Abstract

The present study explored the types of major life and chronic stressors that people with severe mental illness experience, and the coping strategies that are used in response to them. Twenty-eight adults with severe mental illness completed qualitative interviews focused on stress and coping in the prior six months. Participants reported experiencing disruptive major life events including the sudden death of a loved one, loss of housing, and criminal victimization, as well as chronic stressors such as psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse issues, substandard living conditions, legal problems, and health concerns. Results suggested that persons with severe mental illness frequently use problem-centered coping strategies in response to most types of stressors, including major life events, although this occurred after the initial application of avoidant coping strategies. Future research should explore whether or not the identified stressors and the coping strategies used in response to them are unique to this population.

Over the last few decades, increased emphasis has been placed on the community integration of individuals diagnosed with severe mental illness (SMI) and the enhancement of services to facilitate this transition (1, 2). Although there are several factors that may affect community integration, the experience of life stressors and the use of coping strategies to deal with these external demands may substantially contribute to this process (3). In addition to the stress associated with psychiatric symptoms that individuals with SMI encounter (4), there appear to be several psychosocial stressors that may be frequently experienced within this population (5–7). Given the interaction that exists between external stressors and symptoms (3), identifying and understanding these stressors and coping responses may assist in designing community mental health services that can better meet the needs of persons with SMI.

Three major categories of stressors have been identified within the broader social science literature: life events, chronic strains and daily hassles (8). Life events are typically unexpected significant changes that require substantial readjustment within a short time period (8, 9). Despite the relatively rare occurrence of life events, in comparison to other types of stressors, they have been found to have considerable impact on psychological well-being in addition to increasing symptom severity and the likelihood of psychiatric relapse (10, 11). Chronic strains (or stressors) refer to “the persistent or recurrent difficulties of life” (12, p. 7) that generally continue over an extended period of time. The final category of stressors, daily hassles, includes minor sporadic events that transpire on a day-to-day basis usually entailing minimal adjustment (8).

Regarding the occurrence of stress, the existing literature indicates that individuals of lower socioeconomic status (SES) may experience specific types of stressors more frequently than people of high SES (13, 14). Although these findings may be applicable to people with SMI, due to the association between psychiatric illness and socioeconomic status (15), there may be additional stressors that are unique to this population. Indeed, poverty, homelessness (5), social rejection and stigmatization (6, 7), and vulnerability to criminal victimization (16) are a few of the identified psychosocial stressors that persons with SMI may be more likely to experience. However, a recent review (17) concluded that relatively little is still known about the experience and impact of stressors among persons with SMI, particularly how such individuals appraise the stressors that they encounter.

The potentially high exposure to psychosocial stressors, coupled with the considerable number of psychiatric symptoms that may occur within this population, highlights the importance of coping responses to manage these experiences. Previously, Roe, Yanos and Lysaker (4) discussed the complex range of coping responses that need to be considered among individuals with SMI. They characterized coping that is employed in response to a symptom or stressor as “reactive” coping and distinguished between primarily problem-centered and avoidant responses to stressors. While there has been a considerable amount of research pertaining to the utility of particular coping strategies, there is a need for a more nuanced understanding of how coping responses may vary depending on the context of the stressor being experienced, and how the use of multiple coping strategies may impact the response to stress. The purpose of the present study was to shed light on the types of major life and chronic stressors that people with SMI experience, and the coping strategies that are used in response to them. Given the difficulty of examining such issues using traditional “checklist” approaches, the present study used qualitative methods to elicit detailed narratives relating to stress and coping.

METHOD

PARTICIPANTS

Participants in this study included 28 adults (16 male and 12 female) recruited through two community mental health agencies servicing adults diagnosed with SMI: a day treatment program located in Newark, New Jersey (15 participants), and three Assertive Community Treatment teams affiliated with the same agency operating in the East and West Harlem neighborhoods of New York City (13 participants). All participants were voluntarily participating in services. At the time of recruitment, individuals participating in Illness Self-Management (18) services at these programs were eligible to participate in the study. These services included both individual and group-based services designed to educate clients about how to cope with symptoms and stressors. The study focused on individuals participating in Illness Management in order to focus particularly on persons more likely to develop new coping strategies during the course of the larger six-month study. In the first recruitment site, nearly all clients were participating in Illness Management, so this criterion did not restrict eligibility; in the second location, a somewhat smaller group of clients participated in these types of services. Participants had a mean age of 45.43 (SD = 9.23) and a mean educational level of 11.17 (SD = 2.15). Regarding ethnic identification, four (14.3%) participants identified themselves as European-American, 17 (60.7%) as African American, six (21.4%) as Latino and one (3.6%) as Asian/Pacific Islander. Regarding psychiatric diagnosis, participants were primarily diagnosed with either a psychotic disorder or a mood disorder; 10 participants (35.7%) had a primary chart diagnosis of schizophrenia at the start of the study, while six (21.4%) were diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder, three (10.7%) with bipolar disorder, seven (25%) with major depression or mood disorder NOS, and two (7.1%) with post-traumatic stress disorder. Participants were largely diagnosed with cooccurring substance abuse problems, with 22 (78.6%) having a secondary substance use diagnosis recorded in their charts. Approval was received from the Institutional Review Boards of Rutgers University, the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey, and John Jay College of Criminal Justice, and all participants provided informed consent before participating in the study.

