Abstract

The accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) lumen triggers ER stress. ER stress initiates a number of specific compensatory signaling pathways including unfolded protein response (UPR). UPR is characterized by translational attenuation, synthesis of ER chaperone proteins such as glucose-regulated protein of 78 kDa (GRP78, also known as Bip), and transcriptional induction, which includes the activation of transcription factors such as activating transcriptional factor 6 (ATF6) and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP, also known as growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 [GADD153]). Sustained ER stress ultimately leads to cell death. ER functions are believed to be impaired in various neurodegenerative diseases, as well as in some acute disorders of the brain. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a member of the neurotrophin family, functions as a neuroprotective agent and rescues neurons from various insults. The molecular mechanisms underlying BDNF neuroprotection, however, remain to be elucidated. We showed that CHOP partially mediated ER stress-induced neuronal death. BDNF suppressed ER stress-induced upregulation/nuclear translocation of CHOP. The transcription of CHOP is regulated by ATF4, ATF6, and XBP1; BDNF selectively blocked the ATF6/CHOP pathway. Furthermore, BDNF inhibited the induction of death receptor 5 (DR5), a transcriptional target of CHOP. Our study thus suggests that suppression of CHOP activation may contribute to BDNF-mediated neuroprotection during ER stress responses.

Keywords: cell death, endoplasmic reticulum stress, neurodegeneration, neuroprotection, neurotrophic factor

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an important subcellular compartment involved in posttranslational protein processing and transport. Approximately one-third of all cellular proteins are translocated into the lumen of the ER where posttranslational modification, folding, and oligomerization occur. The ER is also the site for the biosynthesis of steroids, cholesterol, and other lipids. Many disturbances, such as perturbed calcium homeostasis or cellular redox status, elevated secretory protein synthesis rates, altered glycosylation levels, and cholesterol overloading, can interfere with protein folding. This can lead to the accumulation of unfolded or misfolded proteins in the ER lumen and activate a compensatory mechanism, which has been referred to as ER stress responses (Kaufman, 1999; Ron, 2002). Unfolded protein response (UPR) is one of the ER stress responses. The initial intent of UPR is to adapt to the changing environment, and reestablish normal ER function. These protective responses are characterized by an overall decrease in translation, enhanced protein degradation, induction of gene transcription and increased levels of ER chaperones, which consequently increase the protein folding capacity of the ER. During UPR, multiple signaling pathways are activated in a coordinative manner. These include the activation of double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase (PKR), the PKR-like ER kinase (PERK) and eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha (eIF2α), all of which suppress the initiation step of protein synthesis; UPR is also characterized by the synthesis of ER chaperone proteins such as glucose-regulated protein of 78 kDa (GRP78, also known as Bip) and the activation of transcription factors such as activating transcriptional factor (ATF6) and C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP, also known as growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153 (GADD153) (Kaufman, 1999; Ron, 2002; Rao et al., 2004). Sustained ER stress ultimately leads to cell death, however, usually in the form of apoptosis (Rutkowski and Kaufman, 2004; Xu et al., 2005). Many neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer, Huntington or Parkinson diseases, are associated with the pathological accumulation of protein aggregates, such as β-amyloid, huntingtin, or α-synuclein (Forloni et al., 2002; Shastry, 2003; Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). ER calcium homeostasis and ER functions are believed to be impaired in these neurodegenerative diseases as well as some acute disorders of the brain, such as cerebral ischemia (Paschen, 2003; Paschen and Mengesdorf, 2005).

Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), a member of the neurotrophin family, regulates development, maintenance, plasticity, and function of the nervous system (Huang and Reichardt, 2001; Binder and Scharfman, 2004). In vitro and in vivo studies indicate that BDNF can function as a neuroprotective agent and rescues neurons from various insults (Garcia de Yebenes et al., 2000; Huang and Reichardt, 2001). For example, BDNF offers neuroprotection in animal models of cerebral ischemia (Han and Holtzman, 2000; Zhang and Pardridge, 2001), Parkinson (Sun et al., 2005), and Huntington diseases (Bemelmans et al., 1999; Alberch et al., 2002; Canals et al., 2004). The mechanisms underlying BDNF neuroprotection, however, remain to be elucidated.

In this study, we showed that CHOP partially mediates ER stress-induced neuronal death. BDNF suppresses CHOP production during ER stress and rescues cells from ER stress-induced cell death.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Tunicamycin (Tun), thapsigargin (Tha), retinoic acid (RA), tetracycline (Tet), and anti-actin antibody were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). The antibodies directed against CHOP, GRP78, ATF4, ATF6 (N-terminal), and eIF2α were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-XBP1 antibody was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). Anti-histone H3 antibody was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Anti-death receptor 5 (anti-DR5) antibody was purchased from Chemicon International, Inc. (Temecula, CA), and anti-phospho-eIF2α and eIF2α antibodies were obtained from Biosource International, Inc. (Camarillo, CA).

Cell Culture

Human neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA) were grown in Eagle's minimal essential medium (MEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM L-glutamine and 25 μg/ml gentamicin, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin at 37°C with 5% CO2. SH-SY5Y cells expressing inducible TrkB (TB8 cells) under the control of a Tet-repressible promoter element were maintained as described previously (Chen et al., 2004). CHOP+/+ and CHOP−/− mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) were obtained from Dr. David Ron (Skirball Institute of Biomolecular Medicine, NY) and maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% FBS and penicillin–streptomycin (100 units/ml-100 μg/ml) at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cultures of cerebellar granule neurons (CGNs) were generated using a method described previously (Chen et al., 2004). The CGNs were derived from the cere-bella of 6- or 7-day-old rat pups.

