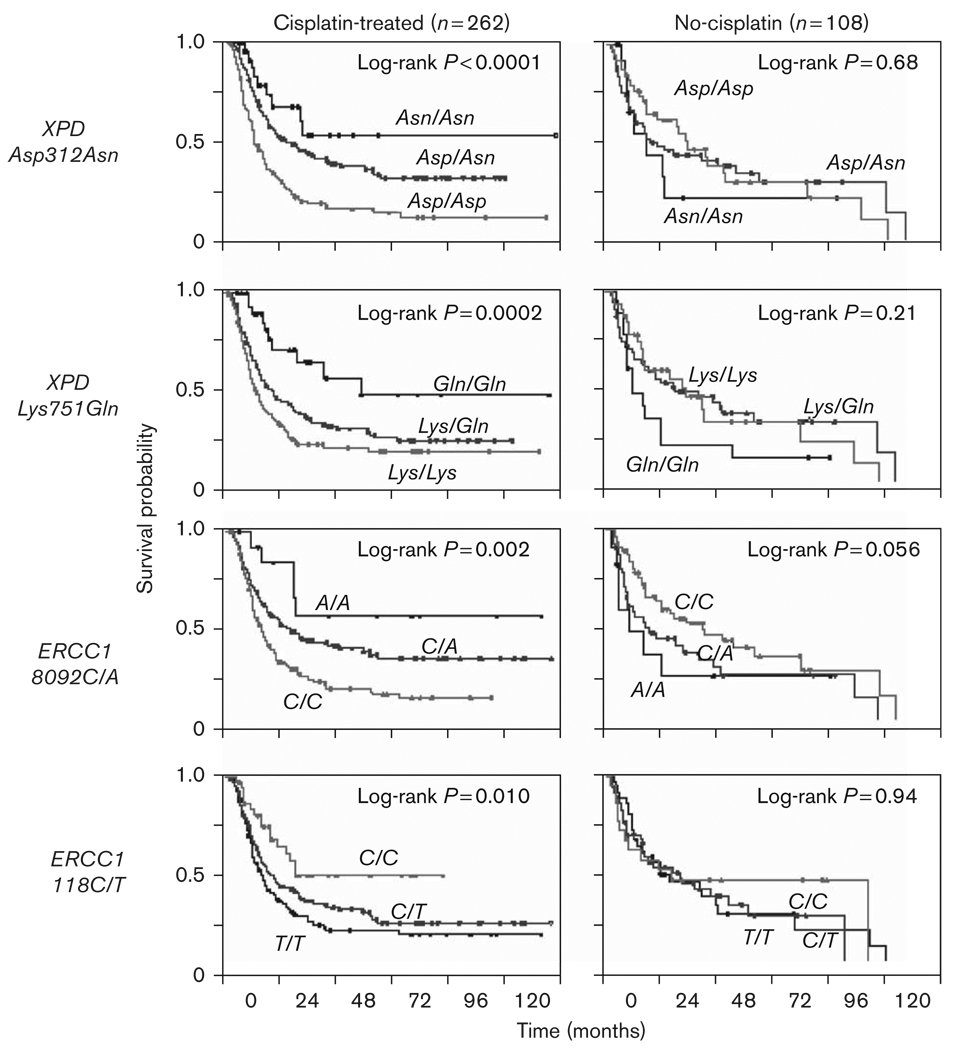

Table 2 shows the separate analyses for cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin patients. Within each treatment group, Kaplan–Meier curves were generated [Fig. 1 (OS) and Fig. 2 (PFS)], followed by CPH models for both additive and codominant models of inheritance (Table 2). For XPD Asp312Asn, the variant Asn allele was protective in cisplatin-treated patients, but had no effect on no-cisplatin patients. For both XPD Lys751Gln and ERCC1 8092C/A, the protective effects of the variant Gln and A alleles, respectively, in cisplatin-treated patients were reversed, with increased risks of the variant allele conferred onto the no-cisplatin patients. No significant results were found with ERCC1 codon 118C/T.

Table 2.