PROCEDURE

Data were drawn from two baseline interviews gathered during a larger six-month study which also consisted of two separate periods of 10 consecutive daily interviews and 26-month follow-up interviews. During the first baseline interview, participants answered a series of open-ended questions focused on eliciting narratives of coping with symptoms and stressors experienced during the previous six months. During the second interview, researchers were given the opportunity to follow-up on and further explore areas discussed in the first interview, as well as obtain information regarding demographics, symptoms and recent substance use. Open-ended interviews were tape-recorded and transcribed for subsequent analysis.

ASSESSMENTS

Semi-structured, qualitative interviews were conducted with all participants. The focus of these interviews was to gather information needed to construct a valid “narrative” describing the individual's sequence of efforts used to cope with symptoms and other problems related to mental illness experienced within the past six months. Interviews started with a broad overview of the subject matter (akin to the “grand tour question” suggested by Spradley, 19), and then began with a single open-ended question: “How have things been going for you over the last six months?” Interviewers were instructed to listen intently to leads provided in response to this question and to follow-up in-depth on all areas raised by the participant. In-depth follow-up consisted of trying to elicit the “story” of “what happened” as it unfolded over time in the case of a specific event, or a recent occurrence of an ongoing symptom or chronic stressor. Interviewers were instructed to elicit information on coping for each event discussed (“How did you deal with that? Tell me about all the things you did”). Additionally, in cases in which participants did not spontaneously offer information, interviewers were given specific areas to explore, such as positive changes, stressful events and psychiatric symptoms.

ANALYSES

Transcripts were analyzed using an open-coding approach as a general framework (20), with a specific focus on information pertaining to stress and coping. First, transcripts were read and general categories of response topics were derived (e.g., major life stressors). Groups of text were placed within these categories, re-read and then re-grouped into subcategories (e.g., chronic stressors – housing instability). Responses were categorized as either major life events or chronic stressors based upon the participant's appraisal of the event. While the culmination of daily hassles may also be a source of significant stress which may tax an individual's overall coping ability, participants did not discuss these types of stressors during the initial baseline interviews. Evaluation of the appraisal was drawn from the participant's statement that it was an important event, or from the emotional response that was observed during this discussion. Responses within each subcategory were reviewed for exemplary passages reflecting the various themes contained within the responses. Interview transcripts were independently analyzed and coded by two raters. In areas where there was disagreement in ratings, consensus was reached through discussion with the senior author who sometimes acted as an arbiter. Stressors were only coded into one category. Raters also assessed the extent to which participants used coping strategies to deal with the reported stressors. Based on recommendations in the existing literature (21), coping responses were categorized as either problem-centered (behavioral and cognitive problem-centered actions, social support efforts, prescribed medication use, and “active” distraction efforts such as meditative refocusing), neutral (behavioral and cognitive distraction efforts, use of non-addictive substances, emotional acceptance strategies), or avoidant (behavioral and cognitive avoidance strategies, use of addictive substances, “going along with symptom,” emotional outburst or resignation, social withdrawal, and doing nothing). Coding of coping strategies was informed by the perspective that the context in which a strategy is used is essential in order to inform judgements of whether it is problem-centered or avoidant. So, for example, deliberately reducing activity would be regarded as a problem-centered strategy in response to manic symptoms, but as an avoidant strategy in response to depressive symptoms.

RESULTS

MAJOR LIFE STRESSORS

When asked to describe what had been happening in their lives in the past six months, 21 participants spontaneously discussed experiencing at least one major life stressor (16 reported experiencing two or more). The average number of reported major life stressors was 1.59 (SD = 1.08), ranging from 0 to 3. Table 1 summarizes the major life stressors reported by participants.

Table 1.

