Abstract

To transcribe the treat-to-target (T2T) recommendations into a version that can be easily understood by patients. A core group of physicians and patients involved in the elaboration of the T2T recommendations produced a draft version of the T2T recommendations in lay language. This version was discussed, changed and reworded during a 1-day meeting with nine patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) from nine different European countries. Finally, the level of agreement with the translation and with the content of the recommendations was assessed by the patient participants. The project resulted in a patient version of the T2T recommendations. The level of agreement with the translation and the content was high. The group discussion revealed a number of potential barriers for the implementation of the recommendations in clinical practice, such as inequalities in arthritis healthcare provision across Europe. An accurate version of the T2T recommendations that can be easily understood by patients is available and can improve the shared decision process in the management of RA.

Introduction

In 2008, an international Steering Group of rheumatologists and patients took the initiative to develop a set of recommendations for the tight control of rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients (“treat-to-target,” T2T).1 Clinical trial results over the last decade have demonstrated that strategies for tight control lead to better outcomes. These recommendations were developed in line with the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) standardised operational procedures,2 including a comprehensive systematic literature review,3 followed by a thorough data driven consensus process. The recommendations were extensively discussed during a 2-day meeting gathering more than 60 experts from different continents, including six patient representatives. They agreed on a set of four overarching principles and 10 recommendations. Important components of these recommendations are target setting for drug treatment, regular monitoring of disease activity—using composite measures, including joint counts—and adjustment of treatment if the desired target is not achieved.

In October 2009, the implications of the recommendations for clinical practice were discussed during a global T2T meeting. More than 25 physicians from 22 countries and two patient delegates expressed the need for developing a patient version of the recommendations as a logical consequence of the first overarching principle that emphasises the importance of a shared decision-making process between the physician and the patient. The last recommendation states that this can only be achieved if the patient is well informed about the different treatment options. As a follow-up on these statements, the Steering Group appointed a small working group with the objective to develop a patient version of the T2T recommendations as an important tool for patient education.

A patient version is important for several reasons. RA patients need to be appropriately informed about the potential benefits and harms of new pharmacological treatments.4–6 The technical nature of the medical language of recommendations is a barrier for patients to understand their potential value.7 8 Because drugs give the best outcomes when used according to a predefined regime, a proper understanding, acceptance and adherence are of utmost importance,9 especially since some patients believe that the potential benefits do not outweigh the potential harms or personal preferences.10–12 Patient information that is understandable and written in lay language may enable them to make informed decisions about their treatment. It heightens patients' satisfaction5 and increases adherence to their treatment.13

If patients are aware of the recommendations for the treatment of RA, and they know precisely how the treatment and monitoring should be organised according to these recommendations, they are able to start the dialogue with their rheumatologist.

Furthermore, a patient version might support physicians to engage the patient in the decision-making process on an equal level. Finally, physicians who are still reluctant to follow the T2T principles for their RA patients might be helped with a patient version to start this dialogue about the risks and benefits of tight control. The objective of the present study was to develop a patient version of the T2T recommendations.

Methods

The core group, consisting of four members of the international T2T Steering Group, including one patient representative (MPTdW), produced a draft version of the T2T recommendations in lay language.

This version was discussed, amended and reworded during a 1-day consensus meeting with nine RA patients and moderated by two members of the core group (DMFMvdH, MPTdW). Recruitment and selection of participants was carried out with the help of the EULAR Standing Committee of Patients with Arthritis/Rheumatism in Europe and took place through purposive sampling accounting for geographical variation, gender and age. Participants should speak and read English. The core group made the final selection. The group consisted of eight women and one man, from nine countries representing all regions of Europe: Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ireland, Norway, Portugal, The Netherlands, Romania and the UK. Age varied between 31 and 66 years. Five participants were already involved in the T2T consensus meeting.

At the start of the meeting, the original recommendations were introduced and explained. Then, the draft patient version, developed by the core group, was shared with the participants. It was emphasised that the group was not allowed to make any changes in the content or meaning of the recommendations when developing the patient version.

