Abstract

The aim of the study was to evaluate arterial stiffness and its modulating factors measured by carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity and central augmentation index in patients with pheochromocytoma before and after surgery. Forty-five patients with pheochromocytoma and 45 healthy controls were investigated using an applanation tonometer (SphygmoCor, AtCor Medical). In addition, 27 patients with pheochromocytoma were studied one year after tumor removal. The gender, age, BMI and lipid profiles were comparable among both groups. The main difference in basic characteristic was as expected fasting plasma glucose (P<0.001) and all blood pressure modalities. Pulse wave velocity in pheochromocytoma was significantly higher than in controls (7.2±1.4 vs.5.8±0.5 m.s-1; P<0.001). Between-group difference in pulse wave velocity remained significant even after the adjustment for age, heart rate, fasting plasma glucose and each of brachial (P<0.001) and 24h blood pressure parameters (P<0.01). The difference in augmentation index between groups did not reach the statistical significance (19±14 vs. 16±13 %; NS). In multiple regression analysis, age (P<0.001), mean blood pressure (P=0.002), high sensitive C-reactive protein (P=0.007) and 24h urine norepinephrine (P=0.007) were independently associated with pulse wave velocity in pheochromocytoma. Successful tumor removal led to a significant decrease in pulse wave velocity (7.0±1.2 vs.6.0±1.1 m.s-1; P<0.001). In conclusion, patients with pheochromocytoma have an increase in pulse wave velocity, which is reversed by the successful tumor removal. Age, mean blood pressure, hs-CRP and norepinephrine levels are independent predictors of pulse wave velocity.

Keywords: arterial stiffness, pulse wave velocity, catecholamines, pheochromocytoma

Introduction

Accumulating evidence suggests that catecholamines can influence vascular smooth muscle cell growth and remodeling of vascular structure, independently of haemodynamics 1-3. The accelerated deposition of extracellular matrix proteins within the blood vessel wall contributes to a progressive loss of vascular compliance, abnormalities of pulse wave morphology, augmentation of pulse pressure and increased cardiovascular stress, culminating in premature cardiovascular morbidity and mortality 4-7.

Carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity (PWV) is an index of arterial stiffness and has been shown to be an independent predictor of cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients 5,6,8,9 and a marker of cardiovascular risk in the general population 7,10,11. Arterial stiffness has been affected mainly by age and blood pressure12, but also by diabetes mellitus13, chronic renal failure 14 and chronic subclinical inflammation15.

Only few data are available in humans about the effect of chronic catecholamine overproduction on the vasculature. Pheochromocytoma/paraganglioma are catecholamine producing tumors arising either from adrenal medulla or sympathetic nervous system associated chromaffin cells. Catecholamines produced by the tumor are responsible for the large variety of symptoms and signs due to their effect on haemodynamics and metabolism 16-19. Previous study performed on subcutaneous small resistance arteries in normotensive patients and subjects with essential hypertension and pheochromocytoma demonstrated that a pronounced activation of adrenergic system is not associated with subcutaneous vascular smooth muscle cell hypertrophy or hyperplasia 1.

Our study was aimed at evaluating the effect of pheochromocytoma on central arterial (aortic) stiffness measured by PWV and augmentation index (AI) in patients with pheochromocytoma/ paraganglioma before and after tumor removal. We also focused our study to investigate factors influencing stiffness of large arteries such as glucose levels, blood pressure variability and high sensitive C-reactive protein (hs-CRP) in patients with pheochromocytoma.

Research Design and Methods

Subjects

We have studied 45 patients with pheochromocytoma (PHEO) (22 males) in the period from October 2003 to May 2009. The diagnosis of PHEO was based on elevated 24-hour urine catecholamines /equally elevated norepinephrine and epinephrine (n=18), predominantly elevated norepinephrine (n=19), and predominantly elevated epinephrine (n=8)/ and the demonstration of tumor by computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. All patients underwent surgical removal of the tumor and the diagnosis was confirmed histopathologically. Seventeen patients had diabetes mellitus which was defined by either the medication with insulin / oral antidiabetic drugs or by repeated fasting plasma glucose > 7.1 mmol/l 20.

Patients discontinued antihypertensive medication (except nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers and alpha1-adrenoceptor blockers) at least two weeks before the examination. In fact, 38 patients were treated (31 by Doxazosin, 5 by Verapamil and 2 by combination of Doxazosin and Verapamil) for two weeks before the investigation.