Categories of Major Life and Chronic Stressor Reported within 6 Months

| Number of Participants (n=28) | % of Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Major Life Stressors | ||

| Awareness of Illness | 8 | 28.57 |

| Death of a Loved One | 8 | 28.57 |

| Loss of Housing | 7 | 25.00 |

| Legal Involvement | 6 | 21.43 |

| Criminal Victimization | 6 | 21.43 |

| Hospitalization | 2 | 7.14 |

| Ending of Relationship | 2 | 7.14 |

| Witnessing Crime | 1 | 3.57 |

| Loss of Employment | 1 | 3.57 |

| Chronic-Persistent Stressors | ||

| Psychiatric and Substance Abuse issues | 16 | 57.14 |

| Compromised Living Conditions | 15 | 53.57 |

| Family Discord | 11 | 39.29 |

| Problems with Services | 8 | 28.57 |

| Financial Problems | 7 | 25.00 |

| Interpersonal Difficulties | 5 | 17.86 |

| Health Concerns | 5 | 17.86 |

| Legal Involvement | 5 | 17.86 |

| Side Effects of Medication | 3 | 10.71 |

As illustrated in Table 1, the most common categories of major life stressors reported by participants were becoming aware of an illness and death of a loved one. Among the eight participants who discussed becoming aware of an illness, six explained the stress associated with finding out that they had an illness, while two reported stress associated with finding out that a significant other had an illness. Life threatening and chronic illnesses (e.g., diabetes, Hepatitis C, HIV) were typically reported. Regarding this major life stressor, one participant stated:

I found out I have Hepatitis C. So, I'm struggling with that and can't handle that too. The past six months it's been an up and down battle with that, and I don't really like going to the doctor for that.

Several participants also discussed the death of a loved one within the previous six months. Of the eight participants who discussed this type of stressor, four indicated that a loved one had died suddenly as a result of an accident, while three reported losing a loved one due to an illness. As an example of the type of experience reported in this instance, one participant discussed the sudden loss of her adult son:

He was talking about getting this apartment and me and him could move in together. And then all of a sudden he was gone. They said it was an accident but he had a asthma attack under the water but I don't know about that. He don't know how to swim he wouldn't have been in that much water….I felt shocked, I felt sick and I…I feel like I thought I…I thought I was gonna die.

The categories legal involvement, criminal victimization, and witnessing of crime reflect the reality that many participants were either arrested for allegedly committing a crime (or had family members who were arrested), or were victims or witnesses of a crime. Among the six participants discussing legal involvement as a major stressor, five discussed an arrest that they had experienced. This was typically characterized as an instance in which they were targeted by the police due to their prior criminal history. For example:

I was outside of my area during a sweep and the officer that arrested me before for drugs recognized me and uh picked me up on attempted sale…. I did not try to sell no drugs and I knew the officer only picked me up because he knew me from my past history.

A wide range of experiences were reported with regard to criminal victimization (usually theft), but one participant reported being sexually assaulted by someone a roommate had let into her apartment. This same participant also discussed witnessing a murder in the prior six months, indicating that there was a high concentration of criminal activity in the “drug-infested” building where she lived:

I'm coming home from the program this guy was running, running and he pushed me out the way, and I said watch it what are doing you jerk, and he turned around and looked at me and then I thought I saw fear in his face and just as I was coming into the house another boy pushed me and he came and he stabbed the guy and he killed him. And I was a witness to that.

Loss of housing was another major stressor reported by several (6) participants. In some cases, the loss was the result of external circumstances, while others reported being evicted due to alleged substance abuse. Many of these participants had to subsequently move into shelters or other compromised living situations as a result of the loss of a more stable housing situation. One participant discussed how she lost her housing after the death of a relative that she cared for:

He [relative's son] got mad because I wouldn't … I wouldn't tell him … where all of her important papers was so he threw me out of the house. … I wound up in a shelter… I couldn't believe, I mean, this was happening to me.

Other major losses reported by participants were the ending of a close interpersonal relationship (3) and loss of employment (reported by one participant). The participant whose loss of employment was characterized as a major life stressor stated:

So I got this other new job at the end of November being a waiter at a catering place and I got arrested. So I lost that job…that made me get depressed.

CHRONIC STRESSORS

All participants also spontaneously discussed experiencing at least one chronic stressor (21 reported experiencing two or more) in the previous six months. The average number of reported chronic stressors was 2.88 (SD = 1.42), and ranged from 1 to 6 (see Table 1). The most frequently reported chronic stressors were issues concerning psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse (15). These included concerns with persistent psychiatric symptoms (e.g., depression or auditory hallucinations) reported by three participants, and urges to use substances (reported by nine participants). One participant discussed the auditory hallucinations that he hears on a nightly basis:

[I hear the voices] when I'm getting ready to go to bed… When I get by myself that's when I hear them.