Formulating a patient version in lay language was carried out by constantly comparing the original statements and the draft patient version. The consensus meeting was recorded. At the end of the meeting, the level of agreement with the translations as well as with the content was assessed by all patient participants, including the patient moderator, anonymously on a numerical rating scale ranging from 0 (no agreement) to 10 (full agreement). The group finally gave suggestions for implementation.

Results

Statements

The patient version of the recommendations is presented in table 1. The group tried to stay as close as possible to the original meaning. Sometimes, simplification was achieved by cutting long sentences in multiple short sentences. At other moments, the group looked for common synonyms or clarification in lay language. Long discussions took place concerning the translation and the value of the words “significant” and “validated.” Finally, the group decided on different solutions, and this kept the word significant and proposed that each country should explore synonyms or translations in their own language. For the word validated, many synonyms were brought forward, but in no cases did this capture the meaning of the word. At the end, the term was not seen as a crucial element to understand the message of the recommendation. The decision was made to delete the word.

Table 1.

Original and patient version of the treat-to-target (T2T) recommendations for treating rheumatoid arthritis (RA) to target

| Original | Patient version |

|---|---|

| Overarching T2T principles | |

| (A)The treatment of RA must be based on a shared decision between patient and rheumatologist | (A)Decisions regarding the treatment of RA must be made by the patient and rheumatologist together. |

| (B)The primary goal of treating the patient with RA is to maximise long-term health-related quality of life through control of symptoms, prevention of structural damage, normalisation of function and social participation | (B)The most important goal of treatment is to maximise long-term health-related quality of life. This can be achieved through |

| control of disease symptoms like pain, inflammation, stiffness and fatigue; | |

| prevention of damage to joints and bones; | |

| regaining normal function and participation in daily-life activities. | |

| (C)Abrogation of inflammation is the most important way to achieve these goals | (C)The most important way to achieve these goals is to stop joint inflammation |

| (D)Treatment to target by measuring disease activity and adjusting therapy accordingly optimises outcomes in RA | (D)Treatment toward a clear target of disease activity gives the best results in RA. This can be achieved by measuring disease activity and adjusting therapy if the target is not achieved. |

| Recommendations | |

| (1)The primary target for treatment of RA should be a state of clinical remission | (1)The primary target of treatment of RA should be clinical remission |

| (2)Clinical remission is defined as the absence of signs and symptoms of significant inflammatory disease activity | (2)Clinical remission means that significant signs and symptoms of the disease that are caused by inflammation are absent |

| (3)While remission should be a clear target, based on available evidence low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative therapeutic goal, particularly in established, longstanding disease | (3)Although remission should be the target, it is not possible for some patients, in particular for those with long disease duration. Therefore, low disease activity may be an acceptable alternative. |

| (4)Until the desired treatment target is reached, drug therapy should be adjusted at least every 3 months | (4)Until the desired treatment target is reached, drug therapy should be adjusted at least every 3 months |

| (5)Measures of disease activity must be obtained and documented regularly, as frequently as monthly for patients with high/moderate disease activity or less frequently (such as every 3–6 months) for patients in sustained low disease activity or remission | (5)Disease activity must be measured and documented regularly. For patients with high or moderate disease activity this must be done every month. For patients in a sustained low disease activity state or remission, this can be done less frequently (eg, every 3–6 months). |

| (6)The use of validated composite measures of disease activity, which include joint assessments, is needed in routine clinical practice to guide treatment decisions | (6)Combined disease activity measurements which include joint examinations are needed in routine clinical practice to guide treatment decisions |

| (7)Structural changes and functional impairment should be considered when making clinical decisions, in addition to assessing composite measures of disease activity | (7)Besides disease activity treatment decisions in clinical practice should also consider damage to the joints and restrictions in activities of daily living |

| (8)The desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease | (8)The desired treatment target should be maintained throughout the remaining course of the disease |

| (9)The choice of the (composite) measure of disease activity and the level of the target value may be influenced by considerations of comorbidities, patient factors and drug related risks | (9)Selecting the appropriate measurement of disease activity and target may be influenced by the individual situation: presence of other diseases, patient related factors or drug-related safety risks |

| (10)The patient has to be appropriately informed about the treatment target and the strategy planned to reach this target under the supervision of the rheumatologist | (10)The patient has to be appropriately informed about the treatment target and the strategy planned to reach this target under the supervision of the rheumatologist |

To avoid long sentences in the patient version, the group identified other words and concepts that should be explained in the accompanying text and suggested words for the glossary (see table 2).