All patients were re-examined at least one year after the tumor removal and 16 subjects with persistent /essential/ hypertension and two subjects with malignant form were excluded from our study. Only 27 patients (11 with equally elevated epinephrine and norepinephrine, 6 with predominantly elevated epinephrine, and 10 with predominantly elevated norepinephrine) were found free of disease recurrence including persistent arterial hypertension and were without concomitant antihypertensive medication.

Control group included 45 normotensive healthy volunteers (C) (25 males). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and the study was prepared in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the local Ethics Committee.

Pulse wave analysis

All subjects were studied after an overnight fasting in a quiet room. Subjects were always reexamined by the same investigator. After 15 min of rest in the supine position, the PWV and AI were measured using the applanation tonometer SphygmoCor (AtCor Medical, West Ryde, Australia). The pulse wave was acquired at the radial artery. Aortic pulse wave was derived by means of generalized transfer function and calibrated using a single simultaneous measurement of brachial artery blood pressure using an oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Dinamap, Tampa, FL). The aortic (or central) AI was calculated as the ratio of the pressure difference (Δ P) between the shoulder of the wave and the peak systolic pressure according to the formula of AI = ΔP/(systolic BP - diastolic BP) 21. The AI values were corrected for differences in heart rate from 75 beats/min using a SphygmoCor built-in algorithm.21 A high level of repeatability and reproducibility of SphygmoCor pulse wave measurements has been established for various patient groups 22.

Aortic PWV was assessed by the time difference between pulse wave upstrokes, which were consecutively recorded at the right carotid artery and right femoral artery and aligned by electrocardiogram-based trigger. The “percentage pulse height algorithm” was used to locate the “foot” of the pulse waves.

Biochemistry and catecholamine analysis

Blood samples for routine biochemical screening by an automatic analyzer (Modular; Roche Diagnostic; Basel; Switzerland) were taken in the morning after overnight fasting. Urine catecholamines were analyzed by high performance liquid chromatography with fluorometric detector (HPLC/FLD 1100S, Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, USA). The system was calibrated with a catecholamine standard using the ClinRep test kit (Recipe Chemicals and Instruments GmbH, Munich, Germany).

High-sensitive C-reactive protein was measured only in patients with pheochromocytoma and was analyzed by means of an automatic nephelometer BN II (Dade Behring, Leiderbach, Germany). Normal values 0.0–2.9 mg/l, low detection limit 0.175 mg/l, intraassay coefficient of variation (CV) 2.3–4.4%, interassay CV 2.5–5.7%.

Blood pressure measurement

Office artery blood pressure was measured according to ESH Guidelines by oscillometric sphygmomanometer (Dinamap, Critikon, Tampa, FL). 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring was performed using an oscillometric device Spacelabs 90207 (SpaceLabs Medical, Richmond, Washington, USA), which was set to measure blood pressure every 20 min during the day (from 6:00 to 22:00 h) and every 30 min during the night (from 22:00 to 6:00h). Daytime BP variability was assessed using the standard deviations during the daytime period of BP in PHEO.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed by Statistica for Windows ver.8.0 statistical software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, USA). Data were described as means ± SD or medians (interquartile range) for non-normally distributed variables (Shapiro-Wilks W test). Comparison between the groups was made using Student’s t-test or the Mann-Whitney test (for data with non-normal distribution). Analysis of paired values (data before and after operation) was performed by means of paired t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test (for data with non-normal distribution). Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to characterize the relationship between individual variables. Non-normally distributed variables (fasting plasma glucose, catecholamine levels, high sensitive CRP) were log-transformed (log10) before this analysis. Analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was used to adjust for the differences in clinical and biochemical characteristics. The multivariate stepwise regression model was used to identify independent determinants of PWV. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Results

Baseline subject characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Gender ratio, body mass index, age, lipid profile, and renal function did not differ significantly between the groups. Patients with PHEO had significantly higher urine catecholamines in comparison with C (epinephrine and norepinephrine: P<0.001) and as expected significantly higher fasting plasma glucose (P<0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of patients with pheochromocytoma and healthy controls.

| PHEO | C | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female/male) | 45 (23/22) | 45 (20/25) | NS |

| Age (yr) | 47 ± 12 | 44 ± 10 | 0.167 |

| BMI (kg.m-2) | 25 ± 5 | 25 ± 4 | 0.929 |

| Hypertension (n(%)) | 31 (69%) | - | - |

| Duration of hypertension (yr) | 4 ± 6 | - | - |

| Treated (n(%)) | 38 (84%) | - | - |

| Smoking status (n(%)) | 15 (33%) | 11 (24%) | 0.393 |

| Diabetes mellitus (n(%)) | 17 (38%) | - | - |

| Duration of diabetes (yr) | 1 ± 2 | - | - |

| Serum creatinine (μmol/L) | 74 ± 16 | 77 ± 14 | 0.393 |

| Fasting plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 6.1 ± 1.6 | 4.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.3 ± 1.4 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 0.682 |

| HDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 1.5 ± 0.4 | 0.903 |

| LDL cholesterol (mmol/L) | 3.2 ± 1.1 | 3.2 ± 0.8 | 0.902 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.5 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 0.487 |

| hs- CRP (mg/L) | 0.89 (0.32;1.4) | NA | - |

| 24h urine epinephrine* | 143 (28;1374) | 25 (13;35) | < 0.001 |

| 24h urine norepinephrine* | 1284 (493;3724) | 120 (94;162) | < 0.001 |

Values are shown as means ± SD (normal distribution) or medians (interquartile range).

nmol/gram of Creatinine

The differences in hemodynamic parameters and pulse wave indices are summarized in Table 2. Patients with PHEO had significantly higher all BP modalities except the mean 24h and day diastolic BP. Systolic day time blood pressure variability was significantly higher in comparison to C (P<0.05). Significant difference between both groups was also in office and 24h heart rate (P<0.05).

Table 2.

Central a peripheral hemodynamic parameters in pheochromocytoma and healthy controls.

| PHEO | C | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart Rate (bpm) | 71 ± 14 | 66 ± 10 | 0.037 |

| Brachial BP (mmHg) | 132 ± 22 / 76 ± 12 | 117 ± 11 / 70 ± 8 | < 0.001/0.016 |

| Brachial mean BP (mmHg) | 95 ± 15 | 86 ± 8 | < 0.001 |

| Central BP (mmHg) | 117 ± 18 / 77 ± 13 | 104 ± 10 / 71 ± 8 | < 0.001/0.013 |

| Brachial mean BP (mmHg) | 56 ± 15 | 33 ± 7 | < 0.001 |

| Mean 24h BP (mmHg) | 127 ± 17 / 77 ± 11 | 116 ± 9 / 73 ± 7 | 0.005/0.07 |

| Day 24h BP (mmHg) | 129 ± 16 / 80 ± 11 | 120 ± 9 / 77 ± 7 | 0.009/0.16 |

| Night 24 BP (mmHg) | 122 ± 21 / 72 ± 13 | 106 ± 11 / 66 ± 7 | <0.001/0.02 |

| Mean 24h HR (bpm) | 75 ± 12 | 70 ± 8 | 0.025 |

| Daytime BP variability (mmHg) | 12 ± 5 / 9 ± 3 | 10 ± 3 / 9 ± 2 | 0.022/0.694 |

| Augmentation Index 75* | 19 ± 14 | 16 ± 13 | 0.316 |

| PWV (m/s) | 7.2 ± 1.4 | 5.8 ± 0.5 | < 0.001 |

| PWVadj ** (m/s) | 6.9 ± 0.1 | 6.1 ± 0.1 | < 0.001 |

Values are shown as means ± SD.

Augmentation index for heart rate 75 beats/min

adjusted for age, heart rate, brachial mean blood pressure and fasting plasma glucose

The PWV in patients with PHEO was significantly higher than in C (P<0.001). The differences in PWV remained significant even after the adjustment for age, heart rate, mean BP and fasting plasma glucose (Table 2). The same model was used for each of the other brachial and 24h blood pressure parameters and the differences in PWV still remained significant (P<0.001 for brachial SBP, DBP, PP; P=0.002 for 24h SBP and 24h DBP). Between-group difference in AI did not reach the statistical significance (P=0.32) (Table 2).