Analyses for cisplatin-treated patients (‘Cisplatin-treated’, n =262) and patients not treated with cisplatin (‘No-cisplatin’, n =108)

| Cisplatin-treated | No-cisplatin | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Patients/ events |

Months (median) |

AHRa (95% CI) | P | Patients/ events |

Months (median) |

AHRa (95% CI) |

P | |

| Overall survival | |||||||||

| XPD Asp312Asn | EVA | 0.52 (0.4–0.7) | < 0.0001 | 1.07 (0.7–1.6) | 0.76 | ||||

| (rs1799793) | Asp/Asp | 109/84 | 19 | Reference | 39/22 | 35 | Reference | ||

| Asp/Asn | 120/64 | 40 | 0.49 (0.4–0.7) | < 0.0001 | 55/29 | 34 | 0.88 (0.5–1.6) | 0.67 | |

| Asn/Asn | 27/7 | NA | 0.31 (0.1–0.7) | 0.003 | 14/8 | 17 | 1.36 (0.6–3.2) | 0.49 | |

| XPD Lys751Gln | EVA | 0.58 (0.4–0.8) | < 0.0001 | 1.57 (1.1–2.3) | 0.03 | ||||

| (rs13181) | Lys/Lys | 102/75 | 20 | Reference | 34/17 | 47 | Reference | ||

| Lys/Gln | 124/75 | 32 | 0.72 (0.5–1.0) | 0.05 | 55/29 | 34 | 1.56 (0.8–3.0) | 0.18 | |

| Gln/Gln | 31/7 | NA | 0.22 (0.1–0.5) | 0.002 | 19/13 | 17 | 2.47 (1.1–5.5) | 0.02 | |

| ERCC1 8092C/A | EVA | 0.61 (0.4–0.8) | 0.001 | 1.95 (1.3–2.8) | 0.0008 | ||||

| (rs3212986) | C/C | 137/95 | 22 | Reference | 56/23 | 60 | Reference | ||

| C/A | 109/59 | 40 | 0.67 (0.5–0.9) | 0.02 | 40/28 | 29 | 2.02 (1.1–3.7) | 0.02 | |

| A/A | 14/3 | NA | 0.23 (0.07–0.7) | 0.02 | 12/8 | 20 | 3.73 (1.6–8.7) | 0.002 | |

| ERCC1 codon 118C/T | EVA | 0.82 (0.6–1.0) | 0.10 | 1.14 (0.8–1.6) | 0.49 | ||||

| (rs11615) | T/T | 94/63 | 23 | Reference | 36/21 | 30 | Reference | ||

| T/C | 131/80 | 30 | 0.92 (0.6–1.3) | 0.63 | 49/26 | 34 | 1.02 (0.6–1.9) | 0.95 | |

| C/C | 37/14 | 45 | 0.57 (0.3–1.0) | 0.06 | 23/12 | 33 | 1.34 (0.6–2.8) | 0.43 | |

| Progression-free survival | |||||||||

| XPD Asp312Asn | EVA | 0.58 (0.4–0.8) | < 0.0001 | 1.06 (0.7–1.5) | 0.76 | ||||

| (rs1799793) | Asp/Asp | 107/88 | 10 | Reference | 38/25 | 24 | Reference | ||

| Asp/Asn | 119/73 | 22 | 0.59 (0.4–0.8) | 0.002 | 54/35 | 15 | 0.98 (0.4–2.3) | 0.43 | |

| Asn/Asn | 27/9 | NA | 0.33 (0.2–0.7) | 0.002 | 14/8 | 12 | 1.24 (0.7–2.1) | 0.96 | |

| XPD Lys751Gln | EVA | 0.67 (0.5–0.9) | 0.001 | 1.26 (0.9–1.8) | 0.24 | ||||

| (rs13181) | Lys/Lys | 101/77 | 12 | Reference | 32/20 | 24 | Reference | ||

| Lys/Gln | 122/86 | 17 | 0.85 (0.6–1.2) | 0.31 | 55/34 | 21 | 1.08 (0.6–1.9) | 0.789 | |

| Gln/Gln | 31/10 | 51 | 0.32 (0.2–0.6) | 0.0007 | 19/14 | 8 | 1.60 (0.8–3.4) | 0.20 | |

| ERCC1 8092C/A | EVA | 0.66 (0.5–0.9) | 0.004 | 1.56 (1.1–2.3) | 0.02 | ||||

| (rs3212986) | C/C | 136/104 | 13 | Reference | 55/32 | 30 | Reference | ||

| C/A | 107/64 | 22 | 0.72 (0.5–1.0) | 0.05 | 40/29 | 11 | 1.49 (0.9–2.6) | 0.16 | |

| A/A | 14/5 | NA | 0.32 (0.1–0.8) | 0.02 | 11/7 | 7 | 2.56 (1.1–6.0) | 0.03 | |

| ERCC1 codon 118C/T | EVA | 0.78 (0.6–1.0) | 0.04 | 0.99 (0.7–1.4) | 0.95 | ||||