Determination of Cell Number

Cell viability was determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay as previously described (Chen et al., 2004). The assay is based on the cleavage of the yellow tetrazolium salt MTT to purple formazan crystals by metabolically active cells. Briefly, the cells were plated into 96-well microtiter plates. After treatments, 10 μl of MTT labeling reagent were added to each well and the plates were incubated at 37°C for 4 hr. The cultures were then solubilized and spectrophotometric absorbance of the samples was detected by a microtiter plate reader. The wavelength to measure absorbance of formazan product is 570 nm, with a reference wavelength of 750 nm. In addition, cell number was also determined by manual counting under a phase-contrast microscope as described previously (Luo et al., 1999).

Preparation of Cell Lysates of Whole-Cell, Cytoplasmic, and Nuclear Fractions

For lysates of whole cells, cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH 7.4) and lysed with RIPA buffer (150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris [pH 8.0], 1% Nonidet P-40 [NP-40], 0.1% sodium dodecylsulfate [SDS], 0.5% deoxycholic acid sodium, 0.1 mg/ml phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, and 3% aprotinin) on ice for 10 min, solubilized cells were centrifuged, and the supernatant was collected and designated as the whole-cell lysate. For extraction of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions, cells were lysed in PBS that contained 5 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA), 1% NP-40, 1 mM DTT (Sigma), 10 μg/ml leupeptin (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN), and 1 mM Pephabloc SC (Roche Diagnostics). After 5-min incubation on ice, the lysate was centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was designated the cytoplasmic fraction. The pelleted nuclei were sonicated in nuclear extraction buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 1% SDS, 5 mM EGTA, 0.5% Triton X-100, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 10 mg/ml leupeptin, and 1 mM Pephabloc SC) and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm for 5 min. The supernatant was collected and designated the nuclear fraction.

Immunoblotting

The immunoblotting procedure has been described previously (Chen et al., 2004). Briefly, after protein concentrations were determined, aliquots of the protein samples (20–40 μg) were loaded into the lanes of a SDS-polyacrylamide gel. The protein samples were separated by electrophoresis, and the separated proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) or 5% nonfat milk in 0.010 M PBS (pH 7.4) and 0.05% Tween-20 (TPBS) at room temperature for 1 hr. The membranes were then probed with primary antibodies directed against target proteins for 2 hr at room temperature or overnight at 4°C. After three quick washes in TPBS, the membranes were incubated with a secondary antibody conjugated to horseradish peroxidase (Amersham; Arlington Hts. IL) diluted at 1:2,000 in TPBS for 1 hr. The immune complexes were detected by the enhanced chemiluminescence method (Amersham). In some cases, the blots were stripped and re-probed with either an anti-actin or an anti-histone H3 antibody. The density of immunoblotting was quantified with the software of Quantity One (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). The expression of target proteins was normalized to the levels of either actin or histone H3.

Immunocytofluorescent Staining of CHOP

Retinoic acid (RA)-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were cultured on cover slips. Immunocytofluorescent staining of CHOP was carried out as described previously (Ayoub et al., 2005). After incubation with an anti-CHOP antibody (1:200) overnight at 4°C, cultures were treated with a fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) secondary antibody (1:500 dilution in PBS; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Nuclei were labeled with DAPI (1 μg/ml in PBS). Images of fluorescence were acquired using the Zeiss LSM 510 META confocal laser-scanning microscope (Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany). The same settings for filters, pinhole size, stack size, and resolution were used for all captured images. Negative controls were carried out by omitting the primary antibody.

Small Interfering RNA Transfection

CHOP small interfering (si)RNA (Cat. No. 146321; Ambion, Inc., Austin, TX) or Silencer Negative Control siRNA (Cat. No. 4611; Ambion, Inc.) was transfected into SH-SY5Y cells with either Oligofectamine reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) or Nucleofector (Amaxa Inc., Gaithersburg, MD) according to the manufacturer's protocol. At 48 hr after transfection, the cells were subjected to immunoblotting analysis for CHOP expression.

Statistical Analysis

Differences among treatment groups were tested using analysis of variance (ANOVA). Differences in which P was less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. In cases where significant differences were detected, specific post-hoc comparisons between treatment groups were examined with Student-Newman-Keuls tests.