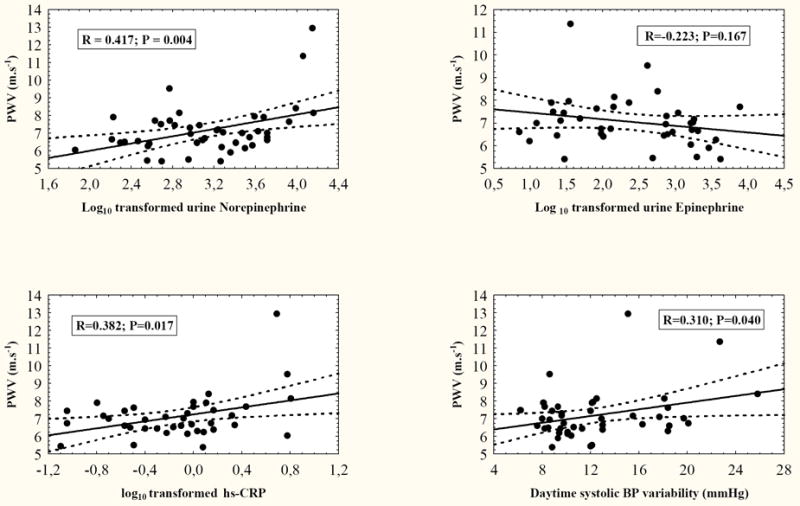

In the PHEO group, PWV values were positively related to age, BMI, all blood pressure modalities, AI, heart rate, fasting plasma glucose, hs-CRP, daytime systolic BP variability and urine norepinephrine levels (Table 3, Fig.1). Stepwise multiple regression analysis demonstrated that age (β =0.428; P<0.001), mean blood pressure (β=0.426; P=0.002), hs-CRP (β=0.326; P=0.007) and urine norepinephrine (β=0.443; P=0.007) were the only variables independently associated with PWV (R2=0.63; P<0.0001) in patients with PHEO.

Table 3.

Univariate correlation analysis between PWV, log10 24h urine norepinephrine and clinical/biochemical variables in subjects with pheochromocytoma.

| PWV | Log 10 Norepinephrine | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R | P | R | P | |

| Age | 0.30 | 0.048 | -0.21 | 0.177 |

| BMI | 0.33 | 0.028 | -0.12 | 0.427 |

| Heart Rate | 0.48 | < 0.001 | 0.23 | 0.127 |

| Brachial SBP | 0.60 | < 0.001 | 0.46 | 0.002 |

| Brachial DBP | 0.52 | < 0.001 | 0.40 | 0.006 |

| Mean BP | 0.59 | < 0.001 | 0.47 | 0.001 |

| Central SBP | 0.57 | < 0.001 | 0.44 | 0.003 |

| Central DBP | 0.53 | < 0.001 | 0.41 | 0.005 |

| AI 75 | 0.29 | 0.059 | 0.06 | 0.698 |

| Mean 24h SBP | 0.43 | 0.003 | 0.51 | < 0.001 |

| Mean 24h DBP | 0.32 | 0.030 | 0.41 | 0.005 |

| Daytime SBP variability | 0.31 | 0.040 | 0.55 | < 0.001 |

| Daytime DBP variability | 0.10 | 0.528 | 0.41 | 0.006 |

| Log10 fasting plasma glucose | 0.32 | 0.031 | 0.29 | 0.050 |

| Log10 hs-CRP | 0.38 | 0.017 | -0.06 | 0.712 |

| Total cholesterol | 0.11 | 0.469 | 0.25 | 0.096 |

| Triglycerides | 0.07 | 0.669 | 0.09 | 0.522 |

| Log10 24h urine Epinephrine | -0.22 | 0.167 | -0.19 | 0.140 |

| Log10 24h urine Norepinephrine | 0.42 | 0.004 | - | - |

PWV = pulse wave velocity, AI = augmentation index, r = the Pearson’s correlation coefficient, P = level of significance, BMI = body mass index, SBP = systolic blood pressure, DBP = diastolic blood pressure, MBP = mean blood pressure

Figure 1.

Univariate correlation analysis between PWV and urine norepinephrine (upper left), urine epinephrine (upper right), hs-CRP (lower left) and daytime BP variability (lower right)

Urine norepinephrine was also positively associated with brachial and central BP, mean 24h BP, daytime systolic BP variability and PWV (Table 3, Fig.1). No similar correlation between urine catecholamine levels and PWV were found in the control group (Log10 Epinephrine R= -0.07, P= 0.75; Log10 Norepinephrine R=0.20, P=0.37).

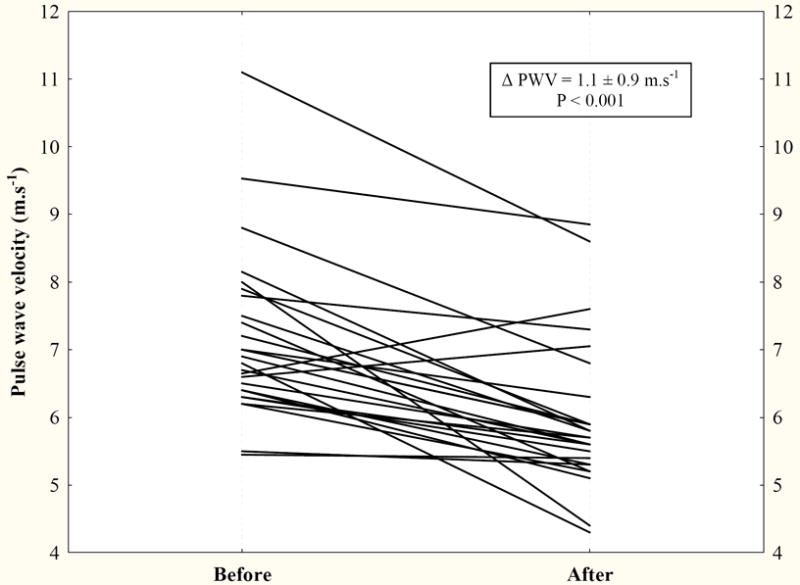

As indicated in Table 4 surgical treatment in patients with PHEO led to normalization of catecholamine levels, blood pressure parameters, hs-CRP and plasma glucose. Change in PWV (mean difference 1.1 ± 0.9 m.s-1; P<0.001) after tumor removal is illustrated in the Fig.2.