Reported almost as commonly, however, were concerns regarding compromised housing circumstances. Types of problems reported varied depending on the participant's type of housing situation (six discussed problems related to living in a shelter, three related to living with a roommate, five related to living alone, one discussed problems related to living with a family member). Many of the participants living in shelters had also experienced loss of housing as a major life stressor. Participants living in shelters often discussed the stress associated with lack of privacy or the need to comply with curfews. For example:

Getting up early in the morning. I mean…when you have bad weather, I don't care what the weather is like you gotta leave. You gotta be out by eight, every morning except Saturday and Sunday. During the week you have to be up and out of there by eight and you are not allowed back 'til three. If I did not have anything do you with my time what would I do?

Participants living with roommates or independently also complained of lack of safety. One participant living in an independent apartment discussed his chronic fear of his community:

I don't like it there. I don't feel safe. I feel like somebody is going to break my door in soon… sooner or later and probably shoot me down, I don't know cause the neighborhood is like that.

Family discord and lack of family support were also commonly reported (11 participants). While four participants talked about the chronic stress associated with lack of contact with family members (due to a previous dispute or argument), seven participants discussed ongoing strife with family members. One participant discussed negative criticism from his father due to receiving psychiatric treatment:

My mom and aunts are positive, but my dad in New York ain't. And it was…a lot of stress has been going on in the family saying, you know you shouldn't be collecting a check you shouldn't be in a program, there's nothing wrong with you…

A related category was interpersonal relationship problems, which were reported by five participants. While one participant discussed the chronic stress associated with not having an intimate relationship, four reported currently being involved in an abusive relationship characterized by frequent arguments and sometimes physical violence. For example:

He just called me names and followed me, stalked me and stuff like that but he stopped…when I left him…He doesn't like the fact that I have a job he wants to be…he wants to be in charge of everything and I…I don't need that.

Several participants (8) also discussed their struggle with trying to have their needs met by the social and mental health service systems as a chronic stressor. Five participants discussed their frustration and ongoing conflict in their attempt to obtain welfare benefits, SSI or other entitlements, while two participants discussed difficulty dealing with staff members at the shelter where they resided. In a related vein, seven participants reported that they experienced chronic financial stress as a result of not having enough money to pay for basic living expenses.

Related to the commonly reported major life stressor of finding out that one has an illness, five participants discussed the chronic stress associated with managing physical health problems, such as taking medication or coping with fluctuations in physical health. For example:

Yeah, so I have three illnesses to, trying to cope with that. But this diabetes is kicking me in the butt. It's not normal, it won't stay in this normal level. They want me to do dialysis, I refused that. I refused that because my mother was on dialysis and she died from that three months after she took the dialysis for diabetes.

Concerns with the side effects of medication were also discussed by three participants. One participant discussed the intense effects resulting from taking medication for Hepatitis C:

… it messed me up. That must have had me transformed. Cause they tell me too, even the doctor said it will make you moody and transformed, you know. But when I stop taking it, I just cry.

Related to the major life stressor category of legal involvement, five participants discussed the chronic stress associated with dealing with the legal system (such as probation, parole, or drug courts), either for oneself (3) or others (2). For example, one participant discussed the stress he experienced as a result of the need to keep returning to court:

Well lately I've been going to court. Back and forth to court. I've been going back and forth to court… I used to be really depressed 'cause I didn't want to go to jail and going constantly to court kept me, you know, kept me, like depressed.

PROBLEM-CENTERED COPING

Participants typically reported using coping strategies in response to the stressors they reported experiencing in the past six months. Table 2 reports the number of coping strategies reported by respondents for each category and the specific types of coping strategies coded for each category. As can be seen in Table 2, problem-centered coping strategies were most commonly reported by participants. All but two participants reported using at least one problem-centered coping strategy, while the mean number of problem-centered strategies reported was 2.8 (SD=1.79) out of a range of 0–6. Problem-centered strategies fell into a number of broad groupings, including seeking professional help, problem solving, cognitive strategies and social support.

Table 2.

Categories of Coping Strategies in Response to Stressors

| Number of Participants (N = 28) | % of Sample | |

|---|---|---|

| Avoidant Coping (n = 21) | 53.57% | |

| Leaving/Avoiding StressfulEnvironment/Situation | 7 | |

| Isolation | 2 | |

| Substance Use | 8 | |

| Acting out Aggressively | 4 | |

| Neutral Coping(n = 14) | 32.1% | |

| Acceptance | 6 | |

| Ignoring | 4 | |

| Cognitive Distraction | 4 | |

| Problem-Centered Coping (n = 97) | 85.7% | |

| Professional Assistance | ||

| Seeking Professional Mental Health Treatment | 25 | |

| Medication | 9 | |

| Seeking Medical Treatment | 5 | |

| Social Support | ||

| Support Groups (outside of program) | 2 | |

| Support from Family/Friends | 13 | |

| Cognitive | ||

| Positive thinking/Self-help | 10 | |

| Spirituality | 9 | |

| Problem Solving | ||

| Seeking Employment | 1 | |

| Seeking Housing/Moving | 7 | |

| Filing Complaints to Obtain Services | 8 | |

| Avoiding People who Use Drugs | 2 | |

| Hiring Help | 2 | |

| Quitting Smoking | 1 | |

| Stop Using Drugs | 2 | |

| Ending Unhealthy Relationships | 1 |

Seeking professional help was the most common class of problem-centered strategies reported in the sample (39 instances). Subtypes of this category included seeking professional mental health services (25), taking medication (9), and seeking medical treatment (5). As an example of the type of strategy reported in this category, one participant discussed the importance of meeting with her therapist in order to cope with the chronic stressor of family conflict:

I just started crying. I left, you know and I came home and I felt really lonely, really like I had nobody, I have no friends… If I couldn't talk to [individual therapist] I wouldn't make it, but I make it every Thursday, that's when I have individual therapy. Cause I um, I…I feel like I have to be here for that.

Problem-solving was the second most common class of problem-centered coping strategies reported (24 instances). In this category, participants discussed taking concrete steps to deal with chronic and major life stressors, including: seeking employment (1), seeking housing/moving (7), filing a complaint to get necessary help (8), avoiding people that use drugs (2), hiring help (2), quitting smoking (1), stopping drug use (2), and ending a stressful relationship (1). For example, one participant discussed how he sought assistance from a mental health staff member in order to get entitlement checks from Welfare:

and I kept on going back and forth down there taking my check and then I finally I got tired of going back…going down there so I …so I got [a supervisor in the Program], he went down and talked to my caseworker. He got my check, all three of my checks a couple days later. He went down there for me and they talked to my case worker and straightened me out and I got my check a couple days later, well all three of my checks a couple days later.

Another commonly reported method of coping was cognitive strategies, which included positive thinking (10), and spiritual coping (9). As an example of the type of strategy reported in this category, one participant discussed how he dealt with distress associated with not being employed:

So I was feeling, like, messed up. Like why I'm here. I was like that, but then I got my book. I got an NA book and Just for Today book. And I just, like, when I read, like a Scripture or like a book half opens, whatever on that page, then I just, like meditate…

The last category of problem-centered coping responses reported by participants was seeking social support (15 instances). This category included receiving support from family members and friends (13), and non-professional support groups (2). For example, one participant discussed dealing with depression by seeking social support from a consumer-operated drop-in center:

If it wasn't for the Drop-In Center, I … I don't… I don't think I'd leave the bed Saturday or Sunday, I'd stay in the bed cause I get so depressed when I don't come here [professionally-led treatment program].

AVOIDANT COPING

Avoidant coping strategies were the second most frequently reported coping strategy (15 participants reported using at least one avoidant strategy). The mean number of avoidant strategies reported was 1.22 (SD=1.21), which ranged from 0 to 4 Within this main category of avoidant coping, there were five subcategories reported by participants including, substance use (8), leaving/avoiding the stressful environment/situation (7), ignoring medical advice (4), acting out aggressively (4), and isolation (2).

The most frequently discussed avoidant coping strategy was substance use. Participants typically discussed using substances in response to being overwhelmed by major life stressors. For example, one participant explained how she started abusing alcohol after the death of an aunt she lived with and cared for:

I started drinking trying to get it out of my mind. Cause I…I didn't want to think about it. Uh, so I just started drinking then you know, it was, you know, it was still there.

With regard to leaving stressful situations, participants often discussed walking away as a strategy that they used when they became overwhelmed by a particular stressor. For example, one participant talked about how he would walk away whenever he became overwhelmed at the shelter where he was living:

I leave a lot because I can't take it. You know, I find, like right now it's getting cold out, I don't know what I'm gonna do, cause at one time I would leave and be walking about and stuff like that, because that's one of my favorite pastimes and it allows me to, you know to get away from the hustle and bustle and all the noise and all the people, cause I have a tendency…that I …when its too many people at the same time I get confused.

In a related manner, some participants discussed their use of isolation as a strategy to deal with unpleasant feelings. One participant discussed isolating himself in order to cope with depressive symptoms:

There was times where I stayed in bed for weeks and weeks at a time and just got up to go to the bathroom … get back in bed and watch TV, I didn't care, I really, really didn't care.

Several of the participants (4) reported acting out aggressively in response to various types of stressors, particularly those involving difficulties within interpersonal relationships. Two participants explained that due to stressful relationships with their intimate partners, they became physically abusive as a means of coping with this frustration. One participant stated:

I got into I just blacked out one day on my friend. He put his hands on my the wrong way and I just blacked out and started beating him with my keys and they couldn't control me the cops came and they couldn't control me, so they admitted me here to Crisis and they sedated me.