| (rs11615) | T/T | 94/70 | 13 | Reference | 36/26 | 17 | Reference | ||

| T/C | 128/87 | 16 | 0.96 (0.7–1.3) | 0.80 | 48/30 | 21 | 0.92 (0.5–1.9) | 0.58 | |

| C/C | 37/16 | 26 | 0.50 (0.3–0.9) | 0.01 | 22/12 | 17 | 1.17 (0.7–2.0) | 0.82 | |

Significant values are set in bold.

AHR, adjusted hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; EVA, effect of ‘each variant allele’ assuming additive model of inheritance; NA, not applicable.

Adjusted for age, sex, disease stage and performance status.

Fig. 1.

Association between each of the four polymorphisms and overall survival for cisplatin-treated (cisplatin-treated patients) (left panel: Kaplan–Meier Curves) and no-cisplatin (patients not treated with cisplatin) groups (right panel: Kaplan–Meier Curves). Log-rank P values are presented.

Fig. 2.

Association between each of the four polymorphisms and progression-free survival for cisplatin-treated (cisplatin-treated patients) (left panel: Kaplan–Meier Curves) and no-cisplatin (patients not treated with cisplatin) groups (right panel: Kaplan–Meier Curves). Log-rank P values are presented.

Polymorphism–treatment interaction and outcome (Table 3)

Table 3.

NER polymorphism–cisplatin treatment interaction analysis

| Interaction P value | ||

|---|---|---|

| Polymorphism | Overall survival | Progression-free survival |

| XPD Asp312Asn (rs1799793) | 0.002 | 0.006 |

| XPD Lys751Gln (rs13181) | 0.0001 | 0.008 |

| ERCC1 8092C/A (rs3212986) | <0.0001 | 0.0007 |

| ERCC1 codon 118C/T (rs11615) | 0.13 | 0.27 |

Significant values are set in bold.

Interaction P values are derived from the polymorphism–treatment term from a Cox proportional hazard model, assuming an additive model of inheritance.

NER, nucleotide excision repair.

Statistically significant interactions were observed for XPD Asp312Asn, XPD Lys751Gln, and ERCC1 8092C/A for outcome (OS and PFS), using both additive (Table 3) and codominant (Supplementary Table 1) models of inheritance. No significant results were found in any analyses involving ERCC1 codon 118.

After applying the Bonferroni’s adjustment for multiple comparison at P = 0.002, the association with OS and PFS, for both XPD SNPs and ERCC1 8092C/A, remained significant in the additive model of inheritance, in the cisplatin interaction analysis for OS and for many of the analyses of OS and PFS in the codominant model of inheritance.

Exploratory subgroup analyses

Subgroup analyses across a number of clinical factors were performed because there were differences in the distribution in the age of diagnosis and in disease stage between cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin cohorts of patients. Supplementary Table 2 presents the results from these subgroup analyses for the three polymorphisms that yielded significant main associations, XPD Asp312Asn, XPD Lys751Gln, and ERCC1 codon 8092C/A, assuming an additive model of genetic inheritance. For the most part, the subgroup analyses confirm that these polymorphism trends were present in many different strata by age, sex, PS, stage, histology, and anatomic location of cancer. Similar consistent results were found using a codominant model of inheritance (example is presented in Supplementary Table 3). Finally, we also considered separately, individuals treated with specific chemotherapy combinations (cisplatin/5-fluorouracil, cisplatin irinotecan, cisplatin/taxane), in each case the same genotype-outcome trends were found when compared with no-cisplatin patients (data not presented).

We also explored treatment subgroups. Patients undergoing trimodality therapy constituted the vast majority of cisplatin-treated patients. We performed a subanalysis in the 198 patients who underwent intention to treat with cisplatin-based trimodality therapy. In this homogeneously treated group of patients (none of whom had metastatic disease), results were virtually identical to the larger group of cisplatin-treated patients (data not presented). In the surgically resected patients, which formed the largest subgroup of no-cisplatin patients, results were very similar to all no-cisplatin group (data not presented). As non-Caucasians and patients receiving transhiatal surgical resections were rare, we reanalyzed data that excluded these patients in Supplementary Table 4, along with subset analyses by histology in Supplementary Tables 5 and 6.