Table 4.

The effect of tumor removal in the subset of patients with pheochromocytoma compared to control subjects.

| Pheochromocytoma | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| before surgery | after surgery | P (paired data) | Controls | |

| Sex (female/male) | 27 (13/14) | 27 (13/14) | - | 45 (20/25) |

| Age (years) | 45 ± 12 | 46 ± 12 | < 0.001 | 44 ± 10 |

| Body mass index (kg.m-2) | 25 ± 4 | 26 ± 4 | < 0.001 | 25 ± 4 |

| Total cholesterol (mmol/L) | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 0.003 | 5.2 ± 1.0 |

| Triglycerides (mmol/L) | 1.6 ± 1.2 | 1.3 ± 0.4 | 0.117 | 1.4 ± 0.9 |

| Fast.plasma glucose (mmol/L) | 6.0 ± 1.7 aaa | 4.7 ± 0.6 | < 0.001 | 4.8 ± 0.5 |

| hs-CRP (mg/L) | 0.50 (0.27;1.00) | 0.19 (0.12;0.57) | 0.040 | NA |

| 24h urine Epinephrine * | 593 (34;1766) aaa | 14 (9;21) | < 0.001 | 25 (13;35) |

| 24h urine Norepinephrine * | 1426 (588;3501) aaa | 139 (113;199) | < 0.001 | 118 (94;162) |

| Heart rate (bpm) | 71 ± 15a | 65 ± 9 | 0.017 | 66 ± 10 |

| Brachial BP (mmHg) | 134 ± 18 / 77 ± 11 aaa/aa | 117 ± 13 / 71 ± 8 | < 0.001 /0.003 | 117 ± 11 / 70 ± 8 |

| Central BP (mmHg) | 119 ± 17 / 78 ± 12 aaa/aa | 106 ± 12 / 72 ± 9 | < 0.001 / 0.003 | 104 ± 10 / 71 ± 8 |

| Mean 24h BP (mmHg) | 127 ± 16 / 78 ± 12 a / - | 115 ± 7 / 73 ± 6 | < 0.001 / 0.04 | 116 ± 9 / 73 ± 7 |

| Daytime BP variation (mmHg) | 12 ± 4 / 10 ± 2 a / - | 10 ± 3 / 9 ± 2 | 0.036 / 0.07 | 10 ± 3 / 9 ± 2 |

| AI 75** (%) | 19 ± 13 | 18 ± 13 | 0.560 | 14 ± 13 |

| Pulse wave velocity (m.s-1) | 7.0 ± 1.2 aaa | 6.0 ± 1.1 | < 0.001 | 5.8 ± 0.5 |

| PWVadj *** (m.s-1) | 6.7 ± 0.2 aa | 6.0 ± 0.1 | < 0.01 | 6.0 ± 0.1 |

Values are means ± SD or medians (interquartile range).

P<0.05,

P<0.01,

P<0.001 baseline PHEO vs. C

nmol/g creatinine

Augmentation index for heart rate 75 beats/min

adjusted for age, heart rate, brachial mean blood pressure and fasting plasma glucose

Figure 2.

The change in PWV after tumor removal in patients with pheochromocytoma.

Discussion

This study demonstrated that patients with PHEO have increased aortic stiffness as evidenced by an increased PWV in comparison to healthy controls. Age, mean blood pressure, hs-CRP and urine norepinephrine were independent predictors of PWV in patients with PHEO. The study also showed that all abnormalities, including aortic stiffness are entirely reversed after successful tumor removal.

Blood pressure and age are main determinants of arterial stiffness12. PHEO group presented with significantly higher blood pressure in comparison to control group which might be an explanation for higher PWV in PHEO patients. The difference in PWV, however, remained significant even after the adjustment for blood pressure data.

There are other multiple direct and indirect mechanisms that may explain the increase of aortic stiffness in patients with pheochromocytoma.