Table 2.

Glossary of terms in lay language, in alphabetical order

| Terms | Explanation in lay language | No* |

|---|---|---|

| Adjustment of drug treatment | A change to the drug treatment has to be made. This is not always necessarily a change in drug. For patients who have not achieved the primary target of remission but show significant improvement over the last 3 months, dose adaptation or continuation for several weeks instead of change of drug(s) may be sufficient. The kind of adjustment depends on the applied strategy and individual response of the patient. |

D, 4 |

| Clinical remission | Clinical remission is based on the complaints by the patient, examination of the joints and results of laboratory tests. This can be done by the rheumatologist using a variety of instruments that measure disease activity (see table 3). When the score is below a set value, the patient is in a state of remission. Clinical remission does not incorporate radiographic, MRI, ultrasound or other imaging outcomes. |

1, 2 |

| Comorbidity | The existence of two or more (chronic) diseases in one person at the same time—for example, a patient with RA and diabetes mellitus or RA and hypertension |

9 |

| Composite measure | Measurement instrument that combines different aspects of the disease into a single numerical value. Examples of composite measures for disease activity in RA are: Clinical Disease Activity Index, Simplified Disease Activity Index, Disease Activity Score and Disease Activity Score 28 joint count. |

6, 7, 8 |

| Disease activity | Signs and symptoms caused by inflammation owing to RA. Rheumatologists use cut-off points to delineate different levels of disease activity. They often distinguish between four states of disease activity: high, moderate, low or remission. A common definition of these four states is currently not available; the definition depends on the instrument that is used (see table 3). |

D, 2, 3, 5, 6 |

| Functional impairment | The impact of the disease on performing tasks in daily life | 7 |

| Health-related Quality of Life |

Health-related quality of life is key in this statement. Quality of life is determined by a variety of individual and social factors. Health-related quality of life refers directly to the impact of the disease on daily life. It is not limited to the medical encounters in the clinic. It includes the impact of the disease on psychological health, work participation, family life, social relationships and leisure. |

B |

| Inflammation | Inflammation is the basis of the disease process in RA. It is caused by immune system cells and their products (cytokines), and leads directly to signs and symptoms, such as joint swelling, pain and stiffness. It also results in joint damage and limited function. By stopping the inflammation, damage and disability can be reduced or even avoided. |

C, 2 |

| Measurement; measurement score | The assessment of a particular health-related factor by using the most appropriate instrument (eg, test or questionnaire) | 5, 6, 7, 9 |

| Normal function | Normalisation of function is trying to return to normality: the state where a person was before the disease started | 7 |

| Outcome | The effect (end result) of the disease process on the patient or the effect of a treatment on a patient, which may be measured in different ways. Patient-related outcomes are based on the experience or opinion by the patient, and include, for example, pain, fatigue and physical function. Objective measures (outcomes) are independent of the opinion of the patient—for example, radiological joint damage (x rays) or blood tests (signs of inflammation such as sedimentation rate or C reactive protein). The term “optimising outcomes” means trying to achieve the “best end results.” |

D |

| Patient factors | Patient factors relates to personal preferences and characteristics such as occupation, age or gender | 9 |

| Remission | A state of disease activity without any significant signs of inflammation | 1, 2, 3, 4 |

| Shared decision-making | The process by which the physician and the patient take a decision together, based on a dialogue about the preferences of the patient and the knowledge (“evidence”) of the physician. A condition for shared decision-making is an equal partnership in the patient–doctor relation. |

A |

| Significant | “Significant” might be translated into other languages with synonyms such as important, serious, most, crucial or relevant. “Significant” is a relative term and often causes discussion, depending on the context and the individual perspective. In research, an outcome is statistically significant if it is unlikely that the outcome has occurred by chance (eg, a significant change in pain on a new drug). Clinical significance refers to an individual appreciation of an improvement in the real world: is an improvement really important from the perspective of the patient? |