Haplotype analysis

As the four NER polymorphisms evaluated are in linkage disequilibrium, haplotype analysis was performed to assess the combined effect of XPD Lys751Gln (A/C), XPD Asp312Asn (G/A), ERCC1 8092C/A, ERCC1 codon 118C/T together, in cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin groups. There was a strong interaction between haplotype and cisplatin treatment for OS (P = 0.0005). In the cisplatin-treated cohort, patients carrying the haplotype of wild-type alleles of each of the four polymorphisms had a shorter OS compared with all other haplotype subgroups [AGCT/AGCT vs. all other groups OS: adjusted hazard ratio (AHR): 2.92, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.74–4.87, P > 0.0001; AGCT/—— AHR: 1.75, 95% CI: 1.12–2.76, P = 0.01]. Results were similar for PFS. In contrast, in the no-cisplatin group, patients carrying the haplotype of wild-type alleles of each of the four NER polymorphisms had longer OS (AGCT/AGCT vs. all other groups OS: AHR 0.64, 95% CI: 0.28–1.44, P = 0.28; AGCT/—— AHR: 0.50, 95% CI: 0.28–0.89, P = 0.02).

Discussion

In this study, three of four NER polymorphisms, XPD Asp312Asn (rs1799793), XPD Lys751Gln (rs13181), and ERCC1 8092C/A (rs3212986), were strongly associated with OS and PFS in cisplatin-treated patients with esophageal cancer. Our results are suggestive of a predictive effect through highly significant polymorphism–cisplatin treatment interactions, even after correction for multiple polymorphism comparisons. Exploring further, the nature of these interactions through subgroup analyses, cisplatin-treated patients carrying variant alleles of XPD Asp312Asn, XPD Lys751Gln, and ERCC1 8092C/A had improved outcomes compared with patients carrying the wild-type genotypes of each of these polymorphisms. The same polymorphism–outcome relationships were not found in the no-cisplatin group. Results were consistent across the two models of genetic inheritance, across various methods of performing interaction analyses, across multiple subgroup analyses, in both crude and adjusted analyses, and in haplotype analyses of the four linked polymorphisms. Thus, our findings are robust regardless of model assumptions. In addition, we applied multiple quality control mechanisms for clinical outcome data collection [26].

Although we hypothesized that NER polymorphisms predict outcome for cisplatin-treated patients, we anticipated that the same polymorphisms might not have an association with survival in the no-cisplatin group. This was indeed what was found for XPD Asp312Asn. In contradistinction, the variant allele of ERCC1 8092C/A was associated with worse outcome in the no-cisplatin group. Opposing effects of ERCC1 protein in cisplatin and non-cisplatin-treated patients have been described earlier. In a retrospective study of ERCC1 protein expression in esophageal cancer from patients treated with preoperative cisplatin-based chemoradiation or surgery alone [31], patients with low intratumoral ERCC1 expression tended to benefit from preoperative therapy, whereas there was a trend in the opposite direction favoring surgery only for patients with ERCC1-expressing tumors. This was also the finding in a randomized controlled trial of cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy in non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC), where the absence of intratumoral ERCC1 protein expression conferred a poorer prognosis in patients randomized to surgery alone. However, for patients in the cisplatin-based chemotherapy arm, the benefit from adjuvant chemotherapy was restricted to those patients with tumors that did not express ERCC1 [9]. One theory postulates that in the absence of cisplatin therapy, poor DNA repair may result in more biologically aggressive tumors through susceptibility to greater genetic aberrations over time, resulting in worse outcome.