Previous in vitro studies have found that norepinephrine leads to hypertrophy and proliferation of cultured smooth muscle cells 3 and also induces proliferation of adventitial fibroblasts 23. Norepinephrine-induced hypertrophy of vascular smooth muscle cells is mediated by α-adrenoceptors 23. Alpha1-adrenoceptors of the smooth muscle cells stimulate production of collagen and fibronectin expression 3. In vivo studies using surgical or sympathetic denervation 24, systemic infusion of catecholamines 25 or α-adrenoceptor antagonists 26 suggested that norepinephrine may have a direct trophic effect on the normal and injured vascular wall 27. Furthermore, positive correlation of plasma catecholamines with wall hypertrophy 28 and the severity of atherosclerosis 29 were found in humans.

We found that urine norepinephrine (but not epinephrine) excretion was positively related to PWV and BP levels. This suggests that norepinephrine may be an important determinant contributing to increased arterial stiffness in patients with PHEO. Central sympathetic outflow probably does not contribute to the alteration of arterial stiffness in pheochromocytoma, since in previous study surgical removal of the tumor resulted in an increase of central sympathetic drive 30.

Other mechanism, which may also play a role in elevation of arterial stiffness, is higher fasting plasma glucose in patients with PHEO 31. Indeed, we observed positive correlation between PWV and fasting plasma glucose in our study. There is evidence that hyperglycemia in patients with diabetes mellitus may contribute to the proliferation of arterial smooth muscle cells and arterial stiffness 13,32, in particular by the accumulation of advanced glycation end products and protein cross-links in the arterial wall 33. Nevertheless, PWV in PHEO remained higher compared to C even after the adjustment for glucose level.

Higher BP variability may also be involved in the observed increase in arterial stiffness in patients with PHEO. In our previous study, we found that excess of catecholamines in patients with PHEO is associated with higher daytime BP variability when compared to essential hypertensives, regardless of antihypertensive therapy 34. The relationship between 24-h systolic BP variability and PWV was found in hypertensive patients 35. We have observed mild significant relationship between PWV and daytime systolic BP variability. Thus, daytime BP variability may be also involved in arterial stiffening in PHEO.

Finally, chronic inflammatory process may also contribute to arterial stiffness15. Elevated markers of inflammation have been shown to correlate positively with arterial stiffness in essential hypertension and chronic inflammatory diseases 36,37. In our recent study, we have shown that chronic catecholamine excess in patients with PHEO is accompanied by an increase in inflammatory markers, which was reversed by the tumor removal 38. In present study we have found significant association between hs-CRP and PWV.

Our study is limitated by relatively small sample size of patients due to rare occurrence of PHEO. To clarify the differences between patients with predominantly norepinephrine- and epinephrine-secreting PHEO, larger studies are needed. Another confounding factor could be the treatment with alpha1-adrenoceptor blockers and/or verapamil in some patients because of high suspicion to PHEO based on previous results in these patients. This short-term pretreatment with alpha1-adrenoceptor blockers and/or verapamil was initiated in order to decrease the risk of potential cardiovascular complications. On the other hand catecholamines, as well as other hormonal levels, are minimally affected by this therapy39. It is likely, that withdrawal of all antihypertensive therapy would enhance observed significant differences in PWV. Vasodilator effect of these drugs may explain why no significant between-group differences in the AI were found. The AI is a composite measure that depends on PWV, the site of reflection and the amplitude of reflected wave. The normal AI in the setting of elevated PWV may, therefore, indicate reduced wave reflection, possibly because of reduced impedance mismatch at the reflection site due to peripheral vasodilatation. Vasoactive drugs have direct and more impact on AI than on PWV, since the aorta contains much less smooth muscle cells. Therefore vasoactive drugs may change the AI independently from PWV40. Furthermore, AI assessment is more operator-dependent and less robust than PWV measurement. Although linear relationship between PWV and AI was repeatedly found 41, some investigators reported a weaker correlation and considered PWV to be a more precise marker of central vessels stiffness 42. Nevertheless the tendency to higher AI levels in PHEO patients compared to controls was evident.

In conclusion, our study demonstrates that patients with pheochromocytoma have higher carotid-femoral pulse wave velocity as index of aortic stiffness, which is completely reversed by the successful tumor removal. Age, mean blood pressure, but also hs-CRP and norepinephrine levels are independent predictors of pulse wave velocity in patients with pheochromocytoma. Higher aortic stiffness may contribute to an increased cardiovascular risk in PHEO patients.

Acknowledgments

We highly appreciate statistical help of dr.Wichterle and technical assistance of mrs. Landová. This study was supported by the Research Projects MSM-0021620807, MSM-0021620817 and MSM-0021620808 of Ministry of Education, Czech Republic and Research Project MZOVFN2005 from the Ministry of Health, Czech Republic.