RESULTS

BDNF Protects Neuronal Cells Against Tunicamycin-Induced Cell Death

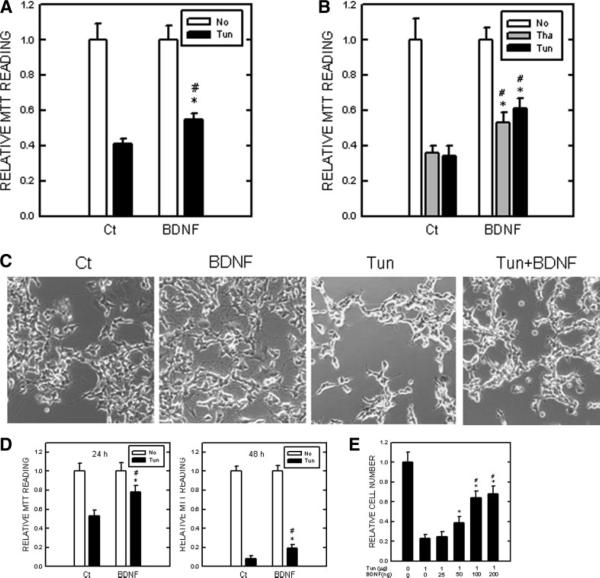

Tunicamycin and thapsigargin are the most commonly used pharmacologic agents to experimentally induce ER stress (Breckenridge et al., 2003). Tunicamycin inhibits N-linked glycosylation; thapsigargin disrupts ER Ca2+ stores. We sought to determine whether BDNF can protect neuronal cells against ER stress-induced cell death. As shown in Figure 1A, BDNF offered a partial protection against tunicamycin-induced death of cerebellar granule neurons. We have shown previously that tunicamycin and thapsigargin induced ER stress and caused apoptosis of SH-SY5Y cells (Chen et al., 2004). SH-SY5Y cells express low levels of TrkB, a high-affinity receptor for BDNF. TrkB can be induced in SH-SY5Y cells by treatment with RA (Ruiz-Leon and Pascual, 2003). We have verified that SH-SY5Y cells expressed high levels of TrkB after a 6-day treatment of RA (data not shown). BDNF significantly protected tunicamycin and thapsigargin-induced death of RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 1B). Figure 1C is a micrograph showing the effect of tunicamycin and BDNF on RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. TB8 cells are SH-SY5Y cells expressing inducible TrkB under the control of the Tet-off system (Jaboin et al., 2002). We have used these cells previously to study TrkB-mediated signaling and the protective effect of BDNF on 6-OHDA toxicity (Chen et al., 2004; Li et al., 2004). Using MTT assay, we showed that tunicamycin caused death of TB8 cells and BDNF significantly protected TB8 cells against tunicamycin-induced cell death (Fig. 1D). To verify the results obtained from MTT assay, we determined the protective effect of BDNF using manual counting under the microscope. Our results indicated that BDNF produced a dose-dependent protection and maximal protection was achieved at the concentration 100 ng/ml (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Effect of BDNF on ER stress-induced cell death. A: Cultured cerebellar granule neurons were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for 48 hr. Cell viability was determined by MTT. The protective effect of BDNF on Tun-induced cell death was normalized using BDNF-treated cells as controls. Each data point (± standard error of mean [SEM]; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from matched controls (BDNF without Tun). #Significant difference from cultures that were treated with Tun without BDNF. B: SH-SY5Y cells were differentiated by treatment of retinoic acid (RA; 1 μM) for 6 days. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) or Tha (0 or 1 μM) for 48 hr. Cell viability was determined by MTT. The protective effect of BDNF on Tun-induced cell death was normalized using BDNF-treated cells as controls. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from matched controls (BDNF without Tun or Tha). #Significant difference from cultures that were treated with Tun or Tha but without BDNF. C: The micrographs show the effect of Tun and BDNF on RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells. D: TB8 cells were cultured in Tet-free medium for 48 hr. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for 24 or 48 hr. Cell viability was determined by MTT. The protective effect of BDNF on Tun-induced cell death was normalized using matched BDNF-treated cells (24 or 48 hr) as controls. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from matched controls (BDNF without Tun). #Significant difference from cultures that were treated with Tun without BDNF. E: TB8 cells were cultured in Tet-free medium for 48 hr. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0, 25, 50, 100, or 200 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for 48 hr. Cell number was determined by counting under the microscope. The protective effect of BDNF on Tun-induced cell death was normalized using BDNF-treated cells as controls. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from cultures treated with Tun and BDNF (0 or 25 ng/ml). #Significant difference from cultures treated with Tun and BDNF (0, 25, 50 ng/ml).