The results of our cisplatin-treated arm are consistent with prior studies evaluating DNA repair polymorphisms in malignancies of the aerodigestive tract [21,22,32,33]. In a study of DNA repair polymorphisms in patients with head and neck cancer, the variant alleles of XPD Lys751Gln and XPD Asp312Asn were associated with improved survival [21]. In a recent study evaluating the association of NER polymorphisms in NSCLC patients treated with a gemcitabine and docetaxel combination, the variant allele of XPD Lys751Gln was unfavorable, which is in keeping with the finding in our no-cisplatin cohort [32]. Further, the variant allele of ERCC1 8092C/A was associated with an increased risk of gastrointestinal toxicity after platinum-based chemotherapy, which was postulated to arise from a decreased DNA repair [33]. However, in a study of cisplatin-treated patients with esophageal cancer, no independent association was found for either ERCC1 8092C/A or XPD Lys751Gln [22]. This study included 136 cisplatin-treated patients with a median follow-up time of 18.6 months, and may have been underpowered to detect an independent association for XPD Lys751Gln or ERCC1 8092C/A. For example, the number of patients with the wild-type variant genotype for both SNPs was 4 and 6, respectively [22]. This compares with our study with almost double the number of cisplatin-treated patients, and 31 patients carrying the homozygous variant genotype for XPD Lys751Gln and 14 for ERCC1 8092C/A. Despite this, when Wu et al. [22] combined at risk alleles of nine NER polymorphisms, the trend was in the same direction as our data.

These NER SNPs have been evaluated in other NSCLC studies [17,18], ovarian [23] and colorectal cancer [20] cohorts, with discordant results. This may indicate that the biologic significance of SNPs is tissue dependent, as is the case with other biomarkers. Alternatively, it may reflect variation in patient demographics and treatments delivered across studies. For example, a number of studies in oxaliplatin-treated colorectal cancer patients have found an association between OS and ERCC1 C/T (rs11615), which we did not identify as having prognostic significance in our study [20,24]. A recent prospective, randomized trial of paclitaxel/carboplatin versus docetaxel/carboplatin in patients with ovarian cancer did not find an association between any of the DNA repair polymorphisms evaluated and outcome [16]. Whether polymorphism-related DNA repair effects differ among the platinum agents has yet to be determined. A further difference between these studies is that cisplatin was predominantly delivered concurrently with radiation in our cisplatin cohort, and commonly in the study of patients with head and neck cancer [15]. The NER pathway is not the predominant repair mechanism of radiation DNA damage, but increases platinum uptake [34], which may further compound polymorphism-related suboptimal DNA repair. Finally, XPD Lys751Gln has also been associated with altered paclitaxel cytotoxicity in cell line studies [35]. Unlike the lung and ovarian cancer studies, only a small percentage of our patients received cisplatin–taxane regimens as part of first-line therapy (6%), as the vast majority received cisplatin–5-fluorouracil and cisplatin–irinotecan-based regimens, which may have allowed us to evaluate the effect of these polymorphisms on cisplatin-treated patients without taxanes confounding these associations.

There are few limitations to our study. The optimal methodology to evaluate a potentially predicative biomarker is within the context of a randomized controlled trial [25]. Although our observational cohort was prospectively collected, with high-quality outcome collection procedure [26], there is potential for bias in the two nonrandomized cohorts to confound our results, particularly as our cohort was heterogeneous including patients with different histological subtypes, stage, and treatment of esophageal cancer. To evaluate this, we undertook additional subgroup analyses that explored the clinico-epidemiologic differences in the underlying populations between cisplatin-treated and no-cisplatin patients, and did not identify a confounding variable that could otherwise explain our results. However, our results are preliminary and require validation, preferably within the context of a clinical trial, in which treatment selection and patient demographics will be more homogeneous. We postulate that our results arise from impaired DNA repair within the tumor. Biopsy tissue, often obtained through endoscopy, are typically small and of limited utility. For this very reason, we lacked adequate pretreatment esophageal tumor tissues for the vast majority of cisplatin-treated patients to correlate our findings with protein expression. Finally, a candidate gene approach, based on published data, was used to select the relevant polymorphisms in this analysis. The focus of future studies may lie in more exploratory pathway-based and comprehensive genome-wide association studies. Nonetheless, our candidate gene approach is still valid. Even if the functionality of our selected polymorphisms is questioned, the exploratory haplotype analysis indicates that an undefined true functional polymorphism in linkage disequilibrium with our selected polymorphisms may explain our findings.

In summary, our polymorphism data are consistent with the differential effects of DNA repair associated with ERCC1 protein expression reported in NSCLC and esophageal cancer [9,31], and seem to be consistent across different cisplatin-based drug combinations and stages. However, as the aim of all these studies is to identify biomarkers that can be readily translated into the clinical setting, polymorphisms have the distinct advantage that testing can be performed on a simple blood sample. Our results are preliminary and require validation, but show how genotyping may ultimately be integrated into a combined molecular and clinico-radiologic approach to treatment selection for patients with esophageal cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by NIH grants R01 CA074386, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Alan B. Brown Chair in Molecular Genomics, Posluns Family, and Princess Margaret Hospital Foundations. The authors acknowledge the assistance of Peggy Suen, Salvatore Mucci, Richard Rivera-Massa, David P. Miller, Andrea Shafer, and Paul Wheatley-Price.