References

- 1.Porteri E, Rizzoni D, Mulvany MJ, De Ciuceis C, Sleiman I, Boari GE, Castellano M, Muiesan ML, Zani F, Rosei EA. Adrenergic mechanisms and remodeling of subcutaneous small resistance arteries in humans. Journal of Hypertension. 2003;21:2345–2352. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200312000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mancia G, Grassi G, Giannattasio C, Seravalle G. Sympathetic activation in the pathogenesis of hypertension and progression of organ damage. Hypertension. 1999;34:724–728. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.4.724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O’Callaghan CJ, Williams B. The regulation of human vascular smooth muscle extracellular matrix protein production by alpha- and beta-adrenoceptor stimulation. Journal of Hypertension. 2002;20:287–294. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200202000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ward MR, Pasterkamp G, Yeung AC, Borst C. Arterial remodeling. Mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation. 2000;102:1186–1191. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.10.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boutouyrie P, Tropeano AI, Asmar R, Gautier I, Benetos A, Lacolley P, Laurent S. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of primary coronary events in hypertensive patients: a longitudinal study. Hypertension. 2002;39:10–15. doi: 10.1161/hy0102.099031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blacher J, Asmar R, Djane S, London GM, Safar ME. Aortic pulse wave velocity as a marker of cardiovascular risk in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 1999;33:1111–1117. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.33.5.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amar J, Ruidavets JB, Chamontin B, Drouet L, Ferrieres J. Arterial stiffness and cardiovascular risk factors in a population-based study. Journal of Hypertension. 2001;19:381–387. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200103000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Laurent S, Boutouyrie P, Asmar R, Gautier I, Laloux B, Guize L, Ducimetiere P, Benetos A. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of all-cause and cardiovascular mortality in hypertensive patients. Hypertension. 2001;37:1236–1241. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.5.1236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laurent S, Katsahian S, Fassot C, Tropeano AI, Gautier I, Laloux B, Boutouyrie P. Aortic stiffness is an independent predictor of fatal stroke in essential hypertension. Stroke. 2003;34:1203–1206. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000065428.03209.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Willum-Hansen T, Staessen JA, Torp-Pedersen C, Rasmussen S, Thijs L, Ibsen H, Jeppesen J. Prognostic value of aortic pulse wave velocity as index of arterial stiffness in the general population. Circulation. 2006;113:664–670. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.579342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shokawa T, Imazu M, Yamamoto H, Toyofuku M, Tasaki N, Okimoto T, Yamane K, Kohno N. Pulse wave velocity predicts cardiovascular mortality: findings from the Hawaii-Los Angeles-Hiroshima study. Circ J. 2005;69:259–264. doi: 10.1253/circj.69.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Rourke M. Mechanical principles in arterial disease. Hypertension. 1995;26:2–9. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.26.1.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schram MT, Henry RM, van Dijk RA, Kostense PJ, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Bouter LM, Westerhof N, Stehouwer CD. Increased central artery stiffness in impaired glucose metabolism and type 2 diabetes: the Hoorn Study. Hypertension. 2004;43:176–181. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000111829.46090.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blacher J, Safar ME, Pannier B, Guerin AP, Marchais SJ, London GM. Prognostic significance of arterial stiffness measurements in end-stage renal disease patients. Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 2002;11:629–634. doi: 10.1097/00041552-200211000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Plantinga Y, Taddei S, Salvetti A. C-reactive protein and hypertension: is there a causal relationship? Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:1693–1698. doi: 10.2174/138161207780831365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lenders JW, Eisenhofer G, Mannelli M, Pacak K. Phaeochromocytoma. Lancet. 2005;366:665–675. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67139-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zelinka T, Eisenhofer G, Pacak K. Pheochromocytoma as a catecholamine producing tumor: Implications for clinical practice. Stress. 2007;10:195–203. doi: 10.1080/10253890701395896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widimský J., Jr Recent advances in the diagnosis and treatment of pheochromocytoma. Kidney Blood Press Res. 2006;29:321–326. doi: 10.1159/000097262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holaj R, Zelinka T, Wichterle D, Petrak O, Strauch B, Vrankova A, Majtan B, Spacil J, Malik J, Widimsky J., Jr Increased carotid intima-media thickness in patients with pheochromocytoma in comparison to essential hypertension. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2009;23:350–8. doi: 10.1038/jhh.2008.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Global Guideline for Type 2 Diabetes: recommendations for standard, comprehensive, and minimal care. Diabet Med. 2006;23:579–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2006.01918.