BDNF Suppresses Tunicamycin-Induced CHOP Upregulation and Nuclear Translocation

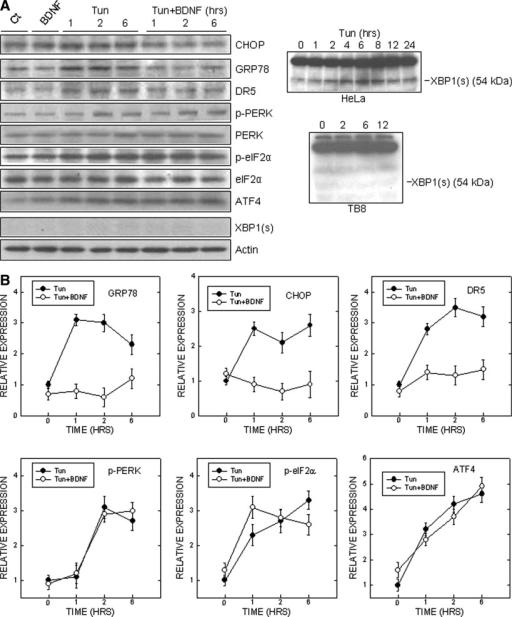

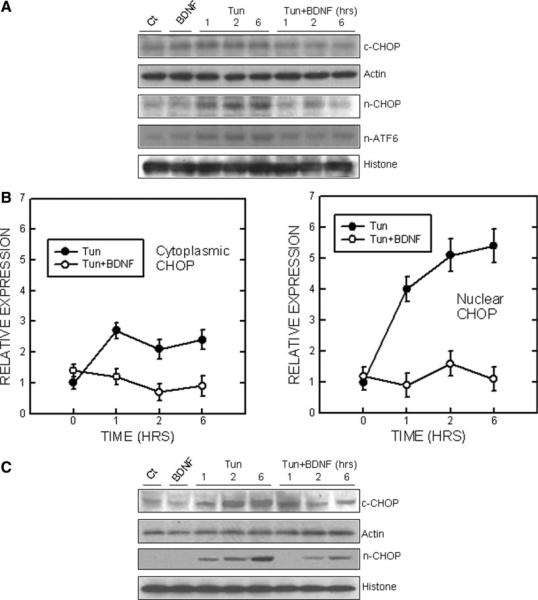

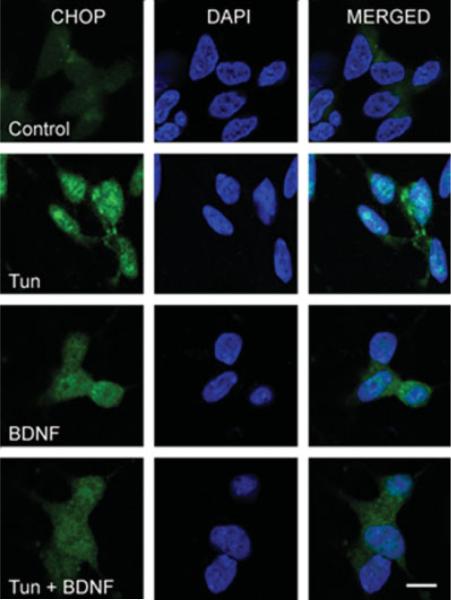

We have shown previously that tunicamycin triggered the expression of a number of markers for ER stress, such as CHOP, GRP78, and p-eIF2α in SH-SY5Y cells (Chen et al., 2004). As shown in Figure 2, tunicamycin induced the expression of these markers for ER stress in TB8 cells. BDNF suppressed tunicamycin-induced upregulation of GRP78 (Fig. 2). In addition, BDNF abolished tunicamycin-induced CHOP upregulation (Fig. 2). We further determined the subcellular distribution of CHOP. Tunicamycin increased both cytoplasmic and nuclear CHOP in TB8 cells (Fig. 3A, B). It was noted that tunicamycin-induced upregulation of nuclear CHOP was much greater than that of the cytoplasmic fraction. For example, after a 6-hr treatment, tunicamycin increased cytoplasmic CHOP by about 2.5-fold, whereas it upregulated nuclear CHOP by 5.4-fold, indicating that tunicamycin treatment caused nuclear translocation of CHOP. BDNF not only decreased cytoplasmic CHOP, but also inhibited the nuclear translocation of CHOP (Fig. 3A, B). A similar effect of BDNF on cytoplasmic and nuclear CHOP was observed in SH-SY5Y cells (Fig. 3C). BDNF-mediated suppression of CHOP expression and nuclear translocation was verified by the immunocytochemistry (Fig. 4). CHOP is a transcription factor; a recent study indicates that DR5 is a target gene of CHOP (Yamaguchi and Wang, 2004). Consistent with the profile of CHOP upregulation, DR5 expression was increased markedly by tunicamycin treatment; this upregulation was also significantly suppressed by BDNF (Fig. 2). The transcription of CHOP was regulated by ATF4, spliced XBP1, and ATF6 (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). We therefore examined the expression of these CHOP regulators. As shown in Figure 2, tunicamycin stimulated the phosphorylation of PERK and eIF2α; however, BDNF did not decrease tunicamycin induction of p-PERK and p-eIF2α. The expression of ATF4, a downstream transcription factor of eIF2α, was also unaffected by BDNF. Tunicamycin did not induce the spliced form of XBP1 (54 kDa) in SH-SY5Y and TB8 cells (Fig. 2). As a positive control, tunicamycin-mediated XBP1 splicing was evident in HeLa cells. Tunicamycin-mediated ATF6 activation, however, was inhibited significantly by BDNF (Fig. 3). The activated ATF6, which was detected by an antibody directed against the N-terminal of ATF6, translocated to the nucleus after tunicamycin treatment. BDNF suppressed tunicamycin-induced accumulation of activated ATF6 in the nucleus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Effect of BDNF on Tun-induced expression of markers for ER stress. A: Right: TB8 cells were cultured in Tet-free medium for 48 hr to induce TrkB expression. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and exposed to Tun (0 or 3 μg/ml) for specified times. Whole-cell lysates were collected and the expression of markers for ER stress was examined with immunoblotting. To ensure equal loading, the blots were stripped and reprobed with an anti-actin antibody. Left: A positive control shows Tun-mediated XBP1 splicing in HeLa cells. B: The relative amounts of GRP78, CHOP, phospho-PERK, phospho-eIF2α, ATF4, XBP1, and DR5 were measured microdensitometrically and normalized to the expression of actin. The experiment was replicated three times.

Fig. 3.

Effect of BDNF on Tun-mediated ATF6 activation and CHOP expression/distribution. A: TB8 cells were cultured in Tet-free medium for 48 hr. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 3 μg/ml) for specified times. Cytoplasmic and nuclear proteins were collected, and expression of CHOP in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions was determined by immunoblotting. The active form of ATF6 in nuclear fractions was also determined. B: The relative amounts of CHOP and activated ATF6 in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions were measured microdensitometrically and normalized to the levels of either actin or histone H3. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. C: RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were treated as described above and the expression of CHOP in cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions was determined by immunoblotting.

Fig. 4.

Analysis of subcellular distribution of CHOP by immunocytochemistry. RA-differentiated SH-SY5Y cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr. Cells were then exposed to Tun (0 or 3 μg/ml) for 4 hr. The expression of CHOP (green) was examined with immunocytochemistry as described under the Materials and Methods. The nuclei (blue) were visualized with DAPI staining. Bar = 10 μm.