2 |

| Signs | Signs are the manifestations that can be observed by physical examination, such as the number of swollen joints | 2 |

| Social participation | The ability to contribute to society or to enjoy social life. Functional limitations can seriously restrict chances of participation in daily-life activities. |

B, 7 |

| Strategy | A predefined way by which the clinician and the patient try to achieve the treatment target | D, 10 |

| Structural damage | The destruction of bones and joints, as can be detected using imaging techniques such as x rays, MRI or sonography. This is caused by inflammation and is largely irreversible. |

B, 7 |

| Sustained remission | A state of remission that is maintained during a longer period of time—for example, more than 6 months | 5 |

| Symptoms | Symptoms are manifestations of the disease as they are felt or experienced by the patient like fatigue, pain or stiffness | 2 |

| Target | Ultimate goal; the final outcome you want to achieve by treating RA | passim |

| Validated measurement instrument | An instrument (method, questionnaire, test) that has been scientifically proven to measure what it supposes to measure in a particular disease |

6 |

The third column indicates the treat-to-target statements where the original term is used. The letters A–D refer to the overarching principles, and the ciphers 1–10 refer to the recommendations.

RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

Evaluation of the patient version

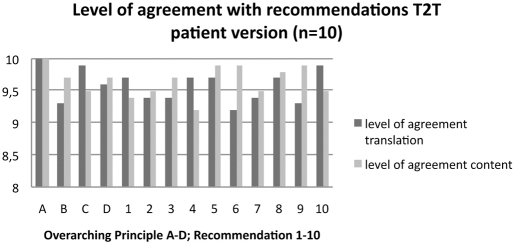

The patient group, including the patient moderator, emphasised the importance of the recommendations (mean level of agreement with the content: 9.3; see figure 1). The group was convinced that patients would benefit greatly from a patient version that informs them about the treatment regime that they receive, or empowers people with RA who do not receive treatment according to these recommendations.

Figure 1.

Level of agreement with the overarching principles A–D and the recommendations 1–10 according to the patient representatives (n=10). The level of agreement (indicated on the y-axis) was measured on a 10-point numerical rating scale with the highest number (10) representing “full agreement” and the lowest number (1) “no agreement at all.” The black bars represent the level of agreement with the translation in lay language, and the grey bars represent the level of agreement with the content.

Implementation

The patient group assumed that currently only a few patients are being treated according to these recommendations and that there is a substantial gap between daily practice and the recommended treatment strategy. The recommendations reflect the ideal world; many clinicians are aware of the importance but are confronted with barriers for implementation, and compliance is poor. The patient group also identified differences in healthcare delivery across Europe. Therefore, improvement of healthcare for people with RA requires thoughtful implementation of the recommendations. This patient version has been developed by experienced patient representatives fluent in English. The patient version has not yet been validated in a group of lay patients. Translation into different languages and testing the recommendations in different countries were seen as important subsequent steps in this process.

Dissemination of a patient version, leaflet or booklet could make patients aware of what constitutes good disease management for them: how often should they see their rheumatologist, what should they expect from the consult, what is their involvement in the decision-making process, and what should they expect from the treatment? In this respect, the perception and understanding of the target are important factors that need more consideration. A clear and uniform target in other diseases has been successfully identified and implemented for diabetes, hyperlipidaemia and hypertension.1 A similar uniform value is not available for RA. Rheumatologists use different measurements and a different terminology for disease activity,14 which complicates education of patients and a clear dialogue about the treatment target. As long as a simple and worldwide-accepted indicator for disease activity is lacking, the group felt it necessary to provide a clear overview of definitions used for high, moderate and low disease activity and remission (see table 3).

Table 3.