NEUTRAL COPING

Less frequently, participants reported using neutral coping in response to various types of stressors (9 participants reported using at least one neutral coping strategy). The average number of neutral coping strategies reported by participants was .37 (SD = .74), and included three subcategories: acceptance, ignoring and cognitive distraction.

Some participants discussed their use of acceptance to deal with situations in which they felt they were unable to make a change in the stressor at that particular moment. Describing how he dealt with an insulting interaction with a staff member at the shelter where he was living, one participant said:

just let it go man, just trying to um, get somewhere, you know what I mean, get somewhere, maybe wherever I get I can help me out, you know what I mean? Maybe one day I could confront that man …And I could ask him why did he say that to me?

Similar to acceptance, participants reported ignoring specific stressors that they lacked control over or were not capable of effectively changing. One participant explained that, due to a history of verbal disagreements with his stepfather, he ignores any insulting comments that may frustrate him in order to circumvent potential altercations. Additionally, some participants reported using cognitive distraction (4) in order to mollify the emotional distress related to specific stressors. These participants discussed replacing particular thoughts concerning the stressor with more pleasant memories or optimistic thought processes.

INTERACTION BETWEEN STRESS AND COPING

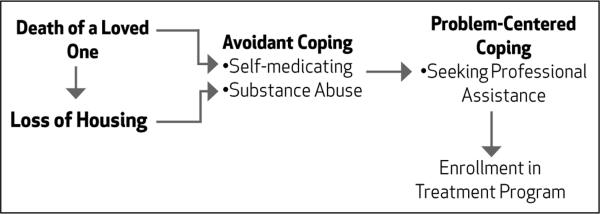

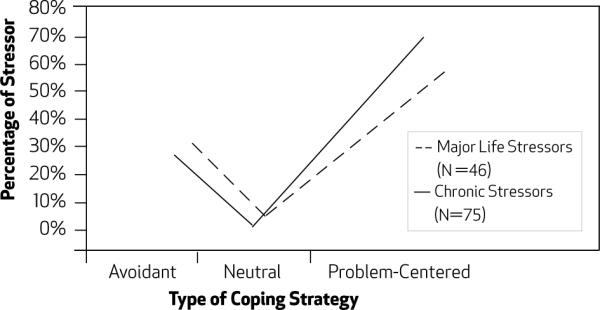

An additional concern of our study was not just to explore the types of stressors experienced by participants and the utility of specific coping responses, but also to better understand how coping varies according to the context of the stressor. Figure 1 illustrates the association between specific types of stressors and coping strategies. As indicated in Figure 1, in contrast with chronic stressors, participants tended to use avoidant and neutral coping strategies more often in response to major life stressors. Furthermore, while more problem-centered strategies were used to deal with these stressors overall, many participants reported initially using avoidant strategies, such as drug and alcohol use, which often had destructive effects that were subsequently managed with more problem-centered strategies.

Fig 1.

Relationships between Stressors and Coping Strategies

Notably, within some narratives (4), a pattern was revealed regarding the relationship between particular types of major life events, including sudden death of a loved one and loss of housing, and the use of coping strategies. Figure 2 demonstrates this temporal pattern involving substance abuse and the eventual enrollment in a treatment program in response to some major life stressors. For example, one participant poignantly discussed how the sudden death of her son led to a major depressive episode and an escalation in drug-use, followed by the initiation of enrollment in a treatment program:

[referring to son's death] Tragic. And um, I tried to kill myself. Put in the psych ward. The depression. Tried to get hit by a car, cut my wrists. I wanted to be with him so bad. I wasn't sleeping, I wasn't eating. I was going places where I had no business going, thinking that somebody would hurt me. I just got a bit better with it. My family was worried about me. I was, like, missing for, like, after that I was missing for two weeks. And my drug use was escalated…

First I was in the hospital. I was talking to [treatment program representative]. She kept telling me, well, she said something about this program here. And she wanted me to come. And I said, yeah, I'll be there. She said, if you don't come I'm gonna come get you. And I said, you don't know me cuz if I don't wanna do it, I'm not gonna do it. But I came. I came one day. I came two days. And then I didn't come back. But then I thought about it. When I did come here, the positive thing I was doing, that was different from going sitting around trying to get drugs, or trying to find a date, or just sitting in somebody's house watching TV. Or just doing nothing. I would stand on the corner freezing to death or whatever. Maybe it's my turn once again to better myself. So I came back. And I asked for help.

Fig 2.

Interaction between Major Life Stressors and Coping Strategies

DISCUSSION

The present study yielded several important findings regarding the relationship between stress and coping among adults with SMI. Consistent with previous studies, participants in this study reported experiencing a substantial number of stressors that can disrupt functioning and psychological well-being. Many of the participants reported experiencing disruptive major life events including the sudden death of a loved one, loss of housing and criminal victimization. Although we were unable to determine whether these experiences are unique to this population, the high frequency of these reported stressors is consistent with previous literature indicating persons with SMI may be at an increased risk of problems such as poor health and criminal victimization (6, 16).