BDNF-Mediated Protection Is Through the Suppression of CHOP Expression

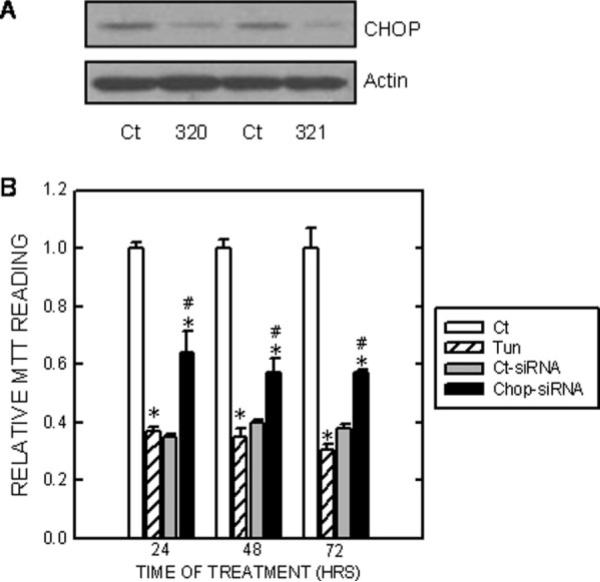

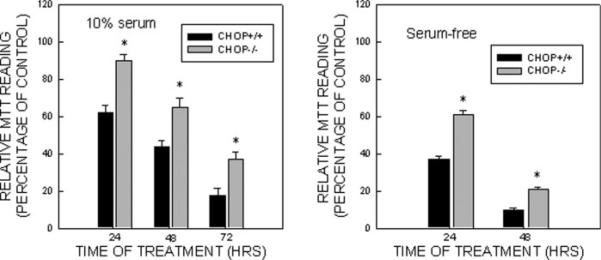

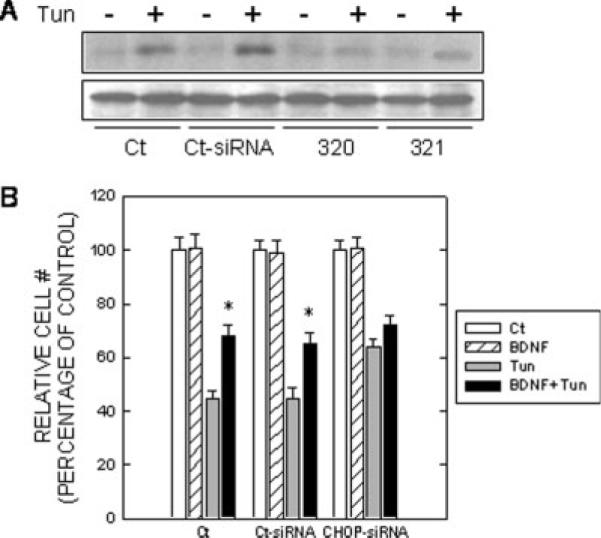

CHOP is known for its role in the regulation of the cell cycle and cell survival (Wang et al., 1996; Zinszner et al., 1998). Because BDNF markedly suppressed tunicamycin-induced expression/nuclear translocation of CHOP, we sought to determine whether CHOP mediates tunicamycin-induced cell death. We used CHOP siRNA to knock down the expression of CHOP in SH-SY5Y cells. As shown in Figure 5A and Figure 7A, two CHOP siRNAs (320 and 321) effectively suppressed the expression of CHOP. More importantly, the CHOP siRNA significantly rescued SH-SY5Y and TB8 cells from tunicamycin-induced cell death (Fig. 5B). Data for TB8 cells were not shown. In addition, we showed that CHOP null mouse embryo fibroblast cells (CHOP−/−) were more resistant to tunicamycin-induced cell death than were cells expressing wild-type CHOP (CHOP+/+ Fig. 6). To establish further the role of CHOP in BDNF-mediated protection, we evaluated the effect of BDNF on tunicamycin-induced death of cells that were pretreated with either a control siRNA or CHOP siRNA. As shown in Figure 7, BDNF failed to provide further protection against tunicamycin-induced death of cells pretreated with a CHOP siRNA, indicating that BDNF-mediated protection mainly was through the suppression of CHOP expression.

Fig. 5.

Effect of CHOP siRNA on Tun-induced cell death. A: SH-SY5Y cells were transfected with either CHOP siRNAs (#320 and #321) or control siRNA (Ct-siRNA) for 48 hr. After that, the expression of CHOP was examined with immunoblotting. B: After transfection with CHOP siRNA or control siRNA (Ct-siRNA) for 48 hr, cells were treated with Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for specified times. Cell viability was determined by MTT as described above. Cell number was expressed relative to controls that received no Tun treatment. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from controls that received no Tun treatment. #Significant difference from cultures that were treated with Tun but without CHOP siRNA.

Fig. 7.

Effect of CHOP siRNA on Tun-induced cell death. A: TB8 cells cultured in Tet-free medium were transfected with either CHOP siRNAs (#320 and #321) or control siRNA (Ct-siRNA) for 24 hr. After that, cells were pretreated with BDNF (0 or 100 ng/ml) for 24 hr and then exposed to Tun (0 or 3 μg/ml) for 6 hr. The expression of CHOP was examined with immunoblotting. B: After transfection with CHOP siRNA or control siRNA (Ct-siRNA) for 48 hr, cells were treated with Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for 24 hr. Cell number was determined by counting under the microscope and expressed as percentage of untreated control. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from paired Tun-treated groups.

Fig. 6.

Effect of Tun on CHOP null mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) or MEFs expressing wild-type CHOP. CHOP null MEFs (CHOP−/−) and MEFs expressing wild-type CHOP (CHOP+/+) were cultured in medium containing either 10% or 0% serum. Cells were treated with Tun (0 or 1 μg/ml) for specified times and cell viability was determined by MTT. The number of viable cells was expressed as a percentage of untreated controls. Each data point (± SEM; bar) is the mean of three experiments. *Significant difference from CHOP+/+ cells.

DISCUSSION

We show here that CHOP plays a pivotal role in ER stress-induced neuronal death and BDNF suppresses the induction of CHOP by ER stress, indicating that suppression of CHOP activation may partially contribute to BDNF-mediated neuroprotection during ER stress responses.