Validated composite measures and their cut-off points for different states of disease activity

| Composite measure (number of components) | Clinical Disease Activity Index23,24(4) | Simplified Disease Activity Index23,24(5) | Disease Activity Score based on 44 joint counts25(5) | Disease Activity Score based on 28 joint counts26(5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High disease activity | >22 | >26 | >3.7 | >5.1 |

| Moderate disease activity | >10–22 | >11–26 | >2.4–3.7 | >3.2–5.1 |

| Low disease activity | >2.8–10 | >3.3–11 | ≥1.6–2.4 | ≥2.6–3.2 |

| Remission | ≤2.8 | ≤3.3* | <1.6 | <2.6 |

American College of Rheumatology–European League Against Rheumatism preliminary definition of remission for clinical trials.15

A recent initiative by American College of Rheumatology and EULAR resulted in two proposals for more stringent criteria for remission in clinical trials15: one is a Boolean-based definition encompassing tender joint count ≤1 AND swollen joint count ≤1 AND C reactive protein (CRP) ≤1 mg/dl AND patient global assessment ≤1 (on a 0–10 scale). The other definition is the index-based Simplified Disease Activity Index ≤3.3 (table 3). For use in clinical practice, both definitions are suggested without CRP.

Discussion

Development of a patient version of a set of recommendations is currently not a common activity, and in the field of rheumatology two initiatives have been published to incorporate the patient perspective in an international project. For the patient version of the ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis,16 18 patient representatives from 10 countries were invited for a 2-day consensus meeting. They not only translated the original recommendations in lay language,17 but also extensively discussed the content of the recommendations and produced a wish list from a patient's perspective to be discussed when the recommendations are updated.

A similar endeavour was undertaken by the task force for the development of EULAR recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases.18 Using different methods, they explored the perspectives of patients and rheumatologists on glucocorticoid therapy in order to enhance the implementation of the recommendations. Although they did not produce a patient version, patient participants did provide ideas for improving the implementation of the recommendations and a research agenda.19 They conclude that patients' and rheumatologists' perspectives should be included early in the process of formulating recommendations.

The T2T patient group indicated that, according to a holistic approach of arthritis healthcare, drug treatment is an important, but not the only, component that determines clinical outcomes. The participants noticed that the T2T recommendations, like the EULAR/ASAS recommendations, have a strong focus on body functions and structures, while patient-centred care in rheumatology also requires, besides medical expertise and monitoring, non-pharmacological and psychosocial support.20 In this regard, the group emphasised the importance of multidisciplinary teamwork in the management of RA, because in carrying out the scores and in educating and empowering the patient to actually engage in shared decision-making with rheumatologists, they need support from other key professionals. Although nurse practitioners and physician assistants could be ideally positioned to educate RA patients regarding treatment options and to monitor disease activity,21 they are not available in many countries.

The patients reported from their experiences that they cannot absorb all the information provided, specifically at the first visit to a rheumatologist. A meeting with a specialised nurse could be very useful. Because it is crucial to start treatment as soon as possible after the diagnosis is made, patients should receive information about the risks of the disease and the expected outcomes of the treatment. To be effective, the patient should adhere to the drug strategy, and this can only be achieved if the patient is well informed and accepts the consequences of the strategy. A patient version is very useful to support this process.

In contrast to the EULAR/ASAS patient version, the participants did not disagree with the content of any of the recommendations and, in contrast to the glucocorticoid patient group, did not add any topics to the research agenda. This might be because some patient representatives were also actively involved at different levels in the development process of the original recommendations. In the final discussion, however, the group mentioned barriers for implementation. Above all, they referred to the limited access to rheumatology care. It is not in every country that RA patients see their rheumatologist every 3 months or more often, the doctor's time is restricted, and joint assessments are not regularly carried out, properly documented or provided to the patient. In a majority of countries, people do not have access to their own data. There are advanced digital registration systems available that allow for regular reports on disease activity, management, monitoring, patient education and self-management.22 Some are also accessible for patients who can monitor their own disease using the internet from home, but such use is not widespread.

The group thought that there is also a role for patient organisations to use the patient version of the T2T recommendations to approach politicians, regulators and healthcare payers in their country. They could make a claim for better legislation that is in agreement with widely accepted recommendations to guarantee better access to appropriate treatment strategies, good healthcare information and programmes for self-management, finally resulting in better health outcomes for people with RA.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful for the commitment and feedback of the participants in the consensus meeting: L Anderson (Denmark), S Canadelo (Portugal), C Filip (Romania), S Halland (Norway), C Kinneavy (Ireland), M Kouloumos (Cyprus), E Quest (UK), M Scholte (The Netherlands) and E Slamova (Czech Republic).