Footnotes

This study was presented in part at the American Society of Oncology Annual Meeting 2007

Publisher's Disclaimer: Disclaimers: none.

References

- 1.Bollschweiler E, Wolfgarten E, Gutschow C, Holscher AH. Demographic variations in the rising incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma in white males. Cancer. 2001;92:549–555. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010801)92:3<549::aid-cncr1354>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brucher BL, Stein HJ, Zimmermann F, Werner M, Sarbia M, Busch R, et al. Responders benefit from neoadjuvant radiochemotherapy in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results of a prospective phase-II trial. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:963–971. doi: 10.1016/j.ejso.2004.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Enzinger PC, Mayer RJ. Esophageal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:2241–2252. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra035010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Greer SE, Goodney PP, Sutton JE, Birkmeyer JD. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy for esophageal carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Surgery. 2005;137:172–177. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walsh TN, Noonan N, Hollywood D, Kelly A, Keeling N, Hennessy TP. A comparison of multimodal therapy and surgery for esophageal adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:462–467. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608153350702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Metzger R, Leichman CG, Danenberg KD, Danenberg PV, Lenz HJ, Hayashi K, et al. ERCC1 mRNA levels complement thymidylate synthase mRNA levels in predicting response and survival for gastric cancer patients receiving combination cisplatin and fluorouracil chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16:309–316. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wood RD. Nucleotide excision repair in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:23465–23468. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.38.23465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferry KV, Hamilton TC, Johnson SW. Increased nucleotide excision repair in cisplatin-resistant ovarian cancer cells: role of ERCC1-XPF. Biochem Pharmacol. 2000;60:1305–1313. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(00)00441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Olaussen KA, Dunant A, Fouret P, Brambilla E, André F, Haddad V, et al. DNA repair by ERCC1 in non-small-cell lung cancer and cisplatin-based adjuvant chemotherapy. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:983–991. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa060570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Duell EJ, Wiencke JK, Cheng TJ, Varkonyi A, Zuo ZF, Ashok TD, et al. Polymorphisms in the DNA repair genes XRCC1 and ERCC2 and biomarkers of DNA damage in human blood mononuclear cells. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:965–971. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spitz MR, Wu X, Wang Y, Wang LE, Shete S, Amos CI, et al. Modulation of nucleotide excision repair capacity by XPD polymorphisms in lung cancer patients. Cancer Res. 2001;61:1354–1357. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shen MR, Jones IM, Mohrenweiser H. Nonconservative amino acid substitution variants exist at polymorphic frequency in DNA repair genes in healthy humans. Cancer Res. 1998;58:604–608. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lunn RM, Helzlsouer KJ, Parshad R, Umbach DM, Harris EL, Sanford KK, et al. XPD polymorphisms: effects on DNA repair proficiency. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:551–555. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.4.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolfe KJ, Wickliffe JK, Hill CE, Paolini M, Ammen H, Euser MM, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms of the DNA repair gene XPD/ERCC2 alter mRNA expression. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2007;17:897–905. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e3280115e63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen P, Wiencke J, Aldape K, Kesler-Diaz A, Miiker R, Kelsey K, et al. Association of an ERCC1 polymorphism with adult-onset glioma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:843–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu JJ, Lee KB, Mu C, Li Q, Abernathy TV, Bostick-Bruton F, et al. Comparison of two human ovarian carcinoma cell lines 9A2780/CP70 and MCAS) that are equally resistant to platinum, but differ at codon 118 of the ERCC1 gene. Int J Oncol. 2000;16:555–560. doi: 10.3892/ijo.16.3.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gurubhagavatula S, Liu G, Park S, Zhou W, Su L, Wain JC, et al. XPD and XRCC1 genetic polymorphisms are prognostic factors in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2594–2601. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Isla D, Sarries C, Rosell R, Alonso G, Domine M, Taron M, et al. Single nucleotide polymorphisms and outcome in docetaxel-cisplatin-treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:1194–1203. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhou W, Gurubhagavatula S, Liu G, Park S, Neuberg DS, Wain JC, et al. Excision repair cross-complementation group 1 polymorphism predicts overall survival in advanced non-small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:4939–4943. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stoehlmacher J, Park DJ, Zhang W, Yang D, Groshen S, Zahedy S, et al. A multivariate analysis of genomic polymorphisms: prediction of clinical outcome to 5-FU/oxaliplatin combination chemotherapy in refractory colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2004;91:344–354. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quintela-Fandino M, Hitt R, Medina PP, Gamarra S, Mansol L, Cortes-Funes H, et al. DNA-repair gene polymorphisms predict favorable clinical outcome among patients with advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck treated with cisplatin-based induction chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4333–4339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.05.8768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Gu J, Wu TT, Swisher SG, Liao Z, Correa AM, et al. Genetic variations in radiation and chemotherapy drug action pathways predict clinical outcomes in esophageal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3789–3798. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.6640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsh S, Paul J, King CR, Gifford G, McLeod HL, Brown R. Pharmacogenetic assessment of toxicity and outcome after platinum plus taxane chemotherapy in ovarian cancer: the Scottish Randomised Trial in Ovarian Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:4528–4535. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.10.4752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paré L, Marcuello E, Alté s A, del Rio E, Sedano L, Salazar J, et al. Pharmacogenetic prediction of clinical outcome in advanced colorectal cancer patients receiving oxaliplatin/5-fluorouracil as first line chemotherapy. Br J Cancer. 2008;99:1050–1055. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McShane LM, Altman DG, Sauerbrei W, Taube SE, Gion M, Clark GM. Reporting recommendations for tumor marker prognostic studies (REMARK) J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1180–1184. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bradbury PA, Heist RS, Kulke MH, Zhou W, Marshall AL, Miller DP, et al. A rapid outcomes ascertainment system improves the quality of prognostic and pharmacogenetic outcomes from observational studies. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:204–211. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stephens M, Smith NJ, Donnelly P. A new statistical method for haplotype reconstruction from population data. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;68:978–989. doi: 10.1086/319501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zaykin DV, Westfall PH, Young SS, Karnoub MA, Wagner MJ, Ehm MG. Testing association of statistically inferred haplotypes with discrete and continuous traits in samples of unrelated individuals. Hum Hered. 2002;53:79–91. doi: 10.1159/000057986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cordell HJ. Estimation and testing of genotype and haplotype effects in case-control studies: comparison of weighted regression and multiple imputation procedures. Genet Epidemiol. 2006;30:259–275. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sham PC, Rijsdijk FV, Knight J, Makoff A, North B, Curtis D. Haplotype association analysis of discrete and continuous traits using mixture of regression models. Behav Genet. 2004;34:207–214. doi: 10.1023/B:BEGE.0000013734.39266.a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim MK, Cho K, Kwon GY, Park S, Kim YH, Kim JH, et al. Patients with ERCC1-negative locally advanced esophageal cancers may benefit from preoperative chemoradiotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:4225–4231. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Petty WJ, Knight SN, Mosley L, Louato J, Capellari J, Tucker R, et al. A pharmacogenomic study of docetaxel and gemcitabine for the initial treatment of advanced non-small cell lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:197–202. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318031cd89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suk R, Gurubhagavatula S, Park S, Zhou W, Su L, Lynch TJ, et al. Polymorphisms in ERCC1 and grade 3 and 4 toxicity in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:1534–1538. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yang L, Douple EB, Wang H. Irradiation enhances cellular uptake of carboplatin. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1995;33:641–646. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(95)00202-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Le Morvan V, Bellott R, Moisan F, Mathoulin-Pelissier S, Bonnet J, Robert J. Relationship between genetic polymorphisms and anticancer drug cytotoxicity vis-a-vis the NCI-60 panel. Pharmacogenomics. 2006;7:843–852. doi: 10.2217/14622416.7.6.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu G, Zhou W, Yeap BY, Su L, Wain JC, Poneros JM, et al. XRCC1 and XPD polymorphisms and esophageal adenocarcinoma risk. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:1254–1258. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tse D, Zhai R, Zhou W, Heist RS, Asomaning K, Su L, et al. Polymorphisms of the NER pathway genes, ERCC1 and XPD are associated with esophageal adenocarcinoma risk. Cancer Causes Control. 2008;19:1077–1083. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9171-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.