CHOP is a 29-kDa leucine zipper transcription factor that is expressed ubiquitously at very low levels (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). It is upregulated robustly in response to various stress conditions. It is present in the cytosol under nonstressed conditions, and cellular stress leads to the induction of CHOP and its accumulation in the nucleus (Ron and Habener, 1992). Expression of CHOP is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level and is one of the highest inducible genes during ER stress (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). The transcriptional upregulation program in response to ER stress is conducted by three distinct types of ER stress transducers localized on the ER membrane, namely, PERK, ATF6, and inositol requiring enzyme (IRE1; Fig. 7). ER chaperone, GRP78 or Bip, works as a sensor of unfolded proteins in the ER and regulates the activation of these ER stress transducers. Three transcription factors, ATF4, activated ATF6, and x-box binding protein 1 (XBP1), are identified to be downstream effectors of these signaling pathways and participate in the regulation of CHOP. To achieve maximal induction of CHOP, the presence of three signaling pathways is required (Okada et al., 2002).

CHOP plays an important role in ER stress-induced apoptosis (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). Recent studies suggest that the induction of CHOP is involved in acute brain damage as well as neurodegeneration. For example, induction of CHOP mRNA is observed in the rat hippocampus subjected to global cerebral ischemia (Kumar et al., 2001). Protein misfolding has been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. The accumulation of misfolded proteins such as β-amyloid, α-synuclein, and huntingtin is apparently associated with selective neuronal cell death in Alzheimer, Parkinson, and Huntington diseases, respectively. Mutations in presenilin-1, which increases the production of β-amyloid, are shown to increase CHOP protein (Iadecola et al., 1997). The CHOP gene is induced by parkinsonism-inducing neurotoxins (Ryu et al., 2002; Holtz and O'Malley, 2003; Chen et al., 2004). A recent study shows that CHOP is a critical mediator of apoptotic death in substantia nigra dopamine neurons in an animal model of parkinsonism (Silva et al., 2005).

Our study supports that the induction of CHOP causes neuronal death by showing CHOP siRNA significantly alleviates tunicamycin-induced death of neuronal cells. Our results support further that BDNF-mediated protection mainly is through the suppression of CHOP expression. The mechanisms for CHOP regulation of cell death are not understood completely. Induction of CHOP is reported to perturb the cellular redox state by depletion of cellular glutathione (McCullough et al., 2001). On the other hand, overexpression of CHOP leads to a decrease in Bcl-2 protein and overexpression of Bcl-2 blocks CHOP-induced apoptosis (Matsumoto et al., 1996; McCullough et al., 2001). Overexpression of CHOP is also shown to induce translocation of Bax protein from the cytosol to the mitochondria (Gotoh et al., 2004). The CHOP-mediated death signal thus seems to be transmitted to the mitochondria, which functions as an integrator and amplifier of the death pathway. Recently, death receptor 5 (DR5) has been identified as a CHOP-responsive gene; the transcription of DR5 is directly regulated by CHOP (Yamaguchi and Wang, 2004). DR5 is a proapoptotic cell-surface death receptor; its overexpression sensitizes cells to apoptotic death (Kim et al., 2006). Consistent with its effect on CHOP, BDNF significantly suppresses tunicamycin-induced DR5 upregulation (Fig. 2), suggesting that suppression of CHOP may block the activation of its downstream proapoptotic effectors such as DR5.

It is unclear how BDNF suppresses tunicamycin induction of CHOP. As mentioned above, CHOP is believed to be regulated by the convergence of three distinct pathways during the ER stress response (Ma et al., 2002; Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). One pathway is through the activation of PERK, which leads to eIF2a phosphorylation and synthesis of ATF4. ATF4 in turn binds to the CHOP promoter and activates CHOP transcription. Another pathway is through the activation of ATF6. GRP78-free ATF6 is transported to the Golgi apparatus and cleaved by Site-1 and -2 proteases (S1P and S2P), which liberates the N-terminal of ATF6 (activated form of ATF6). The activated form of ATF6 translocates to the nucleus and regulates CHOP gene transcription (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). The third pathway is through the activation of IRE1. Activated IRE1 induces a spliced form of XBP1, which has transactivation potential and regulates CHOP gene transcription. In addition, ATF6 can upregulate the expression XBP1, which further stimulates CHOP gene transcription, representing a positive feedback pathway during ER stress responses (Oyadomari and Mori, 2004). Our results indicate that tunicamycin does not induce a spliced form of XBP1 in SH-SY5Y and TB8 cells. Although tunicamycin activates the PERK/eIF2a/ATF4 pathway, BDNF does not suppress the activation of this pathway. Instead, BDNF selectively inhibits the ATF6 pathway; the inhibition seems sufficient to suppress CHOP induction. This suggests ATF4 is either not involved in CHOP regulation or the activation of ATF4 alone is not sufficient to induce CHOP in our system. CHOP induction may be regulated by ATF6 or may require the activation of both ATF4 and ATF6; inhibiting one of them is sufficient to suppress CHOP induction.

BDNF is an important neurotrophic factor that regulates neuronal function and survival (Huang and Reichardt, 2001). BDNF levels are decreased in surviving neurons in some brain areas of Alzheimer and Parkinson disease (Siegel and Chauhan, 2000; Murer et al., 2001; Pezet and Malcangio, 2004) and are required for establishment of the proper number of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta (Baquet et al., 2005). BDNF is also a neuroprotective agent and promotes neuronal survival in animal models of cerebral ischemia (Han and Holtzman, 2000; Zhang and Pardridge, 2001) and in Parkinson (Garcia de Yebenes et al., 2000; Sun et al., 2005) and Huntington diseases (Bemelmans et al., 1999; Alberch et al., 2002; Canals et al., 2004). BDNF neuroprotection against ER stress-mediated damage is supported further by two in vitro studies showing that BDNF rescues neuronal cells against tunicamycin or thapsigargin-induced cell death (Shimoke et al., 2004; Zhu et al., 2004). These studies, however, do not elucidate the underlying mechanisms. BDNF represents a potential therapeutic approach for the treatment of acute brain disorders and neurodegenerative diseases. Our finding that BDNF suppresses the induction of CHOP during ER stress responses provides an insight into the mechanisms of BDNF-mediated neuroprotection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Mr. C. Feng for his assistance in confocal laser-scanning microscopy. This research was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AA015407), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30470544, 30471452, 30570580) and the Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars that is sponsored by State Education Ministry. Dr. Z.-J. Ke was also supported by the One Hundred Talents Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Dr. X. Wang was supported by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation and the Shanghai Postdoctoral Scientific Program.