Regarding chronic stressors, while a number of participants reported dealing with psychiatric symptoms and substance abuse issues, substandard living conditions, legal problems, pervasive family conflict and health concerns were also frequently discussed. Overall, this is consistent with the view that much of the stress experienced by adults with SMI is related to “institutionalized poverty,” and that psychiatric symptoms are only one aspect of what compromises functioning and well-being in this population (15, 22). Additionally, this finding corresponds to previous literature suggesting the family discord and lack of family support, which may affect psychiatric recovery and relapse, are prevalent among people with SMI (23).

With regard to coping, findings suggested that adults with SMI use problem-centered coping strategies most frequently in response to a majority of stressors. One of the most commonly reported problem-centered coping strategies, in response to both types of stressors, was the use of community mental services and obtaining support from treatment providers. Indeed, many of the participants relied heavily on their independent counselors, group members and case workers, emphasizing the importance of service providers in coping with particular stressors.

While avoidant coping strategies were infrequently applied, data suggested that these techniques, specifically substance use, are more likely to be used in response to major life stressors than to chronic stressors, and that the use of these strategies may have detrimental effects on psychiatric stability and community functioning. Since our data allowed us to evaluate the sequence of events over time, it was also noted that there was a tendency for problem-centered strategies to also be employed in response to major life events, after the initial application of avoidant coping techniques.

One way to make sense of the impact of major life stressors and the tendency to use avoidant strategies in response to them is within the context of the literature on the “reactivity” to stress of persons with psychotic disorders (24). This research has found that persons with psychotic disorders tend to respond with greater sensitivity to daily stress than community controls. Major life stressors, especially when unexpected, may be particularly damaging when considered in this light, and may place a considerable demand on coping resources that many may find difficult to manage.

Identifying the types of stressors and the manner in which persons with SMI cope with these experiences provides several implications for the enhancement of community mental services and future research in this area. First, it is evident that persons with SMI experience a wide range of challenging stressors, including both major life events and chronic strains, and that these stressors may be inter-related and may affect psychiatric stability. On a basic level, service providers need to become aware that psychiatric symptoms are only one of the pressing issues experienced by people with SMI, and that it is essential to support clients in addressing their non-psychiatric concerns. Further, due to the potential effect these external demands may have on symptom severity and an individual's ability to manage a psychiatric disability in conjunction with maintaining community functioning, more emphasis should be placed on decreasing possible exposure to these stressors. Focusing energy on ways to resolve these issues by addressing health, family problems and housing conditions may reduce the amount of chronic stress experienced by people with SMI and increase the effectiveness of community mental health services. Second, although many of the participants in this study used adaptive coping strategies such as problem-solving and reliance on social support, this may be a result of their involvement in treatment, particularly illness management services. Many adults with SMI apparently acquire the skills necessary to effectively cope with some stressors. It is essential that community mental health service providers collaborate with consumers in a process of mutual education, so that effective coping techniques in response to relevant chronic stressors and psychiatric symptoms can be identified and disseminated. By listening to consumers, providers may identify new types of coping strategies that can then be incorporated into professionally-led interventions. Additionally, it may be beneficial for service providers to specifically emphasize coping with infrequent but predictable major life events (such as the death of a loved one) to increase the likelihood that adults with SMI will be better prepared to apply problem-centered coping strategies as opposed to avoidant techniques if these events occur.

In considering the relevance of the findings from the present study, it should be noted that, despite a relatively large body of quantitative research examining the use of coping strategies among persons with SMI (4), to our knowledge no previous study has explored this area using detailed narratives, and previous studies have made little effort to examine the context in which coping strategies are used or the sequence in which they are applied. The use of qualitative methods in the present study provides a comprehensive and unique understanding of the types of stressors and coping strategies experienced in this population which may consequently assist in the development of more nuanced individualized therapeutic interventions.

Some limitations of the present study should be noted. Since participants were selected from treatment programs in impoverished urban areas with a heavy concentration of substance use issues, and were required to be enrolled in an Illness Management program, the findings may have been affected, and the sample may not be representative of the SMI population in general. Furthermore, coping strategies may have been influenced by the participants' involvement in Illness Management and therefore may not be reflective of the strategies that might be reported by consumers who are not participating in such services. Moreover, since interviews generally took place in treatment settings, social desirability may have impacted participants' responses.