Footnotes

Competing interests This project was supported by an unrestricted educational grant from Abbott Immunology. Abbott affiliates were not involved in the programme or voting.

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dougados M, Betteridge N, Burmester GR, et al. EULAR standardised operating procedures for the elaboration, evaluation, dissemination, and implementation of recommendations endorsed by the EULAR standing committees. Ann Rheum Dis 2004;63:1172–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schoels M, Knevel R, Aletaha D, et al. Evidence for treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: results of a systematic literature search. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:638–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Viller F, Guillemin F, Briançon S, et al. Compliance with drug therapy in rheumatoid arthritis. A longitudinal European study. Joint Bone Spine 2000;67:178–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kjeken I, Dagfinrud H, Mowinckel P, et al. Rheumatology care: involvement in medical decisions, received information, satisfaction with care, and unmet health care needs in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum 2006;55:394–401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schildmann J, Grunke M, Kalden JR, et al. Information and participation in decision-making about treatment: a qualitative study of the perceptions and preferences of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Med Ethics 2008;34:775–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fraenkel L, Bogardus S, Concato J, et al. Unwillingness of rheumatoid arthritis patients to risk adverse effects. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2002;41:253–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fraenkel L, Bogardus S, Concato J, et al. Risk communication in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2003;30:443–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neame R, Hammond A, Deighton C. Need for information and for involvement in decision making among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a questionnaire survey. Arthritis Rheum 2005;53:249–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ho M, Lavery B, Pullar T. The risk of treatment. A study of rheumatoid arthritis patients' attitudes. Br J Rheumatol 1998;37:459–60 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Neame R, Hammond A. Beliefs about medications: a questionnaire survey of people with rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2005;44:762–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Horne R, Weinman J. Patients' beliefs about prescribed medicines and their role in adherence to treatment in chronic physical illness. J Psychosom Res 1999;47:555–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hill J, Bird H, Johnson S. Effect of patient education on adherence to drug treatment for rheumatoid arthritis: a randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2001;60:869–75 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The definition and measurement of disease modification in inflammatory rheumatic diseases. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2006;32:9–44, vii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:404–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zochling J, van der Heijde D, Burgos-Vargas R, et al. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:442–52 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kiltz U, van der Heijde D, Mielants H, et al. ASAS/EULAR recommendations for the management of ankylosing spondylitis: the patient version. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1381–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoes JN, Jacobs JW, Boers M, et al. EULAR evidence-based recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1560–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.van der Goes MC, Jacobs JW, Boers M, et al. Patient and rheumatologist perspectives on glucocorticoids: an exercise to improve the implementation of the European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) recommendations on the management of systemic glucocorticoid therapy in rheumatic diseases. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:1015–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coenen M, Cieza A, Stamm TA, et al. Validation of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Core Set for rheumatoid arthritis from the patient perspective using focus groups. Arthritis Res Ther 2006;8:R84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lesko M, Young M, Higham R. Managing inflammatory arthritides: role of the nurse practitioner and physician assistant. J Am Acad Nurse Pract 2010;22:382–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koevoets R, Allaart CF, van der Heijde DM, et al. Disease activity monitoring in rheumatoid arthritis in daily practice: experiences with METEOR, a free online tool. J Rheumatol 2010;37:2632–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smolen JS, Breedveld FC, Schiff MH, et al. A simplified disease activity index for rheumatoid arthritis for use in clinical practice. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:244–57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aletaha D, Smolen JS. The Simplified Disease Activity Index and Clinical Disease Activity Index to monitor patients in standard clinical care. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2009;35:759–72, viii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prevoo ML, van Gestel AM, van T Hof MA, et al. Remission in a prospective study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. American Rheumatism Association preliminary remission criteria in relation to the disease activity score. Br J Rheumatol 1996;35:1101–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Gestel AM, Haagsma CJ, van Riel PL. Validation of rheumatoid arthritis improvement criteria that include simplified joint counts. Arthritis Rheum 1998;41:1845–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]