Contract grant sponsor: National Institutes of Health; Contract grant number: AA015407; Contract grant sponsor: National Natural Science Foundation of China; Contract grant number: 30470544, 30471452, 30570580; Contract grant sponsor: Scientific Research Foundation for the Returned Overseas Chinese Scholars (State Education Ministry); Contract grant sponsor: Chinese Academy of Sciences; Contract grant sponsor: China Postdoctoral Science Foundation; Contract grant sponsor: Shanghai Postdoctoral Scientific Program.

Abbreviations used

- ATF6

activating transcriptional factor 6

- CHOP

C/EBP homologous protein

- DR5

death receptor 5

- eIF2α

eukaryotic translation initiation factor 2 alpha

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GADD153

growth arrest and DNA damage-inducible gene 153

- GRP78

glucose-regulated protein of 78 kDa

- IRE1

inositol requiring enzyme 1

- PKR

double stranded RNA-activated protein kinase

- PERK

PKR-like ER kinase

- UPR

unfolded protein response

- XBP1

x-box-binding protein 1

REFERENCES

- Alberch J, Perez-Navarro E, Canals JM. Neuroprotection by neurotrophins and GDNF family members in the excitotoxic model of Huntington's disease. Brain Res Bull. 2002;57:817–822. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayoub AE, Cai TQ, Kaplan RA, Luo J. Developmental expression of matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 and their potential role in the histogenesis of the cerebellar cortex. J Comp Neurol. 2005;481:403–415. doi: 10.1002/cne.20375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baquet ZC, Bickford PC, Jones KR. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor is required for the establishment of the proper number of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra pars compacta. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6251–6259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4601-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bemelmans AP, Horellou P, Pradier L, Brunet I, Colin P, Mallet J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated protection of striatal neurons in an excitotoxic rat model of Huntington's disease, as demonstrated by adenoviral gene transfer. Hum Gene Ther. 1999;10:2987–2997. doi: 10.1089/10430349950016393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Binder DK, Scharfman HE. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor. Growth Factors. 2004;22:123–131. doi: 10.1080/08977190410001723308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge DG, Germain M, Mathai JP, Nguyen M, Shore GC. Regulation of apoptosis by endoplasmic reticulum pathways. Oncogene. 2003;22:8608–8618. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canals JM, Pineda JR, Torres-Peraza JF, Bosch M, Martin-Ibanez R, Munoz MT, Mengod G, Ernfors P, Alberch J. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor regulates the onset and severity of motor dysfunction associated with enkephalinergic neuronal degeneration in Huntington's disease. J Neurosci. 2004;24:7727–7739. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1197-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen G, Bower KA, Ma C, Fang S, Thiele CJ, Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3beta) mediates 6-hydroxydopamine-induced neuronal death. FASEB J. 2004;18:1162–1164. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-1551fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forloni G, Terreni L, Bertani I, Fogliarino S, Invernizzi R, Assini A, Ribizzi G, Negro A, Calabrese E, Volonte MA, Mariani C, Franceschi M, Tabaton M, Bertoli A. Protein misfolding in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease: genetics and molecular mechanisms. Neurobiol Aging. 2002;23:957–976. doi: 10.1016/s0197-4580(02)00076-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia de Yebenes J, Yebenes J, Mena MA. Neurotrophic factors in neurodegenerative disorders: model of Parkinson's disease. Neurotox Res. 2000;2:115–137. doi: 10.1007/BF03033789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotoh T, Terada K, Oyadomari S, Mori M. hsp70-DnaJ chaperone pair prevents nitric oxide- and CHOP-induced apoptosis by inhibiting translocation of Bax to mitochondria. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:390–402. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han BH, Holtzman DM. BDNF protects the neonatal brain from hypoxic-ischemic injury in vivo via the ERK pathway. J Neurosci. 2000;20:5775–5781. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-15-05775.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holtz WA, O'Malley KL. Parkinsonian mimetics induce aspects of unfolded protein response in death of dopaminergic neurons. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:19367–19377. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211821200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang EJ, Reichardt LF. Neurotrophins: roles in neuronal development and function. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:677–736. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iadecola C, Zhang F, Casey R, Nagayama M, Ross ME. Delayed reduction of ischemic brain injury and neurological deficits in mice lacking the inducible nitric oxide synthase gene. J Neurosci. 1997;17:9157–9164. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-23-09157.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaboin J, Kim CJ, Kaplan DR, Thiele CJ. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor activation of TrkB protects neuroblastoma cells from chemotherapy-induced apoptosis via phosphatidylinositol 3′-kinase pathway. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6756–6763. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman RJ. Stress signaling from the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum: coordination of gene transcriptional and translational controls. Gene Dev. 1999;13:1211–1233. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Kim EH, Eom YW, Kim WH, Kwon TK, Lee SJ, Choi KS. Sulforaphane sensitizes tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL)-resistant hepatoma cells to TRAIL-induced apoptosis through reactive oxygen species-mediated up-regulation of DR5. Cancer Res. 2006;66:1740–1750. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Azam S, Sullivan JM, Owen C, Cavener DR, Zhang P, Ron D, Harding HP, Chen JJ, Han A, White BC, Krause GS, DeGracia DJ. Brain ischemia and reperfusion activates the eukaryotic initiation factor 2alpha kinase, PERK. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1418–1421. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Ding M, Thiele CJ, Luo J. Ethanol inhibits brain-derived neurotrophic factor-mediated intracellular signaling and activator protein-1 activation in cerebellar granule neurons. Neuroscience. 2004;126:149–162. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2004.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, West JR, Cook RT, Pantazis NJ. Ethanol induces cell death and cell cycle delay in cultures of pheochromocytoma PC12 cells. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1999;23:644–656. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Brewer JW, Diehl JA, Hendershot LM. Two distinct stress signaling pathways converge upon the CHOP promoter during the mammalian unfolded protein response. J Mol Biol. 2002;318:1351–1365. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00234-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Minami M, Takeda K, Sakao Y, Akira S. Ectopic expression of CHOP (GADD153) induces apoptosis in M1 myeloblastic leukemia cells. FEBS Lett. 1996;395:143–147. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)01016-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCullough KD, Martindale JL, Klotz LO, Aw TY, Holbrook NJ. Gadd153 sensitizes cells to endoplasmic reticulum stress by down-regulating Bcl2 and perturbing the cellular redox state. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:1249–1259. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.1249-1259.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murer MG, Yan Q, Raisman-Vozari R. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor in the control human brain, and in Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;63:71–124. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada T, Yoshida H, Akazawa R, Negishi M, Mori K. Distinct roles of activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) and double-stranded RNA-activated protein kinase-like endoplasmic reticulum kinase (PERK) in transcription during the mammalian unfolded protein response. Biochem J. 2002;366:585–594. doi: 10.1042/BJ20020391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oyadomari S, Mori M. Roles of CHOP/GADD153 in endoplasmic reticulum stress. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:381–389. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W. Endoplasmic reticulum: a primary target in various acute disorders and degenerative diseases of the brain. Cell Calcium. 2003;34:365–383. doi: 10.1016/s0143-4160(03)00139-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschen W, Mengesdorf T. Endoplasmic reticulum stress response and neurodegeneration. Cell Calcium. 2005;38:409–415. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pezet S, Malcangio M. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor as a drug target for CNS disorders. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2004;8:391–399. doi: 10.1517/14728222.8.5.391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao RV, Ellerby HM, Bredesen DE. Coupling endoplasmic reticulum stress to the cell death program. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11:372–380. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D. Translational control in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response. J Clin Invest. 2002;110:1383–1388. doi: 10.1172/JCI16784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ron D, Habener JF. CHOP, a novel developmentally regulated nuclear protein that dimerizes with transcription factors C/EBP and LAP and functions as a dominant-negative inhibitor of gene transcription. Genes Dev. 1992;6:439–453. doi: 10.1101/gad.6.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz-Leon Y, Pascual A. Induction of tyrosine kinase receptor b by retinoic acid allows brain-derived neurotrophic factor-induced amyloid precursor protein gene expression in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Neuroscience. 2003;120:1019–1026. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(03)00391-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutkowski DT, Kaufman RJ. A trip to the ER: coping with stress. Trends Cell Biol. 2004;14:20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryu EJ, Harding HP, Angelastro JM, Vitolo OV, Ron D, Greene LA. Endoplasmic reticulum stress and the unfolded protein response in cellular models of Parkinson's disease. J. Neurosci. 2002;22:10690–10698. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10690.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shastry BS. Neurodegenerative disorders of protein aggregation. Neurochem Int. 2003;43:1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0197-0186(02)00196-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimoke K, Utsumi T, Kishi S, Nishimura M, Sasaya H, Kudo M, Ikeuchi T. Prevention of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in cultured cerebral cortical neurons. Brain Res. 2004;1028:105–111. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2004.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siegel GJ, Chauhan NB. Neurotrophic factors in Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease brain. Brain Res Brain Res Rev. 2000;33:199–227. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(00)00030-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva RM, Ries V, Oo TF, Yarygina O, Jackson-Lewis V, Ryu EJ, Lu PD, Marciniak SJ, Ron D, Przedborski S, Kholodilov N, Greene LA, Burke RE. CHOP/GADD153 is a mediator of apoptotic death in substantia nigra dopamine neurons in an in vivo neurotoxin model of parkinsonism. J Neurochem. 2005;95:974–986. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03428.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun M, Kong L, Wang X, Lu XG, Gao Q, Geller AI. Comparison of the capability of GDNF, BDNF, or both, to protect nigrostriatal neurons in a rat model of Parkinson's disease. Brain Res. 2005;1052:119–129. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.05.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XZ, Lawson B, Brewer JW, Zinszner H, Sanjay A, Mi LJ, Boor-stein R, Kreibich G, Hendershot LM, Ron D. Signals from the stressed endoplasmic reticulum induce C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP/GADD153) Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4273–4280. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Bailly-Maitre B, Reed JC. Endoplasmic reticulum stress: cell life and death decisions. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:2656–2664. doi: 10.1172/JCI26373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi H, Wang HG. CHOP is involved in endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced apoptosis by enhancing DR5 expression in human carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:45495–45502. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M406933200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Pardridge WM. Neuroprotection in transient focal brain ischemia after delayed intravenous administration of brain-derived neurotrophic factor conjugated to a blood-brain barrier drug targeting system. Stroke. 2001;32:1378–1384. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu W, Bijur GN, Styles NA, Li X. Regulation of FOXO3a by brain-derived neurotrophic factor in differentiated human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2004;126:45–56. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinszner H, Kuroda M, Wang X, Batchvarova N, Lightfoot RT, Remotti H, Stevens JL, Ron D. CHOP is implicated in programmed cell death in response to impaired function of the endoplasmic reticulum. Genes Dev. 1998;12:982–995. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]