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Rourke MF, Pauca A, Jiang XJ. Pulse wave analysis. British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 2001;51:507–522. doi: 10.1046/j.0306-5251.2001.01400.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filipovský J, Svobodová V, Pecen L. Reproducibility of radial pulse wave analysis in healthy subjects. Journal of Hypertension. 2000;18:1033–1040. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200018080-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Faber JE, Yang N, Xin X. Expression of alpha-adrenoceptor subtypes by smooth muscle cells and adventitial fibroblasts in rat aorta and in cell culture. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 2001;298:441–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Head RJ. Hypernoradrenergic innervation and vascular smooth muscle hyperplastic change. Blood Vessels. 1991;28:173–178. doi: 10.1159/000158858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson MD, Grignolo A, Kuhn CM, Schanberg SM. Hypertension and cardiovascular hypertrophy during chronic catecholamine infusion in rats. Life Sciences. 1983;33:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90410-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jonsson JR, Head RJ, Frewin DB. Effect of alpha 1-adrenoceptor blockade on the development of hypertension in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1992;211:263–268. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(92)90538-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang H, Faber JE. Trophic effect of norepinephrine on arterial intima-media and adventitia is augmented by injury and mediated by different alpha1-adrenoceptor subtypes. Circulation Research. 2001;89:815–822. doi: 10.1161/hh2101.098379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dinenno FA, Jones PP, Seals DR, Tanaka H. Age-associated arterial wall thickening is related to elevations in sympathetic activity in healthy humans. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;278:H1205–1210. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.278.4.H1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grassi G. Role of the sympathetic nervous system in human hypertension. Journal of Hypertension. 1998;16:1979–1987. doi: 10.1097/00004872-199816121-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Grassi G, Seravalle G, Turri C, Mancia G. Sympathetic nerve traffic responses to surgical removal of pheochromocytoma. Hypertension. 1999;34:461–465. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.34.3.461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Turnbull DM, Johnston DG, Alberti KG, Hall R. Hormonal and metabolic studies in a patient with a pheochromocytoma. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1980;51:930–933. doi: 10.1210/jcem-51-4-930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Henry RM, Kostense PJ, Spijkerman AM, Dekker JM, Nijpels G, Heine RJ, Kamp O, Westerhof N, Bouter LM, Stehouwer CD. Arterial stiffness increases with deteriorating glucose tolerance status: the Hoorn Study. Circulation. 2003;107:2089–2095. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000065222.34933.FC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh R, Barden A, Mori T, Beilin L. Advanced glycation end-products: a review. Diabetologia. 2001;44:129–146. doi: 10.1007/s001250051591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zelinka T, Strauch B, Petrak O, Holaj R, Vrankova A, Weisserova H, Pacak K, Widimsky J., Jr Increased blood pressure variability in pheochromocytoma compared to essential hypertension patients. Journal of Hypertension. 2005;23:2033–2039. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000185714.60788.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ichihara A, Kaneshiro Y, Takemitsu T, Sakoda M, Hayashi M. Ambulatory blood pressure variability and brachial-ankle pulse wave velocity in untreated hypertensive patients. Journal of Human Hypertension. 2006;20:529–536. doi: 10.1038/sj.jhh.1002023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mahmud A, Feely J. Arterial stiffness is related to systemic inflammation in essential hypertension. Hypertension. 2005;46:1118–1122. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000185463.27209.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Roman MJ, Devereux RB, Schwartz JE, Lockshin MD, Paget SA, Davis A, Crow MK, Sammaritano L, Levine DM, Shankar BA, Moeller E, Salmon JE. Arterial stiffness in chronic inflammatory diseases. Hypertension. 2005;46:194–199. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000168055.89955.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zelinka T, Petrák O, Štrauch B, Holaj R, Kvasnička J, Mazoch J, Pacák K, Widimský J., Jr Elevated Inflammation Markers in Pheochromocytoma Compared to Other Forms of Hypertension. Neuroimmunomodulation. 2007;14:57–64. doi: 10.1159/000107289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacak K, Lenders JWM, Eisenhofer G. Pheochromocytoma : diagnosis, localization, and treatment. Blackwell; Oxford: 2007. p. 172. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kelly RP, Millasseau SC, Ritter JM, Chowienczyk PJ. Vasoactive drugs influence aortic augmentation index independently of pulse-wave velocity in healthy men. Hypertension. 2001;37:1429–1433. doi: 10.1161/01.hyp.37.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yasmin, Brown MJ. Similarities and differences between augmentation index and pulse wave velocity in the assessment of arterial stiffness. Qjm. 1999;92:595–600. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/92.10.595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schiffrin EL. Vascular stiffening and arterial compliance. Implications for systolic blood pressure. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:39S–48S. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]