Nevertheless, the findings of this study may be used as a foundation to further explore or create additional questions in this area that may be assessed on a quantitative level. Future research should examine the issue of stress and coping in a larger sample of adults with SMI, including those who are not attending treatment, in order to increase the generalizability of these findings. Since coping mechanisms may be connected with community functioning, it would be beneficial to examine additional interventions that may decrease the use of maladaptive coping strategies and enhance the psychiatric stability of adults with SMI. Finally, although this study suggested that some types of major life and chronic stressors are frequently reported by adults with SMI, due to our lack of a community comparison group we are unable to discern whether these stressors and coping responses are also common among persons without psychiatric disabilities. Further exploration investigating the prevalence of such stressors and the coping strategies applied in response to them among other populations, especially those of similar SES, is warranted.

Acknowledgements

Preparation of this manuscript was supported by a grant from the National institute of Mental Health (k23MH066973) given to Dr. Philip Yanos.

References

- 1.Carling PJ. Return to community: Building support systems for people with psychiatric disabilities. Guilford; New York: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wong YL, Solomon PL. Community integration of persons with psychiatric disabilities in supportive independent housing: A conceptual model and methodological considerations. Ment Health Serv Res. 2002;4:13–28. doi: 10.1023/a:1014093008857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yanos PT, Moos RH. Determinants of functioning and well-being among individuals with schizophrenia: An integrated model. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:58–77. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roe D, Yanos PT, Lysaker PH. Coping with psychosis: An integrative developmental framework. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;94:917–924. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000249108.61185.d3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chernomas WM, Clarke DE, Chrisholm FA. Perspectives of women living with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1517–1521. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.12.1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kelly BD. Structural violence and schizophrenia. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61:721–730. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Link BG, Struening EL, Neese-Todd S, Asmussen S, Phelan JC. Stigma as a barrier to recovery: The consequences of stigma for the self-esteem of people with mental illnesses. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1621–1626. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.12.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thoits PA. Stress, coping, and social support processes: Where are we? What next? J Health Soc Behav Spec no. 1995:53–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wheaton B. The domains and boundaries of stress concepts. In: Kaplan HI, editor. Psychosocial stress: Perspectives on structure, theory, life-course, and methods. Academic; San Diego: 1996. pp. 29–70. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bebbington P, Wilkins S, Jones P, Forester A, Murray R, Toone B, Lewis S. Life events and psychosis: Initial results from the Camberwell collaborative psychosis study. Br J Psychiatry. 1993;162:72–79. doi: 10.1192/bjp.162.1.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bebbington P, Wilkins S, Sham P, Jones P, Van Os J, Murray R, Toone B, Lewis S. Life events before psychotic episodes: Do clinical and social variables affect the relationship? Soc Psych Psych Epid. 1996;31:122–128. doi: 10.1007/BF00785758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Serido J, Almeida DM, Wethington E. Chronic stressors and daily hassles: Unique and interactive relationships with psychological distress. J Health Soc Behav. 2004;45:17–33. doi: 10.1177/002214650404500102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McLeod JD, Kessler RC. Socioeconomic status differences in vulnerability to undesirable life event. J Health Soc Behav. 1990;31:162–172. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turner RJ, Wheaton B, Lloyd DA. The epidemiology of social stress. Am Sociol Rev. 1995;60:104–125. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yanos PT, Knight EL, Roe D. Recognizing a role for structure and agency: Integrating sociological perspectives into the study of recovery from severe mental illness. In: McLeod J, Pescosolido B, Avison W, editors. Mental health, social mirror. Springer; New York: 2007. pp. 407–433. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Teplin LA, McClelland GM, Abram KM, Weiner DA. Crime victimization in adults with severe mental illness. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:911–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.8.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phillips LJ, Francey SM, Edwards J, McMurray N. Stress and psychosis: Toward the development of new models of investigation. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:307–317. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mueser KT, Corrigan PW, Hilton DW, Tanzman B, Schaub A, Gingerich S, Essock SM, Tarrier N, Morey B, Vogel-Scibilia S, Herz MI. Illness management and recovery: A review of the research. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:1272–1284. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.10.1272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Spradley JP. The ethnographic interview. Wadsworth; Belmont, Cal.: 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Strauss A, Corbin JM. Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage; Thousand Oaks, Cal.: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yanos PT, Knight EL, Bremer L. A new measure of coping with symptoms for use with persons diagnosed with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2003;27:168–176. doi: 10.2975/27.2003.168.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Draine J, Salzer MS, Culhane DP, Hadley TR. Role of social disadvantage in crime, joblessness, and homelessness among persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53:565–573. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.5.565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrowclough C, Hooley JM. Attributions and expressed emotion: A review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2003;23:849–880. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(03)00075-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Myin-Germeys I, Peeters P, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, DeVries MW, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: An experience sampling study. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2003;107:124–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]